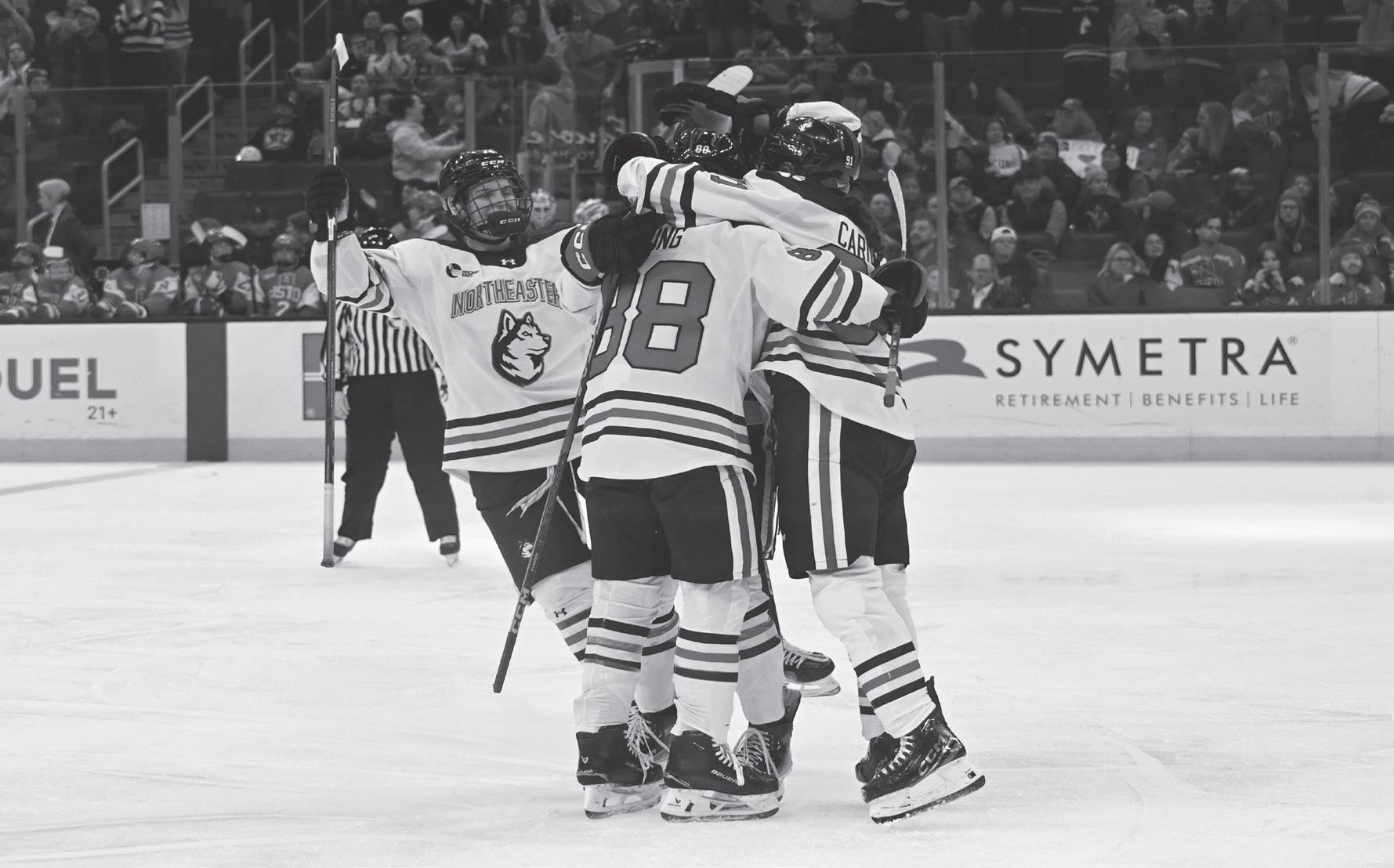

Northeastern increased salaries, assets and employees in Fiscal Year 2024

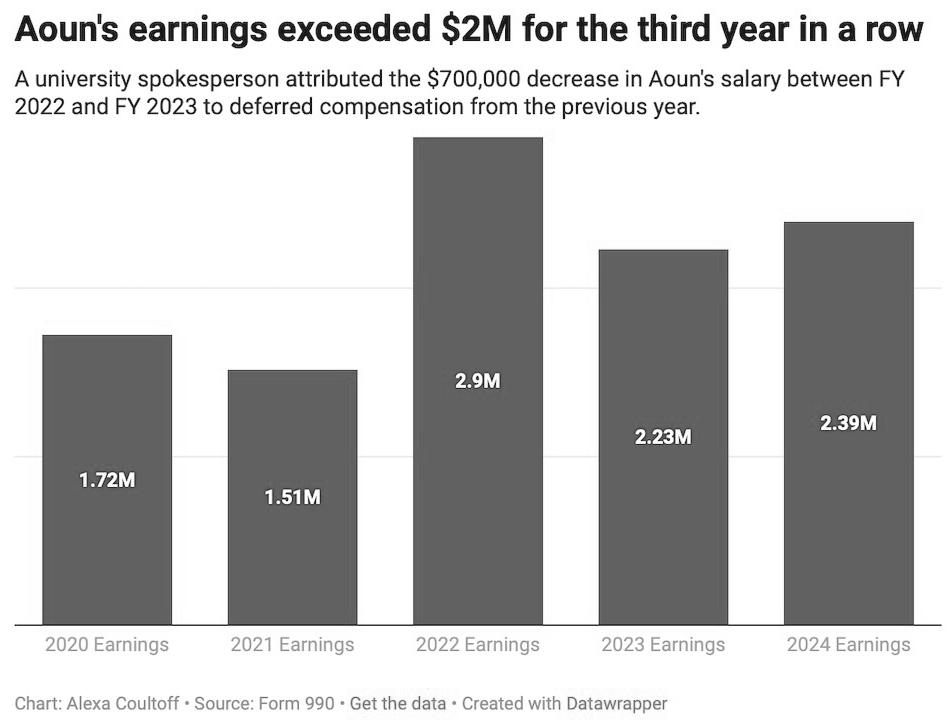

For the third year in a row, Northeastern President Joseph E. Aoun’s salary has exceeded $2 million, making him the highest-paid university president in Massachusetts, according to financial disclosures.

Aoun was the eighth highest-paid university president nationwide in FY 2021 and the 24th in FY 2022, according to reporting by The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Aoun’s salary information, along with a comprehensive overview of the university’s finances, is released annually in the Form 990, an information

MBTA cracks down on fare evasion

As Northeastern students stroll through Ruggles Station this fall, they might see some new faces from the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, or MBTA, carefully monitoring for any instances of fare evasion. Since Sept. 8, the MBTA has deployed Fare Engagement Representatives at key MBTA stops to promote fare compliance as a part of the Fare Engagement Program, or FEP.

In addition to placing employees, who wear blue vests, at the entrances, the MBTA has installed posters

and displays cautioning riders against fare evasion. The attempt to increase fare payment has been ongoing since October 2024 in light of decreasing revenue.

Elizabeth Winters Ronaldson, deputy chief of fare revenue for the MBTA, was asked about fare loss in a media availability meeting at Government Center station Sept. 8. She said before COVID-19, the MBTA generated about $670 million a year in fare revenue, as compared to $440 million last year. In a 2021 study, MBTA fare evasion loss was estimated between $25 million and $30 million annually.

on Page 3

return that tax-exempt organizations with total assets exceeding $500,000 are mandated to file to the Internal Revenue Service, or IRS. Form 990 ensures that tax-exempt organizations, which include universities, comply with the requirements to maintain their tax-exempt status, according to the IRS.

Northeastern has expanded rapidly in the matter of a decade, increasing its enrollment by more than 16,000 students since 2013 and leading total enrollment growth across all Boston colleges and universities, according to data published by the city.

SPORTS

What happens to club teams without Matthews?

Read more about what the demolition means for club sports.

LIFESTYLE

Are performative males method acting?

Read about what students think of the aesthetic.

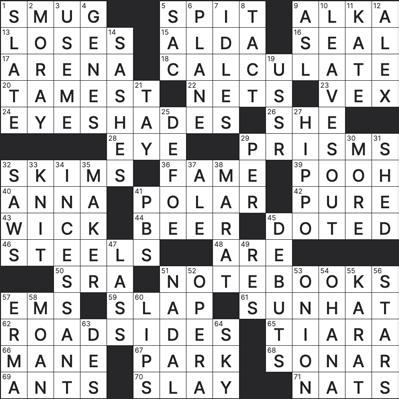

Solve The News’ Fall crossword!

Answers will be revealed in the next print issue.

Three NUPD officers added to disciplinary database

EMILY SPATZ AND ZOE MACDIARMID Editor-in-Chief and Campus Editor

A former officer with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, or MBTA, who supported a colleague accused of rape — then wrote a letter asking the court for leniency in sentencing — is now employed by Northeastern’s police department, records show.

Brian Burt was among three Northeastern police officers added to a state database documenting sustained officer misconduct this year, bringing the department’s total to six. Three Northeastern officers were added to the database when it first launched in 2023, The Huntington News previously reported.

Burt, Timothy Flynn and Patrick Gaumond — who are all still actively listed on the Northeastern University Police Department’s roster — faced multiple complaints each. They were added to the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training, or POST, disciplinary database sometime after January, web archives show. None of the officers responded

to several requests for comment from The News.

The disciplinary records database, collected and made public in response to landmark reforms following George Floyd’s murder, lists thousands of police officers across the state of Massachusetts who have sustained misconduct allegations starting in 1984. As of publication, it was most recently updated Aug. 19. The Northeastern University Police Department, or NUPD, has 58 officers as of Sept. 2, according to POST.

Burt, a former MBTA police officer of 25 years, was suspended in March 2024 for associating with a former transit officer who was indicted on three counts of rape while on duty. Burt joined NUPD in February, according to his LinkedIn page, and is certified as an officer until Dec. 1, 2028.

