at

© The Capsule 2025 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher by copyright law. For permission requests, contact: thecapsulejournalusf@gmail.com.

Connect with us on Instagram: @thecapsule_usf

Dear Reader,

It is with great excitement and pride that I welcome you to The Capsule—Volume 2!

Two years ago, the idea of this journal was nothing more than a dream. Today, it stands as a vibrant and growing platform for creative expression, run entirely by students of the University of South Florida. What began with a vision to provide authors and artists the opportunity to share their reflections on public health, personal health, and healthcare through prose, poetry, and visual art has evolved into something far beyond what I could have imagined.

This past year has been a whirlwind of growth and recognition for The Capsule. We’ve been featured in multiple USF news articles, including those by the College of Arts and Sciences and USF Honors. Additionally, some members of Volume 1’s editing team and contributors had the privilege of speaking about our journey on the USF Honor Roll Podcast. Even more exciting, several of our executive board members traveled to Philadelphia early April to present at the Annual Health Humanities Consortium, outlining the interdisciplinary collaboration between the arts and sciences through The Capsule and the implications of engaging with the principles of narrative medicine early in one’s education.

These milestones would not have been possible without the unwavering dedication of the executive board and the support of our incredible contributors. The diversity of our submissions—from age, to major, to background—continues to enrich the journal, and I’m constantly in awe of how far we’ve come. This year, The Capsule has surpassed its humble beginnings and continues to thrive in ways I could only dream of.

I want to extend a heartfelt thank you to the executive board for your hard work, passion, and commitment. Your efforts have helped set an extraordinary standard for the future of this journal, and I am deeply grateful for everything you’ve done. As Editor-in-Chief, it’s been an honor to witness The Capsule grow and evolve, and I encourage all our contributors and readers to keep creating, sharing, and advocating for the power of art and community.

I hope you enjoy Volume 2 of The Capsule. May the stories and artworks you encounter inspire, challenge, and connect you, just as they have done for all of us involved.

Sincerely,

Serena Bhaskar Founder and Editor-in-Chief

Special thanks to Dr. Lindy Davidson, Professor Elizabeth Kicak, Dhenu Senthil, and Priya Desai.

USF Sparks Magazine, USF Thread Magazine, USF Creative Writing Club

tic, tic, tic | Savannah Barker | Poetry

Guided by Service, Changed by Experience | Amrita Nayak | Nonfiction

Interlinking Rates of Pregnancy and STIs in Youth with Culture and Education | Sandra Aitcheikh | Article On Malaria & the American Dream | Serena Lozandi | Poetry |

Overlooked | Jemma Parsons | Multimedia |

Diagnosis | Noah Bennett | Nonfiction |

The Enemy Within | Smyrna Davalath | Poetry

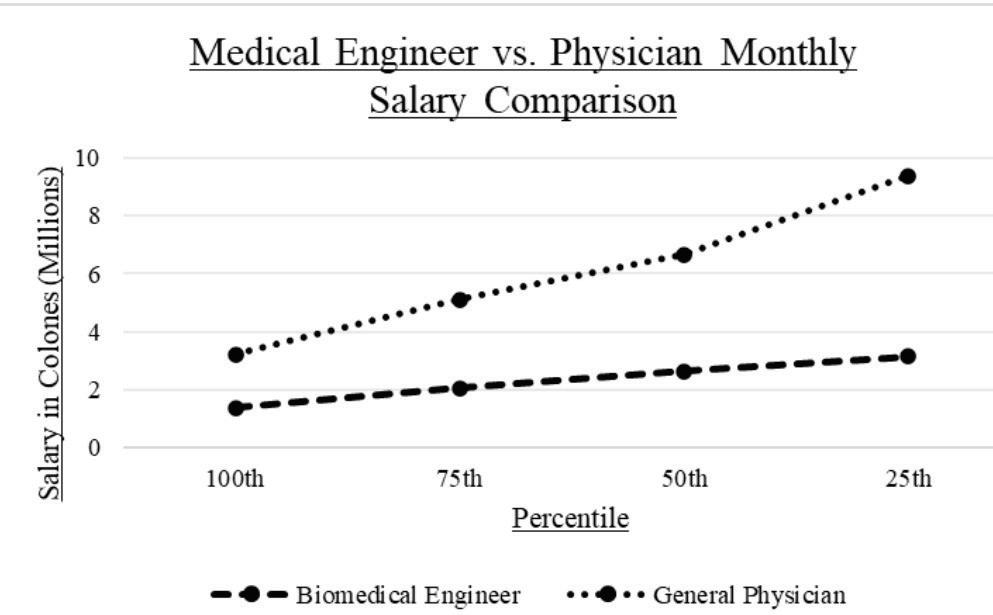

Challenges in Costa Rica’s Healthcare System: The Effects of Resource Misallocation on Access and Universal Care | Anthony Valverde | Article

What Remains of You | Olivia Pinilla | Poetry

Prescription Grin | Genevieve Carcano | Poetry

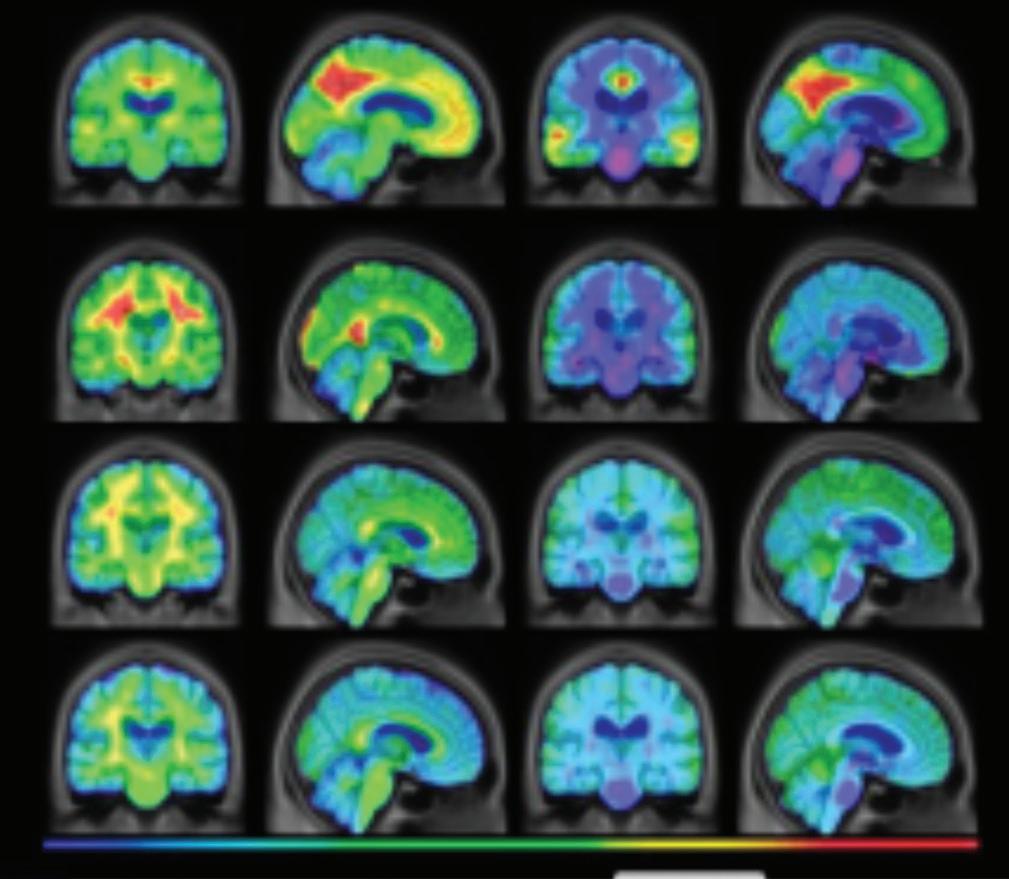

The Female Brain and Alzheimer’s: Exploring the Increased Vulnerability | Gabrielle Luisa Dotti | Article

diag[no]sis | Gabriella Davis | Poetry |

Savannah Barker

Currents charge the follicle passageways. Dead end descends.

Absorbed by the minds of the strange and unkind, mankind notified.

An accidental brush on the left leads to a purposeful thwack on the right, until it feels right. Tame the beast with the curls to keep her silent.

Weapons came from all ways.

But with a swift strike to the side and a strategic method of strangulation, a rubber hair band: victor and ultimate tranquilizer.

Never allow a single strand to fall from its place! For secrets must remain in place.

People often seek wisdom in books or moments of introspection. I, however, sought mine somewhere less conventional–in a tutoring program aimed at supporting Afgan and Ukranian refugees. What began as a high school community service requirement became a journey that would profoundly shape my understanding of narrative health and healing. This experience goes past simply educating, but a story of health and the importance of cultural sensitivity to holistic healing.

After a brief orientation, I was assigned to Gulsoom, an eighth-grade girl from Afghanistan who needed a friend more than immediate progress on the course curriculum. I focused on being a confidant, sharing my own story, initiating conversations, and letting her guide them in the direction she felt comfortable with. I recognized sharing her narrative as an essential aspect of healing and wanted her to see that her story mattered and she was understood. By our third session, Gulsoom voiced her struggles fitting in and forming connections at her new school, issues that had significantly impacted her self-esteem. Having to navigate an unfamiliar culture, language barriers, and differing social norms in order to feel included left her lost and uneasy. Listening to her, I saw how this drastic change and cultural displacement had impacted her mental health, making her feel overwhelmed, anxious, and isolated.

Inspired by a spiritual development class I’d attended, I incorporated activities to boost self-confidence into each tutoring session. Together, we practiced positive affirmations and concentrated on identifying and building on our strengths. Within just a few months, I witnessed a remarkable transformation in Gulsoom. She became more confident at school, made new friends, and her enthusiasm for learning grew steadily. Witnessing Gulsoom’s progress taught me that the need to belong is universal, and it only takes a bit of compassion and active listening to improve emotional well-being. Gulsoom’s willingness to share her story reminded me of how storytelling itself can be healing; the act of listening deeply to personal experiences is as vital as any medical intervention. Creating safe spaces to share experiences reminds individuals that they are not alone in their struggles. Unexpectedly, I found my own confidence levels rising, with the positive affirmations actively reflecting in my own life. As I encouraged and uplifted others, I began to internalize those same messages and realized that I needed to hear these positive affirmations too.

