By the Alumni of The Ohio State University School of Communication

Turning the page

The Lantern begins new chapter with newsroom dedication

Featuring articles from 21 Lantern alumni

Dateline Columbus: The Lantern celebrates new newsroom, turns the page to new era

By Chris Davey

It’snot every day that a newsroom gets a new home — especially when it has been more than half a century since the last one. I guess you could say it’s breaking news.

This commemorative edition of The Lantern — produced entirely by alumni from the past seven decades — celebrates the opening of a modern newsroom designed to serve the next generation of journalists and storytellers at Ohio State. On our cover, you’ll see the 1925 masthead of The Lantern, a nod to the deep roots of this publication and a reminder that, while tools and technologies change, the mission of journalism endures.

From its founding, The Lantern has taught, supported and always attempted

to uphold the bedrock values of American journalism: freedom of the press, freedom of expression, the marketplace of ideas, and the role of the institution of journalism — the fourth estate — in sustaining democracy.

In recent decades, journalism has faced historic challenges. Technological disruption has transformed how news is gathered, delivered, and consumed. Economic pressures have closed newspapers, reduced newsroom staffs, and undermined the resources needed for sustained investigative work. Perhaps most troubling, bad actors have worked to erode public trust in news organizations, spreading the notion that facts are optional and truth is subjective. Artificial intelligence could exacerbate this in dangerous and unpredictable ways. The antidote to these forces is the same as it has always been: rigorous, ethical, and fearless reporting.

Student journalism plays a crucial role in this landscape now more than ever. It trains the next generation of journalists not only in the craft — inter-

Honoring Our Hosts for This Milestone Event

This commemorative edition of The Lantern was published to celebrate the opening of the new Lantern newsroom in the Journalism Building, as part of the first-ever all-alumni reunion for The Ohio State University School of Communication.

Thank you to our Host Committee for their generous support of this historic event:

Honorary Chair: Adrienne Roark (1993 B.A. Communication)

Deputy Honorary Chair: Akayla Gardner (2021 B.A. Journalism)

Kevin Adelstein* (1990 B.A. Journalism)

Roger Bolton* (1972 B.A. Journalism)

Linda Thomas Brooks* (1985 B.A. Journalism)

Larry Burriss (1971 B.A. Journalism; 1972 M.A. Journalism)

Chris Davey* (1994 B.A. Journalism; 2003 M.A. Journalism Communication)

Robert Dilenschneider (1967 M.A. Journalism)

Jocelyn Dorsey* (1972 B.A. Journalism)

Zuri Hall (2010 B.A. Strategic Communication)

Susan Henderson* (1979 M.A. Journalism)

Sandy Hermanoff* (1965 B.A. Journalism)

Gretel Johnston (1983 B.A. Journalism)

Jeff Kamin* (1972 B.A. Journalism)

Kelly Hibbett Kavanaugh (1982 B.A. Journalism)

Barbara Levin (1973 B.A. Journalism)

Cal McAllister (1993 B.A. Journalism)

Kim McBee (1989 B.A. Journalism)

Patty Miller* (1972 B.A. Journalism)

Rich Moore* (1980 B.A. Journalism)

John Oller* (1979 B.A. Journalism)

Shawn Ramsey (1984 B.A. Journalism)

Jay Smith* (1971 B.A. Journalism)

Kate Stabrawa* (2002 B.A. Communication)

Trevor Thompkins* (2016 B.A. Strategic Communication)

Jeffrey Trimble (1978 B.A. Journalism; 1982 M.A. Journalism)

*Member of The Ohio State University School of Communication Advancement Board

viewing, fact-checking, storytelling — but also in the habits of mind and ethical grounding necessary for the work. But its impact goes beyond those who choose the newsroom as a career. For generations, The Lantern has shaped Buckeyes who have gone on to work in law, medicine, business, public service, education, and countless other fields. The discipline of reporting, the habit of questioning assumptions, the appreciation for evidence and clarity — these are assets in any profession, and The Lantern has been one of our nation’s most enduring incubators of such skills.

