Dear Friends of the MacLeish Scholars Program,

Somehow, MacLeish is five years old. Since 2021, the program has introduced 50 young minds to the joys and challenges of literary archival research. These students have collectively spent 2,000 hours working in library special collections and produced almost 1,500 pages of literary analysis. They have also crafted 50 unique artist’s books containing hundreds of pages of creative writing. They have lived at four different host universities and worked in twelve separate archives—before finding their permanent home at Yale’s Beinecke Library.

Free of cost to all participants, MacLeish has historically admitted over 40% financial-aid students. Around 50% have identified as students of color. The program has become incredibly popular among students, with acceptance rates hovering just over 15%. Finally, college outcomes have been robust, with over 50% attending Ivy League universities alone, a figure that is especially impressive given the diversity of admitted students.

The high interest in MacLeish has inspired Hotchkiss to build more programs in other

subjects. Of course, there’s Hersey Scholars, entering its fourth year, which takes students to Harvard, Boston Public Library, and the Massachusetts Historical Society to conduct archival research into history. This year we inaugurated a new program in the history of math and physics, based at Cornell. Next year, we are launching new programs in art history (Princeton) and environmental science (Yale). In the near future, nearly two thirds of all Hotchkiss students will apply to one of these programs and well over one third will participate in one before they graduate.

As MacLeish in particular has developed, it has begun to lead to impressive results. Some recent graduates are revising their papers for publication. Some have had their papers added to permanent collections at museums, libraries, and cultural institutions. More and more are giving public talks or participating in conferences to share their discoveries. Hotchkiss itself has created a digital repository to store the final papers— for all our programs— which includes listing the students’ work in WorldCat, making it accessible to scholars around the world.

I had the pleasure of

presenting at this year’s Maria Hotchkiss Dinner with two young alumni, one Hersey and one MacLeish. Both spoke about the impact of these programs not as one-off experiences but, rather, as something they’ve carried with them— as they’ve explored intellectual interests, picked courses, chosen majors,considered careers. Both spoke about finding the research and writing expected of them in college to be much easier for having completed their archival projects (and of missing archival study, which is not usually an option

for college students).

Most of all, both spoke with nostalgia for the joy and satisfaction they still take from looking back on their programs: the power of archival discovery, the adventure of piecing together findings, the camaraderie with others doing the same. For me, this gets at the heart of why we offer these: the recognition of joy in difficulty, the marriage of challenge and wonder, the finding of satisfaction through struggle. Here’s to the next five years.