This symbiotic exchange of positivity showed me the power of encouragement and personal development. My next semester in the program introduced me to Neelab. At our first meeting, I asked her to share her hobbies and interests—a question that felt ordinary to me but left her visibly surprised. Coming from a country where gender disparities denied girls like her the opportunity to venture into public spaces, let alone discover themselves, and being the eldest of five siblings, her responsibilities left her with no time to explore a hobby. Understanding her life left me in awe, and I left our conversation with overwhelming gratitude for my own life. The cultural and systemic barriers both Gulsoom and Neelab faced gave me a deeper appreciation for the role of cultural sensitivity in addressing disparities in emotional and mental healthcare, even in non-medical spaces.

Over the subsequent months, Neelab and I grew together. She learned to explore her interests in drawing and writing short stories, while I came to realize that I spent far too much time focusing on what I lacked rather than appreciating what I was blessed with. Discovering her hobbies had a transformative impact on Neelab’s mental health and healing, helping her become more cheerful, confident, and emotionally expressive.

By the end of the year, I had fallen in love with tutoring. Each student I worked with showed me the interconnectedness of the emotional, mental, and social dimensions of health. Grace taught me the power of listening and seeing the strengths in those around me. With her unwavering spirit, Jessica taught me the power of perseverance. Then, there was Max, who modeled empathy and understanding. Each experience with the students reminded me that healing and caring for people isn’t limited to doctors and medicine; it happens in every moment of connection and understanding. Working with a diverse group of individuals from different backgrounds and experiences broadened my perspective on empathy and the many ways people support one another. Sometimes the most significant medical intervention is simply being there for someone when they need it the most.

Sandra Aitcheikh

The sexual revolution contributed to a more open discussion and acceptance of sexuality, while more traditional perspectives, often emphasizing abstinence, have influenced approaches to sexual education and discussions on related topics. These sentiments have gone beyond localized communities and have begun to affect the legislation in these areas. Our legislation dictates the necessary information to teach in schools and can reflect the political climate. The culture behind sexual education and the stigma surrounding it causes a possibility for limitation.

States usually push abstinence-only education and even revoke more holistic sexual education. The more conservative ideology in government does not push for a more comprehensive sexual education. It can increase rates of pregnancy and STIs, which can affect the health of the youth. To understand the extent of the effect of the stigma on the health of populations, it is essential to compare the types of education kids receive to the levels of STIs and pregnancy in people.

A goal is to highlight how the lack of education and misinformation is incredibly dangerous, as people will not make informed decisions, and how this can be caused by a biased health policy. A solution for spreading unbiased information would be to backtrack from mixing political and cultural ideologies into a neutral education system. Misinformation is a pathway for unresearched decisions that can harm population health. Find a better, more objective way to say this. For example, it would be beneficial to compare the rates of STIs and pregnancy in states with a more conservative education to states and countries that employ a more liberal education system to see how policy influences health outcomes.

Public health crises, like the rise of HIV/ AIDS, show how misinformation spreads rapidly. A common misconception is that HIV can be acquired by “...breathing the same air [as other infected people]” (Kaplan, 2022). This shows insufficient education on how infectious diseases spread, making preventative measures challenging to enact. This is why we must take an important look at misinformation and the effects that misinformation has on

the decisions of the youth. Education helps counter false ideas and allows individuals to make safer decisions.

The separation of church and state ensures that legislation is not influenced by religious views. However, to understand the differences that states face in enacting laws, it is important to understand that although the United States claims to have separation of church and state in the legislative process, liberal and conservative ideologies play a decisive role in shaping laws.

A prime example that shows how companies use religion to refuse reproductive rights is the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby case, which refuses to give out contraceptives in their health packages. Birth control, in the view of the company, is called “abortive” (Religion and the Constitution, n.d.) under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. The courts granted Hobby Lobby reason under statutory interpretation. This sets a precedent that shows how religion can be an exemption for comprehensive medical coverage. This shows that the court was divided between a faction that wanted laws under a secular influence and one that wanted laws to be influenced by religious culture.

In addition to cultural stigma, Kaplan continues to mention how people can delay their STI treatment and continue transmitting the viruses due to stigma deterrence. Therefore, it is vital to understand the origins of sexual stigma. People reference the role of Christianity, explaining how sex should not be had before marriage (Evans, n.d.). This can be a significant reason for the push for abstinence-only education in schools, primarily since the majority religion advocates for a reduction in education that would encourage premarital sex.

Not separating church and state in health education is counterproductive, as most religious teens do not cite religion for abstinence in adolescence. (Hayward, 2020). The statistics on the sexual health epidemic as teenagers still engage in premarital sex and disregard the information presented (Regnerus, 2007). Education plays a vital role in the safety of adolescents, showing how laws passed influence the level of sexual education received in schools.

Some states have mandates for compre-

hensive sex education, and some states do not have any mandates. Coincidentally, these states that vary in inclusivity and abstinence are correlated to the level of religious worship and political-religious ideology. Comprehensive sexual education includes incorporating the “whole student” without leaving sexual orientation and contraceptives unaddressed (USC College of Nursing 2018).

To understand why comprehensive sexual education is needed in the United States, in 2016, the United States had higher rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases than most other industrialized countries (Sedgh et al., 2015). When compared to other developed countries, American women had lower use of contraceptives and were more likely to have multiple sexual partners. This was correlated to a higher rate of sexually transmitted infections (USC Department of Nursing 2017). Levels of sexual education received and safe sex practices may correlate. To fully show a correlation, external variables in comparison should align. The women studied were of similar socioeconomic backgrounds and became sexually active at the same time (USC Department of Nursing 2017).

Domestically, the state with the highest teen birth rate in 2015 was Arkansas (USC Department of Nursing 2017). The national average of live teen births in the United States is 17 per 1000 females, placing Arkansas at almost double the national average with 30 live births per 1000 females between the ages of 15 and 19 (Arkansas Advocates 2021). It is important to note that “States that have had the most success, and the lowest teen birth rates nationally, do a much better job than Arkansas at educating young people about preventing pregnancy” (Arkansas Advocates 2021). Connecticut and Massachusetts had the lowest levels of teen births in 2016 (USC Department of Nursing 2017). Teen pregnancy rates have been dropping for over a decade - a total of 75% decrease, with an added 13% decrease from 2014 to 2015 (Lefranc, 2018). These numbers show a significant decrease in teen pregnancy rates due to the implementation of comprehensive sexual education programs, showing a possible connection between pregnancy rates and sexual health education. Connecticut has tackled this issue with a progressive tactic - the University of Connecticut has been using a plan called the “Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative” to address disparities in the community and target the populations with adoles-

cents who are at a higher risk for early parenthood.

In contrast to the “abstinence-only” policies present in states like Arkansas, Connecticut recognizes that there needs to be adequate access to contraceptives. The state recognizes that contraceptive access is vital and that education is also needed. In fact, in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2017), the percentage of teens who engaged in sexual intercourse decreased from 41.8% in 2007 to 32.4% in 2017 (Lefranc, 2018). This shows that teens had an education that would allow them to either safely engage in sexual intercourse or abstain due to the knowledge of STIs and pregnancy.

A common trend between the states with higher levels of teen pregnancy is the prevalence of abstinence-only sexual education. Some states, like Arkansas, do not require sexual education at all (Sex Education n.d.). This may be due to the influence of conservative influence on health policy. The counter to abstinence-only education is comprehensive sex education. In the middle of the two models is a program called “Plus” Education (Abstinence Education Programs: Definition, Funding, and Impact on Teen Sexual Behavior 2018). Abstinence-only education can be called “Sexual Risk Avoidance Education” as pregnancy prevention and STI reduction methods are downplayed. To introduce how the government supports this education (lack of separation of church and state at the origin), the government has been funding states serving this curriculum. The peak of this funding was implemented during the Bush administration to emphasize how this has also been split into party lines. It was reduced by the liberal predecessor, Barack Obama. Showing the different types of sexual education methods is vital for comparing how the education received affected the rate of STIs and pregnancy in the youth.

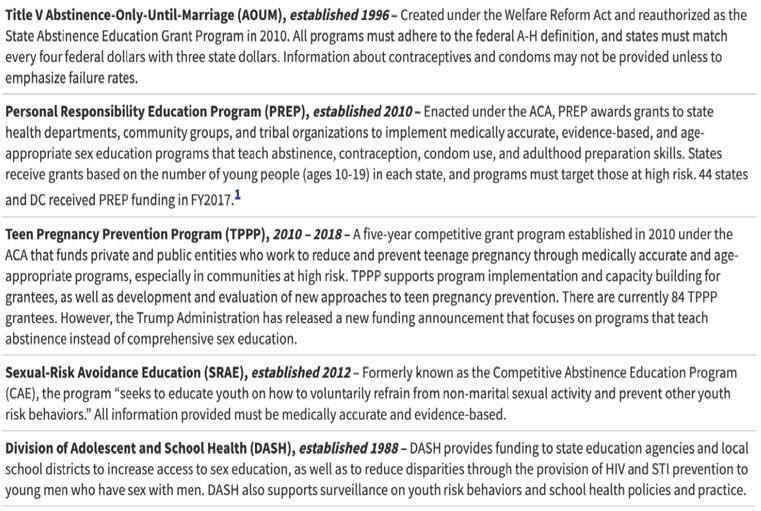

Table 1: Current Federal Funding Streams for Sex Education

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation. “Abstinence Education Programs: Definition, Funding, and Impact on Teen Sexual Behavior.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1 June 2018, www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/abstinence-education-programs-definition-funding-and-impact-on-teen-sexual-behavior/.

