2025 Nº 59

2025 Nº 59

The

remarkable untold story of Shakespeare’s

first theatre – the playhouse before the Globe

OUT NOW with booksellers nationwide

FOR THE LONDON LIBRARY

Josephine Noti

Head of Marketing and Communications

Felicity Clark

Membership Director

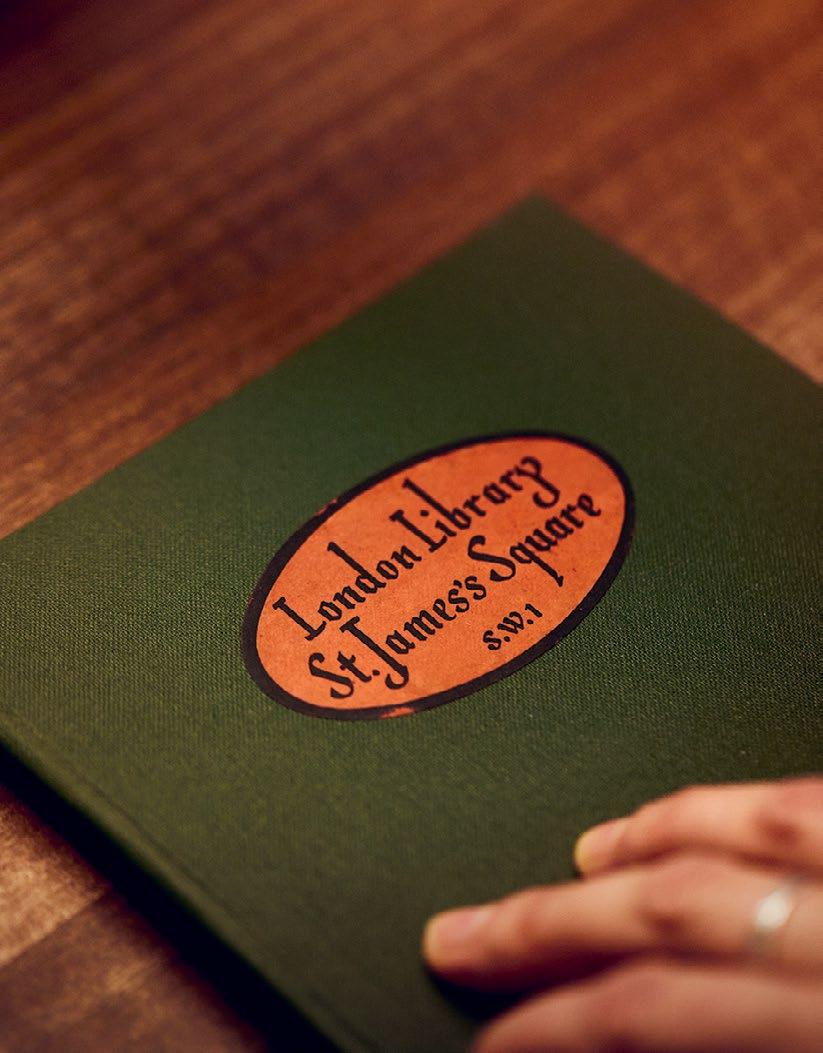

The London Library

14 St James’s Square

London SW1Y 4LG (020) 7766 4700

magazine@londonlibrary.co.uk

EDITORIAL: CULTURESHOCK

Editor Alex McFadyen

Contributors

Nancy Groves

Deniz Nazim-Englund

Photography

Charles Cave (cover)

Ellie Smith

Head of Creative

Tess Savina

Art Editor

Gabriela Matuszyk

Designer Ieva Misiukonytė

Subeditors

Michelle Corps

Hannah Jones

Susie Wong

Publisher

Phil Allison

Production Manager

Nicola Vanstone

Advertising Sales

Cultureshock (020) 7735 9263

‘The Dream Factory is one of the most exciting and original books about Shakespeare that I’ve read in years ... A thrilling story, well told.’

James Shapiro, author of 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS yalebooks.co.uk | @yalebooks

The London Library Magazine is published by Cultureshock on behalf of The London Library © 2025. All rights reserved.

Charity No. 312175.

Cultureshock

27b Tradescant Road

London SW8 1XD (020) 7735 9263

cultureshock.com @cultureshockit

The views expressed in the pages of The London Library Magazine are not necessarily those of The London Library. The magazine does not accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. While every effort has been made to identify copyright holders, some omissions may occur.

ISSN 2398-4201

Welcome to the Spring 2025 edition of The London Library Magazine. We have enjoyed a busy start to the year, which has included progress on our plans for the building (page 7), a Royal visit in February (page 8), and a revamp of the conservation studio. The Collection Care team now has better facilities for its important work and we have an article by Michelle Hunter, Collections Manager (page 20), about some of the more unusual projects the team has carried out in the past year. In this issue, we also bring you some moving and fascinating articles from families of members of the Library. We have a tribute to member Hannah Lynch (page 17), who tragically died last year at just 18 years old. Hannah was a talented poet and we are honoured to bring you two of the more than 100 poems she wrote in recent years. We also explore the life and work of past member Miron Grindea, the longtime editor of literary journal the Adam International Review, in our From the archive piece (page 13). We were fortunate to be visited by his daughter and grandson earlier this year, who shared touching details with us of his experience at the Library.

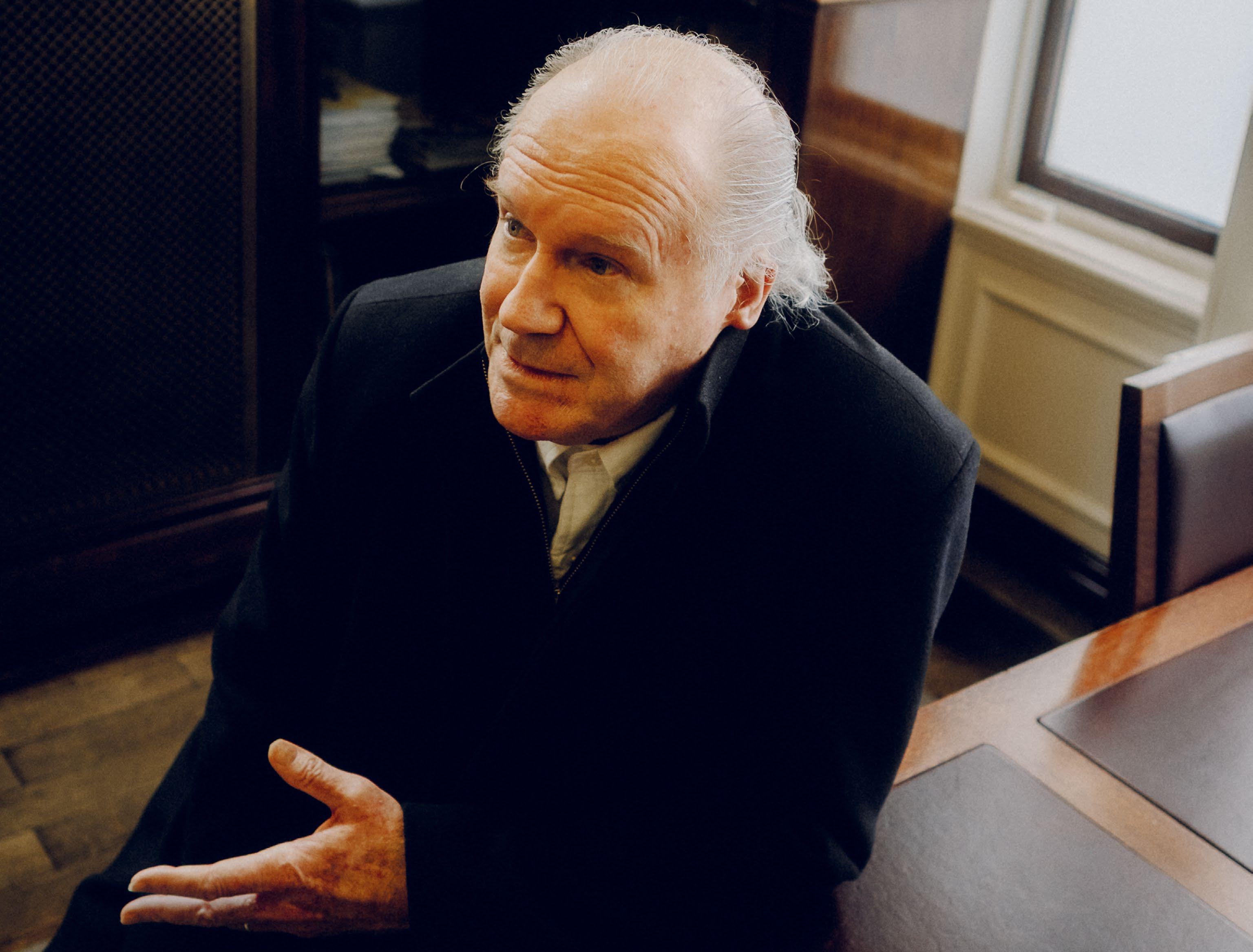

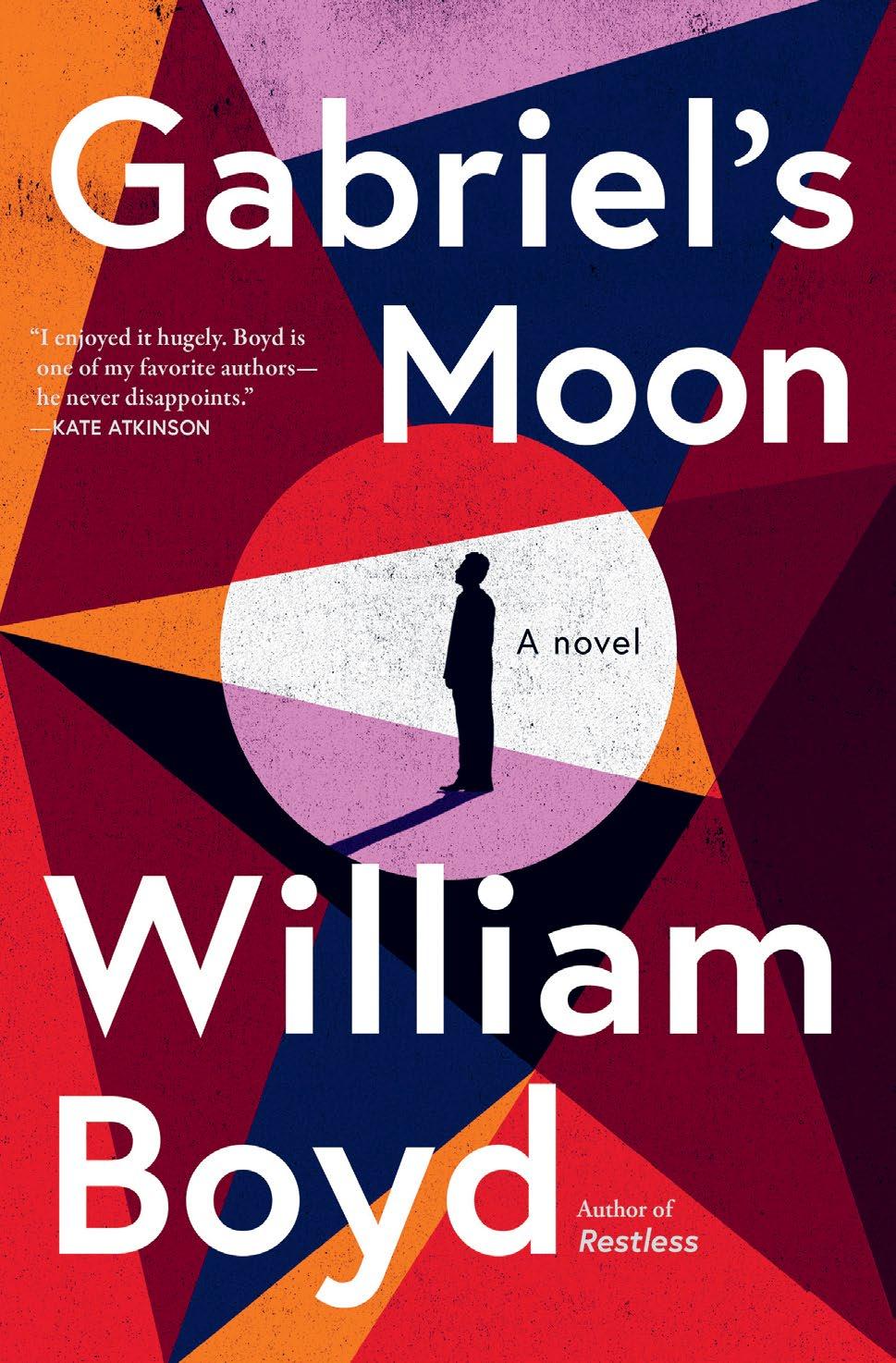

In our interviews with members, we hear from celebrated writer William Boyd, who talks about his latest novel, the first in a trilogy of intricate spy thrillers, and how the collection has helped him with niche research for his characters’ backstories over the decades. Author and broadcaster Hallie Rubenhold speaks about her new book, Story of a Murder: The Wives, the Mistress and Dr Crippen, where she once again illuminates a historical crime and places the women in the case at the centre. And finally, screenwriter and playwright Vinay Patel tells us how he broke into the business, and began experiencing the “hug” of The London Library.

