When we started working on this issue, we kept coming back to one idea: What does verge mean to us? There was something compelling about trying to capture a moment that is on the edge of difference. But what does it mean to freeze a moment that, by its very nature, refuses to be still?

When thinking about how to capture such a moment, we were interested in the in-between. Our “Crossing the Line” photoshoot allowed us to be unconventional, certain in the uncertain, and a little chaotic. It pushed us to see things differently. “The Vision” showed us something else: clarity isn’t the point. Contrast is. You either see it, or you don’t. From there, we were inspired to attempt to capture the current climate of journalism with “Breaking News.” The future of news feels increasingly unstable teetering on exhaustion and reinvention. It can push us to the brink, but it also opens the door for the kinds of conversations about where we need to go from here.

This issue reflects what we care about right now: honesty in storytelling, creative risks, and a willingness to sit with questions that don’t have easy answers. Whether it’s through reported features, essays, or art, our contributors pushed beyond the surface, and we’re grateful to have worked with all of them. We truly can’t thank our entire staff enough for all their hard work. We’re especially grateful for our Executive Board: Sophia Bretas-Kaisermann, Alexandra Nakamitsu, Sam Belmar, Leah Kohler, Jordan

The Official CW Welcome Returns

An Interview with David Crank W&M Professors’ Visions for the Future

Clean the Ravine

New Marine Science Major Makes a Splash Crossing the Line

What Would You Put In a Time Capsule?

Yesterday's Tomorrow

Breaking News

Why are TV’s Dumb Characters “Dumb”?

On the Verge of Growing Up TribeLive

What will you be wearing in 30 years?

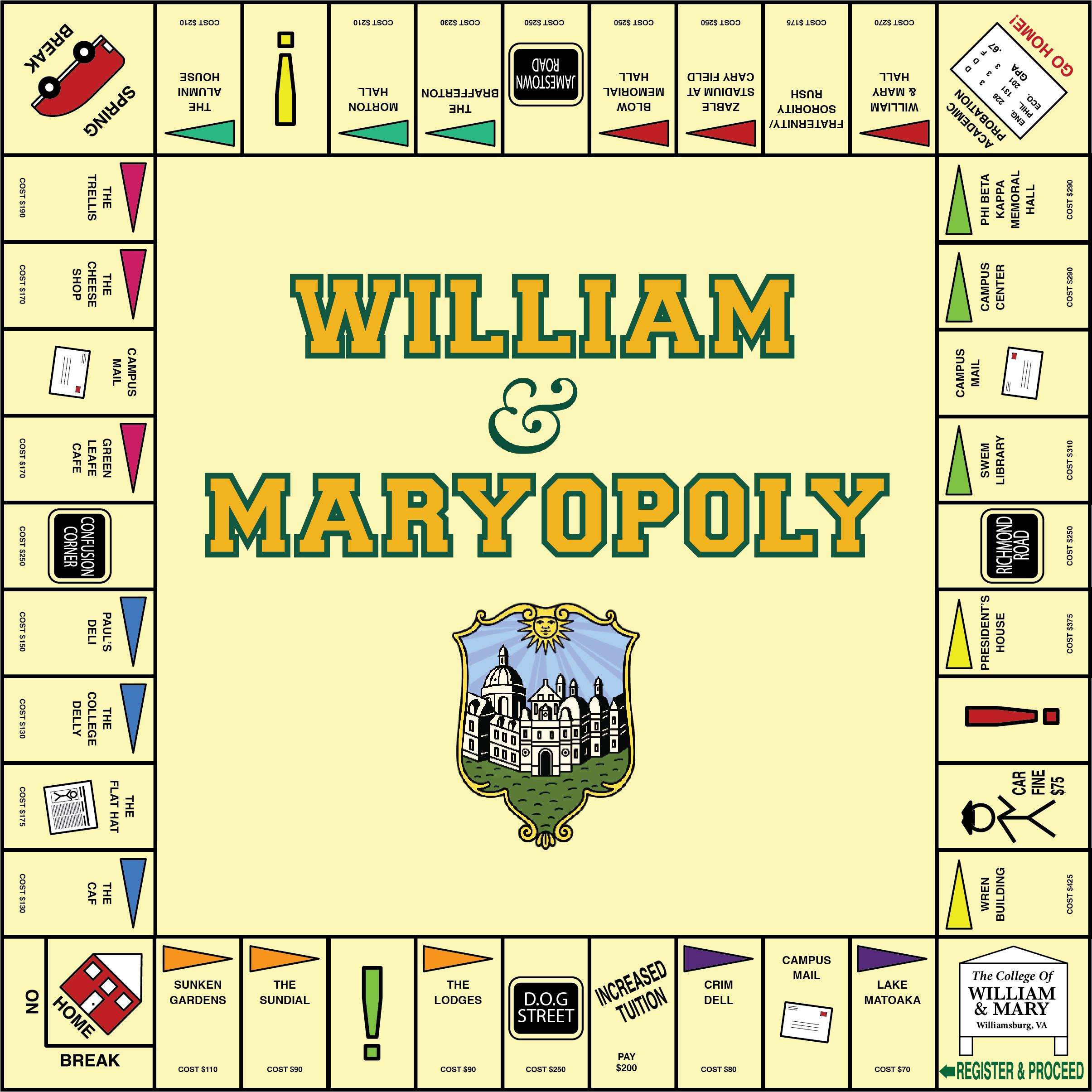

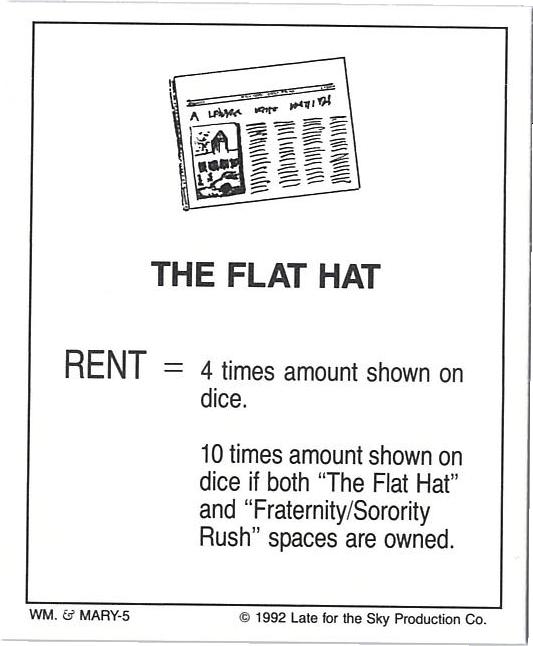

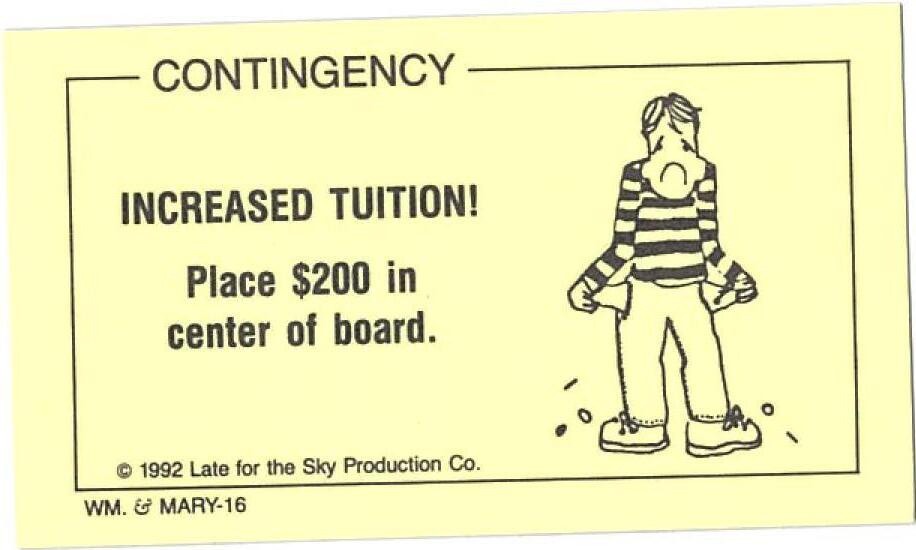

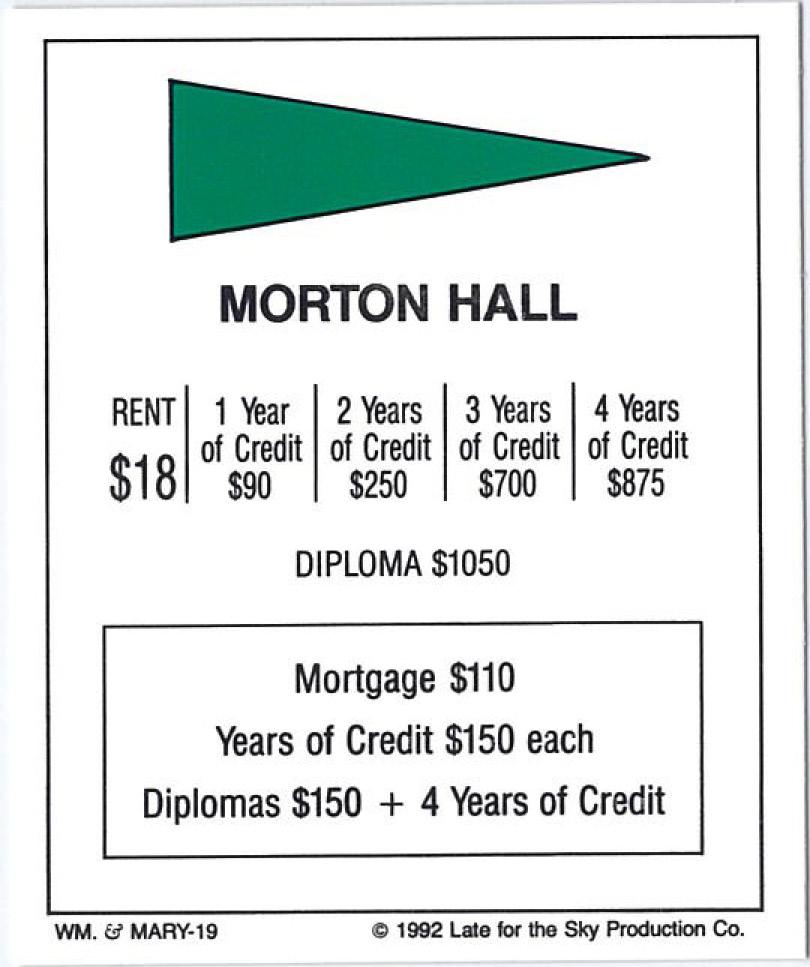

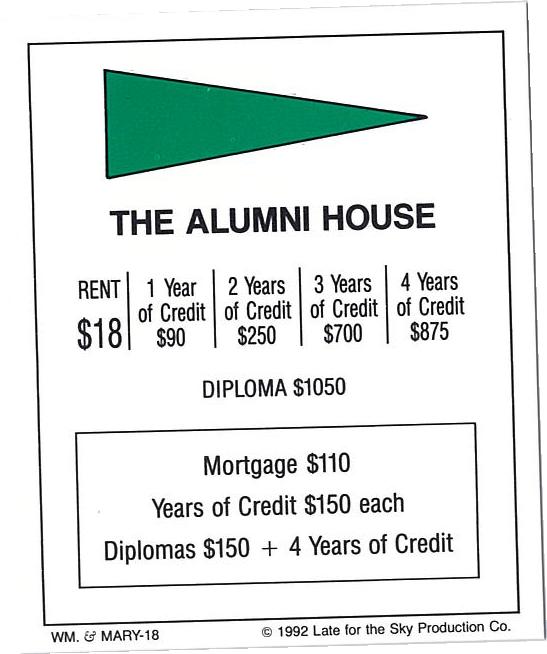

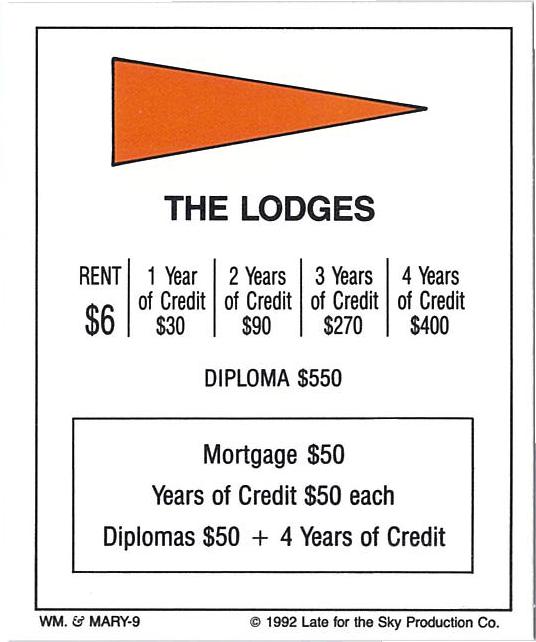

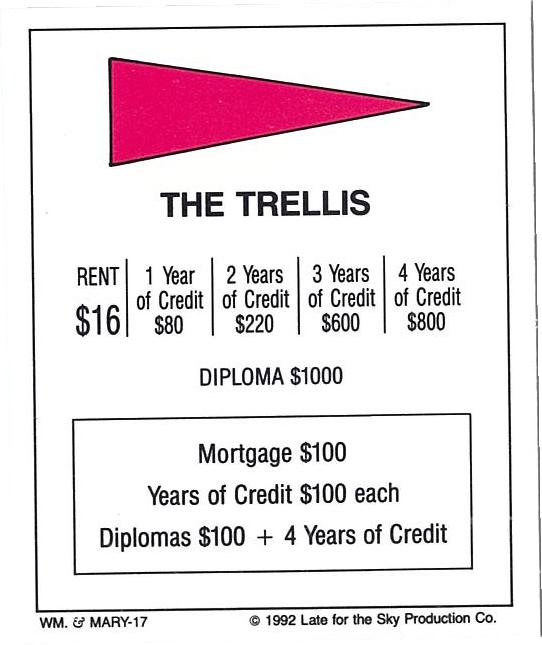

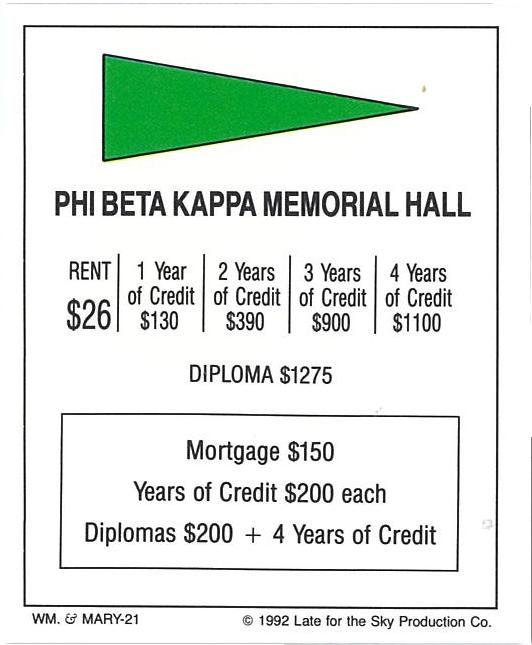

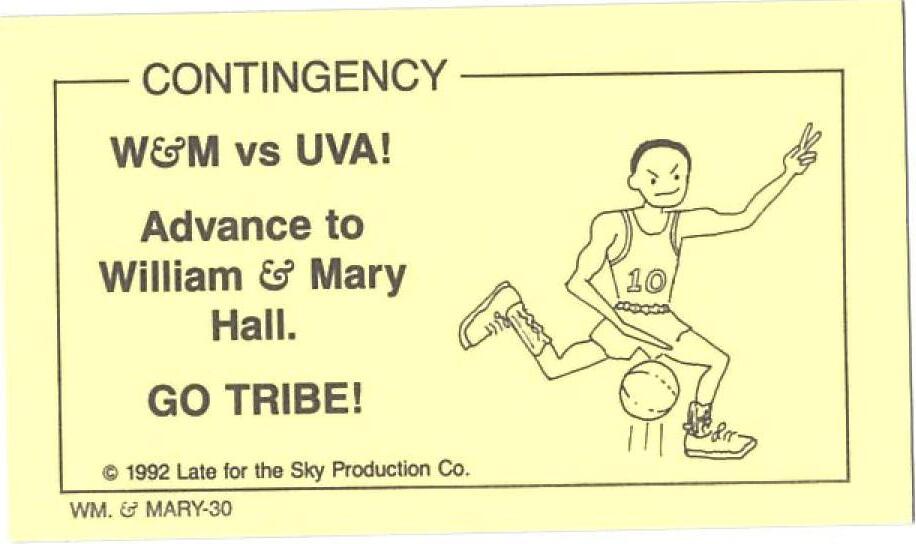

The Vision Felicity Williamsburg Adventure William and Maryopoly Mighty Mixotroph Hot Chocolate Contest

Trader Joe’s Microwave Meals Get the F*** up

The event reappeared on the orientation agenda this year after a decade-long hiatus. I sat down with Lauren Garrett to dig into its history, peek into its future, and ultimately answer the question: why did it go away?

