Conservation The Art of

Indiana Waterways: The Art of Conservation

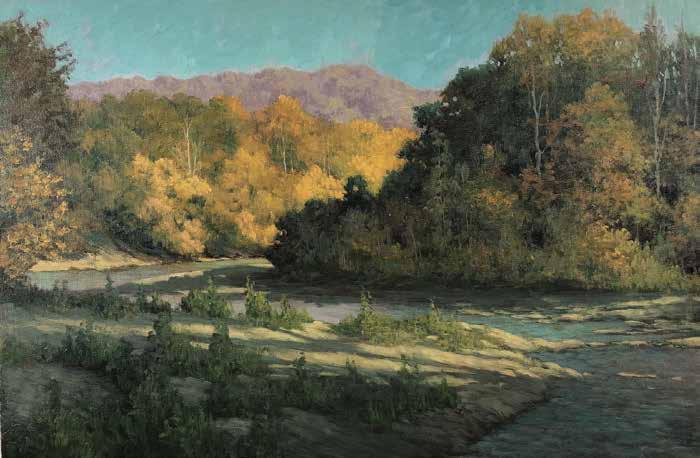

Dan Woodson | White River East of Muncie | White River, Delaware County

Dan Woodson | White River East of Muncie | White River, Delaware County

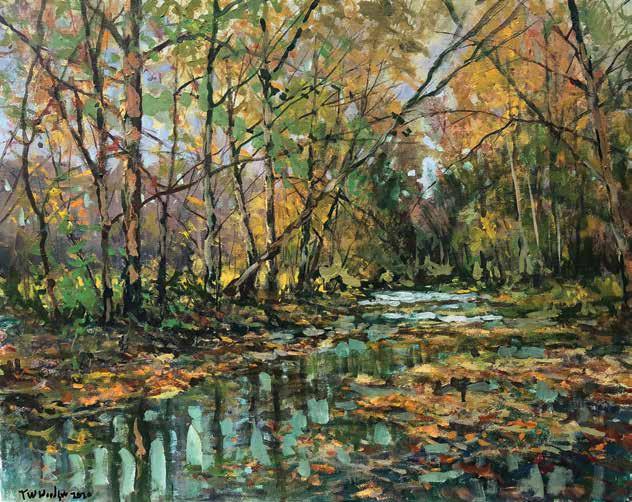

Tom Woodson | Salt Creek North | Salt Creek, Franklin County

Tom Woodson | Salt Creek North | Salt Creek, Franklin County

Curt Stanfield | Sunset Point | Sugar Creek, Parke County

Curt Stanfield | Sunset Point | Sugar Creek, Parke County

John Kelty | Black River Reflection | Black River, Posey County

John Kelty | Black River Reflection | Black River, Posey County

Avon Waters | Dusk on the Flatrock | Flatrock River, Shelby County

Avon Waters | Dusk on the Flatrock | Flatrock River, Shelby County

Indiana Waterways: The Art of Conservation

Artists: John Kelty Curt Stanfield Avon Waters Dan Woodson Tom Woodson

Essayists: Carson Gerber Jason Goldsmith Dr. Jerry Sweeten Juli A. Metzger, Editor John N. Metzger, Designer Avon Waters, Project Manager

Published by The JMetzger Group, 2022 thejmetzgergroup.com

Copyright © 2022 The JMetzger Group

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. For permissions contact: thejmetzgergroup@gmail.com / 765-744-4303.

Book and cover design by John N. Metzger, The JMetzger Group

Front cover: Tom Woodson, White River

Back cover, from top: Dan Woodson, Muscatatuck River at Vernon Curt Stanfield, Blackrock Niches

John Kelty: St. Joseph River Avon Waters: Lime Green Tree Screen

ISBN: 979-8-218-00589-4 (Hardback)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022940218

Printed in The United States

First Edition

This book is dedicated to the women and men of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, whose job it is to study and manage the natural resources of our waterways.

Featured artists:

From left, brothers Dan and Tom Woodson of Muncie, John Kelty of Fort Wayne, Avon Waters of Converse and Curt Stanfield of Rosedale.

Preface 13

Ackowledgements 19

Introduction.......... 20

Essay: Carson Gerber.......... 24

Essay: Dr. Jerry Sweeten 32

Essay: Jason Goldsmith 76

The Woodson Brothers 105

Artist Dan Woodson 108

Artist Tom Woodson 130

Artist Curt Stanfield 152

Artist John Kelty 176

Artist Avon Waters 200 Index 224

Dan Woodson

John Kelty

Avon Waters

Tom Woodson

Curt Stanfield

Photo: Kelly LaffertyGerber

Dan Woodson

John Kelty

Avon Waters

Tom Woodson

Curt Stanfield

Photo: Kelly LaffertyGerber

Preface

Artists often begin with an idea but later say the painting had a mind of its own and the piece went in totally another direction. Thus was the case with the Indiana Waterways project. Its evolution gained a momentum of its own. Like the four stages of a butterfly from egg to adult, the metamorphosis from the seed of this themed painting idea began during the COVID-19 pandemic, merely as something for friends to do until society reopened.

In February and March 2020 in the United States, COVID-19 began to change everyone’s daily lives and professional activities. All the artists on the project and “The Art of Conservation,” are members of the Indiana Plein Air Painters Association (IPAPA). Its monthly scheduled outings fell like dominos. Unlike business meetings that switched to online venues, live large outdoor art events like plein air gatherings of artists, didn’t lend themselves to online applications.

Fears of the pandemic forced the community of New Harmony, Indiana to disinvite the IPAPA event, the First Brush of Spring, which for the past 20 years attracted more than 100 artists to the scenic historic town. All the events, exhibitions and gatherings of many other organizations the project artists belonged to also dropped from their calendars.

At the time, the medical and scientific community had few answers about when all of society might return to being able to meet in groups and attend public events. The vaccines had not been developed yet. During the fall of 2020, society had some guidelines to allow people to meet outside or in small groups with spacing and personal protections. By then, most artists used social media or the telephone to stay in touch, forming small circles of friends. This pairing happened organically, based on each cluster’s self-interests. Communication among artists certainly remained broad, but COVID forced many artists to communicate more intentionally with a limited number of other artists, much as they would do on the side at in-person painting events.

Through social media, the group of artists featured in this book found comfort in regular conversation. Isolation from other artists was universal, something some discovered difficult. Not knowing when or if any of our annual events would return to normal in 2020, or into 2021, I asked the four artists in my close circle if they wanted to take on a project to paint Indiana rivers.

The initial idea was intended to facilitate painting alone and then exhibit the collection 18 months later as a group. It was something we could all do if COVID restrictions continued. We could at least share our paintings among ourselves and feel less isolated. The project began in August 2020 with four of the five artists meeting at an outdoor barbecue to flesh out the approach.

Because Dan Woodson in 1998 formed a group of five artists to paint all 92 counties and exhibit them around Indiana, and I had just finished helping IPAPA put together a traveling exhibition, our group had examples to use as blueprints to guide the process. Both of these traveling exhibitions produced publications: a book and an extended catalog for the latter. We agreed to use Dan’s experience as our guide. Within weeks of proposing a group show before we met, the project had now added a book with all 100 paintings, in case a venue on the tour could not show all 100.

Within a month of the barbecue, the president of the Izaak Walton League of America-Indiana Division wanted to help sponsor some of the costs of the project. He saw what we were doing as a way to bring attention to waterway conservation. We could use art to help communicate conservation.

Since the advent of photography to record our world, many now consider art decorative, even a luxury item. The Roman Catholic Church once used art to communicate the stories of the Bible to a nearly illiterate public. From the time humans first took a charred stick out of the fire in a cave and drew pictures of great hunts and battles and then used colored mineral and animal blood to paint the images in color, art once was essential to communicate in all human cultures.