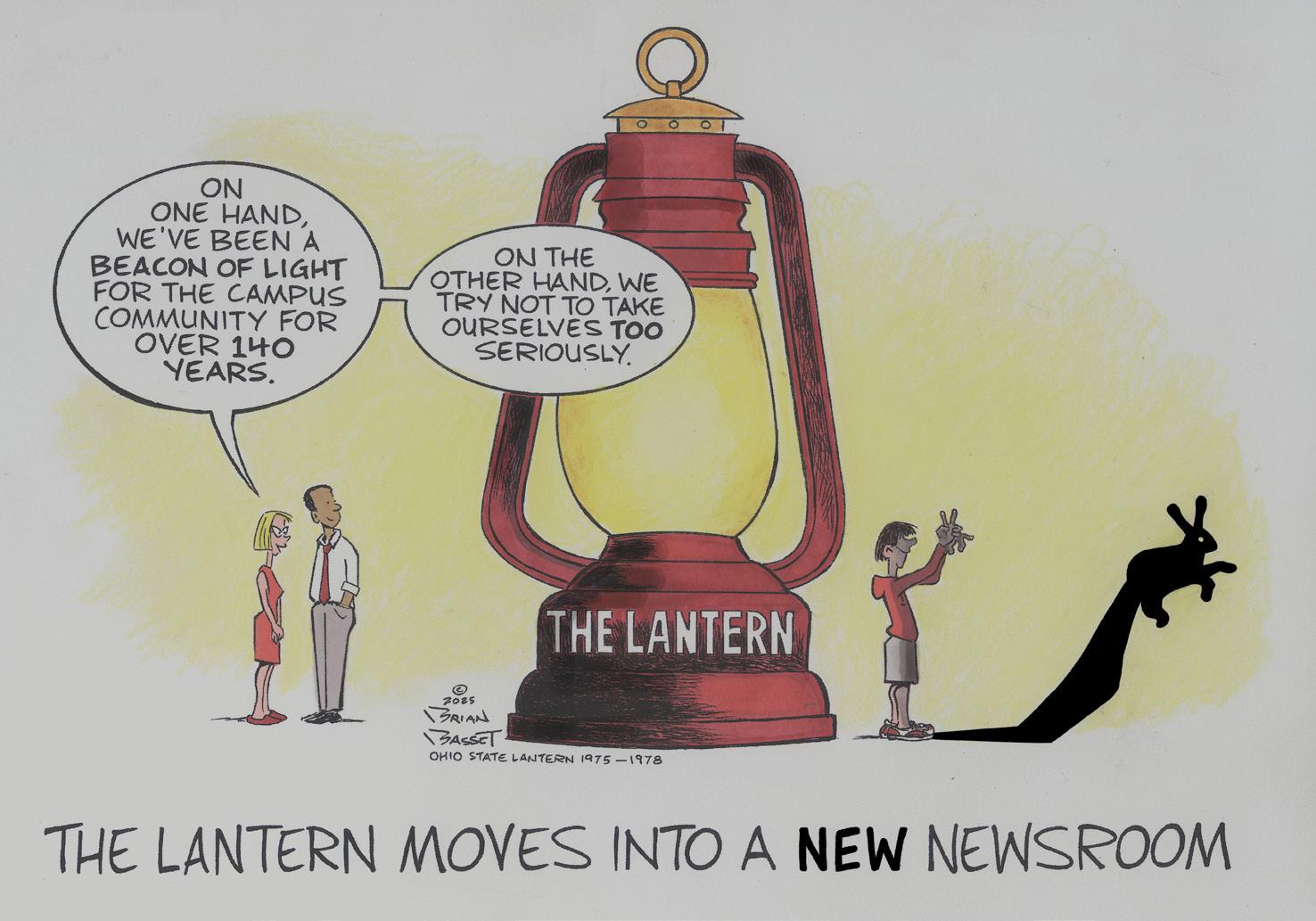

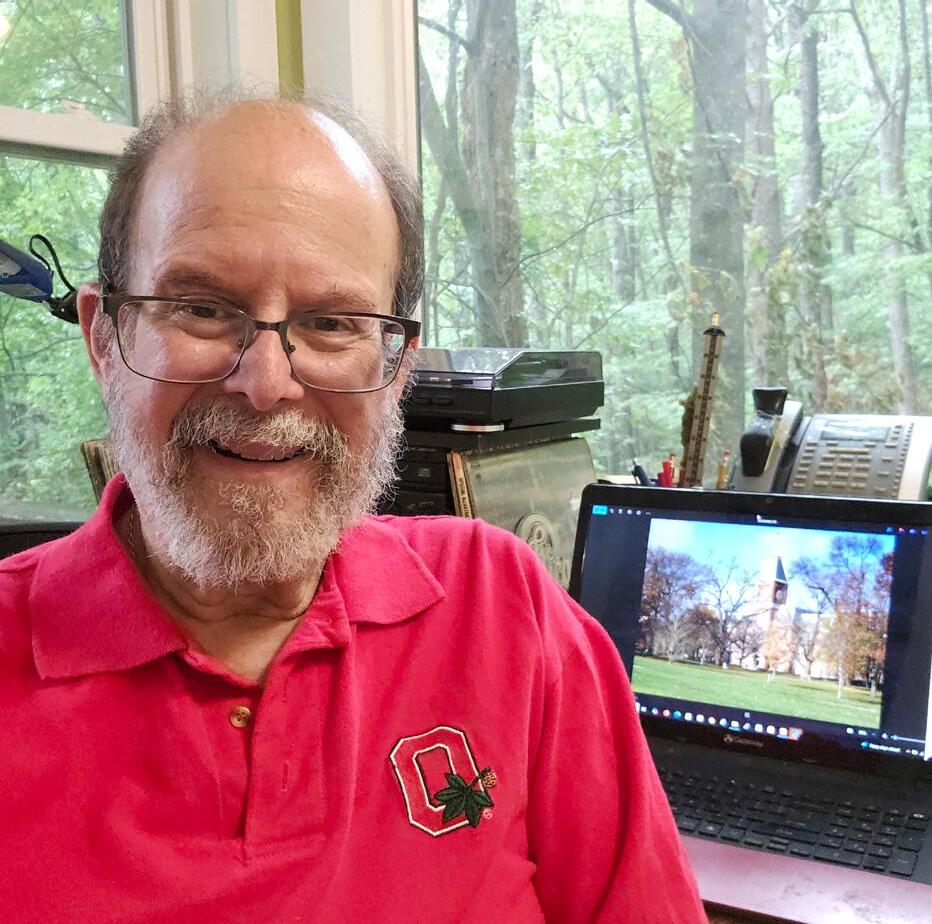

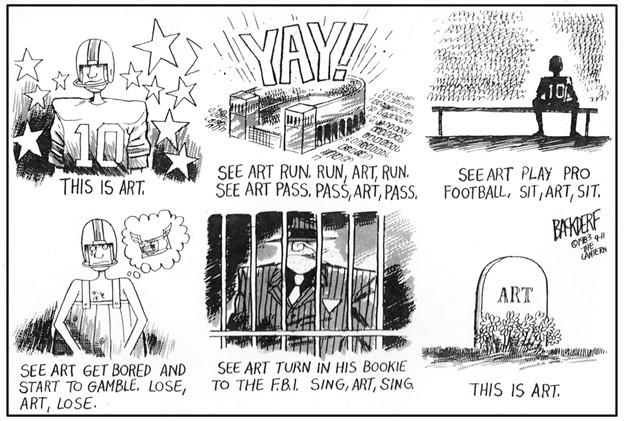

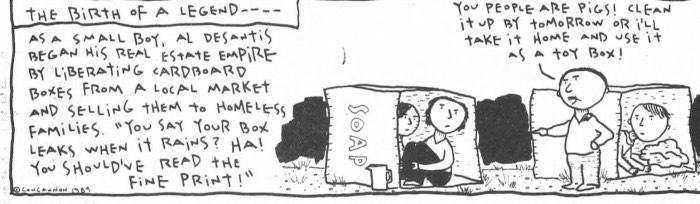

The newsroom has always been a place of seriousness and purpose, but also one with an irreverent streak that reflects the energy of its staff. That energy has helped produce an extraordinary roster of alumni, including Pulitzer Prize winners, renowned photographers, celebrated columnists, Hollywood writers (one even appeared on the gameshow Hollywood Squares) and some of the most recognized editorial cartoonists in the country. It is no coincidence that this edition features two cartoons emblematic of that tradition: a new piece created by Brian Basset, who drew for The Lantern in the 1970s, and a classic by

Derf Backderf from the 1980s, appearing alongside his retrospective. Their work is a reminder that journalism can be both serious in purpose and inventive in form.

The pages that follow offer a rich retrospective on The Lantern’s past, told by the people who lived it. You’ll read about landmark investigations, campus controversies, newsroom innovations, and the ways The Lantern has reflected — and sometimes shaped — student life. You’ll also encounter the humor, camaraderie, and occasional chaos that come with producing a daily paper on deadline. Together, these stories capture the enduring spirit of a newsroom that has been at once a training ground, a crucible and a community.

This new newsroom is not simply a change of floors and decor — it’s an investment in the future of journalism. Its design supports collaboration, multimedia production, and the kind of cross-disciplinary work that modern newsrooms demand. It is a space built to adapt, to welcome new technologies, and to continue The Lantern’s role as both a laboratory for learning and a source of

NEWSROOM continues on Page 3

essential information for the Ohio State community.

None of this would be possible without the dedication of countless people over the decades: the students who have put in long nights to meet a deadline; the faculty advisers who have mentored and challenged; the faculty who have taught the fundamentals, the alumni who have given back with their time, expertise, and support; and the donors whose generosity has made this new chapter possible.

The Lantern is a proud part of Ohio State’s world-class School of Communication, ranked No. 1 nationally and No. 2 globally in its field. The school is recognized for rigorous, high-impact research in areas such as political communication, digital technology’s role in society, and health and risk communication. Its programs prepare students to lead in journalism, strategic communication, marketing, public relations, and related disciplines. This celebration of the new Lantern newsroom is part of the school’s first-ever All-School Reunion, bringing together alumni from all of its diverse programs to honor both the school’s scholarly achievements and its legacy of hands-on training that produces leaders in Ohio and around the world.

As you turn these pages, you’ll see why The Lantern matters — not only to those who have worked in its newsroom but to the broader public it serves. In an era when the flow of information can be overwhelming, and misinformation can spread with alarming speed, the role of credible journalism is more vital than ever. The skills learned here will travel far, carried by graduates into newsrooms, boardrooms, courtrooms, and classrooms across the state and around

the world.

This commemorative edition is both a look back and a look forward. It honors the traditions that have defined The Lantern while embracing the innovations that will shape its future. We invite you to celebrate with us — not just the opening of a beautiful new space, but the enduring mission of the newsroom it houses. Special thanks to the alumni who contributed their stories; to my co-editor John Oller for his painstaking and patient research, writing and editing; to Lantern Adviser Spencer Hunt for all of his insights and guidance; to Lantern alum Reid Murray for exceptional design and layout; and to Lantern Web Editor Chloe Limputra, our digital editor. And lastly, thank you to the outstanding Director of the School of Communication Kelly Garrett and all of the faculty of the School of Communication and the former School of Journalism past and present who shaped generations of communicators, researchers and journalists.

For 144 years, The Lantern has told the stories of Ohio State and our community. With this new newsroom, it is ready to keep telling them — accurately, independently, and with the tenacity that has always defined it. Here’s to the next half-century, and to the generations of Buckeyes who will write, edit, photograph, design, and publish the stories that matter.

Editor’s Note: Chris Davey (1994 B.A. Journalism; 2003 M.A. Journalism Communication) was editor in chief of The Lantern in 1993 and is a former spokesman for Ohio State and the Ohio Supreme Court. He is founder and partner of 30PR and Chair of the School of Communication Advancement Board.

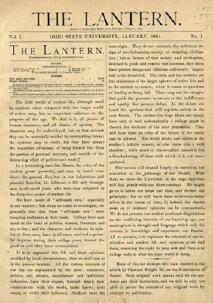

1881

The Lantern is launched as a privately-published, monthly, 12page glossy magazine, taking its name from a Paris newspaper, La Lanterne. The goal is “to shed light on all subjects.”

In its initial years The Lantern is published by members of the English Department and other campus organizations and operated

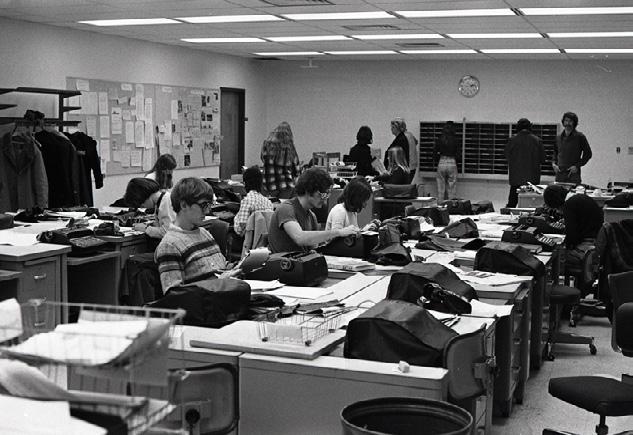

The end of an era — and a new home for The Lantern

By William Moody

Thephone rang.

As Emma Wozniak, editor-in-chief of The Lantern, was leaving a Thursday morning class earlier this year, an Ohio State spokesperson called her with breaking news.

Wozniak spent the next 10 hours in the conference room of The Lantern, organizing journalists, transcribing interviews, securing photos, editing articles and posting on social media.

Like any other day, she was a student journalist, but today, she felt like a real journalist, too.

Wozniak is one of countless students who have learned the reporting trade working for The Lantern. Since 1924 — 101 years ago — the Lantern newsroom has been on the second floor of a building located at 242 W. 18th Avenue. Beginning in 1974, when the original building at that site was gutted, remodeled and enlarged with a third floor, the Lantern newsroom continued to operate on the second floor — from Room 271, versus Room 216 in the old building. But whether you view The Lantern’s current second floor home as literally 51 years old or figuratively 101, it’s now about to change.

One floor below, a new newsroom is opening today that will carry on the tradition of developing the next generation of young journalists. It leaves behind the rich history of Room 271

out of fraternity houses and other off-campus locations (no typewriters yet!).

Editors are elected by the school’s literary societies. The paper is offered by subscription at one dollar a year or 15 cents for single copies. Editors, writers and business personnel share profits and losses.

in the Journalism Building and its predecessor.

As an independent news laboratory, The Lantern teaches students like Wozniak the theory of journalism and gives them the opportunity to practice their craft.

“Hundreds or thousands of people read on our website in a week, and that is not something that should be taken for granted or a responsibility that should be taken lightly,” Wozniak said. Over the course of 101 years, the Lantern newsroom has evolved to meet the needs of an ever-changing profession. In 1974, the reconstructed newsroom was enlarged and included technological innovations such as electric typewriters. There were separate rooms for wire service machines, a photo lab, and a room affectionately known as “the morgue.” It was a small room off to the side of the main newsroom where a library of past editions and articles from The Lantern were stored for future writers to review.

ERA continues on Page 23

1891

The Lantern is made a weekly paper and is printed commercially downtown.

