ECHO

Roots Issue

Spring ‘23

Seed: stories about the past

Sprout: stories about the present

Spread: stories about the future

Spring ‘23

Seed: stories about the past

Sprout: stories about the present

Spread: stories about the future

At Columbia College Chicago, we focus on fostering environments where individual self-expression is celebrated, creativity is nurtured, and opportunity is abundant. You will be immersed in practicebased multidisciplinary education in the heart of a city bursting with culture–and all from day one.

Echo magazine is produced by students in the Journalism, Photojournalism and Photography programs at Columbia College Chicago. They wrote, edited, copy edited and fact-checked all the stories, shot all the photos, and designed all the pages.

Our faculty advisors are Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin (Journalism) and Julie Nauman-Mikulski (Graphic Design).

Special thanks to freelance illustrator Randy Olsen and graphic design assistant Freddy Husbands.

Photo by Liina Raud.

4 - Letter from the editors

6 - Worn out

How battle vests help music fans band together by

Justice Petersen10 - Wounds we can’t see

Acknowledging the hurt we’ve inherited by

Yoselyn Castro13 - Fear factor

Is your response a fright or a phobia? by

Aileen Carranza15 - How did we get here?

A conversation about the intrinsic ties between politics and gender by

Yoselyn Castro17 - Seven decades in Bronzeville

A walking tour through time

by Yasmin Mendiola and Karolina Dziatkowiec19 - Identity lost and found

For Korean adoptees from the 1960s, connections are crucial

by Karolina Dziatkowiec21 - Growing into myself

My experience as a neurodivergent person in a neurotypical world

by Bianca Kreusel24 - From Chicago with love

Half a century later, house music still rocks

by Yasmin Mediola28 - Talk dirty to me!

How your houseplants respond to your voice by

Aileen Carranza29 - Small space gardening

Yes, you can grow your own groceries

by Karolina Dziatkowiec32 - Lions and dolphins and polar bears, oh my!

What zoos are doing to help animals adapt into their urban habitats

by Riley Schroeder36 - Talking about roots

A salon where political conversations are always in style

by Riley Schroeder and Liina Raud39 - Eating around the world

Take your tastebuds on a trip without leaving the city by

Riley Schroeder and Karolina Dziatkowiec41 - Sending queer signals

Flagging isn’t new, but the rules have changed by

M Miller44 - Catching the beat

Fans find community through K-pop by

Aileen Carranza46 - Invisible ink

A safe space for the girls, gays and theys by

Justice Petersen49 - Anything but ketchup

Take this quiz to find out which Chicago hot dog restaurant you are by

M Miller52 - An education in empathy

A local Waldorf school reminds us about what really matters

by Liina Raud and Yoselyn Castro57 - The next generation Clubs have closed and musicians have died, but Chicago still has the blues by

M Miller60 - Wear this, not that

A guide to sustainable, affordable fashion by

Khaliyah Franklin63 - Vintage venue

A drink and a dance at Dorothy by

Dorothy Green66 - Shifting gears

The Recyclery is queering the bike repair scene, one frame at a time by

Dorothy Green69 - That’s a wrap

A crossword puzzle to thank you for reading by

M Miller

70 - The things we carry

Meet the Echo staff by

Taylor PriolaFor this issue of Echo, we chose the theme “Roots” to reflect a collection of stories that focus on our journeys and experiences through life: past, present and future. We also consider the idea of re-rooting ourselves—not letting the past define where we are destined to go.

The first section, “Seed,” features stories about the events that began to shape us, whether they occurred during our childhood or before we were even born. We also take a look at the seeds planted in our society and how they take root in both the world around us and in ourselves.

A seed begins to sprout only after it has been nurtured by its environment. With outside factors that inevitably affect us, we grow into our own kind of sprout. Often, we are expected to grow in the soil we are planted in. However, depending on how much water we were given or denied, we may choose to re-root and grow someplace else. In the second section, “Sprout,” we feature stories about what people are doing in the present to shape themselves and their identities.

As a plant grows, its roots and foliage spread. Where or how we grow and affect our communities is ultimately up to us. As we reflect on how we were planted and how we choose to mature and develop, this will affect how we spread ourselves in the future. In the last section, “Spread,” we provide stories of those who are concerned with the seeds of tomorrow.

Our roots are whatever grounds us, shapes us or shows us where we belong. They can be the communities we find ourselves in or choose for ourselves, our youth, our careers or even our niche interests. In the “Roots” issue of Echo magazine, we challenge readers to ask themselves:

“What are my roots?”

M Miller Dorothy Green Justice Petersen Photo by Liina Raud

You see them in lines outside concert venues and the crowded fields of Riot Fest, but rarely on the city streets. These iconic garments not only express the passionate outcries of the wearers, but serve as symbols of belonging, identity and heavy metal.

They are a fashion statement known as battle vests or battle jackets.

The garments are denim and covered in various patches. These patches typically display the wearer’s favorite rock bands, whether they be classic rock, punk or metal. Battle vests come in various themes and designs. They can focus on a single music genre or band — they can even be horror movie themed. Since each person has put their heart, time and energy into creating their vest, no two are the same.

Lauren Alex O’Hagan, PhD, a researcher of material culture, has written two research articles on how battle vests became a part of metal culture and what they mean to people who wear them. She says the vests of today evolved after World War II, when ex-

military members of motorcycle clubs decorated their jackets with patches of cartoon characters or pin-up models reminiscent of their old ornamented military uniforms.

“Then it sort of evolved into their motorcycle club. They would mark out which club they belong to, which geographical location they belong to,” O’Hagan says. “Then, as time went on ... they got involved in rock ‘n’ roll, later on rock [and] heavy metal. They started to then reflect their bands on their jackets.”

O’Hagan laments the lack of research into battle vests, which she attributes to scholars overlooking the significance of fashion in the metal community. “The denim, the leather, the studs ... people don’t seem to look beyond that and think: It’s not just clothing. It’s an expression of identity,” O’Hagan says.

Creating a battle vest takes many hours, but devotees consider it time well spent. Justin Stockton, the guitarist for Chicago rock band Primal Moon, has made 10 battle jackets so far, and he doubts he’s going to stop there.

Stockton made his first battle vest to show his “obsessive” love for music to the world in a way that band t-shirts couldn’t. “The original one I made ... [is] full of nearly every band I can think of,” he says. “In my mind it was like, I wear band shirts all the time, but what can I wear that has a general view of a lot of my favorite bands on it? So, it was almost a convenience thing originally.”

Rush, Foo Fighters and Slayer, among others. She was known by her peers for being the only metalhead at her Baltimore high school and learned about battle vests through Reddit.

“You want to know what I’m interested in? Just take a look at what I’m wearing,” Lowther says. “It’s like that whole expression of wearing your heart on your sleeve.”

As alternative music subcultures, and the fashion that they embody, are gaining more recognition, it is becoming more apparent that the rock music scene has changed since the ‘70s. Heavy metal fans are no longer primarily white, straight, cisgender men. There are a lot of women, people of color and LGBTQ+ people in the community now.

“I think people in the heavy metal community tend to get a bit of a raw deal where they’re sometimes associated with extreme right views, or it tends to be very heavily male oriented,” O’Hagan

Convenience soon turned into an artistic venture as Stockton began to decorate his vest with additional patches and embellishments, like studs.

“It’s almost like a sports jersey,” Stockton says, “But the thing is, with sports jerseys, usually people have one team they root for, whereas music lovers, we have many teams we root for.”

Aurora Lowther, 19, has made five battle vests. Her favorite is a black denim one completely covered in patches from Ghost,

says. “But actually, there’s been a lot of research recently that finds [the community] is more balanced. There are more women in that culture, and there are all these alternative views out there.”

While the community is a lot more diverse than it used to be, and battle vests are worn by a variety of fans, there are some drawbacks that come with the power of a battle jacket to display the wearer’s affiliations. Often, the patches aren’t just favorite bands, they’re also statements of political affiliation.