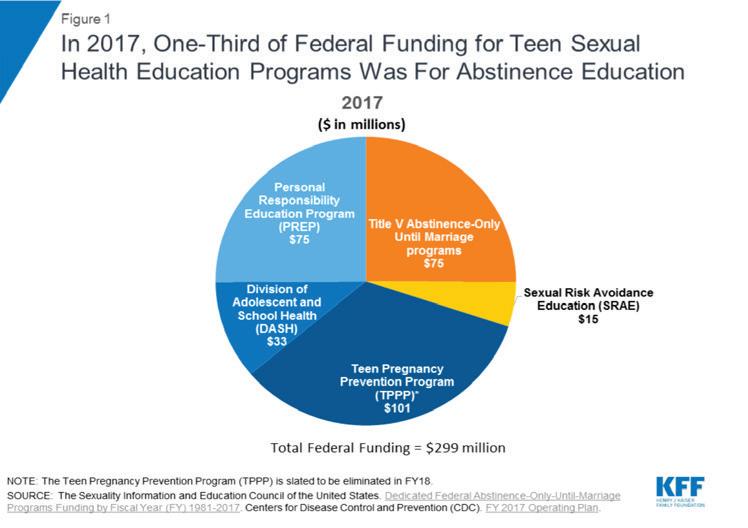

Table 1 (Women’s Health Policy 2018) proves to be a display of the diverse legislation that is enacted in different areas of our country. Differences in education painted by the political scene display a lack of universal and comprehensive education. Various acts passed, like the Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), serve as a proposal for legislation that our government bodies can take to reduce the misinformation currently circulating in schools. It is important to note how the federal government allocates funds for these education systems. Figure 1 will show how the government divides available funds for sexual education.

Table 1 explains how much money goes into abstinence-only education compared to more comprehensive and researched education methods. Research shows (Women’s Health Policy 2018) that one-third of federal funding goes to abstinence-only education, leading to the highest rates of pregnancy and STIs in the country. Instead, more funding needs to go to the evidence-backed comprehensive sex education programs. Almost a quarter of funding goes towards education only for abstinence. With an equal amount of federal funding being used for Personal Responsibility Education Programming, or PREP, almost half of the budget can be used for comprehensive education, especially since PREP is medically accurate.

The beginnings of sexual stigmatization in the United States stem from the conservative attitudes towards sex, labeled “taboo,” and leading to misinformation being spread. I propose a resolution for further comparative research on the rates of pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Infections in states where they have an abstinence-only policy when they transition into a more comprehensive sexual education base, just like the “Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative ‘’ in Connecticut. States like Arkansas highlight the sexual stigma that calls for the removal of policies for STI and pregnancy prevention. The United States should prioritize quality and

comprehensive sexual education.

References

“Concealability and Course.” ResearchGate, www.researchgate.net/ profile/David-Evans-48/publication/317721451 The stigma of sexuality concealability and course/ links/594a81570f7e9ba3beaf951a/The-stigma-of-sexuality-concealability-and-course. pdf.

Glover, Candace. “Data: Arkansas Needs a Different Strategy for Preventing Teen Births.” Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families (AACF), 30 June 2021, www. aradvocates.org/data-arkansas-needs-a-different-strategy-for-preventing-teen-births.

Hayward, Geoffrey M. “Religiosity and Premarital Sexual Behaviors Among Adolescents: An Analysis of Functional Form.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 58, no. 2, 2019, pp. 439–458. https:// doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12588.

Kaplan, Jonathan E. “HIV and AIDS Myths, Misconceptions, Rumors.” WebMD, 12 Dec. 2022, www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/ top-10-myths-misconceptions-about-hivaids.

Lefranc, Mary. “Connecticut Leads the Nation with Lowest Teen Birth Rate.” Connecticut Health Investigative Team, 20 Aug. 2018, c-hit.org/2018/08/20/connecticut-leads-the-nation-with-lowest-teenbirth-rate/.

“42 U.S. Code Chapter 21B - Religious Freedom Restoration.” Legal Information Institute, www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/ text/42/chapter-21B.

“Abstinence Education Programs: Definition, Funding, and Impact on Teen Sexual Behavior.” KFF, 1 June 2018, www. kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/ abstinence-education-programs-definition-funding-and-impact-on-teen-sexual-behavior/#:~:text=Abstinence%2DOnly%20Education%20%E2%80%93%20 Also%20called,prevent%20unintended%20 pregnancy%20and%20STIs.

Sedgh, Gilda, et al. “Adolescent Pregnancy, Birth, and Abortion Rates Across Countries: Levels and Recent Trends.” Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 56, no. 2, 2015, pp. 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jadohealth.2014.09.007.

Serena Lozandi

Being illegal means to be forbidden by law.

Forbidden by law to live, Mother hides in the attic during winter, with visions of salted droplets and shivers, rocking back and forth as her body boils over— defending itself against illegal viral parasites and concealing their presence within her fragile body’s blood.

Forbidden by law to live, Mother is a human being in a land in which she is forbidden by law to occupy

The American Dream is a public hospital, a vast waiting room with patients with head wounds, blood dripping down their skulls, drip, drip, dripping onto linoleum floors— blood is wine in fluorescent lighting yet the nurse calls in the patient who has a cough.

Mother is not a patient the American Dream is willing to see. She is forbidden by law, to live and occupy and must hope her shivering body outsmarts the intruders in her blood.

Jemma Parsons

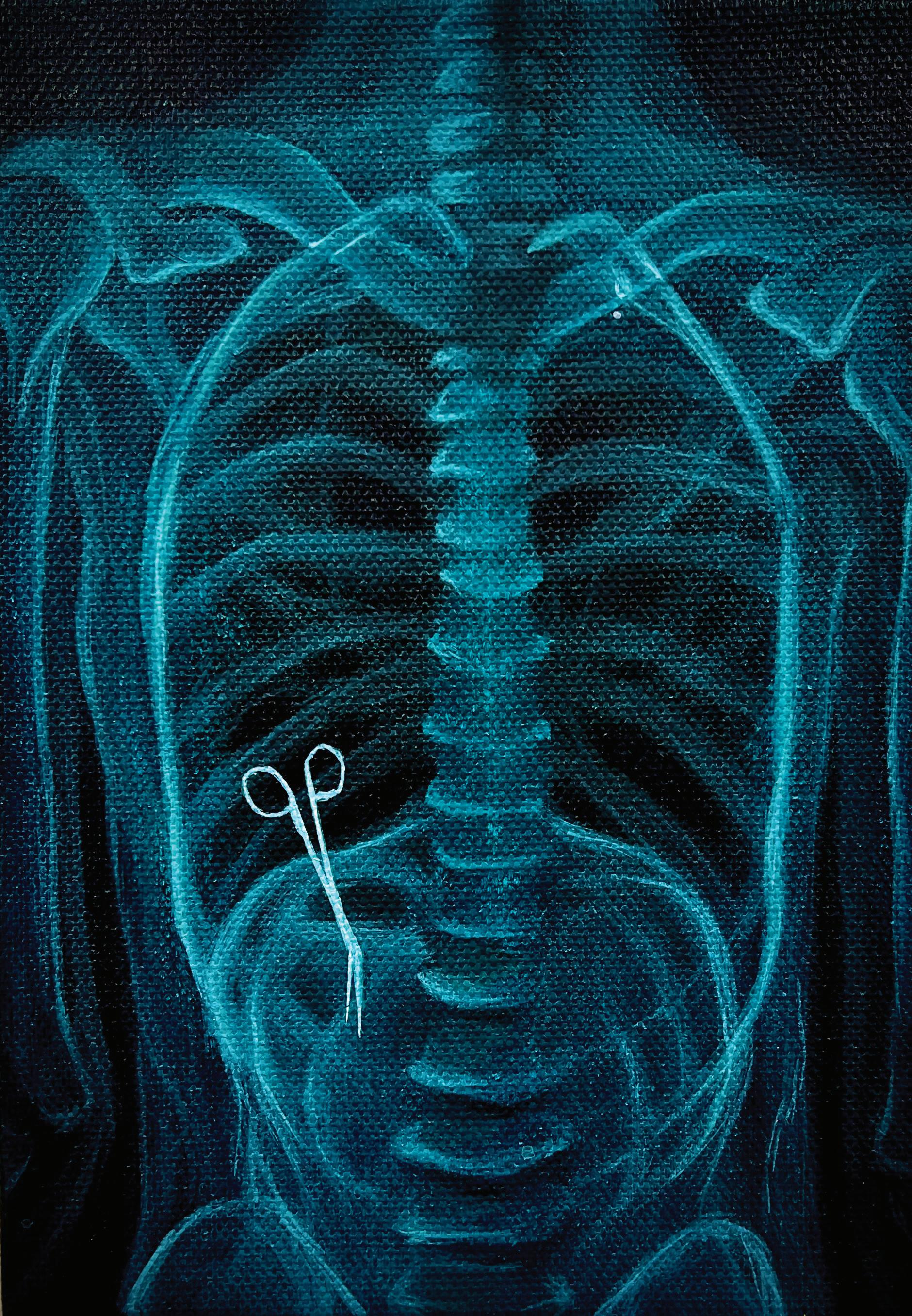

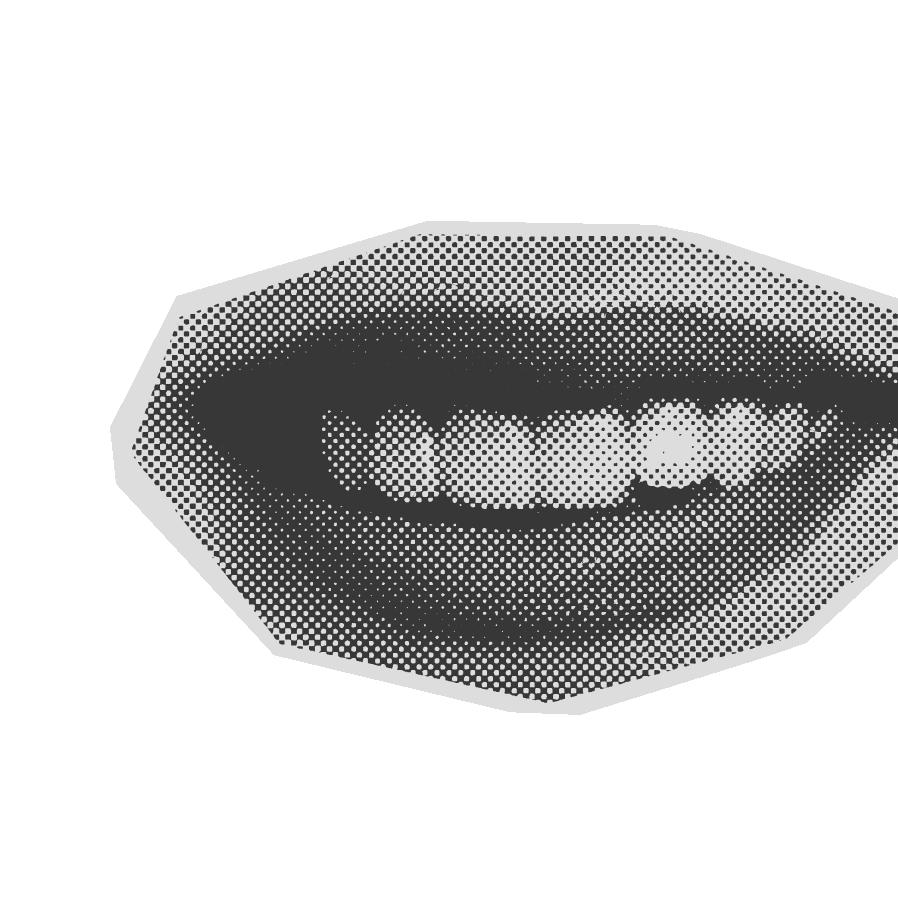

Medical negligence is a leading cause of postoperative death, involving a healthcare provider failing to follow the recognized standard of care during treatment. It may be caused by numerous factors, ranging from high stress conditions to gross incompetence in the healthcare professional. When negligence results in harm to the patient, it is considered to be medical malpractice, which accounts for 5% of personal injury suits.