As ever, I hope you enjoy the issue, and that we see you at the Library soon.

• Philip Marshall, Director

There is little that rivals The London Library’s eclectic physical collection of around one million books, but its collection of ebooks comes close – and is constantly evolving. Of the more than 1,500 titles to choose from, these were some of the most borrowed of 2024.

1. Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire by Nandini Das (borrowed 26 times)

2. Belfast: The Story of a City and its People by Feargal Cochrane (borrowed 23 times)

3. The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen (borrowed 23 times)

4. Babel: Or The Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution by RF Kuang (borrowed 22 times)

5. Politics On the Edge by Rory Stewart (borrowed 21 times) •

→ Members can access the eBook collection through OverDrive or the Libby app. Learn more at londonlibrary.co.uk/ebooks or browse the collection at londonlibrary.overdrive.com

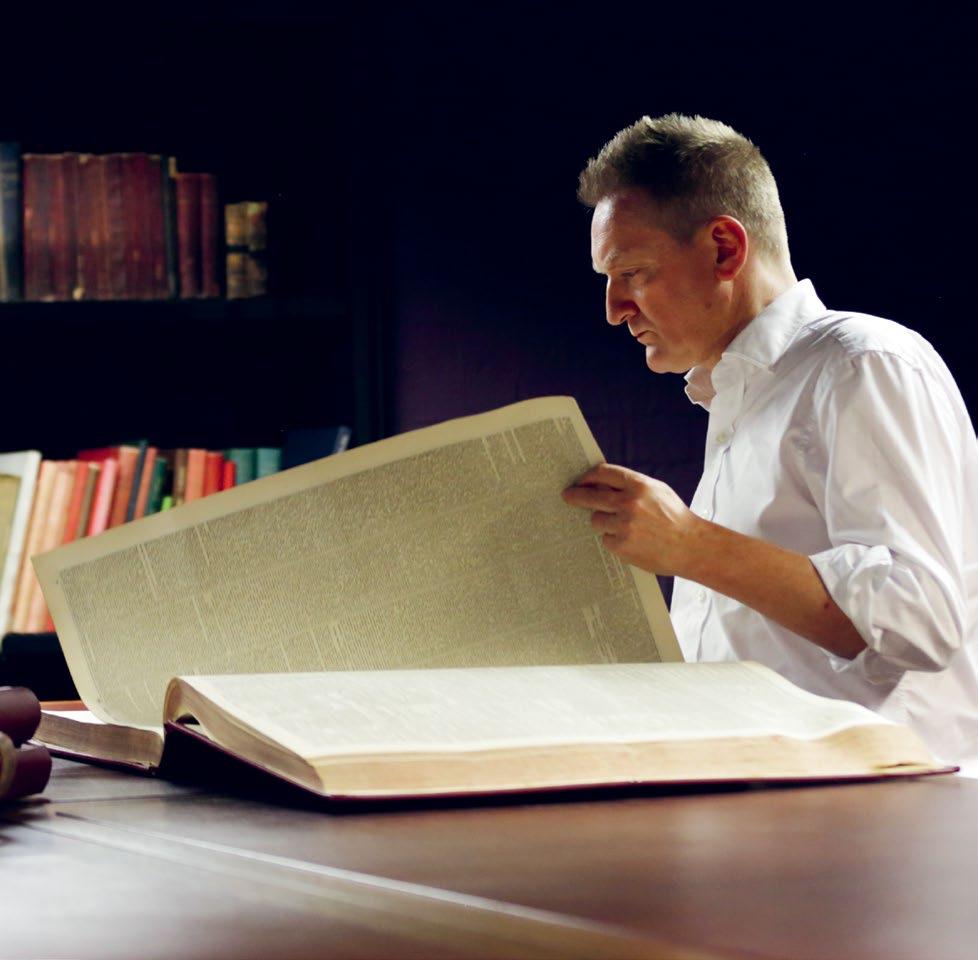

From military lists to directories and specialist newspapers, such as a full archive of trailblazing Victorian news magazine The Illustrated London News, the collection at St James’s Square includes a huge range of diverse historical records that illuminate the lives of both ordinary and famous Britons.

Many of these volumes have now been digitised and published online for the first time as part of a partnership with genealogy service Findmypast. Highlights include Zozimus , a magazine packed with cartoons and satire, which was published in Ireland in the 1870s, and The Ladies’ Who’s Who from 1924, which recorded the lives of influential and distinguished women from the past, reflecting a social shift towards greater recognition of women’s achievements.

Findmypast, which also has partnerships with the British Library and The National Archives, draws on diverse sources to help users understand their ancestors’ lives in narrative detail, bringing together information on where they lived and worked, their relationships, and the life-changing events they experienced. This will now be further enriched by the addition of The London Library’s holdings. •

→ Start exploring The London Library collection at findmypast.co.uk

Planning permission has now been granted for Phase One of the Library’s Building Connections project. Works are planned to start in late July and be completed by the end of 2025.

Thanks to the incredible support of donors, we have secured the necessary funds to invite tenders from building contractors . The first phase includes a new room on the ground floor, which will be a permanent, dedicated space for uses that pertain to the Library’s public benefit remit as a charity. This includes sixth-form school visits, meetings of the Emerging Writers Programme, speaker events, exhibitions and displays, and workshop collaborations with other charitable organisations. The space will also provide a venue for member special interest groups to meet, as well as hosting trustee meetings and being available for private hire.

Phase One will also see the creation of a basement kitchen to replace the current use of The Study as a field kitchen by event caterers and provide a much-needed storage area.

The construction project will take place in small, contained areas of the building, away from the main reading rooms and most of the collection. The Library and its architects have a lot of experience in keeping the building open during works and keeping disruption to a minimum. This remains a priority.

Technical design work is currently being finalised with the procurement phase now beginning. Members will be kept up-to-date over the coming months with further information about the plans, designs and building works. •

→ To find out more about the building project, visit londonlibrarybuildingconnections.co.uk

Each year, the Library acquires around 5,000 new books, ensuring that the collection continues to reflect members’ varied and evolving reading habits.

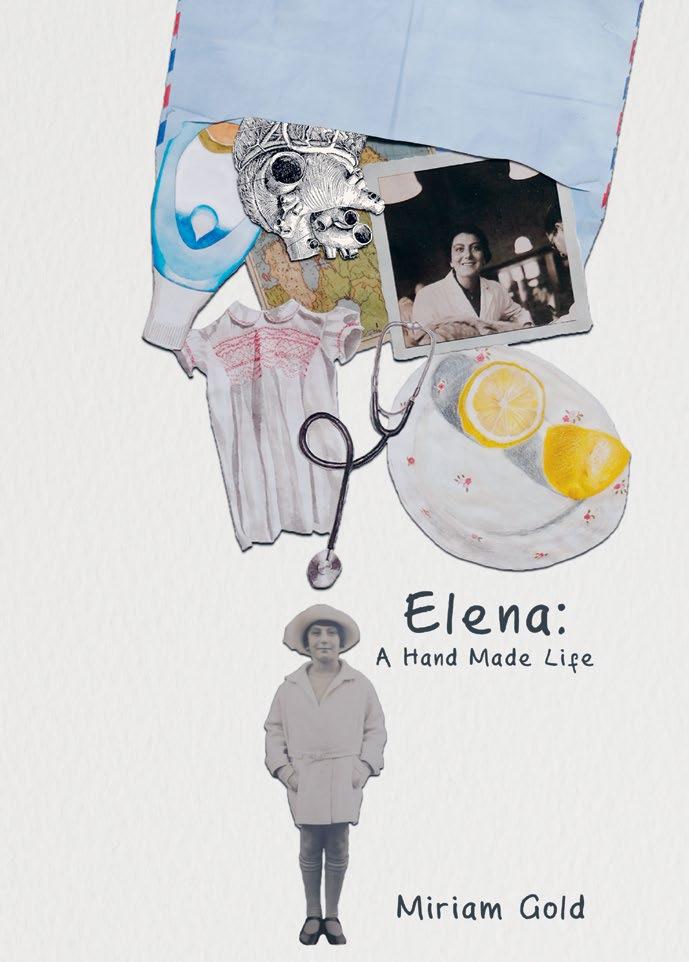

Recently, the stacks’ treasure troves have been enhanced with the addition of two new collections: Graphic Novels and Creative Writing. Graphic novelists have been part of the Emerging Writers Programme since 2021; one such writer is Miriam Gold (whose work was featured in The London Library Magazine, spring 2024). Her beautiful illustrated novel Elena: A Hand Made Life, published in August 2024, can now be found on the shelves. The new Creative Writing shelfmark houses books to support members with their writing careers, especially those early career writers, including our Emerging Writers Programme participants

In addition to this, The Philip Mould Picture Archive recently became available to all members as an e-resource. This fully searchable online database comprises every artwork that has passed through the gallery’s doors, covering 500 years of British art. All the images in the archive can be licensed for scholarly, editorial and commercial usage through Bridgeman Images. •

→ To search the new collections, visit catalyst.londonlibrary.co.uk

Her Majesty The Queen attended a dinner to celebrate the Library’s charitable and outreach work

We hosted a special event on 4 February, attended by our Patron, Her Majesty The Queen. The dinner celebrated The London Library as one of the UK’s greatest literary institutions, highlighting its charitable work to support writers and widen access to its extensive resources.

Held in the Library’s atmospheric Reading Room, esteemed guests and Library supporters, including Sir Tim Rice, Alexandra Shulman CBE, Lady Antonia Fraser, John O’Farrell and Dame Caroline Michel, were given an introduction by Helena Bonham Carter CBE. She said: “I have the honour of being the President of The London Library. It is very easy to be astonished by the atmosphere of this place. We have 17 miles of books here, which is the equivalent of the underground Circle line. Thank you for becoming our Royal Patron and continuing the long line of Royal Patrons that the Library has been fortunate to have.”

There was also a speech from Sir Stephen Fry, who said: “Thank you for your patronage, your support not

just of The London Library, but of books and writing everywhere. Just like The Queen’s Reading Room, this Library is open and welcoming to all. Here we are all equal citizens of the great kingdom of letters, the realm of reading, and here the highest possible doctrine is held for the value of books, the value of collections, the value of a sanctuary… where anybody who loves books is made to feel at home.”

