JACKIE SPEIER: EXIT INTERVIEW

UFW’S TERESA

ROMERO ON FARM WORKERS

ECONOMIC FORECAST

GLORIA DUFFY ON PALM SPRINGS

REVEALING THE REAL GEORGE SHULTZ

UFW’S TERESA

ROMERO ON FARM WORKERS

ECONOMIC FORECAST

GLORIA DUFFY ON PALM SPRINGS

October 3-18, 2023

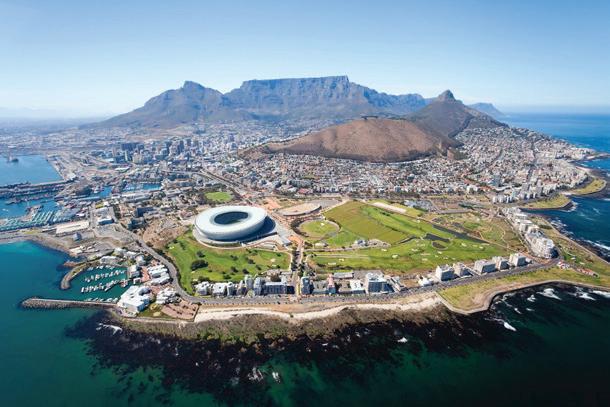

Marvel at the incredible wildlife and wonders of South Africa, Zimbabwe and Botswana. From colorful Cape Town to Victoria Falls, historic Soweto to Robben Island, every moment of this 12-night journey will inspire. Experience famous safari destinations: Chobe National Park, Hwange National Park and Kapama Private Game Reserve. Plus, enjoy three nights aboard the opulent Rovos Rail.

from $8,295, per person, based on double occupancy

10 Uncovering the Real George P. Shultz cover story: Biographer Philip Taubman shares what he learned about the former secretary of state.

26 The Walter E. Hoadley

Annual Economic Forecast

Maurice Obstfeld and Michael Boskin talk with Ann E. Harrison about what they see happening to the economy in 2023.

34 Representative Jackie Speier: The Exit Interview

The Bay Area congresswoman talks with Melissa Caen on the occasion of her retirement from the House of Representatives.

42 Teresa Romero

The United Farm Workers union leader describes the need for more laws—and enforcement of laws already on the books.

ON THE COVER: George P. Shultz. (Official State Department photo.)

ON THIS PAGE: Top:

Speier.

Jackie (Photo by Ed Ritger.) Right: Teresa Romero. (Photo by Ed Ritger.)“Kids know when another kid has a gun or has the potential to shoot; they hear about it. That’s why these community officers are actually helpful to have on school campuses, because the kids are more likely to go and tell them.“

—JACKIE SPEIER

“For the first time in decades, farm workers who chose to stand up for their rights will at least be in a fair fight— without the union election process rigged against them.“

—TERESA ROMERO

April/May 2023

Volume 117, Number 2

The Commonwealth 110 The Embarcadero San Francisco, CA 94105 feedback@commonwealthclub.org

John

ZippererPHOTOGRAPHERS: Ed Ritger, Sarah Gonzalez.

ADVERTISING INFORMATION

John Zipperer, Vice President of Media & Editorial, (415) 597-6715, jzipperer@ commonwealthclub.org

The Commonwealth (ISSN 0010-3349) is published bimonthly (6 times a year) by The Commonwealth Club of California, 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco, CA 94105. Periodicals postage paid at San Francisco, CA. Subscription rate $34 per year included in annual membership dues. Copyright © 2023 The Commonwealth Club of California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to

The Commonwealth, The Commonwealth Club of California, 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco, CA 94105; (415) 597-6700; feedback@commonwealthclub.org

The Commonwealth magazine covers a range of programs in each issue. Program transcripts and questionand-answer sessions are routinely condensed due to space limitations. Hear full-length recordings online at commonwealthclub .org/watch-listen, or via our free podcasts on Google Podcasts, Apple Podcasts, Audible or Spotify; watch videos at youtube.com/ commonwealthclub.

Published digitally via Issuu.com.

facebook.com/thecommonwealthclub twitter.com/cwclub

youtube.com/commonwealthclub

commonwealthclub.org

instagram.com/cwclub

Those of you who have been to our headquarters on the waterfront know that the entire front face of the building is glass. This allows for incredible views of the bay and the Bay Bridge from the upper floors. And on the ground floor, of course, you get a full view of pedestrians on the sidewalk outside.

Not too long ago, I was sitting at the front desk, helping out with check-in for a program, when I noticed four people out on the street. They were acting like sightseers—you know, pointing at things in the distance, taking photos. Then they seemed to notice the Club’s building, and I assumed they had heard us on the radio in whatever city they lived in. Eventually, they came to the door to see if they could come in, and I let them in.

Why were they there? It turns out the daughter of one of the couples was an architect who worked on our building. In particular, the staircase from the first to second floors was designed by her. “That’s her staircase!” one of them said. The proud parents took pictures in front of the staircase and left.

someone who appeared on the Club stage many times as a speaker or moderator was the late George P. Shultz. He and his wife, Charlotte, were not only longtime and vocal supporters of the Club, they helped us many times during the multi-year effort to raise money, including hosting a meeting of donors at their home in the city, and they spoke at our groundbreaking ceremony and helped with advice during the long permitting process.

It’s not to much to say they were invaluable to us; they were supporters of the Club’s mission and willing to roll up their sleeves to get involved in keeping this cultural institution going.

Our cover story this issue focuses on George Shultz’s legacy, as told by biographer Philip Taubman. As you’ll see in the article that stretches across 11 pages, Taubman reveals previously unknown or little-known facts about Shultz’s life, including getting him to talk about some of the most painful moments of his career, from Watergate to Theranos. But those moments pale in comparison to his work to wind down the Cold War, reduce and eliminate nuclear weapons, and even confront bigotry.

Shultz was a legend, so I hope you’ll read the extended excerpt from the Taubman program and share my appreciation that there have been and still are people who dedicate themselves to making the world a better place, even when things seem uncertain.

The Commonwealth Club organizes nearly 500 events every year on politics, the arts, media, literature, business and sports. Programs

are held online and throughout the Bay Area in San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Marin County, and the East Bay. Standard programs are

typically one hour long and frequently include interviews, panel discussions or speeches followed by a question and answer session.

In addition to its regular lineup of programming, the Club features a number of divisions that produce topic-focused programming.

Climate scientists, policymakers, activists and citizens discussing energy, the economy and the environment.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/CLIMATE-ONE

The Club’s education department.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/EDUCATION

Inspiring talks with leaders in tech, culture, food, design, business and social issues targeted toward young adults.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/INFORUM

MEMBER-LED FORUMS

Volunteer-driven programs that focus on particular fields.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/MLF

Talks with LGBTQ thought leaders from a wide range of fields of expertise.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/MMS

WEEK TO WEEK

Political roundtable paired with a preprogram social.

COMMONWEALTHCLUB.ORG/W2W

TELEVISION: Watch Club programs on KAXT, KTLN and KCAT TV every weekend, and monthly on KRCB TV 22 on Comcast. Select Commonwealth Club programs air on Marin TV’s Education Channel (Comcast Channel 30, U-Verse Channel 99), C-SPAN, and on CreaTV in San Jose (Channel 30).

View hundreds of streaming videos of Club programs at youtube.com/ commonwealthclub

To request an assistive listening device, please e-mail Mark Kirchner seven working days before the event at mkirchner@commonwealthclub.org.

Subscribe to our free podcast service on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts and Spotify to automatically receive new programs: commonwealthclub.org/podcast-subscribe

RADIO: Hear Club programs on more than 230 public and commercial radio stations throughout the United States (commonwealthclub.org/watch-listen/radio). For the latest schedule, visit commonwealthclub.org/broadcast.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, tune in to:

KQED (88.5 FM)

Fridays at 8 p.m. and Saturdays at 2 a.m.

KRCB Radio (91.1 FM in Rohnert Park)

Thursdays at 7 p.m.

KSAN (107.7 FM)

Sundays at 5 a.m.

KALW (91.7 FM)

Inforum programs select Tuesdays at 7 p.m.

KNBR (680 and 1050 AM)

Sundays at 5 a.m.

KFOG (104.5 and 97.7 FM)

Sundays at 5 a.m.

TuneIn.com

Fridays at 4 p.m.