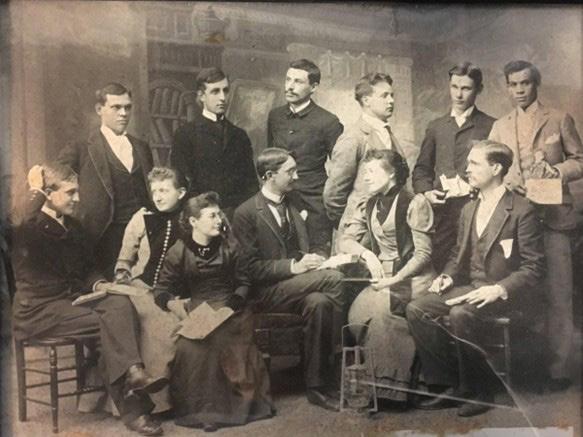

Left: The Lantern staff, 1892. Business Manager Fred Patterson (back row, far right), the son of an escaped slave, was among the first African Americans to attend Ohio State.

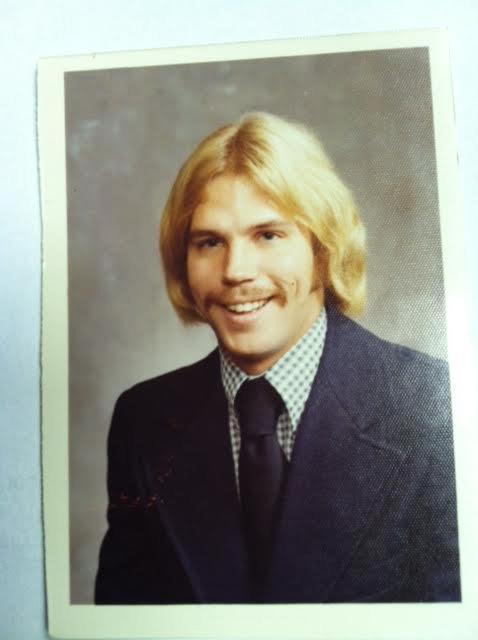

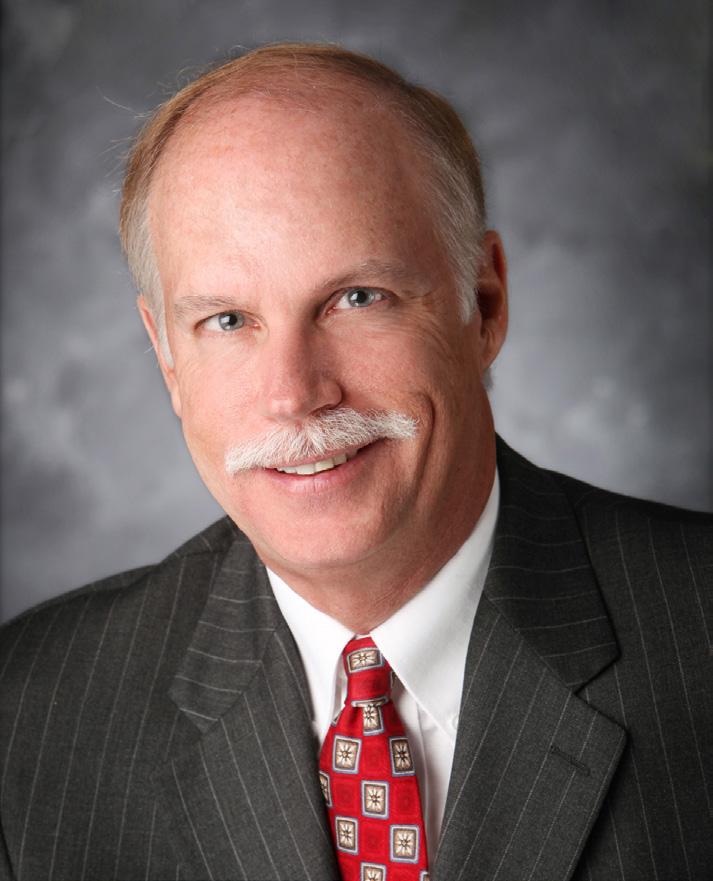

By Jay Smith

BobKinney was sick and in no shape to write the tribute to the football team that had dazzled us for three seasons. It was to be the final piece in our Jan. 1, 1971, Rose Bowl edition. Seven of us had traveled to Pasadena, California (I was editor-in-chief), to publish for Buckeye fans to root their team to a second national championship in three years.

So, I grabbed my portable typewriter and headed for the bathroom, so as not to disturb my sick roommate. “Rex & Co. End an Era,” read the front-page headline, a reference to Rex Kern, the charismatic red-headed quarterback who led the “Super Sophs” for three seasons with one loss. When the day ended, they had lost two.

Rose Bowling

On New Year’s Eve we distributed 11,000 copies of The Lantern to a dozen hotels housing the Buckeye faithful. Our predecessors two years earlier had greater luck with their Rose Bowl edition. They beat Southern Cal and O.J. Simpson. We lost to Stanford and Jim Plunkett.

The 12-page edition included an interview with Anne Hayes, wife of the head coach, a report that 4,000 Buckeyes alums lived in Southern California, news from back home and too many tributes to the team.

That wasn’t the only time we made

1892

Heavily in debt, and lagging in student support, The Lantern is relaunched as a twice-weekly paper renamed the “Wahoo.” Because an Ohio State football team had been started in 1890, and the popular college

Lantern history at the close of 1970. In December, both Columbus newspapers were shut down for 11 days due to a Teamsters Union strike. As a result, The Lantern became the only newspaper outlet for local advertisers. Demand for advertising space during the Christmas season was so great that on December 11, the last day of the school year, we put out an unprecedented TWO editions in a single day. The thousands of newspapers were available at noon that day, on campus and downtown. We reasoned that we were filling a news void.

yell was “wahoo,” the editors attempted to capitalize on the name in a bid for greater circulation. The Wahoo’s editor-in-chief was a woman, Catherine Morhart of the Browning literary society.

On top of that, the additional ad revenue helped finance our Rose Bowl trip.

Every day brought new lessons to those of us who were Lantern staffers. The best lessons were learned in the heat of battle. Our adviser, Bill Rogers, often had to bite his ever-present pipe as we practiced journalism.

I’ve said to each of the last seven Lantern editors I’ve mentored

1893

Under pressure from alumni, the paper is restored to its original name, The Lantern, which has appeared on the masthead ever since.

1901

The Lantern describes itself as “the least appreciated and most maligned” of all OSU student organizations.

and there is no such thing as a student journalist. We are all journalists, given the jobs we do and the lives we touch.

I revel in how many on that trip went on to great careers in journalism. Lou Heldman, our city editor — my best friend and the person who introduced my wife Susan and me (Susan was also a product of the J-School) — served a distinguished career with Knight Ridder. Roger Mezger, the news editor, worked in Akron and Cleveland for newspapers. The aforementioned Bob Kinney became sports editor at The Toledo Blade. Pam Spaulding, the photographer on the Rose Bowl trip, became an award-winning photographer in Louisville.

There were others, too many to mention, which means some get left out.

To all of them, I say thanks for shaping the journalist I became.

Editor’s Note: Jay Smith (B.A. Journalism, 1971), worked for 38 years for Cox Newspapers, 16 of them as president of the newspaper chain, which included 17 dailies and 25 weeklies. Now retired, but a busy mentor of Lantern editors-in-chief, he lives in Atlanta.

1914

Ohio State University takes over operation of The Lantern as a weekday daily laboratory paper and moves the newsroom to the basement of the original University Hall. The university takeover was prompted by Ohio governor James M. Cox’s re-

action to a student editorial criticizing him. At Cox’s urging, OSU President William Oxley Thompson establishes the Department of Journalism (under the College of Commerce) and tells its head to censor any editorial criticism of the governor.

By Roger Mezger

For144 years now, working for The Lantern has taught student journalists valuable life lessons. As a Lantern reporter in 1970, two lessons really hit home for me.

• When you have smart editors who see and pursue big stories, try not to disappoint them.

• What you, the reporter, see as “a story” is sometimes a very painful, life-altering experience for the

Lantern lessons

people in that story. Don’t check your humanity at the door.

On Sunday morning, May 3, 1970, I was in the Lantern newsroom finishing up a story. The previous night at Kent State University, student protests against the war in Vietnam had escalated and the ROTC building had been burned to the ground. Suddenly I was being asked to drive to Kent to check it out.

But other than Gov. James A. Rhodes’ inflammatory press conference and clusters of National Guard troops here and there, the Kent State campus looked pretty normal that Sunday afternoon — nothing at all like the violent, potentially lethal tinderbox that was Ohio State on April 29 and 30.

Sunday night was quite different, though, an eerie sight with skirmishes and tear-gassing on the edge of campus and helicopters lighting the scene. The campus was under curfew, so I spent a mostly sleepless night in the Daily Kent Stater newsroom, just me and the ever-ringing phones.

Around mid-morning May 4, all seemed calm again. One of the Stater editors advised that a protest rally planned for noon probably wouldn’t amount to much. Nothing to see here, so I headed back to Columbus. In the Lantern newsroom I found assistant managing editor Lou Heldman and some others huddled around the wire machines.

“We have someone there!” I heard Heldman say. Then he saw me, and there was nowhere to hide.

Months later, on Saturday, Nov. 14, the phone in my apartment on East Norwich rang at around 11:30 p.m. The plane carrying the Marshall University football team had crashed in West Virginia. Lantern Editor-in-chief Jay Smith was talking me into heading to Huntington.

It was a lot for a 20-year-old to cope with. A smoldering DC-9 upside down in the trees. The sickening smell of burnt flesh and jet fuel. The body bags lined up in an airport hangar,and everywhere, stunned, grieving people. How to approach them? This time I got a story. But it was far different from any reporting class.

Journalism textbooks helped teach us the basics. Our real-world experiences as Lantern staffers taught us so much more.

