THE IDLE CLASS

The Sporting Issue

Dennis McCann Kathy Bay Linda Harding

Jeff Horton Sammy Peters

TABLE of CONTENTS

TELEVISION - 6-7

Beyond Borders: Exploring music across continents with PBS’s City of Songs

WRITING - 8-9

Spa City Secrets: Cassidy Kendall digs deep behind the lore in her new book Secret Hot Springs

ART - 10-11

The Many Hearts of Monica Moore: NWA artist Monica Moore commemorates those lost to COVID-19

ART - 12-14

A Delicate Line Between Abstract + Real: Inside the world of VELESERO

FEATURES - 15-17

The Art of Flow: Exploring yoga as a path to strength, healing + community

FEATURES - 22-23

Hill Bombing: Inside the skating movement nouveau of NWA

FEATURES - 24-25

A Lack of Game: Reflections on hunting by Jonathan Wilkins

FEATURES - 27-30

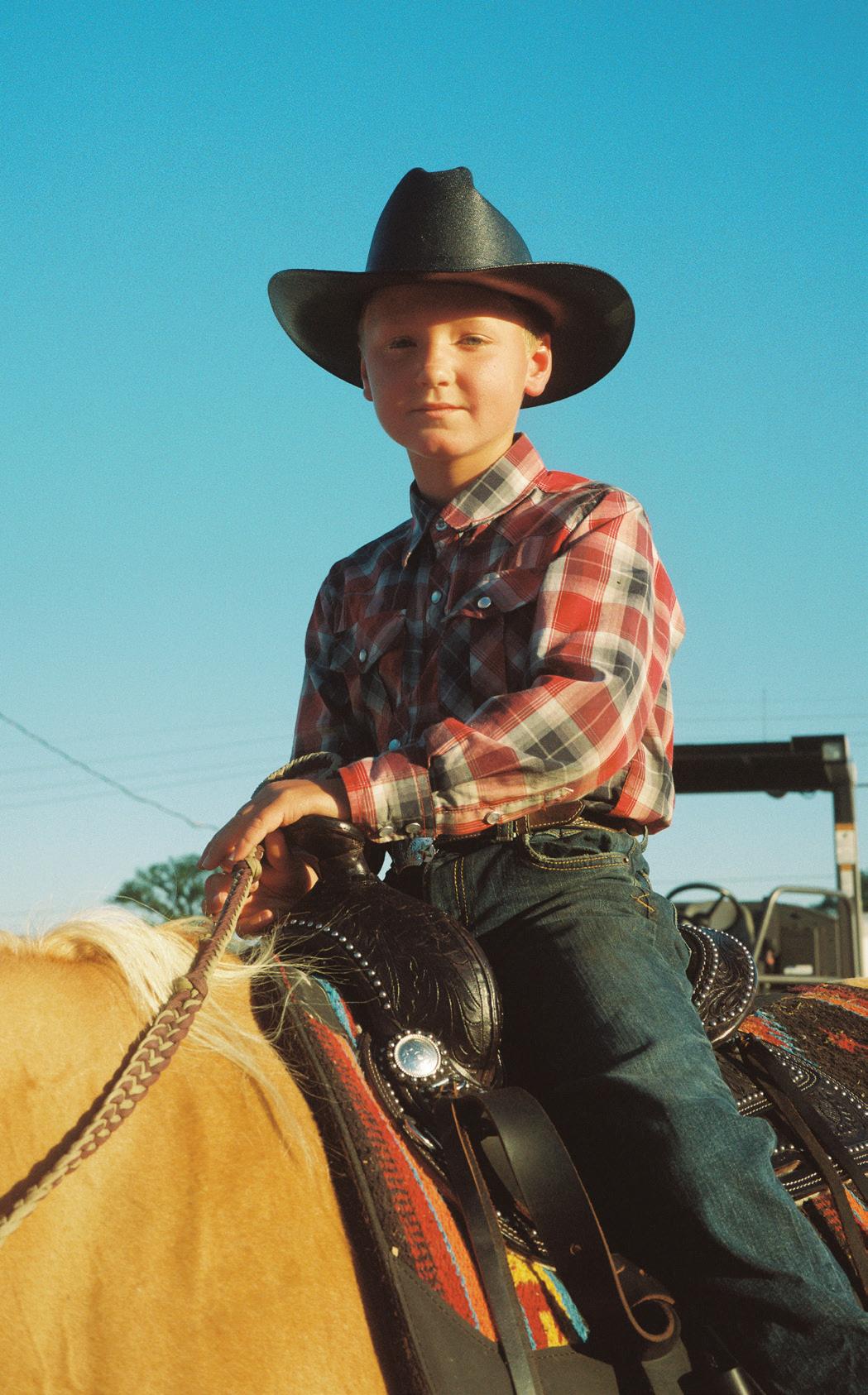

Through the Gate + the Dust: A photo essay on the Rodeo of the Ozarks by Tyler Orsak

THE TEAM

Publisher + Editor

Kody Ford

Assistant Editor

Rachel Farhat

Contributors

Emmy Bennett

Raeden Greer

The Sporting Issue

Anna Culpepper

Sydney Johnson

Chad Maupin

Micky Mercier

Diana Michelle

Marianne Nolley

Tyler Orsak

Shannon Padilla

Robert Sturman

Jonathan Wilkins

Zeb Wilson

Isabella Wisinger

Cover

Mark Jackson

Layout

Kody Ford

BENTONVILLE

KAWS: FAMILY

Open through July 28, 2025

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art crystalbridges.org

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art presents KAWS: FAMILY , a major solo exhibition of work by KAWS, featuring a broad mixture of the artist’s works – drawings, paintings, sculptures, altered advertisements and product collaborations – that examine complex, familiar and astonishingly heartfelt entryways into human emotions.

