T

he first time Tim May ever saw Ohio State and Michigan play, he had to squint at a black-and-white television in Demopolis, Alabama.

It was 1961, and he was a football-obsessed kid who watched whatever his antenna could pull up. He didn’t know it then, but those flashes of scarlet and gray would shape his career and, ultimately, his life.

Now, as he prepares to cover his 45th Ohio State-Michigan game, May has become the rivalry’s living repository of information, an encyclopedia in a baseball cap, armed with nearly half a century of memories, anecdotes and context that no media guide can match.

“I am a huge college football fan, so I understood from an early age the ramifications of this game,” May said.

May moved to Ohio from Texas in 1976 and began covering the Buckeyes full-time for the Columbus Dispatch in 1984. That season was his first in-person Ohio State-Michigan game, where he was sitting in section oneAA in Ohio Stadium behind the track that then circled the field.

Even though he could barely see the on-field action of the game—a 21-6 Ohio State win—what he wrote was the first installment of arguably the most comprehensive firsthand accounts of The Game.

May’s understanding of the rivalry was shaped through the dominant Ohio State teams of the late 1960s and the iconic 10 Year War that followed, where coaches Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler traded gridiron blows.

“It was like watching Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Robots,” May said. “Both of them, for the most part, were scared to death to let it all hang out in the game, because they knew one big mistake could cost you huge.”

May rattles off memories like someone flipping through an internal highlight reel.

He remembers:

The 1987 upset in Ann Arbor six days after coach Earl Bruce was fired, when Ohio State players wore “Earl” and “Bruce” headbands.

The 1992 tie with Kirk Herbstreit at quarterback.

In 1996, Michigan stunned Ohio State when cornerback Shawn Springs slipped on a slant route by Tai Streets, freeing Streets for the game’s only touchdown in a 13-9 upset.

While May can seemingly recall every game year by year, he also knows The Game’s intensity extends well beyond the field.

His first example of that came near the Big House tunnel after the ‘96 game, after head coach John Cooper’s seventh career loss to the Wolverines.

“He was screaming at Cooper like he just shot his family,” May recalled. “It was unmerciful. But people take this stuff personally.”

Moments like that taught May that covering The Game meant stepping into something larger than football. For fans, the hate is generational; for coaches, the stakes are existential.

For players, the game is defining.

The sport has changed much in his four decades on the beat, with NIL, conference realignment and more.

The intensity of The Game remains a constant.

“You can’t throw all the traditions away, because that’s what college football is about,” May said.

May retired from the Columbus Dispatch in 2019 and now covers Buckeye football without “writing 10 million stories,” like he used to. He is the host of the Tim May Show and records daily video stand-ups for Fan Stream Sports.

Now 71, May has contemplated retiring multiple times, but his passion for covering the Buckeyes keeps pulling him back in year after year.

This year, May will be in the Big House press box on Nov. 29, looking out over the same field that has given him a lifetime of stories.

When asked whether the shine of The Game ever fades after so many years around it, May didn’t hesitate.

“No,” he said. “The reason you cover Ohio State football and this game is because people give a damn.”

JACK MACEY Sports Project Reporter

This year’s showdown between Ohio State and Michigan will be taking place in Ann Arbor, but the Columbus

The O on Lane 352 W. Lane Ave.

The O on Lane will open for gameday festivities at 8 a.m., serving “Kegs and Eggs,”breakfast burritos, bloody Marys, mimosas and other select drinks. T-shirts for the game will go to the first 200 people.

Owner Ed Gaughan said he is expecting a packed house.

“It’ll get crowded, even though it’s [an] away game,” Gaughan said. “People hang on every play, throughout the whole game. When we get a win, it’ll be a celebration.”

The Library Bar 2169 N. High St.

The Library Bar is one of the earliest places to attend for festivities, with doors opening at 5:30 a.m.

It will have its own version of “Kegs and Eggs,” as well as breakfast burritos catered from Tortilla.

bar scene will be fully prepared for a day of football.

In what many anticipate to be one of the busiest days of the year, a select few bars shared their plans on how they will operate during “The Game.”

Ethyl & Tank

19 E. 13th Ave.

Ethyl & Tank is anticipating opening between 5:30 a.m. to 7 a.m.. Throughout the day there will be cocktail deals and specialty drinks.

The Little Bar 2195 N. High St.

In what will be its final Michigan game before being torn down, The Little Bar is scheduled to open at 6 a.m. for customers with a patio area featuring a large outdoor TV screen for viewing.

Manager Josh Pittro is also expecting a full crowd in attendance.

“I remember the game two years ago, the away game, it was one of the most full bars I’ve ever seen,” Pittro said. “That’s what I’m expecting to still have around here.”

Every year we anticipate taking the field for one of the most storied rivalries in sports: Our Ohio State Buckeyes versus the Michigan Wolverines.

Spirited competition is meant to bring out the best in all of us. I’m proud of how our defending national champions have led on and off the field this year, and I know Coach Day will have our team ready to compete hard and finish the regular season strong.

Revered as our football rivalry is, Ohio State and Michigan share a mission to create impact for the people we serve. Together, our institutions educate 120,000 students and conduct research that changes and saves lives. Through the annual Blood Battle, our communities give thousands of pints of life-saving blood.

And along with the rest of the Big Ten, we’re creating access and opportunity for the next generation of health care professionals, entrepreneurs, scientists, teachers, farmers and artists whose talents and leadership will keep America competitive well into the future.

At Ohio State, excellence is the expectation in all we do: athletics, academics, research, patient care and engagement. This game is a new opportunity for us to show the world what excellence means to us.

Ugly Tuna Saloona

195 Chittenden Ave.

The Ugly Tuna Saloona will open its doors at 8 a.m., with $4 mimosas served from open until noon. From 4-7 p.m., Ugly Tuna will serve $1 wells and $1 bombs. High Noon, Michelob Ultra and Suncruisers will also be available for $5.

With early openings and breakfast offerings, the Columbus bar scene will bring the Buckeye family together as they root for victory.

Let’s show up strong in Ann Arbor, and as always, Go Bucks!

Walter “Ted” Carter Jr. President, The Ohio State University

REILLY CAHILL

At Ohio State, cheering for the Buckeyes comes with an unspoken expectation: rooting against the Michigan Wolverines.

From crossing out the Ms on campus buildings and signs, to referring to Michigan as “The Team Up North,” Ohio State’s hatred of the Wolverines runs strong.

The hostility isn’t just a product of tradition, antics or campus culture. Psychologists say the rivalry taps into something far deeper.

Rivalries like The Game aren’t random, according to Maya Deutch, a third-year in psychology, and Arsema Haileyesuse, a fourth-year in psychology, who both are researchers in Ohio State’s Mood, Anxiety and Treatment Lab.

“It relates a lot to in-group and out-group bias,” Deutch said. “For a lot of people at Ohio State, this is part of their identity. People derive part of their identity from the group that they belong to, specifically, universities are a very big part.”

As Ohio State becomes part of a student’s identity, that in-group label starts to reinforce personal investment.

“People gain this sense of self, and it plays into your self-esteem, whether your team wins or loses,” Haileyesuse said. “So they’re kind of emotionally invested into the outcome.”

The investment can happen quickly, even for those who didn’t grow up watching The Game.

Ohio State students Luke Spadoni, a second-year in aerospace engineering, and Haley Sparent, a first-year in criminology, never planned on becoming Buckeye diehards. Both said being on campus reshaped their loyalties.