While the database doesn’t list the name of the defendant, former MBTA officer Shawn McCarthy was convicted on three counts of rape in March 2024, according to the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office. During McCarthy’s trial, Burt attended court “every day in support

of the defendant,” and wrote a letter “seeking leniency” for the convicted officer after a guilty verdict, according to the POST database.

In the 2012 incident, McCarthy drove two women in their early 20s to an area near the Museum of Science, then raped both. He was on duty at the time and used his cruiser to transport the women. In 2024, McCarthy was sentenced to four to six years in prison, CBS News reported. He could not be reached for comment.

“Against the advice of a fellow officer, McCarthy offered the women a joyride in his marked police cruiser and drove them around the area with blue lights flashing,” the district attorney’s office said in a press release at the time of his conviction. “After stopping in a vacant lot so the women could relieve themselves, McCarthy said he hadn’t risked his job for nothing and he would not take them back downtown until he got something out of it.”

Burt was suspended for three days in March 2024 for two complaints stemming from his support of McCarthy, which violated MBTA Transit Police standards.

Photo courtesy Northeastern Archives

Photo by Aya Al-Zehhawi.

Photos and graphic by Margot Murphy

Graphic by Emma Liu

ALEXA COULTOFF AND FRANCES KLEMM Data Editor and News Staff

ANNALISE KARAMAS News Correspondent

FINANCES, on Page 2

A graphic featuring David Madigan (left), Joseph E. Aoun and 990 forms. The annual Form 990 revealed raises for university executives and grant allocations. Photo by Isaac Pedersen. File photo by Val O’Neill. Graphic by Lily Cooper.

Passengers wait for the arriving Green Line train at North Station Sept. 15. The MBTA deployed Fare Engagement Representatives to ensure fare compliance.

Photo by Ian Dickerman

Northeastern increased salaries, assets and employees in Fiscal Year 2024. Here’s a breakdown.

Northeastern’s endowment has steadily grown in the past five years, exceeding $1.9 billion in FY 2024.

Northeastern’s Form 990, which The Huntington News requested from the university under Massachusetts’ public record law, lists the compensation of key university employees as well as the university’s spending activity and contributions to outside organizations. The report spans 12 months from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024, or FY 2024.

Here’s what The News’ review of the form found.

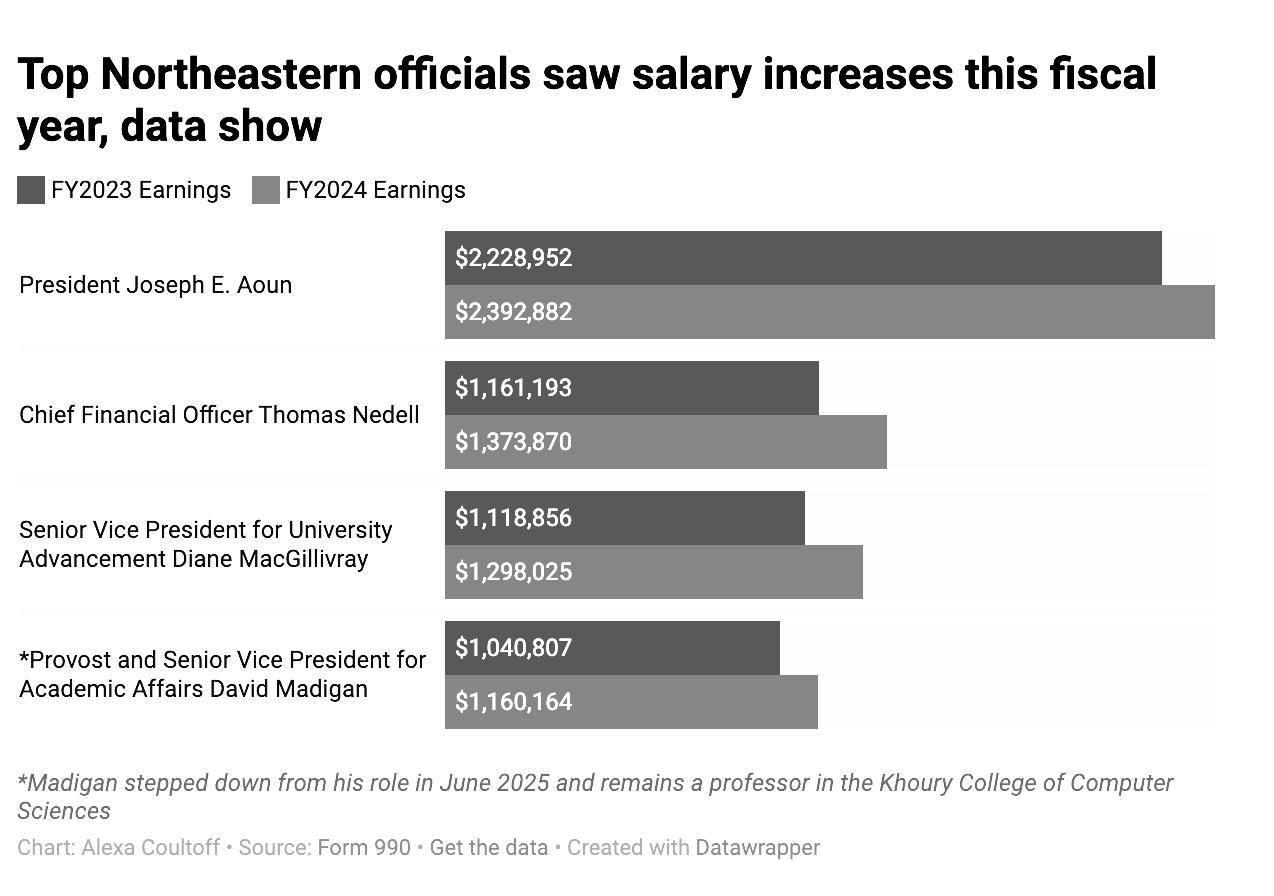

Top university officials saw salary increases

Aoun took home $2.4 million in FY 2024, according to the form.

While Aoun’s earnings increased $160,000 from the previous fiscal year, a review of Northeastern’s previous Form 990s by The News revealed that he made far more in 2022. Aoun’s earnings dropped nearly $700,000 — from $2.9 to $2.2 million — between 2022 and 2023. A university spokesperson told The News in an email that the $700,000 was deferred compensation from FY 2021.

The top three earners below Aoun in 2023 and 2024 remained the same: Chief Financial Officer Thomas Nedell, who compiles the Form 990, Senior Vice President for University Advancement Diane MacGillivray and former Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs David Madigan. Madigan stepped down from his position in June but is now a professor in the Khoury College of Computer Sciences. Beth Winkelstein assumed the position Aug. 22 at the start of the 2025-26 academic school year.

Compared with the 2023 fiscal year, Nedell earned $212,677 more in 2024, MacGillivray earned $179,169 more and Madigan earned $119,357 more.

The university also disclosed that the only loan it paid both years was $2.7 million to Madigan, categorized as a “home loan.”

Usama Fayyad, the university’s senior vice provost for AI and data strategy and senior advisor to the

president, earned $343,670 more in 2024, putting his total earnings at $1.06 million. The university’s embrace of AI has become more evident in recent years — in April, it announced a partnership with Anthrophic’s Claude, an AI chatbot, and Aoun told the Class of 2029 at this year’s convocation that “AI is going to change everything.”

The form also explained that Aoun travels first-class “if business class is not available” and that the university pays for his wife to travel with him “when necessary for business purposes.” He is provided with social club dues and housing, which consists of a Beacon Hill property that was worth an estimated $11.6 million in 2025. Other employees are given first-class flight privileges when “necessary,” if Aoun approves, according to the form.

Added employees, expenses and assets

Northeastern gained 2,044 employees between fiscal years 2023 and 2024, according to the form.

The university also increased its assets by nearly $400 million over the 2024 fiscal year. Its total net assets, after deducting about $20.3 million in liabilities, was $4.1 billion. While Northeastern lags behind its Boston counterparts, including Boston University and Boston College, in total net assets, its increase was similar to Boston College but larger than Boston University’s $167 million growth.

Total net assets indicate an institution’s financial health and can be tangible, intangible or financial. It includes endowment, land, equipment and licenses.

Northeastern disclosed that it spent $1.1 million on fundraising in 2024 after not allocating any expenses to the category the previous year. The university had a net loss of $32,486 from its fundraising events, which include efforts over email, phone and in-person.

The university notably spent $69.3

million on consultants, a number down from $78.2 million in FY 2023. While most universities spend a few million dollars on consultants each year, similar institutions, such as Boston University, Boston College and Syracuse University, did not hire any in FY 2024, bringing their respective functional expenses to around $100 million less than Northeastern. Grants to outside organizations

The university reported spending a total of $1.3 million lobbying the federal government in 2024. Nedell wrote in the Form 990 that the university “pays membership dues to membership organizations which may engage in lobbying activities.”

Northeastern’s lobbying activity includes funding for higher education programs and policy issues “including financial aid programs, work study, cooperative education, international students and lifelong learning,” according to public lobbying disclosures. The university also allocated money in support of federal research programs at the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration and Department of Homeland Security.

The News previously reported that Northeastern has lobbied $270,000 each quarter since the third quarter of 2022, more than most Ivy League institutions.

Northeastern paid grants to 168 outside organizations in 2024, according to the form. The highest grant was $8.2 million and went to high-tech startup US Ignite Inc. The university gave $2 million to Lukla Inc., an apparel company based in Portland, Oregon.

Most other grants went to universities across the nation as subawards, with the highest including $2.5 million to the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of North Texas, $2.3 million to the University of Pittsburgh and Temple University and $2.2 million to Northern Arizona University.

Subawards are a way for universities to collaborate through grant funding. When Northeastern is the prime institution on a grant, it distributes the funding to its partner institutions in the form of subawards for research.