Dante “Dammit” Mercado, 21, says alternative subcultures, like punk or goth, use political imagery on battle vests for several

“You want to know what I’m interested in? Just take a look at what I’m wearing.”

- Aurora LowtherDante Mercado (left) and Aurora Lowther in their battle vests. Justin Stockton wears his Primal Moon battle vest when he performs, seen here at Subterranean.

reasons, including to scare people or to reclaim hateful symbols. However, some genuinely support the ideas behind racist and anti-semitic images. In the punk community, specifically, some people wear Nazi swastikas on their vests.

Two of the people who inspired Mercado to start making vests were metal musicians Rob Zombie and Lemmy Kilmister. The latter was known for wearing Nazi symbols, like the Iron Cross, on his vest.

“We don’t talk about that shit and it sucks. We should have to talk about that shit because it should have never happened,” Mercado says. “There are young, impressionable people who want to dress like their idols, and their idols are just oh so conveniently wearing very problematic, heinous, terrible things.”

Although many political patches are harmful, there are good ones that people wear to communicate feminist, anti-Nazi, or LGBTQ+ activism. “If you really believe in something, whether that be ‘this band fucking rocks’ or ‘cops are fucking disgusting’, wear that shit. Be proud of that shit,” Lowther says. Just be sure to put those patches on the front of the jacket, she cautions, because if someone sees those and really doesn’t agree with you and wants to confront you about it, you want to see them coming.”

While battle jackets do come with the risk of confrontation, they ultimately provide a sense of belonging. Wearers find safety and comfort when they see somebody else with a battle vest featuring familiar patches, and many

younger fans seek guidance from the older metal heads on how to fashion their own battle jackets, according to O’Hagan.

Battle jackets also serve as a means of communication or as conversation starters for a lot of metal fans. Lowther and Mercado met when they began a conversation over Lowther’s Dio patch. “If you see someone who has this specific piece of attire and you also have that specific piece of attire, we’re instantly friends,” Lowther says. “It’s because we’re both in this subgroup of weirdos.”

Whether it’s The Cramps or low-budget Ed Wood films, Mercado loves anything “alternative.” As horror movie fanatics and diehard rock fans, Mercado and Lowther both love music and film for the same reasons.

“It’s a nice way to stand out from the crowd but also being yourself,” Mercado says. “That’s alternative to me. To stand out from the crowd.”

Stockton thinks battle vests may have reached their heyday, however. He says he’s seen fewer of them at concerts in recent years. “I don’t see it as necessarily a bad thing. It just makes people that have them even more of an individual,” he says. He thinks perhaps if Gen Z TikTok influencers were to promote battle vests, they would become more mainstream.

They might also be helped by the recent spark of interest in the metal subculture from Eddie Munson from the hit show “Stranger Things.” While many metal fans were happy to see metal get some recognition, others were upset that it was suddenly being glorified when for years fans were judged for the music they listened to and the way they dressed.

“[Stranger Things] made people realize what battle jackets were,” Lowther says.

“I think [Eddie Munson] is good for the metal community of just giving it the normalization,” Mercado says. “We’re able to walk down the street now without too many people giving us the evil eye.”

In her research, O’Hagan found that there are some strict rules about battle vests. Certain bands’ patches are worn with caution, for example, and patches must fit along the seams of a vest perfectly.

But Mercado rejects such rigidity. “There are so many pretentious people that get really snobby about battle jackets,” Mercado says, “It doesn’t matter what other people like ... The only person you need to impress is you.”

Lowther agrees. “If someone calls you a poser, kick them,” she says. “The only thing that, in my opinion, qualifies someone to be a poser is if you call someone else that.”

Stockton encourages people who start working on their own battle vests to ignore how others might judge the way they look or dress.

“Don’t care what anyone else thinks ... that means you’re standing out and people notice you. Do it for yourself. Let your creativity flow,” Stockton says. “So I say to anyone that reads this –go for it. Make one. Make a million of them. Trust me, it’s a great thing to do, even if it’s just a hobby.”

“It doesn’t matter what other people like ... The only person you need to impress is you.”

- Dante “Dammit” MercadoA Primal Moon patch and a Cramps t-shirt?!

Bianca Aguirre says her mother has a “guilty hold” on her. “I can never feel anything negative towards her.”

Sometimes I’ll catch myself snapping at my siblings, getting frustrated really easily when things don’t go my way and it’ll hit me, ‘Oh shit, I’m acting like my mom right now,’” says Bianca Aguirre, 22, a psychology student at Elmhurst University.

It’s not that she doesn’t love her mother. Through tears, and often avoiding eye contact, she describes her relationship with her mother as “strenuous sometimes, emotionally.”

Aguirre’s mother was quick to anger, particularly in the way she talked to her. Aguirre found that she sometimes lost her temper, too, directing anger at people who didn’t deserve it. She decided this wasn’t a behavior she wanted to inherit.

Carolina Ayala, 21, a creative writing student at Columbia College Chicago, was the oldest of their siblings and often recruited to help their mother keep the younger ones in line. To do so, they mirrored their mother’s approach. “That’s how she keeps us in line at the store, she’ll snap at us. I tried to figure out how to snap because I wanted to snap at my siblings too,” Ayala says.

Neither Aguirre nor Ayala wanted to replicate these parenting strategies; they just found themselves doing it. Gisel Martinez, MA, a psychotherapist at Fig Tree Counseling in Chicago, says the recognition of inheriting our parents’ negative behaviors is “a painful process.”

“Oftentimes it hurts [the child] to go through that experience,” Martinez says. “It can be hurtful to name that these experiences were internalized, and you ended up mimicking or mirroring them.” This is especially true for daughters who are expected to take on parenting duties for their younger siblings.

“Oftentimes, my clients that are the eldest daughter feel like they have a lot of responsibility, or end up mimicking a lot of the roles that the mother is in,” Martinez says. “That can create another source of tension. It’s like, ‘I was as responsible as she was’ or ‘I ended up taking over because she couldn’t.’”

Both Aguirre and Ayala were raised in Mexican-American households, where family members were reluctant to talk about upsetting events and mental health issues. Kimber NicolettiMartínez, director the Multicultural Efforts to End Sexual Assault program at Purdue University, writes that Latine family relationships “are often dictated by a definite authority structure

of age, gender and role: Elder over younger, men over women, father over family.” As the head of household, the father “is the final authority on all decisions made by any of the family members,” she writes. “His power and authority is to be respected by all the family.” Respect is essential in Mexican households, and it suppresses conversations about trauma.

Intergenerational trauma doesn’t have a cemented frame, and oftentimes the trauma that we’ve inherited from our mothers comes from the trauma they’ve inherited from theirs, curating a lineage of hurt. That inherited trauma can play out in various ways. In individuals it can be seen in symptoms such as anger issues, substance abuse, emotional negligence or untethered grief. In families, it can manifest in stigmas around mental health and a hesitancy to initiate emotional conversations, extreme overprotectiveness around children and elderly family members, and mild responses to severe events.

The concept of intergenerational trauma is sometimes referred to as the “transgenerational transmission of trauma.” Past research into Holocaust survivors and their children found that both trauma and resilience can be transferred or adapted by

on both ends.”

children from their parents. Since then, researchers have studied it among other genocide survivors, like the Alevi Kurds.

Genocide isn’t the only cause of intergenerational trauma. Everyone brought into this world is influenced by the people who raised them, from the way they parent to the way they move through the world. Negative experiences from one generation can filter down to the next. They may come from a single event or an ongoing emotionally destructive environment. A field of counseling has emerged in response: trauma-informed therapy, which provides a physically and emotionally safe space to prevent re-traumatizing people during treatment.

Ayala recalls their mother’s strict obsession with keeping up a good family image. “It was directly influenced by her parents and that was directly influenced by their parents,” they say. “[My grandparents] couldn’t appear weak in the U.S.”

Refusal to talk about emotions is part of keeping up prideful appearances. Alex Diaz, 24, says nobody in her household spoke about hurt and trauma, or any other emotional topics, but she knew her mother had been through a lot.

