CONTENTS

Cover Art

Gaiaby Karina Stakh | The Lawrenceville School, NJ

Letter from the Editor by Zixuan (Angel) Xin | The Lawrenceville School, NJ

Essays

Narcissus: A Queer Reflection by Riley Casey | Durhan Academy, NC

Seeing Color in the Ancient World by Erin Li | The Taft School, CT

Euripides’s Medea: Reclaiming the Power of Perspective in Greco-Roman Mythology by Anonymous Submitter

Piety and Propaganda: How Myths Build Empires by Leon Zheng | Princeton Day School, NJ

Echoes of Empire: How Classics Shapes Contemporary Politics by Angel Yu | St. George’s School, RI

Conscience Against the Crown by Stella Liao | The Hotchkiss School, CT

Numidia by Aurelia Zhang | Philips Andover Academy, MA

What Cunctans Reveals about Fata, Pietas, and Pudor by Clementine

Sutter | Dartmouth College, NH

Graphics Contributers

Teri Kim | The Lawrenceville School, NJ & Seoul, Korea

Bella Wu| The Lawrenceville School, NJ

Eleanor Wang | The Lawrenceville School, NJ

With Special Thanks to Latin Wordle Student Ambassadors Program

Letter from the Editor

Lectores carissimi,

At the age of four, I knew Julius Caesar was a man of honor. His name echoed from the dinner tables to my bedroom, where my father regaled me with the very stories that brought him to manhood: bedtime tales of Roman generals. Naturally, I inherited my father’s reverence. Caesar expanded Rome’s geographical boundaries and deepened its legacy. I carved his famous saying— aut viam inveniam aut faciam, “I shall either find a way or make one” —into my mind. At Lawrenceville I decided to start studying Latin, to the surprise of many of my friends. Unlike Spanish and French, with 560 and 312 million total speakers respectively, Latin is considered a “dead language. ” The steady decline of students pursuing majors in Classics also directly reflects the “deadness” we see in ancient languages: The annual number of undergraduates graduating with a Classics degree fell from 1,200 in 2013 to 736 in 2020, according to Times Higher Education. Moreover, many schools are dissolving their Classics departments, like Howard University, which did so in 2021. Despite exterior skepticism, I adhered to my passion.

My respect for Roman generals greatly diminished, however, when I read Caesar’s commentaries on De Bello Gallico in Latin III. The pair of rosetinted glasses I never dared to take off

shattered when Caesar stated “ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur,” referring to the Celtic people as the “Gaulians.” Caesar rejects the chosen name of the tribe in a pejorative way. Yet, Casear’s quip persists to this day in history textbooks that refer to the Celtic people as the Gauls. As such, Caesar’s account of the Gallic Wars should not be cited as empirical evidence of the wars themselves but rather a Eurocentric retelling of history. But this is just one of the instances where the discipline of Classics led to a legacy of historic exclusivity and racism.

More troubling is the Roman militaristic philosophy Bealum Romanum, the laws of war, which outlines the ruthless warfare the Romans practiced against “barbarians.” Today, we call warfare like this genocide. How should Classics evolve as a discipline under modern concepts of morality? I believe that more people of minority groups should critically examine the horrific acts and consequences of the Roman empire, with an emphasis on bettering our society rather than glorifying their misdeeds.

The Romans demanded the Belgians, Helvetians, and Aquitanians to “surrender and accept subjugation without rebellion,” as told by Dan Carlin in Hardcore History. Caesar’s army committed mass murder, sold people into slavery, and ripped apart the cities he passed, eerily echoing how Fascist regimes treated minorities before the Second World War. While the Nazis are rightly condemned, the Romans have often been celebrated as the pinnacle of classical civilization. Despite its pervasive racist ideology and sexist propaganda, the Roman Republic has been lauded as a symbol of democracy in previous decades. Our society’s definition of what is right has evolved

from the viewpoint of the winning side to an examination of the moral consequences of both parties in the persisting conflicts. Classics’ decline may seem unproblematic. However, removing it may do more harm than good. The absence of minority representation in the classical field allows classics’ skewed legacy to persist: According to Max L. Goldman, a Denison University professor, a 2014 survey reveals that “the number of nonwhite faculty in the discipline was so small that a breakout analysis was impossible since it would undermine the anonymity of survey participants of color.” Simply put, the Classics field is far from welcoming minorities who suppress any hint of diversity within their academic ranks or any ideological diversity within classical scholarship. Are you going to add analysis after this quote, or do you think it speaks for itself?

For Classics to stay a worthwhile endeavor, the field must adapt to modern standards of scholarship. In February 2021, UNESCO stressed the importance of learning “to study, inquire, and co-construct together, to collectively mobilize,” “to live in a common world,” and “to attend and care.” All four standards of education emphasize inclusion rooted in globalization. We must explore how Classics might unify rather than divide. Rather than worshiping Classical works on a pedestal, institutions providing Classics could examine the flaws in Athenian democracy and the Roman Republic. While we certainly should not undermine the achievements of our predecessors, we must remember that those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Without dedicated Classical scholarship that critically examines the flaws in ancient empires, overly romanticized rhetoric will pervade modern thought in our already divided so-

ciety.

Hence, proponents of stripping down Classics programs need to recognize that Classics, as a discipline, is not innately dangerous. When certain social anarchists seek to justify their attempts to initiate ethnic cleansing with Classical literature, using historical sources in such a violent way is dangerous. I believe that no discipline of study is inherently political. Instead, the views, perspectives, and backgrounds of those studying a discipline add interpretative layers to their field of study which politicize a discipline--in the case of The New Criterion’s essay series on “Western Civilization at the Crossroads,” Roger Kimball chose to manipulate Classics into right-wing propaganda. Ultimately, Classics literature is a record of the strength, venerability, and tradition instilled in our past rather than a technical guide to navigate our path towards the future. Adhering to my mission, I initiated project Gaia to repopularize Classics among high school students across the world and to lower the field’s barriers of entry. Ultimately, by encouraging BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students to actively engage with Classics, my team and I hope to dismantle the current limitations in the field. Classics should not be a discipline that propagates the notion that who we were is indicative of who we will and should become; Rather, we must better utilize Classical literature to avoid past mistakes. With that being said, I am incredibly thankful for those who supported me through this process. It had been incredible for me to work with this many likeminded peers. Special thanks to Erin Li for supporting this project at all times!

