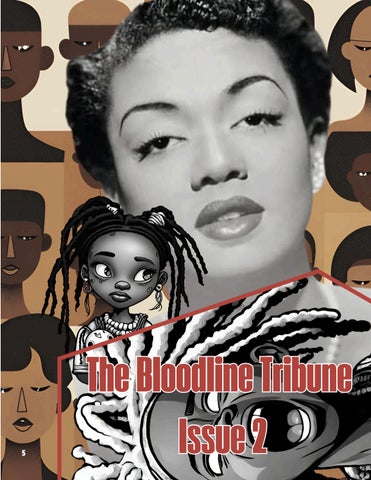

The Bloodline Tribune

Issue 2

BUDGET FRIENDLY MEALS FOR FULL FAMILIESMAKING SOMETHING OUT OF NOTHINGFRESH FOODS

Crystal Denise

COLORISM

Jay Rene

Yessica Jessica

BURNING HOUSE, MARTIN'S DREAM AND THE REALIZATION OF FALSE TRUTH Chuck King

FOOD TRAUMA

The Self Care Snob

Dominique Holiday Chuck King

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

It has been four months since the inaugural issue of the Bloodline Tribune took flight Our journey has been marked by consistent growth and positive experiences Readers from the Diaspora, including those in America, Canada, Belgium, Burkina Faso, Iraq, Russia, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, have engaged with our articles as we strive to deliver news information and resources to our community

We anticipate expanding our coverage across all topics, as everything connects to our people in some way It’s heartening to see reading becoming a trend once more Our goal is to make the Bloodline Tribune a topic of conversation at dinner tables, fostering family time and unity within all our networks

EDITOR

With each issue published in print or available for download, The Bloodline is dedicated to promoting Black Empowerment by honoring our rich diversity and common heritage By featuring stories of resilience, innovation and cultural pride the magazine serves as a guiding light of hope and inspiration for our collective aspirations Beyond just motivation, The Bloodline offers practical advice on leadership, entrepreneurship, education health and other essential topics that empower readers to take charge of their futures and more significantly, our shared future We prioritize building bridges, enhancing connections, and cultivating a more inclusive and united global community