Editor’s Note: Roger Mezger graduated in 1972 and was The Lantern’s editor-in-chief Winter Quarter 1972. He worked 38 years as a reporter and editor at the Akron Beacon Journal and The Plain Dealer in Cleveland. He lives in Akron.

1918

The first two students to earn Bachelor of Science in journalism degrees graduate.

1924

The journalism department and The Lantern move into a brand-new two-story building at 18th and Neil Avenues, the same plot of land as the current Journalism Building.

A professor described the accommodations as “unsurpassed.” The newsroom was

on the second floor, with windows facing east. An enlarged print shop occupied the first floor. The side entrance on 18th Avenue was used as the main entrance, hence the address of 242 W. 18th Avenue.

Left: The Lantern’s new home in 1924

By Patricia Boyer Miller

Butfor The Lantern … I probably wouldn’t have graduated from Ohio State.

As a small-town Ohio girl in the ’60s I did what I was taught in school. I took lots of notes, raised my hand, used correct grammar and got good grades. I took typing because I was told every girl should.

But for The Lantern

The chances of going to college were slim and the odds were against leaving that hometown. But I loved to write, and I wrote a story about my locker as if it were alive.

It was titled “Ode de Locker,” and I didn’t even know French. My high school English teacher loved it. She asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I told her a teacher or a nurse since that’s what girls did. She told me I could write, nursing was hard and teachers couldn’t get jobs. How about journalism? I didn’t know what that was.

I signed up for her journalism course and the school newspaper. The summer of my junior year I attended a journalism camp at Ohio State. I lived in Taylor Tower, attended classes on news reporting, photography, public relations and broadcasting. I met the journalism faculty and befriended students from all over Ohio. The journalism newsroom was organized chaos, and I loved it.

My English teacher encouraged me to apply to Ohio State, which I did. That was in 1968. I took Reporting 101, where we learned real-world skills — question everything, get the facts, check the facts, and remember who, what, when, where and why. Be objec-

tive. I knew I was ready to be a Lantern reporter.

When assignments were handed out, I took whatever I could get — mostly human-interest stories. I wrote about bats in the belfries around campus hoping to get the attention of the editor, Jay Smith. Those antiwar demonstrations on campus sure seemed more interesting, but I had a lot to learn. My first article came back from the copy editor and it looked like it bled out from all the handwritten, red ink corrections. I quickly learned to read copy edit marks and accept feedback. I was so proud when I saw my first byline and all those that followed. My name on a story was a reminder that I was responsible for fact finding and fairness to the 40,000 Lantern readers.

The old Lantern newsroom I knew from 1968 to 1972 had no air conditioning, no computers, old furniture, no electricity at times, a few landline phones, and clutter everywhere in a smoke-filled room. A far cry from the state-of-the-art newsroom opening today! But my time there helped me transition from my small hometown high school of 500. I could do what I loved to do with people who had similar interests.

Before I graduated in 1972, I was named editor of The Buckeye, the monthly OSU newsletter for the 18,000 nonacademic staff. Fresh off The Lantern, I used all my new skills including researching, writing and editing; taking and developing photos; meeting deadlines; cutting and pasting layouts;

and then final editing before printing. After almost five years it was time to give up my monthly publication and football tickets and move into the corporate world, where I have spent almost 50 years. Not a day goes by that I don’t practice my journalism skills. But for The Lantern? I wouldn’t be where I am today.

Editor’s Note: Patricia Boyer Miller (B.A. Journalism, 1972) was most recently, and for 16 years, COO/President of Nobel Learning Communities, a national network of more than 200 private preschools and K-12 schools. She now serves as an adviser and board director for six for-profit and nonprofit boards. She also funds an endowment for Special Lantern editors who focus on investigative reporting. She divides her time between Wayne, PA, Naples, FL and a small town on Prince Edward Island, Canada.

1927

The Department of Journalism becomes a school within the College of Commerce and Administration.

The Great Depression lands The Lantern in debt again. The summer Lantern is suspended, not to resume until 1958. To defray costs, laboratory journalism students are charged quarterly fees of four dollars, although they receive The Lantern for

1933

free, unlike other students who pay three dollars for a yearly subscription.

During this decade, all was not doom and gloom. A “Rib ’n Roast” dinner in the spring became an annual affair. At the dinner, a burlesque issue of The Lantern

— called “The Latrine” — was distributed and professors were lampooned. At the end of the dinner came the announcement of scholarship awards, a tradition that continues each spring today (minus the jibes).

By Lou Heldman

AtConfessions of a Lantern legend

the 2022 Lantern reunion, a younger alum began our conversation: “You were a legend. Is it true you lived in the newsroom for four years and never went to class?”

Not true, but uncomfortably close. I often skipped non-journalism classes and barely graduated, having failed or withdrawn from feeble attempts to learn Spanish, French, Italian, Hebrew and algebra.

There were kids like me every year, intoxicated by journalism to their academic detriment.

Remarkably, I had a clear vision in my early teens that I would go to Ohio State, report for The Lantern and go to work on a big city newspaper. And that’s what happened.

During freshman orientation, I found my way to the newsroom and met summer edition editors Jennie Buckner and Christine Jindra, who seemed more like polished professionals than college students. .

One asked me about my journalism experience in what seemed like a skeptical tone. I declared I had just concluded a strong run on my high school weekly, The Bulldog Barks. I was mortified by that silly name, even as I said it.

They told me I could come back when school started, but I shouldn’t expect much as a first-quarter freshman because The Lantern was for students already taking journalism courses.

Undeterred, or oblivious, I came back in September like an annoying little brother — think Beaver Cleaver. I was there to listen, learn and fish for assignments, no matter how insignificant. I idolized upperclassmen including Jennie, Christine, Dave Gollust, Bruce Vilanch, Jeff Tannenbaum and many more. They were journalistically competent, confident and surprisingly patient with my endless questions.

Those early days and nights in the newsroom helped shape my values, news judgment, work ethic and approach to professional relationships.

I was smart enough to be grateful in real time for the wonderful collection of characters and colleagues who inhabited my new world.

In spring quarter 1968, I bonded with fellow freshman, Jay Smith, who remains my best friend and teacher.

Working side by side in the newsroom, sitting in my apartment, riding in his little green Opel or sharing a cheap Sunday supper at the Blue Danube, every discussion with Jay became a journalism seminar.

We dissected every story: What are the ethics, the sources to call, the ques-

tions to ask, the compelling facts to get into the lede, the flow that will keep readers engaged? How do we illustrate it? What goes in the headline? Is it worth Page 1? We were learning our craft together and it was exhilarating.

I’m a lifelong two-fingered typist and those Lantern upright manual typewriters were heavy, slow and always needing new ribbons. I wrote thousands of words with Jay hovering over me, muttering about deadlines, always another damn deadline.

Every moment wasn’t about journalism. I encouraged Jay to ask out my high school friend Susan Shifres, whom he married. To their four kids, I’m Uncle Louie.

Every afternoon, that morning’s paper was critiqued by the faculty advisor at a meeting in the newsroom. This was a wonderful learning opportunity, if sometimes painful. The first time Dr. John Clarke mentioned one of my articles at a critique, he called it “sophomoric.” I thought that was good, since I was only a freshman, but then I looked it up. Not a compliment.

Bill Rogers, a thoughtful military and newspaper veteran, was the fac-

ulty advisor after Clarke. Bill and his wife had a young child, but they regularly made time to welcome Lantern staffers into their home, including after late nights at the print shop. Bill taught me a useful habit. He carried file cards in his shirt pocket to take note of every item that needed follow-up.

I didn’t need a file card to remind me that I really did need to bring my college days to a conclusion.

After a byline-packed internship at the Detroit Free Press, I was promised a full-time reporting job on the condition I get my degree. I spent my fifth year at OSU making up for lost time, hustling to get the required credits standing between me and my big city dream job. I aced a math class that was more about words than numbers and managed to pass a class in intensive German taught by an instructor who, as it turns out, had read and liked my Lantern columns. (I didn’t mention that I’d often skipped classes to write them.) And to current students I’d say: “Don’t try this at home!

Editor’s Note: Lou Heldman (B.A., Journalism 1972) was a Lantern reporter, editor, columnist, photographer and Page 1 designer. He worked 35 years for Knight Ridder newspapers in six cities as a journalist and publisher, then 12 years for Wichita State University in roles including Distinguished Senior Fellow in Media Management and Journalism.

1938

The university’s journalism degree becomes a Bachelor of Arts. The School of Journalism is placed under the jurisdiction of the College of Arts and Sciences. A horseshoe-shaped desk for copy editing, where the copy editing chief sits in the “slot” at the center and copy editors work along the rim, is installed in the newsroom.

1941-45

With U.S. entry into World War II, civilian men become scarce on campus and women make up, at one point, all but one of the enrolled journalism students.

In 1944, because the OSU stadium press box was off limits to women, Editor-in-chief

Jeanne Sprain successfully convinces the university to build a special booth for Sports Editor A. Loraine Clayton, the first female sports editor in The Lantern’s history. She erects a sign outside her small booth that reads, “No Males Allowed.”

Courses in public relations and broadcast journalism are now part of the curriculum and later become accredited programs in addition to the original “major,” news-editorial.

Dale Wright serves as news editor of The Lantern and a year later becomes the first African American to graduate from the School of Journalism. 1949

The Christie Mullins Murder Case, 50 years later

By Jim Yavorcik

It was not the kind of story you would expect a college newspaper to write about. But in September 1975, editors of The Lantern decided to investigate a murder . . . of a non-OSU student . . . that occurred off-campus . . . and one that police had already solved.

In August 1975, 14-year-old Christie Mullins was found beaten to death in a wooded area near Graceland Shopping Center, some five miles north of campus. An eyewitness helped police with a sketch of a man seen running from the crime scene. Within days, police arrested a man who looked like the sketch, a mentally challenged 25-yearold named Jack Carmen.

