FOUNDER OF THE FEMISH ORGANIZATION, Samantha Martin

Thank you for checking out our e-magazine! This is our 10th Issue of our digital bi-monthly magazine.

This Issue we are celebrating 3 years of FEMISH! For those reading and sharing this Issue: THANK YOU for caring and giving air to this important conversation!

As a reminder, FEMISH is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, currently running on volunteer & intern fuel If you would like to assist with the creation of this monthly magazine, we are looking for editors, writers, marketing, you name it!

Have a story to share? Found a relevant news article we should talk about? Know someone we should interview? Let us know by reaching out to info@femish org and check out our Contributor Form linked on the last page

Don’t forget to subscribe to our website and follow our social media accounts: Instagram, Facebook, Tiktok

Thank you for all your support! Together we can create a welcoming and inclusive world

Our next issue will be out in April 2025, see you then!

Students from NCC’s Human Concept Design class contributed articles to this FEMISH Issue

FEMISH Interns from Adler University’s Social Justice Program contributed to this FEMISH Issue

Founder of The FEMISH Organization, Femme Equity Activist, and attorney who was fed up with gender bias and discrimination She stumbled upon the term "femmephobia" and saw the need for this loop-hole in society to be closed @femmeesq

With AI at our side, our digital magazine was expertly curated, leveraging its organizational powers to streamline content and its writing assistance to refine our message, ensuring a compelling and cohesive reader experience

Creating sustainable change takes: learning, community, educational materials, and people deducated to the cause. Help us BUCK BIAS with a small donation today!

Your donations help us fund events and create educational content to promote self-awareness and debias society so that we have a world where everyone is seen and valued for who they are

FEMISHisluckytohaveanamazingrelationshipwithNorthCentral CollegeinNaperville,ILwherewecontinuouslyworkwiththeHuman ConceptDesignClasstogivestudentsrealworldexperienceof workingwithnonprofitorganizations. Additionally,wehavea wonderfulinternshiprelationshipwithAdlerUniversity’sSocial JusticeProgramwhereweworkwithinternsstudyingfortheir MastersorDoctorate.

ThisissueofFEMISHMagazineisextraspecialinthatwehavework fromover7FEMISH-affiliatedstudentsincluded!

Read,onenjoy,share,support.Theirinterest,passion,andhard workmean*everything*.

Founder,ExecutiveDirector

A teenage boy lowers his voice and slouches, afraid that standing too straight or speaking too softly might seem “girly.” At the same time, a professional woman swaps her bright floral blouse for a neutral blazer, worried an overly feminine look will undercut her credibility These everyday adjustments reflect a pervasive but often unnamed force: femmephobia, the fear or devaluation of anything feminine. And behind each small selfcorrection lies the psychology of self-surveillance – the internal policing of one ’ s own behavior to avoid judgment.

Femmephobia refers to society’s systematic devaluation and regulation of femininity – in any body or identity (Hoskin, 2019). In other words, traits or expressions deemed “feminine” are often ridiculed, penalized, or seen as inferior, whether they appear in women, nonbinary people, or men. This insidious prejudice can manifest in countless ways. For example, we tend to take it for granted that a man might be mocked or even attacked for acting “too feminine,” or that a woman in an overly frilly dress won’t be taken seriously at work. As Dr. Hoskin notes, such reactions seem almost naturalized –deeply ingrained biases we hardly question (Hoskin, 2020) Yet the assumption that masculinity equals strength or credibility, while femininity is frivolous or weak, is a learned prejudice, not a fact of life. Femmephobia teaches us, from a young age, that feminine qualities are something to regulate or apologize for.

Femmephobia doesn’t only hurt women – it profoundly affects men and boys by enforcing rigid masculinity. From boyhood, many males learn that being called “girly” is an insult, and any show of gentleness, emotional vulnerability, or interest in traditionally feminine things may invite bullying (Pascoe, Dude, You’re a Fag, 2007) Young boys perceived as too feminine often become targets of harassment and even violence, sometimes from their own family members. As adults, men who deviate from macho norms can face social punishment; something as simple as wearing makeup or pastel colors may provoke ridicule

This pressure creates what psychologists call a fear of femininity, leading men to constantly self-censor their behavior –avoiding anything that might be labeled “unmanly” (Connell, Masculinities, 1995). The result is a form of toxic masculinity that harms everyone: men may feel they cannot freely express themselves, and those who do step outside the masculine box can be ostracized or worse.