Since the late 1990s, KAWS has been creating a cast of iconic characters steeped in the American zeitgeist that populate his work. Each with their own distinct personality pulled in part from their creator, these characters have been a constant through line in the artist’s career. The exhibition takes its title and thematic jumping-off point from the sculpture titled FAMILY (2021), which brings together four of the KAWS’ characters posed in the style of a family portrait. As witnessed throughout the show, the relationships between the figures can be complex, familiar, and astonishingly heartfelt entryways into human emotions.

EVENTS STATE around

the

PINE BLUFF

The 2025 Irene Rosenzweig Biennial Juried Exhibition Open Sept. 18, 2025 — Jan. 24, 2026

Reception: Thursday, Sept. 18

The Arts & Science Center for Southeast Arkansas asc701.org

The Arts & Science Center for Southeast Arkansas in Pine Bluff is now accepting entries for the 2025 Irene Rosenzweig Biennial Juried Exhibition. The exhibition is open to artists 18 years or older who reside in Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee or Texas. Accepted art forms include paintings, drawings, original prints, fiber art, ceramics, sculpture, photography, digital works and video.

The prizes awarded are Best in Show, $1,000; first place, $500; second place, $200; three $100 merit awards; and $2,000 available in purchase awards. This year’s juror is multidisciplinary artist, cultural worker and naturalist Eepi Chaad of Houston, Texas.

The deadline to enter is 11:59 p.m. Friday, July 18, 2025. The exhibition opens Thursday, Sept. 18th with a free, public reception from 5 to 7 p.m. and an awards presentation at 6 p.m. The works will be on view in the William H. Kennedy Jr. Gallery through Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026.

Visit artx3.org/rosenzweig for the submission guidelines and entry portal. The cost is $25 per entry, with a maximum of five entries accepted per artist. The exhibition is supported in part by The Arts & Science Center Endowment Fund and the Irene Rosenzweig Endowment Fund.

Organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), KAWS: FAMILY at Crystal Bridges is KAWS’ Arkansas solo exhibition debut. Expanding to fit Crystal Bridges’ exhibition gallery space, this presentation builds on the AGO’s original exhibition to create an experience that is uniquely suited for the museum. The exhibit is curated by Julian Cox, AGO deputy director and chief curator.

FAYETTEVILLE

Fayetteville Movement Fest

July 4-6, 2025

Mount Sequoyah Center fayettevillemovementfestival.com

The 4th annual Fayetteville Movement Festival returns to Mount Sequoyah to celebrate dance, movement, yoga and the arts in Northwest Arkansas featuring artists such as Lela Besom, Heidee Alsdorf, DJ Afrosia, Claudia Aguilar and special guest Emi L. Matsushita from Dallas. This year’s event will kick off with a levels class by Matsushita at 5 pm on Friday followed by a Latin Class + Social led by Aguilar. On Saturday, more than 20 classes will take place throughout the day, including rollerblading, birdwatching, poetry writing, sound bathing and all forms of dance.

“This event is not only healing, transforming, and health benefiting, but it is also a way of living”, says founder Kyndal Saverse. “This event is a way of connecting with ourselves and expressing ourselves, in the safety of community. It highlights values of sovereignty, authenticity, and meaningfulness that may potentially be neglected in our day to day lives.”

Tickets are on sale now and range from day passes to full weekend passes. BIPOC and hardship scholarships will be available. Parents will be able to access the kids ‘spaces for child care needs. No one will be turned away for lack of funds.

Photos Courtesy Dan of Bradica

BEYOND BORDERS

Exploring Music across Continents in PBS’s City of Songs.

WORDS / RAEDEN GREER

I

n bringing the globetrotting, music-focused travel series City of Songs from page to screen, director and producer Mario Troncoso says the production was constantly beset by challenges. According to Troncoso, having done this more than a hundred times (literally, he’s created that many episodes of television) aided him in getting the show to the finish line.

The show follows host Stephanie Hunt—herself a musician—across continents as she explores local music culture in far-flung locales through Anthony Bourdain-reminiscent conversations with the people she meets along the way. Troncoso says the ingenuity of Bourdain’s show wasn’t the format, “They just happened to find a voice that was totally new.” Similarly, he believes Hunt’s unique perspective on the music scenes of cities like Stockholm, Montreal, Seoul and Barcelona—each visited in the show’s first season— will reach a new demographic rarely tapped by public media.

Hunt explores what music means to the cities she visits and not only who but what makes each scene tick. In Montreal, Stephanie discovers that government support plays a crucial role in the vibrancy of the music scene. In Sweden, music staves off the isolation of long winter nights. Season one is bookended by explorations of music in Austin, the eponymous city of songs where Hunt is based as a singer-songwriter.

When asked what drew him to the show, Troncoso admits there is exceeding appeal

in traveling the world and documenting it for work. A perhaps less obvious motivation: he wanted to share this experience with his producing partner on the show, Troy Campbell, and his two young children. Troncoso did similar work on his previous show, Arts in Context, a multiple Emmy award-winning PBS series profiling artists and their art. Troncoso explains that his kids were quite young when he made his last show and that they enjoyed being part of the production. “They were growing up; it was part of their lives. I wanted that for [Campbell] too, for his kids to be able to experience that.”

Beyond season one, Troncoso has big plans for the future of City of Songs, with a planned season two already in the works and ambitions for global offshoots and music festivals—a long-term and encompassing phenomenon.