Three Northeastern police officers added to state disciplinary database, one for supporting ex-officer convicted of rape

According to MBTA Transit Police standards, officers are prohibited from associating with people who they “know, or should know, are persons under criminal investigation or indictment, or who are convicted felons.”

Flynn, who has been with NUPD in various roles since March 2018, is listed in POST as having two complaints for an incident involving misuse of department property. The allegation, made in October 2024, is described in POST as an “improper act which reflects discredit upon the officer or upon the police department.”

Flynn was suspended from the department for two days and from his role as lead firearm instructor for six months, according to the database. He is certified by POST until Jan. 1, 2029.

According to his LinkedIn page, Flynn is currently the armorer of NUPD, meaning he is responsible for inspecting and maintaining the department’s firearms and other equipment. He’s held the role since January 2022 and served as police sergeant and a firearms instructor — among other roles — during his 13 years with the department. He previously worked for the Norfolk County Sheriff’s Office, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Gaumond has two sustained complaints against him, both issued in January 2021. According to the database, they stemmed from an incident when Gaumond reportedly submitted an official State Police document “with information that he reasonably should have known was inaccurate.”

In another complaint, listed as “other/conduct unbecoming,” the database states that Gaumond “used official State Police letterhead and his official position as a Trooper to curry favor and seek consideration for dismissal of a parking violation in the city of Boston.”

The News could not verify when Gaumond joined NUPD, but he is certified by POST until Feb. 1, 2029.

In August 2023, The News reported that three NUPD officers — Jason Grueter, James Witzgall and Brenda Zirpolo — had sustained allegations either during or prior to being employed by NUPD. Grueter has one sustained complaint of bias on the basis of gender, Ziprolo has one report of conduct unbecoming and Witzgall has five allegations of conduct

unbecoming. All three are still certified by POST.

“As a longstanding policy, the university does not comment on personnel matters,” Vice President for Communications Renata Nyul wrote in an email statement to The News.

Soon after the state released the database in August 2023, police forces statewide heavily criticized POST for gaps, inaccuracies and omissions. Officers also complained that POST included low-level complaints, like sleeping on duty and being absent from work.

Law enforcement agencies in the state are required to submit “credible” misconduct complaints to POST, including incidents that resulted in discipline or an internal affairs investigation, according to POST’s website. The public can also submit complaints, which POST sends to agencies for investigation or investigates itself.

Officers can petition to remove or amend allegations and disciplinary actions listed in the database. Grueter and Ziprolo had multiple allegations when The News first reported on their misconduct in 2023, but they were later amended. The database also doesn’t list officers who “resigned or retired in good standing” but does include officers who resigned or retired to avoid discipline, according to POST.

NUPD has one of the lowest numbers of officers on the POST database among private universities in the Boston area. Boston University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology both have over a dozen officers in the database, while Harvard University has more than double that.

NUPD, from Front

Graphic by Alexa Coultoff

MBTA cracks down on fare evasion

Riders who evade fare payment and are caught by FEP representatives will face penalties. First offense riders will receive either a written warning without a fine or an issued citation with a fine. Fines begin at $50 for the first three citations, and after the third, riders are expected to pay a maximum of $150. The MBTA said the fine may vary based on the number of times a rider has been cited and the way they violated paying for their fare.

In an interview with Boston. com, MBTA General Manager Phil Eng said he feels confident in the new FEP, noting fare collections increased by up to 35% at bus and trolley stations where fare representatives were on site.

Bowden Meshkowitz, a firstyear economics major at Bunker Hill Community College, is skeptical of the efforts.

“I live in Jamaica Plain — I use the MBTA to get in and out of the city. I use the Jackson Square stop,” Meshkowitz said. He noted that, on multiple occasions, he has seen Orange Line riders evade fares in front of MBTA workers, but they never stop the culprits.

Approximately 66% of Northeastern students are from out of state, with about 21% being in-state residents and 12% being international students. Citywide, 163,000 students are enrolled in Boston-based undergraduate and graduate degree programs, making up about 4% of Boston’s population overall. With the MBTA being the fourth-busiest public transit system in the United States,

some people believe students are the largest contributors to fare evasion.

Minh Mai, a fourth-year business and political science combined major at Northeastern and Dorchester native, feels the new fare checks could improve the MBTA for everyone.

“I’ll be honest with you, with my experience, I don’t think a single person pays [their fare]. And that’s just like strictly an observation because it’s so easy,” Mai said. “But also, in all honesty, I feel like there’s a stigma around Boston having so much wealth and so many resources that they think that public transit should be free. And I’m totally for free public transit, but there have to be some opportunities, yeah?”

The MBTA’s Green Line has 59 above-ground stops, most of which lack ticket booths or significant security infrastructure. This is primarily due to space limitations caused by the line’s historic design and its placement in-between active roadways.

“It’s a lot easier to get on the second cart or the third cart and avoid paying all together,” Mai said. “But I feel like, as a Boston resident, I want to challenge that by saying: ‘Well if you look at who was in these Green Line spaces, they’re technically more affluent and more resource rich areas. And it’s kind of about time that people in these areas participate in the infrastructure and help to maintain a valuable resource that everyone uses. Especially international and out-of-state students, they have the resources to come here, they have the resources

to study here, maybe they should contribute to the city around them.”

Sarah Ruana, a second-year computer science major at Northeastern from Seattle, also attributed the fare crackdown to students.

“A lot of the Boston colleges are so expensive that a lot of students have the belief, ‘Why am I paying so much for tuition if there’s not some sort of deal between Northeastern and the MBTA?’” she said.

Ruana thinks universities in the area should pay a fee to the MBTA that would allow their students to ride the T for free or at a discounted

instead of hiring more people to work these [FEP] jobs, they should go back to what they did pre-COVID, where you only get on at the front,” she said.

“As a younger Boston resident, I was like, ‘I am entitled to this transit because I live in the city — I belong here.’ But now, growing up, I understand the value of it, so I pay,” Mai said. “So it differs, there is a sense of ‘I am a citizen here, I’m a resident here, this is a resource for me.’”

“Twice today, I was walking out and some guy was waiting, and he ran in [without paying] and yelled

price. She also said the pre-COVID-19 setup of the system could’ve helped prevent fare dodging.

“I think that the best solution is

QUICK READS

Thousands gather in Boston Common for vigil in honor of Charlie Kirk

On Sept. 18, more than 1,000 people gathered in Boston Common to attend a candlelight vigil in remembrance of Turning Point USA Founder Charlie Kirk. Afterward attendees marched to the State House to pray for Kirk. The event did not go uninterrupted. Though the vigil was fenced off by metal barricades, there were a few dozen counter protesters present on the other side holding signs that reading “Fascists get off our lawn” and shouting.

Kirk was assassinated on the campus of Utah Valley University, one of the stops on his American Comeback Tour series where he speaks to and debates university students. He was primarily known for his extreme viewpoints and aggressive debate tactics, making him a polarizing figure.

According to the Boston Police Department, two people were arrested at the vigil, one for disorderly conduct and the other on a weapons charge.

‘Call the cops!’ As he ran down the train station, there was an MBTA worker standing right there, and they didn’t do anything.”

Boston Local Food Festival celebrates flavor, culture and community

The Boston Local Food Festival took over the Rose Kennedy Greenway Sept. 14 with a vibrant mix of flavors, cultures and community spirit. Described by attendees as “delicious,” “heartwarming” and “culturally diverse,” the festival brought together local vendors, passionate foodies and first-time explorers for a day that felt equal parts farmers market and cultural exchange.

The festival was not only a flavorsome showcase of cultural cuisines but also a unique experience with the vendors’ take on everyday foods. From Dry Brews’ “coffee in a bite,” an espresso shot turned to a chewy gummy, to Backriver Blends’ handcrafted Jamaican jerk-marinade, the day was full of culinary surprises. The festival hit all the sweet and savory bases, from freshly-baked oxtail pot pies to a fully organic blueberry crumble crisp. Kourtney Bichotte-Dunner, a fifth-year environmental studies major at Northeastern, agreed that the festival is a great starting point for stepping out of foodie comfort zones.

“I never had Burmese food before. I really wanted to try something like this, I’m a really big foodie,” Bichotte-Dunner said. “I love trying something new, and there are a lot of shops to do that here.”

For some, the festival was an unplanned adventure. Aline Franco

and Michelle Garcia, Boston residents who are originally from Brazil, stumbled upon the event after seeing an advertisement for it online.

“We didn’t have any plans, so we said, ‘Let’s go there,’” Garcia said. What they found was a feast of global flavors right in the heart of Boston.

“They have food from all over the world: Brazilian, Arabic, even one for beer lovers,” Franco added.

Nearby, Koi Green, a third-year information technology major at Northeastern, was attending for the first time as well. “It’s entertaining to try different foods,” Green said. “It’s almost like brain nourishment because you’re learning about different cultures while eating.”

For others, the Local Food Festival is a fall tradition. Aida Evans, a fifth-year environmental science and landscape architecture combined major at Northeastern, has made it an annual ritual. “I’ve been going for three years — it’s the event I go to every year,” Evans said.

The festival isn’t just about tasting; it’s also about storytelling. Many vendors see the event as a chance to share their heritage with the Boston community. For Alev and Seline Gulden, owners of onebitesweet, the festival provides a stage for Turkish traditions.

“We wanted to spread Turkish food because there’s not a lot around here, and it’s our heritage,” Seline Gulden said. “It’s a lot of

work, spending the entire weekend in the kitchen, but it’s worth it.” Their babkas and baklavas sold out quickly and got raving reviews.

At Prophecy Chocolate, Mateo Block introduced festival-goers to chocolate atole, an ancestral cacao drink prepared by visiting friends from Oaxaca, Mexico. “It’s a mix of corn base with chocolate foam on top — it’s about sharing culture as much as flavor,” Block said.

For Red Apple Farm, a family-run orchard that’s been around since the early 1900s, it was a chance to showcase its famous cider donuts — named the best in New England — as well as the second-best orchard in the country by USA Today.