Empowered to once again be able to use art for a just social cause, the idea of partnering with more conservationists led to even more changes. By October 2020, we decided to include the entire Indiana waterway system, approximately 65,000 miles to record a minimum of 20 Indiana waterways in multiple seasons.

n

The decision to communicate conservation required the addition of writers – Indiana writers. One of the best writers of nonfiction, Susan Neville, turned down a request but suggested Jason Goldsmith, whose writing already featured environmental research. Neville, however, stayed on to write an Indiana Humanities grant and act as an advisor. Another environmental writer, Carson Gerber, joined the essay team.

As time passed, we discovered the third essayist, Dr. Jerry Sweeten. For about 20 years, he was involved in a quest to restore the Eel River and had accumulated a mountain of research about habitat improvements after performing even the smallest changes to water condition. He agreed to share his experience using a memoir form. His essay on the Eel River restoration can be considered a blueprint for how any waterway in the Midwest can be restored, given the community’s willpower to demand action.

Goldsmith’s work as a creative non-fiction writer and Gerber’s background of using reporting techniques as an investigative journalist reflect the wide spectrum we artists have in our own styles of art. The three featured essays differ in their approach to their subject: Sweeten’s is scientific with the qualities of a memoir, Gerber’s is about the history of the Izaak Walton League and the work they do with projects such as Save Our Streams (SOS). Goldsmith’s story of the White River basin provides entertainment, but upon further examination, also communicates the historical struggles of the Indigenous Peoples and African American communities, as well as the forgotten rural communities that our economy tends to not address today.

As with the writers, our founding conversations during the August 2020 barbecue recognized how each artist’s working style and artist medium eventually created very different images of the same waterways. The artwork in this book reflects those differences. It moves from tight, well defined, shapes representing what is there, to looser styles and techniques; ending the book with the almost unreal and abstract simplification of the subjects.

The paintings in the book are divided by artist into sections, which include a description of his unique experience. We are not writers, but each of the artists wanted to share something from the 20-month painting period.

Style, medium and approach determined the order of the artists in the book.

Dan Woodson’s artistic training as a sign painter required the same precise technique we learned in school to “stay within the lines.” But his landscapes resist those lessons and his photographic-like detail recaptures a youthful spirit of creativity.

Dan’s magnificent artwork is considered tighter than that of his brother Tom. His work is representative of the early American landscape painters, taking a more traditional approach – a tree can almost look like a photograph. Tom’s work is freer, looser, and closer to the collective painted marks of the French impressionists. Some of Tom’s artworks have more non-traditional use of color in comparison to his brother.

Curt Stanfield works both in the studio from photographs and color studies, and in plein air (painting outdoors) from what he sees before him. His work progresses by using Alla Prima – also known as wet-into-wet paint – and is generally done in one setting. His work in these pages show a free-flow spirit, rich in color and character, a stream of consciousness that uniquely captures the authenticity of Indiana’s waterways.

The choice of watercolor by John Kelty further loosens the image because the method differs from the oil used by the previous three artists. Watercolor pools pigment, casting different effects, overlapping edges that blur and become misshapen. It is transparent, and the paper’s inherent whiteness causes layered pigments to almost glow.

Lastly, my works in pastel are looser yet. Pastel can be used to create almost photographic effects, but my use of heavily textured surfaces and application methods allow me to dance on the knife’s edge of abstraction. My approach is not to paint the object itself but the air around it, making most of my paintings less representational.

n

Words and art create an exquisite dance here. The beauty of this book is its eclectic mix that communicates the message of conservation. We recognize some might want to see consistency in the writing or art – or both – and might find these shifts jarring. But our goal is to reach as many as possible by showing the beauty and inspiration of our waterways through a variety of creative methods.

Art transforms. It changes how we think about the places in our state where the rivers and streams run through it. The writing and art motivate people to demand action to help restore fishing grounds that will bring tourism back to our struggling rural communities long after presidents once traveled west by train to fish and hunt in Indiana.

Michigan and Wisconsin inland rivers and lakes, because they’ve been well maintained, are the first choice for outdoor recreation. Geographically, Indiana is much the same as these two famous destinations. But to reach the same level of popularity, there is much to do. If we restore our waterways, as was done to the Eel River detailed in Jerry Sweeten’s essay, Indiana’s waterways can once again teem with life.

Indiana’s waterways inspired the cultures of Indigenous peoples, the stories of European settlers, and served as the muse for songwriters, including Hoagy Carmichael and Cole Porter. Let this work inspire others to take action to preserve and restore these resources to their natural wonder.

Acknowledgements

Very special thanks to Juli and John Metzger of The JMetzger Group (JMG), whose patience in editing and designing this book helped our gang of eight through the process of getting ideas, words, images, and of course the 100 paintings, pulled from the ether and onto these pages. Without their expertise, none of this would be possible. We all thank you.

While it is impossible to name the thousands of people who left messages for us artists and writers on social media or those who guided us to locations, gave us directions, encouraged us, and provided a sundry of other small gestures to make all this possible, we must acknowledge the essential yet incomplete cadre who repeatedly aided us all along the way ranging from grant giving to providing significant cash assistance. They are: Indiana Art Commission, Indiana Izaak Walton League of America, Inc. Endowment, Indiana Humanities, Imagine Burgers and Brews, Swope Museum, Fort Wayne Artist Guild, and Dianna Burt, Lindsey Bridge, John Decker, Brad Fields, Linda Galloway, Nancy Ballmann-Goldsmith, Christel Gutelius, Thomas G. Heatherly, Phyllis Hughes, John Kelty, Betty Knapp, Barb Knuckles, Anne and Donn Larrison, Kim Linker, Kevin Ludwig, Ron and Dottie Mack, Heidi Malott, Cathy McCormick, Sandra McGill, Lynelle Mellady, Mary Moore, Lesa Nelson, Victoria Pope, Sarah Young Powers, Steve and Sharon Reiff, Patrick Redmon, Susan and Keith Ring, Donna Shortt, Lorrie Stanfield, Doris Waters, Kim Willhide, and Judy Hoffman Woodson.

With every project this size, there are many actions of immeasurable value and assistance that often are priceless. Some of those acts of kindness and support came from Mark Ruschman and the staff at the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites; Amy Schreiber and staff of the Fort Wayne Museum of Art; Linda Volz and the volunteers of the Indiana Hoosier Salon of New Harmony; Darin Lawson and Wickliff Auctioneers; Art Nature Consortium, Eco Systems Connections Institute, and from Jim Buiter, Brent Cleek, Keith Halper, Carol Strock Wasson, and Jeff Baumgartner.

To those we are unable to list, we extend our deepest and most sincere thanks, nonetheless. You know who you are.

Juli Metzger is a journalist, journalism educator and entrepreneur.

Her earliest childhood memory is with her father, fishing at the water’s edge. He was an outdoorsman, as long as it meant fishing.

After a 30-year career in the newspaper industry, Metzger joined the faculty of Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, where she is Associate Lecturer Honorata at the School of Journalism and Strategic Communication.

She and her husband, John, operate The JMetzger Group, a boutique content marketing company specializing in niche publications, public relations, and strategic communications.

Words have meant everything to me. They give voice to those who cannot speak up or speak out. But any good writer knows a picture is worth a thousand words. I am privileged to play a supporting role to those who did the real work in this project: the artists and the essayists.

“Indiana Waterways: The Art of Conservation” is a glimpse into how far we’ve come, but more importantly, what remains at stake and the work yet to be done to preserve Indiana’s waterways for those who will write about them in the next generation.

Introduction

Historians may remark about the irony of how one catastrophic event gave the clarity to chronicle another.

A sudden, hidden, odorless agent – the COVID-19 virus – would attack millions of vulnerable immune systems in rapid-fire succession over just two years while a band of Hoosier artists – using the global lockdown – painted with purpose to illustrate Indiana’s slow erosion of its waterways, in plain sight for decades.