The understated ubiquity of irreversible damage caused by flawed medical procedures, even those that are extremely routine, is a morbid reality that Americans risk facing every time they visit a hospital, and which they are expected to wave away with legal compensation if victimized. Despite advancements in modern medicine, the consequences of these mistakes are still primitive, grotesque, and deeply dehumanizing.

Acrylic on canvas, 2023

Noah Bennett

Growing up, I had paranoia about the piercing pain in my stomach I would sometimes get from eating. I was told it was just irritable bowel syndrome, and that I would have to ride it out. The pain feels like my guts are on fire. It feels warm and inflamed, yet sharp and dull. It made me feel broken, and the pain was sometimes so intense I could only lie there sweating and gritting my teeth alone. There was no defense, no prevention. I would spend multiple hours in the bathroom per day, until it became worse and worse. I had to seek help. At a doctor’s appointment with my primary care, her assistant suggested that I may have celiac disease, but the doctor ultimately suggested I seek out a specialist. In my head, I thought it was impossible. Celiacs has something to do with eating gluten, right? My stomach hurts no matter what I eat, so it didn’t fit the puzzle to me. I booked an appointment with a gastroenterologist (GI) and my thoughts began to drift. If it can’t be celiacs, what is wrong with me? My fears began to eat me up as I saw no positive outcome.

Upon hearing my symptoms, the GI doctor insisted on a full workup, endoscopy and colonoscopy. Endoscopy shows gastritis in the lower parts of my stomach. Inconclusive, no definite answer is found. I am feeling a little down, but I am both nervous and hopeful for the next procedure to come. The day before the colonoscopy, I went through an entire day of laxatives and stool softeners. The pain within my stomach was immense all day, and I was not allowed to eat any solid food or colored drinks. I grew increasingly tired of chicken broth, being that was all I could eat for the entire day. When the day comes, I arrive at the procedure center and patiently take my seat. The wait feels like hours while I hyperfocus on every name being called back. Eventually, I heard my name. The procedure goes great, and there is no sign of colon cancer. I feel relieved, but a feeling still sinks inside me. I still have no answer, despite this gut-wrenching gauntlet I went through. Negative thoughts began to race through my mind that maybe I was overreacting or faking it this entire time. I desperately needed reassurance that my pain was real. My last hope was the biopsies taken during the procedure. I would lay awake at night, wondering

what I was hoping to get out of this.

After a month’s wait, I arrived for my follow up. I don’t know what answer I was looking for, as none of them sounded great. I knew I wanted an answer, for the fear of the unknown was going to take me down. Upon shaking the GI’s hand, he wasted no time. I was handed a paper with a positive result for… celiacs? This cannot be right. He bluntly tells me that all I need to do is cut out gluten, and I’ll live a long life. The entire visit lasted for what felt like a few seconds. No medication, no surgery that can fix me, I just have to live with it. Is it really going to be as easy as that? It just didn’t make sense to me, it can’t be right. I was sure that gluten had no correlation to my stomach pain, and my family history is almost entirely clear. After sitting in my car for 30 minutes, I decided to text my loved ones and tell them the news. At this point, I was fully breaking down. I stopped to wonder, why am I so upset? It could’ve been way worse, I should be blessed to have an answer. Some may never reach a conclusion, and some may reach a diagnosis far worse than mine. I was devastated, it didn’t matter if it could be worse at the moment. I drove home and went straight to bed. My appetite was gone at the time, but eventually in an attempt to grasp back onto normalcy, I felt the need to get some food. After looking around, a harsh reality crashed into me like a brick wall. Everything in my house had gluten in it. There was not a single piece of food I could eat. What was once my home was now a reminder of what I was trying to forget. I felt my vision go blank as I didn’t want to perceive what I was seeing, but after staring silently at the wall, part of me knew I was going to have to eventually face the fate given to me. At the store, I noticed that true gluten-free options are scarce. Four times the price, just for gluten-free mac and cheese. The noodles didn’t impress me, but I wasn’t going to give up so easily. I ordered a gluten-free pizza from a chain pizza place, learning a hard lesson. Despite the ingredients being gluten-free, my stomach still hurt. The burning feeling in my stomach made my skin crawl at my realization. Cross-contamination. The pizza was cooked in the same oven as the other pizzas. It didn’t matter if the ingredients were gluten-free. It was contaminated.

I decided that maybe it was smarter to cook my own food. I cooked my own lasagna as my family had theirs in the oven at the same time. Contaminated. I cooked soup but had set the spoon down on the countertop for just a second while away. Once again, contaminated. I had no idea it was this serious, no one did. If I continue to eat gluten, I will die. Stomach pain is one of the early symptoms, a warning for what’s to come. The symptoms would eventually slowly kill me. I had to accept that I can no longer eat fast food, restaurant food, or even food at a friend’s house. Slowly, I began to distance myself from friends. I would reject all dinner plans, as I felt like nowhere was safe. I couldn’t even drink beer. Having to explain my condition makes me feel like an outcast, and it reminds me of all the things I will never be able to do again. My own parents don’t even understand. Constantly cooking food that is contaminated. Many times, when I am at an event, I am offered a salad while everyone else gets actual food. The salad became the symbolization of all my negative thoughts. A reminder that no one seemingly knows what it’s like to live like this. A salad made in the same kitchen as everything else is contaminated. The idea of going to birthday parties or dinner plans terrified me. Being offered a measly salad feels dehumanizing while watching others eat actual food.

As I have come to terms with my condition, I’ve adopted a brother outlook. It may have felt like my life was over at first, but I am now more mature. I’ve found multiple restaurants which can accommodate someone like me, and there are brands that make gluten-free alternatives that are almost indistinguishable from “normal” products. Being able to eat out or even just finding a new brand of bread that tastes less terrible is what keeps me going. Things that I took for granted are now something I treasure. Rice was never something I appreciated more than a good meal, but now it feels like the opposite of a salad. Though it is nothing special, it’s always there for me when making dinner plans. Affordable, easy to make, and stores away nicely. The ground will always be beneath my feet, the air will always fill my lungs, and rice will always be gluten free. I always feel blessed to find new foods in stores I can eat, or new places that can cater to my needs. My disease can’t be seen with the naked eye, but it still affects my day-to-day living. It’s almost been a year since my diagnosis, and life has just been trying to regain what I have lost,

and to live a normal life. I now share my story, in the hope that people will begin to understand what it’s like to live with an invisible disease. Through this life-changing diagnosis, I have discovered a love for cooking and medicine, as well as an urge to do well in life despite my limitations. A disease that I thought ruined my life at one point, is now something I refuse to let stop me. I instead weaponize it to keep pushing myself, beyond what I used to believe I was capable of.

Moriah Lee

While working at New York’s Beth Abraham Hospital, neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks encountered over 80 patients who previously had encephalitis lethargica, a neurological condition which had affected millions in the early 1930s. This had led to a condition called postencephalitic parkinsonism, causing these individuals to be stuck in catatonic states while their minds were fully conscious.

During the summer of 1969, Dr. Sacks realized that the patients were able to respond to certain stimuli, such as saying their name, throwing them a ball, or listening to music (Marshall). This was then followed by the use of a new drug Levodopa, also called L-DOPA, a medication developed for Parkinson’s disease patients. The use of L-DOPA resulted in a massive “awakening” of the catatonic patients, and for a period of time, they were able to walk, talk, and reclaim their lives. Unfortunately, L-DOPA resulted in numerous side effects and rapidly became ineffective, and the vast majority of the patients eventually regressed back to their original states within a year, with many becoming worse than before.

Before the use of L-DOPA, Dr. Sacks experimented with music therapy, which had a measurable impact on many of the patients. Music therapy has been used for a variety of neurological conditions and has many benefits, without the many side effects that often come with pharmaceutical drugs. Understanding the benefits of treatments such as music therapy may help to provide alternatives to the mainstream treatment of medication.

Encephalitis Lethargica

Encephalitis lethargica has two stages:

the acute stage which occurs immediately, and the chronic stage which can occur months to years later. The chronic stage, postencephalitic parkinsonism, results in bradykinesia: slow or delayed movement, or complete inability to move. However, postencephalitic parkinsonism patients can quickly shift from akinetic to perfect mobility rapidly. This can usually be initiated by external stimuli such as tossing them a ball or playing them music. (Hoffman and Vilensky).

Despite years of research, the cause of encephalitis lethargica is still unknown. As encephalitis lethargica has almost completely and mysteriously disappeared, it is difficult to continue researching for a cause, as there are very few cases to glean information from. Identifying a possible treatment is very difficult and as such, no clear and effective treatment has emerged. However, treatments for Parkinson’s disease appear to be fairly effective on some postencephalitic patients, such as the use of music and touch therapy, as well as the drug, levodopa, which is incredibly effective for a short period of time but had a very limited period of benefit.

Dopamine is a brain chemical produced in many regions of the brain, and is linked to many important physical and cognitive functions (Olguín et al). One of these key functions is the motor functions pathway, which can create issues with movement when dopamine levels are abnormal. Medical conditions like Parkinson’s disease and encephalitis lethargica have been linked to insufficient dopamine levels.

Levodopa is a medication originally used as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease, due to its ability to treat dopamine deficien-

cy (Gandhi and Saadabadi). However, a study in 2016 found that its use can cause permanent change to an individual’s DNA, causing the medication to become ineffective within a few years, as well as leading to dyskinesia, a condition characterized by involuntary, jerky movements (Figge et al). Levodopa-induced dyskinesia was identified in about 50% of patients within 5 years of beginning treatment.

