T H E G R A P P L E R

1.

Camille Rose Pugliese and Liz Bazzoli

Opening Night

by Camille Rose PuglieseWe Don’t Need More Tributes

by Josephine ClarkePerformance at the PQ: Forms of Protest

by Joan StarkeyI'm Here II

by Camille Rose PuglieseDonald O'Connor Meets Postmodernism

by Kate ShuertInaccessibility is a Failure of Imagination

by Artemis WestoverReimagining the Director

by Josie MooreA Theatre of Abundance

by Liam ShannonSCENOGRAPHERS AT THE PQ!

CAMILLE ROSE PUGLIESE AND LIZ BAZZOLI

CAMILLE ROSE PUGLIESE AND LIZ BAZZOLI

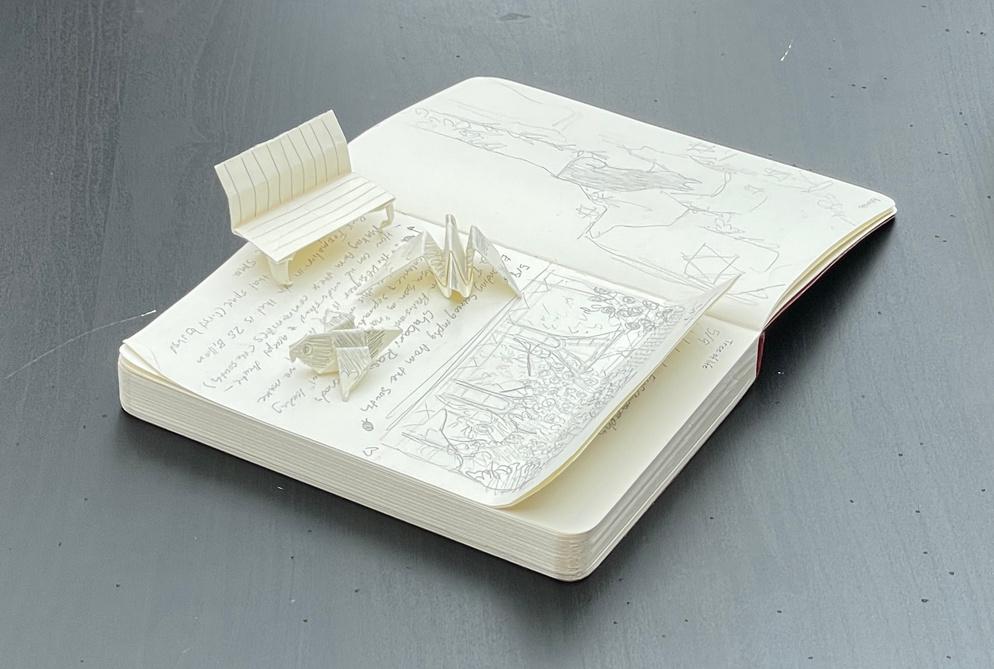

Late spring quarter, the two of us were approached by Kristin Idaszak, a member of The Theatre School’s dramaturgy faculty. It was at this moment we first learned about a brand new study-abroad trip to the Czech Republic More specifically, we learned that the trip would take students to the Prague Quadrennial, an international scenography and performance festival that’s taken place every four years since 1967. 2023's festival would be the first since the onset of COVID-19, and this triumphant return set out to celebrate artist’s adaptations to the post-pandemic world What better opportunity could there be for today’s theatre students, each of whom is coming of age in a professional environment still struggling to address the changes brought by COVID-19?

The trip, led by professors Kristin Idaszak and Shane Kelly, brought together 20 TTS students across departments, including our own editor Camille Pugliese From 8-18 June, these students explored the city and watched-- even sometimes participated in--a variety of performances from international artists of diverse artistic backgrounds and practices. From these experiences, students wrote a series of essays and reflections As a publication dedicated to the development of theatre writing, The Grappler happily features the hard work of thes d i hi i l ll di i Congra

My mind wandered to Konstantin Treplieff’s monologue in Anton Chekhov’s 1895 play, The Seagull during the opening ceremony of the Prague Quadrennial (PQ) The PQ is an international scenography and performance festival which occurs once every four years in the heart of the Czech Republic I joined the ranks of scenographers, theatre makers, and performers from all over the globe, witnessing cutting-edge innovations in theatre technology and performance The PQ is a chance for all its attendees to see what the future of performance design will look like

These boundary-breaking doers share the burden of Konstantin’s dreams The PQ is a realization of his passion: new forms! Konstantin seeks to create his own kind of theatre that speaks to him and his generation– a theatre that directly addresses the needs of the new and the now Everyone at the PQ is working towards their own “RARE futures”, the theme of this year ’ s PQ, to make theatre that is beyond imagination Though Chekhov’s character was ultimately unsuccessful, the legacy of his antidisciplinary spirit lives on If only Konstantin could see us now

The festival buzzed with this hope In the moments before the official opening ceremony, I watched old friends meeting, kissing, reconnecting for the first time in four years or more

These sweet small reunions reminded me how special it is to be together, to create art together after the tumultuous years of the global pandemic and so much time spent apart We huddled in anticipation to watch a performer in a glittering gold sequined dress and a cheap, choppy blonde wig kick off the beginning of the festivities which would continue for the next two weeks

In the first few moments they were silent, the only noise came from the sound of drums which played like the beginning of an ancient ceremony

They carried a gold PQ flag as if it were an olympic torch, and it was his sacred honor to light the flame They walked and the crowd blindly followed him through the market Bodies together, taking up space in a way that felt impossible this time three years ago.