For many, the festival felt like something bigger than a food fair. It was about people, energy and community.

“I don’t get out much to eat, so it definitely opens my eyes to different restaurants that I probably wouldn’t seek out on my own,” said Shannon Damuth, a third-year political science and economics combined major at Northeastern.

For Katherine Ronzoni, a second-year business administration major at Northeastern, the fair is the perfect way to spend a Sunday in Boston.

“I really love events like this where I get to be outdoors while the weather is still really nice and just spend quality time with my friends,”

Ronzoni said. “It’s just so much fun to try all these foods from local small business owners. And seeing brands like When Pigs Fly Breads has been really cool; they’re like local celebrities to me.”

Noah Quist, a local business owner of Three Gingers Jerky, said the fair was a milestone in turning their small business into a wholesale program where clean ingredient jerky can be accessible nationally.

“I had for years wanted to be involved in this organization,” Quist said. “It was more than anticipation for me: I was just so excited to be here.” Quist’s favorite part about being a vendor at the festival is the “interactions with the customers. Our product is so familiar to people, and yet, when they eat ours, it’s an immediate conversation. It’s curiosity, it’s interest.”

On the sunny Boston waterfront, the Local Food Festival proved to be more than just an afternoon of free samples. It was a reminder of Boston’s identity as a city for everyone: welcoming, family friendly and full of cultural pride.

Whether it was oysters and dumplings or baklava and donuts, the festival brought both returning locals and curious first-time attendees together for a flavor-packed day. Evans summed the festival up in three words: “popping, yummy and heartwarming.”

NU ranked 46th best national university

Northeastern was ranked the 46th best university in the nation in the U.S. News & World Report’s latest annual university rankings, released Sept. 23.

For the first time in two years, Northeastern was ranked in the top 50. The university was listed 44th in the 2023 ranking but plummeted to 53rd in the 2024 report after a shift in U.S. News & World Report’s methodology. Last year, Northeastern fell one spot to 54.

Northeastern is tied with four other universities: Lehigh University, Purdue University, University of Georgia and University of Rochester.

U.S. News & World Report uses up to 17 indicators, which are ranked and weighted by “literature reviews, opinion polling, and consultations with higher education leaders and institutional researchers,” to compile the report. The most important factors are graduation rate, performance upon graduation and assessment by peer institutions.

Northeastern remains lower on the list than other private universities in Massachusetts — the Massachusetts Institute of Technology claimed second place, while Harvard University came in third. Boston College, Tufts University and Boston University also claimed spots above Northeastern.

The U.S. News & World Report ranking was released on the heels of an annual College Free Speech Ranking published Sept. 9 by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. The free speech advocacy group ranked Northeastern 253th out of 257.

MBTA, from Front

ARABELLA ENGLISH News Correspondent

A MBTA Tap to Ride device at Ruggles Station. The Green Line’s above-ground stations allowed locals to easily avoid paying the fee.

Photo by Annalise Karamas

Photo Courtesy Gage Skidmore

Northeastern placed near bottom of free speech advocacy group’s annual university rankings

ZOE MACDIARMID Campus Editor

Northeastern claimed spot 253 out of 257 in the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s annual College Free Speech rankings, dropping 75 places from last year.

The 2026 report, released Sept. 9, collected data from more than 68,000 college students nationwide throughout the 2024-25 academic year. The rankings come after a semester marked by repeated federal government attacks on higher education institutions, and the organization said that most colleges earned around an “F” grade for free speech.

Northeastern declined to comment.

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, first included Northeastern in its annual report in 2022-23, giving it 37.6 out of 100 points and a ranking of 155 out of the 203 evaluated colleges and universities. Although Northeastern’s score increased in 2024 and 2025 reports to 37.8 and 42.1, respectively, its overall ranking dropped each year.

“The rankings come at a notable moment for free speech on college

campuses: clashes over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a vigorous and aggressive culture of student activism and the Trump administration’s persistent scrutiny of higher education,” the report reads.

This year, Indiana University, Columbia University and Barnard College claimed the bottom three spots while Claremont McKenna College, Purdue University and the University of Chicago ranked the highest.

The report evaluates universities in six areas using student responses: comfort expressing ideas, self-censorship, disruptive conduct, administrative support, openness and political tolerance. Northeastern students indicated their comfort expressing ideas increased, but they reported more self-censorship, less openness on campus, and less administrative support and political tolerance for their ideas. FIRE surveyed 268 Northeastern students for the 2026 report.

Northeastern attracted FIRE’s attention in April after a student group canceled a speaker event when university administration required it to provide a list of attendees. The talk, titled “Israel’s Attack on Gaza: The

Question of Genocide, and the Future of Holocaust and Genocide Studies” was set to feature Raz Segal, an Israeli historian and associate professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Stockton University.

Northeastern’s Center for Student Involvement has policies for all events held on campus, which may include requiring registration and Northeastern University Police Department presence. A university spokesperson told The Huntington News in April that the student group did not go through proper procedures to hold the event.

In a letter dated April 25, FIRE Campus Advocacy Program Officer Aaron Corpora wrote to several Northeastern administrators, condemning the university for asking the student group for a list of attendees.

“If Northeastern is to live up to its free speech promises, it must commit to no longer require attendance lists for expressive events,” Corpora wrote. In this year’s report, FIRE categorized the canceled event as a “deplatforming” incident, which FIRE defines as “an attempt to prevent some form of expression from

occurring” and attributed it to why Northeastern drastically slide down the rankings list.

Last semester, the Trump administration took particular aim at several high-profile universities, notably Columbia University and Harvard University. But despite a steady flow of attacks, Northeastern has yet to be publicly singled out.

Shortly after President Donald Trump began his second term, Northeastern published its “Navigating a New Political Landscape” FAQ page, which has been continuously updated to address the rapidly-changing realm of higher education. The “answers” are not signed or attributed to any university officials.

Under its “Research and Teaching” section, the university addressed concerns around academic freedom, which has for months sparked debate among faculty. The conversation around freedom of speech on campus predates the second Trump

administration and prompted the formation of an academic freedom committee within Northeastern’s Faculty Senate in November 2024.

“As described in the Faculty Handbook, the university does not impose limitations upon the freedom of faculty members in the exposition of the subjects they teach,” the Feb. 12 update to the FAQ reads. “Faculty members are always expected to exercise appropriate discretion and professional judgment in all facets of their teaching and research and abide by Northeastern’s policies.”

How these students are empowering pediatric patients — ‘one story at a time’

At Pages for Pediatrics, the mission is clear: create relatable stories for children that simplify complex health conditions and encourage self-acceptance.

Sia Shah, a fourth-year health science major, is the co-president of Pages for Pediatrics at Northeastern. Pages for Pediatrics, or PFP, is a national nonprofit focused on empowering pediatric patients “one story at a time” by creating children’s books, connecting with universities and donating their illustrated stories nationwide. Northeastern is one of three universities with a PFP chapter.

Through illustrated stories, children can learn about their diagnosis in a more comforting and simplified way, generating a sense of security and empowerment.

“When kids are first diagnosed with something and they don’t really know what’s going on, a simple book puts words in terms they understand,” Shah said. “I’ve

seen patients that I work with read those kinds of books, and it really helps them just feel so much more comfortable in their condition.”

Amy Yan, a 2025 Northeastern graduate, learned about PFP through a close friend in the University of California, Los Angeles, or UCLA, chapter. During her sophomore year, Yan and the former co-president of the club Shriya Karthikvastan decided to bring PFP to Northeastern. Yan said she felt like there were no clubs that “piqued my interest in terms of hobbies and careers, because I was a pre-med student, and I really wanted something that would be able to kind of mesh those two interests of mine.”

Yan worked with Karthikvastan to spread the word about the organization. They communicated the “basic premise of our mission, which was to be a club that writes, illustrates and produces children’s books about different medical disabilities and illnesses to fight against pediatric stigmas,” Yan said.

After assembling an executive board, the club started meeting in fall 2024. Yan’s overall goal was to set a good foundation for the club and to gather a “great group who were just as passionate” as her.

“Everyone definitely surpassed my expectations. They were such go-getters and started their own goals for their own committees,” she said.

Now, the club is led by Shah and third-year cell and molecular biology major Kaitlyn Chan. It has four committees: writing and editing, creative design, finance and fundraising and external affairs and marketing.

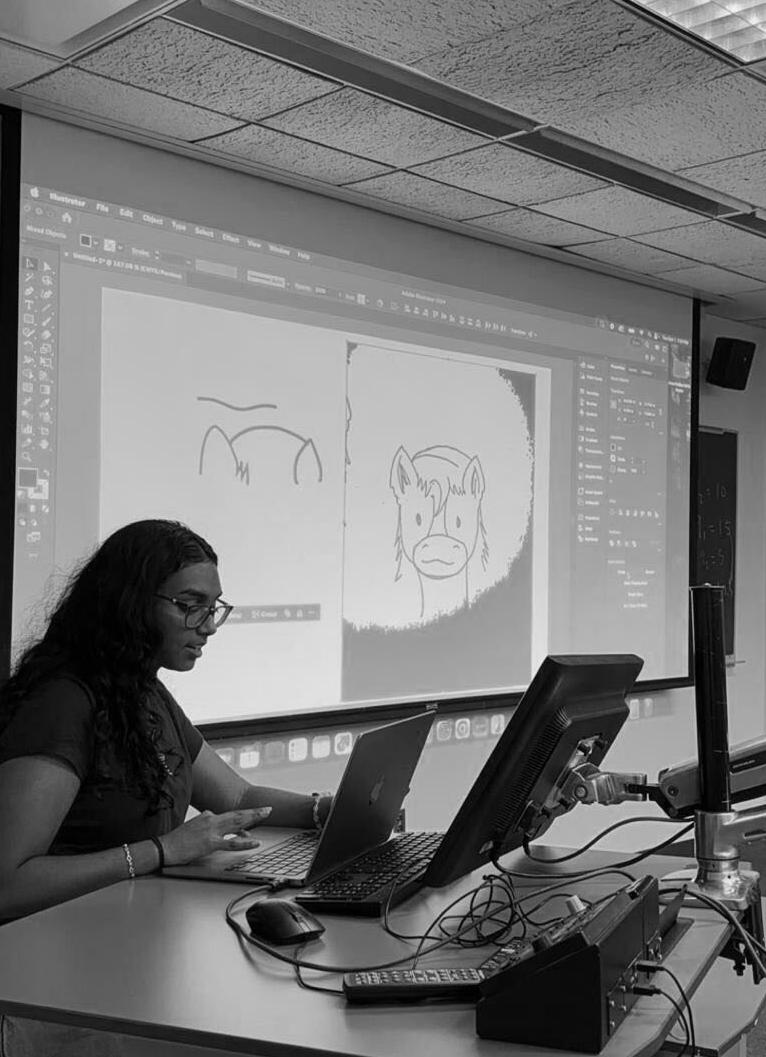

Northeastern PFP’s first book is set to be published this fall. The story centers on Henry, a horse with scoliosis who enjoys daily rides with

his owner, a girl named Scarlett. As Henry’s condition worsens, his curved back makes riding difficult. Cooper the Camel helps him understand that scoliosis doesn’t have to hinder him. With support from a special brace

while avoiding oversimplifying or downplaying them.

