Remembering

Graphic by Kaleb Searle

LOOKING BACK

These LSU student journalists captured Katrina’s impact

BY JASON WILLIS Editor in Chief

The night Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, thenLSU sophomore and The Daily Reveille journalist Ginger Gibson and her friends made inventive use of the weather.

They married suds with rain to make a slip-n-slide on a Twister mat between the East and West Laville halls. Booze might’ve been involved.

The next morning, Gibson encountered Reveille Editor in Chief Scott Sternberg on the Parade Ground. News was coming in that the situation in New Orleans was dire. Sternberg simply handed her a notebook and told her to start working.

Gibson joined The Reveille for “beer money,” she said, and now she was covering perhaps the worst natural disaster in U.S. history.

“That’s the day I became a reporter,” said Gibson, who went on to have a 20-year career in journalism that included stops at NBC News, Reuters and Politico.

The severity of the moment quickly set in for all on campus. School was canceled from Aug. 29 until Sept. 6, but not because the damage was particularly bad in Baton Rouge.

In the coming days, LSU would mobilize one of history’s most incredible relief efforts in a time when other state and national institutions failed to respond.

The Pete Maravich Assembly Center and other nearby facilities were transformed into the U.S.’s largest-ever acute care emergen-

cy center. 21,000 evacuees, many brought by helicopter, passed through in two weeks, with 6,000 treated there and 15,000 triaged and then referred to other facilities.

Baton Rouge became the most populous city in the state overnight. Traffic swelled. Families of students, many of whom had said their goodbyes just weeks ago, crammed into dorms, some with eight people to a room.

“It’s one of the many things about Katrina where you think about it 20 years later, and you just can’t place it into our current reality,” said Kyle Whitfield, then a freshman writer and now the vice president of consumer revenue at The Advocate | Times-Picayune.

Local journalists became an indispensable resource for emergency communication, especially in a region that was largely now without reliable cell service or power.

Reporters carried an immense burden, juggling the duty to tell a story and the torture of living it.

“What happens when you’re a local journalist and the trauma is in your backyard?” said Shearon Roberts, then a Reveille writer and LSU graduate student, now a journalism professor at Xavier University in New Orleans.

It was a responsibility also held by LSU student journalists, who watched as their university entered the national spotlight and whose very understanding of journalism was forged by thrusting themselves into the fire and chronicling Katrina’s aftermath.

‘The most important thing that I was ever going to do’

They may have been learning

how to be reporters in real time, but there was nothing amateur about how The Reveille rose to the occasion after Katrina.

“We were journalists,” Photo Editor Anson Trahan said. “We absolutely believed in what we were doing every single day.”

Still, it was difficult to find reporters willing to hit the ground running, Sternberg said. Half the staff was from New Orleans, he estimated, and were affected directly by the tragedy.

Those who sprang into action were fulfilling a public service. People living on campus had little access to information thanks to spotty internet and cell service. With most national and state media coverage rightly focused on New Orleans, there was surprisingly little competition in covering what was the disaster’s most robust relief effort.

Someone had to keep the campus informed.

What was happening? Where was there food available? When would classes begin again? Reveille journalists yelled out announcements in dining halls and appeared on the KLSU radio station, which ran uninterrupted throughout Katrina and in the days after, to give frequent news updates.

They were crisis communicators. At the same time, they told the heartbreaking human stories — of the nearly 3,000 displaced New Orleans college students who flooded into LSU, of the families that streamed into the city and dorms, of the campus locales that had been unrecognizably transformed.

DaTrina Hinton, a junior at the

LSUReveille.com

B-16 Hodges Hall

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge, La. 70803

time, described the scene at the PMAC in her story that became one of three headlining the newspaper’s front page in its first edition post-Katrina.

“The rancid smell of soiled adult diapers and water-soaked people floated through the air as patients seeking medical care waited in puddles of urine in the Pete Maravich Assembly Center,” Hinton wrote. “Although medical volunteers and EMT workers looked near exhaustion, they worked tirelessly without rest.”

It was especially striking, Hinton recalled, to see a place she’d gone into many times completely transformed.

“There was this atmosphere of despair. It felt heavy,” Hinton said.

Managing Editor Adam Causey chose to wait out the storm in his tiny north Louisiana hometown, Doyline. Even from there, he found stories to tell.

In nearby Lake Bistineau State Park, evacuees were allowed to take refuge free of cost. One particularly stood out to Causey — a 54-year-old woman from Mississippi who was unsure if her daughter, son-in-law and grandson had survived.

“She’s one that I wish I could follow up with,” Causey said, “and I hope that there was a happier ending to that story.”

The image that sticks in many of these student journalists’ minds spanned the front page of The Daily Reveille on Sept. 6, 2005, the day students returned to campus and the day of the newspaper’s first post-Katrina edition.

ADVERTISING (225) 578-6090

Layout/Ad Design ASHLEY KENNEDY

Layout/Ad Design REESE PELLEGRIN

CORRECTIONS & CLARIFICATIONS

The Reveille holds accuracy and objectivity at the highest priority and wants to reassure its readers the reporting and content of the paper meets these standards. This space is reserved to recognize and correct any mistakes that may have been printed in The Daily Reveille. If you would like something corrected or clarified, please contact the editor at (225) 578-4811 or email editor@lsu.edu.

ABOUT THE REVEILLE

The Reveille is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Communication. A single issue of The Reveille is free from multiple sites on campus and about 25 sites off campus. To obtain additional copies, please visit the Office of Student Media in B-39 Hodges Hall or email studentmedia@ lsu.edu. The Reveille is published biweekly during the fall, spring and summer semesters, except during holidays and final exams. The Reveille is funded through LSU students’ payments of the Student Media fee.

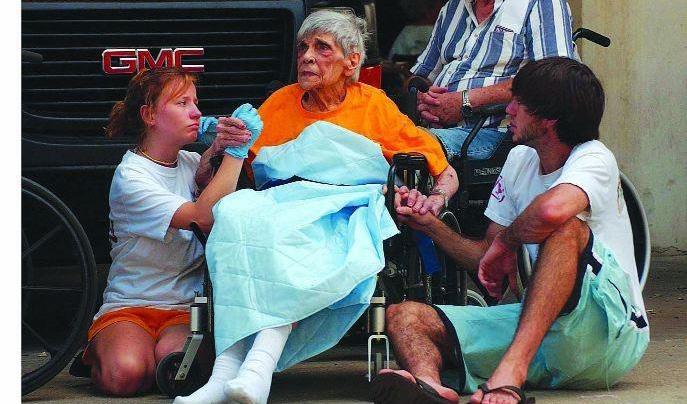

ANSON TRAHAN / The Reveille

Two LSU student volunteers comfort an evacuee from New Orleans as she waits to board a bus outside the PMAC on Aug. 30, 2005.

WHERE OTHERS FAILED

While other national and state institutions faltered during Katrina, LSU set a standard

BY JASON WILLIS Editor in Chief

Hurricane Katrina was marked by intense grief and loss for those on the Gulf Coast, but just as potent was a feeling of frustration toward authority.

It was a time of institutional failure. After the storm, state and federal groups like FEMA were painfully slow to respond.

LSU, however, met the moment by mounting perhaps the state’s most robust disaster relief effort to date.

“The university was transformed in a way that was mind blowing, and, honestly, very impressive on such short notice,” said Marissa DeCuir, an LSU sophomore and writer with The Daily Reveille at the time.

The Superdome in New Orleans became the image of Katrina. But it was another arena 73 miles northwest, the PMAC in Baton Rouge, that transformed into what was the largest acute care field hospital in U.S. history.

21,000 evacuees went through it in two weeks, with 6,000 treated there and 15,000 triaged and then referred to other facilities. A staff made up of 1,700 volunteer medical personnel and 3,000 volunteer citizens, many of them LSU students, worked tirelessly.

The inflow of evacuees to treat didn’t let up. Helicopters kept arriving, landing on the grounds of the Bernie Moore Track Stadium that was used as a helipad and fill-

ing the air with a relentless chopping sound.

The PMAC wasn’t the only historic relief center on LSU’s campus. The John M. Parker Agricultural Coliseum was the site of the largest pet rescue in U.S. history, as evacuees dropped off pets that they couldn’t take care of in the short-term or permanently in some cases. 2,300 total pets passed through.

Clearly, LSU had set a precedent. Recognizing that, the university afterwards published a book titled “LSU in the Eye of the Storm: A University Model for Disaster Response” and mailed it to

schools around the country. It documented how LSU prepared for and attacked Katrina’s aftermath in the hopes that other schools might use it as a reference.

Presiding over the relief effort was university Chancellor Sean O’Keefe. His hiring in February of that year was criticized by many because of his lack of experience in higher education. One thing he certainly had experience in, though, was crisis.

O’Keefe previously served as the U.S. Secretary of the Navy under George H. W. Bush and NASA administrator under George W. Bush. He’d stood on landing strips

as Navy planes crashed, was in the West Wing on 9/11 and oversaw the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle.

“I’ve made enough mistakes to fill three volumes,” O’Keefe said. “To at least be around that and engage with that made a difference, at least in terms of how to start.”

So why was LSU the site for this historic effort? For one, it had power — it generated its own on campus.

But also, O’Keefe felt, it had a “public service obligation” to lead the way.

Maybe the largest administrative burden was the huge influx

of displaced New Orleans university students that LSU opened its doors to offer them a sense of normalcy.

There were 3,285 displaced students admitted and approximately 2,800 enrolled.

“During the normal admissions process, it takes us about a year to admit and register approximately 5,000 new students,” LSU’s vice provost for academic affairs said at the time. “We did 60 percent of that number in 10 days.”

Many of the students did not have proof of enrollment, having lost documents in the storm. The general policy on LSU’s end was leniency.

To accommodate the new enrollees, LSU added 80 new class sections and took in volunteer instructors, including some who were previously working at New Orleans universities.