Cum Amor, Zixuan (Angel) Xin

Narcissus: A Queer Refelction

Riley Casey ’26 Durham Academy, NC

It often seems inevitable that parochialism encroaches on ancient texts. Many scholars claim the world of antiquity to be a conformist, steeped in sacred traditions that deny the existence of subversive identities unaligned with the conventional narrative. This misconception shrouds the clarity and adeptness with which Roman poets discuss critical theories and profound conceptions of the self, particularly those pertaining to notions of gender and sexuality. They celebrate queerness and praise self-expression, making one fact certain: queerness is not a byproduct of the modern world.

Classical literature provides fertile ground for readings of nonnormative sexual identity. Thus,

queer theorists seek to disrupt and dismantle existing social orders that subsume sexuality and gender from a spectrum to a shallow, binary construct, overemphasizing object-choice. Classical prose and poetry demonstrate a surprisingly fluid understanding of sexual attraction and present nuanced perspectives on gender. The Metamorphoses, written by Ovid during his exile in 8AD, is one such text: Through focusing on the transformation of the mortal flesh, the text portrays the human body as an ever changing subject, liquid, and inherently queer.. The text explores both transformations present in Roman and Greek myths and those that sculpted Ovid’s identity. Ovid’s journey was nothing short of tumultuous: his career as a poet and his consequent banishment played a role in his perception of the Augustan regime.. Unlike his

predecessors in epic poetry, Ovid was born into a time of relative stability in Roman history, which prompted him to react to politics with humor.

In the prologue’s exegesis, Ovid claims to trace history from its beginning to the present day, providing insight into how the following stories are to be structured. Flashbacks, flashforwards, and chronological slips encourage each individual story to be read independently. Additionally, in accordance with the theme of metamorphosis, the structure and overall organizational scheme of the poem are subject to alteration; no one book has a particular literary or historical theme. In fact, the various groupings can be created depending on how one approaches the text.

In Metamorphoses, Ovid also betrays his characteristic syntax, opting for dactylic hexameter rather than elegiac couplets. This is particularly interesting, as attempting to tackle such an intricate and sinuous text with an entirely new form of verse is quite an ambitious task. Regardless, Ovid’s choice of form sets the scene for the text’s primary theme of transformation, as we see Ovid’s growth into an entirely new poet embedded in the very com-

“What initially appears as a fable about the dangers of vanity is a discussion of reality, selfidentity, and destruction of in the context of an expression of queer intimacy.”

position of the poem. Numerous episodes within the Metamorphoses exhibit themes of sexuality and gender. Echo and Narcissus, in book III, is not one that usually comes to mind; However, underneath what initially appears as a fable elaborating the dangers of vanity, Narcissus features a discussion of reality, self-identity, and self-destruction to shed light on the expression of queer intimacy. In Narcissus, the love between one and one’s self betrays hetero-

normativity and becomes subsequently, catastrophic; Here, self definition emerges as inherently queer, challenging how we understand identity and prompting us to re-examine what it means to know one’s self.

Narcissus is the son of the river god Cephissus and the nymph Liriope. He is physically captivating, and as a result, attracts herds of suitors; Narcissus himself, however, has never found intimacy, until his gaze fell upon his own reflection within a pool of pristine water, untouched by any man. The episode follows Narcissus’ interaction with the reflection, and his inevitable realization that the image he is seeing is, in fact, himself.

Previous to Narcissus’s journey of self-discovery, the myth detailed an interaction between Tiresias, a famed Greek prophet, and Narcissus’s mother. In which Liriope consulted the prophet on the length of her son’s life, to which Tiresias states that Narcissus will live long and well, so long as he never truly knows himself. Tiresias’ oracle is representative of conventional societal reactions to queer expressions. Even in today’s society, individuals’ identity and modes of self-expression can

still present barriers to their success.

As Narcissus matures, he becomes surrounded by legions of suitors, men and women alike. Narcissus represents an image of beauty that is all encompassing, an image of beauty that knows no bounds, that hypnotizes and mesmerizes anyone fortunate enough to perceive it. However, Ovid very intentionally avoids any actual description of this beauty, which grants Narcissus visual immortality. If his beauty is chronicled to no one, it will remain imperative. This presentation of beauty is inherently queer in the sense that it is explicitly non-heteronormative. Narcissus’s beauty is distinctly gender neutral. We are introduced to Narcissus as an authority on beauty and sexuality. He is a character that is pro-

The narrative Narcissus’s beauty is distinctly gender neutral.

foundly desired by members of both sexes, yet consistently denies their advances, presenting an image of purity and innocence. He revels in their praise, yet considers their amorous gestures far below his own stature. To Narcissus, the act of falling in love represents weakness: “but the heart was so hard and proud in that soft and slender body, that none of the lusty men or languishing girls could approach him” (Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.5.353-354).

The Greeks and Romans understood love as complete and utter devotion – to love is to lose oneself entirely, to relinquish self-preservation to focus on the well-being of another individual. Thus, Narcissus felt that those who had fallen in love with him were inherently inferior, vacuous beings, effectively placing himself above the very concept of passion and endearment, which contrives a particularly flagrant display of Hubris. By undermining the divine idea of eros, Narcissus oversteps his mortal accountability, blurring the lines between the human and the divine. Narcissus assumes the identity of an ‘other,’ of something existing in between two extremes of self. It is the act of sight that leads Narcissus to fall in love; he gazes upon what Plato describes as the

simulacrum, the reflection, and in doing so affirms its subjectivity. Ovid himself refers to the image as fraudulent, empty, and an imagined falsification of an actual substance. Narcissus is overwhelmed by his mortal beauty, his vision evoking an erotic desire for the object. Narcissus, in the way that he is completely absorbed with the simulacrum, creates an entirely new dynamic that opposes many of the cultural standards of Ovid’s time. The perfect reciprocity of Narcissus’ relationship with himself is exempt from any difference in age, experience, or participation, directly challenging the pederastic norms of first century Rome, which maintain that relationships between two men must involve an older, more experienced male and a younger, less mature adolescent. The younger beloved is meant to tolerate, but not reciprocate, the passion of his older lover. Narcissus embodies a sense of chaotic confusion: confusion of actor and agent, confusion of lover and beloved, confusion of self and other, all of which are heavily gendered roles. This confusion, this disruption of established institutions and gendered spaces, is what imbues this story with such a strong sense of queerness.