“It can be hurtful to name that these experiences were internalized, and you ended up mimicking or mirroring those experiences.”

—Gisel Martinez

“It trickles down,” she says of her mother’s trauma. “I see that, and I recognize that, but I don’t know if I can get away from that enough to get closer to my mom. The damage has been done.”

Because she lacked emotional support growing up, Diaz says she developed an independent mentality. As soon as she could move out, she rarely saw the rest of her family. But she still regrets that her mother didn’t open up to her about her struggles. “I know that it’s not really going to change or fix anything,” she says. “I think it’s still important to me to at least know what she was like growing up and what she went through... I just wish that we could’ve had a stronger bond.”

As Diaz and Ayala became adults, they began fearing how they would be as parents. “I’m afraid of turning into my mother at that point,” Ayala says. “I’m not afraid that I’m going to have to work my ass off, because I know I will. But I’m afraid that I’m going to resent my kids for it. I’m afraid that I’m going to be mad that I have to work all the time, and then I’m going to miss their lives and I’m going to miss them growing up and having school projects and having to help each other.”

While Diaz doesn’t plan on having kids, she says that her poor relationship with her parents is a big reason for that. “I didn’t know if I wanted to have children [because I] actually want to raise someone or just to see if I can raise them better,” she says. “That’s not a real reason to have a child. I can prove that I can break the cycles without having a child.”

How many of us have found ourselves despising or critiquing our mothers for the way they parent, rather than acknowledging what made them the way they are? Despite the pain and guilt we’ve inherited from them, if we try to understand our mothers as human beings or women, instead of just mothers, that will allow us to reflect on our past, our roots, and plant new seeds when it comes to our own forms of parenting, or simply living. It’s the first step towards healing.

Martinez urges people to identify the hurt in mother/daughter relationships in order to move past them. “It’s just been a beautiful journey, to go through my own healing process and to help others go through a similar one, or to go through their own because sometimes they’re not even similar,” she says. “There’s just a lot of beauty in all of it, in the culture, in the relationship and the variety in which it can show up.”

Aguirre has worked hard to bridge that understanding. “Living in that [negativity] all the time, sometimes that’s all you can see,” she says, adding that she holds no animosity toward her mother and now works on understanding that “she’s still a person, she’s still hurting.”

Martinez applauds this approach. “Building that empathy is helpful in being able to contextualize mom, [as long as you’re] being mindful that it’s not excusing the behavior, right?” she says. “You can have empathy, you can contextualize the person, but also not condone the action.” She calls this an “inner conflict between love and hurt.”

At the end of the day, Aguirre, Ayala and Diaz are learning to acknowledge the hurt and still appreciate their mothers. “I want to showcase my mom as her still being the best mom she could be, while recognizing her flaws,” Diaz says.

When asked to describe their mothers in three words, their choices reveal this disonnance: Aguirre says “strong, funny,” and “cariñosa.”Diaz says “caring, intimidated,” and “almost unvulnerable.”Ayala says “stubborn, sensitive and bright.”

When explaining their choice of the word “bright,” Ayala says “[think of] a lamp that you can change the brightness on. Sometimes you can change the brightness to where it just illuminates your workspace, and you’re able to do whatever you need to do there. Sometimes you accidentally unplug the lamp, and it resets when you plug it back in so it’s brighter than the goddamn sun and burns your eyes. I don’t control that lamp, she does. Sometimes she’s [bright] enough to just fill the room with light, and sometimes she’s so much that my corneas burn and I have to close my eyes and look away.”

“You can have empathy but also not condone the action.”

—Gisel MartinezAlex Diaz often asks herself, “Do I even know my mom?”

Sunny Gandy doesn’t know what caused their thalassophobia, the fear of large bodies of water. “The opening scene of Finding Nemo maybe? I’m actually not sure,” they say.

Grace Bafundo loves the outdoors but is always “freaked out when in nature.” Bafundo lives with insectophobia, the fear of insects, a phobia they developed while in middle school.

Gandy and Bafundo are among the estimated 9% of American adults who live with phobias. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, phobias are defined as “intense, irrational fear of something that poses little or no actual danger” and for those who have them “even thinking about facing the feared object or situation brings on severe anxiety symptoms.”

Phobias are not caused by trauma, says Karen Cassiday, owner and managing director at Anxiety Treatment Center of Greater Chicago, who specializes in anxiety disorders, including phobias. Rather, Cassiday says the main cause of phobias is genetic—they run in families. Phobias often appear in people between the ages of seven and nine.

Phobias can induce a severe anxiety response with symptoms such as increased heart rate, sweating, shaking, gastrointestinal upset, and the desire to flee. People with phobias tend to avoid situations where they might encounter what they fear. However, Cassiday says, most people with phobias are able to recognize “the irrationality of their fear.”

“As a kid, this fear made it hard for me to swim, and often in science classes, images of the ocean made me distressed,” Gandy says. Now 19 years old, they feel anxious crossing bridges in Chicago and avoid eating fish or seafood because of its connection to their phobia.

Cassiday says many people living with phobias feel misunderstood. They can tell when others don’t understand their desire to flee when faced with a reminder of their phobia. It’s not something people can just “snap out of.”

A common misconception is that “phobias express some underlying need to avoid confrontation with life or express a way to show anger to others around you. This is incorrect,” Cassiday says. Research shows those who recover from phobias do not have “increased interpersonal problems or psychological deterioration because they no longer have their ‘crutch’ of a phobia,” she adds.

“I think the biggest misconception is that a phobia equals something you dislike,” says Bafundo. “I don’t dislike bugs. I feel full body terror.”

To ease the anxiety of their phobia, they remind themself that insects are creatures, and “not inherently creepy or dangerous.”

One of the most successful treatments for phobias is exposure therapy. “Once a phobia begins, it tends to be chronic unless it is treated with exposure-based therapy,” Cassiday says. This involves

a person gradually experiencing situations and reminders of their phobia. For example, a person might look at photos or videos, or touch objects that symbolize the phobia, until eventually they can look at the fear in-person or even touch or hold it.

“Treatment outcome research shows that specific phobias have a very high success rate when people do exposure practice, up to 90%,” Cassiday says. “It is great fun for me to work with these patients because I know they can make great progress.”

“I don’t dislike bugs. I feel full body terror.”— Grace Bafundo

Neophobia: The fear of new or unexpected things

Nomophobia: The fear of being without your cellphone

Ablutophobia: The fear of bathing

Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia: The fear of long words

Globophobia: The fear of balloons

Ergophobia: The fear of working

The political climate in which we find ourselves today has regressed back to a time where attacks on queer lives by legislation dominate broadcast news coverage. From the “Don’t Say Gay” bill that was passed by Florida’s Senate in early 2022, to the most recent law against drag performances passed in Tennessee, these are very public displays of hostility that impact people on both micro and macro levels across the country. Despite the overwhelming amount of hate in media coverage, queer communities have still consistently found a way to evolve our social discussions about all things sexuality and gender.

How did we get to this point? We sat down with Lisa Diamond, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and gender studies at the University of Utah, to discuss the evolution of public opinion. Her coverage in the vast field of gender studies includes her 2020 paper, “Gender Fluidity and Nonbinary Gender Identities Among Children and Adolescents” and her 2021 paper, “The New Genetic Evidence on SameGender Sexuality: Implications for Sexual Fluidity and Multiple Forms of Sexual Diversity.”

Something I struggled with when I tried to find professors to interview is that they fall under that gender studies umbrella, but what they really focus on is feminism. What are your thoughts on grouping the issues of nonbinary gender identities, transgender people and women into one field?

Diamond: Oh my gosh, it’s so complicated. These things are all situated in a very specific historical context. When I first joined the faculty at the University of Utah in 1999, the program was actually still called women’s studies. It was really in the ‘70s that you started to see women’s studies programs going up, following the historical developments and activism that was like, “Oh, my God, women are being left out. Let’s put women back in the picture.” Then, as that field of research grew and expanded, it became clear that this isn’t just about women.

