The Good Life

Le er from the Editor

Hi all!

I am so excited to announce the Fall 2025 edition is issue we are looking at patterns and themes of the past and what is being done and what we can do to make positive changes. Whether we are recycling past material or challenging old norms, I am excited to share powerful storytelling that aims to speak up and make positive change.

We have curated an edition in the face of losing sight of what a free press is and it is important that we speak out and celebrate the untold stories that enhance our world. Our issue is highlighting stories that reimagine things that are already found and what new meaning we can give to them. e creativity and energy that we have put into each page is meant to uplift and inform our audience about a number of issues and ideas.

e Good Life has been a publication that I have worked with since my freshman year, and I am so grateful to be working with a team of passionate, talented and creative people. I am so proud of our team, especially my exec sta : you guys are rock stars! I hope you enjoy all of our content and thank you from the bottom of my heart for all your support on creating such an awesome edition!

All the best,

Cecilia Catalini Editor-in-Chief

Sophia Brownsword

Cali Buckley

Kiran Hubbard

Daisy Polowetzky

Karina Babcock

The Good Life

Sophia Brownsword

Assistant Editor

Jenna Sents

Editorial Assistant

Cam Cyr

Environment

Kiran Hubbard Lifestyle

Karina Babcock

Sarina Dang

Fashion

Claire Martin Fashion Team

Claire Martin

Presli McCarty

Isabella Tatone

Social Media Director

Cali Buckley

Sophia Brownsword

Ally Goelz

Kiran Hubbard

Claire Martin

Presli McCarty

Mikayla Melo

Ava Plofsky

Daisy Polowetzky

April Stelle

Isabella Tatone

Cover Design

Caitlyn Begosa

Abigail Aggarwala

Hailey VanAlstine

e writing contained within e Good Life expresses the opinions of the individual writers. are not those of the editorial board, Syracuse University, the O ce of Student Activities, the Student Association and the Student Body. e Good Life reserves the right to edit or refuse submissions at the discretion of its editors. magazine is published twice during the Syracuse University academic year. All contents are copyright by their respective creators. No content may be reproduced without the written consent of e Good Life editorial board.

Fashion Lifestyle

The Words on the Wa 15 By A y Goelz

Syracuse Runs on Side Gigs 17 By Ava Plofsky AI Chatbots: a Friend or Foe? 19 By April Ste e NYFW Red Carpets: Where iPhones Outnumber

Editors 21 By Claire Martin

Daisies Blooms With Vintage Fashion and Community Connections 23 By Presli McCarty

Art, Found Objects 25

Isabe a Tatone and Sophia Brownsword Le er from Abroad 29

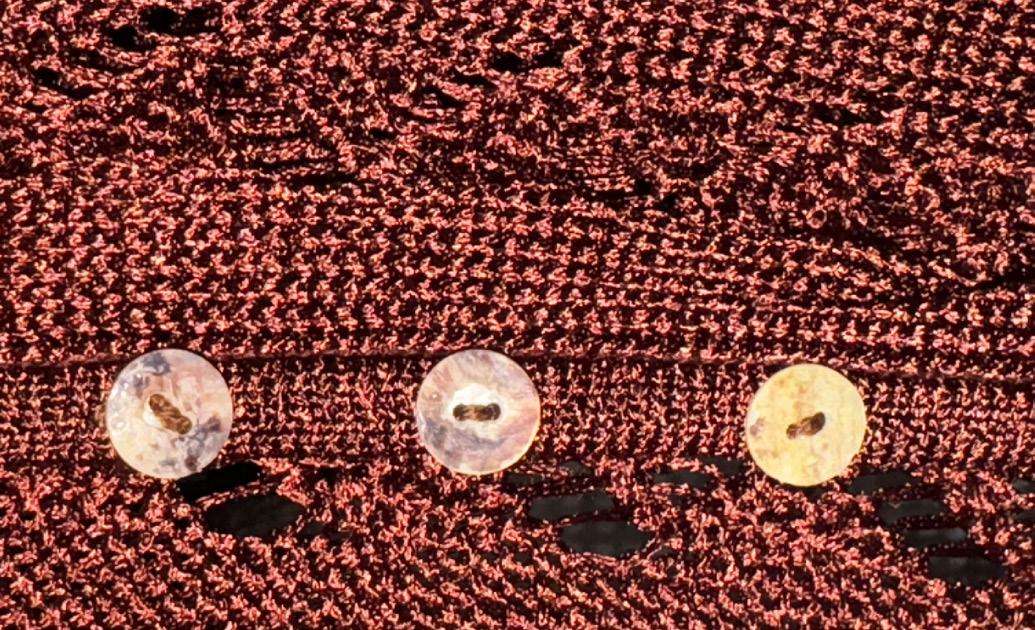

Revamping the Mobile Thri Scene

A student-run business ca ed Revamped aims to not only provide thri ing services for customers but to help poor communities in Syracuse gain access to a ordable second-hand clothing.

By Cali Buckley

Ava Lubkemann’s summer after her freshman year at Syracuse was funded by what other students threw away. A junior studying environmental engineering, she spent nights on South Campus lifting lids on dumpsters and pulling out laptops, clothes, unopened food and piles of barely used dorm essentials—perfectly good items students tossed without a second thought.

Growing up in rural Virginia, resource scarcity made dumpster diving familiar, but she hadn’t actually done it herself until she arrived at Syracuse University and saw just how much waste the campus produced.

One night, the Department of Public Safety stopped her. O cers asked for her ID and what she was doing; she explained she was collecting usable items from the trash. ey talked about recently con scating items

from a man doing the same thing—but because Lubkemann was a student, they let her keep everything.

Afterward, she couldn’t shake the double standard.

“ at barrier was really interesting to me between students and community members, and something I like to call status-based waste, which I’d never thought about before,” Lubkemann said. “Like a dumpster has more protection than a human being, in certain cases, and access is barred from certain populations, which I think is absurd.”

is encounter helped Lubkemann create Revamped, a student-owned mobile bus startup where customers can buy secondhand clothing in the Syracuse area. Syracuse is divided by I-81, which can make it hard for residents to get around the city. With a mobile storefront, Revamped can get to customers easily and address resource scarcity in communities.

After learning about the basics of business and the intersection between engineering and product development, Lubkemann applied class concepts to build a plan for Revamped.

At Syracuse University, Lubkemann estimated student textile waste to be approximately $53,000 a year. Instead of students throwing their old clothes, costumes, bedding and fridges into the trash rooms, Revamped collaborated with e Center of Excellence, placing large donation bins at all student dorms to minimize waste.

“Ava will tell you, the average college student wastes about 640 pounds of waste per year, about 80 pounds of that being just textiles,” Isabella Carter, a junior studying television, radio and lm and the marketing manager of Revamped, said. “I feel like if you can mitigate that at all, then that’s your responsibility, or at least you should kind of want to.”

Over the summer of 2025, Lubkemann and Carter began to remodel an old bus to act as their new storefront.

Lubkemann had realized the only thrift shops near SU were 3 fteen and e Salvation Army. Although e Salvation Army is known for providing a ordable second-hand clothes, she couldn’t help but notice how most clothes were marked up, including basics like workwear and plain t-shirts. Lubkemann believes that they upsell their stock to cater to a younger audience, they push out people who actually need the clothes.

From this observation, Lubkemann not only wants to mitigate waste but also provide second-hand clothing at a more reasonable price. Instead of selling t-shirts for around $50 like e Salvation Army does, according to Lubkemann, Revamped wants to sell its items in a $5-20 price range based on the condition of the item.