Simon Godwin, the chair of The London Library, introduced Katie Buckley, a participant of the Library’s Emerging Writers Programme, whose recent novel, Hero, was published by Hachette UK in January. Writer and London Library member Christopher Simon Sykes also performed a song about the Library, written especially for the evening.

Buckley said: “EWP (as it’s affectionately called) is a life-changing programme. Generosity is what underpins the thing that all new writers need – someone who will listen. A chain reaction of people holding out their hand and pulling you upwards… It has been the honour of my life to have begun my beginnings here and for that, I will be forever grateful.”

As Patron of The London Library, Her Majesty The Queen has supported the institution since 2012, within her current role and previously as Vice-Patron. A passionate champion of literacy both in the UK and internationally, Her Majesty The Queen encourages a love of reading and writing from an early age. Her charity and book club, The Queen’s Reading Room, works to advance education by providing opportunities for the appreciation of literature among adults and children in the UK and around the world.

Philip Marshall, the Director, said: “We were delighted to host a wonderful evening to celebrate The London Library as the home of literary inspiration. We are tremendously grateful to our Patron, Her Majesty The Queen, for her continued support as we aim to engage, inform and inspire many more readers and writers with our incredible resources.” •

There are few spots in London that are quite as fair

As the charming and leafy St James’s Square.

With its beautiful trees and flowering shrubs

And four quite famous Gentleman’s Clubs

But of all the buildings that it now boasts

There is one that is filled with literary ghosts.

Some of them ancient, others contemporary Roaming the stacks of The London Library.

If The London Library in the North-West corner

Were ever to close, how we would mourn her, For 200 years she’s been the second home, Of novelists, biographers and writers of tomes On history, geography and science fiction

And everything from comedy to sex addiction, While those who might bore of literary capers, Can come for the mags and the Daily papers.

It was all the brainchild of Thomas Carlyle, Who’d been in the British Library for quite a while, And couldn’t find a seat, but what made him madder Was ending up having to sit on a ladder.

At which point he thought “Enough is enough” The comfort level here is far too rough.

I’ll open a Library in one of the squares, And mine will be furnished with brown leather chairs!

The square he chose was that of St James’s Where he built up a list of hundreds of names’s, All of whom wished to become paying members With subscriptions from January to December. He established the Library in number fourteen, As fine a building as he’d ever seen. Then put out the word, and soon more and more Of Literary London flocked to the door.

Today how we all love roaming the stacks, Picking our way gingerly between the cracks

The smart ones shoeless, wearing only socks To avoid getting sudden electrical shocks. We climb to the top floor to research biography To the basement if we wish to explore topography There’s also Art, Literature, Science and History Though the location of the Times is a bit of a mystery.

A day in my life that I’ll always remember Was joining the Library and becoming a member

Of what seemed to me like a wonderful club

Of like-minded people at its very hub. In my life London Library, you’ve played a huge role, You’re part of my being, part of my soul. The bond that’s between us no one can sever. So, live on London Library, live on forever.

An extract from a forthcoming memoir about the lives of women in Iran by AD Aaba Atach, a member of the 2023–24 Emerging Writers Programme. Atach’s book was recently signed by Canongate in a major deal

Tehran, 1999

It was the day when my father – Baba – received an abrupt phone call informing him that the editorial board for the Salam newspaper would not be meeting until further notice. He was in his late 20s, but he was already being described by his chiefs as a promising up-and-coming force within Iranian politics.

Earlier that week, Salam newspaper had leaked a government memorandum that had revealed the Islamic Republic’s plans for the suppression of reformist publications, of which Salam was one. Until then, for the first time since the inception of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iranians had been given a taste of what a progressive – though never quite liberal – Iran could be: no longer wishing death upon the Americans nor the Brits, but looking ahead toward dialogue, democracy, civil society, or so they said.

The newly elected President, Mohammad Khatami, had promised many things, amongst them the protection of press freedoms, so that the new generation could transcend the muted voices, the whispers, and the stifled expressions of their parents. The age of compliance was over: a society where your thoughts could be aired, even published; where women and men could mingle, talk, and debate freely in neighbourhood cafes, to the robust aroma of tobacco and freshly brewed tea, hands occasionally swaying ever so slightly closer, close enough for the fingers of the opposite sex to brush against each other. Freedom, with all its breeze, yearning, joy. They had been sold a dream, and now they wanted to live it.

Within days of the leak, the Clerical Court had mandated the swift closure of the newspaper, and its publisher, Mohammad Mousavi Khoeniha, had been summoned. Though Baba did not yet grasp the scale of the coming uproar, the day before we were to protest the newspaper’s closure, he knelt before me and tried to explain why he might disappear at any moment, just as three of his colleagues already had. I was a month short of turning five, but that was a peripheral matter: in a country where my childhood could be stolen at any moment, he saw no need for sugar-coating –he wanted me to be fully informed, as any adult would be.

On July 9, it was no different. I recall it was getting dark, and the atmosphere was charged: some wanted to start protesting at night time. Baba was not at ease, and he had not told my mother – Maman – of our whereabouts. He couldn’t – it was too risky, but he also did not want her to be concerned, not so soon. Though they had separated, they did not see it reasonable to do so with hostility – not yet – so they often remained in communication with each other, for my sake.

While Baba tactically planned for a second attempt at protesting the following day, some of his peers already set out to do so when the night was at its darkest. Their efforts, however, were cut brutally short: at 3am that night, while we were sound asleep, over 400 police officers broke into the dormitories, methodically searching each room, not shy to assault any student on the way. By the time Baba and I woke up to his friend’s erratic phone call, over 800 student rooms had been ransacked, stomped over, damaged; windows shattered, books thrown out, wallpapers burnt. To Baba’s fury, and to the shock of his friends and colleagues in Tehran, five of their fellow university members had been killed, 400 wounded, and half of that number arrested. While Maman’s concerned phone calls went straight to voicemail, Baba prepared us for a fight. Maman still did not know of our whereabouts, or that we were heading to what later became known as Iran’s Tiananmen Square moment.

A longer version of this extract appears in the EWP anthology, From the Silence of the Stacks,

Grindea valued the Library’s extended loan periods, calling them “part of the magic” of membership

essay by Marcel Proust on Honoré de Balzac (which was submitted by Proust’s niece), a play by Jean-Paul Sartre, and the correspondence of Charles Dickens with the artist and socialite Count D’Orsay. Grindea also had a knack for discovering people, and was in contact with Franz Kafka’s niece, Leo Tolstoy’s secretary and Proust’s waiter from The Ritz, all of whom offered Adam “alternative, personal reminiscences”. After the Second World War, its focus was not solely European, either. Writing was introduced from Sri Lanka, Senegal, Canada and India, offering, says Lasserson, a “truly global perspective”.

Though nominally a quarterly journal, Adam was published at differing intervals, usually when Grindea felt he had gathered sufficient material. He valued the Library’s extended loan periods, which allowed him to hold onto research books while building an issue, calling them “part of the magic” of membership. Reflecting on Adam’s decades-long run, The Times declared Grindea a “born editor”, and the journal “the most remarkable one-man performance of our lifetime”.

In recognition of the inspiration he found at St James’s Square, the 1978 issue of Adam, published in book form by Boydell Press, was titled The London Library. In the opening pages Grindea expresses gratitude for his “miracle” sponsorship by Dame Rose Macaulay, which enabled him to become a member. The issue also includes essays by former Librarians Stanley Gillam and Charles Hagberg Wright.

Both this issue and the two anthologies edited by Rachel Lasserson are available to borrow from the collections. They can be found under Periodicals; Grindea, Adam, along with other issues donated by the journalist and his family. The complete Adam International Review archive, as well as Grindea’s personal library of 20th-century European literature, was acquired by King’s College London in 1984 and is known as the Adam Collection.

As a Romanian emigre, who arrived in London unable to speak English, Grindea told his family that there were “types of club where he wouldn’t be able to be a member… places he couldn’t understand and that may not understand him”. Ultimately, however, he “found his home” at The London Library.

Words by Katrina Quick

Mosaics of Muses, memories, hidden words

Strung together to form

Saccharine breaths

Dripping honey over

The window of my world

You pushed love out of bed

Reminded the heart to rise

Again

On the third day.

Resurrection of connections, People left with forlorn flowers

Scattered, smothering their lungs

Are gifted roots to pull the stems

Back to where they belong.

Petals pushing and urging and gently loving the heart

Nothing is aching for us to be apart

This is the poem I wrote that we were talking about at lunchtime.

It is about the platonic love I have for my friends and sister. It was done rushed and late at night, but I like it.

Your pale, prostrate Christ

Enamelled in his melancholy

Waxen tears crowning carved eyelids, White hands pierced with the Stars driven across the heavens

Like matches struck in the delicacy

Of ebony. If only we could be saved, If only sacrifice were to be a tenable

Position the tender meat of snowy heifers, Their heads once bowing under

The weight of flowers is burned to Unknown Gods. And I see you,

With your own constellations, Other interpretations. I want you

To kneel under the burden of the stars, And start your journey of atonement And redemption in light of the eternal eyes that will follow your path through this sky.

a consultant conservator, who used strong, lightweight Japanese tissue paper fixed with gelatin.

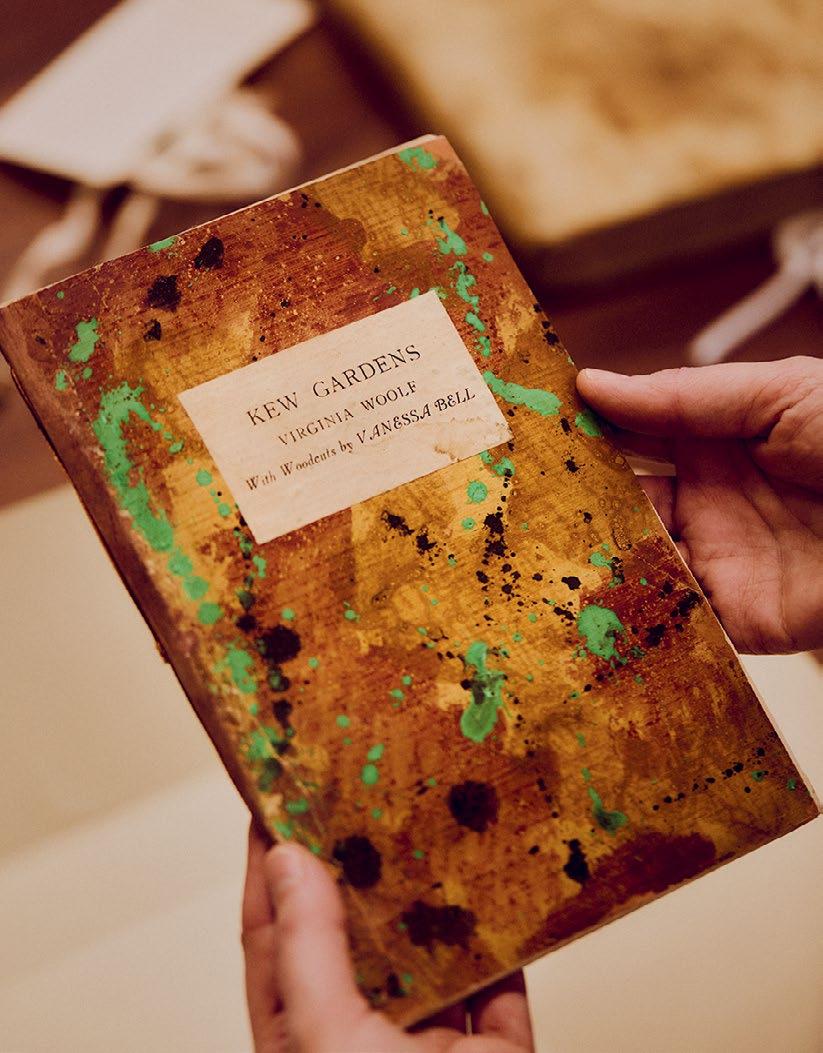

A 1919 print of Virginia Woolf’s Kew Gardens, featuring woodcuts by Vanessa Bell, required more extensive repairs including the restoration of the original covers and the creation of a brand new four-flap case to house the book. The original paper covers – thought to have been handpainted in the Omega Workshops run by artist Roger Fry – were removed from the back of the old binding and reattached to the text block. A consultant conservator made Japanese tissue repairs along the spine and colour matched it to the original covers, restoring the binding to its original design.