“We navigate a lot of different drafts just to make sure we’re not emphasizing things in a way that is going to be offensive to some families,” Shah said, adding that the team also relies on support from physicians and pediatric organizations.

Once published, books are distributed to hospitals and schools.

PFP members read the books to children in community centers and at Northeastern’s Russell J. Call Children’s Center daycare.

A testimonial from the Orthopaedic Institute for Children at UCLA described how a 4-year-old patient didn’t want to leave the center until she finished reading “Tommy the Twig” with a volunteer. The story follows a tomato plant who embraces his differences and finds inspiration to grow addressing the stigma around prosthetics.

Both Shah and Chan have previously worked in pediatrics, something that drew them to PFP’s mission.

designed for horses, Henry regains his confidence. During a competition, Henry meets a young girl with a similar condition and realizes that scoliosis is just one part of who he is and doesn’t define him.

“Two of our club members have that condition, so it’s going to be super exciting to write a book where we can incorporate our personal struggles into it,” Shah said.

Each PFP chapter chooses topics to write about every spring semester. Brainstorming involves extensive research to ensure the book is suitable for a pediatric audience. Once the topic is chosen, the manuscript is developed with a focus on making complex conditions understandable to children

“The reason that I was super interested in joining is because my grandfather actually worked with a bunch of people to set up a hospital in India for kids with cerebral palsy, and so, growing up, I’d go there once a year and see the impact that healthcare has on kids and families with disabilities,”

Shah said.

Chan’s interest stemmed from witnessing her childhood best friend’s cancer journey.

“For me, one of my childhood best friends actually had thyroid cancer, so seeing her go through the process and struggling with the trials and tribulations of the whole thing really drew me to Pages for Pediatrics,” she said.

Although Northeastern PFP doesn’t work directly with chapters

at other universities, it coordinates closely with the main nonprofit, which oversees all committees, provides specific timelines for completing projects and helps avoid topic overlap. So far, PFP has written and illustrated six stories addressing stigmas and misconceptions around pediatric conditions, helping children feel empowered. Ultimately, PFP emphasizes diverse representation in its approach to crafting new stories.

“Any children’s book where I really felt myself represented meant so much to me,” Chan said.

In the future, the Northeastern chapter hopes to write stories in more languages and bring stories to other countries. But, for the time being, the club is looking forward to their first published work this fall.

“We’re really highlighting diversity to make everyone feel like they have a place in a story,”

Chan said.

MORA PEUSNER DACHARRY News Correspondent

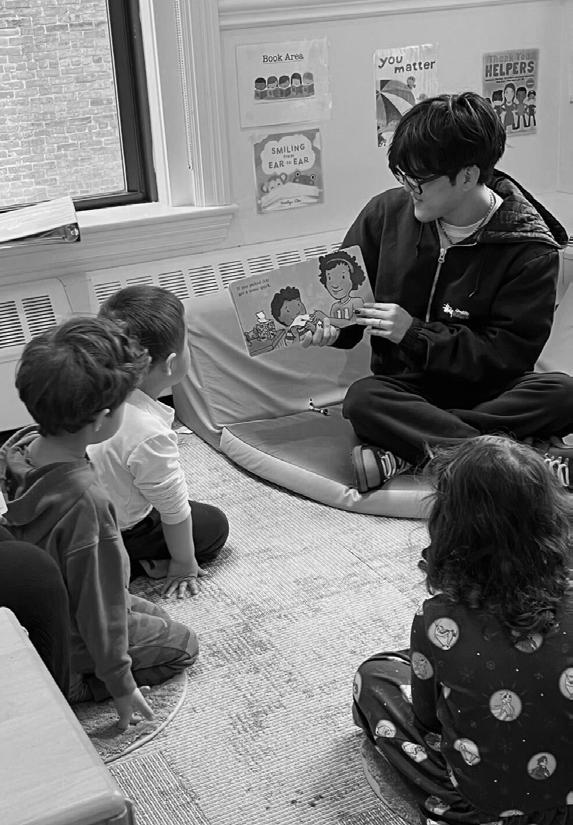

Club members read a storybook to children. Amy Yan started a chapter at Northeastern after hearing about the program from a friend in PFP at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Photo courtesy Sia Shah

A PFP club member sketches out a horse on Adobe Illustrator. The club met to develop a manuscript, storyboard and illustrations throughout the spring semester.

Photo courtesy Sia Shah

Children gather around a PFP member and eagerly listen to a story. University PFP chapters donated over 100 storybooks to hospitals and schools.

Photo courtesy Sia Shah

The U.S. flag waves on top of Ell Hall May 28. The university was ranked low in a free speech advocacy group’s 2026 report.

Photo by Margot Murphy

From Newcastle to New England: Sam Fender’s ‘People Watching’ tour hits Boston

ABBEY CONLEY News Correspondent

Roadrunner welcomed North Shields’ alt-rock singer Sam Fender for

packed shoulder-to-shoulder in Brighton’s main venue.

Young Jesus, an indie-rock band from Chicago, opened the night. Despite its name, the band’s only worship

Guinness t-shirt and Adidas trainers, Fender looked right at home with the rock-and-roll crowd of Boston. Met with roaring applause, it was obvious

that Fender’s first show in Boston was long overdue. He opened with “Angel in Lothian,” an indie-rock ode to his home country and childhood, off of his sophomore album, “Seventeen Going Under.”

Wrapping up his first song, Fender was met by a roaring crowd and enthusiastic screams. Despite being a newcomer, he quickly earned brownie points with the Boston crowd by chanting “Eff the Yankees” before his next song.

The crowd loved his follow up song, “Will We Talk?” a pop number from one of his earliest albums, “Hypersonic Missiles.” Lights flashed as he danced onstage with his band and played an impressive guitar solo, which he called an unflattering imitation of Prince.

“Sorry for the shite Prince impersonation. Good band name, though, ‘Shite Prince,’” he joked with the audience.

Between each song, Fender cycled through his collection of at least eight guitars, ranging from a standard acoustic to his custom Fender Jazzmaster, painted black and white as a

nod to his favorite football team back home. As a die-hard Newcastle fan, football served as a recurring motif throughout the set, and many fans mirrored his love for the team by donning their own jerseys.

The band continued to enthusiastically play a few more songs, with Fender cracking jokes and bantering with fans in between each. Before playing “The Borders,” one of his more emotional rock pieces, the spotlight moved away from the singer and to the audience. A young fan in the front, holding a poster asking to play guitar for “The Borders,” was then brought on-stage for a special guest appearance to accompany the band. Following cheers from the audience, Fender and the fan jumped around the stage as if the bit had been rehearsed, making the performance feel less like a concert and more like friends having fun.

Continuing the setlist with “Crumbling Empire” and the tour’s namesake track “People Watching,” the connection between the fans and the music was tangible. Halfway through the night, Fender said the band was

going to “try something different” and surprised fans with a deluxe album announcement and an unreleased song titled “Talk to You.”

At the end of the gig, Fender and the band exited the stage to the sound of fans chanting the ending lines of “Seventeen Going Under” before eventually returning for an encore. Fender sat down at a piano and captivated the audience with a performance of “The Dying Light,” another emotional ode to the North Shields town that raised him.

In an explosion of lights and electric guitar, Fender ended the night with a climactic performance of “Hypersonic Missiles,” the raw, controversial track that named him one of the U.K.’s greatest up-and-coming songwriters back in 2019.

The “People Watching” tour was a wild ride for both die-hard fans and rock-and-roll enthusiasts alike. Fender’s live performance is a can’tmiss show for those who enjoy the alternative, Brit-rock scene. If the fans have anything to do with it, Fender’s first time in Boston most certainly will not be his last.

‘We’re finally talking about this’: MFA’s Kinfolk Courtyard reclaims Black folk music traditions

Black folk musicians gathered Sept. 12 for “Kinfolk Courtyard: A Celebration of Black Folk,” but what took place on stage was far more than a celebratory night of music. All at once, it was a reclamation of traditions, a rejuvenating call to action and a cry of disruptive remembrance.

Hosted in the Norma Jean Calderwood Courtyard at the Museum of Fine Arts, or MFA, attendees reflected on the history of Black folk music while honoring the origins of art that has long been co-opted by white artists.

“I think it’s really important that we’re finally talking about this,” said Jake Blount, a folk musician based in Providence. “I think it’s really important that it’s also happening in Boston, right? So much of the distortion of the Black folk tradition was via blackface minstrel shows that were most popular in the urban North. Boston was an epicenter of that, so there’s a corrective thing to be done here.”

