!ank you for contributing to the fundraiser for our magazine and making this issue possible!

!e Kudzu Review is produced with the involvement of Sigma Tau Delta chapter members.

!e Kudzu Review is funded in part by the Student Government Association and is a Recognized Student Organization at Florida State University.

!e views and ideas expressed in the contained works do not re ect those of the Kudzu Sta or the Florida State University Department of English. All rights revert back to their original owners upon publication.

Dear reader,

Hello! !ank you for picking up Issue 75 of !e Kudzu Review. ! is little magazine is brimming with creativity. From paintings to poems, we have had the privilege to platform a diverse range of voices and styles this semester. We sincerely appreciate every submission we received and the care put into each one.

I have been working for Kudzu for three years now. ! is is my $ rst semester as EIC, but I have had essentially every job that exists within the organization. I’ve been an editorial assistant, an assistant editor, a head editor, and now editor-in-chief. I’ve even been a contributor! ! is gives me a very thorough perspective of the e ort it takes to publish these 82 pages every semester.

When I joined Kudzu as a sophomore, nothing could have prepared me for the sheer amount of time every single individual involved pours into every element of publication. Our editorial assistants are remarkably hard working, our editors and assistant editors are diligent and deliberate with their work, and our masthead lives and breathes literature magazine 24/7.

I want to sincerely thank all of our sta members for making Kudzu possible. I am so insanely happy with Issue 75, and I know they are too. !ank you to Ryan Hunke, our faculty advisor. I would not have been able to do this without you. !anks to our masthead, John Brown, Sophia Orozco, Susana Zulaga, Elise Espano, Luciana Callegari, Fallon Herreno, Miyah Lebofsky, Mia Rampersad, Maddalyn Duisberg, and Madison Hillyer. !ank you for your dedication to Kudzu, your hard work really paid o . To our layout director Adalyn Pickett, the magazine looks beautiful, you and your team did a wonderful job. To Melina McGahey, Annabelle Argeles, and Kylee !omas, you guys were my rock this semester. !anks for always answering my frantic texts and Teams messages. And to our contributions, your art is incredible, and we are so honored to publish it. I have the unique pleasure this semester to be publishing a piece by my little sister, a freshman at FSU, and I am only slightly prouder of her than I am of all of you.

I hope you enjoy reading Issue 75 as much as I enjoyed working on it.

Talk to you in the next one!

Isa Hoofnagle Editor-in-Chief.

By R.R. Copeland

December 14th

Lubin, Poland

1939

For being so close to Christmas, the streets are strangely empty. !ere are no children to stand at the toy-store windows, fog up the glass, or leave $nger-print smudges in their wake. !e chocolatiers have closed their doors. It is quiet beyond the hum of street lamps and the patter of sleet on the shingled roofs.

A lone woman hurries along under a large black umbrella. She walks as if guided by a tune, with her chin up and shoulders back. Her $ne hair is as pale as her skin and coils into a tight bun on the back of her head. She is long and lithe, dressed all in black, with eyes of jade green. Her $nal destination is a townhouse-turned-storefront on the street corner with a bay window. When she enters, the bell above the door twinkles.

It is more workshop than store. !ough a cash register occupies the corner of the cluttered workbench, it is an a erthought. A man perches on a stool behind the counter, bent over a shoe of pink satin, needle in hand, as his glasses slide slowly toward the end of his aquiline nose. Beside him, amongst the piles of ribbon, leather, and fabric, rests a golden six-pointed-star where it had been discarded earlier that evening.

“We’re still going.” Says the woman, better known by her stage name, Lena Czajka.

“ !ank God.” Says her husband, who’s name is not known at all.

Lena abandons her umbrella and black coat; strips o her mittens, woolen socks, and boots, and ops into an overstu ed armchair beside a portable iron stove. Sitting sideways, she can stretch her bruised feet out toward the stove as she pulls the pins from her hair. She removes only two before a calloused brown hand closes around her white one.

“May I?” Asks her husband.

He knows he can, but she hums in assent regardless. He settles cross-legged on the oor behind her.

“How was the big show?” He asks.

“Passable. !e German does not know what he is looking at, but he likes to atter himself that he does. Luis convinced him to let us go.”

Her husband’s face twists. “I take it Luis has not changed his opinion.”

“He remains utterly una&liated. He fumbled the li with Marie, but he speaks German. It helped.”

“So it’s o to Paris?”

“At the end of the week. Will the shoes be done by then?”

“I $nished them this a ernoon. You should try them.”

“ !ey will $t.”

“Indulge me, then.”

Even if he had not asked, she would have.

!e phrase “$ts as if it was made for me” is o en overused, but in this case, it is the only apt descriptor. Her husband had made her hundreds of shoes, each one perfect, yet somehow outdone by the pair that follows. She is not the only ballerina under his care, but her shoes are always receive extra attention.

Gently, Lena rises up onto the platform of the shoes. She seems to hover for a moment, then uses her husband’s shoulder for balance to shi onto one leg, where she remains for several ticks of the grandfather clock in the workshop corner. When Lena comes down, a smile adorns both her face and her husband’s.

“Brilliant work, as always.” She compliments. “Paris will not know what to think.”

“ !ey will think of the woman wearing the shoes.” He says. “Which is what I want.”

“I wish you could come with me.”

“Maybe next year.”

!e evening is a quiet one. Lena will be gone for the holidays, so they exchange gi s in their home above the workshop over glasses of wine and lamb-meat pies. Lena receives a $ne ivory hairpin, topped with jade

to match her eyes. For her husband, she purchased a cloth-bound copy of Dante’s Inferno. It cost more than she will admit. Books have been hard to $nd these days.

When they retire to bed, neither is eager to sleep. !e sleet turns to snow outside, settling gently on the windowpanes. Moonlight speckles their quilts and highlights the dust idling above them. In the dark, Lena whispers, “Be careful while I’m gone.”

December 18th

Lubin, Poland

1939

!e train station platform is barren except for an old man and his grandson—both bundled in thick coats with caps pulled over their ears— and a lithe, pale woman in a black coat, who is best known by her stage name, Lena Czajka.

!e train pu s steam into the frigid December air. Lights glow within the empty cars. A blow of the whistle summons the passengers forward. !ough most of the compartments are empty, Lena settles in the one furthest down the car, placing her bag under her seat and a small, wooden box in her lap. Despite the few passengers boarding, the train sits in the station for most of an hour, belching smoke. Finally the compartment door slides open. A tall gentleman, equally as pale as Lena, stands on the threshold. He wears a grey uniform and matching hat, both with red accents. !e end of his nose, too, is red from the chill. He is the sort of fellow you would not think twice to pass at the grocery; he would smile politely when you locked eyes in the library, then both of you would entirely forget the interaction. !at is to say, he looks no di erent than any other blue-eyed young man. He looks frighteningly like Luis. !e most remarkable thing about him is the splattering of freckles across his nose.

“Where are you headed?” He asks. “Paris.”

“Ticket?”

He is not a member of the station sta , but Lena hands over her ticket.

“Is anyone traveling with you?” He asks. “No.”

“What are you carrying with you? Any papers?”

“No.”

He scans the compartment with a glance. His eyes land on the box in her lap and he holds out his hand. With an expression perfected from years performing, Lena gives it to him. He fumbles brie y with the latch, frown deepening. When the box pops open, any sign of malcontent ees his features.

“You are a dancer.” He observes. Within the box, Lena’s pointe shoes shine under the compartment’s lights.

“I am.”

“My daughter does ballet.” Says the o&cer, smiling now. “She’s eight years old in a month. I cannot dance to save my life, but that does not stop her from pulling me along with her.”

Lena smiles politely, eager for the train to leave.

“Will you be in Paris long?” Asks the o&cer.

“Until the new year.”

“Best of luck.” !e o&cer hands the box back and glances at her ticket once more before he withdraws. “Auf Wiedersehen, Miss Czajka.”

As soon as his footsteps withdraw, Lena doubles over the shoes her husband made her and utters a prayer in a language few would dare utter that year.

. . . . .

December 21st

Paris, France 1939

!e Palais Garnier is disturbingly subdued. Any other year, the lobby brims with laughter. Young boys act out the part of the nutcracker and imagine their sisters to be the rats, chancing them around their parent’s legs. !is season, the theatre is no less full, but no one lingers to converse. !ey sit in their seats, speaking in whispers, though no performer has graced the stage.

Back stage, the company walks through the last steps of warm up. Up close, their makeup appears grotesque; over-exaggerated. It smells of sawdust and cosmetics and coal. In the corner, a lithe pale woman—not so out of place now—steps through rosin sprinkled on the oor. To the outside observer, her $dgeting looks like nervousness over the performance. !at is not the case. !ough it is opening night, Lena

Czajka’s mind is far outside of the theatre.

It is the hum of the orchestra tuning which draws her back to the moment at hand. !e younger dancers take their places in the wings, muttering to each other in half a dozen di erent languages. Luis, who— like Lena—does not go on stage for some time, comes to stand beside her. He is in his full costume except for his mask: a huge, the heavy caricature of a nutcracker.

“Doesn’t quite feel real, does it?” He asks.

“ !e performance or the state of the world?”

“Both.” Luis grins. He is always grinning, especially at Marie, who has a habit of winking back at him.

“I hope the railways are open for the journey home.”

“ !ey will be.” Says Luis. “ !ings are not so bad.”

!e lights above them dim. !e orchestra transitions from tuning into the $rst measures of the overture. Luis bows lightly to Lena. “Merde,” he wishes her, then joins Marie as they wait for their entrance.

