CLASS OF 1975

The JFK Library That Never Was

Bill Gates’s Journey From Brainy Undergrad to Microsoft Founder

BY CAROLINE G. HENNIGAN AND SAKETH SUNDAR CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

Bill Gates arrived at Harvard College in September 1973 as a quiet freshman from Seattle in Wigglesworth Hall. He left campus two years later not with a degree, but with a piece of software that would launch Microsoft and begin reshaping the digital landscape.

Before co-founding the world’s largest software company, Gates spent most of his Harvard days behind the glass walls of the Aiken Computation Laboratory. There, surrounded by the blinking terminals of a PDP-10 mainframe, Gates immersed himself in code — largely unnoticed by his peers and professors.

His trials in the Aiken Lab, in collaboration with Harvard students and his childhood friend Paul Allen, soon lead to the development of a BASIC interpreter that compressed code from Altair computer owners into a smaller device. This code was the first product of Gate and Allen’s business, which they named “Micro-soft,” later shortened to Microsoft.

Gates and his fellow residents of Currier — affectionately coined “nerd world” by students — were a microcosm of the burgeoning field of computer science. Over dining hall conversations and late-night meetups at the grill, Gates and his colleagues immersed themselves in a hub of entrepreneurship. His long hours with Harv-10 — Harvard’s nickname for its PDP-10 model — were only interrupted by hours-long poker matches and pinball tournaments at Currier House. Kirk H. Citron ’77, who worked at the Currier grill, said Gates would visit the late-night eatery “probably on his way to

or from the Science Center.”

“It’s a pretty famous story that he would spend all night on the computer systems in the basement of the Science Center,” Citron added.

‘Ridiculous Number of Classes’

When Gates started at Harvard, the College was still a decade away from offering a Computer Science degree. Instead, Gates took as many Applied Math classes as he could.

“I loved my time at Harvard. I took a ridiculous number of classes, some that I’ve signed up for, some that I just audited,” Gates said at a February talk in Sanders Theater.

As a freshman, Gates enrolled in Math 55, Harvard’s most advanced introductory mathematics course. He also audited and enrolled in graduate-level classes, including Applied Math 251a and 251br — both taught by Jeffrey P. Buzen, whom Gates later described as teaching “the only computer course I officially took at Harvard.”

Buzen said Gates’ presence in the class was highly unusual for a freshman.

“He was overall intelligent enough certainly to take the course for credit, even though he was a freshman,” Buzen said. “That was rare in those days, because people came to Harvard without extensive background in computers that nowadays you typically see.”

By sophomore year, Gates was also enrolled in Applied Math 122, taught by computer science professor Harry R. Lewis ’68. “I didn’t interact with him about Microsoft or the thing that was becoming Microsoft at all,” Lewis said. “Could I have picked him out from all of the other smart, self-confident, overly confident sophomores? Probably not.”

On the first day of class, Lew -

is said he posed the “pancake problem” to his students — a math puzzle that involves finding the smallest number of flips required to sort a stack of pancakes by their diameters.

Gates came back to class with the solution two days later. “That was the basis on which we got to know each other,” Lewis said.

Four years later, Gates published a proof of the pancake problem, determining that it takes five-thirds of a flip per pancake to sort any size stack. He credited Lewis as suggesting the problem.

Monte Davidoff ’77, Gates’ sophomore roommate in Currier House, said Gates was usually a reserved student. “He kept to himself and his small circle of friends, but he could be intense,” Davidoff said.

Barbara G. Rosenkrantz ’44, the Currier House Master when Gates lived there, said in a 1992 interview with The Crimson that Gates was rarely home. “He was not usually in the house at that time,” she said, adding that she supposed he spent his hours at the Aiken Computation Laboratory.

Rosenkrantz was right. When Gates was not in class, he was at the Aiken Lab, where he was granted rare undergraduate access to the PDP-10 mainframe by Harvard professor Tom Cheatham — a resource that was reserved primarily for graduate students.

“There was a big computer here that nobody was supervising, and I went to the professor as an undergraduate, which was weird, and got permission to use this graduate computer,” Gates said in February.

Outside of the lab, Gates played video games and foosball in the Aiken Lab, and made frequent stops at a pinball machine near the Currier

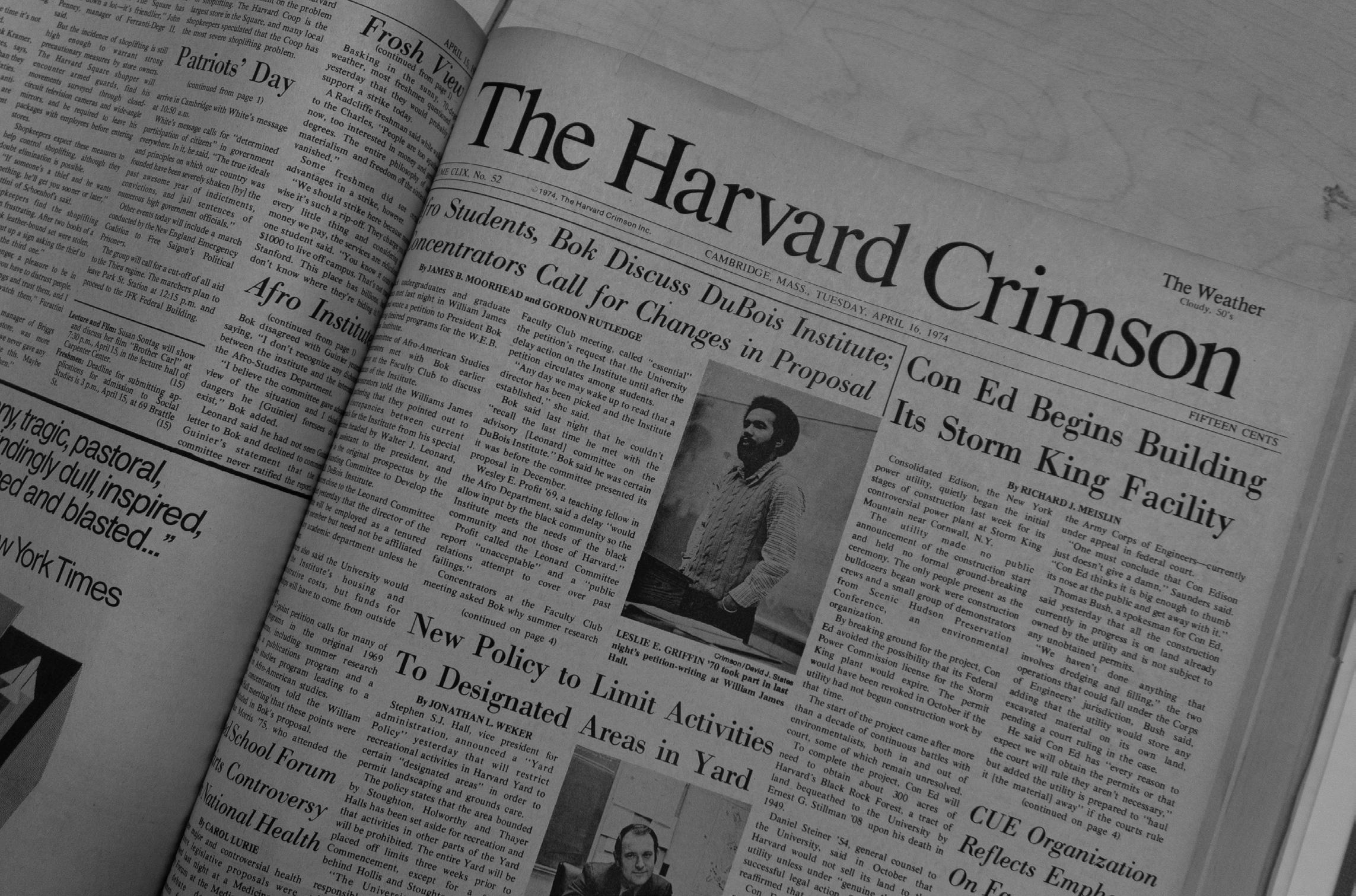

The Contentious Birth of the Du Bois Institute

BY CLAIRE JIANG AND CAM N. SRIVASTAVA CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

For six years — from 1969 to 1975 — a war raged at Harvard over the question of how to establish a research institute for African-American studies.

When Harvard’s Afro-American studies department was founded in 1969, the faculty legislation also called for the creation of a Black studies research institute.