“I don’t like to hate a lot of people, but I hate seeing the maize and blue,” Spadoni said.

For Sparent, her shift is even more dramatic, as she grew up a Michigan fan and now favors the Buckeyes after being on campus for one semester.

“I guess I’ve always meant to be a [Buckeye],” Sparent said.

Deutch said the collective identity that comes from being a fan strengthens after wins and weakens after losses.

“Winning leads to collective pride and then the losses would create a collective disappointment,” Deutch said.

That group cohesion affects how people process the outcome, often leading to what psychologists refer to as attribution theory, which can be influenced by self-serving bias.

When applied to The Game, the theory is simple: If Ohio State wins, they were the better team; if they lose, it was because of bad luck, bad officiating or bad weather.

With the Buckeyes and Wolverines facing off on Nov. 29 in Ann Arbor, Deutch described that the collective

reaction on campus wouldn’t have as large an impact as it would for home games.

“It can feel more intense when you’re with the collective Ohio State undergraduate class versus just a few people,” Deutch said.

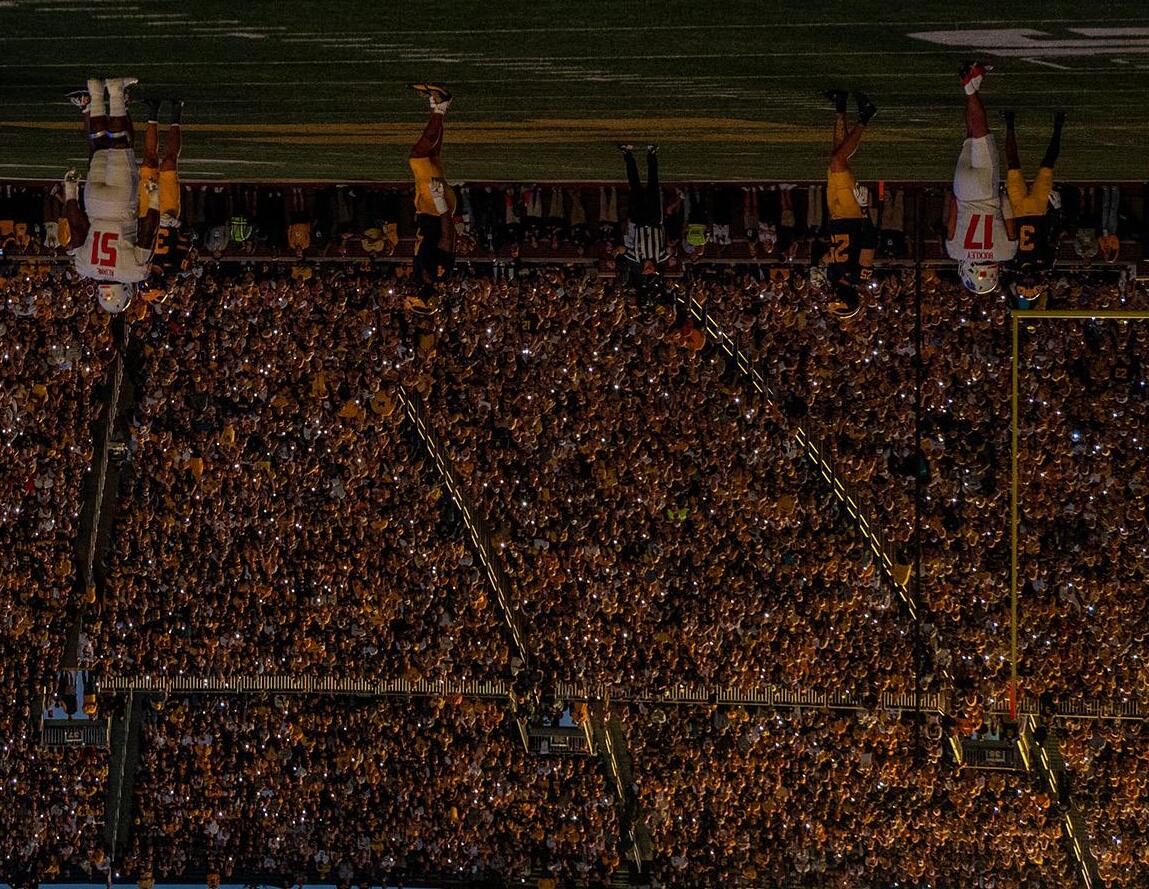

The rivalry impacts more than just students or die-hard fans. Each year, the game draws in a national audience that in 2024 capped out at 12.3 million viewers, the second-highest viewed regular season game last season.

“Because of the rivalry specifically, there’s so much tradition and media coverage surrounding it,” Deutch said. “There’s such a cultural emphasis on it, it becomes like a ritualized behav-

ior, because there’s such a tradition.”

With the renewal of the Ohio State and Michigan rivalry approaching, the anticipation on campus is building. And so is the angst toward the team that has beaten the Buckeyes in four consecutive matchups.

When asked to describe what he thinks of when he thinks of Michigan, Spadoni summed up that hatred for Ohio State’s rival.

“Cheating, bad sportsmanship and arrogance,” Spadoni said.

LIV RINALDI Sports Editor

The shirt stops passersby in their tracks.

It hangs in the window at Mid High Market at North High Street and 14th Avenue, white with black, bold, curly letters that proclaim, “Make Michigan Our Bitch Again.”

Some point.

Some laugh.

Some pull out their cellphones to snap a picture to send to family and friends.

“If I had $1 for every time somebody took a picture of it as they walked by,” owner of Mid High Market Austin Pence said. “I wouldn’t have to actually sell the T-shirt.”

The shirt has become one of the most recognizable—and photographed—pieces of unofficial rivalry merchandise on campus, alongside other iconic designs like Clothing Underground’s “Jesus Hates Michigan” T-shirt. Students sport their Michigan hate gear as a way to feel connected to tradition and for anyone who needs proof that rivalry week has arrived in

Columbus.

“I definitely don’t wear hate merch to actually hate anyone,” said thirdyear Grace Hein, who owns both the “Jesus Hates Michigan” shirt and a “Muck Fichigan” tee she got as a high-school graduation gift. “It’s more about showing my loyalty and representing my side—Ohio State.”

People kept buying it. So Pence kept printing it.

Hein bought the shirt even without having grown up in Ohio or knowing what the rivalry was until stepping onto campus for the first time.

Being on campus inducted them into the rivalry.

“All the M’s were marked out on

“If I had $1 for every time somebody took a picture of it as they walked by,” owner of Mid High Market Austin Pence said. “I wouldn’t have to actually sell the T-shirt.”

Pence’s idea for the “Make Michigan Our Bitch Again” design emerged around 2022, drawing on the rhythm of the President Trump-era slogan it riffs on. Pence winced slightly as he admitted it.

“As gross as it is to say, I think that was in the lexicon,” he said, laughing.

“And so we’re just trying to find a way to tie it into our feeling of hatred for the team up North.”

campus,” Hein said. “And no one would wear blue. All my friends did not say Michigan. We said ‘Bitchigan.’”

At Clothing Underground, of North High Street and Chittenden Avenue, owner Josh Hardin said their “Jesus Hates Michigan” design, created nearly a decade ago, still ranks among their most popular pieces.

“It’s definitely more acceptable

to wear it year-round, especially on campus,” Hardin said. “A lot of people joke that they’re going to wear it to church.”