!e show runs smoothly from start to $nish. If you ask the performers, they always have things to nitpick. A step o timing here; a sickled foot there. !e audience of in the Palais Garnier, however, would have nothing but glowing admiration for the production. !eatre itself contains an otherworldly quality, but that night, it was tangible even to the most sti -necked show-goer. Children lean forward in their seats. Mothers bite their tongues as a dancer leaps and remains suspended in the air a breath too long. Fathers—though they are few and far between— see something more than a nutcracker and toy soldiers on the stage. When the rat king lies defeated, the auditorium explodes with applause, far more enthusiastic than one would typically expect at the downfall of a tyrannical rodent.

Far up in the balcony seats, a young gentleman watches the performance more intently than the rest of the enraptured viewers. He is short and mousy and a icted with a rattling cough, which is perhaps the only reason he is not elsewhere this holiday season. He is an unusual patron, for he came to the show alone, yet carries a bouquet of roses. When the nutcracker and Clara enter the land of sweets and the sugarplum-fairy takes the stage, he leans forward. She is who he came to see.

She is breathtaking. !e shoes on her

feet are a perfect extension of her leg. No one pays them any mind at all; except the young man in the balcony. He watches her steps, counting each second before the show is over. To everyone else, she is but another jewel in the crown which is the performance. When Lena concludes the piece, the intensity of the applause manages to pry a smile from her.

!e show ends with many bows and a standing ovation, a er which the performers hurry backstage, celebrating their success and critiquing what could be further perfected for the following night. Lena Czajka breaks away from the hubbub begun by Luis opening a bottle of champagne to the backstage door. It opens to a poorly-lit alley. By now, Lena has abandoned her costume in favor of her thick black coat and gloves. She carries a box under her arm as she steps into the light snowfall, blinking as her eyes adjust to the darkness.

A slim $gure walks into the pool of light ooding from the open door.

“You were beautiful tonight.” Says the young man. He is English. He holds a bouquet of roses.

“ !ank you.” Says Lena.

Had a stranger overheard them, they would have remarked that Miss Czajka has come a great way to see her lover. !ey think the pair standing so close in the alley could be no more than a moment away from a passionate embrace. !ey would smile to each other and hurry along as to not disturb the couple’s privacy.

“We collected as much as we could.” Lena says. “ !ough it feels like pitifully little.”

“Anything helps.” !e Englishman sti es a cough, tugging his coat collar higher. “Will you be in Paris through the New Year?”

“No.”

“You are going home?”

Lena nods.

!e young man coughs. !ough he routinely does so, this time does not seem to be the result of habit.

“My husband is there.” Lena explains.

“Ah ” he hides a wince beneath a tip of his hat. “I see.”

“Have the Germans done something?”

“No.” He reaches for the shoe box, extending the owers in trade, but Lena is not ready to let it go.

“ !ey have.” She says.

“ !e Germans have done nothing, to my knowledge, since I have been in Paris the past few days.”

“What did they do?”

!e young man pauses with his gloved hand a moment away from her. He does not retreat, but coughs once more. Lena pulls back on the box. His grip turns to a vice. For a breath, they are locked in a tug-ofwar, before the stage door reopens. Luis leans on the doorframe with a glass of champagne in either hand.

“Lena, darling, join us, won’t you?” He says, grinning. His teeth are as white as the snowfall.

Lena tucks her box into her coat, but she is too thin to fully disguise it. Luis’ mirth dims. His light eyes it to the young Englishman. “I did not realize you had company.”

“An admirer.” !e Englishman says. “I have a heart for the ballet.”

“I will be in soon.” Says Lena.

Eyes locked on Lena’s box, Luis sips his champagne. “You will catch cold out here, Lena. You should come in.”

“I will. In a moment.”

“ !e party is going on without you.”

Lena meets him in the doorway. In one motion, she takes the champagne from him and calls inside, “Marie!”

!e girl turns away from the gaggle of her fellow cast members. Her costume glints blue and gold. Champagne has turned her cheeks pink beneath her dark hair and dark eyes. Lena nudges Luis’ shoulder toward her. “Luis has been wanting to speak with you.”

Marie quirks her head. Lena pushes Luis more $rmly, and Marie steps to meet him. She catches his hand with a wink to Lena. Luis casts a glance at Lena as he throws an arm around Marie’s shoulders, his grin back in force. His cheeks rival Marie’s for their liquor-given rouge.

When Lena closes the stage door, her hand is shaking with more than the cold. She samples her champagne in a portion of half the glass, then extends it to the Englishman. Her lipstick has le a stain on the rim, but he accepts. As he drinks, Lena says, “Luis cares more for Marie than anything else. He does not think of much else.”

“And the girl?”

“She cares for Luis.” Lena says. “And she knows my husband. He makes her shoes.”

!e Englishman polishes o the champagne. Snow replaces the glitter of carbonation in the glass and begins to melt. Lena trades the box for the cup and the roses.

“I should be going before anyone else notices I am gone.” She says. “Have a good night.”

“Churchill ordered raids. In Poland.” !e words form a cloud between them, before fading into the wind. “ !e Germans have done nothing yet. But I thought you should know. !ank you again. You have done us an incredible service.” He turns to go, securing the package under his coat. “Oh, and Happy Christmas, Miss Czajka.”

Lena is le in the ally behind the Palais Garnier with a rose bouquet, an empty champagne glass, and the laugher of her troupe buzzing inside the theatre.

. . . . .

December 28th

En route to Poland

1939

!e trains are open, but they are empty. !e few travelers Lena encountered on the $rst leg of her journey are gone now. It is only her, her bags, and dozens of lonely train compartments. She watches the snow-kissed hills of Europe go by. It is mostly farm houses and withered $elds, but every so o en, she passes a uniformed company slugging west. Halfway through the trip, the white topped grass and the neat houses on the outskirts of a town turn into a black, sunken crater. !e train is moving fast. Lena only sees it for a moment, but she shuts the blinds of her window and stares instead at the buckles of her suitcase, rattling against the seat opposite her with each chug of the engine car.

A er several unexplained delays, the train glides into the Lubin station. !e lone occupant steps onto the platform, where two men in grey uniforms await her. One of them has freckles across his nose.

“It’s an honor to welcome you back, Miss Czajka.” Says the freckled o&cer. “I am sorry for the unanticipated delay. I am sure you are eager to get home.”

Lena looks between the o&cers and says nothing.

“If you would accompany us, I would be grateful.” He continues.

Lena walks between them, gripping her bag in both hands. Of all the excuses which pass through her head, only one phrase actually makes it past her frozen lips. It is not what she expects. “Did the British raids succeed?”

“Yes,” say o&cers in unison. Neither look pleased.

!ey reach a small side room, labeled baggage storage. !e freckled o&cer stops with his hand on the knob. “I realize this is unexpected, but I hope you can understand.” He looks back, sees Lena’s drawn face, and adds, “cheer up, Miss Czajka, this will not take long. She will only have a few questions for you.”

Lena has a split second to o er a brief prayer before he opens the door. Inside, a girl, perhaps thirteen, sits on a green trunk with her hands tucked under her to keep them warm. She has blue eyes and a freckled nose. As she sees Lena, she jumps to her feet. “Papa! I thought you were joking!”

Stone-faced, Lena turns to the o&cer. He shrugs. “ !e best Christmas present I could give her was to meet a real ballerina.”

“You danced in Paris.” Says the girl.

“I did.” Answers Lena.

“Were you Clara?”

“ !e sugarplum fairy.”

“Show her your shoes.” Says the o&cer, and to his daughter adds, “they are beautiful.”

Lena stands very still. !e girl is hugging her father and speaking, but Lena does not hear the speci$cs. She remains like that for quite a while, debating a lie, when the o&cer prompts, “Miss Czajka?”

“I do not have them.” She says.

At this, the o&cers glance at each other. !e father pulls his daughter closer, but she breaks away with an excited squeal. She announces, “You have a secret admirer! Oh, how romantic.” She bounces up to Lena and asks, “did he bring you owers?”

“Yes.”

“It’s a long way to go to visit someone in Paris.” Her father says.

Lena puts immense amounts of concentration into retrieving the roses without a hurried panic. !e owers rest in the very top of her bag, now dry and crumbling. Lena breaks o a dying rose and extends it to the girl. “For a lovely dancer.” She says. “Who might perform in Paris one day.”

!e girl accepts it with another squeal. Her father does not look as amused. His fellow o&cer slides the open bag from Lena without comment and begins searching.

“What happened to the shoes?” He asks.

Lena again debates a lie. Anything the considers seems absurd. She is le only with the truth.

“I gave them away.”

“To the man?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Miss Czajka, that is a violation of ”

“Don’t you know, papa,” whispers his daughter, “they only give them to their secret admirers. It’s like a ring.”

As the o&cer looks down at Lena, she thinks another prayer which blots out any other thoughts. Over and over again, the words, “God, please.”

!e o&cer’s daughter shows him her rose. He takes it; glances at Lena, then smiles. He tucks the ower behind his daughter’s ear. “Very romantic.” He says. .

December 28th

En route to Poland

1939

Lena walks the streets of Lubin like a ghost. Her pale skin matches the falling snow. Her black coat matches the burnt out rubble piles of what used to be homes. !ere are more boards than glass now in the road-side window panes. Her time with the o&cer and his daughter had delayed her long enough for the horizon to swallow the last traces of the sun. Her steps are slowed by dread. !e $rm answer of the o&cers’ “yes” is now evident to her as she passes a town home which has been scalped.

Her prayer has not stopped since the station. Since then, the

silent thoughts have become mutterings which fog in front of her, “God, please.”