Ironically, women face a double bind under femmephobia On one hand, traditional gender norms still pressure women to be sufficiently feminine (at least in appearance); on the other hand, if they are too feminine, they risk not being respected. Dr. Hoskin’s research found many women – across sexual orientations – feel intense pressure to be “less feminine” in various areas of life (Hoskin, 2019). In an interview, she noted women frequently believe they must tone down their appearance or mannerisms at work, in sports, or even while dating

One study of 97 women documented how, after experiencing a femmephobic incident (like being belittled for a girly trait), the overwhelming response was to suppress their femininity going forward (Hoskin, 2017). Almost none of the women felt free to amp up or proudly embrace their feminine expression in response; instead, most trimmed it back as a protective measure. (Cont’d)

Essentially, women learn to walk a tightrope – adjusting their look and behavior to be “just feminine enough” but not so much that they’ll be dismissed. “You cannot move freely in the world when you are walking a perpetual tightrope,” Hoskin observes, highlighting the exhausting toll this balancing act takes (Hoskin, 2020)

Femmephobia also runs through queer and trans communities, sometimes in surprising ways. For instance, within LGBTQ spaces, masculine-presenting expressions can be unwittingly privileged over feminine ones – a phenomenon often called “femme invisibility” or internalized femmephobia (Serano, Whipping Girl, 2007). Feminine gay men have long been stigmatized both by heterosexists (for defying male norms) and even within gay male culture that can prize straight-acting masculinity.

Likewise, feminine-presenting lesbians or nonbinary people may find their identities questioned (“Are you really queer?”) because of the biased notion that queerness looks masculine (Hoskin, 2020). Transgender individuals face a particularly harsh form of femmephobia intertwined with transphobia: trans women are often attacked or mocked more viciously when they embrace a traditionally feminine presentation, as if violating the “rules” of masculinity were an unforgivable sin. Meanwhile, trans men sometimes feel pressure to perform hyper-masculinity to be seen as valid –any hint of femininity, like wearing nail polish, might lead others to cruelly label them “frauds” (Green, Real Man Adventures, 2012).

Self-surveillance is essentially the act of monitoring one’s own behavior, appearance, and mannerisms to ensure they conform to social expectations. Sociologists trace this to a powerful dynamic described by philosopher Michel Foucault: people internalize the gaze of others (or of authority) and end up disciplining themselves even when no one is overtly enforcing the rules (Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 1975). In effect, society doesn’t always need external watchdogs – we become our own.

Psychologically, chronic self-surveillance can be draining and damaging Studies in objectification theory have shown that women, in particular, habitually view themselves through an outsider’s eyes, leading to constant body monitoring, which in turn can increase feelings of shame and anxiety (Fredrickson & Roberts, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 1997).

Femmephobia and self-surveillance form a vicious cycle: because femininity is policed and devalued, people learn to preemptively police themselves. Women overwhelmingly suppress or tone down their feminine expressions after encountering femmephobic backlash (Hoskin, 2017).

Men enact a similar inner watchfulness A boy who’s been teased for being a “sissy” will likely start scanning his gestures, voice, and interests to purge anything that could be labeled effeminate. Over time, these small acts of self-erasure accumulate, constraining how individuals feel they can behave or present themselves.

The self-surveillance born of femmephobia carries serious personal and societal costs. Individually, it erodes mental health and authenticity. Socially, it helps keep outdated gender roles firmly in place.

