Display until August 15, 2024 / $11.95 WHAT NURTURES BLOOMING?

MAVIS STAINES: LIFE AND LEADERSHIP IN DANCE

retirement POLE, OPERA AND ‘THE WAY THEY COME TOGETHER’

Q & A

multidisciplinary artist Khadija Mbowe ON EMERGING spring 2024

Reflections on becoming artists

Celebrating Staines ahead of her

A

with

The Fifth Dance: Celebrating Five Years

A story about creating a home base for dance

32 Rusty Enough to Be New

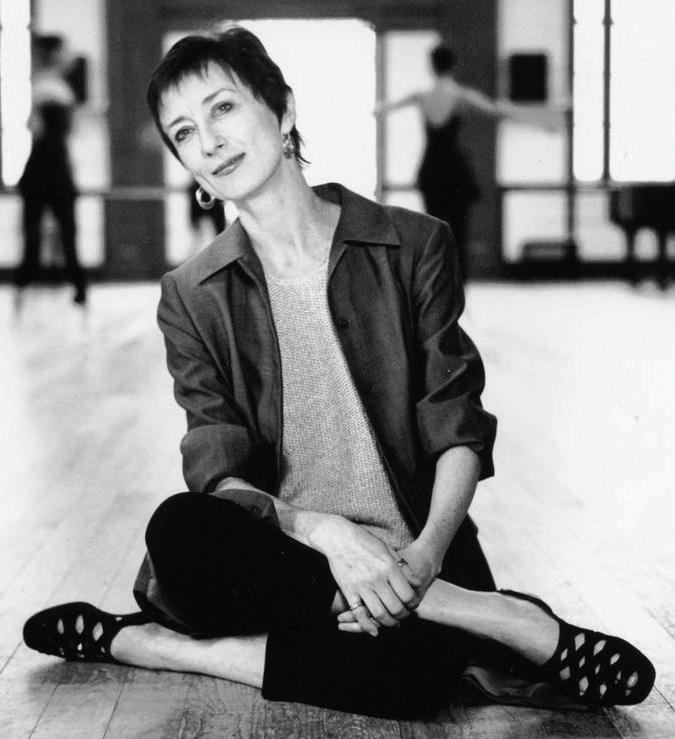

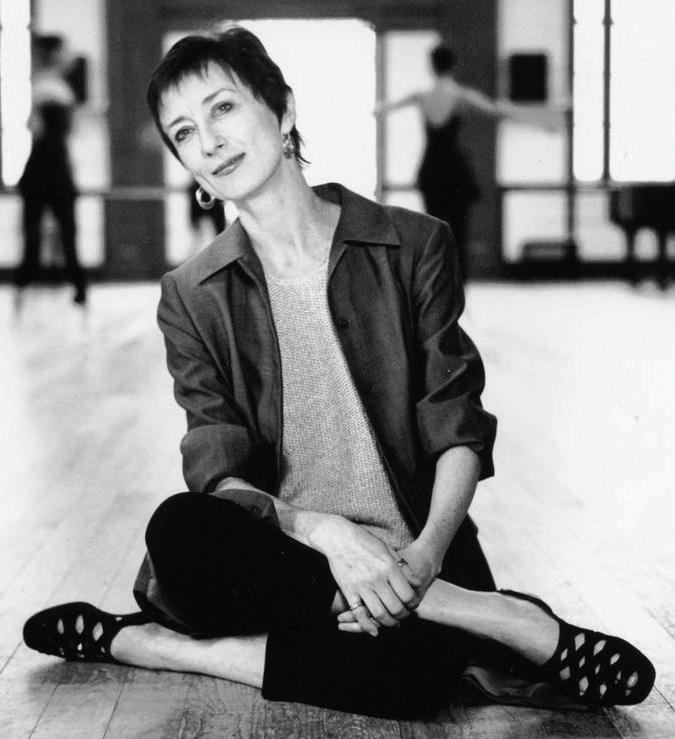

Mavis Staines: Life and Leadership in Dance

Celebrating the work and vision of Staines ahead of her retirement from Canada’s National Ballet School by grace elliott