Looking into the glassy wa-

ter at the boy staring back at him, and watching as he mimics his movements, Narcissus eventually realizes that he is observing his reflection. This dissonance, this impossibility of being both lover and beloved simultaneously, causes Narcissus to collapse; just as wax melts when exposed to strong heat, or frost dissipates when confronted by the sun, so Narcissus fades when revealed to his own body. It is here that we, as an audience, come to understand Narcissus’s fatal flaw: he is only able to love himself, yet he can never actually perceive himself. Every reflection, every image, every projection of himself that he can see is but a simulacrum, a shadow, a fleeting phantom of the true substance. It is only in his death that he comes to understand himself; or rather, he perishes because he comes to understand himself. Narcissus ascertains that, because the object of his desires is simultaneously the subject that directs them, he can never truly love or be loved by another. Thus it becomes apparent that even for Narcissus, a life absent of love is a fate worse than death; what he condemned in others is now what he experiences. He quite literally fades into nothingness, transforming into

the Narcissus flower, a state of existence that, although alive, possesses no consciousness, a state of reality that cannot perceive or be perceived. He also agonizes in the realization that he has caused his lover harm; Narcissus has no problem sacrificing himself for his lover, yet he is also entirely unwilling to injure his beloved, thus creating an interminable paradox. By falling in love, Narcissus, in a way, loses his individuality. He becomes unrecognizable among the faces of those who adore him, the same faces that he once looked so scornfully upon; the knowledge that not only has Narcissus fallen in love, but he was always capable of such love, had he just been able to see himself, to know himself, affirms Narcissus’ humanity and thus causes an inward collapse of identity. Narcissus’s queerness evokes self-denial; In finding himself, Narcissus finds his weakness, intrinsic to feeling. For Narcissus, self-preservation and self-love can not coexist; To love is to be utterly and devoted to another, asserting self-preservation as merely an afterthought.

Seeing Colors in the Ancient World

Erin Li’ 26

The Taft School, CT

For generations, the Western world has clung to a sanitized image of Ancient Greece and Rome, one in which marble statues gleam in pristine whiteness, philosophers and emperors are cast exclusively as white men, and the classical world is deemed to exist solely in modern Europe. This mythologized vision has been repeated in museums, textbooks, Hollywood films, and even academic scholarship. But it presents an inaccurate reflection of antiquity. The classical world blooms in its colors and cultures. Similar to the United States, Rome is a melting pot, thriving on both racial and cultural diversity, sculpted by internal migrations, the exchange of goods, and conquests. To understand the classical civilizations more thoroughly, we must actively

dismantle the whitewashed image that fabricates historical truths. The iconic whiteness of classical statues is one of the most enduring visual lies present in Western culture. When we walk through museums and see rows of stark, white figures, we may assume that the ancients favored pale complexions. In reality, however, the Greeks and Romans painted their sculptures in vivid colors. Traces of paint on statues such as the “Peplos Kore” or the “Augustus of Primaporta” hint that these artworks were once vibrantly hued. Simply because colors may grow dim with time does not give us the right to remove them from our communal, shared memory. Although ancient writers have gone one step further, commenting on the colors used in varying statuaries through prose, generations of European curators

and collectors still stripped these statues of their vibrancy to emphasize the neoclassical ideal of purity.

This transformation was not accidental. During the Enlightenment, Europeans sought to align themselves with a mythic lineage of intellectual superiority and aesthetic perfection. By promoting the idea that the classical world was defined by whiteness and, simultaneously, racial pu-

“The white marbles became more than mere artistic self-expression”

rity, the society sculpted a visual narrative emphasizing empire, racial hierarchy, and exclusion. The white marbles became more than just artistic self-expression; they metamorphosed into a symbol. As classicist Sarah Bond notes, “the equation of white marble with beauty is not an inherent truth of the ancient world but a dangerous modern construct.”

One of the most effective ways to challenge whitewashed narratives is to look at geography. The Romans and Greeks were never isolated. They sat at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and Asia, at times spanning across all three continents. This geographical reality meant that ancient Greece and Rome were sites of immense cultural and racial exchange.