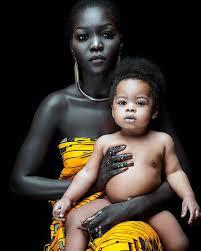

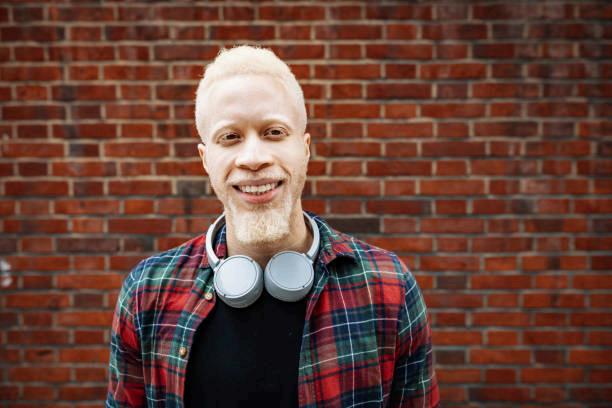

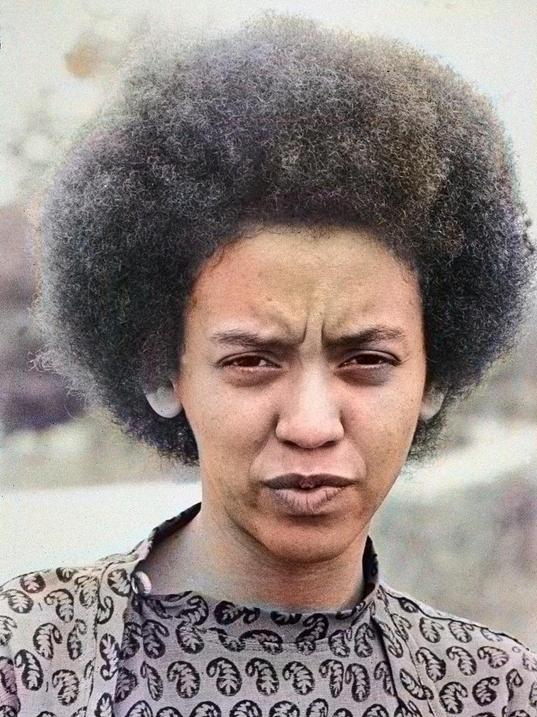

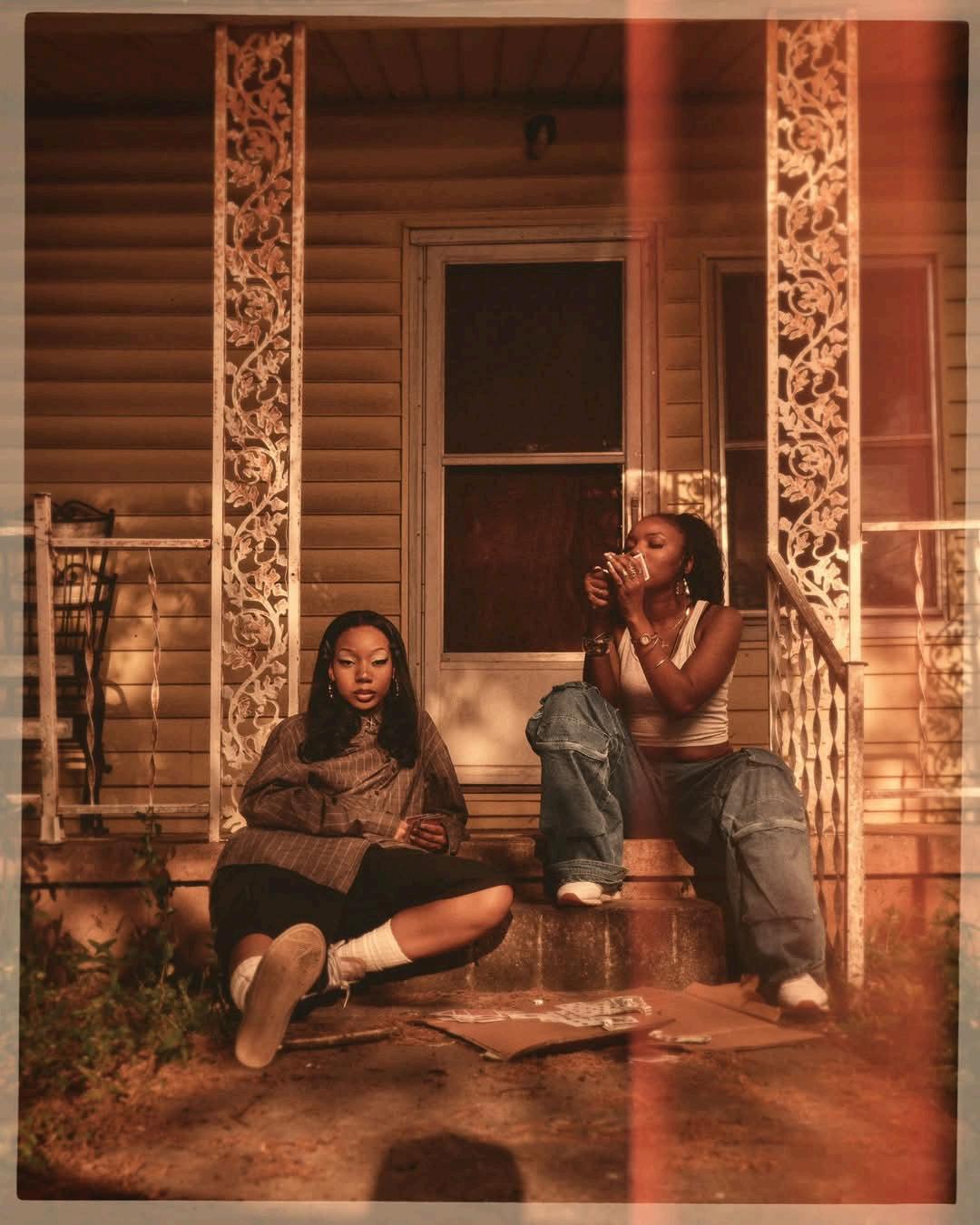

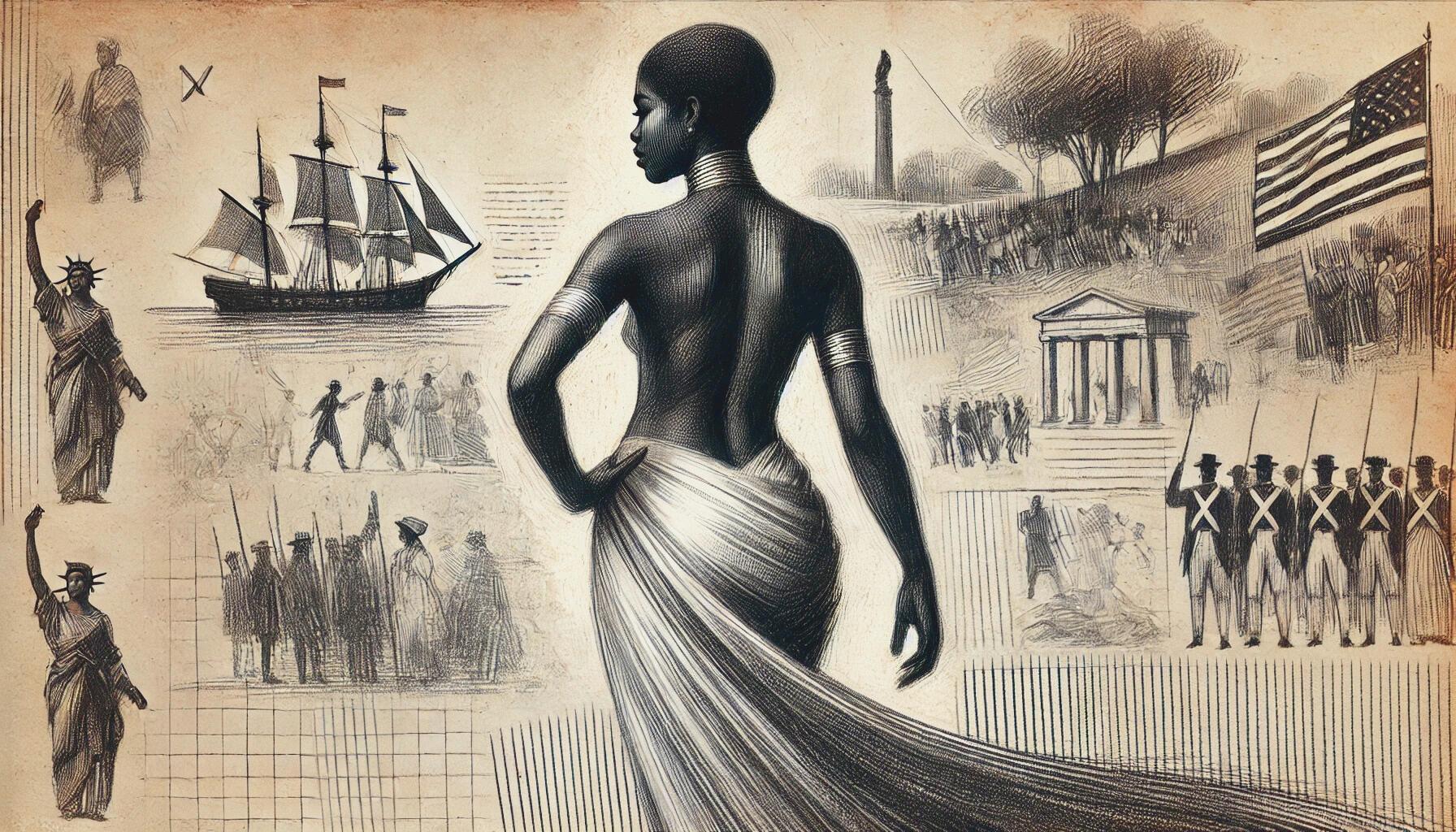

Colorism JAY RENE

Colorism is a topic that has been a part of the Black community’s conversations for years Sometimes out loud and other times, subconsciously At one point we didn’t know what it was just that it existed However, as time continued, we started to understand more what colorism was and it gave birth to a name Along with this, we have gotten to the point where we can identify it and most

of us try to find ways to combat it

Colorism is something that runs deep, unfortunately, and it’s going to take a lot of retraining to get us back on an accord of a universal Black pride of our beauty and differences

In this article I will be showing parts of my life that I feel are important to add

Regardless of our physical differences, we all encounter similar challenges throughout the diaspora, which is why collective unity is essential.

to this conversation because it gives perspective from an interesting place I will also be discussing where I believe colorism began, and I hope to not only start this conversation in hopes of creating other conversations that can tackle colorism but I hope to also be a part of the process of helping our people heal from the wound that colorism is

My initial belief is that colorism began during slavery Once I researched a bit on the subject, I found this quote “colorism in Africa as we know it today was not prevalent before colonization” (Google 2025) How people looked in Africa did tell what region they were from, but it was never looked at as related to race in any way When slaves first arrived, everyone was African It was pure blood, and there weren’t many differences besides maybe the tribes that they came from

5

However, when

the Caucasian savages also known as slave owners began to have their way with our women, it created a new type of people of mixed descent

From this crossing of the races, we begin to create all different shades of people At one time in history, they were classified by different names given to them by their savage slave owners The names include but are not limited to mulatto, (comes from the Spanish word "mulatto" which is related to the word "mule," signifying a hybrid offspring), quadroon" (onequarter African) "octoroon" (oneeighth African), and "mestizo" (often used in Latin America for mixed Indigenous and European ancestry) (Google, 2025)

The people of that time stop being Africans and were broken down into different subunits and each subunit came with his own benefits and disadvantages This was a spark of dissension that began to breathe and brew within the people at the time It created an atmosphere were these various levels were divided between who was better and who was considered the worst, and www.thebloodline743.com

unfortunately these beliefs were picked up by the slaves themselves Unity was one of the first things that they attacked because in our unity came strength

As years passed the color of one skin continued to matter to the masses outside of the slave community until it finally consumed them Willie Lynch, a known murderer, and savage began to structure how to capitalize on this division He concluded that using this division against our people was extremely beneficial Even Willie Lynch said that that division would be one that would play our community for years and years to come The bastard was right!