Prepayment is required. Unless otherwise indicated, all events—including “Members Free” events—require tickets. In-person programs often sell out, so we strongly encourage you to purchase tickets in advance. Due to heavy call volume, we urge you to purchase tickets online at commonwealthclub.org; or call (415) 597-6705. Please note: All ticket sales are final. Please arrive at least 10 minutes prior to any program. Select events include premium seating, which refers to the first several rows of seating. Pricing is subject to change.

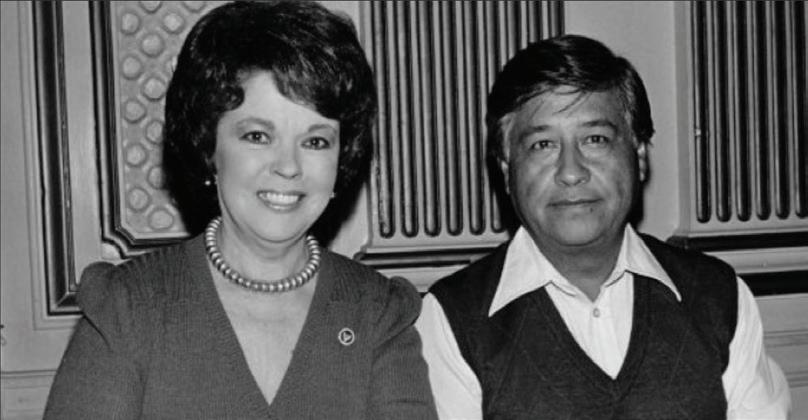

Four decades ago, Cesar Chavez, leader of the United Farm Workers, gave what became one of the most famous speeches ever delivered to The Commonwealth Club of California.

Marc Grossman, UFW spokesperson, tells us that Chavez’s Club speech has been widely shared, and excerpts from it are etched in marble and metal gracing monuments honoring Chavez across the nation; excerpts are also included in exhibitions and tributes to Chavez, who died in 1993.

As his successor at the UFW, Teresa Romero, relates in her own Club speech elsewhere in this issue of The Commonwealth, Chavez was initially reluctant to accept the invitation to speak from Club President Shirley Temple Black. Black was a well-known conservative Republican; why would she want to feature a left-wing labor activist on the Club’s stage?

But, as Romero relates, Black was a strong supporter of unions, having been a member of one since her days as a world-famous child actor. She and Chavez got along wonderfully, and in the process one of the most important speeches about labor rights and civil rights was given right here in the Bay Area.

In his 1984 speech, Chavez said, “For nearly

20 years, our union has been on the cutting edge of a people’s cause, and you cannot do away with an entire people and you cannot stamp out a people’s cause. Regardless of what the future holds for the union, regardless of what the future holds for farm workers, our accomplishments cannot be undone. . . . The consciousness and pride that were raised by our union are alive and thriving inside millions of

young Hispanics who will never work on a farm.”

As you’ll see when you read Romero’s powerful speech, the UFW has notched quite a few victories since 1984, but it still has a lot of issues it is addressing to ensure often basic human rights and labor rights for farm workers.

To learn more about the United Farm Workers, visit ufw.org.

Board Chair

Martha C. Ryan

Vice Chair

John L. Boland Secretary

TBD

Treasurer

John R. Farmer

President & CEO Dr. Gloria C. Duffy

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

PAST BOARD CHAIRS & PRESIDENTS

* Past Chair

** Past President

Dr. Mary G. F. Bitterman*

J. Dennis Bonney**

Maryles Casto*

Hon. Ming Chin**

Mary B. Cranston*

Evelyn Dilsaver*

Joseph I. Epstein**

Robert E. Adams

Willie Adams

Deborah Alvarez-Rodriguez

Scott Anderson

Dan Ashley

Dr. Mary G. F. Bitterman

David Chun

Charles M. Collins

Mary B. Cranston

Susie Cranston

Claudine Cheng

Dr. Kerry P. Curtis

Dorian Daley

Evelyn Dilsaver

Joseph I. Epstein

Jeffrey A. Farber

Dr. Carol A. Fleming

Leslie Saul Garvin

Gerald Harris

Peter Hill

Mary Huss

Michael Isip

Nora James

Dr. Robert Lee Kilpatrick

Alexis Krivkovich

David Leimsieder

Dr. Mary Marcy

Lenny Mendonca

Michelle Meow

Anna W.M. Mok

DJ Patil

Ken Petrilla

Skip Rhodes

Bill Ring

George M. Scalise

George D. Smith Jr.

David Spencer

James Strother

Hon. Tad Taube

Charles Travers

Don Wen

Dr. Colleen B. Wilcox

Brenda Wright

Mark Zitter

John Farmer*

Rose Guilbault*

Claude B. Hutchison Jr.**

Anna W.M. Mok*

Richard Otter**

Joseph Perrelli**

Toni Rembe**

Victor J. Revenko**

Skip Rhodes**

Renée Rubin**

Richard Rubin*

Connie Shapiro**

Nelson Weller**

Judith Wilbur**

Dennis Wu**

Karin Helene Bauer

Hon. William Bradley

Dennise M. Carter

Steven Falk

Amy Gershoni

Jacquelyn Hadley

Heather Kitchen

Amy McCombs

Don J. McGrath

Hon. William J. Perry

Hon. Barbara Pivnicka

Hon. Richard Pivnicka

Nancy Thompson

YOUR GUIDE TO IN-PERSON & ONLINE EVENTS AT THE COMMONWEALTH CLUB

Every week we’re adding more programs to the calendar. So check commonwealthclub.org/events for the latest updates. Also subscribe to one or more of our email newsletters at commonwealthclub.org/email

We look forward to seeing you soon in-person at one of the discussions, wine tastings, jazz performances or other great reasons to gather with others in your Commonwealth Club community.

Philip Taubman on

Philip Taubman on

BIOGRAPHER PHILIP TAUBMAN DRAWS ON GEORGE SHULTZ’S PERSONAL PAPERS to shed new light on how Shultz helped shape U.S. foreign policy at a crucial time in world history. From the January 31, 2023, program “Philip Taubman on George P. Shultz: The Life and Legacy of a Great Statesman.” This program is part of our Good Lit series, underwritten by the Bernard Osher Foundation.

PHILIP TAUBMAN, Lecturer, Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation; Former Reporter and Editor, The New York Times; Author, In the Nation’s Service: The Life and Times of George P. Shultz

In Conversation with DAVID KENNEDY, Professor Emeritus of American History, Stanford University; Former Director, Stanford’s Bill Lane Center for the American West

DAVID KENNEDY: Philip is here to discuss . . . George Shultz’s long career in public service at the Bureau of the Budget—later the Office of Management and Budget—secretary of labor, secretary of the treasury and eventually secretary of state. One of only two people, if my memory serves, who have held that many cabinet or cabinet-equivalent positions. And after he left formal government service, he also had a major role to play in an effort to reduce or even eliminate nuclear weapons.

Let me begin with what might be a little bit of an embarrassing note, Phil. I have to say I found this book to be uncommonly interesting and not just because it’s an interesting subject, namely George Shultz, but I was really in many points in awe of the extent and depth of your research and the felicity of your writing.

So let’s begin with you. Where were you born? Where you raised? What was your educational formation? What was your career? And what was the pathway that led you to this particular project?

PHILIP TAUBMAN: Thank you for those kind words, David. Coming from you, that means a lot.

I’m a New York kid. I grew up in Manhattan, went to high school there, came out here to Stanford University as an undergraduate. When I put my luggage down in my freshman dorm, the first place I headed was the offices of the Stanford Daily, because I wanted to be a journalist.

That was probably because my father was a journalist, worked at The New York Times for 40-plus years as a music critic and a drama critic. I got the bug traveling around the world with him. So I did go into journalism, first at Time magazine and then a brief period at Esquire and then eventually The New York Times, and increasingly got drawn into reporting about national security affairs.

That’s where I first met George Shultz, when he was secretary of state and I was helping to cover the State Department for The New York Times Washington bureau. And that began a relationship with him that was kind of suspended after he left office in early ’89. I observed him in the Washington bureau, and then I moved to the Moscow bureau of the Times. In those days, he was traveling back and forth once Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet leader. So I observed him there. We played tennis a few times—

KENNEDY: Who won?

TAUBMAN: Well, that’s a good question [laughter], because the first time was when his aide told me to bring a racket on the next trip, and we found ourselves in Rio. One afternoon and I got a call up in my hotel room and [they] said the secretary would like to play tennis. So off we went to the tennis court. We’re volleying, and I’m thinking to myself, Am I allowed to beat the secretary of state? [Laughter.] So it turned out he was a very steady player, like the man himself. But at any rate, I was in Moscow. He left office. I came back, and when we sort of fell out of touch, what actually led to this book project was the prior book that I did on Shultz, Bill Perry, Henry Kissinger, Sam Nunn and Sidney Drell down at Stanford and their effort to eliminate nuclear weapons. It was during the course of doing that book that Shultz said to me one day, “Would you be interested in writing my biography?”