Within 14 days, Carmen confessed, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

However, folks who lived near the crime scene were skeptical about the police account of the case. Some in the community felt the accused man was railroaded through the justice system.

Although the case had little to do with OSU, Lantern editors thought it deserved a closer look and Faculty Adviser Paul Williams agreed.

I was assigned to take on this investigation

At the time, I was taking the Lantern reporting class and had hoped to cover the OSU football beat, but it was already taken. Instead, the editors told me I did not have to submit the usual 20 stories to pass the course.

I needed to write only one: The Christie Mullins murder case.

With no meaningful knowledge of the court system or investigative journalism, I first read a packet of news clips on the case. Then I went to the downtown housing shelter where I learned Carmen was seen picking up a paycheck on the day of the murder. After interviewing witnesses, I took a timed bus ride to the crime site, as Carmen had told police that is how he got to Graceland.

I determined that Carmen could not have made it to the murder site in time to commit the crime if the folks at the shelter were accurate in their accounts. In a day, I had established his alibi. Then I traversed the neighborhood near the crime scene and spoke multiple times with the victim’s fa-

A $4,000 gift from Scripps-Howard newspapers in honor of Ernie Pyle, the famous war correspondent, funds a journalism library in the 242 W. 18th Avenue building. It would later be expanded in the current Journalism Building in 1977 as the Milton Caniff Library, named for the Ohio State graduate and newspaper cartoonist known

ther, Norman Mullins. He questioned whether the police had the right man behind bars, and his doubts gave me another “hook” for the story.

There were many other leads to be followed, so Lantern City Editor Tom Loftus suggested adding another student reporter to the case. I told Loftus that I wanted Rick Kelly assigned, as I was impressed with his recent story on campus drug use.

Kelly and I interviewed the key eyewitness (Henry Newell) in his home. He bragged about his artistic ability and showed us his black velvet Jesus paintings. (The accused had long hair and a beard, also.) We had separate sources in law enforcement who gave us copies of the eyewitness Newell’s “rap sheet” and Newell admitted that he had a lengthy criminal record. Some in the neighborhood were already questioning whether this “eyewitness” had something to do with the killing.

We should have been frightened by this guy, but we were too naïve to be afraid.

Later, we obtained the confidential autopsy report and got an assistant coroner to acknowledge that the victim was not raped. This statement contradicted the police account and the crime Carmen pleaded guilty to. Columbus police detectives were very defensive when we confronted them.

The Lantern ran my story on Page One on Oct. 31, 1975, with Kelly’s detailed sidebar inside, setting forth the chronology. We were then asked to rewrite and expand the story for Columbus Monthly magazine. It was the cov-

1954

for the Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon comic strips. Today its collections are housed in the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum located in Sullivant Hall on campus, the world’s largest collection of materials related to cartoons and comics.

Following in the footsteps of Milton Caniff, beginning in the mid-1970s a se-

er story in January 1976 and the first hard-hitting investigative piece for the fledgling magazine.

We continued working the case even after our class assignments were over. Kelly interviewed Carmen in the Franklin County Jail and learned firsthand how this man could be led to say something that was not true. (Carmen admitted that he and Kelly golfed together.) I attended Carmen’s court hearings and received a crash course in criminal procedure. We wrote follow-up stories for The Lantern until we graduated in 1976.

With the help of our reporting, Carmen’ s new attorney convinced the judge to allow the defendant to withdraw his guilty plea. He eventually went to trial and was acquitted by a jury — even with the police confession admitted as evidence.

MULLINS continues on Page 12

ries of Lantern editorial and other cartoonists would establish a mini dynasty of award-winning cartoonists who also created their own comic strips, including Brian Basset, Scott Willis, Brian Campbell, John “Derf” Backderf, Jim Kammerud, Nick Anderson, Jeff Smith and Steve Spencer.

The Lantern in the Watergate Era

Iarrived at The Lantern in late 1974, the mother of two, and a new faculty wife. I was in quest of an M.A. in Journalism and remember so clearly my tentative early visits to the newsroom to drop off my copy to City Editor Tom Loftus. Daycare was a scarce commodity, so a nine-month-old babe was glued to my hip.

The Lantern newsroom – with all its free-wheeling fun and an incubator for 50-plus year friendships — was critical to the journalist I became. Taught by some of the best in the business — experts who took time to inspire us to do good work, I felt — how could we fail?

We were lucky, indeed, to be led into the computer age by Dr. John Clarke, of the Providence Journal. Stuart Loory of the Chicago SunTimes taught me the importance of cultural and linguistic literacy, especially if one aspired to be a foreign correspondent. And Lantern Adviser Paul Williams, a Pulitzer prize-winning investigative reporter, instilled in us that old-school, boots-on-the ground reporting always beats sitting in an office. He was also sure that a student newspaper such as The Lantern could one day win a Pulitzer.

My first assignment was the campus police beat, with a stunner of a case, after an 80-year-old woman’s car went airborne as she hit a

divider at a new intersection nearby, killing two OSU students. On this, and many other stories, Lantern reporters ran circles around Columbus’s two dailies.

The scariest and deepest pieces I wrote were the series Rena Wish Cohen and I did as we uncovered a heinous local slum lord, Paul Rine. We visited dozens of un-maintained and over-priced rental houses Rine owned, many just a stone’s throw from OSU’s south side. We painstakingly deposed all tenants, photographed leaking roofs and ceilings, toilets spewing raw sewage, basement rat infestations and other unlivable conditions. Most renters were low-income whites, many with pre-school children crawling near

potentially lethal exposed wires.

We scrutinized five years of previous housing code violations and showed how Rine had evaded responsibility except for a rare $250 fine. Mr. Rine got many renters we’d interviewed to recant their sworn statements by threatening them with eviction.

In the process of our months’-long investigation, we were followed, our car was rear-ended in the parking garage across from the J-School, and Mr. Rine even drove his truck up to the door of the Kenny Road printing facility the night the story was inked, in a desperate attempt to stop the presses.

Most terrifying to me was the phone call I got late one afternoon at our rental on Westwood Road. A menacing voice told me: “I know where you live,

and how your daughter walks home from the High Street bus, so . . . ” Williams died suddenly one noon when he went home for lunch with his wife, as he regularly did. But he and others had trained me so well that in my first job after OSU, as editor of the Dublin Forum, I could lay out columns, write headlines, shoot decent pictures, use a computer and investigate local dump sites in the Olentangy and Scioto rivers with no problem.

In 1978, when my husband and I moved to Washington, D.C., we had an informal Lantern reunion. Cherie Fichter sent me her regrets from Southeast Asia, along with an envelope containing several “Thai sticks.” Clueless, I asked around. My present was illegal Schedule I drugs. Not sure how they slipped through the postal service. And NO, I did not try them. When things got tough much later, as I joined The Washington Post, I always remembered what Williams told me one day as he handed me his extensive scribbled comments (in red) on that day’s Lantern. “You’ll be a good journalist; you have a low threshold for indignation.”

Editor’s Note: Joan McQueeney Mitric (M.A. Journalism, 1977), was a Lantern columnist and assistant city editor. She went on to specialize in covering national health and international issues, writing op-ed pieces for The Post and The New York Times. She also taught journalism for IREX, UNICEF and other independent media groups all over the Balkans.

1958

The Lantern resumes summer publication.

1960

By the beginning of the new decade, The Lantern is distributed free on campus for the first time. Circulation is 15,000. Seven editors are listed on the editorial page: Editor, managing editor, city editor, makeup editor (no, not the Hollywood

type), sports editor, photo editor and wire editor. They are selected by a Publications Committee and receive a modest stipend, though given the long hours they put in, the effective hourly wage is small indeed.

1962

Senior Lantern writer Phil Ochs, bitter at having been passed over for editor-in-chief, leaves for Greenwich Village and becomes a founder of the folk and protest movement of the 1960s.

Remembering ‘Mad Martha’ Brian

By Leon M. Rubin

OnMarch 25,1982, Martha Brian — an associate professor of journalism at Ohio State known affectionately as “Mad Martha” — died of cancer. Her death devastated her former students, colleagues and friends. Shortly afterward, a group gathered in the Journalism Building to pay tribute. I was honored to be one of the speakers that day. A few excerpts from my remarks and recollections follow:

I’d have to start with the fast-breaking story in Journalism 202 — the one that involves a plane crash, with new

information coming in about injuries, famous people aboard and finally, the dramatic announcement that there are no survivors. All this is taking place under the premise that it’s about five minutes from deadline and the editor is frothing at the mouth to put the paper to bed.

I can still picture Marty racing around the room, grabbing sheets of paper out of our typewriters as we struggled to get even a few lines on each page. “Copy, copy, I want copy!” she’d scream, and you’d hear the ratchet on another carriage spin like the cylinder on a six-shooter. Needless to say, accuracy went out the window. My total score for the exercise was minus 132 points — and I foolishly thought I kept up pretty well.

I remember Michele Orzano and I camping out in Mary Umberger’s Chicago apartment so we could be in Joliet at 6 a.m. to go whistle-stopping across Illinois with Gerald Ford. Pleading with Marty to let me change the spelling of Naghten Street in a Journalism 641 story before she graded it so I wouldn’t get a zero on a 15-page paper. The great time we had planning — under Marty’s strict orders — the “surprise” party for her 50th birthday.

I’m sure I’m just one of hundreds of students Marty influenced. Some of them were influenced to get out of journalism and may have been

1966

OSU President Novice Fawcett is quoted as saying that “students have complained to me on different occasions that they disagreed with Lantern editorials and did not want money from their fees to support the newspaper.” The sentiment reflects the tenuous relationship between

better for it. Many others were inspired to do great things while they were in J-School, and they’re still doing them today.