But contending viewpoints among Black faculty, students, and administrators on who would control its development, and ultimately run the institute, stalled progress for years — even as other Ivy League universities founded similar research institutes of their own. Eventually, a group of Black faculty outside the department — convinced its research was limited or flawed — persuaded Harvard’s president, Derek C. Bok, to found an external center for Black studies.

“It was ideological, it was personal, it was deeply unpleasant, and never the twain should meet, and the department remained in serious trouble for a long time,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., University professor and longtime director of the institute.

Though the mandate for a research institute was clear, faculty and administrators could not agree on who would have control over it.

Ewart Guinier, Class of 1933, chairman of the Afro-American department, thought his department should direct the institute — to him, the newfound department’s success would depend on the resources of the institute, and the institute’s scholarship would benefit from the department’s focus on Black studies.

But Nathan M. Pusey — Class

of 1928, and Harvard’s president from 1953-1971 — and his administration wanted the University to control the institute.

John T. Dunlop, Dean of the Faculty, informed Guinier that the Ford Foundation — a private philanthropic organization — would fund the institute, but only if it were established on a University-wide basis. Guinier did not agree with the vision and refused to convene the faculty committee overseeing the institute’s development, which he chaired, until Pusey’s administration changed course.

Neither side relented, and for almost two years, from 1970-1972, progress toward the institute’s development stalled.

Pusey’s administration had faced pressure to get the institute running, but the standstill continued even as his successor, Bok, took office.

Bok resumed the push to get the institute off the ground when he appointed a planning committee for the institute in 1973, and later, an advisory board in 1974.

The committee and advisory board’s membership bases — which largely precluded Afro-American department faculty and students — signalled Bok’s growing certainty about making the Du Bois Institute an independent entity.

An Embattled Department

The hesitancy of several faculty members and administrators for the Du Bois Institute to be founded under the Afro-American department stemmed from concerns that the department was not academically rigorous or well-managed under Guinier’s leadership.

The department came under fire after its founding in 1969. Guinier himself was an unusual figure in academia — after having been the only Black student in his class at Harvard before

transferring to the City College in New York to finish college, he spent much of his career as a labor activist and had an LL.M. from New York University but no Ph.D. Immediately, faculty members thought it was malpractice that students in Guinier’s Afro-American department could vote on tenured faculty appointments within the department. They believed professors would not be willing to let students interrogate them. There were also disagreements over the department’s academic rigor. While both Guinier and his opposition — faculty members outside of the department — thought Black students were not as well-prepared as white students for the academic rigor of Harvard, Guinier wanted to offer more remedial courses.

Gates characterized the disagreements as fundamental questions over how the department “should properly comport itself, who should be hired, what their credentials should be, what courses should be offered, how concentrations should be structured, and how tenure decisions should be arrived at.”

“I got the feeling that Professor Guinier felt under siege — that he was embattled,” he added. In January of 1973, tensions boiled over. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences passed a motion to restructure the department — discontinuing students’ ability to vote on faculty appointments and calling for the department to add more tenured faculty members — as well as specifying the Du Bois Institute be founded on a University-wide basis. Guinier, unsurprisingly, opposed the motion. The faculty had made their stance clear, and Bok would be tasked with navigating the SEE DU BOIS ON PAGE 7

THE HARVARD CRIMSON C LASS OF 1975 REUNION

1974-1975 Year in Review

Timeline

HARVARD’S CAMPUS IN THE REAL WORLD

Aug. 9, 1974

NIXON RESIGNS. Amid mounting pressure from the Watergate scandal, Richard Nixon becomes the first U.S. president to resign. Vice President Gerald R. Ford is sworn in as the 38th president.

Sep. 8, 1974

FORD PARDONS NIXON. In a controversial move intended to help the nation “heal,” President Gerald Ford grants Richard Nixon a full pardon for any crimes he may have committed in office.

Oct. 28, 1974

ID CHECKS BEGIN. In response to concerns about unauthorized access, Harvard Dining Services begins checking student IDs in dining halls, marking a shift toward more regulated campus services.

Nov. 5, 1974

DUKAKIS ELECTED. Michael S. Dukakis, a Harvard Law School graduate, is elected governor of Massachusetts, defeating Republican incumbent Francis W. Sargent.

Nov. 15, 1974

BIRTH OF A CONTROVERSY. After an October cancellation sparked by protests, the screening of Birth of a Nation in Science Center A reignited fierce debate over academic freedom and racial sensitivity. The film was criticized for its racist content and glorification of the Ku Klux Klan.

Dec. 2, 1974

BELL’S ULTIMATUM. Derrick A. Bell Jr., the only Black professor at Harvard Law School, threatens to resign unless the school takes steps to hire more minority faculty.

Feb. 6, 1975

JFK LIBRARY PLANS ALTERED. After a decade of planning, the Kennedy Library Corporation announces it will not build the museum portion of the complex on the Cambridge site.

Jan. 20, 1975

DYLAN RETURNS. Bob Dylan releases Blood on the Tracks, widely regarded as one of his greatest albums. Its raw emotional themes strike a chord with disillusioned youth and college audiences nationwide.

Feb. 11, 1975

THATCHER ELECTED. Margaret Thatcher is elected leader of Britain’s Conservative Party, becoming the first woman to head a major political party in the United Kingdom.

March 11, 1975

BURGER KING BACKS WOMEN’S ROWING. In a pioneering move for corporate sponsorship in collegiate women’s sports, Burger King sponsors the women’s heavyweight crew race between Radcliffe, MIT, and Boston University.

April 17, 1975

LAMONT SECURITY TIGHTENS. Following a reported sexual assault, Lamont Library relocates women’s bathrooms and installs combination locks to improve student safety.

April 30, 1975

FALL OF SAIGON. North Vietnamese forces capture the capital of South Vietnam, bringing the Vietnam War to a dramatic and definitive end. U.S. helicopters evacuate remaining personnel from the embassy rooftop.

May 2, 1975

DU BOIS SIT-IN. Students occupy Massachusetts Hall, demanding greater student involvement in shaping the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research.

Welcome, Alumni!

From the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard

Promoting and elevating the standards of journalism since 1938

Home to the Nieman Fellowships and our three publications: Nieman Lab, Nieman Reports, Nieman Storyboard

STORY 5

How Harvard Lost the JFK Library

and Harvard officials, and the Kennedy family and its allies sparred over the location and construction of the JFK Library — culminating, eventually, in the Kennedy Library Corporation electing to move the library out of Cambridge entirely.

BY ABIGAIL S. GERSTEIN AND THAMINI VIJEYASINGAM CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

When former Cambridge City Councilor David E. Clem was a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he found himself in the office of Massachusetts Senator Edward M. “Ted” Kennedy ’54-’56.

“I was 24 years old. I had never been invited to a senator’s office — much less Ted Kennedy’s office,” Clem said.

In 1974, Kennedy invited Clem, who was president of the Riverside Cambridgeport Community Corporation, along with other community leaders to discuss plans for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library to be built near Harvard Square.

The meeting came more than a decade after President John F. Kennedy ’40 originally announced that Harvard University would be the location of his archives and Presidential Library in 1961.

But in the end, the JFK library at Harvard never came to be.

When Kennedy, a former Crimson Business associate, visited Harvard in 1963, he originally preferred a location across from Eliot House, on what is now John F. Kennedy Street, for his library and archives.

The land, though, was owned by the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority — and Kennedy, recognizing that it may be too expensive, decided that a different location, across the Charles River next to Harvard Business School, would do. Following the President’s assassination in Dallas in November 1963, plans for the library were expedited. In the wake of his death, the decision was clear: the library must be built in the original spot President Kennedy wanted. It was also a larger site, allowing for the construction of a proposed Institute of Politics dedicated to Kennedy’s memory. The state government bought the land from the MBTA and donated it to the federal government, which manages and administers presidential libraries.

But obtaining the land was the first obstacle — plans to build the library in its location were met with fierce community opposition. Over the next 12 years, organizers, local

The saga was a series of “endless little mini controversies,” Nicholas B. Lemann ’76, a former Crimson president, said. “The usual kind of NIMBY type stuff, neighborhood opposition, historic preservation issues, et cetera.” When the Harvard Class of 1975 arrived on campus in the fall of 1971, construction of the Kennedy Library was still yet to begin — and for four years, the debate over its location would escalate.