With the various legal, financial, and logistical challenges that come with getting any film or television project made, seeing an idea gestate from conception to the screen is at once both common and rare. In an entertainment landscape with seemingly endless choices, streaming platforms, short-form, and longform content, and no shortage of ideas, what leads to one show getting made instead of another? The answer, according to Troncoso, is simple: people with a track record of delivering television on time and on budget will get another shot before a newbie with a great idea gets their first chance. In other words, the old adage proves true: it takes 15 years (and a lot of hard work) to make an overnight success.

City of Songs premieres May 15 on PBS.

In City of Songs, host Stephanie Hunt explores how music shapes cultures. The show is written + directed by Mario Troncoso / executive produced + created by Troy Campbell, both NWA residents. (Photos submitted)

SPA CITY SECRETS

A Deep Dive into the Local Lore of Hot Springs

INTERVIEW / KODY FORD

PHOTO / ANNA CULPEPPER

If you think you know Hot Springs, think again. In Secret Hot Springs: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure, journalist and author Cassidy Kendall peels back the polished veneer of Arkansas’s Spa City to reveal a vibrant undercurrent of legends, local lore and untold stories. With an eye for the eccentric and a heart rooted in the community, Kendall uncovers everything from bootlegging tunnels and notorious madams to spy cats and cross-country adventures with a pack pony. It’s a book as wild, resilient and unpredictable as the town itself.

The Idle Class sat down with Kendall to discuss the stories behind the stories, what it means to write a love letter to a city and why Hot Springs continues to surprise even those who think they’ve seen it all.

This is the second book you’ve done about Hot Springs. While researching this, were you recommended stories, or did you start from scratch?

I actually started my journalism career at the local newspaper in Hot Springs right out of college. Since I’m not originally from the area, every bit of local lore fascinated me as a young reporter back in 2019-20. That outsider curiosity pulled me deep into Hot Springs’ stories and ultimately inspired some of the best stories in this book. Hot Springs loves to celebrate its storied past, but I found that some of the most compelling tales were the ones that had gone quiet or been deliberately overlooked. So I started digging. I combed through archives, chased down leads from casual conversations, and listened closely to the stories locals shared — both the famous legends and the ones whispered in the background.

Some discoveries in the book are sobering. For example, a mural of Harriet Tubman once faced a Confederate monument downtown — only to be painted over within two years. (And that very monument stands on the site where two Black men, Gilbert Harris and Will Norman, were lynched in the early 1900s.)

I also uncovered overlooked chapters of history, like the Black bathhouse workers who helped shape the city’s spa legacy but weren’t allowed to enjoy the facilities they kept running.

Other finds made me laugh out loud. Hot Springs has a streak of absurdity that’s hard to beat — like the ostrich farm where tourists once rode ostriches for entertainment, or “Happy Hollow,” a quirky old attraction where people wrestled bears and even gangsters like Al Capone couldn’t resist posing for cheerful photos on donkeys.

Throughout it all, the Garland County Historical Society proved invaluable. I’d walk in looking for one thing and walk out with five new story ideas. I also leaned on the work of late local historians like Mike Dugan, Clay Farrar and Orville Allbritton, each of whom has devoted so much to preserving the town’s authentic past. In the end, the stories I chose for Secret Hot Springs emerged from that mix of meticulous archival research, community conversations and an endless curiosity to understand Hot Springs through both historical facts and personal perspectives.

What were some of the most shocking stories you found?

A few stories absolutely floored me. For instance, cats were trained as spies on Bathhouse Row during the Cold War. I also discovered that Mamie Phipps Clark, the psychologist behind the famous “Doll Test” that helped end school segregation, was born and raised right here in Hot Springs. And perhaps most surprising of all: despite what the local brochures say, Natives didn’t actually use the hot spring water the way we’ve always been led to believe.

Given your deep connections with Hot Springs, how did you balance telling these stories with your personal relationships there?

Honestly, it wasn’t always easy. Most of my friends and colleagues in Hot Springs love the city dearly — and I do too. But this book, while written with love, also challenges some of the cherished stories that shape its identity.

For instance, no, Hernando de Soto wasn’t actually roaming Hot Springs in search of the Fountain of Youth. And despite what that wax museum tour guide might tell you, the gangsters didn’t travel via secret underground tunnels. What I hope people see is that I’m not trying to tear anything down at all — the book is really an honest love letter to the real Hot Springs. One that invites us to tell fuller, truer stories. Stories that include the Black residents who’ve been overlooked by the downtown monument. Stories that give credit to the people who helped build this town but haven’t gotten their due yet.

Why should someone pick up this book?

Because it’s not a PR fluff piece, plain and simple. Sure, there’s plenty of fun and fascinating stuff inside, but this isn’t about marketing Hot Springs — it’s about truly understanding it. I set out to tell the whole truth: the magic, the mystery, the injustices, the quirks, the joy. Hot Springs is such a layered, complex and incredible place. It deserves to be seen in full, and I believe readers deserve that kind of honesty, too. And if you do decide to pick it up, I’d encourage you to preorder it through my site or grab it from a local bookstore instead of Amazon or Walmart — supporting local makes a huge difference.

KENDALLCOMM.COM/BOOKS

The Many Hearts of Monica Moore

WORDS + PHOTO / MICKEY MERCIER

A Lot of People Forgot about the Pandemic. One Artist Didn’t.

Sometimes a piece of folk art goes viral. It captures hearts and imaginations, its reputation spreading by word of mouth and the news. It might become a community collaboration, like quilt-making. Such works of art can even spread spiritual healing after a tragedy. One of those rare phenomena is unfolding in real time in Northwest Arkansas.

