RESTORE PAY NOW

Junior doctors strike for better pay and conditions

Disparity of care

How mental health services lag behind Life and death

COVID and terror attacks, through the lens of intensive care

The agenda

GPs battle against attempts to undermine them

The magazine for BMA members Issue 53 | March 2023

the doctor

Phil Banfield, BMA council chair

Colleagues, none of us take strike action lightly. But in light of the Government’s continued refusal to resolve the legitimate concerns of a profession desperate to care but driven over the edge, we have been left with no other choice.

I am proud to support junior doctor colleagues across the country who told ministers, in the strongest possible terms, that enough is enough. Their unified and powerful demand for full pay restoration must not be ignored.

And last month more than 17,000 NHS consultants in England also signalled their despair and frustration loud and clear in voting decisively for strike action in a consultative ballot.

If the Government does not outline serious proposals about how it intends to fix pay, pensions and the broken pay review process, the BMA will proceed to a statutory ballot over industrial action by consultants.

This crisis point has not come out of the blue. The BMA has long warned Government about the desperate state of the NHS – and the effects underfunding, pay cuts and pensions-tax traps are having on services and recruitment and retention of staff.

We can’t allow patients to suffer any more. We can’t allow the Government to continue driving staff away, slashing services and leaving doctors in working conditions which lead them inextricably to burn out. You and your BMA will not stand by any longer. We are acting together to protect our members – and to advocate for our patients.

In this issue of The Doctor we report from the junior doctors’ picket lines in England, speak to doctors from Ukraine one year on from the beginning of the Russian invasion and continue to tell the true story of what life is like for GPs who have been subject to so much vitriol from the media and politicians, despite working harder than ever. We also interview intensive care consultant Jim Down about his new book.

We publish the first in a series of pieces investigating the state of NHS mental health care in England. The first, in-depth, piece in our ‘paucity of esteem’ series combines exclusive original data and analysis of NHS statistics with heart-breaking human stories which paint a stark picture of the effects of rocketing demand and dwindling resources on patients, families and a broken and beleaguered workforce.

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheBMA

02 the doctor | March 2023

Welcome

In this issue 3 At a glance Consultants may ballot for industrial action 4-9 The other, lesser health service Patients with mental health issues face huge gaps in provision 10-13 A harsh spotlight The political pressure GPs fight on top of burgeoning workloads 14-15 Out in force Junior doctors strike over pay 16-17 A year on Ukrainian doctors’ struggle after the Russian invasion 18-21 As life unfolds Terror attacks, a rail crash, and COVID, through the eyes of an intensive care consultant 22 Your BMA Making the ARM more representative

MATT SAYWELL

Consultants may ballot for industrial action on pay and pensions

Consultants are to ballot for industrial action from next month if the Government refuses to fix issues raised with pay, pensions and the pay review process.

The move towards a formal ballot follows a consultative ballot in which 86 per cent of consultants in England indicated they would back strike action, from a turnout of more than 60 per cent. Results were shared with the BMA consultants committee, which voted unanimously to hold a formal industrial action ballot if the Government does not meet their asks.

The Government has been given until 3 April to respond with specific proposals to solve the combined problems of eroded pay, a punitive pension scheme and pay review process.

If the Department of Health fails to make a meaningful offer by then, a six-week ballot will open on around 17 April.

If a majority of BMA consultant members vote in favour with a turnout of more than 50 per cent, strike action will go ahead. That will mean consultants providing bank holiday service on weekdays, with emergency and urgent care unaffected.

An accelerated timetable has been produced so consultants can join the wider round of ongoing NHS strike action. Junior doctor members of the BMA began their walk out over pay and working conditions for 72 hours from 6:59am on 13 March. Members of the Royal College of Nursing have already taken strike action, as have physiotherapists and paramedics.

Since 2008/09 consultants have experienced a near 35 per cent average fall in real terms take-home pay, which the BMA equates to working four months of the year for free.

The BMA has been calling on the Government to reverse its decision to freeze the LTA (lifetime allowance) on consultants’ pensions to April 2026, and instead provide a more flexible solution.

The LTA imposes a limit on the total value of a

pension pot, which was previously indexed to the consumer price index. Going over the limit triggers an additional tax charge meaning consultants can be punished for gaining annual increases, getting a promotion, taking on additional responsibilities and doing extra shifts.

Consultant members of the BMA have been asked to update their details with the union ahead of the proposed ballot dates to ensure those who have changed role or workplace recently receive their ballot.

Vishal Sharma, chair of the BMA consultants committee, said: ‘In my 25 years in the NHS, I have never seen consultants more demoralised, frustrated and in despair over this Government’s refusal to support the NHS workforce and the patients they serve.

‘Consultants lead the teams which provide expert care and treatment to patients, they train future doctors, they innovate to improve patient services and lead medical research. Millions of patients benefit from the expert care and treatment that consultants provide.

‘Despite these significant contributions, the Government is refusing to listen to consultants’ concerns, driving many out of the NHS entirely. If the Government

truly wants to get the NHS back on track and tackle the record waiting lists, it must support the consultant workforce.

‘Our position is clear. We will not allow the Government to continue to degrade consultants’ pay and pensions. This is having a hugely detrimental impact on patient care as staffing numbers plummet and things will only worsen unless we take a stand.

‘Strike action is always a last resort and we have set out a clear timeline for the Government to put a serious proposal on the table. It is within the Government’s gift to pay doctors fairly for the crucial, lifesaving work they do and there are clear, straightforward solutions to fix the punitive pensions tax rules.

‘For example, the Government can implement a tax unregistered scheme, similar to the one it has already done for judges in order to enable doctors to remain working in the NHS. Our door remains open; it is not too late to prevent consultants from acting. But if the Government refuses to propose a workable solution, our members have made it clear that they are prepared to strike.’

bma.org.uk/thedoctor the doctor | March 2023 03 AT A GLANCE

SHARMA: Consultants are demoralised

PAUCITY OF ESTEEM

As one doctor puts it, imagine presenting with a breast lump and being told to come back in three years to ‘see how you’re doing’. And yet patients with severe mental illness are facing huge gaps in provision or waits that worsen their conditions and risk their lives. The health service as a whole is under intense pressure, but, in the first part of a new series, and with exclusive data, Peter Blackburn and Ben Ireland examine why the disparity between physical and mental healthcare is so stark

THE OTHER, LESSER HEALTH SERVICE

‘She was bright, kind, caring – and had a real sense of justice and wanting the world to be a fairer place.’

Moira Durdy is remembering her daughter Jess – a talented young engineer who died by suicide aged 27. Jess had a history of mental health difficulties but kept her struggles to herself. ‘She loved us, and we loved her to bits, but I kind of always had a feeling there was a bit of her that was hidden,’ mum Moira says.

Jess died on 16 October 2020 while at a mental health crisis house in Bristol, having moved in five days before. She was referred there rather than to a scarce psychiatric inpatient unit bed because she was struggling with increasingly intense and intrusive suicidal thoughts. Jess had previously been prescribed medication in general practice and had a private counsellor.

A serious-incident report found failings in her care, including that demand on services had ‘exceeded human capacity to perform all tasks’.

It also found ‘poorly defined’ strategies around escalation

of risk and a care system ‘losing clarity under pressure’. It also reported a lack of links between primary and secondary care.

Ms Durdy says Jess felt no one or nothing was helping her and ‘pushed around from one person to another, having to repeat herself all the time and not really getting anywhere’ until she was eventually in absolute crisis.

For Ms Durdy, her daughter’s interactions with health services before her death expose a crisis in mental health services which can now be seen across the country: GPs managing patients too complex for primary care, a lack of communication between primary and secondary care, underfunded specialist services with workforces whose training hasn’t been invested in and insufficient inpatient beds.

Problems are exacerbated in a health landscape in which institutions have been through countless reorganisations and restructures, where reform has infrequently been followed by investment and where oversight and responsibility have been fractured or lost.

The Doctor has spoken to patients and families unable to access specialist support until they are in absolute crisis and often forced to break the bank for private care. Doctors describe a system and workforce stretched to

04 the doctor | March 2023

MOIRA DURDY AND DAUGHTER JESS

‘Countless restructures and where oversight and responsibility have been fractured or

lost’

ANDY BAINBRIDGE

PAUCITY OF ESTEEM

PAUCITY OF ESTEEM

breaking point.

Royal College of Psychiatrists presidentelect Lade Smith likens NHS mental healthcare in 2023 to telling someone with a lump on their breast to ‘come back in three or four years’ time and we will see how you are doing’. When they return, she says, that patient has stage-four cancer.