Blount was one of several starring musicians at “Kinfolk Courtyard” who called attention to the time and place of the event. The MFA concert was directly tied to an exhibition spotlighting the work of Minnie Evans, whose art reflects her ancestors’ experiences in enslavement and her own upbringing in the South during the Jim Crow era.

“It’s really nice for us to be able to tangibly tie the art that’s going on and the music together,” said Kristen Hoskins, director of public programs at the MFA. “We’ve done connections to music before through exhibitions, but, really, this is the most intentional that we have been, and [it’s] nice for us to be able to call attention to it in that way.”

The night’s artists performed as part of the We Black Folk festival movement, which aims to reclaim and redefine the narrative surrounding Black folk music while platforming Black folk artists who might otherwise be marginalized. As the movement’s founder Cliff Notez sees it, redefining the narrative needs to extend beyond folk music to Black art in all forms.

“There was some erasure that happened with Black folks in folk music,” Notez said. “So, we are thinking about, like, what is the community that happens within Black folk arts as a whole? How do we bring them together, and how do we amplify them so that it can continue to grow?”

As an artist, nothing is more important to Notez than exploring different genres to convey his personal and racial identity through his music.

Right from the start, he unleashed a sound that disobeyed the limitations of traditional genres, but he struggled with the press continuing to label him as solely a hip-hop artist.

“I was like, ‘All right, I’m gonna show you all something,’ and then I was like ‘Let me go to the thing that I think is the furthest from what hip-hop is,’” Notez said. “‘Let me go to folk, and then also in that, let me show them how close folk music is to hip-hop at the same time.’”

Some of Notez’s biggest influences, he said, include Michael Jackson, Prince, Marvin Gaye, Jay-Z and Nina Simone, all culturally ubiquitous Black artists. Crucially, they all carry the legacy of being adept artistic shapeshifters, and for Notez, that resilient passion rings true. Though being a Black musician comes with its own set of challenges, he said the music industry’s tendency to generalize and label artists crosses racial barriers.

“I think Black folks get the brunt

of it really easily, but I think it’s the entire industry right now, where everybody’s looking for some way to classify and put somebody in a box to have an understanding of them, which doesn’t create an opportunity for folks to be the complex beings that they are,” Notez said.

Notez has partnered with the MFA for over a decade now, and it’s consistently been a space where he can flourish artistically while making audiences reckon with the complex and rocky history of Black folk music.

“We are just so happy that we can be long-time friends and collaborators, to be able to give a platform and give space knowing that Cliff is really galvanizing this through history,” Hoskins said.

Alongside a lineup of We Black Folk musicians, including Naomi Westwater, Zion Rodman, Stephanie McKay and Chris Walton, Notez performed songs by some of the most enduring Black artists of the 1960s and 1970s. Getting warmed up for the night, the crowd joined in singing along to covers of Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Bill Withers’ “Lean on Me” and Stevie Wonder’s “Isn’t She Lovely.”

Indie folk singer-songwriter Grace Givertz then took the stage with a series of original songs played solo on her banjo. For Givertz, the banjo is a deeply personal instrument due to its ties to her racial identity and ancestry.

“I didn’t realize how much rich history it had as a Black instrument,” Givertz said. “When I first started playing it, I felt a really deep connection to it, and then I figured out why — because it was very ancestral and very spiritual for me.”

Givertz is currently preparing to release a new album, “Kinfolk Courtyard.” The current political climate breathed new life into some of her older material, she said. Nowhere

was this more evident than in her song “America,” which she wrote in 2019 about the immigrant experience. Givertz’s grandmother is from Bermuda, and her father is from the United Kingdom, so she approached the lyrics and messaging of “America” in a way that felt honest to her.

“Growing up with an immigrant parent who is white is a completely different experience, and I recognize that entirely, but it just goes to show that we all are impacted in our lives by immigrants for the better, and I think it’s just important that we remember that we are also visitors here,” Givertz said.

Blount then bridged Notez’s and Givertz’s ideals with spirited performances of folk songs alongside co-performer and Nashville-based songwriter Ethan Hawkins. Blount had a seemingly endless treasure trove of obscure folk music to share, with a few well-known traditionals sprinkled in. This wealth of undiscovered gems, he said, is the gift that the connections he’s made in the folk scene have given back to him.

“I think things find their way to you,” Blount said. “I’m getting recordings from people that they have had on a cassette tape for 30 years or whatever that, like, one else my age, at least, heard, and I learn tunes off of that. I’m not seeking the rare things, but people just show up and

In the context of Black folk history, the memories that are dredged up with the music run deep for Blount. In an interview with The Huntington News, he recalled taking family trips to his grandparents’ farm, which resides on the same land where his ancestors were once enslaved. Experiencing that history of enslavement so starkly and processing the generational trauma it caused showed Blount the role that folk music in its original form played for Black identity.

“The music is the way that my ancestors tried to stay two steps ahead of a system that was trying to take all of that art and life and creativity away from them,” Blount said.

Though many of his main musical influences are white, he said it’s Black artists who have had a formative impact on his mission and ethos both as an artist and human being. Just like for Notez and Givertz, there’s a foundational understanding for Blount to reconcile with as Black folk music is rediscovered and redefined.

“It’s not just like I’m cribbing licks from you or I sound a lot like you, but, like, I see the world through that lens,” Blount said. “The

DARIN ZULLO News Staff

Sam Fender plays the guitar. The Sept. 17 performance was Fender’s first time playing in Boston.

Photo by Margot Murphy

An audience gathers to listen to the Kinfolk Courtyard event. Speakers highlighted a call for Black remembrance and celebration through music, art and conversation.

Photo by Darin Zullo

From cliff to crown: Boston hosts cliff diving world championships

A cool Boston breeze swept across an athlete’s skin as he gazed roughly 27 meters down into the dark water. With a quick breath and adjustment, he leapt from the platform, executing flips and athletic turns before narrowly splashing into the Seaport Harbor.

The anticipatory silence dissolved into a roar of cheers and applause, echoing against the Institute of Contemporary Art, or ICA, where sport enthusiasts and onlookers gathered to watch the Red Bull World Cliff Diving Championship Sept. 19 and 20.

Boston is no stranger to the cliff diving series, having hosted preliminary rounds six times since 2011. But this was the city’s first time hosting the championship, and it welcomed the 24 competitors and hundreds of spectators with blue skies.

Visitors from around the world flocked to Boston to witness the oldest extreme sport in history. Supporters from Maine to Canada — like competitor Molly Carlson’s mother Kathleen Trivers — were ecstatic to see the large crowds cheering for the divers.

“Meeting people from Boston, they’re just so welcoming and lovely,” Trivers said. “Yesterday, there was a whole lineup to meet Molly afterwards and we got to meet so many Bravies [Molly’s fanbase] and that was just such a great moment for us.”

Cliff diving originated in Hawaii,

known traditionally as “lele kawa,” which translates into “leaping feetfirst from a high cliff into the water without making a splash.” What was once a way to represent power and balance is now also an extreme, competitive sport that brings people together worldwide.

The championship competition, started by Red Bull in 1997, consists of a women’s and men’s category with eight professional divers and four wildcards. Wildcard divers are newcomers who compete for a permanent spot in next year’s competition. Each dive is scored on a 10-point scale and judged on diving position, components, direction and, finally, entry into the water.

Divers not only have to be aware of their choreographed dives but have a disciplined body and astute sense of self in the air in order to safely and elegantly land in the water. Boston is a relatively tame location in comparison to the rough waves of Ireland or Spain’s expansive cliffsides, but it still requires its own technique.

“Boston’s very predictable. It’s a harbor, there’s not a lot of big waves, there’s a platform, it’s not a cliff,” Trivers said. “But you never know. Two years ago and it was pure Boston weather — raining, cold, windy — so you never know what the weather’s going to be.”

After each athlete was introduced on a live jumbotron feed, a “ding ding ding” played, signifying the athlete was ready to jump. The audience quieted to allow them to concentrate. After a couple tense seconds, the diver took off before hitting the water with a cracking splash.

Watching the professionals elicited gasps from audience members, amazed by each performance.

“It’s insane,” said Lucas Short, an electrician from Maine. “They’re taking risks every single time they do it. They literally could get hurt every single time.”

Short found out about cliff diving from Carlson’s YouTube channel and fell in love with the sport. He, like many other fans, lined up to cheer on Carlson and the other competitors.

The entirety of the Seaport area was covered in spectators lining the docks from the ICA to sitting in parked boats to view the competition.

“Watching it [cliff diving] in person is so much better than watching it on video,” Short said. “Seeing how quiet it gets, all the nerves everybody has before every single dive is really incredible.”

After the final, death-defying dive, Australian Rhiannan Iffland and French Gary Hunt took home the 2025 King Kahekili trophy with a total score, across all of the series’ competitions, of 62 and 49, respectively.

Audience members, like Short and Trivers, lingered after the competition to meet their favorite divers and congratulate them. Others, like Brielle Almonte, walked away feeling a sense of community and renewed awe.

“After it all, I wanted to jump in the water,” Almonte, a software engineer who lives in Boston, said. “If someone gave me the opportunity to go jump off that right now and told me how to do it, I would do it. It was an inspiring, really cool event. I’m excited to come back next year.”

Photo Editor and Photo Staff

A diver aims for the water Sept. 19. Some divers started their dive with a handstand on the platform. Curtis DeSmith

USA’s Lisa Faulkner throws an “OK” sign after surfacing from the water Sept. 20. Each diver communicated with small hand waves to indicate their safety status and readiness. Margot Murphy

Italy’s Andrea Barnaba chats with Red Bull media after completing a dive Sept. 19. After diving, competitors warmed up in a portable hot tub on a nearby dock. Curtis DeSmith

Judges raise their score cards after a dive Sept. 20. The judges were selected from a pool of 12 based on their availability and geographical location. Margot Murphy

A diver twists in the air Sept. 19. Scuba divers waited at the bottom of the jump and lightly splashed the area in order to help the competitors see the water. Curtis DeSmith

A diver twists in the air Sept. 20. Male competitors jumped off a 88foot high platform while women competitors jumped off a 69-foot high platform. Margot Murphy

A diver flips in the air Sept. 20. Margot Murphy A diver twists Sept. 19. Curtis DeSmith

MARGOT MURPHY AND CURTIS DESMITH

Are performative males the only ones method acting?

beyond the screen? Some say yes.