KENNEDY: What was the title of the book

you did on those five?

TAUBMAN: The Partnership: Five Cold Warriors and Their Quest to Ban the Bomb

KENNEDY: Another excellent book, by the way. So crucial points in your own career and Shultz’s overlap and gave you insight not only to the world of Washington, D.C., where you were bureau chief, I’m not mistaken.

TAUBMAN: Eventually, in Washington bureau chief at the Times. Correct.

KENNEDY: And you were bureau chief in Moscow as well. So did that give you any particular perspective on the U.S.-Russian relationship?

TAUBMAN: Oh, absolutely. Here were the two superpowers, and I had the privilege of writing about the Cold War, first from Washington and then from Moscow. And I think when I got to Moscow with my wife, Felicity Barringer, who at the time had been working for The Washington Post, we were both struck very quickly by how depressed the Soviet economy was. It was a centrally planned economy. It was sputtering when we got there. A huge investment was being made in the defense for the Kremlin. And it became clear after a month or six weeks that the Soviet Union was really a developing country with nuclear weapons. So that helped me understand the Cold War in a way I would not have before.

I think that helped me understand something that became important for Shultz and Reagan and then figures prominently in the book, which was one of the motivations for

Mikhail Gorbachev to wind down the Cold War was that he understood, unlike his predecessors, that the Soviet economy could not sustain that kind of military expenditure and provide any kind of consumer goods for the Soviet citizens.

KENNEDY: So let’s say that we could revive George Shultz and bring him into the room here. Make us understand him as a human being. What made him tick? What was his own formation? What was he like? What kind of guy was he?

TAUBMAN: The George Shultz I knew turned out to be several different people and in a way that had less probably to do with him than the perspective I had on him. So when you’re covering the secretary of state as a reporter for The New York Times, you’re kept at a distance. You’re traveling around the world with the secretary, but your access is limited and it’s very much controlled. What you’re seeing is the persona that the State Department and the secretary want to project. And that persona of George Shultz was a very reserved person. Very few words, tried not to make news when he was talking to reporters. His nickname around the State Department in those days was the Sphinx, because he was so quiet. And he was a good listener, but he was not a gregarious person.

Fast forward to the time I’m dealing with him for the research for the book [and he] seemed like an entirely different person. Gregarious, outgoing, fun loving. I think this was clearly partly a function when you’re secretary

of state, you keep a certain demeanor. His first wife had died by the time I renewed my relationship with him. His first wife, Obie, was a wonderful, thoughtful, but very quiet and modest person.

When he remarried—and people in San Francisco will know his second wife very well, Charlotte. She was the chief of protocol for San Francisco and the state of California. And nobody knew how to throw a party better than Charlotte. And so George adopted this kind of party-loving mode that Charlotte presented. And the second George Shultz I met was a very playful person, like to joke around, dance, sing. So when you ask the question, I have to answer in the sense that I saw him transition from this very reserved figure to this very outgoing figure.

KENNEDY: You make me recollect, when he came back to Stanford after leaving office, among many other occasions that he organized was a reception for Eduard Shevardnadze. To honor Shevardnadze on that occasion, George got up and sang a cappella, “Sweet Georgia Brown.” [Laughter.] It was awful. It was just terrible singing. But that was a side of him that you wouldn’t have seen when he was [at the State Department].

TAUBMAN: But actually, it turned out he did exactly that when he was secretary of state. To talk a little bit about Shultz as a diplomat: He wanted to establish a rapport with the people that he was dealing with. It was almost impossible to establish rapport with Andrei Gromyko, the longstanding Soviet foreign

minister, who was this implacable, belligerent figure. Once he was replaced by Eduard Shevardnadze, who came from Georgia—it’s not on the Mediterranean, but the people of Georgia are kind of a Mediterranean people. They’re warm, friendly. They love to have dinner parties, drink their wine and their cognac. And Schultz developed this wonderful relationship with Shevardnadze, which, actually, when you go back and look at the end of the Cold War, it was that relationship between the two foreign ministers that was, I think, almost as important as the relationship between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.

So at one point when they were negotiating at the height of the Cold War, he did exactly that with Shevardnadze. He arranged this lunch where he sang “Georgia on My Mind.” They did a version in Russian, and Shevardnadze loved it.

KENNEDY: I wish I had heard that; that would have been memorable.

Before he entered government service, he had another career as an academic and as an economist at MIT. He taught there for a while, then went to Chicago. Tell us a little something about the academic side of his career.

TAUBMAN: Shultz always thought of himself as an academic.

He’d been a marine in World War II in the

Pacific theater, was involved in combat. He came back, took up an admission that had been approved before he went off to the war to do graduate work at MIT in economics, got his Ph.D. there, became an assistant professor there.

Interestingly, one of the courses he took was with Paul Samuelson at MIT, who was a young rising star in economics.

KENNEDY: And a Keynesian.

TAUBMAN: Yes, a Keynesian. And because it was the postwar period, George Shultz took a course from Paul Samuelson. It was just George Shultz and one other student in the course. Talk about a seminar. Wow. That’s amazing.

So he then moves to Chicago and Milton Friedman and the whole Chicago School of Economics, which is free market economics. He became a disciple of free market economics. I tried to get him to explain to me later in life, and he never really gave me a satisfactory answer, how he had moved from taking Paul Samuelson’s course and thinking the world of Paul Samuelson and then ends up at Chicago, being the sort of opposite of a Keynesian economist.

KENNEDY: The Chicago school is famously anti-Keynesian. But he was unable to explain adequately to you how he made that intellectual [switch].

TAUBMAN: You know, I think he was persuaded. It’s interesting to think back. During the Depression, George was a young man and Franklin Roosevelt [was president]. All the efforts that FDR made to revive the American economy during the Depression, which I think most Americans looked at and thought he was making progress and doing the right thing—not George Shultz. As a young man, he looked out at the American economy and came to the opposite conclusion, which was that for all FDR was doing, it wasn’t working. So at that point, in the 1930s, he became a Republican. He became convinced that government intervention in the economy was essentially a bad idea, and he carried that through to his dying day. He remained very much a member and leading light of the Chicago School of Economics.

KENNEDY: And he thought that anyone who believed otherwise wasn’t a true economist.

TAUBMAN: Exactly.

KENNEDY: Richard Nixon is the person who first elevates him into significant public office. If I’m not mistaken, he appointed [Shultz to] his first three cabinet posts at OMB, Labor and Treasury. So tell us a little bit about his career there in the Nixon administration.

TAUBMAN: It’s interesting. Shultz made a name for himself as a labor economist. And then after a number of years as dean of the University of Chicago Business School, he took a sabbatical [and] came out here. This was his first contact with Stanford Universi-

ty, The Center for Advanced Studies. They introduced him to his office in the foothills overlooking the campus. And he looks in his office. There’s no telephone. He goes to the director and he says, “What’s up? I use the telephone all the time. There’s no phone in my office.” And the director says, “No, we do not have phones in offices here. I think you’ll come to find that you like that.” And he did.

But he did get a call from Richard Nixon— must have been in the main office. Nixon, who was campaigning for president, invited him to provide some advice. His mentor and connection to Nixon, interestingly, was Arthur Burns, who later became chairman of the Federal Reserve. George Shultz had gone to Washington in 1955 to work on the staff at the Council of Economic Advisors in the Eisenhower White House, and the chairman of the council was Arthur Burns. That’s where their relationship began. Nixon’s elected in ’68, and he invites Shultz to come be his secretary of labor.

Shultz goes down to L.A. to meet with the president-elect, and he finds Nixon to be a kind of odd duck, in a way. He’s there, he thinks, being interviewed for this job, even though it’s already been offered. But he figures Nixon wants to figure out exactly what kind of labor secretary are you going to be. It turned out, according to Shultz, that Nixon seemed very insecure during the interview and he always remembered that interestingly. So he becomes secretary of labor. The day comes when he is announcing all the subcabinet officials in his department. There’s a

news conference in New York, I think it was. He goes down the list, he announces seven or eight people. Not a single one of them is a Republican. They’re all Democrats or independents. It had never occurred to him because he was not a particularly political figure, that when you’re staffing up in a Republican administration, the expectation is that you’re going to appoint Republicans.