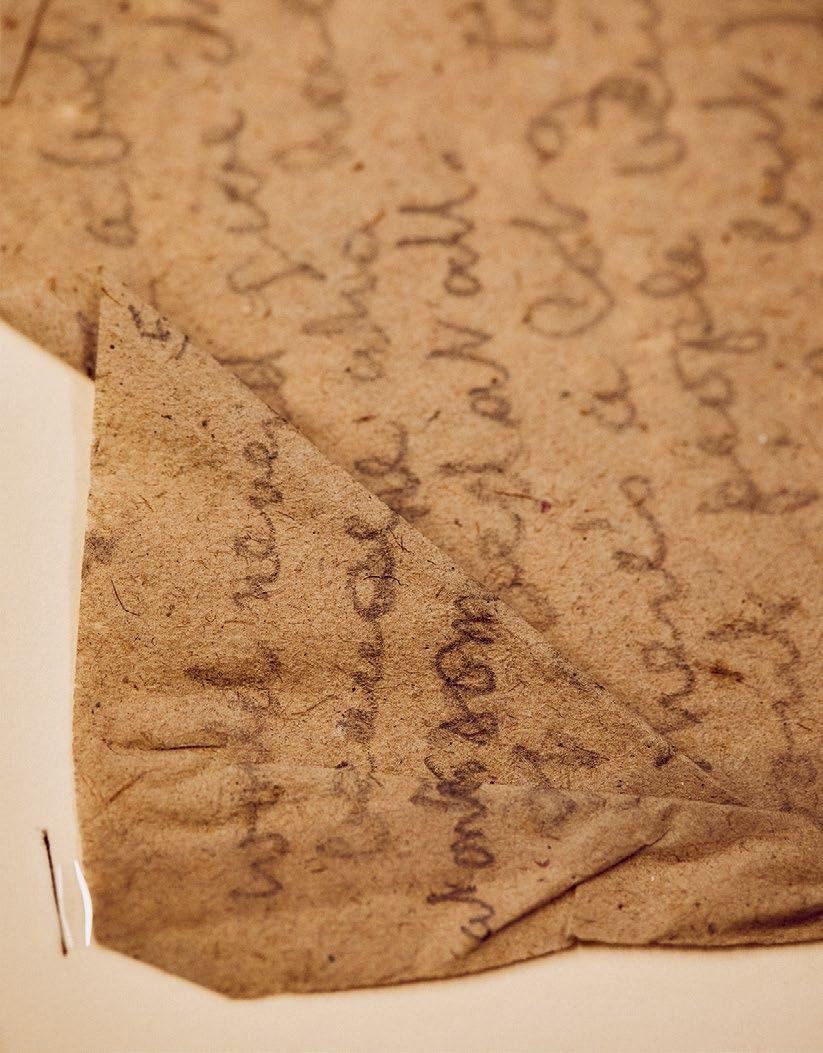

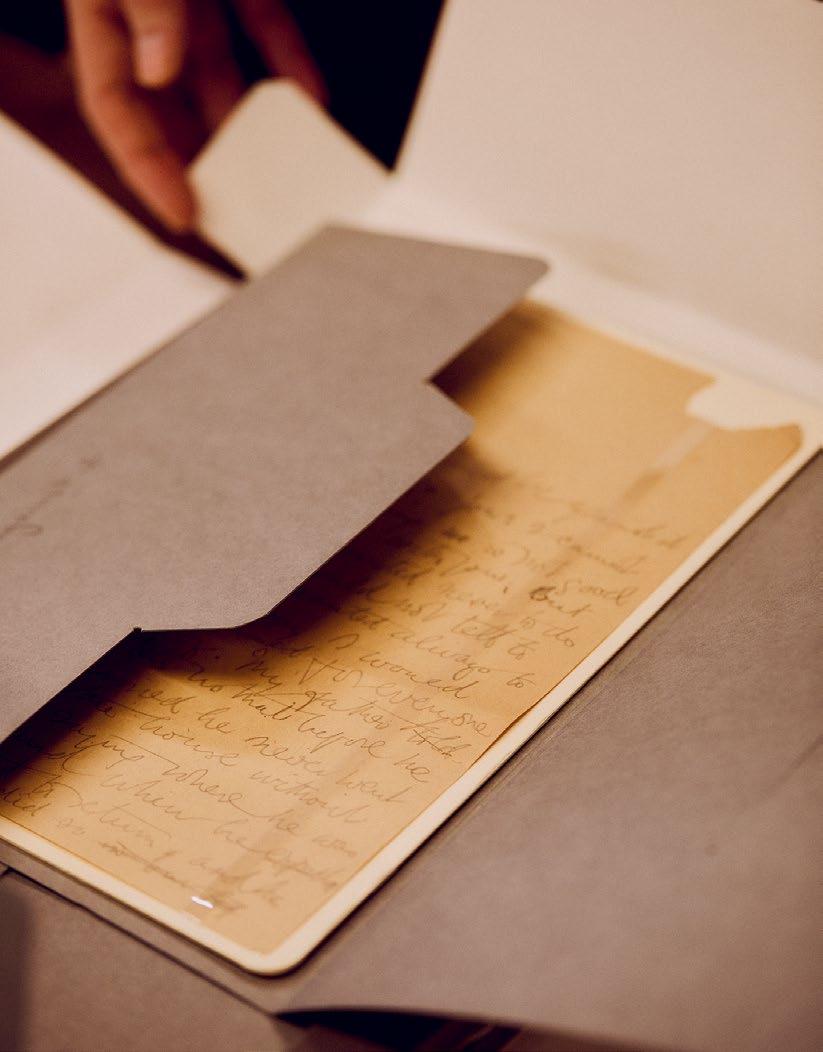

In general, the Collection Care team works on books, but in April 2023 an unusual series of documents came to the Library. Between Two Fires is a “lost play”, written by suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst on toilet paper and medical gauze wrappers while she was imprisoned in HMP Holloway between 1920–21. Pankhurst’s play was performed at the Library in 2023 and 2024 and we mounted the papers for display for both occasions. We would usually

address paper folds, as they affect an object’s stability, but we felt they were part of the documents’ history.

Any member can ask to view a special collection item under invigilation, but we limit how often these objects are handled in a year to avoid wear and tear. Even taking a book off the shelf by the top of its spine, which feels natural, can cause damage. If you can, you should push a book out from behind. People also create dust, which invites pests (as does bringing food and coffee to the Library, which is why it’s only allowed on the 6th floor).

Before working in Collection Care, I ran my own glass and jewellery business, working in all sorts of different libraries on the side. I decided to do something practical in that field so I took bookbinding and conservation classes. As soon as I started at The London Library, I knew this was going to be my home for some time.

I love working with my hands. It’s a privilege to handle beautiful books, show them respect and make them last. •

Interview by Deniz Nazim-Englund

“I love working with my hands”

William Boyd, who renders his characters’ interior and exterior worlds with equal acuity, tells Katie Glass why novels are the most empathetic artform

Portraits by Charles Cave

“Only in the novel do you get this free, uncensored access to the thoughts of other people”

that curious relationship with my native country and my inherited country, Scotland. There’s no doubt it’s contributed to what I write and think, and how I feel about things.”

He notes that Graham Greene claimed authors were forged by their first eight years. Boyd thinks it’s closer to 20 years: “My theory is it’s before you become self-conscious about being a writer. Your great quarry of emotions, experiences and sensations before you started filtering it through a writer’s perspective… [it] forms the mulch in which I plant my seeds.”

Greene was one of the first writers who inspired Boyd. As a teenager he read The Heart of the Matter, set in Sierra Leone, “just next door to Ghana… the landscapes and the ambience of the novel were completely familiar to me. I think that’s when I saw how your everyday experiences were the material you needed to write something fictive.”

Originally, he wanted to be a painter, but his father said he hadn’t “a hope in hell”. “One of my great regrets,” says Boyd, “is that he didn’t live long enough to see my novels published, and a certain kind of success arriving – to know I wasn’t a fantasist.” His father died at 58, when Boyd had published a few short stories. “He had absolutely zero confidence in this ambition of mine to be a writer.”

If Greene inspired Boyd to take external inspiration, F Scott Fitzgerald opened his eyes to the novel’s potential for revealing a character’s interiority. He holds the longstanding conviction that novels are the only way we can truly know each other. “Whether it’s Jane Austen, Charles Dickens or Saul Bellow, what the novel does is give you effortless access to the interior life of other people. Life is

mysterious, people are mysterious – the only place you’ll find guaranteed certainty, paradoxically, is in a work of fiction. Jane Austen can tell you exactly what Elizabeth Bennet is thinking about Mr Darcy. It’s unique amongst art forms. Only in the novel do you get this free, uncensored access to the thoughts of other people. You can’t film that, you can’t put it on stage, you can’t write a symphony that does the same, or draw a drawing, or paint a painting.”

What about the trend for memoirs coupled with people endlessly chronicling their personal lives online? Boyd shakes his head: “But the thing about autobiography, even if it’s on TikTok, you know: ‘I had a shitty day and I hate my best friend,’ is that it’s shaped. I think the confessional mode is highly suspect because it’s a way of presenting yourself in the best possible light, even though you may protest you’re not.” He considers Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions, which inspired The New Confessions, “one of the most extraordinary autobiographies ever written. He seems totally candid, and he’s very honest about himself and his sins and his failings. But, of course, it’s entirely self-serving. Like most autobiographies, it’s for posterity.”

It is true that few autobiographers would share the humiliations suffered by Any Human Heart’s Logan Mountstuart, whose poverty leads him to eat dog food, and who flees the country facing a charge of statutory rape. Mountstuart is also candid that he will not rewrite his “errors of judgment” – such as his proclamation that “the Japanese would never dare to attack the USA unprovoked”.

Meeting Boyd at 3pm means I’ve monopolised his writing rush hour. “The coalface is between post-lunch and pre-Channel 4 News or the evening cocktail,” he tells me with a grin. When I ask about his other writing rituals, he insists there is “nothing too fetishistic. I’m conscious of that being a way of not writing,” he says, noting that Muriel Spark only wrote novels in a particular notebook she purchased from an Edinburgh stationer. “Then it went bust and she thought: ‘I’m never going to write another novel again.’”

Boyd’s craft involves a detailed period of imagining, then a second period of composing, so by the time he sits down to write he knows precisely where every book is going. “I don’t start on page one until I know exactly how the book will end. I sometimes have actually written the last lines of the novel first, so I know the tone or the catharsis I’m seeking. In a way, all that preliminary work, the research, filling notebooks, travelling, is a way of making sure that your destination is the one you want. I don’t write particularly fast, but I write with confidence.”