Recognizing femmephobia’s role can help us untangle many social problems. Scholars like Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin are developing tools to help people revalue femininity and notice when they’re policing themselves or others unfairly (Hoskin, 2020). By easing up on self-surveillance, we reclaim personal freedom. And by celebrating the feminine instead of shaming it, we take a step toward a society where everyone can walk a little more freely – without the constant fear of how their gender expression will be judged

Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin is a feminist sociologist from Canada, co-editor if The Scientific Journal of Femininities, and a Board Member of The FEMISH Organization.

This article was created with the assistance of AI to research, analyze, and synthesize information on femmephobia and self-surveillance. The content is based on academic research, including the work of Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin, as well as sociological and psychological studies. While AI helped structure and refine the article, the ideas and insights reflect ongoing discussions in gender studies and social justice.

"Adler University offers graduate-level programs enrolling more than 1,200 students at campuses in Chicago, Vancouver and online In addition to education and training in psychological theory, science, and practice, students complete a range of required and elective experiences that extend beyond traditional practitioner training The University’s social justice mission-driven curricula have earned national and international recognition." - Adler University

“What stuck out to me most in my learning experience for this internship was how blatant femmephobia is in society and how easily accepted it has become. It starts right from birth, with gendered expectations placed on children, and is continuously reinforced in school environments, media representations, and social interactions. This realization left me questioning: What would society look like if we stopped perpetuating these harmful norms?”

“My perspective and knowledge surrounding the issue have changed significantly With this internship providing me with newer insights and research, along with growing individually, I now refuse to be silent in the face of femmephobia and the intersections involved. I plan to use my voice and my knowledge to educate others on the ever-growing issue of femmephobia and how it impacts us regularly”

“I have learned that the degradation of feminine traits and qualities is known as Femmephobia. I am surprised that it has been right under my nose, so to speak, for my whole life. Female-identified individuals are taught from a young age that “running like a girl” is bad. We are also taught that we should be quiet and courteous, while it is more acceptable for boys to be loud and take up space This idea furthers the problematic ideals that the history of our patriarchal society has created, putting men at the top and keeping them in power. ”

By Jessica Jensen, ADLER University Intern

For decades, autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been studied, diagnosed, and understood primarily through a male lens As a result, countless women have lived undiagnosed or misdiagnosed struggling to understand their own neurodivergence in a world that was never designed to recognize them

At the heart of this issue lies femmephobia the devaluation, erasure, and policing of femininity Femmephobia not only impacts social dynamics but also influences scientific research, medical diagnoses, and psychological frameworks, leaving many neurodivergent women invisible.

By exploring research on sex bias in autism and ADHD diagnoses, as well as the personal experiences of late-diagnosed women, we can uncover how gendered expectations have contributed to the systemic oversight of neurodivergent women and why it's time for a change

For years, autism and ADHD were considered “boys’ conditions ” Since more males are diagnosed than females, research has primarily focused on male behaviors, symptoms, and traits

Christine Wu Nordahl’s article, "Why Do We Need Sex-Balanced Studies of Autism?" highlights how diagnostic tools were designed based on male presentations, assuming that autism manifests the same way in all genders The result? A diagnostic model that doesn’t recognize how neurodivergence presents in women.

The same problem exists for ADHD Women with ADHD tend to display symptoms differently than men often showing inattentiveness, anxiety, or emotional dysregulation instead of the stereotypical hyperactivity associated with young boys

Because of this, many girls are labeled as “daydreamers”, “too sensitive,” or struggling with mental health disorders rather than being recognized as neurodivergent.

These diagnostic oversights are not accidental they are the result of deeply ingrained gender bias, a bias that stems from femmephobia.

One of the most striking gender differences in neurodivergence is camouflaging or masking the practice of hiding autistic or ADHD traits to appear neurotypical Women, due to societal pressures, are expected to:

· Maintain social relationships

· Exhibit emotional control

· Be empathetic and nurturing

Because of these expectations, autistic and ADHD women often force themselves to fit in, suppressing their natural ways of thinking, communicating, and behaving. According to research on latediagnosed AuDHD (Autistic & ADHD) women, this form of social survival takes an enormous toll:

· Chronic burnout

· Mental health struggles like anxiety & depression

· Delayed or incorrect diagnoses due to masking

By Jessica Jensen, ADLER University Intern

Many women with autism and ADHD don’t receive a diagnosis until adulthood, often after decades of struggle For many, the catalyst for finally seeking answers is perimenopause when hormonal shifts make masking nearly impossible Women in late adulthood report feeling betrayed by the medical system, forced to grieve the life they could have had if they had been diagnosed and supported earlier According to Emma Craddock’s research article “Being a Woman Is 100% Significant to My Experiences of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism” one participant put it:

"Going through the system for so many years while not knowing why your mental health is so awful can erode your confidence and damage your sense of self so profoundly."