The Doctor has obtained exclusive data which shows a massive increase in mental health patients presenting at emergency departments in crisis and then trapped there for days or even weeks.

BMA consultants committee mental health lead Andrew Molodynski says the stark statistics show increasing numbers of people are forced into emergency care because of a paucity of specialist services across England. As a result, patients are left in environments which are unfit for purpose and often ‘hugely distressing’.

Our data shows the number of mental health patients waiting in acute hospital emergency departments for at least 12 hours more than quadrupled from 2016-17 to 2021-22. And the figures are still rising. In the space of just seven months from April to October 2022 the numbers had surpassed the annual total from the previous year.

Waiting times soar

In 2016-17, there were at least 1,962 waits of 12 hours or longer at 41 trusts which gave data for that year. In 2021-22 those numbers rocketed to at least 8,971 waits of 12 hours or more at 61 acute hospital trusts. In the first seven months of 2022-23, there were at least 9,504 at 59 trusts.

Many mental health patients spend significantly longer than 12 hours waiting for

more appropriate care or assessment. Since April 2016, at least 421 people waited more than 72 hours. One patient was trapped for 744 hours – 31 days – at a London hospital in 2021-22.

The numbers are likely to be much higher as around half of trusts had failed to respond to a freedom of information request at the time of publishing.

Experts are united in their damning assessment of this situation.

Cambridge emergency medicine consultant Adrian Boyle tells The Doctor : ‘If you go to a mental health hospital, it’s calm, it’s ordered, it is a recovery environment [whereas] that’s not the environment I work in.’

Dr Boyle, president of the RCEM (Royal College of Emergency Medicine), says patients ‘turn up because alternative access to help is not good’.

Marcus Bicknell, a Nottingham GP with a specialist role in secure mental health and addiction, described the environment at the Queen’s Medical Centre’s emergency department as at times ‘like a World War One casualty station’.

The BMA has also analysed a vast array of NHS datasets to assess the crisis in mental healthcare. Our analysis paints a stark picture of rising demand, a workforce which simply isn’t big enough and funding and resources nowhere near matching the need in communities.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of mental illness in England had been slowly and steadily rising. The estimation of the prevalence of common mental disorders, conditions such as anxiety or depression, among adults aged 16 to 64 had risen from 18 per cent in 2000 to 19 per cent in 2014. Updated figures are due in 2023-24.

Evidence suggests rates of mental illness may be growing faster among children and young people than adults. Between 2017 and 2022 rates of probable mental disorder increased from around one in eight young people aged seven to 16, to more than one in six. For those aged 17-19, rates increased from one in 10 to one in four.

The numbers of people seeking treatment have risen even more quickly. There are now more than four times as many children and young people in contact with mental health services as there were seven years ago.

06 t he doctor | March 2023

‘The sense of frustration and unhappiness is palpable. We’ve had members of our team in tears at times’

MOLODYNSKI: Patients forced into emergency care

Rejected referrals

Mental health services in England received a record 4.3 million referrals during 2021 alone, up from 3.8 million in 2019. Many of these patients aren’t receiving the care they need. Doctors across the country say the number of those referrals being rejected or signposted elsewhere, rather than accepted into secondary care, are rocketing. Secondary care is overwhelmed by demand and GPs are burdened with managing increased risk and complexity.

Hampshire GP partner Emma Nash says demand is increasing and that around a quarter of the circa 100 same-day requests for appointments her practice receives are mental health-related. Hertfordshire locum GP Neena Jha reports a similar ‘explosion’ in demand.

GPs increasingly find their hands tied. Dr Jha says rejected referrals are often accompanied by a suggestion that ‘if it changes or gets any worse then tell the patient to go to A&E’.

Things are similarly difficult in secondary care. One child psychiatrist in the south-west told The Doctor : ‘I’d hate to work in the referrals team. There is a huge increase in the number of referrals, but there are less staff than there were, which can only go in one direction.’

The Doctor spoke to dozens of health professionals about the drivers of these increases. There is an acceptance that reduction in stigma around accessing mental health services is likely to be one reason, but most felt the state of society – where the welfare safety net has fallen away, and society is becoming increasingly unequal – is a major factor.

Dr Molodynski, a consultant psychiatrist in Oxford, adds: ‘Austerity has stripped away a lot

of the softer support in society.’ Dr Jha says the effect of this is her patients now often needing mental health care just to ‘cope with life’.

It is clear COVID-19 itself has caused huge damage too – whether through increasing isolation and loneliness, the anguish of longCOVID or the exacerbation of so many existing inequalities in society. Consultant psychiatrist and Dean of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Subodh Dave, describes an ‘increased psychiatric morbidity’ as a result.

Analysis of NHS data shows the mental health workforce is simply not big enough and that it is not rising at the rate needed to meet demand or the expected increase in demand on services.

For example, the number of people in contact with CAMHS services has increased by 310 per cent since April 2016 while the number of FTE (full-time equivalent) doctors in child and adolescent psychiatry has only risen by 12 per cent in the same time. On top of this, the average vacancy rate across England for doctors working in NHS mental health services is high, with around one in seven planned FTE roles vacant. Many more are filled with temporary staff.

The average vacancy rate is even higher within nursing roles, at 19 per cent in England, as of last September.

One inpatient child psychiatrist working in a tier 4 unit in England told The Doctor their service had a total of five consultant vacancies but that vacancies were ‘constantly’ advertised with ‘no applications’ forthcoming. Continuity of care is often affected, as a result.

Professor Dave describes a ‘vicious cycle’ of poor pay and working conditions which leaves staff taking on more responsibility on wards

‘There is a huge increase in the number of referrals, but there are less staff than there were’

bma.org.uk/thedoctor the doctor | March 2023 07

‘The threshold for accessing services gets higher and higher every year’

JHA: GPs overwhelmed

SMITH: The issue is ‘chronic’

PAUCITY OF ESTEEM

and in clinics and, ultimately, burning out. He says the Government needs to ‘invest in the wellbeing of the workforce’ urgently.

Dr Smith describes the problem as ‘chronic’ – and says many trusts, with consultant vacancies at 50 per cent, are forced to turn to locum staffing at ‘far greater’ expense, which costs the NHS around £3bn a year.

‘If you’ve got a significant proportion of locums who come in, do the sessions and leave, then leave without helping build and develop the service quality, gradually the quality of the service is not going to improve,’ she says. ‘That’s really concerning.’

Staff in tears

The combination of surging demand and dwindling staff numbers is brutal for staff. One doctor says: ‘It’s impossible to not take it home. You just have this level of exasperation… “I really want to help you, but I can’t”.’

Dr Molodynski adds: ‘The sense of frustration and unhappiness is palpable. We’ve had members of our team in tears at times.’

Funding is a critical issue. While the Government has committed more spending to mental health – at least £2.3bn a year by 2023/24, it says – it is not likely to be anywhere near enough. In recent years, spending on mental health has increased at a slower rate than overall NHS expenditure and the proportion of the NHS England budget spent on mental health has fallen since 2016/17.

Professor Dave says ‘we’re still playing catch up’ with resource and highlights a lack of beds as an immediate effect of lack of resource.

Bed numbers have fallen significantly under successive governments. Learning disability and mental illness beds have seen the largest

reduction, of 69 per cent and 23 per cent respectively, since 2010/11.

Professor Dave says: ‘I have been on call when there has been no bed available nationally. There are times when you realise that unless somebody is being detained there’s no hope of finding a bed.’

The effect on patients is brutal.

Dr Molodynski says: ‘The more demand there is for the same amount of services means the threshold for accessing services gets higher and higher every year. People who would have been able to access, for example, talking therapy, 15 years ago, in many parts of the country would get nowhere near it these days.’

Two-tier system

Behind every number and every target are thousands of real lives blighted by this crisis.

Saskia Homer, a civil servant from Wales, is familiar with the effect under-resourcing has on patients. Saskia lives with autism, depression and agoraphobia and has attempted to take their own life on ‘numerous’ occasions.

Their interactions with mental health services have been torturous – including a three-year waiting list for autism support, another lengthy waiting list for specialised sexual abuse support, a 111 call handler who described them as not sounding ‘very suicidal’ and a ‘frightening’ inpatient stay in a psychiatric hospital. They also told The Doctor they fear hospitalisation owing to the likelihood of being an inpatient miles away from home in Wales or their parents in Scotland.

‘There’s a disconnect between waiting lists and people’s actual lives.’ Saskia says. ‘The real issue is the waiting times.’

Saskia adds: ‘You don’t feel like you’re going to be helped… You feel like you’re going to be fobbed off from service to service… It makes you lose trust and faith in the mental health system.’