There were unsavory, unimaginable parts of Katrina encroaching on LSU’s campus, like the designation of an on-campus morgue.

But the takeaway was resilience, generosity and, above all, remarkable efficiency. It took citywide contributions to help take in a region that was “on its knees,” said Kyle Whitfield, then a freshman and now the vice president of consumer revenue at The Advocate | Times-Picayune.

“LSU, the city of Baton Rouge… I’m no historian, but really, [Katrina] was probably one of their finest hours as institutions and as cities,” Whitfield said.

Contraflow plan used during Katrina made by LSU professor

BY AIDAN ANTHAUME Staff Writer

When Hurricane Katrina bore down on Louisiana in 2005, a traffic plan designed at LSU moved hundreds of thousands out of danger. The system, known as contraflow, reversed interstate lanes to double outbound traffic and was the product of research led by LSU civil and environmental engineering professor Brian Wolshon and his students.

The idea had taken root years earlier when Wolshon had just moved from Michigan to LSU in 1997. A traffic roadway safety expert, he was still new to Louisiana when Hurricane Georges forced an evacuation that fall. Watching it unfold on television, he saw gridlock stretching for miles.

“I just assumed that there was a big playbook that they would open up if there was a big storm, and they would know what to do,” Wolshon said. “As I was watching it on TV… it was not good. There were traffic jams all over the place.”

He quickly realized the problem wasn’t too many cars; it was

poor coordination.

“The people who are the experts in traffic in the state of Louisiana, namely the Louisiana DOTD [Department of Transportation and Development], weren’t really involved in the process at all,” Wolshon said. “There was almost a disconnect between the emergency management people and the transportation people.”

Wolshon and three of his civil environmental engineering students began researching trafficrelated evacuations.

“The more we would look, the less we would find,” Wolshon said. “It fell between the cracks. It wasn’t transportation enough to be a transportation problem, and it wasn’t an emergency problem enough to be an emergency management problem.”

They began collecting every evacuation plan and document they could find from hurricaneprone states.

“If we’re going to start this, we’ve got to figure out what everybody knows and what everybody’s doing,” Wolshon said.

Wolshon had students run traffic simulations to see how differ-

ent scenarios might play out. The models compared evacuations with and without contraflow and revealed a dramatic difference in how quickly cars could move.

“I would have them run these simulations with and without contraflow, and it was obvious that contraflow would be a huge benefit,” Wolshon said.

Not long into his research, the U.S. Department of Transportation contacted Wolshon about the method. Officials had already spoken with 14 states, all of which recommended him as the expert on the subject. One of Wolshon’s students was asked to turn her thesis on contraflow into a 10-page report for federal officials.

“They said, ‘Can you send us 10,000 copies?’” Wolshon recalled.

The reports, stamped with LSU’s name, were shipped to Washington, D.C., and mailed out to police departments, transportation offices, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and emergency managers across the country.

ANSON TRAHAN / The Reveille

Volunteer medics transfer a New Orleans evacuee from a naval helicopter into the triage center at the PMAC late Aug. 30, 2005.

LUCAS HALEY / The Reveille

FROM THE ARCHIVES

How LSU athletes like Andrew Whitworth lent a hand in Katrina

BY ELLIOT BROWN Former Staff Writer

PMAC turned into hospital Families joined students in LSU dorms

BY CHRIS DAY Former Staff Writer

This article was originally published on Sept. 6, 2005.

Crates of syringes, urine cups, medication and IV tubes surround clusters of wall-to-wall hospital beds in the Pete Maravich Assembly Center. Hundreds of military police are scattered at building entrances. Buses and helicopters continue to rush patients in and out of the building as teams of doctors and nurses from across the country frantically try to save lives.

The aftermath of what some have called the most catastrophic natural disaster has come to campus.

“This is 9/11 in slow motion,” said Chancellor Sean O’Keefe of the worsening state of emergency during the week following the category four storm.

The PMAC is the largest acute care emergency facility in the state. An acute care facility is equipped to provide medical and surgical care for seriously ill or injured people.

Treating about 5,000 patients in the past week, officials say the facility plays a crucial role saving the lives of evacuees hurt by Hurricane Katrina.

Next door, the Carl Maddox Fieldhouse also meets the needs of evacuees. While the PMAC is operating as a temporary hospital, the fieldhouse is a care facility also lined with beds and equipment.

see PMAC, page 8

This article was originally published on Sept. 6, 2005.

The season-opener against North Texas had been cancelled. There was no word on whether or not it would be played. The next game against Arizona was questionable.

Junior wide receiver Craig Davis did not seem to care last Wednesday.

“The last thing but on my mind right now is football,” confessed the junior receiver and New Orleans native.

Davis said most of his immediate family made it out of New Orleans, but said his family’s house near the West Bank was “pretty much gone.”

Senior receiver Skyler Green, also from the West Bank, had his thoughts away from the field after Hurricane Katrina. His family made it safely out of the city and had moved into the receiver’s two bedroom apartment near campus.

“I’ve got a houseful right now,” Green said. “Maybe eight or 10.”

Green said Wednesday that he is positive his family is safe, but was still unsure about the whereabouts of some of his girlfriend’s family.

“My girlfriend doesn’t know where her grandfather is right now,” Green said. “All we can do is pray that he’s OK. She has a cousin also down there and a grandmother. She has a couple of people stuck in the storm, and she hasn’t gotten in contact with anybody.”

see ATHLETES, page 8

Displaced students struggled to focus on academics

BY SHEARON ROBERTS Former Staff Writer

This article was originally published on Sept. 8, 2005.

At the end of the day, it’s pure physical and mental exhaustion for Gabriela Sandoval, business administration senior from the University of New Orleans. She just enrolled at LSU after Hurricane Katrina submerged her campus and her apartment.

Sandoval said she battled to keep her mind from wondering off a discussion in her geology class, as she tried to shake thoughts of lost belongings and her flooded apartment. To top it off, she then had to endure the journey back to Geismar, La., the nearest place she could find an apartment.

“It’s really hard to focus,” she said. “At the beginning I was re -

ally excited, and now I am like: should I quit and just wait to finish up next semester at home?”

Sandoval is one of many new and returning students and faculty, both struggling to put together the pieces Katrina left behind, while having to press forward with the academic agenda at hand — a constant cycle of classes, homework, studies and research — and for professors, preparing lectures and revising syllabi.

“There is nobody to whom life is the way it was 10 days ago,” said Phyllis Lefeaux, LSU clinical social worker with Mental Health Services, as she and other staff wrapped up the day at the Student Union. They are holding a special “Coping with Katrina,” service to council students.

“How hard it is to focus depends on what you’ve been through and what you expect to go through during the semester,” Lefeaux said.

For Sandoval, New Orleans was her temporary home. She left Honduras to attend college in the city. Brandon Watson, biology freshman from Dillard University, said he turned down other college offers to stay in the city he grew up in and loved dearly.

“That was just two adjustments to make in a matter of one month,” Watson said. “It was such a quick change because I was really enjoying Dillard, but somehow I’m going to have to make out and manage here.”

Students housed in LeJeune and Beauregard halls in the Pentagon have already begun to reconnect and form support groups allied along the lines of their devastated colleges.

Bronwyn LeBlanc, UNO chemistry freshman, echoed Watson’s sentiments. She too recalled just settling in and making friends the Friday New Orleanians were asked to evacuate the campus.

And now they are left to start over again.

“I was a freshman for five days, and it was a good five days,” LeBlanc said. “Now I’m sitting in trig class here. I was so tired, and I was just trying to make it through the day.”

Now that she found some other displaced UNO freshmen on campus, LeBlanc said she knows she’s not alone.

At a bench in the Pentagon near LeBlanc, Terrica Hamilton, Itohan Osemwenkhae and Naudia Falconer, who became friends while on UNO’s track team, evacuated to Baton Rouge as a group and decided to enroll at LSU together. Sticking together, they said, is what is allowing them to deal with their circumstances.

“I feel displaced,” said Hamilton, who is an early childhood education sophomore. “I feel like

ACADEMICS, page 8

BY JULIE GINTHER Former Staff Writer

This article was originally published on Sept. 6, 2005.

After students waved off their parents on move-in day, few thought they would be living with them again after only one week of freedom.

Hurricane Katrina’s devastation left many New Orleans residents homeless and stranded in multiple cities. The University is allowing students to house their families in residential halls to ease the strain on Baton Rouge housing.

Meggan Canale’s two-person dorm is now home to her family of four.

“It’s very cozy,” said Canale, marketing freshman and Destrahan native. “My mom and sister sleep on our futon, and my dad is sleeping on my roommate’s bed until she gets back.”

The Canale family left its hotel in St. Francisville on Wednesday, but Canale said she does not mind the company in her Evangeline room.

“It’s an inconvenience, but I appreciate them being there,” Canale said. “I don’t feel safe going to school when there are people on campus that don’t belong.”

John Canale, Meggan’s father, said he hopes to go home this week when the power returns but that the accommodations have been “wonderful.”

“All my life, I’ve dreamed of sleeping in a girl’s dorm,” John Canale joked. “Unfortunately, it came 30 or 40 years too late.”

Meggan’s father added that the University staff has been hospitable, citing a night when the Highland Cafeteria staff fixed the family a meal 20 minutes after the cafeteria closed.

But not all students were ready to have their parents living with them again.

“It has been draining and stressful,” said Rachel Spinner, sociology senior and Kenner native who is living with her mother in East Campus Apartments. “I know my mom doesn’t want to be there, but she can’t help being there.”

Spinner, unlike Canale, has been on her own longer and said she was not prepared to be living with her mom again.

“I haven’t lived with her since I was a senior in high school,” Spinner said.

Spinner said 10 people and her three cats stayed with her during the hurricane.

“The Tulane students who were with us went home,” she said. “My

JOEY BORDELON / The Reveille Junior running back Justin Vincent helps unload blankets and toys from a trailer at St. James Episcopal Church in Baton Rouge on Sept. 5, 2005.