The Hearts Project: A COVID-19 Memorial is a mural-size collage work by Fayetteville artist Monica Moore. It honors the approximately 13,000 Arkansans who died from the COVID-19 pandemic. The project comprises 2,700 hand-cut paper hearts, each symbolizing a life lost, arranged in multi-colored geometric patterns. Three sixfoot wooden frames contain the hearts. It’s a striking, massive triptych that could dominate a small gallery.

The backstory of the piece is equally expansive — a testament to collaboration, mourning and hope for the future. During COVID, Moore asked herself, “How can we get our culture to remember this tragedy?” She felt com-

pelled to cut the first of many small paper hearts from magazine pages and newspaper advertising inserts. The various colors and paper textures carry symbolic meaning in her collages, representing different groups affected by the pandemic, such as healthcare staff and public-safety workers who had higher levels of stress, illnesses and suicide.

Another theme is the less-recognized essential workers like store clerks, restaurant staff and home-health aides. Many of them were lower income and minority employees, who kept the service industries functioning and died from the disease in disproportionate numbers.

As The Hearts Project took shape, Moore worked with collaborators, such as art assistant Laura Avila and frame carpenter Joel Doelger. Many volunteers and financial backers assisted, including her husband, UA communications professor emeritus Dr. Thomas S. Frentz.

Five years in the making, The Hearts Project’s first public

showing was in July 2024 at the Fort Smith Regional Art Museum. It moved to the Fayetteville Public Library for six weeks. The collages were also at the Life Styles Blair Center in Springdale as part of an art-therapy program in early 2025.

At the Life Styles Center showing, dozens of derivative heart-themed paintings by the program clients adorn the walls. Some are subdued, others spirited or intense. They evoke the stress of social distancing, the isolation of remote work, and the societal chaos of the pandemic.

Eventually, Moore hopes to grow the project to include more than 13,000 hearts — one for each COVID death in the state. Currently, the project reflects about 20 percent of the deaths. She is forming a nonprofit corporation to raise funds to achieve this goal.

Moore believes that the COVID tragedy should not be allowed to fade from public consciousness, as continued awareness could help prevent another outbreak. “I hope The Hearts Project will bring about change by stimulating conversation and awareness,” she says.

The Hearts Project will have two more shows in Fayetteville this year: at the Likewise co-working space in late spring and at the Local Colors Studio Gallery in the fall.

COVIDHEARTSPROJECT.COM

Sponsored by Simmons Bank

Kenneth Reams: Parking Lot Space THROUGH JULY 26

possible by a

Juried Exhibition

ENTRY DEADLINE: JULY 18

Paintings, original prints, fiber art, ceramics, sculpture, photography, video and digital works. CASH PRIZES AND PURCHASE AWARDS! Enter: artx3.org/rosenzweig

Supported

Made

Kenneth Reams Arts for Justice Grant

A Delicate Line Between ABSTRACT + REAL

WORDS / SYDNEY JOHNSON

Inside the World of VELESERO.

In a quiet pocket of Siloam Springs, just 100 steps from his home, Mark Jackson has built a studio dedicated to the beautiful chaos of creation. Inside, you’ll find more than just light and shadow dancing across panels he handcrafted himself. You’ll find the fizz of imagination meeting discipline, and a story unfolding that walks the tightrope between abstraction and reality.

Jackson has been a photographer since he was 13, and even now, decades later, he still feels a jolt of electricity every time he picks up a camera. “I’m not great with words,” he admits, “so I communicate through art.” His work is infused with quiet intention and a curiosity that rarely sleeps. A single word— START—scribbled on his studio wall, reminds him daily that inspiration comes through the doing. “I always show up. The second I pick up my camera, the creativity kicks in.”

Though he’s worn many hats over a 33-year career, it was only about five years ago that he began devoting himself fully to art. That shift didn’t come alone. His daughter Summer, now his representative, has played a pivotal role in helping define and promote the VELESERO brand. What began with social media help has evolved into a full partnership—one

All images courtesy of VELESERO

rooted in family and creative vision.

“We started reaching out to any and every gallery,” Jackson recalls. “Now, we’re more focused on showrooms and year-round art spaces. It’s grown in the right ways.”

There’s a difference, he explains, between photography created for commerce and photography born of instinct. Commercial work, while still creative, comes with a builtin purpose—a function to fulfill. Art, on the other hand, lives freely. “I’m tired of utility,” he says with a smile. “I want to make pretty things with no utility. Light and friendly, not dark and moody.”

In that spirit, Jackson created VELESERO, a name that sounds like a distant place or a character from a dream. “There are a million Marks,” he laughs. “There’s only one VELESERO.” The name gives him space to explore and share art that doesn’t have to be tied to him personally. It’s a world of its own—a slightly fuzzy, fizzy memory of the future, as he calls it.

Jackson’s collections often explore the quiet echoes of human presence, like in his series Good Party Bad Party, where he captures the aftermath of celebrations: half-eaten cake, empty glasses, disheveled tablescapes. These images aren’t sterile; they’re stories. “They walk a deli-

cate line between the abstract and the real,” he explains. “If everything is spelled out, there’s no fun in that.”

His process is often magical, even to him. Some of his favorite moments happen when images reveal themselves slowly, almost unexpectedly. “That’s the part I love,” he says, “seeing the image develop before my eyes. When something unexpected happens, I’m pleasantly surprised.”

If he could learn from any artist, it would be Chuck Close: “a painter who wouldn’t have become who he was without photography,” and John Singer Sargent, whose mastery of light and human form feels kindred to Jackson’s own explorations.

For Jackson, art isn’t complete until it’s shared. “Selling a piece is the completion of the process,” he says. “It’s the circle of art’s life.” And thanks to Summer, the reach of his work is expanding. Together, they’re building something deeply personal and uniquely VELESERO. In the end, Mark Jackson’s world is one where imagination leads, where each photograph hums with both precision and possibility, and where the blur between fiction and memory is the point, not the problem.