Once you start to critically analyze gender, it’s really about everything, You can’t talk about gender without talking about race, and you can’t talk about race without talking about class. So around the time that we became “gender studies” instead of “women’s studies,” that was happening nationwide.

Over the years, a lot of us, at least in my own program, we’ve asked, “What are we doing here in gender studies?” We have a parallel program in ethnic studies and a program in disability studies. At Utah, they’re all combined together in the same school for cultural and social transformation. In other universities, they’re grouped with the humanities or other groups. Nobody knows what categories to put things in! I think the explosion in our awareness of sexual and gender fluidity and transformation has thrown yet another wrench into everything.

How have things changed since you started?

Diamond: When I took the job as a joint appointment in psychology and gender studies, my line of research in gender studies was all on sexual fluidity and non-categorical ways of thinking about sexual orientation. As I started to do that work, it

became clear that all of that applied to gender. In the earlier days of gender studies, there was a small number of us who were like, “Oh, lesbian and gay issues,” then it was like, “No, this is really an issue of sexual and gender diversity and how those things take different forms in different cultures and have different historical epochs.”

I think back in the ‘80s and ‘90s and in the early 2000s, there was a very identity-centric approach that was about underrepresented identities. Women are underrepresented relative to men. People of color are underrepresented relative to whites; lower class or first-generation students are underrepresented relative to other students; queer people are underrepresented relative to straight people. That just generated a plural operation of identities. It was LGB, and then the T, and then the Q, and then the I and then the A… and that just shows that once you open Pandora’s box to diversity, you see the world differently.

Now there’s this shift to trying to understand the whole system through which people are categorized as types of people. And that approach can be very destabilizing for individuals whose entry into gender studies was an identity-based entry. That makes it really, really difficult to say, “Oh, we’re going to have an event that is going to be for queer people,” because then you have to say, what does that mean? Who is included and who is excluded in the early days of the transition between women’s studies and gender studies?

Has there been any resistance to this change?

Diamond: Some of the people who identified as women at the time said, “It’s hard to be a woman, and I appreciated having a classroom context that was defined as being a women’s space and women’s studies because I wanted a break from the otherwise domination of men.” We talk about that a lot as a faculty and we get that. We [also] don’t want anyone’s gender to be a precondition for what we’re trying to do by destabilizing gender.

So we really want to be open to everyone. And yet we know that one of the things that happens, when you exclude those categories, is you do lose a little of the collectivity and community and emotional energy that comes when marginalized individuals are able to come together and feel their sense of community. We know that’s still important.

How does this discussion carry over into other social issues?

Diamond: Those of us who now get the bigger picture are like, “Abortion isn’t a women’s issue. Abortion is a human issue.” There’s no way you can think of abortion as a women’s issue. When you see people speaking about who’s affected by abortion legislation, there were some old style feminists who fought back and said, “Don’t talk about it as people with uteruses. These are women! Can we just talk about women?”

And yet, I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to use the word “woman” unproblematically any more. We’re in this really difficult time right now because we’re in a transitional space. There is no way anyone’s going back to totally binary ways of thinking about gender, at least among those of us who are thinking about this stuff all the time. And yet, we don’t know exactly how to study and even talk about gender in this changed landscape.

Some trans people feel threatened by the growth of nonbinary identities. They’re like, “You know how hard I’ve worked to have my gender? To have this side of the binary and to achieve it, just to have other people in my community [say] that’s reductionistic and that’s anti-liberation?” The truth is, there’s a million ways to liberate, there’s a million ways to oppress and it’s hard. We know that for folks with boots on the ground, this is the most threatening time for trans and gender diverse people I have ever witnessed in the modern age.

How does that make you feel?

Diamond: It’s almost hard to believe for someone like me who’s in my 50s. We’ve seen this kind of gradual increase in acceptance and diversity and broadening, and then to have legislators actually trying to outlaw people even saying certain words. We’re in this space where the direction of intellectual thought and political safety are inverse, which normally doesn’t happen. It’s extremely fraught and extremely challenging. I know that in my classroom, if I want to be intellectually responsible, I’ll say we’re not even sure what gender and sex really are.

You label it as a transitional period. It’s something that we’re still in, where our language and the identities that we use are still changing, and it has been changing for decades. Can you pinpoint some point in time, where this transitional period that we’re in right now kind of started?

Diamond: A lot of this can be traced to the backlash against Obama. I don’t think any of us on the progressive wing of the world anticipated just how frightening an African American president would be to a broad cross-section of Americans. I had no idea of the degree of thinly veiled panic and rage that was absolutely responsible for the Trump presidency.

I think in a lot of ways that [was a] stark power shift that the white elites suddenly felt. There’s no way to explain that other than racism. I mean, racism is America’s mother tongue.

I think the period between 2008 and 2016 was a period of a lot of retrenchment. A lot of us didn’t realize how much of that was going on under the surface until Trump got elected. The impact of our successes as progressives were fomenting a lot of opposition that has now hardened and crystallized into crack cocaine of rage.

A lot of the stuff that queer and trans youth are dealing with right now is affecting their identities and their self-expression in really negative ways. Can you speak a little on that?

Diamond: The adolescent brain is not an adult brain. One of the things we know about the period of time between age 13 and 20 is that the parts of your brain that are sensitive to what other people think of you are dialed up about as high as they can go. If you’re queer or trans or nonbinary, you’re gonna get a lot of judgment, you’re gonna get a lot of shame. Take that, combined with this incredible backlash, and it’s kind of a perfect storm.

This is partly why we’re in the single biggest mental health crisis for adolescents in this country. All the data is coming out; we’re not imagining it. It’s very, very real.

Adolescents need to be physically with their friends, not just online. They need to be with people who just like and love them just for no reason at all. We’ve lost a little of that sense. There’s this constant evaluation that everyone is feeling that is just stressing everybody out. They feel scrutinized all the time and all of that on top of questioning your gender and your sexuality is too much. Uncertainty is the most stressful thing, especially since the pandemic.

I think that a lot of it is also impacted by the fact that our education system doesn’t really touch on subjects such as sexuality and gender, and now even less than before.

Diamond: I know a lot of us at the gender studies program here have spent a lot of time talking about that. What do we need to do differently? This is a different world. The way we taught gender studies and ethnic studies and disability studies before needs to be updated. And yet, we’re not really sure how to do it. So how do we create a space where we can talk about hard stuff, and open ourselves up to feeling uncomfortable? And know the difference between feeling uncomfortable and feeling pain?

Something that I want to focus on is the evolution of the discussion around gender identity, and how that directly impacts the expression of gender identity.

Diamond: When the internet made it possible for anyone on the planet, in their own home, to see moments of gender expression around the world that they never would have seen otherwise— that was a social intervention of a magnitude that cannot be underestimated. In the old days, you only knew what was around you. Now, every kid in the world can be like, what does gender look like in Zimbabwe? What does it look like over here? What does it look like over there?

You’ve definitely touched on some points that I’ve thought about but I’ve never been able to put into words. Is there anything you want to say?

Diamond: No, [educators are] just hoping that the next generation will tell us what they want, because we want to hear it.

On a chilly evening in March, Bernard Williams, 76, rests in the armchair of the home where he grew up in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood.

“We were the third Black family to move down here,” he says of the neighborhood where he’s lived since 1948.

Williams’ family was part of the Great Migration, when millions of Black people from the South moved north and west seeking to escape Jim Crow laws and find jobs and better living conditions. His great grandmother, Hattie Latimer, moved to Chicago in 1893 and found work as a laundress.

At that time, Black people were not allowed to purchase property, but Latimer was able to buy a building in Hyde Park through a lawyer. That’s where Williams’ grandmother lived and his mother was born. His great grandfather, Frank Williams, came North from Pocahontas, Mississippi in 1904 at the age of 14. His grandfather began working in Chicago’s Union Stock Yards in 1918, one year before the Stock Yard race riots.