In addition to struggling internally, many neurodivergent women also face external dangers. Studies show that undiagnosed autistic and ADHD women are at a higher risk of experiencing sexual assault and abuse Their difficulties in reading social cues and their people-pleasing tendencies traits often reinforced by gender norms make them more vulnerable to manipulation. This intersection of neurodivergence, gender, and safety is another way gender norms shape the lived experiences of neurodivergent women by forcing them to conform to passivity, politeness, and emotional labor, even when it comes at great personal cost

So, how do we fix this?

Sex-Balanced Research: Researchers must stop centering male experiences and start studying the full spectrum of autism and ADHD across genders.

· Trauma-Informed Diagnosis & Care: Clinicians need to recognize the impact of masking and how socialization affects neurodivergence in women.

· Feminist Neurodivergent Advocacy: We need to challenge the assumption that neurodivergent traits are "male" traits and push for greater visibility of autistic and ADHD women in public discourse.

· Ending Femmephobia in Medicine & Psychology: It’s time to stop treating neurodivergent women as anomalies and start recognizing the unique ways in which femmephobia erases them from diagnostic frameworks.

By understanding how femmephobia shapes neurodivergent experiences, we can begin to dismantle the biases that leave so many women struggling alone, misunderstood, and unseen.

Neurodivergence is not a male disorder, and femininity is not a mask It’s time for the world to recognize, validate, and support ALL neurodivergent people not just those who fit the existing mold