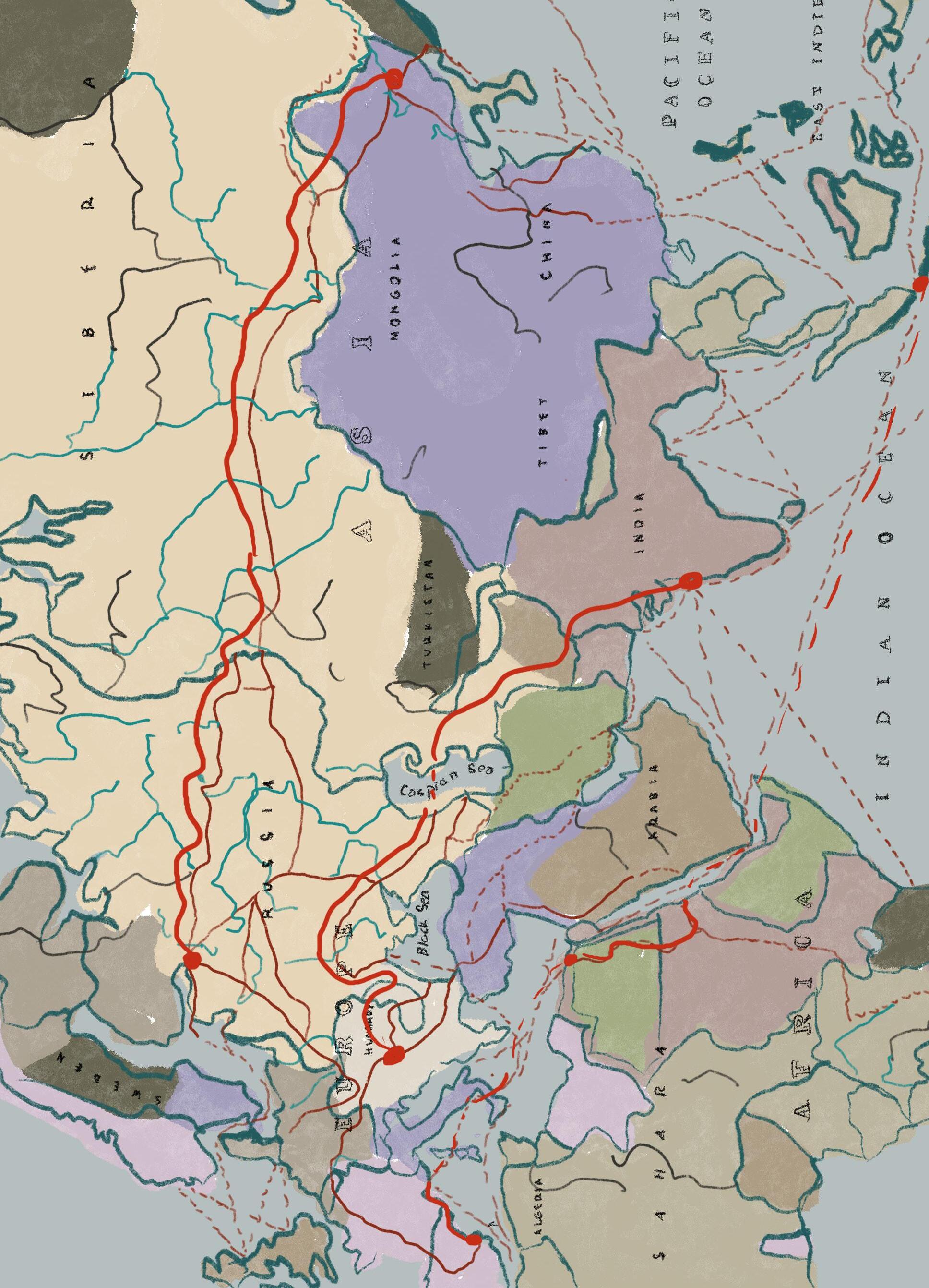

Ancient trade routes tell stories. The Roman Empire maintained robust commercial and diplomatic relationships with Carthage, Nubia, Egypt, and the broader African continent. It extended to Persia and Parthia, reaching, through the Silk Road, India and China. Greek colonies existed not only in the Aegean region but also flourished in modern-day Turkey, Libya, and along the shores of the Black Sea. The port cities of Rome and Alexandria were diverse, filled with traders, immigrants, and enslaved people from all across the known world.

These connections were not merely economic, they were cultural. Egyptian science shaped Greek philosophy; Persian political thought influenced Roman governance; African grain sus-

tained the Roman populace. Black Africans served as soldiers, poets, and even bureaucrats in the em pire. Inscriptions, coins, and artworks attest to the presence of people of color in everyday life and elite circles alike. Ever since humani ty’s origin, we have been connected by ties stronger than that of the color of our skin and the nation of our birth.

further disrupted the myth of a racially ho mogeneous antiquity. Roman frescoes and mosaics depicted peo ple with a wide range of skin tones. One notable example is the mosaic of African wrestlers from a Roman villa in Sicily, por traying Black athletes in detail and with no trace of caricature. Roman artists also depict ed Nubian archers, African priests, and Middle Eastern mer

chants. There were not exoticized anomalies but rather, reflections of the multicultural world the Romans in-

Moreover, individuals of African and Middle Eastern origin held real power in the Roman world. The most famous example is Septimius Severus, a Roman emperor of North African descent who ruled from 193 to 211 CE. Born in Leptis Magna (modern-day Libya), Severus embraced his provincial origins and brought his cultural identity to the imperial court. His wife, Julia Domna, came from a powerful Syrian family that wielded significant political influence. Thankfully, their

portraits, resting in Roman sculptures, survived thousands of wars, witnessing millions of deaths. Yet, the racial and ethical context, lurking beyond their eyes, is often overlooked. Religious and philosophical figures also illustrate this diversity. Plotinus, one of the most influential Neoplatonist philosophers, was born in Roman Egypt. Augustine of Hippo, a Christian theologian, was also from North Africa. Their contributions are rarely framed through the lens of their origins, yet doing so opens the door to a richer and more inclusive understanding of classical intellectual life.

The whitewashing of antiquity is not just a historical inaccuracy, it is a political tool. In the

“The whitewashing of antiquity is not just a historical inaccuracy, it’s a political tool.”

19th and 20th centuries, European and American white supremacists appropriated the image of a white classical past to construct narratives of racial superiority. Classical architecture, symbols, and aesthetics were deployed in colonial buildings, fascist propaganda, and even white nationalist manifestos to lend a false legitimacy to modern racism. This appropriation continues today. Far-right groups use Greco-Roman imagery to promote exclusionary ideologies, arguing that they are defending “Western civilization” against “outside” threats. This imagined West, rooted in a mythical white antiquity, erases the contributions of nonEuropean cultures and distorts the real complexity of the ancient world. In academic spaces, Classics has been criticized for its Eurocentric biases and for being slow to confront its complicity in upholding racial hierarchies. Fortunately, scholars, educators, and students are now working to challenge these misconceptions. A new wave of classicists focuses on examining the urgent, timely, overarching way to redefine Classic. They are reinterpreting texts, recovering marginalized voices, and teaching classi-

cal history in ways that reflect its full diversity.

Graphic representations are key tools in this movement. For instance, a side-by-side visual comparison of ancient art showing people of color next to neoclassical depictions that erase their legacy can be a powerful educational intervention. Similarly, Roman and Greek trade routes highlight connections to Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, reinforcing the truth of a global antiquity. By recentering these truths, we expand the relevance of classical studies beyond a narrow elite.

“By recentering these truths we expand the relevance of classical studies beyond the narrow elite.”

Students of color, especially, benefit from seeing themselves reflected in stories of the past. The ancient world was not homog-

enous, and our study of it should not be either. Diversity, hybridity, and mobility were at the core of ancient life, just as they are today. Deconstructing the whitewashed image of Romans and Greeks is not an attack on history, it is an act of historical fidelity. It requires that we ask difficult questions, examine overlooked evidence, and challenge long-standing assumptions in both scholarship and public understanding. It means looking at marble statues and asking what colors have been scrubbed away. It means teaching students that the Roman Empire included Africa and the Middle East, not as peripheral zones, but as central regions of influence and innovation. It means rejecting the idea that the classical past belongs only to the West.

a doing so, we can reclaim the classical world as a shared human inheritance. We restore richness, contradictions, and truths to antiquity. Most importantly, we open the door to a future in which the study of the past is not a gatekeeping exercise but a bridge. It is a way to understand where we have been and who we all have always been.

Euripides’s Medea: Reclaiming the Power of Perspective

Submitted

Anonymously

- from Euripides, Medea.

“Flow backward to your sources, sacred rivers, And let the world’s great order be reversed. It is the thoughts of men that are deceitful, Their pledges that are loose. Story shall now turn my condition to a fair one Women are paid their due. No more shall evil-sounding fame be theirs.”

