chief editors

Camille Yang

mathilda Chen

Zoe oreopoulos

editors

harrison manders

Yuxin Zhao

aurora Fu JingYu

murphY ling

Zhengwen Kou

graphic design

Qiao Zhang

henrY guo

social media managers

shirleY lin

rita xu FangYi

Kursat tanriKulu

website manager

sihao pan

academic staff advisor

dr. hoi lun law

email thefilmdspatch2023@ gmail.com

social media @the film dispatch

Hardly foreign to the cinema, taboo subjects have been the sources of audience escape, excitement, and emotional resonance. Their depictions may cause controversy and discomfort, but they are, in fact, vital to the complication of traditional concepts and moral standards, prompting our reflections on taken-for-granted norms and conventions. This issue of TheFilmDispatch will focus on the theme of taboo and taboo-breaking in the movies.

Given the sensitive nature of the topic, we understand that certain content in our publications may be distressing to our readers. To ensure that we approach these topics with the respect and sensitivity they deserve—and to protect the well-being of our readers—we have decided to implement content warnings where necessary.

The purpose of content warnings is to ensure that challenging and sensitive subjects can be discussed openly while ensuring that all readers feel safe and respected. By adding these warnings, we aim to continue our debates and discussions with care and consideration.

Note that the views expressed by our contributors are their own and do not reflect the views or endorsements of the University.

If you have any questions about the use of content warnings, please feel free to reach out to TheFilmDispatch team at thefilmdispatch2023@gmail.com.

Grief is an impromptu vacation to your heart’s discontents

How dealing with suicide is dealt with in MorvernCallar(2002)

Marvel Maximus Mercurio

OnlytheRiverFlows (2023)

The Imaginary South and the Alchemy of Visualizing Taboo

Ziqi Xu

Queer Silent Cinema

Eve Jeffreys

The Whale (2022)Review: How to Represent Obesity?

Murphy Ling

Primrose Path (1940)

Katherine Heller

By: Marvel Maximus Mercurio

Marvel Maximus is a student on the next Masters in Counselling Studies programme at the University of Edinburgh.

Content Warnings: Suicide, Death and Bereavement

Morvern Callar (Lynne Ramsay, 2002) starts with a somber scene that sets the mood for the entire film. We are introduced to the titular character Morvern in a close-up of her face beside her partner’s body. As customary for Lynne Ramsay-directed films, a lot of the information in the frame is cut off from the audience, it insinuates a clear picture but never elaborates on what is happening or why. The light is warm, we are fooled into thinking this is the typical impassioned opening with a partner side by side in bed. Deftly acted by Samantha Morton, Morvern’s eyes are aloof, slowly scurrying around the scene as she smells the back of her partner’s neck. Before her hands slowly move toward his wrists and

cover scab-filled scars. She caresses him as if he were still alive. The camera gets farther away and only then is the audience filled in on the scene. Her partner’s dead by her side, a pool of blood on the floor. The amber light is not from a fireplace or a bedside lamp, it’s a cheap Christmas tree pulsing like police sirens. The room isn’t warm at all. The body is cold. Morvern gets up and reads her partner’s suicide note on the computer, with a series of instructions. “Don’t trytounderstand,itjustfeltlikethe rightthingtodo,” it began. He wrote a novel that he asked Morvern to publish. If this were any other film, what follows would be Morvern as she deals with her loss and attempts to fulfill her partner’s wishes. But

this is not that film.

From the second scene onwards, Morvern is seemingly unbothered by the death, telling no one, and having the dead body stay in place for days. From the audience’s perspective, she is recognizably in denial. But she doesn’t necessarily go through the typical five stages here. The way grief takes hold of Morvern is more clandestine. Suicide is already a taboo in most cultures, but the way Morvern deals with her partner’s self-inflicted death is anathema to how almost everyone would deal with it. She goes to campfire parties, leaves on vacations, and even desecrates her once lover’s corpse. The audience can only infer the motivations behind Morvern’s radical actions; as with Ramsay’s other films, motives are secondary to the poetry of reactions.

Chapple et al. (2015, as cited in Pitman et al., 2018) illuminate how suicide is and always has been referred to by people as a different, even stigmatized, death:

Whilst any sudden death might be perceived as shocking by its unexpected nature, suicide has long been thought to be the most stigmatizing of bereavements. In contemporary society this stigma is thought to arise primarily from social distaste and disapproval, associations of blame and shame, and also from social unease.

One of the reasons Morvern may refrain from revealing her partner’s death and its cause may be the weight of being the bearer of bad news. A sudden death, one as private

as suicide is, may change the perception of others about its circumstance. The bereaved may shy away due to “stigma arising from the association between suicide and mental illness, discrediting the deceased and their family” (Pitman et al., 2018). On the other hand, the public could see the dead as weaker in character from mental illness or having moral weakness. Moreover, other people may blame or judge the bereaved and the person left behind by the dead, as found in Pitman et al. (2018):

Consistent with our findings, these studies described the stigma of suicide bereavement in relation to others’ social discomfort and avoidance, with participants describing feeling blamed or gossiped about, concealing the cause of death, and concealing their grief.

Apart from that, Morvern’s almost absent reaction may be the result of her avoidance of making such an intimate and tragic secret public.

