What College is Meant to Be

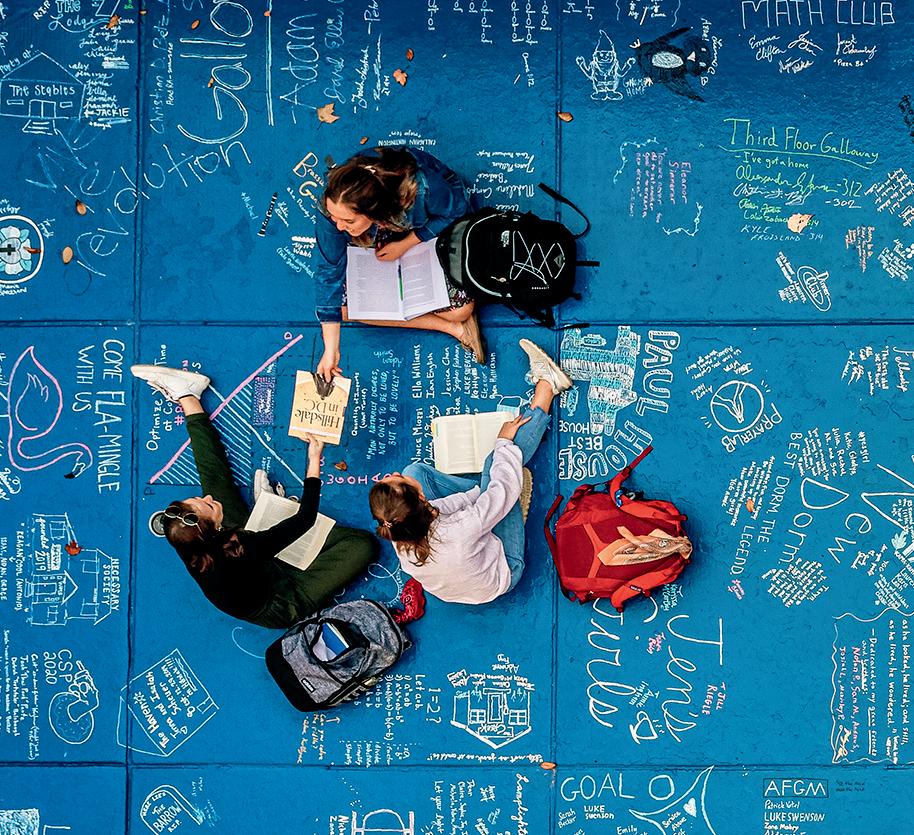

Years of dedicated study during one of the most formative periods of your life: your undergraduate education is sure to have consequences. Students at Hillsdale College engage in high learning, the type of profound learning that equips the intellect and builds the character into habits of virtue. The method and material of that learning is the classical liberal arts, a subject we speak about often and with affection at Hillsdale, and a subject we delight in introducing to you in the pages that follow. It’s learning that begins in the classrooms of our southern Michigan campus, but stays with you for a lifetime—learning that has less to do with your future job, and more to do with your future person.

The liberal arts may be understood, first, in contrast to the servile arts. Simply put, liberal arts are those ways of acting and knowing that have their justification in themselves. Servile arts are those human activities that have a purpose beyond themselves. It follows that the servile arts, while possessing great dignity and immense value, are distinct from the liberal arts. We suffer, starve, and perish without the servile arts, those arts that are directed to useful, practical tasks of life. The two types may thus be distinguished by their differing aims. The liberal arts aim to make a particular kind of human being, one of character and self-government, the kind of human being who both knows what is good, true, and beautiful, and how to love such things in the right way. The servile arts, by contrast, aim, not to make the good man, but a good plumber, a good banker, a good surgeon, or a good technician. This distinction between liberal and servile arts may be drawn more sharply. A liberal art is any organized body of knowledge worth knowing for its own sake, in and of itself, without any regard for its potential usefulness. Liberal learning is thus free or liberated from the burden of answering this question: “What is the practical use, application, or benefit of this subject?” This can be hard to understand in our age of “relevantism.” The vast majority of today’s college students arrive on their campuses primed to ask, “How is this course, this assignment, this lecture relevant for my future work? What can I do with it? Tell me its practical use.” These are not bad questions for those seeking vocational training. But liberal learning is something different.