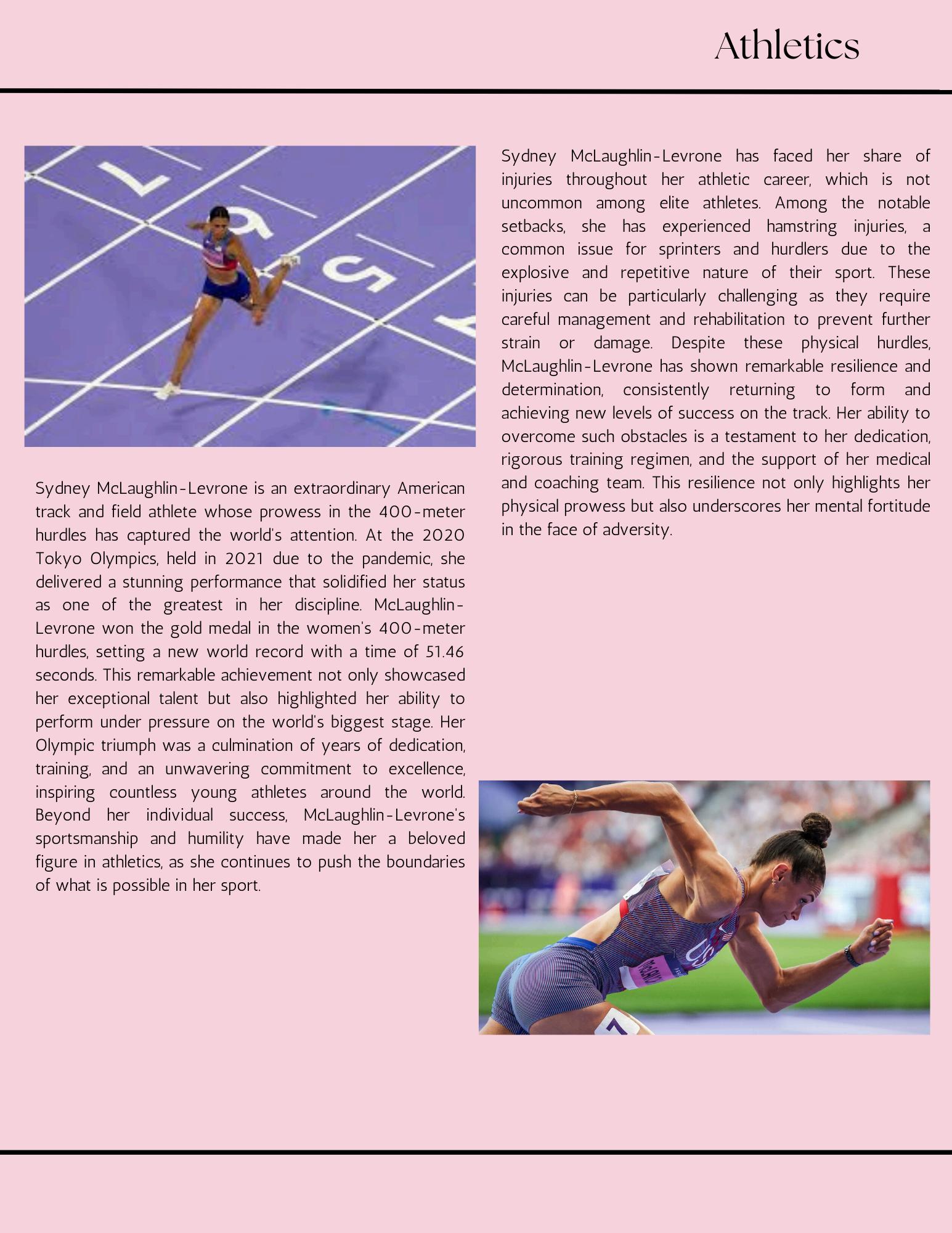

A r t w o r k b y F E M I S H i n t e r n : A b i B r u n o

AsIillustratedthisimage,Icouldn’t helpbutthinkofmycollege roommate.Sheisalesbianwoman whodressesingendernonconforming/masculineclothing.

Onedaywewenttothemall,andshe walkedrightovertothemen'ssection, Ifollowedherandendedupbuying myselfashirtfromthatsectionas well.

Sincethen,Idon’trestrictmyselfwhen shopping-I’llbrowsethewholestore regardlessofthetargetedgender.My roommateopenedupabouther experience,stating:

“Iabsolutelythinkpeoplejudgemebecauseofmygenderrepresentationand howIexpressmyselfthroughdressandeverythingelseexternal.Notallbad judgment,butdefinitelynoticeable.AssumingIjustammoremasculineinside too,andthatmaybeIwanttobeaboy,likeIgetmisgenderedsometimes "

Aboutherpartner:

"Mygirlfriendisveryfeminine stillalesbianbutveryfeminine She’shadpartners notbelieveherthatshe’sactuallysolelyalesbian,andmanymenespecially don’tbelieveherandjudgeherfornotbeing‘gayenough.’

The Journal of Feminini.es is the first academic journal devoted to the study of Feminini;es and uniquely offers an outlet for scholarship on femininity. The Journal of Feminini.es cul;vates and unifies the field of Feminini;es by publishing content that advances theories and methods in the study of femininity. The journal seeks to challenge and re-examine the taken-for-granted norms and associa;ons of femininity and to treat Feminini;es as an academic discipline similar to others that focus on par;cular social dimensions. Ar;cles that appear in the Journal of Feminini.es contribute to deeper and more complex understandings of femininity

Need a passion project to fill your credits or your soul? FEMISH has remote interns and tons to work on from writing & editing, photography, social media content, research, event planning, and community organization. Join the interns already on our team for fall! Apply Here!

Wewillneverstopsharingresearchandstoriesto createabondedcommunityofchangemakers. Femmephobia&Gender-policingareprohibiting trueequality,andwehavehadenough.

FilloutourContributorformbelowandseehowyou canaddyourvoicetoournonprofitorganization's platforms.