As a three-time Orientation Aide, I thought I’d seen and done it all, I didn’t even need to look at this year’s schedule when it dropped — I already knew what was on it. But I did look, and when I saw “Colonial Williamsburg Welcome” on the agenda, I was stumped. In orientation training, it was revealed that this year marked the return of the Colonial Williamsburg event after a decade-long hiatus. We were instructed to meet in Merchant’s Square and were told that the event would include a myriad of activities for new students. We returning OAs had no idea what to expect. The day arrived, and every new student packed into Merchant’s Square, anxiously awaiting the start of a new event about which their OAs could offer little insight. The OAs themselves were equally excited and anxious –– unlike the routine events which run year after year, we couldn’t prepare for this.

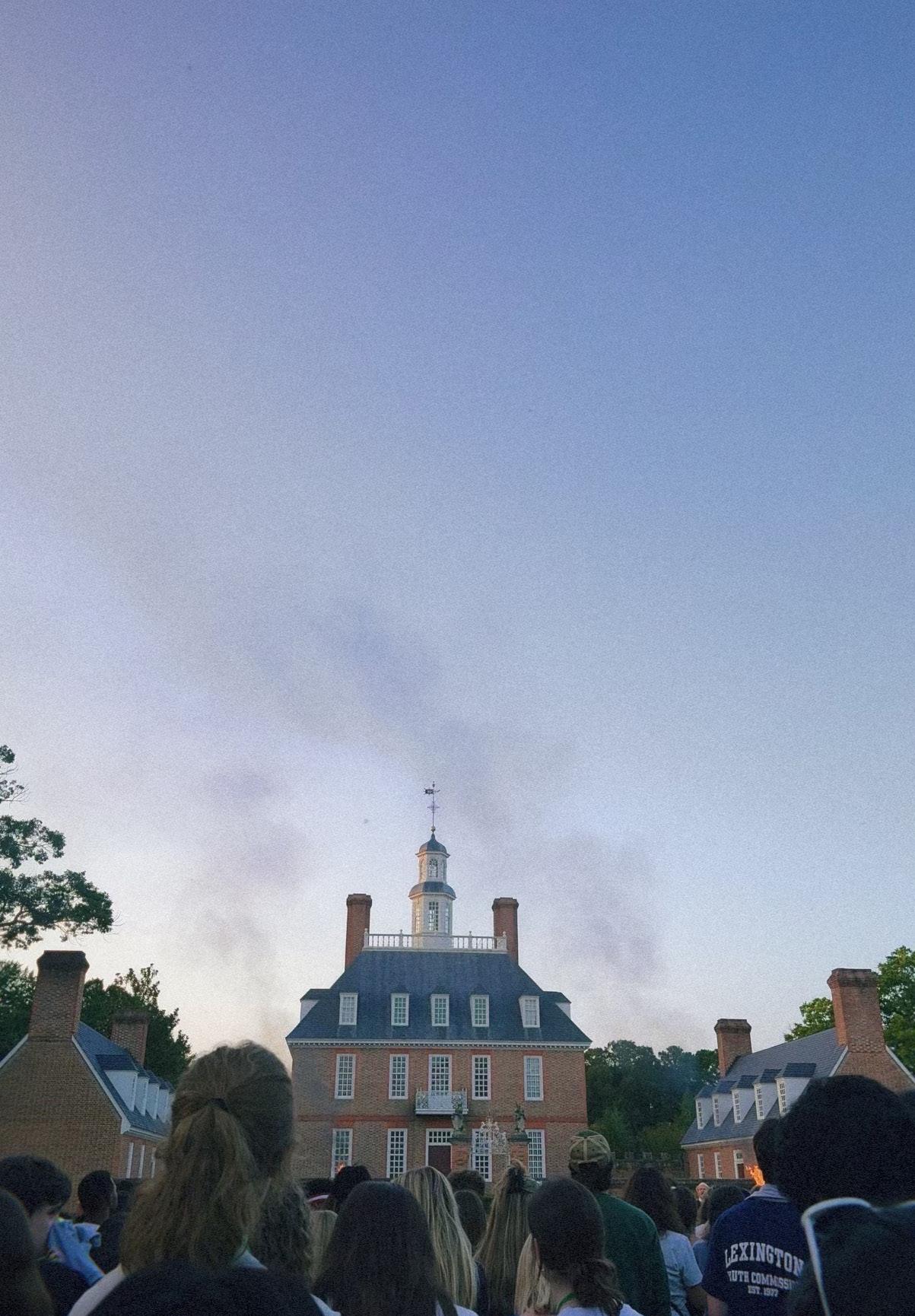

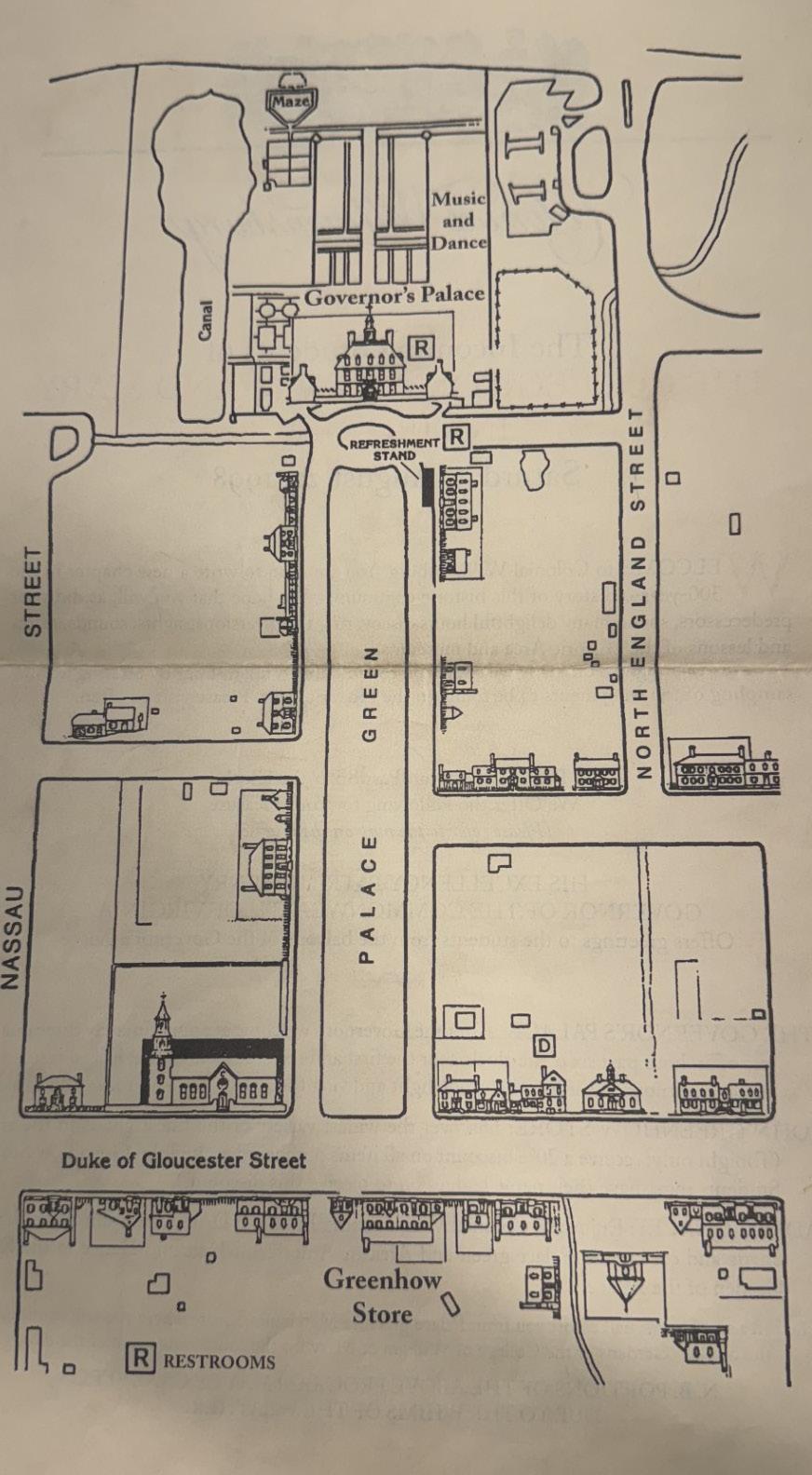

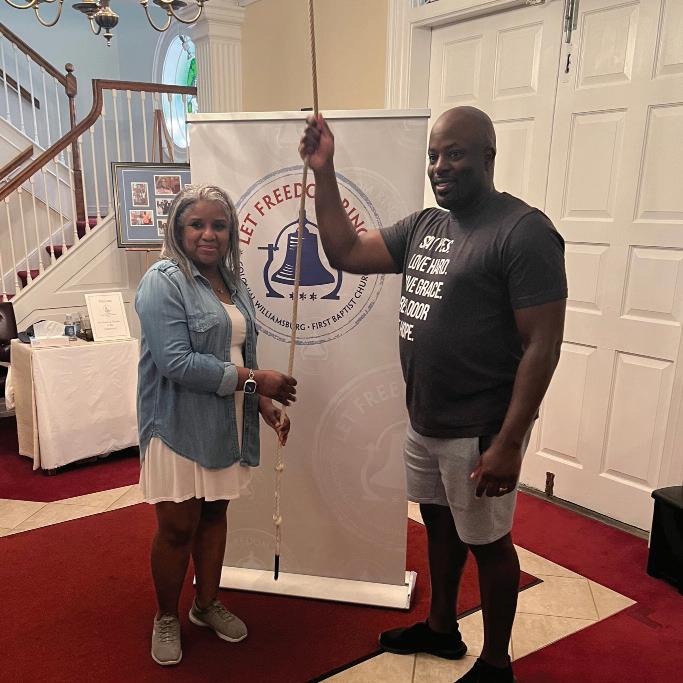

A reenactor ascended the steps to a nearby house on Duke of Gloucester Street and addressed the restless crowd, taking on the persona of a ‘Nation Builder’. He spoke of freedom and liberty, but also of the bright minds educated at the College who are charged with bringing this founding vision to life. New students were on the edge of something great, about to join a collection of revolutionary intellectuals whose legacy spans centuries. The speech was certainly a novel way to begin an orientation event, conjuring both sentiments of patriotism and school pride, a special kind of charm. The address closed with instructions to follow the Fifes and Drums in a procession toward the Governor’s Palace. And follow we did, in what was arguably one of the most awe-inspiring experiences of orientation. Walking alongside some of my closest friends, leading my final cohort of new students, escorted by the iconic Fife and Drum, I felt connected to the history of our college, our city, and our nation in a way I never had before. Without a doubt, it was an experience I’ll tell my grandkids about someday.

The music died down as the herds were released upon the Palace Green, and its nearby historical reenactors, who had clearly been preparing for this moment, jumped into action. The mission of CW, “that the future may learn from the past,” truly came alive, with students, new and old, diving head-first into hands-on experiences.

One group of reenactors offered a lesson on the partnered dancing of colonial America; students and OAs alike scrambled to join the line, which ended up spanning the entire length of Green. I couldn’t help but find this reaction uniquely TWAMP-y — to not only have an interest in something as niche as colonial-era partner dancing, but to grab your friends and run towards it. I filmed my co-OA as he joined a colonial drum circle, spurred on by another troupe of reenactors; some of my students filed into a booth

Seb on drums!

offering information on volunteer and work opportunities in CW. Everywhere I looked, I saw smiles, and everywhere I listened, laughter. A community experience of childlike wonder and curiosity, the willingness to learn something new, to fail at it, and to try again. Watching new students and old unabashedly immerse themselves in what many Gen Alpha middle schoolers might consider “cringey” (if that’s a word they even still use), I was once again reminded of how special this College is and the student body it attracts.

After what felt like all too short a time to explore the offerings, we gathered on the Palace Green for a number of moving speeches by reenactors, urging students to continue exploring CW throughout their time here and examining what the past can teach us. We were also treated to remarks by Clifford Fleet B.A. ‘91, M.A. ‘93, J.D. ‘95, MBA ‘95, President and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

During orientation training, we had been told that the night would “end with a bang.” At 8:30 p.m., on a random Saturday in August, CW set off a fireworks display that rivaled their annual and infamous Grand Illumination, and they did it just for us.

I walked away from my first and last Colonial Williamsburg Welcome, sad that it had been missing from my past three years, but also filled with immense gratitude that I could be present for its return. Reflecting on the seemingly magical night, which I do with relative frequency, I can’t help but wonder what happened — why did it disappear? And will it stick around this time? Scrambling to preserve my connection to orientation, something I will miss profoundly post-graduation, I set out to memorialize the history of the Colonial Williamsburg Welcome and understand what is in its future. I reached out to the only person I knew would have the answers I needed: Lauren Garrett ‘02, M.A., Director of Student Transition and Engagement Programs, who is more casually known as the queen of the College’s orientation.

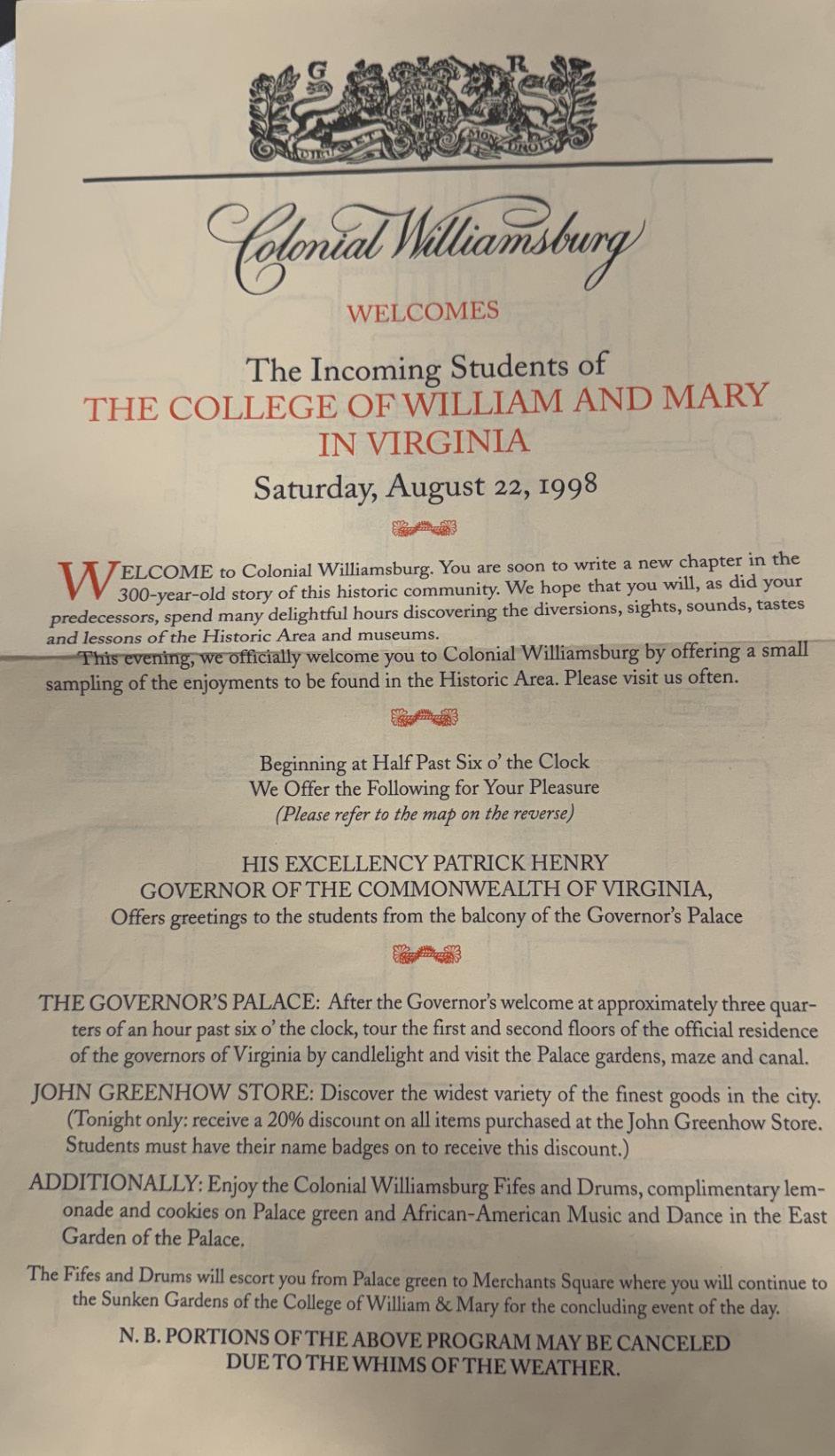

“The Colonial Williamsburg program that was typically held during orientation has always ebbed and flowed,” she said. Garrett recalls the event from her orientation, admitting, “I can remember this event, and I remember it started at half past six, but I remember it being hotter than

all get out. And I remember being so miserable and at the same time thinking it was really cool.” In her extraordinary freshman year scrapbook, she saved the formal invitation and accompanying map from the event, pictured on the left. It is unclear whether the event continued for the duration of her undergraduate experience. “I was an RA sophomore and junior year, and I was a head resident for Botetourt my senior year. I don’t remember the Colonial Williamsburg event happening those years. I have no recollection, there is nothing in my scrapbook, and yet I was present during orientation because I was an RA. So I’m asking my brain, like, is it selective memory? Did it not happen? I can’t find proof that it happened.”

In her recounting of the Colonial Williamsburg Welcomes of the past, the event looked much different than it had this year. “We sat on the Palace Green, they did this talking, there was a refreshment stand, and then it just sort of dissipated,” said Garrett. “We were led out of the Palace Green by the Fife and Drum, which is still cool, but at the same point in time, many people had already left to go back to the Sunken Garden, so not as cool.” This explains why new students were processed in rather than out of the event this year. Garrett also observed, “It felt a little weird as a student, like, oh, we had to get here on our own, and now you’re leading us away?”