Aristotle wrote, “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves.” Here he recognizes that there is a delight to learning that has no consideration for the usefulness of the things learned. Liberal learning, therefore, concerns the attitude and disposition with which the student attends to his or her studies. The Latin root from which we derive the word “student” refers to the disposition of eager devotion and enthusiasm for the subject. When one loves something for its own sake, one does not begin by asking what it can do for you. This emphatically does not mean that the liberal arts are useless. Quite to the contrary, liberal learning produces the most useful sort of people, equipped to flourish in life’s myriad vocational callings.

Liberal learning produces cultivated citizens with minds disciplined and furnished through wide and deep study of old books by wise authors. It does so by leading forth students into a consideration of what has been called, “the best that has been thought and said.” The liberal arts endow students with the capacity to educate themselves because they have gained the intellectual frameworks, curiosity, and methods to pursue a life of learning. St. Augustine boasted about his own liberal education. He claimed that as a result of it he “could read anything that was written, understand anything he heard said, and say anything he thought.” If one can put those skills on a résumé, getting a good job will be no problem. All of these, and more, are natural consequences of immersion in the liberal arts. When it comes to liberal learning, the best attitude to cultivate is one of leisure. Set aside questions about “practical relevance” and usefulness of each course. Remember, the Greek word skhole—the root from which we derive the word “school”—means leisure, free time, or rest. In the classical Greek world where the liberal arts were first conceived, free time was to be spent in lectures, discussion, and contemplation; that is, in learning for its own sake. It turns out that for human beings, such liberal learning is the most useful learning we can get.

HENRY SALVATORI CHAIR IN HISTORY PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

All Hillsdale College students study a rigorous, structured core curriculum that takes about half of their time at Hillsdale to complete. It introduces fundamental concepts and competencies that will help you to better understand your world and your place in it. You’ll find yourself engaged with the greatest thoughts and thinkers of Western Civilization across centuries, continents, and disciplines, and learn how timeless wisdom never ages.

Classical Logic and Rhetoric—Prepare and analyze arguments, practice decision-making, develop critical thinking about matters of certainty as well as probability, and learn why logic and rhetoric are classically viewed as sister arts of inherent import to the liberally educated student.

Great Books in the Western Tradition—Receive an introduction to representative Great Books in the West from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, meeting works like the Bible and authors such as Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, Ovid, Augustine, and Dante.

Continue your study of the Western literary tradition with English authors like Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, Wordsworth, Dickens, Yeats, and Eliot, and American authors like Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, Twain, Frost, Hemingway, and Faulkner.

“The liberal arts encourage the development of the whole person and open the door to a fuller picture of reality and truth.”

—TAYLOR DICKERSON, ENGLISH AND PHILOSOPHY

The Western Philosophical Tradition

—Receive a general overview of the history of philosophical development in the West from its inception with the Pre-Socratic philosophers of ancient Greece to the 20th-century AngloAmerican and Continental traditions. Meet thinkers and innovators like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, Locke, Hume, Kant, Mill, and Nietzsche.

Western Theological Tradition—Be instructed in the basic teachings of the Christian faith in order to see how religious belief informs selfunderstanding, provides a comprehensive view of reality, and by instilling a vision of human life, its purpose, and proper comportment, shapes the larger culture.

Western Literature Survey

Choose one course from several options: continue your study of the Great Books with selections of European literature from the Renaissance to modern times; study Greek and Roman literature and culture and its influences on the West; or spend time with European drama from the Renaissance, Neoclassical, Elizabethan, Spanish Golden Age, English Restoration, and early German Romantic periods.

Acquaint yourself with the historical roots of the Western heritage and explore the ways in which modern man is indebted to the Greco-Roman culture and the Judeo-Christian tradition.

The American Heritage—Follow the history of “the American experiment of liberty under law” from our colonial heritage and the founding of the republic to the increasing involvement of the United States in a world of ideologies and war.