I wrote a letter to Marty after I went to work for the Chronicle-Telegram in Elyria, telling her how much the real world of journalism was like she said it would be and how thankful I was that she had helped me prepare for it. I know that pleased her. She told me she read the letter to her class so they could hear first-hand that what she was trying to get across to them was important.

If Marty left a legacy, I think it’s the inspiration she gave all of us to try to be like her in the work we do — to be a stickler for detail, to ask the tough questions, to know how to get a difficult job done under pressure.

Anywhere in the world where there’s a former student of Martha Brian, we’ll keep teaching her lessons. Through us, Marty Brian will never be forgotten. And her influence will always be felt in our profession.

After Marty’s death, a group of her former students launched a campaign to establish an endowed fund in her memory — the Martha Brian Fellowship in Journalism. Initially, more than $36,000 was raised and scholarships began to be awarded to graduate students in 1987. Now called the

Martha Brian Fund, the endowment has grown to about $242,000. It supports graduate student travel to attend annual conferences in communication and journalism to network and present papers. Just over $44,000 has been awarded in the past three years. Almost $316,000 has been distributed since 1990.

Editor’s Note: Leon M. Rubin, a 1977 graduate of the School of Journalism, has been the president and owner of his own communications company for 34 years in addition to having served as Director of Communications for the Office Depot Foundation, as a writer and editor for the Cultural Council of Palm Beach County, as Director, Marketing Development/Communications at Ohio State, and as a community volunteer. Today he is a freelance writer in Dahlonega, Georgia.

the paper and the student body that has existed for more than a century. N.B.: The Lantern was not then, and is not now, supported by university funding or student fees. As an independent paper, it relies on advertising income and increasingly, today, on donor money.

1967

John J. Clarke, a member of a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter team for the Providence Journal, joins the School of Journalism as an associate professor and Lantern faculty adviser. Clarke later pioneers the use of computers in journalism instruction in the 1970s and remains a faculty member until 1986.

By Jeff Trimble

If sex sells, the 1977 Lantern should have been rolling in cash.

• Sample headlines, from just one month (March):

• “Topless titillation tabooed for Florida spring frolics”

• “Skin flick creator reveals naked truth”

• “Pornography stirs rallies” (Double entendre, anyone?)

• “Pimples and peeping Tom pose problems” (From a “Letter to Dr. Turner” column, in which a student asks for advice because she’s considering exposing herself to a peeping Tom in her campus neighborhood. Bad idea, opined the doctor.)

• “Bette Davis claims ‘daring’ nude scene” (a wire story)

Sex, lies, and VDTs

And this, atop an arts column by yours truly: “Porn draws high praise.” The Page 1 teaser: “Arts Columnist Jeff Trimble thinks it’s about time someone said a few words about what’s good about Hustler magazine and similar publications. For his critique of the prince of porn, turn to Page 11.”

I opened with high-minded praise for First Amendment free speech protections, then dove in with this: “When did you last hear anyone in the media say, ‘Yeah, I think porn is a real turnon, and we should keep it around?’ I feel it is up to me to defend the interest of those Hustler devotees and the millions of others who enjoy the endless stream of pornography in its many forms.”

I went on to do so, in a lurid review of that month’s Hustler issue that I confidently intended to be a humorous, over-the-top satirical take-down of the magazine’s unabashed, gross raunchiness, much of it involving perverted debasement of women.

It didn’t work. To more than a fair share of readers (including Lantern colleagues, many of whom were ardent feminists) the article came off as a misogynistic defense of male chauvinism in the extreme.

Lesson learned: humor is hard. Don’t try to write satire unless you know what you are doing.

Was sex top of mind in the Lantern newsroom on those chilly March afternoons? After all, the topic was (and remains, I assume) of more than passing interest to college undergrads.

But there’s more to this story. As

The Lantern’s printing facilities are relocated from the first floor of the building at 242 W. 18th to a plant on Kenny Road. This is in anticipation of the switch later in the year from a “hot type” press to a “cold type” process that prints photographed content onto photo paper. The photo paper is cut into strips and glued onto a layout board for the next day’s pa-

aspiring journalists, we were exploring the hottest issues of the post-Vietnam era, a time of unprecedented frankness about the good, bad, and ugly of American society. Women were flexing their muscles — literally as well as figuratively — as never before, with Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Shirley Chisholm among leaders pushing for equal rights and challenging gender inequality. The Equal Rights Amendment was under fiercely contested consideration for ratification by state legislatures. (To remind: the amendment fell short of ratification by three states, and Ohio was among those that did not ratify it).

We waded right in. In that same month the inimitable Marilyn Geewax, perhaps our most ardent feminist, wrote a dead serious, poignant column about the scourge of child pornography. My cringe-inducing arts column was meant to explore the challenges of balancing free speech rights against legal and other determined attempts to stem the rank exploitation of women. Our efforts were sincere and well-intentioned. Sometimes we succeeded. Sometimes we came up short.

That’s my second Lantern lesson learned:

don’t shy away from the big issues just because they are difficult. Jump in. Push the envelope. If you get it wrong, admit it and try again.

That’s the brand of journalism we learned at The Lantern and that guided our careers in media through decades of our country’s history: the good, the bad, and the ugly. And yes, the sexy too.

Editor’s Note: Jeff Trimble (B.A. Journalism, 1978; M.A. Journalism, 1982) has been an international journalist, editor, and media manager for more than 40 years, including as Moscow Bureau Chief and Foreign Editor for U.S. News & World Report and as Director of Broadcasting and Acting President of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. He chairs the board of Eurasianet and is an affiliated lecturer in OSU’s School of Communication.

1968

per, a process known as “paste up.”

Members of the Black Student Union, protesting second-class treatment of African Americans by the university, take over the Administration Building for 10 hours and are targeted by university officials for prosecution on trespassing and kidnapping charges. The Lantern, in an editorial titled “It’s Time for Action not

Overreaction,” opines that although the disruptive activities “cannot be tolerated,” the university’s “first priority should be to remedy the iniquities which induced such behavior.”

Left: “Paste up” at the Kenny Road print shop.

Tenacity, persistence, brevity and clarity

By Renee Miller

Tenacity, persistence, brevity and clarity. Those are the four skills I carried with me from my time at The Lantern. They’ve served me well, from my early days as a newspaper journalist to my role today as executive creative director and founder of The Miller Group, a woman-owned creative branding boutique based in Los Angeles.

I came to Ohio State as a transfer student from Bowling Green State University my sophomore year, determined to make my mark. One of the first actions I took was to make an appointment with Dr. John J. Clarke, professor of journalism at the time. I told him — without hesitation — that I intended to become a reporter and editor for The Lantern. I was fortunate enough to get published that same year, serve as an op-ed columnist my junior year and ultimately became arts editor senior year.

Working on The Lantern was

like being thrown into the deep end of journalism. We were expected to do the work of professionals, and credibility wasn’t optional— it was everything. Listening mattered just as much as writing. And often, what wasn’t said by a source was more revealing than what was. That’s where interpretation came in — learning to read between the lines, to uncover the real story, and to tell it well.

Of course, being a student journalist meant pushing through a lot of closed doors and dead ends. It was tenacity and persistence — as much as solid story ideas — that helped me succeed. Early on my father instilled in

1970

The Lantern suspends publication for nearly two weeks in May due to the shutdown of the entire campus on account of student protests against the Vietnam War and the May 4 killings at Kent State. Tanks and military soldiers are present on the Oval during this period.

me that persistence, even against long odds, could be the difference between a breakthrough and a missed opportunity.

At Ohio State, I learned the power of brevity and clarity — how to strip away the fluff and get to the heart of a story. Those principles stayed with me as I transitioned from journalism to advertising. In branding, as in reporting, every word matters.

To this day, I credit my time at The Lantern for shaping not just my writing, but my worldview. Journalism taught me to question, to dig, to clarify — and ultimately, to connect. Whether I’m helping a brand find its voice

or guiding a team through a creative brief, those same skills remain at the core of my work.

Editor’s Note: Renee Miller, a 1979 graduate of the School of Journalism, was a reporter for The Arizona Republic before founding her own public relations agency and later, in 1990, The Miller Group.

MULLINS continued from Page 8

My Lantern piece won a Hearst award and our Columbus Monthly story was awarded best student magazine piece nationally by the Society of Professional Journalists. Kelly and I have remained life-long friends and later worked at The Toledo Blade together as reporters. I went on to work as an assistant county prosecutor.

As a trial lawyer in private practice, I still represent victims. But it was at The Lantern that I first learned how to interview witnesses and family members of a deceased victim.

Our professor Paul Williams critiqued the 1975 stories in a sidebar to the Columbus Monthly article about The Lantern (“A Daily Laboratory Newspaper”). He said, “It was almost too much for our reporters, but they gained a lot from it.”

We sure did. That “one story” in The Lantern was a life-changing experience for both of us.

Editor’s Note: Jim Yavorcik is co-owner of Cubbon & Associates in Toledo. Rick Kelly is a semi-retired consultant for Triad Strategies, a communications firm in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

1972

Lantern circulation reaches 40,000, an alltime high, making it one of the two or three most widely circulated college newspapers in the nation.

My fondest Lantern memories

I’mBy Chris Mines

so glad my early love of writing led me to study journalism and work on The Lantern, the best choices I ever made. I was so shy in high school, I don’t know what possessed me to go into a field where I had to talk to people for a living! But learning that most people were happy to share their expertise and opinions with a genuinely curious reporter made interviewing so much easier. That exposure brought me out of my shell and changed the direction of my life.

I had so many great experiences on The Lantern, I hardly know where to start. As the Spring 1980 sports edi-

tor, I got to sit in the press box for the Spring Game, the intrasquad football game and ride the elevator with Coach Earle Bruce. The icing on the cake was the defensive MVP of that game being an alum from my own high school. I was so proud!