- from Euripides, Medea. Translated into English by Philip Vellacott.

Traditionally, Greco-Roman myths have always been told through the “male” perspective. These tales typically follow a male hero undergoing a seemingly impossible quest, where he is both assisted and inconvenienced by divine intervention. While the hero’s success almost always hinges on the assistance he receives from a maiden, an archetype defined as a young woman who helps the male hero overcome any obstacles he faces and who often becomes romantically involved with him. Notable examples of this archetype include Ariadne and Medea. Both women betray their fathers to help their lovers, Theseus and Jason, respectively, before these “heroes” actively discard them.

In Ariadne’s case, Theseus abandons her on the island of Naxos, where the god Dionysus (or Bacchus, in the Roman tradition) finds her and marries her. Medea’s fate is far more notorious: She is known for murdering her own children as a tribute to Jason’s betrayal. Yet rather than portraying Medea as the antagonist, Euripides’s Medea, an Athenian tragedy, utilizes intimate monologues to present the tension between gendered perspectives.

Though the debate on wheth-

“Medea is a microcosm of the largerscale tug of war between the traditional... and the marginalized peoples.”

er the play’s feminist themes are intentional is still ongoing, Medea nonetheless reframes a famous myth by introducing the women’s perspective to the default male narrative. The play overall functions as a historical example of how women can reclaim their voices in ancient texts.

By naming his play after its heroine, Euripides quickly establishes Medea as its central focus, rather than the more conventional choice of Jason. Medea’s exchanges with the Chorus, lengthy and intimate, detail her plans for revenge on Jason, who plans on abandoning her to marry the princess of Corinth. Rather than portraying Medea as the damsel in distress, Euripides depicts her

as a woman who survives a society constantly trying to tear her apart. Medea is not perfect. Indeed, she despises child-bearing, daring to inflict harm on her children to destroy her enemies. Medea contradicts the popular concept of maternal bliss when she

Graphic by Teri Kim

says, “I would very much rather stand/Three times in the front of battle than bear one child,” while also acknowledging that “what applies to [her]” may not apply to the Chorus of women (Euripides 9). This statement indicates that each woman holds a unique perspective that stems from their unique experiences. Yet, all narratives from female perspectives share a similar thematic oppression. Euripides portrays a confrontation between Medea and Jason, where she recounts the events of Jason’s quest to Colchis, where Medea was princess, and takes credit for his survival (Euripides 16).

As a narrative concerned with a woman’s perspective, Medea still portrays the dominant male attempt to maintain the status quo. Jason, for one, claimed that Medea took more than she gave, despite her saving his life in Colchis (Euripides 17). In Jason’s perspective, he is the sole hero: the rightful king of Iolcos who singlehanded retrieved the golden fleece and settled Medea into a “civilized” Greek society in steep contrast to the “barbarian” land of Colchis (Euripides 17). This exchange is emblematic of the traditional male perspective’s historical othering of female narratives. In this way, Medea is a microcosm

of the larger-scale tug of war between the traditional, male, and the varied perspectives contained in women and other marginalized peoples.

Thus, by switching the focal point of the myth to Medea, and establishing many varied interactions between her and the Chorus, the play Medea highlights the abundance of female perspectives that are equally as compelling as the traditional, male hero’s point of view. Furthermore, Medea’s interactions with male authority figures effectively showcase how their perspective of individual women is skewed by the notions of womanhood and motherhood. By restraining women to the domestic sphere, the society takes away each woman’s individuality and personhood. This emphasizes the importance of listening to multiple perspectives present in the same narrative. Not only depicted in classical myths like Medea, but also inherent in contemporary renditions of fairy tales like Wicked, the designation of hero and villain in every tale largely depends on who is narrating the story. Oftentimes, the messages sent by malefocused narratives concur that only men are capable of winning glory. Women, on the other hand, must suffer in silence to avoid in-

famy. The contemporary wave of retellings focused on female characters has helped combat this dilemma, as the modern audience delves into the compelling minds of historically vilified women. Euripides’s Medea is, therefore, a remarkable early example of an artist who realized the importance of shifting the narrative.

Myth as Mask: From Aeneas to MAGA

Leon Zheng ’26

Princeton Day School, NJ

From the ashes of Troy, Aeneas sets sail—not just for survival, but in an attempt to fulfil his prophecy. He protects his people, leads his son by the hand, and bears the weight of divine will on his shoulder: the founding of a new empire that will “rule the world” (Aeneid 1.279). This mission, bestowed by Jupiter himself, elevates Rome from a mere city to the centerpiece of history. The myth of Aeneas—immigrant, warrior, chosen one—was not just entertainment for ancient Romans; it was the sacred justification for conquest, empire, and national exceptionalism. Fast forward to modern times, and we find eerily similar narratives. The American notion of Manifest Destiny, the British Empire’s “civilizing missions,” and contemporary slogans like Make

America Great Again all draw upon an identical ideology to attract faithful followers. They promise glory to a group of chosen people, claiming to be either divinely or morally imperative, which justifies oppression. Just like Aeneas, who was blessed by the Olympian gods to establish the Roman Empire on conquered land, modern political leaders often cloak expansion, colonization, and war in the language of destiny and virtue.

But what lies beneath these founding myths—ancient and modern—are often stories of violence, exclusion, and selective memory. They are not merely tales of origin; they are tools of power.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, written during Augustus’s reign, Aeneas is portrayed not as a conqueror, but as a pious servant of fate. He does not seek power for himself, but rather, passively fulfills a divine order. Even his acts of violence—like the

killing of Turnus at the end of the epic—are portrayed not as the realizations of his ambition but as the fruits of his obedience.