The U.S. Constitution

—Receive an introduction to early American political thought and its crowning political achievement, the United States Constitution. Learn basic American political concepts like natural rights, social compact theory, religious liberty, limited government, separation of powers, and the rule of law.

Choose one course from a selection of options: receive an introduction to the study of economics and its relationship to political systems; examine markets, prices, profits, production, costs, competition, monopoly, wages, rent, and interest; take a broad survey of the contemporary science of psychology; or study historical, conceptual, and cross-disciplinary perspectives on sociocultural structure and dynamics.

Choose one course from a selection of options: survey the visual arts of architecture, painting, and sculpture from the prehistoric through Medieval or Renaissance through modern periods; receive an introduction to the repertoire of Western music and music theory at an entry or intermediate level; or learn to appreciate Western theatre and how dramatic structure, style, purpose, and effect are the keys to understanding the relationship between author, performer, and audience.

Learn how life evolves and adapts in continually changing environments. Relate such principles to current issues such as diet and health, extinction and habitat loss, genetic modification of people and other organisms, and the emergence of novel diseases, among others. Above all, see how empirical biological mechanisms can help us understand and predict the connections between people and the natural world.

Consider the implications of the “big ideas” of chemistry and the evidence for them—the atomic nature of matter, bonding, intermolecular forces, structure and shape, chemical reactions, and transfer of energy—and the relationship of fundamental principles of chemistry to current and emerging global issues. Discuss the nature of empirical scientific methodology and the strengths and limitations of science as a way of knowing.

—Explore the fundamental Laws of Nature (Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation; Maxwell’s equations regarding electricity, magnetism, and light; Einstein’s special and general theory of relativity; quantum mechanics and the Standard Model), their character, the principles that run through them, and how they apply to observable phenomena, and see how these laws play an important role in the fields of astronomy and cosmology.

Aristotelian logic and deductive reasoning, mathematical arguments and proof, and study axiomatic systems like Euclidean geometry as you explore the nature of mathematics.

—Practice a basic physical wellness program through physical conditioning, strength development, and nutrition; and build a knowledge base of the physiological effects and adaptations of exercise, nutrition, and stress on the mind, body, and spirit.

Choose one week-long lecture seminar from the Center for Constructive Alternatives, an on-campus lecture series held four times annually. Subjects are varying and have recently included topics such as Markets and Policy, American Generals, The Inklings, Critical American Elections, Big Tech, Jane Austen on Film, and American Foreign Policy.

—Synthesize critical concepts across the core curriculum and see their purpose in relation to a life pursuing the good.

“Studying the liberal arts at Hillsdale has given me both the discipline to address hard questions and the courage to act upon the answers that I discover.”

—CHRISTOPHER “SOREN” MOODY, PHILOSOPHY

“Hillsdale’s core enriches the more specialized study of students in every discipline and becomes a foundation upon which their learning builds.”