When not listlessly living alone or reveling in flings, Morvern spends most of her time in the film with her friend, but her friend is not privy to the truth, the truth that only Morvern knows in the entire runtime. Perhaps letting someone know, even one other person, would make the suicide that she was the only witness of, once a manageable private truth, into an unstoppable universal reality. Therefore keeping it would be easier and safer for her, not to mention more beneficial in the short term. Once she opens that door, and lets the death bleed into other people’s / page 7

lives, there’s no more room to hide in. No safe space for the status quo. So she denies and denies, and takes control of her actions from her grief and her partner, refusing to let someone else’s death dictate the rest of her life.

Morvern copes utilizing mainly avoidant-focused strategies, specifically denial of life changes through

distractions. As elaborated by Mathieu et al. (2022):

Avoidant coping styles are typically viewed as maladaptive strategies used to avoid intolerable feelings and can include refusal to accept the loss and deep feelings of grief, alcohol or other substance abuse, blaming others, avoiding/denial of life and identity changes, or distraction

She would like to think that her part-

ner’s departure is temporary, she acts every day as if that were the case, delaying the inevitable penny drop. She only dabbles in problem-focused coping, misguided as it may be, halfway through the film. She achieves it, finally dealing with her partner’s wishes, by discarding his corpse and coopting his writing. “Don’ttrytounderstand,itjustfelt liketherightthingtodo,” her part-

ner said to her posthumously. Perhaps her abnormal response is just reversing that same phrase. As some reasons for choosing death may be beyond understanding, the grief that comes after may fare the same way. Maybe the only way for Morvern to respond to something beyond reason is to be unreasonable herself.

Listening to the mixtape that was left

behind for her, she takes care of his corpse after days of decomposing, by cutting him up into pieces. She then gets a publisher to buy the book she overtook for a huge amount of money, erasing any trace of her partner’s name in it. In death, her partner helps her life, and in life, she makes his words eternal. Her actions, however immoral, can be understood as her way of not only retaining agen-

cy from her partner’s phantom, but also over herself, and her catatonic grief. Her partner did say that the novel was written for her in his note, so this is her way of fulfilling his last wish, by making a wish of her own. Morvern respects the dead by living, a responsibility the departed is free from.

By any usual standards, Morvern

isn’t a beacon of moral strength that could rally an audience’s empathy, her actions are sensibly a target of disapproval if not contempt for their irrationality. But though her reasoning isn’t ethically sound to the audience, it is to her state of heart and mind. As insensitive as some of the things she does are, seeing it through Samantha Morton’s excellently naturalistic nuances, it felt perfectly hu-

man and in character. Though she seems irreverent to her dead partner, his passing permeates her every decision since the film’s beginning. When she finally reveals the fact of his death haphazardly in a fight with her friend, her revelation gets lost in the exchange of words trading blows. Her friend only ends up reminding her that Morvern’s relationship with her partner wasn’t as clean as the

audience might have thought. Her grief is still hers alone. Invisible and unseen.

The consequences of Morvern’s deception, to herself and others, remain up in the air. Even when her publishers approach her and ask her for information on her next novel, she waves them off and delays the problem for another time; she is after all still grieving. She doesn’t think of future plans except for escape; her plans are only important up to the end of the film, the rest of her life she’ll figure out later, along with the audience. Just as Ramsay’s usual cinematography cuts things off the frame, so too is the plot set aside to prioritize spontaneous moments; the audience is left to fill in the blanks of the characters’ thoughts and interpret the image as is. The plot is like the grief of her partner’s death, it haunts the film, a surreptitious

reminder that even when Morvern is making love or is away on vacation, the audience, and presumably her, can’t help but think of it. Like Morvern reacting to death, and conversely, the audience reacting to her, we can only imagine intent, and enjoy the magnetic impetuousness of what’s occurring. Near the end, Morvern’s in a Spain cemetery, where the graves are adjoined on the walls. She picks up a flower on the left side of the frame, whilst the camera slowly pans horizontally, from grave to grave, until we reach her again on the right, putting the flower down. This is the closest thing to a funeral that Morvern attends for her partner, apart from burying his pieces in a mountain. She grieves in another country, on an unknown grave. Without a precise manual on how to grieve, she deals with death on her own terms.

In the closing shots, Morvern walks inside a club while everyone else dances, and she puts on headsets. Listening to her partner’s mixtape, she drowns out the club’s blaring noise, living in her private world with a ghost she alone hears. She paces, with absent but peaceful eyes as red and white lights flicker on her face, like a jittery Christmas night. The room is alive; people are joyfully jumping, but it feels cold. At the end of the day, maybe that’s all grief is, something you carry with you, taking part in whatever you do, a tune only you can hear. And that’s why it’s indistinguishable, grief is something you wear on your face but can’t wipe out with tears or micellar water.

Chapple, A., Ziebland, S., & Hawton, K. (2015). Taboo and the different death? Perceptions of those bereaved by suicide or other traumatic death. SociologyofHealth&Illness,37(4), 610–625.

Mathieu, S., Todor, R., De Leo, D., & Kõlves, K. (2022). Coping Styles Utilized during Suicide and Sudden Death Bereavement in the First Six Months. International Journal of EnvironmentalResearchandPublicHealth,19(22), 14709.

Pitman, A. L., Stevenson, F., Osborn, D. P. J., & King, M. B. (2018). The stigma associated with bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: A qualitative interview study. Social Science & Medicine,198, 121–129.