Doctors are also concerned about the creation of a ‘two-tier’ care system with increasing numbers of people turning to private care for assessment, diagnosis and treatment.

Father-of-two Simon, from the south east of England, felt he had no other alternative when one of his daughters, who was struggling with depression and attending school, was told the waiting list was likely to be years rather than days or weeks. Simon paid for counselling and an autism diagnosis, which then unlocked

08 the doctor | March 2023

DAVE: Still playing catch up with resources

‘There are times when you realise that unless somebody is being detained there’s no hope of finding a bed’

The state of mental healthcare in England

4.3m 2021

BMA emergency department data: More than 350 per cent rise in number of mental health patients waiting 12 hours or more in emergency departments from 2016/17 to 2021/22

350% RISE

3.8m

2019

Resource:

General demand: Record 4.3 million mental health referrals in 2021. Up 13 per cent from 3.8 million in 2019.

The BMA has called for a doubling, plus accounting for inflation, of the extra £2.3bn announced for mental health in 2019

Workforce: One in seven planned FTE doctor positions in mental health are vacant

1 in 7 VACANCY RATE

One mental health patient waited 744 hours (31 days) in A&E at a London hospital in 2021/22

744 hrs WAIT IN A&E

other avenues of support, but had to fork out thousands of pounds in savings.

Simon says: ‘It must be a dreadful situation to be in where you know that something may be helpful and possibly transformational, but you can’t access it purely because of the cost. I think services need to be far better resourced. People need access to staff like clinical psychiatrists much faster.’

Communities are littered with families such as Simon’s. Reflecting on these stories, the child psychiatrist in an inpatient tier 4 unit says the effects of these delays can be ‘lifelong’.

The BMA is calling on the Westminster Government and NHS England to support mental health services – demanding an expansion of the workforce, ‘robust and frequent’ collection of data, an action plan to attract more clinicians and increased exposure to psychiatric specialties during training.

Investment essential

The BMA is also urging ministers to protect mental health services against inflation and for a promised £2.3bn increased funding to be brought in line with inflation and then doubled to meet demand. This investment, it says, must come alongside support for primary care, public mental health, mental health

research and estates.

Finally, the association is urging an expansion of inpatient mental health beds in England to eliminate inappropriate out-of-area mental health placements.

Appealing for urgent change, Dr Molodynski says: ‘People with mental health problems are enormously varied, but at heart, they have a shared characteristic in that they are in mental health crisis or have mental health problems.

‘If there was any other group of people who had a shared characteristic and we said to this group of people that we’re going to tolerate them having manifestly worse services than other people, tolerate them living on average 15 to 20 years less than the people they live next door to when other factors have been controlled for, we’re going to tolerate them having access rates to evidence-based and NICE guidance-approved services of as low as 20 to 30 per cent, it would be absolutely unthinkable. It would be very clearly a civil rights issue.

‘But for some reason, in this country, and in most countries, we’ve come to a position where we think that’s OK.’

It is abundantly clear, from his testimony and that of other doctors and patients, that it’s not OK.

for

bma.org.uk/thedoctor the doctor | March 2023 09

‘Manifestly worse services than

[other] people’

A HARSH SPOTLIGHT

GPs are prepared for just about anything that comes through their doors – but a politically motivated attempt to undermine the way they work has left them badly shaken. The Doctor continues its study of the pressures facing general practice

10 the doctor | March 2023

SIMON BOLTON

HUSSAIN: Politicians unhelpful

London

GP principal Farzana Hussain sometimes feels like she is part of a general practice tribe that is potentially facing extinction.

As the single-handed principal at the Project Surgery in Newham, east London, Dr Hussain has been a fi xture within her local community for almost 20 years.

Nestled within a housing estate and adjacent to the path of the rails of the District and Hammersmith and City tube lines, the practice cares for a patient list of just 5,000,

their grandchildren. It’s really family medicine and that’s very satisfying for me.’

False narrative

The Project Surgery was originally founded via an urban regeneration fund new deal for communities.

Since 2013, the surgery has operated on a telephone-triage approach to consultations, something which allowed the practice to meet the challenges of COVID when the pandemic struck three years ago.

With the surgery opening at 8am, Dr Hussain and her colleagues, a locum and a salaried GP, received 65 incoming calls and manage 42 patient consultations between them on the day I visited, while also processing lab links, bloodtest results and electronic prescriptions.

Indeed, just staying on top of and responding to the various emails arriving in the surgery’s inbox takes up at least an hour of Dr Hussain’s daily work schedule.

are just really lazy”.

‘The politicians certainly didn’t support us in countering this narrative. Indeed, at the end of the second wave they started talking about benchmarks for how many face-to-face consultations we should be having.’

In the course of a telephone clinic, Dr Hussain speaks to one of her rare, older patients, a man in his 80s set to undergo an MRI, about the medication he is using to manage his pain.

Greeting her like a family friend, he speaks enthusiastically of Dr Hussain’s recent TV appearance and how proud he is of her.

The closeness of the doctor/ patient relationship is evident, yet Dr Hussain fears that part of the toxic narrative of GP surgeries not being accessible to patients is now being used to push a political agenda mandating increased levels of face-to-face appointments.

something Dr Hussain believes has allowed her to practise the type of family-doctor medicine she feels is becoming increasingly rare.

‘London is a young city and Newham is a young borough. Out of all my patients I’ve only got about 200 over 65 and I can honestly say that with at least 100 of them, I know what their front lounges look like, I know their children and

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

It is extremely frustrating therefore when she and her colleagues encounter accusations of GPs not being open and available in the press, among politicians and occasionally the public.

‘I think this whole narrative that the politicians and the papers have said about GP surgeries are closed, I think it’s been intentional,’ Dr Hussain says.

‘I think the public thought “oh, they closed the doors for COVID, but now we don’t have a pandemic, so GPs

‘This government wants to push access but my concern with that is [in doing so] are we actually giving people safety and quality care?’ says Dr Hussain.

‘If one of my patients says, “I’ve got hip pain”, and I know that her husband died recently, I know that that’s going to impact on her pain thresholds. That’s something that you can know instantly, if you’ve got that continuous relationship.

‘You can’t diagnose the cancer within fi ve minutes, you need the time to ask questions and do a really good consultation.’

By Tim Tonkin

the doctor | March 2023 11

GP PRESSURES

‘This whole narrative that the politicians and the papers have said about GP surgeries are closed, I think it’s been intentional’

Nottingham

Continuity of care is the key principle which runs through everything doctors do at the Elmswood surgery in Sherwood, Nottingham. During the course of one morning in January, Irfan Malik – one of the six partners at the practice – sees patients he has been treating for decades, families whose stories he knows like his own, and even one young adult he first assessed during her baby check 22 years ago.

That continuity is not just a relic of the profession’s past fortunately preserved here – it has been carefully cultivated with partners. The 9,000-patient practice is solely doctored by the six partners and registrars in training, who fight to prioritise

a culture led by staff wellbeing and the relationship between patients and doctors.

‘We call it an old school method,’ Dr Malik says. ‘We are probably atypical because we’ve got no vacancies – so many places are under-recruited. We are very lucky and over the years we’ve built up an excellent rapport with the patient population.’

Good relationships

The results of continuity are clear in this residential area, just north of the city centre: rates of admission to hospital are relatively low, even though the population here is ageing and patients are managed in primary care for longer with low referral rates because each partner specialises in interventions which would often be carried out in secondary care.

Beyond that, Dr Malik says doctors here are rarely abused and relationships with patients are excellent, despite concerning trends elsewhere in the country. The mainstream media – and government – narratives about general practice could not feel any further from the truth in Dr Malik’s

consultation room.

‘I know we are losing that continuity around the country, but luckily we’ve got it here. And as well as the medical side of things I enjoy the banter and the conversation, too… Talking to them about the football or the cricket is why I’m here as well.’

Dr Malik adds: ‘We hardly get any people kicking off here. The receptionists may have a slightly harder time because they have to put people into appointments but generally the patients are lovely.’

Evidence for the benefits of continuity of care is not difficult to come by, but anecdotally the effect is clear here, too. During the course of 16 patient consultations in one morning Dr Malik is able to deal with incredibly complex patient stories efficiently, but also with great humanity – his understanding of the histories and characters of his patients combined with a genuinely caring and inquisitive disposition, ensures discussion around, and reassurance over, a number of issues to take place in the space of just 10 precious minutes.

By Peter Blackburn

12 the doctor | March 2023

MALIK: Continuity of care is central

‘We’ve built up an excellent rapport with the patient population’

Belfast

We’re sitting in Ursula Brennan’s bright and modern room in Mount Oriel Medical Practice in south Belfast and an email pings. It’s confirmation from the Department of Health that yet another GP practice in Northern Ireland has effectively collapsed.