Sincerely,

Jeff/Dr. Blevins

By ELLA GOLDSMITH

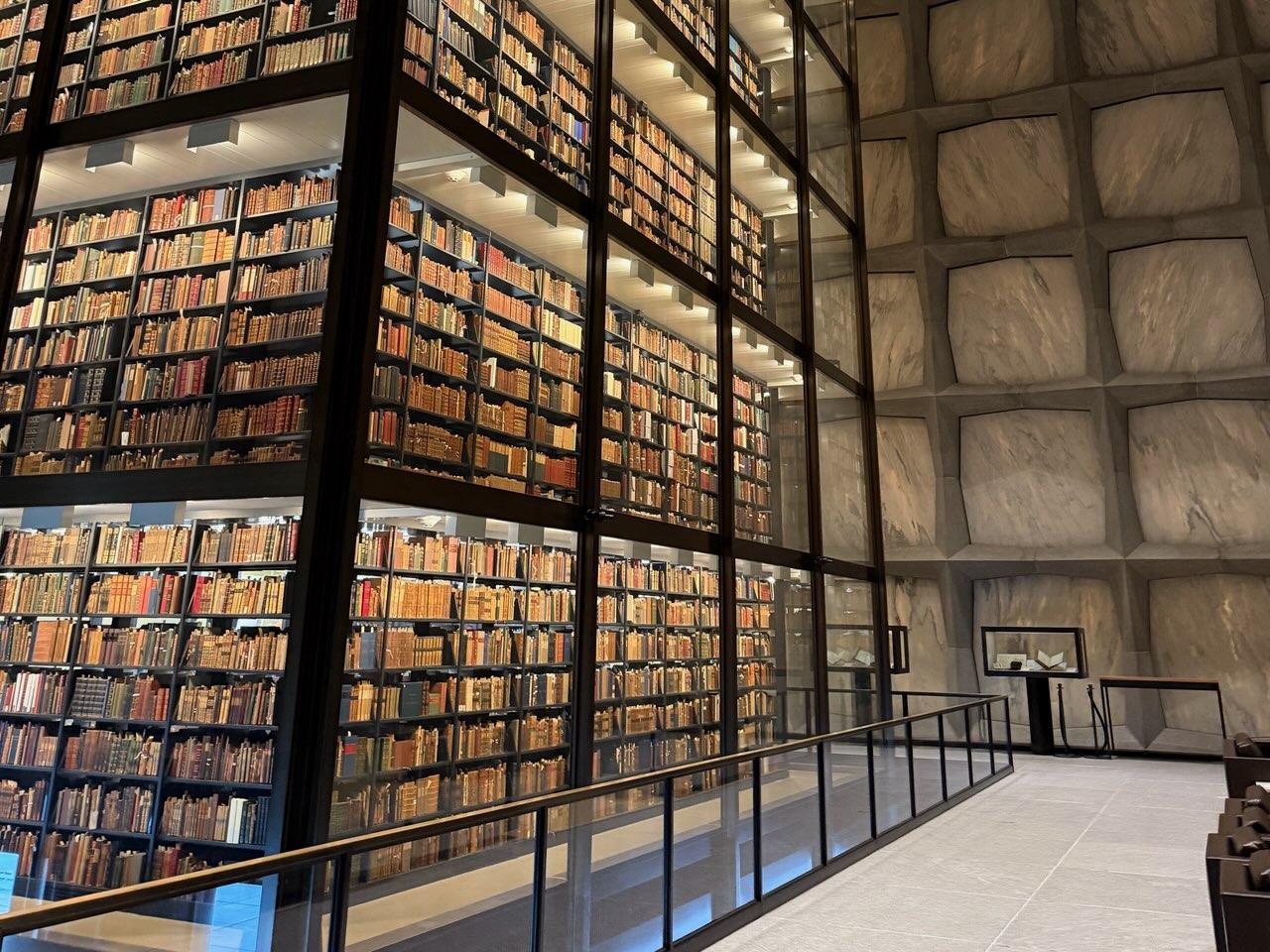

The MacLeish scholars’ schedule is packed with a wealth of creative writing, bookmaking, and study halls; but the most integralpartofourtimeat Yaleisspentinthereading roomattheBeineckeRare Book and Manuscript Library. Among Yale’s traditional Collegiate Gothic architecture, the Beinecke’s large façade is nothing if not striking. Its materials, marble and granite, have been milled to a thickness of 1.25 inches to allow light to permeate through the stone, giving the space a warm glow without damaging the delicate materials it holds. The Beinecke Library houses the university’s collections of rare books and archival materials, which attracts scholars across a variety of disciplines, including the history of science, the historyofthebook, political

history, Renaissance and eighteenth-century Europe,American literature, Western Americana,African American culture, and contemporary American poetry (just to name a few). Inside, roughly 180,000 rare books are kept in a glass-enclosed tower aboveground, while the reading room, the rest of the volumes, and archival materials—boxes of manuscripts, letters, notebooks, ephemera, etc.—are underground.

As highschool students, the MacLeish scholars are the exception to the leagues of professors, graduate students, and other experienced researchers that work in the Beinecke’s archives.

Each day, we spent the morning hours in the reading room connecting with our archives and, by extension, our authors. By looking through archival materials, we have gotten a first-hand look into the tedious processes of writing—seeing the seed or first mention of an idea that, through drafts and rewrites, becomes a publication within our literary canon. Over the course of our two weeks, we filed through the lives and work of our authors, gaining not only a more comprehensive understanding of their

careers, but also of the importance of keeping archival magic alive. Being able to spend time with these archival materials—from manuscripts to personal letters to drawings in the margins—has been such a special experience, inciting excitement and fueling our passion for the work that we will follow through the end of our Senior year. Personally, James Merrill’s emotions–passion for a new revelation, bored doodles in the margins, excitement about a pun he wrote–reverberated through his archives, reverberated through me as I got to know him through the pieces of paper he left behind. Scholar Lucas Ruiz said, “Looking at Jean Toomer’s large collection of journals allowed me to follow

his constantly evolving spiritual philosophies and understand him on a deeper level.”

None of this would have been possible without the amazing work of the Beinecke librarians and staff—who received, reviewed, and accepted our requests, transported and delivered our boxes, helped with any archival questions we may have had, and kept us, and our fellow patrons, safe. For this and all that they do, we give them our biggest thanks! And, of course, we would like to thank Dr. Blevins, Ms. Godbersen, and Neil for organizing the program, teaching and uplifting us, and providing a space, in their busy summer months, to help us grow and learn creatively. Thank you all for the best two weeks!

By ARIELLE SIBLEY-GRICE

On Friday night in New York City, the Scholars enjoyed a long-awaited formal dinner at the Century Association, a private social club founded in 1847 for authors and artists. With members that have included iconic figures such as Mark Twain and Edith Wharton, the club was the perfect location for an evening of literary conversation.

The dinner was hosted by Luke Pontifell, a member of the Association and founder of the Thornwillow Press in Newburgh, New York.

Dressed in formal attire, the Scholars arrived for a multi-course meal that began with a mocktail hour, during which they mingled with one another, met Mr. Pontifell, and learned more about the historic venue. As the meal progressed, the Scholars’ conversations ranged from their

research at the Beinecke to guessing what kind of dessert would be served (a peach tart and vanilla ice cream, as it turns out!).

The most memorable event of the meal was a series of memorized poem recitations from each Scholar, followed by readings of other works printed by Thornwillow Press and placed around the table by Mr. Pontifell. To conclude the evening, the Scholars toured the institution and saw a glimpse of the many collections of literature of art created by past and present members.