NEWS HURRICANE SEASON

Experts explain this season’s hurricane predictions

BY EMILY BRACHER Staff Writer

South Louisiana is known for many things, like its food, its culture and its abundance of bad weather.

The statistical peak of hurricane season is Wednesday and there have been six named storms so far. Associate professor of oceanography and coastal sciences Paul Miller said that after Sept. 10, the possibility of a storm goes down.

Miller is the supervisor of the Coastal Meteorology “COMET” Lab. He said this year’s hurricane season is a little bit above normal in regards to the forecasted amount of hurricanes but is still less than the past two years.

“It feels like it’s been a slow year, but actually, statistically, it’s been very normal across the Atlantic as a whole,” Miller said.

The National Hurricane Center has highlighted a seventh storm on the horizon. Tropical Storm Gabrielle has the potential to impact the Southeast in a little over a week. Miller said the medium term weather forecast of about two weeks suggests a few other storms as well.

When producing a forecast of an upcoming hurricane season, Miller said meteorologists are looking at sea surface temperatures and wind associated with El Niño climate patterns. If the year is in a La Niña phase, that favors more storms. If it is in an El Niño

phase, it favors fewer storms. The warmer the Atlantic Ocean is, the more likely there will be an increased amount of storms as well as stronger storms.

“This year our sea surfaces are warm but not eye-popping,” Miller said. “El Niño is not putting its thumb on the scale one way or another.”

Miller said it only takes one storm to cause destruction and it isn’t always a Category 5 hurricane. This is especially true for Louisiana where the forecast is for tropical storms with weaker winds but 8 inches of rainfall.

“If you live in Louisiana, whenever there’s any sort of tropical system in the area, you just need to be really attuned to your local weather forecast and don’t get fixated on if it’s a Category 5 versus a Category 1,” Miller said.

Matthew Rosencrans is on the lead seasonal forecasting team at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association and works at the National Centers for Environmental Prediction. He said the biggest threat to Baton Rouge during hurricane season is flooding. Even though the city hasn’t had a hurricane yet this season, he reminds residents there are two and half months to go.

NOAA predicted an above normal hurricane season with a range of 13 to 18 storms. The National Hurricane Center estimates there is an 80% chance of a storm forming in the next week, but it is currently deep in the

Fraternity investigated for alleged hazing

LSU is investigating an alleged criminal hazing incident that took place at an on-campus fraternity house during rush week.

The alleged criminal hazing occurred on Aug. 21 at the Kappa Sigma fraternity house. LSUPD began its investigation the next day.

“This is an ongoing investigation,” a university spokesperson told the Reveille Thursday.

In 2021, the university found the Kappa Sigma fraternity responsible for endangerment, coercive behavior, failure to comply and alcohol violations after a student needed an “alcohol medical transport” from a party. The fraternity was also placed on interim suspension at the time for holding a large party that violated pandemic restrictions.

The fraternity was also initially

charged with hazing that year, but was not found responsible for those charges. It remained on campus after reaching a settlement with the university and faced a deferred suspension until 2022 and a disciplinary probation until 2023.

tropics. Rosencrans said that bigger storms usually form there and that the longer range outlooks that are around three weeks maintain a 20% to 50% chance of another storm.

It is impossible to know this far out if any of these storms will hit Baton Rouge, Rosencrans said.

“I always want to talk about the science behind the outlook, but how do people respond to that science? Information is just as important,” Rosencrans said.

That information includes

evacuation plans, safety protocols for sheltering in place and making sure to have necessary supplies when a storm hits.

Miller said beyond the basics such as canned food and throwing away perishables, there are three things people usually don’t think of when preparing for a storm.

The first is to make sure to refill any prescription taken on a daily basis in case you cannot reach a pharmacy. The second is cash. If a hurricane knocks the power out for two weeks, credit card

machines will not be able to connect to the internet, meaning card transactions cannot be completed. The third is gas. Gas pumps will not work if there is no electricity, so Miller suggests filling up before evacuating or taking shelter.

“LSU is probably one of the most experienced universities in the country, dare I say the world, at preparing, adapting and managing around storms,” Miller said.

Rosencrans had a similar idea and said that if you see a storm that is a potential threat, start reviewing your plans. He said to make sure you know where you are evacuating to, familiarize yourself with university storm procedures and know how much food, water and other essential items you will need.

As Rosencrans said, Baton Rouge is most at risk for flooding. He says to stay out of the areas that get heavy flooding during thunderstorms because flooding only gets worse during a hurricane. He also advised getting a NOAA weather radio to continue getting information, even if a cell phone tower is out.

“I want someone to take that information and stay safe,” Rosencrans said. “How are you going to stay safe? Planning and responding, that’s the key.”

Residents can see upcoming forecasts by following the weather service office in Baton Rouge. NOAA also has an up to date summary of this year’s Atlantic Hurricane Season.

LSU Board of Supervisors names largest ever Boyd Professor cohort

The LSU Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to designate six LSU faculty members as Boyd Professors on Friday. This is the highest and most distinguished honor for professors to be awarded by LSU. This cohort of six professors is the largest ever in history.

The professors hail from LSU A&M, LSU Shreveport and Pennington Biomedical Research Center. It is the first time any professor from the Shreveport campus has been awarded this honor. It is also the first time a Manship School professor was awarded the honor.

The Boyd Professorship is named in honor of brothers Thomas and David Boyd, former LSU presidents and faculty mem-

bers. Professors with this honor exemplify national and international recognition for outstanding achievement in their respective fields.

Before today’s cohort, only 79 faculty members from all of LSU’s campuses have been awarded this honor.

“These scholars are advancing knowledge in ways that reach far beyond our campuses, and their work is helping to define LSU’s place on the national and global stage,” Interim President Matt Lee said. “This achievement is a powerful reminder of our commitment to advancing scholarship and shaping the future through research, education and service.”

These are the newest Boyd Professors: Mette Gaarde, Les and Dot Broussard Alumni professor, De -

partment of Physics and Astronomy, College of Science, LSU A&M

John Maxwell Hamilton, Hopkins P. Breazeale LSU Foundation Professor, Manship School of Mass Communication, LSU A&M

Steven Heymsfield , professor of metabolism and body composition, Pennington Biomedical Research Center

Michael Khonsari, Dow Chemical Endowed Chair and Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering, LSU A&M

Alexander Mikaberidze, professor of history, Ruth Herring Noel Endowed Chair, College of Arts & Sciences, LSU Shreveport

R. Kelley Pace, professor, Department of Finance, E. J. Ourso College of Business, LSU A&M

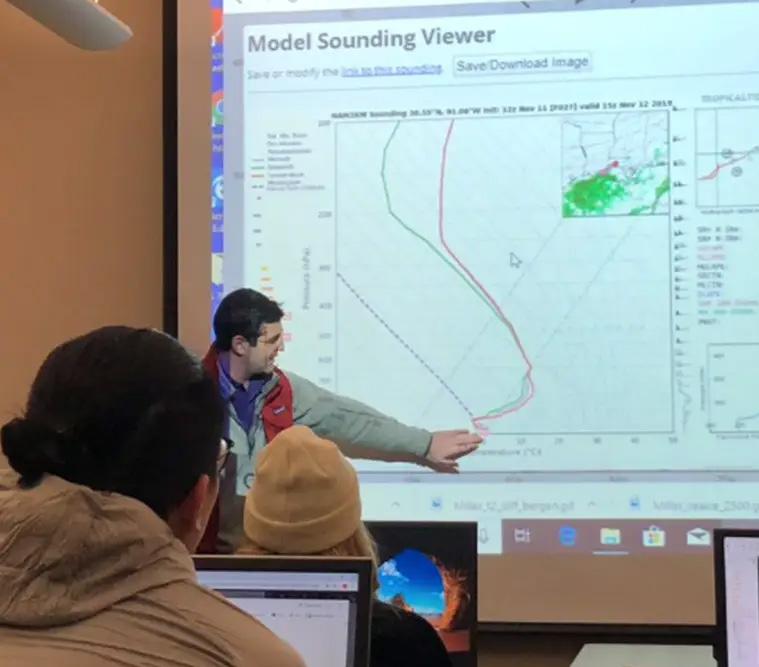

COURTESY OF PAUL MILLER

Paul Miller, a coastal and meteorology professor at LSU, shows a graph while teaching students.

FRANCIS DINH / The Reveille

The Kappa Sigma fraternity house sits Oct. 9, 2022 on Fraternity Lane.