Rather than the pomp and circumstance to welcome students into CW, her event seemed to end with a big ‘get out!’, though she acknowledges that it likely wasn’t the intended message, stating “things just looked different.”

When she returned to the College over twelve years ago, “orientation had already happened for that academic year based on [her] hiring date, and that year, they had to cancel the CW connection” due to a Williamsburg trademark downpour. The following years brought similar weather, ending also in cancellations of the big event. “It felt like the weather was out to get us, and so of course, you know, after a while you’re like, why do we keep trying this if it doesn’t work?” She recalls an attempt to bring that Colonial Williamsburg charm back to orientation in a weather-proof way, inviting a Patrick Henry reenactor to greet new students and their families following a community dinner. “The problem was that people didn’t stay to listen to Patrick Henry.” After

repeated failed attempts at reviving the event, and concurrent organizational shifts at Colonial Williamsburg, the program “unfortunately just sort of fizzled out.”

The question remains: Who breathed new life into the Colonial Williamsburg Welcome? There are a few key players, Garrett among them. She identifies Amy Ritchie, Community Affairs Manager at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, as the catalyst. “Amy Ritchie reached out to me because she was new in her

role and said, ‘How do we get William and Mary back down here?’ She heard that I worked with new students and wanted to know if there was anything Colonial Williamsburg could do with that.”

Garrett was unaware that the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation had a new hire looking to connect back to the College, but she jumped on the opportunity to reinvigorate new students’ relationship with CW. “As Amy and I were talking, she was like, well, we have an alum who works for CW, who loves to do big events. Let me see if he might be able, come up with something.” This alum happened to be William “Bill” Schermerhorn ‘82, who previously ran the Macy’s Day Thanksgiving Parade for over three decades. He is currently working on the VA250 campaign, designing the events that will celebrate our state’s 250th anniversary.

Regarding the creative process, Garrett recalls, “Bill was like, oh, we could come up with some of this, something like this, and he really took the ball and ran. We talked a little bit about what I remembered from freshman year. We talked a little bit about what fits into the schedule, how much is too much, and what’s not enough. His love for William and Mary and his love for CW just had this perfect kismet moment and made it all happen.”

The brainchild of Ritchie, Schermerhorn, and Garrett, the Colonial Williamsburg Welcome signaled a new beginning for the relationship between CW and orientation; planning is already underway for next year’s big event. “It felt very comprehensive, and we’re looking forward to next year because there is the potential that we can have students tour some of the historical sites, depending on where they fall along the palace. We’re talking about refreshments, like, what can we bring out?” Most importantly for Garrett, the fireworks must stay. “I have to say that was my big ask, is that if we’re gonna ask students to stay down here, we need something. And I think the fireworks were pretty fan-flipping-tastic. I mean, it was a huge show. It was really, really great. And I will say, that has been my biggest request coming back for a second year is, if we’re gonna do this, I think that is a piece that we need to continue because it did really cap off the night so nicely, it did tie a nice a big BANG!

little bow, and it felt really appropriate to what was happening.”

The Colonial Williamsburg Welcome was many things — a fun event to fill an already-packed orientation schedule, a unique experience of the College, a step back in time — but ultimately it marked the opening of a door to new students.

“I know that one thing we’ve talked about is the good neighbor pass, like how do we encourage students to go down and get theirs, right? It takes a little time to process those and do all of that, though, and so that evening, unfortunately, isn’t the night to do that. But it does open up the door for a student to feel more comfortable making their way down there, because if nothing else, it’s a ‘do you remember when we’ moment?”

[Author’s advice: Go get your pass at the ticket office in CW, it’s the best way to escape when exams get you down.]

Our College is special; those who come here belong here and know that it’s special. One of the many things that makes it so is our proximity to and relationship with CW. No other university has what we do. The Colonial Williamsburg Welcome showed our new students exactly that, and I must admit that I see my students from this past year walking in CW more often than any other hall I’ve had previously. The Welcome showed new students that CW is right here! And it’s for everyone — including you! “Colonial Williamsburg is everyone’s place. It’s not just for tourists, it’s not just locals.”

Of similar importance, no other college has a Lauren Garrett, and I would like to thank her sincerely, not only for the chance to ask my questions, but also for the orientation experiences I have been a part of in my past four years. LG — orientation has shaped me from the first moment I stepped on campus, and I don’t know who I would be today without my three years as an OA.

I will miss this university with a depth that I can’t quite put into words, and if I could do it all over again, I would. Flat Hat Magazine has also been an important part of my college experience in ways that I never anticipated, so I extend a

heartfelt thank you to the staff, past and present, for allowing me to be a part of this organization. Disregarding my sentimental senior ramblings, if there is only one thing that you take away from the article, please let it be this: Don’t take for granted what Williamsburg has to offer, because you will find nowhere else like it.

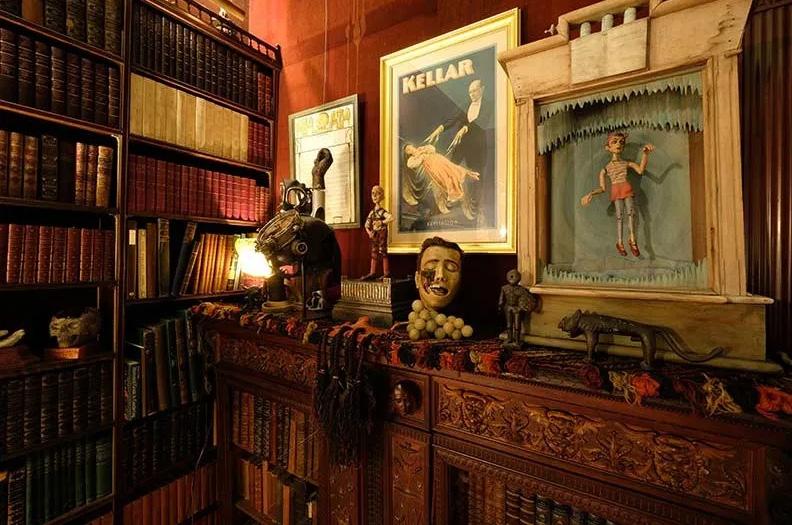

David Crank ’87 is well-known for being a for his work as a production designer on films such as Knives Out (2019). Perhaps less well-known, is that Crank is an alumnus of the College of William and Mary. Andrew Johnston ’25 has a conversation with Crank to learn more.

Knives Out (2019) has long been a favorite movie of mine. It was a major inspiration as we were planning for Flat Hat Magazine’s Fall 2024 issue — so imagine my surprise when I learned that an alumnus of the College had been the film’s production designer. David

Crank ’87 has worked in production and art design for over two decades. Some of his most notable works include There Will Be Blood (2007), John Adams (2008), News of the World (2020), and Knives Out. He has earned multiple honors throughout his career, including an Emmy for ‘Outstanding Art Direction for Miniseries’ and an Oscar nomination for ‘Best Production Design.’

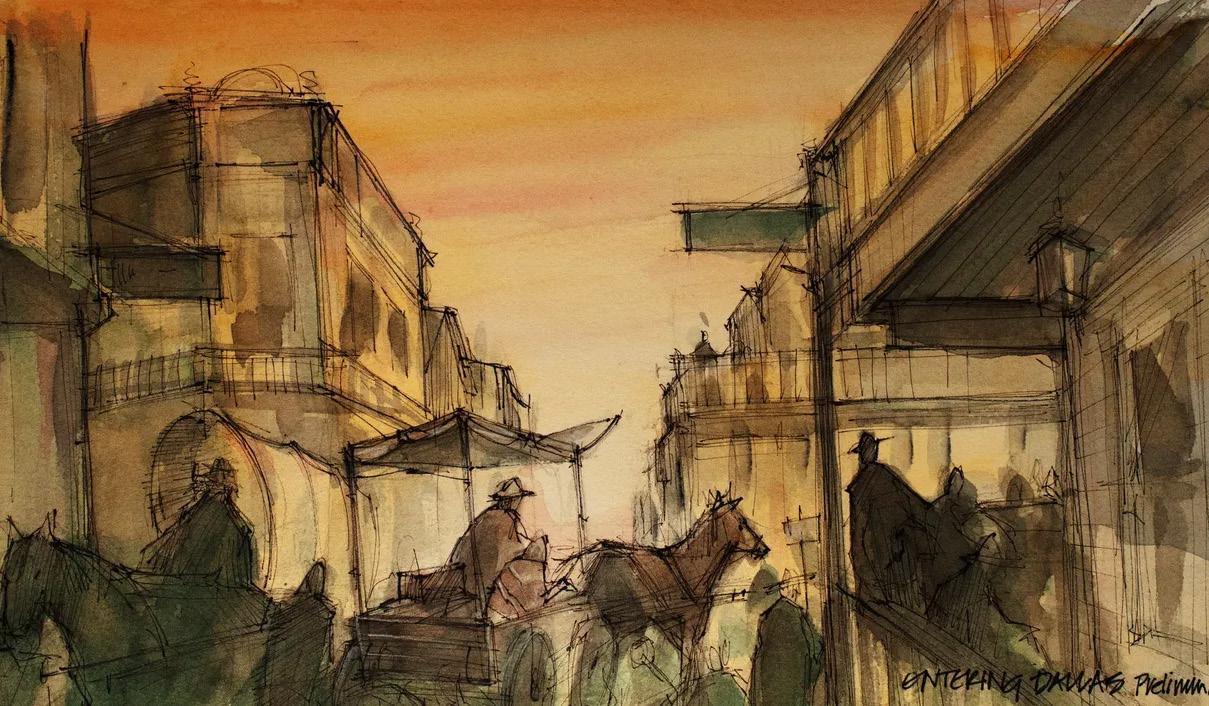

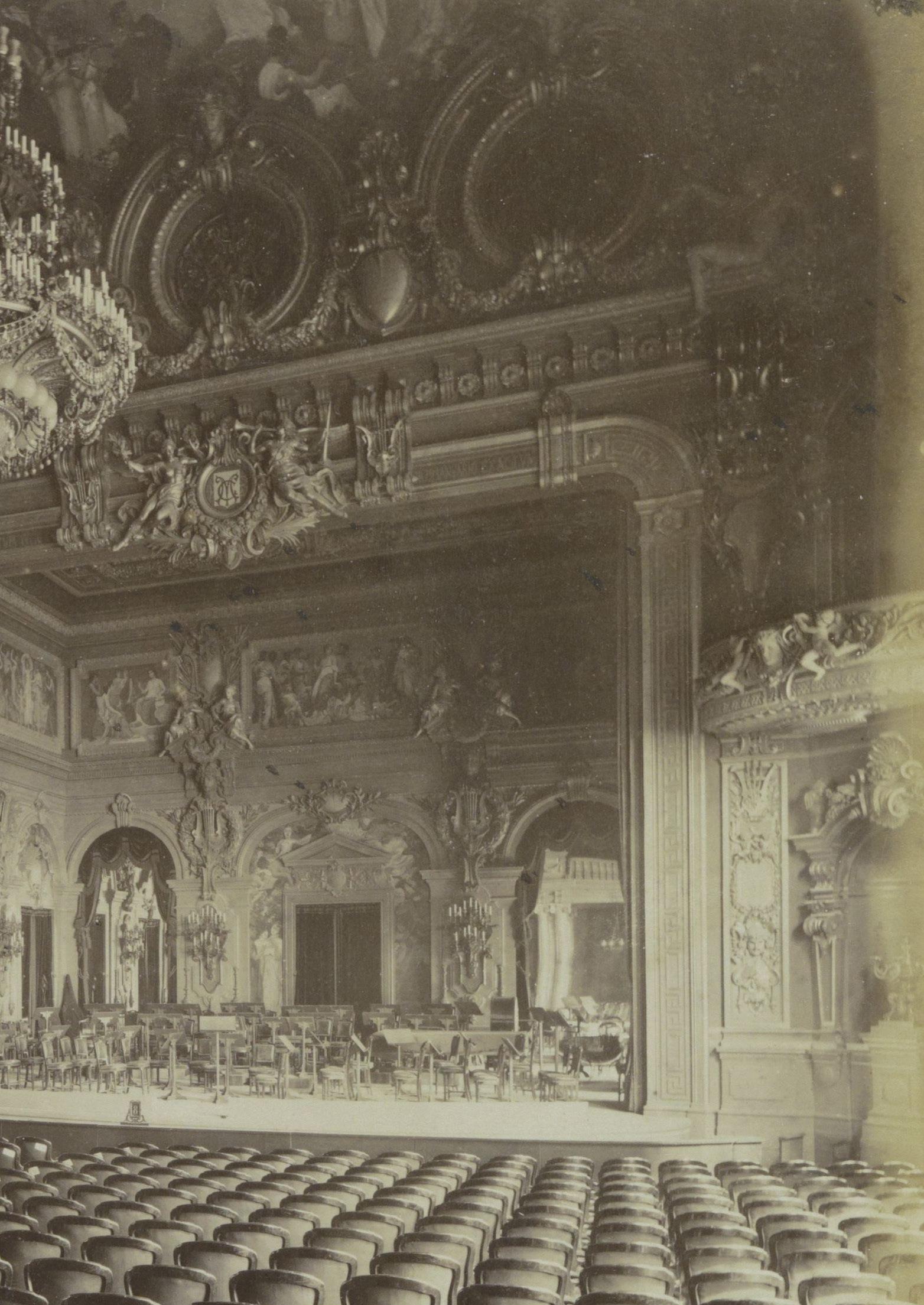

Crank knew he intended to go to the College from a young age. He grew up in Richmond and always had a love for Colonial Williamsburg. His long-held interest in American history is reflected in some of his earlier cinematic work, including projects like HBO’s John Adams.

Q: Could you tell me a little bit about your time at William and Mary?

“I always wanted to go there, even as a kid, and I kind of knew what I wanted to do before I got there. I didn’t have any sort of soul searching at the time because I wanted to do art and theatre. I had

read somewhere in high school that it was best to just study art first — to do theatre, but to get an art degree because you could easily adjust it to working on theater, so I had an art major, and I did theatre. It was a pretty glorious four years. I’m very happy I went there, I really wouldn’t trade it for anything, and I’ve stayed really good friends with a close circle of people that I was with while I was there.”

“What was nice (I noticed once I went off to graduate school somewhere else) is that [William and Mary] didn’t have so much of a house style. They helped you through it, but they didn’t tell you how you were supposed to draw or how you were supposed to do it. They really kind of taught you how to think. Being able to think is the most important thing in my career. You’ve got to be able to draw, you’ve got to be able to design, but you’ve got to be able to dissect the story and figure out how to tell a story.”

Q: Was there a certain project you considered your big break?

“The first really big thing I did was I got hired to be an assistant on a Broadway play. It was for a designer, a very famous woman who had done The Phantom of the Opera before that. The play didn’t go on nearly as long as The Phantom of the Opera did. I was in a very fortunate position — I was the assistant, nobody yelled at me about anything because I was just doing what I was told. I got to sit there and watch, which was incredible. Then I gradually switched. I started as a painter on a film in Richmond, then I became an art director, and then I moved up to production design. I did one or two smaller ones as a production designer, and then I was given a chance to work with a designer named Jack Fisk, who worked in Charlottesville, and he was doing a Terrence Malick film about Jamestown. I worked for about five or six years for Jack and was his art director. It was the people, more than a specific project, that stands out in my head. I’ve been really lucky with the things that I’ve gotten — John Adams was a huge thing here in Virginia that I did for HBO,” said Crank.

Q: Our previous issue was partially inspired by Knives Out, there were a lot of things that stood out to me rewatching it and looking at the background, like the big eyes, or the ring of knives. What are some of your favorite details that you’ve put into your films, not even specifically Knives Out?

“What was nice was that scenery really had a chance to be like the eighth character besides all of those people in the family. You don’t normally get that too much. The scenery is important, but that one really had to tell the story as much as it could, and the thing that was fascinating is that it wasn’t even a house that was their family house. They only lived there for like eight years or something like that. All of it was this thing that he had made.”

“It [the script] just said there was a knife display in the room, that is all it said. We did like four versions of it and none of them were right. That one was the last choice - at the last minute, and when he [the director] came in to look at it, we were like, ‘I hope he likes it because we have no more ideas and they’re shooting this thing on Monday.’ When they go up [the stairs] and there is that painting at the end of the hallway, all it said was that there is a hallway, the door to his office is one way, his bedroom is one way, and there is a painting on the wall. So I said, ‘It’s going to have to be a painting that means something, it can’t just be a painting on the wall.’ We looked and we looked, at first it was a picture of a landscape and we said, well, there’s a window behind it, but then I found that painting of the little boy coming through the window.”

“What was nice was that scenery really had a chance to be like the eighth character besides all of those people in the family.”

“We looked at several [houses], it was so perfect. The only problem with it, the outside was great, the first floor was great, the second floor, the rooms were too little, so all of his office, upstairs, the hallways, those were all sets that we built in the studio. The giant library was another house, because they didn’t have a room that large. Everything had to mean something – you knew that he had bought this house and kind of created it. This wasn’t like a haphazard collection of stuff. It was the other character. Everything in this story is a clue, so if I don’t put it in there, there is no clue. It’s got to be there if it’s in the script.”