At Mid High Market, the apparel extends from tame designs like a “Beat Michigan” tube top , to more explicit items like a shirt with “Ann Arbor’s Big House of Whores” decaled on the front in bold, red letter and a line underneath that states “Those Who Stay, Cheat!”

“Stuff that my grandma would blush if she saw, but college students seem to love,” Pence said.

It stops people. It makes them laugh. It brings them inside.

And on High Street during rivalry week, that’s more than enough.

“It’s about the humor and identity with the tradition,” Hein said.”I think that any and all Buckeyes will forever say ‘Muck Fichigan.’”

JACK DIWIK Managing Sports Editor

Ohio State vs. Michigan, known throughout the country as “The Game,” is widely regarded as one of the fiercest and most tradition-rich rivalries in all of sports. Its origins can be traced back to the Toledo War, the 1835-36 border dispute in which Ohio and the Michigan Territory clashed over control of the city of Toledo.

Since the first matchup in 1897, Ohio State and Michigan have played every year except 2020, when the game was canceled due to COVID-19. Entering this year, Michigan holds a 61-52-6 advantage in the all-time series. From the intensity of the Ten Year War between Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler to the modern era of College Football Playoff stakes and national championship implications, The Game has evolved while maintaining its unmatched significance.

There IS a superior intelligence “out there” – and a loving one too. Your Creator wants you to acknowledge Him, and come to know Him and His ways. Don’t be deceived by evolutionism. All creation screams of intelligent design! The odds alone of DNA evolving are virtually nil. Evolutionism is the only “science” that denies the law of degeneration (entropy). God alone is the origin of life, and the away life for Him – beware the “god” that does! What is about the Bible? It is the (Isaiah 46:9-10). Try (current situation) Psalm 83 and Zechariah 12; (reformation of Israel after nearly 1900 years) Isaiah 66:8, Jeremiah 16:14-15, Amos 9:9-15, Ezekiel 34:12-31, and Ezekiel 36; (suffering/crucifixion of Christ) Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53; (future situation) Zechariah 13:7 – 14:21; (timing of the 2 Christ) Joel 3:1-2, 2Peter 3:8/Hosea 5:14 – 6:2. “No one knows the day or the hour!” you cry? The Word says: 1Thessalonians 5:1-6. “Too hard to read and understand” you say? Try the KJV/ Amplified/Complete Jewish parallel bible (biblegateway.com). “It’s all in how you interpret it” you say? The Bible, despite numerous transcribers over hundreds of years, is remarkably consistent/coherent and interprets itself (2Peter 1:16-21). Beware of modern, liberal translations from “the higher critics” which seriously distort the Word! Finally, if there is a God, why is there so much evil? We have rejected God, and now see what it is like to live in a world where God has permitted us (temporarily) to rule ourselves. Give up your lusts, and come to your Creator and follow His ways (Jude 1:18-25). All that this world has to offer is as nothing compared to what He has in store for those who love Him

Michigan wins in Columbus 38-26.

2001-2002

Ohio State takes back the rivalry and win two years in a row.

Michigan wins in Columbus again once again, this time 35-21.

2004-2010

Ohio State is victorious six years in a row. Its longest win streak against Michigan in history to that date.

Michigan snaps Ohio State’s streak in Ann Arbor, winning 40-34.

2020

The Game is cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

2012-2019

Ohio State goes on an eight-year win streak, its longest in history. 2021-2024

Michigan has been victorious over the last four years. 2023 2024 The Michigan Wolverines are National Champions. The Ohio State Buckeyes are

SANDRA FU Managing Photo Editor

Shoulder to shoulder, I was watching players sing “Carmen Ohio,” when someone yelled, “Fight!”

The arm-to-arm lines broke, bodies shoved forward, and suddenly a herd of 200-pound, 6-foot-5 athletes surrounded me, surging toward the center of the field.

In the scuffle, my eyes started burning with an overwhelming smell of pepper spray in the air.

I stumbled out of the horde, gasping for air, just in time to see Jack Sawyer rip the Block ‘M’ flag out of Rod Moore’s hands.

That was the moment the rivalry had fully sunk in for me.

The Ohio State-Michigan rivalry isn’t the jokes, chants or mythology I absorbed from seven years of living in Ann Arbor, just minutes away from The Big House. It wasn’t even the hatred or the distaste for anything related to the Mitten State radiating out of the state of Ohio.

It was the way the game weaved its way through my life, reshaping the way I moved through campus, through the state and even my own family.

For someone who arrived at Ohio State as the kid from “That State Up North,” the rivalry became something I didn’t just watch, but lived.

And now, as I return to The Big House as a student journalist, I understand why this game defines people on both sides beyond the final whistle.

In fact, the game had defined me before I even knew it.

My father got his master’s in manufacturing in Ann Arbor, the same place in which my parents met at a graduation party later on.

When I applied to college, my parents were both working at Michigan.

Currently, my brother is a freshman at Michigan.

Football was never on our radar.

To this day, I have only attended one Michigan football game at The Big House.

But I grew up familiar with the giant looming Block ‘M’, the endless bleachers and my classmates’ hatred for all things Buckeyes.

Choosing to go to Ohio State wasn’t easy. It was a while until the dread of answering the question “Where are you going to college?” faded away.

The stares of judgment made me hate graduation, just standing in line, waiting for high school to be over.

I just wanted to leave.

But in Columbus, I walked into another pit of snakes.

As I stood in an auditorium filled to the brim with incoming Ohio State freshmen and their parents in July for orientation, I slowly rose to my feet after the faculty member on stage asked for anyone in the room from “That State Up North” to stand up.

I should have expected the stares.

The expressions were universal: Confusion, distaste, a hint of suspicion.

It was the first time I felt the weight of the rivalry not as something I’d grown up near, but as something that now defined the space I was stepping into.

In Michigan, being indifferent to football didn’t make me the odd one out.

In Ohio, simply being from Michigan made me the enemy.

Now, as I return to The Big House as a student journalist, I do so with a new perspective.

I’ve come to love this place: the peo-

ple, the energy, the traditions that make Ohio State feel like home. I know what it’s like to feel the surge of thousands of fans, to see the Block ‘M’ nearly planted into the Block ‘O’, and to feel the rivalry press in from every direction.

I’m excited to take it all in, and finally tell the story about all of

JACK DIWIK Managing Sports Editor

The narrative going into this year’s installment of The Game is a familiar and simple one.

Ryan Day needs to prove that he can beat Michigan.

It comes up on every radio segment in Columbus, every pregame show, and every conversation among frustrated fans.

Losing four straight will do that, and last year’s loss to the Wolverines in Ohio Stadium only amplified the questions. Ohio State was outplayed, outmuscled and out of answers. No one in Columbus pretends otherwise.

But what feels strangely absent from the broader discussion of Day’s 1-4 record against Michigan is the context surrounding three of those seasons. Outside of Ohio, the scandal that conveniently occurred during Michigan football’s meteoric rise from 2021 to 2023 is seldom discussed.

Nationally, it has been reduced to background noise, the kind of controversy people acknowledge existed but no longer feel obligated to revisit. But why is that?

the Committee on Infractions, Michigan’s sign-stealing operation ran from 2021 to 2023 and violated rules that had been in place for decades.