Just a few months before their graduation, in February 1975, the Kennedy Library Corporation announced that the library would not be built on Harvard’s campus, instead choosing to begin construction at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in Dorchester. Clem says his main takeaway from the 1974 trip to Ted Kennedy’s office came from the actions of his fellow organizers, not the senator.

“I was more than awestruck by the notion that these neighborhood groups were steadfast in their opposition and took on some pretty formidable people,” Clem said.

The President’s Pick

In 1963, three years into his presidential term — and just over a month before he was killed — Kennedy toured Harvard with then-Harvard President Nathan M. Pusey, Class of 1928, and other city officials, to select a site for his presidential library.

The group examined several potential lots across campus, and Kennedy’s favorite spot was across the street from Eliot House — where, 15 years later, the Harvard Kennedy School of Government would stand. However, the 12-acre site was being used by the MBTA to house its repair and storage yards, and was unwilling to sell the plot. So Kennedy settled for the site off Western Avenue across the Charles River, opposite Winthrop House, where he lived as an undergraduate.

But his assassination a month later sent the nation reeling and made demand for a memorial to honor him even greater. The library, which was originally planned as a base for the President to retire to academia after he retired from politics, became a necessary tribute for a grieving America.

Following Kennedy’s death, then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy ’48 said his brother “has

been deprived of the personal enjoyment of such a library, but its speedy completion would be his dearest wish.” Just two weeks after the president was shot, Harvard and the Kennedy brothers announced a drive to raise $6 million to build the library at its Charles River location.

In 1964, after Kennedy’s assasination, Harvard professors suggested including an “institute” as part of the library complex, with the vision of bringing together politicians and scholars.

At the time, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. ’38, who had served as special assistant to the President and was on the JFK Library Corporation, said it would realize a solution to one of Kennedy’s greatest concerns by “bringing together the world of ideas and the world of affairs — the world of scholarship and the world of decision.”

But the same year, officials became concerned about whether there would be sufficient space for the library, the institute, and the museum on the two-acre Western Avenue plot. Pusey said he did not think that Harvard would be able to give more land to the Kennedy Library, while the Kennedy family felt the existing plot was too small.

“Harvard wanted the archives, and that was sort of the crux of the dispute. Harvard didn’t want to deal with, as somebody said, the visitors and the tourism around a presidential library, they wanted the prestige of the archives,” Robert J. Rosenthal, a former Boston Globe reporter who covered the Library’s construction, said.

After negotiations with Boston city officials, the MBTA yards were transplanted elsewhere for a hefty $53 million, and the site — the one Kennedy had initially wanted but felt would be too expensive — was freed up for the library.

Local Backlash

According to most contemporary reporting, the fiercest and loudest opponents of the library were a group of residents who lived in or near Harvard Square, in the area between Brattle Street up to Sparks Avenue, referred to as “Neighborhood 10.”

The residents campaigned against the library’s construction, arguing that it would bring unsustainable amounts of tourism and traffic congestion into Harvard Square.

According to Thomas P. O’Neill III, a former Massachusetts lieutenant governor, opposition by resident groups like Neighborhood 10 raised questions about the purpose of Harvard Square and the nature of the library and museum.

“Was Harvard Square going to be for academics and scholars, or was it going to be for the public at large?” O’Neill said.

Graham T. Allison ’62, a former HKS dean, also said the backlash came mostly from the Cambridge elite.

“I remember one wife of a business school professor at one of these hearings,” Allison said. “She said, ‘there’ll be people bringing RVs from Oklahoma wearing Bermuda shorts, and that’ll ruin Harvard Square.’” Others, though, say that resistance to the JFK library did not only come from the wealthy Brattle Street crowd, pointing instead to local organizers in the Cambridge area.

“The majority of opposition to the Kennedy Library came from the Riverside, Cambridgeport, and mid-Cambridge neighborhood, not Brattle Street,” Clem said. “In fact, when we were invited to meet with Senator Ted Kennedy, there was no one from the Brattle Street Neighborhood Association involved in that.”

According to Clem, the fight against building the JFK Library at Harvard was led by former Cambridge City Councilor Saundra M. Graham.

Graham was a longtime activist who had battled Harvard before. In 1970, she stormed the stage at Harvard’s Commencement, calling for the University to support more low-income housing in Cambridge. The stunt led to a meeting between Graham — who would become the first black woman Cambridge City Councilor — and members of the Harvard Corporation, the University’s highest governing body. Eventually, she secured more low-income housing with Harvard’s support.

Graham represented Riverside, which was predominantly Black and low-income. For her, construction of the JFK library was another Harvard encroachment into local neighborhoods that would push locals out and drive up rent prices — the kind she had protested just a few years earlier.

Albert C. Pierce, a consultant to the JFK Library Corporation at the time, called Graham’s claim a “neat juggling act” in an interview with Esquire magazine, as the Neighborhood 10 organizers asserted that the library would devalue their properties, seemingly a contradiction.

Despite the residents’ frustrations, both the University and local political leadership were in support of the library being located in the Square.

“Others, both in the City Council and within the political framework

of leadership, were very much in favor of it, not because they were Kennedy fans, but because they thought it was going to be good for the city of Cambridge,” O’Neill said. Meanwhile, Neighborhood 10 held a series of public hearings and gathered signatures to showcase opposition to the library.

“They gathered signatures, and the signatures were aimed at impressing upon the Cambridge City Council and whomever that it was too small of an area,” said Mike Barnicle, a former columnist at the Boston Globe, “to place a library that would have a huge impact.”

‘A Slow, Public Death’

“Little mini controversies,” however, continued to plague the JFK Library development.

The corporation had hoped to open the library by 1976, in time for the U.S. bicentennial — and had hoped to break ground far earlier. But through the early 1970s, construction of the library faced obstacle after obstacle.

In May 1973, architect I.M. Pei revealed his first design for the former MBTA location. But his design received massive public backlash.

Pei proposed an eighty-five foot tall glass pyramid, which architectural critics reprimanded, and buildings of poured concrete, which community groups deemed unseemly for the predominantly brick Harvard Square neighborhood.

Pei would eventually unveil a new design a year later, with brick buildings and no glass pyramid.

But the damage had been done.

That year, construction opponents proposed splitting the institution: Harvard would keep Kennedy’s archives, but the museum would be moved to the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Meanwhile, the government was still preparing an environmental impact report, which had already delayed construction as buildings at the MBTA site could not be demolished until the report was released.

When the report was finally released, in January of 1975, the General Services Administration found that the library’s impact would be minimal. Opponents remained skeptical, and The Crimson reported that JFK Library officials had viewed the report before it was public, dealing a huge blow to the report’s credibility.

On February 6, 1975, Stephen E. Smith, the late President’s brotherin-law and head of the JFK Library Corporation, announced that neither the Kennedy Library nor the museum would be built in Cambridge.

“It just died a slow public death,

as far as the library being located in Cambridge,” Barnicle said. The Kennedy Library would eventually be built on the UMass Boston campus, at Columbia Point — a location chosen by Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline L. “Jackie” Kennedy Onassis, who chose it because it would allow the library, museum, and archives to remain in one location.

“If you had said 10 years earlier, or 12 or 15 years earlier, that the Kennedy Library was going to go at Columbia Point, people would have laughed at you,” O’Neill said. “It just was going to be a ridiculous place to put it, because it had nothing to do with Jack Kennedy. It wasn’t in his congressional district, it wasn’t part of the Harvard that he wanted connected to the Kennedy library.” But the failure to bring the Kennedy library to Harvard was not the end of the road for a memorial to the president at his alma mater. The University had long been assessing how to honor its beloved alum beyond the construction of the library. Just days after Kennedy was killed, undergraduate House committees suggested naming what is now Mather House after the slain President, and the Harvard Corporation agreed to consider the proposal.

While that never materialized, the University did rename its Graduate School of Public Administration for Kennedy in 1966, dubbing it the John Fitzgerald Kennedy School of Government. Eleven years later, the Kennedy School and the Institute of Politics moved to a new location — at the site across from Eliot House where the Kennedy Library was supposed to be built. The new building was dedicated in October 1978, in a ceremony attended by Ted Kennedy — who acknowledged his fight to bring the Kennedy Library to Cambridge in his speech at the event.

“Once, not long ago, Jack and all the others in our family had a different dedication in mind for this beautiful University site. But Harvard is a house of many mansions.