An opportunity to celebrate and discuss the intersections between literature and history, the evening at the Century Association was a fitting reflection of the MacLeish Scholars program and an exciting way to kick off the weekend in New York!

By SOPHIE KASPAR

On Sunday, June 15, after their quick trip to New York City, the scholars visited the Yale Center for British Art and the Yale University Art Gallery. There, they explored the intersection of literature and fine art through ekphrastic writing—creative pieces inspired by paintings and other works of art.

At the Yale Center for British Art, they met with curator and archivist Mr. Tim Young, who explained the process of selecting work for a collection, and recounted stories from his time at the Beinecke.

In the museum he gave the group a brief tour, sharing insight about pieces, special shows, and artists. He spoke of George Stubbs, an English painter who was among the first to study horse anatomy in depth and

depict horses with direct realism. An anatomically correct painting of a zebra by Stubbs serves as the emblem of the Yale Center for British Art. Along with their permanent exhibition, the museum had two temporary shows on Tracey Emin and J. M.W. Turner. Emin’s “I Loved You Until The Morning” was powerful and evocative, moving the scholars to craft vivid and emotional lines. The scholars’ imaginativework continued at the Yale University Art Gallery, holding a vast collection spanning from medieval coinage to Basquiats. The building itself reflected this blending of old and new, with some structures designed in collegiate gothic style and others in Brutalist form. Overall, the day was filled with zebra, writing, and fun!

By OLIVIA KWON

On the weekend of June 13th, the scholars traveled to New York City, where they conducted further research at the New York Public Library (NYPL). Upon arriving in the city, the scholars explored the Morgan Library & Museum—famously the former private library and collection of J.P. Morgan, featuring artistic, literary, and musical works. Some of the work on display included a Gutenberg Bible, clay tablets inscribed in Babylonian dating back to the first century B.C., and a Jane Austen exhibit. On Saturday, the scholars worked closely with librarians from the NYPL to explore materials from the Berg Collection, the Manuscripts and Archives Division, and the Jerome

Robbins Dance Division. The Berg Collection holds 2,000 linear feet of literary archives and manuscripts, as well as over 35,000 printed pamphlets, volumes, and broadsides in English and American literature. Seven scholars found themselves in this collection. The Manuscripts and Archives Division specializes in the papers and records of individuals, families, and organizations in the New York region, with over 5,500 collections and 29,000 linear feet of manuscripts and archives. Two scholars spent their time in this division. Lastly, the Jerome Robbins Dance Division is the largest and most comprehensive archive in the world dedicated to the documentation of dance,

By SOFIA RASIC

On the first day of the program, the scholars embarked on a mystery bonding activity: an outdoor escape room at Escape New Haven. The group was split into two teams of five, with one team doing the “Battle of the Bands” challenge and the other “Time Crimes.” Racing across the streets, each group searched for location-based clues to decipher their respective

codes, at times completing both mentally and physically taxing tasks. The scholars demonstrated perseverance, problemsolving skills, and athleticism in a heated competition to see who could finish first. While both teams gave it their all, the winning group was the “Battle of the Bands” squad: Ella, Olivia, Clemmie, Sofia, and Lucas! Everyone had a great time getting to know one another—and New Haven.

holding materials ranging from prints and DVDs to newspaper clippings and film. Lucas Ruiz conducted his research here as his author of focus, Jean Toomer, worked very closely with George Gurdjieff, a spiritual and movements teacher. While most scholars expanded

their research with an adjacent holding of a second author, some were able to continue studying their original authors, taking advantage of resources from a fresh and unfamiliar archive.

By WILLIAM BECKER

On Thursday, June 19, the scholars were treated with a visit by two special guests and a delicious dinner at Mory’s, a membership club for the Yale community. Before dinner, scholars shared some samples of creative writing work and special archival findings with Hotchkiss dean of faculty Shannon Clark and associate head of school Amber Douglas, who then joined the group at Mory’s. Mory’s was established in 1849 as a clubhouse and restaurant, which, due to its proximity

to the Yale campus, catered to Yale undergraduates. In 1912, when the building was going to be demolished, the owner sold it to Yale alumni who transformed it into the membership club it is today. This history carries with it many traditions, such as that of the drinking Cups, which the scholars were lucky enough to witness. The Cups are large, trophy-like, silver vessels from which customers consume a variety of alcoholic beverages. When the Cup is almost drained, there is a unique song for the last drinker, with their name as the chorus. The scholars enjoyed an amazing array of food, from truffle fries to steak frites to gelato for dessert. Overall, the evening was a lovely celebration of the scholars’ (almost) two weeks in the program, and it was a great opportunity to connect further as a group and with the faculty members.

My research at the Beinecke is centered around Marilynne Robinson, a prominent American novelist and essayist. Robinson is still alive today, and is most well known for her thoughts on religion, and its place in American

culture and society. Religiousinfluence is clear in her novels, as multiple primary characters are pastors and their families. I focused my research around this aspect of her writing, and looked for notes or changes that relate to religion. I was lucky to find three completely unpublished novels in her archive, and found hundreds of pages of drafts of her later published work. I was struck by one page of her unpublished work, because it mentions religion and religious language multiple times. It is very exciting to see how these characters and themes connect between her unpublished and published works.