Connor Stalions, a low-level staffer, bought tickets under alternate names and sent individuals to opponents’ stadiums to record signals. He compiled scouting data and built what investigators described as an organized in-person scouting system. Inside the program, some staff members even referred to the operation as the “KGB,” a detail that would sound absurd if it had not been documented.

coordinator and now the head coach, deleted 52 text messages with Stalions shortly after the story broke, later attributing it to storage issues.

The public learned even more through last year’s Netflix documentary, which gave Stalions a platform to spin, evade, or joke his way around tough questions. His explanations often contradicted the documented facts, yet

We will never know. But that does not mean it did not matter, and it certainly does not mean it could not have.

the documentary contributed to the national fatigue surrounding the story: once something becomes entertainment, people treat it like it is no longer serious.

rule-breaking, and a national title season that unfolded during the same window.

We will never know. But that does not mean it did not matter, and it certainly does not mean it could not have.

That possibility, even if it can never be quantified, is part of why the dismissive reactions feel disingenuous. When the topic is raised, it is often brushed aside as a conspiracy or excuse-making from a fanbase unhappy with losing. But the NCAA’s findings are not rumors. They are not theories. They are the official record.

During this time, the Wolverines would go 41-3, beating the Buckeyes three times and winning a national championship in 2023.

But here is the point that keeps getting skipped over when the scandal comes up, and it is the part that fans in Columbus have not forgotten.

Acknowledging the scandal does not erase Michigan’s onfield success, nor does it excuse Ohio State’s failures in key moments. But pretending the two are unrelated, or that one has nothing to do with how the last three years are remembered, ignores the entire point of competitive integrity.

In August, the NCAA issued its long-awaited findings on Michigan’s in-person scouting and signal-acquisition scheme, and the details were as direct as they were damaging. According to

The operation alone was significant, but the behavior that followed made it larger. The NCAA cited repeated failures to cooperate, including attempts to obstruct the investigation. Stalions threw his phone into a pond before investigators could retrieve it, told others not to share information and directed interns to delete messages. Sherrone Moore, then the offensive

We will never know what impact, if any, the operation had on the outcomes of the games themselves.

We cannot rerun the matchups without illegally obtained signals. We cannot recreate momentum swings without the possibility that Michigan knew what was coming. We cannot unwind three years of competitive advantage, documented

Ryan Day still has to win. That will always be true. But the story of the past four years is not as simple as a record, as it includes a chapter that the rest of the country may be tired of hearing about, but that this rivalry will never quite separate from the scoreboard.

The stakes are higher this year. Moore isn’t coaching to keep his job, but he can’t get complacent. Because on Nov. 29, he’ll be coaching to make the playoffs.

Last year, the gameplan was clear, Moore stuck to it, and it worked. The Wolverines rode that momentum into a bowl win over Alabama, and the team’s energy was at an all-season high.

If there was ever a game for Moore to prove that he’s more than just a players’ coach, it’s Ohio State. Whether that means not quitting on establishing the run — a strategy that has worked in games past but could falter against the Buckeyes’ top-five defense — or opening up the playbook for Underwood, Moore can’t coach scared. He can’t coach like an underdog. He can’t coach his team like it’s one of the youngest in the Big Ten.

That doesn’t matter. As we learned from last year’s upset, coaching was so much more significant in that matchup than anyone thought. Ryan Day had the better team, but by electing to run on several key downs while neglecting his elite receivers, he coached a truly baffling game.

If everything goes as expected, Ohio State will travel to Ann Arbor undefeated, with a Heisman candidate at quarterback and a bevy of future NFL players on both sides of the ball. The Buckeyes will be favored, likely by more than a touchdown. Moore will not be expected to win.

be fired anytime soon. The latter is why this season’s game against the Buckeyes is so important.

separated into how you interact with your players off the field, and how you coach them on the field. The former is why Moore won’t

Being a good college football coach can be

Moore, maybe due to his youth, is able to form a bond with his players that some coaches just aren’t. Take Moore’s viral bluecollar jacket as an example. It’s corny, it’s ridiculous, yet all the players loved it, showing up to subsequent press conferences with their own workman shirts to match. Whatever you think about how Moore connects with his players, you can’t deny that it works.

Brian Jean-Mary said Sept. 10 in the week following the loss to Oklahoma. “No matter the situation, he’s the same guy every time he enters the room, every time he’s with the players. You know how much the players love him, because the special relationship he has with them.”

“That’s one of the things that makes him special,” Michigan linebackers coach

But ask any player or any coach about what sets Moore apart, and they’ll all say the same thing.

Former staffers described him as aloof and inauthentic, and a former player described him as “one of the worst human beings” he’d ever been around.

Look at Kelly, LSU’s coach, who reportedly didn’t even know all of his players’ names during his final season with the Tigers.

I’d even go so far as to say they love him. In this era of college football, that’s a bigger deal than it may seem.

Wolverines’ players really, really like him.

The more important reason why Michigan isn’t moving on from Moore anytime soon might sound simple, but it’s true: the

At this point in the season, Moore is winning. His players don’t seem to mind how a ‘W’ populates the schedule, nor do his coaches. In a sport, and a playoff format, where wins are valued above all else, it’s hard to argue against Moore through the lens of results.

86 passing yards. “I trust them. I think they’re really good and we will be complete, and we’re going to go try to win games.”

Moore said Oct. 27, two days after the Wolverines beat Michigan State with just

“I don’t think it has anything to do with Bryce’s ability or the receiver’s ability,”

Let’s start with the results. The Wolverines have won consecutive three games since the loss to Southern California. Yes, those wins have looked less and less convincing as the quality of opponent has decreased. Yes, the passing game is without a touchdown in two games. But Michigan is still winning. That’s all Moore cares about, and that’s something he’s made clear time and time again.

Moore’s seat not even a little bit warm?

Michigan forgot how to tackle. So why wasn’t

The Wolverines were outmuscled, outplayed and outmatched in Los Angeles. Michigan’s offense scored just 13 points, the Wolverines went a dreadful 2-for-9 on third downs and worst of all, it looked like

quarterback to a ranked SEC team with an elite defense is permissible. Michigan’s second loss was less so.

Whoever you want to criticize for that game, losing on the road with a freshman

Moore settled for two conservative field goal attempts, one from fourth-and-2 on the Sooners’ 14-yard line and another from fourth-and-2 on the Sooners’ 23.

Chip Lindsey, the Wolverines’ new offensive coordinator, didn’t seem eager to put too much on Underwood’s plate and the offense fell stagnant as a result.

Bryce Underwood completed nine of his 24 attempted passes for 142 yards and zero touchdowns.

After the Oklahoma loss, it was easy to look at the box score and blindly direct blame. Michigan’s freshman quarterback

The Wolverines played timidly on offense in their first loss, and were dominated on both sides of the ball in their second.

The No. 18 Michigan football team is 7-2, and a lot of external noise is focused on that second number.

Sherrone Moore won’t be joining that list.

This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone, but — regardless of The Game’s outcome —

arlier this season, Louisiana State fired Brian Kelly and Penn State fired James Franklin: two prominent head coaches at the helm of notable programs with preseason playoff hopes. They’re just two of nine total college football coaches across power conference teams who have been dismissed this season, for myriad reasons.