So he got a angry phone call from a Nixon aide after that, essentially saying, “George, what the hell are you doing? You know, you’re appointing all these Democrats.”

Secretary of labor—his greatest achievement and most people don’t even know about this, was that George Shultz led a task force in the Nixon administration to desegregate urban public school systems in the South. When they started that project, less than 25 percent of the urban school systems in the southern states were desegregated. By the time they finished, 75 percent were. So this was an amazing achievement by George Shultz that has kind of been lost to history, because he became famous as secretary of state.

KENNEDY: Somewhat better known is the Philadelphia Plan, also an initiative in the same direction.

TAUBMAN: Exactly. He helped to desegregate the trade unions—the plumbers, electricians and all of those unions, which were mostly occupied by white men in those days. George Shultz believed in civil rights. He believed in equality. He wasn’t a fervent believer. You know, Martin Luther King was leading marches in Chicago when he was a

dean at the University of Chicago. He wasn’t out there marching. But what he did do was to shake up the University of Chicago admissions process so that they could bring in more people of color to the business school. Then he did this effort with the building trades and then with the southern school systems.

KENNEDY: You tell a touching story about a trip he made to Fort Worth, Texas, in 1962 and a confrontation in the hotel lobby over a black person trying to get a room.

TAUBMAN: At this point, the meatpacking industry was going through a huge transformation. Historically, the stockyards had been based in places like Kansas City and Chicago, and the cattle had been driven to them from the farms where they were raised. The industry figured out this was not very efficient and that they should disperse the stockyards out closer to the places where the cows were being raised, which required an upheaval.

The union was a heavily Black union at the time in places like Chicago and Kansas City. And they were threatened by this because the workforce out closer to the farms was not going to be predominantly black. So George was brought in to help figure out how to make this transformation without costing a lot of jobs to Black union members. So he shows up in Fort Worth that day with his aide from the University of Chicago—

KENNEDY: This is when he’s dean?

TAUBMAN: —he’s dean—and a Black union representative. They arrive at the hotel desk and they check in, and the clerk checks in George Schultz, checks in his aide. They

get to the Black union leader, “I’m sorry. We don’t have a reservation for you.”

So Schultz says, “What do you mean? We made reservations for three people.”

“We’re sorry, Mr. Schultz. We don’t have a reservation.”

So he says to them, “Check your records.” They come back out. They said, “We don’t have a reservation. He says, “Put them in my room. There are two beds.” They go back and they consult again and they find a room.

That was a wonderful kind of courageous thing, a human thing for George Schultz to do.

KENNEDY: But as you say, he wasn’t conspicuous in the public eye.

TAUBMAN: He was not a fervent advocate of civil rights, but he quietly did things that advanced the interests of people of color in the United States.

KENNEDY: What about while he was at Treasury in the next administration? Any landmark accomplishments there?

TAUBMAN: Well, there is a landmark accomplishment that we all still enjoy today, which was the exchange rate for international currencies when he became treasury secretary was pegged to the dollar, which was pegged to the price of American gold reserves at Fort Knox, $35 an ounce. It was unsustainable, because dollars were circulating in far greater

amounts than gold reserves were available to back them up.

Nixon realized they had to do something drastic, and he asked Schultz to design a new exchange rate system, which George did. So the floating exchange rate system, which still exists to this day, was basically his creation.

KENNEDY: How did he get along with Nixon personally?

TAUBMAN: Good and bad relations. He thought Nixon was doing good things domestically. And in fact, when you go back and look at the Nixon administration, the Environmental Protection Agency was created by Richard Nixon. Nixon was progressive on some domestic issues. He got involved in the desegregation issue because he realized that the Supreme Court had mandated this. But Nixon also, of course, was responsible for the Watergate burglary and the coverup and the Watergate scandal. George got drawn into this himself in a way that he didn’t want to talk about.

KENNEDY: Not even to you.

TAUBMAN: No. People remember that John Dean, the White House counsel, went to the IRS in this period and presented them with a list of dozens of names of Nixon’s enemies. John Dean said to the IRS commissioner, a South Carolina gentleman named Johnnie Walters, “We want the IRS to investigate

all of these people.” Walters was offended. He went to the treasury secretary, George Shultz, who agreed they put the list in a safe. Shultz instructed Walters “If John Dean calls you back, tell them to call me.”

So that’s great. But what he didn’t want to talk about was that Nixon leaned on him to have the IRS investigate Larry O’Brien. You may remember why the Watergate burglary took place—to break into the offices of Larry O’Brien, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Nixon believed O’Brien was a very effective political operative for the Democratic Party. He wanted the IRS to find tax problems for Larry O’Brien. And sadly, George Schultz condoned that. The IRS went into a frenzy of investigating Larry O’Brien for his connection to Howard Hughes, the billionaire, who was holed up in the top floor of his Las Vegas hotel, because he feared that if he met anyone outside his hotel suite, he would get sick.

So George condoned that. The records of these were found by a wonderful research assistant I had at Stanford. And when I sat down with George to look at all the records of the special prosecutor of Watergate that detailed all of this, he looked stricken. I was actually concerned he might have a heart attack in the interview, because he was so upset to have us ask him about this.

I would say, looking back at his record as secretary of treasury on economic issues, he accomplished a lot, but he got drawn into Watergate in a way that he should not have.

KENNEDY: You write that he was the last of

the Nixon appointees to resign, which I don’t think is quite right. I think Kissinger stayed to the end, I believe.

TAUBMAN: Right. But he stayed in the Nixon cabinet. Kissinger started as the national security advisor. So Shultz was the last person appointed to the Nixon cabinet initially who stayed.

KENNEDY: Yeah. And you think he had some regrets about [that].

TAUBMAN: Well, he told Arthur Burns he should leave. If you go back, one of the wonderful things about doing research for a project like this is you find all this historical material. And lo and behold, Arthur Burns did a memoir and kept a diary. I think most people didn’t realize that. I certainly didn’t. There in his diary, he has entries talking about his private conversations with the treasury secretary, George Shultz. And Shultz is confiding in him that Nixon is deeply involved in Watergate. It’s criminal conduct. He’s uncomfortable working for Nixon, but he won’t quit. He didn’t quit until May of ’74. Nixon resigned in August of ’74. He stayed. He stayed too long.

KENNEDY: There’s a pattern here, it seems to me, reading your book, that he on several occasions threatened to resign over the Nixon administration, the Reagan administration, but never did. He stays on even when things are starting to look a little shady. But we’ll get to that, because it’s another part of the story that really comes [into] better focus a little bit later.

Let’s let’s move to what I suppose is his

most famous and consequential period of service, which was as secretary of state in the Reagan administration. You commenced that discussion with a nice, concise history of the state of the Cold War at that moment. You rest a lot of the argument on national security decision Directive 32, which I think is dated 1982, if I remember correctly, which kind of summarizes the state of the Reagan administration’s dominant policy thinking about relations with the Soviet Union, the Cold War generally.

So set the scene for us there, what it looked like when George came in.

TAUBMAN: You have to remember, the key thing is that at the beginning of the Cold War, the United States adopted the doctrine of containment. This doctrine was the creation of George Kennan, who was the U.S. ambassador in Moscow after the war ended. His theory, which was consistently adhered to through most of the Cold War, was that we have to contain the Soviet Union militarily, economically, politically, because it’s an expansionist power.

That had been the doctrine guiding presidents beginning with Harry Truman. Reagan comes into office, and he essentially wants to not only double down on containment, he wants to do something different. He doesn’t want to just contain the Soviet Union. He wants to roll back Soviet advances around the world. And that’s the core of this national security memo that you describe.

KENNEDY: The phrase roll back goes back at least as far as [Eisenhower’s Secretary of

State] John Foster Dulles.

TAUBMAN: Yeah. But you know, Reagan was really determined to do it. He came into office with this belligerent rhetoric about the Soviet Union, the evil empire. Communism is going to wind up on the ash heap of history—very aggressive rhetoric about the Soviet Union, a huge military buildup supported by Congress, Democrats and Republicans. Remember, it’s the height of the Cold War.

So the whole strategy is to throw the Soviet Union back on its heels. Alexander Haig, Reagan’s first secretary of state, believes in this. But there’s a very interesting moment early in the Reagan presidency. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, writes a boilerplate letter to Reagan that talks about, you know, we need to find peace and try to reduce tensions. The State Department looks at the letter and said this is just the usual propaganda from the Kremlin. They write a response that’s a boilerplate American response. They give it to Reagan. He looks at it. He says, “I don’t want to send that letter.” He sits down and he writes by hand his own letter to Brezhnev.