My research concentrates on two celebrities of the literary world: Robert Louis Stevenson and Vladimir Nabokov. This combination is, by any

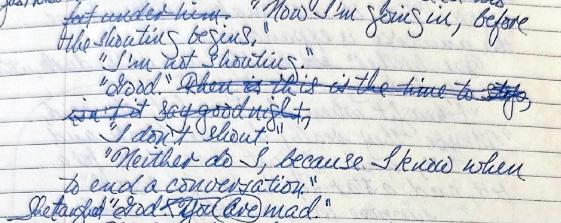

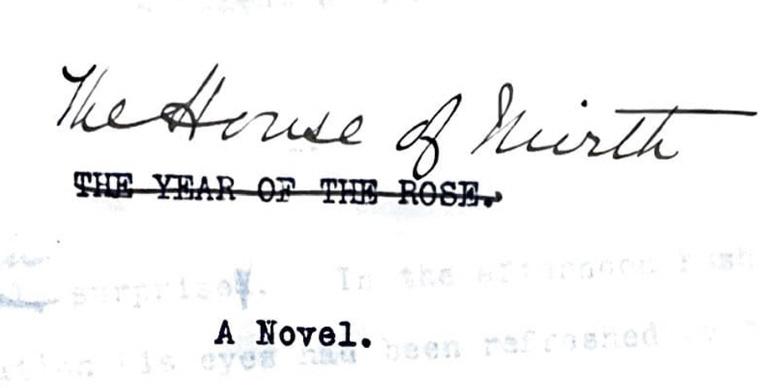

Throughout the two weeks at the Beinecke, my research was centered on novelist Edith Wharton. Wharton was born in 1862 to a wealthy family in New York City. Throughout her childhood, Wharton lived in New York and abroad in Europe in cities such as Paris. Her personal upbringing went on to highly influence her work as most of Wharton’s novels focus on New York City’s high society. She published over 40 novels including notable names such as The Age of Innocence, The House of Mirth, and Ethan Frome. In addition to her novels, Wharton also wrote numerous short

stories and poems, all of which I thoroughly enjoyed reading in the archives. Additionally, she was an avid interior designer and gardener—two artistic forms that are also present in her descriptive writing. Wharton’s archive in the Beinecke is extensive and meaningful. She was one of the first authors to donate her large collection of papers to Yale after receiving an honorary degree from the school in 1923. I spent the majority of my time reading the edited manuscripts or her published novels and her personal diaries. Through this work, I discovered interesting edits such as the title change from The Age of the Rose to The House of Mirth as seen in the image below. Looking ahead, I am excited to read more of Wharton’s work to develop a greater understanding for some of the intriguing edits I saw in her array of boxes.

metric, unusual. Time has exiled Stevenson— whose works include children’s classics such as The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Treasure Island— to the dusty corner of “adventure fiction,” a genre rarely thought to merit serious analytic study; contrastingly, Nabokov—who wrote Lolita and the less popular but equally brilliant Pale Fire—marinates in the fascinated attention of thousands of scholars across the globe, all of whom worship his metafictive genius. And yet these two men—who occupy opposite ends of the literary spectrum— share a surprising

number of connections: Nabokov himself was an admirer of Stevenson, and taught Jekyll and Hyde while at Cornell; both used scientific disciplines as inspiration for their larger works (psychoanalysis and geometry for Stevenson, space-time and entomology for Nabokov); both had extramarital affairs; and both grappled intensely with questions of love, loss, and the humancondition. These similarities extend to the archives, where diary entries and loose-leaf manuscripts outline two lives consumed entirely by literature. So devoted

were these authors that the line between fiction and reality seemed to have wholly dissolved for them: in one box, a newspaper clipping detailed Stevenson’s hatred for a real-life Mr. Hyde, while further research revealed that the circumstances surrounding Nabokov’s death bore an eerie resemblance to the plot of Pale Fire. Interestingly, both these events occurred after the publication of their corresponding fictional works; this apparent literary ‘manifestation’ hints at a shared feature of the subconscious that I’m excited to explore more throughout the year.

My research project examines the work of Modernist poet James Merrill, focusing on his exploration of the

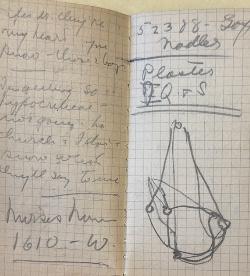

My research examines William Carlos Williams, a modernist poet and physician whose work centers on localism and shaping an American literary voice. During his lifetime, this New Jersey native, published over 20 collections of poetry, various works of prose, and even dabbled in playwriting. His most notable works include Spring and All, The Wedge, and a five volume epic Paterson. While in the reading room I primarily focused on his poetry drafts and notes, which he often scribbled on prescription pads, constantly inspired by his surroundings. One particularly interesting find was a little red notebook. Although it is undated, this pocketsized wonder was filled with medical notes, poetry fragments, and