KATRINA’S AFTERMATH

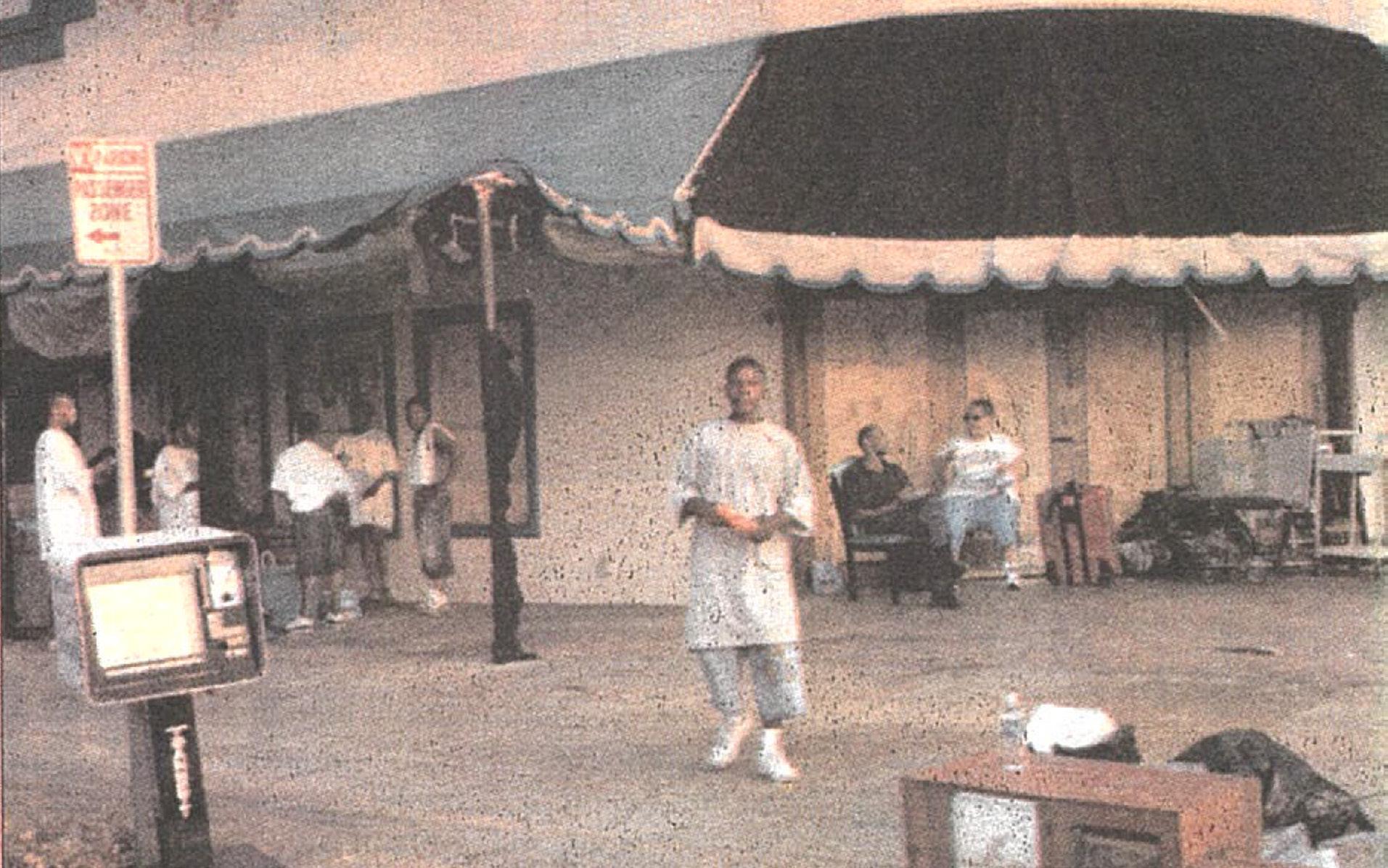

Photos taken by The Reveille staff in the days following Hurricane Katrina.

It was like 9/11 in slow motion. “

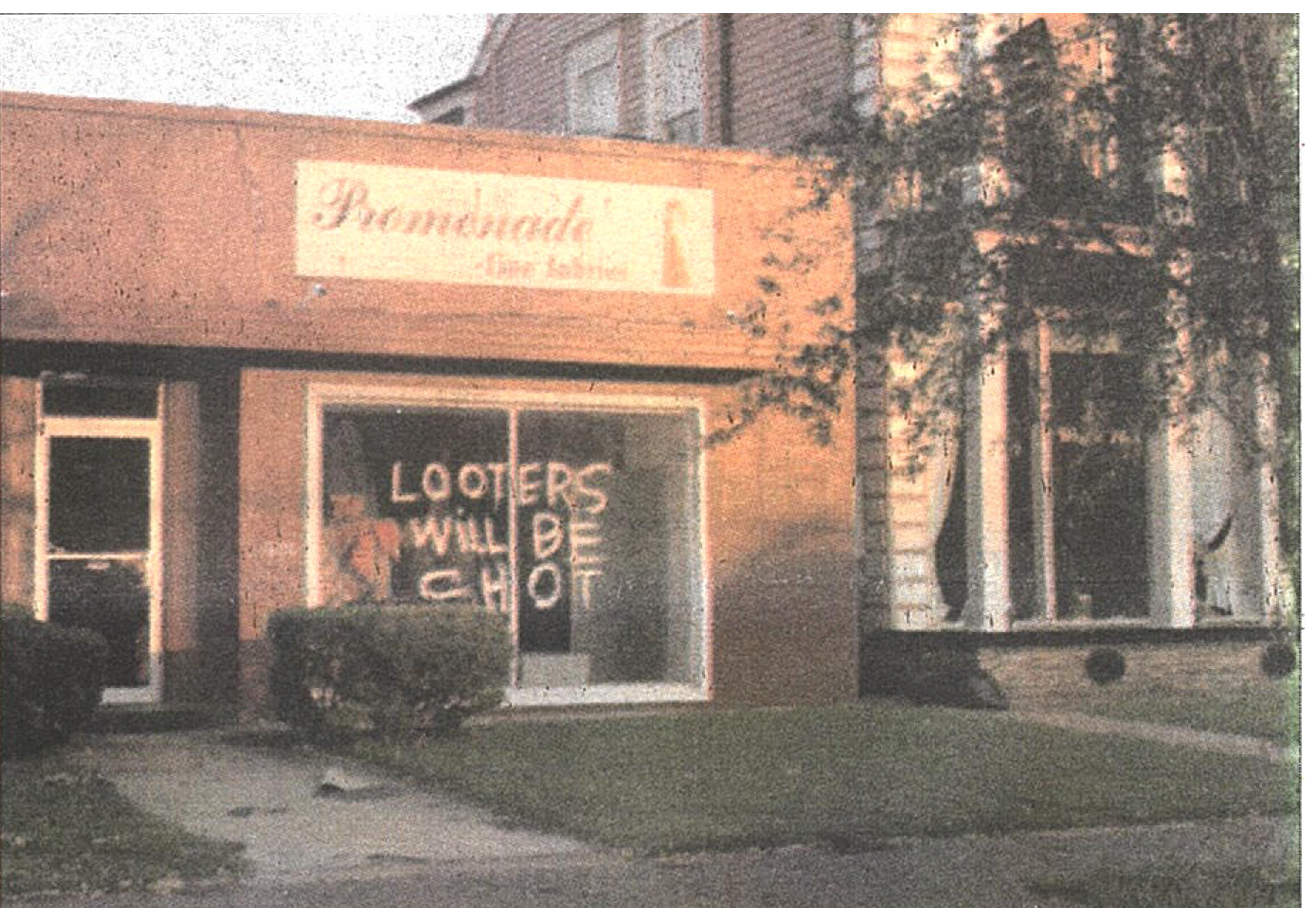

Left: Although reports of looting were rampant in the days following Hurricane Katrina, one Uptown show owner sent a more direct message in an attempt to deter break-ins.

Above: New Orlean’s residents sit outside a boarded-up Copeland’s Restaurant on the corner of Napoleon and St. Charles on Sept. 4, 2005.

Below: A construction crew works to plug the more than 500 foot-wide hole in the 17th Street Canal in New Orleans.

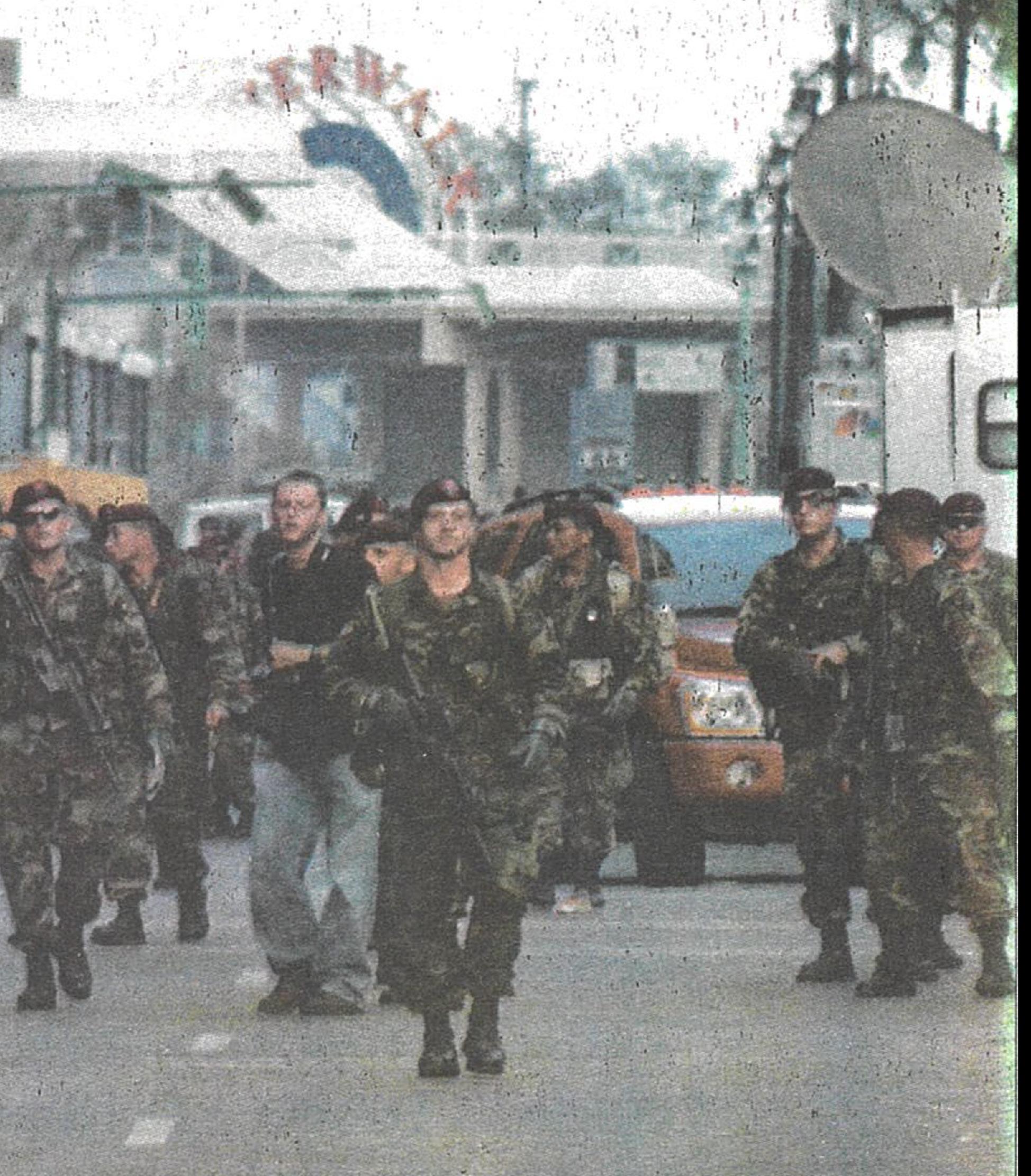

Above: Soldiers from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division march down Canal Street at sundown on Sept. 4, 2005.