“If everything is spelled out, there’s no fun in that.”

— MARK JACKSON

The Art of Flow

Exploring Yoga as a Path to Strength, Healing & Community

WORDS / RACHEL FARHAT

PHOTOS / DIANA MICHELLE, EMMY BENNETT + ROBERT STURMAN

Yoga is often misunderstood as a fitness trend or a simple sequence of stretches to ease stress. But for many, it’s much more than movement or meditation — it’s a deeply personal and transformative path. Three Arkansas-based yogis will explain yoga as an evolving art form, a wellspring of community, and a source of healing in a world that constantly demands more.

KYN JACKSON – EARTH & ENERGY

For Kyn Jackson, a 22-year-old yoga teacher based in Little Rock, yoga began as an athletic pursuit. “I was originally drawn to it as a way to stay active,” they say. “But the more I studied, the more I realized it was so much more than just movement.” Over time, Kyn discovered that yoga is a system that encompasses mental, emotional, and even ethical well-being. “There are moral guides, instructions on how to eat well, and other resources for keeping the mind and body healthy.”

Especially fascinating to Jackson is yoga’s ability to be both structured and expressive. “The physical practice, asana, can definitely be an art form,” they explain. “There are many yogis who find a personal ‘flow’ and learn how to be creative with their bodies.”

Jackson’s practice is influenced by natural rhythms, particularly the phases of the moon. They structure their classes around these cycles, designing sequences that align with the emotions and energy levels often associated with different lunar phases.

“During new moons, I tend to focus on an empowering practice, making you feel strong, and awakening energy in the body,” they say. “This type of class can feel like a real accomplishment, which ties into how the majority of spiritual people view the new moon – as a time for realignment.” In contrast, their full moon classes are designed to be slow and restorative; Jackson describes them as a metaphorical hug. “The full moon is when a lot of people feel more emotional or chaotic. I personally experience that, and I’ve noticed it in others, too,” Jackson explains. “We stretch more, we move slower, we focus on releasing what’s no longer serving us.”

Beyond personal practice, Jackson is committed to making yoga accessible. Their classes are entirely free. “Everyone is entitled to the ability to learn,” they say. “So many people aren’t able to pursue their interests because of a paywall. I don’t want that to be a barrier for anyone.”

NICOLE HELLTHALER – ACTIVISM

For Little Rock’s Nicole Hellthaler, Executive Director of the Prison Yoga Project (PYP), yoga began as a personal refuge but became the center of her career. As a 21-year-old teacher, she turned to yoga as a way to cope with the stress of her teaching job and her father’s terminal cancer diagnosis. What started as self-care soon evolved into a deeper practice that shaped her approach to education.

Through teaching, Hellthaler noticed how punitive responses to struggling students often made their situations worse. That realization led her to a bigger question: If punishment alone doesn’t rehabilitate students, why would it rehabilitate adults?

“Trauma is at the root of so much incarceration — both the trauma people have experienced and the trauma they’ve caused,” she says. “Punishment alone doesn’t rehabilitate people. And if incarceration isn’t about rehabilitation, then what’s the point?”

Most people in prison will return to their communities, yet recidivism rates remain devastatingly high. “The system is broken,” Hellthaler says. “But yoga and mind-

fulness offer real tools — self-regulation, impulse control, character maturity and increased executive function. These skills lead to better decision-making, empathy, and compassion. They help people break cycles of addiction, manage aggression, and process deep trauma.”

Through PYP, Hellthaler teaches weekly yoga classes at Pulaski County Regional Detention Facility, where she sees transformation firsthand. Participants report reduced stress, improved sleep, and a greater sense of self-awareness. Some, like former San Quentin participant Darnell Washington, have even gone on to become yoga teachers themselves.

For Hellthaler, yoga is an art form as well as a rehabilitative tool. “Being a yoga teacher is how I access my creativity — through words, sequences, and movement,” she says. “Yoga is the act of experiencing, channeling energy into breath and motion. It’s an anchor, just like painting or music can be.”

PAUL SUMMERLIN – MENTAL HEALTH & SPIRITUALITY

Paul Summerlin considers yoga both an art and a sacred path to healing. Nearing his third decade of practice, Summerlin was diagnosed on the schizophrenia spectrum in 2015; he turned to yoga as his sole treatment, rejecting Western medicine in favor of mindfulness and movement. “The effects of mindfulness offer an opportunity for the ‘storm in the mind’ to subside, if only for a moment; so I decided to make yoga an integral part of my life,” he explains.

Summerlin’s journey began with meditation in 2000, which eventually led him to the physical practice of yoga. “I realized that I needed more flexibility and mobility so I could sit in meditation longer,” he says. “That’s how I got ‘bitten by the yoga bug.’”

Over time, he realized that yoga was not just about movement or even mental well-being, but about spiritual connection. Summerlin has named yoga a way to “connect to the divine.” “Yoga has been around the longest in the human family,” he says. “All of it is spiritual; everything else is window dressing. All of it has to do with our soul. Nothing else.”

Summerlin’s dedication to sharing this philosophy culminated in his award-winning documentary, IT’S NO SECRET, PART 1, which explores the intersection of yoga and mental health. “The film includes testimonials, philosophy, and personal stories,” he shares. The project is under contract for distribution and expected to be released this year. His mission is to enlighten viewers about yoga as both a healing practice and a spiritual art form.

YOGA BEYOND THE MAT

For Jackson, Hellthaler and Summerlin, yoga is not just a series of movements, but an art form that fosters strength, healing and transformation. As these yogis continue to share their knowledge, they invite others to embrace yoga as a path to balance, resilience and community. In a world that often feels disconnected, their work reminds us that healing begins when we reconnect — with ourselves and with each other.

victory + vigil VICTORY + VIGIL

A Look at Sports as Art + Sports as Defiance.