“When

Admitting More Women to Harvard

THE STRAUCH COMMITTEE. The 1970s brought a fierce new debate: should Harvard should equalize its gender ratio?

BY STEPHANIE DRAGOI CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

When the Class of 1975 arrived at Harvard in the fall of 1971, the school enrolled men and women at a ratio of 4 to 1, enforced by the University’s president. But by the time the class left, mandated gender ratios were on their way out.

Harvard President Derek C. Bok began his tenure just as the class of 1975 arrived on campus, and immediately went about equalizing access for men and women — who were still technically students at Radcliffe College, though they lived in co-ed dorms and studied with men. In the fall of 1971, Bok announced that the ratio would be lowered from 4 to 1 to 2.5 to 1. But it was in 1974, when Bok and Radcliffe President Matina S. Horner — who had assumed office just two years earlier — created a committee to consider admissions reforms at Harvard and Radcliffe, that Harvard took a serious step toward total equality between the two schools.

The relationship between Har-

vard and Radcliffe was radically transformed in 1969, when the two institutions began to merge. Though classes became co-ed in 1946, the residential unification of undergrads took shape in the 1970s, when upperclassmen Houses were integrated in 1971 and freshman dorms in 1972.

The two institutions also came to a temporary compromise in 1971 over administrative consolidation, dubbed the “non-merger merger,” under which Harvard would assume Radcliffe’s debts and begin administering other parts of the school.

But the non-merger merger avoided the thorny question of a gender ratio — the very question that Bok and Horner tasked 16 faculty, administrators, alumni, and students, led by Physics professor Karl Strauch, with studying in January 1974.

For the next year, the committee — which, along with students and faculty, featured the Harvard and Radcliffe deans of admissions and financial aid, as well as the deans of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard College, and Radcliffe College — worked to determine whether to maintain separate Harvard and Radcliffe admissions offices and what gender ratio the College should enforce.

Renée M. Landers ’77, one of the four student members of the com-

mittee, said that many representatives were concerned about how a more united admissions process would affect various parts of the University, including its financial health.

“There were discussions and concerns about, is it going to affect fundraising?” Landers said. “There were concerns about development risk.”

If Harvard admitted fewer men, some administrators and faculty worried, it could see donations plummet in the future because alumnae might have lower earnings and less control over their money than male peers.

Robert L. Schram ’76, another student member, said that other members were concerned about the state of Harvard’s athletics, as some representatives “worried about not being able to have a strong football team or how we were going to field teams for all of our sports.”

The issue that split the committee, though, was expanding the size of the undergraduate body. While Chase N. Peterson ’52, then Harvard’s vice president for alumni affairs and development, advocated strongly for an expanded class size, the four students fiercely resisted.

Peterson argued that if the number of men at Harvard decreased — which would happen if more women were admitted but the class size

did not increase — donations to the University would be seriously jeopardized. But the students felt that Harvard did not have the resources to enroll more students.

“I think the feeling was that Harvard was already, in some ways, a big, impersonal kind of place, and that expanding the class size would only make that worse,” Landers said. “I think there was a feeling that it would reduce that kind of intimacy.”

“My pet peeve at Harvard was class size, interaction with professors, the predominance of teaching by grad students rather than professors, things like that which affected the college experience,” Schram said.

According to Schram, Radcliffe’s smaller class size meant that “by being at Radcliffe and being a part of Radcliffe, you had a more intimate college experience than Harvard.” Preserving that feeling, and Radcliffe’s institutional heritage, became a focus for some of the school’s representatives on the committee.

Though Schram said the student members “felt a little bit like fish out of water” in a body full of Harvard’s top officials, both Schram and Landers said that they felt their voices were respected on the committee, which Schram said was “remarkably collegial and cordial.”

“I think just everybody, everybody knew that the world was changing and that things could not go on as they always had gone on,” Landers said. By February 1975, after over a year of work, the Committee was preparing to issue its final report. When it was finally released, it contained several major policy recommendations, including an “equal access admissions policy” and the unification of the Harvard and Radcliffe admissions offices.

The committee also proposed increasing recruiting efforts for women, particularly with a focus on attracting women scientists, increased female representation among faculty and administrators, and equal access to prizes, fellowships, and athletic facilities — all without increasing class size.

But despite the tectonic shift, the proposal proved to be noncontroversial. In April 1975, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences voted nearly unanimously to approve the Strauch committee’s recommendation for equal access admissions, and Harvard’s and Radcliffe’s governing boards followed suit in May. Effective with the Class of 1980, a merged Harvard-Radcliffe admissions office would give men and women equal access in admission.

Still, despite the monumental step towards a total merger,

Schram said that the student body was “oblivious” to the work the Strauch Committee was doing. “This was all sort of driven not by the students. This was something that needed to be resolved amongst the bureaucracy, the powers that be,” he said. But there was still a feeling that things needed to change, especially among the women on campus, according to Landers.

“It was a period of time when women wanted to be equal to men, and the same,” Landers said.

“There were some women in my class who deeply resented the fact that, because of the Radcliffe name, perhaps women could be viewed as kind of second-class citizens, not really Harvard people, but other people,” she added. Schram said that implementing the Strauch Committee’s recommendations helped lead to a more diverse Harvard today.

“People of my age at the time, 50 years ago, and people at Harvard were looking for a diverse experience,” Schram said. “We were looking for the melting pot experience at school, and to some extent we got it. To some extent, we needed to work more at it. And my sense is that Harvard did most of the things right that happened to where they are today.”

stephanie.dragoi@thecrimson.com

Class of 1975 Recalls Muhammad Ali’s Sold-Out Speech

BY SAMUEL A. CHURCH AND CHANTEL DE JESUS CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

Muhammad Ali was as surprised to be speaking to Harvard’s Class of 1975 as they were.

“You never could have made me believe years ago when I got out of high school with a D-minus average,” Ali told the soldout crowd of 1100 attendees at the now-demolished Burden Auditorium at Harvard Business School. Over the course of the next 30 minutes, Ali captivated the crowd with personal stories and his own opinions on the pressing political issues of the time, including the fight for racial equality and the war in Vietnam, which ended weeks before Ali took the stage at Harvard in June 1975.

“I remember getting in there early so I could get a place in the front row,” Paul N. Samuels ’75 said. “And then I remember Ali coming in, and his whole spiel, his whole speech was hilarious,

mesmerizing, spellbinding.”

“I’d seen him many times on TV, but to be in his presence, there was some really amazing, special aura about Muhammad Ali,” he added.

But Ali’s speech — which has had a lasting cultural influence and is remembered today for producing one of the shortest poems in the English language — almost never happened.

The Class of 1975 invited Ali to speak at the annual Class Day celebration after Mel Brooks and Bill Cosby declined invitations. But a few weeks later, Ali — who had regained his heavyweight championship title just months earlier after defeating George Foreman in the “Rumble in the Jungle” — informed the class committee that his training schedule would prevent him from coming to Cambridge, as he had to head to Kuala Lumpur to defend his title.

The Class of 1975 eventually invited the social satirist Dick Gregory to speak at Class Day, held for the graduating under-

graduate class the day before the University’s Commencement.

But Ali was able to reschedule his speech to a week earlier, albeit at the much smaller Burden Auditorium instead of the traditional Class Day venue of Harvard Yard.

The speech was a hit.

“To get something together to talk to these people, it’s gotta be pretty heavy,” Ali began. “So, I didn’t bring no notes with me.”

For thirty minutes, an animated Ali philosophized on friendship and racial tensions.

“I don’t do no Uncle Tom-ing. I don’t do no shuffling,” Ali said. “The Ali shuffle, but I don’t do the Tom shuffle.”

He then proceeded to perform the Ali shuffle — one of his signature moves from the ring — for the overflowing crowd.

John S. “Jack” Mills ’75 said it was Ali’s position as a political dissident that made his speech a “great honor.” Ali, Mills said, was “a great boxer, but also a great wordsmith.”

“He said that he would never

do the Uncle Tom shuffle,” Mills said. “Which meant to me that he would never act like he would diminish himself for white racists, and only do the Ali shuffle.”

In one of the speech’s most notable moments, someone in the crowd yelled at Ali to “give us a poem.”