He has a mullet or a bleached buzz cut — no in between — and probably a Letterboxd account with an ode to “Interstellar” as his top review. He drinks specialty tea lattes with dairy alternatives. He wears Japanese denim and a Carhartt jacket. He listens to music exclusively through wired headphones or on vinyl in the comfort of his Clairo-postered studio apartment. Who is he? The man, the myth, the urban legend: the performative male.

Famously disingenuous in his self-presentation, this male archetype tailors his image to appeal to women, curating his interests to come across as profound and cerebral.

Though popularized late this summer, the performative male has always existed in some shape or form online. One thing remains constant — he is persistently characterized by his opportunistic embodiment of femininity.

At the dawn of the internet, there was the so-called “nice guy.” Later, 2019 birthed the “softboi,” who wore pearl necklaces and discovered empathy. Jokes cautioning against the Radiohead-listening “male manipulator” appeared in the cultural zeitgeist, and women online teased about grown men having revelatory thoughts they’d had at 11. Is this shapeshifter, however, of any real consequence

“I don’t really mess with matcha, so I think I’m ineligible,” said Brian Thomas, a fourth-year economics major at Harvard University.

Thomas has never been labeled performative himself but observes it as a phenomenon among his peers to garner female attention.

“They want some play. You know, it’s been a while for some of them, and they think this is the path,”

ceived by others… It’s never going to be solely a manifestation of your selfhood,” said Jess Montgomery, a fourth-year landscape architecture major at Northeastern.

Montgomery further alluded to the teachings of feminist philosopher Judith Butler, who originated the idea that gender presentation is a “stylized repetition of acts.”

“Gender is a performance. Every day, when we wake up in the morn ing, we decide how we are going to

Thomas’ belief isn’t unfounded — research suggests this persona has tangible appeal. In a 2024 study published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, women ranked feminine male profiles as more romantically appealing than masculine ones, indicating that the so-called “performative male” may have better long-term female relationship prospects.

“Authenticity, when it comes to social presentation, is always really difficult because when you’re presenting yourself, it’s to be per-

time expenditure, citing hobbies like crochet that take a concert ed amount of effort, and are, by default, unperformable.

“You have to build up that skill,” Montgomery said. “Like, it’s obvious that you’ve sort of invested.”

Elliot Phifer, a second-year design major at Northeastern, argues that there are two brands of the performative male — the carica ture and a more well-intentioned, true-to-life version.

perform gender,” Montgomery said. With this in mind, it’s not the loafers, the tote bags or the film cameras that make Montgomery weary — it’s when she can tell that someone’s just hopped aboard the proverbial bandwagon.

“I think it’s immediately obvious when you’re talking to somebody and they’re sort of picking through interests and clothes and hobbies and adornments because they’re of the moment,” Montgomery said.

For Montgomery, the difference between performative and authentic self-expression also lies in

fied version that you see online. It’s like the tote bag and the Clairo vinyl and the matcha and the Labubu. But I think there’s the more real version, which is where it’s not as much of a hyperbolic exaggeration of a person,” Phifer said. “I think the real performative male is much more subtle, and it’s probably not very much of a conscious thing.”

Has Phifer himself ever fielded accusations of performativity? “All the time. My friends say that to me all the time because of how I dress and who I listen to,” Phifer

said. “And because I enjoy a matcha every now and again.”

Phifer is able to take the jokes in good faith because they’re just that — jokes. He would only take offense if they were meant as a more serious moral indictment, he said.

“I feel like that would be a little hurtful because I really do just enjoy a lot of these things,” Phifer said. “And so to be called performative [in that sense] implies that you’re in some way deceiving.”

Across college campuses, the performative male has become such a phenomenon that students have started holding performativity contests, including at nearby institutions like Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard and Brown University.

Now, there are posters around Northeastern advertising a contest slotted for Sept. 27 at the Boston Common, promising a $100 prize for the winner and Labubus for contestants who come in second and third.

“People have been telling me to join,” Phifer said jokingly. “I will not be … If I do well, I’m hurt, right? Because nobody wants to be that. And then if I don’t do well, I’m also hurt because, come on — I want to do well. I want that Labubu.”

Unconsciously or not, a little performativity lives within everyone.

Phifer doesn’t know anyone participating in the contest, but, “Maybe I’ll know him when I see him,” he said.

Photos by Margot Murphy and Aya Al-Zehhawi

Graphic by Sree Kandula

EVENT CALENDAR

SATURDAY, SEPT. 27

Women’s ice hockey vs. Concordia

2 p.m. - 4 p.m. at Matthews Arena

Admission: Free with Husky Card

SUNDAY, SEPT. 28

The Allston Village Street Fair

12 p.m. - 6 p.m. at 101 Harvard Ave.

Admission: Free

FRIDAY, OCT. 3

Fall Fest on The Greenway

4:30 p.m. - 8:30 p.m. at Rowes Wharf Plaza

Admission: Free

SATURDAY, OCT. 4

Men’s ice hockey vs. Holy Cross

7:30 p.m. - 9:30 p.m. at Matthews Arena

Admission: Free with Husky Card

SATURDAY, OCT. 11

Men’s soccer vs. Monmouth

1 p.m. at Parsons Field

Admission: Free

Amelia’s Cluck & Smash: the makeover of the well-known taequeria franchise

KAYLA GOLDMAN AND PALOMA WELCH News Staff

As Northeastern students return to campus for the fall, a new business with a familiar name has caught everyone’s eye.

Amelia’s Cluck & Smash, formerly Amelia’s Taqueria, reopened in June on Huntington Avenue with a brand-new American-inspired menu featuring burgers, hot dogs and more. After the rebrand, which took place in 20 days, business had a naturally slow start due to the lack of students in Boston. However, the start of the school year brought a wave of new customers, skyrocketing sales almost overnight.

“I was always impressed by Sept. 1, how the flood of students come to Boston, and how active and vibrant the community gets,” said Amelia’s Cluck & Smash owner Amir Shiranian.

Shiranian attended Boston University for a master’s degree in biomedical engineering and the University of Massachusetts Boston for business and finance. He designed hand-woven carpets for 22 years before opening Amelia’s Taqueria in 2013 and had no prior experience in the food industry.

ily located near college campuses, including Berklee College of Music and Boston College.

At the time of its opening, Amelia’s Taqueria on Huntington was the first taqueria in the neighborhood. Over the past five years, El Jefe’s Taqueria, Mamacita Mexican Comida and Anna’s Taqueria have opened and expanded the variety of Mexi-

chicken cuisine idea for the new restaurant. The idea was meant to satisfy what college students in the area love to eat, and Shiranian thought chicken and burgers were a good option.

According to its website, Amelia’s Cluck & Smash believes in providing food that is “bold, satisfying, and simple to enjoy,” and that “life’s too short for boring bites.”

Cus-

think we finished it before we even got to our room.”

The restaurant’s renovation also included a brand new Fenway Park-themed interior and a Cluck & Smash wallpaper created by Raha Shiranian, Amir Shiranian’s wife and business partner.

can-inspired cuisine on the street.

The original Amelia’s is located near Boston University in Allston, with the Huntington Avenue store opening a year later. Today, Amelia’s Taqueria has four locations, primar-

“I always say we were the first one to start taqueria on campus … we decided to be the first one to depart and then start our new brand,” Shiranian said.

When searching for a new idea for his business, Shiranian worked with consultant Bill Goldman, who helped create the burger and

tomers seem to agree.

“One day, me and my roommate were so hungry, and they were handing out free samples outside. So, we took one of the samples, which was fries and their sauce. I don’t know what is in it, but it is so good,” said Mariy Dudina, a second-year human services and psychology combined major. “We literally live right next to the building, and I

Amelia’s Cluck & Smash employees went through retraining to learn the preparation and presentation of the menu’s cuisine. In addition to the staff remaining consistent at this Huntington Avenue business, Amelia’s churros are still featured on the menu.

“Now we prepare everything, every single day, so everything is fresh,” said Darlyn Hernandez, a member of the Cluck & Smash team.

The week of Sept. 15, from Monday to Thursday, Amelia’s Cluck & Smash ran a $5 meal deal for hot honey chicken tenders, redeemable for Northeastern students with a Husky card.

“I don’t think there are that many burger places nearby, other than Five Guys … and Amelia’s has a good spot. There’s not as much competition as Mexican food,” said Daniel Dabagian, a second-year politics, philosophy, and economics student.

With the success of Amelia’s Cluck & Smash so far, Shiranian also hopes to grow this branch of his business into new locations.

“Well, change is always good in life, altogether. I believe change brings energy and also opens up different avenues,” Shiranian said.

Young adults analyze why Boston’s dating scene sucks

Indigenous Peoples’ Day at MFA Boston

10 a.m. - 5 p.m. at MFA Boston

Admission: Free

MONDAY, OCT. 13 Fall-O-Ween Children’s Festival

“Unreliable,” “nonexistent,” “superficial,” “transient,” “terrible,” “homogenous,” “bland” and “bad” are all adjectives that young adults living in Boston use to describe dating in the city. It is a widely held sentiment that Boston’s dating scene is abysmal.

As of this year, Boston has the second-highest rate of single people out of all cities in the nation, with 57.4% of Boston’s population not in a relationship and never married.

dating apps to meet people, most young adults have found they prevent genuine relationships from forming.

“The majority of people I know use Hinge and Tinder, and they call that dating. That’s not what I would call dating,” said Diego Gómez a third-year international business student at Northeastern who’s dated in Boston for two years.

“Everybody kind of commonly acknowledges that Tinder is just an app to go have sex. Hinge is just the same thing, except you take them out to dinner first.”

said Alexis Matthews, a third-year business administration major at Northeastern who’s dated in Boston for three years.