When she rounds the corner onto her street, she closes her eyes. She takes several steps blind, heart pulse pumping as it never has before a performance. Finally, she brings herself to look.

!e townhouse-turned-storefront stands still. Its bay window spills a puddle of golden light onto the cobbles. Lena’s steps quicken. She is a pace away when the door opens to meet her with the familiar twinkling of the shop bell.

A thin, pale face greets her. It’s blue eyes meet her own.

“I am sorry, Lena.” Says its owner, who she only then recognizes.

“Luis?”

“I didn’t want to do this, especially during the holidays.”

“Do what?” Lena breathes.

“You can’t hide it forever, Lena.”

“What did you do!”

Luis shakes his head and goes to step around her. Lena catches his coat by the lapel. Luis is a head taller than her, but to any passersby, he looks like a kitten caught by the scru . “What,” Lena whispers, “did you do, Luis.”

“He deserves to know the truth,” he snaps. He pulls from her grip. “I’m sorry.” Before she can question him further, he pops his collar and trudges o down the injured streets of Lubin. Lena yells something a er him which should not be repeated.

By the time she opens the shop door, the $rst of her tears has frozen on her cheek. More follow as the familiar scent of satin and wax hits her. She does not know how long they have before the results of Luis’ e orts come to bear. She does not know if it is worth it to run. She drops her bag by the door mutters a $nal prayer into the palms of her hands, “God, please.”

“Lena?”

Her husband’s arms engulf her before she can look up. He plants a kiss on her head. “You are home late.”

“Too late.”

“Even on time is too late.”

She shakes her head into his shoulder. “What are we going to do?”

“About what, Love?”

“Did you not see Luis?”

“I did.”

“He has ruined us. Even if we get out of Poland, we still have Germany to cross ”

“I don’t want to leave. Certainly not because of Luis.”

Lena pulls back. She opens her suitcase and then begins on the rest of the shop, grabbing anything she deems important to throw into the already full bag. One of their books crushes the Englishman’s owers. “

!e trains are still running. If we go now, then maybe—“

Her husband’s hand closes around hers before she can grab his coat from the rack. He holds it even when she tries to pull away. To Lena’s surprise, he is grinning. She punches him in the arm, but it is not him she is angry at.

“ !is is not something to sco at.” She says, “they have been taking—we have to—“

“Lena,” Her husband catches her hand; places a kiss on her pale knuckles. “Luis came to tell me about your lover. In Paris.”

Lena blinks. “What?”

“He told me about your secret admirer. Behind the theatre. How you were giving him presents. !at he brought you roses.” By then, he is laughing. He kisses her again, $rst on the cheek, then the forehead, and $nally once on the lips. “He knows nothing of the shoes.”

Lena melts into his arms. Her laugher joins his. Taking her by the hand, he leads her upstairs. “It is you who gave me a fright.” He says, “you are late. I almost lit the candle without you.”

“I was detained.”

“Detained?”

“A little girl wanted to meet a ballerina for Christmas.”

!ey sit by the light a menorah burning the mantle, far out of view from the window. !e pointe-shoe maker reads aloud an excerpt from Dante’s Inferno. Lena opens the wine her husband procured for the evening. Together, they light the fourth candle.

December 29th

En route to Poland 1939

Typically, the young Englishman would have been miserable in the cold, bundled up with some tea and a book, and far, far away from the water. !is year, however, he occupies one of the few places aboard a ferry chugging along the Channel. !e listing of the vessel, the smog of the docks, and the constant mist would have been enough to dampen anyone’s temper, but yet, he could not wipe the grin from his features.

His fellow passengers were not so chipper. !ey wore matching tan uniforms, boots, and hats. For the most part, they slept, drank, or stared over the water at the fading lights of Paris. !e young Englishman approaches one of them with more boldness than he usually possesses.

“Do you have a knife on you?” He asks.

!e soldier in question passes him a clasp-knife without a second glance.

!e Englishman $nds a private corner of the ferry where he opens the box from Lena Czajka. !e shoes within are no longer pristine. !ey are scu ed and scratched; they smell vaguely of sweat and sawdust. !ey are still beautiful, but it is the beauty of use and cra smanship, not of immaculateness. With a small blessing upon both the maker and the wearer of the shoes, the Englishman digs the soldier’s knife into the toe of them.

!e maker of those particular pointe shoes takes great pride in his cra . Each pair he designs is constructed with care. It begins with layers of fabric, paste, and paper, stacked to form the box which supports the dancer. !ese particular shoes are made with choice pieces of material—pieces inscribed with names and numbers. Locations and dates. !ey are scribbled in tiny, looping writing. With each scrap the Englishman pulls from the butchered shoe, his smile grows.

Somewhere on the ferry, a soldier begins a part of O Come All Ye Faithful, which is picked up by his fellows. It is not entirely on pitch, but it is earnest, sung in at least three di erent languages across the small boat. !e Englishman $nds himself humming along as he unpacks piece a er piece of information from the pointe shoes of Lena Czajka.

Reach into the room and tell me of the smell of smoke and $ rewood, burning so ly as the summer wanes. Here, we can $ nally sing of its pain.

By Megan Caton

Leave heartache to air out on the coat rack, it’s the only use the old thing gets anymore anyway. Better yet, let it dance its weight down, bounding between tables and barstools— a beat that stirs dormant expectation from your core. I ask you: what will you whisper in the dark? In low-light your shadow fades into-me-into-you-into-me until we are stripped of our skin, the slowly pulsing blue-to-red-to-green lights tracing contours of each curve. We wait for the rhythm to crash into your bones, chattering your teeth.

Settle that lump in your throat; these walls make the night easier to swallow. With an itch in the air, that humble hum, and the pounding, rushing, feeling just past the checkered oor: a drumbeat—a dream—demanding to be felt. Take her gaze, the lover: she sits, swaying like the grass the owers once grew tall in—now they’re set on the table for her husband prancing on the keys—their stems swimming in a cherry-red vase.

Rest your legs, stretched out along these weary measures, ung into the air, falling upon us all like rain: so ly, at $ rst, half-fragments slicing just ahead; its small daggers making paths like gnats before they tap lightly and dissolve upon our skin.

Take his hand, the rain drum: it stirs-up our pain on the kit, bearing down so fast we can’t see his hand move, a steady stream like water out of the tap. His hands are the brush strokes of Balla, uncaged, center stage. We are pressing against the future.

Knock the dirt o your soles, hidden between the muck— We are one step from darkness. You whisper an answer, but with the scrape of your chair, they are lost to the wail of the saxophonist, $ nding extra breath in her lungs— you just might think it’s yours—me-into-you-into-she-into-me.

We’ve hung time around our throats and all but pulled too tight, these scarves are the scars woven by half a dozen sets of hands. So swing those strings around your shoulder, or lend them to that bass man who picks and strums those low and broken melodies, past those still stretching shadows, tumbling, thumping, thumbling, $ngers icking in soulful curls.

Close your eyes against the haze, now made sweetly strange. Salt runs slipping past skin and cheek, sagging in your seat; your esh rises as forever ying birds are the kiss of two lines in v ’s scribbled onto half-ripped paper wrinkles, somewhat soggy from sweating drinks—like the band, just heating up, they hope the fans will hold for the crowd. We let this downpour drown out our doubts, leaving only so sighs in the silence set against the brilliance before us.

Take this glass, $ lled with the reverberations of clinking crystals, like wind chimes, the rocks in each drink one of many—rattling out like birdsong between teeth and tongue.

By Edlyn Wernicoff

To those honking on the Schuylkill Expressway at Tra &c that that they didn’t start with a Hangover they couldn’t have predicted heading to a balding boss with a bursting ego

To those pumping the honkers’ gas because you can’t pump it yourself in the state of New Jersey & wearing a jumper to cover the tattoos from a Past that didn’t shape them & nursing a Heartache for Nostalgia of an old Ford they’ll never have

To those who grew old behind the counter at Sheetz & have a streak of pink in their hair because they were going to open for Madonna but had to work instead & are now played out somewhere between Camden County and Philadelphia

To those who sleep in the horse trailer in Woodward, Pennsylvania because the hay is warmer & 79 for a night at the SleepAway Motel is 79 dollars and a Dream too much & horses with heads bobbing aren’t too bad of company at all

To those who became Rodeo Stars and All Around Cowboys out under the Big Sky because they got o on the wrong exit somewhere between the City or Utah & a real shot at Big Money or Big Life or Big Love

To those with Permadirt on their hands not from the farm that Daddy couldn’t keep but from the Fear & the Daze & the dirty handles of Taxicabs and Bodega brand co ee, heading to O&ce Jobs they’d said they’d never have

To those who went—but never too far, who live for Schuylkill Rage or the quiet Big Sky; who’ll never see Alexandria or Denver or the gum stuck to the boot of the security guard at the Louvre—

!e world is large and you were going to be Painters and Poets, Rockstars and Astronauts, Lovers and Sailors, Mermaids on beaches— but you grew up to pilgrimage on the Shittiest Expressway East of Dallas and look like all around fools.

But maybe, oh Lordy maybe !e cigarette butts thrown out windows & $ve o’clock shadows & disappointed mothers & Dreams never ful $ lled & missing your exit & heading somewhere you never wanted is the truest of ways for all us lowlifes to live.

By Delaney Bolstein

Seventeen hundred miles from Pepper Avenue, you pirouette under e luster and hunger of Château Masonier’s last glass chandelier. I dared you to stare into the lapels of all those greasy monsieurs.

One more Viennese waltz until dusk, so now you must wait and stir, Embellished with a slipshod swipe of mascara and two pearls in your ears. Seventeen hundred miles from Pepper Avenue, you pirouette once more.