What Ali said next is still unclear. The Crimson’s report from that day noted that Ali replied with “Me? Whee!,” while many observers have recorded Ali’s reply as “Me. We.” Ali’s response has been called one of the shortest poems in American history.

Samuels wrote in an email that fifty years later, “Ali’s Class Day speech remains very relevant and inspirational to this day.”

“His humor, optimism and belief that you can accomplish anything you want in life, as exemplified by his own experiences, are as uplifting now as they were then,” he added.

samuel.church@thecrimson.com chantel.dejesus@thecrimson.com

Service and Action: PBHA Becomes Political

CIVIC SHIFT. In 1975, PBHA’s student leaders merged public service with political action in the wake of 1960s activism.

BY SHAWN A. BOEHMER AND GRAHAM W. LEE CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

Harvard’s class of 1975 made its way onto a campus newly shaped by the student activism of the previous decade. The Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War catalyzed student organizing — a change reflected in the increasingly political environment of the Phillips Brooks House Association.

“This is a particularly politically active period for students on campus — and who can blame them for wanting to speak up and be out on the street?” said Douglas M. Schmidt ’76, PBHA president from 1975 to 1976. “That gets reflected in student-run, student-organized, student-created programs.”

Since its founding in 1904, the PBHA has served as Harvard’s flagship service organization — a place where students could give back to their city, tackling social issues through volunteer work.

But in 1975, the service organization expanded its mandate — reorienting its volunteer programs to address social issues at both the national and local levels.

Stephen D. Cooke ’75, PBHA president from 1974 to 1975, said that increasing student activism brought political issues — like affordable housing, prison reform, and educational equity — to the fore. Students in Phillips Brooks House began to think that simply volunteering to serve individuals would not be effective in the long term, so they started thinking in political terms instead.

“One aspect of that was the sense that unless you looked at a broader picture and a broader impact, you really weren’t affecting any meaningful change,” Cooke said. “Should we not be fo -

cusing on something that potentially has broader impact, or can broaden the impact of what we do?”

“You’d have this debate between – I never really liked the terminology – but social service versus social action,” he said.

The debate between service and action at the PBHA led both leadership and members to emphasize political activism in their volunteering efforts.

“We can be most effective if we’re able to establish partnerships, build alliances, identify what aspects of our clients’ lives are impacted beyond the narrow perspective we might have,” Cooke said.

This political activism came to the fore with PBHA’s work at Bridgewater State Hospital, a facility for individuals with severe mental illnesses and pending criminal charges. Cooke said his work on PBHA’s prisons committee evolved from weekly tutoring to informing inmates about their constitutional rights.

“I started going there, teaching classes in any of a number of different subjects, largely driven by what the students were interested in,” he said. But Cooke added he was concerned by the apparent overmedication of inmates as the “main way of control” in the facility. Cooke discussed his concerns with a member of the Massachusetts chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, who gave him their pamphlet on inmates’ rights to distribute to his students.

“I come into class and I bring a bunch of these copies and distributed to them, saying, ‘This is helpful information for you to have, so you know what your rights are,’” he said. “When the prison superintendent found out about it, I was banned from going back in there to teach.”

The Massachusetts ACLU then sued on his behalf.

While Cooke still values his experience volunteering at Bridgewater, and thinks it was valuable for the men he worked

with, he said his work informing inmates of their rights — and then fighting for his own in court — helped address a “far greater problem.”

“There were other things that could have had a greater impact that really needed to

be done — they would have a greater, longer-term impact on them and other people that had to go through that system, that couldn’t be navigated in that fashion,” Cooke said.

PBHA has significantly evolved in the 50 years since

Cooke and Schmidt served their presidential terms — leaning into the social action and political advocacy catalyzed in the 1970s. Schmidt said he was “proud” of the PBHA’s work, and long-lasting impact on students’ lives.

The Battle Over the Du Bois Institute

conflicting visions held by the faculty within the field.

Bok’s Recourse

Just two months after the faculty vote, Bok appointed a seven-member planning committee for the institute, which was chaired by Walter Leonard, special assistant to Bok, and consisted of several professors, including Guinier and Preston N. Williams, a professor in Religion.

In December of 1973, the committee proposed several recommendations: calling for a multimillion-dollar capital fund for the institute, an advisory board composed of Harvard faculty and “other members of the black community,” and a director to lead the institute.

Guinier and his student supporters vehemently opposed the proposal because it did not state that the institute would have any connections to the Afro-American department.

But Bok seemed to be taking the side of faculty outside the department. When he established a University-wide advisory board for the institute in September of 1974, he did not choose any Afro-American department faculty members — leaving Guinier furious.

In a letter to Bok, Guinier alleged that Bok’s administration had committed “glaring violations” because he believed the 1969 faculty legislation — which stated that the institute should be run by the executive committee of the Afro-American department — was a promise for department representation in the institute’s planning.

Bok turned to his advisory board for guidance after Guinier’s criticism. In particular, Williams said he

crafted a separate report for Bok after consulting with people involved in the controversy, which convinced the president to follow through with founding the Du Bois Institute entirely independently of the Afro-American department.

“I created the document after that set of discussions and presented it to Derek Bok and that brought the Du Bois Institute into existence,” Williams said.

“The institute came into existence after I recommended the severing of it from the department,” he said.

He said he thought splitting the institute from the department would cause “some anxiety,” but that the two entities would ultimately come back together.

After private meetings with Bok in the months leading up to May of 1975 — when the institute was officially founded — Williams said Bok accepted his proposal.

“Rightly or wrongly, I believe, if I had not taken care of that problem that Derek Bok inherited, there may not have been a Du Bois Center,” Williams said.

Williams, who served as the institute’s director from 19751977, said he didn’t know all of the factors Bok had taken under consideration or what ultimately tipped the scales, but “I can only indicate that the action that he took was not taken until after he received the report from me.”

Bok declined to be interviewed for this story, writing that he could not recall specific details on how the Du Bois Institute was founded.

“It changes their lives, and they become great citizens and board members and volunteers all of their lives,” he said. “They give back.”

shawn.boehmer@thecrimson.com graham.lee@thecrimson.com

The Birth of the Du Bois Institute

As Bok finalized where to house the Du Bois Institute, his advisory board was negotiating how to fund it. In January of 1975, the board obtained the institute’s first grant — $72,000 from the Henry Luce Foundation of New York to support graduate students’ dissertation work. The funding paved the way for the advisory board to announce four fellowships, $5,800 each,

Gates said the institute’s independence from the department was an “act of protest against the practices that were unfolding in this brand new department of Afro-American Studies.”

for graduate students pursuing Ph.D. theses in fields “relating to Afro-American studies,” in May of 1975. The board solicited applications and started awarding the fellowships.

After six years of drawn-out controversy, the institute had finally come to life.

“The institute is now a reality,”

Andrew F. Brimmer, then-chairman of the advisory board, said on May 1, 1975.

But controversies persisted in the months and years to come. Students inspired by Guinier held protests and occupied Massachusetts Hall to protest the in-

stitute’s detachment from the Afro-American department and lack of undergraduate representation. After years of conflict, the department and institute were eventually reunited in 1980 under the leadership of Nathan I. Huggins, who served as chairman of the Afro-American Studies department and director of the Du Bois Institute. While Gates recalled stories about the “bitterness and anger among the two factions” while the Du Bois Institute still operated on its own, he said the institute thrived in its early years because

of Higgins’ scholarship and its awarding of fellowships to leading scholars. And not even the limited space the Du Bois Institute had could deter its momentum, Gates said.

“Although it didn’t have, shall we say, adequate space — it was housed in the basement of Canaday Hall — the Du Bois Institute, overnight, became the leading research institute in the field of African American studies in the United States,” he added.

claire.jiang@thecrimson.com cam.srivastava@thecrimson.com

How Bill Gates Began Microsoft at Harvard

House grille with future Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer ’77 at all hours of the night. He also played in late-night poker games with other Currier residents, though not with particular success.

“We played poker starting at typically nine o’clock at night, and then played through till 7:00 a.m., more so to have breakfast, and then go to sleep and wake up in the afternoon for afternoon classes,” said Robert F. Margolskee ’75, another Currier resident who is now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school.

It was at those evening hangouts that Gates expressed his frustration with his classes conflicting with his growing company.

“I remember him speaking of having ‘ideas’ he wanted to carry out in the world, and he was feeling frustrated that he felt ‘too tied up with classes’ to do them yet,” fellow Currier resident Leszek Sachs ’75 said.