There had been hopes that a contractor would be found to take on Priory-Springhill surgery,

board decides to disperse the patients – essentially sharing them out among other practices – this puts an additional strain on all the GPs in a locality. Sometimes it will be enough to precipitate further practice collapses. ‘An extra 300 patients can make the difference between being viable or not viable,’ she says.

Locum demand

There are several GP-led mechanisms to support practices in trouble, including the Northern Ireland-wide Practice Improvement and Crisis Response Team. But too often the help available is just not enough to stave off collapse. A shortage of GPs means locums are like gold dust, further adding to pressures.

Public perceptions that GPs ‘haven’t been working’ over the course of the pandemic don’t help morale, says Dr Brennan, and sections of the media have consistently fanned the flames. ‘There’s a lot of talk of “part-time GPs” and people think we’ve not been working, and we’ve not been seeing people face-to-face,’ says Dr Brennan. ‘But we’ve never been away – and our workload continues to grow.’

the necessary funding,’ says Dr Brennan. ‘I can see it being five or 10 years until we get an MDT.’

This has an effect on recruitment, she adds. ‘If you were a young GP who wanted to stay in Northern Ireland – which is a diminishing pool – would you want to work in an urban area with a full MDT or would you work in an area without an MDT? If you were smart and savvy you would work where you have as much of the supported primary care team adjacent. It does impact on recruitment – and colleagues who have an MDT say it’s been a game changer.’

As with practices across the UK, Mount Oriel has moved to a system where consultations are initially conducted by telephone, with patients being called in to see a member of the team if required. By 9am, Dr Brennan’s morning surgery is already full and the afternoon ‘emergency’ slots are also filling up.

but this hasn’t been possible, so instead it was due to be passed over to the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust.

‘We’ve had 11 list hand-backs since April,’ says Dr Brennan, a GP partner and chair of Eastern local medical committee. ‘And so many other practices are one [GP] resignation away from disaster.’

When one practice hands back its contract, it can be a bit like a set of dominos. If the health

Lack of political leadership is adding to the pressure too. The latest collapse of devolution in Northern Ireland means there is no health minister to make vitally needed decisions, and measures that could help – such as a rollout of general practicebased multidisciplinary teams – have stalled.

‘I think our practice is one of the last on the route map to get an MDT [multidisciplinary team], but to be honest it’s a moot point, because we don’t have a health minister, and the civil servants may not be able to divert

Dr Brennan’s voice is invariably cheery when she calls the patients, and most sound pleased to hear from her – even when the news isn’t good. Several consultations in the morning merit a referral to secondary care, but there’s no prospect of anyone being seen any time soon, unless they are prepared to pay privately.

‘We’ve got the worst waiting times in Europe,’ says Dr Brennan, scrolling down a list showing waits for the Belfast Trust. These are truly shocking. An ‘urgent’ neurology appointment will be 157 weeks – and you can forget about ‘routine’ because it’s twice as long. Patients will also take several years to get a first appointment for orthopaedics, then wait a similar time to get the actual procedure. It’s a similar picture across the board.

By Jennifer Trueland

the doctor | March 2023 13

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

BRENNAN: Media fans the flames

‘We’ve never been away – and our workload continues to grow’