Ramsay, L. (Director). (2002). Morvern Callar [Film]. Alliance Atlantis Motion Picture Production; BBC Film; UK Film Council; Scottish Screen; The Glasgow Film Fund; BBC Scotland; National Lottery; H2O Motion Pictures; Company Pictures.

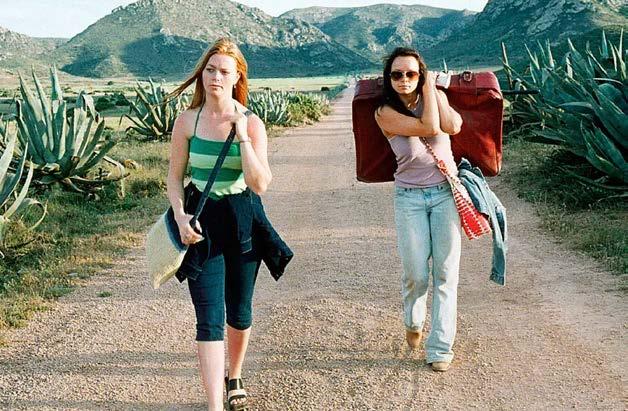

By Ziqi Xu

Content Warnings: Strong Bloody Images, Violence

OnlytheRiverFlows (Wei Shujun, 2023) sets its narrative in a fictional southern region, depicted as perpetually enveloped in mist and humidity. The landscape, marked by anonymous grasslands, rivers, swamps, and ruins, sketches the backdrop of an imagined, underdeveloped city

in mainland China, and introduces an atmosphere filled with enigmatic dangers and wild ambiguity. Within an indiscernible seasonal setting, the plot weaves through a set of serial murders and the relentless pursuit by law enforcement, crafting a narrative that merges wildness with vibrancy. This article delves into how the film’s damp, somber, and ambiguous southern landscape effectively visualizes the encroachment of insanity and pathological societal taboos. It examines the landscape’s impact on the uncertain fluctuation of character gender, masculinity, and the nature of criminal violence. Through a comparative analysis with the urban spaces depicted in South Korean serial killer films, I explore how Chinese mainland cinema utilizes the southern narrative setting to confine fear to impoverished rural areas. It confronts the pervasive anxiety of identity dissolution in modernity, revealing a conservative, almost reticent, ap-

proach to these themes.

Nominated for the 76th Cannes Film Festival, this adaptation of the renowned Chinese author Yu Hua’s short story unfolds the narrative of Ma Zhe (Zhu Yilong), a southern small-town policeman investigating the brutal murder of a widowed elderly woman. As the investigation progresses, the individuals connected to the case mysteriously die one by one. Rather than focusing on the logical deduction of the case, the film weaves the deaths together through a profound and inexplicable fate, blending the dislocation of dreams and reality. The image of a madman who is regarded as a murderer does not simply point to the psychological deformation of an individual, but is also a more complex collective and political illusion. This spectral presence permeates the humid atmosphere of the south city, enveloping Ma Zhe, who, as a stifled law enforcer, at the same time.

The narrative delves into four dead characters aborted by the so-called normalization: an elderly woman with a masochistic fantasy, a middle-aged poet entangled in an affair, a wrongfully imprisoned crossdressing hairdresser, and a child consumed by naive malevolence and curiosity. Representing the unseen side of society, these figures navigate a world rife with taboos, existing as anomalies discarded by conventional norms. The film evokes an archaeology of taboos that follows, recollects, and pieces together these displaced fragments that pulse in excess of the pandemonium of the image and gesture toward an encounter with an absurd reality.

OnlytheRiverFlows indulges the shaking and instability of film shooting, bringing with it the water vapor of humid southern China, reaching the viewers with the resonance of obsolescence. The film’s abundant

depiction of rain-drenched landscapes, including lakes, swamps, and grasslands, creates a visual blindness which disturbs the narrative framework and paralyzes into view the remains of the director’s intention. Before viewers can piece together the plot’s intricacies, they are immersed in the evocative imagery of a desolate, rain-soaked South. The South, as an important narrative element containing crime and hidden violence, cannot be anchored to any specific location in mainland China. Its seasons are indistinct, and its rivers, bridges, and villages remain unnamed, positioning it as an enigmatic locale on the map. This imagined zone, floating between reality and stereotype, sustains a delicate balance with tangible geographical realities. This flexible imaginary domain facilitates a unique alchemy, transforming unseen mental turmoil, chronic conditions, anxieties, and despondency into visible elements of the landscape. Through unceasing rain and omnipresent blue, the film

makes the intangible agony and strife of its characters discernible. Thus, the South transcends its role as a setting to become a potent vessel for visualizing the taboo.

This highly stylized depiction of criminality evokes an affinity with the spatial portrayals found in South Korean serial killer films like Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho, 2003) and The Chaser (Na Hong-jin, 2008) where the urban landscapes of capitalist societies—marked by bathrooms, apartments, convenience stores, and gas stations—underscore the nation’s modern identity. These settings not only extend the country’s contemporary image but also critically reflect on the societal risks prevalent at the time, using criminal narratives to indict the underlying social malaises. The prevalence of serial killer films in South Korea is interpreted as indicative of an “advanced nation disease” (Beauchamp, 1987, p. 322), in other words, the inevitable and alarming results of modern in-

dustrial society-increases in the rates of divorce, juvenile crime, school violence and other social ills associated with countries like the United States. It poignantly points out the crucial link between serial crime and the unstable global economy, which must be understood in the context of the experience of South Korean modernity.