It is at this intersection of pandemic-induced free time that art and conservation meet. This book gives voice and visual representations to what’s at stake if we look just beyond the natural wonder in the paintings, and address Indiana’s suffering but salvageable waterways. The exquisite work on the following pages omit the litter and debris artists found, obscuring the realities of continued inattention.

Besides essays, artists share their personal experiences of wading through chest-high waters or flying drones to reach the agriculture pressing against riparian spaces to document Indiana’s rivers and streams. They appealed to private landowners for access to the public waterways.

What the Indiana artists found was nothing short of neglect. Indiana’s fragile waterways – today, poisoned more by agricultural runoff rather than raw sewage and industrial waste – still teeter on the edge of a calamitous cliff. Today, rivers are no longer aflame and the pollution is more subtle yet equally damaging.

We could pull away from disaster or fall headfirst, depending upon the path we choose. Our essayists write of restoration and hope. We all have a role to play and can take steps to slow and even amend sins of the past.

COVID-19 brought the world to its knees. By May 2022, just as this project entered its final stages, the World Health Organization reported that 6.25 million had died because of it. Yet the global disruption caused by the threatening virus brought about several positive effects on which this artistic project is based – the environment. More specifically, water. Due to restricted movement and a significant slowdown of social and economic activities, air quality improved in many cities with a reduction in water pollution in different parts of the world.

Indeed, the climate received a much needed respite during the pandemic.

While most retreated indoors with minimal contact, these five Indiana artists, craving countryside, and their craft, were drawn to the waterways and inspired by the pandemic to use their found time wisely. They emerged from their homes and traveled with easels and brush and each would create 20 paintings over a 20-month period.

This beautiful book includes spectacular original images – representing 100 paintings of waterways throughout Indiana – that are accompanied by essays describing the environmental pressure faced by these natural wonders. Indiana Waterways essayists explain conservation efforts of groups like the Indiana Izaak Walton League of America, an organization created to preserve and maintain the nation’s natural fishing and hunting resources.

Before we can hope to secure the life of Indiana’s fragile ecosystem, it first will take an awakening. Just as there is a cost to fix what is broken. There is an even greater cost to do nothing.

Essayist Dr. Jerry Sweeten, a biology professor emeritus at Manchester University, so eloquently expresses it this way:

“It takes money to restore broken natural systems like the Eel River basin, but we struggle to understand the true costs and negative externalities from our human endeavors as it relates to clean water on a large scale. There are many reasons why it is plausible to have productive and profitable human endeavors across the watershed and a clean and healthy Eel River. Adequate funding for ecological restoration is our largest challenge. Period.”

Indiana environmental journalist Carson Gerber gives perspective of where the state has been and where it should be headed. He writes:

“Since the Izaak Walton League of America was founded 100 years ago, Indiana’s water quality has vastly improved. Fewer rivers are clogged with pollution and debris due to the EPA and IDEM actively enforcing clean-water laws and fining those who violate them. Today, most Hoosiers don’t give a thought to what’s in their drinking water. But water pollution hasn’t gone away. It’s simply morphed into something more subtle and less conspicuous than the burning rivers and oil-soaked beaches of the 1960s.”

n

An educational component accompanied this book with the artists making a series of presentations to community libraries, in classrooms and at museums. The paintings were displayed at the Indiana State Museum and Historical Sites, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, and other art galleries.

“Indiana Waterways: The Art of Conservation” is a call to action. It reminds us that the ecological health of our rivers, streams and tributaries – big and small – remains in jeopardy.

If art is the gateway to the next generation of conservationists, this project gives a roadmap to the work – and the payoff – that could lie just ahead.

Juli MetzgerCarson Gerber is a journalist who has worked in Indiana and Ohio for more than a decade reporting on local topics and the environmental impact industries have on Indiana communities.

In 2019, he and a reporting team won the Associated Press’ top newswriting award in Indiana for an investigative series on Howard County’s opioid epidemic.

Gerber, a canoeing enthusiast, paddled the entire length of the Wabash River over a 10-year period.

Nearly 75 percent of Indiana waterways have been found to be unsafe for human contact. As Hoosiers, are we comfortable with the fact that we could face health consequences from simply taking a dip in our favorite river or stream?.

Photo: Kelly LaffertyGerber. Essay: Carson GerberIndiana playing catch up in conservation efforts

The Grand Calumet River only takes a short, 13-mile jaunt west from Gary before it empties into Lake Michigan through the Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal. But that short stretch of stream carries some of the most polluted water in the United States.

Today, the river has been designated as a “Great Lakes Areas of Concern” under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement due in part to its fish consumption restrictions, beach closings and fish and animal deformities.

The river’s pollution reached its pinnacle in the mid-20th century, with steel mills, oil refineries and other industrial factories flooding the waterway with millions of cubic feet of toxic sludge.1 The river’s vibrant fish population of carp, northern pike, bluegill and yellow perch virtually disappeared. Those that did survive were likely to have deformities, eroded fins, lesions and tumors.2

It was the same story for lakes and rivers around the nation. In 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught fire for the 13th time after decades of oil and debris buildup in the waterway. It wasn’t the largest or most devastating fire on the river, but it captured the attention of the nation after Time magazine did an exposé on the incident.3

Suddenly, the country’s eye turned toward the decades of unnoticed pollution dumping into rivers and streams, especially those in highly industrial areas like the Grand Calumet River in Gary. In response, Congress took one of its most bold and sweeping steps toward conservation by passing the National Environmental Policy Act. It was signed into law on Jan. 1, 1970, and helped establish the Environmental Protection Agency that same year.4

But one conservation group didn’t want the government to be the only ones keeping an eye on the health of the nation’s waterways. For the Izaak Walton League of America, protecting rivers and streams was a duty of all its members and to all those who called America home.

Congress passed its environmental policy in 1969. That same year, the Izaak Walton League started Save Our Streams – the only nationwide program training volunteers to protect waterways from pollution and collect water-quality data that would be some of the first citizen-provided information to the EPA that it considered scientifically valid.5

A Century of Conservation

The Izaak Walton League, one of the oldest conservation groups in the U.S., has spent the last 100 years fighting to protect the nation’s waterways and sounding the alarm on the environmental devastation happening across America. In fact, deteriorating water quality in lakes and rivers was the issue that brought 54 sportsmen to Chicago on Jan. 14, 1922, who founded the group to protect the top fishing streams and rivers that were under threat from industrial pollution.6

They named their new conservation group after Izaak Walton, the 17th century English author of “The Compleat Angler,” the literary classic that praised the beauty of streams of Walton’s homeland and documents the author’s adventures teaching a novice fisherman about the sport – and his philosophy about environmental stewardship.

From the beginning, the Izaak Walton League made preserving America’s rivers and streams its top priority. In 1927, zoologist and League member Henry Ward suggested to President Calvin Coolidge that the group could prepare a nationwide water quality survey.

Coolidge commissioned the League to send questionnaires to health officials in all 48 states. It was the first national survey of its kind, and the results showed that sewage was responsible for 75 percent of the nation’s water pollution because most sewer systems were not yet connected to any treatment facility. The study also determined the Midwest, Northeast and California had the most polluted waterways.7

In response to the findings, seven states rapidly passed laws to address water pollution. The League used that momentum to make a national push over the next decade to build sewage treatment plants in every community. Local chapters took up the cause, which led to new treatment facilities in towns and cities around the U.S.8

The League’s emphasis on first-person observation and hands-on advocacy led chapters in Maryland to start a program called Save Our Streams. They modeled it after that state’s adopt-ahighway program, but instead of roads, members adopted a waterway. Volunteers reported water pollution, removed trash and debris and educated the public about preventing pollution.9

In 1972, thanks in part to efforts from the League, Congress approved the Clean Water Act, which allowed the EPA to implement pollution control programs and enforce policies that made it illegal to discharge any pollutant from a point source unless a permit was obtained. 10

The Izaak Walton League celebrated the sweeping policy changes brought on by the legislation and hailed the Clean Water Act as one of their crowning conservation achievements. But the group knew it could not depend only on the EPA to keep the nation’s rivers safe. In 1973, the League adopted and developed national guidelines for Save Our Streams, and asked every chapter and member to adopt and clean up a local waterway.