While Revamped’s business has just begun, the mobile shop has held a few events this past spring.

At the Wild$ower Armory, a local multivendor marketplace downtown, Lubkemann and Carter took bags of clothes and hosted a small temporary pop-up. eir mission remains to help the whole community.

“Once we get our name out there within that space that’s not directly connected to campus, we’re going to start phasing out into the general community,” Carter said.

“

at barrier was really interesting to me between students and community members, and something I like to call statusbased waste, which I’d never thought about before.”

Revamped isn’t just a mobile bus that goes place-to-place selling a ordable quality items—they aim to also teach their community about sustainability in hopes of changing local perspectives on consumerism

and fast fashion. Lubkemann and Carter recently launched two new podcasts that aim to educate the Syracuse community by focusing on sustainability and promoting conscious consumerism.

“Histories of Garments” will explore the cultural signi cance and identity-forming qualities that clothing has provided throughout history. “Trash Talk” aims to promote sustainable initiatives around central New York and educate people on where they can outsource their funds and buy sustainable items.

“Homemade clothing, like if your grandma knits your socks, is much more likely to last longer than socks that you were to buy from Walmart, because they have a personal attachment,” Lubkemann said. “ ey have an attachment to identity in it. And you know, they mean something to you.”

Illustration by Caitlyn Begosa

The Future Isn’t Binary: AI is Both a Problem and a Possibility

Even as Dan Pacheco warns us about environmental costs, security risks and misuse, he argues that AI’s potential for storyte ing and community impact is too signi cant to ignore.

By Sophia Brownsword

Newhouse professor Dan Pacheco rst began working for the Denver Post in 1995, where he recalls some of his coworkers’ negative attitudes toward the new technology he walked in the door with: a laptop. His beat was to cover the internet, writing stories about how people were beginning to live a large part of their lives online. He remembered some of the rst things he reported on—like how the internet allowed patients with the same types of cancer to connect and discuss treatments or various new clinical trials available to them.

When it came to helping others adapt to technology, he was there. Teaching his coworkers how to use a mouse and the di erence between a double click versus a right click. But he still remembers the way people turned their noses up when he rst walked in with his laptop. Something so entirely integral to daily modern life was back then viewed with the same fear and aversion many currently have towards arti cial intelligence.

Every single day, e New York Times and other big publications publish multiple articles on the subject of arti cial intelligence (AI). Topics like growing trends of emotional attachment to arti cial intelligence, or the prevalent environmental impact being caused by the data centers powering AI, dominate discussions over this new technology. But its prevalence has only grown—this fall semester, Syracuse University became one of many to o er university-sponsored premium subscriptions to a generative AI chatbot service.

As Innovation Chair of Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Pacheco is constantly interacting with and exploring new technologies. He currently teaches MND 413: Emerging Media Platforms, a class where students are introduced to some of this new technology and spend the semester exploring and using it to aid storytelling projects of their own. And despite his personal interest in things like virtual reality or arti cial intelligence, he understands when people hate it.

“I think it’s actually okay to hate things that you still then realize, ‘Well, I need to understand how this works,’” Pacheco said. “Because you can’t hate your way out of a trend that is taking over so much.”

He understands the fears that come with new technologies. He recalls one of the rst times arti cial intelligence scared him. Listening to journalist Kara Swisher on her podcast “On with Kara Swisher” sit down with the parents of the teenager who got into a relationship with OpenAI’s ChatGPT that led to his eventual suicide was one of those moments.

“ at was beyond a scare. at’s like a fouralarm re. ese things should not be used as therapists,” Pacheco said. “It looks like the industry is listening to that, but I don’t think they’re doing enough.”

And when it comes to discussing the prevalent environmental concerns surrounding AI usage, Pacheco admits that it’s a problem that needs to be addressed. But he also understands that even if we got rid of AI today, negative environmental e ects would still be an issue due to the heavy digital presence of the modern age. He sees it as more of a problem of capitalism than anything.

According to an article published by Business Insider in September, there was a tally of 1,240 data centers already built or approved to be built at the end of 2024. Data centers are a major part of the problem when it comes to the environmental concerns of AI usage— they require a large amount of electricity as well as water to be used almost constantly as a coolant. According to Stanford University, total global investment in AI has increased thirteenfold since 2014, and a large chunk of investment is being used to develop more data centers. Pacheco thinks this issue needs to be addressed systemwide— he equated a solution resembling the United Federation of Planets from Star Trek—and he believes the issue needs to be addressed as soon as possible.

Pacheco doesn’t fail to recognize the problems with AI. But he also sees AI for its potential bene ts and all the good that can come from it.

Currently, he is working on a project called Agriquest, in conjunction with the Northside Learning Center in north Syracuse. Students at the learning center take culturally signi cant family recipes and grow various ingredients needed for them at the Salt City Harvest Farm. And then, using virtual reality technologies, they’ve taken photos of the food and what was planted, natural sounds from the farm and other information and compiled it into immersive virtual reality experiences, which are currently on exhibit at the Syracuse Museum of Science & Technology.

“ e unknown really intrigues me. What could be possible that was impossible before. What new things can happen, new things that are good, or need to be pursued that aren’t. If we focus on that, a thousand owers can bloom,” Pacheco said. “I do bring kind of a glass half full view.”

Illustration by Rylee Dang

Secondhand as a First Resort Sustainability practices in Syracuse and beyond combat resource extraction and waste.

By Kiran Hubbard

IKEA has come to Syracuse—bringing with it roughly 1% of the world’s commercial wood supply, according to Paci c Standard magazine. With a new mini-location open in Destiny USA as of Nov. 21, IKEA is now another venue for students to purchase dorm and apartment amenities. Many of these will likely end up in the trash by the end of the year.

e Swedish retailer uses approximately 17.8 million cubic yards of timber to build around 100 million pieces of furniture every year. But along with uniformity and a ordability, this type of massmanufacturing presents environmental and social issues.

But the footprint of a mass-produced commodity starts far from the store that will sell it, especially in competitive product markets.

“ ere’s a phrase there that’s called the race to the bottom, the bottom being the least amount of environmental regulation in the area it’s produced, and the least amount of worker protections in terms of anything and everything,” Michael Kowalski, a professor of industrial and interaction design and design studies at Syracuse University, said. “And you don’t really see

that as an end consumer, buying that thing at IKEA or wherever.”

Although Kowalski said the average consumer may object to the working conditions many of their products are made under, budgetary restrictions can deter people from purchasing more responsibly-sourced items. His sustainability research intersects with human psychology, examining emotional attachment to objects and how knowledge of the origins behind a product impact consumers.

“It does seem like when people get a better sense of the e ort and all the things that go into making something better and having a better process, once they understand it more, they’re more willing to pay,” Kowalski said. “[Consumers] need to have some sense of the social and environmental conditions that go into making things.”

According to Morgan Ingraham, Program Associate for the Institute for Sustainability Engagement at SU (ISE), the most sustainable and budget-friendly choice consumers can make does not involve any actual consumption. Rather, reusing and repairing items they already own is a best practice for moving toward

what she calls a circular economy, where materials are kept in a cycle of use instead of a linear process ending in a land ll or incinerator.

The ISE focuses on community-facing sustainability work. One of its programs involves hosting something called a repair cafe: an event where individuals can bring their broken furniture and learn how to fix it themselves. Repair Cafe CNY happens throughout Central New York twice a year, and there are approximately monthly repair events at the Central Library in downtown Syracuse.