Sam Gibson: Sherrone Moore’s job is safe no matter what happens against Ohio State. It’s still the most important game of his career

Stanford Lipsey Student Publications Building 420 Maynard St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1327 734-418-4115 www.michigandaily.com

ZHANE YAMIN and MARY COREY Co-Editors in Chief eic@michigandaily.com

ELLA THOMPSON Business Manager business@michigandaily.com

NEWS TIPS tipline@michigandaily.com

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR tothedaily@michigandaily.com

EDITORIAL PAGE opinion@michigandaily.com

PHOTOGRAPHY SECTION photo@michigandaily.com

NEWSROOM news@michigandaily.com CORRECTIONS corrections@michigandaily.com

ARTS SECTION arts@michigandaily.com

SPORTS SECTION sports@michigandaily.com

ADVERTISING wmg-contact@umich.edu

CECILIA LEDEZMA Joshua Mitnick ’92, ’95 Managing Editor cledezma@umich.edu

FIONA LACROIX Digital Managing Editor flacroix@umich.edu

ASTRID CODE and JI HOON CHOI

Managing News Editors news@michigandaily.com

Senior News Editors: Audrey Shabelski, Barrett Dolata, Christina Zhang, Edith Pendell, Emma Spring, Marissa Corsi, Michelle Liao

JACK BRADY and SOPHIA PERRAULT

Editorial Page Editors tothedaily@michigandaily.com

Deputy Editorial Page Editor: Zach Ajluni

Senior Opinion Editors: Angelina Akouri, Sarah Zhang, Liv Frey, Hayden Buckfire, Gabe Efros, Elena Nicholson

JONATHAN WUCHTER and ZACH EDWARDS Managing Sports Editors sports@michigandaily.com

Senior Sports Editors: Annabelle Ye, Alina Levine, Niyatee Jain, Jordan Klein, Graham Barker, Sam Gibson

CAMILLE NAGY and OLIVIA TARLING

Managing Arts Editors arts@michigandaily.com

Senior Arts Editors: Nickolas Holcomb, Ben Luu, Sarah Patterson, Campbell Johns, Cora Rolfes, Morgan Sieradski

LEYLA DUMKE and ABIGAIL SCHAD

Managing Design Editors design@michigandaily.com

Senior Layout Editors: Junho Lee, Maisie Derlega, Annabelle Ye

Senior Illustrators: Lara Ringey, Caroline Xi, Matthew Prock, Selena Zou

GEORGIA MCKAY and HOLLY BURKHART

Managing Photo Editors photo@michigandaily.com

Senior Photo Editors: Emily Alberts, Alyssa Mulligan, Grace Lahti, Josh Sinha, Meleck Eldahshoury

ANANYA GERA

Managing Statement Editor statement@michigandaily.com

Deputy Editors: Graciela Batlle Cestero, Irena Tutunari, Aya Fayad

ALENA MIKLOSOVIC and BRENDAN DOWNEY

Managing Copy Editors copydesk@michigandaily.com

Senior Copy Editors: Josue Mata, Tomilade Akinyelu, Tim Kulawiak, Jane Kim, Ellie Crespo, Lily Cutler, Cristina Frangulian, Elizabeth Harrington, Alina Murata

DARRIN ZHOU and EMILY CHEN

Managing Online Editors webteam@michigandaily.com

Data Editors: Daniel Johnson, Priya Shah

Engineering Manager: Tianxin “Jessica” Li, Julia Mei Product Managers: Sanvika Inturi, Ruhee Jain

Senior Software Engineer: Kristen Su

AHTZIRI PASILLAS-RIQUELME and MAXIMILIAN THOMPSON

Managing Video Editors video@michigandaily.com

Senior Video Editors: Kimberly Dennis, Andrew Herman, Michael Park

SARA WONG and AYA SHARABI

Michigan in Color Managing Editors michiganincolor@michigandaily.com

Senior MiC Editors: Isabelle Fernandes, Aya Sharabi, Maya Kogulan, Nghi Nguyen

AVA CHATLOSH and MEGAN GYDESEN Managing Podcast Editors podeditors@michigandaily.com

Senior Podcast Editor: Quinn Murphy, Matt Popp, Sasha Kalvert

MILES ANDERSON and DANIEL BERNSTEIN Managing Audience Engagement Editors socialmedia@michigandaily.com

Senior Audience Engagement Editors: Dayoung Kim, Lauren Kupelian, Kaelyn Sourya, Daniel Lee, Quinn Murphy, Madison Hammond, Sophia Barczak, Lucy Miller, Isbely Par

SAYSHA MAHADEVAN and EMMA SULAIMAN Culture, Training, and Inclusion Co-Chairs accessandinclusion@michigandaily.com

ANNA MCLEAN and DANIEL JOHNSON

Managing Focal Point Editors lehrbaum@umich.edu, reval@umich.edu

Senior Focal Point Editors: Elizabeth Foley and Sasha Kalvert

TALIA BLACK and HAILEY MCCONNAUGHY

Managing Games Editors crosswords@umich.edu

Senior Games Editors: James Knake, Alisha Gandhi, Milan Thurman, Alex Warren

OLIVIA VALERY Marketing Manager

We are fast approaching one of the most intense and spirited days in college athletics.

When the University of Michigan and Ohio State University line up against each other at Michigan Stadium on Nov. 29, it will mark the 121st game in our vaunted rivalry.

Our student athletes have competed against each other since our inaugural game in 1897 (U-M won, 34-0), including facing each other for the dedications of Ohio Stadium in 1922 and Michigan Stadium in 1927.

Anything can happen on the last Saturday in November. Bo Schembechler, Michigan’s winningest football coach and an Ohio State graduate, said it best: “This is the pressure game. This is the big one.”

In my humble opinion, Michigan fans are the fiercest competitors I know (OSU President Walter “Ted” Carter Jr. may have an alternate view), and the atmosphere will be unlike anywhere in college football.

But once time runs out, we must unite behind something bigger: our shared mission in higher education.

These are challenging days for higher education. Yet society has never needed us more for expertise, healthcare, and discoveries that improve communities and nations.

Great universities like Michigan and Ohio State meet that need every day. We are indispensable to developing an educated citizenry, and there has never been a more critical time than now to reaffirm the public’s trust in us.

President Carter and I share a special bond as veterans. We understand strategy and victory. We also know that beyond a few hours on the football field, our universities are comrades in advocating for the value of America’s universities.

I will enthusiastically and proudly cheer for the Maize and Blue! Always!

And the next day, I will stand up for Ohio State, Michigan, and all our nation’s remarkable universities that serve the public good.

Domenico Grasso President of the University of Michigan

DRU HANEY Sales Manager

GABRIEL PAREDES Creative Director JOHN ROGAN Strategy Manager

to you, please visit store.pub.umich.edu/michigan-daily-buy-this-edition to place your order.

A coach who carries:

Biff Poggi’s journey beyond the game

To understand Michigan associate head coach Biff Poggi, you might need to dive into a bit of etymology.

At the dawn of competitive athletics in ancient Greece, it was common practice for athletes to coach each other. So by the time professional coaches came along, there was no official word for them. There was, however, the word “carriage,” and from that the term “coach” was born.

“I find it interesting that the word coach comes from the word carriage,” Poggi told The Michigan Daily. “The only purpose of a carriage was to take someone from where they were at that moment, to where they wanted to go, not where you, as the coach driver, wanted to go, but where they wanted to go to help change the trajectory of their lives.”

To Poggi, that idea isn’t an abstract notion or a few lines in a dictionary — it’s a guiding principle. From Baltimore, where he poured himself into a struggling community, to Michigan, where he’s the first person to ask a player how they’re doing, he’s always been about human connection. For Poggi, football is just the road. It’s the people who are the destination. ***

Poggi didn’t start as the carriage driver, but as a passenger.