In 1975, to get the word out about the new program, the League’s new Save Our Streams Director Dave Whitney jumped aboard a converted motorhome dubbed the Water Wagon and traveled to every state in the contiguous U.S. His message was simple. “[Water is] vital to our lives. You can’t make any more of this stuff,” Whitney said.11

In the mid-1980s, the group partnered with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to develop a volunteer monitoring protocol to gauge a stream’s health based on the presence of insects and other aquatic life. In 1990, the EPA approved the League’s approach to ensuring scientifically valid data, making it one of the first such quality assurance plans to be approved by the agency.12

Indiana Gets Rolling

Save Our Streams gradually picked up steam in chapters across the nation, but it took the Indiana division longer than that to fully embrace the power of the program.

After it launched, local chapters continued to work independently on their own water-quality programs. In the northcentral Indiana town of Argos, members started a fish hatchery program and donated their first fish to the state’s hatchery system.13 Others organized annual river cleanups. Chapters in northwest Indiana continued to work to restore wetlands around the Kankakee River, which was once home to the largest inland marsh in the U.S. before it was nearly all destroyed and turned into farm ground.14

Some chapters eventually did take up the Save Our Streams program, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that state leaders made a concerted push to adopt the program across all of Indiana. Organizers called a meeting and appointed a committee chairman at each of the state’s 28 chapters. Then they sent off volunteers to start teaching at schools and youth programs in their region.15

One project guide taught students about watersheds, pollution sources and stream ecology, and then helped them create their own science projects monitoring a river’s biology and water quality. Another Save Our Streams booklet taught students how to do “critter counts” to identify the larvae of beetles, mayflies, worms and other creatures to determine a stream’s health.16 At one point, Save Our Streams was taught in every summer school class in the Indianapolis Public Schools district.17

A discarded refrigerator lodged on a log in Mill Creek near Cataract Falls in west central Indiana’s Owen County.

Indiana’s League Division had consolidated the program, but that initial push gradually fizzled out in some chapters as they worked on their own projects or put more emphasis on the recreational activities, such as organizing skeet shooting and fishing tournaments.

Since 2019, the national League and the state division have sustained a prolonged push to reinvigorate the program. In 2021, the Indiana division acquired 12 professional-grade kits to test the water quality in lakes and rivers around the state. The kits cost several hundred dollars and include different kinds of nets, dip-strips for chemical testing, and reference materials.18

All that information can now be found at a national database created by the League called the Clean Water Hub, a first-of-its kind resource for water quality information from around the U.S.19 Members can submit current or historic data from testing kits, and all the information is publicly available using an interactive online map. In Indiana, more than 40 testing sites have been logged, most of which are along rivers and ditches in the Fort Wayne region.20

Data provided on the map through the Save Our Streams test kits plays a vital role in monitoring the state’s waterways. The Indiana Department of Environmental Management only does site-specific testing on a fraction of the state’s 62,550 miles of rivers and streams. Most water quality data used by the agency is derived from statistical calculations.21 Now, with more site-specific data provided by volunteers to supplement IDEM’s testing, officials can more accurately shape Indiana’s water quality programs and initiatives.

Adapting to a New Century

Since the Izaak Walton League of America was founded 100 years ago, Indiana’s water quality has vastly improved. Fewer rivers are clogged with pollution and debris due to the EPA and IDEM actively enforcing clean water laws and fining those who violate them. Today, most Hoosiers don’t give a thought to what’s in their drinking water.

But water pollution hasn’t gone away. It’s simply morphed into something more subtle and less conspicuous than the burning rivers and oil-soaked beaches of the 1960s.

Today’s threat is the runoff from tens of millions of acres of farms, suburban lawns and parking lots in cities across America. And a new threat means a new approach to the Save Our Streams program. “Success today – and in the future – will be defined by detecting and tackling this 21st century threat,” said Samantha Briggs, the League’s Clean Water Program director.22

In Indiana, one of the most pressing issues is curbing runoff from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and fields that eventually flows into the Mississippi River.23 That runoff is full of nutrients that suck oxygen out of water. Enough of it has now ended up in the Gulf of Mexico to create a 1.4 million acre environmental disaster called the dead zone that kills nearly all aquatic life there, and Indiana contributes about 11 percent of that fish-killing runoff.24

Where exactly does that runoff come from in Indiana? That’s what programs like Save Our Streams can help determine through volunteer testing and monitoring. “If most streams in America are not regularly monitored, there is no way to detect these drastic pollution events,” Briggs said. “In other words, you don’t know what you don’t know.”25

The Indiana Division also is getting back to the program’s educational roots teaching kids about what clean water actually means. Jim Sweeney, a member of the Spring Lake Chapter and a national executive board member, has taken a unique approach by participating in Canoemobile events each year to show students the magic of macroinvertebrates.26 “The kids just eat that stuff up when you show them all those bugs,” Sweeney said. “It’s a good learning tool.”27

The Izaak Walton League has spent the last century fighting and advocating for clean water, and the organization shows no signs of stopping. New initiatives like the Salt Watch Program are getting members and everyday citizens to advocate for less road salt, which can create unhealthy water conditions for aquatic animals and end up in drinking water.28 The League also has created a new Creek Critter App to help kids and families identify the bugs and other creatures that indicate a healthy stream.

It all stems from the vision laid out by the League’s founders 100 years ago to protect the nation’s water, woods and wildlife. That vision included advocating for legislative changes, connecting Americans to the outdoors and providing citizens with programs like Save Our Streams that turns data into action.

Indiana’s Save Our Streams Director Edward Wisinski said both the national League and the Indiana Division continue to implement that vision and advocate for changes to protect local waterways over the next century. After all, if conservation groups like the Izaak Walton League don’t continue to raise the alarm, who will?

“We’re trying to bring that to the public, not in a radical way, but in a common-sense way,” he said. “It’s a never-ending process. Just when we think we’ve crossed the bridge, so to say, we come up against another flooded stream.”29

1 https://earth5r.org/11408-2/

2 http://www.csu.edu/cerc/researchreports/documents/PastPresentPotentialFishAssemblagesGrandCalumetRiverIN HarborCanal2000.pdf

3 https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Cuyahoga_River_Fire

4 Ibid.

5 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2019-issue-1/50-years-of-save-ourstreams-volunteer-stream-monitoring-is-as-critical-today-as-ever

6 https://www.iwla.org/about/about-us/founders-of-the-izaak-walton-league

7 https://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/key_docs/paavola-12-4.pdf

8 https://www.iwla.org/100years/history/milestones

9 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2019-issue-1/50-years-of-save-ourstreams-volunteer-stream-monitoring-is-as-critical-today-as-ever

10 https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act#:~:text=The%20basis%20of%20the%20 CWA,name%20with%20amendments%20in%201972.