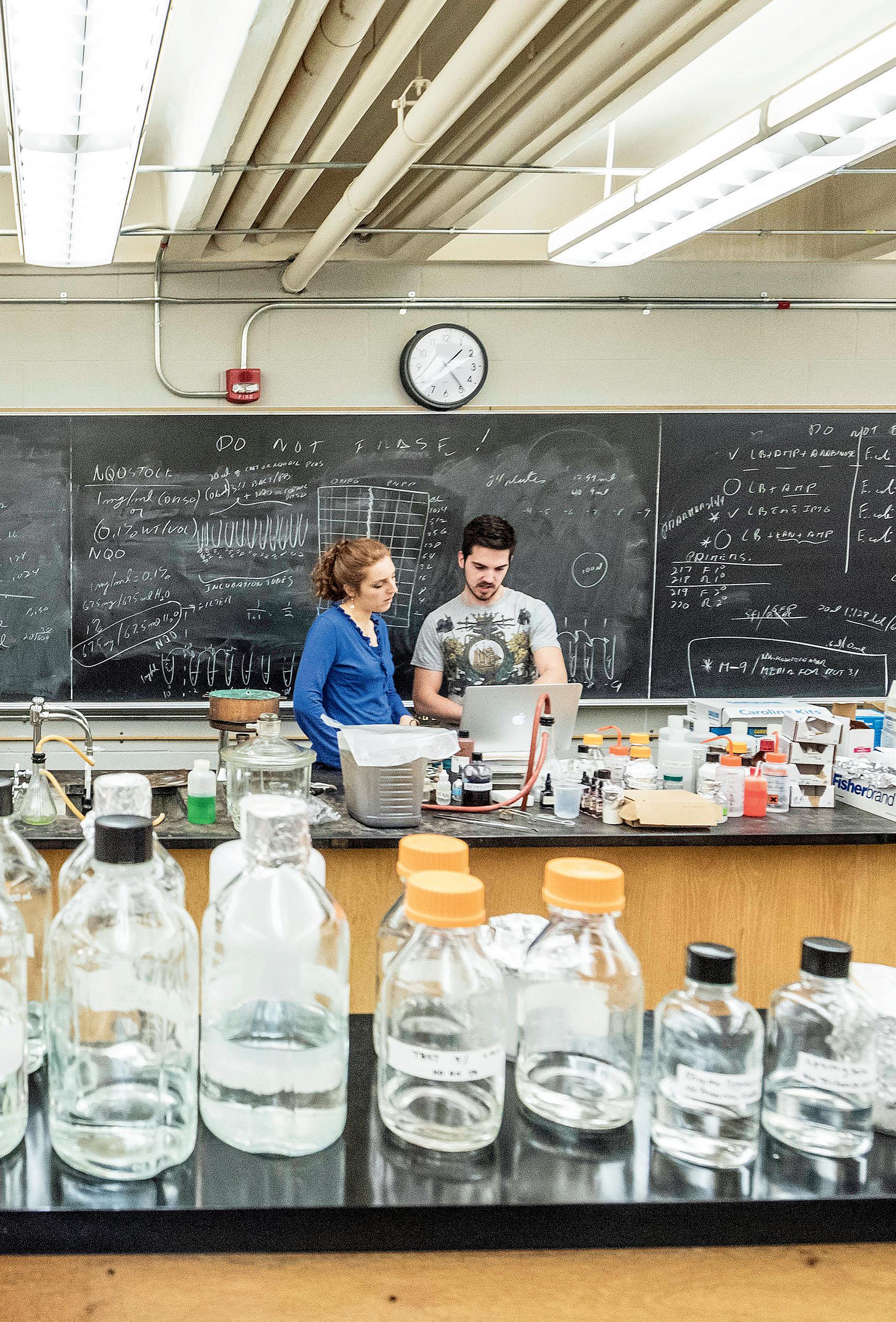

—FRANCIS X. STEINER, PH.D., PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY

Study in the disciplines of the core curriculum will invariably reveal areas of particular interest. With the guidance of a faculty advisor, all Hillsdale students choose a major area of specialization (or more than one), and although not required, many also choose to pursue a minor field.

Accounting

American Studies

Applied Mathematics

Art

Biochemistry

Biology

Chemistry

Classics

Economics

English

Exercise Science

Financial Management

French German

Greek History

International Studies in

Business and Foreign Language

Latin

Marketing Mathematics

Music

Philosophy

Philosophy and Theology

Art History

Classical Education

Computer Science

Dance

Early Childhood Education

Entrepreneurship

General Business

Graphic Design

Physical Education

Physics

Political Economy

Politics

Psychology

Rhetoric and Media

Sociology and Social Thought

Spanish

Sport Management

Theatre

Theology

Journalism

Military History and

Grand Strategy

Military Leadership

Hillsdale’s preprofessional programs, while not majors, are designed to prepare students for graduate or professional school in the following fields. Students consult with the College’s preprofessional advisor to determine appropriate course requirements for their particular postgraduate interest.