ESSAY 22 What Nurtures Blooming? A collective photo essay on the process of becoming

SPOTLIGHT

I Bring My Dancer-Self Everywhere On dance-based interdisciplinary research by emily caruso parnell

A re-emerging dancer reflects on the precarious and cyclical waves of a career in dance by roxy menzies HISTORICAL MOMENT

33 Marie Chouinard: The Early Years

An interview with an iconic figure of dance by clara chemtov

34 Rediscovering the Rhythm

Tips on returning to dance after an injury by geneviève renaud

thedancecurrent.com 3 32 28 14 WHAT NURTURES BLOOMING? Reflections on becoming artists MAVIS STAINES: LIFE AND LEADERSHIP IN DANCE Celebrating Staines ahead of her retirement POLE, OPERA AND ‘THE WAY THEY COME TOGETHER’ A Q&A with multidisciplinary artist Khadija Mbowe ON EMERGING 2024 DEPARTMENTS 4 Masthead 5 Now Online 7 Editor’s Letter 9 Contributors POSTSCRIPTS SPONSORED CONTENT

20

REFLECTIONS

TIPS

CURRENTS WHAT’S ON? 10 Event Previews FEATURES FEATURE PROFILE

14

PHOTO

RESEARCH

ON THE COVER Q & A 12

Way

Together’ An interview with multidisciplinary artist

Volume 27 Issue 2 spring 2024 Left to right: Photo courtesy of Roxy Menzies; Video still courtesy of Emily Caruso Parnell; Mavis Staines / Photo by Dan Cremin On the cover: Khadija Mbowe / Photo by Madeline Robertson contents

28

Pole Dance, Opera ‘and the

They Come

Khadija Mbowe

Wishing you a great rest of the day.’ Mavis takes an extra seven seconds to treat you like a human she values. If Mavis has time to do it, we all have time to do it,” Dalrymple says.

Staines’ colleagues and former students speak so highly of her that I have to know the secret behind her leadership. There seems to be such a strong ideology when it comes to lifting people up, but really, she hasn’t put that much thought into it. “I don’t usually think like that, in terms of having a philosophy,” she says. “I just get very excited about drawing people into ideas, and I discover, as I do that, how smart so many people are and how much they have to contribute.”

Staines’ mother always wanted to take ballet classes, but living her girlhood during the Depression and then her adulthood as a British war bride meant that studying the art form wasn’t an option. She told herself that if she ever had daughters, they would take ballet lessons. Jump several years and she had three, but money was still an issue.

She soon discovered that food stamps could buy a pair of children’s ballet slippers and that their community centre in Ottawa offered free classes. Staines’ older sister was enrolled, but after five lessons, she absolutely hated it. “So my mother thought, OK, if each of my daughters wears the shoes five times, then it’s not a complete waste,” says Staines. She was up next. “I totally fell in love with the ballet class right from the word go.” At six years old, just one year after NBS was founded in 1959 by Celia Franca and Betty Oliphant, she declared to her parents she would be a ballet dancer. “Don’t be ridiculous,” they said.

Two years later, the family moved to Vancouver, and Staines’ parents told her they couldn’t find a ballet school, a fib to discourage her sugar plum wishes. But when a school nurse recommended ballet lessons for her younger sister, Staines got to go too. Back where she belonged, she began to dream of auditioning for NBS one day.

Unbeknown to the little ballerina, her teachers were contacting Oliphant to tell her about Staines. “Every time Betty came out to Vancouver, she’d phone my parents and say, ‘Can Mavis audition?’” says Staines. The

I dreamed about having an opportunity one day ... where I could galvanize the community and make systemic changes.

– STAINES –

answer was always no, until she was in Grade 8 and Oliphant said that she was probably too old. Staines calls those the “magic words”; she was finally allowed to audition, her parents thinking that if she were too old, there was no risk of her getting in. Luckily, they were wrong. After school staff spent two hours convincing her parents, she attended the summer school and then, finally, the full-time program. “How extraordinary that my parents ultimately let me do this, with the promise that I would always, always, always keep my grades up in academic school,” she says. “Over time, they became very proud of me.”