JENNIFER TRUELAND

OUT IN FORCE

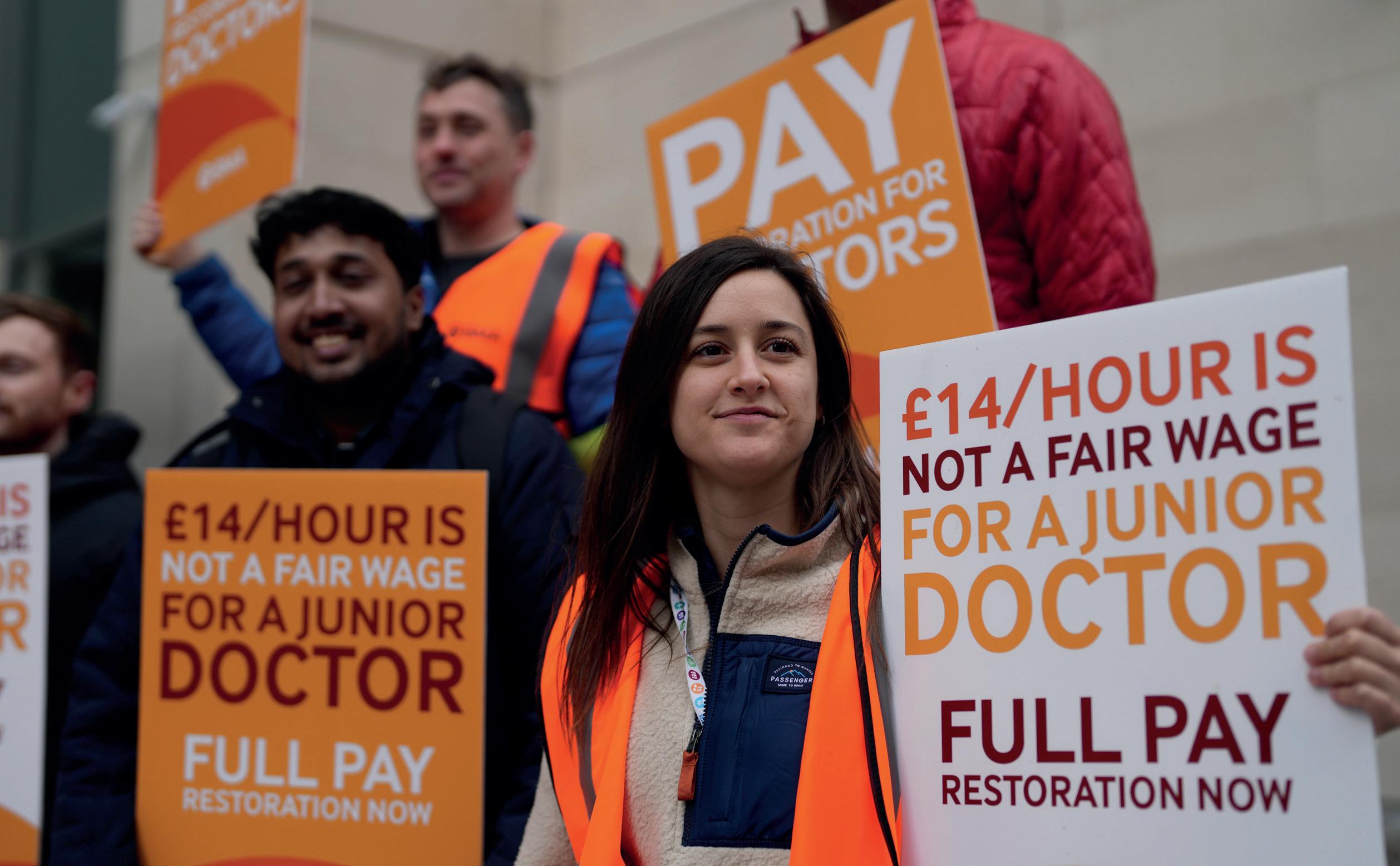

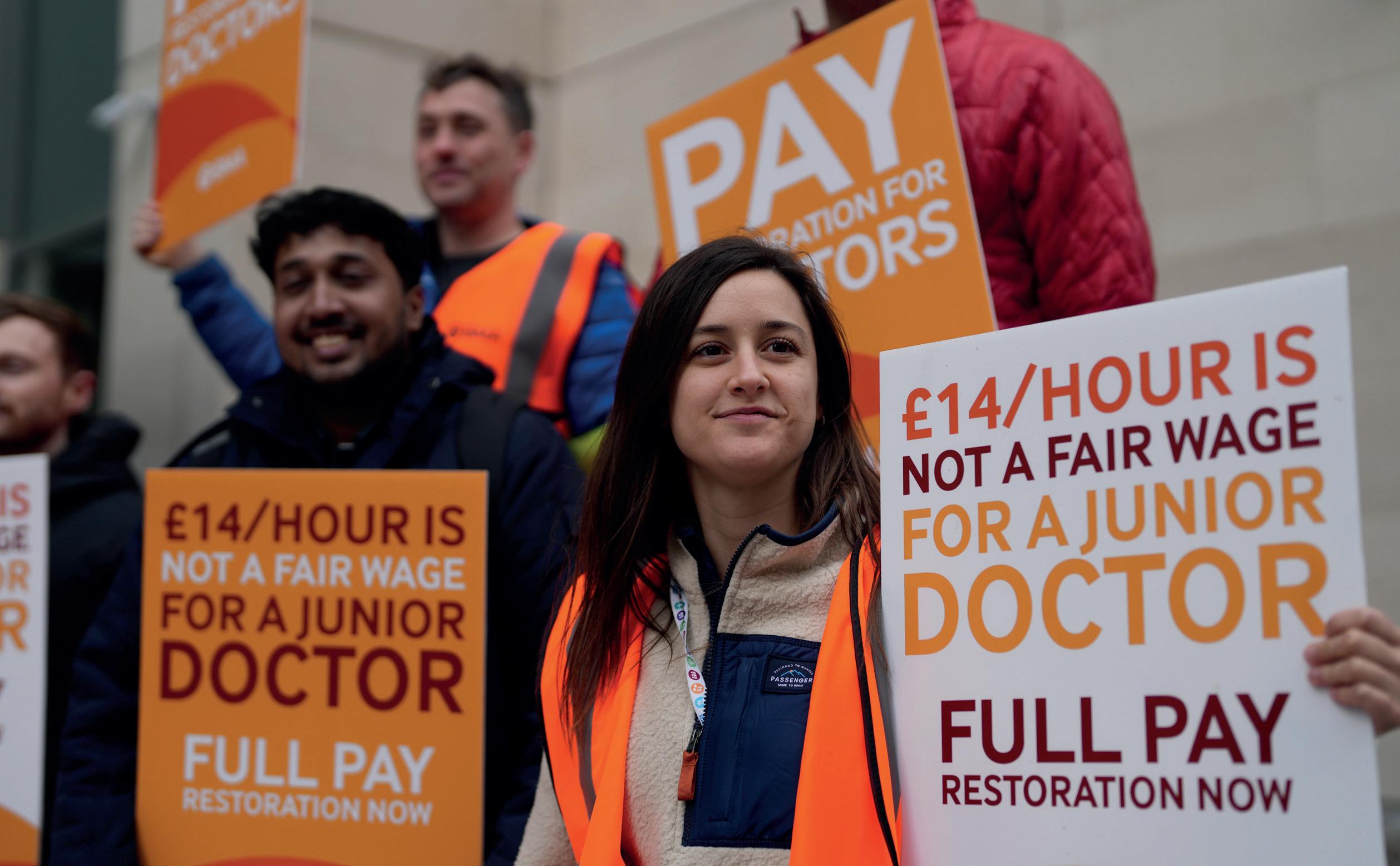

At the start of 72 hours of planned industrial action, junior doctors sent out a clear message to the Government as they seek to restore pay to 2008 levels and improve dire working conditions. Ben Ireland and Seren Boyd joined campaigners on picket lines in London and Brighton

It’s 7am on a chilly Monday morning at The Royal London Hospital, and strong gusts of wind are blowing rubbish around the entrance to the emergency department – one of the first doctors to arrive on the picket line suggests the scene could be a metaphor for the state of NHS working conditions.

Come 7.30am, the start of the official picket, doctors kitted out in BMA high-vis jackets and beanies hold placards explaining to passers-by that junior doctors can earn as little as £14 an hour – about the same as staff at Pret A Manger, who recently received their third pay rise in 12 months.

‘I would much rather be in work today,’ says Mike Andrews, a specialty trainee 2 in internal medicine. ‘I

don’t want to be here holding a placard in the cold. If [health secretary] Steve Barclay had made a meaningful offer, we’d be doing our jobs.’

Dr Andrews has seen colleagues depart, and says a recent show of hands suggested three quarters of doctors in the room would leave the NHS if strike action proves unsuccessful.

He fears: ‘If the strikes aren’t successful, we will see an exodus. It won’t be overnight, it will be slow and insidious, but this is what’s at stake. Doctors are incredibly employable, and could double our salaries working in management consulting – or move to Australia for a 50 per cent higher salary. Even medical graduates are not applying for foundation year roles, which is shocking.’

14 the doctor | March 2023

ANDREW BAKER

SOLIDARITY IN ACTION:

David Hobden, a respiratory ST6, notes how his pay as an foundation year 1 during the last junior doctor strikes in 2016 was only a little less than the current rate, despite living costs soaring since.

‘Doctors are feeling more and more undervalued and overworked, he says. ‘Five years ago, people were talking about taking a break – now people are talking about leaving.’

‘Sinking ship’

Louise Whitton, an ST1, changed to be a locum in order to ‘recover’ from a bruising period working through COVID during her foundation years and to give her time to apply for a training position in psychiatry.

She tells The Doctor : ‘It’s not just about our pay, it’s about making sure the hospital is staffed safely for our patients. We all feel like we’re on a sinking ship and we don’t want it to sink further. To avoid that, we need fair wages for everybody in the hospital.’

At Brighton’s Royal Sussex County Hospital, passing traffic honked horns in support, as doctors chanted ‘claps don’t pay the bills’.

Lara McNeill, a foundation year 3, says: ‘People are really struggling. Industrial action is the only option left on the table to make the Government listen. So many of my colleagues are going overseas and we are so understaffed that it is risking the care of our patients, which is really worrying.’

With inflation at budget-busting levels, NHS waiting lists at record highs and staff shortages across the board, morale has been systemically chipped away at.

Junior doctors voted overwhelmingly for industrial action in a ballot from mid-January until 20 February, with 98 per cent in favour from a 77.5 per cent turnout – an unprecedented mandate – calling on the government to restore pay to 2008 levels.

The BMA wrote to prime minister Rishi Sunak the week ahead of the action reminding him of repeated sub-inflationary pay awards which have seen junior

doctors’ earnings erode by 26 per cent since 2008. Newly qualified doctors are paid as little as £14.09 an hour.

It followed a long-awaited meeting with health secretary Steve Barclay the previous week which left junior doctors committee co-chairs Rob Laurenson and Vivek Trivedi frustrated when told by Mr Barclay that he had ‘no mandate’ to negotiate on pay.

They said: ‘As tens of thousands of doctors demonstrate the strength of feeling in the profession by taking a stand through industrial action, we would remind the Government that these strikes did not have to happen if they had come to the table with meaningful proposals.

‘The cost to the Treasury to offer a fair pay deal to junior doctors that would keep more of them in the NHS and improve working conditions is negligible compared to the billions wasted on inadequate PPE and the failed test and trace system during COVID.’

Sixty per cent of the 3,000 junior doctors responding to a BMA survey in late 2022 said their morale was low or very low. Junior doctors in Scotland, who have had a 23.5 per cent real terms pay cut since 2008, are to also separately ballot for industrial action from 29 March.

The Doctor went to press on the morning of the first day of action in England, with rallies and pickets up and down the country slated to finish at 6:59am on Thursday 16 March.

Visit bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion for the latest developments.

SUPPORT BMA MEMBERS

The BMA’s strike fund has so far raised more than £100,000 to subsidise members in serious financial difficulty who otherwise couldn’t afford to take part in any future rounds of strike action. You can donate at bmastrikefund.raisely.com

bma.org.uk/thedoctor the doctor | March 2023 15

Junior doctors on picket lines in London and Brighton

SEREN BOYD

ANDREW BAKER ANDREW BAKER

A YEAR ON

Two

Before Russia’s invasion last year, rheumatology consultant Inna Soldatenko led a contented and otherwise normal life.

The daughter of two doctors and the mother of two children, she was an accomplished physician as well as serving as an associate professor in her home city of Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine.

‘On 23 February last year, I remember finishing my clinic before picking my kids up from school and then coming home and cooking dinner.

‘After my children went to bed, I sat and worked on a lecture for my students on gastroenterology with a glass of wine.’

Hours later, however, members of the Ukrainian

military arrived at Dr Soldatenko’s home warning that, having spent months massed on Ukraine’s border, Russian forces numbering almost 200,000 strong had indeed begun to attack their homeland.

With Ukraine’s second city less than 50km from the Russian border, Dr Soldatenko was told her house needed to be requisitioned and fortified to serve as a defensive position against the advancing enemy forces.

‘That was scary,’ says Dr Soldatenko quietly.

Dr Soldatenko is just one of millions of Ukrainians whose life has been turned upside down because of Vladimir Putin’s illegal and internationally condemned invasion.

Crossing borders

To date, the UN states that more than 21,000 civilians have been killed or injured because of the fighting

Latest UN figures state that more than eight million Ukrainian refugees have been recorded in countries across Europe, with millions more displaced within their own country. The World Health Organization says there have been more than 800 attacks on healthcare professionals.

After leaving her home and moving herself and her children to a friend’s place nearby, it was not long before Dr Soldatenko and her family could hear the back-and-forth rattle of automatic weapons.