11 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2019-issue-1/50-years-of-save-ourstreams-volunteer-stream-monitoring-is-as-critical-today-as-ever

12 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2019-issue-1/50-years-of-save-ourstreams-volunteer-stream-monitoring-is-as-critical-today-as-ever

13 Interview with Edward Wisinski, Indiana’s Save Our Streams chairman and a past state president. Jan. 6, 2022 14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Save Our Streams: Monitor’s Guide to Aquatic Macroinvertebrates. Loren Larkin Kellogg. Published 1992

17 Interview with Edward Wisinski, Indiana’s Save Our Streams chairman and a past state president. Jan. 6, 2022

18 Interview with Jim Sweeney, Izaak Walton League Executive Board Member. Jan. 7, 2022 19 https://www.iwla.org/water/stream-monitoring 20 https://www.cleanwaterhub.org/community

21 https://mywaterway.epa.gov/state/IN/water-quality-overview

22 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2020-issue-2/clean-water-corner-defin ing-(and-redefining)-success-with-save-our-streams

23 Interview with Jim Sweeney, Izaak Walton League Executive Board Member. Jan. 7, 2022 24 https://www.wfyi.org/news/articles/conservation-practices-have-effect-from-midwest-all-the-way-to-gulf-of-mexico 25 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2020-issue-2/clean-water-corner-defin ing-(and-redefining)-success-with-save-our-streams

26 https://www.iwla.org/publications/outdoor-america/articles/outdoor-america-2020-issue-2/clean-water-corner-defin ing-(and-redefining)-success-with-save-our-streams

27 Interview with Jim Sweeney, Izaak Walton League Executive Board Member. Jan. 7, 2022 28 https://www.iwla.org/water/stream-monitoring/winter-salt-watch

29 Interview with Edward Wisinski, Indiana’s Save Our Streams chairman and a past state president. Jan. 6, 2022

Dr. Jerry Sweeten taught biology at Manchester University (formerly Manchester College), where he is Professor Emeritus of Biology and Environmental Studies. He owns and operates the Ecosystems Connections Institute in Denver, Indiana.

His work centers on the ecological systems and restoration of waterway systems with a primary focus on the Eel River Basin restoration.

In restoring the Eel River, we restore ourselves, and we offer reconciliation to all creatures large or small who have had no voice. Our collective and humble success will be judged, not on the words that tell this story, but rather what the river tells us. I hope we listen well.

Essay:

Dr. Jerry SweetenRestoration of the Eel River of Northern Indiana: A Journey of Reconciliation with Nature

If ever there was a molecular underdog, it would have to be water. Water is truly a molecular miracle that most assume will be around in sufficient quantities and quality. But this assumption can be a painful lesson when there are miscalculated expectations or exploitations.

Made of one part oxygen and two parts hydrogen, water is a simple molecule by the standards of chemistry, but water drives an extraordinary number of complex natural systems and is literally the stuff of life and beyond. It is, by far, the most abundant liquid on Earth and makes up most of living matter. In fact, human bodies are more than half water.

Water dissolves all kinds of other molecules, becomes less dense when it freezes, which allows ice to float rather than sink, moderates the Earth’s temperature, and is sticky, which allows only the most anatomically prepared to walk on water. Watch water striders skim across the surface of a lake or stream. It is a mystifying achievement.

Water is simply in a league of its own. This may be shocking news, but there is no new water being made. Water is constantly being recycled from liquid to gas through what scientists call the hydrologic cycle or simply the water cycle. Conceptually the water cycle is quite simple, but the details are complex.

Stock photo.

A water strider is anatomically enabled to walk on water.

When one drinks a glass of water, there is no way of knowing where these water molecules have been or where they are headed. Perhaps the water molecules in this glass were once in the ocean or perhaps a lake, or perhaps part of a plant or animal.

Let your mind wander and it may be a bit scary. Imagine being a water molecule on this cyclical journey. For some, this molecular journey will move quickly based on nature’s time scale, but it is possible to be stuck for a very long time in a glacier, underground, or in the depths of the ocean. Regardless, this process has been occurring well before humans showed up on the Earthly scene and will continue with or without humans.

Unless otherwise noted, all images accompanying this essay are courtesy of Ecosystems Connections Institute.

The Eel River and the Human Condition: A Sense of Place

It is well known most of the water on Earth is salty and found in the oceans (97 percent), but only a tiny fraction is found in freshwater streams, less than 0.003 percent. This tiny fraction of water in streams embarks on a journey through unique physical, biological, and geological ancient natural systems that harbor great diversity of life, and which have no voice in the matter.

Awareness and understanding of this complex and intricate water journey bring together the living and nonliving world and is a pointed example of opportunities for restoration and reconciliation with nature. Nowhere are these interdependent salient mysteries of nature more evident than along the ecological restoration journey of the Eel River in northern Indiana.

All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

Ecclesiastes 1:7

There is a rich and vigorous natural and cultural history for the Eel River basin of northern Indiana, but this history is heavily weighted toward the cultural side and very little to none toward the natural history side. There are several excellent Cultural Historic Museums across the basin including North Manchester, Columbia City, Stockdale Mill, and Logansport.

These museums thoroughly capture the good, bad, and ugly of recorded culture history. They record the ebb and flow of Native American scuffles that were often delineated by the Eel River. The Potawatomi were predominantly relegated to the north side of the river and the Miami Indians to the south. Evidence suggests the Potawatomi and Miami Indians often were engaged in territorial scrimmages but there was co-existence for hundreds of years.

Native American cultures came quickly to an end after Europeans arrived on the scene. There was a disregard and dismantling of Native American culture that was unspeakably sad and falls clearly in the bad and ugly categories of our cultural history, and worth exploring with a healthy dose of humility.

n

The Eel River basin, like other streams and lakes in northern Indiana, had their form, shape, and personality created by the last of four great continental glaciers that moved across this part of the world.

The Wisconsin Glacial Stage began between 100,000 and 75,000 years ago and ended about 11,000 years ago. This was a huge glacier and showed no respect for its three glacial predecessors or the

political boundaries that would be drawn in the future by humans. This glacier was driven by a climate considerably colder than our climate today and slowly chugged along, grinding and sorting rocks to all sizes and shapes, creating what we call glacial till – soil.

Evidence of this historic event can be seen where glacial erratics – glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area – have been randomly scattered across the landscape, including in the Eel River.

Many Eel River canoeists have learned all about glacial erratics hidden just below the water surface through experiential learning. The canoe or kayak driving test comes first, followed by the lesson that might include being perched on top of a boulder, ricocheting off to one side or the other, or gathering gear from the water.

Below the till and glacial erratics is a surprising discovery – limestone bedrock – which formed when Indiana was covered by a shallow sea. Some of this ancient limestone is evident in the lower part of the Eel River basin at Logansport where there is a fossilized coral reef. It is a great place to visit and explore marine fossils. The limestone outcroppings are plentiful from near present-day Adamsboro six miles upstream of the Eel River confluence with the Wabash River. The till completely buried the limestone in the upper parts of the basin to depths of well over 100 feet.

Geologists say the Wisconsin Glacier ice was a mile thick where the Eel River basin is now located. Multiple lobes of this great sheet of ice ebbed and flowed roughly northeast to southwest over a very long time, all the while creating landforms seen today that direct the flow of water in the Eel.

Occasionally and randomly huge chunks of ice would break loose from the glacier and create a large depression in the ground that would ultimately fill with water. They are called natural lakes today. These lakes and their surrounding wetlands are scattered across the northern third of Indiana and are important recreational hubs. There are only five natural lakes remaining in the upper part of the Eel basin, and most of the original wetlands have long since been drained by humans.

The Eel River basin was created by two large lobes of ice. The Saginaw lobe dipped to the southwest out of Lake Huron and slid alongside the Erie lobe of ice, which also headed southwest and carved out Lake Erie.

Where these massive ice sheets slid alongside each other, huge undulating mounds of Earth were deposited that extend from just west of Fort Wayne, in a southwest direction to Logansport. Today, these rolling hills are called the Packerton Moraine. A moraine is simply a place where glaciers slowed in their advance or retreated and deposited large mounds of glacial till or piles of soil.

These hills are quite evident by traveling north on Indiana State Road 13 from North Manchester, but the hills associated with the Packerton Moraine can be viewed north of the Eel River at about any location. As water from the melting massive sheets of ice carved a pathway, it bumped into the Packerton Moraine that was positioned northeast to southwest and forced what is now the Eel River to follow in this trajectory.

As all this was happening in glacier time, there was a huge geologic tussle over where water at the top of the basin would flow. As the ice melted, the Earth slowly sprang upward much like a wet sponge responds after wringing out the water.