This portrayal was no accident. Emperor Augustus deliberately commissioned Virgil to shape Aeneas’ narrative. The Aeneid served as a work of imperial propaganda, carefully crafted to legitimize Augustus’s rule and unify the Roman people under a shared origin myth. The poem elevates values like duty (pietas), sacrifice (sacrificium), and divine favor (numen)— virtues Augustus prided his regime on. Aeneas’s journey mirrors Augustus’s rise to power after the civil war. In addition, both “protagonists” promised a restored golden age under their leadership. Through this lens, Rome’s expansion became not only acceptable but sacred. Fate propelled the Julian clan to conquer. The gods are

“These stories sanitize brutality and elevate empire-building to a sacred act.”

on their side. This narrative gave Rome a moral shield. Its imperial expansion is not motivated by greed, but by the divine will. The sufferings which Emperor Augustus inflicted on others (e.g., the Germans, the Carthaginians, and the Greeks) were inevitable. Genocides became justifiable, even necessary, to give birth to a golden age. Romulus and Remus, the twin founders of Rome, take this a step further. As the children of Mars, the god of war, they embody Rome’s violent nature, explaining Rome’s martial prowess. Romulus’s brutality, which eventually led to his killing of his brother, became celebrated, indicative of Rome’s ruthless unity and strength. These stories sanitize brutality and elevate empire-building. And perhaps, even more importantly, they establish a myth of legitimacy: Rome is not just a nation; it shapeshifted into the rightful ruler of the world.

Centuries later, in the United States (U.S.), a similar myth emerged: Manifest Destiny—the belief that the U.S. was destined to expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Politicians, preachers, and journalists framed westward expansion not as conquest, but as the

spread of “civilization,” democracy, and divine purpose.

Like its Roman counterparts, Americans in the nineteenth century imagined themselves as the inheritors of God’s sacred mission, destined to bring light to the wilderness. The newly settled Americans of European descent deemed Native American nations, the rightful owners of the land, as barbaric. Like Aeneas’s troops, the American battalions swept aside those who stood before them. In this story, violence was framed as a necessity; the Indian Removal Act was forcefully justified; sixteen thousand lives were destroyed—all for the sake of a nation’s “destiny.”

The rhetoric of Manifest Destiny borrowed heavily from biblical and classical motifs. The New World was the New Eden. The Founding Fathers were the new Aeneases. Washington, D.C., was built with Roman columns and Latin mottos for a reason: the republic imagined itself as the successor of Rome, not just in form, but in divine right. The British Empire, too, wielded its mythic narrative to justify global domination. The idea of the “White Man’s Burden,” popularized by Rudyard Kipling, casted imperialism not as exploitation but as a benevo-

lent duty. They perceived colonizers not as thieves; Rather, they portrayed the settlers as teachers. They did not steal native lands; Rather, they enlightened their newly found subjects. This narrative is uncannily similar to Virgil’s promise that Rome will “spare the conquered and subdue the proud” (Aeneid 6.853). Both empires justified expansion as a moral calling. And in both cases, the voices of the conquered were excluded from the myth.

Just as the suffering of Dido and Turnus are sidelined in the Aeneid, so too are the perspectives of India, Kenya, or Ireland erased in British imperial memory. Myths thrive on simplification. Thus, founding narratives must be clean, heroic, and above all, legitimate.

“Myths thrive on simplification. Thus, founding narratives must be clean, heroic, and above all, legitimate”

Graphic by Eleanor Wang

Even in the 21st century, these mythic patterns persist. Political rhetoric continues to draw on ancient structures of divine purpose, exceptionalism, and chosen identity. In the United States, the slogan “Make America Great Again” functions like a modern myth, reviving a golden age. Though vaguely defined and often idealized, this narrative creates a sketch of a far more powerful, superior, and unified America. Though it provides no specific timeline or policy, the American people deeply resonate with the phrase’s emotional appeal to lost greatness.

Like the Aeneid, which portrays the founding of Rome as the recovery of order after chaos, “MAGA” suggests that America has strayed from its original rightful path—and must return to its glory. It flattens history, glossing over the transatlantic slave trade, Plessy v. Ferguson’s irreparable harms, the generational traumas that the grandfather clauses buried, and ongoing systemic injustice. Instead, it constructs a sanitized past to justify present ambitions. It taps into the same machinery that made Manifest Destiny persuasive: a blend of nostalgia, identity, and righteous purpose. But as with ancient myths, the danger lies

in its usage of the Tyranny of the Majority. Calls to “make America great again” often ignore the experiences of marginalized groups whose pasts were marked not by greatness, but by oppression. Just as Aeneas’s victory came at the cost of Turnus’s life and Dido’s despair, nationalist myths often rely on forgetting paired with rewriting and individual sufferings that helped create “greatness.”The Aeneid ends with the brutal killing of Turnus, a man begging for mercy. Aeneas stands over him, driven by duty, but no longer innocent. In that moment, Virgil dares his readers to ask themselves this: Is fulfilling one’s destiny worth the blood the mission spills?

Today, we must ask the same of our modern myths. Who do they glorify? Who do they erase? And what would it mean to tell a different kind of founding story—one rooted not in conquest, but in humility and justice?

Because in the end, myths don’t just explain the past—they shape the future. Whether in Rome’s golden age or a red baseball cap, the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and who we have been will shape the kind of nation we are on the path of becoming.

Conscience Against the Crown

Stella Liao

The Hotchkiss School, CT

Sophocles’ Antigone, written in the 5th century BCE, tells the story of a young woman who chooses to defy the king’s law to honor what she believes is a higher moral duty. King Creon forbids the burial of Polynices, Antigone’s brother, after a civil war in Thebes, and labels him a traitor. Antigone insists that her brother should be buried and honored, so she disobeys the command from the king. Her choice leads to her arrest and eventual death. This story reveals the conflict between individual conscience and state power, which remains relevant today. Antigone’s resistance connects with the role of civil disobedience in confronting injustice, from historical struggles like the civil rights movement to today’s global protests against authoritarian regimes. Antigone’s action reveals the timeless tension between the law of the state and the law of individual conscience. Creon’s decree is legal,

but Antigone thinks it is not just. Antigone appeals to the “unwritten and unshakable laws of the gods,” which she places moral obligation above political authority. This distinction is the heart of civil disobedience: the refusal to obey laws or commands when they contradict fundamental human values. Antigone’s act is not lawless rebellion, but a deep principle. This concept has shaped the actions of countless protests throughout history that originally struggled to obey the higher legitimacy but finally stood up for themselves or the group the represent, such as Rosa Park, who stood up against Jim Crow law; and Rumeysa Ozturk, a student who protest against Tuft University’s political stand on the Israel-Gaza conflict.

Figures in the twentieth century, such as Rosa Parks, demonstrate how Antigone’s spirit of defiance lives on. In 1955, Jim Crow laws were a set a racist segregation rules against blacks. In Park’s situ-

ation, a black person is obligated to give up their seat when there are not enough seats on the bus. Park’s refusal to give up her seat on a segregated bus was a violation of the law, but just as Antigone, she acted from a place of moral clarity—everyone should be treated equally. Her quiet resistance became a turning point in the American civil rights movement because it exposed the injustice underlying the legal system. Similar to Antigone, Park’s action did not provoke chaos in public; Instead, they both started from a small action to assert dignity and humanity in the face of systemic oppression.