Allied Health Sciences

Dental

Engineering

Law Medicine

Pharmacy

Veterinary Medicine

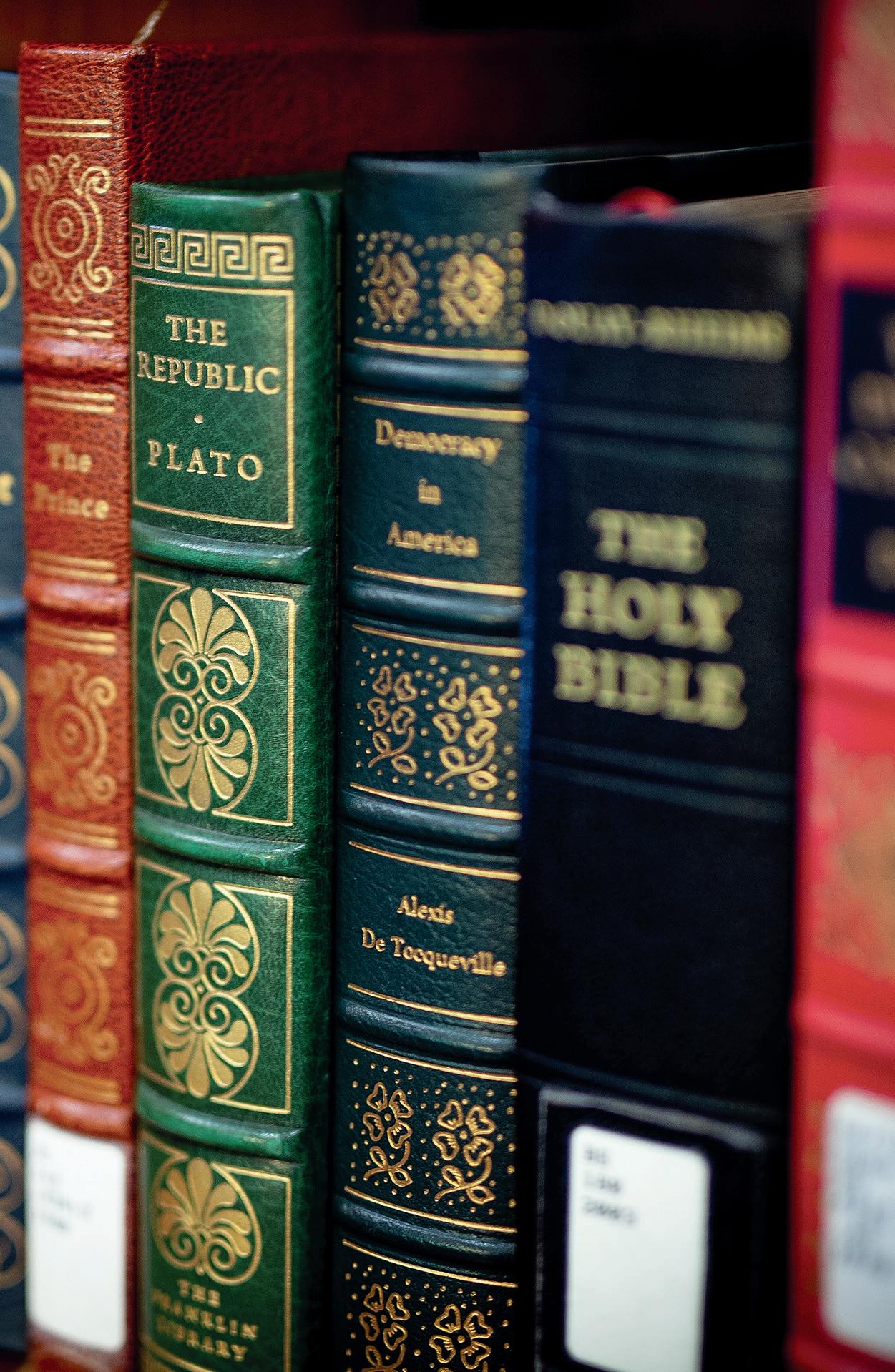

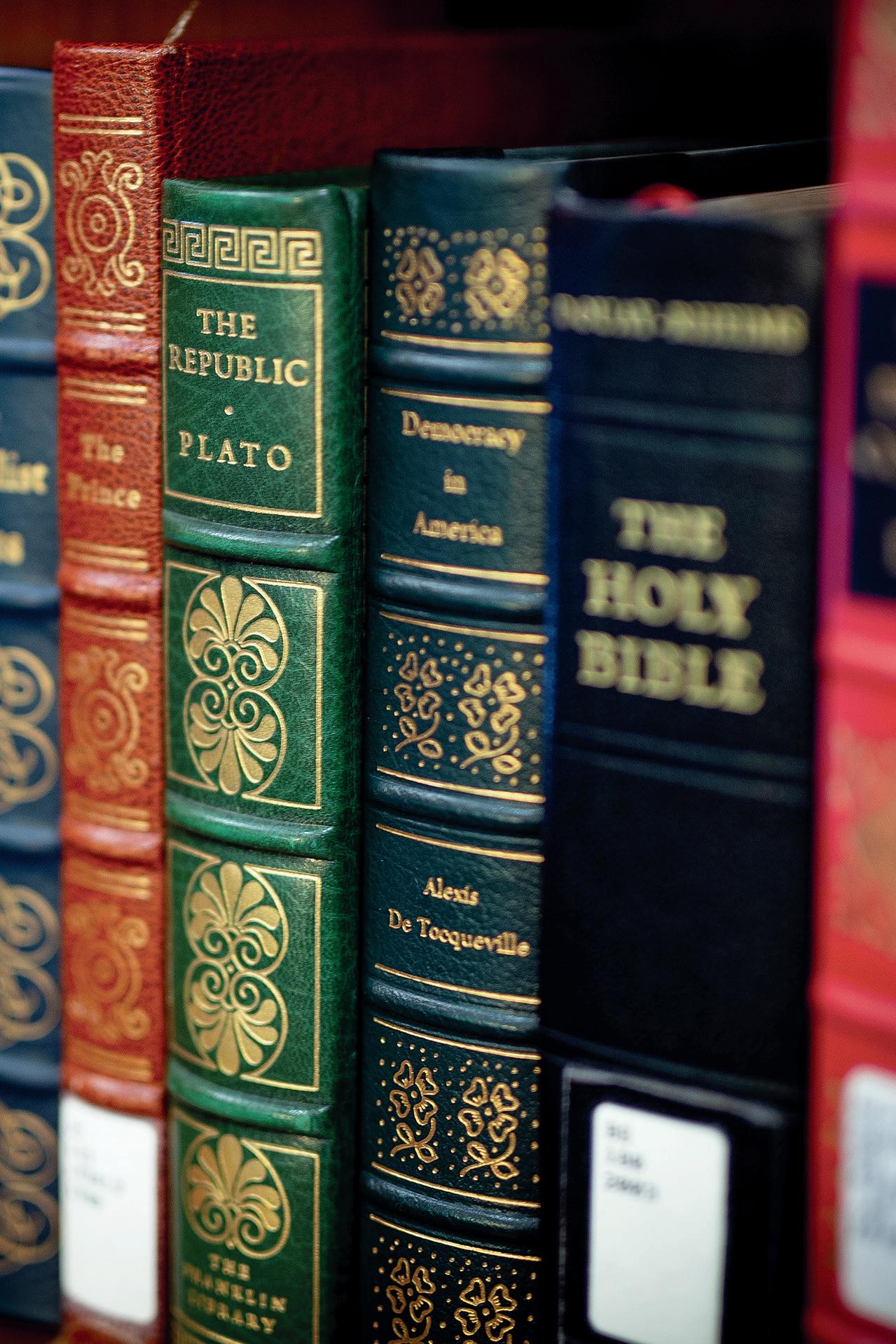

Great Books reveal timeless truths about the human condition. They introduce us to important questions about life and how to live it, and compel us to think deeply in reflection on those questions.

“A true liberal arts education sets one free by providing flexibility of mind to rise to new challenges. My mind was set free at Hillsdale.”

—ROSEMARY ALLEN, PH.D., ’78, GEORGETOWN, KENTUCKY

• The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis, 1943

• The Aeneid, Virgil, 19 B.C.