Their journey ended at the center of the market, at an inflatable bull ring adorned in the same gold he wore They mounted the bull, standing, rotating to face the masses before them The performer grabbed this metaphorical bull of a changing theatre by its literal horns At the same time, they called us to make the art that we want to see, art that responds to the unprecedented times we face It felt like both a challenge and a promise A strange tension existed in this campy yet urgent and almost solemn performance We can’t move forward without remembering the past. We can’t be stuck in the past and forget about the future

I felt Konstantine’s words in our golden leader’s speech He gave us a call to action that would only be satisfied with more creativity. More newness. If we are the future, we must think more expansively about what theatre, performance, scenography, entertainment, and even liveness will look like one day. Scenographers, performers, writers, builders, directors, and of course dramaturgs, it is our responsibility to make a more sustainable and long lasting theatre

We will be the ones The ones who understand what it’s like to create theatre beyond the threshold of what feels possible The ones who make art because they understand its global impact and the capacity it has for change, The ones at the forefront of change We are the ones who make new forms possible

“IT FELT LIKE BOTH A CHALLENGE AND A PROMISE”CAMILLE ROSE PUGLIESE (SHE/HER) IS A BFA 4 DRAMATURGY & DRAMATIC CRITICISM MAJOR FROM RED BANK, NJ PHOTOS :JAKUB HRAB

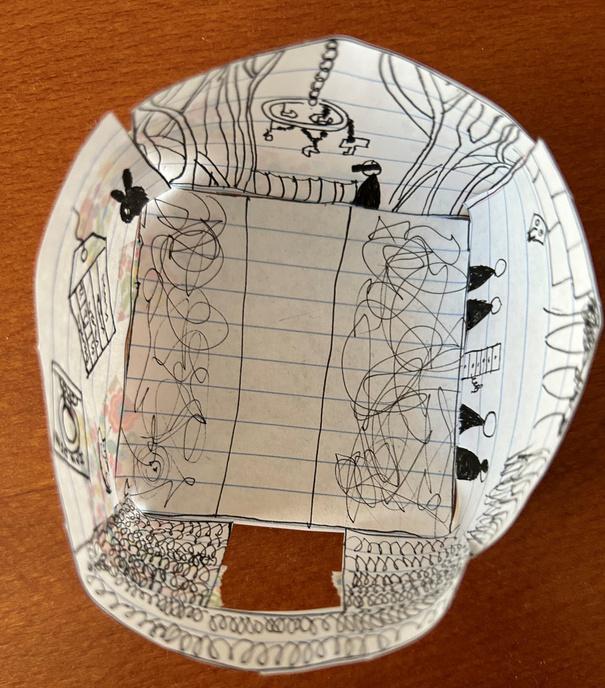

The exhibit hall at the 15th Prague Quadrennial (PQ) was unlike any exhibition I had ever been to Rather than still paintings or plaques on a wall, there were installations brimming with life. There was a fake travel agency, a booth to make flower petals for a wooden tree, a giant Styrofoam cube with performers “mining” in its caves. The PQ team called for “rare” experiences, calling for new forms and scenographic innovations, a call that was clearly answered. As I stumbled through the exhibition on the festival’s opening night, I found my peers standing in line, waiting for something.

They excitedly told me they were in line to die.

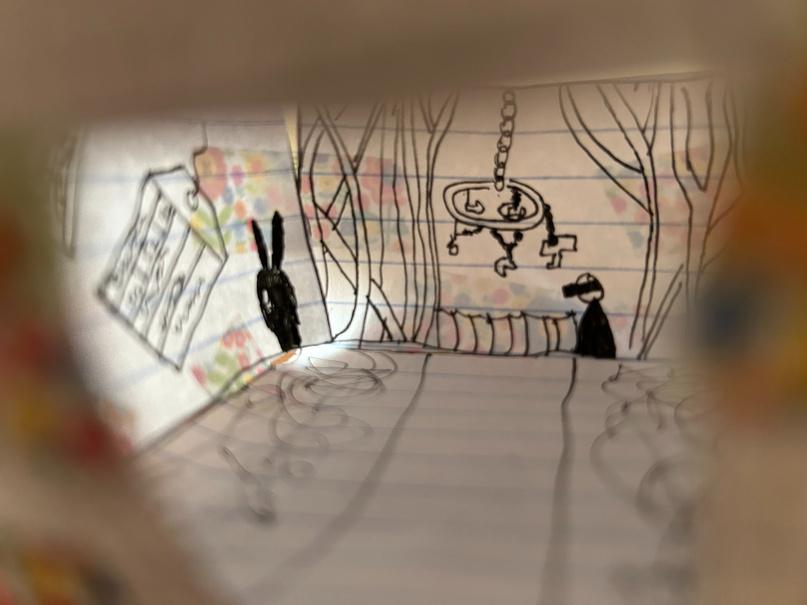

This was the Chilean exhibit, aptly titled Memento Mori: Animitas of Chilean Theater Design Four performers in officiallooking slacks, ties, and bunny masks manned an open-walled structure. As I looked inside, I could see the “death” I was waiting for Participants were instructed to step into the structure and put their head through a hole in the wall, with an arrow pointing to it that sported a glib caption of “You Died” A polaroid was taken, a tag was handed to the participant, they filled out the tag and it go stamped Quite a DMVesque process of dying

Animitas are roadside memorials in Chile that are designed to pay tribute to and house the soul of someone who has died suddenly

This particular animita was for 20 different designers that the company Complejo Conejo had decided to “kill” They state, “[w]e have killed the masters, and we preserve their spirits in these animitas that are paradoxically brimming with life, for it is a fact that stage designers do not rest in peace ” Indeed, an important aspect

The inspiration behind the piece came from the death of the Complejo Conejo’s mentors during the pandemic Indeed, it felt odd to be so celebratory in the face of death after such a major, deadly event as COVID However, it didn’t seem like Complejo Conejo was being disrespectful in their approach This animita was assembled out of care and deliberation a simultaneous acknowledgement that scenographers never truly die, but a facetious “killing of the masters” In an accompanying booklet, Complejo Conejo clarifies that their particular animita was not a true memorial, asserting “ we don't need more tributes”

“LETTING OLD “MASTERS” GO DIDN’T HAVE TO BE SCARY, AND INVITING NEW FORMS DIDN’T NECESSARILY MEAN THAT EVERYTHING WE ALREADY HAD WAS DEAD.”

However, it didn’t seem like Complejo Conejo was being disrespectful in their approach This animita was assembled out of care and deliberation a simultaneous acknowledgement that scenographers never truly die, but a facetious “killing of the masters” In an accompanying booklet, Complejo Conejo clarifies that their particular animita was not a true memorial, asserting “ we don't need more tributes”

It was not reverent; it was fun We giggled and laughed as we thought up ways to die that we would write on our tags When I was dying, there were some technical difficulties with the camera In an almost Monty Python-style repetition, the attendant kept saying “You are going to die,” only for the camera to not work I was strangely relaxed and almost reflective as I as led through the process Something so macabre and sad surely should have inspired feelings of reverence or somber ponderings, but I left feeling giddy and inspired Letting old “masters” go didn’t have to be scary, and inviting new forms didn’t necessarily mean that everything we already had was dead The revelation helped me to see the rest of the exhibitions through a new light

Memento Mori translates roughly to “Remember you will die,” which can serve as a grim reminder, or it can be a phrase that gives exigence to the present Killing the masters gives way to new, rare ways of artistically creating If we don’t get caught up in our own personal tributes, we can create new realities as well

JOSEPHINE CLARKE (SHE/HER) IS A RECENT GRADUATE OF THE DRAMATURGY & DRAMATIC CRITICISM PROGRAM, CURRENTLY RESIDING IN CHICAGO, IL.