supernatural and the interpersonal. With the wide range of themes exemplified in Merrill’s work and the extensive collection of archival material available at the Beinecke Library, I faced what one might call a “good problem”– not knowing where to begin. During my preliminary research on Merrill, I developed an interest in how personal matters, such as his family dynamic, his queerness, and, most notably, his fourdecade-long obsession with the Ouija board, manifest in his poems and novels. So, I began my two weeks at the Beinecke in search

diagrams. Within the notebook, there are three indistinguishable diagrams I’m particularly interested in analyzing. They seem to be 3D, existing in space, rather than on a flat plane, showing some form of spatial thought. I’m curious to see how this dimensional thought really translates into Williams writing, as much of his poetry exists in a concrete space, rather than the abstract. Another notable find was the unpublished sixth volume of Paterson. Paterson, Williams’s seminal work, is a fivevolume epic that uses the city of Paterson, New Jersey, as both setting and symbol, exploring themes of localism, identity, and the relationship between poet and place. As my research continues, I’m truly excited to delve into this epic and understand its significance in Williams’s life.

of some unpublished poem or a draft that might reveal untold truths about Merrill’s language and even his identity. Upon handling a draft of an unpublished poem, which I initially deemed would be my extraordinary archival finding, I noticed rough sketches of several different faces, nine in total, just below the typed text. Some faces were incomplete, some were in profile, and some were genderidentifiable through their hair length and features. I discovered more and more of these mysterious faces as I dug deeper into his boxes, even searching Washington

I am researching Mina Loy, an avant-garde writer, artist, and modernist innovator. Although she is broadly grouped with several overlapping modernist circles of her time—born in Britain, Loy lived in Futurist Florence, Surrealist Paris, and Dadaist New York (and for a time in Mexico City) before settling in Aspen, Colorado where she died in 1966—she never fit neatly into one of these spheres, and increasingly forged her own over the course of her life.

I have loved digging into Loy’s archive over the past two weeks. While her holding is smaller than most, it is rich, filled with unpublished writings and drafts and notes across the variety of mediums she worked in throughout her life; while she started out as an artist, Loy wrote poetry, novels, short

University’s digital archive of Merrill for more information. By the end of my two weeks, I had found over 60 pages of Merrill’s notes containing anywhere from 1 to 10 sketches of faces per page. These recurring faces left me more stumped than ever– who are these people Merrill has drawn over and over again? Why has Merrill chosen to draw these faces for many years across multiple sectors of writing? What could they possibly entail about the drafts that precede them on the page? There is still much to uncover, and I am eager to continue my search into the mystery of Mr. Merrill.

stories, essays, plays, and even made some of her own inventions. Her papers are full of whimsical drawings, seemingly groundbreaking yet cryptic one-line notes, and various codes and symbols that I am looking forward to exploring in the coming months. Especially exciting is the fact that much of Loy’s work remains unpublished to this day. In reading a number of Loy’s writings, I have come to notice that her individual pieces— spanning mediums—are somehow connected as a body of work. Oftentimes one directly references another, or borrows an exact or very similar section of unique and striking language. I am sure there are other, more subtle ties as well. I am excited to delve into this web of connections Loy seems to have laid out across her writing— especially a link I came across in the archives between her novel Insel (published posthumously in 1991), an unpublished short story entitled Hard Luck Story, and a poem entitled I Almost Saw God in the Metro (published posthumously in 1982 as part of The Last Lunar Baedeker collection). What makes this task more challenging—and hopefully more rewarding, eventually—is that most of her work is undated.

My author is Mary Ann Evans, commonly known by her pseudonym George Eliot. Eliot was an English novelist, poet, and translator was a leading figure of Victorian literature and realism. Her most famous works include Middlemarch, The Mill on the Floss, and Adam Bede. My research focuses on Eliot’s journals and notebooks, holding material on her travels, studies, and writing. During my research, I encountered quotations in Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and German, as well as notes on religion, philosophy,

At the Beinecke, I researched James Merrill, a modernist poet. His epic, The Changing Light at Sandover, intrigued me during my initial reading, and has continued to be the center of my archival research. The poem, spanning over three volumes, is a semiautobiographical account of Merrill’s interactions with spirits through the ouija board. Throughout this poem, James Merrill is faced with truths of the universe, emphasizing the

science, history, along with more niche topics such as clouds and gemstones! My work extends beyond the Beinecke as well; I recently discovered three digitized volumes of Middlemarch through The British Library. One of my most interesting findings was from a notebook kept while she was studying Kant. In addition to philosophy, the notebook had information on mathematics, physics, and science! Specifically, the section on Comte’s positivism caught my eye. Here, George Eliot explores the interconnectedness of human life, viewing all individuals as part of a “composite existence.” This may help explain her narrative style: novels touching on the motives, dilemmas, and perspectives of several characters, and occasionally with multiple plots. However, Eliot never restricted herself to one philosophy. I hope to find what parts of positivism she resisted, and how her beliefs and writing have changed over time.

human soul and its journeys across space and time. Merrill’s collection is full of manuscripts and drafts of poems, but has few notebooks, which allowed me to pay close attention to the notebooks that were available. While consulting one of said notebooks, I discovered a page that marked The Book of Ephraim, as “Part II,” while “Part I” was “Time Was”— seemingly not an unwritten text of Merrill’s nor a reference to any published work. That shocked me until I found an excerpt from a text called “Time Was” by “A. H. Clarendon” in a quotation in The Book of Ephraim, and, upon further research, the text and author don’t seem to exist. This find, a fake quotation that is said to predate The Book of Ephraim, the volume in which this quote resides, in Merrill’s canon, opens up the door for questioning Merrill’s choices with narrativity in his works.