And it is an amazing letter. When you go back and look at it, it is the letter of a naive idealist. It’s a letter that talks about how we must have peace between our peoples and there’s no need to have this tension. It was a reflection of an inner Reagan that was not visible publicly, really, at this time.

He hands this letter to the State Department. They go back, they rework their letter a little bit. They send back their letter to the president. They say, we want to send this letter

to Brezhnev. He says, “Okay, here’s what we’re going to do. You’re going to send your letter and you’re going to send my letter.” And they did it. The people around Reagan—Haig and others, Cap Weinberger—they all thought, “This is crazy. What is the president doing writing a kind of soporific letter like this to the Soviet leader?”

So Shultz comes to town— KENNEDY: To replacer Haig?

TAUBMAN: Yes. Replaces Haig, who’s fired, because—remember the day Reagan was shot and Vice President Bush was out of town and Haig goes into the White House press room and announces to the world, “I’m in charge here”? Which seemed like usurpation of power. Anyway, Reagan fires Haig, brings Shultz in, who has very little foreign policy experience and makes him secretary of state. But what Shultz had, which I think you’ll see in the book, he was aligned with Reagan in ways that the two men didn’t understand when their relationship began. Shultz had gone to the Soviet Union during the Nixon administration, and Shultz believed in experiential learning. Basically, he believe you could tell more with your eyes and ears than you could often learn from intelligence reports.

So he went to the Soviet Union with his wife. She goes to a hospital; she had been a nurse during World War II. She comes back and she says to her husband, “It’s unbeliev-

able. It is like a medieval hospital there. No sanitary, no hygiene. There are multiple operating tables in the same room.” She fills him in on the meager, bleak state of medicine in the Soviet Union.

He goes to a Black Sea resort. And what do they do when they’re there? They take him to a Tsarist palace that they’ve restored. The guide with Shultz says, “We wanted to show this to you so you’ll understand that the communist leaders of this country invest in things other than defense.” He looks at that and he says, “Wow, isn’t that an interesting insight into this country?”

So what Shultz understood viscerally and Reagan understood kind of intellectually because he’d read about it, was that the Soviet Union was a failing state economically. So as secretary of state, he believed [the Kremlin] had an incentive to try to ease tensions, and he wanted to ease tensions.

KENNEDY: Among his adversaries inside and adjacent to the Reagan administration was the so-called Committee on the Present Danger. At least one of the members of that I knew a bit, Richard Pipes. So tell us a little bit about them and how effective they were in trying to counter the Shultz view.

TAUBMAN: They were very effective. Shultz shows up in Washington and becomes secretary of state. He really doesn’t have a relationship with Reagan apart from discus-

sions they’ve had over economic policy issues. As I said, he doesn’t really understand what Reagan wants to do with the Soviet Union. Everything that he’s seen and heard is harsh confrontation. So he tries to get face time with the president.

If you’ve spent any time in Washington, one of the things you learn very quickly is that the secretary of state is only as effective as his or her relationship with the president. Shultz didn’t really have much of a relationship with Reagan, so he wanted to establish one. He keeps asking to have meetings with the president one-on-one, and every time something is arranged, he goes over to the White House and he walks into the Oval Office or the Cabinet Room, and it turns out there are a dozen people there, most of them opposing his proposals to try to ease tensions and open a diplomatic communication with the Kremlin.

It’s interesting you mentioned Richard Pipes. He was a Harvard professor, an expert on the Soviet Union. He had come down to Washington to work on the national security staff. He thought that George Shultz was in way over his head. When I went back and read Richard Pipes’s book and his accounts of the presidency, he’s incredibly dismissive of George Shultz.

KENNEDY: As was Haig

TAUBMAN: As was Haig, [dismissive of Shultz] as a lightweight.

KENNEDY: Just an economist.

TAUBMAN: Yes. Haig at one point said to Shultz, basically, “I don’t know how you’re going to do this job, you’re just an economist.” And Pipes was very dismissive.

So at one point, Shultz goes over to a meeting with Reagan, and he looks around the room and Pipes is sitting there. As Shultz later described it to his aide—who, by the way, kept this amazing diary of all of this, which plays a large part in the book—Shultz looks around the room and he sees Pipes there. And he turns to Reagan, and he says, “Who’s that?” [Laughter.]

KENNEDY: And then what?

TAUBMAN: And it turns out it was Pipes who was opposed to everything he wanted to do. So Shultz would come back to the State Department and say to his aide, Ray Seitz, “How is it that the secretary of state cannot have a one-on-one meeting with the president of the United States, to talk about U.S.-Soviet

relations?”

KENNEDY: So eventually Reagan and Shultz align. But again, as you present it, that took a lot of work on Shultz’s part and Reagan appears, at least in your account, as sort of the passive or subordinate partner in this enterprise. You make a great deal of a dinner they had during a Washington, D.C., blizzard where Nancy Reagan connected with Shultz.

TAUBMAN: Yeah. So if you look back at history—you’re the historian here—it was so stunning to me to see that the end of the Cold War began in many ways, thanks to Mother Nature and thanks to Nancy Reagan, because it was this huge blizzard in Washington in February of 1983. My wife and I were living there at the time; two to three feet of snow fell. I remember we went out and people were skiing on Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown. Traffic was dead. Nobody was moving.

The Reagans had planned to go to Camp David. They couldn’t get there. So Nancy Reagan took advantage of the blizzard. She was concerned that her husband was being depicted as a warmonger, that his legacy was going to be raising tensions during the Cold War rather than reducing them. So she saw this opportunity at the blizzard, picked up the phone, called the Shultzes, said, “Come over to dinner.” They did. And that dinner was a turning point.

KENNEDY: What’s the date?

TAUBMAN: It was early February ’83. And for the first time—Shultz has now been secretary of state for 7 or 8 months—he has a one-on-one conversation with the president and with Nancy and with Obie. He realizes that night that he and the president actually share this desire to wind down the Cold War.

From that day forth, even though it took him several more years to essentially gain control of U.S. foreign policy, he knew the president and he agreed. So as all of this flak was thrown up around him to try to prevent the policies he was advocating from being advanced, he knew that eventually—he hoped, at least—Reagan would move aggressively in his favor, which he eventually did.

KENNEDY: Let me ask you kind of a big, maybe unanswerable question at this stage of the game, but let’s try to tackle it anyway. There’s a school of thought that Reagan came into office with this notion that he could spend the Soviets into oblivion and challenge

them technologically with the Strategic Defense Initiative, or Star Wars. And this would make it clear to them they could not compete any longer and they would have to throw in the towel.

In your book, I don’t quite get the sense that’s a proper narrative, that without Shultz’s presence in that scenario, the story could have ended very, very differently. It comes into focus, it seems to me, to a certain extent, at least at the famous meeting in Reykjavik in Iceland in 1986, when there was a real chance to end the technological competition in space and take a gigantic step toward reconciliation between the Soviet Union and United States.

Do you buy that narrative, which is quite well-formed in some quarters, or do you think it needs qualifying?

TAUBMAN: I think it needs qualifying and I hope my book qualifies it in the following way. There’s no doubt that Reagan came into office determined to confront the Soviet Union, as I said, to throw the Soviet Union back on its heels. Major defense spending and then the announcement of the Strategic Defense Initiative, which was this technologically exotic space-based shield that would, in theory, knock down all incoming Soviet ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

So he did succeed in putting the Kremlin on the defensive. What he didn’t know to do until George Shultz showed up was how to translate that into an effective diplomatic strategy. I think absent George Shultz, no matter what Ronald Reagan’s overarching strategy was when he came to Washington, he would have had a hard time succeeding in winding down the Cold War absent George Shultz as secretary of state.

KENNEDY: Let me share a story. When George came back from public service, he was on the Stanford campus. Among the things he did for several years, he convened an annual conference organized around the statesmen around the world in his era. More than once I attended these occasions and the format was, there would be a very nice dinner and maybe somewhere in the neighborhood of a hundred people in the room. And then his invited guests each had 10 minutes to get up and give their view of the world. I can remember on one of these occasions the speakers were, through the evening, Giscard d’Estaing, the former president of France, Lee Kuan Yew from Singapore, Oscar Arias from Costa Rica, Geoffrey Howe from the U.K. and Helmut Schmidt [from Germany]. They each gave in 10 minutes their review of the state of the world. And one was more impressive than the next. I mean, they were really senior, serious

“Shultz understood viscerally and Reagan understood kind of intellectually . . . that the Soviet Union was a failing state economically.”

statesmen who really have sophisticated views of the world.