“One thing that we had, it hardly got used in the movie, but I think it was one of my favorite parts –a decorator found this giant doll house for like 700 dollars. It was huge, it kind of looked like something from The Addams Family. He said ‘I don’t know what we can do with this but the price was too good,’ and we had that giant library to do and he goes ‘well, what can we make out of it?’ and I said, ‘you know, I think the worst thing you can do with a child’s toy is to make it into a bar so let’s make it into a bar.’ We had all the drinks and stuff inside of each room, but then he took it a step further, and every room that you looked into had these meticulously made murder scenes. There was someone chopped up in

the bathtub, there was someone hanging from the rafters, you never saw any of it, but there were all these little murder scenes as you went around the house and looked in the windows. I would have liked to have had that, but it would have taken up my entire living room.”

Q: Where would you source props for a project like this?

“Prop houses, rental houses, you go to antique stores, antique malls, you go to a lot of collectors. The knives came from two or three collectors – why they had a knife collection I don’t know – but they lent us their whole collection, and we put them all together so we’d have enough knives. You really just start digging.”

Q: How would you describe your signature style, or do you prefer to reinvent yourself for each project?

“I don’t know that I have a style, I think all of us have a handwriting that is there whether we want it to be or not. The nicest thing anyone can ever say to me is ‘I don’t know what you did on that.’ Excellent, then I guess we did it well because you didn’t pay attention to it. That’s exactly, to me, what you want –that it’s so much a part of the story that you just go ‘oh that was a beautiful bedroom’ and just kind of move on. You do have a handwriting, you do things a certain way. Most of the things I’ve done, I’d say three-quarters have been historically related. When I began my career in Virginia, that was what was brought here. More, you are just known for if you’re a nice person, easy to work with, and you don’t go over budget. You hope to be known as having good taste. If I come away with that, I think I’ve won,” said Crank.

Q: How do you balance a director’s vision with your own creative instincts?

“It’s kind of a dance, obviously his vision is always the one you’re trying to go for – he’s in charge. Sometimes they know exactly what they want, and they will tell you very specifically or write it into the script very specifically. That’s the other thing I’ve been very lucky with: every director I have worked with has written a script, and that’s hugely helpful

because if something doesn’t work, they’ll change it for you. You get ideas, you go back, and if you think there is something that they could exploit differently in a visual sense, you’ll talk to them about it. Most of the really good ones want you to do your job. He wants you to step up to the plate and deliver for him. He doesn’t want to have to drag you along. You have to make sure that you are accommodating what they ask for, but I think that’s the interesting thing about working with directors, a lot of your prep is trying to figure out what the framework of the world is because I didn’t know him, I’d never worked with him before, he was very nice to me, but maybe he hates blue. You never know. You need to find out what the world of the movie is, more than real specifics. Once you’ve figured out what that framework is, and it’s always slightly loosey-goosey, then you know how to plug things in. Instead of going up to him and asking, ‘Do you want a blue chair? Do you want an orange chair?’ he wants you to make that choice and to have it work. When they work well, it is exciting because it’s a giveand-take. It’s not rocket science, and it shouldn’t be unpleasant; it should be fun. It’s not about my choice of chairs and dining room table, it’s about how this whole thing works. It kind of requires you to be slightly selfless because it’s a big common thing and I’m a cog in a machine.”

Q: What advice would you give to aspiring production designers who want to break into the industry?

“Study art, study history, and learn how to think. The funny thing is, everyone comes in from a completely different direction. The designer I worked for for five years, Jack Fisk, never did theater; he went to art school, he kind of started on his own as a one-man band doing sets for small things and worked his way up. You just have to try to get yourself involved. Nobody wants to hear this anymore, but you have to not worry about what you’re going to make right up front. You’re young, you really don’t know anything. If you’re excited and you listen, they are the people we’re going to cling to. If you find you like it and you can’t think of anything else you want to do, then that’s probably the thing you should do.”

“I’ve been incredibly lucky, I’ve never had to choose [projects] that were all kind of the same. Every project you start it’s like someone has handed you a big puzzle and you have to figure it out. Nobody hands me the same puzzle every time, which is incredibly nice because you fall back on the same mess quickly if you’re given the same problems. It’s all intertwined with whether or not it was a fun experience and if you were happy with the experience. [For] News of the World, I had a great decorator. I remember we had some wonderful conversations at the beginning, and he kind of let us go and do it. I was very happy with that, John Adams, There Will be Blood. Most of them have been fun and they’re always a different kind of problem to attack. It’s weird, I don’t really have one favorite over the rest of them because they’ve all had wonderful things about them, and that’s what I tend to remember,” Crank said.

One of his recent projects was a 2022 film called Raymond and Ray starring Ewan McGregor and Ethan Hawke; the last film he worked on was The Lost Bus starring Matthew McConaughey and directed by Paul Greengrass, set to release later this year.

Story and Design by Anna Dehmer ’28

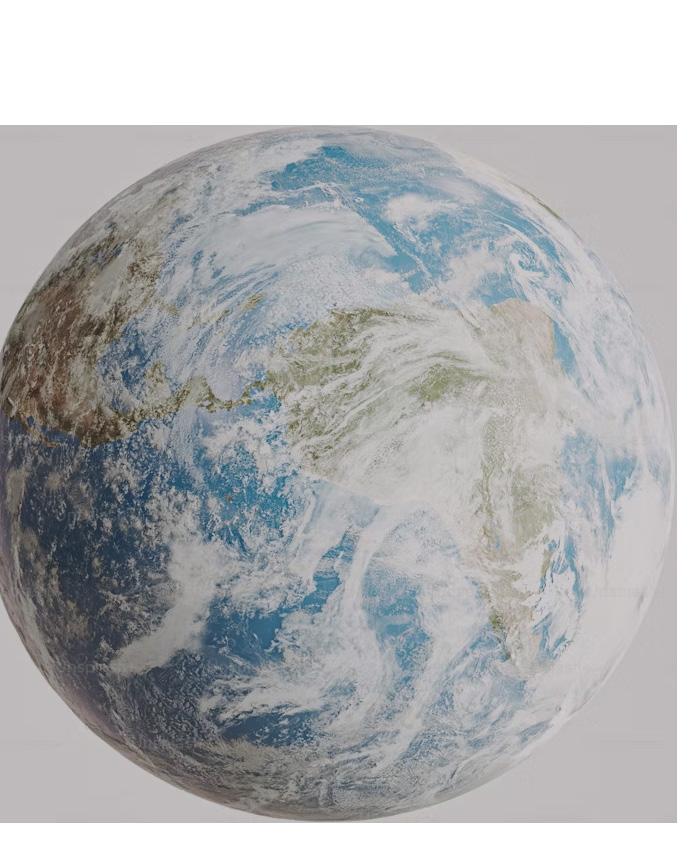

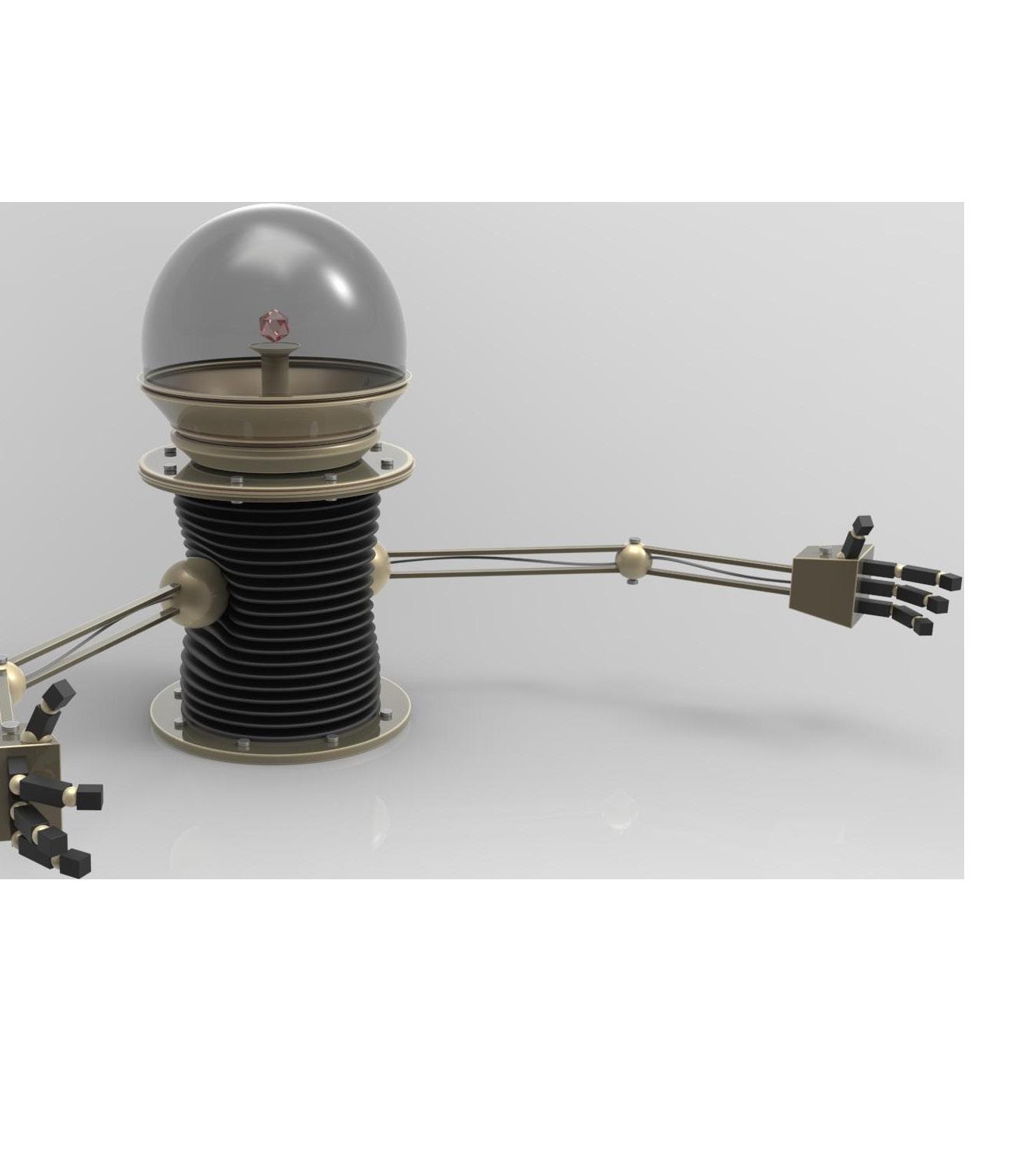

With so many changes happening in our world, it’s hard to predict what will come next. A hundred years ago, we thought we’d have flying cars by now — who’s to say we won’t have a robot-driven society in the next hundred? Anna Dehmer ’28 sits down with professors Daniel Vasiliu and Berhnanu Abegaz to gain their perspective.

We have yet to master the concept of time-travel, meaning it is nearly impossible to know what the state of the world will be in 100 years. Everything within our world is subject to constant change, whether that be the state of the economy, the state of our governments, the state of artificial intelligence, or the technological innovations to come. How the world looked 100 years in the past is vastly different from how it looks today. Because things are constantly changing, the future can seem uncertain. But there is a way to make the future clearer. By sharpening our understanding of the present — and the steps in the past that led us to it — we can power up a time machine and glimpse into the future, making sense of the uncertainty that lies ahead. Two of the most unpredictable forces shaping the future are AI and the global economy. As AI takes the world by storm, it seems as if every company has some sort of AI assistant, and websites like ChatGPT greatly impact how we come across knowledge. Likewise, the economy is in a very pivotal place.

We are seeing welfare states, market economies, and command economies all competing for larger shares of power. Who will win in the end remains unknown. To try and understand the future of these two realms, I spoke with Daniel Vasiliu, Associate Teaching Professor of Data Science, and Berhnanu Abegaz, Professor of Economics.

I first asked Vasiliu about his broad beliefs about where AI may become important in the future. He answered that he believed that manufacturing and assembly would be one of the most impacted areas in the coming years.

“Mass production of goods will be changed massively by AI,” said Vasiliu. So, how exactly will AI improve manufacturing?

“One way this will happen is through discrete optimization of the production process,” he said.

This means that AI will help create faster and cheaper methods for product manufacturing. However, Vasiliu believes AI’s importance in manufacturing is more than in simply planning how things will be made, but in making them as well.

“The second impact of AI is autonomous robots that can perform many tasks,” said Vasiliu.

This inference suggests that robots powered by automated technology will be the ones doing most of the manufacturing, taking the place of many of the existing undervalued human labor.

These robots and other AI technologies typically use large amounts of energy to function. Is increased efficiency worth the environmental costs? Vasiliu sees hope in this reality by believing that AI could be the key towards greater energy efficiency.

“We will see a revolution for advances in solar panels,” he said. Yet, solar energy isn’t the only energy Vasiliu believes that AI could help unlock. “AI will cause big advances in fusion energy,” said Vasiliu. However, that fusion energy will primarily be available to countries that can safely harness AI, and it will not be a universal advancement.

The capability to be the one to control AI rather than AI controlling you is what marks the most important thing in determining whether or not any of these potential capabilities are possible, according to Vasiliu.

He warns that people mustn’t let AI become a replacement for thinking, and as long as we use it as a tool to do what we want rather than simply relying on it to choose what we want, these advancements can happen. It’s a slippery slope, but he believes that ultimately, AI will become the key to unlocking a brighter future.

AI isn’t exclusive to the world of science. Abegaz discussed its importance, but in a different realm: that of world politics. He believes that recently, due to parallel advancements in AI, the Western world has lost its technological dominance.

“China, with about a third of the per capita income of the US, has an AI capability that is comparable to that of the USA — no country has a monopoly over science and technology anymore,” said Abegaz.

The lack of a monopoly behind AI means that it will spill into multiple different industries, allowing it to impact everything. AI will also become incredibly influenced by the industries it touches, meaning it will likely impact the world just as much as the world impacts it. Aside from AI, Abegaz theorized that general economic power will shift from being mainly dominated by Western states into the hands of countries such as China and India.

“By the end of the 21st century, with BRICS plus Indonesia having a lot of room to grow, the West’s share [of the global GDP] will plummet to less than 15%,” said Abegaz. This loss, he theorizes, could be linked to the great increase in nationalism and protectionism in the United States today. We are losing relevance on the global economic scale, and are trying to become the great power we once were.

Shifts in power centers aren’t the only thing to look out for though. Industrialization will likely change its centers towards that of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

“Africa, supposedly an economic basket case, has now achieved universal primary education and will have the biggest youthful labor force in the world in a couple of decades,” he said. “I will not be surprised if Africa becomes one of the spikes of industrialization.”

Industrialization and globalization could look incredibly different. Many of the economic systems we believed were set in stone are shifting.

“The global capitalism that won over socialism is being upended by the call for deglobalization as the liberals become illiberal protections, and the statists allow more room for the private sector,” said Abegaz. Abegaz theorizes that the economic systems of the future are likely going to alternate between globalized and deglobalized, before settling with some sort of multilateral economic order. Abegaz also believes that our individual economic demographics will shift as well.

“Class inequality, which has risen alarmingly fast since 1990, will rise dramatically virtually everywhere,” he said. This inequality will continue to lead to a decline in the middle class, which will loosen the importanceof liberal democracy, and will lead to the creation of uber-rich “global citizens” scouring the globe in search of more wealth.

In general, these professors seem to believe the world will be incredibly different within the next few decades. The way we experience things and the way we live will be vastly impacted by these new developments and shifts in the global power structure. The world is a constantly evolving place, however, and it is impossible to know what lies

Story by Sam Belmar ’27

Design by Clare Pacella ’28

The Highland Park neighborhood did not exist before the mid-1940s. Many of its residents lived elsewhere in Williamsburg or adjacent counties. Williamsburg’s Black community was in many ways thriving after emancipation, with dozens of Blackowned businesses lining the streets of Colonial Williamsburg and elsewhere in the historic city.

William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of History, Melvin Ely, specializes in African American history. Though his area of expertise lies outside of the Williamsburg area, he mentioned that Black commerce began to emerge in Williamsburg in the late 19th century following emancipation, and that Black and White residents could have lived in close proximity.

“In the South, until the mid-20th century at least, it was not at all unusual for there to be a block or a few blocks of Black residents adjacent to an area where White people live,” said Ely.

According to historian Linda Rowe of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, White and Black households were often situated on the same blocks before the Colonial Williamsburg Restoration of the 1930s.

“11 Black households liv[ed] side-by-side with 86 White households on the main street, Market Square, Palace Green, and the Capitol grounds,” wrote Rowe. “Five Black families and 33 White households were neighbors on Francis Street. African American and White families lived on Prince George, Henry, Nassau, and York Streets.”

With grand plans underway to renovate Colonial

Williamsburg into a historical tourism hub, displacing its affluent White residents did not seem to be the answer. Despite the evident challenges of the Great Depression, the city’s restoration chugged on during the 1930s with considerable support from highprofile investors like John D. Rockefeller.

Hundreds of Williamsburg residents, mostly Black, had been displaced from their homes to make room for the new-and-improved buildings. The 1930s marked a steep rise in Williamsburg’s residential segregation and established Black displacement as something of a business strategy for the colonial tourism sector. The City of Williamsburg’s African American Heritage Trail Narrative recognizes these actions.

“About 300 years after the first enslaved Africans landed, a second displacement story was begun when Williamsburg Holding Corporation (WHC) began purchasing property and relocating landowners in preparation for what would become known as Colonial Williamsburg,” the narrative said.

By WWII, little had changed in the playbook. As the United States’ economy geared up for full-scale engagement in Europe, the Navy suddenly needed land to build training camps and stockpile its resources. The Navy coveted the predominantly Black neighborhood of Magruder, ten minutes down the road in York County, as land for a training base called Camp Peary.