Listening to music has been found to be highly stimulating for the brain, activating specific regions of the brain which frequently are not activated by other stimuli. Most importantly, music activates key regions of the brain that produce dopamine (Jäncke).

Many studies on music therapy have found that it can facilitate recovery of movement for stroke, Parkinson’s, and traumatic brain injury patients (Trimble and Hesdorffer). A meta-analysis in 2021 found statistical significance that music therapy improved motor function, balance, and freezing of gait (Zhou et al). The study concluded that while pharmacotherapy is symptomatic and loses effectiveness over time, music therapy creates positive emotional response, has effective results, and has no negative side effect, illustrating the benefits of music therapy over pharmaceuticals.

Apart from physical benefits, music therapy can also be extremely beneficial for the emotional wellbeing of patients. Patients with neurological conditions such as encephalitis lethargica and Parkinson’s are often at a higher risk for conditions such as depression (Raglio et al). A review of 25 studies on a variety of neurological conditions found that music therapy decreased rates of depression and anxiety, and improved overall quality of life.

Frances D. developed encephalitis lethargica at 15 years old. This caused her to be frozen in place for over 25 years. In her own words, “[e]ither I am held still, or I am forced to accelerate. I no longer seem to have any in-between states” (Sacks, 1973). She was treated with L-DOPA, which decreased her freezing, but led to many side effects such as tics and respiratory crises. She was forced to discontinue the drug when the side effects became too overwhelming, causing her condition to return even worse than before. Ms. D fell into a deep state of depression after the discontinuation of L-DOPA, as she had briefly felt in control of her life, only to quickly lose her freedom. Prior to the use of L-DOPA, however, Ms. D. exhibited

positive responses to music therapy. Despite only being able to move freely while the music was playing, this was a reliable method that had no negative side effects (Sacks).

Ed M. had a very unique form of encephalitis lethargica, where his body was split in half: one side was very energetic and suffered from jerking and tics, while the other was frozen. His EEG was normally asymmetrical, but when playing the piano or organ, the asymmetry disappeared. Mr. M. was unable to be treated with any medications, as they would help one side of his body, but worsen the symptoms on the other half. Music therapy through playing piano or organ caused the symptoms of both sides to temporarily disappear (Sacks).

Postencephalitic parkinsonism shares many features with Parkinson’s disease, appearing to stem from a dopamine deficiency. As such, studies on Parkinson’s patients can be used as a good model for postencephalitic parkinsonism, which is much rarer. While music therapy tends to have results which are less uniform and systematic, its beneficial effects on Parkinson’s disease, and consequently encephalitis lethargica, are well-supported by research.

As a key factor of postencephalitic parkinsonism is dopamine deficiency, dopamine-producing regions of the brain are an essential area of focus. (Olguín et al). Music therapy helps to stimulate many of these areas, aiding in dopamine production which is crucial for patients with postencephalitic parkinsonism.

While L-DOPA has proven to be highly effective for postencephalitic parkinsonism patients, both case studies and research have found that the effects of L-DOPA are fairly short-term, and frequently cause negative side effects. It functions by becoming a dopamine replacement, an effect which music therapy also achieves. For patients in the chronic stages with postencephalitic parkinsonism, L-DOPA cannot be a truly viable option, due to the many harmful side effects it causes, such as the respiratory crises, and the potential that it could become ineffective before the patient has time to fully recover (Sacks).

As such, music therapy proves to be a much safer and effective treatment option when compared to L-DOPA. The use of medication comes with far more inherent risks compared to non-chemical treatments such as music therapy. Additionally, music therapy is far more enjoyable, cost effective, and does not lose effectiveness. It is also far more versatile compared to med-

ications. Even a medication which is highly effective with generally low side effects can have negative consequences when used in tandem with other medications or on individuals with multiple medical conditions. In contrast, music therapy has essentially no negative side effects and can be adapted to fit the individual patient.

A Culture of Prescribing America is facing a culture of prescribing: the idea that health issues should be solved first and foremost by taking medications. In 2012, nearly 60% of US adults were taking at least one prescription drug. For every additional prescription medication taken, the risk of adverse drug events increases by 7-10% (Brownlee and Garber). Additionally, this culture of prescribing creates financial strain on many individuals, as medications are often incredibly expensive.

The story of the encephalitis lethargica patients of Beth Abraham hospital serves as a reminder of the importance of shifting our society’s focus away from medications. Every day, individuals suffer from negative side effects, financial burdens, and even premature deaths due to unnecessary prescriptions. By exploring alternative treatment options such as music therapy, America can move towards a society in which people can live longer and healthier lives.

References

Brownlee, S., Garber, J. (2019). Medication Overload: America’s Other Drug Problem. The Lown Institute.

Dale, R. C., Church, A. J., Surtees, R. A., Lees, A. J., Adcock, J. E., Harding, B., . . . Giovannoni, G. (2004). Encephalitis lethargica syndrome: 20 new cases and evidence of basal ganglia autoimmunity. Brain, Volume 127, Issue 1, 21-33.

Figge, D. A., Eskow Jaunarajs, K. L., & Standaert, D. G. (2016). Dynamic DNA Methylation Regulates Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia. JNeurosci, 6514-6524.

Gandhi, K. R., & Saadabadi, A. (2023, April 17). Levodopa (L-Dopa). Retrieved from National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK482140/#:~:text=Levodopa%20is%20 th e%20precursor%20to,symptoms%20apparent%20in%20Parkinson%20disease

Hoffman, L. A., & Vilensky, J. A. (2017). Encephalitis lethargica: 100 years after the epidemic. Brain, 2246-2251.

Juarez Olguín, H., Calderon Guzman, D.,

Hernandez Garcia, E., & Barragan Mejia, G. (2016). The Role of Dopamine and Its Dysfunction as a Consequence of Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

Jancke, L. (2008). Music, memory and emotion. J Biol., 21.

M., K., & MM., E. (2001). A contemporary case of encephalitis lethargica. Clin Neuropathol, 2-7.

Marshall, P. (Director). (1990). Awakenings [Motion Picture].

Raglio, R., Attardo, L., Gontero, Giulia., Rollino, S., Groppo, E., Granieri, E. (2015). Effects of music and music therapy on mood in neurological patients. World J. Psychiatry, 68-78.

Sacks, O. (1973). Awakenings. London: Duckworth & Co.

Sacks, O. (2008). Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Trimble, M., & Hesdorffer, M. (2017). Music and the brain: the neuroscience of music and musical appreciation. BJPsych Int., 28-31

Zhou, Z., Zhou, R., Wei, W., Luan, R., & Li, K. (2021). Effects of music-based movement therapy on motor function, balance, gait, mental health, and quality of life for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation, Volume 35, Issue 7, 937-951.

Jordan Hamburg

Time is Medicine depicts a standard orange prescription bottle spilling open to reveal pill capsules taking the form of warped clocks. The surreal composition immediately evokes time’s role in physical and psychological healing. The melting clocks, reminiscent of Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory, suggest the fluidity of time and how it stretches and compresses based on perception, especially in the context of illness and healing. Medicine often follows strict temporal frameworks—dosage schedules, treatment timelines, and recovery periods—yet healing itself is not always so clear. Despite similarities in patients’ diagnosis and treatment, their sense of time is not identical, hence the warped clocks. The piece also critiques the healthcare industry’s over-reliance on pharmaceutical drugs, suggesting time as a fundamental healer, sometimes just as powerful as medication.

Liam Mahony

Few areas within the healthcare field are as confounding or nuanced as pain perception. For both medical practitioners and modern philosophers, conceptualizing pain’s effect on the body—and the psyche—is an increasing challenge. In light of these complexities, the account of pain presented by Descartes, often referred to as “the father of modern philosophy,” is worth revisiting. By examining these philosophical ideas and their intersection with new theories in pain, future medical practitioners may better appreciate the gray area within a particularly systematic career field.

At the heart of Descarte’s philosophy is his mind-body dualism. This idea posits that two distinct substances, namely the mechanical matter of the body along with the immaterial substance of the mind, interact with each other. Any dualist like Decsartes has difficulty explaining perception; namely, how do purely biological processes within the body influence an immaterial thinking mind? The Cartesian account for pain, as discussed in the Treatise on Man, is an attempt to mold pain perception into this overarching dualistic philosophy. He claims that “animal spirits” (or fluids within the bloodstream) pass through the initial location of pain and, through the pineal gland, are interpreted in the brain. The soul’s connection through this gland unifies the mind with the mechanical aspects of the body, as Descartes refers to it as “the principle seat of the soul” (Ariew, 443). In a letter to Fromondus, Descartes further develops this position that pain must primarily be a mental phenomenon and interpreted through the rational part of the soul. He mentions that, since individuals still feel sensations in missing or amputated limbs, this sensation “would certainly not have happened if the feelings [or] sensation of pain occurred outside the brain.” (Ariew, 146). Like other perceptions, the rational faculty of the mind and the mechanical aspect of the body work in conjunction with one another to interpret pain. Apart from some of the obvious anatomical errors, Decsartes makes within his theory of pain, a deeper underlying issue still remains. As previously mentioned, Descartes offers a fuzzy connection between the physical and mental realms in processing pain. For instance, if one concedes that pain is primarily a mental sensation, the role the

initial physical stimuli play loses its significance. Although Descartes does believe that some intensely physical pain, like feeling “fire burning in the hand” (Ariew, 453) trumps the mind’s pain-regulating power, what role the mind and body play in perception still appears convoluted. Descartes’ Passions of the Soul tries to respond to this objection, detailing how emotions the mind feels differ from pure bodily perceptions. There are external perceptions worked primarily through the senses, perceptions relating solely to the body (like pain), and perceptions of the soul, which “we do not usually know any proximate cause” for (Ariew, R. 443). Perceptions are interpreted through the soul’s rational interpretations and can excite different behavior than what the body would naturally be inclined to do. Using an analogy of a soldier, Descartes claims that the soul can ignite a feeling of courage even when the body is inclined to flee, since some reasons can: “persuade us that the peril is not great; that there is always more safety in defense than in flight; [and] that we should have the glory and the joy of having vanquished...” (Ariew, 443)

In this natural fight-or-flight situation, Descartes emphasizes that external situations can mitigate the risk-averse inclinations of the body. This, hypothetically, has a neat translation toward pain management. Take running a marathon: although the immediate physical stress is intense, the personal satisfaction one gets after finishing the race makes the pain bearable. Descartes correctly argues that some incredibly painful experiences can be endured through willpower or volition, slightly clarifying this connection between mind and body. Although Descartes does rely on reason in controlling emotions, some physical sensations are simply far more difficult to override.