From the moment he could run, Poggi knew he loved football — being just 3 years old didn’t stop him. Weaving through the house, dodging furniture with his older brother hot on his tail, he became completely enamored by the sport. As he grew up, football became so much more than just a game. It became his safe place.

By the time Poggi was a junior in high school, he had attended eight different schools, and not because his family had moved. Through the years, he grappled with anxiety and was haunted by the fear of failure as self-sabotage became routine. But through it all, football remained his anchor. Out on the field, Poggi was unburdened by the judgment of others. He was free to be himself.

Amid the tumult, along came Gilman School and a man who changed his life — his high school football coach. His coach didn’t just teach Poggi plays or have him run drills, he helped Poggi realize something no one had told him before: he wasn’t just a good football player, he was a good kid.

“This man put his arm around me and said, ‘I love you and I believe in you.’ And he proved it,” Poggi said. “That changed the trajectory of my life, and that’s what I try to do every day.”

That single act of care became a turning point. Someone had carried him when he needed it most, not because of football, but simply because they cared. And that stuck with Poggi.

After a collegiate football career at Pittsburgh and Duke, Poggi’s path strayed from the sidelines. Stepping away from the gridiron, he built a life in finance, started his own firm and became, by all measures, wildly successful. Yet as the years ticked by, his mind kept drifting back to the sport he loved and the coach that changed him.

Eventually, Poggi made a choice. He passed his firm on to some former players and returned to coaching.

ZACH EDWARDS Managing Sports Editor

Nov. 29, 2014, quarterback Devin Gardner dropped back in play action against Ohio State. Scanning the field, he found tight end Jake Butt wide open in the end zone for the Michigan football team’s first touchdown of the game.

Despite the highlight moment, the Wolverines ended up losing the game, and that was the last connection in the end zone between Gardner and Butt in a Michigan uniform. But years later, the two would be reunited in a new way.

In the 2013 and 2014 seasons, quarterback Devin Gardner and tight end Jake Butt connected on passing touchdowns four times. Gardner was reaching the end of his collegiate career in his fourth and fifth years with the Wolverines while Butt was beginning his eventual two-time All-American and John Mackey Award winning career.

The two were instrumental parts of Michigan’s success in the 2010s, going on to have brief professional careers before life brought them together yet again. Gardner and Butt both have full careers in media as color analysts for their respective channels; Gardner with Fox Sports and Butt with Big Ten Network.

Now on The Blue Print podcast where the two dissect the Wolverines from an analytical viewpoint, they have gone from connecting on the field to connecting again through the media.

Gardner always knew he wanted to go into the media, hoping to move into that profession after an illustrious playing career.

“It was always what I wanted to do,” Gardner told The Michigan Daily. “Growing up, I wanted to play football for 50 years straight, never take a break, and then, after I’m a Hall of Famer and all that, I’ll just start doing media.”

But Gardner’s playing career led him a different way. Gardner started at quarterback for his final two seasons with the Wolverines after making appearances at quarterback moderately through his first three years. After a brief four-year professional career playing for multiple different leagues around the world, Gardner’s path to the media was expedited.

But no matter how long or short his career was, his experiences at Michigan — in addition to the connections he made in his college and professional careers — allowed Gardner to seek out the latter part of his childhood dream. Through taking media availability on his own as a college student, Gardner built up the confidence made for the media.

“I would have to do media availability by myself, without the rest of the players and coaches, just because of my class schedule, so I would take it really seriously,” Gardner told The Daily “… I got a lot of reps in college being in front of the camera and talking to the media.”

In addition to taking that availability, playing quarterback helped Gardner adjust to being a member of the media

in a way he didn’t expect. Jeff Byle was one of Gardner’s first executive producers when Gardner joined Fox Sports in 2021. In the eyes of Byle, Gardner could do nothing right.

“Every week it seemed like I did nothing right and everything can be better,” Gardner said. “That’s exactly what you need because you have family who see you on TV, friends and see you on TV, former teammates, and you know that they’re not watching intently. But they love you, so they just tell you that you’re doing so good all the time. As a former athlete, you just know that when you’re only being patted on the back and all the good things are being said to you, that’s a mistake. It’s an easy trap to fall into and you can be complacent.”

As a quarterback for Michigan, Gardner frequently experienced the criticism of the media. Scrutinized for his play while on the field, the thick skin built while playing football — and especially quarterback — has led to a career in media where he now sought out that criticism from Byle and continues to search for constructive criticism.

“The greatest teacher in life, in my opinion, is playing football,” Gardner said. “If you want to go a step further, I think it’s playing quarterback, because you’re never good enough. It’s always something you could have done better. Everybody always has an opinion. And that’s kind of the same position you get in when you start to call games and you are in the media.”

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

Not many quarterbacks are awarded a game ball for throwing two interceptions and a meager 62 yards. Davis Warren is probably the one exception.

It’s been a year since the nowgraduate quarterback and the rest of the Michigan football team stunned No. 1 Ohio State. A long year for Warren spent recovering from an ACL tear. And a year of great change across the board for the Wolverines.

But that game, that rendition of The Game, hasn’t faded, nor will it for quite some time. For Warren, it never will.

“Won’t say where (the game ball) is, but I do have it,” Warren told The Michigan Daily. “That’s a prized possession, and gonna store that thing, put it on my mantle. And hopefully, my kids believe me one day when I tell them that that happened.”

While rehabbing his injury over the past 10 months, Warren had time to rewatch every pass he threw in The Game and over the course of the season — 15 times over, he estimates. He’s critical of himself. He doesn’t think beating Ohio State erases everything, even if the external criticism he’d faced all season went away in an instant.

Warren’s two interceptions in that game would have been remembered even if The Game went the other way. Both came in the second half with the score knotted at 10. The first set the Buckeyes up at the Wolverines’ 10-yard line. The second happened at the other end of the field, with Michigan just 3 yards away from a touchdown.

“I’ve probably watched every past attempt I had from last year, like the cut up of it in the film, like 15 times,” Warren said. “Just like going back and seeing what I could’ve done here, what I could’ve done there? What did I do? Well, what do I improve on?”

The rest of Warren’s season was also to be forgotten — unless you’re

Warren now trying to learn from your past mistakes. But for most people, Warren’s six interceptions across the first three games and his subsequent benching are memories lost behind his one defining win.

***

Last year’s game was more daunting for Michigan than any other recent meeting. The spread teetered around three touchdowns. While the Wolverines outwardly exuberated confidence, looking back, Warren isn’t afraid to admit he was nervous.

“I remember calling my dad on Friday night and I think he could tell I was nervous,” Warren said. “He told me after the fact, he’s like, ‘I could tell you were a little nervous.’ But then you just lock into your process.”

More than likely, Warren’s father was one of the only ones clued in on his nerves. In practice and around Michigan’s facility, Warren knew how he needed to act.

“I remember just going around the meeting rooms and saying, ‘Hey, if you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re probably right. So let’s just think we can every single snap. And I think when we look up at the end of the game, we’ll be happy with the result,’ ” Warren said.

Obviously, Warren wasn’t preparing to throw the ball 40 times or down the field much at all. He focused on the conservative gameplan and, more importantly, building top-to-bottom belief within the team. And even if not a star, as the quarterback, he was at the top.