By the 1940s, Bronzeville had become a great Black metropolis—Chicago’s version of New York’s Harlem. Over the years, it was the home of Black luminaries including Ida B. Wells, Richard Wright, Louis Armstrong and Gwendolyn Brooks. The offices of the essential Black newspaper, the ChicagoDefender , were located in Bronzeville. It was a cultural center, featuring live music at nightclubs and theaters. Black businesses provided all the necessities residents needed. “The Black community became self sufficient because you couldn’t go downtown to shop,” Williams says.

Despite moving North for better opportunities, Black families still faced discrimination in housing and employment, which is one of the reasons they were concentrated in neighborhoods like Bronzeville.

At the time, Williams’ childhood was a time of great adventure. He recalls an abandoned mansion that he and a friend explored together. “We called it the castle,” he says. “We used to play in that mansion. It had a great view of the lake [when] you would go up to the third floor. The stairs were kind of worn out, so you was risking crashing and falling into the basement. It was reminiscent of the time when this was sort of a haven.”

During the 1950s, Williams had a paper route. Delivering the newspaper connected him to his neighbors, nearly all of whom were Black. There were only a few elderly white people left, and Williams’ mother made sure they were cared for. She and other people in the community would check on them, and Williams was sent to run errands when they needed anything from the store. He was only a young boy.

“That was the environment,” he says. “People looked out for each other. There was a sense of family.”

Williams and his friends loved to sneak down to the lake on warm summer days. “I found a spot right there on the lake where there was clear water, you could look down to the bottom and see sand,” he says. “It’s like taking a vacation from the crime of the city. You got a place where you can get fresh air.”

Persistent racism led some wealthier residents to leave for the suburbs after World War II. Williams recalls how his intelligent Black peers were often held back in school, placed in remedial classes and discouraged from continuing their education.

Not Williams, however. His mother, Hattie Kay Williams, was a social worker and activist. After the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, she worked on integrating and improving Oakenwald School in Bronzeville. She was the first Black Parent Teacher Association president at Oakenwald, and later the president of the Southeast Council PTA, comprised of more than 40 schools. She is credited with successfully fighting against sub-standard facilities at schools serving primarily Black students, and for creating a study center that became a Head Start pilot location. Head Start is a program that helps children with their early education. When it first began, they provided for lowincome communities, and they still do.

As a teenager, Williams led after-school study sessions for eighth graders to help them pass their constitution tests—a requirement to pass eighth grade. Soon, gang members were asking Williams to help them learn to read. Williams and his mother required them to give up their guns in exchange—the start of a gun purging initiative. His mother was such a beacon in the community, there is a park named after her and another local activist: Williams-Davis Park in Bronzeville.

Williams recalls the period of school integration and white flight from Bronzeville. He is now living through the neighborhood’s revitalization and the impacts on longtime residents. “I grew up in the transition from being white to Black, [and] now to multi-ethnic gentrification,” Williams says. Between 1998 and 2005, the Robert Taylor homes were demolished. It was the largest public housing project in America. This displaced many Black families and began a new era of gentrification. “When the projects were dismantled, white people found out that there was a lakefront down here and it was beautiful,” Williams recalls.

The housing project that was once known for gang violence is now being marketed as a quiet neighborhood. “White people and other people began to move from the north side and the suburbs back into the city, into the Bronzeville area and buying up the houses and hiking the [rent] of the houses,” Williams says. Today, the median price of houses sold in Bronzeville is well over $550,000, according to data from the Chicago Association of Realtors.

This has benefitted homeowners, but not renters. Williams and his mother bought two houses years ago for $24,000. His mother lived in one and also operated a food pantry from it; his sister and her family lived in the other. In her later years, Williams’ mother’s medical expenses required him to sell her house, and his sister lost the other house during the recession of 2008. Williams has lived in his current apartment for the past 25 years, but now he sits among boxes and suitcases, needing to move out after his landlord hiked the rent again.

Williams fears that Bronzeville is losing its character, and yet so much of what he loves remains. On a warm spring day, Williams walked through Bronzeville, highlighting evidence of its storied Black history. He noted the new row houses that replaced the demolished Robert Taylor Homes. He pointed out the Chicago Defender building where Black journalists created the most influential African American newspaper of the mid-20th century. He stopped to admire the Ida B. Wells home and monument, and the Southside Community Art Center which was once owned by poet, artist and writer Margaret Taylor-Burroughs—a space where Black artists could show their work.

Williams has left his mark on this neighborhood, too. He helped the Army Corps of Engineers survey 41st Street Beach— his childhood hangout spot. He designed part of a sculpture on the lakefront that commemorates Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman to fly an airplane.

And the neighborhood as left an indelible mark on him. He lived in New York during college, and lived in Harlem, but Bronzeville brought him back. “I prefer Chicago to New York,” he says. “The real charm of where we are, in a hidden gem along the lakefront.”

Mark Hagland, 63, was adopted as an infant from South Korea by his Norwegian and German-American adoptive parents. Suddenly the dark-haired, darkeyed infant was part of a blue-eyed, English-speaking family in Milwaukee, Wisc., surrounded by people who looked nothing like him.

The Korean War ended in 1953, and Seoul was flattened. By 1960, there were hundreds of thousands of children who were orphaned or abandoned by desperately poor parents who wandered the streets picking food out of garbage cans.

“The vast majority of children who ended up at orphanages were abandoned children, and that was undoubtedly a result of the rapid poverty and also the rapid number of mixed race children resulting from the military occupation,” says documentary filmmaker Glenn Morey, 63, who was adopted from Seoul when he was six months old. The U.S. passed special legislation to sidestep the Asian immigration limits still in place from the early 20th century. South Korea and the U.S. set a precedent for inter-country and transracial adoptions. According to the South Korean Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs, more than 110,000 children from Korea were adopted into America between 1953 and 2008. That’s ten times the number of Korean adoptees in France, and the next highest country.

Adoptions out of South Korea were popularized by churches that persuaded religious couples into believing that this was a great opportunity to “save” children. “Finding the perfect healthy white infant was very difficult, even in 1960,” Hagland says. “But this Norwegian missionary told my father that people were adopting from South Korea.” The missionary went to churches across the country with what Morey calls a “kind of road show” promoting adoptions as an opportunity “to save the lives and

souls of these children.” They didn’t address how to nurture children experiencing abandonment trauma, and there weren’t many resources for adoptive parents on raising children from other cultures at the time. “There were no resources of any kind,” Hagland says. “There was no literature on adoption.”

As he grew older and realized he was from another place, he sought information at the library. “I remember as a child reading the book, The Land and People of Korea. That was better than nothing, but it was close to nothing,” he says.

Morey says the only time there was any sort of post-adoption interaction with the agencies that placed South Korean children in American homes was if things were going badly. Hagland’s adoptive parents sought to do better. They joined EastWest Circle, a group that connected adoptive couples with one another. But that didn’t provide any support for the children.

Growing up, physical self image was a big issue for Hagland. He was surrounded by white people and felt marginalized. Looking back, he says he needed his adoptive parents to provide a cultural mirror, but that wasn’t something they knew or knew how to do at the time.

“I say that I’m Korean and I’m American. Because if you say Korean-American, people will instantly assume you have strong connections with KoreanAmerican families.”

—Mark Hagland

Hagland didn’t experience a diverse environment until he attended Northwestern University in Evanston. “You feel attracted and you want to be a part of it, but inside you know you’re completely white. So you have to find your identity as a person,” he says. For that reason, he never called himself Korean- American. “I say that I’m Korean and I’m American because if you say Korean-American, people will instantly assume you have strong connections with Korean-American families,” he says. He calls this a “narrative burden,” which is when someone who doesn’t fit in is asked “what they are.”

Hagland has visited South Korea three times, not to meet his birth parents but to connect to his roots. Most adoptions from South Korea were closed, meaning the adoptee doesn’t know who their biological parents are. “During that time, again, the first wave of international adoption, no one even thought we would ever want to go back,” Hagland says.