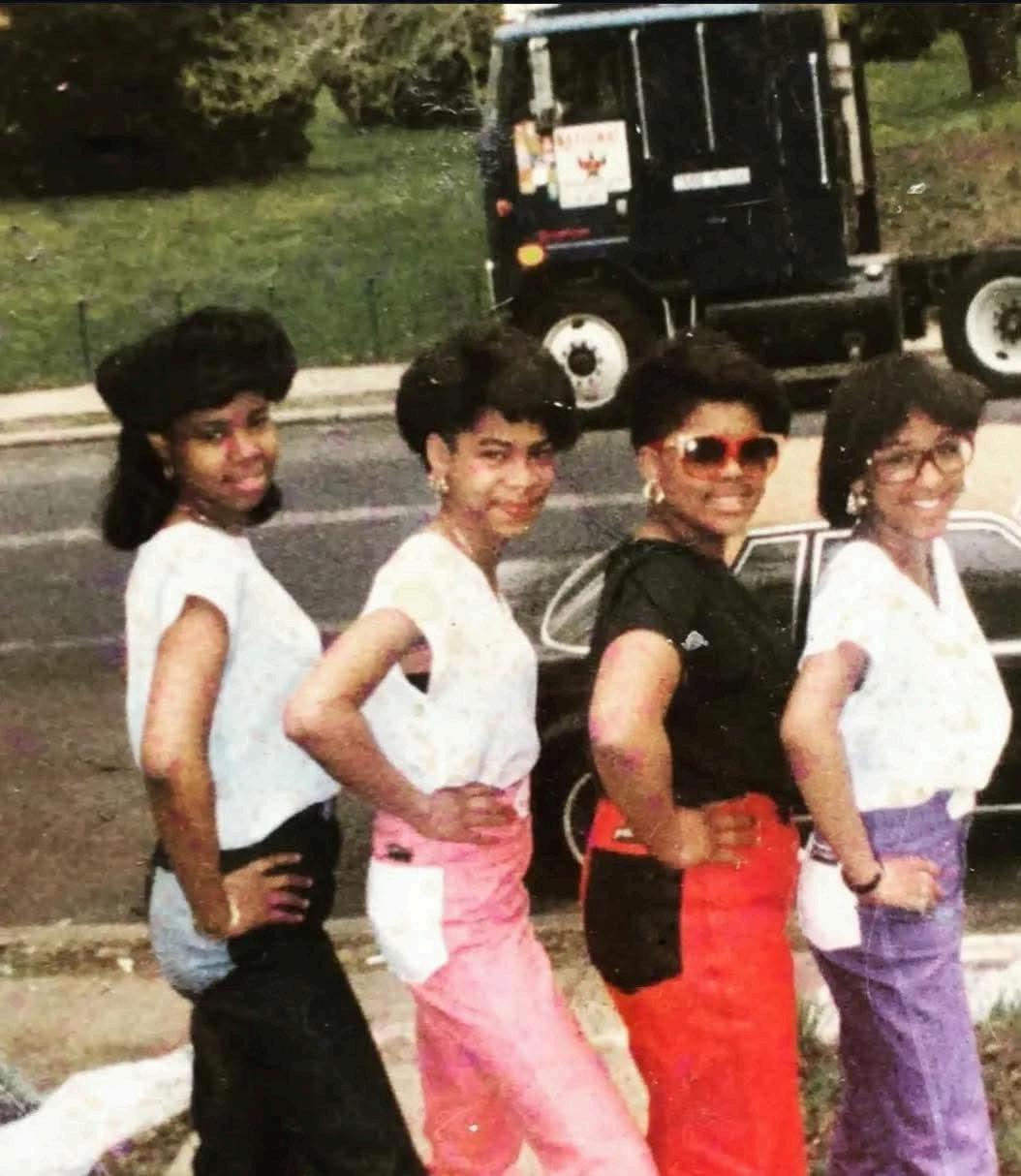

I I remember when I was coming up as a youngster with my own plight with colorism I was born in 81 and grew up during the 90s There was a clear distinction in difference of treatment between lighter Black children and my darker skin companions I was a brownskin girl In the wintertime I could get fairly light skinned, and, in the summer, I could definitely catch me a tan Being on neither side, let me see the advantages and disadvantages of both sides, so it gave me the ability to have a nonbiased opinion free of my own trauma

At one time I used to hide from the sun I asked myself in my wiser years (20s) “what sparked such a drastic reaction from a child and I’ve narrowed it down to two major reasons One reason was seeing how the darker skinned boys and girls were treated by others even adults They were often considered troublesome They were often marked and called names such as “African booty scratcher” “midnight” and even ugly There was no beauty to be seen in them just because of the color of their skin and as children, we pick up the habits and thoughts of our parents and those around us which brings me to the second part which is I was told by family members to not stay in the sun too much or I was going to get too Black

I didn’t really know what “too Black” meant, but I knew that it was a negative thing based on how they said it and based on the things that I saw happen to the fellow children that I knew

When it came to lighter skin friends and classmates, I did notice that they had advantages

They were often considered more “innocent” when disagreements happened in school between the children as they do, they were often put on a pedestal and at times were given favor when it came to being selected for leading roles, and things of that nature However the other thing that I saw was, they were often physically abused by students that were jealous of them. I have seen instances where girls with long hair or a soft curl pattern, would fall victim of someone cutting their hair, or someone would pour glue in it, or bullies would beat them up after school because they assumed that the lighter skin girl thought “she was all that” I will be honest I never wanted to be light skin but I did not want to be dark skin either I did not want to be abused as a light skin person and I did not want to be ostracized as a dark skin person so in the middle, I floated and watched my classmates and adults act a fool over color

I'm not sure how long my “hiding from the sun ” lasted, but I do remember when I began to learn

D L I N E

L O O D L I N E Set realistic goals

on I was 20 years old That is when I truly learned where I came from and the hardships of those in the past from books not furnished by my schools I also learned that by slave ship is not the only way the African people made it to what we now know as America and even Columbus made mention of Africans making it to the land before he ever seen it

I learned of people like Willie Lynch and the plan that he devised to separate our people To know the things that I saw as a child was partly, if not fully, a result of purposeful intent to destroy and divide my people, angered me and it made me stand up against carrying thosestereotypes around my community I decided that I would never help carry

the torch of such disruption between our people I stopped hiding from the sun, and I started to pour life into the younger children around me ensuring they knew that they were beautiful No matter the skin color They were beautiful and no matter how their hair curled or coiled that it too was a beautiful thing

Now, where is colorism in the year 2025? Well, it still exists however,

IM HAPPY TO REPORT THAT

there was more Black pride and Black love amongst our people Less and less people are chemically treating their hair, and they are embracing their natural coils, curls and kinks Darker skin is now currently seen as beautiful and we can see that in the many models and actors that we can view on our television and in magazine pages We also can see that our Black is beautiful from those that try to imitate us not only by cutting on themselves, but by staying in the sun for extended hours of time trying to achieve that beautiful me look that comes to us so easily