‘What Are You Doing On This Computer?’

Gates spent countless hours working at Harvard’s PDP-10 mainframe, initially with permission — but eventually far beyond what administrators expected.

“I was messing around, doing a lot of things, and eventually I’m bringing in another stu -

dent, Monte and Paul, to help me write the BASIC interpreter, just the first Microsoft product,” Gates said. Allen, Gates’ childhood friend from Seattle and future Microsoft co-founder, was not a Harvard student. But the two remained close, and Allen made regular trips to Cambridge. It was halfway through Gates’ sophomore year when Allen first spotted the Altair 8800 — the first commercially available personal computer — on the cover of Popular Electronics, purchased at a Harvard Square newsstand.

“He buys this magazine that has on the cover the very first personal computer,” Gates said.

“And it’s a cold Boston winter, and he says, ‘Here we are freezing to death, and the revolution has happened without us.’”

Eager to join that revolution, Gates and Allen called Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems — the makers of the Altair — to pitch a beginner friendly programming language called Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, known as BASIC, for the Altair. MITS responded by asking for a working version, but neither Gates nor Allen had an Altair to begin with. What they could not buy, they emulated with the Harv-10. With Davidoff, who got involved over a conversation about Gates and Allen’s project over dinner

in the Currier dhall, Gates and Allen began working around the clock to develop their version of BASIC for the Altair in the Aiken Lab.

“To me, it was just a side project,” Davidoff said. “I was completely unaware of what Microsoft could become now.”

The trio’s work consumed an enormous amount of computer time on Harvard’s PDP-10.

According to Davidoff, sys -

ing a huge amount of computer time.”

“They were kind of aghast,” Gates said. “They called me up, and they’re like, ‘Who are you and what are you doing on this computer?’”

The PDP-10 at Harvard was partially funded by the federal government to support military-related research and development, though it was also used for other purposes like

I remember him speaking of having ‘ideas’ he wanted to carry out in the world, and he was feeling frustrated that he felt ‘too tied up with classes’ to do them yet.

Leszek Sachs ’75 Fellow Curier House Resident

tem usage logs flagged Gates for an outsized share of resources and their work on the computer was brought to the Harvard College Administrative Board, tasked with dispensing discipline.

“At some point they had accounting software running that said how much each user used,” Davidoff said. “And at some point, the administrator of that system noticed that Bill was us -

game development. Gates allowing a non-student Allen to use it was a violation of the University’s policies.

The Board ultimately allowed Gates to stay — but barred him from letting Allen and other non-students onto the system. “It was a little scary,” Gates said.

Gates also agreed to place an earlier version of the BASIC interpreter into the public do -

main — but not the version the trio had developed for Microsoft.

Their interpreter made the Altair functional and accessible for non-specialists, transforming it from a machine for hobbyists into one of the first truly usable personal computers.

That software became Microsoft’s first product.

‘Told You I’d Come Back’

Gates officially left on a leave of absence in spring of his sophomore year. He came back for a brief stint in the spring and fall of 1976 before permanently moving to Albuquerque, where his business was growing. He was two semesters away from graduating before leaving Harvard for good.

“It’s not risky to drop out because you can always come back,” Gates said. “What’s risky is when you start hiring people who move their families and they expect you to pay their salary.”

Though he formally left, Gates never quite considered the decision permanent. “I said I’m going on leave,” he said.

“Even Harvard had me marked down as being on leave.”

He never completed his degree, but Gates’ connection to Harvard only deepened in the decades that followed.

In 1996, Gates and Ballmer — a former Crimson advertising

manager — donated $25 million to support Harvard’s computer science and electrical engineering programs.

The gift funded the construction of the Maxwell Dworkin Laboratory, named in honor of their mothers, Mary Maxwell Gates and Beatrice Dworkin Ballmer. The building, completed in 1999, remains a key hub for the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

In 2000, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation also awarded a five-year, $45 million grant to a Harvard Medical School program targeting multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru — one of the largest single grants in the school’s history at the time.

Gates has returned to speak at Harvard on several occasions,

The Humble Origins of Ben Bernanke ’75

But according to Bernanke, his success in his field — and at Harvard — was far from obvious. He said the transition to Cambridge was difficult, both culturally and academically, and went home after his first semester unsure if he could “hack it” at Harvard.

But classmates from Ec 10 said that by sophomore year, Bernanke was already leagues ahead.

As a still-undecided sophomore, Ben S. Bernanke ’75 did what hundreds of Harvard students have done for decades: enroll in Economics 10, the school’s introductory economics course sequence.

“I didn’t know whether I wanted to do science or humanities or what. I went from thinking about physics and math to going to history to English, and I really couldn’t find a home,” Bernanke said.

The Winthrop House resident, who had arrived a year earlier from the small town of Dillon, South Carolina, would leave the course intent on pursuing economics — and took the first steps down the path that would one day culminate with him at the helm of the Federal Reserve.

“I decided at the end of my sophomore year, having taken only Ec 10, that I would major in Economics,” Bernanke said. “My junior year, I just took nothing but Economics.”

Over the next two years, the future Fed chair would diligently pursue his economics studies, writing an award-winning senior thesis and eventually graduating Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude. After obtaining his Ph.D. from MIT four years later, he taught at Stanford and then at Princeton, spending more than 20 years as an academic.

In 2005, Bernanke pivoted to government work, first with a seven-month stint as chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors before becoming chairman of the Federal Reserve in 2006 — just two years before the United States plunged into the Great Recession. For his role in steering the Fed’s response, he was named Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in 2009, before winning the Nobel Prize in 2022 for his research on financial crises.

Suzanne P. Bishopric ’75, who took Ec 10 with Bernanke, recalled that he somehow “seemed to know things that were in the next chapter of the textbooks” and would probe their professors about past policy decisions.

“He would ask questions that made you think a little bit differently,” Bishopric said. “What other paths might have been taken?”

“He would always come up with another angle, ‘What if they had done this, or why, or whatever’ — because he knew what the options were,” she added.

Daniel I. Small ’75, a fellow Winthrop House resident, described Bernanke as “curious about everything” — not just about quantitative economics or academic theory, but its practical implications.

“There are a lot of folks who are brilliant in those kinds of fields, but not good at integrating that into the real world,” Small said. “And that’s not Ben. Ben was infinitely curious about how that technical world integrated with the real world.” Bernanke even saw everyday interactions through an economics lens, according to his Ec 10 classmate Mark S. Campisano ’75.

Campisano recalled walking along Holyoke Street to a lecture with Bernanke. At one point, Campisano stooped to pick up a nickel — only to be scorned by Bernanke.

“Ben said, ‘Huh — I never stop to pick up anything less than a dime.’ ‘Why?’ I asked. He replied, “Because my marginal cost would exceed my marginal utility,’” Campisano wrote in an emailed statement.

Campisano recalled laughing, and then dishing right back.

“‘Wow,’ I said. ‘Your utility curve is obviously shaped very differently from mine,’” Campisano wrote.

But despite his deep intellectu-

al passion for economics, Bernanke was “never a recluse,” according to his friend Ira J. Finch ’75. Finch said Bernanke often played saxophone in the Winthrop junior common room, accompanying Finch, a pianist.

According to Small, Bernanke could also have been found working at the Winthrop Grille, playing cards to the tune of ’70s rock and roll, or grabbing roast beef sandwiches from Elsie’s, a popular joint on Mount Auburn Street.

Still, Bernanke acknowledged that he remained focused on his academics.

“I was pretty focused on work, and I wanted to make up for what I felt were the deficiencies of my high school education,” Bernanke said. “So I spent a lot of time on that.”

In his junior and senior years, Bernanke narrowed his focus,

working primarily under the guidance of the prominent economist Dale W. Jorgenson.

Jorgenson, who taught econometrics to Bernanke during his junior year, took Bernanke under his wing, hiring him as a summer research assistant and bringing him along when Jorgenson testified before Congress on natural gas price controls.

“I still think it’s incredible, because I didn’t know anything,” Bernanke said. “He was just a great mentor, very kind to me, even though he was a big shot and I was just a junior.”

Jorgenson, though, thought Bernanke was an exceptional talent, telling the New York Times in 2008 that his former student “was the superstar of all time as an undergraduate.” Under Jorgenson, Bernanke wrote his senior thesis,

focusing on the deregulation of natural gas — an uncommon position at the time, until the United States liberalized the natural gas market in 1978.