Hagland says East Asian societies have a high barrier culture: “There’s the tribe and not the tribe.” When they see his Korean face, they expect him to speak flawless Korean, be connected to the culture and follow their customs, but that is not what Hagland grew up with. When he explains his identity to Koreans in Korea, they typically feel ashamed of their past and apologize. These interactions are exhausting for him. “I tell people, it was as though I were a Martian in a spaceship that had happened upon a convention of Martians,” he says.

Hagland didn’t truly find community until he started a Facebook group for transracial adoptees, which he moderates in English, Scandinavian and Spanish. He has built a community full of people with complex and multi-faceted identities which he can identify with. Years of getting to know friends of color and piecing his identity together have been transformational for him. He describes his support system as different pieces of a single quilt, all relating to different parts of his identity.

The journey has been difficult, but no more than if he hadn’t been adopted. “Growing up in an institutional environment is terribly unhealthy,” Morey says. It’s also not enough for a child to be adopted into a loving home when no one in their family, neighborhood or schools look like them and they have no way to connect to their roots. Today, adoption agencies support parents seeking to connect their international or interracial children to the communities they were born into, and many parents know to seek out opportunities to help their adopted children connect to others who share their origins. The National Council for Adoption encourages parents to learn about the lifelong impacts of adoption, and not to assume “that love and nurture will undo all past trauma or that a child adopted as an infant will not have experienced any trauma.” They also urge parents to “stay connected with other adoptive families and agencies that support adoptive families upon return to the U.S. Far from being over, the journey to becoming a family is just beginning.”

“There isn’t nearly enough done in terms of adoptive parents and adoption services oversight to ensure that good practices are followed,” Morey says. But more awareness can help change that for the bettere

“I remember as a child reading the book, The Land and People of Korea. That was better than nothing, but it was close to nothing.”

—Mark Hagland

But I was too different. My peers made my life difficult through constant bullying, and my teachers had no training on how to support autistic children. This, in turn, spiraled into regularly being sent out of class, and my mother showing up at school to support me after unsuccessfully arguing for me to receive extra help or aid.

I was in elementary school from 2006-2011, and although my memory is hazy, I do remember being pulled out of my classroom to see a speech therapist, a social worker and other specialists whose titles and names I can’t remember. Being pulled out of my classes caused me to be an outcast and, for awhile, I knew that people were afraid of me or laughing about me.

By Bianca Kreusel Photos from the Kreusel familyWhenI was born, my mother said I did not immediately cry. Instead, I looked around the room full of doctors and midwives with awe and wonder. As a baby, I never liked to be cuddled, and when I was held, I wanted to face the world and look around.

As I grew older, I never understood social cues or how people were able to naturally make friends and keep them. I was always “that” kid. Someone who got angry easily and had violent outbursts, someone who never had many friends, and someone who was prone to the ruthless torment of my peers.

“I knew there was something. I just didn’t know what it was because autism [awareness] was just starting,” my mother, Kathleen “Kathy” Kreusel says.

I was officially diagnosed at the age of six with a now outdated diagnosis: Asperger’s Syndrome. This term is no longer used because of the controversy around the man who coined the term and because doctors came to understand that Asperger’s and autism are one the same. My mom explained to me, a young child who didn’t really understand anything about herself, that it meant I was special. I was different.

Outside of school, I was also put into occupational therapy, social therapy, and speech therapy. Not all of it was covered by insurance, and my parents were supporting the family on one income. “[Your] dad was working 16 hours a day, seven days a week,” my mom says.

But not being diagnosed would have been far worse. Even now, many children aren’t diagnosed—or aren’t diagnosed early— which denies them many essential accommodations, therapies and resources that I was able to get. This is especially true for many autistic children of color. As recently as 2020, research shows that nearly 25% of children are undiagnosed, but the numbers are 1.7 times higher among Black children and 1.6 times higher among Latinx children than they are among white children.

I was among the fortunate ones, and the therapies I received were helpful. I was able to learn to identify emotions. According to my mom, I was never in applied behavioral analysis, or ABA therapy, a controversial treatment that some claim forces many autistic children and individuals to “mask”—a term used when autistic people suppress their natural behaviors because they aren’t considered “normal.” Critics of ABA therapy say it “forces the autism” out of autistic children because they don’t behave the same way as their neurotypical peers. “It might be teaching clients to kind of fit in or hide their neurodivergence rather than celebrating some of their strengths or building on those strengths,” says Nicole

Francen Schmitt, a clinical psychologist who sometimes works with ABA therapists.

Still, I did learn to mask. I felt myself conditioned to always act “normal” and began to feel embarrassed about having autism. Even now, as I am about to graduate college, I still sometimes struggle to understand social cues.

Though my mother will claim that I was the one who did all the work and fighting when I was growing up, she was the real hero in my life. Countless times, my mom went to school to fight for necessary accommodations. When my elementary school, my peers and everyone else felt like an enemy, I always knew that my mother was on my side. I am so lucky to have her.

I moved to Illinois when I was 13. As a child with autism, I had an extremely difficult time adjusting to a new environment with new kids and teachers. But things got significantly better through middle school and into high school. I no longer had the baggage from my time in elementary school. I could reshape myself into someone I had always wanted to be. I began to mirror my peers, copying how they reacted to what their friends told them. I also accepted any person who wanted to be my friend, without

understanding whether or not they were truly good friends. It was exhausting constantly trying to act “normal” at school.

In high school, I tried to erase the word “autism” from my identity. I began blocking out the memories that had followed me from elementary school, refusing to think about those experiences. I had internalized the ableist voice in my head that said I should be ashamed and embarrassed to even admit that I had autism. I treated my autism as a dirty, mortifying secret that must never get out. I did my best to mask at school and in front of my peers. I still do.

But something changed. I began making new friends, and although I still saw the school social workers and had accommodations, I started noticing how many other kids also had accommodations. It was almost not weird to test in other rooms or have extended testing time. The way it was normalized and accepted in high school was a completely new experience for me.

I still struggled to accept the fact that I have autism. Throughout high school, I was torn between how much I wanted to reveal to my friends and how much I felt I should keep to myself. I feared that if my new friends found out too much about me, they

would push me away or treat me differently. Out of cautiousness, I just never mentioned it.

In my junior year of high school, I finally told my current best friend. I had just put the kids I was babysitting to bed. I was nervous, but she accepted me wholeheartedly and didn’t treat me any differently because she knew. It was a small moment in my life that suggested maybe, just maybe, I could surround myself with people who would accept me for who I am. All of me.

I didn’t truly get over my fears of rejection until my junior year of college. Columbia College, which has a lot of accepting people and embraces differences, helped with this a lot. As I went through my classes, I met all kinds of neurodivergent people, and I learned to advocate for myself. Slowly, I began to share who I really am with my peers.

Even now, as I get ready to graduate college and go out into the working world—a world made for neurotypical workers—I hesitate to speak about being autistic, and I find myself masking at my job and internship. I know, however, that the world is becoming more accepting of those with disabilities. That helps me and others like me to make room for self acceptance.

“I think, working with a therapist about self love and self acceptance, and working through how to talk to [your] peers or other people about your autism and what it’s like for you, is really helpful,” Schmitt says, “I think, as a society, we need to keep working towards understanding and accepting neurodivergence, recognizing how common it is and how it really enriches our human experience.”

Though I still struggle with fully accepting that part of myself, I know one of the biggest steps I can take is sharing my experience. Everyone’s experience with autism is valid and unique. I sincerely hope that others with autism also find the confidence to share their experiences, both the bad and good, and gain strength to take on life head first.

Mario “Liv It Up” Luna, 56, remembers how he fell in love with DJing back in 1982. He was born and raised in Pilsen, where summer days were filled with block parties. A DJ would set up in the middle of the street with speakers and turntables while everybody danced.

“I just seen the DJs mix vinyl from record to record and it was a skill that not everybody could do it. You could try to do it. But if you weren’t good enough, you could tell you weren’t good enough as far as blending,” Luna says. DJs used two turntables, mixing and blending the records on each side and creating smooth transitions.