We were nine and a half at the grocery store when you found the answer. A paper calling, Miss June’s lavender ribbon, one bus fare to nowhere near, I dared you to stare into the promises of all those Pensacola monsieurs

I said “I love you” dangling our feet over the dock. You turned. You dip your hand in. “I can’t leave anything here.” “Look at me dear.”

Seventeen hundred miles from Pepper Avenue, you pirouette under.

I watched you once at Audubon Hall, a reverie in monochrome blush. September, and the freckles had already drained from your cheeks. I dared you to stare into the checks of all those New Haven monsieurs.

Dri ed across the ocean and now you call Butter y Weeds eurs, But they take care of you well. Remember his rosy oh-so-hot ears?

Seventeen hundred miles from Pepper Avenue, you pirouette, A er I dared you to stare into the lapels of all those goddamn monsieurs.

By Lavinia Williams

To think that’s what we all boil down to: a couple of $sh bones and a chunk of ginger at the bottom of the pot.

To think that every perfect moment is always ittering away into the trees already a $gment of your girlhood in tall grass and warm wind the rocks slipping from your feet as you climb the days slipping from your breath as you sit at the top of the hill in front of Ma’s white house the window ajar, goats bleating.

To think the slick of the boat dock will outlive us, will outlive the whale on the shore and the frenzy of our people, the oceans of blood, the sun on hundreds of backs the sweat on thousands of ribs.

And, when your sister pushes you o the quay, you’ll trust the waves enough to fall. to think we revel in it all.

Of course you weren’t thinking of slipping back then, because you hadn’t fallen on those rocks just yet and each day was an open coconut in your hands juice dripping down the sides of your cheek, head tipped back, drinking.

You’ll never truly wash all the salt out of your clothes or your skin or your family, even though you’ve tried, $ rst as a girl then as a woman tired of Islands and dingy boats tired of mountains and jungle

where every cousin is dead or dying, neighborhood’s emptying into the shallow husk of a calabash but they’ll always hear that golden parrot when you talk. To think you’ll always $ nd yourself back on Bequia’s shore.

II.

Hurricane Beryl 2024

Today there are no pawpaws on the tree and mangos litter the street up to Dorsetshire hill, but tomorrow we’ll walk to town with grandma where Home is a name only family can pronounce, as we took that one small thing back from the British. Plastic bags of homemade fudge bunched in our $ ngers you clutching yours like I’d ever dream of taking it from you, the sugar lining your shaky smile and glowing on the tip of your nose.

Tonight a er Auntie Anette comes by to drop o a fresh batch of cou-cou but before the house geckos start appearing on the ceilinglike stars, like crumbs in the palm of my vast hand you’ll let me in on a little secret and I’ll realize I belong here. And, tonight, when it rains buckets and the cacophony of croaking frogs drown out my dreams, the roof will leak and the Livingroom alone will $ ll three pots. Every morning, I’ll wipe up the puddles.

So we watch the sunset bleed molten lava, turning and toiling and darkening when met with the Caribbean sea waves forever breaking against the shore, beating that same tired rhythm into my heart a conch shell forever pressed against my ear.

By Ashley Boudreaux

“ desire is about vanishing. you dream of a bowl of cherries and next day receive a letter written in red juice.”

we go for a co ee, me and some kind of version of you. your peppermint tea smoking the air, matcha remnants greening my mug. i imagine it is winter; maybe not that winter, maybe not this winter, but some version of winter that lingers between a few years ago and the humidity of now.

my hand reaches for yours and slips through a mist with a heartbeat. you appear so solid, $ ngers wrapped around cup handle, an apparition, mirage of stability, a body i could step through with my eyes closed, only drops of dew on my skin to show for it.

we manage an attempt at small talk pleasantries of how have you been it’s so good to see you and wow, it’s been forever but really all we mean to say is i don’t recognize the shadow in front of me, have you always been this vacant, why did i never notice.

- anne carson

our conversation steps into the past and i can’t help but hear echoes of the way you used to say my name, your breath upon my neck, underneath a moon from many moons ago. i try to focus on the sound coming out of your mouth, try to ignore how complacently you speak of me, dig for any sincerity in your words. all i can come up with is the fact that your voice doesn’t sound quite so di erent.

i don’t know how to tell you that this still breaks my heart. that even a er all this time, despite the formalities, the moving on, the seeking closure, a younger version of me is still there sitting on cold stairs, waiting for you as the sun comes up. i don’t know how to tell you that some version of me still loves you. or at least, some version of you.

By Ricardo Lara

La conciencia latina se envuelve en el comal de una madre cocinando pupusas en Wildwood, Florida. Al ritmo de ese golpe de palmas blancas corre también el latido de un pueblo herido cuya marca es el olvido, y el sacri $cio del segundo al pan del momento y la remesa del mañana.

La madre erige su monumento en el vapor denso empañado en su ventana, y la conciencia se expande en ese queso que derrite las capas de la memoria, y tras el polvo ella aún recuerda a sus padres en su hogar nativo, y sus hijos en la otra sala.

En esa casa en Wildwood Florida, tras paredes de estuco pálido y un bajo techo, está y no está la resistencia, que va y viene, y entre la moción y la ausencia fallece, mientras la Migra1 cuelga sobre el pueblo antes de someterlo una vez más, al pan del momento, a través de los mares.

1 La Migra is an informal Spanish language term for US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, frequently used among immigrant communities.

!e latino consciousness wraps itself in the comal of a mother cooking pupusas in Wildwood, Florida. To the rhythm of those white clapping palms runs, too, the heartbeat of a wounded people, whose mark is forgetfulness, and the sacri $ce of each second to the moment’s bread and tomorrow’s remittance.

!e mother erects her monument in the thick steam fogging her window, and consciousness expands in that cheese that melts the layers of memory, and through the powder she still recalls her parents in her native home, and her children in the other room.

In that house in Wildwood Florida, behind pale stucco walls and a low ceiling, there is and there isn’t the resistance que va y viene, which dies between motion and absence, while la Migra hangs over the town, before subduing it once more to the moment’s bread, even across the seas.

By Renee Gaines

ecause the $ nal act of all kinds of love is to relinquish it (whether to death or the strangeness of another life separate from one’s own), in due time I will $ nd myself thrust into a new and confusing world colloquially called grief during my freshman year of high school—and by the time I will have mustered enough strength to put pen to paper, to say her name aloud at the tail end of my therapy sessions, or to walk through the street where her house sits vacant, I will have been too late on account of her being dead for nearly $ve whole years.

It will all begin on a random weekday. I will be going to bed when I check my phone and see her face plastered all over the screen, it will feel as though there are an in$ nite number of posts, comments, eulogies. I’ll $ nd the fundraiser as her family cannot a ord the funeral costs. I will not believe it (grieving people seldom do), but suddenly my eyes will get misty, and I won’t be able to breathe, and my whole body will tremble. I’ll have to take a seat.

I’ll $ rst try to reach out to our mutual friends. I’ll meet up with one of them, and he’ll tell me how badly he wished he did something. Anything. I’ll nod in agreement. Where I should see his tall, lanky limbs I’ll see hers, and he’ll see her brown eyes and not mine when he looks at me. !e grief will become a giant monster that chews us up and spits us out worlds apart from each other. He’ll move away, and I’ll never speak to him again.

!e funeral will be held a week later on my little brother’s birthday despite the big grey clouds that will roll over the skies to turn day into night and pour rain onto the funeral goers. I won’t attend for my heart will be so heavy as to prevent me from doing much of anything. I’ll look up her burial plot. She’ll be right next to her mother for the $ rst time in months. ! roughout this, I’ll remind myself that I was too late. Too late to tell her that she means more than she knows, too late to convince

her that there is something worth living for, too late to ask her if she needed help. !e assignments that sit in huge piles on my desk and crumple up in my backpack are too late. “Too late” is what my guidance counselor will say; I will have to drop some classes to save my grades.

In the ensuing nights where I’ll $ nd myself unable to sleep, I’ll look up at the stars: the stars which her eyes will no longer grace, the stars where she will reside permanently. I’ll rage at their $ xed nature. How could they stay so unmoved, so dispassionate? Why hasn’t every star fallen out of orbit and onto the ground in the absence of the world they should revolve around? How could people still play soccer in the $elds where she used to play? Do they not know that those are hers and hers alone? How could the strangers who walk on sidewalks and through parks taunt me by imitating her likeness, causing me to whirl around in the false hopes that she never truly died?

From then on, I will experience what it means to be haunted by so-called “living ghosts,” but the utter annihilation that is “to die” will prove much harder to bear. It will sicken me; it will turn my stomach into knots and lodge years of unsaid words into my throat.

Life will be cruelly indi erent to these things: the years will pass irrespective of the apathy of an Earth suspended in great nothingness and its equally apathetic populace. In my aimless and unending wandering through this new world that grief has thrown me into, I’ll $ nd myself in many places. In my room. In hospitals. In solitude. In denial. I will not $ nd much else. I’ll lose myself in an endless pursuit for her light, her friendship, which I will have assured myself must be hidden in some deep recess of the physical world, convinced by the words on her headstone: “no one is ever lost.”

Even still, there will be many days where people will tell me that I will move on, that the grief will subside, but I’ll come to realize that these statements are false. !e truth is that when I walk the stage to graduate, I’ll ash a half-smile for the cameras, but I’ll still be deeply saddened. I’ll be the only one who knows that there is a missing seat on the $eld and a missing family that should be cheering in the crowd, and the medals and cords I will have earned cannot counter the weight of that on my shoulders. I’ll be at work a month a er the ceremony, eyes stinging, burry vision, lips quivering. I will search for the words to describe the feeling and the familiar tremor I’ll feel throughout my body to my coworkers who stand around me, confused; they’ll not understand.