Below: Student volunteers play with the child of an evacuee in the PMAC on Sept. 3, 2005.

Above: Dr. Ron Coe questions an elderly evacuee in the PMAC on Aug. 31, 2005.

Above: Light covers and trash litter the standing water on Canal Street in New Orleans.

Sean O’Keefe, former LSU Chancellor

Design by Riley White | Photos by Jim Zietz, Jolie Duhon & Michael Beagle

PMAC, from page 4

Originally set up as a 41-bed special needs shelter, the Fieldhouse is now holding more than 400 patients and is equipped with a pharmacy, psychiatric ward and pediatric center.

“This is the largest facility of its kind,” said Student Government President Michelle Gieg. “This is one of the biggest things LSU has done in this hurricane effort.”

University officials said it is uncertain how long the facilities will contain patients because of the variety of different cases.

Both centers are treating medical needs, feeding the hungry and helping stranded and lost evacuees reunite with family, but not without complications.

With so many state and federal organizations at work, many question who is in charge.

Robert Alvey, temporary media coordinator for campus emergency facilities, said the effort is “absolutely a mishmash.”

ATHLETES

, from page 4

Davis and Green are just a few of the players feeling more than the loss of a cancelled football game.

“I think there’s close to 30 guys on the team from that area,” said senior tackle Andrew Whitworth. “It’s definitely been tough for us to be around them and figure out what to say, how to approach them. Can you really say anything in that situation when you’re not feeling their pain?”

It hit home even harder when the team visited evacuees at the PMAC and River Center on Tuesday.

“I saw a guy I played football with eight or nine years ago,” Davis said. “I met up with him and his girlfriend. She was pregnant. I took them to a teammate’s apartment and got them showered up and talked to them

ACADEMICS, from page 4

I don’t belong here. We get these stares, these pity smiles. I feel as though we’ve been dealt a shitty hand, so we just have to play it.”

Katrina’s effects are widespread, Lefeaux said, because for new students, it’s the thought of losing their belongings or schools and for others their homes or enjoyment during their free time.

“Some students don’t know what they have lost, so there’s uncertainty.” Lefeaux said. “For some students the population in their dorms has increased tenfold over night.”

“All of a sudden, they’re distracted. They’re not getting a lot of sleep. Maybe its the people across the hall whose family has moved in, or for those off campus, it’s taking even more time with the increased traffic.”

Lefeaux said the Mental Health and Wellness staff will continue the special services in the Union throughout the week. They expect to see an increase

Initial management of both facilities came from the State Department of Social Services, with the state Department of Health and Hospitals providing the necessary medical equipment and manpower.

Chancellor O’Keefe established an Operations Center on Sunday to become the single point of contact for organizing resources and communications.

Although the number of patients is constantly changing, the PMAC floor plan was modified six times during the past week to ensure a more organized emergency procedure.

“There’s a lot of people on call,” said Leslie Pecora, registered nurse and PMAC relief worker, on Sunday. “There’s a lot of EMS personnel working with officials to get the patients out. They’re stabilizing them and getting them to other shelters.”

Patients are assigned different colors depending on the severity of their conditions.

“Once a patient is stable,

for about an hour.”

Other athletes pitched in at the PMAC when and where they could. LSU basketball player Glen Davis spent Tuesday night volunteering at the triage center. Davis helped wheel patients around the floor of his home arena. Nearby members of the coaching staff unloaded trucks filled with medical supplies and food. Members of the the soccer team helped fill out patients’ forms.

The football team circulated among the crowd of displaced New Orleans residents signing autographs and handing out tshirts and posters.

“[We were] there to give them something else to talk about, get their minds off of it, said Whitworth. “We want to do whatever we can.”

Defensive tackle Kyle Williams said he and some team-

in students next week who are looking for a forum to talk or vent, after they’ve learned their way around the campus.

Neil Mathews, vice chancellor for Student Life and Academic Services, said the extended services at the Union and the residence halls can serve as a way for students to learn how to focus on classes amid all the distractions. Mathews said Drayton Vincent, director of Mental Services, has been on duty since the storm hit.

“They’re an outstanding group of professionals who’ve been handling the services well,” Mathews said.

For now, Lefeaux said, all students can do is try to get life back to normal as best as they can, starting with simple routines like sleeping, eating and exercising.

“We all had memories that are now nothing but memories,” Lefeaux said. “The way we make a statement ... the way we pick up our mental health, is to continue with our lives.

we try to place them in a shelter,” said Apryl Keaty, registered nurse with the New Mexico Disaster Assistance Team. There were two intensive care patients in the PMAC on Monday morning, along with 22 intermediate acute care patients.

Alvey confirmed that an unknown number of patients on campus have died. The Federal Emergency Management Agency is then responsible for the bodies. A refrigerated trailer was provided at the PMAC for such cases.

Disaster medical assistance teams have come from all over the nation.

Evacuees were sent to a wide variety of shelters, ranging from the Port Allen Community Center to the Houston Astrodome.

The immense student volunteer effort began Monday evening with about 20 volunteers — most of them from the Baptist Collegiate Ministry.

“We ask for the opportunity to show your love this evening,

mates borrowed an 18-foot covered trailer from trainer Jack Marucci on Tuesday.

Within 24 hours it they had filled it with clothes, blankets, food and toys. On Monday, Williams, Whitworth and junior running back Justin Vincent dropped off the trailer at St. James Episcopal Church at Convention and North Fourth streets.

Julie Krutz, a volunteer with St. James, said the items will be sorted and taken to evacuees at the River Center and other shelters. Krutz said volunteers are still taking donations and need men’s toiletries.

Williams said the team will continue to collect and distribute items for hurricane victims.

“It’s not a problem that’s going to go away in a week or two,” Williams said. “It’s going to be months.”

Father,” said Michelle Gros, volunteer and 2003 University graduate, as they gathered in a circle of prayer and held hands.

The number of student volunteers grew rapidly throughout the week.

Student volunteer Monique Ducote, human ecology junior, handed out food and water Thursday to evacuees outside the PMAC.

“We sat down all day [Wednesday] and watched [the news],” Ducote said. “We found out about this and signed up. We’re doing whatever we can — feeding people and keeping them occupied.”

As the need arose, health care professionals showed certain non-medical volunteers how to perform tasks such as cleaning patients, helping them use the restroom, taking their body temperatures and bathing smaller children.

Levi Wright, Jr., graduate student and non-medical volunteer, said volunteers have taken “ini-

DORMS, from page 4

roommate’s mom is from Baton Rouge, but she and her dog stayed with us a few nights when her power went out.”

Residential life has been allowing families to stay, but they are trying to cut down on pets in the dorms and on-campus apartments.

According to a recent Department of Residential Life broadcast e-mail, pets staying in on-campus residences were supposed to be removed by Sept. 1 at 5 p.m.

The University recommended moving pets to a temporary kennel at John Parker Coliseum to assist the hurricane victims as much as possible.

Friends of residents are also staying in the dorms.

“I am housing my dad and my friend from UNO,” said Megan Hussey, biochemistry junior and Metairie native. “They both came

tiative leadership.”

“I just had to get clean underwear for a guy with diarrhea,” Wright said. “In this particular situation, you just have to get into it.”

Evacuee Moyna Patterson, 65, of New Sarpy, La., arrived at the Fieldhouse the Sunday evening before the hurricane struck. She looked after her legally blind husband while trying to get in touch with her step-daughter.

“He cannot do anything by himself,” Patterson said. “My husband is the only thing I care about. Material things you can get back, but my husband’s life is more important.”

Trenice McBride, 32, hitchhiked Tuesday morning in the back of a truck with her three small children from the Omni Royal Orleans Hotel in New Orleans to Baton Rouge. She said they were certain their house was underwater.

McBride, sitting outside the PMAC with her children, said, “It’s been hell. It’s hot.”

on Thursday. It’s been weird having everyone in the room because I actually went to Louisiana School for Math, Science and Arts, so I haven’t lived at home since I was 15.”

The University offered other options for temporary housing this past week, inviting families staying on campus to stay in homes of University faculty and staff members. At 9 a.m. in the Pentagon Service Building, families of students seeking housing can speak with volunteers who are trying to accommodate those who have been displaced.

Residential Life also helped refugee families relieve stress by throwing together a last-minute event, Family Day. Residential assistants and ambassadors set up a spacewalk for children, a free meal and massages for the families. The event was held in Acadian Hall and on the field next to it.

ANSON TRAHAN / The Reveille

Trucks and cars toting parents of LSU students and their possessions line Burbank Drive just blocks away from campus.

When Hurricane Ivan hit in 2004, contraflow was used for the first time. The plan was run largely by the state police, with cones and crossovers and stops that created bottlenecks.

“Their contraflow plan didn’t really work very well, and a lot of the public was not happy,” Wolshon said. “So they put together this task force and said, ‘Let’s get this guy at LSU who studies this stuff, and then let’s get the police and the DOTD together and see what they can do.’”

For the first time, the LSU researchers were working alongside state agencies.