However, I must keep it real, colorism does still does exist It exists in homes across the country It exists in the workplace it exists the music industry, the movie industry, and all other things where the color of our skin

should not matter I have a friend who is a model and she has beautiful dark Ebony skin Not only is her skin beautiful but she too is also beautiful inside and out Just the other day I was speaking to her, and she was quite upset on how she went to an audition and out of all the women that was there, those in charge selected all lighter skin women

Though many of them, lacked the talent that they needed for the production that they were putting together. She immediately knew why and it was quite disheartening as I’m explaining to her to keep her head up and that it isn’t this way everywhere, however I couldn’t help but to feel anger that colorism still exists within our people So much so that some of us still refuse to see the beauty of ourselves if it’s not put in a package that the white man says is beautiful

So where do we go from here? Change Well, the answer is clear, but where do we start? Where we start in our own homes. How? We can fortify our children of being proud of themselves being proud of the way that God created them and being proud of what they see in the mirror, even though they may look different than their friends, even though they may look different than what someone tries to sell them as beautiful For us who call ourselves community leaders and community activists and advocates, we must create things that in still self-pride, love, and harmony with each other inside of our communities We also must take care of each other and pull each other up; meaning that if we see someone treating someone poorly because of the differences, we remind them that we ’ re all beautiful and remind them where that self hate developed from, in hopes that they too can be appalled enough to refuse to bow down to the standard that they tried to keep us in For those of us that are journalists we must create content very much like this that talks about these things

We also have a responsibility to make content to remind the general population that all Black is beautiful and the different shades that we come in are no better than the other, and that our unity overrides any of the plans they created against us Defeating colorism will take more than a day because it took more than a day to create the division that it has caused among our people for so many years But it starts with us one child at a time one mind changing at a time We must actively strive to retrain our minds

For example, when I was younger, I was told that I had “bad hair.” As you can imagine I didn’t, but before I knew better I used to tell my little sister that she had bad hair and that was farthest from the truth However, when you know better, you do better so when I knew better I made sure I doubled back to my sister to let her know that I was wrong that her hair is beautiful and why at one time I thought that she had bad hair To our youth, we must explain our mistakes I gave her the knowledge We can correct these roles that others put in our life, and we can correct the wrongs that we carry It starts with us Black love

THE AFTERMATH OF A SELF-DEFENSE ALTERCATION

Race and gender are both deeply intertwined elements of identity that shape how individuals are perceived particularly in the aftermath of a violent attack These factors not only influence how a person experiences the world but also play a significant role in how others perceive them In this article we’ll reference law enforcement media and the general public When an individual is involved in a critical self defense incident identity markers may influence fair treatment potentially leading to unfair biases and assumptions In many instances, those assessing the situation, like a jury, judge and prosecutor may not have the same understanding of one ’ s lived experiences

In particular for Black and Brown people, race can be a compounding factor that heightens the scrutiny and suspicion in any given situation In the context of a violent attack, black folks may be more likely to be seen as the aggressor even when they are the victim simply because of racial stereotypes that associate Blackness with danger or violence This bias,

www.thebloodline743.com

rooted in centuries of systemic racism can lead to disproportionate police responses, wrongful arrests, and harsher legal consequences. Candidly speaking, the stakes are higher for us, and that means preparation must be multifaceted: mentally, physically, emotionally, and legally Being ready to articulate your decision-making clearly and confidently is part of ensuring you don’t just survive the encounter but that you can also survive what comes next

We begin that preparation by understanding what happens during a defensive shooting Imagine how the body responds when startled, fatigued, or frightened If you ’ ve ever been in a car accident or a physical fight - you may have gotten a taste of your nervous system’s automated responses transitioning into ‘fight or flight’ mode

Humans are literally built for survival and when those instincts take over - they rely on bestknown movements, thoughts, and habits We can count on our bodies to do things like redirect energy towards vital muscles and organs. Our pain tolerance is heightened and our endurance is increased However this automatic reaction also means

www.thebloodline743.com

that our ability to process complex scenarios or evaluate long-term consequences may become compromised. That’s where preparation comes in Training isn't just about mastering techniques, but about teaching your body to respond correctly under stress It's about creating muscle memory for decision-making

In every instance that you are forced to present or pull your weaponbe the person to report it to the police A tragic example of how injustice and failing to report first can have dire consequences comes from the case of a political organizer from Michigan who was involved in a selfdefense shooting She was involved in an incident where she was harassed and threatened by a non-black person Fearing for her life she retrieved her unloaded legally owned firearm and presented it in hope of de-escalating the situation She ended the threat successfully and nonfatally but the true aggressor called the police first The Michigan woman was later arrested, charged, and convicted for the incident, despite her actions being a defensive response to an immediate threat Law enforcement and the prosecution’s case were framed around the attacker’s account of the story, which painted her as the aggressor

The absence of a self-reported defense narrative meant that the legal system did not properly take into account her side of the story one that would have likely justified her actions under self-defense laws

This case serves as a cautionary tale for anyone who might find themselves in a situation where selfdefense is necessary

It underscores the importance of being the one to report to the authorities, especially when you are the one forced to present a firearm When you wait for someone else to control the narrative, you give up the ability to set the stage for a favorable outcome

While preparing your mind and body to react in high-stress situations is crucial, equally important is knowing how to handle the aftermath Especially, when it comes to navigating the 911 call and interacting with law enforcement