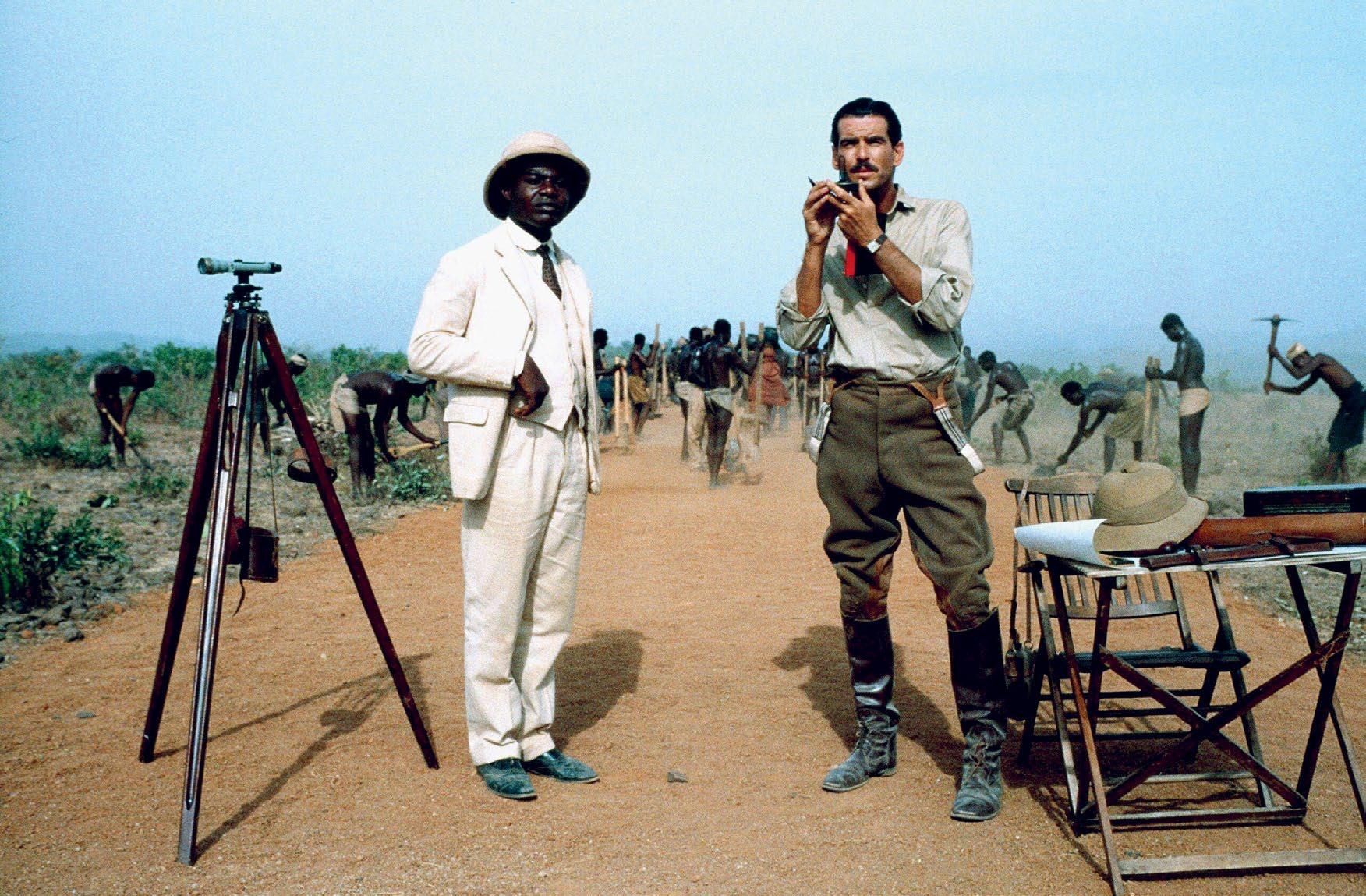

Right now he is adapting Graham Greene’s novel The Captain and the Enemy for a film. And his opera based on Anton Chekhov’s short story A Visit to Friends – for which he has written his first libretto – premieres at Aldeburgh Festival in June. He likes to keep his work varied, alternating between novels and screenwriting. “I have perfect autonomy as a novelist. I have my ivory tower. I descend from it with pleasure, because I really like collaborating. I’ve worked with three of the James Bond actors – Sean Connery [on the film adaptation of Boyd’s novel A Good Man in Africa], Pierce Brosnan [on the film Mister Johnson] and Daniel Craig [on the war film The Trench, which Boyd wrote and directed]. I mean, how would that happen in a novelist’s life?” One imagines it also gives him more access to interesting worlds from which to take inspiration. Lucky us. •

Katie Glass is a feature writer and columnist who has been writing for The Sunday Times since 2010

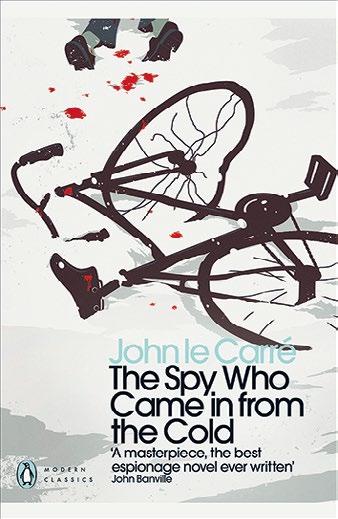

“This is le Carré’s masterwork,” says Boyd. A British spy tasked with posing as a defector in Cold War-era East Germany discovers that he is part of a “complex double-bluff sting” in this “bleakly cynical” look at the machinations of senior secret-service spooks, which questions the ethics of espionage.

Find it in: Fiction; Le Carré, John

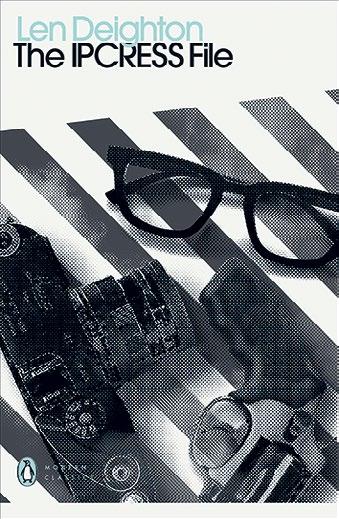

Expect classic Cold War concerns in Deighton’s first novel, set across 1960s London, Europe, Lebanon and the Pacific. The author’s choice to write the unnamed protagonist as working class “shines a fresh light on the ‘mandarins’ at MI6”, says Boyd of the public-school bureaucrats at the top of the agency. “Along with le Carré, Deighton reinvented the modern espionage novel.” Find it in: Fiction; Deighton, Len

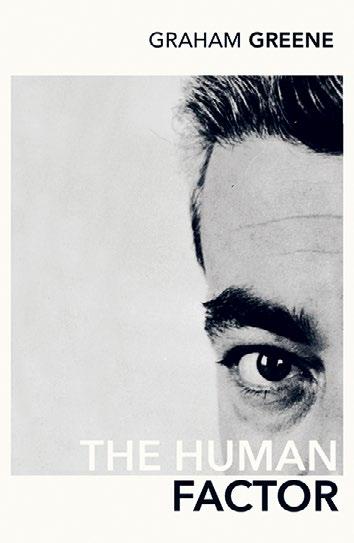

An intelligence officer from the Eastern and Southern Africa section of MI6 has his sense of loyalty tested in what Boyd describes as “Greene’s analysis on what makes a man decide to betray his country”. The story is “inspired by [Greene’s] friend, Kim Philby”, who was a double agent.

Find it in: Fiction; Greene, Graham

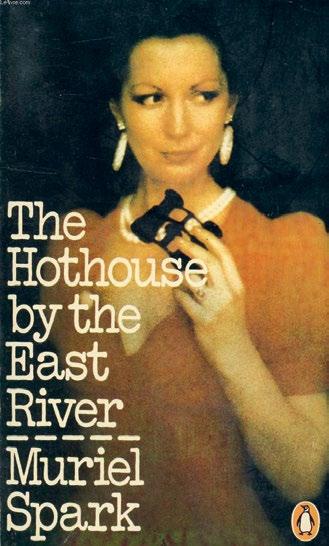

Drawing on Spark’s own wartime espionage work “in psy-ops”, the story is set between 1970s Manhattan and a British prisoner-of-war camp during the Second World War. Boyd calls it “one of the strangest spy novels you’ll ever read” as its ending left critics mystified.