A day or two or three later, I ran into George on campus, thanked them for including me on this occasion. I said, “You know, I can’t help asking if your former boss, Ronald Reagan, had been on the program that evening and asked to get up and give his 10-minute view of the world, how would he have compared with those very impressive gentlemen who got up and spoke?”

His reply to me was, “David, I’ve been in the room with Ronald Reagan and every one of those people, and he dominates every single one of them.”

I did not take that at face value at the time. But you know more about his view of Reagan than I do. So that’s the question. What did George think of Ronald Reagan?

TAUBMAN: Well, he idolized Ronald Reagan to the day he died. I think I understand that to some extent, because the two men, once they forge this working relationship and once Reagan came to understand the value that Shultz brought to the table as a diplomat, the two of them proceeded to wind down the Cold War with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze.

But what George forgot when he told you that, and you can see it in the Seitz diary day after day after day—it’s in detail, wrenching detail at times—is how often Shultz was disappointed by Reagan, and he was disappointed because he couldn’t get Reagan to intervene, to try to settle this internecine warfare that was going on in the Reagan administration.

He couldn’t get the president to stick to decisions that he had made. So, for example, there are cases where Shultz thought that the president had agreed to do something and then it was undone by other aides because Reagan wasn’t paying attention or because the White House chief of staff or the national security adviser wasn’t following up on the decisions. There are a whole series of these things outlined in my book, and they were outlined in Seitz’s diaries. Some of them happened, and later, after Seitz left office, Reagan operated in a disengaged way, often in his presidency. He set the goals.

KENNEDY: You used the word inattentive

TAUBMAN: Inattentive. Disengaged. He set the goals. He was a fantastic communicator. My God, when I go look now at some of the videotape of him, he had this uncanny ability to radiate optimism. You look back at that man and you could see why he was elected overwhelmingly as president two times. You compare that to leaders today, it’s like stunning. Where is that sense of optimism

and hope and energy that he conveyed?

But in the field of national security affairs, it was a more uneven performance. And so I think George had a tendency to be very loyal and respectful of the people with whom he worked and under whom he served. Look, when you look back on the Nixon presidency, there’s the Watergate scandal, you can’t escape it. And yet when Shultz retired, he wrote this incredibly flattering letter to the president, thanking him for the opportunity to serve. No criticism whatsoever. And with Reagan, you look through George Shultz’s correspondence with Reagan at the Hoover Institution archives at Stanford. It’s all flowery, flattering stuff back and forth. He had a hard time, I believe, sometimes reckoning with the weaknesses of some of the people he worked with.

KENNEDY: I think, if I counted correctly, he threatened at one point or another four times to resign over the course of his career under those two presidents. Were any of those in the Reagan [administration]?

TAUBMAN: Yes, most of them were during Reagan. In fact, one day I asked my research assistant to go back and—because it’s kind of interspersed in all the records, it’s hard to figure out how often he threatened to resign. So she did a careful study of it, and it was seven or eight times during the Reagan presidency when he threatened to resign. He used that as leverage. But, you know, he never acted on it.

KENNEDY: Which of those was the most plausible, or felt most deeply?

TAUBMAN: You know, I think it was the day he went in to [see] Reagan, and he was so thoroughly disgusted at the way he had been outmaneuvered and blindsided on some decisions involving American covert military and intelligence activity in central America. During the Reagan administration, that was a big emphasis. They feared that communism was coming to America’s doorstep on the Mexican border. There was Cuba, of course. Then there were the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, who were viewed as left wing and sympathetic with the Kremlin. And there was all the upheaval going on in El Salvador that the Reagan administration thought would lead to some kind of leftist government there.

Behind his back, the Reagan hardliners put through a bunch of decisions that the president actually approved—the secretary of state knew nothing about them—to increase all of this military and intelligence activity. So he stormed into the White House one day with a decision to resign. He told the president who the potential successors were. I think that’s the closest he came. Reagan didn’t want him to resign. By this point, Reagan understood that

his presidency would not be a success without George Shultz. He insisted that he stay.

KENNEDY: So George can pull his punch, but rather Reagan talked him out of it.

TAUBMAN: Well, Reagan said, “I won’t accept your resignation.” Well, of course, he still could have resigned.

KENNEDY: Interesting. A member of the audience asked the following, Phil, and I think this refers to the INF and the Pershing II missile controversy. Did Shultz worry about accidental nuclear war when precise first strike missiles were introduced into Europe in an attempt to bankrupt the Soviets?

TAUBMAN: It’s interesting. He was kind of divided about nuclear weapons as secretary of state. He believed in the importance of maintaining the American nuclear arsenal. He believed it was pivotal, really important to get these Pershing intermediate range missiles placed in West Germany, because the Soviet Union was putting similar missiles in the western territories of the Soviet Union.

It was actually, if you look back again at the end of the Cold War, this was a truly pivotal moment when Helmut Kohl, the German chancellor, agreed to have these American Pershing missiles placed in West Germany. And it was a moment that essentially signaled to the Kremlin in decisive terms that, “We are here to confront you. We’re not backing down.” It registered in a way that I think ultimately affected the Soviet thinking about trying to end the Cold War. So at that point, he was happy to see more nuclear weapons put into the field. But under that, both he and Reagan shared a real concern about the potential for a nuclear war.

When they got to Reykjavik, it was a snap summit. It was unlike any other previous Cold War summit, where there’s all kinds of preparation and the document [prepared], the summit is negotiated before the two leaders really ever get together. They went to Reykjavik on short notice. There was no communique prepared ahead of time, didn’t know what was going to happen. And Gorbachev drives up with all kinds of far-reaching proposals, which, again, give Reagan credit for this. He went to the Politburo, Gorbachev, and he said, “I’m going to Reykjavik. I’ve got these big, dramatic arms cut proposals I’m taking with them. And we have to reduce our defense expenditures. We cannot sustain them.” Reagan gets to Reykjavik with some pretty good proposals, too, that had been developed on the American side. And they’re seated at this table in this cozy little room overlooking the North Atlantic Sea. They’re there for two days and they came so, so close to agreeing to

eliminate nuclear weapons.

KENNEDY: Eliminate?

TAUBMAN: Eliminate, abolish them; not just reduce them, abolish them. The whole thing ran aground when Gorbachev said, “Okay, we can make a deal, but you got to do something to cut back on your Strategic Defense Initiative.” The deal he offered Reagan was not a bad deal at the time. He said, “Why don’t you just agree to limit research on all this exotic defense technology to the laboratory?”

Reagan said, “No, I won’t accept that.” At one point, at the most dramatic moment at Reykjavik, and it was a really dramatic summit, he hands a little note across the table to Shultz and says, “Am I doing the right thing?” And Shultz says, “Yes.” So they came very close to this historic agreement. They couldn’t agree. The talks collapsed, actually. If you go back and look at the photographs, there’s this grim photograph—Reagan’s getting into his limo, Gorbachev is standing there. They both look as if they’re at a funeral.

But it turned out that the groundwork that was laid at Reykjavik actually made it possible within the next year to come to agreement, to eliminate those intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe.

KENNEDY: There’s a school of thought—I associate it with your brother, Bill Taubman, who’s written a terrific biography of Gorbachev—that the Reagan-Shultz outreach to Gorbachev went cold or went dormant when George H.W. Bush came in. Bush 41. And the inattention to Gorbachev in the years immediately following Reagan and Shultz’s exit from office was fatal for Gorbachev, and that led to his being ousted as the leader of the Soviet Union [anad it] collapsing.

TAUBMAN: Well, you know, it’s a complicated issue. It is the roots of what Vladimir Putin would tell you was his justification to invade Ukraine. I don’t buy that. But that’s his justification, that as the Cold War was ending the United States, rather than trying to help Russia recover from communism and rebuild its economy, decided to expand NATO to its borders, which Putin certainly perceived as threatening.

But to go back to the beginning of your question, this was a kind of poignant and important moment. George H.W. Bush has been elected president. Gorbachev surprises Reagan and the president-elect by saying he’s coming to New York to speak to the U.N. in December of ’88. Suddenly there’s an opportunity for yet another summit meeting between Gorbachev and Reagan with the next president of the United States present.