This aspect is often misunderstood so let’s make it clear In the immediate aftermath of a defensive shooting, your main job is to position yourself as the defendant. You need to make the situation as easy to interpret as possible and avoid presenting as the aggressor The key here is clarity any ambiguity could be misinterpreted, and in a high-stakes situation those misinterpretations can have lasting consequences Be acutely aware that law enforcement will likely approach the scene with heightened caution, especially if there are multiple individuals involved or if the situation

escalated rapidly Their initial perception of the event may be shaped by their own biases preconceived notions, or the tense environment We must be mindful and vigilant in those moments as they can have a profound impact on how the investigation unfolds

When you dial 911, remember that your primary goal is to protect yourself Provide critical information, such as your location, that you are the victim of an attack and that you need immediate help Do not embellish the situation or offer unnecessary details To the best ability, keep your tone calm even though you may be in a heightened emotional state

Don’t be surprised that when law enforcement arrives, they may not immediately know who is the victim and who is the perpetrator This is why it’s essential to remain composed Keep your hands visible at all times Avoid sudden movements, as officers will be assessing potential threats Don’t make excuses or over-explain When asked what happened simply

state that you were attacked and acted in self-defense Avoid going into the specifics of the encounter The details of what transpired should be shared only once you have legal counsel Law enforcement may try to extract more information from you, but it’s important to stick to the basics When they ask questions remain respectful, but consider invoking your right to remain silent You can politely inform them that you will provide a statement only after consulting with a lawyer This is key anything you say at this stage could be used against you later, even if your intentions are innocent

Lastly, remember that posture is everything How you present yourself in these early moments can impact how law enforcement and even the public perceive your actions The goal isn’t just survival it’s ensuring that your rights are respected and that you ’ re not unfairly criminalized By handling the 911 call and your interaction with law enforcement strategically, you give yourself the best chance to navigate a situation that, though incredibly difficult doesn’t have to spiral into something more damaging Training, understanding your rights, and knowing how to respond when faced with life-threatening situations can help you not only survive the immediate danger but also navigate the legal matters that follow It is highly recommended to partner with a certified instructor retain firearms legal protection, and join a community of folks working towards similar goals

Protecting the black tradition of arms is truly an honor but it does require a heightened awareness and mindfulness

We fully understand the dynamics and potential ramifications of using deadly force The good, bad, and the uglyAs responsible gun owners- we consider the attack and the aftermath

