9 minute read

PADDLE SMARTS

by theensign

Paddling rivers and creeks

BY JIM GREENHALGH

►Paddling inland rivers and creeks can be fun as it offers changing scenery in a more protected environment than open water, and the current can help the paddler cover more distance with less effort.

Many people exclusively paddle rivers or creeks as they may not feel comfortable in open water with the possibility of rough seas. Paddling inland rivers and creeks can offer a more protected environment with flatter water and put the paddler closer to the safety of land. The river environment often requires different equipment depending on conditions While paddling rivers and creeks can offer more safety, there are also different hazards that the paddler must prepare for. Here, we discuss some of the equipment, trip planning and some hazards that paddlers may encounter on rivers and creeks.

Paddling rivers and creeks versus open waters

Paddling rivers and creeks is different from paddling the open waters of lakes, bays or the ocean In rivers and creeks, the entire body of water flows downhill with force, carving a channel that ultimately takes it to sea. At each bend in a river, you can expect a shallow area or sandbar on the inside with a deeper, scoured-out area around the outside of the bend. Rivers and creeks are classified on a scale of navigation difficulty from Class I (easy) through Class VI (extreme rapids). Most paddlers can safely paddle up through Class II. Classes III and above get into serious white water, requiring different skills and equipment that are beyond the scope of this article.

Paddlecraft for river paddling

Most paddlecraft can be used on rivers and creeks; however, some materials are better choices for this environment. In the open waters of lakes, bays or the ocean, many paddlers prefer a composite boat made of fiberglass, Kevlar or carbon fiber. The skin of these vessels offers less resistance and will slide through the water more efficiently, requiring less energy to paddle. When paddling rivers or creeks, a polyethylene or other flexible plastic-type hull is preferred. Rivers and creeks may be lined with logs or rocks that can do serious damage to the rigid hull of a composite boat.

A flexible plastic boat can slide right over these obstructions with nothing more than simple scratches. Also, I recommend using a paddle without the Mylar paddle reflectors, offered in the vessel safety check program. Impact from rocks, logs or other debris will damage the reflectors, and they usually aren’t needed to warn other vessels of your presence in that environment. I use a paddle without reflectors when navigating rivers and creeks.

Trip planning

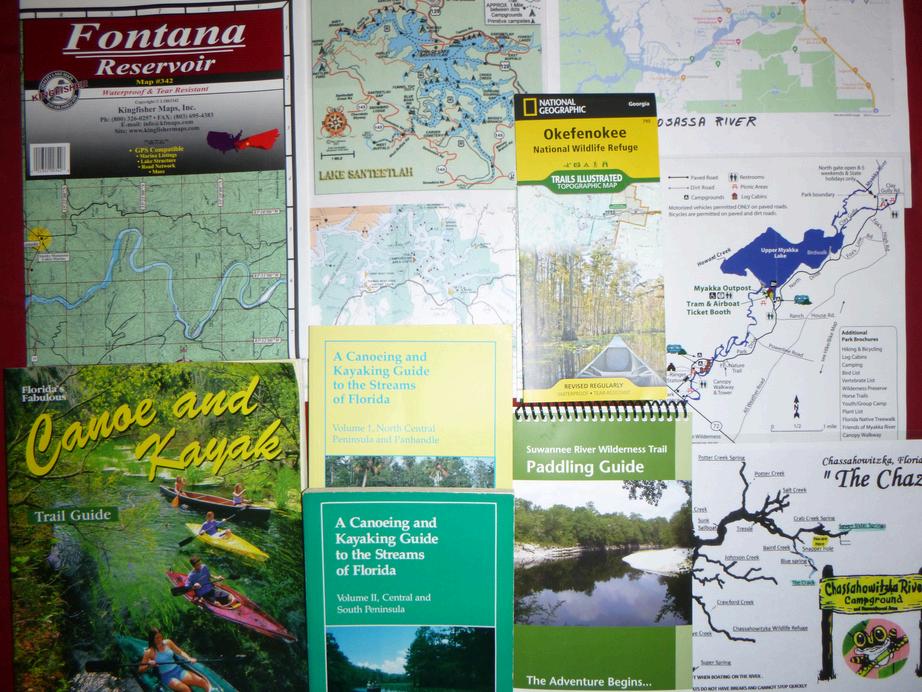

There are many resources available to plan trips on rivers and creeks. Online you can find maps of popular streams; simply search “map of (name of river or creek).” Unlike nautical charts, most of these maps do not follow any standard, so look at the legend if available. You can print maps of rivers and creeks using Google Maps or other sites with your home computer. Many paddlers navigate directly on the water using cellphone apps or a handheld GPS. There are also many guidebooks available, usually covering a specific state or geographic area, listing nearby rivers, creeks or other inland waters. These books list the locations, display maps, launch locations, distances between segments and other pertinent information. River gauge information on specific rivers and creeks can often be found online.

The U.S. Geological Survey maintains a site, USGS WaterWatch, which shows the latest information and lists many rivers and creeks throughout the US These online gauges display much information, but most useful to boaters is the current “stage” of a river or creek in feet. They also indicate current water levels from low to flood stage and include graphs indicating if the river is trending up or down.