On the first drive of the game, the Wolverines moved the ball just 25 yards. However, Warren saw their belief grow. They started pinned at the 11-yard line and right away they faced third-and-5. But Warren navigated the pocket calmly and found a receiver over the middle to pick up Michigan’s only first down that drive.

“I talked to J.J. (McCarthy) before the game, talking on the bus once we got to

Columbus, got off the plane and onto the bus,” Warren said. “And he called me, and we were talking, because we text a little bit during the week, and he was like, ‘Just be you out there, and you don’t have to be anyone else other than you.’ ”

Nobody expected Warren to go into Columbus and throw for over 250 yards and three touchdowns like McCarthy did two years prior. Warren is just not that effective of a passer. His play received heavy external blame for the Wolverines carrying a 6-5 record up until that point.

Warren wasn’t there to write himself into history alongside McCarthy, Aidan Hutchinson, Hassan Haskins or any of the other famed players before them. But in his own way, Warren rewrote his legacy in that game. ***

Repeatedly, Warren cited “resilience” as what made the upset possible. In the scope of the game, the season and life, resilience is what defines him after all.

Before headlines became critical as Michigan stumbled to uncomfortable depths for a program coming off a national championship, its new starting quarterback’s inspiring story spread quickly. In high school, Warren battled and beat leukemia. Then, he joined the Wolverines as a walk-on without a clear path to ever winning the starting job.

Yet, Warren beat out Alex Orji in fall camp. And suddenly a lot changed for him. The internal and external expectations mounted and his every doing was magnified — the same phenomenon he’s helping freshman quarterback Bryce Underwood navigate this year. Never is that pressure greater than during the end of November.

“Being in that moment, though, and on that field, in that environment, against the team like that, I think I was prepared for it,” Warren said. “Playing in big games before that and once that first drive, the first third down, I was like, ‘OK, we’re in this thing, and we’re gonna give ourselves a good chance.”

Unnerved, Warren met the moment and euphoria swiftly replaced

mounting disappointment. But to a man who had just defied what everyone thought, fate was cruel.

Up 16-10 early in the third quarter, Michigan was on its way to another upset over No. 11 Alabama in the ReliaQuest Bowl. Warren again wasn’t stellar, but steady enough to be part of the effort. His season, however, ended unceremoniously with an ACL tear.

“At first, it was a lot of frustration and disappointment,” Warren said. “And, God, like, what if I did this? I mean, I could have thrown the worst interception on that play, but my knee wouldn’t have torn. Or if that guy didn’t get a hold of my waist pulled me down, and stuff like that. So all that stuff goes to your head. Or if what’s called is a different play? But I realized pretty quickly that wasn’t a good way to go about it.”

After a season that went wrong for the most part, his triumphant ending was soiled by injury. Warren returned to the sideline in crutches against the Crimson Tide to watch the season he started, in which he was benched, criticized and praised, come to an end.

Following the game, Warren was told by doctors in Tampa that he needed surgery in two to three weeks. The next morning, Warren was on a flight to the Dominican Republic with his family, grappling with everything while sitting on the beach hundreds of miles away. ***

Warren’s first stop back in Ann Arbor was Michigan coach Sherrone Moore’s office. There, Moore reiterated his pride in Warren — especially in how he ended the season — despite all the criticism they both received throughout the year.

Going into that conversation, Warren was still unclear on what his next year would look like. He was going to be out for the next many months rehabbing while Underwood was already enrolled and graduate quarterback Mikey Keene was committed to compete for the job as well.

DOWNLOAD THE GO BLUE APP, YOUR AI ASSISTANT FOR LIFE AT U-M

JONATHAN WUCHTER Managing Sports Editor

Jordan Marshall wasn’t where he thought he’d be. He also wasn’t where he thought he should be.

Four weeks into his senior year of high school, Marshall found himself in his coach’s office. Archbishop Moeller started the year a meager 1-3. For a program coming off two consecutive state semifinals, it was disappointing. And for the player just named the Gatorade Ohio Player of the Year who finished third in Mr. Football, Marshall felt like it was on him.

“We lost two semifinals, and felt like everybody was kind of just looking at me like, ‘Come on, Jordan,’ ” Marshall told The Michigan Daily. “And for me, I just wasn’t having fun with football anymore. And one day, (I) broke down to my coach in the office and started talking to people about it, and from that point on, it really just switched for me that you have to be upfront about your feelings.”

Marshall hadn’t been himself for those four weeks. Crushed by the weight of expectations, he wasn’t loving football. His moment with his coach Bert Bathiany was pivotal. Not because it was the beginning of an eventual Archbishop Moeller return to the state semifinals. Not because Marshall went on to win Ohio Mr. Football. But because from that moment on, Marshall has put

“We had a really touching moment in a meeting, just me and him,” Bathiany told The Daily. “A lot of emotions probably came out, but I think it was the best thing that ever happened for our relationship and the betterment of the team. And I think it was a critical moment of his life, too, to realize that there were a lot of people on his side, and it’s not all on him, and he can lean on other people to help him out.”

That conversation was just over two years ago. The expectations are now even greater for the Michigan football team’s sophomore running back. He’s the featured back after junior Justice Haynes went down with injury. The Wolverines’ have no room for error with two losses. And soon, he’ll be the Ohioan hoping to quell No. 1 Ohio State.

In those two years, Marshall has prepared himself for this. He’s learned to lean on the people close to him, his mom more than anyone. He’s in touch with his faith, central to who he is. And he’s built a platform to advocate for mental health and to give back to the community however he can.

***

According to his mom, Amy Allphin, having a platform is what Marshall always wanted.

“He told me I want to be known by a lot of people and change the world,” Allphin told The Daily. “That’s what he told me when he was 8.”

From a young age, one of Allphin’s messages to her son was to be conscious

will be remembered. He still hears it from her, probably too much she admits.

As the spotlight has gotten brighter, from his days as a blue-chip recruit at Archbishop Moeller to Michigan, Marshall hasn’t shied away from how many more people each of his actions affect. Instead, he’s embraced his mother’s messaging and his position.

“I told him that multiple times, make sure you talk to the kids that aren’t so popular,” Allphin said. “Make sure you are respectful to everyone, probably way too much. He probably still hears it in his head. But not to change, to stay who he was, because he’s always been open and genuine, and that’s my favorite thing about him. Even when he talks now, he’s not afraid to mess up or be his authentic self.”

Marshall grew up with his mom in Cincinnati, Ohio. Close enough that she’s made it for every game this season. On top of that, the two talk at least twice a day.

Allphin is Marshall’s rock. She’s the basis of his morals and his faith. From her, Marshall learned to be an emotional person; it’s the backbone for why he champions mental health advocacy. When Marshall’s Michigan career didn’t go as planned last year, Allphin helped him get through it. Ahead of the Wolverines’ second game, Marshall had worked up the depth chart on special teams. But in the game against Texas, his first time seeing the field, Marshall suffered an injury that kept him out the next several weeks.

CONTINUED AT

picture — the glasses have evolved into something meaningful for the program.

There were fewer than 30 seconds left in The Game when former Ohio State quarterback Kyle McCord took the snap. It was the 2023 season, and both the Michigan football team and the Buckeyes had entered the game with unblemished 11-0 overall records. Trailing by just six points and advancing toward the endzone, McCord launched the ball just as one of the Wolverines’ defenders reached him.

As it sailed over the field, former Ohio State wide receiver Marvin Harrison Jr. ran a dig route and turned to catch the ball. Then-junior defensive back Rod Moore got there first, notching the interception to seal the win for Michigan. But before the game could resume, Moore had something to do first.