Also that quarter, the Cincinnati Reds invited college sports editors from around the region to a game. At the private press conference and handshake photo op, the players said, “Ohio State! All right!” when they saw my name tag. Of 30 schools represented there, ours was the only one they commented on.

While covering a trip by the Fellowship of Christian Athletes to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, I met some of the biggest sports names on campus, including the later-infamous QB Art Schlichter. I got to interview Olympic gymnasts Bart Conner and Peter Vidmar at a national meet at St. John Arena, and the coach of China’s diving team, which was competing internationally for the very first time.

Inside the newsroom, life was no less memorable. We got permission to repaint the room and had Chinese yoyo fights across the

desks. After late night shifts at the off-site print shop left us slap happy, News Editor Sue Maney — aka Sue Maniac — proved far more dangerous behind the handle of a shopping cart at Big Bear grocery store than behind the wheel of a car.

I also covered the hockey team one quarter and still keep in touch with some players on Facebook — just a few of my Lantern connections that have lasted 45-plus years.

be so condescending.

I was wire editor one quarter, selecting AP and UPI stories off the teletypes to run in the paper. Other quarters I supervised copy editors from the “slot” of the horseshoe table that we worked from and formatted stories for typesetting when VDT word processors in the newsroom were still new.

There weren’t many bad experiences, but one still galls me: when then-basketball coach Eldon Miller sneeringly called me “little girl.” I admit that, not knowing as much about basketball as other sports, I asked a question he didn’t like. But that was no excuse for someone in his position to

With five-day-a-week printing and huge circulation, the university’s prestige, the renowned sports programs, and myriad other opportunities, OSU and The Lantern offered an experience like no other.

Editor’s Note: Chris Mines graduated in 1981 and has worked in public relations at a community college, as a sports editor on a weekly newspaper, and as an editor of maintenance manuals for GE jet aircraft engines. Since 2013 she has been the marketing copy editor at Highlights for Children, the iconic kids’ magazine, currently working remotely from Boulder, Colorado.

1974

After three years of gutting and renovation of the original Journalism Building, during which The Lantern operated in Bevis Hall on West Campus, the “new” (and current) Journalism Building opens at the same location at 242 W. 18th Avenue. The reconfigured newsroom is moved to Room 271 in roughly the same location as the prior newsroom (Room 216).

The remodeling adds 55,000 square feet to the building, allowing for a larger Lantern newsroom flanked by smaller rooms for the paper’s faculty adviser, editorial board meetings, wire service machines, photo lab, and clippings library, known as “the morgue.” Copy is generated on electric typewriters.

1975

Two Lantern reporters, Jim Yavorcik and Rick Kelly, take up the investigation of the brutal murder of 14-year-old Christie Lynn Mullins in a wooded area in Clintonville north of campus after other newspapers in the city had moved

on from the story. Yavorcik and Kelly demonstrate that the suspect arrested for the crime, a developmentally disabled man who pleaded guilty, could not have committed it.Their reporting leads to a new trial and acquittal of the accused man.

Those Damn Cartoons!

By Derf Backderf

My work for The Lantern almost got me tarred and feathered on the Oval.

In addition to serving as a reporter, copy editor and photographer, I was the political cartoonist from 1981 to 1983, smack in the middle of the paper’s remarkable run of cartoonists who went on to significant professional success. Newspaper comics was my chosen profession. Journalism studies was a means to that end.

You all no doubt remember the disgraced Buckeye football star Art Schlichter. An All-American quarterback, and the face of Buckeye football for his four triumphant years. In April 1983, after a terrible rookie year with the Baltimore Colts, he was nailed in a gambling sting. Eventually, he was thrown out of the NFL. It was THE sports scandal of the year and a shocking fall from grace. In what I thought was an obvious attempt to escape charges, he turned in his bookies to the FBI.

This prompted me to draw a cartoon where Schlichter met a Sopranos-like end for being a stoolie. Tasteless? Certainly. Inappropriate? For a traditional paper like The Lantern, definitely. I turned in the cartoon, naively, with no qualms. None of the editors voiced an objection. Off it went to press.

Shit, meet fan.

The next day In my morning history class, I noticed some students were glaring at me. Strange, I thought.

The next class, more glares. Someone yelled at me as I walked across the Oval. I have no idea how he knew who I was. I jogged the rest of the way to the Journalism Building, a nervous lump growing in my stomach.

I walked into the newsroom . . . and was showered with boos and wadded up balls of paper! Turns out the phones had been ringing off the hook since dawn with complaints from outraged Buckeye fans! It got worse from there. Columbus TV sportscasters waved copies of my cartoon and ranted their disapproval. Even the national sports media weighed in. I unplugged the phone in my apartment to silence the incessant threatening calls. Out of caution, I hid out at my girlfriend’s house for a few days. The OSU athletic director called J-School Director Walter Bunge and demanded that I be sacked from The Lantern. Several of the journalism faculty wanted me gone, too, I’m sorry to say. Luckily, I had faculty allies like Dr. John Clarke in my corner. “A cartoonist is supposed to piss people off!” he growled to me, with a chuckle. “That’s the job!” God, I worshipped that man. I was mere months from graduation, so the decision was made to leave me be, since I’d soon be out of their hair.

I dare say it’s the most controversial cartoon in Lantern history. Unfortunately, it’s not a good cartoon. At age 22, I didn’t understand that addiction is not a moral failing, but a destructive mental illness. Society as a whole hadn’t yet accepted that in 1983, when we were in the shadow of

the cocaine-fueled Studio 54 era. Drug addiction was barely acknowledged, let alone something like gambling. It’s a cartoon “of its time,” and not one I would have penned a year or two later, after I acquired just a little more life experience.

Strange as it sounds, until this cartoon and its aftermath I never thought much about the massive degree of chutzpah it took to be a Lantern cartoonist. I walked in off the street, a 20-year-old rube from small-town Ohio, and arrogantly displayed my amateur cartoons in front of 35,000 readers without a moment’s hesitation. I don’t know where that fearlessness, or perhaps recklessness, came from. That was the gift of The Lantern. It was where I was first published. It’s where I first found my voice. What the Schlichter Affair taught me: say what you mean, craft it carefully, and stand your ground. It was a lesson, while taking heavy fire from all directions, that

served me very well later as a professional.

As for Schlichter, he became a serial criminal and left a long trail of victims he swindled out of millions to feed his addiction. He spent most of the next decades in and out of prison. I doubt any of the readers who demanded my head in 1983 would offer a similar defense of him now. As Ben Bradlee said in All the President’s Men: “I screwed up … but I wasn’t wrong.”

Editor’s Note: John “Derf” Backderf graduated in 1983. His comic strip appeared in The Village Voice and 150 other similar alternative weekly papers for 24 years. He was the recipient of a Robert F. Kennedy Award for political satire. He is the author of nine graphic novels, including the international bestseller, My Friend Dahmer, which was made into a feature film in 2016.

1975, cont’d

Another Lantern reporter from the same era, John Oller, performs an investigation and writes a book about the cold case almost 40 years later which leads to the police reopening the case and naming the true killer.

1976

After petulant behavior by Woody Hayes following OSU’s Rose Bowl upset loss to UCLA, the latest in a series of similar incidents, The Lantern calls for him to resign, provoking a negative response from the campus community.

1977

Lantern newsroom, 1977, with IBM Selectric typewriters

From clacking keys to flickering screens: How The Lantern bridged the typewriter and digital eras

ery reporter aspired to get their hands on.

Call us the last of the typewriter era. A generation of journalism students who clacked out their high school essays on the old technology and emerged from college fully immersed in a computer-driven world.

When I arrived at Ohio State in the fall of 1981, the typewriter was still a familiar tool to most students — as it had been, albeit in slightly more primitive form, to our parents and grandparents before us. So it wasn’t at all unusual to find typewriters populating the desks of the Lantern newsroom for our use. I can remember typing story and photo ideas for Journalism 201 class on triplicate carbon paper provided by our professors – one copy to keep, one copy for the teacher and one reserved, if our idea was accepted, for the Lantern editor who would be handling the story.

Nearby, though, at the newspaper’s editing desks, video display terminals were the emerging technology that ev-

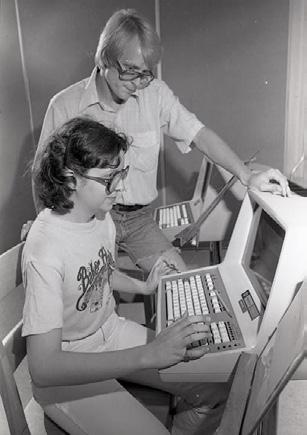

The first VDTs had appeared at The Lantern on a limited basis in 1974, thanks to a gift of the Gannett Foundation that made us the first college paper in the nation to acquire them. But, for many years, only editors and copyeditors got to use these Jetsons-esque word processing machines, which consisted of a video screen housed inside a bulbous plastic casing that sat on top of a one-legged, four-footed rolling stand. It’s impossible to describe how cool and advanced these bulky miracle machines seemed to us.

“I remember them telling us at the time that The Lantern was ahead of many commercial newsrooms in getting VDTs,” my classmate Mike Rutledge recalls. “I think that was the truth.”

Rutledge remembers arriving at his first post-college internship, for the Akron Beacon Journal’s Columbus bureau, only to be relegated back to a portable Tandy computer, which was capable of displaying only three lines of text at a time. The paper’s limited supply of VDTs was reserved for the higher-ranking reporters, he said.

In the early days of the technology, the job of a Lantern editor was to enter stories typewritten by student reporters into the terminals. Early VDTs produced punched tape that could be fed into typesetting machines in the newspaper’s composing room and printed on photo paper as columns of text.

1980

Video display terminals (“VDTs”), a type of word processor, are in use at The Lantern. They were introduced on a limited basis in 1974, when The Lantern became the first college paper to acquire them.