Little did everyone involved in getting young Mavis Staines to Canada’s National Ballet School know that their efforts were going into training the school’s second artistic director. “I loved my studies, but even as a kid, I was aware that there were ballet practices that were really on track and resonated and other practices that were either traditions that had passed their expiry date or were counterproductive, and then some that were destructive,” she says. “I dreamed about

having an opportunity one day to have a role where I could galvanize the community and make systemic changes.”

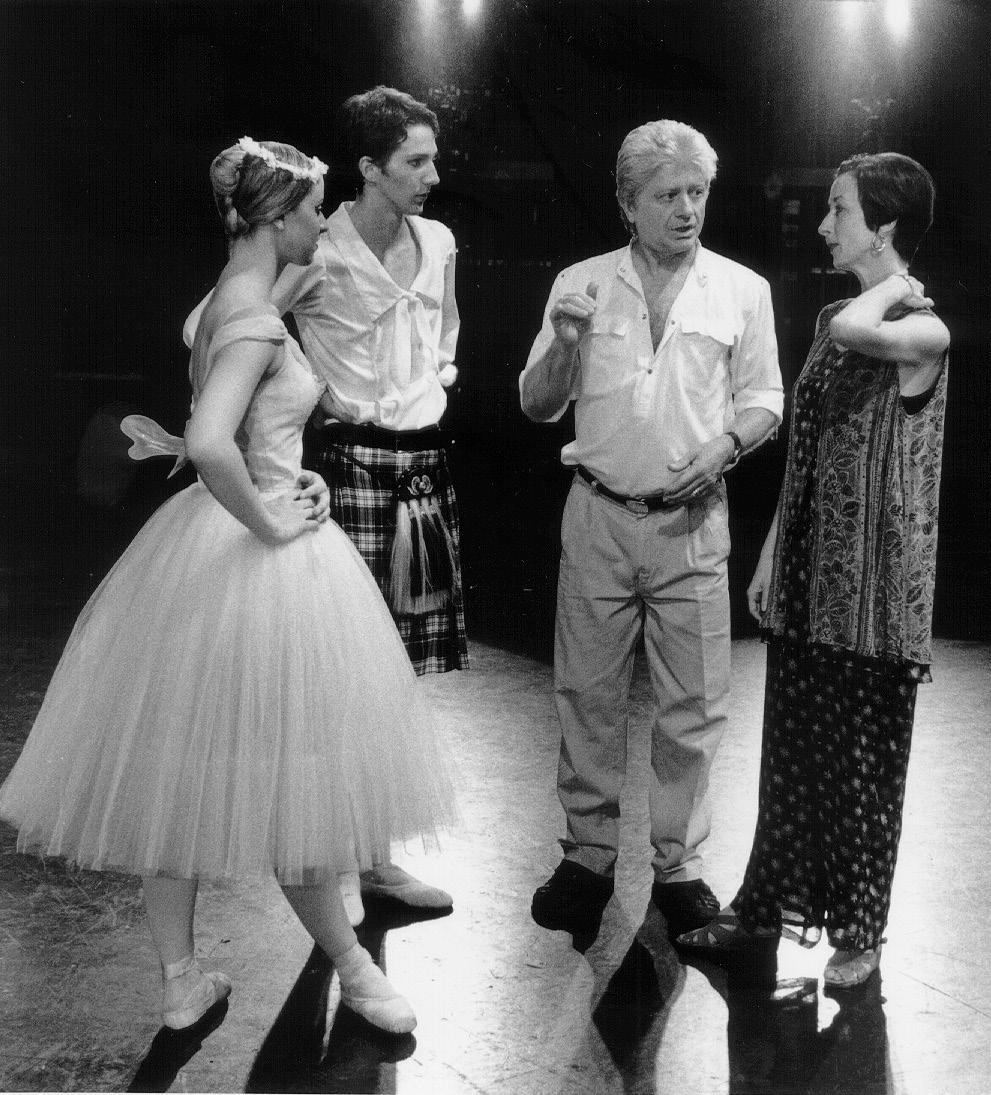

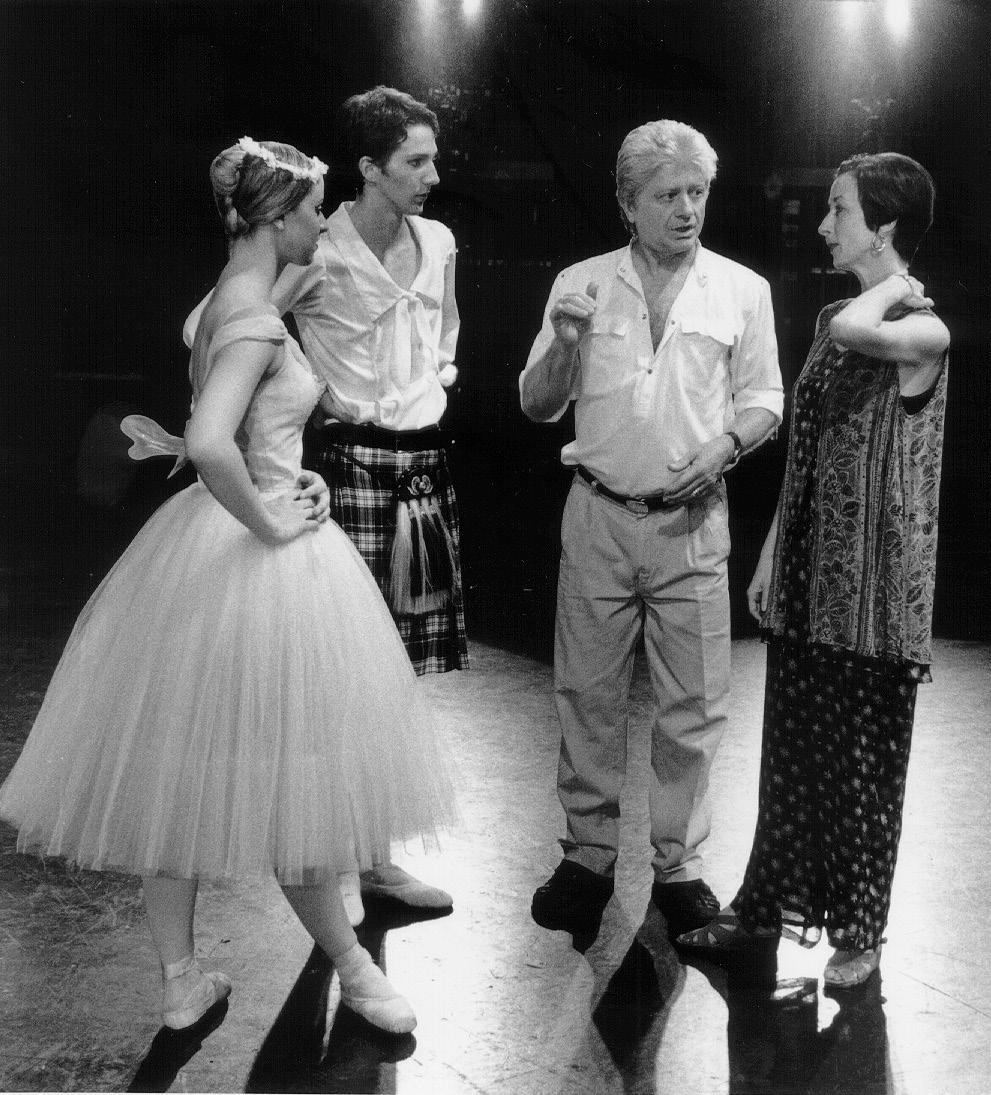

That opportunity emerged in 1983 when, after dancing as a first soloist with The National Ballet of Canada and the Dutch National Ballet, then breaking her wrist, Staines joined the faculty at NBS. Shortly after, Oliphant asked if she would train to succeed her as artistic director. “I immediately said yes,” says Staines. “[Oliphant] said, ‘Don’t you want to go home and think about it?’ and I said, ‘No, something has just spoken to me internally.’” In 1989, after apprenticing under Oliphant, Staines became artistic director.