PHOTO :JAKUB HRAB

PHOTO :JAKUB HRAB

MEMENTO MORI ANIMITAS OF CHILEAN THEATRE DESIGN

MEMENTO MORI: ANIMITAS OF CHILEAN THEATRE DESIGN

PHOTO :JAKUB HRAB

PHOTO :JAKUB HRAB

MEMENTO MORI ANIMITAS OF CHILEAN THEATRE DESIGN

MEMENTO MORI: ANIMITAS OF CHILEAN THEATRE DESIGN

BY JOAN STARKEY

BY JOAN STARKEY

After an opening ceremony that bewildered and riveted me, there were two shows at the Prague Quadrennial (PQ) that particularly affected me. Be Water, My Friend, an interactive and ambulatory experience protested explicitly against oppressive systems of government, and I’m Here II, a dance piece, subtly resisted the equally atrocious forces of ageism and misogyny Not only did the story of these pieces inspire but their distinct and purposeful dramaturgy supported them profoundly

Be Water, My Friend is a participatory performance art piece made by Hong Kong artists Carmen Lee and Chun Shing Au of Theatre du Poulet in Canada in collaboration with German artists Greta Katharina Klein and Levin Eichert It has had many iterations, but at the PQ it began on the Střelecký island on the Vltava River surrounded by sunlight and greenery

The artists instructed us to keep water droplets balanced on our hands and then contribute them to a waterfall Together, the audience manipulated a large tarp holding a small pool of water from the river, observing the interesting movements and shapes we could make We broke off to individual resting spots on the island and learned via the Telegram messaging app about water as a metaphor for protest strategies used in Hong Kong in 2019-20 We carried water on plastic wrap in small groups and traveled with it through the city to the courtyard of the Národní Divadlo (National Theatre) of Prague, where we pooled our water for the artists to use for writing protest slogans on the concrete walls and ground with mops, sprayers, and sponges

Their messages included: If the world could see, what would you write? Who will protect us? Can you run fast enough? Write fast enough? Do you know first aid and selfdefense? Be water to fight Be water to live

Even though we were in a busy public area of Prague, there was little interruption of the performance, until this moment Not long after the artists began this closing portion of the piece, a semi-official looking man (we later discovered he was from the National Theatre and not a part of Be Water) began spraying over their words with a hose It was shocking and unsettling to see their art interrupted To see a realtime example of the authoritative oppression discussed in this piece unfold in front of me, especially in direct response to a work of art, was disheartening

The ambulatory and participatory form of the piece activated its audience in the consideration of this message Its interactive physicality mirrored a protest; we received information and instructions in small pieces over text, gathered and marched through the city, and read and wrote powerful slogans Kinesthetically feeling physical elements of protest during the piece made me connect to it and consider my experience at protests and protesters in Hong Kong and historically in Prague The participation in writing messages in water activated me to think about their application to my life I know I will remember the water metaphors I learned over Telegram, to be “strong like ice and fluid like water,” to “gather like dew and scatter like mist”

The form of this piece allowed it to teach its audience about a current social issue and apply water teachings to real-life protest strategies Exercising those strategies, for example scattering like mist into the city and gathering like dew to write messages, was built into the structure of the performance In investigating their focal material of water literally, then metaphorically, then actively, these artists crafted an effective structure for this interactive performance

I interpret I’m Here II as a protest piece too, though it addresses oppression artfully through abstract body politics The dance performance by Israeli choreographer Galit Liss featured an ensemble of 65-plus yearold women from Israel and the Czech Republic They began standing on the second-floor balcony of the National Gallery of Prague looking down intently at the audience Their presence was stunning, all gazing with their own strong expressions

They entered the ground floor playing space where they first walked, then ran, then danced unrestrained up and down the performance space in a staggered pattern that allowed my eye to wander from performer to performer The women stopped whenever they reached the very front of the playing space and gazed out solemnly The stillness was striking In a poignant moment, they stood in a line at the front of the space, a mere foot away from me as an audience member, and each touched a part of their body that held a memory The gesture was at once secretive and revealing

AT THE SAME TIME THE IRONY WAS CLEAR TO ME, AND THIS UNEXPECTED DRAMATURGY SUPPORTED THE PIECE. THIS MAN UNINTENTIONALLY REINFORCED THE MESSAGE OF THE POWER OF WATER, PROTEST, WORDS, AND ART AGAINST OPPRESSION

The only spoken words were “What do you see? What do you not see? Look at your hands; is there a memory?”

In the United States, elderly people especially women are hidden away from public eye because the world is not built to accommodate them Because of ageism and misogyny, they are told their bodies are unacceptable and should not be viewed at all Through the freedom of dance, these women boldly proved that notion wrong Rarely do we get to see elderly women encouraged to express this much joy and artistry.

I’m Here II also had a participatory element At one point, the performers entered the audience space and did handmirroring with several audience members The gesture made me think about aging, the connection between the old and the young, beauty standards, and what I will look and feel like when I am their age I feel like I gained wisdom about fearlessness from seeing them sing and dance to their own individual music Spirit never dies, and movement to music is a profound way to express that

Activation These concepts are swirling around my head having experienced these performances at the PQ festival. Through navigating these ideas like I navigated the city of Prague carrying water and absorbing new forms of dramaturgy like the touch of a stranger during a dance I mentally resituated myself in the world

While it is my job to continuously question whether theatre can change the world, these performances reinforced my belief that theatre can change people At least I have come out changed

JOAN STARKEY (THEY/SHE) IS A BFA3 DRAMATURGY AND CRITICISM MAJOR FROM ORLANDO, FLORIDAMy grandma Mary told me this countless times Most times she laughed, but there were many times she wouldn’t Times she’d look at me and I knew she was genuinely telling me not to age at all I felt a warning against the inevitable