In contrast, mainland China’s serial killer films set in the southern landscape transform the specific ailments of advanced societies into a nebulous miasma of insanity, fear, and madness. These emotions are confined within the fantastical underdevelopment of villages and towns, preventing the peril from reaching metropolitan areas. Instead, they linger in an imagined space far away from modern realities, sidestepping the proximate threats and successfully safeguarding a precarious sense of safety vital for modern existence. Whereas the South Korean experience critiques the desire for self-determination within a neoliberal economy,

Southern Chinese cinema explores the covert anxieties existing on the margins of societal order. The former articulates an accusation, while the latter voices an underlying fear.

The South, as depicted in the film, presents an ambiguous and elusive geography, embodying the perils of losing one’s way. The delineations of sexual addiction, gender nonconformity, and infidelity merge into the film’s moisture-laden air. At the same time, this environment further obscures the protagonist Ma Zhe’s sense of agency and conventional notions of masculinity. Contrary to the archetype of a physically imposing, valiant officer, Ma Zhe grapples with psychological strain from the investigation and personal turmoil due to his wife’s pregnancy with a potentially malformed fetus, casting him in a vulnerable, introspective light within the narrative arc. The fluidity of water vapor and lakes exaggerates this loss of agency and the crisis of masculinity. The climax sees Ma Zhe pursuing the assumed murderer to a de-

crepit temple, where, under immense psychological duress, he resorts to gunfire. The dilapidated temple, murals, and Buddha statues instantly turn into a special space, and the gun he raises replaces his useless genitalia allowing Ma Zhe’s gender violence to be released in an act of desperate venting. The South thus becomes a psychological geographical space where murder, misogyny and broader philosophical questions of sovereignty collide.

Richard Dyer identifies “how serial murder is almost always associated with modernity” (Dyer, 2015, p. 10), positing that the relentless cycle of repetition inherent in capitalist society fosters a profound anxiety. At the core of South Korean serial murder films lies a quest for self-mastery amidst the unchecked spread of economic globalization. In contrast, crime movies from mainland China’s South convey a self-aware sense of resignation, yet they remain deeply connected to their economic context.

The film juxtaposes the region’s hidden prosperity and opulence against the moral decay it precipitates. The depiction of the South here is not as a developed area celebrated by the nation, but rather as a locale grappling with persistent poverty of self-awareness and disorder. This subtle portrayal reflects societal apprehensions about the potential upheavals accompanying modernization.

OnlytheRiverFlows exemplifies the cinematic utilization of the Southern landscape to craft a narrative set in an indistinct, untethered locale where crime, madness, and taboo intertwine with the region’s pervasive humidity, ceaseless rainfall, rivers, and expanses of wilderness. This Southern setting blurs the lines between the tangible and the imagined, facilitating a complex exploration of gender dynamics, individual and collective conflicts, and existential anxieties-all reverberating within an unrecognizable terrain. In contrast

to the direct approach of South Korean serial killer films, which integrate crime into the fabric of urban daily life, OnlytheRiverFlows adopts a more guarded stance towards reality. It confines the terror of serial killings to distant towns and rural settings, deliberately keeping such fears at arm’s length from urban and contemporary realms. This cautious perspective reflects a broader hesitation among mainland Chinese filmmakers and audiences to confront the unsettling implications of modernization and the attendant crises. Through its indirect examination, the film casts a remote gaze upon these deep-seated fears, encapsulating the collective apprehension surrounding the impact of societal progress.

Beauchamp, E. R. (1987). The Development of Japanese Educational Policy, 1945-85. HistoryofEducationQuarterly, 27(3), 299-324.

Dyer, R. (2015). LethalRepetition:SerialKillinginEuropeanCinema. British Film Institute.

Bong, J-h. (Director). (2003). Sarinŭi Ch’uŏk [Memories of Murder] [Film]. CJ Entertainment; Sidus Pictures.

Na, H-j. (Director). (2008). Ch’ugyŏkcha [The Chaser] [Film]. Big House; Finecut.

Wei, S. J. (Director). (2023). Hébiān de cuòwù [Only the River Flows] [Film]. KXKH Film.

Queer cinema, film which explores the lives and identities of LGBT+ individuals, has been around almost since the moving picture was invented. A fundamental element of our humanity, queerness has been continuously examined through the art of cinema for over a century, and is of course

still being explored today. Early silent films were a melting pot of incredible innovation and bizarreness, from the visual effects in sprawling epics like Metropolis (1927) to heart-wrenching meditations on the human condition like The Wind (1928). The creativity of this developing medium lent itself to

By Eve Jeffreys

Content Warnings: Homophobia

18 /

the depiction of queer themes, some surprisingly explicit in its queerness and some more abstract.

Believed to be the first ever positive portrayal of gay men in cinematic history, Anders als die Andern (‘Different From the Others’) is a 1919 feature that follows a violinist, Paul Körner, who falls in love with his male student. Körner is subsequently blackmailed because of his orientation, and although the judge is sympathetic to him, when the story becomes public Körner commits suicide. Much like Basil Dearden’s Victim (1961), the film was intended to convince the public that laws against homosexuality helped no one, and only led to an increase in extortion. Sadly, this film was incredibly controversial in its time, and many prints were destroyed by the Nazi party alongside other queer works. Fortunately, enough of the film sur-

vives to us today that we can understand the narrative, but some scenes are forever lost. The film is a harsh reminder of all the history lost under Nazi rule, but is also a reminder that some people were sympathetic towards homosexuality even so long ago.