In March 1942, Congress passed the Second War Powers Act, facilitating the acquisition of land for military development and calling localities everywhere to action. By September 1942, the first 4500 acres of Magruder had been seized by the Navy and

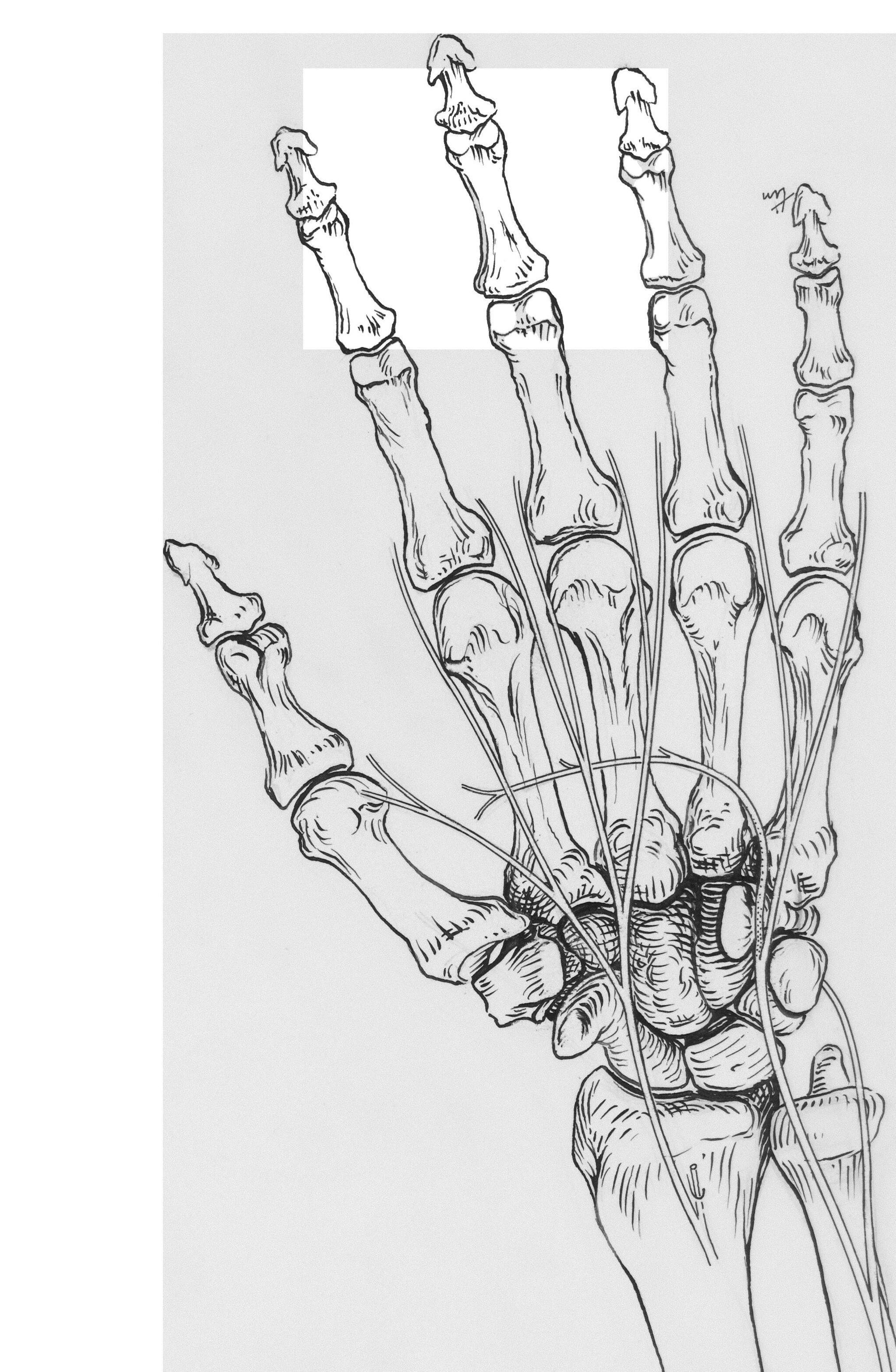

Deep in the ravine at the heart of Williamsburg’s Highland Park neighborhood lies an unknown landfill of rusted metal, tires, refrigerators, old bicycles, glass bottles, plastic bags, and car batteries. Unknown to most of us, except for Highland Park’s residents, they have lived with trash, essentially in their backyards, since as early as the 1940s. Looking at the items left behind offer a glimpse into their lives and histories.

military contractors. Over 100 Black families lost their homes in the following months.

Travis Harris, Ph.D ’19, wrote his dissertation in the College’s American Studies department on the dispossession of Magruder’s Black residents during WWII. He noted that Magruder was not the first time Black displacement had occurred in the region.

“The first [dispossession] is the establishment of the Yorktown Naval Weapons Station in 1918,” wrote Harris. “The second occurred between 1926 and 1934 when the creation of Colonial Williamsburg forced another Black community to leave. The third dispossession — the focus of this dissertation — is the erasure of Magruder with the creation of Camp Peary.”

Harris characterized the Magruder residents’ uprooting as part of an interconnected matrix of dispossession that stripped their community of political, material, psychological, existential, and spiritual selfdetermination. “The former Magruder residents lost more than land,” wrote Harris. “They lost their livelihoods of farming and oystering, and they have experienced a sense of ‘civic estrangement.’”

While the Navy already had a base in Norfolk, the growing demands of the war necessitated another location, much larger this time, which would double the Navy’s training capacity in the area. Harris detailed the timeline of Magruder’s residential displacement and the Navy’s motivations in his dissertation.

“On August 28, 1942, Navy Admiral Ben Moreell wrote to Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy, that the camp in Norfolk could train only twelve thousand men, but by creating the Naval Construction Training Center (N.C.T.C.) in York County, they would be able to train twenty-four thousand men,” wrote Harris. “The process of displacing the residents and building N.C.T.C. took place between September 2, 1942, and June 26, 1943.”

With nowhere else to go, Magruder’s residents migrated away and began to construct their own neighborhoods down the road — Grove and Highland Park. Originally called “Across the Track,” Highland Park belonged to York County when the residents arrived. One resident, Maurice Banks Scott, described the conditions of Highland Park in 1942.

“There was nothing in the area except springs, swamps, snakes, woods, and almost impassable roads,” said Scott.

In 1943 and 1944, Highland Park’s growing community, many more Black residents arrived from the Civilian Conservation Camp, “Tent City,” on the College’s campus, and started developing vital infrastructure such as electricity and toiletry. York County didn’t provide assistance in these efforts. By 1945, their living conditions had much improved.

However, York County failed to provide trash collection services, leaving residents stranded in terms of garbage disposal. Williamsburg resident George Mackert owns two properties in Highland Park. He believes that until Williamsburg annexed the neighborhood in 1957 and started picking up trash as part of the tax base, Highland Park’s residents were sometimes forced to dump heavy-duty waste into the ravine.

“I don’t know if in 1957, they had trash pick-up in their tax base,” said Mackert. “I will tell you there’s less household trash than heavy debris in the ravine.

However, I’ll unearth a full gallon brown jug that says Clorox, a glass jug. And that’s how everything was delivered back in the day.”

It’s unclear where the heavy-duty waste in the ravine today — bedframes, refrigerators, car batteries, old record players, blenders, scraps of metal — originated from. Some might have belonged to Highland Park residents deprived of social services and lacking the ability to transport large items to a landfill. Others might have belonged to outsiders who found the ravine to be a convenient location to dispose of bulk household items.

In the 1970s, another wave of displacement affected Black residents in Williamsburg. Those living in the historic Black business district, called the Triangle Block, were forced out during urban renewal efforts by the Williamsburg Redevelopment & Housing Authority, and their businesses shuttered. Many of them relocated to Highland Park, among other places.

Some of Highland Park’s residents were employed by the College during these years. Mary Esterine Moyler worked at the College’s post office for 34 years and enrolled as a student for two years. As President of the Highland Park Civic Association and the Social Services Board, she worked to expand voting access for Highland Park residents and helped Black students gain access to summer community programs.

In the early 1960s, the Williamsburg Redevelopment & Housing Authority tore down the Union Baptist Church, which then relocated to Highland Park and became a centerpiece of the community.

Historical author Mary Theobald wrote about these demolitions for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s website.

“The Union Baptist

Church was torn down in the early 1960s after its congregation moved to Highland Park, a Black residential area north of today’s Governor’s Inn,” wrote Theobald. “During those years, two of the White City houses were moved to Highland Park. The rest were torn down. Today, one building remains in the old neighborhood, the Mt. Ararat Baptist Church, an island in a sea of parking lots, office buildings, maintenance shops, and warehouses.”

In collaboration with the College’s co-ed service fraternity Alpha Phi Omega, Mackert allowed members to access the ravine through the backyard of his property on Henderson Street. Since 2022, APO has held “Clean the Ravine” events several times per semester to help extract some of the items little by little.

Allie Gibbs ’25 is a sociology major studying APO as an example of community engagement for her senior capstone. For her, the presence of waste in the ravine is reminiscent of the environmental racism that disadvantaged communities often face.

“Going there, it’s always so much more overwhelming than you remember,” said Gibbs. “Just the layers of trash and the sort of stuff that’s there.

But it’s a product of a systemic failure of service allocation, and that’s a major facet of environmental racism. In this instance, with having to pay for trash pickup services or to take your trash to a dump, that’s a difficult thing to do for some people and some communities.”

Gibbs shared that APO leaders are trying to educate their members on Highland Park’s complex history and the constraining factors behind trash disposal in the ravine. She believes it’s essential that members recognize their place at the College in relation to the remainder of Williamsburg, and especially its marginalized communities.

“I think that’s definitely important to round out the community engagement experience,” said Gibbs.

“In general, we’re coming from such a specific positionality as William and Mary students at this PWI in an area that’s very much at face value taken for its tourism industry and its retirement community, and the College. But the area’s been around for a long time, and enslavement and pushing out the indigenous population. There’s such a long history here, and that also comes with a really long history of displacing and harming the Black community.”

Mackert touched on the Williamsburg government’s recent actions in Highland Park. He said that while the City Council proposed a Community Development Block Grant last October to make renovations to the neighborhood’s homes, the likelihood of city officials being able to expend additional resources to assist in cleaning out the ravine is low.

“They’re always interested,” said Mackert. “Did they budget for it? No.”

Mackert underscored the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act of 1988 as an incentive for the city’s future assistance. Mackert worries that if some of the ravine’s trash reaches the creek at the heart of the neighborhood, it could end up in the bay.

“Getting the stuff out of the ravine is the most important part,” said Mackert. “Ultimately, that’s a creek thing. So all that plastic and debris could flow into the Chesapeake Bay.”

In an October city council meeting, Director of Parks and Recreation Robbi Hutton discussed the proposed rehabilitation grant for Highland Park. She

recognized that the neighborhood’s original family owners from the 20th century are gradually leaving as property values rise and gentrification becomes more prevalent there.

“We looked at the numbers, and in looking at the numbers, we saw that Highland Park had a huge increase in the sales and the amount of what the homes were selling for,” said Hutton. “It was a substantial increase where we saw that gentrification was taking place.”

Hutton anticipates that the grant would not take effect for another two years, once 51% of Highland Park’s residents approve the plan and the application can move forward. She also pointed out that rehabilitation grants are highly coveted and difficult to obtain.

“I would say that it would be at least a year to a year and a half, maybe two years, before we would even know if we received the rehabilitation grant, which is a competitive grant,” said Hutton. “So I would say at least 2026-27.”

For now, the future of Highland Park remains to be seen. Recognizing the systemic injustices that led to the neighborhood’s formation in 1942, in tandem with Williamsburg’s second wave of residential displacement and tough conditions that residents endured for decades afterwards, should remain central to the city’s development plans. Highland Park’s story is one of uprooting, hardship, resilience, and community across generations, contributing vitally to the city’s history. Williamsburg should take pride in preserving it the right way.

Story by Jules Nelson ’28

Design by Leah Kohler ’28

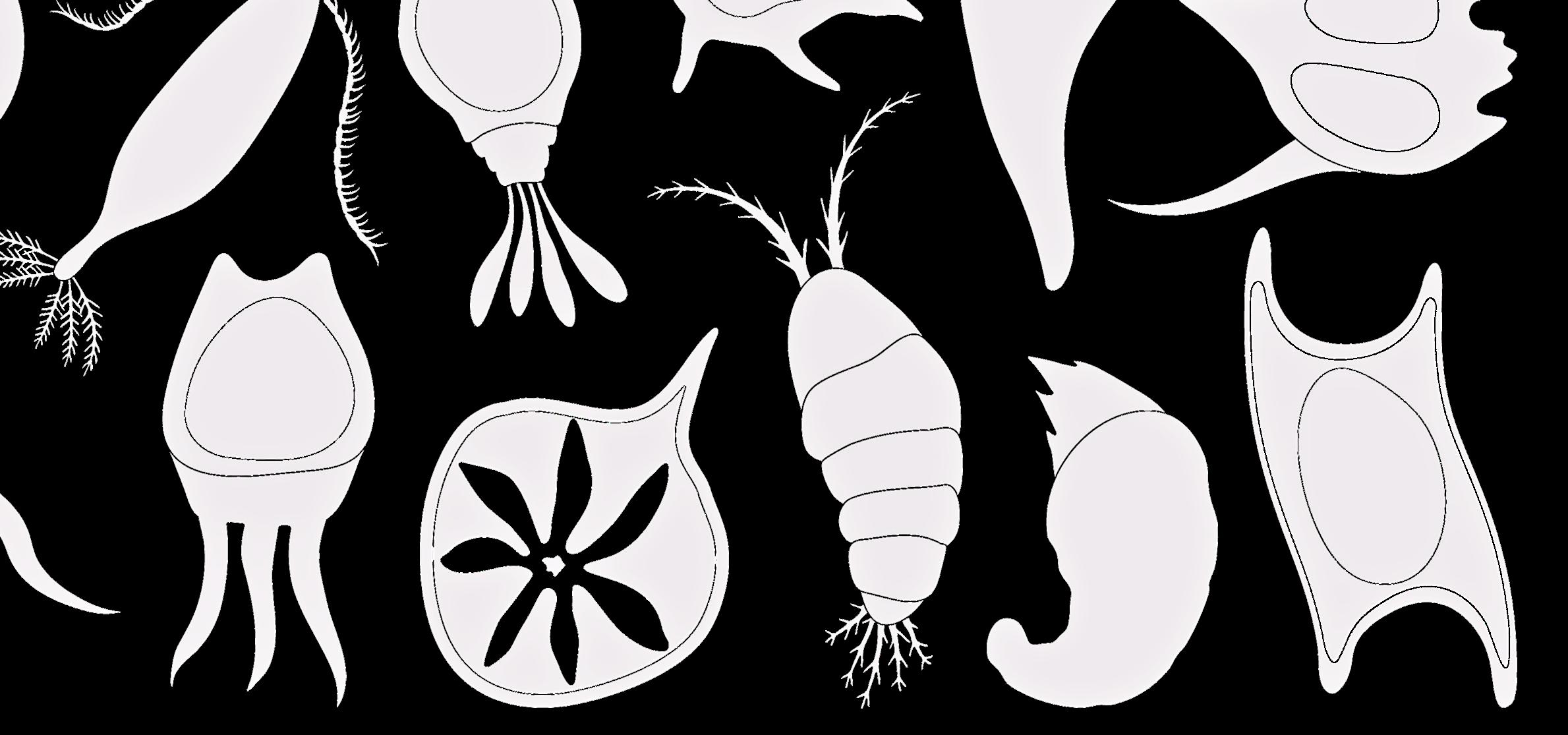

The new marine science major launches in the fall 2025 semester. Jules Nelson ’28 chats with professors at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to learn more about what the major entails.

As many students at the College of William and Mary have heard — especially those who frequent the winding hallways of the Integrated Science Center — Virginia’s first-ever marine science major has been approved. The College’s push to get this major approved gained traction in May 2024, and the process officially came to a close at the end of January, with announcements of its approval sweeping across campus. The demand for a marine science major has been growing in recent years, and the College is now the first school to offer this major in the Commonwealth, making it a leading force, especially in coastal environmental studies. There are a lot of unique things coming into the College with this new major. With the approval of the major, as well as the generous donation of $50 million from Dr. R. Todd Stravitz and the Brunckhorst Foundation, making the program tuition-free, announcements have started to make waves in the student body.

From the beginning of the approval process, there was talk of an “immersion semester,” where marine science majors would spend all of their class time at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science’s Batten School of Coastal and Marine Sciences. For students pursuing a minor in marine science, offered at the College since 2010, a three-credit field course is required to complete the program. While previous field courses will still be offered, the new immersion semester allows students to gain crucial, hands-on field experience without the additional time and cost.

Associate professor and coastal geologist Dr. Chris Hein, who serves as the co-director of the marine science major, is thrilled about the addition of the immersion semester and its ability to introduce students to the field without equity issues. It is also very unique to this major, where a full semester of students’ time is spent off the College’s main campus to learn in the environment they hear about in their lectures. Students will learn about research methods and tools, and then have the opportunity to apply them in the field while gaining real-time research experience. Dr. Hein commented on the semester’s special setup.