When repair is not an option, Ingraham said buying used furniture and other goods is a bene t-laden alternative.

ese are salient issues for students living on a college campus, which tends to be a hotbed for waste—especially at either end of the year. SU students in organizations like ISE and in various academic programs are developing solutions to ght this trend.

For Industrial and Interaction Design senior Lily Minicozzi, secondhand shopping is a personal passion as well as a socially-conscious decision. She enjoys the scavenger hunt of looking for items to curate her own style, giving her more creative freedom than traditional stores.

Secondhand retailers, digital resale marketplaces and hand-me-downs from peers exist as sustainable alternatives for students. ose who already own furnishings can also implement the practice of repair instead of replacement.

“Facebook Marketplace is probably my greatest addiction,” Minicozzi said. “Any aspect of buying something, I feel like I always try to see if I can buy it used before I buy it new.”

Minicozzi said other students might not like the chase of seeking out used goods, especially during the bustle of college life, but that they take the option if it’s put in front of them. is is why pop-up ea markets and fairs around campus are wellattended, because they’re so accessible to students.

“It’s so much more a ordable for the individual, but it’s also so much be er for the planet, and for the community and for your health,” Ingraham said. “There’s a lot of nuances to the manufacturing process of why you might not want to be buying new and fast and cheap furniture, because it could be actua y very dangerous for your health.”

As part of the SGA Sustainability Forum’s Green Innovation Competition, Minicozzi was the co-recipient of a $15,000 award for a proposal to reduce waste on campus. Due to loss of funding, the program was never

implemented, but Minicozzi is hopeful that the idea can live on through other initiatives from the Blackstone LaunchPad and sustainability management.

Analysis of SU’s waste patterns showed spikes when students were moving in or out of housing. Minicozzi said much of the waste actually comes from the packaging for products, not necessarily the items themselves. Her proposed system to mitigate this waste would keep dorm and apartment items in a cycle of use within the buildings, reducing the need for the next round of residents to purchase.

“We’re all very aware and we have good intentions, but I think at the end of the day—myself included—you just get caught up in your life and you don’t actually follow through with those things that you believe in,” Minicozzi said. “Creating systems that make it easier for people to carry out those intentions that they have is the end goal.”

While proposals for more waste-conscious models are being proposed on a larger scale, small steps of success can be simple.

“ ere’s a lot of opportunity that isn’t too di$cult to actually accomplish for students. Just to address maybe feelings of helplessness that some people might be feeling when it comes to sustainability, which is this huge concept,” Ingraham said. “You could really just do small things on the small scale, in reuse and repair, and make a di%erence in your community.”

Illustration by Abigail Aggarwala

Sustainability at Syracuse Persists

The Syracuse University’s Dynamic Sustainability Lab helps organizations transition to sustainable solutions despite political pushback.

By Daisy Polowetzky

Reduce, reuse, recycle. Shut the sink o while brushing your teeth. Carpool to work. Most people are familiar with what sustainability looks like on an individual level, but not the complexities of implementing it in communities.

e United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development de nes sustainability as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” And while this is a technically thorough explanation, sustainability in action has a lot more consequences than one may think.

is is where the Dynamic Sustainability Lab (DSL) at Syracuse University comes in. Founded in 2021 by Pontarelli Professor of Environmental Sustainability and Finance, Dr. Jay Golden, the DSL aims to serve as a nonpartisan advisor to industries and organizations on the risks of global sustainability transition. is fall marks the fourth year of the DSL, and the lab remains steadfast in its focus on sustainability transitions.

Sustainability is an ongoing environmental issue. e Trump administration cut the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2026 budget by more than 50 percent, and creating low-carbon and netnegative carbon products is especially challenging. A recent DSL bulletin outlines a major gap in climate data needed by organizations to integrate climate smart solutions, a type of farming meant to help mitigate the e ects of climate change. Because historical observational data doesn’t span very far back and satellite technology is relatively new, researchers are missing key information about climate-related weather events.

But despite setbacks, in the four years since the DSL’s launch, the lab

has published more than 20 collections of research on various climate issues, hosted the Boston Sustainability Symposium and had over 4,000 site views. Most recently, it completed a report for omson Reuters on Gen Z as the drivers for ethical labor. e 62-page report outlines how Gen Z’s economic habits impact modern slavery in the co ee and tea and apparel and footwear industries: in a global survey of 395 members of Gen Z, over 50 percent of respondents said they changed a purchasing decision because of ethical labor considerations.

“I think that the DSL has been one of the most impactful experiences I’ve had at Syracuse, if not the most impactful experience,” said Tyler Branigan, a student research fellow and junior in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public A airs.

Branigan says that working on projects, such as a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) funded initiative on climate agriculture, with other like-minded students is what makes working at the DSL worthwhile. But when President Donald Trump took o ce for the second time in January, projects like the one Branigan worked on had to be rethought and reshaped.

Even before their USDA funding was cut in early 2025, the DSL was told that the lab could only continue its research if it avoided using terms like “sustainability,” “climate smart,” and “carbon neutral”— a di cult task for a lab with “sustainability” in the name. But the DSL persisted. In anticipation of having their projects blocked from continuation, they took all of their climate-smart information and placed it in their own database.

“ e lab is probably one of the only places that has this information, because that climate-smart information has been stripped from the USDA website,” said Branigan. ( e USDA website currently provides climate smart information, but at the time that the DSL’s database was created, USDA employees had been ordered to delete all webpages mentioning climate change, according to Columbia Law School).

e DSL’s budget has also had to adapt to the new administration, as the lab now relies on donations

and university funding to pay student researchers. Previously, the DSL had four USDA-funded projects with approximately nine students working on them, but after the lab lost money from the federal government, many students couldn’t work until donors and SU stepped in.

“We

want those academic sources to be bipartisan and unbiased so that we can pursue policies to help the environment.”

However, the spirit of nonpartisanism keeps the heartbeat of the DSL strong. Despite setbacks from the Trump administration, they still include all political ideologies in their outreach. As climate change becomes an increasingly politicized issue, Dr. Golden organizes panels, talks and workshops with diverse political perspectives. One event featured a prominent Republican chief-of-sta and leaders in sustainability nance.

“Especially in scienti c and policy research, we want those academic sources to be bipartisan and unbiased so that we can pursue policies to help the environment,” said Trisha Balani, a former administrative assistant for the DSL, and a junior in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public A airs and the School of Information Studies.

e DSL’s impartial approach to climate solutions is what makes them a strong sustainability leader in the face of today’s political con icts over climate change — reframing a sustainable future as an opportunity for collaboration, rather than debate.

How AI is helping reduce food waste, one plate at a time

Sustainability practices in Syracuse and beyond combat resource extraction and waste.

By Karina Babcock

The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that 30-40% of American food ends up in land lls.

For schools like Syracuse University with bu et-style dining halls, this issue is especially prevalent. Students may take more than they can eat, or want to sample di erent food without nishing everything they’ve taken.

To address this challenge head-on, the Dynamic Sustainability Lab at SU partnered with Leanpath, a company that uses AIpowered technology to track and reduce food waste. Together, they’re working to understand exactly what kind of food gets thrown away and how to reduce the volume of waste.

Leanpath’s Bench Scale software operates through a combination of hardware and AI. First, the countertop scales are equipped with cameras that photograph wasted food. Next, the AI software analyzes the images to identify what type of food is being discarded.

“ e operator who is using the tool still has

to select why the food is being wasted,” said Tracy Smith, Account Director at Leanpath. “You need to know if it’s spoiled, is it overproduced, is it, you know, whatever the case may be.”

Using AI to draw those conclusions represents the dramatic advancement of traditional research methods. Dr. Jay Golden, who leads the Dynamic Sustainability Lab, recalled how his team previously had to conduct manual waste audits.

“Our students were in protective equipment and we separated and segregated and weighed all the di erent types of food waste,” Golden said. “So, [Leanpath] is really a big help, and you don’t get as dirty.”

Students from the DSL worked with Leanpath to quantify waste levels across campus dining halls. eir research revealed areas for improvement across SU’s dining operations. With detailed data on which speci c foods are being wasted most frequently, dining administrators can make

informed decisions about purchasing and portion sizes.

“Here, with the Leanpath software and the imagery, you can really say, oh, we’re purchasing too much cheese, or it’s too much rice,” Golden said. “ is precision helps the university to potentially reduce the volume as well as the cost of having to purchase too much.”

While the research and technology make a sophisticated team, both Golden and Smith

emphasizing the importance of building healthy habits. “Even if it wasn’t something they thought about before, we can raise awareness to the gravity of this issue and also the fact that it exists and we all have a part to play.”

However, the use of AI to promote sustainability raises a question: doesn’t AI have its own tremendous carbon footprint? Running large models takes processing power that requires signi cant use of water and energy.

SU’s many dining sustainability initiatives. e university has already phased out single-use plastics, introduced compostable cutlery, and partnered with EcoLab for environmentally-conscious cleaning products. Organizations like e Food Recovery Network collect unused food from dining centers and deliver it to local non-pro t agencies, addressing both food waste and food insecurity.

For Smith, whose mother instilled in her an early aversion to wasting food, Leanpath’s

Illustrated by Abigail Aggarwala

The Words on the Wa

Syracuse University has the First Amendment, a promise of freedom, plastered on the side of one of its buildings, but a er SU’s low free-speech ranking and controversial policy shi s, some feel that promise was broken.

By Ally Goelz

Every time you walk past Crouse or make your way towards Marshall Street, the words of the First Amendment, guaranteeing free speech, press, religion, protest and petition to Americans, are impossible to miss on the side of Newhouse 3. Yet, for Syracuse University students, those rights are increasingly called into question.

is past September, the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) released its 2025 College Free Speech Ranking, based on students’ experiences when it comes to free speech expression on campus. SU scored a D minus, which on a 100 point scale is a 60.6. e highest score was given to Claramount Mckenna College, which scored a 79.90.

“ e reason we protect free speech is to protect di cult speech that o ends people at the margins, popular speech does not rewire protection,” Ryne Weiss, FIRE’s director of research, said. “It’s really unfortunate.”

At a university that prides itself on free speech, students are beginning to ask: how truly free is our speech?

e Trump administration is cracking down on higher education— from rolling back Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs to targeting international students—making students feel less and less safe sharing their opinions.

In January, President Trump signed an executive order to “end illegal discrimination and restore merit-based opportunity,” attempting to wipe DEIA language in higher education. SU followed suit with their decision to close the O ce of Diversity and Inclusion, replacing it with the O ce of Community and Culture.

“ e Trump Administration has attacked free speech on campuses from a number of di erent angles, whether it’s going after university funding or presenting this compact they’ve recently done to try and get schools to agree,” Weiss said. “It’s a really tough time for free speech on campuses nationwide.”

While Syracuse did not sign the administration’s Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education, urging universities to relinquish institutional academic freedom in exchange for favorable treatment in the future, SU did recently pause 20 academic programs, including African American Studies.

One senior at SU, Amaya Saintal, said the cuts to the department made her feel as though her culture is being put at risk.

“It does leave a lot of wondering whether or not the school wants to prioritize us as students and o er more conversation, dialogue and opportunity because a lot of these spaces that are being taken away were also spaces where a lot of us connected and had access to di erent opportunities and connections,” Saintal said.

In September, FIRE published a letter to SU urging the university not to punish faculty members over comments made about Charlie Kirk’s death. e letter argues the university must “stand with free expression and refrain from punishing faculty members.”

“It is in moments of controversy that institutional commitments to free speech are put to the test,” the letter says. “If Syracuse chooses to ignore its free speech obligations and punish protected speech, it will open the door to censorship of a limitless array of views on campus, while chilling other individuals from sharing their opinions.”

One on-campus organization, Syracuse College Dems, also condemned the suspension of the two professors, saying it “raises concerns about free speech and academic freedom on our campus.”

“Universities cannot claim to value free speech while disciplining faculty for expressing controversial or unpopular views,” the organization said.

But these changes and decisions did not a score. eir yearly survey takes place between January and May, with the cut-o for policy changes and incidents in their database ending June 1. e scores then get released in September.

But Weiss explained these changes can penalize SU for next year, putting the university “extremely low in the rankings.”

FIRE’s rankings are based on three main components: university policy, behavioral incidents, and student attitudes.

e rst component evaluates university policies and how they could infringe on student speech. FIRE then “grades” the institutions on a red, yellow, and green scale. is year, FIRE adopted the “Chicago Statement on Institutional Neutrality,” giving credit to schools who added it. SU was one of the schools that adopted the statement and was scored as a “yellow light institution” for 2025.

Behavioral scoring looks into incidents within the student body that have been led in FIRE’s database. e database captures attempts to de-platform scholars, speakers, art exhibits and movie screenings and examines attempts to sanction students for protected speech.

e last component, student attitudes, is based on FIRE’s yearly survey. Within the survey, students are asked how free they feel, how con dent they are to express themselves, how frequently they need to “self-censor,” and how much faith they have in their college’s administration.

Students in the survey are also asked about the ideological diversity among campus speakers and what actions they believe the university should take when it comes to “o ensive speech.”

FIRE penalizes a university for actions against free speech but awards “bonus points” when they protect it.

Illustration by Isabella Salvi

Syracuse Runs on Side Gigs

From late-night snack runs to campus rides, on-demand services like Uber and DoorDash fuel student life, but for drivers, these side gigs help them get by.

By Ava Plofsky

With the click of a few buttons, dinner or a ride is on its way to you. On-demand services, like Uber or DoorDash, have become a lifeline for many college students who likely don’t have cars on campus. And particularly on Syracuse’s campus, the warm solace of an Uber beats trekking through the chilling snow in winter months. While these services can quickly create a dent in your bank account, many students are willing to click the “order” button. Of 60 Syracuse students surveyed, 72.2% said they take an Uber either weekly or monthly. While the 44 and 344 centro bus routes can bring students to South Campus, the closest supermarket, Tops, is still a twenty minute walk from the Goldstein Student Center. In fact, 61.37% of students without access to a car said they rely on Instacart or Uber to get their groceries.

Transportation and delivery services would not be possible without the multitude of drivers from the Syracuse area. For many of them, this vocation serves as a side gig— a way to supplement their primary income.

“Uber pays my loans,” Abdulsalam, an Uber driver, said.

While Abdulsalam works as an accountant during the day, Uber is his night job. He hopes that one day accounting will be his only job. With an average household income of $45,845, according to New York City Demographics, many Syracuse residents need a second job to cover their cost of living.

“It’s exible. I can work whenever I want and there isn’t a speci c time,” said Abdul, a Syracuse resident who works for both Amazon and Uber.

On apps like Uber and DoorDash, all workers have to do is press a “Go” button to clock into their shift. is exibility makes on-demand services an easy side gig as many drivers work nights and weekends when they have time to spare. Fortunately, these are most often the times that Syracuse students are out and about, and in need of a meal

or a ride after a long day of classes. While the self-determined hours are a major perk, many drivers believe that the Uber app does not compensate them fairly.

e Uber app calculates a base fare for each trip based on distance, tolls, auto insurance, and airport fees that the driver will have to cover. Each driver is then given a percentage of that base price. Uber will then take a certain percent of the fare for themselves—usually 2030%— varying city to city. As many drivers stay within the parameters of Syracuse, they make less per ride. erefore, to see any substantial income, a driver has to pick up multiple trips a night.

“[ e app] charges customers a lot of money and then gives Ubers, like, ve cents,” Abdul said.

Although slightly exaggerated, Abdul’s frustration is clear. He took particular issue with Uber’s claim that part of his pay went toward auto insurance—a sum he said could barely cover the cost. Most months, he ended up paying for insurance out of his own pocket.

Despite the unfavorable pay, many Syracuse residents depend on this second job to support their primary income. is indicates that for many citizens, the wages of working one job in the current economy are insu$cient in supporting today’s cost of living.

ere are ways to push for change: voting, community organizing, or writing to/calling representatives help the ght for policies that will improve wages. One organization, called the Workers Center of Central New York, brings together employees who are ghting for fair wages and better treatment in the workplace. Based in Syracuse, they organize and lead protests to in uence policy, hold training on workers’ rights to equip workers to demand fair wages, and represent vulnerable populations, like immigrants. All so one day, ideally workers won’t need to rely on these “side gigs” to support themselves.

Illustration by Rylee Dang

Chatbots: A Friend or Foe?

AI chatbots are becoming a resource for at home therapy nationa y, but what are the consequences of having ChatGPT as a therapist?

By April Stelle

Internet persona Kendra Hilty went viral on TikTok this past summer, receiving harsh feedback from her audience as told a story about allegedly being taken advantage of by her psychiatrist. In light of recieving this feedback, Hilty turned to another opinionated source for support: arti cial intelligence (AI). She began consulting with various AI chatbots from companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, joking with the chatbots and sharing her feelings with them--basically, treating them like humans.

But Hilty is not the only person who has turned to AI as a therapist. According to a survey conducted by Sentio University this past February, about 49% of large language model (LLM) users with self-reported mental health issues use LLMs to address concerns. When asked why they chose arti cial intelligence over mental health professionals, 90% cited accessibility and 70% cited a ordability. e majority stood by their decision, as 75% reported that their experience with an LLM was on-par, or

LLMs improved their mental health.

Last fall, 16-year-old Adam Raine from California began using ChatGPT for homework help, as many teenagers do. But the dialogue between ChatGPT and Adam started to change as he started to ask questions about his own mental health. Eventually, Adam asked about the most e ective ways to commit suicide and instructions on how to do them, which ChatGPT provided with little resistence. Adam committed suicide, but this isn’t the rst case of alleged AI assisted suicide.

Tragedies like Adam’s have not stopped the continued use of AI as a mental health resource for teens. Heidi Bley, a sophomore at Penn State University, has been using AI as a mental health tool on and o for about a year. Bley had a therapist before attending Penn State, but was unable to continue seeing them after she moved out of state.

“I’ve only ever used [AI] when I needed to kind of talk myself out of something, and

with someone else, so I just needed a robot to talk to,” Bley said, laughing slightly.

Bley said AI provided her with a second opinion in situations when she felt stuck.

“I feel like AI is completely di erent, you can alter what you want to be said to you,” Bley said. “AI will give you a general answer right o the bat and then it’s gonna ask you questions: ‘Do you want me to change this or change this?’ but when you talk to a therapist, they’re very one-track-minded.”

Serife Tekin, an associate professor at the Center for Bioethics and Humanities and SUNY Upstate Medical University, cautions against relying on AI as a therapist.

“An AI tool is going to be intrinsically limited in so far as it will, in the best case scenario, kind of re ect you or tell you what years and years of psychological research have told and that may not neccessarily be the best way,” Tekin said.

Tekin, a philosopher by training, began researching AI mental health resources in 2018 when she heard that an AI bot, called Karim, was being developed to address mental health issues for Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

“In the case of AI bots, these are not autonomous agents.

ey’re not trained in addressing mental health issues in the ways that human beings are. And if something goes wrong, they do not know how to handle it,” Tekin said.

Je Rubin, Senior Vice President for Digital Transformation and Chief Digital O%cer for Syracuse, and a professor at the School of Information Studies believes AI chatbots are meant to validate and encourage users.

“ at is where these issues come in,” Rubin explained.

To address this issue for mental health conversations, OpenAI updated their GPT-5 model this past October to recognize signs of mental distress and direct users toward professional support when needed, and hired a council of experts in mental health, youth development and human-computer interaction. GPT-5 has reduced harmful or inappropriate responses to mental health questions by 65% to 80%.

“ e problem with that is that’s still 20% that they’re not reducing.” Rubin said regarding the update. “You’re still talking about 490,000 users a week who are still having conversations negatively a with mental health. I mean, that is a staggering number.”

Rubin believes that while AI can be programmed for mental health purposes,

ATIA– stock.adobe.com

he does not believe they should be for “I encourage young people to develop

Design by Brooke Slaton

NYFW Red Carpets: Where iPhones Outnumber Editors

New York Fashion Week (NYFW) took social media by storm this year, receiving coverage from media outlets to in uencers.

By Claire Martin

On the red carpets of NYFW this year, the most noticeable accessory wasn’t a designer handbag, it was the iPhone. A types of in uencers crowded around the runway, trying to capture the perfect and exclusive angle for their fo owers that were not able to a end. Editors and stylists, who historica y have made up a majority of the audience of a runway shows, were harder to spot.

Fashion Week was once a stage for originality, for stylists to put their prized possessions on display for the best of the best in the fashion world. But now it has changed into something di erent. The modern runway, seemingly, is shi ing to cater to not only to those invited to a end, but to the mi ions who experience it through Instagram, TikTok and Youtube.

“Litera y, the second the show started, every single person had their phone out,” said Shayla Ismael, a Syracuse University junior and University Girl Magazine Editor-in-Chief who a ended NYFW.

Previously, fashion editors decided which co ections from these runways would dominate the upcoming season. Now, TikTok in uencers are the ones that control the media.

“When a show happens, it’s litera y on social media in seconds, like not even there’s no secrets about it,” Ismael said.

As a public relations intern for Lindsay Media, Ismael understands that audience members are invited to shows to create online bu . She explained that people who are invited are somewhat

expected to have their phones out and post.

“Each brand is di erent and has its own approach,” said Dyanna Gamarro, the Public Relations Coordinator at Altuzarra. “There’s a growing opportunity for brands to reach audiences through in uencerdriven social coverage, which is very appealing.”

Gamarro coordinates social media and in uencer relations—she plays a large role in the plans to prepare for NYFW.

“Editors continue to hold their wedeserved place in the industry,” said Gamarro. “I don’t think that wi or should ever change.”

The in uencer era of fashion shows is inevitable. Alongside NYFW, the infamous Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show was not only ed with in uencers in the audience, but on stage as we

In an analysis from Traackr, an in uencer marketing so ware, the 2024 Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show implemented a fu y designed in uencer-strategy where they activated over 2,096 in uencers, generated 5,542 mentions, 66 mi ion engagements and 414 mi ion video views in the week of the show.

Shows aren’t just about the clothes anymore, they are about the reach and impressions that stem from the online bu and excitement.

“There’s a lot of strategy behind a brand’s social presence, li le is

accidental,” said Gamarro. “Brands that consistently achieve strong social moments tend to have a deep understanding of culture and the zeitgeist. Being able to connect with people in that way takes intention and insight; it’s not random.”

Short-form content appeals to the new generations as a ention spans become shorter and more and more content is being pushed out. However, the standard, long-form content goes more in-depth into the unique interviews with creative directors, sharing the vision behind each item.

One solution to this short-form, digital energy may be to create balance. Social media bu obviously grabs a ention of new audiences, yet it is important to restore NYFW’s sense of artistry that they’ve had since the beginning.

Shows could designate time for in uencers and press to capture their content in a way to not disrupt the magic of a runway show, so audience members can focus on truly immersing themselves in the show. This compromise would let brands maintain online reach while giving designers and audiences a chance to re-engage with the cra itself.

Illustrated by Abigail Aggarwala

Crazy Daisies Blooms With Vintage Fashion and Community Connections

Crazy Daisies, a local Syracuse garden and cafe, blends excitement and a sense of community through their vintage fashion sales and a uring daily events.

By Presli McCarty

Syracuse’s small businesses have been ghting a loss of connection within the community for years. e city’s neighborhoods have been fractured for decades due to the construction of I-81 and economic decline connected to the splitting of communities and commerce.

e highway split the 15th Ward, which was the center of African American, Jewish, and

immigrant life in the city, causing homes, churches and businesses to be destroyed and split. As I-81 reconstruction aimed to reconnect neighborhoods advances, Crazy Daisies, a boutique and cafe on the outskirts of Syracuse, is working toward a di erent kind of community rebuilding.

For small businesses, creating a connection to the community is essential to their survival. Crazy

Daisies is nding creative ways to keep this community connection alive through fashion-focused pop-up events and collaborations with local vendors and artists. As Syracuse works to rebuild community ties, Crazy Daisies o ers a small but meaningful example of how local businesses can create exciting new spaces for connection through fashion, sustainability and shared culture.

Jennifer Cox, owner and operator of Crazy Daisies, started it all when she

more sustainably while prioritizing local resources and skills.

He’s noticed through his time at Crazy Daisies that customers often nd inspiration to start thrifting outside of the market, moving further away from fast fashion trends.

opened a small greenhouse oriented ower shop in 2007. In 2019, Cox, alongside her husband Glenn, added a Garden Cafe that served small plates and NYS craft beverages during the weekends. Now, it has expanded into a full restaurant, event space and area for pop-up or ash events created to welcome the Syracuse community into a space of comfort right outside of the city.

Isabella Matro, the chief of operations, runs marketing, event planning and the art markets. Matro has worked at Crazy Daisies since she was 14 years old, and has seen signi cant growth after expanding their o erings to include many vintage and artist-inspired events.

“ e events add a new angle to it because there are so many beautiful artists and other small businesses in the area and we just wanted to nd a way where we can all work together,” Matro said.

To deepen this collaboration, Matro said they work hard to encourage sustainable practices to help eliminate the spread of fast fashion. Items that are showcased at these events are often handmade, found through extensive thrifting and secondhand sourcing.

According to a study titled “Towards Circular Fashion: Design for CommunityBased Practice,” more local systems of fashion can unlock new value both economically and socially within communities. is approach empowers communities to create and consume fashion

Community support surrounding Crazy Daisies has stayed consistent throughout the years. Customer loyalty continues to draw people together, especially around the growing vintage markets.

“She [Jennifer] still has customers that knew her when she was 6 months pregnant with her sixth child opening this business almost 20 years ago,” said Matro about her boss.

Employees at Crazy Daisiers are also loyal consumers of what the business has to o er.

“If our employees are working, they love to get time to go down and shop too. Or they come into work even if they’re not working so they can come to the market,” said Matro.

Henry Cox, son of owner Jennifer, truly believes that sustainability plays a big role in the vintage market.

“I think it’s interesting because it kind of inspires the customers to do something on their own,” Cox said.

He said the markets also bring in a mix of people who may not otherwise cross paths. He gets to see people from every age group shopping, connecting and bringing new life to older pieces.

“You can scan the room and you’ll see the older generation with a motorcycle vibe going on, sorority girls, and then you’ll see even younger people, like high school. You’ll think that one of everybody’s here,” Cox said.

e vendors are just as diverse. Some dealers simply enjoy thrifting and want to share that with others, and for some it’s their livelihood to comb through vintage clothing and sell the pieces to eager customers. Henry is certain that these markets will continue each year, with hopes of continuing to expand to include even more vintage fashion dealers.

“ ere’s something for everybody here,” Cox said.

Illustration by Briana Salas

Found Art, Found Objects

By Isabe a Tatone, Sophia Brownsword

College campuses—pretty much a breeding ground for microtrends and overconsumption. Whether you’re looking for a new powersuit to wear for your class presentation, or are searching high and low to come up with four di erent Halloween costumes that are the perfect mixture of sexy and funny, it’s hard to not feel like you constantly are in need of something. One day a classmate of yours debuts a cute new pair of shoes and before you know it, everyone in that class has the same shoes on but in di erent colors. Now you have something else to add to your wish list.

Fast fashion was a term created by the New York Times, and is de ned as the rapid production of trendy, inexpensive clothes. It was rst used to describe the popular retailer Zara’s business model, and their ability to take clothes from runway to store windows in under two weeks time. As fast fashion becomes more apparent throughout a majority of retailers, we have a rising responsibility to pay attention to the e ects it has on people and the environment.

According to an article published by earth.org, fashion is the second largest consumer industry of water—somewhere around 2000 gallons of water are required to produce one pair of jeans. To keep up with current trends, consumers feel the need to buy an excess amount of clothes. Oftentimes, these clothes are cheaply made, and therefore have a much shorter lifespan than clothes that were produced with greater care and more resilient materials. 85% of textiles go to the dump each year, and thus perpetuates the cyclical nature of fast fashion. Clothing graveyards have begun to develop around the world — land lls lled with unwanted clothes, the most famous spanning 1.2 square miles in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

And fashion isn’t the only industry being taken over by fads that require cheap and quick mass production. Fast furniture—an issue delved into by our environment section editor, Kiran Hubbard—is another industry being eclipsed by this need for speed when it comes to production of goods. Our fashion editor, Claire Martin, discussed the changing norms of fashion shows, as “fast content creation” lls the seats with more in uencers videoing everything on their phones than ever before.

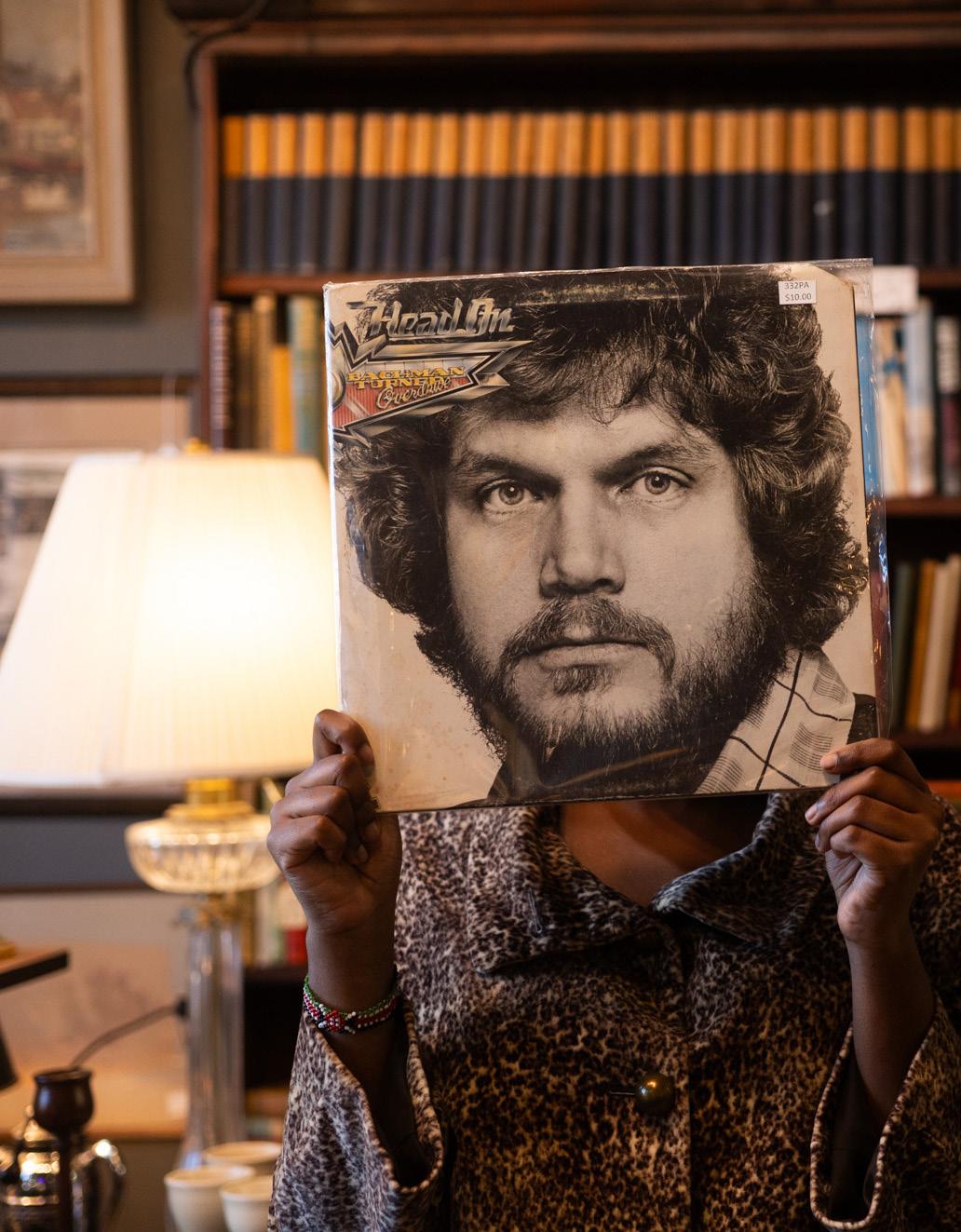

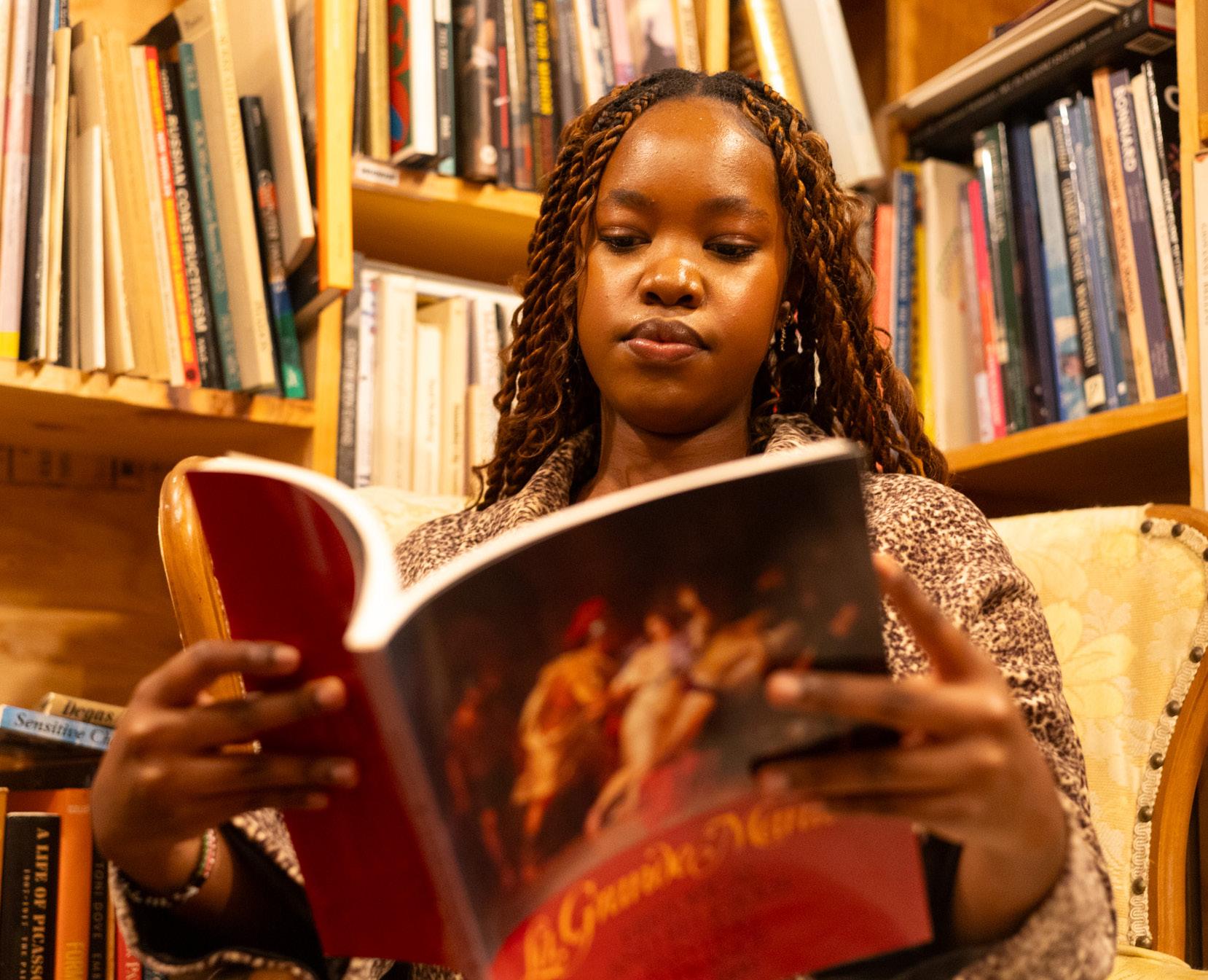

Everything in our lives seems fast nowadays. From fashion to furniture to online content creation to the development of arti cial intelligence, also written about by two of our writers this semester. When it came to this photoshoot, we chose to slow things down a little bit.

Syracuse Antiques Exchange was the perfect place for our models and sta to slow down a little bit. With four separate oors to explore, every object inside had its own story to tell. Books that littered co ee tables inside conversation pits, records that scratched out the background music of cocktail parties or mismatched dishes that lined anksgiving tables. When it came to styling our models, fashion director Emily Dick brought in all her own clothing and accessories.

“I wanted the shoot to give o Fancy Nancy eclectic vibes with the belts, shoes and glasses,” Dick said. “I tried to nd some funky out ts to dramatize the whole shoot, and I got a lot of inspiration when I visited the antique store.”

Currently, in the Syracuse area and beyond, there are many e orts being made to mitigate the issue of overconsumption. Cuse Revamped or Crazy Daisies, two organizations featured in this issue are working hard to make second-hand shopping more accessible. While overconsumption and microtrends are a greater societal issue, sustained by our ever-expanding usage of social media, there are ways consumers can take strides to shop more sustainably. us is the purpose of this entire issue — to promote the art and beauty in the objects that already exist, the stories they may contain and the life we have the ability to restore within them.

by

Photos

Isabella Tatone

Le er From Abroad

By Mikayla Melo

Iam writing this from a bus somewhere along the Frenchcoast, winding my way back to Florence after a weekend in Nice. Listening to Lizzy McAlpine, as I watch the shimmer of the Mediterranean disappearing behind us. In moments like this, it’s hard not to be overwhelmed with gratitude and awe.

Studying abroad in Florence has been a whirlwind. Beautiful. Overwhelming. Disorienting. Grounding. I came here searching for the space to breathe, to shift, to grow outside the version of myself that had been shaped by routine and familiarity. I don’t think I could have predicted just how much growth would actually be required of me.

is morning, I went to order a cappuccino in Nice and hesitated. In Italy, ordering one after 11 a.m. earns you a certain look. A silent judgement reserved for tourists who haven’t yet adapted. ese small cultural di erences used to trip me up. Now, they feel like second nature. Weighing your produce before checking out. Saying “buona sera” after 4 p.m. instead of “buongiorno.” Tiny, seemingly insigni cant adjustments, but they add up. ey signal the way a new place begins to reshape you.

Beyond the culture shocks, there’s something deeply exhilarating about immersing myself in new ways of living. Every day, I’m surrounded by a symphony of unfamiliar sounds and tasts and colors. e lilt of Italian spoken between market stalls. e aroma of fresh espresso and baked focaccia as I wander through narrow, cobblestone streets. Aperitivo that stretches into long, lingering dinners over local red wine and laughter, where the conversation feels just as important as the food on the table.

Olena Panasovska – stock.adobe.com

Veronika Kraeva – stock.adobe.com

by Brooke

I’ve fallen in love with the slow rituals of daily life here. Going to museums just to stand in front of one painting for as long as it takes to notice every little detail. Learning to appreciate sculpture and classical music and architecture not as distant, academic concepts, but as things that pulse with life and story.

Still, it’s not all easy. ere are moments when being an American abroad feels particularly uncomfortable. Especially now, during a time of political unrest and global tension. Florence, like much of Europe, has been a center for protest these past few weeks around the genocide in Gaza. Pro-Palestine demonstrations ll the piazzas. Students chant in multiple languages. Signs appear overnight on overpasses and school buildings. It’s a reminder of how connected -- and divided -- our world is.

It can be disorienting to sit with so much change. I think there’s power in that discomfort. Power in letting go of the need to always feel understood.

What’s surprised me most is how much independence can gro in sort of unremarkable ways. Navigating unfamiliar streets alone. Grocery shopping without streets alone. Google Translate. Cooking dinner with ingredients I can’t pronounce. Sitting with loneliness instead of rushing to escape it, and actually learning from it.

Florence has taught me that growth doesn’t always look like motion. Sometimes it looks like stillness. Like noticing the way Arno re ects the city lights at night. Like ordering a cappuccino in the afternoon just because I want one. Like sitting on the bus, somewhere between countries, realizing I don’t need to have it all gured out.

I’ll return home soon enough. To the chaos, the familiarity, the momentum that will sweep me back into everything I left. But for now, I’m nding peace in learning to trust the in-between.

Design

Slaton

Hunting for a Home Away from Home

For students who cross state lines and international borders for co ege, nding a sense of belonging on campus requires persistence.

By Caitlyn Begosa

Coming from Michigan, I traded cold, never-ending winters for – well – cold, never-ending winters when I chose Syracuse University. Before freshman year, I imagined life 400 miles from home: new adventures, new faces, new routines, everything new but the weather. I was convinced I would thrive.

But the moment I walked into Sadler Hall four years ago, that excitement dissolved. Going “outside my comfort zone” suddenly felt less inspirational and more intimidating. I wasn’t sure how I’d ever make University Hill feel like home.

Now, as a senior, that feeling didn’t last. I found belonging through classes, cultural clubs, Greek life, student media and that sense continues to grow. Home on campus isn’t something you pack with you, but something you slowly build.

e sense of belonging is essential to thriving academically and

socially in college. Loneliness, language barriers, social anxiety and cultural isolation are signi cant challenges to nding a campus support system. Yet, students continue to bridge the distance between the home they left and the one they’re trying to create.

According to Duke University’s O ce of Undergraduate Education, “belonging is

“I found people who speak French, and that gives me this little piece of home.”

linked to persistence in college, and research shows that developing a stable sense of belonging early in college—or at least a strong sense of optimism that one will eventually belong—has cascading e ects that promote help-seeking, relationship development, stronger achievement, and even better mental and physical health.”

Senior Ines Harouchi, from Morocco, remembers arriving to an almost-empty campus for international student orientation her freshman year. Even though she attended American schools back home, the quiet felt unsettling. Once the campus became lively, she found herself growing more comfortable and open to meeting new people.

SU a nity groups and cultural clubs help create that shift, o ering community through shared identity.

For junior Jasmine Padilla, who traveled from California, home on campus emerged once she found a culturally centered space. She joined La L.U.C.H.A., Latine Undergraduates Creating History in America, her sophomore year.

“My freshman year, I wasn’t in it,” said Padilla. “I really found myself being like, ‘Where are my Hispanic people at, you know?’ After I joined, I was like this is it. I was just looking in the wrong places.”

La L.U.C.H.A. uses culture as a connector, hosting events centered on traditional foods, shared holidays, and the Spanish language. eir National Co ee Day celebration featured brews from Mexico, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic and Colombia.

“Co ee is so welcoming in our culture,” Padilla said. “It really feels like how you greet someone at home.”

Since SU doesn’t have a Moroccan a nity group, Harouchi sought connection in di erent ways like religion and language. e Muslim Student Association o ered familiarity through potlucks lled with food and traditions.

“Sometimes language is a big uni er,” Harouchi said. “I found people who speak French, and that gives me this little piece of home.”

One place she feels especially connected to is the International Student Success Program. rough events about career development, community building and navigating life in the states, the o ce became a source of support and comfort for Harouchi.

Senior Chidera Olalere, from Nigeria, always expected to study abroad for college. She arrived for orientation excited rather than

nervous, but homesickness still surfaced, especially when cultural connections were hard to nd.

Food was a big challenge. With no nearby Nigerian restaurants and RA duties keeping her tied to dining halls, Olalere struggled to maintain a culinary connection to home. Over the summer, she was nally able to cook the dishes she had been missing when she stayed in a Syracuse apartment.

“Being able to eat food that actually tastes like the food from home helped me feel at home when I wasn’t,” said Olalere. “I think that’s something really small that can make a really huge di erence.”

Olalere also attended cultural club meetings but noticed a disconnect – her lived experiences didn’t align with those born in America. Instead, she found community within her STEM majors, as well as organizations based on shared interests and faith. ese spaces o ered a sense of belonging rooted in shared purpose, instead of cultural sameness.

people in those places that share the same values,” Olalere said.

Her most consistent lifeline and cultural connector is calling her family daily, a simple practice that keeps her grounded in who she is.

A student’s sense of belonging continues to develop over the course of school, shifting and evolving along the way. rough cultural clubs, academic communities and everyday routines, students build that sense of home by seeking connection and nding spaces where they can be fully themselves.

Now a student assistant at the International Student Success Program, Harouchi helps other international students begin that journey.

“I want to contribute to our success on campus and make sure we have resources available to thrive just as well as domestic students,” she said.

“As you pursue those things that matter a lot to you, you’ll nd

Illustration by Briana Salas