I’ll ask if I can have a seat somewhere instead.

But for now, I’m privy to none of this. Today I am 13 and so is she. We are at school again; I see her sneakers and I’m sure that they’re new. I’m mesmerized by the big stacks of bracelets on her wrists, and I am oblivious to what lies underneath them. We’re heading to the library, and I am standing on the tips of my toes so as not to lose sight of her while my body is shoved around in the mass of hungry children headed to the cafeteria for $ rst lunch in the same direction. When we get there, we sort books only for a few minutes as “library aides.” We’re standing idly in the $ction section where she points out all the best fantasy books. She is shocked that I admit to having never read the genre, but I promise her that I will pick some up when I get the chance. We sit at one of the tables to play games for the rest of the hour. She moves wildly and makes jerking movements with her hands in a game of charades, but I am stumped and come up with no answer. She laughs at me, as I am a terrible guesser. !e word is clearly “fencing.” She wins again, but I don’t mind this, of course.

When the librarian tells us we’re being too loud, we sti e our giggles. I avoid looking at her because I know that her smile alone is enough to elicit a $t of laughter from me.

Instead, I’m looking up at the skylight. !e air and the sunlight and the bright blue sky above and everything we touch is as young as we are.

!e clock says noon now. Before we are to be dismissed to second lunch and then to regular classes I ask if we have enough time to play another round. Perhaps of charades, perhaps of a board game. I’m not picky.

She tells me, yes, we have time, And I believe her wholeheartedly.

By Chris Robertson

Every time I set foot in his house, he would immediately make me take my shirt o .

Sometimes I would arrive, and he would already be shirtless, prompting me to follow suit. Sometimes I would walk in, and he’d still be wearing a shirt. !e shirt could stay on for another thirty seconds or maybe another thirty minutes, but always eventually he would take it o , and ask me to do the same. I never felt very comfortable doing this, and even less comfortable when there were other people present. I’ve been called a push-over before, and as a kid trying to maintain friendships I considered this a his way or the highway sort of situation. Maybe once or twice I said no, and maybe once or twice he as an eight year old called me a pussy or explained to me that this is what men do. I won’t sit here and pretend I remember speci $cs. It’s been like fourteen years.

His house was suburban. Massive. I grew up in a big house with little rooms, but this place felt large from the inside. I remember the way the dining room connected to the living room connected to the foyer to the front door that I never came through. Always the garage or through the back. !e majority of my time spent there was either in his room or the basement, which was also huge. !ere was a big brown leather couch that, in my head, could swallow me whole. A big TV that we watched TMNT or e Clone Wars animated series on (his favorite).

Never once, if my recollection serves me right, did he come to my house. Perhaps for a birthday party or something. But I was, by all means, always at his place. He had all the games, all the toys I wanted, all the space to do spoiled things with. A community pool, parents which alternated between his mom and her boyfriend and his dad and his girlfriend. He was my childhood introduction to divorce mechanics. I felt sorry for him because this was such a foreign concept to me. As a child I was inept in my understanding that it was criminally normal. I liked both sets of guardians and I’d tell him this. He would say that they all sucked and rambled on about how so until I understood that he was just mad that his parents weren’t together anymore. Again, maybe I wasn’t thinking this at the time. Again, it was like fourteen years ago. Or maybe it was thirteen.

It was exhausting. Being friends with him taught me about divorce, but it also taught me what ADHD was. Being around his older sister taught me what anger issues were. !ere was always something going on in that house, and I never found it in him to relax. Hyper is the operative word, and I could never match his energy despite my strongest e orts. By the next morning a er a sleepover I was usually begging to get picked up by my parents, or maybe that’s just me now retroactively hating this scenario I’m putting myself back into.

We were always playing pretend, up until the point where it felt like we had completely grown out of it. His favorite game was called “War”, which consisted of pretending as though we were soldiers and stalking around his house, $ ring Nerf guns at imaginary terrorists and other faceless enemies. On the occasion that there was more than just him and I there, we’d all $ght each other in a free-for-all, which always ended in someone getting shot in a bad place and crying over it. I remember one exclusively catastrophic evening that ended in some kid getting shot in the eye and weeping. !e 8th of November Big & Rich documentary was playing on the TV as the angels were crying and as we all lied down in defeat. Shirtless of course.

!at’s the last memory I have of being shirtless in that house, but there were others.

Away from suburbia and into the country hills with country stores and country ham, was another big house and another kid prompting me to be shirtless. It sat at the top of a hill, in my mind a mound of red dirt, surrounded by a quiet forest away from main roads and cul-de-sacs and community pools. A tall house, white I think, with a big front porch. A house made from the ground up by design and not modeled to look like the other houses behind the gate code. Behind the shadow of the house sat a peach grove. During summer we would camp outside amongst the peaches, feasting on them when we were hungry and pelting each other with them when we were bored. When you’re a kid, you’re always bored. !ere were lots of bruises and so peaches to be thrown, always. I can still remember the troubled sticky heat.

I don’t have much I want to say about the kid. So, the house: Naturally, I would end up shirtless in this house. His parents (together) shut the air conditioning o in the summer to save money. !e humidity rose up from the carpet and it smelled like dog piss. I took my shirt o to save myself. I can’t remember the dogs’ names but I can see them in my head pissing on the carpet oor.

!e rooms in this house were comparable to my own and there were many. !ere was the un$ nished basement where I watched him play Driver: San Francisco on the PS3. !ere was the living room, the room that smelled of piss the worst. !ere I watched him play Farming Simulator on the PS3. !ere was his older sister’s room, full of things I can’t now comprehend. I remember a radio that played honky-tonk music. I could hear it playing down the hall late at night when I slept over. !en the kid’s bedroom, where I would beg my parents to let me stay, so I could watch him play Batman: Arkham Asylum on the PS3 until he bored himself.

!e kid was two years older than me, well into his double digits while I was still in my infantile singles. I met him at the county fair on the day of my ninth birthday. From then on I modeled a lot of my behavior a er him. I said all the words he said and listened to all the music he did, wore all the same hats. I asked for a PS3 for Christmas in the hopes that we could play together. We never did. I ate tic-tacs obsessively because they were his favorite candy. I became him in a way, or I wanted to become him. But I never did.

He had a friend that was the same age as he was, two years older than little old me. Together, they were the best of friends. A lot of my shirtless time in that house was shirtless in the presence of this other kid. I hated him in a way. He was my introduction to envy. Together, the pair of them were my introduction to a lot of nefarious things. Curse words, R-rated movies, pornography–all things I wasn’t really ready for but couldn’t say no to. I tried, I think, to say no. I’d like to think I tried. But maybe I didn’t.

!e rooms in that house started to mean di erent things over time. !e living room became the place where the one I envied stole my iPod and started to play porn from it. As I tried to steal it back he dropped it and it shattered, to which I had to forge an explanation to my mother about later.

On New Year’s Eve, in that basement (un$ nished) was the place I tried my $ rst sip of champagne. Down there, the same night, they tried to force me to watch my $ rst horror movie. I just couldn’t bear it so I begged them to stop. It wasn’t even that scary but I begged them to stop anyway. Later on, when I had fallen asleep, they placed my hand into a warm bowl of water and I don’t think I’ve fallen asleep $ rst in the presence of anyone else since.

I spend a lot of my adult life trying to get back into that kid’s bedroom where what I don’t want to remember happened. I don’t know a lot of things when I try to remember it and yet I do all the same. When I try to remember it I always end up in another room. In another memory that might be mine.

We all rode around on dirt bikes and ATVs with no helmets on. We all sat on the oor. His property was endless and we were always getting lost and never making the same routes twice. !ey told me that they had a secret but would not share. I watched a friend dip below a ridge on his dirt bike right in front of me and drop o the face of the earth. !ey whispered to each other. When I came to where he fell, I stopped my four-wheeler at the edge of the creek bed that certainly hadn’t always been there. We were probably shirtless. He had dropped ten feet down and managed to stay on his bike. !ey told me they would share if I just did this one thing. He just looked up at me, covered in dirt, and smiled and we all laughed and laughed and laughed. I wanted to because I wanted to know. !ere was laughing and sunlight and boredom and voices of people and dogs and video games. I came close but I did not. !ey laughed at me and never told me the secret.

At some point I le that suburban house and never ever came back. At some point I le that lonely house in the mountains and came back but one time. Someone had died or someone was dying and my family came to visit. It was years later. It still smelled like dog piss. !e kid was there and I knew exactly where to $ nd him. His parents told me he was sleeping and I scaled the carpeted stairs in tiptoe. !e door of his bedroom was cracked just enough for me to see him. Shirtless and sprawled out over his bed. It was 4pm and he hadn’t yet woken up. It was winter and the sun was going down. I knocked and he looked up at me to smile if only for a moment before falling back asleep and that was it. !at is all it ever will be.

…

I never saw anything in myself shirtless, even less was what I imagined other people saw. Years later I found myself shirtless in front of someone on some other giant leather couch in some other basement just down the road from the suburban place where I spent all those days halfnaked, this time it was more so by choice. Or maybe I just felt like that’s the way things went. I didn’t know how to feel then and I don’t now.