A modern example that resonates with Antigone’s story is Rumeysa Ozturk, who is a Turkish Ph.D. student at Tufts University. She became a prominent figure for her courageous stand against institutional authority. In March 2025,

“Instead, they both started from a small action to assert dignity and humanity in the face of systemic oppression.”

Ozturk co-authored an op-ed in The Tufts Daily criticizing Tufts’ response to student protests over the Israel-Gaza conflict and the school’s advocacy for divestment from companies tied to Israel. After her article was published, she was arrested by federal agents near her home in Massachusetts, and her student visa was revoked. She was detained in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for over six weeks. Her case soon drew national attention, which sparked a debate about free speech and due process. A federal judge eventually ordered her release because the detention was a violation of the First Amendment. Ozturk’s unwavering commitment to her principles mirrors Antigone’s stand against Creon’s edict. Both figures chose to uphold moral and ethical obligations even in the face of personal risk.

In Sophocles’ Antigone, he presents a heroine who chooses to stand up using unwavering integrity in the face of injustice rather than violence. In every age, from ancient Greece to the modern world, there are always those who choose to follow the voice of justice over the commands of authority. Their courage reminds us that the health of any society depends on the willingness of its citizens to stand up for what is right.

Echos of Roman Language in Contemporary Politics

Angel Yu ’26

St. George’s School, RI

The language of ancient Rome stillThe language of ancient Rome still echoes in modern political discourse, encapsulating the ideologies, structures, and foundational concepts that have carried on from the past to the present. Terms such as civitas, libertas, imperium, and servus function beyond mere descriptions. Instead, they serve as enduring commentaries that help understand the Roman identity and social stratification. Far from serving as the relics of antiquity, their relevance seeps into modern-day political events and conflicts, providing endearing insight into the modern pursuit of equality, freedom, and authority. In the Roman Kingdom (753-509 BC), Libertas was the female personification of liberty. Later, in the republic, the word began to carry a

heavier political and moral connotation. The significance of libertas lies in the essential state of being it encapsulates, free. The definitive term of freedom extends beyond human emotions and societal perceptions: Being free, or libertas,

“Being free, or libertas, means not being subjugated to tyranny”

means not being subjugated to tyranny, the state of forced labor, or any expression of the oppressor’s arbitrary will. Possessing libertas simultaneously gives one political and individual autonomy. As such, libertas was celebrated as an essential condiment to the making of

Graphic by Bella Wu

an ideal Roman citizen, one who could express in the Forum and vote according to will.

The concept later evolved into an essential construct that distinguished the Roman Republic from a monarchy. Eventually, the Roman Empire proceeded to adopt and redefine this notion, as it sought to restore true libertas after the chaotic aftermath of the civil wars. Like all pursuits of freedom, libertas still existed within limitations and contradictions. Women, slaves, and foreigners were often excluded from this ideology, similar to how modern democracies were inconsistently applied while proclaimed as a universal right. One can find this paradox evident in the span of American history. From Jim Crow law to more con-

“From Jim Crow laws to... Black Lives Matter, the rhetoric of liberty has coexisted with racial exclusion.”

temporary movements like Black Lives Matter, the rhetoric of liberty has coexisted with racial exclusion. While championing the ideal libertas, its lived reality remains insufficient from the past to now, where true liberty always stands as an almost unapproachable truth that people across time and place have tried to reach.

The concept of civitas also finds clear parallels today with the term citizenship. Closely tied to libertas, civitas denoted not only the legal status of Romans but also served as a symbol of belonging. The word covers the moral and communal obligations of Roman citizens, such as voting, owning property, marriage, and military service, asserting both the rights and responsibilities of a citizen. Gradually, as Rome expanded, the audience that this term encompassed also widened. Originally, the term was limited to adult males of a certain birth and wealth, but the establishment of the Edicta Caracallae in 212 CE extended citizenship to a larger scale. Particularly since the late Republic to the Roman Empire, civitas was granted to allies, provincials, and eventually all free inhabitants under the jurisdiction of the Roman Empire. While this expansion contrib-

uted to consolidating the empire, many have viewed it as a dilution of the exclusivity and prestige once attached to Roman citizenship. In modern times, the definition and interpretation of civitas remain a largely contested issue, carrying significant legal weight. The refugee and immigration crisis in Europe and the United States invoked conflicts between birthright citizenship and naturalization, continuing the tension between addressing legal status and human dignity. In the United States, the struggle over immigrant status has made the idea central to American national identity. It represents more than a legal status, extending to the protections and rights one is entitled to. Just like how civitas was refined to serve imperial goals, the modern concept of citizenship is often shaped by political agendas to determine whose voices matter. The decisions to include and exclude both continue to shape society’s understanding of the limits and possibilities in modern politics.

If libertas and civitas functioned as the definitive means of Roman citizens, the term imperium referred to the authority that constructed Roman governance. Originally, imperium was the legal

power possessed by authoritative figures of Rome, from magistrates and generals to consuls and praetors. By the Roman Empire, it had evolved to represent the sovereignty of Rome itself and the centralized, almost autocratic power of the emperor. The concept of imperium was often justified and glorified by divine sanction, empowering the emperor to be the only figure who was able to directly approach divinity and thus able to have imperium. The term was inherently hierarchical and utilized to assert a singular, superior form of power. Modern equivalents of imperium can be found in both traditional authoritative regimes and the emergence of centralized executive powers around the world. National leaders in countries like Russia or Hungary have employed the preservation of order to justify the centralization of power. This parallels the ancient approach to imperium in Rome, where emperors legitimized autocracy while preserving the illusion of republican values. Emergency powers are often the central debate regarding the modern interpretation of imperium. For instance, during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, controversies have emerged around the overarching executive

power to protect public safety and the preservation of democracy. Similar to how Roman emperors claimed to protect libertas while exercising total control, modern leaders often legitimize centralized authority under the guise of civil freedom.