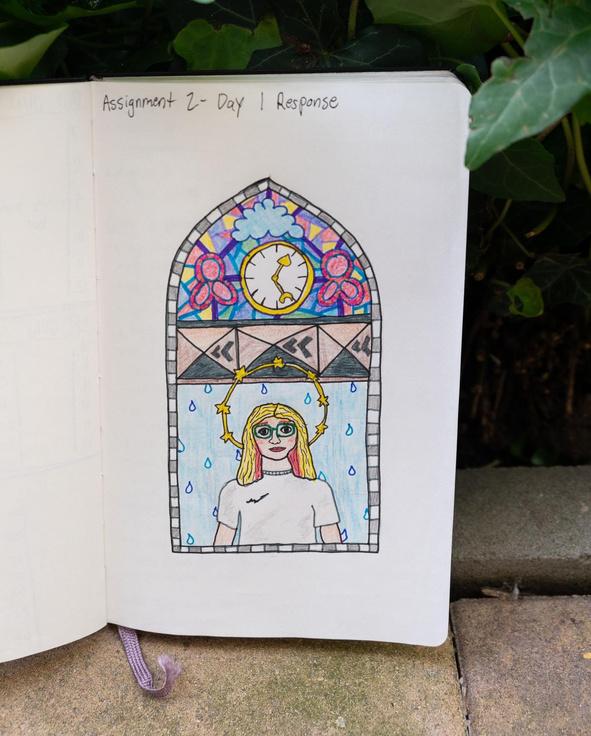

I’ve been thinking about Mary a lot recently, her humor, and her warning This may be why I was so struck by I’m Here II, a dance performance created by Israeli choreographer Galit Liss at this year ’ s Prague Quadrennial It featured mature women from both Israel and the Czech Republic in a movement piece that connected body, heart, and soul

I knew this performance would be special from its opening moments It took place in a large, open, yet sterile and white gallery space The room felt sterile despite its brightness and openness to the rest of the gallery The women brought warmth to this cold place They stood on an upper balcony looking down on the audience, smiling strongly together as classical music played Each wore a brightly colored t-shirt as if to say:

I will not be hidden, you will see me

One by one, they descended the stairs to meet the audience Once they reached the ground floor, they began individual journeys of running up to the audience, stopping, looking into the crowd, and returning to the back of the performance space to do it all over again The running slowly morphed into dancing, following the same pattern of approaching, looking, and returning It was movement that looked like it felt good I felt their joy move throughout my own body as I watched

There was so much I admired in this short performance, which would only last twenty minutes I was struck by their awareness of the audience– the courage it takes to look out into the audience as if to say “I’m here” I asked myself why I was feeling this way, why I couldn’t treat this performance like anything I’d seen at the PQ so far?

It’s because of the way we treat mature and elderly women in the United States The way we ’ re meant to fear aging, fear what our bodies may look like in 10, 20, 50, 60 years Somehow, our society has made us complicit in a system where women lose value when we don’t fight against the natural passing of time Older women go literally unseen, are too often stripped of their identity and pushed to the margins

A voice over called them to look at their hands: “What do you see? What do you not see?”

They came into the audience, connecting with us, having us follow their hands with our hands: a parallel image of young and old A woman with short dark hair, kind eyes, and a warm smile came up to me

I followed her hands, and we existed together in a moment of shared time

I thought about Mary, and all the women before her, and all women after me

I’m not afraid to get old CAMILLE ROSE PUGLIESE

More than it is hard to be a person, it is hard to make a mistake In a time of supposed better access to communication, rather than use social media and other platforms to show the ways people connect, there is an aspect of competition to show the most perfectly curated version of oneself Even as I write this piece, I think and rethink my sentence structure- I write and delete sentences, wishing to have the right words the first go around instead of the second, third, fourth edit.

Yet, in the performance of How Things Go at the 2023 Prague Quadrennial (PQ), that is exactly what the two acrobats performed at the National Gallery of Prague At the PQ, theatre artists gather from around the world to showcase avant garde performance and scenography How Things Go by Felix Baumann of Denmark and Sean Henderson of the United States, reminded its audience that life is about this continued struggle of losing, over and over again In this 40-minute silent piece, “two guys [tried] to build something remarkable for their lives Along the way, their encounters with objects set off a chain of reactions in which failure is embodied in the architecture of the room ” (pqcz)

Positioned at the front of the audience, I felt the stress and angst around me when the piece began and two wooden planks fell from their upright, shield-like position The wind danced on my arms from their immediate collapse

I laughed, yet no one else seemed to share my intrigue or delight Perhaps they feared the falling--what does it mean to the audience if the performance has failed, but that its failure is a success?

It is difficult, I noted, to accept that failure may be okay, let alone intentional Words fail me as I attempt to describe this feelinga feeling no god, animal, or machine has experienced Is this piece successful because I am questioning my own struggle? I can barely accept the emotion as I’m writing about it-because it is a strictly human experience to resist failure in this way

As How Things Go continued, the large wooden planks partnered with four beams The performers built structures to simulate climbing up hills and waltzing through mazes, the figurative twists and turns of life The audience sat in shock at what they were able to do with minimal sound design and raw material

HOW THINGS GO PHOTO: ANNA BENHACOVAThey were beautiful in their attempts to rise above each setback, they were determined despite the feedback loop seeming unending

By elevating their mistakes into art, Baumann and Henderson ask the audience, why are failures hidden? Why is it embarrassing to do what is inherently human? Many of us subscribe to the idea that when someone makes a mistake, something is gravely wrong It is what is most feared despite the elevated ways to connect and communicate today

The show ended with a cacophony of sounds as the two men walked the plank and threw themselves off the edge of a contraption the duo termed the ‘Suicide Machine’ Even the act of dying, the two couldn’t quite complete Despite its pessimistic close, the performers were met with raucous applause from the audience, having achieved a resonant connection with their audience

I know I am not immune to the illustrious calling of perfection I have written thousands of words but only 674 have made it to this piece Yet, my experience as an audience member of How Things Go elicits a calm feeling that I hope to pass on to those reading It whispers to me as my writing comes to a close, that the other 1,000 words I cut were intentional and meaningful

That it is perfect and right to fail

Because friends, that's just how things go

ROWEN NOWLAN (SHE/HER) FROM PLYMOUTH MEETING, PENNSYLVANIA IS A BFA 4 THEATRE ARTS MAJOR WITH MINORS IN EVENT PLANNING AND PHILOSOPHY.