Within days, the fighting saw water and electricity supplies

16 the doctor | March 2023

doctors tell Tim Tonkin how the Russian invasion of Ukraine has had a profound effect on their lives

‘I understood that I needed to move, I was driving more than 26 hours to escape’

SOLDATENKO : With her family before and after their home was requisitioned, thanking the British public for their support

to many Kharkiv homes being cut off so, after joining with her parents, Dr Soldatenko took the decision to leave everything behind and flee from Kharkiv. She and her family crossed three borders.

‘I understood that I needed to move, I was driving more than 26 hours to escape,’ she says. ‘I didn’t have any plan. Didn’t have any goal, and I didn’t have any place in mind as to where I was going.’

Eventually reaching Bulgaria and kindly being put up in accommodation by one of her former patients, Dr Soldatenko found herself unable to work owing to her medical qualifications not being recognised.

Luckily the opportunity to seek shelter in the UK came when old friends living in London contacted her and offered to host and sponsor her and her daughters.

Now working in admin support in the rheumatological department at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich, London, Dr Soldatenko is waiting to sit her PLAB 1 exam, with the aim of getting her GMC registration. It is almost exactly a year since consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist Dennis Ougrin found himself thrust into action following the invasion of his homeland.

Already living and working in the UK, Prof Ougrin began raising tens of thousands in donations to acquire medical relief supplies, many of which he and his wife then transported themselves by car to the Polish/Ukrainian border.

A year on from the start of the war, Prof Ougrin remains involved in efforts to support Ukrainians here and in Ukraine, using his clinical skills to help some of the almost 29,000 Ukrainian children now in the UK. Despite his determination, he recognises Ukraine and its people continue to face a difficult and uncertain future.

‘It’s been the most difficult of times for Ukrainians, certainly since the Second World War,’ he says. ‘I don’t see how that conflict is going to end very soon at all, I assume it will carry on for as long as Putin is in charge. We are all preparing for years, maybe decades of this conflict.

‘It’s really important for one’s mental health to do something about this, and especially to do something about this as part of the group – as part of a community, a group of people so that’s what we’re doing and we’ll continue to do.’

Knowledge share

A member of the Ukrainian Medical Association UK, he and his colleagues, along with the support of the Ukrainian scouts UK, have assembled and dispatched thousands of first-aid kits to Ukraine.

‘We must have assembled and moved at least 10,000 of them to Ukraine, and they’re tactical kits, so the ones with those tourniquets and stuff like that,’ says Prof Ougrin.

With the UMAUK aiming to support and provide information to Ukrainian doctors already in the UK or

who are considering coming here, Prof Ougrin would like to see more done to support those doctors, like Dr Soldatenko, who are eager to share their skills and work in the NHS.

Following the outbreak of war last year, the BMA provided £25,000 to support humanitarian relief being carried out by the British Red Cross and Ukraine Crisis Appeal.

The association also continues to provide assistance and support to Ukrainian doctors who have sought shelter in the UK through its refugee doctor initiative and confi dential counselling and peer support services.

BMA representative body chair Latifa Patel says: ‘The determination of Ukraine to resist those who seek to take their freedom is humbling, as has been the solidarity and support shown by the international community to date.’

Dr Soldatenko believes Ukraine will win the war, but the ‘price of victory is really high’.

She adds: ‘As far as it’s possible I try not to think about what I lost or what I can expect in the future. I’m just trying to live for today and do my best for today.’

bma.org.uk/thedoctor the doctor | March 2023 17

OUGRIN: Preparing for decades of confl ict

‘I don’t see how that conflict is going to end soon at all, I assume it will carry on for as long as Putin is in charge’

EMMA BROWN

18 the doctor | March 2023 KALPESH LATHIGRA

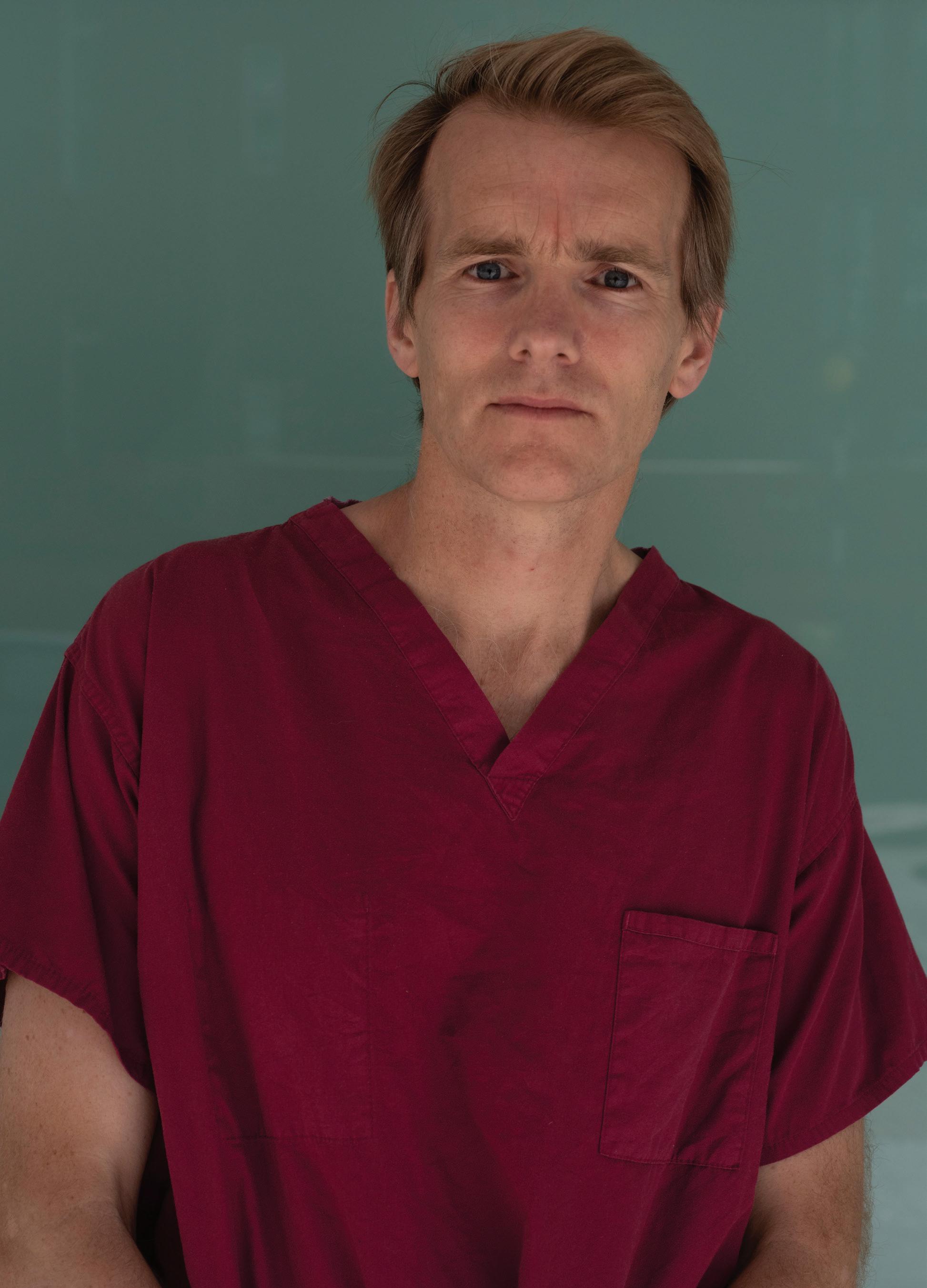

DOWN: 'You see the best of humanity'