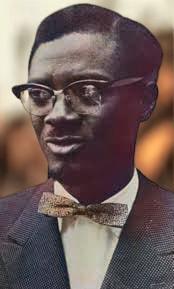

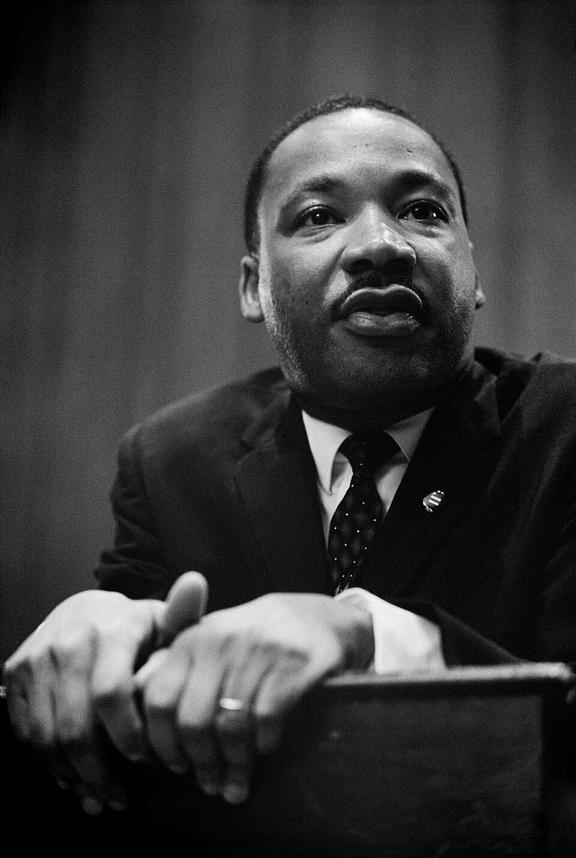

Burning House, Martin's Dream and the Realization of False Truth

Chuck King

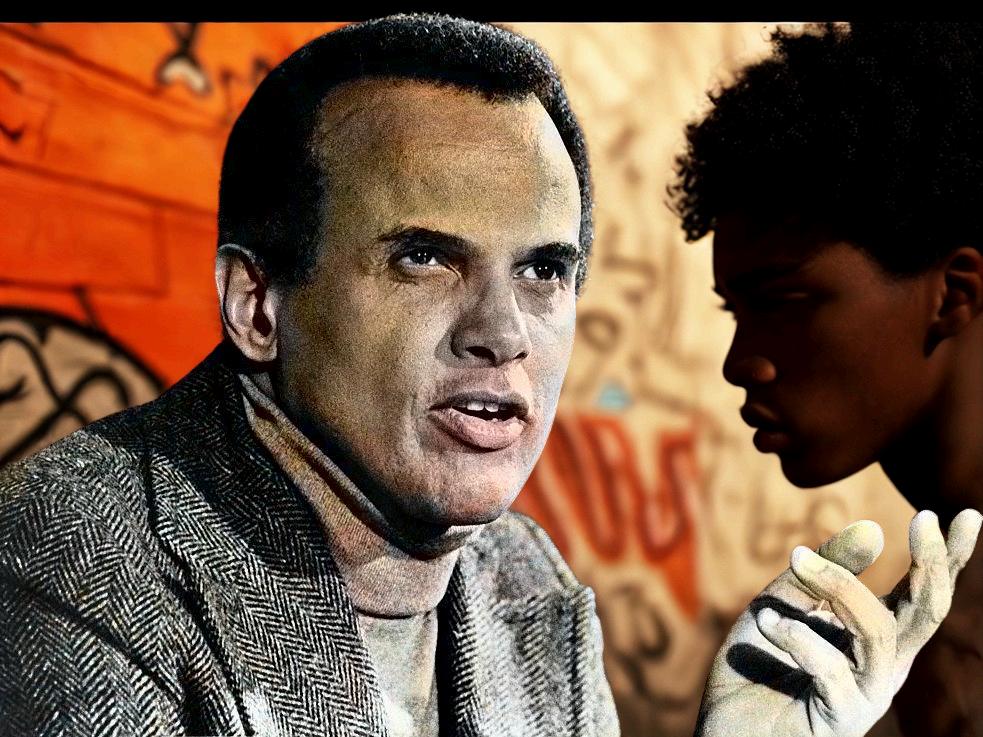

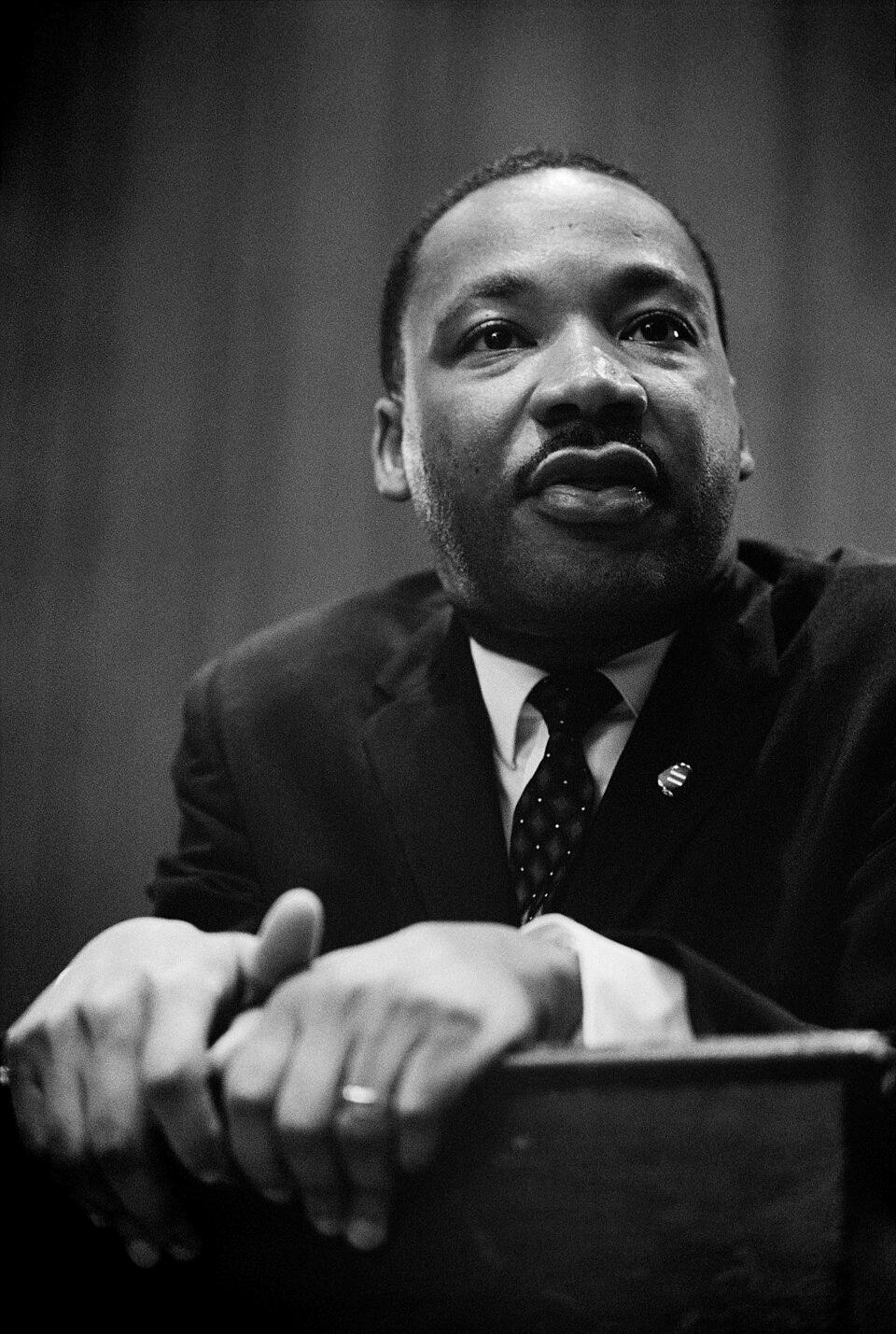

For many Black people today, Dr Martin Luther King Jr is often viewed as an idol. This piece is not intended to attack discredit or belittle him in any way Rather, it seeks to illuminate the truths he began to acknowledge while also offering hope for what lies ahead