Lot in Sodom (1933) is a less realist take on queer cinema. It is based on the biblical story of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 18:16-19:29), which has long been taken as a condemnation of homosexuality (hence the term ‘sodomite’). Despite this seemingly homophobic story, the visual choices of Lot in Sodom have made it an important piece of queer art. The film itself is highly abstracted, with images of half-naked men overlaid and intertwined to represent the “sin” of the city of Sodom. Queer audiences of the time must certainly have picked up on the subtext of this film,

purposeful or not, and queer individuals likely would have seen themselves in the characters on the screen. Although not a positive portrayal like Anders als die Andern, Lot in Sodom deserves its place in the conversation about LGBT+ cinema history based on its fascinating visuals alone.

The exploration of queer identity in silent cinema did not end with the adoption of the “talkie” as the dominant cinematic form. Jean Genet’s Un Chant D’Amour (‘A Song of Love’) from 1950 is still silent, but far more sexually explicit than the other two films discussed. The plot focuses on a relationship between two men in prison, who have fallen in love through the wall between their cells but have no way of touching each other. They substitute a physical relationship by blowing cigarette smoke through a hole in the wall and creating a dream world where they are together outside of prison. In love but unable to be together, the story of the two male leads mirrored the reality for many queer couples of the time. But the story is not one of desolation; even in these tough conditions, they can express their love for each other. The themes of this film are strongly recalled in the 2021 movie Große Freiheit (‘Great Freedom’), the story of a man imprisoned for his homosexuality who finds love in prison. There is even a similar image where the love interest lights the main character’s cigarette through the cell door, imitating the erotic smoke-blowing scene in Un Chant D’Amour. Although like Anders als die Andern, Un Chant D’Amour faced years of censorship, it fortunately survives to us in full.

The use of cinema as a tool for examining queer history is something that cannot be overstated. Through film, we are transported to worlds decades old that are populated with people who aren’t all too dissimilar to us. Silent cinema, a medium that broke so many boundaries, can feel just as

Still from Lot in Sodom

fresh and relevant today as it was decades ago, especially in conjunction with queer themes. Despite the fact that these films are all silent, they give the queer people of history a voice, and are invaluable to our modern understanding of identity and desire.

page 20 /

Still from Anders als die Andern

Meise, S. (Director). (2021). Große Freiheit [Great Freedom] [Film]. FreibeuterFilm; Rohfilm; ORF Film/Fernseh-Abkommen; Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF); Piffl Medien; Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien; Deutscher Filmförderfonds; Filmfonds Wien; Filmstandort Austria; Medienboard Berlin-Brandenbur; Mitteldeutsche Medienförderung; Österreichisches Filminstitut.

Filmography

Dearden, B. (Director). (1961). Victim [Film]. Allied Film Makers; Parkway Films.

Genet, J. (Director). (1950). Un Chant D’Amour [A Song of Love] [Film].

Lang, F. (Director). (1927). Metropolis [Film]. Universum Film (UFA).

Oswald, R. (Director). (1919). Anders als die Andern [Film]. Richard-Oswald-Produktion; Filmmuseum München.

Sjöström, V. (Director). (1928). The Wind [Film]. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Watson, J. S., & Webber, M. (Directors). (1933). Lot in Sodom [Film].

By Murphy Ling

Murphy Ling is currently pursuing an MSc in Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh. Content Warnings: Mental Health Issues, Suicide, Eating Disorders, Drug Misuse

Directed by Darren Aronofsky, The Whale (2022) is a heartbreaking story of an obese English professor Charlie (Brendan Fraser), mainly focusing on the last five days of his life with fragmented flashbacks. The film provides a glimpse of the relationships between Charlie and his friend Liz (Hong Chau), his daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink), his ex-wife Mary (Samantha Morton), and a Christian

22 /

missionary Thomas (Ty Simpkins). Aronofsky’s depiction of Charlie’s life is entangled with controversial social opinions on obesity, which complicates the film text and evokes thoughts on the representation of obesity in films.

The Whale is a challenging film considering its attitude towards obesity. It starts with a bold scene where

Charlie experiences great pain because of his congestive heart failure when he is pleasuring himself, his desire and pain are juxtaposed at the very beginning of the film and create emotional impacts on the audience. Aronofsky is not afraid to catch Charlie’s everyday routine of consuming lots of pizza and snacks, for which he exchanges his health. With grease on his face and the consequent vomiting, a mild sense of grossness is added to its realism, and the need to eat excessively is depicted almost like an inherent habit of self-compulsion. When demonstrating the invisibility and inferiority of obese people, the film combines their unwillingness to show their physical selves with their need to make a living. In Charlie’s case, his profession is an online lecturer, and he refuses technology to make his obese body visible and induces possible mocking from his students. His requirement

of being honest in the essays to his students contrasts with his inability to show himself on camera. Charlie also has to go through the malice of his daughter and the missionary’s persuasion of him to convert to God, which are all deeply linked to his overweight body. Through the communication between characters, the film condenses the societal hostility and targets it at Charlie, which creates a pessimistic atmosphere around him.