Two men with wooden boards and posts in a barren museum lobby transported me to Hollywood’s Golden Age sound stage Really, I was sitting on the tile floor in the lobby of the Trade Fair Palace at the 2023 Prague Quadrennial A macabre counterpart of Donald O’Connor’s performance of “Make ‘Em Laugh” (Singin’ in the Rain, 1952),

How Things Go by Felix Baumann and Sean Henderson, while certainly humorous, reckons with the doomed cycle of human failure The two men attempt to make something, anything, of the materials at their disposal And time and time again, their structures fail or are dismantled or destroyed and the stage returns to its nearly empty state Their structures served as the vehicles for the performers’ demise more often than not

I first thought this piece reflected the illfated efforts of human industrialization, but there’s a more fundamental message In a conversation with Baumann, he distilled the performance’s ultimate message: “There is no learning for them”

The two men may, in their 40-minute exploration of construction and deconstruction, make some progress Certain structures hold together longer than others, but it does not change their inevitable failure

Take for example one of their final structures, a crude ramp The two men alternated jumping off the back and being spat out either side Baumann called this “The Suicide Machine” Oddly the arguably most successful structure is that which “kills'' the characters the most times They do not learn; they only re-emerge to run up the platform to nowhere time after time, birth after birth, confidently jumping into the abyss Using the ramp–one of the earliest feats of engineering–is no accident in this case Technological advancement does not always serve us and, in many cases as it does here, accomplishes just the opposite They build without purpose and use without thought

Yet, it’s all done with the light air of clowning and slapstick comedy To a score of mechanical banging and drilling, Baumann and Henderson fumble with their boards, trip over their work and each other, and knock their counterpart upside the head or to the ground

They disappear and emerge from walls confused and lost The audience laughs at the absurdity of their actions and the repetition of their futile endeavors

Donald O’Connor isn’t even listed as reference or inspiration, the artists instead list that their piece is informed by the work of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd Yet it was O’Connor’s performance of “Make ‘Em Laugh” in Singin’ in the Rain that immediately came to mind

The presence of physical comedy is certainly the most obvious of similarities between the two The two performances strike a similar chord as they comment on the nature of comedy while being in the midst of creating it They both possess the ability to make light of the humorous potential of pain and failure, an association which is so grim. Donald O’Connor sings the words “Take a fall/ But a wall/ Split a seam/ Make ‘Em Laugh” In both cases, the audience is meant to laugh at the suffering of the performer Each bonk to the head, every trip and stumble, any harmful mishap is served to the audience as a morsel of delight What is it about this kind of process, this cycle of misguided or unguided effort, leading to failure that makes us laugh?

“FACE TO FACE WITH AN EXAGGERATED PORTRAIT OF THE HUMAN COMPULSION TO CREATE, THE INHERENT STUBBORNNESS OF THE ARTIST, AND THE PRIMAL INSTINCT TO KEEP TRYING OVER AND OVER AGAIN TO LIVE ANOTHER DAY...”HOW THINGS GO PHOTO: ANNA BENHACOVA

Perhaps it is the concentrated form of human spirit that makes this piece so hilarious and so tragic Face to face with an exaggerated portrait of the human compulsion to create, the inherent stubbornness of the artist, and the primal instinct to keep trying over and over and over to live another day, I can’t help but laugh at the two bumbling men and myself reflected in them It mattered not what the men made or how long it lasted or what purpose it served Rather, this piece calls into question the human attitude toward generation It mattered how they made itstubborn and uncompromising These just might be humanity's most laughable qualities, maybe we don’t care what we do as long we do something. Century after century we make things that do us no good at all and, ridiculously, we keep doing it

KATHERINE SHUERT (SHE/HER) IS A BFA2 DRAMATURGY AND DRAMATIC CRITICISM MAJOR FROM LOMBARD, ILLINOIS.

HOW THINGS GO PHOTOS: ANNA BENHACOVA

HOW THINGS GO PHOTOS: ANNA BENHACOVA

Every four years, theatre makers from all over the globe gather somewhere in the capital city of the Czech Republic to spend two weeks sharing their work and ideas on scenography and performance design at the Prague Quadrennial (PQ) This year I attended the 15th edition of this festival It was a life-changing opportunity to see the art being made at the cutting edge of theatre The newest and rarest forms (RARE was the theme of this year's festival) In their definition of scenography, the PQ centers audience experience and participation as a central component of this art form In the individual theatrical performances I saw special attention being paid to the way the audience experienced the theatre But my experience of the PQ itself, as an organized festival, was fundamentally different

To put it plainly, the Prague Quadrennial has an accessibility problem On their website, there is a page dedicated to Practical [Information] for Visitors With Disabilities/Reduced Mobility where they claim “All people, regardless of their disabilities, should be given the opportunity to explore the world of art and culture We recognize that accessibility to cultural institutions is key as this is the area that connects people the most” I do not doubt the fact that this is a true belief held by some of the people in this institution Instead, I want to look deeper into the materiality of the accessibility of the PQ and try to determine if this belief ever made it into practical implementation

This piece focuses on my own observations and experiences It is not a comprehensive accessibility audit, nor does it cover the majority of my thoughts and feelings around accessibility as a broader concept My goal here is to focus on just the experience of being at the PQ itself and to provide my own observations, analysis, and offerings for this issue

The Space:

This year the quadrennial’s primary site was the Holesovice Market Formerly a slaughterhouse, processing, packing, and butchers market, Holesovice is a complex of one or two-story warehouses connected by its own network of cobblestone streets and open squares Cobblestones are ubiquitous in Europe but they are not an insurmountable obstacle. There were no ramps or built walkways anywhere around Holesovice The PQ constructed bars, outdoor stages, and other booths to prepare for the festival There is no question that the resources existed to provide this very simple accessible option The PQ website says this about the exhibitions themselves “All exhibition spaces are barrier-free, entrances to the premises and entrance doors are wide enough for wheelchairs” This phrase, “barrier-free” is said several times on this page I can only assume they mean that there are no literal roadblocks to access such as stairs or railings

I assume this because the physical layout of the buildings were not accessible, despite being technically barrier-free None of the doors had buttons to open them None of the bathrooms had wheelchair stalls or grab bars, and all of them were small and difficult for me to navigate with just my cane and a large backpack