I don’t know what I look for in life but I know something happened in those houses all that time ago. I know I can still hear

that honky-tonk music bumbling from down the hall and I like it, at times. Other times it makes me sad. I know I’ve never seen much in the way of men I might look twice at but at times there are some and I wonder where that comes from and If I will ever act. I don’t think I understand what it means to be a boy sometimes, and that makes me question my identity. I would go by di erent names and words If I had the courage to be accepted as something that’s a crossroads between what I’ve been telling myself I am all my life and what I don’t feel like, but not now. !ere is always still time. !ere is just so much time yet to be.

Nowadays I try to keep my shirt on if I can help it. !ere was a science to it, I suppose. Boys just want to see your skin and know you are the same. !ey want to know that you are men together and that you are entitled to war and dirt bikes and Nerf guns and being shirtless and not taking no for an answer. Saying bad words and being tall and strong and tough and liking football and Star Wars and video games. Well, to tell you the truth, I do like dirt bikes and Nerf guns and Star Wars and video games but I’ll be damned if I don’t keep my fucking shirt on about it.

I don’t remember the last time I took my shirt o against my boyish will. I suppose I’ve never had much agency, much choice. But, I’ve always had thoughts about the decisions I end up making. In the end: I did it. I did take my shirt o when I was asked to because I wanted to $t in. I wanted friends and I wanted to be like everyone else. I wonder sometimes what has really changed since then. Hopefully something. It’s been such a long time since then. It hasn’t been a short time at all.

By Mahalia Collingsworth

My most recent visit to my childhood bedroom felt like mourning something. I hadn’t meant to get sentimental, just a quick pop of my head in the doorway; a last sweep to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything I meant to take back to my real life. I hadn’t even bothered to turn on the lights. !e darkened $gures of my furnishings, standing still in their usual poses, passed under my gaze like strangers on a crowded sidewalk. Clothes lay scattered on the oor as they always do between visits when I am too desperate to suck the last ounce of company out of my every second in that great big house and leave myself no time for the laundry. It’s been a while since my life $t in those old drawers, anyway. It’s an uncomfortable truth I’ve accepted, like skin numbing to cold water, that I am a visitor in my own home these days. I acclimate, but every time I leave and come back, it’s frigid all over again.

I was content to close the door and head north again, to a cold city where I am missing all the most vital parts of me, when a heavy rain began its slow marching on the tin roof. It was such a familiar progression the $ rst, hesitant beats, then the light downpour, gradually getting louder until there is a full band parading on my roof. It is a song I have long had memorized, and its melody drew me into my room to sit on my bed in the dark and close my eyes to the prone shapes of my things and wonder how many songs have I missed while I’ve been gone? How many times have I heard it? How many moments like these did I live, unremarkably, unappreciated in the blend of day to day?

I can’t hear the rain up north. I hear cars approaching up the street outside my window, their low hum starting down the road and getting closer and closer to me, wishfully mimicking that familiar crescendo, until they roar on out of earshot much too soon. It’s not the same, but almost.

“Your childhood was me at my best,” my father told me last week. I don’t tell him that it was mine, too. I don’t tell him that I don’t know what it means that the whole world has opened up for me and all I can dream of is worn cotton sheets, sandy stairs, and little things I have already lived. I don’t know what it means that, if given the chance, I would probably turn my back on my biggest aspirations if it meant I could live and die under that tin roof. I don’t even think I really mean that, but it’s easy to weigh a choice you’ll never have to make. !e answer can change as much as I like, but nothing else changes with it.

By Glorimar Pagan

In the silver Pontiac Vibe, you told me you loved me, and it has taken me a while to believe you. But we’re packing up the trunk and starting the clock.

7 hours 5 minutes

You drive $ rst, I need my parents to like you. Miami is full of pretentiousness, and we don’t belong to it. I was raised under the Borinquen sun in a house with a big terrace and a large fountain in the back. !e house was beautiful but when our neighbor had the barrel of a pistol pointed at his temple, dad decided it was time to move away. When I read you my poems sometimes you cup my face with your fat $ ngers and kiss me while other times you just say that “it’s okay” and I hate the poem so horribly I tear it up. Florida is so boring to travel through, and I am trying to write but all I see is highway churches and toyotas speeding by. Ever since you told me you loved me, I keep staring at you for long periods of time to actualize you. I love when you are driving because I get to stare at you endlessly. I turn down to look at my notebook and all I have written is you, you, you, you, you.

6 hours 3 minutes

I want to ask you if you liked my family, the way I liked yours. Your grandparents live in a white picket neighborhood that hosts “!ursday Watchers” at sunset. A tradition where every week someone in the neighborhood blows a horn and everyone sits outside in the cul-de-sac drinking beers on lawn chairs. Your grandmother complains that the new house “is smaller than then she’s used to” but I had never gone to a house that has chocolates in the bathroom like a fancy hotel. I cannot even tell you the name of a fancy hotel, I’ve never been to one and do not know how much they are. But you vacation in the snowy mountains in ski resorts that overlook the gentle white abyss. You believe it to be

a genuine injustice that I have never skied or seen the Great Lakes. You name the states that you have visited like lyrics to a lullaby you learned as a kid but all the lullabies I know are in Spanish. No matter how hard I have tried to master the language, I am still nine years old crying to my teacher outside the class about how I do not understand the homework and can’t seem to pronounce the English words right. I have made the language a part of my identity now, I am a consquistador barging into the shore with weaponry intended for slaughter and false amiability. I am imperializing your language and I am not stupid just because I can’t read the homework. What does the word dessert mean and how is it di erent from desert? Every sentence carries a spiteful bitterness, I have taken your big words and used them to tell you how cruel you have been to me.

5 hours 21 minutes

Was your last girlfriend easier? I hate that she is named a er a Disney Princess. Most people don’t know how to pronounce my name, the teachers ask “ did I say it right? ” !ey did not. My parents tell you the story about how I went to a psychiatrist when I was nine and the psychiatrist warned my parents that I am tornado and if le loose I will destroy everything in its path. !ey meant it as a playful anecdote, but I choke up and I wait to see some ash of new understanding in your eyes. I wait for you to realize that maybe that doctor was not crazy at all and I am the mouth of Rincon drowning surfers and ignorant tourists.

4 hours 15 minutes

We stop in Orlando to visit your brother. !ey are tall and lanky, with long brunette hair and a pointed chin. !ey walk up in a grey tank top and black skinny jeans, they seem so di erent from you I am dazed when you introduce them as your brother. We wait for the food truck to call out that our order is ready, the conversation is sparse. “How are you?” “Not bad, you?” “Pretty good.” I wait for some familiar sense of recognition between you too, but it feels like you are meeting up with a distant cousin you haven’t seen since you were ten. My brother is my best friend, when I was young and o en heartbroken he would o er rough paper towels when he didn’t know how to cure my sobs, the material always le my eyebags red and pu y. “I like your brother but it feels like I will always be second to him in your life” I didn’t respond then, I did not know how. Now seeing you make small talk with a brother who looks and acts nothing like you, I understand there are things we will never understand about each other.

3 hours and 14 minutes

!e tra &c out of this city is irritating me, I am terri $ed that in the same silver Pontiac vibe you told me you loved me, you’ll take it back once you see that how bitter I truly am. Sometimes I do not let people merge even though I know that they will eventually end up merging in front of me anyways. I avoid my dad’s call for days, and when I’m really upset I cry in a really ugly way not like the Disney princesses do, their faces are framed in a perfect awless pout I cry like the rough gushes of wind in a tornado. I am not a patient person, you know that, and how obvious it feels when my leg is bouncing up and down. Your gentleness has no place in this jungle, cars blinking lights turning le and right, a horn blaring it could have be mine, tiny shu es forward only 100 feet in every minute. Do you know how fast this car can go? My dad let me $ nd out once, in an empty street on the drive home he let me press the foot on the gas harder and harder until it felt like I could not stop as if I would speed into a di erent universe. Scientists say there is no amount of speed that could allow someone to phase through a solid object but right now I think if I could press the gas hard enough we would morph into something in between real and not and phase through every car in this long line of tra &c.

2 hours and 3 minutes

! is is what it feels like to love you, the car is going 80 miles an hour and in the rearview mirror I see ashes of red and blue making me put my foot on the brake but they fade into senseless visions and I never do end up pressing my foot down. It is all pine trees and endless roads up here, and I know if we pulled over right now you could tell me what bird is chirping in the distance just by its cacophonous melody, you could tell me the Latin name for that plant burrowed by roots of the tree. In the tip of my tongue lies a truth I am too scared to tell you, but I know just like how inevitably this road will end that inevitably honesty will slip into a conversation you will hate. You laugh at the story about how I lied about having a lemon allergy. I hate the sourness of that bright yellow bolt, it’s sharp bitterness that people burn into their kitchens with wax. I told you about how the lie slipped from my lips and I paid the consequence with shame when my friend always told the waiters to make sure none of my food had any lemon in it. !e story would be comical to me too if it did not reveal such an ugly defect. When we get home and I tell you the truth about where I was that week we $ rst met that you have so romanticized I wonder if for a second you will taste that bitter lemon in your mouth just like I did.

1 hour and 1 minute

Two nights ago, when you told me you loved me, we came to my house and separated in the hallway. You were given my childhood room to sleep in, your limbs uncomfortably spread out across the twin bed. When I was a kid, I used to try to stretch my legs trying to get my toes to reach the end of that bed frame in hopes I was making myself taller. Now your lanky feet were hanging o the bed, and I was o to sleep in a blow-up mattress in my brother’s room. He was fast asleep when I went in, but I poked his shoulder anyways trying to wake him up, he groaned in annoyance. I whispered his name over and over again, the way I would two years ago, when we were only a room apart instead of seven hours. I was always coming into his room in the middle of the night to tell him about what crazy thing happened in the book I was reading or asking him to interpret some text from some eeting crush. I wanted to wake him up and tell him what you said to me but he turned his sleeping body to face the wall and me and him do not live a room apart anymore.