INTERVIEW / KODY FORD

Maryam Amirvaghefi’s work lives in the space where resistance meets ritual, where the symbols of sport—wreaths, jerseys, podiums—are stripped of their assumed meanings and reborn as vessels for protest and memory. Born in Tehran and now based in Fayetteville, Amirvaghefi works across painting, sculpture and video to explore the tension between visibility and erasure, particularly as it relates to women navigating male-dominated systems. Her pieces examine not only what it means to survive, but how to be seen—and honored—in the act of surviving.

Drawing on her own experience as an immigrant and a woman from Iran, Amirvaghefi finds potent connections between the worlds of sports and art, both of which mirror broader struggles around gender, power and control. Her practice pays tribute to the quiet courage of those who resist—athletes who defy regimes, artists who refuse silence, and women who persist against systemic exclusion. With each piece, she invites viewers to reflect on the fragility and strength embedded in these stories, using familiar forms to ask urgent, unfamiliar questions.

The Idle Class caught up with Amirvaghefi to discuss her work.

Can you share a bit about your journey and how that has shaped your artistic voice and vision?

Growing up in Tehran, I was always aware of the social and political limitations placed on women—restrictions that shaped everyday life. That awareness didn’t go away when I moved to the U.S.—if anything, it gave me the space to reflect on it more deeply through my work. Being an immigrant and living between cultures has shaped how I approach my practice. There’s always a tension in my work—between sorrow and resilience, visibility and erasure. My voice has grown out of that in-between space.

What first drew you to the intersection of sports and art?

What really stood out to me was how similar the systems of exclusion are in both fields. In Iran, even before a woman can dream of being an athlete or an artist, she has to fight so many battles—starting in her own home, then against institutions. Once I saw that parallel, it was hard to ignore. I started to look at athletes, especially women, not just as competitors, but as symbols of protest and strength. That connection felt very powerful to me—sports and art both became ways to talk about resistance and survival.

How do you decide what materials or motifs to use to tell a specific story? Walk us through your process. I usually start with the idea or story I want to tell, and from there, I choose the material that holds the right emotional or symbolic weight. I work in mixed media—ceramics, painting, video—which gives me room to experiment. Ceramics, for instance, can speak to both fragility and endurance. When referencing sports, I often use objects like flower wreaths, jerseys, or podiums—symbols that can carry multiple meanings. I like working with that contradiction—turning something familiar into something that asks harder questions.

How do you approach blending personal memory with collective history in your pieces?

They’re deeply connected for me. In Iran, personal memories are shaped by collective realities—what you wore, where you could go, what was forbidden. So, my own memories naturally overlap with larger social and political histories. When I reference something like the Women, Life, Freedom movement, I’m also pulling from my own experiences. Personal memory can feel more vulnerable, but collective history comes with the pressure to be accurate and respectful. Both have their challenges, but they feed into each other in the work.

You highlight how both sports and art have historically marginalized women. What parallels do you see in how women are sidelined in these arenas?

Both fields have systems that push women to the margins—less representation, less funding, and less visibility. Whether it’s galleries or stadiums, the message often feels the same: you’re not the priority. And for women in countries like Iran, the barriers start even earlier—just being allowed into these spaces can be a struggle. That ongoing fight for visibility and value is something I’m always thinking about in my work.

Sports is a space of performance, competition and discipline. Do those themes resonate in your art practice? Very much so. Making art, like training for sports, involves repetition, discipline, and risk. You put in the work without knowing how it will be received. There’s also a performative element in both—how you’re seen, how you present yourself, how you’re judged. As a woman, that gaze is always present. I explore that dynamic a lot—the tension between being celebrated and being scrutinized.

Have there been particular athletes — especially women or Iranian athletes — whose stories inspired specific pieces?

Absolutely. Kimia Alizadeh, Iran’s first female Olympic medalist, who later defected, really stayed with me—her story goes far beyond sports. It’s about autonomy, courage, and protest. Elnaz Rekabi is another powerful example—her decision to compete without a hijab during the 2022 championships in South Korea in the middle of the Mahsa Amini protests was incredibly brave. It was a moment of silent protest that made global headlines. And then there are countless unnamed women—those who trained in private, who never made it to the news but still resisted in their own way. Their stories shape my work just as much.

What reactions have you received from viewers, especially from women or those familiar with the struggles you depict?

Some of the most meaningful responses come from women who say the work made them feel seen. It can be emotional—people have shared that it gave them space to grieve or to reflect. Iranian viewers often recognize the layers of symbolism, the things that don’t need to be said out loud. But even for viewers who aren’t familiar with the context, I’ve found that themes like resistance and resilience still connect. There’s something universal in those emotions.

What do you hope people take away from your work, especially those who may not be familiar with Iranian politics or the role of women in sports?

I hope they leave with a sense of what it means to persist in the face of oppression—not just in Iran, but globally. The fight for equality, whether in art or sports, is something many people can relate to. I want the work to humanize those struggles, to move beyond headlines and statistics, and highlight the quiet, everyday acts of courage that don’t always get attention.

Have you faced any challenges in making politically charged work?

Yes, there are risks—especially when dealing with Iranian politics. There’s the personal risk, the emotional weight, and sometimes uncertainty around how the work will be received. Some people prefer work that’s less political or more decorative. But I believe discomfort can be productive—it means the work is doing something important. Silence is not neutral, and I’ve chosen to speak.