Find it in: Fiction; Spark, Muriel

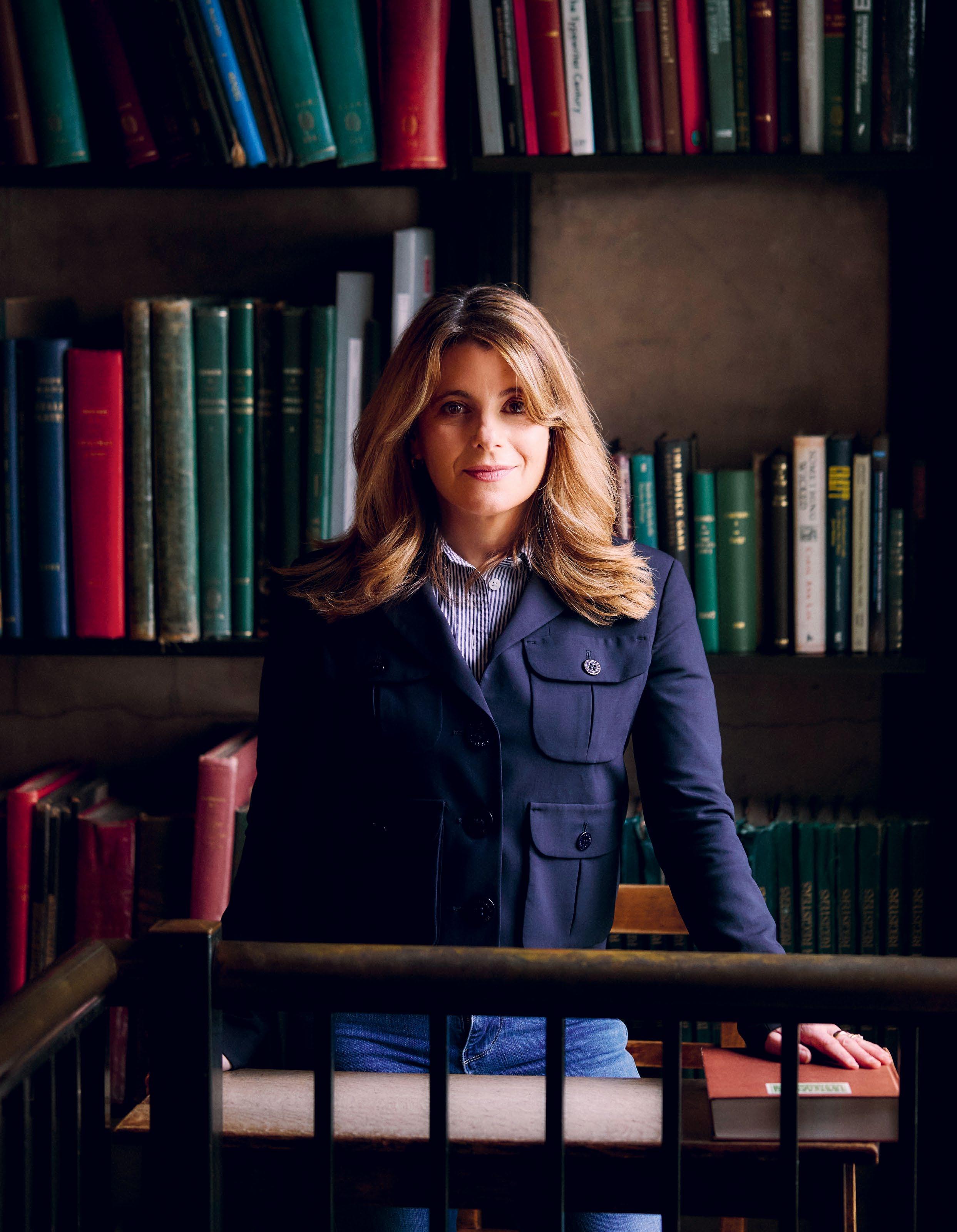

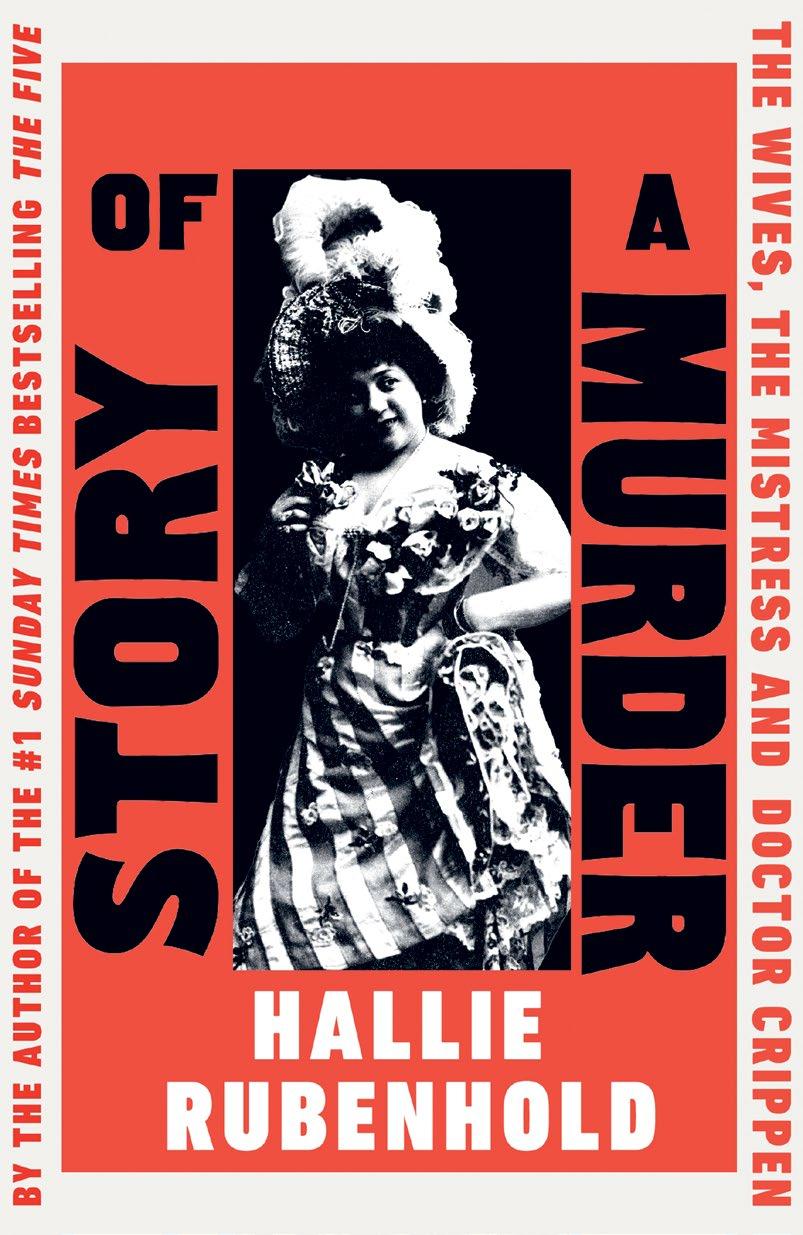

Historian Hallie Rubenhold brought a measure of literary justice to the victims of Jack the Ripper – now she’s investigated the music-hall murder that shocked Edwardian London, writes Nancy Groves

Portraits by Ellie Smith

Hallie Rubenhold is just coming up for air. She has spent the past five years “totally immersed” in the multi-layered, sometimes gruesome archival sources for her latest book, Story of a Murder: The Wives, The Mistress and Doctor Crippen.

Both a gripping slice of Edwardian true crime and a meticulously researched social history, Rubenhold’s retelling of a 1910 international tabloid sensation involves a cast of 129 characters, helpfully set out for the reader in her opening pages. There are policemen, lawyers, journalists, sea captains and snake oil merchants, most of them men.

However, the book centres, as its subtitle suggests, on three women: Dr Crippen’s first wife Charlotte Bell, who died, aged 33 and pregnant, of a stroke; his second wife, a music-hall star who went by the name of Belle Elmore, for whose murder Crippen was famously hanged at Pentonville Prison; and his would-be third wife, mistress and possible accomplice, Ethel Le Neve, who lived until 1967. Not to mention the redoubtable women of the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild, who fought for their friend Belle’s sudden and unexpected disappearance to be investigated.

If this female-centred storytelling sounds familiar to readers of Rubenhold’s 2019 book, the Baillie Gifford Prize-winning The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, there is some crossover. Not least in the figure of Chief Detective Inspector Walter Dew of the Metropolitan Police, who worked on both investigations. In fact, it was reading Dew’s self-mythologising memoir, I Caught Crippen, while researching The Five that persuaded Rubenhold the so-called “cellar murder” might be the subject of her next book. But she is not trying to “reproduce the magic” of that bestseller, she insists. Story of a Murder is an altogether different tale.

Two decades separate the Ripper and Crippen cases, but while we may never know the true identity of “Jack”, the name, face and defence of Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen – “homeopath, fraudster, murderer” as per Rubenhold’s cast list – has dominated accounts of his crime for more than a century. The result has been to push his victim, Elmore, out of the picture.

Born Kunigunde Mackamotzki in poverty-stricken Brooklyn, New York, Elmore’s 37 short years took her all the way to the aspiring middle-class suburbs of Holloway, London, where she lived with the man who married her and would later murder her, burying her deboned flesh in the coal cellar of their shared home, 39 Hilldrop Crescent, before moving in his mistress the very same week.

“What drives me as a historian is the unspoken stuff. People in the past lived a dual life, as much as us”

“If you read traditional tellings of this story, it’s all Crippen-focused and that influenced my choice of title,” explains Rubenhold. “I realised as I was reading these books, they’re the story of a murderer. And that’s what so much true crime is. But we have to look at the story of a murder: a panoramic view with a wider understanding of the implications: the lives, the communities, the families it affects, but also the imprint it can leave on history.”

Rubenhold is a historian first and foremost. Born in Los Angeles, she moved to the UK to study history and art history as a postgraduate. Her first job was for the art dealer Philip Mould, just a few streets away from The London Library. “It was Philip who said: ‘This is where you’re going to be doing your research,’” Rubenhold recalls, looking out over the rooftops of St James’s Square from the Library’s sixth floor, where we meet today.

She’s now an ambassador for the Library, and considers it an “honour” to represent an institution that has “helped [her] in so many ways. The collection is so diverse and such an important resource, in part because it’s possible to take the books home. This saves a fortune when it comes to tracking down obscure texts.” She also notes that “being a writer is a lonely job” and while she’s not a Reading Room regular (preferring her favourite secluded desk near a window), she says the Library has “provided a sense of community”.

From Mould’s Historical Portraits, she became an assistant curator at the National Portrait Gallery, before embarking on a writing career. Two books on 18th-century sex workers, The Covent Garden Ladies and The Harlot’s Handbook , spawned a BBC documentary, and her next, Lady Worsley’s Whim , about an aristocratic divorce in Georgian England, became the racy television period drama The Scandalous Lady W. “What drives me as a historian is the unspoken stuff,” she says of her output. “People in the past lived a dual life, as much as us. I’m more interested in what we actually do than what we say we do. Especially in all the front rooms and domestic settings of this book.”

Story of a Murder is set at the beginning of the 20th century when “everything is changing”, says Rubenhold, who points to the speed of both technological change –motorised buses, aviation, passenger ships and Marconi wireless technology (which played a crucial role in Crippen’s capture) – but also social change, especially for women.

“In the public domain, we only talk about suffrage,” she says. “But if you think of women’s experiences at this time as a pie, suffrage is one slice. Women were entering the workforce in white collar jobs, they were empowered financially, they could live on their own… all this leads to suffrage, because it’s not until [women] have access to these things that they realise they can effect change.”

While writing, Rubenhold says she becomes “completely obsessed” with her characters. “I literally dreamt of these people every single night. Ethel in particular absolutely haunted me. You oddly have sympathy for her, but she makes bad choices in her life as, to be perfectly honest, does any killer.” She also throws herself into “every single corner” of her story – “from homeopathy to pathology”. She even made contact – “an absolute joy” – with descendants of Charlotte, the first Mrs Crippen.

During Covid lockdowns, with travel restricted and archives closed, there was a period when Rubenhold could only read secondary sources, making The London Library a lifeline for her research. “They would send you books,” she says. “I was like: ‘Hallelujah!’ At least I could keep the pilot light burning in my head for what the story was about.” She remembers, with relief, the reopening of The National Archives at Kew, where the bulk of the Crippen case material is kept. No pens or papers were allowed in, just a phone, which she used to photograph her sources during a frantic four-hour slot.

In both the primary and secondary sources, she found a pervasive narrative, that Elmore was somehow “too much” or “deserving of her own death” – in common with the Ripper victims. “Yes, the ‘asking for it’ line. It never goes

“I literally dreamt of these people every single night. Ethel in particular absolutely haunted me”

away,” she laments. “The way Belle is discussed is what happens to women who go for a night out, get drunk and get raped. ‘What was she doing? What was she wearing? What did this person do to make this happen to them?’ But no. Men shouldn’t rape. People shouldn’t murder.”

Rubenhold’s indignation is clearly a driver. “We need to look more holistically at a murder,” she says. “Not just, ‘Oh, this is a really good story.’ There is a good story here, but it’s also other things. It’s important to do true crime ethically.” She can, she says, “almost hear people groaning” at that. “‘Oh, ethical true crime! I guess that means making it boring.’ But it means creating a bigger picture. There’s all this stuff that gets pared away when you’re regurgitating a tabloid headline from over 100 years ago. These stories deserve more investigation.”

It’s here she adds a disclaimer: she is “not a true crime person” (“I find a lot of it really distasteful”), but believes the genre is evolving. “I think we’re moving away from the House

of Horror depiction of known murderers,” she says, shouting out the original Serial podcast, as well as Monsters, a drama about the Menendez brothers by writer and director Ryan Murphy. “I was blown away by that, because [Murphy] was doing exactly what I was trying to do,” she says. “It’s deeply uncomfortable: those sons murdered their parents, but the parents were physically abusing their sons in the most horrific way. The perspective moves and you get to know all the characters. Murder is difficult. Human beings are horrifically messy, you know. And we have to lean into that.”

Just without being gratuitous. In Story of a Murder, Rubenhold details the dismembering of Elmore’s body in a single paragraph – a conscious choice. “Between Belle disappearing and finding her remains, she ceases to be a human being. She is in pieces. She is so thoroughly dehumanised,” she says. “Some of this is necessary for scientific examination, of course. But when she’s also being dehumanised in court, by her husband, by the press, it becomes horrific. She ceases to be: she is hair, she is viscera, she is a bit of clothing. She is not Belle Elmore. No one deserves that.”

In one sense, this book is a righting of that wrong. Rubenhold also gives short shrift to conspiracy theorists and the television show Secrets of the Dead ’s 2008 episode Executed in Error, which claimed mitochondrial DNA evidence from a slide of Elmore’s skin proves the remains in Crippen’s cellar were not hers. Rubenhold fends off the theory with a detailed appendix from Professor Turi King, the geneticist who proved the remains found in a Leicester carpark in 2013 were those of King Richard III. Professor King highlights flaws in the methodology of the recent DNA testing. Rubenhold, for her part, believes producers were “chasing the drama”.