Gómez feels this may just be an excuse for nerves.

“I think dudes need to have the balls to go approach somebody and be like, ‘Hey, you’re really pretty, can I get your number?’

That’s gonna work like 75% of the time; the bar is so low here. For me, that’s gone pretty great. I don’t have Tinder and I feel spectacular,” Gómez said.

Now lies the problem of what happens once people do meet someone they like: Boston’s pervasive hook-up culture.

The expectation of sex or sexual activity is seen as nearly synonymous with going out with someone in Boston, young adults said.

Admission: Free FRIDAY, OCT. 17

5 p.m. - 8 p.m. at Charles and Beacon Streets

Boston is full of college students, making the average age of residents around 33 years old. People are young and attractive, and we are in a technological era where everyone is more connected than ever. So why is there a collective feeling that dating here is so difficult?

Approximately 53% of people aged 18 to 29 report using dating apps in the United States. Boston’s young demographic means that a significant number of people in the city are swiping, matching and rejecting each other, all without ever meeting.

Another aspect of Boston’s poor dating culture is that young adults like Schabenbeck, who are originally from larger cities, described Boston’s population as being uniform and unappealing. They find there’s a lack of people to approach, even if you have the conviction to do so.

“The avenue to dating was not the traditional first date romance, but you hook up with someone and then hope that they want to make you their girlfriend, which is such a passive and kind of tragic way of doing things,” said Maggie Filgo, a 22-yearold screenwriter in Los Angeles who dated in Boston for four years.

The Head of the Charles Regatta

7:45 a.m. - 4 p.m. on the Charles River

Admission: Free OCT. 17-19

Many students blame dating apps. From Tinder to Hinge, is a seemingly endless number of singles at the swipe of a finger. But having so many options is part of the problem, according to students.

“When you look at social media and the accessibility of dating apps — how easy it is to have so many people, in theory, at your disposal — people are just so picky. And then even when they have someone, they don’t treat them right, because there’s always another option,” said Anushka Wadhwani, a third-year international affairs student at Northeastern who has dated in Boston for three years. Despite a common reliance on

“There’s a lot of fear with regard to meeting people in a romantic sense or advancing relationships,” said Collin Schabenbeck, a thirdyear international business student at Northeastern who’s dated in Boston for two years.

There’s also seemingly some wires crossed. Women are waiting for men to approach them, and men are concerned that this will come across as “weird” or “creepy,” according to young adults living in Boston.

“In Boston, I feel like there isn’t really much of a culture of people coming up to other people. I definitely know a few guys who’ve said that they don’t want to approach girls and come off as a creepy dude,”

“I sort of expected to meet a lot of different types of people when I first came here, so I was surprised by how many people are actually very similar, and not necessarily in a bad way, but not really in a good way either,” Schabenbeck, who is from New York City, said. “I think there’s very little diversity of thought and open-mindedness.”

Avalon Marandas, a third-year international affairs and criminal justice combined major at Northeastern who’s dated in Boston for three years, said that Boston’s corporate culture projects a superficial image that many people try to adhere to, creating a seemingly small and homogenous dating pool.

Coinciding with Boston’s hookup culture is a feeling that romance is diminishing throughout the city. Young adults are not experiencing the world of dating in the ways older generations might have. There’s no need to buy a bouquet of flowers when you can just send a drooling emoji.

“The guys typically are not taking girls out to dinner or doing nice things. It’s usually ‘Do you want to come over? Do you want to watch a movie? Do you want to do something indoors?’ Which usually sets it up for sex,” Marandas said.

The culmination of technology, hook-up culture and maintaining a sense of casualness has left young Bostonians disheartened by the dating scene.

“Nonchalance will be the death of us all,” said Nathan Barth, a fourthyear computer science student at Northeastern who’s dated in Boston for three and a half years.

File Photo by Jessica Xing

Photo by Elizabeth Scholl

Photo by Asher Ben-Dashan

Photo by Chloe Makhlin

DEVYN RUDNICK News Staff

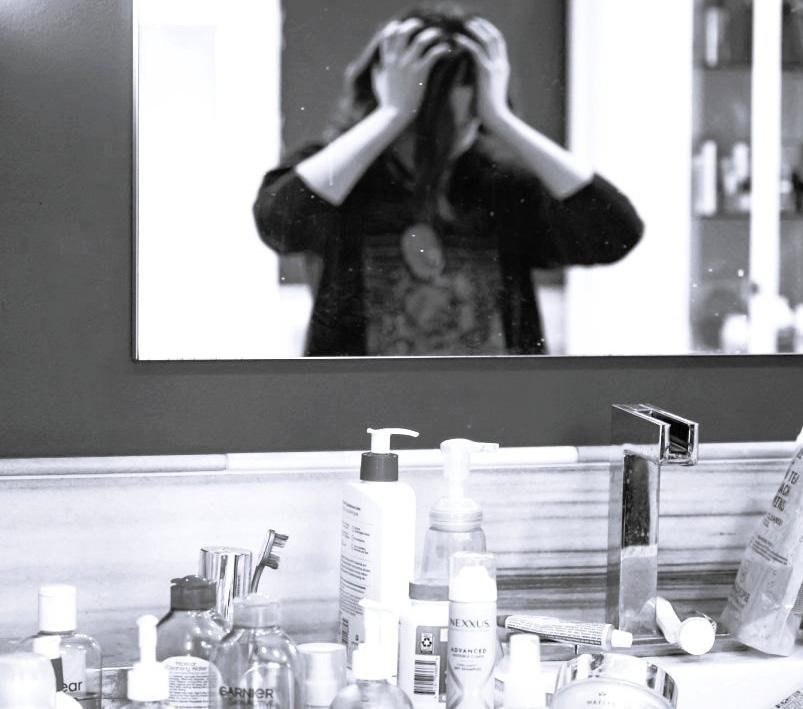

With Matthews facing demolition, club sports are left without home ice

FRANCES KLEMM AND SIERA QOSAJ

News Staff and Deputy Sports Editor

When Danielle Mazo, a fourthyear business administration and criminal justice double major, joined Northeastern’s figure skating team in 2022, she said the end of Matthews Arena already felt near. Now, as Mazo steps into the role of president for the 70-plus-person team, the looming prospect of being an ice-based team without home ice is daunting.

“We are losing something that’s very valuable to us, but that doesn’t mean that our team isn’t still going to be valuable,” Mazo said. “We just have to find how to navigate these next few years without Matthews being our core center.”

According to an email sent by Northeastern’s club sports program to leaders of club sports teams, Matthews will be “unusable” after varsity hockey’s final home game scheduled for Dec. 13. The three ice-based club teams that regularly practice at Matthews — figure skating, men’s ice hockey and women’s ice hockey — will need to find rinks

to play on until the summer of 2028, when Northeastern has said the new athletic facility will be finished.

Both men’s and women’s varsity ice hockey programs are also increasing the number of fall home games this year, making it more difficult for club teams to continue with their usual fall schedule.

Although the three teams were unsure of how they will afford the loss of Matthews Arena for almost three years, the Northeastern Athletics department has now given each a budget that will cover “up to probably five hours of ice a week,” Mazo said.

major and president of the men’s club ice hockey team. “We were hoping to maybe get like 50% subsidization.”

After the funding question was answered, all three teams’ leadership

puter science and biology combined major and vice president of the men’s club ice hockey team. “[Matthews Arena is] in a really good location.

“We wouldn’t have to spend extra than what we normally spend, which is awesome. And the same goes for the [other] two teams, which was way more than we were expecting,” said Kyle Wilson, a fourth-year business administration

expressed lingering concerns that the change to off-campus ice will decrease player attendance.

“It’s going to suck having to play in a different rink off campus,” said Brendan Friday, a third-year com-

It’s by where everyone lives, so you don’t have to go far to practice or play. Once it’s gone, it’s going to suck because we’re going to have to drive everywhere to practice.”

Students on co-op may have a more difficult time accounting for additional travel time in their busy schedules, said Dani White, a fifth-year behavioral neuroscience major and co-president of the women’s club hockey team.

Matthews’ location is just five minutes away for players living on campus.

Now, the five hours a week demanded from the sport will likely turn into around 10 hours just to account for transportation, White said.

Team leaders are also now responsible for coordination with external rinks.

“I still have to contract with the external vendors. The new finance system is tricky to deal with, with invoicing and all that, so there’s lots of steps still to go, but we’re making progress,” Wilson said.

Both men’s and women’s ice hockey club teams attended nationals in recent years. The men’s team was ranked third in the Northeast region at the end of the 2024-25 season, and the women’s team was ranked first in the same category.

The figure skating team placed sixth out of the 37 teams in the 202425 Northeast Intercollegiate teams. Now, it will be up to the team’s leaders to maintain enthusiasm for their sports amid the disruption.

“I think it’s going to be inconvenient for everybody, but as long as we’re all in it together, it’s a little bit better,” Wilson said. “Things can always change, but for right now, I think we’re in a good spot.”

“Obviously, school comes first, and that [includes] co-ops, which is going to be really tough,” White said. “It just makes [club hockey] a way bigger commitment.”

WNBA players fight an off-court opponent

professional sports leagues, including the NBA.

The 2025 WNBA All-Star Game in July drew a sold-out crowd and more than two million TV viewers, but before tipoff, the players shifted the spotlight to an issue bigger than the game. During warmups, every All-Star wore a black shirt with the message, “Pay Us What You Owe Us.” Their message was clear: there is an unacceptable pay disparity between male and female players in professional basketball.

During the trophy presentation, the then-Washington Mystics guard Brittney Sykes appeared on national broadcast holding a sign that read “pay the players.” Even fans in attendance started a “pay them” chant. These demonstrations came just two days after more than 40 players met with league officials in the latest round of negotiations over a new collective bargaining agreement. The Women’s National Basketball Players Association opted out of the current agreement last year, and players have since been unhappy with the lack of progress in negotiations with the league.