The stadium lights reflected off the lenses just right as they emerged from the case. Moore jogged to the sidelines, slipped the glasses on and flashed a grin at a waiting camera as his teammates gathered around, equally enthusiastic.

Miami had the turnover chain, Alabama has the turnover belt, but for the Wolverines, it’s the turnover buffs.

Introduced in 2022, Michigan’s turnover buffs have become a staple tradition on the defense. While the ritual itself is quite simple — snag the interception, don the buffs, take the

More than just style and a tangible connection to an influential city, the buffs are a reflection of the Wolverines’ gritty and confident defensive identity.

According to CBS, Cartier started manufacturing the glasses in the 1980s, with the model Michigan sports now, the Cartier C Decor, rolling out in 1983. They soon became known as “buffs” due to the buffalo horn that’s used to craft the frames. Detroit, flush with money from the automotive industry, embraced them immediately, and they quickly spread throughout the city.

But more than just a fashion statement, the buffs became a part of Detroit’s identity and a visual symbol of pride and success. You could hear about them in song lyrics and spot them around the city, but now, you can also see them on Michigan’s sideline.

It all started with former defensive back Will Johnson, a Detroit native. When he arrived in Ann Arbor, he brought more than just his coverage skills — he brought a piece of home with him.

During his freshman year in 2022, Johnson was brainstorming ways that the Wolverines’ defense could integrate fun into the team through celebrations. That’s when he remembered the buffs.

Contacting Zeidman’s Jewelry and Loan, a local jeweler, Johnson secured a pair of buffs for the team and introduced them

that season. Soon enough, a new sideline ritual was born as former defensive back R.J. Moten went viral for wearing them after an interception against Maryland.

“I know at Michigan, any time we got that turnover we were ready to go put the buffs on,” Johnson told azcentral. “Whoever got the most turnovers got to keep them too. We were all competing against each other to get the buffs, so it was definitely an incentive to go get the interception.”

While the buffs may just seem like a prop that’s passed from one player to the next, they serve a greater purpose on Michigan’s sideline: They’ve become not only a crowd pleaser, but a unifying factor.

“It keeps the crowd engaged, the team involved,” junior defensive back Jyaire Hill said Tuesday. “Like, ‘Oh, he got the buffs. I need the buffs. I want everybody to get the buffs.’ I really enjoy it, it’s fun. It’s new, a little Detroit thing.”

This lighthearted competition serves to galvanize a defense that’s centered upon a shared identity and collective sense of pride. Vying for the opportunity to wear the buffs, the Wolverines’ already physical unit has a little more edge each time they step out onto the field.

However, it’s not just about competition.

According to senior defensive back Zeke Berry, it “feels a certain way” when you put the buffs on — a feeling that the whole defense takes pride in. For a program built upon its defense, the buffs

added something different — a touch of playfulness and swagger without undermining the work behind it.

The buffs hold meaning for the Wolverines because, like in Detroit, they serve as a symbol of their identity. Michigan’s defense has long been known for its physicality and power, but the buffs have added a layer of personality. Under the lights, the glasses do more than just sparkle. Serving as a celebration of their execution, the buffs mirror an unwavering confidence in the Wolverines’ defensive identity. It’s this blend of substance and style that’s made its way into The Game.

Over the past three years, Michigan’s defense has recorded two turnovers in each matchup against Ohio State, one of which was Moore’s 2023 interception, after which he was sure to don the buffs.

Heading into this year’s meeting with the Buckeyes, the Wolverines’ defense currently ranks third in the Big Ten for interceptions. While it’s uncertain, if history may serve as any indication, another Michigan defender might very well find themselves wearing the buffs on one of college football’s biggest stages once again.

The buffs don’t stay on long. A quick photo, a grin and then it’s back to work. But for that brief moment under the lights, Michigan’s defense shows exactly what it’s made of — power, pride and a touch of the grit capital.

ZACH EDWARDS Managing Sports Editor

For the East County Lions, Zeke Berry lined up under center. Although that eighth grade season was the last year he would play quarterback, Berry continued to find the end zone in high school.

During his senior season at De La Salle High School in California, Berry scored a touchdown five different ways. He scored on the ground as a running back, through the air as a wide receiver, throwing on a trick play after a backwards pass and as a punt and kick returner.

He showed versatility as a senior, but even as a freshman Berry impressed with his raw talent. De La Salle coach Justin Alumbaugh had a very clear first impression of Berry when he pulled him up to varsity as a freshman for the postseason.

“Zeke’s a freak athlete,” Alumbaugh told The Michigan Daily. “There’s no doubt about it.”

With older brothers who played football, Berry naturally gravitated toward the sport as a kid, starting to play when he was only 4 years old. Although he also ran track and played baseball in high school, mixing in basketball in the summer, a clear path was starting to form when Berry became a four-star recruit in football. Oddly enough, Berry wasn’t even recruited as a running back, his top position. He was recruited on

the opposite side of the ball as a safety due to his sheer athleticism.

Nonetheless, Berry focused all of his efforts on high school football no matter what position he was playing, using his raw athleticism and versatile skillset from other sports.

“He excelled at everything,” Charise Pointdexter, Berry’s mom, told The Daily. “He just went out there and gave it his all. He tried everything, every position. So if they needed him to play, he was a team player. Wherever they put him, he just went out there and gave it his best.”

But it wasn’t always natural for Berry. ***

Berry’s freak athleticism and raw talent was enough to get him on the team as a high school freshman, but the adjustment to the speed and style of varsity took a bit more time.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

SAM GIBSON Daily Sports Editor

Copperas Cove borders Fort Hood, the large army post situated halfway between Dallas and San Antonio. The little Texas town’s economy is propped up by the nearby base, and most of its residents are linked to the military. One of the roads that leads out of town and extends over rolling hills is named Tank Destroyer Boulevard.

LaMar Morgan’s father was in the military, and the Morgan family moved to Copperas Cove when LaMar was very young. LaMar and two of his sisters were raised by his mother, Sydell Morgan.

There’s only one high school in Copperas Cove. It’s one of those communities where everyone knows everyone. High school football is a point of pride, as it is in many small Texas towns, and on Friday nights, the town crams into the bleachers to watch the game.

But growing up, LaMar’s best friends played basketball, so LaMar did too. It wasn’t until eighth grade, when he made a bet with one of his friends to try out for the football team, that LaMar began to enjoy the sport.

Yet almost as quickly as he started playing football, LaMar worried he’d have to stop.

“I worked a part-time job plus worked full time for the school district,” Sydell told The Michigan Daily. “It was the lack of transportation and getting him back and forth to his practices. So he told one of the coaches that my mom’s lifestyle is the reason why I can’t play football.”

Sydell worked as a teacher for the

in-school suspension program while picking up part-time jobs at the same time to support her family. The coach at Copperas Cove High School saw potential in LaMar, and called Sydell. Soon enough, LaMar was getting rides from some of his teammates who lived nearby.

Whenever LaMar had a game, Sydell made sure to get time off to watch her son play.

“I felt bad, but I think I was doing the best I could for our family,” Sydell said. “… No parent wants to deny their child an opportunity, but I was being realistic with what I could and could not do.

I feel like I wanted his focus to be his education if he wasn’t able to play football. I was hoping things would get better so there would be a chance that, in the future, he could play football.”

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM