The Forgotten Female Composer

Dr Anna Beer

The simple fact is that it is impossible to tell the sex of a composer, simply by listening to their music. Does that mean the sex of a composer doesn’t matter? Hell no. Because what we believe about men, women and creativity is what matters – and has determined, for too long, who is allowed to compose music, what they are allowed to create, and whether their work is performed and remembered.

This is frustrating for many a composer. For millenia, women have tried to take their sex out of the cultural equation, all the while dreaming of a world in which people forget about your gender and simply commission, perform and hear your music because it’s good. Consider Elizabeth Maconchy, who has been described as Britain’s ‘finest lost composer’. Her luscious work, The Land, was performed at the 1930 Proms to international acclaim (‘Girl Composer Triumphs’ screamed the headlines – she was 23) and she would compose a series of string quartets that have been compared to those of Dmitri Shostakovich. All Maconchy wanted was to be called a composer. All she wanted was for the category of ‘woman composer’ to be rendered absurd, redundant. Throughout her long career, she worked tirelessly to achieve everything that her American predecessor, Amy Beach, suggested needed to be done to create a world in which the public would ‘regard writers of music’ and estimate ‘the actual value of their works without reference to their nativity, their colour, or their sex.’ Get your work out there, advised Beach: compose ‘solid practical work that can be printed, played, or sung.’

The harsh reality, however, is that for every performance of any one of Maconchy’s thirteen string quartets there are hundreds of performances of Shostakovich. As for recordings, the imbalance is even more striking. We are still not in Amy Beach’s brave new world.

Why not?

For centuries, commentators have been quite sure that women ‘betray’ themselves in their music. They could, for example, hear the chromosomes in the compositions of Fanny Hensel, Felix Mendelssohn’s big sister. They were kind enough to say that a small collection of her songs offered an ‘artistic study of masculine seriousness’ but, sadly, a woman could only go so far: all but one lacked ‘a commanding individual idea’. Commanding individual ideas are clearly only possible to produce if you are born male. Another critic admired ‘all the outward aspect; yet we are not gripped by the inner aspect, for we miss that feeling which originates in the depths of the soul and which, when sincere, penetrates the listener’s mind and becomes a conviction’. Yet another felt a lack of ‘powerful feeling drawn from deep conviction’.

Other ideas about women and music are equally pervasive, equally toxic – although every generation finds its own way of making it hard for a woman to be a creator. It’s always interesting to look back and see where the barriers were. In the midVictorian era, the sight of a woman playing the violin was deemed disgusting. As one writer (in The Girls’ Own Indoor Book, attempting to reassure teenage girls in the 1880s) says, ‘I have also in former days known girls of whom it was darkly hinted that they played the violin, as it might be said that they smoked big cigars, or enjoyed the sport of rat-catching.’ By the end of the nineteenth century, those days appeared long gone, and violin-playing was deemed ‘lady-like’, if not a suitable job for a woman. When Henry Wood, the visionary director of Queen’s Hall Orchestra and the man behind the Proms, hired six female string players in 1913 he was right to take great pride in his action but, sadly, other orchestras did not follow suit. Putting aside for a moment the familiar music industry pattern of ‘one step forward, two steps back’ evident in Wood’s hiring policy, let’s consider just why the violin-playing woman created such anxiety. At first, it was because to play the violin was

to distort the proper (aka ‘natural’) posture of a woman’s body. To play the violin the woman had to bend her head, use rapid arm movements, both of which were not deemed appropriate to her sex. Gradually those views changed: so long as the woman remained properly feminine, then she could, and did, play the violin. Female composers made the same trade-off, generation after generation. So long as they behaved in ‘properly feminine’ ways, wrote in ‘properly feminine’ genres, for ‘properly feminine’ forces, they might be allowed to write music.

But then it gets more complicated. A deeper taboo emerges when women become expert at the violin. The violin was itself (herself) understood as female, with its softly curving shape, its belly, back, waist and neck. The real-life woman gets to play the instrument-woman with a stick. A stick. Apparently – and I’m relying on the finest of musicological sources here – the modern bow, which emerged by the end of the eighteenth century in all its sleek concaveness, lessened the connection with archery, but increased its eroticism. No wonder then that the male violinist was often understood as a masterful lover of ‘his [sic] delicate, exquisitely responsive, and beloved instrument, a perception heightened by the soloist’s caressing arm movements and facial expressions, sometimes accompanied by closed eyes, suggestive of inward joy or ecstasy.’ The performer Sarasate, for one, ‘weds his violin each time he plays…’ with a ‘spirit of ardent love’. Yehudi Menuhin, himself one of the great, and fortunately for him, male, violinists of the twentieth century, said that the violin’s shape is ‘inspired by and symbolic of the most beautiful human object, the woman’s body’ and therefore must be played by a master. Menuhin (and he was not alone) was genuinely worried about what happens when a woman plays upon her own body. ‘Does the woman violinist consider the violin more as her own voice than the voice of one she loves? Is there an element of narcissism in the woman’s relation to the violin, and is she, in fact, in a curious way, better matched for

the cello? The handling and playing of a violin is a process of caress and evocation, of drawing out a sound which awaits the hands of the master.’

It’s easy to laugh at this. Or to place it safely in the last century. But just because the sexualisation of the music-making woman takes different forms these days, doesn’t mean it has disappeared. We no longer (openly) subscribe to the view that women’s essential physical and intellectual weakness makes them unfit for purpose, whether conducting an orchestra or creating a large-scale composition, and yet the reality remains that very few women lead major orchestras, and very few large-scale works by women (living or dead) are programmed by our concert halls or radio stations.

Things are changing of course. The New York Philharmonic has Project 19, billed as ‘the largest women-only commissioning initiative in history’. BBC Radio 3 has moved on from bringing women composers out only on International Women’s Day; Classic FM has (delightfully) commissioned two Saturday night series showcasing female composers; Kings Place in London offered a whole year of balanced programming in Venus Unwrapped. Nevertheless, gender inequality is a fact of musical life, a fact of programming. Project 19 is great, but the reality is that, according to an analysis of the 2020 programming of 120 U.S. orchestras by the Institute for Composer Diversity, performances of works by Beethoven alone will exceed those by women composers. We have the data thanks to the tireless work of people like Vick Bain: read her report and weep.

For me, understanding the barriers to creativity in the past allows us to think about the barriers that exist now. It was one of the things that drove me when I was researching my book, Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music. Here’s a checklist of what it takes to be a great composer. First, a sustained education in composition. Usually, the great composer needed a professional position, whether court musician, conservatoire

professor, or Kapellmeister, and the authority, income, and opportunities provided by that position. A great composer required access to the places where music is performed and circulated, whether cathedral, court, printing, or opera house. And most, if not all, had wives, mistresses and muses, to support, stimulate and inspire their great achievements, not to mention deal with the domestic stuff. Obviously, to be born male gave a person a huge head start.

And yet, women persisted. Despite working in cultures which systematically denied them access to advanced education in composition; despite not being able, by virtue of their sex, to take up a professional position, control their own money, publish their own music, enter certain public spaces; and despite having their art reduced to simplistic formulas about male and female music – graceful girls, vigorous intellectual boys – female composers kept writing music. Each woman’s path to creativity was different, but each composer made her choice, and took her chance, whether in the private, female sphere, or – more rarely – in the public, male world. Barbara Strozzi, denied access to Venetian opera (let alone a job at St Mark’s) because of her sex, made sure that she got her work out there through the new media, print. Fanny Hensel, denied the professional, international opportunities seized by her brother, Felix Mendelssohn, created a very special musical salon in Berlin. Lili Boulanger watched and learned from the failure of her older sister, Nadia, to break through the Parisian glass ceiling on talent alone. Lili smashed through it herself by presenting herself in public at least as a fragile child-woman. What is even more inspiring is that many of those women kept writing music despite subscribing to their society’s beliefs as to what they were capable of as a woman, how they should live as a woman and, crucially, what they could (and could not) compose as a woman.

The point that I will never tire of making is that so many women were successful in their own time, but they needed to live and work in communities that actively

enabled them to make music. Those communities were sometimes half-hidden – private salons and convents – and women invariably remained excluded from the big cultural stages, but they existed and were vital to creativity. What is frustrating, looking back, is that even those composers who were successful, prolific, celebrated in their own time were – almost to a woman – at best forgotten, at worst dismissed after their death. Women simply did not have access to the institutions which manufacture posterity.

Composeher is a triumphant counter-blast to that great forgetting – creating not just a community, but a platform for music created by women, here and now, and for the future.

Dr Anna Beer is a cultural historian and biographer.

Dr Anna Beer

Brìdghe

composed by Pippa Murphy, lyrics by Karine Polwart

The Alphabet of Jasmine

composed by Dee Isaacs, lyrics by Gerda Stevenson

Within The Living Eye

composed by Rebecca Rowe, lyrics by Kathleen Raine

The Wilderness, At The Waterfall, Strange Evening, Childhood Memory, Spell of Creation and Say All Is Illusion from Kathleen Raine Collected Poems, Faber 2019.

Angel of the Battlefield

composed by Cecilia McDowall, lyrics by Clara Barton and Seán Street

Interval of 20 minutes

Papilionum

composed by Sarah Rimkus, lyrics by Maria Sibylla Merian

Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium by Maria Sibylla Merian, from Maria Sibylla Merian Facsimile published by Lannoo Publishing and the National Library of The Netherlands.

14 Weeks

composed by Jane Stanley, lyrics by Judith Bishop

Original poem from Judith Bishop’s Interval, published by UQP 2018.

Margaret’s Moon

composed by Ailie Robertson, lyrics by Jackie Kay

Margaret’s Moon from BANTAM. Copyright © 2017, Jackie Kay. All rights reserved.

Programme

Brìdghe

Brìdghe is a celebration of the legend and lore of St Brigid and her pre-Christian counterpart, the Celtic goddess, Brigid or Brìdghe. Brigid is associated with healing, protection, blacksmiths, poets, midwives, divination and livestock. Her Christian feast day is celebrated on February 1st, which coincides with the ancient traditional Celtic festival of Imbolc, the first day of spring and the season when the ewes came into milk. Those seeking her blessings asked for healing and protection, and Brigid was said to visit homes on the eve of Imbolc. Traditional rituals would include the smooring, or raking of the fireplace ashes to keep the fire overnight. People would make a bed for Brigid, leave her food and drink, and set items of clothing outside for her to bless. A cross made of grass was hung over doorways.

Brigid represented the light half of the year and the power that will bring people from the dark season of winter into spring. She brought light and hope. Today, St Brigid’s Day and Imbolc are observed by both Christians and non-Christians. In 2023, St Brigid’s Day became a national holiday in Ireland for the first time.

by Pippa Murphy

The Alphabet of Jasmine

The Alphabet of Jasmine came about through conversations with my great friend and collaborator, writer Gerda Stevenson. Gerda and I have a long history of working together. Since 2015 we have been working independently – me in Greece, with children living in protracted displacement and Gerda here in Scotland at the Scottish Refugee Council, researching for a radio drama she was then writing about asylum seekers and refugees. In both situations, people want to share their journey. These people, young and old, are cast adrift from tradition and security. Gerda writes that The Alphabet of Jasmine is ‘a triptych – in tribute to the Syrian poet, Nizar Qabbani, who died in London, but asked to be buried in Damascus. He said Damascus was “the womb that taught me poetry, taught me creativity and granted me the Alphabet of Jasmine”.’

The first song is called Nine Fathoms Deep – it is for the children who lost lives in the Mediterranean.

The second is The Alphabet of Jasmine. In it you will hear the Arabic refrain meaning ‘Alphabet of Jasmine’.

And finally, The Baker of Idlib – a blessing.

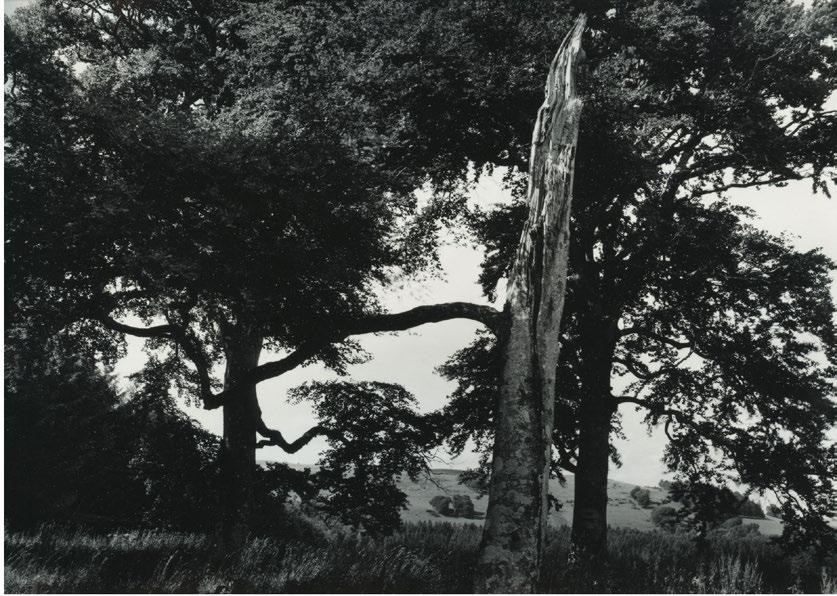

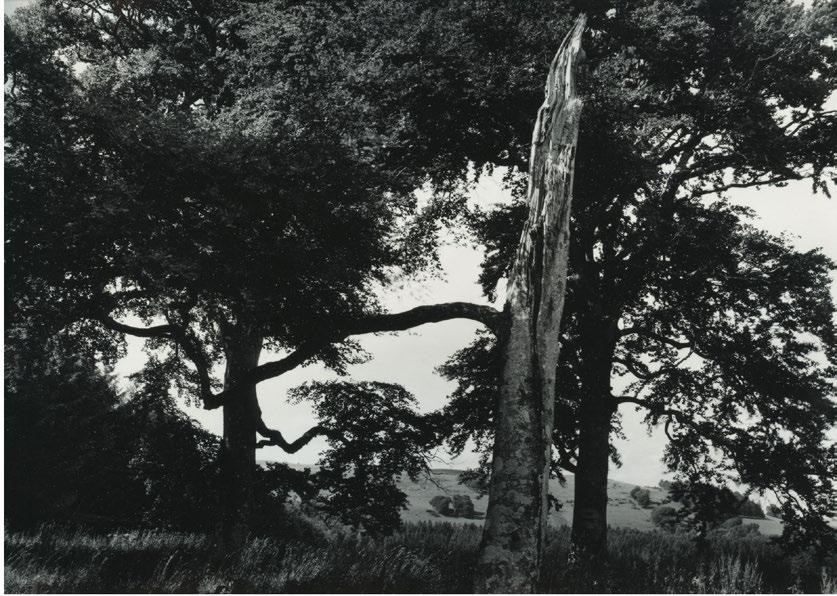

St. Bride, patron saint of the locality, Harleyholm, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

Photograph by Thomas Joshua Cooper, 2019.

The Alphabet of Jasmine is a prayer for people living in limbo. Unable either to go forward or back, they must make their world where they find it, and quest for a better life – testament both to human frailty and human resilience. It is dedicated to Matina and Spiros Katsiveli who have devoted all their lives to supporting refugees arriving by boat on the small island of Leros in the Dodecanese, Greece.

It has been an absolute privilege to have composed this for the Glasgow School of Art Choir.

by Dee Isaacs

Within The Living Eye

The poet Kathleen Raine (1908 – 2003) was drawn to the landscape of Northumberland and the Lake District. Her first collection, Stone and Flower (1943), was published with illustrations by her friend, Barbara Hepworth. Her large collection of poetry spans the decades from the 1940s until shortly before her death in 2000. A lot of Raine’s poetry approaches the ‘sacred’ through art, reflecting on various theologies, Indian spirituality, Buddhist philosophy and that of Jung and Plato.

Kathleen read Psychology and Natural Sciences at Cambridge. She believed God could be revealed in our landscape and in nature, and sought a spiritual, poetic life, rather than the ‘falsehoods’ of materialism and secular frivolities. She saw the imagination, the heart, humanity and the natural world as being the most precious aspects of life.

Raine’s meditative and lyrical poems belong to the tradition of William Blake, on whose work she wrote. Often seen as a prophet and visionary poet herself, her work explored the intersection of science and mysticism and has today even been described as ‘eco-poetry’.

The composer is grateful to Faber Publishing for permission to use these

texts, from Kathleen Raine Collected Poems (Faber 2019).

Background to the composition

I have long been fascinated and captivated by Raine’s world-view and poetic craft.

The song-cycle Within The Living Eye is a ‘love-song’ to her remarkable poetry. Sharing her outlook, I strived to reflect Raine’s belief in the power of our landscape and our relationship with it, and with all living things. Her precise observation, evocative language and deftness with vocabulary have a visual immediacy and power that I always found irresistible, and with enormous potential for musical expression.

It is a curious and poignant thing that, between the piece being commissioned and its completion in May 2020, the global coronavirus pandemic took over and changed our world as we knew it.

Raine’s themes of reverence for, and communion with, our earth, and a fervent desire to protect it, seemed to acquire a deeper significance during that first lockdown, when we saw fewer cars and aircraft, heard birdsong more clearly and found a deeper appreciation for our gardens and woodlands. Long may that prevail, for both our mental wellbeing and the survival of our natural world.

The composing of the piece and working with this text at that strange time became even more meaningful, and I thought continually of the wonderful creative community of this special choir, and how the words and music would hopefully resonate with them too.

On the music

Wishing to have the chance to explore these remarkable words and sentiments further, and to share them with the wider audience they deserve, I selected six of Raine’s poems chosen from volumes spanning five decades of her career for the choral song-

cycle, Within The Living Eye, commissioned by the GSA Choir in 2019.

The poems were selected, ordered, and movements composed to build a narrative structure which leads the listener through themes of loss, yearning for knowledge, love, the divine presence in nature and the responsibility of humankind towards our world.

The movements are brought together coherently through a shared harmonic soundworld, narrative functions of rhythmic drive, melodic motifs which are present throughout, use of intervallic relationships and pacing, using voices separately and in harmony.

Within The Living Eye

I – The Wilderness (from The Hollow Hill, 1964)

The song-cycle opens with a mysterious, bleak and sombre tone.

There is a distinct desolation and emptiness, a feeling of grief at something lost, yet a determined yearning for those hills. A key theme of Raine’s work and this piece; the hills, the land, represent knowledge.

A swaying, uneasy pulse endures. Rising ‘Scotch snap’ figures (short note paired with longer note) emphasise a striving throughout. Brooding harmonies and sweeping lines are shared between the parts (upper voices depicting springs ebbing away through mournful falling lines) but it is the basses who express the most heartfelt line, rising, optimistic.

Bare open fifths portray the majesty of the ancient land with a section of alto plainchant (harking back to my Agnus Dei, The People’s Mass, 2002).

This opening poem outlines so clearly many of the things treasured by Raine; the power and optimism of nature, urging the reader / listener to notice, understand and want to preserve…

At the close, the voices converge on a rich cluster chord with a striving towards understanding: the ‘inexhaustible hidden fountain.’

II – At The Waterfall (from Stone and Flower, 1943)

Whilst the relentless yearning is not yet resolved, there is a calmer more static feel here. This could be Aira Force, near Place Fell, overlooking Patterdale in the corner reaches of Ullswater in the Lake District, close to where Raine lived.

A higher, more translucent texture in sopranos and altos represents the clear water. Pure, open fifths bring a sense of light and stillness. The peace is interrupted by the noise of wind, in onomatopoeic effects and rhythmic trill-like features.

The protagonist longs to hear the wind and water, to feel alive and at one with the landscape and its elemental forces.

III – Strange Evening

(from Stone and Flower, 1943)

Warmer colours are introduced, ushering in a loving sentiment. The protagonist revels in the simple beauty of a sunny evening walk through a field of ox-eye daisies. The immediacy of the imagery inspires a pure love-song to the land.

The melody is deliberately lush and passionate with a rhythmic lilting in five beats in a bar. We are now firmly in a major key; added intervals of seconds in the chordal accompaniment bringing a close, rich harmony. All voice parts have a share in the lead melody, which is earnest and passionate. The closing line, ‘the blue unbounded of the living eye’, yielded, in part, the title of this song-cycle.

IV – Childhood Memory

(from The Hollow Hill, 1964)

The bright optimism continues in a new texture: two characters in dialogue, with sopranos (occasionally joined by altos)

in conversation with the lower voices. A resolute D major melody with strong leaping intervals captures the innocence and open-mindedness of youth. This contrasts with the discordant cynicism of the answering voice in lower voices. A dismissive adult? The child, now grownup, looking back on that innocence and now bitterly realising the fragility of our ecology? Rich harmonies and an aleatoric passage (notes randomly selected by singers from a given selection) paint a vivid aural image of whirling stars and constellations.

The bitter warning prevails to close the movement in a serious mood: ‘chasms of inhuman darkness veiled.’ What can be done to preserve what is dear to us?

V – Spell Of Creation

(from The Year One, 1952)

There is a hushed, whispered urgency, a quietly forceful rhythmic impetus, driving relentlessly onwards as the protagonist is determined to highlight so many precious natural jewels. Here, there is slight deviation from the text, to set up a rhythmic gesture which begins the whirlwind of images.

Raine’s incredible poem, a heady concoction of brilliantly vibrant images, a kaleidoscopic, telescopic journey through our natural surroundings, was a thrilling text to set.

Pitch intervals open in and out as the richness of treasures is revealed. The heart of the song-cycle; melody and harmony reach their impassioned climax in the setting of key images: love, grief, the bird of gold, sun, fire, sky before taking off again as it begun, a relentless reminder of our plethora of precious natural lifeforms.

VI – Say All Is Illusion

(from The Presence, 1987)

For the final movement, thematic strands are drawn together as unison voices summarise and make their conclusion on what has preceded.

Has the living eye, witness to all nature and feeling learned and understood?

by Rebecca Rowe

Angel of the Battlefield

Angel of the Battlefield is inspired by the outstanding work of the pioneering American nurse and founder of the American Red Cross, Clara Barton, and, had the pandemic not intervened, the work would have received its first performance in 2021, the year of the bi-centenary of her birth. Clara Barton, by all accounts, was a rather redoubtable woman who achieved so much in her lifetime and, it seems, all in spite of male obstructiveness. Self-taught in nursing care she worked as a hospital nurse in the American Civil War. Her humanitarian outlook on life and advocacy for civil rights was far in advance of her time. The poet and broadcaster, Seán Street, has drawn on her letters, diary and poetry to give immediacy to the situation she immersed herself in.

As I was writing the first movement of this a cappella work news of the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis came through in May 2020. It seemed a most natural impulse to respond in some way to this atrocity. Angel of the Battlefield is based, fundamentally, on the concept of healing so I felt the spiritual, There is a balm in Gilead, would sit comfortably in this context. But I have subsequently felt the need to justify its inclusion; that this was no act of cultural appropriation on my part. There are connections in this country with the Wesleyan tradition regarding the genesis of this spiritual and the text is largely shared with the Afro-American community of the mid-19th century so I feel America and our country can each lay claim to its provenance. There is a balm in Gilead is a simple arrangement embedded into the close of the first movement. The text of this movement is a fusion between Seán Street’s poetry and Clara Barton’s writings and gives some insight into the horrors of the American Civil War.

The second movement, one of reflection, brings a softer touch to the work, a spelling out of what one needs to be an ‘angel’ in times of war: ‘I never realised until that day how little a human being could be grateful for.’ Clara’s approach to healing, to caring for the wounded, was more about keeping her own thoughts at bay and focusing on the ‘need’ of those in difficulties. So, as an ‘angel’, bread and water were the key to helping the wounded and she seems always to have been able to offer help when it was so keenly needed. As a movement, despite Seán’s beautifully crafted separate voicing, I see the whole movement as Clara’s expression of what she felt, morally, was the right thing to do in time of war. The rather monotone passages I hope will convey Clara’s resolve in ‘doing the right thing’ by her wounded soldiers. But perhaps one could think of it in another way…that there are two strands to this; a softer overall assessment of the situation in her mind and an inner voice (Clara’s words in italics) pushing, with great purpose, to achieve the best outcome for her soldiers in the field hospital.

The final movement details the horror of war in a breathless choral response: ‘To follow the sound of the guns along blood road. The Fires of Fredericksburg still blaze before my eyes.’

After the American Civil War Clara Barton realised that the War Department seemed incapable of dealing with the thousands of letters from distraught relatives asking for the whereabouts of their missing soldiers who were being buried in unmarked graves. So, she wrote to President Lincoln to ‘respectfully solicit your authority and endorsement, to allow me to act (temporarily) as General Correspondent, having in view the reception & answering of letters from the friends of our prisoners . . . and furnish all possible information in regard to those who have died’. She was granted permission to begin ‘The Search for the Missing Men’. Before this time there had been no protocol in place to address these important and poignant issues.

by Cecilia McDowall

Clara Barton.

Photograph by Mathew B Brady, 1865.

by Cecilia McDowall

Clara Barton.

Photograph by Mathew B Brady, 1865.

Papilionum

The transformational processes of insects have fascinated many artists and scientists for centuries. Maria Sibylla Merian, one of the most influential naturalists of the early eighteenth century, was one such scholar. Merian cultivated caterpillars and butterflies from a young age and throughout her rich professional life, studying their habits and recording the changes to their bodies over time. Caterpillars have a voracious appetite, and she tirelessly fed them foliage from the plants on which she found them, studying the symbiotic relationships between insects and plants throughout that process. To document her work, not only did she record her findings in writing, but she produced detailed copperplate illustrations in vibrant colour.

In the early eighteenth century, she travelled to Suriname for two years to document the insect life of South America, producing her ‘magnum opus’ book, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. In celebration of her life and work, this piece sets excerpts from her vibrant descriptions of the flora and fauna she studied there. While insects were her main focus, each illustration features a central plant, and most of her written descriptions begin by detailing the plant on which the insects in question lived and fed. Her studies of these communities of organisms were paramount to her work. This piece illustrates the transformation of these living things in several miniature movements, with a focus on the importance of communal relationships to this growth and change.

‘Papilionum’ means ‘butterflies’ in Latin, in homage to the scientific title of Merian’s book.

by Sarah Rimkus

14

Weeks

14 Weeks sets a text by Australian poet, Judith Bishop. Her poem reflects upon the experience of the early stages of pregnancy,

written from the point of view of a motherto-be speaking to her developing baby.

By the time I found this poem I had already composed some melodic material. The challenge for me while I was searching for poetry was to find a text that fitted the rhythm and contour of my melody. I was also motivated to set a text that explored a strong female perspective.

A key idea that I explore musically, resonating with the text, is the concept of growth. I seek to do this particularly in terms of texture and form. Commencing from the point of a single note, voices gradually enter into the texture independently, women first, followed by men, repeating words and phrases derived from the poem (eg. ‘when you began’). The intention in doing this was to evoke the idea of fragility and vulnerability, but also the rapid and complex division of biological cells that are inherent to the growth of a foetus in utero. I also sought to create something that sounds resonant and immersive. To achieve this I drew significantly on elements of tonality, harnessing the resonance of consonant triads and familiar scale patterns from major and minor scales. Underpinning passages of unfolding organic growth is an element of tension which is produced through drone-like pedals sung by tenor and bass voices. Another feature is the superimposition of textures. The independent free repetition of short phrases is overlaid on voices singing together in rhythmic alignment, acknowledging the idea of an emergent, complex whole human being.

by Jane Stanley Margaret’s

Moon

It is an unusual luxury to receive a vocal commission where the choice of text is left open to the composer. I knew from the start, particularly given the nature of the Composeher remit, that I wanted to use text from a female writer and preferably a Scottish one, so I spent several days trawling through the Scottish Poetry Library

resources.

I stumbled upon the poem Margaret’s Moon by Jackie Kay and, as soon as I read it, I couldn’t get it out of my head. It’s an incredibly beautiful poem, full of vivid imagery, which creates a sound world subtle enough to juxtapose ‘regret’ with ‘Margaret’. Whilst I was immediately sure I wanted to set the work in some way, I had some reservations about whether this would be the right project for it. The poem is so intensely personal, and therefore I hesitated about whether a choral setting would be the right way to honour the text. I realised, however, that the reason I am drawn to the topics I choose to write about is almost always this juxtaposition of the personal and the universal. Whilst the text is intensely personal, the theme of complicated grief is shared by many. I think there is, therefore, something potentially very powerful about performing such an individual text with such a large number of people. In some ways, perhaps, it acknowledges that in the moments when we feel most alone, we never truly are.

by Ailie Robertson

Metamorphosis of a Butterfly. Copper engraving print by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1705.

Metamorphosis of a Butterfly. Copper engraving print by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1705.

Pippa Murphy

Pippa Murphy is an award winning Scottish composer and sound designer who writes for theatre, dance, film, choirs and orchestras.

Pippa is known for her stylistic breadth, depth, and originality, as well as a unique crossdisciplinary understanding of storytelling and creative collaboration.

Pippa’s works are multi-layered and multi-sensory. Some pieces draw on the full effects of combining sound design with orchestral instruments and voices. Her music has an immediacy, which is often dramatic and expressive. She is particularly interested in vocal techniques, phonemes and ‘found’ sound.

She has written music for BBC2, BBC Radio 4, BBC Radio 3, Scottish Opera, Edinburgh’s Hogmanay, Edinburgh International Book Festival, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, St Magnus International Festival, and numerous theatre companies including The Royal Lyceum Edinburgh, Stellar Quines, Dundee Rep, Birmingham Rep, Grid Iron, Tron Theatre, Eden Court, Traverse Theatre and 7:84.

She composed Anamchara with writer Alexander McCall Smith, which was performed by Scottish Opera as part of the Commonwealth Games 2014. Recent projects include orchestral arrangements for Celtic Connections with Karine Polwart, Julie Fowlis and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and original songs for POP-UP Duets with Janis Claxton Dance Company, now on international tour.

She won the CATS Award 2017 for Best Music and Sound for Wind Resistance and her album with Karine Polwart, Pocket of Wind Resistance, was nominated for best album at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards.

Pippa was classically trained on piano, violin and percussion from an early age. She completed her BMus, MA and PhD in composition at the University of Birmingham. She lectures at the University of Edinburgh and guest lectures at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, the University of Aberdeen and the University of St Andrews.

She was Artist in Residence at the Scottish Parliament 2014.

Dee Isaacs

Dee Isaacs is Senior Lecturer in Music in the Community at the University of Edinburgh. She studied composition with Professor Nigel Osborne.

She is passionate about the creation of music and its power to engender community.

She has been commissioned by a wide range of professional arts bodies including Opera North, London Symphony Orchestra, Northern Sinfonia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Scottish Ballet, Magnetic North, Scottish Ensemble, Live Music Now, The Scottish Executive and Creative Scotland, Dumbworld, and the Wellcome Trust.

In 2003, 2006 and 2018 she was nominated for a British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors (now The Ivors Academy) awards for Festus, Suppose Life and Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In 2012 she was awarded the Principal’s Medal by the University of Edinburgh for her work in music education and outreach. She has worked for War Child as UK Coordinator for War Child in the Caucasus, working with refugee communities and psychologists using music specifically to help children suffering from trauma.

Dee continues to work across cultures and within marginalised communities both near and far. She set up a long term research project for primary aged children using immersive arts projects to improve literacy and language development in the Gambia, West Africa.

Since 2016 her focus has been on working with children living in challenging circumstances as refugees. Windows on the World is the creative arts programme she now runs in collaboration with SolidarityNow in Greece.

Rebecca Rowe

Rebecca Rowe is passionate about bringing contemporary music to audiences in an exciting, challenging, meaningful and accessible way. She is interested in interdisciplinary collaborations with artists, film-makers and writers.

Rebecca has composed soundtracks for animated film / theatre, and has worked collaboratively with directors / poets.

Commissions, performances and CD releases include: The Dunedin Consort, Cappella Nova, The Hilliard Ensemble, CHROMA, recorder virtuoso John Turner, ONE VOICE and The Allegri String Quartet.

Rebecca is a cellist and pianist with an MMus degree in Composition. A founder of The Squair Mile Consort of Viols, she was Artistic Director / conductor of Edinburgh University Contemporary Music Ensemble.

A skilled interpreter of contemporary music, she has conducted chamber orchestras, ensembles and large choirs, children’s school choirs and University ensembles.

Her work has been broadcast on BBC Radio Scotland, BBC Radio 3 and The World Service. Films scored have been broadcast on STV / BBC1.

A winner of The English Poetry and Song Society Prize, Rebecca has been a panelmember at StAnza (St. Andrews’ Poetry Festival), in an illuminating debate on Words and Music.

Rebecca’s Three Pieces for Soprano and Clarinet included texts commissioned from prominent Scottish poets. It premiered at the SOUND Festival in 2015 and was performed at the innovative series The Night With… It received its CD release in 2023 and was broadcast on BBC Radio Scotland.

Her work, About The Cauldron Sing, a setting of the Witches’ scenes from Macbeth, premiered in 2019.

Rebecca is currently returning to a lifelong passion for film music, in composing some miniatures reflecting a series of filmic themes.

Rebecca is delighted to have had the opportunity to compose for, and meet, members of the Glasgow School of Art Choir as part of their ground-breaking Composeher project.

Cecilia McDowall

Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951) is one of the UK’s leading composers of sacred and secular choral music. Her most characteristic works fuse fluent melodic lines with occasional dissonant harmonies and rhythmic exuberance. Her music has been commissioned and performed by such organisations as the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and Chorus, City of London Sinfonia, London Mozart Players, St Paul’s Cathedral, leading choirs, including the BBC Singers, The Sixteen, Oxford and Cambridge choirs, Kansas City Chorale and at festivals worldwide.

Three Latin Motets was recorded by the renowned American choir, Phoenix Chorale, conductor, Charles Bruffy; the Chandos recording, Spotless Rose, won a Grammy award and was nominated for Best Classical Album. The National Children’s Choir of Great Britain commissioned a work focusing on ‘children in conflict’, called Everyday Wonders: The Girl from Aleppo. The cantata is based on the real-life escape of the wheelchair-bound Nujeen Mustafa and her sister from war-torn Aleppo; it tells of their harrowing journey across 3,500 miles, through eight countries, to Germany in 2014. In May, 2019, Wimbledon Choral Society and the Philharmonia Orchestra premiered McDowall’s large-scale choral work, the Da Vinci Requiem, to coincide with the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death. The work received its first performance on 7 May in the Royal Festival Hall, London, and in 2023 was released on Signum.

In 2020 McDowall was presented with the prestigious Ivor Novello Award for a ‘consistently excellent body of work’. This was a ‘gift’ from The Ivors Academy. Many of her works have been recorded, most recently a CD of her choral music by the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, on the Hyperion label in 2021. Also, in 2021, McDowall was given the coveted annual commission by King’s College, Cambridge, to write the carol for the Choir of King’s College and their music director, Daniel Hyde, to be part of the much-loved Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols broadcast world-wide on Christmas Eve. The carol, There is no rose, is published by Oxford University Press.

In 2022 The Sixteen commissioned a work for choir and harp, O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth, our Queen, premiered as a tribute to the life and reign of Elizabeth II in the Chapel Royal, Tower of London. Earlier in 2022 McDowall’s Jubilate Deo, commissioned and premiered by St Michael and All Angels, Dallas, was given the UK premiere on the Queen’s Jubilee, 3 June, at St George’s Chapel, Windsor.

McDowall holds two honorary doctorates (University of Portsmouth and University of West London) and in 2017 McDowall was selected for an Honorary Fellow award by the Royal School of Church Music.

Sarah Rimkus

Sarah Rimkus is an award-winning American composer of choral, vocal and chamber works. She brings a wide range of influences to her music, from ars antiqua and ars nova polyphony to Balkan and Scandinavian folk traditions and many other sources, and her work often explores issues such as communication, belonging, and conflict, through the use of contemporary themes and musical layering and contradiction. Her music has been described as ‘challenging yet attractive’, ‘always powerful and well-judged’, and ‘ranging from uncluttered lyrical poignancy to denser textures that suggest a holy clamor’.

Dr. Rimkus’s choral works have been performed extensively across the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe. Recent commissions include works for Amuse Singers, Harmonium Choral Society, and the Cambridge Chorale. Many of her works take inspiration from the British sacred choral tradition, including a mass setting in Latin and Scottish Gaelic premiered by the Cathedral Choir of St Andrews (Aberdeen) in 2017. She often compiles and edits her own texts and writes on important historical or contemporary events and themes. Her recent piece for The Esoterics, entitled Uprooted, set the words of two survivors of the Japanese exclusion during World War II, a deep part of the history of her Pacific Northwest home. Her works have been featured on BBC Radio 3 and Classic FM and professionally recorded by ensembles on both sides of the Atlantic. She has publications with GIA Publications, Walton Music, and See-a-Dot Publications, and selfpublishes many of her scores.

She also has a strong interest in chamber works and the intimate communication of individual players in this medium. She has recently completed commissions for Red Note Ensemble and the Ligeti Quartet, commissioned by the Sound Festival and the Cheltenham Music Festival. Her choral works strongly inform her instrumental works and vice versa, particularly in her writing for the highly vocal and expressive family of string instruments. Her string orchestra piece Trapped in Amber, inspired by Kurt Vonnegut and Slaughterhouse-Five, was selected for performance by the USC Thornton Symphony in 2013 and awarded the ASCAP Morton Gould Award. She has also written works for acclaimed soprano and artist Jillian Bain Christie and British organist Roger Williams MBE.

Dr. Rimkus recently completed her PhD in music composition at the University of Aberdeen with Phillip Cooke and Paul Mealor, after completing her MM in composition with distinction at the University of Aberdeen in 2015. She earned her BM in composition magna cum laude in 2013 at the University of Southern California, where she studied with Morten Lauridsen and Stephen Hartke. She has been internationally recognised through awards such as the ASCAP Foundation Leonard Bernstein Award, the Sacra / Profana Composition Award, and many others.

Jane Stanley

Jane Stanley is a UK-based, Australian-born composer. She specialises in composing for live performers.

Her music has been performed, recorded and broadcast throughout the world and featured at festivals including Tanglewood, ISCM World Music Days, and Gaudeamus Music Week.

She received her PhD from the University of Sydney and in 2004-5 she was a Visiting Fellow at Harvard University.

In 2015 her piece Pentimenti for piano duo represented Australia at ISCM World Music Days in Wrocław, performed by the Lutoslawski Piano Duo. A highlight of 2017 was the premiere in Sydney of her Piano Sonata, commissioned by Bernadette Harvey and supported by a grant from the Australia Council for the Arts.

Jane is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow and, as part of this role, she engages in practice research as a composer. She is founder of the Scottish Young Composers Mentoring Project, a year-long programme that provides university students with experience in mentoring secondary school-age people in composition. She is a founding member of the Young Academy of Scotland, a represented composer at the Australian Music Centre, and her music is also published by Composers Edition and the Scottish Music Centre.

Ailie Robertson

Ailie is a multi-award winning composer, performer and educator based on the West coast of Scotland.

She has been commissioned by some of the world’s most prestigious cultural institutions including the BBC Proms, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Scottish Ensemble, Bang on a Can, Red Note Ensemble, Cappella Nova, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival and the Riot Ensemble.

She was composer-in-residence with Sound Festival and Glyndebourne Opera, for whom she wrote a new Youth Opera which was awarded ‘Best Opera’ in the YAM Awards 2022. She was awarded the inaugural ‘Achievement in New Music’ prize at the Scottish Awards for New Music.

Her compositions range from concert music to film and theatre scores and her innovative work, which crosses the boundaries of contemporary classical and traditional folk music, has been performed globally.

Jamie Sansbury

Jamie founded the Glasgow School of Art Choir in 2012, during his third year at The Glasgow School of Art. He did so with the firm belief that anyone can sing in a high quality ensemble, regardless of musical training and their individual quality of voice, and one of the principal aims of the ensemble is to encourage outstanding musical discipline within a non-auditioned, amateur chorus. The ensemble is now an established champion of contemporary music having commissioned work from Ken Johnston, Shona Mackay, Jay Capperauld, Sir James MacMillan, Thomas LaVoy and others.

Jamie has been performing with choirs and choruses since he was 8 years old as a member of the National Youth Choir of Scotland (NYCoS) Edinburgh Area Choir, NYCoS National Boys Choir, NYCoS and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra Chorus.

In addition to his role as Musical Director, Jamie is Chair of the ensemble’s Board of Trustees.

Dr Anna Beer

Dr Anna Beer is a cultural historian and biographer.

She is author of Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music, as well as biographies of William Shakespeare, John Milton, Bess Throckmorton, and her more famous husband, Sir Walter Ralegh. Her most recent book is Eve Bites Back: An Alternative History of English Literature, which comes out in paperback later this year.

She is a Visiting Fellow at Kellogg College, University of Oxford.

by Cecilia McDowall

Clara Barton.

Photograph by Mathew B Brady, 1865.

by Cecilia McDowall

Clara Barton.

Photograph by Mathew B Brady, 1865.

Metamorphosis of a Butterfly. Copper engraving print by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1705.

Metamorphosis of a Butterfly. Copper engraving print by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1705.