One of Staines’ first and top priorities was to help dancers find their voices, which included advocating for better mental and physical conditions. Throughout the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, dancers were expected to be excessively lean. Staines notes that it was common across the globe for teachers to weigh their students and publicly shame their bodies, a practice she links with an earlier (and now defunct) belief that humiliation would motivate discipline. The quest to advance dancer health and well-

16 the dance current SPRING 2024

mavis staines

Staines as a student in Grade 9 at Canada’s National Ballet School / Photo courtesy of Staines’ personal archives; Staines with NBS students and Sergiu Stefanski / Photo courtesy of Canada’s National Ballet School

Rediscovering the Rhythm

A physiotherapist’s tips on returning to dance after an injury

by geneviève renaud

Suggestions in this article are not intended to replace individualized health care

Whether it’s a sprained ankle, muscle strain or stress fracture, injuries are often unavoidable and can sideline both recreational and professional dancers. According to a 2005 survey conducted in the United Kingdom, eight in 10 dancers have at least one injury a year, typically caused by overuse or acute incidents. Many dancers will return to preinjury function, but some injuries can also lead to disability or be career-altering.

What sets apart successful dancers is how they navigate recovery, turning setbacks into comebacks. Dance is not just a physical activity; it’s an art, a part of one’s identity and a source of happiness. Because of this, a successful return to dance after injury must include physical rehabilitation coupled with mental health support and rediscovery of the joy of movement.

Early injury recovery

Returning to dance too quickly can worsen an injury and prolong recovery, so it is advisable to seek early guidance from a health-care provider to support your body’s healing process. Protecting the injured area is sometimes needed; applying compression can help decrease swelling; and trusting your body has been shown to support early healing. It is important to stay optimistic while participating in a gradual rehabilitation program, including mobility, strength, proprioception and cardiovascular exercise.

Goal setting

Healing is often non-linear, with improvements and setbacks throughout the process. An appropriate rehabilitation plan includes setting realistic goals, which might include missing performances, competitions and even reimagining movement after an injury. It is a great practice to celebrate

every milestone along the way and take the opportunity to focus on technique and healthy habits. Injuries can sometimes allow us to find time for sleep, cross-training, nutrition and psychological well-being. Setting goals in these areas can make us stronger in the long run.

Mental and emotional support

Physical injuries can cause grief, anxiety or fear, negatively affecting a dancer’s mental well-being. Concerns over reinjury, professional status and overall performance are common and can affect the recovery rate. It is essential to acknowledge these feelings and seek support. Visualizations, meditation and other mindfulness techniques can help dancers stay optimistic during recovery. In some cases, clinical or sports psychologists are required to ensure psychological recovery before returning to movement and will recommend additional support if needed.

Modifying in the studio

Some dancers benefit by staying in the studio through recovery, which can allow them to continue learning choreography and train non-

injured body parts. In these cases, a healthcare provider can guide a gradual return and communicate the plan with your studio or company. Dancers may also need to work with their instructors or choreographers to find alternative movements that accommodate their injury while still allowing artistic expression. Dancing with and after an injury can require us to challenge preconceived views on dance, allowing us to redefine our art form.

Gratitude

Recovering from an injury can provide a new perspective on dance and life. Some can experience a deeper appreciation for the body’s resilience, the support of loved ones and the opportunity to dance again. When physical and psychological rehabilitation are combined, dancers can emerge stronger, with increased motivation to train and a renewed sense of gratitude.

Finding joy

Injuries can have significant, long-term and sometimes permanent effects. Nonetheless, with patience, guidance and multi-faceted support, there are ways to return to dance, even if it is in new and modified ways. Above all, a return to dance is about rediscovering joy. Being grateful for movement – every plié, shuffle, turn, leap or gesture – is a celebration of the body’s ability to overcome adversity and thrive.

The Tips column is sponsored by physiotherapist Geneviève Renaud. genrenaudphysio.ca

Geneviève Renaud is a registered physiotherapist with 10+ years of experience in sport rehabilitation.

34 the dance current SPRING 2024 tips

Top to bottom:

Photo by Avi Richards, courtesy of Unsplash;

Photo courtesy of Renaud