MARYAMAMIRVAGHEFI.COM

Where Craft Meets Culture

WORDS / SHANNON PADILLA

PHOTOS / ZEB WILSON

Discover Arkansas’ Handmade Bike Movement.

While cycling has been big in cities such as Portland or Denver for a while, the biking community here in Arkansas is seemingly at the start of its boom. With Bentonville establishing itself in the cycling community over the last few decades, locals and travelers alike have been looking to become a part of this competitive yet creative hobby.

People are steering headfirst into the sport by reaching out to custom framebuilders — local craftsmen who produce the bikes from start to finish. Every framebuilder is unique, stapling or brazing their signature into each frame. Whether a rider is looking for a specific color pattern or wants to push the limits with a lighter, faster bike, framebuilders combine precision and a range of artistic backgrounds to handcraft something special for each client.

Jesse Turner of Slow Southern Steel Bikes blends his background in sculpture with welding to craft bikes. He got his start wanting to build his own back in 2021. With a previous knowledge of welding, he taught himself how to build by watching videos online. Friends and family saw his creation and wanted to get

their own custom pieces. Since then, he’s been a full-time framebuilder based on word of mouth. “I don’t have as much experience as other builders, I’m self-taught, it’s a one-man show…I just got lucky, I think. I didn’t plan all this when I was becoming a cyclist in Arkansas.” Since then, he’s completed 25 frames and counting.

The framebuilding process starts off with a conversation. The client decides on a framebuilder by the handmakers’ aesthetics and word of mouth. Clients can also specify which type of riding they’re interested in or the trails they’re looking to explore, but knowing specifics isn’t required.

Turner shows his current project, a custom for his girlfriend, who will be participating in the Arizona Trail Race — a trek across the Grand Canyon where she must carry the bike on her back for part of the trip. Jesse emphasizes how crucial it is to make the bike as light as possible without losing quality.

Michael Crum of Magnolia Cycles has been in the cycling business for over two decades. With his background in fine arts and a clear passion for frame building, you can see his intentionality in every piece with performance, style and pragmatism being the foundation he strives for. “We want to get them on the bike that’s right

for them, not just the bike we have in stock,” he says. “We strive to educate customers to the level they are comfortable. We meet them at their level of knowledge and bring them to whatever level they want to be,” Crum states.

The biking community has changed throughout its time in Northwest Arkansas. Crum speaks on the history of biking and the growth he’s witnessed over time in the business: “Historically, the industry has done a poor job of reaching out to women and people of color. There have been some pushes in the industry to correct that… I hope everyone feels more and more welcome to join the space. It makes the industry and community as a whole so much better.”

With a community as interconnected as Northwest Arkansas, the sport is finding itself amongst larger communities with local opportunities, such as community bike rides with Ozark Gravel Doom, which specializes in backcountry endurance-level bikepacking routes. The fifth annual Bentonville Bike Fest, happening May 23-25, will feature Magnolia Cycle demos for you to test out for yourself.

SSS.BIKE / IG: @SSS.BIKE MAGNOLIACYCLES.COM IG: @MAGNOLIA CYCLES

BOMBING HILL

WORDS / ISABELLA WISINGER

Inside the Skating Movement Nouveau of Northwest Arkansas.

Meet Clementine Simpson, the Northwest Arkansas skater who popularized the “hill bombing” movement and launched a downhill skating subculture as the social media sensation @clem.skates on Instagram. Simpson lives in Fayetteville and works as an ER nurse, balancing her time between medicine and managing the Arkansas Roller Skate Crew. Known for her daring tricks, high speeds and casual use of common roadways for creating content, she is redefining what it means to be a modern athlete.

Starlight Skatium — Fayetteville’s most well-known skating rink — was where Simpson first found her passion for the sport. She and her childhood friends joined a speed skating club in 2008, which led to her participation in the national Speed Skating competition hosted by USA Roller Sports at ages 12 and 13. In her four years of competing, Simpson placed first and then second in the quad category, taking home two national titles.

After her early victories, her interest in competing tapered off. “There’s not anything beyond nationals except for worlds. I considered competing in the Olympics, but I would have had to participate as an ice skater because rollerskating isn’t a recognized Olympic category.”

The loss of her brother Solomon Simpson, days before her 13th birthday, also caused her to step back from skating for a time. She had to process the grief of losing a sibling in her early adolescence, a vulnerable time for anyone, especially someone dealing with death in the family. Despite retiring from competitive skating, Simpson stayed connected with the sport, taking her first job at a roller rink.

Eventually, after coming to terms with Solomon’s passing, Simpson realized her brother would have wanted her to pursue her interests and dreams fully. So, while enrolled in the nursing program at the University of Arkansas in 2020, she was inspired to start her social media account. It was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and she found outdoor skating to be a way to combat the isolation of quarantine. “Fayetteville is very hilly, so I got super into downhill skating. There wasn’t much of a category for it then, and it’s still such a niche thing that doesn’t get a lot of coverage in the skating community.”

One of the videos that helped @clem.skates take off was the initial Dickson Street “hill bombing,” a feat which Simpson describes as taking a steep downhill grade at full speed. As she accumulated followers online, Simpson put out a group skate offer through social media. When over eighty people reached out within the first two weeks, she knew there was an opportunity to create a new community centered around skating in Northwest Arkansas that could accommodate the social distancing guidelines of the time. Shortly after, the Arkansas Roller Skate Crew was born.

Organizing the skate club helped propel Simpson through the trials of nursing school. She has stayed busy organizing a myriad of pop-up events and club appearances, bringing the crew out to Fayetteville’s PRIDE and Mardi Gras parades, and putting on events like Shred Fest and Halloween-themed group skates. Her social presence has led to brand partnerships with French company Flaneurz (also known as Slades in the U.S.) and Luminous Wheels, which makes LED gear for quad and inline skates and longboards. (”Longboarders are welcome too! We’re inclusive!”)