In this case, there were two options for the water: flow north toward Lake Erie and ultimately to the Atlantic Ocean, or flow southwest to the Wabash River and ultimately to the Gulf of Mexico. This is a true continental divide, albeit not very dramatic and without large mountains to direct our intuition about where the waters should flow.

It was a geologic debate where the Eel River lost part of its real estate at the upper end of the basin to what is now Cedar Creek that flows to the St. Joseph River in Fort Wayne then to the Maumee River that flows into Lake Erie.

The evidence of this battle remains as an expansive flat wetland at the top of the basin just west of Huntertown. Even today, water in this wetland is somewhat challenged as to which way it should flow. Of course, humans have stepped into this debate and imposed will on the water that seemed confused, but not really. Regardless, we do know that gravity is still in charge and the water will always follow this advice.

As the ice sheets continued to recede at different rates, landforms were created. In the case of the Eel River, it had few options except to flow southwest along the Packerton Moraine on the north side of the basin. However, the south side of the basin is very different. Here, the glacier receded at a steady pace and left flat and poorly drained till.

A trip south of the Eel River toward Indianapolis will illustrate this flat landscape we now call the Tipton Till Plain. Often the joke is that the Tipton Till Plain is so flat that one can watch a dog run away for days. Not that any runaway dog would care, the interpretation of this geologic history is recorded in landforms discerned today, but what happened next is largely a mystery.

As the climate became warmer and drier, the Eel River basin was colonized by opportunistic plants and animals, including fishes and mussels. There is no record of these successional changes, only speculation with the understanding that nature does not leave any place void of life for long and

all plants and animals have but one thing in mind: They want to take over the world.

Despite all the brilliant strategies and adaptations, including chemical warfare, nature has evolved plenty of checks and balances on this tribal instinct across the great diversity of life. It is fun and curious to speculate what it may have looked like as the first plants and animals arrived on the scene and colonized the Eel River basin without interference.

n

When Europeans began to colonize the basin in the mid to late 1700s, they would have encountered an expansive forest that stretched across the eastern half of the United States with some of the largest trees on the planet. The forest is now called the Eastern Deciduous Forest. This is simply scientific verbiage for trees that lose leaves in the fall.

This forest was so large and so expansive that it was said a squirrel could travel through the trees from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean and never touch the ground. It would be unimaginably dangerous if a squirrel would attempt such a trip today. It must have seemed like an endless sea of trees.

Trees along the Eel River and across the watershed would have been more than 200 feet tall and eight feet in diameter. Of the 23 million acres (one acre is about the size of one football field) that make up Indiana, about 20 million acres would have been deciduous forests when Europeans arrived.

Today, there are about five million acres of forests in Indiana with about 25 percent of these forests in the northern part of the state. The northern forests have been drastically limited to scattered wood lots separated by cultivated agricultural fields and urban areas.

1620

Old-growth forests in Indiana

In the early 1600s, there were about 20 million acres of decidous forests, as respresented by the dark green on these maps.

1850

By the mid1920s, almost all of the forests have been had been harvested. Today, there are about five million acres of old-growth forests remaining in the state.

1926

By the early 1900s, most of the forests were cleared across the entire state, including the forests across the Eel River basin. While these expansive landscape level changes allowed humans to become the dominant species, there also were ecological losers and ecological winners.

By the middle 1800s species like black bear, fishers, wolverines, lynx, elk, and American bison were extirpated from Indiana. By the early 1900s, gray wolves, porcupine, river otter, beaver, and whitetail deer were gone.

Passenger pigeons effectively were gone by 1900. Early accounts speak of flocks of passenger pigeons so large they would block the sun for an entire day or more. Passenger pigeons are now extinct, but at one time they were thought to be the most abundant animal with a backbone on Earth. The last passenger pigeon died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Her human name was Martha. It must have died of a broken heart.

One can only now imagine a parakeet native to Indiana. It’s true. Carolina parakeets, also now extinct, could be found within the boundaries of what is now Indiana. It is unlikely anyone knows when the last Carolina parakeet died, but the Earth surely must have felt the pain.

Both passenger pigeons and Carolina parakeets are two species of birds that were collateral damage of a changing world, and they were unable to adapt. We even depict this era of European settlement of Indiana and these catastrophic environmental changes on the State Seal that shows a fellow chopping down a tree with an ax while an American bison exits the state, and the sun is setting in the background.

Only professional logic can make an educated guess of how the Eel River basin changed after clearing the great forests and dictating when and where water must be allowed or not allowed. Only from the distance of time and relying on less than scientific evidence, one can imagine what it was like across the basin.

In the 1970 book, “Travel Accounts of Indiana 1679-1961,” author S.S. McCord wrote about Hugh McCulloch, a member of Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet, who began his banking career as the President of the Bank of Indiana while the state was still a vast wilderness:

In 1833, McCulloch stood at the Wabash River near the confluence with the Eel. He wrote: “I followed an Indian trail that led along the banks of the Wabash, which had not been deprived of any of their natural beauty by either freshets or the ax of the settler. The river was bankfull [referring to water at the top of the riverbank just before flooding]. Its water was clear, and as it sparkled in the sunlight or reflected the branches of the trees which hung over it, I thought it was more beautiful than even the Ohio…”

It is highly unlikely the water of the Eel River or Wabash River will ever be bankfull with crystal clear water.

One of the more mysterious and lesser-known animals in streams and lakes are freshwater mussels. The Eel was no exception and harbored a vibrant population of freshwater mussels. There are undocumented accounts of so many mussels in the Eel that the shells were cooked to make lime and the meat consumed as food. Today, freshwater mussels are among the most imperiled animals on Earth. Many species in the Eel are hanging on by a thread.

Fish, too, were exceedingly abundant in the Eel with 100 species. As “progress” marched along from the 19th century through the early 20th century, the Eel River, along with many other streams across Indiana, were viewed as a source of waterpower or as a place to dump refuse and unregulated waste. Tributaries that fed the river were ditched and wetlands drained. The water cycle has been forever altered.

The first dam built in the Eel River was constructed at Logansport and commissioned by General John Tipton in 1832. Eventually, there would be 14 low-head dams in the Eel River with most built between about 1850 to the early 1900s. These dams stretched from Collamer (River Mile 74) to Logansport (River Mile 1) and ranged in height from five- to 10-feet tall. Dams were constructed to provide waterpower to grind grain, run sawmills, support breweries, provide drinking water, and even early versions of electrical generation.

As the economy of running these mills and industrial endeavors changed, all were eventually abandoned. Only one working mill in the basin remains at Stockdale (River Mile 35). The mill is fully restored and functional and worth the time for a tour. The river is a mighty force and by the beginning of the 21st century only seven of the original 14 dams remained.

Most of the earliest dams were built as wood-crib dams and later capped with concrete or replaced with concrete dams. The wood-crib dams without concrete caps were consumed quickly by the river, but the concrete dams have persisted even when the mills had been reclaimed by nature.

With a thumbnail sketch of this time when Europeans colonized the basin, it is clear the Eel River experienced serious ecological and cultural trauma. What is not known is the degree of this trauma apart from inference from anecdotal evidence. There is no scientific data, but only glimpses and limited insights.

“Some of the communities upstream discharged sewage without treatment. In 1965, this writer piloted a youth canoe camp for the Indiana North Evangelical United Brethren Church. Foul conditions were much more evident at that time. It seemed every farmer had a hillside overlooking the river where the family trash was dumped. Several dead livestock carcasses lay at the water’s edge. There was a massive fish kill below North Manchester.”

– Jay Taylor, North Manchester, Indiana, as published by the North Manchester Center for History

After reading this account for the first, second, and third times, it is humbling to ponder how even some of the most resilient plants and animals survived, let alone plants and animals that must have been resilience compromised. It is an unspeakably sad part of Indiana history. Fortunately, there has been some incidental progress relative to the quality and integrity of the Eel River, as well as other streams. It is hard to imagine a recurrence today of what Jay Taylor experienced in 1965.