People with limited mobility are not the only people who would have found the Holesovice market very difficult to navigate There was no non-smoking outdoor space There was no alcohol-free space There was very little built shade There were no sensory-friendly or quiet spaces The lack of these accessible spaces not only affects the experience of those who might identify as “disabled”, but they also affect anyone's ability to enjoy the space at the PQ Comfortable and safe spaces benefit everyone and increase everyone ’ s ability to fully engage in the programs that the PQ has to offer

Now it is important I acknowledge that several things I am pointing out can be attributed to cultural norms, whether Czech, European, or otherwise Especially drinking and smoking The point of the PQ is to explore new forms We embrace things that challenge what we think we know theatre to be So why can we not extend this outlook to accessibility? Could there have been a conversation where new forms of socializing were imagined? The same can be said of cobblestones, uneven ground, and the challenges that historical buildings present Yes, these things are ubiquitous and accepted But why must they be accepted without challenge or contradiction? In a festival so dedicated to rethinking spaces, why does the imagination stop at our present setting?

The Program: I will not focus on the content of the exhibitions or performances themselves I am assuming that any accessibility issues there are the responsibility of the performers/artists and not within PQ admin control

However, the way performances, talks, and exhibitions were presented was within the festival’s control There were no content warnings of any kind Here I do not just mean warnings about the potential psychological stressors within a piece, but physical warnings as well such as haze, strobe, loud/abrupt noise, or other sensory components that can impact physical safety. I recognize content and trigger warnings are complicated and fraught, and I am disappointed that they were not included in any performance or exhibition, but strobe and haze warnings are common in my experience in the United States I was very surprised to not see them anywhere There was also a lack of translators or interpreters The festival's official languages were English and Czech, but there was no sign language, closed captioning, or braille

The final panel I attended was a Behindthe-Scenes look at the organization and planning of the PQ All of the main organizers attended as well as several curators Many of the things I have mentioned were brought up in the audience's questions and the responses varied

“DESPITE ITS EFFORTS TO UPLIFT THEATRE THAT INNOVATES AND EXPERIMENTS WITH NEW FORMS, THE ORGANIZATION OF THE PQ WORKS TO REINFORCE GLOBAL STRUCTURES AND HEGEMONIC NORMS.”

The lack of translators was brushed off as a budget issue, a question about content warnings was addressed by asking the audience member to name specific issues with specific shows, and when I asked about the considerations made to the accessibility of the chosen venue, Marketa Fantova, the Artistic Director responded that, when taking budgetary, political, and logistical challenges into consideration, that accessibility at the PQ was “just impossible”

Barbora Prihodova, the curator of PQ talks explained that the subjects and speakers were not decided by her as curator, but rather they were part of the pitches for talks. She also said that visa issues and global politics had a large impact on who was able to attend the festival It is good to know that the coordinators of the festival were aware of these issues and yet it seems like there was no action taken on the PQ’s part to mitigate the impact of these larger issues

The PQ is about innovation and pushing the imagination, but there seems to be no effort to imagine new ways to include, welcome, or represent artists or attendees The organizers’ response, the statement on the website, and many of the other things I witnessed reminded me that there are very different conversations happening at the PQ than those that are happening in the United States In the US we have things like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) because of the tireless work of many generations of activists I am only used to ramps, accessible toilets, subtitles, and strobe warnings because people before me fought to make those the norm

I came to the PQ with those expectations because they form the cultural context through which I see accessibility I truly believe it is possible that the people in charge of writing the website statement thought that they were doing enough That is again not an excuse, just an explanation

The problem of inaccessibility at the PQ is not one of budget or information, it is a problem of imagination or lack thereof At the PQ’s level, this kind of exclusion is inexcusable Despite its efforts to uplift theatre that innovates and experiments with new forms, the organization of the PQ works to reinforce global power structures and hegemonic norms They will not be able to truly push the boundaries of theatre and scenography if they continue to exclude those who bring the most to the table

A thought that I felt underlying the responses from the PQ team was the idea that they cannot possibly include everybody It is true that true global accessibility and inclusion is hard, not impossible, but hard But who is being left out has to be acknowledged and understood by the creators as a choice, not something that is completely out of their control There was a choice not to hire translators and interpreters, there was a choice not to build accessible bathrooms, and there was a choice to not acknowledge the ways that people were being left out of the conversation. Now I cannot speak to why or how these choices were made or even if they were being made consciously, but I can see the results, and I am disappointed with them

The PQ only happens every four years The team in charge of planning PQ2027 has ample time to reimagine the festival to be more accessible and inclusive, but if they are going to succeed they must use their imaginations, or hire people who will

My observations have shown me that the ethos of innovation and breaking the norms that define the presentation of the festival does not extend to the behind-thescenes work that goes into planning it The PQ needs to put its money where its mouth is, take accountability, and show up for the artists that they claim to lift up, and accessibility is the first step. I do not know how planning a global theatre festival works, I do not know every consideration that must be made to put the PQ together, that aside, I have one recommendation to begin approaching this problem: Hire one person (at least) and make accessibility their job

Creating a position whose sole focus is on accessibility will:

A) show the PQ’s commitment to increasing the accessibility of the festival

B) provide accountability and an opportunity for collaboration with every other department

In order to prevent these considerations from slipping through the cracks, the PQ must make its audience a priority and it starts with making a more accessible experience for everyone

Perhaps it is because I am a dramaturg before I am anything else, but to me what seems to be missing is questioning The Prague Quadrennial is an event that has inspired me to always question what I think the boundaries of theatre can be, and question myself as an artist, because of the time I have spent at this festival I will constantly be thinking about new ways to approach my work

I only wish that the organizers of the Quadrennial will find that same inspiration to always question what they know accessibility and inclusion to be and approach their audience with the same imagination that they ask of us

ARTEMIS WESTOVER (THEY, THEM IS A BFA4 DRAMATURGY & DRAMATIC CRITICISM MAJOR.