What’s next for the protagonist of Arkansas’ skating scene? A personal brand launch. “I’m working on the site design right now. It’s going to tie in Ozark and cowboy themes with traditional skate motifs.”

Simpson’s upcoming skating brand will be fittingly named Hill Bombers. When it goes live, hillbombing.com will be a hub for downhill skating culture, providing video content, promoting worldwide skate events, and selling must-have merchandise for hill bombers everywhere.

Simpson’s trajectory from speed skating champion to social media guru has established her as a cultural pioneer. With her momentum, passion, and planning, she is set to expand the downhill skating community far beyond the streets of Northwest Arkansas.

IG: @CLEM.SKATES

PG 24: Clementine Simpson (Photo by Maggie Lee Fisher)

PG 25: Arkansas Roller Skate Crew (Photo by Clementine Simpson)

PHOTOS / MARIANNE NOLLEY

A LACK OF GAME

Reflections on Hunting by Jonathan Wilkins

I

t isn’t in me to call hunting a sport. Ultimately a sport is a game, a trivial thing, and it necessitates competition. It demands a winner and a loser. Hunting, as I’ve been fortunate to experience it, is anything but.

Hunting has been the single most life-affirming and personally validating pursuit I’ve ever participated in. A decade and a half ago, when I quietly walked away from the Little Rock music scene, it was because I felt that I had lost my creative integrity. I had learned to play guitar and began writing songs as a means of questioning my surroundings, exploring my intentions and pushing back against systems I thought didn’t cut the mustard. After fifteen years, it had devolved into barroom hollering, performing to an audience that only wanted to be momentarily distracted from the banality of a 9-5.

Through happenstance, want-to and an inspiring lack of financial fortitude, I’ve changed how I interact with the world as I’ve learned to walk quietly in the woods. I’ve become confident enough to listen more and shout less. Paying attention, moving slowly and learning everything you can about your environment pay much higher dividends than fast guns or fancy gear. Modernity has taught us to struggle against nature, wrestle it into submission and break it to our will. That sort of imbalanced interaction with the natural world gave us the wholesale slaughter of American Bison, the desertification of the Southern Great Plains and the extirpation of whitetail deer from almost the entirety of its native range. It’s also distanced us so far from some of the most rudimentary human experiences, that many of us believe that there are incredibly innate encounters that are beyond us.

I’m more proud of the woodsmanship skills I’ve garnered than almost anything else I’ve accomplished. I can distinguish beaver tracks on a muddy bank from a creekside raccoon’s wanderings. I can discern when they moved through an area, why and when they may be back. I know when in the year, you’ll find an Arkansas black bear eating acorns or black gums or the ephemeral fruit that grows on the tip of a Devil’s walking stick. I’ve learned to trust myself in wild places and depend on my own abilities to make things happen in difficult circumstances.

More than anything, I’ve gained a way of seeing the world that depends on the notion of seasonality. Slipping through the woods as spring transitions to summer and one year rolls into the next reminds me that life is ongoing. The world doesn’t stop, and it’s my duty is to find solace in the beauty of incremental growth. I’m more now than I was, and as the seasons pass, I’ll continue to change. I’ll reach a point where grit and physical ability will fail me. I’ll have to move more slowly, more sure-footedly, relying on the experience gained from seasons past. Whenever it comes to pass, that my body will no longer carry me to the wild, wooded places I love, there still won’t be a winner or a loser. There will only be the cycle and the seasons and my chance to be a part of it.

About Jonathan Wilkins

Jonathan Wilkins is a Southeastbased generalist with a focus on making things and storytelling. He’s also the founder of Black Duck Revival, the brain trust for the multiple personalties of his hunting pursuits that began when he converted a small Delta church into a lodge. He writes, cooks wild things and changes diapers with his wife Marianne and their three children in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Modernity has taught us to struggle against nature, wrestle it into submission and break it to our will... It’s also distanced us so far from some of the most rudimentary human experiences, that many of us believe that there are incredibly innate encounters that are beyond us.”

Through the gate & the dust

A photo essay on Springdale’s Rodeo of the Ozarks.

WORDS + IMAGES / TYLER ORSAK

When you have a large camera around your neck, people tend to assume that you’re supposed to be somewhere.

I paid my admission fee for the annual Rodeo of the Ozarks, brought my Fujifilm GW690 II, a medium format film camera, and 5 rolls of film in my pockets. I walked to the staging coral, the large area where all the riders wait to go into the arena. The gate was guarded by an older fella with a white Stetson. He glanced down at the oversized camera around my neck, gave me a slight nod and let me through. No questions.

Once inside, I just used a bit of courage to carefully walk up to the 8-foot tall sets of eyes under various enormous hats. I’d give them a smile and hold up my camera to ask permission. They’d smile back, and turn their horses around to face me. Out of my shirt pocket, I handed each performer a card with my contact info. They all reached out for a copy.

If you’re meant to be somewhere, bring a large camera.

— Tyler Orsak

In Memoriam

Over the past year, Arkansas has lost many individuals who contributed greatly to the creative community. The Idle Class wants to take a moment to honor them. Gone but not forgotten — their legacies live on.

ANGIE GOMEZ

Artist Rogers

MATT OWEN

Graphic Designer

Little Rock

WERNER TRIESCHMANN

Playwright

Little Rock

aNNA MARIA WYNTERS

Artist

Fayetteville

Stacy BATES

Artist Fort Smith

CLAY FITZPATRICK

Art Enthusiast

Little Rock

Portraits by Chad Maupin of Big Bot Design