“Maybe it’s scheduled, where you have a bunch of classes in one day, or maybe we’re saying, ‘Yeah, we’re taking a field trip today, it’s gonna be all day.’ You don’t have to worry about being back for your next class, we’ve got you,” said Dr. Hein.“Maybe we can just reschedule that class, and now, you have two hours in chemistry tomorrow rather than one.”

The immersion semester will include a field research methods course that teaches students how to collect data, which will be paired with a quantitative skills class. This allows students to collect and analyze samples and data in the field. VIMS officials have made sure the major is fully accessible to students by providing transportation to and from the VIMS campus, so they do not have to miss or work around any classes on the College’s main campus.

“It’s real data we’re going to collect — real science — not a lab that we made up, and we know exactly how it’s gonna work.”

- Dr. Chris Hein, co-director of W&M’s marine science major

Another change happened with the announcement that there would be an application process for the major. This isn’t unheard of — several of the College’s majors require an application process before declaration — but students weren’t notified about the application until quite late in the game. With the major’s specific requirements and perks, including 18 prerequisite credits spanning various academic fields, the immersion semester, and free tuition, making the major application-only is a reasonable choice.

Dr. Hein discussed the application process, which he said is unlike anything students at the College have tackled before. The process is very similar to college applications for high schoolers, but for sophomores in college. Students will be required to submit an unofficial transcript, respond to essay questions explaining their interest in marine science, and provide their cover letter, letters of recommendation, and a roadmap of past and future coursework.

As much as it makes sense for the major to require an application, there have been some concerns among students when it comes to the limited number of applications that will be accepted into the program. Currently, only 10 students will be admitted for the 2025-2026 school year, and over the years they are expecting to cap the program at around 30 rising juniors accepted per year. Claire Powers ’28 shared her reaction to the application.

“I’m not going to lie, the limited number of applicants was a little scary,” said Powers. “I kinda expected there to be some sort of cap on students since this is William and Mary after all, but still, it was so much lower than what I thought.”

A similar sentiment has been expressed by many students who had hopes of graduating with the only marine science degree in the state of Virginia, as the process is much more limited than most had anticipated.

However, students can rest assured that the marine science minor at the College is not going anywhere, and there is even a chance that this program will be expanded. Dr. Hein predicted that with some time and committee discussions, there is a good chance that classes from the marine science major will be added as options for the minor. Additionally, all of the marine science majors’ required classes, with the exception of the immersion semester’s classes, will be taught on the College’s main campus and will be accessible to students who may not be able to join the major.

There are so many amazing new additions that this major is bringing to our school. Dr. Hein provided insights into the workings of the major and the new additions that the College will see with the approval of this major. The addition of a new class called “People, Society, and the Coast” excites him the most. Because the ocean spans so much of our planet, humans can’t avoid interacting with it, and this class will approach anthropogenic interactions with our coastal and marine ecosystems from a social science perspective. VIMS operates as a separate entity from the College, in part due to its place in advising government bodies about how to safely interact with our marine ecosystems. This position allows for classes like this to be taught in a way that applies to the need for environmental consciousness in the world today.

Professor of Marine Science Dr. Mark Brush, who runs the Introduction to Marine Science class, looks forward to what the approval and addition of this major would bring our institution into a new era of what the college can offer its undergraduate students. He’s optimistic about the new connection between VIMS and the College, two rich and diverse institutions. Secondly, Brush is enthusiastic about getting to meet more students who are passionate about the field of marine science. He hopes that he will get to help an amazing, huge group of students get involved, learn more about the major, and possibly even come to work in his lab with him.

“It’s all about the students for me,” Brush said. “It’s about working with you guys. So that’s just super exciting on a personal level.”

The marine science major will bring amazing opportunities to the College and VIMS’ campuses and most importantly, to the education of the next generation of marine scientists that will dedicate themselves to preserving a critical piece of our planet.

Starting at 6, 7, 8, 9PM

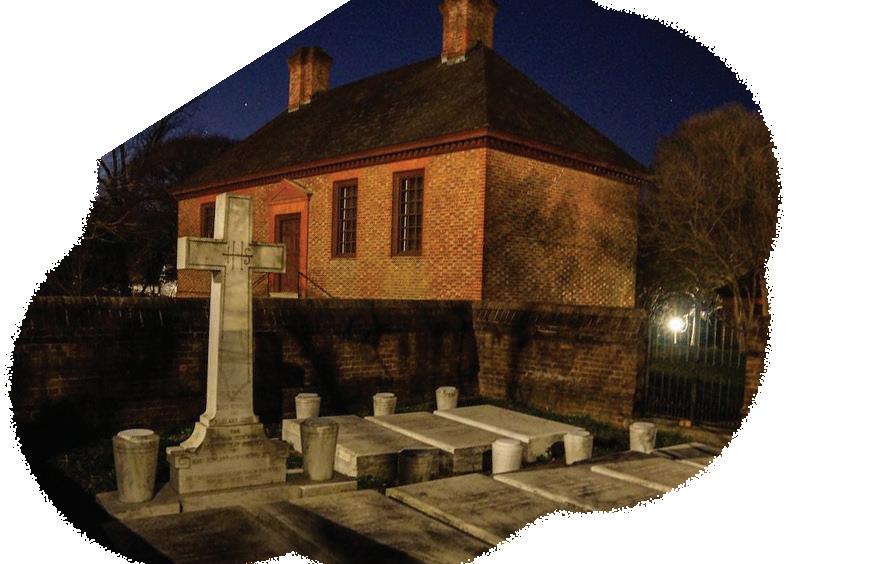

The original Colonial Ghosts tour is a fresh take on old hauntings. Authentic, chilling, and unforgettable—experience the eerie charm of historic Williamsburg’s most haunted locations and stories.

Starting at 5:45pm - 2 Hours

Sip spirits and share scares on Williamsburg’s hottest adults-only tour experience. Enjoy your favorite drinks while uncovering ghostly tales at the coolest colonial hotspots. Fun, racy, and more than a little spooky—it’s the ultimate boos and booze bash. (21+; alcohol sold separately.)

Starting at 10PM - 90 Minutes

Step deeper into the shadows to uncover Williamsburg’s dark past. Crank up the intensity on our exclusive late-night ghost tour featuring new haunted locations and darker stories you won’t hear anywhere else. Book

Starts at 11:00pm - 2 Hours

Embark on the ultimate bone-chilling experience in the dead of night. Equipped with the latest ghost-hunting gear and armed with an adventurous spirit, explore Williamsburg’s most haunted sites to encounter ghosts from centuries past.

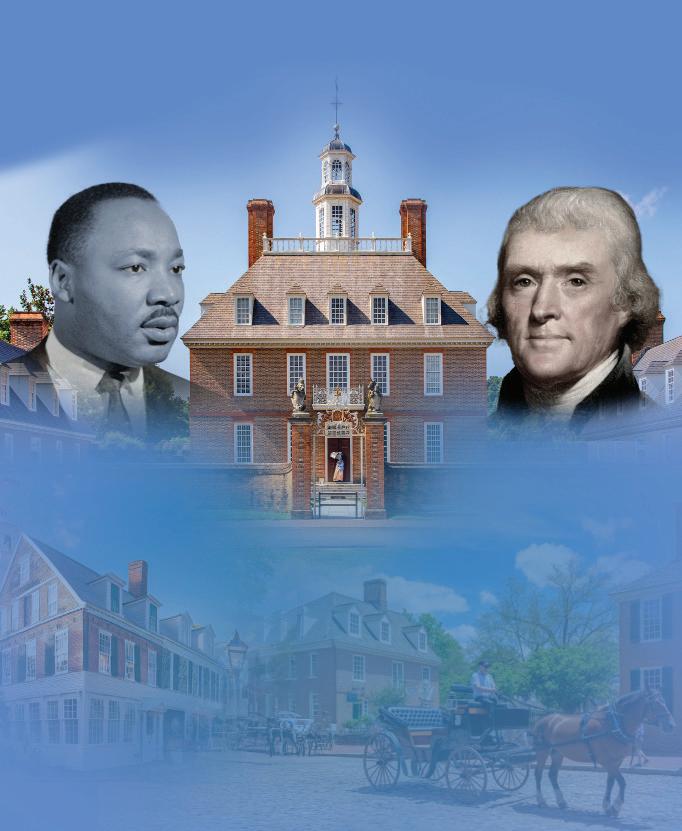

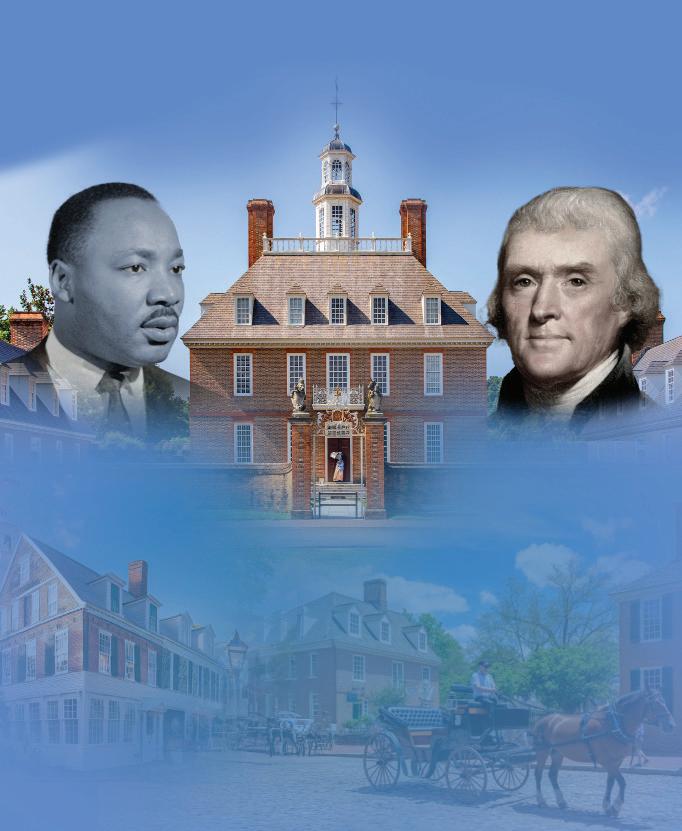

Explore Williamsburg’s history of African-American founders with true stories and artifacts, highlighting hidden contributions that built America. Stand in one of America’s oldest black churches to ring its historic Freedom Bell. Tread in the footsteps of black visionaries who transcended bondage to forge a brighter future for all.

SHALL OVERCOME: WILLIAMSBURG BLACK HISTORY EXPERIENCE Join Williamsburg’s adventurously delicious Taste of Williamsburg food tour! Dive into history while savoring delicious bites from local eateries, including rich chocolate, mouthwatering tacos, the world’s best mac and cheese, and more.

by

Anna Dehmer ’28

One of those tiny resin ducks. I find them around campus all the time and I want people to keep on finding them well into the future.

- Portia Dai ’26

A letter to my future self with pictures of my proudest accomplishments to date!

- Emelia Marshall ’25

An issue of Flat Hat magazine, of course!

- Andrew Johnston ’25

One copy of every Mag issue during my time at the College, as well as newspaper. Maybe some Minecraft merch since the Minecraft movie just came out?

-Peerawut

Ruangsawasdi ’26

All of my Barbie and Twilight DVDs with a DVD player, face masks, and plug-in headphones.

- Sophia Kaisermann ’27

A list of all of my current liked songs and playlists on Spotify, so I can go back and see what I was listening to!

- Grace Ki Rivera ’26

A rainbow among us pop it - Clare Thomas ’26

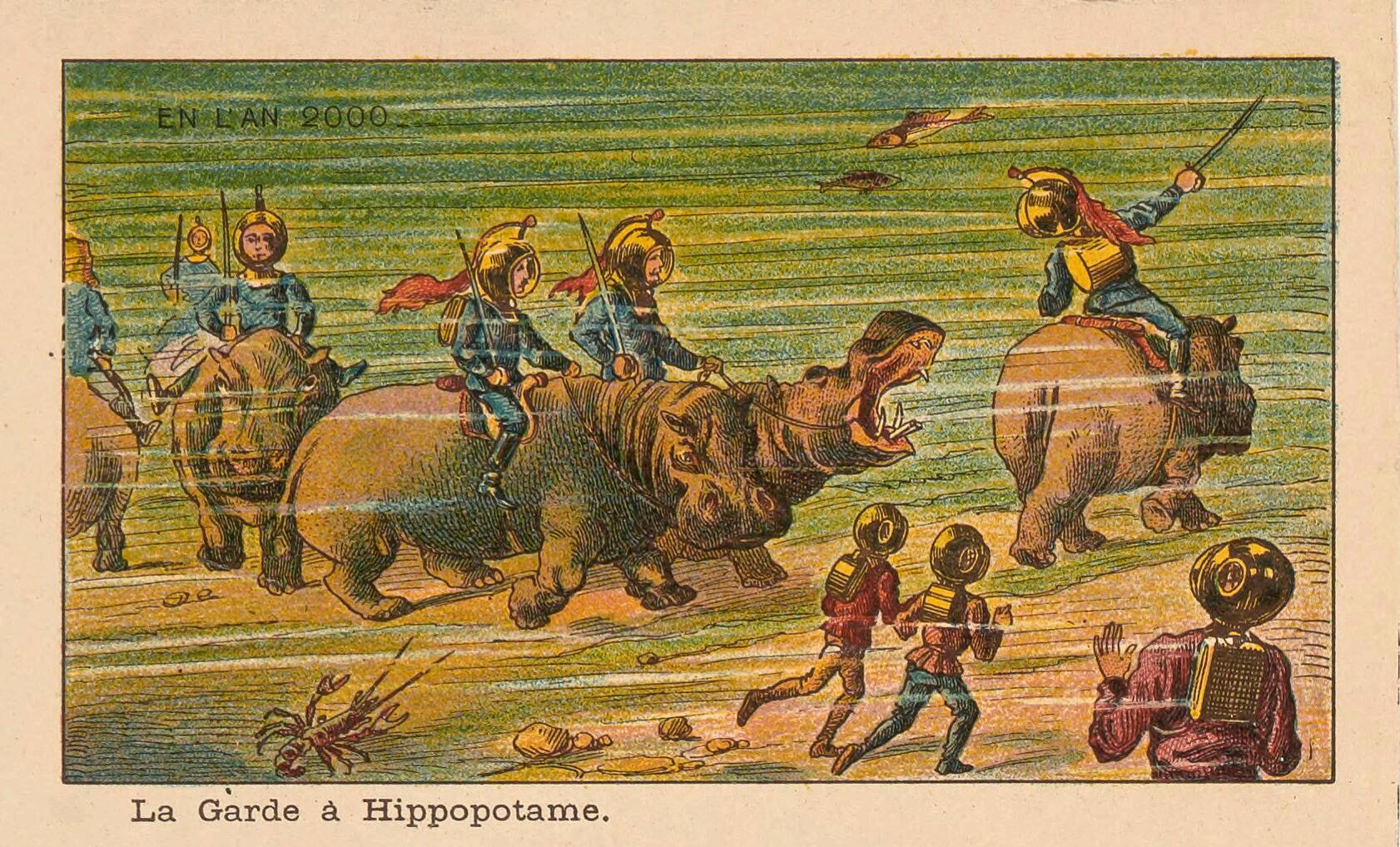

the cards sat untouched until 1986, when they were republished under the title Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000.