With the passage of clean water legislation, industry no longer indiscriminately dumps waste into the river and municipalities are required to treat municipal waste before returning the water to the river. These wastewater treatment plants have eliminated, mostly, direct discharge of human waste into the river with two caveats.

The first is combined sewer overflows and the second is high levels of phosphorus in the water being returned to the river. In most towns and cities, the storm drains are combined with the sewer drains from homes and ultimately flow to the wastewater treatment plant. If rainfall exceeds the capacity of a wastewater treatment plant, overflow valves open and raw sewage and excess rainwater flow directly into the river. There are large warning signs at every combined sewer discharge point.

This is an old approach to water quality called, “dilution is the solution to pollution.” It is bewildering to think it has taken decades for the wheels of bureaucracy to have turned enough that towns are required to either eliminate or significantly reduce the frequency of when raw sewage can or will be discharged into a stream. There will be a day when raw sewage will never be discharged into streams, hopefully soon.

The second caveat to this story is the removal of an unassuming molecule called phosphorus. It may be a little-known fact outside the circle of limnologists – scientists who study freshwater lakes and streams – but human waste (poop) is loaded with phosphorus.

While every living organism needs phosphorus for multiple biological processes, there can always be too much of a good thing. In this case, excess phosphorus is a pass through. Phosphorus and water quality go hand in hand. Too much phosphorus in a lake, stream, or the ocean causes harmful algal

blooms, reduces oxygen in the water, turns the water a “pea soup” green color, and in some cases the algae can be of the toxic variety.

It only takes 30 parts per billion of phosphorus to cause this cascade of ecological change. This is equivalent to 30 cubes of sugar in an Olympic-sized swimming pool or 30 seconds in 32 years of phosphorus in a lake to cause problems.

There is no shortage of good examples of phosphorus pollution, including nearly every lake in northern Indiana, the western basin of Lake Erie, and even the confluence of the Mississippi River with the Gulf of Mexico that results in a dead area called a hypoxic zone. Other high-profile examples include toxic red tides along the west and east coast of Florida.

Removal of phosphorus from wastewater is slowly improving. While elimination of combined sewer overflows and removal of phosphorus from wastewater cost money, these are worthy investments in a common good for a clean stream or lake that will bring extraordinary ecological value and value to the human community.

The synergistic effects of pollutants sent indiscriminately into and down the Eel River over the past decades may never be understood, but at least there is progress on the municipal and industrial side of the ledger. It is good to know people care and progress is headed in a good trajectory.

The Eel River and small streams across the watershed have been dammed, ditched, drained, and served as a repository for unimaginable waste. More than 80 percent of the forests have been cleared from the Eel River basin and cultivated agriculture is the predominant land use. There have been and continue to be unintended consequences of human endeavors which contribute to the ecological trauma of the Eel River.

For a restoration limnologist, it is well known anytime a natural system has been altered to this degree there will be an ecological response. It may not be the response anyone expected or anticipated, but nonetheless the response is as predictable as gravity that makes water run downhill or any other natural physical law in the universe. There is a choice.

Our collective obligation as scientists is to understand and explain the salient ecological gears and other cogs that make a natural system like the Eel River function. Society must offer and embrace pragmatic solutions for renewal and reconciliation for a clean and healthy stream for humans and for all of those who have no voice in the matter. Restoration of the Eel River is a remarkable journey full of unanticipated twists and turns, but the Eel River is without question better today than it has been in decades. This journey is not complete and perhaps never will be, but it is one worthy for future generations to contemplate and engage.

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. Ecologists must either harden their shells and make believe the consequences of science are none of their business, or they must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.”

– Aldo Leopold, in his 1949 book, “A Sand County Almanac”

The Eel River Today: A Journey of Science, Hope, and Reconciliation

As a city kid growing up in the north end of Kokomo, Indiana, frequent vacations to a small fishing cabin on Bruce Lake was nothing short of living in the wilderness albeit only 50 miles from home and a few weeks each year. Bruce Lake is a shallow 245-acre glacial lake in Pulaski and Fulton counties in Indiana.

Looking in the rearview mirror of life provides context to experiences at Bruce Lake as fertile soil for the development of a life journey of this writer as a limnologist. Rachel Carson, American biologist and author of the influential 1962 conservation book “Silent Spring,” wrote:

“A child’s world is fresh and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength. If a child is to keep alive their inborn sense of wonder without any such gift from the fairies, they need the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with them the joy, excitement, and mystery of the world we live in.”

n

Adults, especially mothers, have a sixth sense and vision for life journeys, selflessly making personal sacrifices to spend time nurturing a “sense of wonder.” While never outwardly expressed, my mother knew that my childhood vacations were the origins of a passion for lakes, streams, and fishing.

Bruce Lake was a wilderness with endless adventures and places to explore that were very different from our neighborhood. These adventures are forever deeply embedded, and they became the rock of teaching and scientific philosophies. They became the beginnings of restoring the Eel River.

In September 1971, my parents dropped most of my earthly possessions, including my favorite fishing gear, at the back door of Schwalm Hall at Manchester College. While mathematics suggests this may have been 50 years back, the memory of that day is so vivid that it seems only a few years ago. At the time, my acceptance into Manchester College had to be an error by someone who was tasked to evaluate applicants with strong indicators of success at college. There must have been a mistake.

n

The appeal of Manchester College campus was not academics, but rather the fact it was bordered by the Eel River known for great smallmouth bass fishing. Birthright jobs in Kokomo were factory positions in the automobile industry and young people in the neighborhood rarely ventured off to college. The probability of success of a first-generation college student who was addicted to fishing had to be especially low within the context of a high school teacher’s comment that went something like, “Don’t waste your time going to college. You are not college material.”

Despite this advice, standing at the backdoor of Schwalm Hall was the origin of a professional journey founded on faith and unknown outcomes. College students generally are clueless relative to four years of academia. Hometown peers often inquired about the rationale to attend Manchester College while sacrificing good money at the factory. There were no good answers to these questions, only a journey that was set in motion catching bluegills and chasing frogs at Bruce Lake.

Academia and the college process was like driving in a dense fog. However, the next four years were transformative and served as the foundation for a professional career only remotely imaginable. Four years passed quickly, and in 1975 there was a diploma-in-hand with a biology and environmental studies degree, albeit with an academic record that was mildly average.

This was a small but significant twist in the journey to restoration of the Eel River past skipping classes to go fishing. Rather, the Manchester College journey led to a master’s degree from Ball State University and a Ph.D. in limnology from Purdue University. Who would have “thunk it?”

Perhaps the greatest irony of this journey was a day in 2004 when a teaching position in biology and director of environmental studies at Manchester College was offered and accepted by this same kid from the north end of Kokomo, Indiana.

It was full circle and a giant leap for the Eel River restoration just shy of 30 years of May 1975. This was an awesome opportunity to give back to this special little college, commemorate the dedicated professors who had a vision of expectations and unknown capabilities.

This journey has certainly been convoluted, but at the base were shoulders of those who had the gift, capacity, and vision to see potential in a young fellow chasing frogs and fish at Bruce Lake, and as a first-generation college kid from a factory town set at the backdoor of Schwalm Hall in 1975. The stage was set without any strategic plan, but a life-long journey that led to this small college on the banks of the Eel River.

The motivation was to help young people gain scientific knowledge through research and other forms of experiential learning and where they too may find a life-long affection for understanding the natural systems of the Earth as a scientist and with uncompromising respect and gratitude. The Eel River was a natural and perfect laboratory to nurture their sense of wonder and use the nature of science to teach the science of nature.

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the Earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.”

– Rachel CarsonThis professional limnology training focused on restoration of lakes and streams was set in motion by Dr. Anne Spacie, Purdue University professor and a mentor to me. Dr. Spacie was a brilliant scientist who unceasingly challenged prevailing ecological dogma and instilled the practical question. “What are the management implications of this research?”