So they meet on Governors Island in New

York Harbor. Reagan and Shultz thought this was going to be a moment when they sort of hand it off to George H.W. Bush, who would then continue this momentum to dealing with the Soviet Union in a constructive way. But Bush’s advisers, particularly Brent Scowcroft, his incoming national security adviser, advised him to slow down, put on the brakes, “We think that Reagan and Shultz have gone too far, too fast.” So there’s this kind of poignant moment out on Governors Island where Gorbachev comes over to Shultz and says, “How come George Bush is so standoffish? Why isn’t he participating in our conversations here?” The reason he wasn’t participating was he didn’t think he wanted to pick up where Reagan and Shultz were leaving off.

Shultz was very bitter about that for the following decades. He would come back to that to me frequently, that he didn’t understand why they wouldn’t just move forward with what he had done. I suppose it’s all speculation. Had they picked up where he left off in the spirit that he and Reagan left off and had come to provide massive foreign aid to Russia, maybe history would have turned out differently. But you know what? Let’s be realistic. You think if an American president had gone to Congress in 1989 and then later as the Soviet Union was collapsing and said, “We want to give billions of dollars to Russia,” they never would have been approved by Congress.

KENNEDY: We have another question from our audience here, and I suppose it’s an inevitable question. Did you discuss the Theranos scandal with him?

TAUBMAN: Yes, of course. It was the unavoidable topic late in George’s life, sadly so. He and I had a kind of come-to-Jesus sort of moment over this, where I had to ask him about his relationship with Elizabeth Holmes and his involvement in Theranos. It was a very tough interview. When he invited me to do his biography and gave me access to his papers, including the Seitz diary, I made very clear what my intent was. I said, “George, it’s your life, but it’s my book. I will have complete control over the contents, and you will have zero control over the contents.” He agreed to that.

So we’re seated in his conference room at Stanford University. I’m saying, “How did you get involved in Theranos? Once it became clear that Theranos was a fraudulent enterprise, that the technology was not working, and your grandson told you this, who was working at the company at your suggestion, how could you not disown Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos?”

He sat there. We went over this for almost

an hour. He would still not disown Elizabeth Holmes. To this day, I don’t understand it. The best I can do to try to explain it is I’ll be blunt about it. I think that he was intoxicated, infatuated with Elizabeth Holmes. I mean, she was in her twenties. He was in his nineties. This was not a romantic relationship, obviously, but it didn’t mean that he wasn’t infatuated with her. I think at the peak value of Theranos stock, the stock that she had given him and a few shares that he had bought was worth more than $50 million. That may have influenced his thinking.

The last reason I think he stuck by her was this sense of loyalty he had throughout his life. It began on the battlefields of World War II in the Pacific, when it’s a life-saving thing, if you don’t have the back of your colleagues, you and they may die. He carried that through his life. He remained loyal to Nixon throughout Watergate. He remained loyal to Reagan, even though Shultz knew that the Strategic Defense Initiative was technologically a fancy, couldn’t possibly be achieved. And sadly, he stood by Elizabeth Holmes when her fraud was exposed.

KENNEDY: He also, to my knowledge, at least correct me if I’m wrong, never took public voice about the candidacy of Donald Trump for the presidency.

TAUBMAN: Well, he did, but it was in a kind of anemic way. I talked to him about Trump as the fall of 2016 played out and Trump was running for president. After a while, it became clear that Shultz thought that Trump was taking over his beloved Republican Party. George Shultz remained a Republican through his life. Trump was turning it into a darker direction, but he wouldn’t speak up about it. One day I said to him, “I’m your biographer. People will read about you. I hope, for decades to come in my book. Don’t you have something you want to say about Donald Trump as he’s running for president and his anti-immigrant policies,” all the things that he stood for at the time that were abhorrent? Not to me necessarily as an American citizen, but to the Republican Party that George Shultz had been a loyal member of for his whole life. I think that sort of made an [impact] on him. So the Friday of Labor Day weekend in 2016, he and Henry Kissinger issued a statement saying they planned not to vote for either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, but would be happy to serve for either candidate, whoever was elected. And he remained largely quiet on the sidelines during the Trump presidency, even though privately he became increasingly alarmed about the Trump presidency.

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 26

Depart the U.S. on independent flights to Zurich.

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 27

ARRIVE ZURICH, SWITZERLAND

Arrive in Zurich, Switzerland, and transfer to our hotel. This evening gather for a tour orientation and welcome dinner at a local restaurant.

Hotel Europe Zurich (D)

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28

TITISEE-NEUSTADT, GERMANY

After breakfast depart for Titisee-Neustadt (New City) in the Black Forest. En route we visit the breathtaking Rhine Falls and have lunch on our own. We arrive in the late afternoon for check-in, followed by dinner at the hotel.

Walking: ~ 1.5 miles / ~2 hours, paved paths and city streets

Maritim Titisee Hotel (B,D)

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29

FREIBURG / TITISEE-NEUSTADT

Take a train to Freiburg, the capital city of the Black Forest and the most southern city in Germany. It is frequently called Germany’s ‘sustainable city’ and, taking advantage of the sunny location near the Rhine River in Baden-Württemberg, it is renowned for its ecological initiatives, vineyards, and university life. Enjoy a walking tour of the old town with a local guide followed by free time to explore on your own. Visit one of Freiburg’s numerous cafes and pastry shops and try Black Forest Cake or Freiburg Bobbele (chocolate). Return by train to Titisee-Neustadt.

Walking: ~ 2 miles / ~2 hours, city streets

Maritim Titisee Hotel (B)

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 30

BLACK FOREST HIGHLANDS

Today we hike the Heritage Trail of the Black

Forest Highlands, which also functions as an open-air museum. We begin by walking through the Löffeltal and the beautiful forest, along Rotbach Stream to the Hell Valley. Enjoy a short visit to St. Oswald Chapel which dates back to 1148. See Hofgut Sternen, where Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once stayed, and attend a demonstration of the local glass blowing. After lunch, continue hiking and pass through the Ravenna Viaduct with its impressive stone arches, and take in the romantic Ravenna Valley. We follow the trail until it takes us back to the hotel.

Walking: ~ 5 miles / ~3 hours, trail walking Maritim Titisee Hotel (B,L)

MONDAY, OCTOBER 1

FELDBERG / TITISEE-NEUSTADT

We drive to Feldberg (4’711 ft), the highest summit of the Black Forest. Walk to Feldsee, a cirque lake, created by the glaciers of the last Ice Age. It is over 100 feet deep and is the largest cirque lake in the Black Forest. Steep walls surround the lake on three sides, and rare protected alpine plants can be found on the sunny rocks. After lunch at a farmhouse, we hike to Feldberg Valley Station. Weather permitting, we enjoy a boat ride on this magical lake.

Walking: ~ 5 miles / ~3 hours, mountain trails Maritim Titisee Hotel (B,L)

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 2

ALSACE / COLMAR, FRANCE

This morning we head to Colmar, France. We travel via Kaiserstuhl, a geologically volcanic region, and Germany’s sunniest area, with a mountain range, grapevines, and a uniquely diverse flora. Enjoy a walk in the Rhine River Valley area with a local expert. Discover colorful meadows, almond trees, wild orchids, cacti, and an abundance of vineyard herbs. We then continue to Neuf-Brisach for lunch at a local restaurant. See the Neuf-Breisach Fortress, one of the last fortresses built by the brilliant engineer Sébastien Le Prestre, Lord of Vauban. At the service of Louis XIV, he created the “iron belt”, a series of fortifications capable of resisting any siege and protecting the borders

of France. After our visit, we continue to our hotel in Colmar for dinner.

Walking: ~ 3 miles / ~2.5, cobblestone streets

Le Grand Hôtel Bristol Colmar (B,L,D)

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 3

VALLÉE DE MUNSTER, LES VOSGES / COLMAR

We set off this morning for Petit Ballon (4’173 ft), a flat summit situated in the Vosges Mountains, a small mountain range separating the Munster Valley and the Lauch Valley. This is an area of woodland, pasture, wetland, farmland, and historical sites. We hike through forests and over colorful meadows, and we see the political border between Germany and France. On the top of the summit, an amazing panorama surrounds us. We enjoy lunch at a local inn, before returning to our hotel.

Walking: ~ 4-5 miles / ~3 hours, easy trails

Le Grand Hôtel Bristol Colmar (B,L,D)

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 4

COLMAR / ALSACE WINE REGION

Discover the town of Colmar during a guided tour walking down the flower-bedecked alleys, and past traditional buildings and canals. Colmar’s thousand-year-old history is visible at every corner. After the tour, enjoy some time exploring this city on your own. In the afternoon we walk through the vineyards and learn about the capital of the Alsace wine region. Enjoy a stop for a wine tasting before returning to our hotel. Dinner on your own.