Luna was a witness to and a participant in the birth of house music, which goes back to underground clubs in Chicago and New York in the late 1970s. In Chicago, Black, Latino and LGBTQ+ music and dance fans gathered at The Warehouse, the nightclub that opened in 1977 and popularized house music. Chicago was also home to “Disco Demolition Night,” an event in 1979 where many people blew up disco records. But while disco lost its mainstream appeal, DJs across cities kept playing it in the underground scene.

An early Warehouse DJ was Frankie Knuckles, who changed tempos and layered songs with percussion. He played underground disco, soul and European electronic disco, and his experimental sound influenced other DJs and producers. It was a safe space for the LBGTQ+ community.

Lori Branch, a DJ, stepped in the Warehouse and was inspired by Frankie Knuckles. The music was so loud, you could hear it outside and feel the bass in the concrete. For her, The Warehouse is a special place.

“This was an important building in my story because it’s where I sort of came out as a bisexual person. I found safety, community and friends there,” Branch told Sasha-Ann Simons, host of the WBEZ show “Reset.”

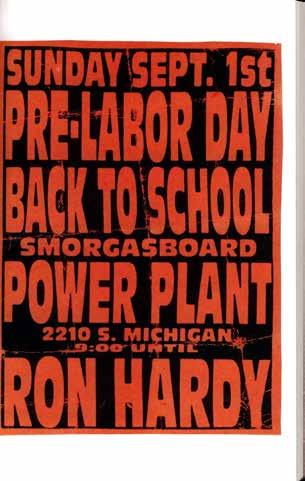

In 1982, Knuckles opened his own club, Power Plant, where he was known for using beat drums. His 1987 release, “Your Love” under Trax Records, spread like wildfire across Chicago, expanding house music’s reach beyond the clubs.

Ron Hardy is another influential DJ of the time. His fastpaced, high-pitched experimental beats blared out of speakers at

Luna is a self-taught DJ. He owned the record “Live It Up” by the Time Bandits, and was inspired by the name. He remember DJs throwing the song into their mixes.

He also threw it into his name. Mario ‘Liv It Up,’ that sounds pretty cool! Nobody has that name,” Luna says. “Back in the ‘80s it was more creative. You had to be more creative as far as your name—it had to be catchy. You had to have a cool name to get recognized,” Luna says.

Luna recorded himself DJing and handed out cassette mixtapes everywhere he could. They quickly spread throughout Pilsen, helping him connect with other DJs. He joined the DJ group Dimensional Sounds in 1987. He was recruited by the Ultimate Party Crew the next year, when they hosted their first party. “I was like ‘Wow, check this out.’ My eyes were

House parties were smoky, hot, crowded and loud, with a bass you could feel throughout your body. Each crew wore jackets with their own emblems. They also tried to distinguish their sounds from one another.

Luna found inspiration from the Columbia College Chicago radio station WCRX, which played underground tracks he didn’t hear elsewhere. “You wanted to buy music that nobody else was playing, or if you play a record, they never played the other side,” he says. “You always wanted to have a certain style from the other guys.”

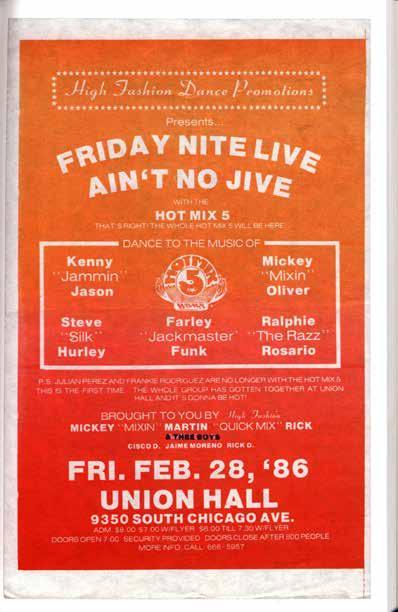

He also listened to The Hot Mix 5 on WBMX, where a team of DJs would mix songs every Friday night. Their high-energy mixes included rare records. He wasn’t the only one listening in and getting inspired. Houz’Mon, then known as Slick Master Rick, 56, from Chicago’s West Side, was also tuning in, the joy and excitement rushing through his body as he heard the mixes. “It was like a treat to me. I thought to myself if these guys could do it, I could do it,” he says.

A friend, who was a DJ, took Houz’Mon to The Factory, a club on west Madison Street, where he was invited to spin some records. He didn’t do well, but an experienced DJ, “Great the Master,” saw potential in him and gave him another chance to come back under one condition: he had to practice.

“I practiced every single day, right after school, and went straight to his place to practice,” he says. He returned and dominated the turntables. “The people would let you know if you did not do so well, they would just get off the dance floor,” he says.

Houz’Mon’s ghetto house mixes included synthesizers and drum machines. This style of house is more raw, with repetitive sampled vocals. The bass is heavy and the beats are fast, with highly danceable, dirty lyrics. He eventually landed a record deal at DJ International Records, a Chicago house-music label, and released “Brothers and Sisters House on 13th Street.”

“I was there at the right time, at the right moment,” he says. In 1993, he came up with his own label, Beat Boy’s Records, where he released “Fear Tha World” under his new name, Houz’Mon.

Meanwhile, house music was gaining popularity in neighborhoods on the southwest and South Side, where local DJs made it their own. “Latinos were making a lot of house music but with a salsa beat, with the timbales,” Luna says. “I think that made the Latino house sound different from the other artists because you had that Latin flavor in there.”

These days, Luna still finds comfort in music. He goes up to his man cave where he has his DJ equipment and his 15 crates of records and puts his headphones on and lets the music take him away. “You just shut the world off and you go into your own world as far as music and you get into it. You forget about everybody, forget about all your problems, you’re in your own zone.”

House music, he says, is timeless music. “It’s something about it that is never going to go away. It’s never going to die out. It’s got that one certain sound to it that people like to this day.”

Plants react and like the sound of our voices. Although plants don't understand our words, scientists in the field of phytoacoustics have found that plants detect and respond to sound.

According to “Sound perception in plants,” a 2019 research article in the journal Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, plants respond to sound by changes in their genes, pathogens and nectar.

But it doesn't take a scientific study to find that people like talking to their plants.

Taryn Callion often apologizes to her plants when she forgets to water them. "I think they look greener, but it could be me deluding myself," she says.

Natalia Boria credits the “good vibe” in her grandmother’s house to the houseplants there and the love given to them. Her grandmother often asks them whether they are thirsty. “I just know her plants were always so bright and uplifting,” Boria says. But don’t take it from them. We interviewed three plants to see what they thought about the words their people said to them. The illustration above provides their answers.

By Karolina Dziatkowiec

Photos by Taylor Priola

By Karolina Dziatkowiec

Photos by Taylor Priola

Even if you live in a small apartment, it’s possible to grow some of the vegetables you love. The key is hydroponics, a gardening method that doesn’t require soil. It won’t replace your trip to the grocery store, but you’ll have the pleasure of growing some of your own herbs and vegetables.

Andy McGhee, aquaponics specialist at Windy City Harvest, suggests beginner-friendly veggies like herbs and greens, including chard, kale, arugula, watercress, bok choy and looseleaf lettuce. “What most people would want to do is have a little variety,” says Marius Berman, the manager at Chicago Roots Hydroponics and Organics.

Although you can purchase a complete hydroponic system, you’ll save money by creating your own set-up. “Indoors, you need to have light and you need to have a space for your plants,” Berman says. “You got to have water, you got to have airflow no matter what.”

“The more time you spend with them and the less you overthink it, the better your plants will grow.”