In part due to the numerous ways Descartes offers in analyzing emotional and rational regulation in pain perception, dualism had a leading influence on medicine and healthcare for hundreds of years after his publications (Gold). Many of his writings focus primarily on how the person themselves manages pain; however, as the research below will suggest, one’s surrounding environment is critical to this understanding as well. Not only is the connection between mind and body unclear, but the connection between the individual and their environment remains similarly ambiguous. This connection is critical to highlight for medical practitioners

today, as the complexities and subjectivity socio-environmental factors have in pain perception add a layer of nuance to a rather pathological-driven field of study.

Biophysical Model and Critiques

Pain is a particularly nuanced and multifaceted topic within healthcare, and increasingly comprehensive theories of pain emerging in the past decades aim to provide fuller pictures of social, pathological, and environmental influences on health. The biopsychosocial model is a recent theoretical approach that emphasizes the role sociocultural factors have in conceptualizing pain (Tracy). Research suggests some genes can only be expressed through the presence of environmental triggers, and these environmentally dependent genes could be modified by social and political factors (Braverman). One example of this theory was done through an experiment conducted by Bath University, in which they revealed participants had a lower pain tolerance (having their hand placed in a cold presser) when measured alone rather than with another friend in the room (Edwards). Non-biological factors, like trust, empathy, and resilience, appear to have a significant effect on how an individual perceives pain (Tracy). As such, US medical school curricula and healthcare training services have been integrating this model into their practices (Roberts). Using biophysical principles has been shown to greatly aid chronically ill and functionally impaired individuals (Kusnanto) as opposed to biomedical models, which have been criticized for their overreliance on using pathology in treatment, particularly for psychological disturbances (Engel). With this evidence at hand, both medical professionals and philosophers alike are distancing themselves from ideas that fail to incorporate environmental influences that affect pain perception. Since George Engel first proposed the biophysical model in the late 1970s, Biomedical theories of pain have borne the brunt of these critiques. The human body is not strictly a mechanical configuration, and pathology itself could never be sufficient to fully comprehend an individual’s perception of pain. Considering the immense influence Descartes had on the scientific revolution in medicine, his ideas have fallen prey to these challenges as well. Practitioners like Jeffery Gold have gone as far as to label Cartesian dualism as “dehumanizing” and reductionist (Gold). Treatment of patients’ bodies as nothing more than a non-emotive mechanism is believed to have substantial roots in Cartesianism. Descartes would, however, challenge the idea that his medical thought is solely

reductionist, as commentators like Gold have targeted him. Differentiating the mind as a unique substance implies that it does not need to process pain mechanically as the body would. In addition, Descartes argues in the Passions how one’s natural environment affects perception. He claims that volition alone is insufficient to cause some bodily movements, such as dilating one’s pupils, since “...nature has joined the movement of the gland that serves to thrust forth the spirits toward the optic nerve in the manner requisite for enlarging or diminishing the pupil...” (Descartes, Ariew, 453).

In response to the challenges above, Descartes mentions how one’s natural environment does play a role in behavior and perception. Whether this short passage provides a strong enough correlation to the larger emphasis environmental factors have in the biophysical model is up for interpretation. Regardless, given the ways the Passions detail how the mind can analyze perception, critiques like Gold’s ultimately fall flat. Even if there is a strong correlation between biomedical models of pain and Cartesianism, it would be an error to conflate dualism with total reductionism. An emphasis on the non-quantifiable factors influencing pain is nonetheless a point of contention in Cartesianism.

Conclusion

The extent to which pain is primarily a pathological phenomenon, nature’s role in pain perception, and the impact pain has to diminish one’s overall well-being make this field of study both a medical and philosophical point of interest. Given its significant biological, social, and normative importance in someone’s life, it is worthwhile to analyze Descartes’ highly influential views in light of modern pain research. Medicine and healthcare, although viewed strictly as a scientific endeavor, carries an immense amount of subjectivity. This case study on pain philosophy serves as a reminder that, given the inescapable nature of nuance within the healthcare field, practitioners should embrace this gray area rather than dismiss it outright.

References

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014 Jan-Feb;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19-31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. PMID: 24385661; PMCID: PMC3863696.

Descartes, Treatise on Man. Sélection translated from De l’homme et de la formation du foetus, edited by Claude Clerselier (Paris, 1664). Translated by P. R.

Sloan.

Descartes, R., & Ariew, R. (2000). Philosophical essays and correspondence. Hackett Publishing.

Edwards, Rhiannona,b,*; Eccleston, Christopherb; Keogh, Edmunda,b. Observer influences on pain: an experimental series examining same-sex and opposite-sex friends, strangers, and romantic partners. PAIN 158(5):p 846-855, May 2017. | DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000840

Engel, G. (2012). The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1521/ pdps.2012.40.3.377

Gold, Jeffrey. “Cartesian Dualism and the Current Crisis in Medicine — A Plea for a Philosophical Approach: Discussion Paper.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 78, no. 8 (1985): 663–66. https:// doi.org/10.1177/014107688507800813.

Kusnanto, H., Agustian, D., & Hilmanto, D. (2018). Biopsychosocial model of illnesses in primary care: A hermeneutic literature review. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 7(3), 497–500. https:// doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc14517

Smith, C. U. M., and others, ‘René Descartes’, The Animal Spirit Doctrine and the Origins of Neurophysiology (2012; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 Sept. 2012)

Tracy, Lincoln M. “Psychosocial Factors and Their Influence on the Experience of Pain.” Pain Reports 2, no. 4 (2017): e602–e602. https://doi.org/10.1097/ PR9.0000000000000602.

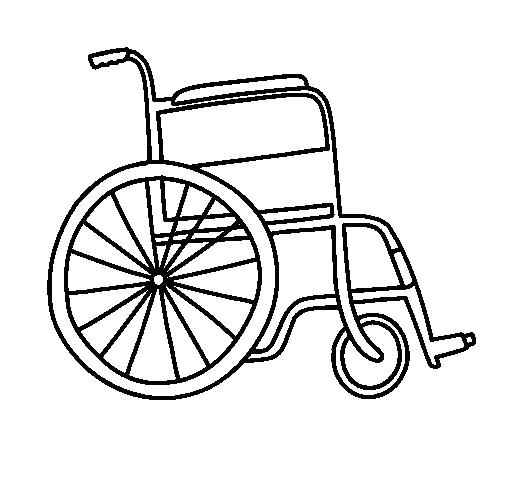

Kavery Kallichanda

The best of my job— Freedom from the monotony of standing an unneeded automation for hours. Fresh air and company, him in his wheelchair and me behind, soaking in the sunshine and human words. Who knew I was his freedom as much as he was mine. Freedom from the monotony of a lonely hospital bed.

Serene Abulhaija

In homes of sand and stone, breath is survival

Burdened by dust that settles like a second skin. The air hums war songs; lullabies fade to echoes. Time is not counted here, only endured.

Mothers knead dough, hands worn and trembling, Their knuckles hardened by hunger and prayer.

Fathers return as shadows, bodies gaunt and hollowed, Bearing the weight of the walls that fell too soon.

In this landscape of constant ache,

Health is a luxury whispered, never promised.

Wounds bloom like open graves beneath fraying gauze, Fevers rage through nights where medicine is a distant wish.

Hospitals collapse before the wounded arrive, And the sick learn that waiting is the closest thing to a cure.

To speak of healing is to dream aloud,

To carve a world no one has seen.

But what is health to the broken-bodied, To the spirit stitched and restitched on scene?

It is the miracle of rising despite it all,

To touch the sun with trembling fingers,

To teach our children to dance in the ruins, Their feet pounding defiance into the earth.

It is knowing that scars are maps, not endings, That even in the hush of grief, we still sing Soft voices threading through shattered streets, Humming lullabies to a land that remembers.

To dare to imagine that one day, Breath will be more than survival.

Growing up in a Middle Eastern household, Abulhaija experienced love in quiet, unspoken gestures—one of the most tender being the simple act of peeling fruit. Her parents and grandparents instinctively handed her slices of oranges, apples, or pomegranates, never asking if she wanted them but knowing she did. This small yet profound act symbolized care, healing, and connection, reflecting a broader cultural tradition where food serves as both nourishment and remedy. The wisdom of generations before—offering citrus to boost immunity, herbal teas to soothe, and honey as a cure-all—demonstrates how love is carried through everyday rituals.

The Hand That Heals You captures the warmth of these hands—wrinkled, adorned, and marked by time—hands that have carried children, prepared meals, and worked tirelessly yet still take the time to peel fruit. Through this piece, Abulhaija honors her family and the countless others who express love through food, highlighting how the simplest moments often hold the deepest meaning. It is a tribute to cultural heritage, reminding us that devotion is not only found in grand gestures but also in the quiet, ordinary rituals that sustain and heal.

Media: Procreate on iPad Pro

Violet Adams, Madeline Damon, Ciana Raley, and Isabel Reiter

Introduction

Receiving a diagnosis of cognitive impairment (CI) can be life changing, not only for the patient but for their caregivers as well. Disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease present unique challenges in social-emotional wellbeing that can become extremely isolating. Inspired by the Meet Me at MoMA program–the first of its kind designed for adults with dementia–The Art in Mind program at the James Museum of Art (JMA) in downtown St. Petersburg focuses on fostering expression, connection, and a positive experience through the use of interactive art gallery tours. The program offers discussion-based, hour-long tours to adults with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of CI and aims to enrich the lives of the participants by providing them with intellectual stimulation, social inclusion, and a place to foster emotional connections with their caregivers and each other. Tours are unbiased, non-judgmental, and designed with the participants at the center.

CI presents challenges in data collection, especially when methodology is heavily reliant on self-report data. Researchers in the past have modified their data collection methods by using simplified question formats, observational techniques, and flexible interview strategies (Fisher et al., 2006; Philpin et al., 2005). Additionally, caregivers may also provide valuable insight to the participant’s experience by expanding on responses, validating experiences, and fostering participant engagement. Independent caregiver assessments further improve data accuracy and provide participants with a sense of value in the process (Philpin, et al., 2005; Fry et al., 2021). This study has two goals: (1) to analyze data from previous AIM sessions at the JMA to assess the impact of the tour on individuals with CI and their caregivers, and (2) to create a new caregiver survey to improve measurement of their perspectives on the tours.