Scripted drama is where Rubenhold sees herself working next, with both Story of a Murder and The Five having been optioned for screen. “One of the things that drives me crazy about the Ripper thing is people constantly trying to solve the case,” she says. “It’s a waste of time. And the desire here to say [Crippen] must have been innocent. I hope this is disproved by looking at the case from all these different perspectives and really diving into the documentation.” Spoiler alert: Crippen was guilty and Elmore was not “asking for it”. “Exactly, yes,” says Rubenhold. “Mic drop, you know?” •

Nancy Groves is a writer and editor from London

“This is a classic bit of late Victorian social satire, which parodied the lower middle classes and put Holloway on the map in the decade before Harvey and Cora Crippen [aka Belle Elmore] moved there,” says Rubenhold. In 1910, the Crippens’ house on Hilldrop Crescent became a crime scene of global infamy when Elmore’s remains were found there.

Find it in: Fiction; Grossmith, George

“Memoirs fascinate me for their ability to speak directly to the reader,” says Rubenhold. “They feel so intimate and yet are so performative.” Though Inspector Dew’s “entertaining” memoir, written during his retirement, is “a tangle of embellishment, fact and total fabrication”, it is a useful insight into his personality, says Rubenhold.

Find it in: Biog; Dew, Walter

Written at a time when women were advocating for their suffrage and greater social freedoms, Wells’ novel is “a fascinating reflection of Edwardian social mores and just how rebellious young women at the time could be”, says Rubenhold. The titular character’s experience of the capital also has parallels with the real life of Dr Crippen’s mistress, Ethel Le Neve. “[She] was living on her own, enjoying her equally secretive and scandalous freedom.” Find it in: Fiction; Wells, H. G.

This “truly beautiful and moving” semi-autobiographical novel is a revealing portrait of life in Brooklyn, New York, at the turn of the century, says Rubenhold. “So much of what [Smith] wrote could apply to the life of Belle Elmore, who came from the same neighbourhood as the author and her main character, Francie Nolan.” Find it in: Fiction, 4to.; Smith, Betty

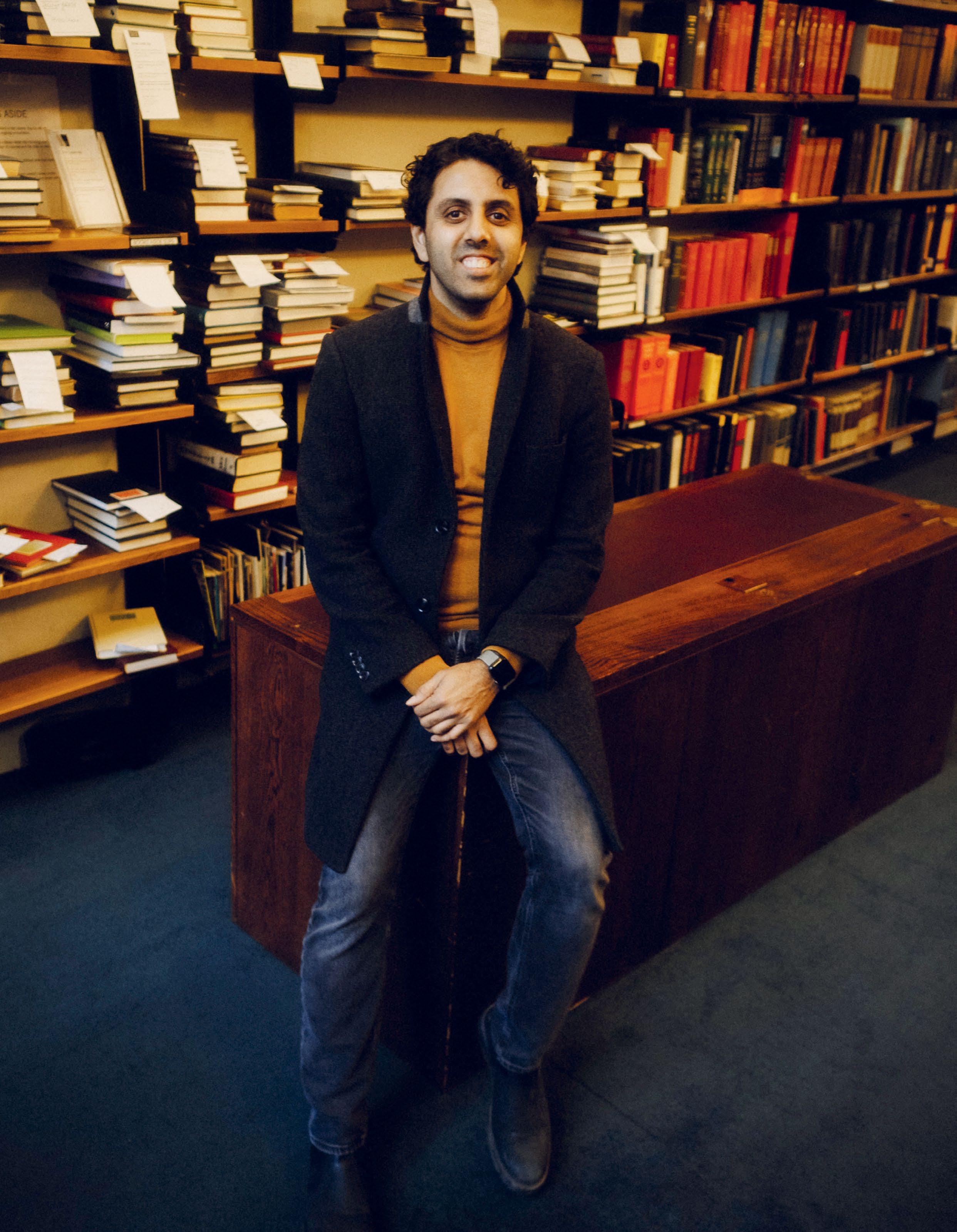

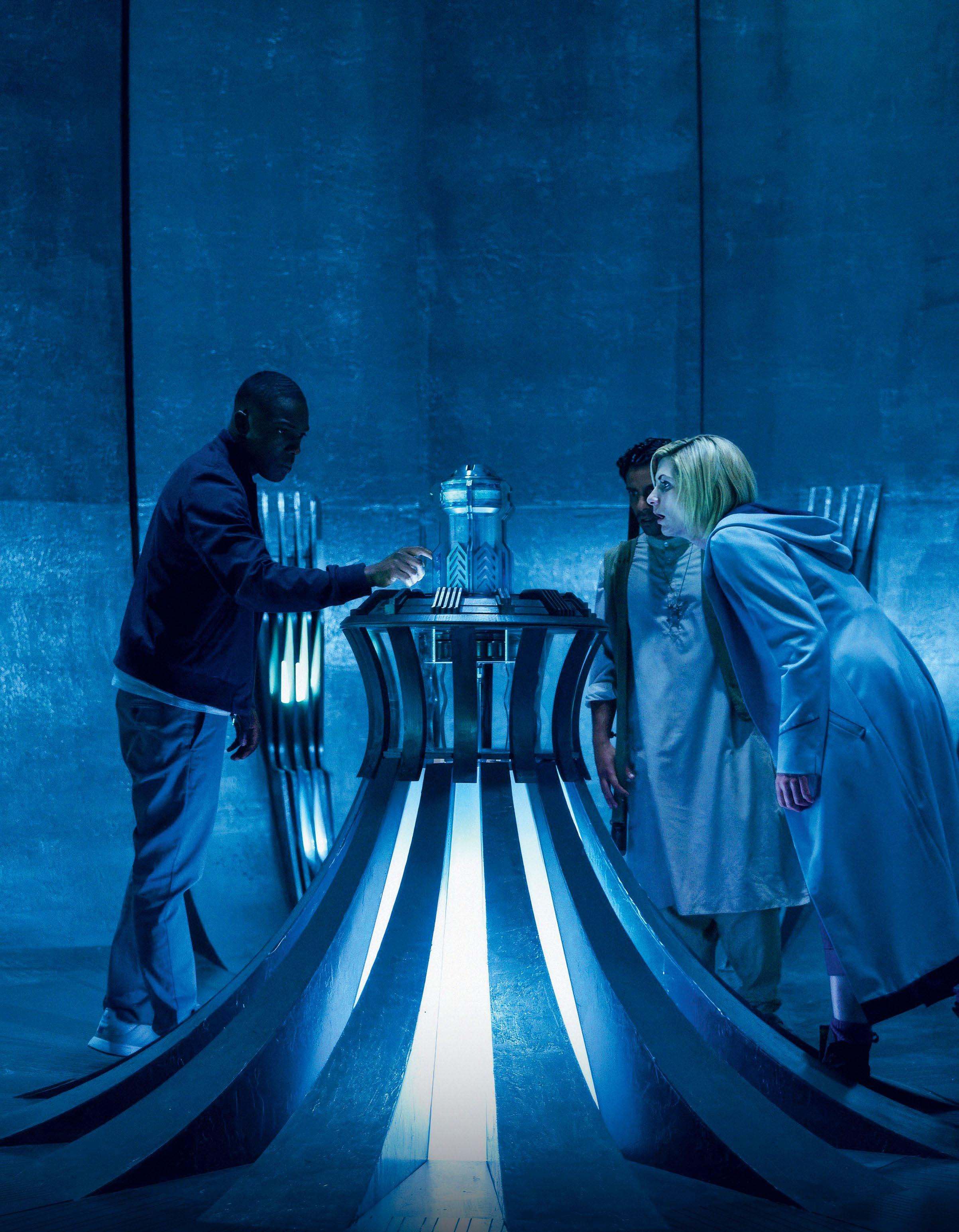

The playwright and screenwriter Vinay Patel speaks to Simran Hans about bringing Doctor Who to partition-era India and sending Chekhov into outer space

Portraits by Charles Cave

When Vinay Patel first started writing plays, he says: “There was a part of me that needed to take it seriously.” The screenwriter and playwright took the craft so seriously that each day, he would put on a “cheap black funeral suit”, walk the 45 minutes to the LSE Library in Holborn and ascend to a desk on the top floor to write. He was not a student at the London School of Economics, but enjoyed being surrounded by people who were absorbed in work that was completely different from his own. He loved the feeling that “everyone around you is going to be a future finance minister or something”.

Patel also figured that writing a play there, surrounded by “finance bros”, would probably be funny. “I’ve always tried to find a place to write that lets me plug into being a bit more studious,” he says.

It was friend and fellow playwright Katherine Soper who told Patel about The London Library, an entire decade later. “When I joined in 2022, I didn’t need to wear the suit any more,” he jokes.

Now an Associate Playwright at the Royal Court Theatre in London, Patel’s first play, True Brits, opened at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2014. At the time, he was working at a popcorn stall. He went on to make his television debut with the Bafta-winning BBC drama Murdered by My Father, about so-called “honour” killings, and has since written for Doctor Who, as well as an episode of Netflix’s hit series One Day, adapted from David Nicholls’ bestselling novel. “I love that book – I was very lucky to work on it,” he says. For the stage, Patel has written several plays including a seven-decade, three-continent-spanning epic about an arranged marriage (titled An Adventure) and an adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard , set in space. Weaving sci-fi with politics is nothing new for Patel. One of his Doctor Who episodes from 2018, Demons of the Punjab, combined aliens and a time-travelling police box with the history of India’s partition. “I spent so much time researching the episode, trying to get it as accurate as I could, because I knew it was going to be a lot of people’s first

“I got deep into a book about balloonists, because the French army had observational people in balloons”

encounter with the subject,” he says. When the pandemic hit, he was working on then-showrunner Chris Chibnall’s third series, but restrictions halted production. The subsequent period was tough for Patel. “I’d come through a period of difficulty with illness,” he says. The fatigue and brain fog that accompanied long Covid meant Patel was struggling to focus. “Suddenly, I just couldn’t deliver on time,” he says. He needed a gentle environment to reorientate himself. “I was looking for a way to take my writing seriously again that wasn’t going to a WeWork [shared office space] or rotting at home,” he says. It was around this time he landed at the Library. “At first, it was a place where I thought I was going to be very serious about writing,” he says. Patel had initially imagined the Library as a disciplined and scholarly place, the equivalent of a rap on the wrist. But the reality felt more like a hug.