I have been researching Jean Toomer, born in Washington D.C. in 1894, a poet and novelist during the Harlem Renaissance. After reading his most popular book Cane in English class—a mixture of poetry and prose capturingAfricanAmerican experiences in the early 20th century—I began exploring Toomer’s archives, focusing initially on materials related to Cane. I examined drafts and original publications to understand his writing process.

During my first week, I

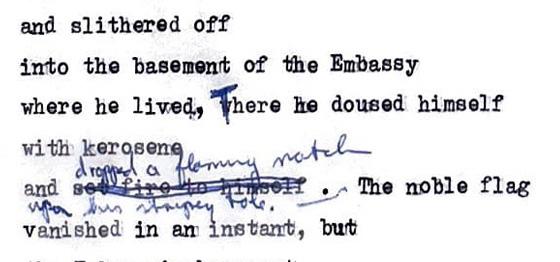

My research at the Beinecke has focused on science fiction and dystopias as forms of social commentary, particularly within American literature. I chose to study Thomas M.Disch, a science fiction writer who used speculative and surreal elements to critique topical issues in American society. For example, in his poem The American Flag, a flag sets itself on fire to protest war, symbolizing Disch’s belief that the nation’s core

studied Toomer’s journals, letters, and notes, which provided insight into his evolving spiritual and philosophical beliefs. I was particularly interested in connections between Cane and Gurdjieff’s teachings, leading me to research at NYPL’s Library for the Performing Arts, since dance was central to Gurdjieff’s spiritual beliefs. This expanded my research into Toomer’s archives through the 1940s. One of my archival gem discoveries was the poem “Gum,” published in April 1923 but not included in Cane. Found in box 55, this poem stood out because I hadn’t found any Toomer writing from 1923 unrelated to Cane. “Gum” mentions Seventh Street (a Cane poem title), references Jesus twice (religion being central to Cane), and uses “gum”—a recurring symbol in cane. This gem raises questions about why Toomer excluded it from Cane and how it might change interpretations of his work.

values have been distorted. The poem balances an absurd scenario of a flag coming to life with a relevant realworld debate, challenging the notion that science fiction is less politically potent than realism. This unique opportunity to pursue archival research has given me the fascinating experience of getting to know Disch as not just a name, but as a talented, thoughtful, and complex human being. I have especially enjoyed tracking how he adapted his literary style across genres while maintaining several recurring themes informed by his lived experiences. As I continue familiarizing myself with Disch’s published and archival collections, I look forward to analyzing more societal critiques as they appear across his diverse body of work.

By LUCAS RUIZ

Scholar Lucas Ruiz sat down with Ms. Anna Godberson, instructor in English, to discuss her experience teaching the creative writing portion of MacLeish. Ms. Godberson joined the English department this past fall and teaches Creative Writing and Humanities 250: American Literature. She has published nine books including her Luxe Series of young adult novels.

What does creative writing mean to you?

Creative writing is noticing the world and one’s own experience and finding a way to put that into language that is effective— because the thing being communicated may not be familiar—and original—expression in a new and surprising way to a reader who may not have known they needed to hear something or understand something or feel something like that.

How would you describe your personal writing process?

My process is regular and committed. There’s a line from Gustave Flaubert that’s something like, “live with regular, ordinary habits—like petit bourgeois—so you can be wild at heart” (I’m just paraphrasing it). But I have a very regular writing practice, when things are going well. I like to write every day, for about three to four hours. I commit myself to the time and see what happens. The hope is that I can surprise myself or write a scene that is perhaps not like anything I’ve ever written before, that just comes out of committing to writing.

Godberson

How did you go about planning and structuring the MacLeish summer class?

I thought about exercises that would be good for generating a lot of writing and accessing personal experience, especially in a way that would help one think about language and how to use it creatively and in surprising ways. I tried to think of prompts that would be interesting both to people who have done a lot of creative writing and those who haven’t really. And then I tried to think about different exercises that we could work through over time so that we could start by coming up with a lot that

didn’t necessarily have any form to it, and then move to a place where we were considering: Is this a poem? Is this a story? How do you put it together? What’s the beginning, middle and end? All of these are questions that lead us to finding the right container for our ideas and experiences.

What has been your favorite part of the program as a whole?

Being able to be part of a very intensive program where you’re with students as they’re making discoveries— both about their scholarship and their own writing—is thrilling. It’s such a concentrated

environment, and the changes happen so quickly and significantly. Seeing in real time what you’re building is super exciting. And I just love that there is an intersection of scholarship and creative output.

Who is your favorite author?