—Marius Berman

Here’s what you’ll need:

• Seeds

• Rockwool

• Tupperware or reused container

• Expanded clay (aka leca)

• One three-inch net cup per plant

• Ten to 15 gallon tote with lid

• An aeration stone with air pump

• Clear tubing

• Drill with three-inch hole dozer attachment

• LED grow light

• Botanicare Pure Blend Pro Grow nutrient solution

Begin with germination:

1. Soak the rockwool in water for 24 hours.

2. Use a toothpick to puncture a hole in the cube.

3. Insert two seeds into one rockwool cube.

4. Put the rockwool cubes containing the seeds into a food container and close the lid.

5. Let the seeds germinate in a dark place.

6. After a few days to a week, the seeds should have sprouted.

Build the reservoir:

1. Prepare the reservoir by using your hole dozer to make holes five inches apart in the tote’s lid—one for each plant.

2. Create a hole on the side of the reservoir above the water line, big enough for the clear tubing to fit through.

3. Rinse the reservoir, then fill it with water and set it in your new hydroponic area. Let the water sit for 24 hours.

4. After 24 hours, mix the nutrient blend.

5. Thread the clear tubing through the hole on the side of the reservoir. Attach the air pump to the tubing on the outside of the reservoir and the aeration stone on the other end. Drop the stone in, elevate the air pump and plug it in.

6. Cover the tote with the lid and hang or attach your LED lighting above the reservoir so it's ready to use when the seedlings sprout.

Plant in the reservoir:

1. As soon as you see the seeds sprouting in the container, it’s time to move them.

2. Fill the bottom of the net cup with the expanded clay pebbles and place the rockwool with the seedling on top. Fill the rest of the cup with the pebbles, until the rockwool isn’t visible.

3. Place the net cup in the holes you drilled into the lid of the reservoir.

4. Turn the LED grow light on and wait for the plants to grow. Once the reservoir is up and running, it’s important to maintain it. “Usually after about 14 to 21 days, you’re going to want to go in there, remove the lid and dump that water out, clean the reservoir and then replace it with a fresh batch of nutrients and water,” Berman says. Let your water sit for 24 hours to naturally dechlorinate before mixing your nutrients. Checking the Ph balance of your water daily is optimal for successful vegetable growth. McGhee also recommends “ensuring there is enough airflow, staying on top of pests and nutrient level management.”

As your vegetables start growing, watch for evidence they’re getting too many or too few nutrients. “If you’re feeding them too much, you’ll have burnt edges or the leaves will be dark green and they won’t be growing very fast,” Berman says. “If they’re nutrient deficient, there’ll be lime green on the bottom leaves and it will kind of work its way up.” If that’s the case, add nitrogen. But don’t panic. “The more time you spend with them and the less you overthink it, the better your plants will grow,” Berman says.

By Karolina Dziatkowiec

Photos by Liina Raud

By Karolina Dziatkowiec

Photos by Liina Raud

The Garfield Produce Company grows micro greens and petite greens hydroponically, then distributes them to restaurants and stores including WhatsGood, Urban Canopy and Village Farmstand.

The hydroponics nutrient film technique (NFT) uses pumps to raise water to the towers of micro and petite greens. They use a curated mix of nutrients to feed the plants.

When I was five years old, my kindergarten class went on a field trip to the Milwaukee Zoo. After what seemed like a long bus ride, we entered the front gates and began searching for the animals that corresponded to the pictures inside our cubbies (mine was a giraffe). I was awestruck seeing it in person. A real life giraffe! What more could a kid want?

Since then, I have grown more wary of zoos. I find myself asking: Is there enough space for the animals? Are they becoming desensitized to their surroundings and losing their natural instincts? In general, are they OK?

But I am aware that many of these animals have nowhere else to be. Natural wildlife is vanishing due to human encroachment and climate change. Lions used to live on a wide range of thick brush in open plains in Africa’s savanna. Now, they live on only 8% of their previous range, according to the World Wildlife Foundation. Dolphins are exposed to both man-made and natural threats in the ocean, including fishing gear left in the water, bio-toxins and oil spills, which cause habitat degradation. Additionally, climate change is melting the Arctic sea ice that polar bears depend on to hunt, live, breed and create dens.

For these reasons, very few of the animals at Brookfield Zoo near Chicago are able to return to the wild. In recent years, only the golden lion tamarins and Mexican gray wolves were reintroduced. “The unfortunate news is that a lot of those reintroduction programs, aren’t happening anymore,” says Tim Sullivan, the zoo’s director of behavioral husbandry.

One of the main reasons is habitat loss. “There’s ... very little safe habitat to reintroduce them to, and actually, reintroducing animals to what remains there is unsafe for them,” Sullivan says. “So the unfortunate thing is, it’s not about getting animals back to the wild. It’s about protecting the animals that are there and trying to protect the remaining habitat.”

So the zoo is their home — now and forever.

Staff at Brookfield Zoo try to make animals’ zoo lives reminiscent of the wild. Sullivan says the main way they do this is through monitoring behavioral repertoires.

The key is to replicate the natural behaviors they experience in the wild. “Are they sleeping as much as they do in the wild? Are they active and foraging as much as [they] would in the wild? If there’s discrepancies between that, we try and use original

strategies to bring out that behavior if it’s not being exhibited. Or if it’s not in the right proportion,” Sullivan says.

Ultimately, the zoo can’t replicate everything about the wild, and it doesn’t need to. “There’s not a drought in Brookfield Zoo. There’s never a food shortage at Brookfield Zoo,” Sullivan says. “So they don’t have those particular demands on their body. But we do want to make sure that because we provide all their resources that they need, we do so in a way that gives them their jobs, keeps their skills up.”

To maintain their skills, Lance Miller, vice president of conservation science and animal welfare research at the Chicago Zoological Society and Brookfield Zoo, says each animal is provided the following: 10 to 20 minutes of daily enrichment time (when their brains are stimulated by their surroundings), appropriate social circles, specific diets, and thermally regulated habitats designed with natural environments in mind. There’s also a veterinary service providing vaccines and check-ups.

Although the animals at Brookfield Zoo are well taken care of, Sullivan says some guests believe they are not happy. He cautions visitors against making anthropomorphic assumptions about how “happy” animals are in their habitats. “You’ll hear people say, ‘Oh that animal is happier, they look bored, they’re sad.’ But they’re basically overlaying human characteristics and expectations on animals that are completely different than humans,” he says.

Many zoo animals are desensitized to humans because they are a constant presence. Not the dolphins, however. “The dolphins will be swimming by under water and all the sudden, they’ll just stop for some reason and get really interested in a person wearing a certain thing or doing a certain thing,” Sullivan says. “To me, that’s when I know they’re still paying attention to the guests.”

The zoo’s behavioral research manager monitors whether visitors are affecting animals in a negative way. “In general, the guests are not a welfare concern for the animals. Usually, when you see them interested in the guest, it’s because they’re interested in a good way,” Sullivan says.

Here’s how Brookfield Zoo is maintaining their African lions, bottlenose dolphins and polar bears to mimic life in the wild, according to Miller and Sullivan:

“It’s about protecting the animals that are there and trying to protect the remaining habitat.”

—Tim Sullivan

Habitat: In their legacy habitat, built in the 1930s, there is a heated cave for basking in the winter, as well as a chilled, shaded area for the summer heat. A pool simulates watering holes, which lions drink from and play in. Large, heated rocks allow the lions to monitor the land while staying warm.

Activities: Bungee poles with meat attached to the end simulate prey. At night, when it’s easier to sneak up on animals, the bungee cord allows the animals to fight and hunt as they would in the wild. Zookeepers also anoint the exhibit and toys with smells that draw out a rubbing behavior, where lions brush against the toys to get the smells on them.

Socialization: Miller says lions in the wild are very social in their large prides. When they come to an age where they are kicked out, they form bachelor groups. At Brookfield Zoo, these groups consist of two brothers.

Diet: Their diet consists of meat every day, bones once a week and a whole carcass every other week. Pulling meat off the bones and licking them using papillae (minute hooks on their tongues) keeps the lions’ mouths healthy.

Health: The lions are given complete CT scans every three years to assess their organs. They also get regular dental cleanings, physical exams and vaccines.

Habitat: Dolphins swim freely in a temperature and salinitycontrolled water tank that simulates the ocean. Right now, the Seven Seas dolphin arena is under construction—a noisy process for creatures with extremely sensitive hearing—so they’ve been temporarily transferred to the Minnesota Zoo.