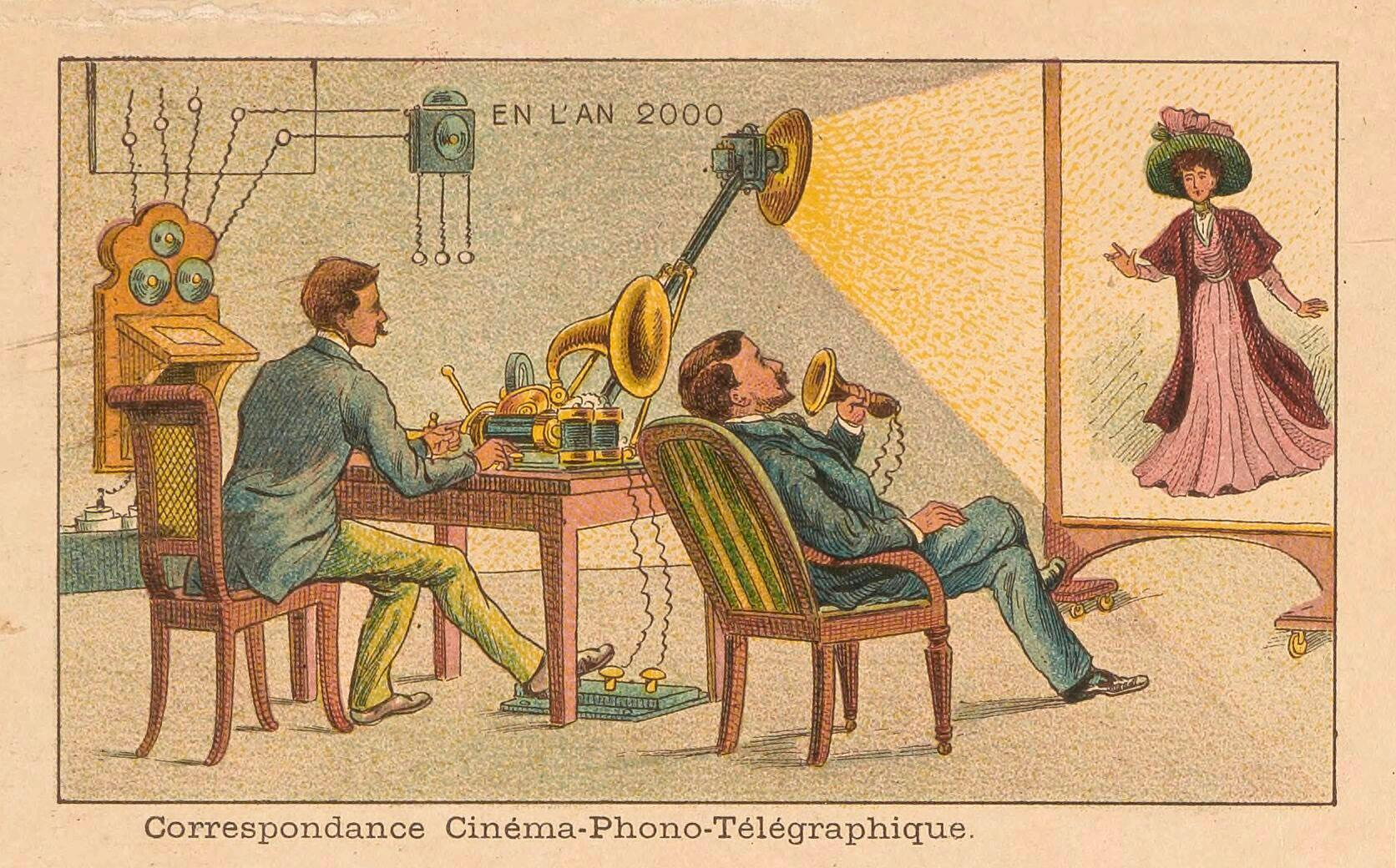

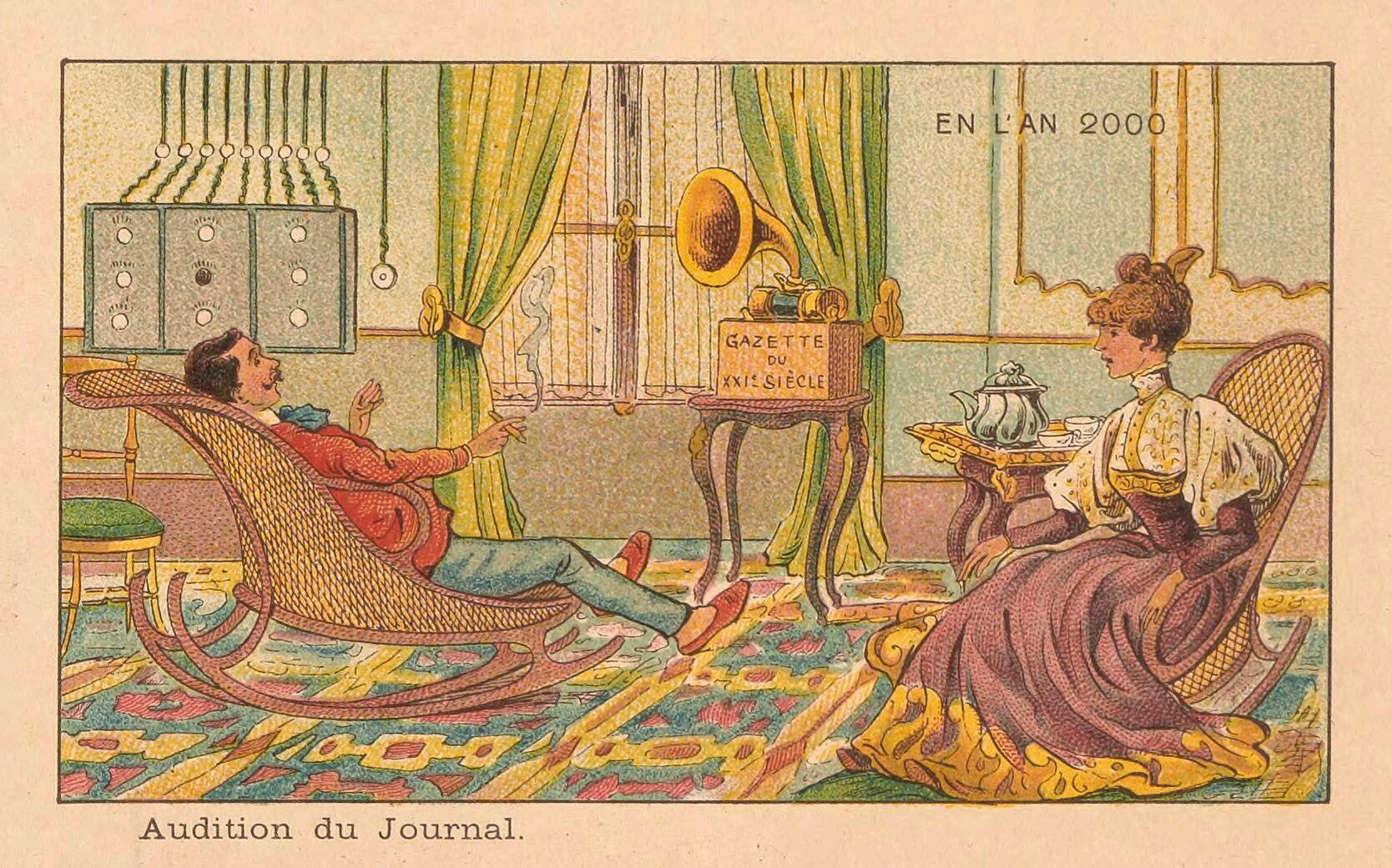

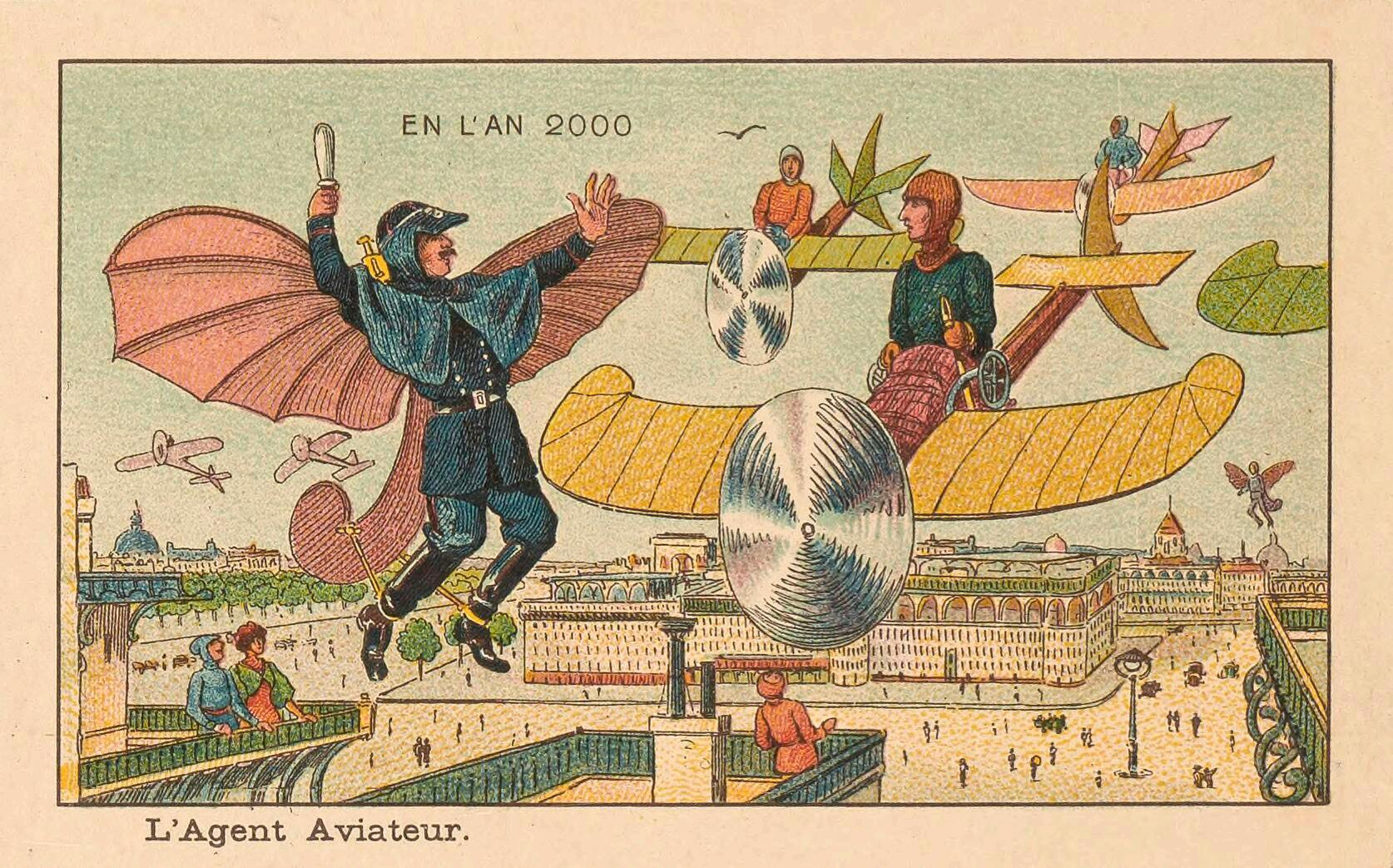

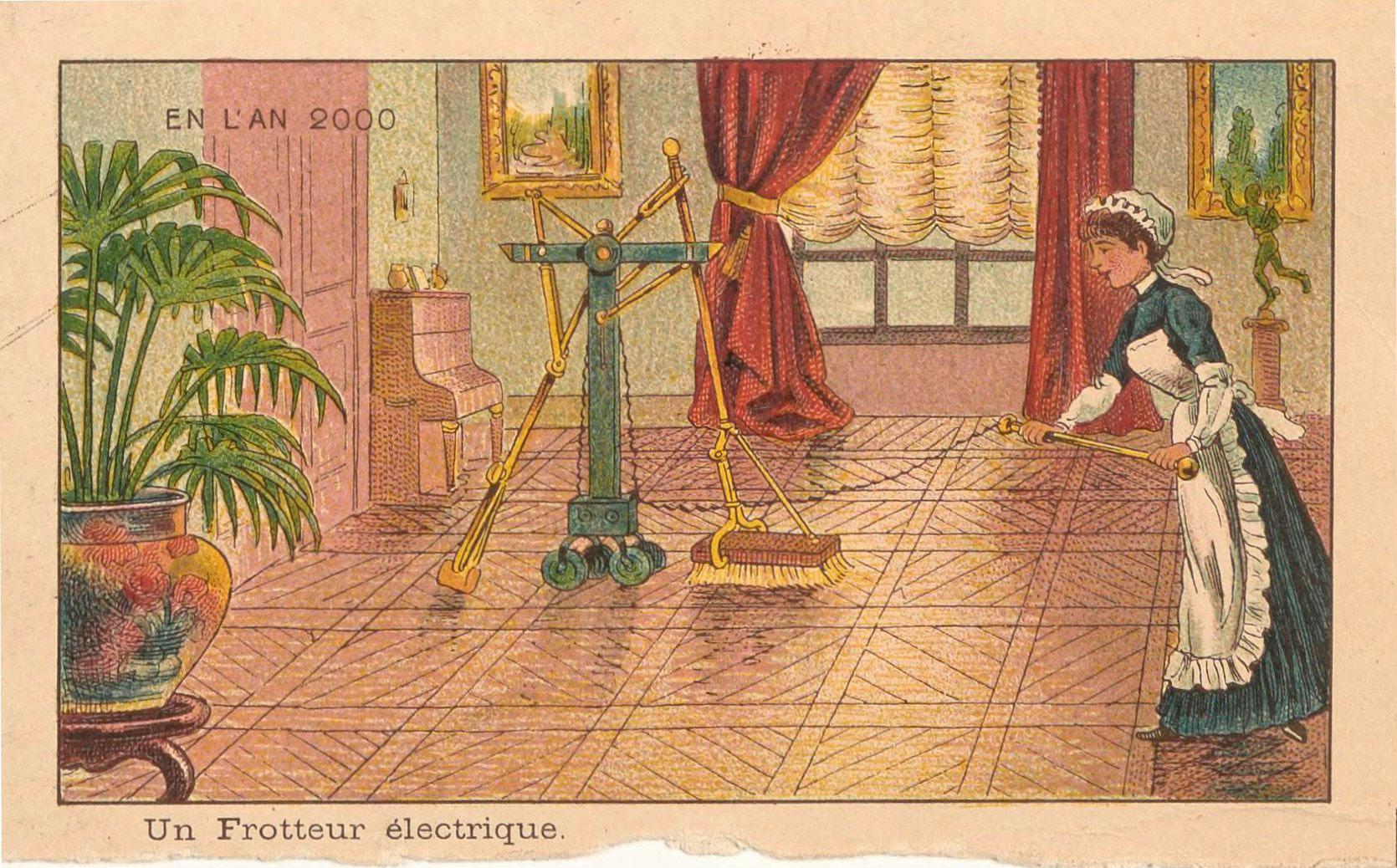

25 years after the 21st century began and a quarter of the way to the 22nd, I took a deep dive into Côté’s work to see what was achieved before 2000, what has been achieved since then, and what remains a vision of a possible future. Here are some of my favorites.

Cinema-Photo- Telegraphic Correspondence

Video calling technology has been around since the late 1920s, but it was not an instant success. Similarly to other technologies at the time, many people doubted its value. As a result, the devices introduced were not popular enough to make waves in the mainstream market. That is, until 2010 and Apple’s release of FaceTime. Taking into account the vast number of technological advancements made since 1900, Côté’s prediction is fairly accurate.

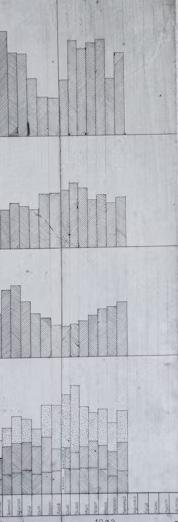

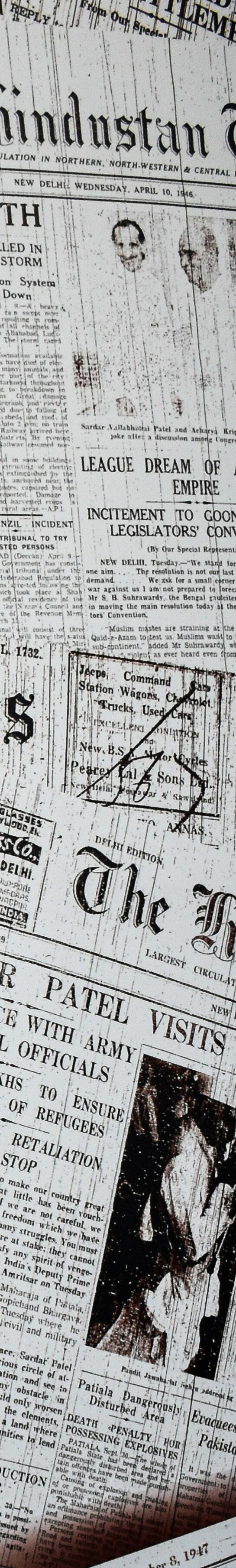

Radio made its debut in 1895, transmitting morse code to a receiver over a mile away. However, many people were still skeptical as to whether the technology would amount to anything of value. When Côté created this drawing in 1900, being able to hear the news from long distances away remained a futuristic concept. After the first radio news broadcast occurred in 1920, owning a radio became a vital connection to the world. Accordng to the Pew Research Center, in 2000, 43% of Americans received the majority of their news from the radio. That percentage has seen a sharp decline in the past 25 years with the percentage now at 6%. Conversely, with the rise of the internet, the number of people who get their news from online sources has continued to increase. In 2000, the percentage was 23%. Since then, it has more than doubled at 58%. In addition to those sources, 32% of today’s Americans get their news from cable programs and 4% from print newspapers. What was once a far off vision for the future, radio has both risen and fallen in popularity, making way for newer, more innovative technologies.

It’s hard to think of a vision for the future that does not include flying cars, and subsequently, creative ways to police them. While we are not yet an aviation-based society in our everyday comings and goings — airplanes are not as predominantly used as cars — the development of flying cars remains a common goal for those in the auto industry. Maybe they’ll be around in 2100?

Just barely making the 21st century cutoff, the robot vacuum was invented by Electrolux in 1996. However, the technology was far from perfect, nor was it flying off the shelves. It took until 2002 with the introduction of the Roomba for robot vacuums to become a common fixture in American homes. Even though it is not a perfect cleaning method, the time that is saved adds up. According to iRobot (the company that developed Roomba), the vacuum can save up to two hours per week and 110 hours per year. While not necessarily the electric brush that Côté imagined, it comes very close and has become a valuable tool in completing daily chores.

It’s unclear whether being on the backs of hippopotamuses would make fighting easier or harder, but it would definitely make it more interesting. Are hippopotamuses used as a weapon or just a mode of transportation? Does the battle need to be taking place underwater? How many hippopotamuses would an army need? Would other unconventional animals find themselves facing warfare? There are so many questions, but I’m afraid we have yet to find answers.

Story & Design by Sophia Kaisermann ’27

Brian Castleberry, Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing, recently published his second novel. Sophia Kaiserman ’27 sits down with Castleberry to learn more.

Frequent visitors of St. George Tucker Hall will be familiar with the first-floor shelves displaying faculty-published works. This semester, a new release joined the line-up: The Californians, a novel by Brian Castleberry, associate professor of English and creative writing.

Castleberry first became interested in writing while playing in his high school band. His passion did not lie in playing the bass, but rather in songwriting

“That didn’t really go anywhere,” said Castleberry. “But it definitely got me interested in writing, and especially poetry.”