• Autobiography, Benjamin Franklin, 1791

• Candide, Voltaire, 1759

• The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, c. 1400

• The Cherry Orchard, Anton Chekhov, 1904

• City of God, Augustine, c. 410

• Common Sense, Thomas Paine, 1776

• The Confessions, Saint Augustine of Hippo, c. 400

• The Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius, c. 524

• The Constitution of the United States of America, 1787

• The Death of Ivan Illyich, Leo Tolstoy, 1886

• The United States Declaration of Independence, 1776

• Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville, 1835

• De Officiis, Marcus Tullius Cicero, 44 B.C.

• Discourses, Epictetus, c. 108

• The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri, 1320

• Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes, 1605

• Elements, Euclid, c. 300 B.C.

• Essays, Michel de Montaigne, 1580

• Faust, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1808

• The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Madison, 1787

• The Book of Genesis

• Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln, 1863

• The Gospel According to Matthew

• The Gospel According to Luke

• Hamlet, William Shakespeare, 1603

• Histories, Herodotus, 430 B.C.

• The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, c. 411 B.C.

• The Iliad, Homer, c. 752 B.C.

• Medea, Euripides, 431 B.C.

• Meditations, Marcus Aurelius, c. 180

• Messiah, George Frideric Handel, 1741

• The Metamorphosis, Franz Kafka, 1915

• Moby Dick, Herman Melville, 1851

• Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle, c. 340 B.C.

• Notes from the Underground, Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1864

• The Odyssey, Homer, c. 700 B.C.

• Oedipus the King, Sophocles, c. 429 B.C.

• On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Nicolaus Copernicus, 1543

• One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, 1962

• The Oresteia, Aeschylus, c. 450 B.C.

• Orthodoxy, G.K. Chesterton, 1908

• Paradise Lost, John Milton, 1667

• Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen, 1813

• The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, 1532

• Principia, Isaac Newton, 1687

• Republic, Plato, c. 375 B.C.

• The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1850

• The Starry Messenger, Galileo Galilei, 1610

• Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas, 1485

• St. Matthew Passion, Johann Sebastian Bach, 1727

• Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, Ludwig van Beethoven, 1824

• Two Treatises of Civil Government, John Locke, 1689

• Utopia, Thomas More, 1516

• Walden, Henry David Thoreau, 1854

“We call some books great simply because they take us deeper than others into the questions that most concern human beings. The heart of my teaching here at Hillsdale is our yearly cycle through these texts, which is like an annual return to draw new, fresh water from the deepest of wells.”

—DWIGHT LINDLEY, PH.D., ’04, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

“Proponents of the liberal arts experience recognize that in order to function in an increasingly complex world, it is imperative to have an understanding of the fundamental concepts of humanity. The questions of what has been, what is, and what will be, are eternal, and the liberal arts allow us to approach them with curiosity and critical reflection.”

—KIRSTIN

KILEDAL,

PH.D., ’87

, PROFESSOR OF RHETORIC

Hillsdale’s faculty are the people who, along with their students, breathe life into Hillsdale’s classical liberal arts core and major programs. They’ll challenge you to ask tough questions, to defend your beliefs, and to stretch your abilities, all while standing behind you as your biggest source of support. Together, you’ll pursue the good, true, and beautiful, and become the better for it in heart and mind.

“Those students who pursue a liberal arts education will actualize distinctly human potentials that can make them thoughtful and articulate, and they are— moreover—furnished with key instruments to assist them in the lifelong pursuit of wisdom and virtue.”

—BENJAMIN BEIER, PH.D., CHAIRMAN AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF EDUCATION

M. WHALEN, PH.D., PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR CURRICULUM

Hillsdale College Admissions admissions@hillsdale.edu

(517) 607-2327 hillsdale.edu/admissions

“It is the education which gives a man a clear conscious view of his own opinions and judgments, a truth in developing them, an eloquence in expressing them, and a force in urging them….It prepares him to fill any post with credit, and to master any subject with facility.”

—JOHN HENRY NEWMAN, THE IDEA OF A UNIVERSITY, 1852