Participants

Participants included 32 individuals with memory loss and CI, such as Alzheimer’s disease, along with a subset of their caregivers. Participants had varying levels of memory loss, ranging from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia to a formal diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. No additional demographic information

was collected.

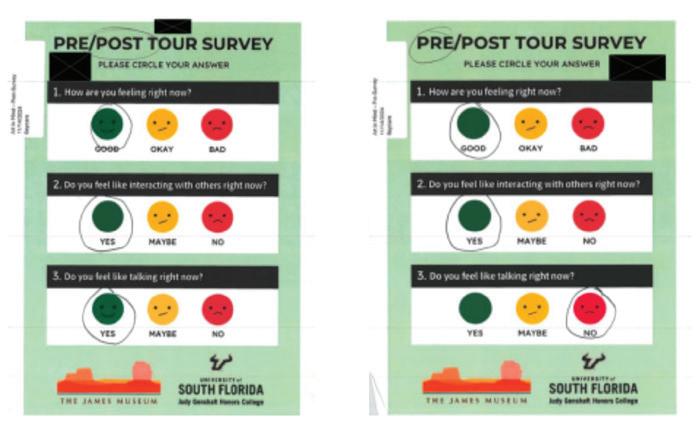

A three-question pictorial self-report Likert scale was developed for the AIM program based on previous research on survey development for those with CI. The survey was originally designed by USFSP Honors students in previous iterations of the Healing Arts course and was first administered in its current form in Spring 2024. This survey is designed for ease of use, even for those with severe impairments. It includes the following questions:

“How are you feeling right now?”

“Do you feel like interacting with others right now?”

“Do you feel like talking right now?”

Response options were either “Good,” “Okay,” or “Bad” for Q1 and Q2 and “Yes,” “Maybe,” or “No” for Q3. Each response option was accompanied by an emotive face (happy, neutral, and sad) to aid comprehension. A sample of this survey can be found in Appendix A, with participant names redacted.

Upon arrival, participants created name tags and completed a pre-tour survey assessing mood, desire to interact with others, and willingness to talk. Each participant was paired with a companion from the Judy Genshaft Honors College, and some were accompanied by caregivers as well. Assistance was provided as needed. The same procedure was repeated for a post-tour survey to evaluate changes in responses. Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Facilitators were trained to foster a patient, enthusiastic,and relaxing environment, and orient participants to enhance the experience of the memory loss group. Tours incorporated Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) and Personal Response Strategies (PRS) to encourage discussion, helping participants to explore emotions, memories, and thoughts that might otherwise remain inaccessible.

It was initially hypothesized that the AIM program would increase participant mood, communication, and desire to interact

with others. Given the ordinal nature of the data, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (non-parametric alternative to paired t-test) was utilized to assess differences in median scores between pre- and post-survey scores.

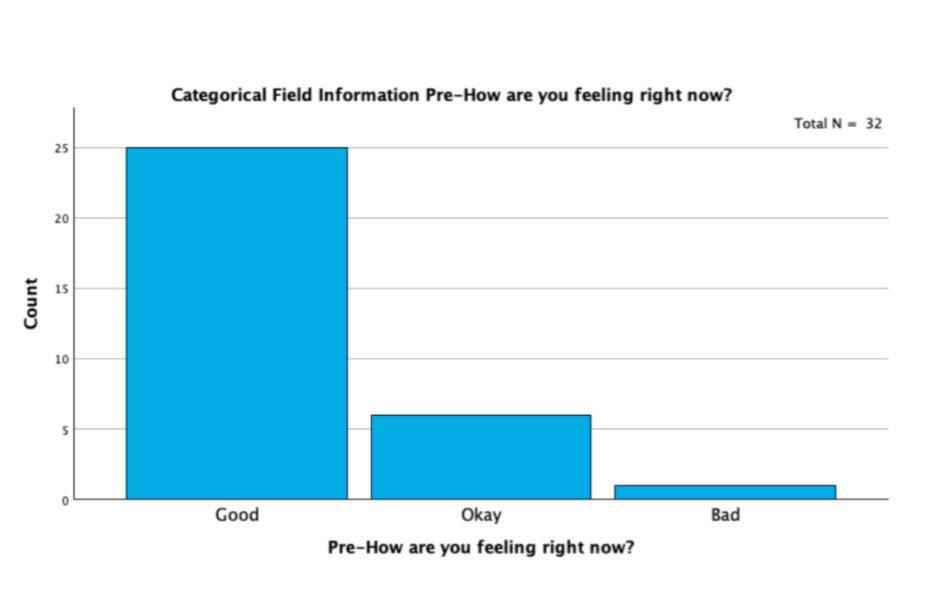

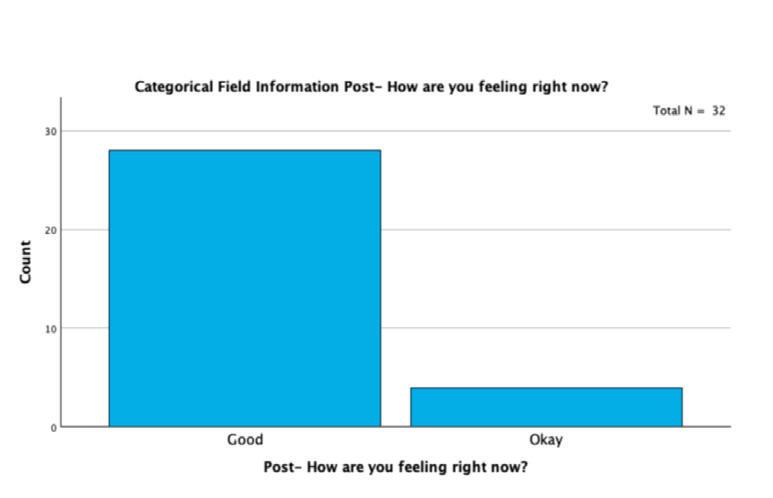

For the first set of variables–“Pre-How are you feeling right now?” and “Post-How are you feeling right now?”–the results were not statistically significant (p= .206), leading to the retention of the null hypothesis. However, an interesting trend emerged: As shown in Figure 1, pre-tour responses ranged from “Good” to “Bad,” whereas the post-tour survey data (Figure 2) indicated that no participants selected “Bad.”

Analysis of Q2, “Do you feel like interacting with others right now?”, also yielded no significant change (p= .915), thus the null hypothesis was retained.

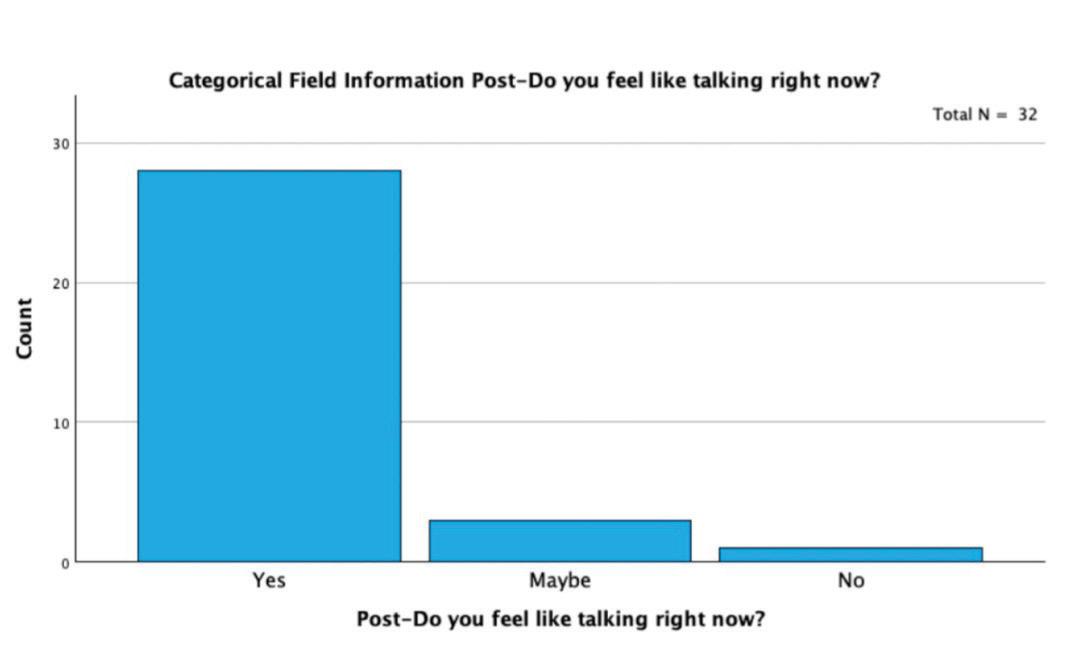

Lastly, analysis of Q3, “Pre-Do you feel like talking right now?” and “Post-Do you feel like talking right now?” showed no statistical significance (p= .885). However, a notable shift in response patterns was observed in Figures 3 and 4: post-tour, fewer participants selected “No,” while responses indicating “Maybe” and “Yes” increased.

Discussion

Although the results did not indicate a statistically significant effect for tour participants, several positive impacts were observed. Notably, several participants who initially responded “No” to Q3 later selected “Yes” in the post-tour survey. Facilitators also reported increased engagement in conversations among both participants and caregivers as the tours progressed.

To more accurately capture the benefits of the AIM program, improvements in data collection are necessary. Given the challenges of surveying individuals with CI, a more detailed questionnaire–despite enhancing reliability and validity and allowing for deeper analysis–may lead to frustration for participants. To address this, the present study proposes the Art in Mind Caregiver Survey (Appendix B) to gain deeper insight into participants’ experiences through caregiver perspectives of the AIM tour’s impact on their companion. The survey includes items assessing participant’s experience including:

- Item 6: “My companion’s mood improved throughout the experience.”

- Item 7: “My companion and I talked about memories during this tour.”

Additionally, items evaluating the caregiver’s own experience include:

- Item 1: “I feel a stronger sense of community after this experience.”

- Item 2 “My mood has improved after this tour.”

- Item 3: “I enjoyed taking part in conversations surrounding the art.”

- Item 5: “I would recommend these activities to other caregivers and groups.”

- Item 8: “I feel closer to my companion after this tour.”