Whales, as the largest animals on earth, are spectacles themselves. Their giant figures and smooth curves make them islands in the sea. In the film, Charlie’s figure is created as a spectacle, his body an image hard to overlook. Fraser’s body in the prosthetic suit is almost shocking, and the layers of fat on his stomach droop. When he walks clumsily through the narrow corridor, his

giant figure between the walls indicates his confined and powerless status. Using the accessible facilities like wheelchair, rings and crutch, the setting in Charlie’s home shows a specific place where only Charlie can swim in it. The dim lighting sometimes blends Charlie’s figure with the sofa he sits in, further confining Charlie to his home, stressing that the house is a place he cannot move out of. The camera is sometimes set behind Charlie’s neck, and moves according to the movement of Charlie’s head, providing a point-of-view angle of what Charlie sees. Only the whales know how to live in an ocean, and Aronofsky creates this domestic space that people unlike Charlie could not make sense of, pointing out poignantly the confined and limited position of obese people, even if it is not comfortable for the audience to see the protagonist’s struggle to move in his own house.

Being honest is a characteristic that the film tries its utmost to dig out in Charlie and obese people in general. The film weaves it into every aspect of Charlie’s life. In his confrontation with Ellie, we learn that Charlie discovers his homosexual traits during his heterosexual marriage and starts a slightly unethical relationship with his male student. He abandons his wife and daughter to be with his lover. Charlie is thus double marginalized in society for his obesity and homosexuality, both identities he accepts without regret. Also, the film dares to bring up reli-

gious discussions about obese bodies, by putting up debates between Charlie and the missionary Thomas. As the film progresses, the sorrowful past of Charlie is slowly pieced together, and the audience learns that his obesity is a way of reacting to his boyfriend’s death. His unethical relationships, along with his overeating, are his ways of escaping from the hegemonic standards of heterosexual marriage and a healthy body. The fat that piles up in Charlie, therefore, is a ghost from his past and predicts the coming death in his future, his obese figure is soaked with psychological melancholia, stimulating sympathy similar to the experience of watching ASingleMan (Tom Ford, 2009), in which George Falconer (Colin Firth) prepares his suicide after boyfriend’s death. Although losing control of keeping in shape, unlike the obese mother Bonnie (Darlene Cates) in What’sEatingGilbertGrape (Lasse Hallström, 1993), who always needs looking after and lacks initiative, Charlie encompasses individual agency and expresses his true feelings, suggesting Ellie and his students to write what they think in essays. Eventually, Charlie is honest enough to open the camera and show his real self to his students. By capturing Charlie’s attitude towards fake feelings, the film tries to dissolve the invisibility of obese people and calls upon rethinking how to treat them on a social level.

The Whale provokes arguments for it does not cast a real obese actor to

play Charlie, and the almost destined pessimism of Charlie may be something too extreme. However, this film is still honest enough to centre its narrative on Charlie and spends time exploring possible dilemmas and desires in homosexual and obese people. In the end, Charlie gathers his strength, struggles up and walks towards his daughter, eventually disappearing in a flash of white light. It is a surreal ending that suggests death and liberation from his physical form. However, the discussion on obesity in real life continues, and we still need to reflect on the marginalization of obese people in society and think of ways to better represent them in the media.

Aronofsky, D. (Director). (2022). The whale [Film]. A24; Protozoa Pictures.

Ford, T. (Director). (2009). Asingleman [Film]. Fade to Black Productions.

Hallström, L. (Director). (1993). What’s eatingGilbertGrape [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

By Katherine Heller

Katherine Heller is a PhD student in Translation Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Content Warnings: Domestic Violence, Substance Abuse

Ginger Rogers is most well remembered today for the musical films she starred in alongside Fred Astaire. The two stars appeared in ten films together – nine of them at RKO Pictures between 1933 and 1939. During this initial period of their partnership, Astaire made just one other film, 1937’s A Damsel in Distress.

Rogers, however, made twelve. Roger’s early filmography spanned genres, including films as diverse as the pre-code crime drama Upperworld (1934), the ensemble drama Stage Door (1937) and the screwball comedy VivaciousLady (1938). Upon the initial dissolution of her partnership with Astaire in 1939, Rogers sought out roles that would further establish her as a dramatic actress. In 1940, she had three starring roles; in Primrose Path, KittyFoyle, and Lucky Partners.

LuckyPartners is a romantic comedy in the tradition of Rogers’ late 1930s work – she plays opposite Ronald

Colman as a street artist. KittyFoyle and especially Primrose Path, however, deal with more serious and controversial themes. The former, a romantic drama exploring social class divisions, was a great success and brought Rogers an Academy Award for Best Actress. However, many of the taboo subjects explored by Kitty Foyle’s source material – a 1939 novel of the same name by Christopher Morley – were minimised due to the restrictions of the Production Code. Issues such as extramarital affairs and abortion are avoided. The heavy presence of the production code on KittyFoyle makes it even more surprising that a film such as Primrose Path ever saw the light of day.