0 hours and 1 minute

I am usually a very sensible person, but I truly believe I am going to be in love with you for the rest of my life. It is a privilege I get to be so unrealistic. It is the $ rst day of the year, we are so young, the car is pulling into the driveway and in my future all I see is you, you, you, you, you.

By Kat Neal

!e sauce expired in 1987; I remember it as a balsamic or glaze or maybe even a steak marinade, but my mom says it was salad dressing. We stood in the yellowed kitchen, my mother, sister, and I, crowded over the muddy bottle and squinting at its label which had eroded to akes of colored paper sitting on top of roughed-white adhesive like peeling dry skin. Mom had won the 2014 “Death by Grannie” competition, beating out my 1999 cracker $ nd and Sarah’s 2002 jam jar. My mother aunted her prize (a crisp $ve-dollar bill) and tapped a $ nger to her lips, her silent-shush. We heard a creak overhead that could be Grannie’s house-shoes, or the radiator, or the pipes, or any of the ailments of this old English house snickering with us. We snorted and hemmed and hawed until the squawk of the second-to-last stair and the shu e of slippers approached the hall. !e sauce was shoved back into its ancient cupboard and we didn’t ask why she wouldn’t throw anything

away. Grannie leaned into the room to ask if we wanted to go to the chippy for takeout.

At eight, Joan Keeling was sent out of London to boarding school and countryside because there were fewer casualties and less Nazi bombs. !ere are no photographs of the train rushing her far from her parents, no relics of the dresses she wore in 1941, but she would occasionally recount an air-raid siren barging into her French lesson, sobbing for the children to run underground in one continuous wail. !ey called them Screaming Meemies, the sailing bombs, for the primal shriek heard overhead—louder, louder, pitch dropping to marrow-shaking closeness, a deep, deep rumble and then the quiet. I see Joan holding her breath, this dim bunker of children stuck at the inhale, listening for the impact. I see Joan’s eyes, frozen on a cement ceiling, matching the distant clap with the cardinal

points in her mind, unable to discern if it was her parents or someone else’s who were lost. !ey found her sleepwalking later that year, outside in her nightgown, standing in an old trench.

In my mom’s words: “Getting creative was the only way to take the awfulness out of it” so when we boarded the ight she smoothed our hair and taught us the rules of Constant Criticism—a point for every jab from Grannie, and Sarah said “Oh, you’re de$ nitely going to win that Mommy!” and she did, whether we knew it or not. When Grannie talked mean, her accent got posh and rose to a taunting lilt. !ere was something musical about her berating, too fast to know who was caught in the cross-$ re until later when we checked for shards of glass in our backs and tallied the splinters into points. She loved to ask what was wrong with you. What’s wrong with you, you Clumsy Oaf. Why did you do that? Grannie hated men, but she hated women more. Are you stupid? Are you stupid? My mother, making splitsecond jumps to defend herself or take it, my mother, brilliant to turn it into a game. Are you stupid? I can’t help but smile and know that my score is rocketing.

1956, Joan’s in her early twenties driving a horse-and-buggy across New Zealand selling Vitomeal to the farmers for their cattle. !e weekend comes and she packs a van with a mattress in the back, winds up the mountains as far as she can go, pulls over near the peak and skis her way down. Joan in snow-pants, back straight, bent at the waist, all lines and angles, all movement, all wind and speed. Joan doesn’t know yet that when she is eighty she will still walk three miles a day, that she will refuse a chair-li for her steep staircase.

I’m walking with Grannie, we’re with her greyhound in a wooded park, all three of us take turns shattering the thin sheets of ice that seal each mud-puddle. I can see my breath, I can hear a birdsong bouncing o the trees.

“Sylvia borin,” Grannie’s eyes track the song, wicked fast, “the garden warbler,” she raises her eyebrows at me and moves on. My family crowds around a fold-out card table, Grannie teaches me and my sister how to play Snap. Grannie teaches

me and my sister how to play Rummy. Grannie teaches me how to play with words—her tinkling glass of sherry leaves a damp ring on the green felt of the old table. Grannie’s greyhound is quiet and sprawled in a bed under the kitchen door that is tacked full of ribbons and awards for dog training. !e mantle bursting with pictures: Joan at the Great Wall of China, Joan skiing down a mountain in New Zealand, Joan walking through Spain, Joan the mad adventurer.

I hold Sarah’s hand through the airport, pulling her along and letting her drag me in turn. Mom will pick us up when we land in Manchester, Mom will let me roll down the window like I always want to, Mom will let me poke my head out into the rushing sweetness of the cold English air as we drive to the house Grannie died in. It’s 2018, Joan fell down the stairs and her greyhound barked and barked and barked and the neighbors found her. Mom is on the phone with her brother, her accent leaking out like a secret as she convinces my uncle to

turn the heat on while we sort through the house. I imagine Grannie in the dead of winter, the radiators silent and the central heating untouched, I see her sitting in the living room in a full coat and gloves like it’s still World War II—one small coal $ re burning in the corner. !e funeral procession drives from Congleton to Maccles$eld; my mom, sister, and I are squeezed into the car with the greyhound at our feet for 8.6 miles and the dog looks so sad. !e ceremony at the crematorium is bursting, the family underprepared and half of the town $ ling in until we run out of sitting room, the rest spilling outside the doors where they stand and listen and listen. My uncle gets details wrong in the eulogy, my mother reads a funny poem, I don’t know what to cry about so I don’t. Joan is cremated and maybe she is warm.