That was the role Bernanke expected to play, he said: an academic who spent his time researching public policy, not necessarily creating it.

“I was doing monetary policy because I thought it was important from a public policy point of view,” Bernanke said. “I had no intention or no expectation that I would ever be doing it myself.”

But when he received a phone call “out of the blue” in 2002 to interview for a position on the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors, Bernanke said he couldn’t turn the opportunity down.

“I kind of figured that if I’m going to be studying this topic and I have

the opportunity to put it into practice, I really ought to do it,” he said. Small, Bernanke’s friend from Winthrop House, agreed that Bernanke was “most comfortable in the academic world” — and in a sweater and khakis rather than a suit. But Small said Bernanke’s characteristics predisposed him to success as Fed chair, even if Bernanke himself never expected

ty, and humility — I’ve met people with one of those qualities, but Ben has all three.”

It wouldn’t be wrong to call Harold H. Koh ’75 a one-draft wonder. After two consecutive all-nighters, Koh wrote the final chapter of his senior government thesis in the hours before it was due, enlisting his roommate, John W. Treece ’75, to type as he penned a draft by hand.

“It was pretty incredible, even mesmerizing, to watch his ability to churn out a first draft that easily passes as a final product,” Treece said. “He was that good.”

Once Treece left, Koh pounded out the remaining pages on his rickety Royal typewriter, dashed to the Holyoke Center, and submitted the thesis with 15 minutes to spare.

“I thought, ‘Oh, that’s terrible,’” Koh said. “But anyway, it all turned out well.”

“Well” was an understatement. Koh’s thesis — on the South Korean role in the U.S.-Japan-Korea trilateral relationship — was awarded summa cum laude, the highest possible distinction and the first in the Government Department in years. The accolades did not stop there. After graduating from Harvard, where he lived in Mather House, Koh won a Marshall Scholarship and studied at the University of Oxford, then earned his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1980. Before joining Yale’s law faculty in 1985, Koh clerked on the D.C. Circuit and for Supreme Court justice Harry A. Blackmun, Class of 1929, as well as working at the prestigious law firm Covington & Burling and the Department of Justice. At Yale, Koh became a professor of international law and a leading voice in shaping the future of global legal norms,

serving in both the Clinton and Obama administrations. He became dean of Yale Law School in 2004, leaving when Obama appointed him as a legal adviser to the U.S. Department of State. But Koh still bled Crimson, serving a six-year term on the Harvard Board of Overseers, the University’s second-highest governing body.

The frenetic pace that has carried Koh from Yale to Washington, and countless stops in between, found its roots in his time at Harvard, when he pivoted from majoring in Physics to Government and often churned out papers in the dead of night on his typewriter.

Yet friends recalled him as an affable teenager — Koh was only 16 when he arrived at Harvard — already adept at navigating diverse social situations.

Treece said from his early days in Cambridge, Koh had a “Bill Clinton-like recall” for everyone he met, while his fellow roommate Clifton G. “Cliff” Lewis ’75 said that Koh possessed a “Robin Williams-quick” wit.

“He was very outgoing, interested in people, interested in their worlds,” said Catherine E.M. Sullivan ’75, a fellow resident of Mather House. “He could always collect a story about you, and he could tell you stories about anybody.” On any given night, Koh could be found playing on the Mather House pinball machine and then whipping up a 15-page essay. And if he wasn’t chasing high scores, he could be found singing with the Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum and trekking across the Charles to watch Marx Brother movies, according to roommate David S. Edgell ’75. Yet that easygoing charm masked a scholarly intensity he hadn’t fully realized when he first set foot on campus. He began as a physics concen-

trator, but stumbled upon an East Asian politics class in the fall of his sophomore year — and never looked back.

The shift felt almost predestined: Koh was the son of Kwang Lim Koh, a former Korean diplomat to the United States who was the first Korean to receive a master’s and doctorate degree from Harvard Law School, while his mother was one of the first women to earn a Ph.D. in sociology from Boston University.

“It seemed like an accident,” Koh said of his switch to concentrating in government. “But for all those reasons, I was very interested in politics, political side, it was just much more natural to me.”

Even as Vietnam War protests erupted steps from his dorm, Koh largely avoided the activist fray and engaged little on political matters, even with his closest friends.

“Whenever politics came up, we just nodded and agreed and then moved on to ‘when’s the next Glee Club rehearsal?’” Lewis, Koh’s roommate, said.

While Koh said that he didn’t develop his core values at Harvard and found friends who already had “very strong moral centers,” he did learn what not to emulate: After some professors rebuffed his interview requests for a junior-year paper, he vowed to never shut down a curious student the way they did.

“These guys were very arrogant, and it turned me off,” he said. “I just thought, ‘you don’t have to do that — why do you make people feel small?’” Koh said.

Koh said the most important book he read as an undergraduate student wasn’t a government treatise but the countercultural guide “Be Here Now” — a 300page tome that simply repeats “Be Here Now” in wild, swirling fonts. It was assigned by a gov-

ernment tutor who, Koh joked, was “stoned out of his mind.”

“I thought, ‘what a complete waste of time,’” he said. Still Koh said he leaned on that simple mantra in the race to submit his thesis — and today when speaking before students and lawyers.

“When I would be in some stressful legal situation, it would suddenly occur to me — just block out these other extraneous things,” he said. “‘Be here now,’ just give it everything you got.”

But, with what his friends might call characteristic humility, Koh claimed his success was less pre-ordained — and a lot more like a game of Mather House pinball.

“It’s very random, the way the ball bounces, but it’s sort of something about life — timing counts, anticipation counts, understanding the patterns counts,” Koh said. “And then there’s a lot of luck involved.”

Censorship

The demonstrators who prevented the showing of Birth of a Nation Saturday night at Adams House erred seriously. By using physical intimidation to stop the presentation, they ironically aligned themselves briefly with other, repressive forces that use strong-arm tactics to prevent free expression. This arrogant censorship contradicts basic principles espoused by the demonstrators, and has no place at Harvard or in any free community.

It is also ironic that the protest has accomplished the opposite of what the demonstrators intended. Discussion of racism in D.W. Griffiths’ film, at Harvard and in Third World countries — the announced purpose of the action at Adams House — has been eclipsed by widespread questioning of the methods the protesters used.

This is particularly unfortunate because much of what the demonstrating Organization for the Solidarity of Third World Students had to say about the film has merit. Opponents of racism have been voicing similar criticisms since the movie’s release in 1915. The Adams House film society displayed insensitivity by presenting the film in a forum — a series on early screen classics — that made a political discussion of this political film awkward. The offer that film society leaders made to let a spokesman for the demonstrators speak before the showing was a good-faith attempt to ease differences — but as William J. Fletcher Jr. ‘76, a protest organizer, observed, “To go in front of an audience that is prepared for entertainment and to talk about politics would cause problems.” The brief acknowledgement by a film society leader of the movie’s blatantly racist content, presented before the uneventful Friday night showing, was insufficient to dispel the

odor of some of the racial myths unabashedly portrayed.

But the demonstrators displayed a more serious insensitivity by assuming that the audience was not sophisticated enough to understand the movie in its proper context. A few cinema buffs conceivably could have been engrossed in the technical innovations, but, without doubt, leaflets, picketing, or a publicized boycott would have jarred even the most myopic D.W. Griffith fans, and given the screening a political meaning.

While preservation of First Amendment rights may allow racial pseudo-scientists — both dead and alive — to briefly gain an audience, unwavering protection of free speech has served the cause of racial justice far more than hurt it. Both the demonstrators and D.W. Griffith could have had their say Saturday night, and there is no doubt which side would have won the audience.

As it is, serious discussion of the racism in Birth

of a Nation — the demonstration’s goal — has been temporarily placed aside. A viewing of the movie could only have encouraged it. There was no danger presented by the audience — no one was about to rush out at the film’s conclusion to smash school bus windows with ax handles. Instead of analysis, there was a miscalculated victory chant for the demonstrators, and bitterness for those who had come to see the movie.

The most encouraging result of the discussions that followed the demonstration is the willingness of both the protesters and the film society chairmen to present a screening of Birth of a Nation with appropriate political analysis. It is doubtful that there will be any controversy about the movie itself; attacks on the film’s content have been uniform in the last 60 years. But whether or not any original analysis emerges, a peaceful showing and reasoned condemnation of Birth of a Nation will do much to wash away the sour taste of Saturday night.