Primrose Path was adapted from a 1938 play of the same name by Robert H. Buckner and Walter Hart,

itself an adaptation of Victoria Lincoln’s 1934 novel February Hill. The film was directed by Gregory La Cava, who, like Rogers, is perhaps also best remembered for things rather unlike Primrose Path – for example, the renowned screwball comedy MyManGodfey (1936). He had also previously directed Rogers in two other films; the aforementioned StageDoor and 1939 comedy Fifth Avenue Girl. In Primrose Path, La Cava directs an effervescent performance from Rogers, bringing together her talents in drama and comedy honed over the previous decade. Primrose Path centres on Ellie May (Rogers), a young woman living in a working-class neighbourhood with her parents, grandmother and younger sister. Ellie May’s father is an alcoholic and so her mother supports the family. Due to the Produc-

tion Code it is never stated outright, but it is very clearly implied that the mother’s profession – and grandmother’s former profession – is sex work. The film follows Ellie May as she tries attempts to cross class divides and avoid falling into the family business. The film makes clear the social and financial situation of the family through how the domestic scenes are shot. The majority of these scenes take place in one room. The lighting in this room is stark and unsophisticated and the entire room is often filmed in one long shot, emphasising the claustrophobic nature of the space. This contrasts with the bright sunshine in many of the early outdoor scenes, providing the audience with a visual representation of the possibilities that exist for Ellie May with and away from her family. These relatively naturalistic lighting styles are punctuated with scenes featuring more intense use of shadow. For example, in one climactic scene depicting conflict between Ellie May and her love interest Ed, a dramatically lit low-angle shot of Ed is used to reinforce her low social standing. At another point, the grandmother is lit with an imposing shadow – conveying the threat of Ellie May following in her family’s footsteps looming large.

In addition to its uncompromising depiction of class divisions, Primrose Path also deals with other issues such as alcoholism, suicidal ideations, bullying and domestic violence. These

serious themes – explored as frankly as one would think was possible in a Production Code-era Hollywood film – are brought together by Rogers’ skilful performance as Ellie May. Her performance in La Cava’s remarkably realist drama is, I believe, livelier and more truthful than her Academy Award winning turn in KittyFoyle. Perhaps now the time has come that Primrose Path can be fully appreciated for its success in depicting taboo subjects despite the pressures of censorship.

Del Ruth, R. (Director). (1934). Upperworld [Film]. Warner Bros.

La Cava, G. (Director). (1936). MyMan Godfrey [Film]. Universal Pictures.

La Cava, G. (Director). (1937). Stage Door [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

La Cava, G. (Director). (1939). Fifth Avenue Girl [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

La Cava, G. (Director). (1940). Primrose Path [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

Milestone, L. (Director). (1940). Lucky Partners [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

Stevens, G. (Director). (1937). A Damsel in Distress [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

Stevens, G. (Director). (1938). Vivacious Lady [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

Wood, S. (Director). (1940). KittyFoyle [Film]. RKO Radio Pictures.

‘I want you to eat me’ Cannibalism and Queer Gothic in BonesandAll(2022)

By Amelie Mackay

Content Warnings: Graphic Scenes of Extreme Gore and Violence, Depictions of Mental Health Issues

Cannibalism perhaps underlines the ultimate taboo, and has consequently become a popular device for horror in film. Classic horror embodies the cannibal as an othered monstrosity; in America, they live in the hills and prey on unsuspecting ‘good’ Americans. But in Luca Guadagnino’s film Bones and All (2022), this is not the case. Here, cannibalism is inserted into an ordinary rural, and sometimes suburban, youth. Maren, played by Taylor Russell, is a young girl living with her single father. Lee, played by Timothee Chalamet, is a typical American teenage boy, but can’t control his hunger for human

flesh. Together, they form a romance on the run with breathtaking horror in between.

Yet beneath the brutal veneer is another meaning, one which resonates with an audience used to rejection from society. As the film progresses, the queer undertones become quickly visible; Maren and Lee are essentially a bisexual couple, drawn together by their similar desires that others find disgusting. Kirsty Puchko agrees, reviewing the film for Mashable: she argues that Guadagnino ‘embraces body horror to express homophobic self-loathing brutally fostered

by society in Reagan-era America’ (Puchko, 2022). The brutality of the real world may not be as extreme as biting into the arm of a recently-deceased woman, but certainly feels bleaker when viewed through Guadagnino’s camera. Through the violence they face and must commit, the ‘eaters’ (the way in which cannibals are referred to in the film—the term ‘cannibal’ is never used) become anti-heroes. Sully, an older eater, becomes increasingly sinister in each of his appearances: he embodies the monster that an eater can become, if they are called a monster long enough by society.

Bones and All, in classic American Gothic fashion, blurs images of typical middle-America with extreme violence. A viewer could be lulled into a sense of security by its first five minutes: the film’s opening credits play over naïve paintings of the countryside on a school display board, and a high-school drama

starts to unfold. Maren is invited to a sleepover, but says her dad wouldn’t let her go. She sneaks out, arriving to a group of very typical 1980s teenagers, permed hair and painting each other’s nails, going well—until Maren bites off another girl’s finger. She arrives home with someone else’s blood down her front, and once again she and her father must skip town.

I would argue that this scene is the film’s first implication of queerness. Jordan Currie, writing for XtraMagazine, says, ‘[t]he finger-biting scene evokes the spirit of being a young queer and accidentally kissing your best friend you have a crush on or slipping up and saying the wrong thing around them’. The scene is illuminated in warm colours, the camera taking an intimate bird’s-eye view of the two girls, who are lying under a glass table. The items on top of the table are visible around them in frame. But as Maren leans in as if to kiss, instead she bites. The disgust

30 /

and fear the other girls show is perhaps the feeling of being outed to a hyper-feminine friendship group: it is an encroachment on their heterosexual idyll, transforming Maren into a monster. Many queer people can surely relate to the feeling of being welcomed one minute, and rejected the next.