“To their credit, especially the state police, they listened,” Wolshon said. “If we said, ‘I think it’d be good if you did this,’ they’re like, ‘That’s a great idea. We never thought of that.’”

The plan they created was finished only two weeks before Katrina struck.

“I didn’t know how well it worked, or if it worked, but all you saw on the news was the flooding and the deaths,” Wolshon said. “But after things settled down, we started getting all the data, all the counts of how many cars went by these locations, and it was clear they had moved twice as much traffic as they did during Hurricane Ivan. They had effectively doubled the outbound rate of flow.”

The university’s role in contraflow brought international attention. Wolshon said he and his students began working with agencies in China, Australia, Europe and across the U.S.

“LSU is really looked at as probably the world leader and expert in this topic,” he said. “I’m so proud of all of our kids and the work we’ve done here.”

Looking back, Wolshon said the project didn’t begin with a clear problem to solve but with curiosity.

“We never knew that any of this would amount to anything. We just did it because we were interested in the topic. It wasn’t a solution to a problem. It was a solution in search of a problem.”

Two decades after Katrina, he continues to study evacuation planning as storms become harder to predict.

“We’ve seen numerous examples of rapid intensification,” Wolshon said. “So what I think is important is that we have plans. A failure to plan is planning for failure.”

Wolshon said the challenge now is ensuring those plans reach beyond highways. While contraflow remains central to Louisiana’s strategy, he noted that not everyone has the means to evacuate by car. Future preparedness, he argued, must include options for people with limited mobility and clear communication to the public.

“People will make rational, intelligent decisions if you give them good information,” he said. “The key is making sure they have that information before the storm arrives.” TRAFFIC, from page 3

JOURNALISTS

, from page 2

They recall it vividly — an old woman, wheelchair-bound. Two student medical volunteers flank her. Her orange shirt. The blue gloves.

“That photo still breaks my heart,” said Trahan, who took the image. “She was suffering. I mean, you can see that suffering on her face, physically.”

Trahan said much thought and respect went into his photography during Katrina’s aftermath. He didn’t want to be like paparazzi, so he kept a respectful distance. He used a wide lens, so he didn’t distort dimensions — he didn’t want to alter the stark reality in any way. He went up to his subjects afterwards to thank them and ask their permission to use the picture.

Trahan’s photos won numerous awards, but he didn’t think of them as anything special. He was just documenting the moment.

“I don’t feel proud of those photos,” Trahan said, “because of the situation. It’s not something I would ever ask for.”

Just two days before school restarted, Sternberg and Associate Managing Editor Michael Beagle decided to go into New Orleans. The Reveille’s duty was to cover what happened at LSU, but Sternberg nonetheless felt compelled to venture into the city.

It was ground zero. How could he not?

“I felt like I had to,” Sternberg said. “It was the biggest story of my life.”

Sternberg and Beagle traveled through New Orleans and surrounding areas, speaking to drifting victims. The pair shared one camera and snapped photos. They’d later argue about who took which.

Sternberg stopped at his home in Metairie and stood on the 17th Street Canal that had breached and watched as a helicopter tried unsuccessfully to plug it with sandbags.

The two got into the city as the sun rose, and they left as it set.

The immediate culmination of The Reveille’s furious, bootson-the-ground reporting was the Sept. 6 Katrina special edition, its first post-Katrina paper. The coverage of Katrina, though, continued for weeks and months.

“I thought that was the most important thing that I was ever going to do,” Sternberg said.

‘I want to roll my sleeves up and help people’ Katrina was inseparably personal for many Reveille journalists.

Then-Assistant News Editor Jennifer Mayeux’s New Orleans East home that she’d lived in her entire life was destroyed.

“It’s humbling to see all your family’s possessions written down on a single piece of paper,” she wrote in a column titled “Home No More” published on Sept. 6, 2005.

Roberts also called New Orleans home. She evacuated the city just days before the storm arrived, after most had already left. It was a strangely silent drive.

“That image of leaving the city is like my last goodbye to the New Orleans that I know,” Roberts said. “It was quiet, it was peaceful, and that’s how I want to hold on to pre-Katrina New Orleans.”

Then engaged, Roberts left behind the wedding dress she’d wear at her ceremony. The National Guard let her fiancé and a friend back into the city on a rescue mission to retrieve it; when they found it, it was just inches away from the rising water in her Upper Ninth Ward home. However, it wasn’t spared the smell of sewage, Roberts said, and had to be hosed down.

Needless to say, Katrina literally hit home.

An ethical foundation of journalism is that reporters refrain from personal involvement in a story. That seemed a nearly impossible task during Katrina, when journalists themselves and the people they were close to were suffering too.

Could journalists help those in need? It was a question Sternberg had to decide for The Reveille.

Many around him felt strongly about it, particularly Causey, his managing editor.

“I want to roll my sleeves up and help people rather than just following them around and writing down what they say,” wrote Causey in a Sept. 8 column that wrestled with that very question.

It was a question Sternberg could later pose to media ethics classes he taught and receive widely contrary answers.

“Ultimately, the answer was yes,” Sternberg said. “I couldn’t live with myself.”

Many Reveille employees volunteered at the PMAC and in other relief efforts. The Reveille website instituted a database that connected students to volunteer opportunities, something for which Sternberg said university Chancellor Sean O’Keefe came down and personally shook his hand.

For two months, Roberts said she consistently hosted between six and 10 evacuees in her onebedroom apartment, including, at

one point, a Seventh Ward family of five.

“I don’t think that any journalist at that time… had any confusion about what was morally needed in doing their work,” Roberts said.

Marissa DeCuir, then a sophomore staff writer, found herself helping the people she interviewed for stories.

“Not a story went by without somebody that I was interviewing asking me, ‘Can you get in touch with my family and let them know I’m okay?’” DeCuir said.

DeCuir would go home and look them up on Facebook, then just one year old. Many of her searches weren’t fruitful, but it was something she felt a duty to do. She couldn’t just report; she had to help.

Feeling and acting out a personal involvement in the story during Katrina wasn’t a weakness.

“We feel emotion, and that’s what makes us better reporters,” Gibson said.

Surely, that emotional investment elevated The Reveille’s coverage of Katrina, which garnered many awards and changed many lives, including the journalists themselves.

But it was draining.

The staff lived on sleeping bags and cots in their newsroom in the basement of Hodges Hall, stocked with granola bars and water bottles, doors open to let in cool air in lieu of a working A/C. Sternberg said he lived in his office until at least October.

Even for those who weren’t directly affected by Katrina, Sternberg said, it was “devastating to be in that proximity.”

‘We weren’t letting our minds take it in’

Years later, Gibson found herself sobbing in her car. She’d just finished a reporting assignment near Atlantic City at a shelter where people were waiting out a severe storm.

She couldn’t figure out why she was crying. Then it dawned on her: She’d never processed Katrina.

“We obviously knew the horror of what was happening,” DeCuir said. “We just weren’t letting our minds really take it in at the time. It was like we had to do our job.”

Discussing trauma in journalism is something that’s slowly becoming more accepted. While certainly not comparable to that experienced by the victims themselves, the effect on journalists who cover tragedy after tragedy is enormous.

In a career that’s taken him to editor positions at the Associated Press and the States Newsroom, Causey has covered or overseen coverage for many tragedies since Katrina, including California wildfires, Hurricane Harvey in Texas and the Uvalde school shooting. He’s learned from each experience, but Katrina set the foundation.

“Being able to talk to people who have been through something traumatic but do it in a caring way and a humane way is a huge takeaway that comes from my coverage of Katrina,” Causey said.

In the ensuing years, many of those Reveille reporters turned away from journalism, but all of them found that Katrina steered them in a definite direction. Some found a love for nonprofit work, others for telling people’s stories.

For Trahan, it kept him home. Always a “black sheep,” he was in his eighth year of college and had long pondered moving abroad after. However, Katrina “crystallized” his love for Louisiana.

These student reporters’ work, as was the case for most during Katrina, was borne out of personal connection to the community. They couldn’t let these disaster victims be overlooked, like they were by the nation and the government.

“It was all about witnessing what was happening to these folks, witnessing what was happening to us, right? As Louisianians. And then making sure that story got told,” Trahan said. “Because the biggest crime of that week, of that time, was being ignored.”