He began performing beat poetry in coffee shops after graduating from high school. His passion for poetry led him to explore mid-century authors like Kurt Vonnegut, until he decided to pursue prose and study creative writing

“I did that for a while and really thought that I was gonna be a poet. And then the call of storytelling, you know, I kept coming back to it. And I was like, no, I really want to be a novelist one day,” said Castleberry.

Once at school, Castleberry studied under Toni Graham, a demanding creative writing professor who continually challenged him and saw his potential.

“She really changed my life. She made me into a writer,” he said.

After graduating from college, Castleberry pursued graduate study in creative writing, and his thesis was the first iteration of his debut novel, Nine Shiny Objects. He was fascinated by the 1950s.

“I just thought it was such a weird time,” said Castleberry

The story had the same premise as the now published work: A group of people decide to create a utopian society after they hear about a sighting of flying saucers across the sky. A decade after the first inception, however, Castleberry returned to the story, expanding its scale.

“I wanted to create this set of characters that were all ... interconnected with this dream of what America could become.”

The result? A novel in nine chapters, each following the intertwined lives of nine characters over later decades of the 20th century.

The Californians, which was published in March 2025, follows a similar structure, this time rotating between three main characters. In this novel, Castleberry draws inspiration from his favorite authors, like Charles Dickens, Leo Tolstoy, and Thomas Mann, who wrote comprehensive sagas with substantial

page counts. These wordy epics, however, are often not as popular among modern readers.

“A way around that and a way to create that epic scope is ... if I let these characters kind of build a structure ... have them have their stories. For the reader, that connection between the characters gives it that giant, epic feel. Then I can do both,” said Castleberry. “I can do something that reads in that more kind of contemporary way, but that builds a world that is that big ... that can be about historical change.”

This style also has the benefit of m irroring life in the digital age. “It’s hard to think about the world around us in a way that’s not interconnected.”

Even with a familiar narrative structure, writing his second novel had its own set of challenges.

“What people don’t tell you is that the second book is an incredible amount of pressure because all of a sudden you feel like you have something to prove,”

Castleberry said. “... You don’t really have to prove anything, but you tell yourself that.”

“I don’t feel like I want to do anything that is not trying to do the biggest thing that I can do, the most signi icant thing that I can do with my life and my work.”

Once over the initial expectations, he gave himself the freedom to write a story on a larger scale.

“I always have fun writing, but I really kind of let myself loose to a certain point and said ‘discover whatever you can,’” he said.

A larger scale also led to a larger page count, with the first drafts being 650 pages, which he, together with the editing team at Mariner Books, was able to cut down to its now 380-page total. Despite the length, Castleberry’s editor, Katherine Nintzel, encouraged him to explore the possibilities and write the story he wanted.

“She really cheerleaded me to keep discovering more of the story and go with it,” he said. “That’s the person who is your champion and is the one who you most have to trust.”

This support from the team at Mariner is vital, giving Castleberry the freedom to write stories that he feels passionate about.

“I don’t feel like I want to do anything that is not trying to do the biggest thing that I can do, the most significant thing that I can do with my life and my work,” he said.

He made a conscious decision to make the subject of his writing America, and although The Californians spans the 20th century, the book provides commentary on the country today.

With the book edited and ready to be published, Castleberry was excited to attend book events for the first time. Since Nine Shiny Objects was released in 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, all events were online. This time around, he would meet readers in person, including at a reading of The Californians at the Ampersand International Arts Festival at the College of William and Mary

Now that The Californians can be found at bookstores all over the world, Castleberry has moved on to new stories. One of these is a big project about his home state of Oklahoma, with his signature expansive time scope and large cast of characters. Another is a smaller piece with only one main character, he is hoping to “keep it simple.” In the meanwhile, he is looking forwards to reading new books and for the next Mission: Impossible movie.

WALL-E (2008)

So poignant, so important in this day and age. I hope it inspires future generations of environmentalists. Every classic needs a bit of nostalgia, and WALL-E masterfully blends an apocalyptic setting with the golden age music of Hello, Dolly!

-Sophia Kaisermann ’27

(2022) -Lelia Cottin-Rack ’28

Hot take, but Bullet Train. It’s an amazing action comedy with stunning visuals, you should give it a watch if you haven’t seen it. -Andrew Johnston ’25

We asked Flat Hat Magazine Staff what movies they think will be classics in 30 years. They answered.

Thomas ’26

5625 RICHMOND RD (F120) WILLIAMSBURG, PREMIUM OUTLETS

&

5711-83 RICHMOND RD WILLIAMSBURG, PREMIUM OUTLETS

Local Artisans' Treasures, Antiques and AccessoriesSomething for Everyone

Story by Emma Halman ’26

Design by Alex Hill ’28

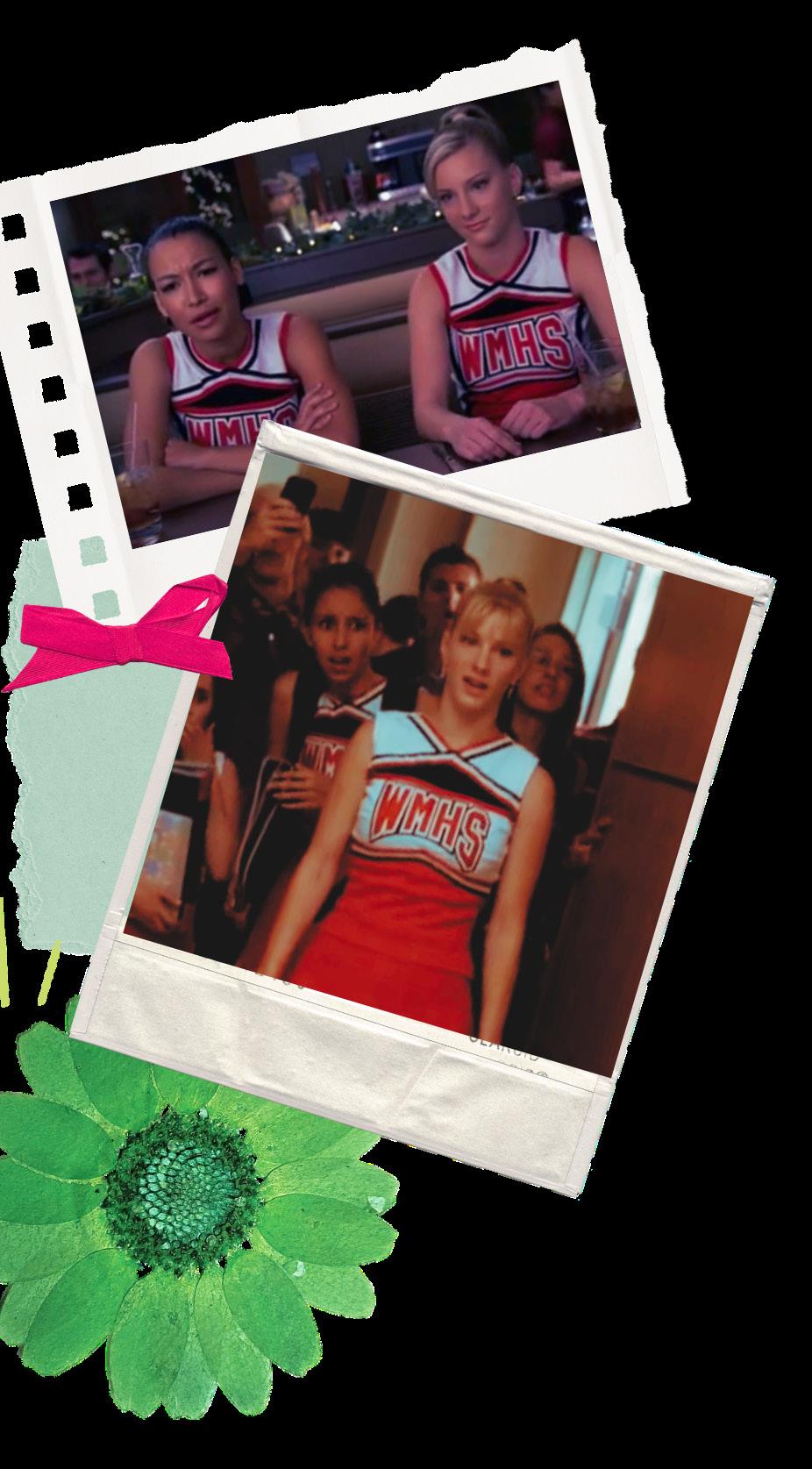

The “dumb character” is an ever present archetype used widely across film and television for comedic effect. Emma Hamlan ’26 explores how Glee’s Brittany S. Pierce’s portrayal of the “dumb character” allows the show to expand its perspective.

“Dumb characters” can become a onedimensional version of their original inception by the time a show gets to its final season. Fans of a show often criticize this lack of character development, as it devalues the opportunity for growth that is unique to a character who challenges the status quo.

So, let’s talk about Brittany S. Pierce.

As someone who is currently dedicating a lot of my free time to rewatching the cult classic Glee, I’ve started to notice more of the complexities of Heather Morris’ character that viewers might miss on their initial watch of the series. Along with her naivety and iconic one-liners (My personal favorite is “Stop the violence”), Brittany offers emotional depth and honesty that other members of the Glee Club rarely show, while still reflecting the “dumb blonde” stereotype that gives her character its comedic weight. Alongside Quinn Fabray (played by Dianna Agron) and Santana Lopez (played by Naya Rivera), Brittany is introduced as one of the three Queen Bees of the McKinley High School

cheerleading team, the Cheerios. While Morris’ character fulfills a minor role in the first 22 episodes, most often seen rolling her eyes at Lea Michelle’s Rachel Berry, Brittany became a series regular in the show’s second season, and the rest is history. Brittany’s comedic value comes directly from her role as the “dumb character.” Her complete obliviousness to social cues allows her to exist between the boundaries of realism and absurdity, creating a unique sense of humor that fans of the show quickly latch onto. For example, if the line “I’m pretty sure my cat’s been reading my diary” was said by another character, the audience’s reaction would not be laughter but confusion. Brittany’s character, however, works so well because she can make outlandish comments that the other characters don’t have access to.

Despite her lack of common sense, Brittany is often the most honest, open, and emotionally knowledgeable character on the show, even if she doesn’t always grasp academic or traditional forms of intelligence. This can be seen in her relationship with Santana, where Brittany’s emotional maturity and self-awareness often contrast with Santana’s more “intelligent” but emotionally guarded nature.

In Season two, Episode 18 (“Born This Way”), each member of the Glee Club is challenged to search for self-acceptance by wearing a T-shirt with an insecurity written on it during a performance. Prior to this assignment, Santana had recently come to terms with her lesbian identity and expressed her feelings for Brittany. In response, Brittany encourages Santana to wear the shirt she made that says, “Lebanese.”

After Santana refuses, Brittany delivers wisdom with the line, “I do love you. Clearly you don’t love you as much as I do or you’d put this shirt on and you’d dance with me.”

This tender moment effectively subverts the audience’s expectations for Brittany’s outlook on life. By creating another layer to her character as the show progresses, Brittany continues to evolve her unique perspective and escapes her trajectory as a flat character.

In fact, this strong emotional intuition often aligns with Brittany’s more credulous moments, such as when she asks a shopping mall Santa Claus to make another character’s legs work again, and fully believes that her wish will be granted. It’s Brittany’s usual “dumbness” that makes her moments of insight so memorable.

This combination of emotional intelligence and comedic obliviousness is what makes Brittany such a beloved character. By offering more than just simple humor, her growth over the series is a testament to the show’s ability to defy the typical arc of the “dumb character.” Rather than becoming a stagnant figure, Brittany’s complexity is revealed as she demonstrates the depth of her understanding and emotional maturity, making her one of the most memorable and well-rounded characters on Glee. This duality shows how even the “dumb characters” can offer significant emotional depth when they are allowed to evolve beyond the confines of their original roles.

My friend — who wears firetruck red lipstick, blasts fantastic music, and once drove all the way to West Virginia accidentally — frequently throws her hands up and announces, “What a time to be alive.”

She says this as she drives with her windows down, sunglasses on, hair flying. The words and tone don’t change, whether the context is despair, excitement, or the utter bizarreness of humanity. The phrase always fits, ideally framed with a dramatic sigh, summing up this weird world and weird age. Since remarks on the odd world could wallpaper every building on the College of William and Mary campus and still not be exhausted, I thought I would reflect on the weird age.

Psychologists describe this phase of limbo in wealthy countries like the United States as “emerging adulthood.” It occurs between living with one’s parents and “settling” into traditional adult roles, such as a long-term job, marriage, and parenthood. In the book Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties, Jeffrey Jensen Arnett describes this stage of life as “an extended period of exploration

and instability.” Simultaneously, emerging adulthood encompasses the thrill and worry of the unknown.

For me, imagining the idea of a lifelong commitment to a company, placing a down payment on a home with a spouse, and starting baby prep by 21 is a one-way road to flu-like symptoms. Seriously, I’m sensing nausea and a fever coming on just writing that sentence.

Plus, as the elderly cynics love to say, “in this economy,” it’s impossible. It’s about as easy to find an internship as a gold bar. Double digit coffee prices sap the money we are supposed to be saving for a home. Heck, getting married was a lot easier before ghosting was invented. No wonder financial dependence, to some degree, is extended. I know that the day I turn 26, I will hold a funeral for my parents’ health insurance plan.

I have not even picked a major. The “full weight of adult responsibilities,” as Dr. Arnett calls it, seems about as distant as the galaxy Star Wars is set in. That is, far, far away.

“Emerging adulthood” brings an impalpable unease with it, a discomfort of growth that hasn’t quite solidified enough to become permanent or integral. It is present but just out of reach. When I’m home, I feel a little out of place, like I know I’m different from the last time I was there, but I can’t quite pin down how. Maybe I have new edges or gaps, or maybe the empty space left behind has altered, squished, or remolded.

The movies don’t help. See, I’ve attempted to study up on the phenomenon of coming-of-age. I’ve watched Lady Bird, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, The Breakfast Club, and Never Have I Ever. But the picture cuts off with high school grad caps flying into the air (or perhaps a brief snapshot of college life), signifying that adulthood is no longer coming. It has arrived. The credits roll. The viewers shuffle out of the theater, pit-stopping at the snacks counter for a last free refill.

Well, what the heck, Hollywood? Way to make me feel like a bum for not having “Character Arc Complete” stamped on my diploma. I feel like I was supposed to have Vol. 1: Growing Up all wrapped up last June, but the film reel just kept spinning. Maybe it will spin forever.

up, to call it revolting because it is not the blazing heat of summer or the dreary cold of winter. The slow shifts spring entails are incredible in and of themselves.

So, adulthood may be taking its sweet time emerging. You may be trapped in a ferocious, grueling state of in-between. Yet, change is beautiful, in and of itself. It does not come with a 2x speed option, leaving us with a choice: to despise the uncertainty or to cherish it. The latter sounds a lot more fun.

“What a time to be alive,” a dear friend remarks on many occasions. The phrase always fits. The world seems a stumble away from falling apart. Yet, her words never feel sad. I think it’s the miraculousness of the last part: “to be alive.”

Since we are alive, we have the ability to act on this time, to create impact, to shake things up. As “emerging adults,” we may be on the brink of a quarter-life crisis. But we are also on the brink of possibility. We can confront this time. We can embrace limbo, we can celebrate the confusion, we can welcome the verge.

“What a time to be alive.” Windows down, sunglasses on, hair flying.

Change is confusing, unsettling, unpleasant, and painful. While this existential tirade could very well end there, I wouldn’t be honest if I weren’t a tad cheesy. We’re talking cheddar, feta, brie, cotija, camembert — the whole shebang.

You see, it’s spring outside. The breezes ruffle the meadows, green buds pepper the trees, the sun warms, so basking and frolicking are in order. It’s the season to hold a buttercup to your chin and test if its namesake dairy product suits your appetite, in case you weren’t sure.

Spring is transformation, growth, and awakening. It is a gentle and gradual process of the world returning to bloom. It is constant, perpetual, breathtaking change, a bridge between seasons.

It would be rather rude to demand spring to hurry

TribeLive, a student-run concert series led by Mac Mueller ’26, aims to fill the live music gap in Williamsburg. Grace Ki Rivera ’26 sits down with Mueller and TribeLive volunteers Sawyer Cohen ’26 and Emmett McLaughlin ’25 to find out more about the project.

Story and design by Grace Ki Rivera '26 Photos courtesy of Murawski Photography

When Mac Mueller ’26 stepped back into Williamsburg after attending a North Carolina music festival, he felt the absence of something vital. Williamsburg has music, sure. But where was the energy? The pulse? The kinds of moments that make you text your friends, “You’re missing this”?

Determined to fill that gap, Mueller developed his idea into TribeLive, a grassroots concert series that brings national touring acts to Williamsburg. The goal: to support artists while building a live music scene that extends beyond the College of William and Mary and Williamsburg’s local bars.

When I reached out to Mueller to talk about TribeLive, I expected a one-on-one conversation. Instead, when he walked into the Column 15 branch in Swem, he wasn’t alone.

With him were Sawyer Cohen ’26 and Emmett McLaughlin ’25. Both are volunteers helping to shape TribeLive behind the scenes. Once they slid into their respective seats, it was one continuous conversation about upcoming shows and half-finished ideas spilling over each other. It was clear that TribeLive isn’t just Mueller’s project — everyone at the table was part of making it happen.