Joan Didion, probably. She was a novelist and an essayist, and she has a very distinctive style. She’s from California, which is where I grew up. Her writing was the first thing I think I really fell in love with. I remember being struck by how strong and distinct her voice was, and I immediately wanted to try to accomplish the same with my own writing. So I think my connection to her work has kind of that first love quality to it.

What did you want students to take away from their time in the course?

I wanted you all to come away with a sense of your own voice as writers, and also a sense of what it feels like to try and produce literature— because you’re going to spend a whole year thinking about your specific authors and considering why they made the work they did and how they went about it. I hope you will continue your creative writing, and that having accessed your own sensibility as writers and readers, and a sense of your own voice, will encourage you to continue; but I also just think it’s really useful to know what it feels like to try and create literature when you’re studying it.

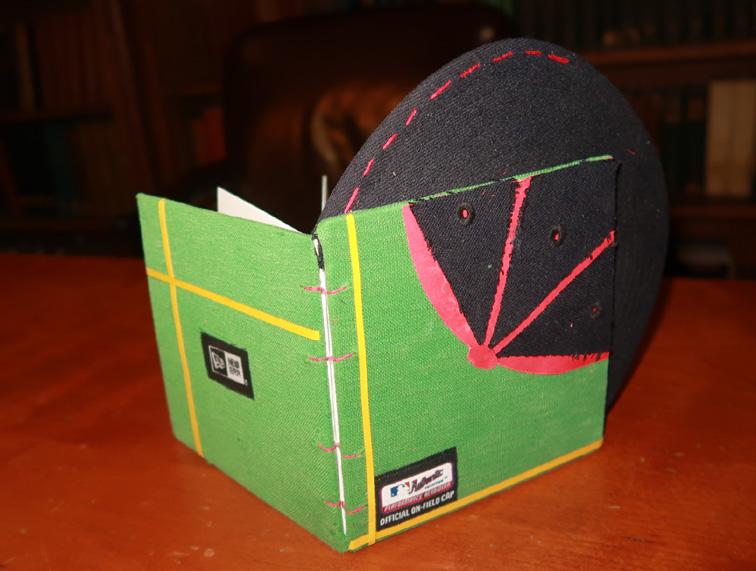

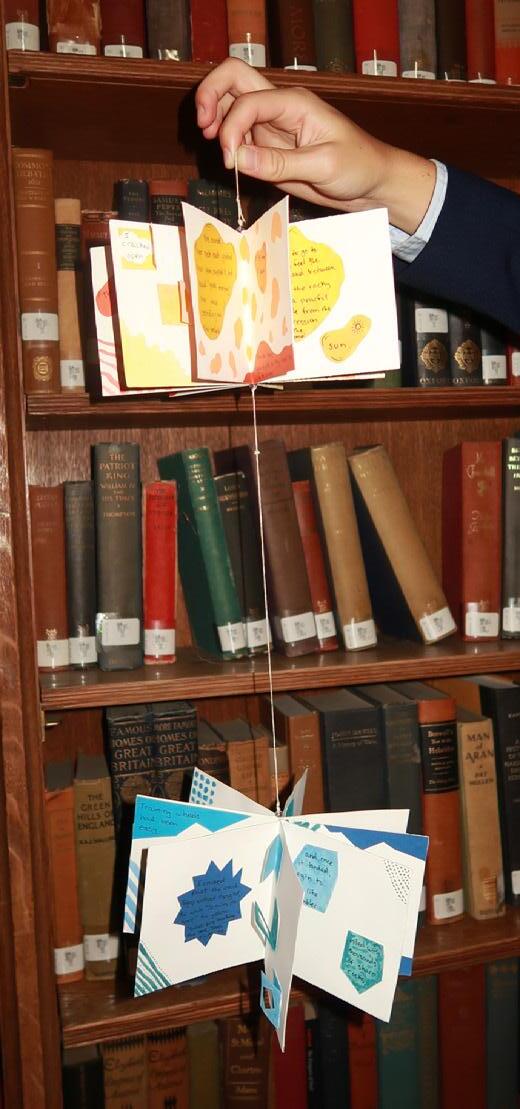

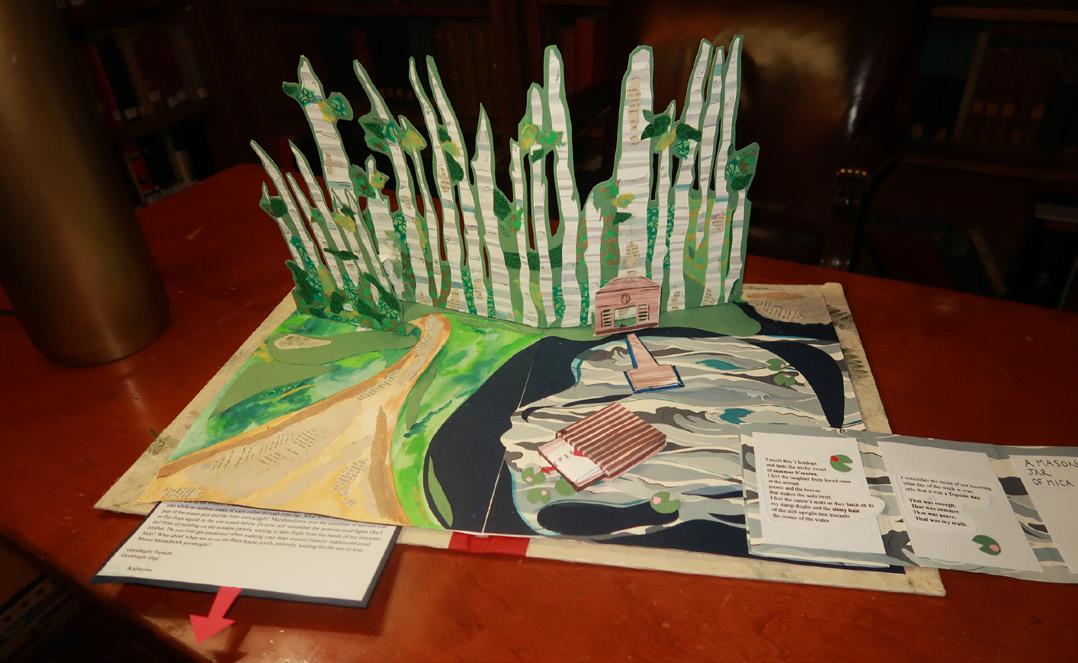

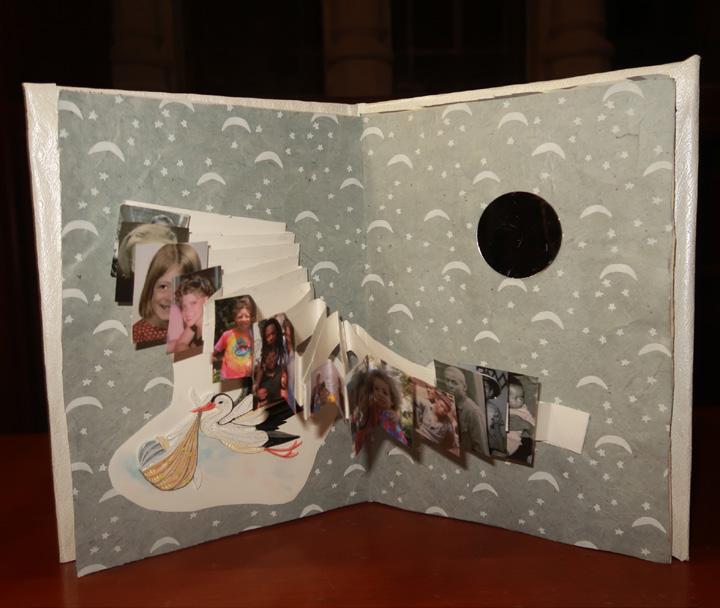

The MacLeish Scholars Program is one of my favorite times of the year. I’m always excited to meet the new cohort, learn more about their exciting archival experiences, and show them the world of contemporary bookmaking practices. We start by collectively analyzing a small collection of artist books that use different approaches to material, text, and binding. From there, the first exercise uses found images and texts to create zines which are then scanned, printed, and exchanged together in a collected volume through coptic stitch binding. Experiments in drum leaf and accordion fold offer glances into what is possible within the structure of a book, manipulating the material of text and image to make the reader’s experience one that is less static than a traditional book.

From there, Scholars devise their independent final projects for the session that incorporates critical connections between text, image, material, and form.