To many readers, limnology may be a foreign scientific word that needs to be defined. While a professor at Manchester College, there was a course called limnology. It was a popular class and one that was fun to teach because it had a hefty outdoor element. As a professor, it was part of the job to help students with their academic schedule.

One day a student stopped by my office and asked to join the limnology class. After filling out the correct form for the student to join limnology class, the student asked if limnology was the study of “limbs.” It took a miracle to fight back a giant smile that could have undermined the spirit and zeal of this young biologist to explain that limnology was the study of freshwater streams and lakes.

The student responded with a slow extended, “Hmmm …” followed by the comment that they had no idea there was anyone who studied such things. Education comes in many forms, and we share this common bond of enlightenment from our life journey.

The circle of professional limnologists is quite small and there is a wide range of interests across the profession. Some limnologists focus on tiny details of water systems and others focus on how to fix broken lakes and streams. There are unlimited questions to answer that fit easily into each category, but both depend on time and money. There is simply a shortage of both and especially money.

This is where the Eel River restoration starts to gain some real traction. During a tenure at Manchester College, doors of opportunity opened through partnerships and collaborations that provided money for restoration and for paid student internships and student research opportunities focused on the Eel River.

Without any strategic plan, collaborative work in the Eel became a journey that launched the careers of many students and became the origin of small steps and sometimes large leaps toward restoration of the Eel River ecosystem itself. The work showed respect toward the native cultures that once inhabited the basin, and for the cultural lift that can only come from a healthy stream. Ecological restoration is a team sport.

n

The Eel River is a stream about 100 miles long with a watershed area of 529,968 acres (827 square miles). The Eel begins in Allen County just west of Huntertown, Indiana and joins the Wabash River in Cass County at Logansport. It is a linear stream with only a mild downward slope.

As a frame of reference, the Eel River flows into the Wabash River that flows into the Ohio River that flows into the Mississippi River that flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Quite a journey for a water molecule, but it is only part of the journey. There are plenty of glacial erratic boulders and glacial till soils across the basin and for years the Eel River was considered one of the best smallmouth bass streams in Indiana.

In fact, one of the very early televised fishing shows focused on fishing for Eel River smallmouth bass. The show was called the “Flying Fisherman” and featured Gadabout Gaddis. The fishery waned, but the river has remained a highly popular canoe and kayak stream. The current and predominant land use across the watershed is cultivated agriculture at about 75 percent, with plenty of hogs, dairy cows, and chickens scattered across the basin. Nonpoint source pollution is most prevalent and significantly compromises water quality.

While there are all sorts of compounds, some known and others unknown, sent helter-skelter on their journey to the Gulf of Mexico, the most prevalent are nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment. Sediment – mud in the water – is the largest pollutant by volume in the Eel River as it is in other agricultural streams. The smallest amount of rain added to the stream makes the water look like chocolate milk. There is so much sediment in the river it could easily be called an “aquatic dust bowl.”

It has become painfully clear that most people are accustomed to seeing muddy water in the Eel River and believe the river has always been muddy. It wasn’t always this way, based on the 1833 documented observation of Hugh McCulloch, that day he stood before the Eel near flood stage, but he could still see the rocky bottom.

If all the sediment flowing down the Eel could be made to go airborne, it would undoubtedly change the narrative. Would people then recognize the magnitude of this water quality challenge? Reducing sediment in the Eel is unquestionably the greatest restoration challenge. Since agriculture is the predominant land use across the basin, a conservation target is squarely on its chest. But one fundamental concept central to restoration is that every human endeavor across a watershed bears responsibility for the quality of the stream.

While there are only small towns in the Eel basin including Columbia City, South Whitley,

North Manchester, Roann, Denver, and Logansport, they too contribute. The headwaters and virtually every tributary are farm drainage ditches except for six natural lakes, including Everett Lake, Blue Lake, Round Lake, Cedar Lake, Shriner Lake, and Lukens Lake.

Limnologists would consider the Eel River a highly modified stream system. In 2005, seven of the original 14 low-head dams were still standing and scattered throughout the basin, virtually every tributary was ditched to improve drainage of farm fields, forests cleared, hundreds of thousands of hogs, chickens, and cattle across the basin, combined sewer overflows, and ecological trauma was still evident from days when indiscriminate dumping of waste was the standard operating procedure.

There is and was no debate about the designation that the Eel River was highly modified. Despite all this, there are 61 species of fishes and 26 species of freshwater mussels documented living in the Eel River.

Over the recent past, there have been successful and purposeful reintroductions including white-tailed deer, Eastern wild turkey, river otter, American bald eagle, and clubshell mussels. The successful return of these animals speaks as a testament to restoration ecology, albeit terribly underfunded.

n

From the doorstep of Manchester College in the fall of 1971 as an incoming student, to the doorstep of Manchester College in 2004 as professor of biology and director of environmental studies, was a convoluted pathway to a new gut-wrenching and questionable venture of teaching and research at a beloved institution and on the banks of a broken stream ecosystem.

Imagine teaching students in the very classrooms where some 30 years ago this professional side of this journey began. The classrooms had not changed one bit, and the laboratories all had the same familiar formalin smell that had permanently impregnated every crack and crevice of the building. Frankly, it felt very strange and even surreal.

The stoic professors of the past were no longer teaching. There was one obvious trait that had not changed. Environmental Studies students were reminiscent and predominantly experiential learners and needed to clearly see the relevancy of lecture material to the real world. Relevancy is relative depending on a student and professor perspective.

The operational philosophical platform was understood, and Eel River research emerged as the focal point for adding relevancy to the curriculum. During the 2005 academic year, the science department moved from the old science building to a brand-new building that had been under construction for several years. While the new science building was significantly different, the needs of students remained the same.

To fill this void of experiential learning, a small grant allowed research to begin on the Eel River. Two students worked as summer interns during 2006 to examine nonpoint source pollution relative to smallmouth bass population structure near North Manchester. That research was wildly successful and one of the students was awarded the best research paper at the Indiana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society in 2006. This student was competing against professional scientists and graduate students so maintaining humility was a bit challenged. But a great deal about the spawning habits and spawning success and growth of smallmouth bass relative to the amount of sediment flowing down the river was learned.

The project was funded for a couple more years until a much larger grant was secured from the Indiana Department of Environmental Management and through Federal Clean Water Act Section 319. This grant was for four years and for $1 million. This money, along with a private donation provided a window of opportunity to craft a scientific vision for water quality assessment research that would lead to Eel River restoration initiatives.

The grant provided funding for four student interns in the summer months and the college provided free student housing during the internship. And it enabled continuity in funding over four-years and a two-year extension for a total of six years. This was dynamite in the world of stream restoration. While in nature’s timeframe, six years is less than a blink of an eye, through the eyes of a bureaucracy this was in the realm of geologic time.

A little-known fact, or perhaps a neglected fact, is the cost of scientific endeavors – this general cultural deficit is “conservation sticker shock.” Simply stated, it takes money to fix a broken ecosystem like the Eel River. But money is in short supply for such endeavors.

Through our grants student research teams were able to describe and understand the magnitude of nonpoint source pollution in the Eel River and form new and productive relationships with the agricultural community. The learning was holistic, relevant, and excellent for students to wrestle with the intersection of scientific research and differing cultural worldviews.

The scientific data was frightening, and the Eel River was later listed as one of the top 41 watersheds in the Mississippi River basin as a primary contributor of nutrients and sediment to the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico. YIKES!

It became apparent that a major restoration challenge for the river were seven low-head dams scattered throughout the basin. From upstream to downstream these dams included Collamer, Liberty Mills, North Manchester, Stockdale, Mexico, and two dams at Logansport. To date, only the

river had removed dams from the Eel, but no human had embarked on such an initiative.