Walking: ~ 2 miles / ~2 hours, paved roads

Le Grand Hôtel Bristol Colmar (B,L)

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 5

ALSACE / WWI & WWII HISTORY

Visit the Linge Memorial Museum and the site of a battlefield in WWI. As the only mountain battlefield on the western front, it holds a special significance and is a powerful place of remembrance. We then start a hike, one that takes us through history as we see war trenches and the forests of former battlefields. We make stops at local inns (ferme auberge) and enjoy lunch. This afternoon we visit the American 21st Corps Monument in Sigolsheim. This

monument honors American soldiers who sacrificed themselves during World War II helping liberate the Alsace. Return to the hotel for dinner on your own.

Walking: ~ 5 miles / ~3 hours, natural and gravel paths

Le Grand Hôtel Bristol Colmar (B,L)

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 6

STRASBOURG

Today we explore Strasbourg, the capital of the Alsace and an international hub. Enjoy a narrated boat ride on the river, and then take a guided walking tour through the vibrant streets. Learn about the European Parliament in Strasbourg and how it made Strasbourg a proud symbol of democratic values, peace, and reconciliation. Learn how modern architects connected their art to the old structures. Then enjoy free time in the city strolling the shopping mile, visiting one of the city’s excellent museums, or relaxing in a café at the river. In the late afternoon, return to Colmar for our farewell dinner at a local restaurant.

Walking: ~ 2 miles / ~2 hours, city streets

Le Grand Hôtel Bristol Colmar (B,D)

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 7

ALSACE / ZURICH

On our last day, we start with a small hike through the Alsace Plain, which encompasses an extensive number and variety of castles. Arrive to Eguisheim for lunch on your own and time to explore this town which was officially named “one of the most beautiful villages in France”. Settled in the Roman Age, it is also the hometown of Pope Leo XI (10021054). Today, its long history is also visible in the town’s onion-shaped appearance, with houses circularly surrounding the town center. We then transfer to Zurich for a free evening in this vibrant Swiss city. Dinner is on your own.

Walking: ~ 3 miles / ~2 hours, natural and gravel paths

Dorint Airport Hotel Zurich (B)

MONDAY, OCTOBER 8

ZURICH / U.S.

Depart via the hotel shuttle for independent flights home. (B)

$6,595 per person, double occupancy

Single Supplement: $1,050

Minimum 8, Maximum 16

INCLUDED:

Tour leader, local guides, and speakers; activities as specified in the itinerary; transportation throughout; airport transfers on designated group dates and times; 11 nights accommodations as specified (or similar); 11 breakfasts, 5 lunches (including some picnic lunches), 5 dinners; wine and beer with welcome and farewell events; Commonwealth Club representative with 10 or more participants; gratuities to local guides, drivers, and for all included group activities; pre-departure materials.

International airfare; gratuity to tour leader; visa and passport fees; meals not specified as included; optional outings and gratuities for those outings; alcoholic beverages beyond welcome and farewell events; travel insurance (recommended, information will be sent upon registration); items of a purely personal nature.

Participants must be in good health and able to keep up with an active group of walkers. Walks are moderate with some more strenuous segments. On average we walk 2-5 miles each day over 2-4 hours, broken up throughout the day. Travelers should be able to walk on gravel and dirt hiking trails, over uneven terrain, and use stairs without handrails. Sturdy walking/ hiking shoes are required; ankle-high shoes are recommended. One does not have to participate in every activity, but we want you to be aware of the pace.

SEPTEMBER 26 – OCTOBER 8, 2023

Phone: (415) 597-6720

Fax: (415) 597-6729

SINGLE TRAVELERS ONLY: If this is a reservation for one person, please indicate:

I plan to share accomodations with I wish to have single accomodations.

I’d like to know about possible roommates.

I am a smoker nonsmoker.

PAYMENT:

Here is my deposit of $__________ ($1,000 per person) for ____ place(s).

We require membership in the Commonwealth Club to travel with us. Please check one of the following options:

I am a current member of the Commonwealth Club.

Please use the credit card information below to sign me up or renew my membership.

I will visit commonwealthclub.org/membership to sign up for a membership.

____ Enclosed is my check (make payable to Commonwealth Club). OR ___ Charge my deposit to my ___ Visa ___ MasterCard ___ American Express

The balance is due 90 days prior to departure and must be paid by check.

CARD NUMBER

AUTHORIZED CARDHOLDER SIGNATURE

Mail completed form to: Commonwealth Club Travel, 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco, CA 94105, or fax to (415) 597-6729. For questions or to reserve by phone call (415) 597-6720

____ I / We have read the Terms and Conditions for this program and agree to them.

The Commonwealth Club (CWC) has contracted European Walking Tours to organize this tour.

RESERVATIONS: A $1,000 per person deposit, along with a completed and signed Reservation Form, will reserve a place for participants on this program. The balance of the trip is due 90 days prior to departure and must be paid by check.

ELIGIBILITY: We require membership to the Commonwealth Club to travel with us. People who live outside of the Bay Area may purchase a Worldwide membership. To learn about membership types and to purchase a membership, visit commonwealthclub.org/membership or call (415) 597-6720.

CANCELLATION AND REFUND POLICY: Notification of cancellation must be received in writing. At the time we receive your written cancellation, the following penalties will apply:

• 120 or more days to departure: Full refund of deposit

• 119-91 days to departure: $350 per person

• 90-60 days prior to departure: 50% fare

• 59-1 days to departure: 100% fare

Tour pricing is based on the minimum number of participants and can be cancelled due to low enrollment. Neither CWC nor European Walking Tours accepts liability for cancellation penalties related to domestic or international airline tickets purchased inconjunction with the tour

TRIP CANCELLATION AND INTERRUPTION INSURANCE:

We strongly advise that all travelers purchase trip cancellation and interruption insurance as coverage against a covered unforeseen emergency that may force you to cancel or leave trip while it is in progress. A brochure describing coverage will be sent to you upon receipt of your reservation.

MEDICAL INFORMATION: Participation in this program requires that you be in good health and able to walk several miles each day. The “What to Expect” outlines what is required. If you have any concerns see your doctor on the advisability of you joining this program. It is essential that persons with any medical problems and related dietary restrictions make them known to us well before departure. Proof of vaccination against COVID-19 is required of all particpants.

ITINERARY CHANGES & TRIP DELAY: Itinerary is based on information available at the time of printing and is subject to change. We reserve the right to change a program’s dates, staff, itineraries, or accommodations as conditions warrant. If a trip must be delayed, or the itinerary changed, due to bad weather, road conditions, transportation delays, airline schedules, government intervention, sickness or other contingency for which CWC or European Walking Tours or its agents cannot make provision, the cost of delays or changes is not included.

LIMITATIONS OF LIABILITY: In order to join the program, participants must complete a Participant Waiver provided by the CWC and agree to these terms: CWC and European Walking Tours its Owners, Agents, and Employees act only as the agent for any transportation carrier, hotel, ground operator, or other suppliers of services connected with this program (“other providers”), and the other providers are solely responsible and liable for providing their respective services. CWC and European Walking Tours shall not be held liable for (A) any damage to, or loss of, property or injury to, or death of, persons occasioned directly or indirectly by an act or omission of any other provider, including but not limited to any defect in any aircraft, or vehicle operated or provided by such other provider, and (B) any loss or damage due to delay, cancellation, or disruption in any manner caused by the laws, regulations, acts or failures to act, demands, orders, or interpositions of any government or any subdivision or agent thereof, or by acts of God, strikes, fire, flood, war, rebellion, terrorism, insurrection, sickness, quarantine, epidemics, pandemics, theft, or any other cause(s) beyond their control. The participant waives any claim against CWC/ European Walking Tours for any such loss, damage, injury, or death. By registering for the trip, the participant certifies that he/she does not have any mental, physical, or other condition or disability that would create a hazard for him/herself or other participants. CWC/ European Walking Tours shall not be liable for any air carrier’s cancellation penalty incurred by the purchase of a nonrefundable ticket to or from the departure city. Baggage and personal effects are at all times the sole responsibility of the traveler. Reasonable changes in the itinerary may be made where deemed advisable for the comfort and well-being of the passengers.

As a nonprofit public forum, The Commonwealth Club relies on generous contributions from individuals, corporations and foundations to support our many public programs and civic initiatives. Your support enables us to focus more of our energies and resources on meeting the challenges ahead while knowing that our day-today operations are funded.