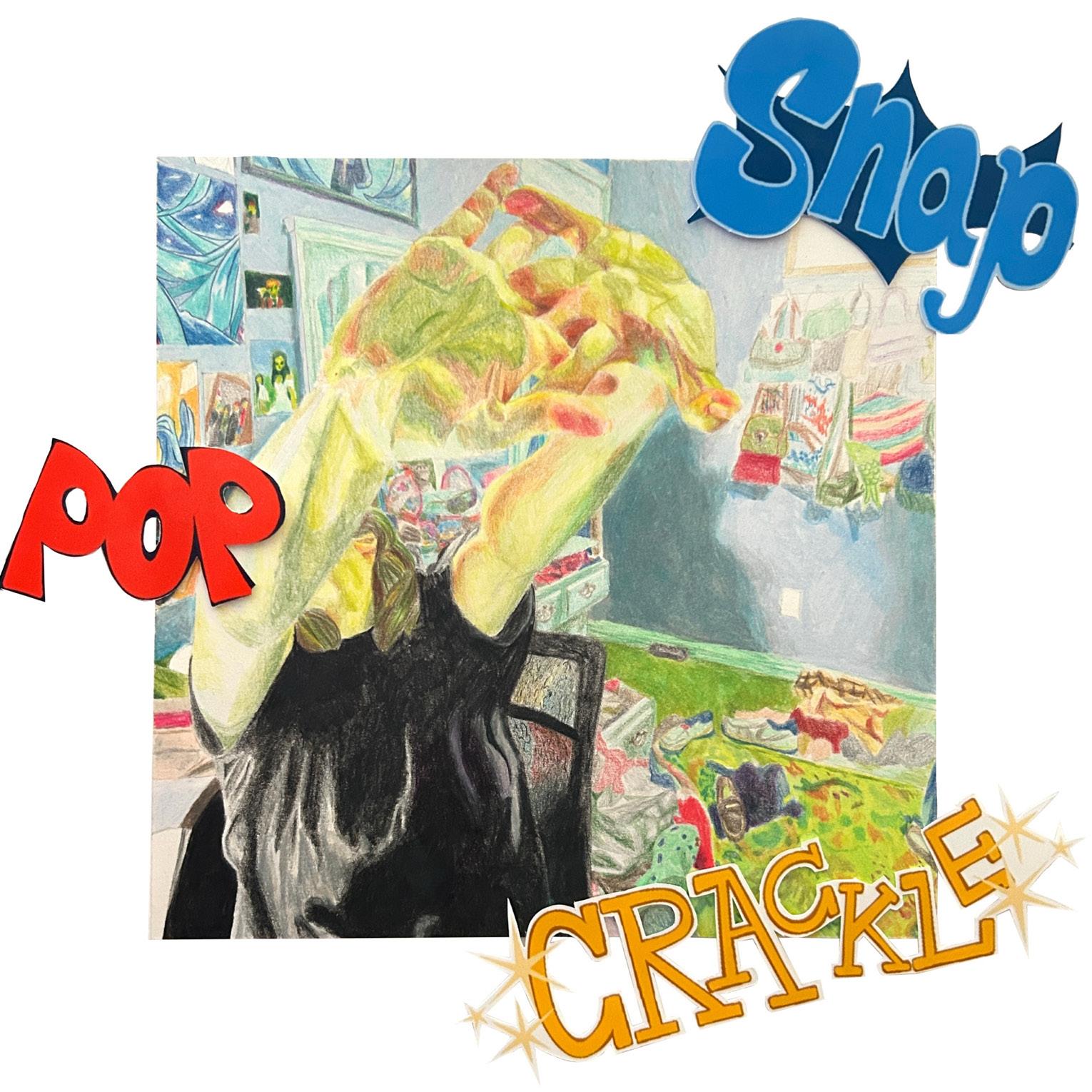

By Casey Drayer

By Sophia Hoofnagle

HEARTWAR M ED

HEARTWAR M ED

HEARTWAR M ED

HEARTWAR M ED

HEARTWAR M ED

HEARTWAR M ED

By Sophia Hoofnagle

A M I

By Sophia Hoofnagle

By Anna Garufo

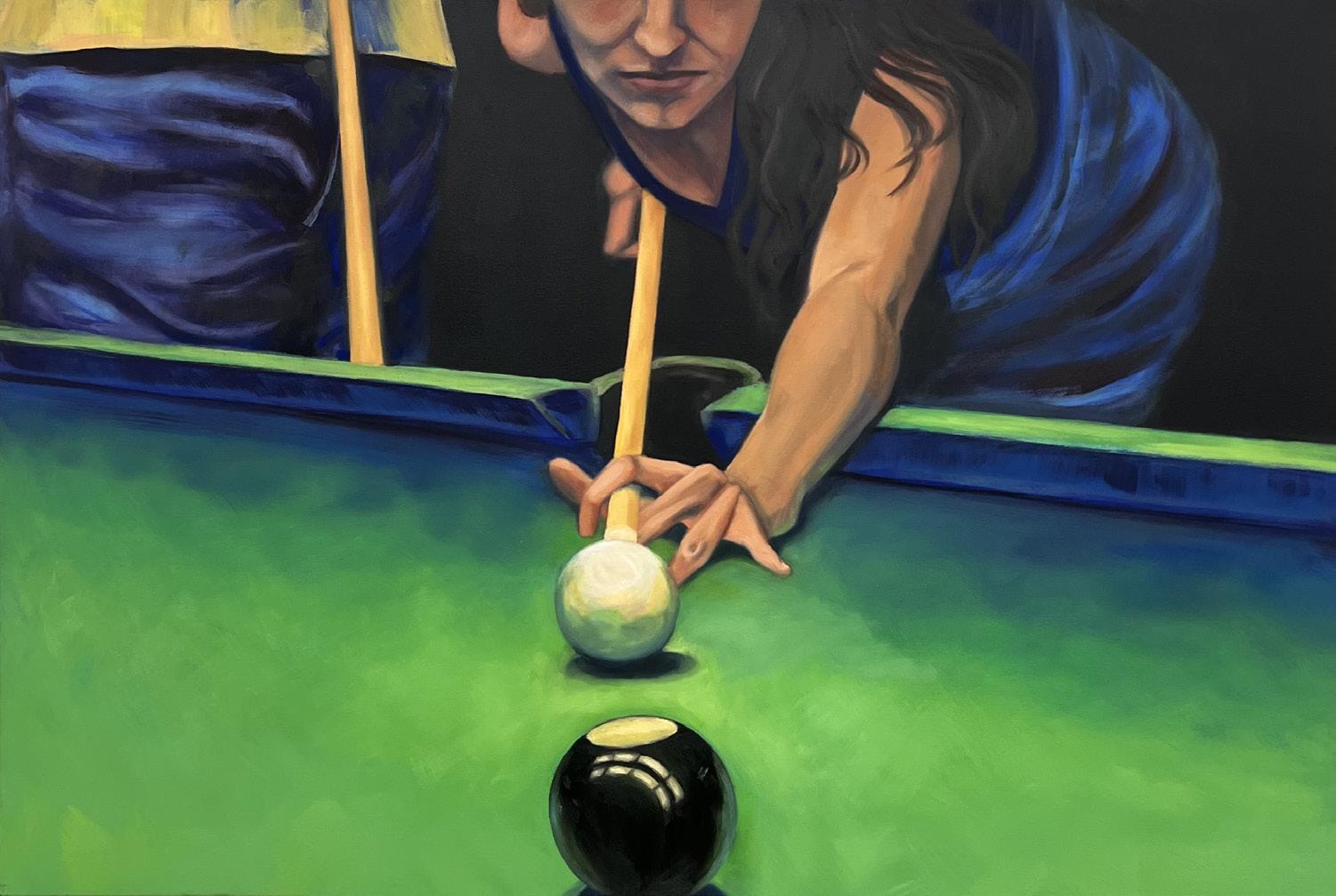

By Sally Zarling

By Michelle Howe

By Madailein AnzaldoSatterwhite

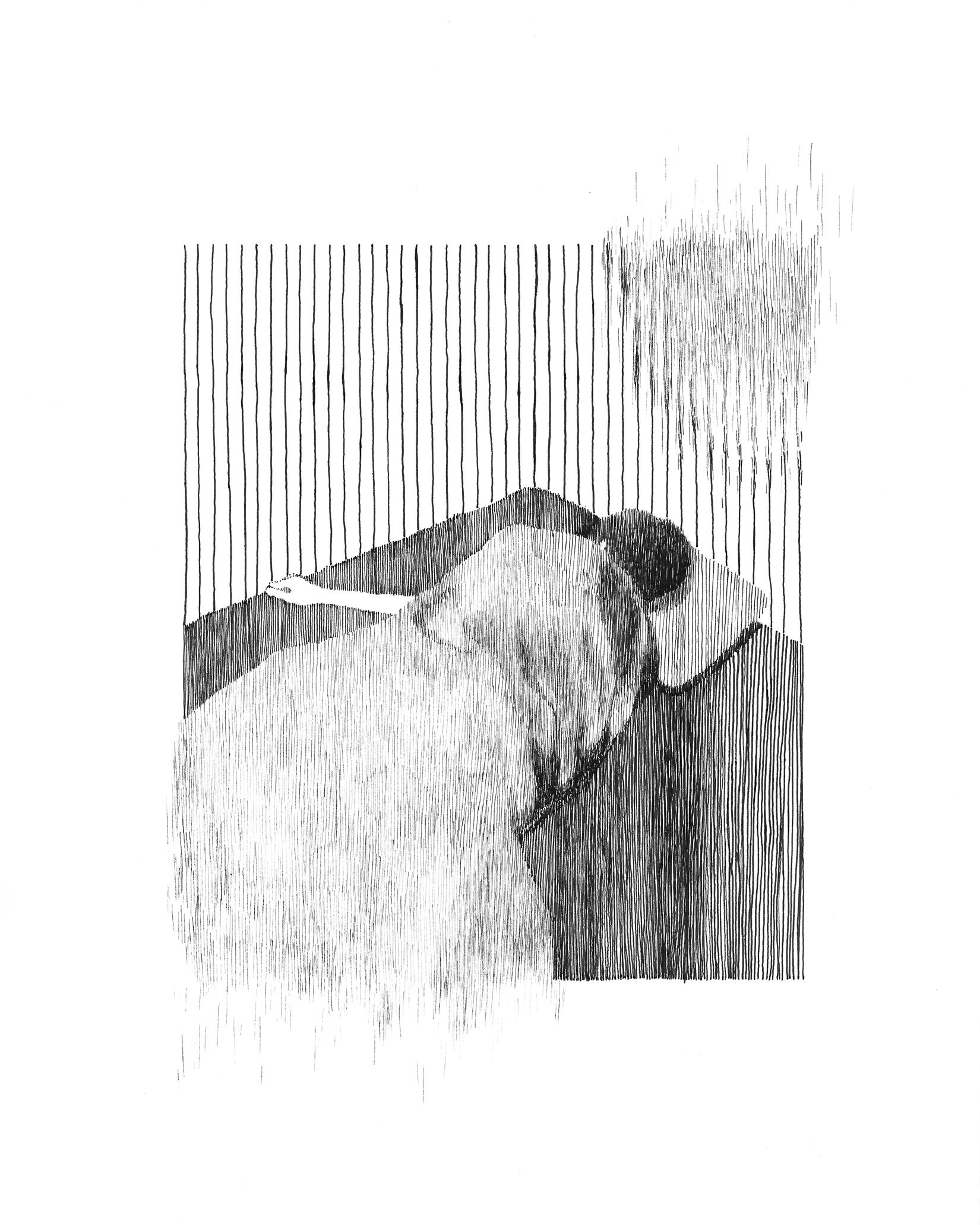

By Gwynevere Castro

Editor-in-Chief: Isa Hoofnagle

Managing Editor: Kylee omas

Event Coordinator: Melina McGahey

Treasurer: Annabelle Argeles

Faculty Advisor: Ryan Hunke

Head Editor: John Brown

Assistant Editor: Sophia Orozco

Samuel Armesto • Antonella Craven • Hannah Grinbank

Rachel Brady • Lillian Allen • Emily Harris • Ada Rye

Danielle McLemore • Amelie Galbraith • Kristen Cavanagh

Lauren Cavanagh • Yekaterina Nolan

Head Editor: Luciana Callegari

Assistant Editor: Fallon Herreno

Blair Bowers • Caprielle Grisham • Aditi Pawa • Ashley Skinner

Cheyenne Cro • Zoë Lieb • Addison Delgado

Eabha Phelan • Tin Tran • Monica Broome

Jase Jeralds

Head Editor: Mia Rampersad

Assistant Editor: Madison Hillyer

Sarah Duclos • Aubrey Tangen • Regan Gomersall

Maddison McCreary • Elsie Day • Camille Friall • Cole Kasprzyk

So a Canko • Kara Crowther • Savanna Pare • Ainsley Owens

Kylee Minus • Elizabeth D’Amico

Head Editor: Miyah Lebofsky

Assistant Editor: Maddalyn Duisberg

Caylee Smith • Melissa Regalado • Emily Kramer • Scarlett Whisnant

Samantha Fernandez • Mikaela Monzon • Sydney Graham

Kristan Davie • Grace Horner

Director: Adalyn Pickett

Kelsey Bonner • Isabela Reister • Kierra Keegan

Manager: Susana Zuluaga

Janet Chau • Elise Espano • Asia Louis • Karah Little

Shogo Oviawe • Myrna Zamora • Ezra Rosen • Kierra Keegan

Andrea Chouinard