As students, faculty, and staff of The Theatre School, we have a solid understanding of the role of a director within theatre as we know it now They come in with an artistic vision, they assemble the teams (or work with the teams assigned to them), they lead the rehearsals, they bring a show from the paper to the stage

This is a hierarchical dynamic, with the director sitting at the top In my roles as an assistant director and a dramaturg alike I have been told to siphon my notes through the director I sit quietly, take my notes, and ask questions when the time is right, and always have my eyes toward the director I participate and enforce this hierarchy without my full awareness I am complicit Even in rehearsal rooms that have healthy working relationships between director, cast, and creative team, is this hierarchy something I am interested in replicating? Is it possible for me to be committed to nonhierarchical forms of community-building and collaboration while also training to be the person that holds the power in a rehearsal room?

At this year ’ s Prague Quadrennial, I encountered theatrical theory and practice across the globe through performance (PQ Studio and PQ Performance), scenographic installation (Performance Space Exhibition and the Exhibition of Countries and Regions), and lectures (PQ Talks)

In one PQ Talk titled “Methods of Collaboration: Performers and Scenographers”, six theatre practitioners across disciplines and continents discussed the different ways they view collaboration between performance and design in their respective fields This talk included interactive costume design that performers played with; using paper letters as scenographic building blocks that actors improvised with; and a festival celebrating Maori and other Indigenous communities in New Zealand as they traveled by canoe to the harbor

The panel opened with the question: what legacies, hierarchies, and assumptions have we inherited? These presenters displayed how they pushed against traditional models of performance-making that restrict collaboration They showcased how they break down barriers between performer and design While I greatly enjoyed each deep dive into a different method of performer-scenographer collaboration, I also felt overwhelmed I wanted this talk to inform how I can be a better collaborator in the role of a director, and yet I left feeling like the director was unrecognizable in each example In my tiny notebook I scribbled a question for myself

I could be making a generalization here, but I don’t think people like to ponder the point of their once-dream career a whole lot I am filled with less existential dread than I once was, but I still struggle with the uneasiness this question raises. I cannot deny the work that needs to be done if I want the role of a director to continue to exist in any capacity, but I only find myself with more questions to sit with.

Are all hierarchies bad, or just the ones we don’t interrogate? What is the outcome of director-less work, and how different is that from what we have now? What is the function of the director right now, besides holding the power and vision? At the PQ, I experienced forms of collaboration and direction that challenge hierarchical legacies that have been passed down through time Of course a festival celebrating new and RARE (this year ’ s theme) forms of performance and scenography should also showcase new and RARE forms of collaboration and creation With this in mind, these questions I ask that interrogate the role of a director invoke excitement and curiosity, not dread and dismay.

In the 11 days of the festival, I saw solo performers who wrote and directed themselves with some collaborative support; dynamic duos who worked sideby-side; and directing/devising teams that worked as a cohesive unit And, even still, there were still performances created in a more traditional sense, with one director leading a team of artists

In Be Water, My Friend, Carmen Lee of Hong Kong originally came up with the idea of a performance piece discussing protests in Hong Kong using water as a metaphor She worked with her close creative partner, Roland Chun Shing Au, to further bring this piece to life While Lee and Shing were confident in their teamwork and collaboration, they brought in collaborators who don’t share the same personal connection to the Hong Kong protests that Lee and Au do They brought on Greta Katherina Klein and Levin Eichert to help facilitate the performance and add their own cultural contextualization All four are co-directors and the piece’s performers

Do you know a place that doesn’t exist anymore?, an interactive performance about memory and the impermanence of place was devised by a team of four artists from Lebanon: En-Ping Yu, Kirstine Hupfeldt Nielsen, Mara Ingea, Susana Botero Santos Ingea is credited as the sole director

During Do you know a place, audience members were asked to draw a place that no longer exists anymore and drop the drawing into a box As one performer sat at the drafting table, continuously updating a floorplan of the performance space as it shifted and changed, the other three performers bustled around in orange harnesses, pulling various props and furniture from the storage room in order to bring these drawings to life Each of the three “angel architects”, as the performers were called, worked directly with the audience to help bring these spaces to life

Slowly, audience members turn into angel architects, with power being bestowed as they each slip on an orange reflective vest Ingea walked up to me and asked if I could help build something with her and together we built a mountain overlooking a river under the stars Ingea and the other angel architects brought me into the performance and gave the audience authority to build our own worlds Together, we reconstructed the places that had been stripped from us, until it was time to break them down once again.

BE WATER, MY FRIEND PHOTO: MICHAL HANCOVSKYA Galit Liss took a more traditional position as the lead director/choreographer on I’ m Here II, but this performance still pushed against a traditional directorial hierarchy

I’m Here II was a movement piece featuring mature women exploring their joy and how they’re perceived by the world These performers do not identify themselves as dancers In fact, on Liss’s website, she states her devotion to working with “older women who are non-dancers” Even with Liss as the lead director, this performance felt very personal and individual to each of the women They each danced down the stage in ways that looked and felt natural to the performer At one point, each woman touched a part of their body that holds a memory: some touch their womb, some touch their chest, one woman touched just her neck This dynamic resembled a community-driven performance process that is frequently seen in Chicago, and is what I am the most familiar with from my educational background and production history

Perhaps the question I scribbled down first arose because I was confronted with so many forms of art-making that I am unfamiliar with Perhaps the traditional hierarchy within academic institutions has been a comfort, a crutch that I have leaned on in my complacency Through the Prague Quadrennial I witnessed so many new forms of art and performance that completely shatters the theatrical conventions that I am used to. Even with my background in performance studies and my experience with devising, I still feel like I am seeing the director disappear But when we look at everything that surrounds us, all of the matter in the universe down to the smallest atom, we can see that nothing disappears: it just changes forms

We are moving from a top-down, omniscient model towards facilitators, collaborators, performers AND scenographers at the same time. We are blurring the divides between creative teams, scenography, and performers We work in teams, not just alone–even if we are the sole “director” Perhaps this is why being multi-disciplined is so important to my artistic identity. Perhaps this is why I smiled every time someone on this trip to the PQ didn’t know I was an aspiring director. I hope I always stay like this, shifting forms with the art I dream of working on

JOSIE MOORE (THEY/THEM) IS A BFA4 THEATRE ARTS-DIRECTING MAJOR WITH A MINOR IN PERFORMANCE STUDIES FROM THE ST. LOUIS AREA OF MISSOURIDO YOU KNOW A PLACE THAT DOESN T EXIST ANYMORE? PHOTO: JAN HROMADKO