Not long after this incident, Maren is abandoned by her father. She wakes up alone in the house they’ve settled in, one of the many transient locations that the film moves between. Allan Lloyd-Smith notes that

…the Gothic situates itself in areas of liminality, of transition, at first staged literally in liminal spaces and between opposing individuals, but subsequently appearing more and more as divisions between opposing aspects within the self. (Lloyd-Smith, 2004, p.6)

Arguably, Bones and All represents liminality within the self through the crumbling homes that Maren and her father move through. In Maryland, Maren wakes and wanders through their new house. The ceiling is falling down in pieces, and the furniture is haggard. In deep-focus shots, Maren’s neutral clothing blends into her environment, encasing her in the transient atmosphere of the place. This type of cinematography seems characteristic of the chamber-gothic, demonstrating that the American Gothic need not only take place in sweeping rural environments, but can also be explored in the confined spaces of America—something

Lloyd-Smith points to as a more contemporary development in the gothic mode.(Lloyd-Smith, 2004, p.7)

Human savagery is often attributed to rural environments, particularly in the United States: Jennifer Brown explores this idea in her book Cannibalism in Literature and Film(2012). One of her focuses is the ‘American regional cannibal’, usually a hillbilly stereotype—this being a caricature of the rural white American and presented as uneducated and often inbred (Brown 2012, p.108).

She argues the reason for this is that ‘[o]ur secret dread is that the dark, drunken hillbilly is no Other, but us’ (Brown, 2012, p.116). For a viewer of classic 1970s horror films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and TheHillsHaveEyes (which Brown analyses), the villainization of impoverished Americans is something made more disturbing by its reflection in reality. In Bones and All, Guadagnino asks how our attitude to the familiar cannibal changes when they are no longer the villain.

Bones and All may not feature all the ingredients of hillbilly horror, but it isn’t too far removed from the poverty defining the hillbilly character. Puchko notes that ‘[p]overty is key to understanding both lead lovers, who—like many LGBTQ youths— have been disowned or ostracized because of their desires, and so they live on the streets, scraping by however they can’ (Puchko, 2022). We

learn that Lee and his family suffered abuse from his father, suggesting the generational trauma that is often closely tied with growing up in poverty. Indeed, the film implies that being an ‘eater’ is something hereditary, passed to Maren by her birth mother and to Lee by his father: just as the past is inescapable, cannibalistic desires are irrepressible. In the film’s pivotal scene, in which Lee finally reveals to Maren what happened to his father, the ties that bind become ever more visible. ‘I ate him right the fuck up,’ he says, ‘and it felt fucking great’ (Guadagnino, 2022). To deal with his father’s brutalism, Lee must reiterate a cycle of violence. Like Brown’s 70s horror, Bones and All ‘upsets the wholesome idea of the American family’, presenting the brutal reality of growing up in rural poverty, with hereditary cannibalism as a gothic metaphor for generational trauma (Brown, 2012, p.112).

In addition, the difficulty of life on

the road as an eater can be compared with the difficulty of survival as a queer person. In the film’s most explicitly queer scene, Lee seduces another man at a carnival, and slits his throat so that him and Maren can eat. Currie says of this scene, ‘survival is ugly. Not having a better solution when forced into situations outside of your control is ugly. Regret and guilt, which is what Maren experiences in the aftermath of what she and Lee have done, is ugly’ (Currie, 2022). The latter part refers to when Maren discovers the man had a wife and child, breaching her personal morality rules. Her ultimate fear is that she may lose control of any morals she is trying to maintain, and become an eater taking pleasure in evil, like the men that they met on the lakeshore in Missouri. Currie argues that Sully’s character ‘represents what being rejected from society and living without community can do to an individual’, and it could be suggested that this is the direc-

tion the couple are heading in: Lee and Maren, as queer characters, are forced to turn on other queer people if they wish to survive (Currie, 2022).

By exploring cannibalistic desires, Bones and All rips the guts from rural America, and the traumas created by a youth in the margins. Guadagnino said of his film, ‘[i]t’s about children being lost in the wilderness and having to find a way back home… and finding that there is no such place as home, and that will invent the possibility of home’ (Guadagnino qtd. in Currie, 2022). The attraction between Maren and Lee recognises the way people are drawn together by desires they can’t understand nor control, just as finding a community gives queer teens the space to be themselves. ‘I thought I was the only one,’ Maren admits, shortly after meeting Lee: through the heavily gothic atmosphere of the film, Guadagnino can lend the dark theme of cannibalism a symbolic weight (Guadagnino, 2022). Against a backdrop

of a culture that centres violence and marginalisation, the sympathetic queer cannibal does not seem such a far-fetched idea.

Brown, J. (2012). Cannibalism in Literature and Film. Palgraye Macmillan.

Currie, J.(2022, December 16). Thequeer gutsof‘BonesandAll’

Lloyd-Smith, A. (2004). American Gothic Fiction: An Introduction. Continuum.

Puchko, K. (2022). ‘Bones and All’ review: Thenextgreatqueerhorrormoviehas arrived with a cannibal romance.

Guadagnino, L. (Director).(2022). Bones and All [Film]. Frenesy Film Company; Per Capita Productions; The Apartment; MeMo Films; 3 Marys Entertainment; Ela Film; Tenderstories; Amazon Prime Video; Sky; Cor Cordium.