These columns were pasted in pre-determined layouts onto page blanks then shot as photo negatives that, in turn, were used to make the printing plates.

In 1981, the Lantern composing room had just been moved from the printing plant on Kenny Road to a room adjacent to the newsroom on the second floor at 242 West 18th Avenue. So many of my contemporaries on the newspaper staff got to have direct roles in the layout and paste-up process.

Catherine Candisky, another of my classmates, was one of them. She said her job at the time was to type advertising copy into the system that, like text stories, would be printed onto photo paper in the agreed upon dimensions for placement in The Lantern’s pages.

She recalls the era as a thrilling, but dicey, time for both journalism students and professionals as they sought to make the most of the steady stream of computer advancements.

“The technology was all new, so we weren’t that gifted at it yet,” she said. “And, because it was new, it was more susceptible to hiccups.”

By the time I landed my first post-college job at the Galion Inquirer in 1985, each reporter’s desk was equipped with a VDT. There, one of our jobs was to check the page proofs in the backshop for typos. I can remember dashing back and forth to a machine that spit out column-width paper coated in wax filled with the words or paragraphs we needed to place over any

mistakes we’d spotted.

As VDT technology advanced, later generations of terminals streamlined the production process by dispensing with punched tape and sending coded stories directly to the typesetter.

The Lantern acquired enough new video display terminals over time so that reporters could join editors and copyeditors in using them to write and edit stories. The VDT had come and gone as a newsroom mainstay by the mid-1990s, replaced by early versions of the Macintosh personal computer.

Looking back on helping to usher out the typewriter era comes with a bit of nostalgia. I remember Robert Redford once saying that the makers of “All The President’s Men” put their hammering keys in the aural foreground of one of the greatest journalism movies of all time, to convey the way they were being used “as weapons.” Still, being forced to adapt to a new technology in college turned out to be perfect practice for the lifetime of new technologies that has been laid before me over the past 40 years. The VDT may have been the first, but I doubt there will ever be a last.

Editor’s Note: Julie Carr Smyth (B.A., Journalism, 1985; M.A., Journalism, 1991) covers government and politics from Columbus for The Associated Press. She was part of the AP team honored as a finalist for the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in breaking news.

1981

The composing room relocates from the printing plant on Kenny Road to a room adjacent to The Lantern. The layout and paste-up process were now being done largely by students in house. Printing was still done at the facility on Kenny Road. By the end of the decade type-

writers were no longer found in the newsroom. VDTs were used at The Lantern into the mid1990s but they, too, eventually became obsolete. Today, both VDTs and the traditional pasteup practice have been replaced by personal computers and digital desktop layout software.

Lantern duo’s 1987 USG win still a campus legend

Looking back, it was a pretty wild idea.

Could two guys from The Lantern run for and take over the Undergraduate Student Government? SHOULD two guys from The Lantern embark on such a venture?

Scot Zellman and I did. We won in 1987 in a squeaker of an election, besting the second-place team by just 36 votes.

You may be wondering WHY we wanted to run for USG. Good question.

Like most Lantern staffers, we’d taken our shots at the student government. This was a natural thing. They had some power and we were the watchdogs. It’s the same thing with the news media and government in the real world.

But I admit we did it – at least I did it – because it sounded like a fun thing to try. And the job paid pretty good money.

Zellman was a very well-known Lantern cartoonist at the time. His rendering of Cletus Buckeye in his comic strip “Potshots” was legendary. Cletus, distinctive for his spikey buckeye-shell-head that never fell off, was the forgotten brother of Brutus. While Brutus was wholesome, Cletus was devilish, smarmy and always had a cigarette dangling from his lips.

I had been Lantern editor, held other staff positions and was a longtime columnist. Zellman asked me to run with him and I jumped at the chance. With his artistic skills, he created our campaign literature, with recognizable Cletus on the front, and I’m sure that’s what put us over the top.

I wouldn’t say we got a lot of things done at USG, but we did have some success, including working on improvements to student safety on campus. Mainly, I just wanted to root out “corruption,” as I saw it back then. As I view it today,

1982

Journalism professor Martha (“Marty”) Brian, known as “Mad Martha,” and perhaps the most beloved (and feared) teacher in the School of Journalism’s history, dies of cancer at age 51. She had been a faculty member since 1967 practicing her military style of “tough love.”

we were all just a bunch of college kids learning about life, how systems work and how systems can be played. I met some great people along the way. Most of us had good intentions.

Running for and winning the vice presidency of USG helped me do two things: extend my undergrad stay an extra year (for a total of six years? Oh, my), and learn that I don’t think I ever really want to be in politics. I’d rather watchdog politics, like we did at The Lantern. The year went by very quickly. USG was memorable. But it wasn’t The Lantern. Those years in the newsroom, where I met friends I still keep in touch with today, were tremendously impactful for me and helped me know that I was on the right career path.

I’m grateful for my time at USG, and prouder of my time at The Lantern. Long before Zellman and I became candidates, in one of the greatest stings that may ever have been pulled off by a college newspaper, our Lantern staff busted members of a fraternity stealing thousands of our papers just after they’d been printed and distributed to racks all over campus. We staged photographers at several locations in the early morning, and caught

the thieves red-handed. The motivation for their crime? The Lantern that very morning had printed an endorsement for the upcoming USG election and the team that won the paper’s support was not from that fraternity. Someone on our staff had a hunch this would happen. That’s good watchdogging!

Editor’s Note: Jim Schaefer was Lantern editor in Fall 1986 after holding several other editing positions. Today he is an executive editor at the Detroit Free Press, where he and his reporting partner M.L. Elrick won a Pulitzer Prize in 2009 for their reporting on the mayor of Detroit.

1991

For nearly the entire month of October, The Lantern masthead includes a banner headline that reads, “Publication Under Protest.” Editor-in-chief Debra Baker and 15 members of her staff sign a front-page editorial on Oct. 2 objecting to the proposed adoption by faculty and administration of a policy giving the school’s director and Lan-

tern adviser the right to review in advance and prevent publication of any material they or legal counsel deem potentially libelous.

When faculty vote formally to approve the policy on Oct. 27, Baker and two of her editors resign the next day and seven others are fired for refusing to work.

Lifelong legal lessons learned at The Lantern

By Maria Averion

Autumn Quarter of 1989, when I was editor-in-chief of The Lantern, is seared in my memory. I had a front-row seat to Lantern history.

For years afterward, every time I came back home to Columbus for a visit, my parents or siblings would make the same comments as we passed the northeast corner of Henderson Road and Riverside Drive on the way to my parents’ nearby condo. There it was: Albert DeSantis’ mansion with a moat.

My older brother, also an OSU alum, commented that he always brags to his friends that “My sister was sued by Al DeSantis” or “Al DeSantis sued my sister for $5 Million.”

His name didn’t mean anything outside the state or OSU circles, but Al DeSantis, a local real estate man, was well known around campus. And he profoundly impacted both my personal

life and my journalism career for years to come.

One night I entered the newsroom and began making the rounds in preparation for that night’s printing. When I walked into the paste-up room, one of the layout guys, Charlie, motioned for me to come over to the pages he was working on. He pointed out a cartoon to me, one of the regular strips we ran. This one was by Terence Concannon. In keeping with his normal style, it was a stick figure (of Al DeSantis) pointing to two homeless students living in a cardboard box and yelling, “You people are pigs! Clean it up by tomorrow or I’ll use it as a toy box.”

I immediately pulled the strip off the page and took it to consult with several people, including Lantern adviser Bill Green and media law professor Hugh Donahue. Initially, Donahue laughed and said the cartoon was funny. Then he advised that if we wanted to publish it, we shouldn’t run it on the cartoon page where Concannon’s strip

The Lantern is one of several U.S. student newspapers to publish a paid advertisement by Bradley Smith that disputed that the Holocaust took place. Although the campus reaction was almost univer-

usually ran, but instead on the Opinion Page where it was protected by the First Amendment’s “fair comment” privilege to express opinions about public figures. I decided to hold it for the day to mull it over and talk further to the adviser as well as the cartoonist.

The next day, after input from everyone and their mother, I decided to run the cartoon on the Opinion Page as Professor Donahue had suggested. We ran it and braced for the reaction. It was swift.

Sometime in the next few days, three individuals: myself as the editor-in-chief, the cartoonist, and adviser Green were sued by Al DeSantis for libel (oddly, The Lantern itself was not sued). The papers served on us sought damages of $5 million.

It was mind-blowing at the time, but luckily, we had prepared. We learned that because Ohio State was a state school, the Ohio attorney general was our lawyer. The director of the School of Journalism, Walter Bunge, supported us at the time, as did many of the professors.

1992

sally negative, including a 250-student protest at the Journalism Building, the editor-in-chief declined to apologize for running the ad, citing its news value.

The Lantern had published Smith’s ad along with an

editorial deploring it as “a repulsively coherent piece of propaganda” and “racist,” but arguing that “no matter how repugnant, we must allow Bradley Smith to have his say.”

We met with Bunge and the attorney general and discussed what could happen. It turned out that DeSantis’s lawyer filed the case in the wrong court — the criminal rather than civil court. For whatever reason, DeSantis decided not to refile, essentially dropping the case. We assumed he’d gotten legal advice from other lawyers that his case was without merit.

I never had to defend myself from another libel lawsuit in my career. But the case was instructive, because as a copyeditor I always knew the law and kept it in mind when editing others’ stories.

As a reminder and memento, I kept the papers from when I was sued by Al DeSantis for $5 million. And I still have them to this day.

Editor’s Note: Maria Averion graduated with a B.A. in Journalism in 1990. For more than 20 years she was a graphic designer, page designer, photo editor and web designer in the newspaper business for papers including The Washington Post and The Columbus Dispatch. Today she does freelance web design in Columbus.

1993