Patel jokingly describes wandering the Library’s warren-like stacks before sitting down to his desk as soothing, like “a physical version of reading to the bottom of the Guardian ”. Getting lost among rows and rows of books made him feel like a child again. “The world feels bigger than you there, in a nice way,” he says. Peeking into Topology, say, and pulling a book from the shelf was a reminder that the Library might lead him to new ideas through a process of discovery and play. “The act of being in a space where there’s so much expertise about something you know nothing about is really exciting,” he adds. “You never know what you’ll stumble on.”

Patel began spending more time at the Library, which was starting to feel like a haven. On Saturdays, he’d sit in the Reading Room all day “in an armchair and read a play and doze off”, he says, chuckling. As he felt more like himself, the writing started to flow. He’d spend gloomy days looking up at the skylight in the Foyle Lightwell Reading Room, allowing ideas to trickle

down. He redrafted “an adaptation of The Cherry Orchard that was set on a spaceship, and everyone was brown”, a project that had stagnated during lockdown, and adapted a young adult novel set in 19th-century Cairo. “I got deep into a book about balloonists, because the French army had observational people in balloons,” he says. “I didn’t know places like this still existed. I’ve been in London nearly my whole life. That has mostly been a journey of watching nice things disappear.”

The youngest son of two Gujarati pharmacists, Patel grew up in “the hinterlands of southeast London”, in Bexley. As a child, he was introspective. He took pictures with expired disposable cameras he found in his dad’s pharmacy and developed them in its photo lab. At the kitchen table, he’d write stories; in his bedroom, he’d read. In the living room, Patel watched television with his grandparents. He remembers seeing Star Wars at Christmas with his late grandmother. “I could tell they didn’t really know everything that was going on,” he says, but it never stopped them connecting with what was on screen. As a teenager he rewrote the script of The Matrix, setting his version in Dartford, the town he travelled to for school. “I loved trying to fashion my own realities,” he says, adding that: “It was a way out of a suburban life.”

Patel jokes that he convinced his father to let him apply to study English by telling him it was a “more employable degree than business studies”. But, even then, Patel’s ambition was serious. Desperate to escape his hometown, he drew a 200-mile radius around it on a map.

He knew he wanted to be somewhere that wasn’t here and was struck by the beauty of the South Downs, which felt a million miles away from London. A girl he was dating had applied to the University of Exeter, so he added it to his list. “I ended up flipping a coin between the University of East Anglia [UEA] and Exeter,” he recalls. When the

coin came down as UEA, he flipped it again. Exeter, Patel says, turned out to be exactly the right choice.

Many years (and libraries) later, Patel began work on a project for the stage about the filmmaker George Lucas and his former wife, the film editor Marcia Lucas. “I’ve been writing a play about the 1970s American filmmaking scene and American Zoetrope,” he says, referring to the production company Lucas co-founded with Francis Ford Coppola. It began as an exploration of how the guy who was supposed to make Apocalypse Now became the guy who wrote Star Wars, he says, but as he delved deeper into the research, Marcia emerged as a protagonist. He combed the Library’s collections for biographies on the New Hollywood scene, citing Dale Pollock’s biography Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas as a key text. “It was supposed to be an authorised biography of Lucas and then he read it and was like: ‘Make it unauthorised!’” he says, cackling, “which is actually great as a source.” Information on Marcia, however, was more elusive. “She basically became a recluse after they divorced, so I spent a lot of time on the internet and in the Library,” he says. He trawled through articles about female film editors, describing the process as “like trying to see the light around a black hole”.

Patel says it was a Monday, one of the days when the Library closes late, when he finished writing the play.

“I had worked a 10-hour day,” he remembers. Quietly, he slammed through the draft. “I love being able to stay in that one spot and keep my focus.”

Patel says that the thing he misses about being a new writer is that no one expects you to be an expert. “It’s a journey of discovery,” he explains. He met David Byrne when Byrne was the Artistic Director of the New Diorama Theatre in Camden; when Byrne took over at the Royal Court in 2024, he hired Patel as an Associate Playwright. Alongside six other writers, Patel is part of a leadership team whose role is to shape the direction of the theatre, and to mentor and train new talent. He says the key to doing good work is knowing what it’s for. Murdered by My Father was “about shame and pride”, he says, comparing it to Arthur Miller’s 1955 play A View from the Bridge. “Writing a partition episode of Doctor Who, I knew what that was for,” he says, adding that the Royal Court has given him a renewed sense of purpose. “As someone who didn’t grow up with theatre, to now work in one of the most influential writing buildings in the world feels really validating,” he says. “I wish my grandparents were still alive to see that.” •

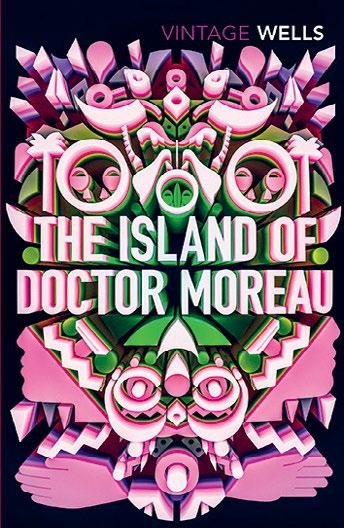

This story of a shipwrecked man discovering a scientist’s horrifying genetic experiments has been adapted several times, but Patel would like to take on the mantle, too. He says: “There’s a lot more than gun-toting bison within Wells’ strange, creepy exploration of faith and science.”

Find it in: Fiction; Wells, H. G.

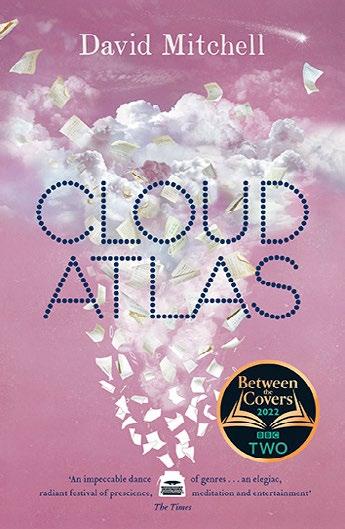

Mitchell’s epic, which unfolds via six stories about characters separated through time but interconnected through fate, makes “a troubled world feel more hopeful”, says Patel. He is adapting it for the stage and describes it as “one of the most maddening pleasures of [my] career”.

Find it in: Fiction, 4to.; Mitchell, David

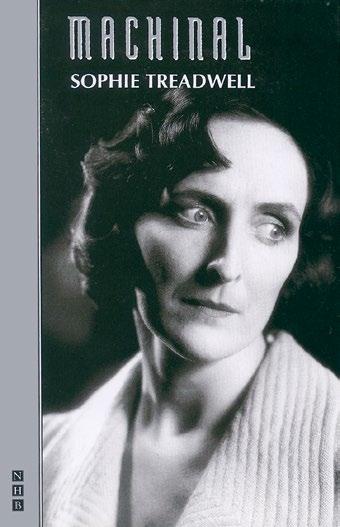

After watching a “riveting” revival of Treadwell’s play based on the life of Ruth Snyder, who was executed by electric chair for the murder of her husband, Patel believes “there’s an incredible film to be found there”. He says: “There’s so much that’s unfortunately still relevant in this masterpiece nearly 100 years after it was first staged.”

Find it in: L. English Drama; Treadwell, Sophie

This “woozy, vivid tale of romance across time and tribes” is told through letters passed between two rival timetravelling secret agents. Unfortunately for Patel, the authors are adapting the book themselves. “[They] will do a phenomenal job,” he says. “I’ll be first in line to see it.”

Find it in: Fiction; El-Mohtar, Amal

020 7401 2405

From 1st – 12th October 2025 10:30am - 5pm (including Sundays)

A loan exhibition in celebration of Wartski’s 160th anniversary Free entry Catalogues £10 for the benefit of The King’s Trust Janiform fibula, 1st-2nd century A.D. Rupert Wace private collection. Shown life size.

wartski@wartski.com

Hear about King James I’s court favourite from biographer Lucy Hughes-Hallett and explore textile art with Tate Britain and Barbican curators

30 April

COMPLEX RELATIONS: BRITAIN AND RUSSIA ACROSS THE CENTURIES

Historian Barbara Emerson, novelist Marcel Theroux, and journalists Luke Harding and Giles Milton discuss the complicated relationship between Britain and Russia, from the 19th century to the present day.

7pm – 8pm, in person

7 May

THE STUART STORY WITH LUCY HUGHES-HALLETT AND DR ANNA KEAY

The Stuart period was a dramatic century marked by dynastic intrigue, religious strife, civil war and regicide. Join authors and Library members Lucy Hughes-Hallett and Anna Keay for a discussion on the politics and personalities of the 17th century. From King James I and his “favourite”, the Duke of Buckingham – on whom Hughes-Hallett published a critically acclaimed biography last year – to the extraordinary decade following the execution of Charles I in 1649.

This is a London Library Patrons event. If you would like to become a Patron, please contact patrons@ londonlibrary.co.uk

6.30pm – 8pm, in person

15 May ART/LIT SALON: TEXTILES/CULTURE

Dominique Heyse-Moore, Senior Curator of Contemporary British Art at Tate Britain, returns as host of the regular Art/Lit Salon. This edition features visual artist and writer Himali Singh Soin, winner of the 2019 Frieze Artist Award, and Wells Fray-Smith, curator of Unravel at the Barbican, discussing the intersection of textiles, politics and cultural identity as part of London Craft Week.

6.45pm – 8.45pm, in person

3 June

We are grateful to be able to offer an exceptional day trip to discover the literary and artistic treasures of Boughton House, hosted by its owner, the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, a London Library member. The stately home, known as “The English Versailles”, houses

a remarkable collection that offers us a glimpse into centuries of literary and historical heritage.

From illuminated manuscripts to rare first editions, its library reflects the scholarly pursuits and cultural passions of generations of the Montagu and Buccleuch families. The Duke will provide personal insights into the library’s history and some of its most notable volumes, offering a unique perspective on one of Britain’s finest private book collections.

This is a London Library Patrons event. If you would like to become a Patron, please contact patrons@ londonlibrary.co.uk

10am – 3pm, in person

5 June

PRESERVING CULTURE IN CONFLICT

In the lead-up to Refugee Week (16–25 June), Sudanese author Yassmin Abdel-Magied, EritreanEthiopian-British novelist Sulaiman Addonia, Ukrainian historian Dr Olesya Khromeychuk

Palestinian

discuss their endeavours to hold onto the foundations of their cultural heritage and identities in the face of war and devastation.

7pm – 8pm, in person

6 June WRITE & SHINE: CITY OF MEMORIES –VIRGINIA WOOLF AND PATRICK HAMILTON

Start your day with a burst of creativity. Join Write & Shine bright and early, live from The London Library for a 90-minute virtual writing workshop that explores literary London.

7.45am – 9.15am, online

For more information, and to be the first to hear about events at the Library, refer to the fortnightly newsletter, scan this QR code or visit londonlibrary.co.uk/whats-on