- Item 9: “I would come back to the Art in Mind tour again.”

- Item 10: “I feel personally fulfilled from this experience.”

Through this novel caregiver survey, we aim to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the Art in Mind program’s impact on both participants and their caregivers.

References

Fisher, Susan E., Burgio, Louis D., Thorn, Beverly E., Hardin, J. Michael. (2006). Obtaining Self-Report Data From Cognitively Impaired Elders: Methodological Issues and Clinical Implications for Nursing Home Pain Assessment. The Gerontologist, 46(1), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/ geront/46.1.81

Fry, M., Elliott, R., Murphy, S., & Curtis, K. (2021). The role and contribution of family carers accompanying community living older people with CI to the Emergency Department: An interview study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(7–8), 975–984. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15954

Hamilton, J. (2024, February 6). The James Museum Launches Art in Mind: An Innovative Initiative for Adults with Dementia. St Pete Catalyst. https://stpetecatalyst. com/w/the james-museum-launchesart-in-mind-an-innovative-initiative-foradults-with-dementia/

Meet me at MoMA. (n.d.). Meet me at MoMA. https://www.moma.org/visit/accessibility/meetme/

Philpin, S. M., Jordan, S. E., & Warring, J. (2005). Giving people a voice: Reflections on conducting interviews with participants experiencing communication impairment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50(3), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.13652648.2005.03393.

The James Musem. (2024, November 7). Art in mind. The James Museum. https:// thejamesmuseum.org/artinmind/

Williams, R. (2010). Honoring the personal response. Journal of Museum Education, 35(1), 93- 102. https://doi.org/10.1080/105 98650.2010.11510653

Appendix A

Art in Mind Smiley Face Survey

Appendix B

Art in Mind Caregiver Survery

Below are a number of questions regarding your experience today at the James Museum. Please fill in a number indicating how much you either agree or disagree with the given statements.

Rating Scale:

1= Disagree, 2= Neutral/Unsure, 3= Agree

1. I feel a stronger sense of community after this experience.

2. My mood has improved after this tour.

3. I enjoyed taking part in conversations surrounding the art.

4. My companion enjoyed the experience today.

5. I would recommend these activities to other caregivers and groups.

6. My companion’s mood improved throughout the experience.

7. My companion and I talked about memories during this tour.

8. I feel closer to my companion after this tour.

9. I would come back to the Art in Mind tour again.

10. I feel personally fulfilled from this experience.

Scoring Guidelines: Items should be summed. A higher score indicates higher levels of program efficacy.

Ren W.

Three weeks. That’s how long it’s been since my last dose. Not by choice—like hell, I’d put myself through this on purpose. But the hoops I have to jump through just to get a simple refill are ridiculous. It’s like my state wants me to die. I knew quitting cold turkey would be bad, but knowing doesn’t make it easier. The headaches started first, sharp and mean, little knives at my temples. Then the nausea hit with relentless, rolling waves that made food a distant memory. Sleep? Forget it. My body twitches and burns, skin too tight, brain too loud. Everyone warns you about withdrawal, but what do you do when there’s no other option?

Calling the pharmacy is an exercise in futility. I wait on hold, fingers drumming against the counter, only to be met with the same robotic voice: Your prescription has been approved, but processing times may vary. How long? No one can say. A day? A week? A month? Might as well be forever. And yet, I keep calling. Keep trying. Even though the answer never changes. Without my meds, life turns into a stalled out car, sputtering, jerking, going nowhere fast. Maybe I do depend on them. Maybe I need them just to function. But there’s no shame in that. I remember reading something once about how meds are like fuel for brains like mine that keep the engine running. Can’t recall exactly how it was worded, though. Funny how memory slips when your body’s in full-on revolt. The worst part is the exhaustion. Not just tired but a bonedeep, aching fatigue. My hair’s thinning, my stomach’s in knots, and even the simplest tasks feel impossible. Money’s a joke at this point. A cruel one. I blew over a hundred bucks at some rigged fair game, just desperate to win something. Anything. Watched the bills disappear like they meant nothing, like I wasn’t gonna feel that loss clawing at me later. Walked away with empty pockets, forcing a grin like I wasn’t on the verge of losing it in the middle of a crowd.

Oh, right. Meds. That’s what I was talking about. See what happens without them?

School without meds is wading through wet cement. And money’s always gnawing at the back of my mind. Groceries cost a fortune, so I just...don’t eat sometimes. It’s not the best plan when I’m already running on fumes, head bobbing in class, and words blurring together on the page. But hey, money’s just a revolving door anyway, right? Sleep’s a gamble, too. Six hours if I’m lucky. Mornings come too fast, and with no ride home till late afternoon, the day stretches on forever. Between trying to keep up with school, grabbing vending machine snacks

without breaking the bank, and squeezing in time for friends, it’s a miracle I haven’t just shut down completely. They say therapy’s supposed to help, but when I sit there, staring back at my therapist, the words just…stop. They pile up in my throat, stuck behind a wall I can’t seem to break through. So I nod, smile, talk about the good stuff, curating a highlight reel instead of telling the truth. I brought that up once, admitted how I hold back. My therapist just shrugged, said it’s normal. But it doesn’t feel normal. It gnaws at me. I want to open up, I really do, but it’s like I’m wired to hesitate. Even with people who are supposed to feel safe, it takes forever to let them in. And when I finally try, my thoughts scatter. Stringing them together feels impossible. You’ve probably noticed by now. Half the time, I can’t even tell a proper story. If you ever find yourself where I am—stuck without medication—it’s a deeply isolating experience. For me, it felt like everything was slipping through my fingers. I cherished the days when I had them, when things felt steady, manageable. Without them, I was scared, desperate. I lashed out at people who didn’t deserve it, turned that frustration inward when there was nowhere else for it to go. Time lost meaning; days blurred into exhaustion, sickness, and loneliness. It’s hard when no one really understands—maybe one person will, if you’re lucky. Medication has been life changing for me. It’s given me a stability, a sense of self I couldn’t hold onto before. If you rely on them too, I hope you never have to go without. But if you do, please know that you’re not alone. The worst part is people telling you you’re incoherent. I spill my guts, lay everything out raw, and they act like it’s fiction, like I’m just being dramatic. They’ll say they don’t understand, like that’s my fault, like putting this into words isn’t already the hardest thing in the world. But that’s why I’m writing this. I need you to listen. Not correct me. Not tell me what I’m doing wrong. Just listen. Because I might never change, and I might never get this all out the right way, but I’ll always be trying. Even if it takes me a lifetime to figure out how to say it right.

Matthew Lim

Currently the number of people diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease is 8.5 million, but this number is expected to increase to 12 million people in 2050 (Soilemezi 2023). Not only do individuals experience non-motor symptoms, but there is a huge social need which makes up a burden for the patient and families. There have been studies showing the economic burden of neurological diseases such as personal, intangible, psychosocial, and indirect costs due to these diseases (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). However, a big concern for individuals and caretakers is the social burden of taking care of people with neurological disorders due to the extreme stress and social effects it can have. Communities and individuals must adjust their everyday lives to accommodate for this change of daily routine and life. People must learn to cope and adjust with the negative aspects regarding the healthcare system like difficulty with getting treatment or limited access to specialists. Many different communities have systems in place to help individuals with these conditions, but it can be limited in many ways. Differing societal perceptions due to cultural frameworks influence the ethical decision-making approach to care for individuals with neurodegenerative disorders (e.g. Alzheimer’s and Parkinsons) in residential homes and community settings. Culturally different communities deal with neurodegenerative disorders through the process of Advance Care Planning, and this system has been under development in western nations over recent years.

SECTION ONE: Communities Dealing with Neurodegenerative Disorders and Addressing the Problem

Community Support of People with Parkinson’s Through Caregivers

Neurodegenerative disorders involve not only the person inflicted but the caregivers or family members. This situation cannot be handled alone and requires a support system in the community to achieve successful results like sustainable long term care and a better quality of life. One study examined individuals with Parkinsons and family caregivers from Denmark, Norway, and the United Kingdom. This study

provided important information about the support or lack thereof from health services in their respective countries. The participants of the study explained healthcare professionals who specialize in Parkinson’s disease were able to provide beneficial support as they didn’t have a complete understanding of what each family needed (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). This point was reaffirmed in each family, showing how influential professional help was and how reliant these families were on this aid for themselves and the person with Parkinson’s Disease. It illustrates how general healthcare services and other external social services were limited in how helpful it could be for the families. Many of the people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) themselves outlined how the clinical expertise and the support they received from health care specialists like neurologists, physiotherapists, and PD nurses were helpful sources of support. People with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPD) believed these specialists were helpful for “managing their individual symptoms, treatments and addressing their concerns. [A]ccording to many [PwPD] and [Family caregivers], more flexible access to PD specialists was necessary to respond to symptoms that arose unexpectedly” (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). Family caregivers are reliant on the professional advice of health specialists, and the inaccessibility of these services inhibits the much needed guidance for assisting PwPD.

Caretaker’s Responsibility when assisting People with Parkinson’s

Another main concern for communities with people with Parkinson’s disease is who the responsibility is to take care of the person. “Many people with Parkinson’s Disease in the United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway and Spain considered themselves to be jointly responsible in the management of their condition and making decisions to adapt their everyday activities” (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). The family caregiver shoulders a huge responsibility as they spend the most time managing the PwPD’s everyday life. Especially because most family caregivers are emotionally connected to the person with Parkinson’s disease, it is difficult to not be concerned with any physical or emotional changes the person may undergo during the process. Many family caregivers “in all four countries indicated that cognitive changes in PwPD gave them much greater cause for

concern... cognitive changes were reported to be the most difficult aspect to live with” (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). As the person with Parkinson’s health deteriorates, many of the caretakers undergo emotional tribulation as they slowly lose someone they love. The slow degradation is the cause for much of the turmoil on caregivers as it is a gradual process, and extremely heartbreaking to witness firsthand. In addition, these concerns were also illustrated in a study in which the family caregivers felt much concern and uncertainty about the future of their person with Parkinson’s. The study showed they felt it was essential for family caregivers “to receive support to maintain their health and emotional well-being, and their ability to help” (Navarta-Sánchez 2023). Therefore, it is shown in western nations of Norway, Spain, Denmark, and the United Kingdom to put an emphasis on establishing systems in which the caregivers can receive the help they need in order to maintain their current condition and well-being.

Defining Advanced Care Planning