This year’s Scholars produced phenomenal work, ranging from ambitious pop-ups to hanging pinwheels acting as an abstracted bicycle to delicately bound envelopes of pressed flowers and leaves to a completely deconstructed Boston Red Sox hat and so on. There is even a slice of cake made out of book board and paper. Scholars imbued their books with their own drawings and writings, connecting the whole program into a singular object.

As an academic, we are often required to have teaching statements alongside research statements and CVs when applying for jobs or otherwise. My statement emphasizes a blurring of lines between my artistic, teaching, and research practices – I keep neither fully separate

from each other. For the last 5 years, the MacLeish Scholars Program has been an excellent example of this collaborative approach to teaching and making. I always return to my office in Ohio energized and fully inspired. I often utilize scholar’s work as examples for my undergrads (and vice versa,) sharing possibilities of what art, bookmaking, and research means in today’s world. These creative components of the program are integral to imagining potentiality – it is through creative scholarship that archival research can reach its fullest potential. It continues to critically reflect on my own practice, leading to joining the Scholars at the Beineke and conducting my own research alongside them. Through exploring bookmaking, students in both the MacLeish program and beyond can critically examine the way information is

relayed to others both within and outside their specific research interests. It offers opportunities to consider material and embodied experiences in connection with that information, something vital in an increasingly digital age. Even digital projects have a material, whether its coding, pixels, or screens. By exploring the materiality of language through bookmaking,Scholars can approach any future opportunities with a unique sense of criticality. I have no doubt that previous cohorts already have, and that this one will continue to thrive.

Sincerely,

Neil Daigle Orians Assistant Professor Area Head of Printmaking Foundations Coordinator

University of Cincinnati School of Art