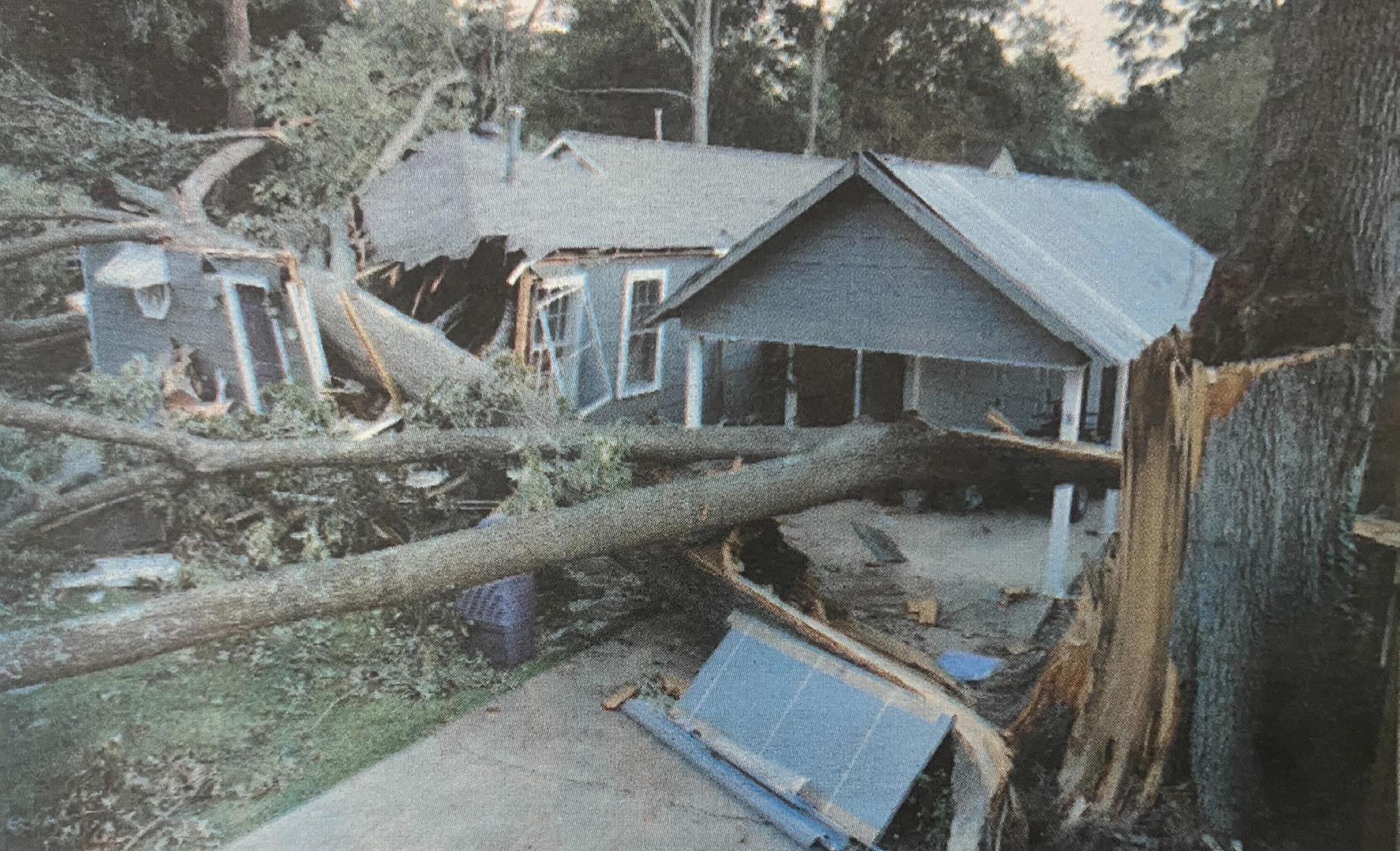

CHRIS PERKINS / The Reveille

A home in the Southdowns neighborhood is demolished by a fallen tree during Hurricane Katrina.

ENTERTAINMENT

MADI MAY’S

MENU

The Dairy Store is another sweet reason to love LSU

BY MADISON MARTIN Staff Writer

As you walk the streets of campus, you see students walk in a building empty-handed and leave with an ice cream cone to delight in. What is this place? Paradise on a college campus? Close, but no — it’s called the Dairy Store.

The LSU Dairy Store has a plethora of unique flavors that highlight its Tiger pride, including “Bulldog Bite” in honor of the first LSU home game of the 2025 season.

TIGER BITE

The flavors also cater to the latest news students are keeping up with, like Taylor Swift’s recent engagement. But if you just want a regular ol’ treat, there is undoubtedly an ice cream cone with your name on it. My favorite part about the Dairy Store has to be that students are the ones serving you, which means they understand the horror it is to pick just one flavor. You can expect to sample dozens of their seasonal and fresh flavors with no judgment. But if you are really having a hard time making up your mind, here’s a cheat sheet.

Tastes like a blueberry muffin in liquid form. Freshly picked blueberries fill your mouth. The ice cream itself screams tiger pride with its gold and purple coloring. If Mike could eat ice cream, this would definitely be his favorite flavor.

COOKIE DOUGH

Almost as if homemade cookies were mixed into a light and airy vanilla base. Consistency is creamy with an indulgent flavor.

PUMPKIN SPICE

This seasonal flavor never goes out of style. A potent taste of pumpkin spice, as if a latte transformed into a frozen treat just for you.

WEDDING CAKE (TAYLOR’S VERSION)

Classic almond flavor with a hint of coconut and mini cake pieces through out. Genius play on words with the name.

KEY LIME PIE

Indistinguishable from the pie and had the perfect amount of citrus. Pieces of pie crust come with each bite.

The shop also frequently hosts events with local Baton Rouge businesses. One frequent partner is Companion Animal Alliance for the Pups n’ Cups adoption event. Ice cream is still for purchase during this event, but if you adopt a pup, your scoop is on them. Students are encouraged to take a study break and head over to play with (and possibly bring home) a four-legged fella.

The LSU AgCenter Dairy Store is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday and closed on the weekends. You can find it on 118 South Campus Dr. next to Howe Russell and the Life Sciences building.

PAYTON PRICHARD / The Reveille

LSU Dairy Store sign sits May 2 in front of the LSU Dairy Store on South Campus Drive in Baton Rouge, La.

SPORTS ROOM FOR GROWTH

LSU underperforms in home opener against LA Tech, wins 23-7

BY AINSLEY FLOOD Deputy Sports Editor

Despite offensive setbacks, LSU football emerged victorious in its first game at Tiger Stadium against in-state opponent Louisiana Tech.

Head coach Brian Kelly and the Tigers earned a statement 1710 win over Clemson in Week 1, breaking the season opener curse that’s haunted the program for five straight seasons.

On Saturday night, LSU moved to 2-0 after a 23-7 win over the Bulldogs, but the Tigers’ performance wasn’t up to par with what they delivered last week.

“We didn’t coach well enough, and we didn’t play well enough tonight, and that’s not our standard,” Kelly said in a post-game press conference.

LSU had an early scare on the first play when starting center Braelin Moore went down and was escorted off the field.

An early first down showed promise, but fifth-year-senior quarterback Garrett Nussmeier’s pass to Aaron Anderson was intercepted by New Orleans native Michael Richard for the turnover.

The next time LSU’s offense took the field, it made it to the 13yard line but couldn’t convert on

FOOTBALL

the third down. Damian Ramos took the 51-yard field goal attempt, which fell just short.

Game 2 captain Zavion Thomas, a senior wide receiver out of Woodmere, Louisiana, was one key player for LSU in tonight’s matchup.

In the first quarter, he made a 15-yard catch at the 35 for a first down, and he later rushed 48 yards on a carry all the way to the 12yard line.

On the third down with five yards to go, LSU got the go-ahead score when Nussmeier found receiver Nic Anderson in the center of the endzone. Anderson caught the pass, and Ramos made the kick for the Tigers to go 7-0 on the final play of the first quarter.

On its first possession of the second, LSU got all the way to the six, but two incomplete passes led to a 23-yard field goal attempt made by Ramos.

With an offense still struggling to find its footing, LSU’s defense stepped up once again.

Last week, LSU surrendered only 261 yards to Clemson. Against LA Tech, it was only 154 total.

LSU made 61 tackles and had two sacks on the night. Unable to make progress, the Bulldogs’ offense punted nine times compared to LSU’s three.

At halftime, LSU led 10-0 after an almost perfect half for the defense, but missed opportunities by the offense and coordinator Joe Sloan meant missed points for the Tigers.

“You’ve got to run the football,” Kelly said. “We didn’t run the football effectively tonight.”

When they returned for the second half, Aaron Anderson made big catches, two over 20 yards in the third quarter, and Barion

Brown led the team with 94 receiving yards and a completion rate of 80%.

More defensive heroics saved LSU from a tight game, highlighted by a third down sack from linebacker West Weeks, who led the defense in tackles with 10.

On the next drive, LSU put itself within three yards of the endzone, and running back Caden Durham converted the third down on a carry.

The offense wrapped up the third quarter with a first down, but lost tight end Trey’Dez Green after he went down on the first drive of the fourth quarter.

Nussmeier and the offense only struggled more from there. The quarterback was sacked on a third down, which saw Ramos kick a 46yard field goal.

LSU’s defense eventually slipped, allowing LA Tech’s quarterback Blake Baker to throw a 33-yard pass into the endzone with four minutes left in the game.

The Tigers got back within striking distance of the Bulldogs, but failed to convert the third down with just two yards remaining. Ramos kicked for three and advanced the team to a 23-7 lead – the final score.

Nussmeier went 26-41 on pass attempts, including one touchdown, and was sacked three times with 27 yards lost.

This result, although a win, is a visual representation of what needs to improve if LSU wants to go all the way this season.

“You always have to measure this by the outcome,” Kelly said. “In this instance, it’s what we wanted. It’s certainly not the way we wanted to get there, so we’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Three takeaways from LSU’s underwhelming win over LA Tech

BY CHLOE RICHMOND Sports Editor

LSU football returned for its home opener against Louisiana Tech after securing a Week 1 win over Clemson, the program’s first season-opening success in five years.

The question heading into this game wasn’t whether LSU could win, but rather, could LSU win without playing down to its competition’s level? Well, the 23-7 finish says more about LSU’s weaknesses than it does its strengths, which isn’t what you want if you’re head coach Brian Kelly.

“We’re happy with the win, we’re not happy with the production across the board,” Kelly said. “We didn’t coach well enough. We got outcoached in a lot of areas.”

Here are three takeaways from LSU’s low-scoring win over LA Tech.

Offensive worry grows after many injuries

LSU is a team that’s been rather lacking on the defensive side of the ball in recent years, but this season, worry has shifted to the other side.

After LSU saw four of its five starters get picked in the 2025 NFL

Draft, eyes widened with concern over the thought of its offensive line future.

With the way LSU performed against LA Tech, the concerns on offense continue to rise, and this will only continue now that Braelin Moore is out with a sprained ankle and Trey’Dez Green is on crutches.

Moore went down after the first snap and later appeared on the sideline with a boot. DJ Chester filled in for Moore, and Kelly expects his team to play just as well with an experienced guy like Chester out there. The scoreboard reads a win, but the offensive line currently has too many holes for success in the long run.

Last season, LSU led the SEC in sacks allowed, finishing the season with only 15. We’re just two games into this season and LSU has already seen Garrett Nussmeier sacked four times — three of which occurred during the in-state showdown.