One of the best sources of information is local knowledge, which can be obtained from a local paddling outfitter if available. Local outfitters know the latest realtime river conditions, and many police them regularly to clear deadfall and keep them open for navigation.

There are two ways to operate a river trip; up and back or a shuttle. Going up and back means you park and unload the gear at one launch and then paddle upstream, turn around and return. It is better to paddle upstream first and return downstream when you have waning energy. Shuttle trips are fun because you paddle downstream the entire trip, and you can paddle a longer distance without covering the same territory twice. The downside is that you have to organize a group shuttle, staging vehicles at the upstream launch and at the downstream pickup, which can be time-consuming. The alternative is to hire a local outfitter that can shuttle the group and equipment using commercial vehicles.

Paddling hazards

When paddling on a river or creek, remember that the entire body of water is moving downhill. Any vessel traveling downriver with the current will be less maneuverable. Paddlers need to keep this in mind when encountering obstructions or other boat traffic. At higher speeds, obstacles come up much faster, so keep an eye out front and be ready to take action to avoid collision. Boats proceeding upriver are more maneuverable and thus have more ability to avoid obstructions and downbound traffic.

One of the most common hazards paddlers will encounter on a river or creek is a “sleeper,” a rock or log just below the surface.

This is one reason I recommend using a polyethylene-type boat as it will more easily slide over a sleeper, avoiding serious damage to the hull. Many sleepers on a forested river will be deadfall trees that have collapsed into the river. Often deadfall will block a river, requiring paddlers to haul boats over, under or around obstructions, or terminate the voyage and return to the launch.

One of the most dangerous hazards in river and creek paddling is a “strainer” an area where water flows through fallen logs, limbs, foliage, rocks or other material and acts as a sieve to trap any floating material or debris, including swimmers. I have been involved in two rescues where a capsized paddler was pinned against a strainer in a slow-moving stream. The water pressure holding a swimmer against a strainer, even in slow-moving water, can be shocking. Strainers can be deadly, and rescuing someone caught in one can be difficult. Paddlers should always look out for and avoid strainers

When paddling a river strewn with rocks, logs, sleepers and strainers, try to navigate your boat through the “tongue.” Water flowing through obstructions creates a visible V in the clear area between obstructions. The V points downstream and is bordered by lines of whitewater, giving it the appearance of a tongue. This is the area that is usually free of obstruction with deeper water. Also, if you end up in the water in a flowing river, always maneuver your body so that your feet are pointed downriver to protect your head from impact.

On some rivers, paddlers may encounter a low head dam. Often unmarked, these dams are much lower than major dams, many only several feet high, and may be difficult to see when approaching from upstream. Water flows continuously over the entire crest of the dam, and they can be dangerous for unsuspecting boaters. Often low head dams trap strainers on both sides of the structure and may contain large and dangerous hydraulics on the downstream side. Paddlers should never attempt to paddle over a low head dam.

Of course, paddlers should always be on the lookout for other boat traffic, especially fast-moving powerboats. Consider that powerboaters need to stay in the deeper natural channel of a river, so paddlers should try to stay to the side out of the channel. It’s best to paddle on the right side of a river; however, paddlers will often have to switch back and forth to avoid shoals, rocks, logs or other obstructions, especially on a winding river. Also, listen for powerboat traffic that may be coming around a blind bend and try to position your paddlecraft in a safe place to avoid unexpected traffic when nearing a bend.

Group communication on rivers

While paddling with groups, my experience has shown that marine VHF radios simply do not work on winding rivers. Marine radios operate in the VHF band, a frequency range that requires a line of sight. Paddlers often carry a handheld marine VHF with an antenna that is at best 2 to 3 feet above the water, and as paddlers round a bend out of sight, communication is lost.

When paddling with larger groups, my paddling club has found that Family Radio Service radios are ideal for group communication. FRS radios operate in the UHF band, which is not affected by intervening structure, and they do not require an FCC license. Communication is clear even when forests, riverbanks, concrete structures or buildings come between users.

Intervening structure does reduce the advertised range, however. Even in deep forest, we usually get a half-mile range, plus or minus, which works fine to keep a group of paddlers in contact. On a river, a large paddle group may get strung out over a mile or more, so we place FRS radios with the lead, the sweep, and some in midgroup. This usually keeps the entire group in contact with each other.

Paddling rivers can be fun, and paddlers can avoid the sometimes-rough conditions found on open water. Often, you will see more wildlife under the shady canopy of a forest while being closer to the safety of a riverbank. There are other hazards to consider, but proper planning and preparation will make exploring rivers and creeks a pleasant and safe experience. ■

About the Author

Jim Greenhalgh of St Petersburg Sail & Power Squadron/22 is a senior navigator, vessel examiner, and instructor, having taught boating safety and navigation since 1991. He draws on his vast sail and powerboating experience as a lifelong boater and avid sea kayaker. Jim leads trips for the Kayak Adventure Group, a sea kayaking club based on Florida’s west coast that he co-founded He also wrote Navigation Rules for Paddlecraft, a must-read for all paddlers