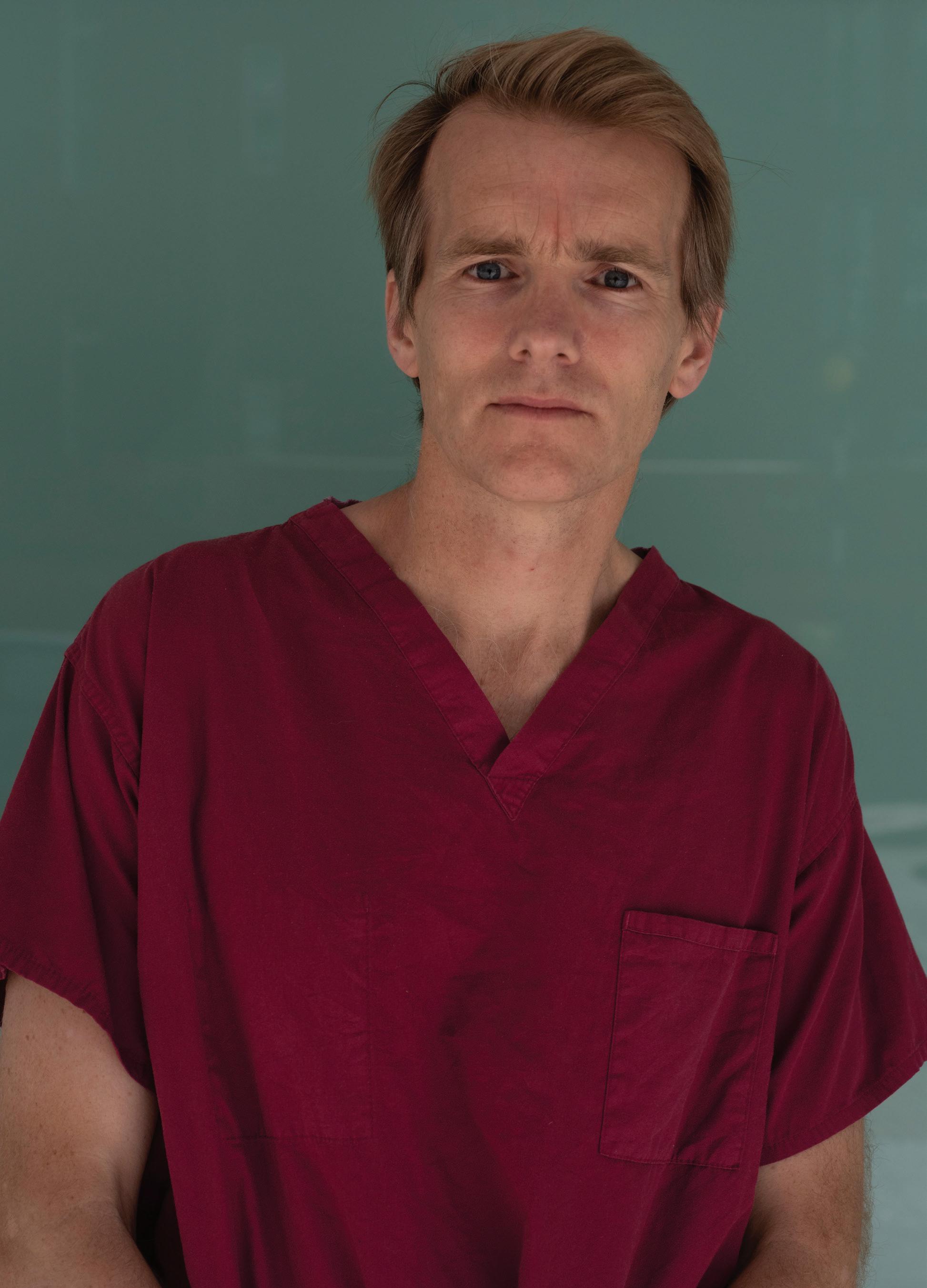

From the Alexander Litvinenko case to the London terrorist attacks and from being at the brutal heart of the COVID pandemic to the daily struggle for NHS beds, intensive care consultant Jim Down takes readers into the unit where life hangs in the balance in his new book. Peter Blackburn reports

As life unfolds

‘All of life is in ICU,’ Jim Down writes. And over the course of around 230 pages, he absolutely proves the point.

Life in the Balance offers a rare glimpse inside hospital wards where some of the most challenging medicine takes place, the most contentious medical decisions are made, and the most vulnerable patients’ lives are on the line. Here, perhaps more than anywhere, split-second decisions truly make the difference between life and death.

Dr Down, a consultant in critical care and anaesthesia at University College London Hospitals, shares the stories that have made up his career from life as a trainee with ‘an iota of respect’ on the wards, through his experiences as a consultant in intensive care and, ultimately, to a reckoning with mental health struggles as working and personal life became too much to handle. All life is no exaggeration.

Disease and disaster

and families in intensive care, and their relationships with the staff who hold their fragile lives in their hands.

On the pandemic, he says: ‘We saw such a lot [of death] in such a short space of time that it certainly affects people and particularly because it was a new disease. We were all running into this thing a little bit blind and there were other anxieties about our own health and about our own families. I think a lot of people are affected by the fact that they were looking after people without their families there, too, which is totally alien.’

‘We saw such a lot of death in such a short space of time... we were all running into this thing a little bit blind’

While there are stories that revolve around major national events the threads that make up the narratives in Life in the Balance remain steadfastly about the patients. Their characters, charms and worries are given every bit as much importance as their medical conditions. Equally important are Dr Down’s relationships with them, what he learns from each experience along the way, and also, sometimes, the questions about whether intensive care is actually the right course of action for them.

In the book Dr Down gives readers an often vivid and harrowing insight into the treatment and fallout around the Alexander Litvinenko case, the graphic and horrendous aftermath of the London bombings and the Hatfield rail crash, and the relentlessness of the COVID-19 pandemic for staff on the absolute front line. But he also tells the more every-day stories of patients

Speaking to The Doctor he says: ‘You see the best of people. And the thing that always strikes me is when I break bad news to a family and the reaction is so often extraordinary. Sometimes they say, “Oh god, this must be awful for you”. You see the best of humanity. But also, as I get older, I’m sort of aware how tough it is for patients being there. I’m constantly aware of that – that

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

the doctor | March 2023 19

balance between the burden of what they’re going through and the chance of benefit and what the benefit would be. Those are unanswerable questions…but that’s what takes up my headspace.’

Caring too much?

A theme running through the book, too, is the fascinating question of just how much doctors can afford to care.

Dr Down says: ‘I used to think that I would just want the best technical doctor – the one with the lowest complication rates or the surgeon with the best hands. Obviously, I do want that but more recently it’s really struck me how important it is to feel that someone cares. More and more I think the interactions are so important. When my mum was dying the staff were visibly upset and I loved that. I thought this is what matters to me. It’s a really difficult balance – and I don’t have the answer. I want people looking after me to care and to have emotions about it, but I don’t want their lives to be ruined. It’s tough.’

That phrase ‘all life is in ICU’ is as relevant to Dr Down as it is to his patients. This book is deeply personal – it is a rare and privileged insight into person and doctor. The beautiful and the mundane of personal, family life are juxtaposed with the immense challenges and rewards of working life.

Fragile and vulnerable

Before Life in the Balance went to press Jim Down stood before his intensive care colleagues at University College Hospital, London and read one of the most hard-hitting chapters of the book out loud.

Entitled ‘Crash’, it tells the story of a patient – Linda – who was incredibly unwell but whose condition had

stumped doctors, with test after test returning results which did not explain her worsening state. By the time Dr Down and colleagues had got to the bottom of her worsening ill health, Linda was unfit for surgery, and she died a few days later.

It was an episode that tipped Dr Down into a spiral of anxiety, negative and intrusive thoughts and a questioning of his own professional competence and confidence. He writes about this extensively and emotively. (See excerpt opposite)

‘I thought if I’m going to publish this, I’ve got to be able to read it to my colleagues. It was a daunting moment, but a few people came up after and said thank you.’

Dr Down is incredibly willing to discuss his own fragilities and fallibilities. In this book he dispels the mythical perception – a perception he had himself as a young doctor – of the God-like intensive care consultant. But perhaps what his stories do, more than anything, is offer lessons about how the NHS can be better amidst the enormous challenges of demographic change, enormous waiting lists and a workforce so beleaguered by the last decade.

The truth is that life is not just fragile for patients in hospitals but for doctors too. Dr Down’s experiences show the importance of support systems for when doctors need them most. Even more poignantly, perhaps, the final pages hint at the importance of compassionate leadership – of doctors like Dr Down feeling able to share their experiences and make those sorts of vulnerabilities normal and understandable for colleagues yet to experience their lowest moments.

Reflecting, he says: ‘I think it is the best shot we have got.

‘If we can create an atmosphere where people feel they can confess to feeling bad or feeling vulnerable then maybe we are really getting there.’

If this book is about anything – it is about compassion. What it means to be a compassionate doctor, but also what it means to be a compassionate friend and colleague. And in the NHS of 2023 staff need compassion as much as their patients do.

20 the doctor | March 2023

‘I want people looking after me to care but I don’t want their lives to be ruined’

GETTY

‘Create an atmosphere where people feel they can confess to feeling bad or feeling vulnerable’

‘If this book is about anything – it is about compassion’

‘When I’d expressed my condolences to Linda’s family I found myself loitering, looking for something more that I could do for them.

‘Anything to make it better, to make amends for what I’d failed to do three nights previously.