“We weren’t good enough tonight in our schemes and executing the schemes that we needed to,” Kelly said. Receivers look strong, but run game still weak

The highlight of LSU’s offense

is without a doubt the receiving corps, which saw positive plays from multiple players.

Barion Brown stepped up as LSU’s best receiving option on the night and earned the game ball after finishing with 94 receiving yards off eight catches. He “balled out,” as Kelly said in the press conference, but the head coach also expressed great disappointment in LSU’s run game.

“You got to run the football,” Kelly said. “We didn’t run the football effectively tonight.”

What the offense lacked against LA Tech was production out of usual go-to Caden Durham, who led the run game for LSU last year as a freshman.

Nussmeier handed the ball off to Durham 13 times, which is more than double the number of times he went for the next option, yet Durham only rushed for 29 yards to average 2.2 per carry.

That mixed with his 10 receiving yards is more than just below average. It’s uncharacteristic.

The weak offensive line doesn’t help Durham, either. It struggled to open up rushing lanes for him, making LSU’s one-dimensional offense too predictable for LA Tech’s defensive front seven.

Luckily, the Tigers were able to stay alive on offense thanks to Brown and other contributions from Zavion Thomas, Nic Anderson and Aaron Anderson.

Nussmeier isn’t playing like a veteran

Playing against a Group of Five team is usually a piece of cake for a team like LSU, especially when it’s led by such a seasoned quarterback like Nussmeier. That’s the expectation, at least.

LSU’s low-scoring performance against Clemson was expected, especially considering Clemson’s returning defensive talent. LSU’s 23-7 finish against LA Tech was unexpected, though, especially with most of the Tigers’ points coming off of field goals.

Nussmeier going 26 for 41 on pass attempts is already below expectation, but only throwing one touchdown isn’t what fans want out of a veteran quarterback. He has years of training, most of which happened with a Heisman winner ahead of him, and a full season of SEC play under his belt.

But compared to last season, Nussmeier’s decision-making skills have skyrocketed. The three sacks aren’t a good look for LSU, but LA Tech easily could’ve had more if

it wasn’t for some of Nussmeier’s quick thinking that led him to find someone and get rid of the ball.

Overall, Kelly and his team know they “didn’t live up to standard,” but there’s no time to waste as the Tigers prepare to face a Florida team hungry to bounce back after a disappointing loss to USF.

“After what happened this past weekend, they’re going to play their absolute best football,” Kelly said.

LUKE RAY / The Reveille

LSU football players Whit and West Weeks hype up the crowd during a play against Louisiana Tech Sept. 6 at Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, La.

LUKE RAY / The Reveille LSU football redshirt junior wide receiver Nic Anderson (4) celebrates a touchdown on Sept. 6 at Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, La.

When someone you

care about is thinking of suicide, you can help

GUEST COLUMN

MAX STIVERS

I was 16 years old and up late on a weeknight when Facebook pinged with a message from a school friend. Honestly, calling her a friend is probably unfair: we had been friends in freshman year before drifting apart — nobody’s fault, it just happened. In any case, we were still close enough for her to say goodbye to me that night before carrying out a plan to kill herself.

My friend’s story is heartbreakingly common: roughly 1 in every 5 young adults have had serious thoughts of suicide, and the suicide rate among 10-24 year olds has doubled since 2000. Many of these individuals will never tell anyone they’ve had thoughts of suicide: maybe because they’re worried people will judge them, maybe because they don’t want to burden anyone else with their problems or maybe for other reasons entirely. Even more will never seek help from a doctor or mental health professional because they don’t trust that these resources will be helpful or because treatment options around them aren’t affordable and accessible.

I traded messages with my friend for hours, telling myself that if I could keep her talking, I could stop her from ending her life. It never occurred to me to ask for help — I wouldn’t have known who to ask. When I woke up the next morning with my laptop overturned on the floor next to my bed, I was convinced that I’d failed her, and was completely inconsolable until I walked into the band room before third period and saw her sitting with the clarinets. Guilt gave way to relief, but the terror I felt when someone I cared about was in a life-or-death situation and I had no idea how to help has been harder to forget.

That terror drove me to spend half of my life in universities learning to better meet the needs of people experiencing suicidal thoughts and to empower their loved ones and their communities to do the same. In the process, I’ve learned that suicide is a public health crisis with no easy answer, despite incredible progress made through the dedicated work of clinicians,

EDITORIAL BOARD

researchers and public health advocates: There are no magic words that you can tell someone who’s thinking of suicide to keep them safe and make everything okay. More importantly, not everyone has the resources or the inclination to devote their lives to learning everything they can about suicide prevention, and we shouldn’t need to in order to support people we care about when they’re at risk.

This Wednesday, Sept. 10, is World Suicide Prevention Day, and the American Association of Suicidology marks the entire week surrounding it each year as National Suicide Prevention Week. This week, and every week, it’s important to remember that we don’t need to be experts to help our loved ones keep themselves safe — you can make a difference just by showing you care. If a person who’s thinking about suicide is lucky enough to have someone like you in their life to support them and is brave enough to ask for your help, though, here are some techniques to keep in mind:

Know your role

People experiencing thoughts of suicide often struggle with overwhelming negative emotions that they may have difficulty expressing to someone else. You can help by responding to their distress with calm and to their fear of rejection with warmth. Making it easier for them to tell you what’s on their mind is more important than trying to figure out the right thing to say (or avoid saying the wrong thing) to them.

Don’t focus so intensely on trying to save them or fix things that you forget to leave space for the person who needs help. Instead, encourage them to tell you about what they’re feeling, listen patiently to what they share and provide support without judging them or trying to problem-solve.

Be open

(even if it’s uncomfortable)

Because suicide is so often stigmatized and avoided, asking someone if they are having thoughts of killing themselves (or even just saying the word “suicide” out loud) may feel like overstepping or like you could risk putting thoughts of suicide into their mind. However, research has shown that talking about suicide openly can actually reduce the severity of a person’s distress or help them to feel more in control.

Ask them directly if they’re thinking about suicide. If they are, ask them what has been making them feel this way, and continue to listen.

Help them seek help

When a person is having thoughts of suicide, help them limit their access to drugs, firearms or other objects that they could use to kill themselves. If they don’t feel confident in their ability to keep themselves safe, you can connect them with the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988. If urgent medical attention is needed, take them to your local emergency department or call 911.

After the person is feeling more like themselves, resources available on campus, in your community or online can also help them manage their experiences of suicidal thoughts when you aren’t available.

Take care of yourself, too

Even for those of us who have chosen to do it for a living, helping someone navigate a suicidal crisis can be scary and exhausting. When such a difficult conversation is over and you’re sure of everyone’s safety, find your own healthy ways of coping and recovering, like doing something you enjoy or leaning on your loved ones for support. 988 also provides support for people who have helped someone else in crisis.

When a person you care about tells you they’re thinking of suicide, feeling confident you know how to respond makes it significantly easier to respond effectively. Remember it’s not your responsibility to save their life, but know that you can help them save themselves.

For more information about resources available to people experiencing suicidal thoughts and/or behavior, scan the QR code below.

Your relationship should not be your identity

BODACIOUS BLAIR

BLAIR BERNARD Columnist

Growing up, I noticed a lot of unhealthy relationship norms in my hometown. I knew from early on that I wouldn’t be focused on settling down as soon as high school ended, like others around me had. Other people dated for the majority of their school careers and ended up with tarnished reputations for their early adulthood.

Once I moved to Baton Rouge, I quickly realized that wasn’t the case for many people here. Every student I met here was also in pursuit of their individuality, focused mainly on college and making friends with like-minded people. It was clear I was finally operating on the same schedule as my peers.

However, as time went on, I experienced my friends go through major heartbreaks and relationships and now the majority of my close circle has chosen to get married. It all happened faster than I could’ve imagined. In my perspective, it seemed like while I’m trying to tread through my early twenties and solidify my individuality. My friends found that settling down was their next plan of action.

Now, I think long-term committed relationships are a part of the human experience. I really do believe it’s so beautiful to witness people meet one another at a pivotal point in their young life and inherently grow together. But, I think it’s important to remember that some rela-

tionships are only for a season.

The only constant you can count on in your life is you. I’ve always been independent. I was raised by an independent mother and that heavily impacted my views on potential codependency and/or codependent habits in relationships. In a perfect world, you could balance being in relationships and also capitalizing on the person you’re trying to become.

But, this isn’t a perfect world and unfortunately, romantic relationships take self-sacrifice; your time, your tears, your blood, your patience and vital years that we could be using to nurture our own habits and passions instead of pouring that into a futile relationship.

We’ve all known a person who loses themselves in their relationships. Your life is expected to change in many ways when you make a commitment, sure. But, it doesn’t mean you have to. Don’t forget the commitments you made to others and yourself before falling in love with your partner. Signifiers like these reignite the reason I believe young relationships contribute to codependency not romance.

I’ve never been in a committed relationship, and I can say that it has suited me well. When you think of me, I want you to think of Blair Bernard, the unique, intelligent, glamorous, glowing, bodacious, gorgeous, independent woman, regardless of my relationship status.

Blair Bernard is a 21-year-old theatre major from Lafayette, La.

The Reveille (USPS 145-800) is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Communication. Signed opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, The Reveille or the university. Letters submitted for publication should be sent via e-mail to editor@lsu.edu or delivered to B-39 Hodges Hall. They must be 400 words or less. Letters must provide a contact phone number for verification purposes, which will not be printed. The Reveille reserves the right to edit letters and guest columns for space consideration while preserving the original intent. The Reveille also reserves the right to reject any letter without notification of the author. Writers must include their full names and phone numbers. The Reveille’s editor in chief, hired every semester by the LSU Student Media Board, has final authority on all editorial decisions.

“What don’t break us make us stronger... That’s how we built down there.”

Max Stivers is a clinical psychology doctoral student at LSU who is part of the Consortium to Advance Suicide Prevention.

CAILIN TRAN / The Reveille