The New York Times’s recent revelation that the Central Intelligence Agency systematically and illegally spied on American citizens provided additional evidence for a number of things people should have known already. It proved once again that Seymour Hersh is the most important reporter in the United States, and that high government officials like to ignore the more unsavory aspects of the unsavory policies they devise. And it offered one more reason for abolishing the CIA. Reports of domestic CIA spying have been current for years — the one case the Times cited, for example, was publicized by Jack Anderson sever-

al years ago. Even though the CIA need not account for its appropriations to anyone, responsible public officials could presumably have checked on CIA activities at least as easily as Hersh could-though that might have involved questioning the assumptions that led other high public officials, in the Johnson administration, to have the CIA focus on the United States as well as foreign countries.

On a fundamental level, these assumptions — that a. U.S.. enforced stability is always in everyone’s interests, and that that stability depends on the political success of whomever holds power in Washington — are the real issues in the Times’s revelations. These assumptions permitted the United States to use the CIA abroad in ways far more ruthless (and often successful) than anything it did at home — to overthrow the legiti-

mate government of Guatemala, to organize an invasion. of revolutionary Cuba, to mobilize a marauding army in the hills of Cambodia, and to subvert the freely elected government of Chile. Even now, there is no important move to prevent CIA activities like these, just as there is no inquiry into domestic spying, some of it conceivably at least quasi-legal, in general.

President Ford’s selections for his “blue-ribbon” commission are certainly unfortunate; choosing Ronald Reagan, Nelson Rockefeller and Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to investigate the CIA is like selecting Meyer Lansky, John N. Mitchell and a Mafia hit man to investigate organized crime. But Ford’s choices become more comprehensible if you remember that he defends American inter-

vention in Chile and always appeared to think that antiwar dissent bore close watching. No doubt he rightly believes that seriously questioning the CIA would hurt America’s ability to carry such activities out.

That the CIA is perfectly willing to break the law, as a matter of policy, suggests that even if government officials did question the agency’s assumptions, it would not readily accede to piecemeal reform. In overstepping its original charter — moving beyond intelligence-gathering abroad to domestic spying, and actively attempting to influence the events it reports on — the CIA has proven that illegal acts are not only essential for its operations but vital to its existence. We need no investigations into what should be done about the CIA. It needs to be abolished altogether.

BY THE CRIMSON EDITORIAL BOARD

The announcement by the Kennedy Library Corp. this week that it will probably build the JFK archives and museum at the University of Massachusetts represents a collosal failure of

University now faces is the result of the timidity of its policies towards the library. Faculty members and community residents have for a long time opposed construction of the Kennedy museum in Cambridge but endorsed

the location of the archives here. President Bok, however, steadfastly refused to criticize (or for that matter say anything about) the desirability of the tourist-drawing museum, preferring instead to defer all criticism to the Kennedy Library Corp. If Bok had led a “surgical air strike” on the museum several years ago, before construction costs made splitting the museum from the archives financially impractical, he might have succeeded. By taking a stand, he could have fused the university’s interests (the archives) with the community’s interests (elimination of the museum). His silence helped bring about a solution no one really wanted. Even in the last few weeks before the announcement, Bok and his administrators counted on a plan that everybody connected with the museum viewed unfavorably: placing the archives in Cam-

bridge and taking over a portion of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., for a memorial museum. This plan never had a chance. Administrators at both the Kennedy Center and the library opposed it. To save the archives, the University would have had to come up with its own plan, possibly favoring a nearby Watertown site for the entire complex, or offering to subsidize construction of the archives here. But it instead rejected taking a dynamic role in the decision process and relied on the vain hope that Kennedy allegiances to Harvard would overcome the infeasibility of the plan they backed. If University officials can gather their wits about them, however, they may still be able to turn the impending Kennedy Library decision to their favor by negotiating with state and federal officials to buy

the entire 12.2-acre site. Such a move would at first provoke the strongest kind of local opposition. But if Harvard were to sit down with the diverse neighborhoods it might then work out a plan allowing the site to be developed with both Harvard’s and the community’s interests in mind. If Harvard must increase its housing and teaching facilities in the next few years, then this vacant land across from Eliot House represents a far more desirable alternative to its present plans for destroying private homes, paving over Agassiz school yards and tearing apart neighborhoods. The plan to buy the whole site, though, would require cooperation with the community and initiative on the part of the University, two qualities that Harvard has consistently lacked throughout the Kennedy’s Library controversy.

MEN’S SWIMMING

The Legacy of Harvard’s 1975

Men’s

UNBREAKABLE BOND. Harvard’s 1975 men’s swim team didn’t just dominate in the pool — they built a bond that’s still going strong, 50 years later.

BY ISABEL C. SMAIL CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

In 1975, the Harvard men’s swim team dominated its dual meet season with a 9-0 overall record. The team glided through the pool to success, thwarting fierce competitors including Navy, Princeton, and, of course, its historic rival Yale.

Now, fifty years after its incredible season, the team remains one of the most iconic in the program’s long history. Coached by Ray Essick, the small roster of swimmers brimmed with talent. In addition to Americans, the group included two Canadians, two Aussies, one South African, and Francisco Canales ’78 from Puerto Rico. Captained by Richard Baughman ’75 and David Brumwell ’75, the team was very inclusive, promoting a community in which foreign and American students alike could thrive. After meeting the 1973-74 team during its training trip to Puerto Rico, Canales, who had never visited Harvard’s campus, decided to join the ranks of the Crimson. Upon arriving in Cambridge, Canales had never spoken English full-time before, which made the already challenging transition to collegiate life difficult.

“They quickly welcomed me into the family,” Canales said, describing his teammates. “Road trips to other Ivies gave us bonding time, and over the years we consumed massive quantities of McDonald’s food on the bus rides home, led by Tom Wolf ’77.” Despite the sense of camaraderie that the team fostered, the group was intensely competitive.

“We had world-class swimmers every day in the pool, led by Hess Yntema ’76,” Canales said. “It was easy to be motivat-

Swim Team

ed.” Baughman, a Captain and distance freestyler on the team, credits the motivational aspect of the team to Don Gambril, who held the head coaching position before Ray Essick. Before attending Harvard, Baughman, like many of his teammates, was torn between the chance to swim for a more competitive program – like the University of Michigan or USC — or to attend a less athletically focused, but more academically rigorous institution like Harvard.

“As a 17-year-old whose life was largely swimming competitively year-round on AAU, high school, and club teams, I was concerned about the current Harvard program and whether or not I’d be throwing away my swimming career with a

choice to attend Harvard.

“Don was probably the best swim coach I’ve ever had,” Baughman added. “His lowkey but highly motivational approach worked very well for me.”

In April of 1973, Gambril shocked Baughman and the other Harvard swimmers by announcing his departure from the program. Ray Essick was then hired as the new head coach.

“When Ray Essick arrived, the tone of the program changed noticeably, and I was also beginning to burn out,” Baughman explained. “He was not the motivator that Don was.”

Under Essick’s tutelage, the program succeeded.

“We all always did very well,” shared Kevin O’Connell ’78, a

inated all season.

From the opening splash of the season, the Harvard swimmers had been unbeatable. Harvard tallied victories against all its formidable opponents, which spurred Coach Essick to give each of his athletes a T-shirt with a big red target printed on the front. Rather than a typical bullseye, these tees were adorned with a big red H in the middle. Before facing off against the Cornell Big Red, Essick shared that he felt as though everyone was aiming to beat Harvard. The shirts served as formal reminders, just in case any of the Harvard swimmers forgot that their success poised them as targets. Despite the rise in pressure, the Crimson continued its reign of dominance in the pool, easi-

Steve Baird tested Princeton’s star sprinter, and was able to successfully protect his team’s undefeated record.

Knowing that nobody on his team could defeat Princeton’s formidable Joe Loughran, Essick strove for a close second-place finish from freshman Canales to secure the 62-51 victory. Canales delivered for his team, earning second in both the 500 and the 1000-yard freestyle races. He “was up against the Princeton captain in the biggest meet of the year in front of the noisy Princeton crowd,” Essick said while describing Canales’ race in February 1975. “He just turned it on in the final 25 yards in a very, very exciting race.”

The success of Canales, who then raced for Puerto Rico in