‘‘‘Thank you for trying,”’ they said. I went and reviewed a couple of other patients who might need to come to the ICU and then at 5 a.m. I went home. But I was not all right. I felt guilty, anxious and stupid. I was convinced that I was responsible for Linda’s death. I had the strong impression that one of the senior nurses thought I could have done better on the first night and, although I tried to persuade myself that it wouldn’t have changed the outcome, a part of me agreed with her.

‘Had I lost my clinical acumen? I’d certainly lost my confidence. Over the next few weeks, the events of that first night went round and round in my head. I tried to blame the Australian radiologists, but I had asked them to look for the

JUNIOR DOCTORS DESERVE BETTER

During an interview with The Doctor, Jim Down takes a moment to support junior doctor colleagues who, just days before the conversation, had voted overwhelmingly in favour of industrial action. ‘I think it’s very tough for them, if I’m honest,’ he says. ‘When I came out…30 years ago it was hard, some of the hours were ridiculous, but we didn’t leave medical school with £100,000 worth of debt, we were relatively better paid, and we had a kind of knowledge that it will be OK in the end. I think for junior doctors now it is very different.

‘I support them in taking action because I think we’ve got to look after them a bit better than we do now.’

wrong things.

‘Over and over again I kept asking myself why I didn’t think of Boerhaave. I pictured Linda with her sly smile, making pithy remarks the year before, and as I did so, the guilt and self-loathing welled up in me. I could think about nothing else. I couldn’t sleep, I didn’t know what to say to my children and I couldn’t see the point of anything. I couldn’t remember how to enjoy things. I didn’t think I deserved happiness. I kept imagining what her brother and son were doing now. How were they feeling? Were they coping?

When I went for a walk and saw people laughing and messing about, I felt angry. Why were they happy? Did they not know that she was dead?

‘My anxiety level rose and fell and rose again. For a while it would feel manageable, but then something would remind me of what had happened and it would start to build, a knot ratcheting tighter and tighter in my stomach.

‘I felt sick as intrusive negative thoughts bombarded my consciousness. I could explain to Tish what was happening quite rationally, but I couldn’t stop it.

‘The terrible thoughts just kept coming and, with them, panic. You are not good enough. You should have done better. You’ve been getting away with it for years. You need to work harder, or give up. It’s time to face it, you’re just not up to the job.’

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

the doctor | March 2023 21 MATTHEW

SAYWELL

In this extract from his book, Dr Down describes his profound anguish at the death of a patient

Your BMA

ARM discussions should be as representative as possible of the members we serve

One of the most important parts of my job as representative body chair is to organise, prepare for, and lead the BMA annual representative meeting.

It is the most significant policy-forming event of the calendar for our trade union and professional association and, each year, marks a huge opportunity for us to begin making a difference on the issues which affect our working lives and, ultimately, the care we can give to patients.

When I originally stood for election – for the deputy RB chair role – I was up against six more senior men. I was a woman, a junior doctor and from an ethnic minority. I was surprised I won, but a representative body of around 500 medical students and doctors from across the UK, from different specialties and healthcare settings, voted for me.

I wanted to make sure in the future people from minoritised backgrounds wouldn’t feel like their election was a shock – I wanted to use my voice, and my position, to ensure the BMA would become as diverse, accessible, inclusive, and representative as possible.

For far too long, too many organisations, particularly around medicine and healthcare, have been totally unrepresentative in our senior structures and we cannot do our best for a diverse workforce while this remains the case. There was a long way to go but we have made huge progress. We now have another junior doctor at the highest levels of leadership in the BMA – Emma Runswick, our deputy chair of council and junior doctor in psychiatry – and we have more women and more people from different ethnic minority backgrounds involved in leadership roles than ever before.

The truth is that there is always much more work to be done. I know, for example, that we don’t represent our black colleagues, our disabled colleagues, or our LGBTQ+ colleagues as well as we should; we are not representative for them. We must make routes into leadership roles in our organisation much more accessible.

At this year’s ARM I will take our work further. All chairs aim to balance the debate and hear from a varied group of voices to ensure accurate representation. But in the past, in order to do this, we have had to profile people who want to be speak on certain topics, based on their name.

I would have to assume gender, ethnicity, even

@drlatifapatel

disability to make sure we have a good diversity of speakers. But the truth is that I don’t know enough about the people I am seeing out in front of me at ARM – and it is entirely unacceptable to be profiling people based on how their voice sounds or how they look.

I need more information and more support to ensure that our discussions – discussions which form the policy our association will act on – are representative. At this year’s ARM I will champion positive action to achieve greater fairness, representation, and diversity. We will be seeking to collect equality and diversity data from participants at the ARM so when I am chairing the debate I can do so as effectively and as fairly as possible.

I want to, with confidence, balance the debate with a diversity of voices that is representative of our membership and demonstrate that, with effort, you can change representation. Again, for too long, we’ve had stages which are simply just not diverse – and this is to the detriment of us all. I know the difference this kind of work can make. I also chair your BMA equality, diversity, and inclusion advisory group and I am the chief officer equality lead. I also sit on the NHS equality and diversity council, the GMC BME forum and the GMC strategic EDI advisory forum, among others.

I’ve also joined the medical workforce race equality standard team. I regularly meet with other organisations to discuss and lobby on how we can better support our diverse membership and colleagues. This is important work – and I am absolutely committed to it. I have seen first-hand that diverse leaderships represent better.

Please get in touch if you think we are missing any avenues in our pursuit of the best possible representation for our members – and our profession – that we can achieve. If you think we can do anything more, you can contact me directly via Twitter or email me at rbchair@bma.org.uk

22 the doctor | March 2023

Dr Latifa Patel is chair of the BMA representative body

Through research, we will keep people connected to their families, their world and themselves for longer. And at Alzheimer’s Research UK, one in three of our research projects are made possible by generous supporters leaving gifts in their Wills.

Request your FREE Gifts in Wills guide today to find out how you can offer hope to future generations and end the heartbreak of dementia.

To request your guide, either:

• Scan the QR code with your smartphone camera

• Visit: alzres.uk/gifts-in-wills

• Email: giftsinwills@alzheimersresearchuk.org

• Call: 01223 896 606

More than 60% of BMA consultant members in England took part in our recent consultative ballot and a resounding 86% voted to take strike action to fix pay, fix pensions and fix the pay review process.

The Government now has until 3 April to make specific and substantial proposals. If they refuse, the UK consultants committee will seek to hold a statutory ballot for industrial action this spring.

bma.org.uk/consultantspayandpensions

3 APRIL

Editor: Neil Hallows (020) 7383 6321

Chief sub-editor: Chris Patterson

Senior staff writer: Peter Blackburn (020) 7874 7398

Staff writers: Tim Tonkin (020) 7383 6753 and Ben Ireland (020) 7383 6066

Scotland correspondent: Jennifer Trueland

Feature writer: Seren Boyd

Senior production editor: Lisa Bott-Hansson

Design: BMA creative services

Cover photograph: Andrew Baker

Read more from The Doctor online at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

the doctor The Doctor BMA House, Tavistock Square, London, WC1H 9JP. Tel: (020) 7387 4499 Email thedoctor@bma.org.uk Call a BMA adviser 0300 123 1233 @TheDrMagazine @theBMA The Doctor is published by the British Medical Association. The views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the BMA. It is available on subscription at £170 (UK) or £235 (non-UK) a year from the subscriptions department. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the editor. Printed by William Gibbons. A copy may be obtained from the publishers on written request. The Doctor is a supplement of The BMJ. Vol: 380 issue no: 8375 ISSN

2631-6412

Dementia is the UK’s leading cause of death. But with your support, research will find a cure.

ADVERTISEMENT

Our lightweight insulated panels make your conservatory: • Cooler in summer • Warmer in winter • Reduce bills • Quieter in bad weather To find out more about the benefits that the Green Space system can offer and see if your conservatory is suitable for any potential subsidies, contact us now. C O N S E R V A T O R Y R O O F S Enjoy your conser vator y all year round with insulated roof panels greenspaceconservatories.co.uk 0800 08 03 202 CALL FREE “It’s the best home improvement we have ever made. Our conservatory is now our diningroom in the garden.” Mike Millis, Middleton On Sea 10kHAPPY CLIENTS Terms and Conditions apply Green Space UK, Unit 8 BH24 1PD, Registered No 8542786, as shown on FCA authorisation, trading as Green Space UK, is a credit broker and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority Applies to orders of 8 panels or more. Valid until the end of April 23. Not to be used in conjunction with any other marketing offer 1 0 YRASREVINNARAEY REFFO 10 YEAR A N NIVERSARY O F F E R 01 RAEY A N YRASREVIN O F F E R DOC0323 £250 OFF quote ref