In the opening ceremony of the Prague Quadrennial, an international theatre festival focused on scenography and performance, a performer in a gold sequined dress and white bob wig riding a mechanical bull repeatedly orated into a megaphone “ we need new forms” while falling off and climbing back on the bull

Over the next ten days I would see 20 performances, attend nine talks, and visit over 50 exhibitions and installations Only one would be a traditional play with a plot, characters, and story structure

New processes and theories around making theatre were platformed at the PQ Talks lecture series For example, ecoscenography, a term coined by Australian scholar and scenographer Tanja Beer Ecoscenography takes an ecological lens during the production process to create theatre that is environmentally sustainable Sustainability is used as a holistic and generative framework instead of a limitation A core tenet of ecoscenography is the three C's: Collaboration, Celebration, and Circulation

In Western theatre practices these would translate to pre-production, performance, and post-production, however, Beer’s Cs offer a new perspective on the artistic process that is circular No single step is more important than the other, when beginning step one the creative team should be designing with circulation in mind In Beer’s model, a performance is not a final product that then leaves behind waste, it is a step in a cyclical process that gives back to the environment rather than taking from it

Beer’s most powerful statement, “Waste is a failure of the imagination” is a strong guiding principle for beginning to digest the complexities of ecoscenography

The PQ Performance and Studio series showcased many pieces with zero actors, and the rest complicated what an actor is and does The most memorable and innovative works I saw were ones that inspired audience performances driven by audio and visual cues The Crowd by Norwegian company Teater Leikhus was the theatre’s version of a “silent disco” The audience wore headphones and walked around the theatre, which had no seating, viewing two sets saturated with props and containing no actors The headphones played music and monologues by people delivering personal stories About five minutes in, the voice in our ears asked “Who will stand on the sidelines and watch, waiting for someone brave enough to be the first to act?”

I was the first

I stepped forward, breaking the barrier of light that marked the border of one of the sets, and removed a Jenga piece from a Jenga tower within, placing it on top My choice inspired an explosion of interaction as the rest of the crowd embraced this new freedom to touch the sets and props

Someone nearby rode a scooter that was leaning on a chair Another took and wore a yellow leather jacket hanging from the ceiling We were meant to touch and play with this space

It was a playground for the audience to explore their relationship to how they exist in a crowd and how they interact with performance spaces People like me, who would kill a man to be an audience volunteer, played in the room like a child in a sandbox Others stood in the darkness of the edges and watched I had a picnic with strangers and drove an RC race car through a pyramid of paper cups someone else had built We all held a birthday party for someone who wasn’t there

This event was form-breaking, adventurous, and innovative The lack of actors left the “performance” of the piece entirely in the hands of the audience We were free to create our own experience, to play or observe in a way that is right for us The piece reveals to themselves and possibly to observant others each individual's relationship to performance and their comfort in social spaces Reflecting on my time in The Crowd, I am reminded that I am active and participatory in social spaces and that I constantly seek to perform for both myself and others I cannot speak with certainty for the internal experience of others, but I imagine that other audience members walked away from this experience knowing more about themselves and how they relate to the people and spaces that surround them

I came to the festival searching for new forms and processes, and with these groundbreaking pieces and talks I have more than enough inspiration to grapple with Yet, as stories go, I found something I wasn’t expecting at the festival I was shocked by how much I loved The Story of Larry, an object theatre performance with a linear narrative and traditional conventions

InThe Story of Larry by Moritz Praxmarer from Switzerland, the soaring dreams of Larry Walters, a man who built a flying machine out of lawn chairs and weather balloons, are retold using only a box of tea bags

Moritz uses a pocket knife to cut a tea bag into five sections, twisting four of them into arms and legs and the last being crumpled into a head-like shape to become Larry Walters This piece, which was not strange, reminded me of the power of the ordinary to tell stories filled with imagination, wonder, and splendor I left the tiny black box theatre with a renewed love for the familiar and the comfortable of theatrical styles, something that I thought I would be moving away from, maybe even abandoning at this festival. I am happy to have been shown otherwise

The festival brought a variety of forms from over 100 countries to Prague It showcased forms of performance I have never even dreamed of as well as traditional forms that were exceptionally well done Through my love of the innovative and experimental, and my reminded love for the traditional, I have discovered that I am pursuing the value of abundance

A theatre artist should constantly seek new forms to verse themselves in without abandoning the skills they have already created Stylistic variety triumphs over stylistic specialization and produces a higher quality and diversity of work

There is value in stylistic diversity for both the artists and the audience. Much like how learning another language strengthens your brain, learning many artistic styles expands an artist’s ability to create, to imagine, and to express.

Modern US audiences, who are ruled by the power of Broadway and the influence of American psychological realism would benefit greatly from being given something other than the meat and potatoes they know and love. In other countries, audiences are exposed to more challenging material and the arts receive greater financial support allowing for greater artistic risks Their artists are across the board more inclined to non-traditional forms The audiences and artists in the US need to be cultivated to the same standards. Through an abundance of artistic ability and style, as well as an abundance of material being presented to audiences, we can change the life of theatre in this country. If there is one thing that I learned from the PQ, it is that the theatre is strongest when it is changing and diverse.

LIAM SHANNON IS A BFA 4 THEATRE ARTS MAJOR WITH A CONCENTRATION IN DIRECTING.

THE PATH FORWARD IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THEATRE IS NOT LEAVING THE OLD BEHIND, IT IS TAKING IT WITH US AND UTILIZING IT ALONGSIDE EXPERIMENTATION AND REIMAGINATIONTHE STORY OF LARRY (ABOVE) THE CROWD (BELOW) PHOTOS: JAN HROMADKO

NORA EVISION (SHE/HER) IS A BFA3 THEATRE TECHNOLOGY MAJOR

ROMAN JONES (THEY/THEM) IS A BFA 4 THEATRE TECHNOLOGY MAJOR FROM CHICAGO, ILLINOIS.

OLLIE (THEY/THEM) IS A BFA4 THEATRE TECHNOLOGY MAJOR FROM DENVER, CO.

JAMES DOOLITTLE (HE/HIM) IS A BFA3

THEATRE TCHNOLOGY MAJOR FROM DENVER, COLORADO.

THE THEATRE SCHOOL AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY

MANAGING EDITORS: CAMILLE PUGLIESE AND LIZ BAZZOLI

EDITING SUPERVISOR: KRISTIN IDASZAK

COVER PHOTO: JAKUB HRAB