At the bottom of the Roman power hierarchy was the servus, which can be directly translated as slaves. Slaves possessed neither libertas nor civitas, yet they composed the very foundation on which Roman society was built. In Rome, servus extended beyond an economic institution, lying in the societal and judicial sphere. A slave held no legal rights or any measure of personhood, and their living conditions sharply contrasted with free Roman citizens. Slaves made up a large proportion of the Roman population, with people either captured, born into, or sold into slavery. The Roman identity was largely defined in opposition to servus, stating the legal and communal privileges of citizenship. While civitas could be granted to slaves, slaves were still restrained by systematic oppression to remain socially inferior. In modern times, forced servitude continues to make the struggle of servus resound in global crises.

Modern forms of dehumanization and control cntinue to be evident in human trafficking, exploitative labor in global supply chains, and the systematic disenfranchisement of the working class. In multiple cases, immigrant workers confront similar conditions of servus, such as a lack of basic rights and limited freedom. Those bound by the modern adaptation of servitude contribute largely to the present global economy, yet, just like the class of servus in ancient Rome, they are denied adequate acknowledgements and protections.

The ancient syllables continue to echo in the present day, as the legacy of these terms reminds people that political ideals are always contested. These terms provided insight into how power structures and politics are justified, redefined, and challenged over time. Together, they shape how identity, freedom, and authority are understood in the status quo. By revisiting the wisdom of the past, we are better equipped with a multifaceted perspective to observe the consistencies and contradictions that persist in the modern world, questioning how the language of power continues to write the definition of justice.

Graphic by Eleanor Wang

Jugurtha, the Forgotten King

Aurelia Zhang

Philips Andover Academy, MA

At the end of Gaius Marius’ triumphal parade, Jugurtha’s golden earring is torn off his earlobe, officially ending the Jugurthine War, a conflict that was waged between the North African kingdom of Numidia and Rome. This is the same illegitimate nephew of Micipsa who denounced Rome to be “a city for sale” in Sallust’s Bellum Jugurthinum, portrayed as a symbol of resistance to the corrupt aristocracy of the late Republic. In the English academic world, Jugurtha was like the others: a foreign king challenging Rome’s authority–just another Mithridates, or Cimbrian leader. He was one of the many arrogant contenders that Vergil warned about: to treat with debellare instead of parcere.

Jugurtha was like a character foil to Gaius Marius, whom Sallust praises based on his cynical views,

accentuated by the events happening in his time amidst the century of civil war. With Rome acting as a mediator, Jugurtha bribed senators in unimaginable magnitudes to yield results in his favor. This overturned decades of Numidia’s alliance with Rome started with Masinissa, Jugurtha’s grandfather, who fought alongside Rome in the 2nd Punic War. It was also through serving under the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus that Jugurtha gained favor with the Romans, allowing Micipsa to accept and adopt him. Yet Jugurtha’s unbridled ambition becomes fully evident when he forces Aulus’ army to pass under the yoke, humiliating them after their defeat by the Numidian army. It’s not difficult to recognize that Jugurtha is a capable military leader, a man whom the Romans would contend almost as an equal, and whose vices were hardly unique.

His name is rarely mentioned without Sallust,whose detailed descriptions extend beyond events themselves to include the geography and people of Numidia. These early attempts at biased an thropology can also be seen in its contemporaries like Caesar’s Gal lic Wars or, a bit later, Tacitus’ Germania. Sallust character ized the Numidian people as “faithless, of fickle disposi tions, and fond of change”, which was the rationale for their defeat and meant to show Rome’s superior tac tics. These qualities may be true in Jugurtha’s case, mostly towards the end of the war, where he escaped capture multiple times, but such vast generalizations of ethnic traits serve more as com mentary on Roman so ciety than genuine descriptions of the people who inhabited Numidia at the time.

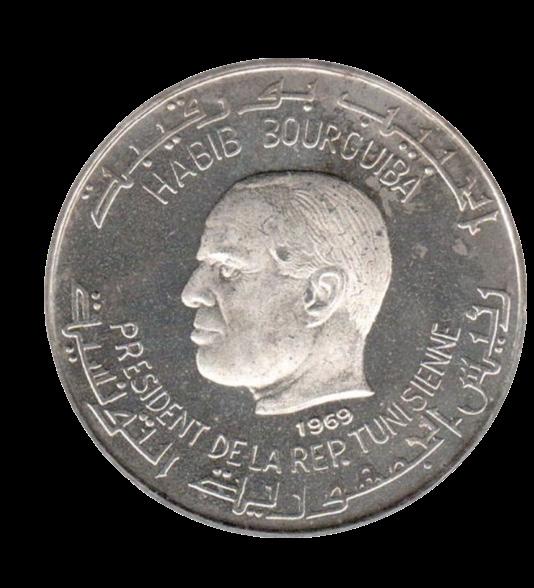

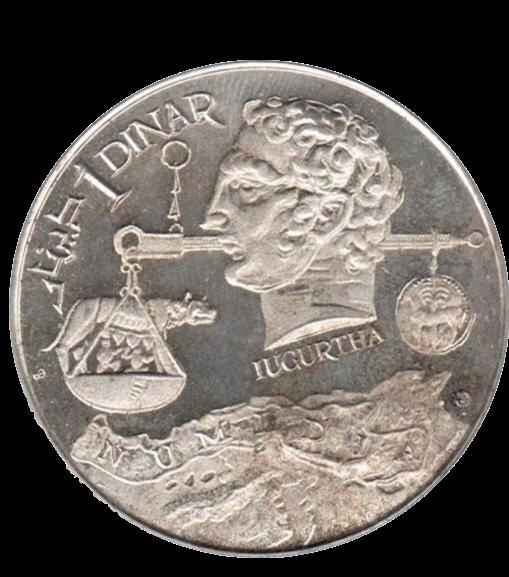

bleland in Tunisia was said to be a place where Jugurtha fortified to hold off Roman legions. He could also be seen on modern coinage: On this dinar, one side is the traditional GrecoRoman profile of Habib Bourguiba,

Jugurtha lives on in the language and landscape of his country. The Jugurtha Ta

the first president of Tunisia, who liberated his country from French control. On the other side is the bearded, hairybrowed Numidian who dared to snatch Roman authority from the pedestal and weigh it on a scale. One narrator’s enemy becomes another’s national hero.

Pictures depicts a 1 dinar coin in Tunisia, 1969

Contributers:

Anonymous

Victoria Adeoye

Riley Casey

Teri Kim

Erin Li

Stella Liao

Karina Stakh

Eleanor Wang

Bella Wu

Angel Yu

Zixuan (Angel) Xin

Aurelia Zhang

Leon Zheng