Numerous factors played a role in the journey of Brother King While the criticism surrounding some of his beliefs was present his courage and passion for the people shone through clearly Martin seemed to genuinely believe that people's intentions could evolve, even in the face of openly abusive tactics that suggested otherwise The "violence" present in these nonviolent demonstrations remains deeply unsettling today Witnessing elderly grandmothers being struck by officers' nightsticks is

difficult to watch, read about, or experience firsthand I often wonder if he truly believed that this approach would bring about change or if he was simply working in hopes of a better outcome It’s evident that he was both adamant and determined. Rarely if ever is Brother King's militant side shared

Dr King was a Christian and a reverend, and much of his organizing efforts were rooted in the Black church an institution that has been in our culture for centuries However so, we still

must connect and validate the necessity of being militant In 2015 the Black church was targeted resulting in the tragic loss of nine beautiful souls While militant Christian groups are rare there were the Deacons of Defense, a group of armed Black men who collaborated with figures like Robert Williams Perhaps King's reluctance to adopt a militant approach mirrored the current portrayal of Black men who uphold the Second Amendment No matter the case and though our legal right any Black man or woman seen with a firearm is proposed as a "threat" We dont have the luxury to let our character speak for itself, atleast to those who dont look like us In contrast, others such as Malcolm X and Robert Williams took more aggressive stances while King although not militant himself, engaged with other Black men who were

It was evident that Dr King commanded the voice and respect of the people His commitment to nonviolence reflected the tactics of Gandhi While nonviolence should be a fundamental practice within the community the importance of self-defense cannot be overlooked Many people opposed the idea of permitting harm without consequences as a way to inspire change in response to the horrific actions of the oppressors

Many others seized this opportunity to promote their agendas under the influence of Dr King Efforts to censor other militant actions aimed at safeguarding the community or protecting individuals in that straightforward endeavor Kings wait on promised legislative changes "equal opportunities " and other propaganda may be considered similar to today's Dei agenda. And by the time he realized that these changes were never going to happen, he saw that the house itself was already burning down

He was connected to certain groups but often remained distant from many Black Nationalism organizations He advocated for integration and nonviolent civil disobedience as a means to achieve these goals Similarly, Black Nationalism also supports nonviolence while emphasizing Black selfsufficiency and the right to armed self-defense

Many believe if he would have tied himself to this side of the spectrum he would have lost support This may hold some truth for

individuals who don't resemble him; however, he would have garnered support for his contributions to figures like Garvey or Brother Malcolm X

THE BLOODLINE TRIBUNE

The ongoing drive to integrate into various sectors has overshadowed our enthusiasm for acquiring and empowering equity for our people

Reflecting on today, we observe that many individuals from different backgrounds reference Dr King in their own narratives However, we still find ourselves no where closer to the dream he envisioned which will remain just that a dream We will continue to endure the heat of burning houses until we take the initiatives to construct our own Struggling for inclusion in spaces where we are not welcomed has led our community to overlook the collective achievements we have made in this nation While we frequently celebrate those who were the first to reach certain milestones it is equally important to take pride in the numerous Black-owned businesses in our local communities These enterprises have honed their skills in various trades or crafts, allowing them to be competitive in the market and serve our community effectively The absence of celebration for them can be linked to their lack of presence and the reduced significance of prioritizing our spending within our own community It is crucial for us, as a community, to reaffirm our dedication to these fundamental financial principles

During the era of segregation many Blacks opened businesses as a response to

being refused service elsewhere This sparked the creation of small restaurants corner stores, repair shops, barbershops and more all aimed at making those who look like us feel comfortable and welcomed The drive to support their community outweighed the desire for acceptance despite the many sacrifices made by our people in this country. A notable example is Green Valley Pharmacy, which still operates today Founder Leonard "Doc" Muse shared a story from his youth when a neighbor sent him to the pharmacy to fill a prescription Upon arriving and taking a seat, he was informed that he could not sit there, so he chose to

wait on the sidewalk until his prescription was ready Muse later pursued a degree in pharmacy at Howard University and in 1952 established Green Valley Pharmacy in California His pharmacy served primarily Black customers and featured

a lunch counter, providing meals at a time when Black individuals were denied service at lunch counters providing meals at a time

when Black individuals were denied service at lunch counters elsewhere Nationalism fosters a focus on self-sufficiency rather than empty inclusiveness and misleading promises It encourages a respectful approach to support and invest in one another's efforts for a stronger collective future

If King had ever embraced a Nationalist mindset, the support he would have garnered would have exceeded his expectations His lofty aspirations and sacrifices are not forgotten even though the path to realizing his dream seems to be a dead end today The vision of our ancestors persists and each day brings us closer as we work together Influential figures like Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and other Nationalists recognized that the solutions to our collective challenges lie within the people

The urgency to address this matter is greater than ever, as we have strayed from our collective selfsufficiency. We tend to spend our money everywhere except with one another Even when faced with poor customer service, we often default to franchises and corporations as our primary sources for fulfilling our needs The schools, which our ancestors fought tirelessly to for us to integrate with continue to prioritize their own narratives while neglecting, if not outright ignoring, ours We alone bear the responsibility for our solutions. It is essential that we reduce our dependence on other nationalities and strive to foster more interactions among ourselves Let us commit to pushing, building, protecting, and supporting one another There’s no better time than now to begin implementing these practices

THE BLOODLINETribune

This should not be limited to holidays or as a reaction to injustices but embraced as a way of life With the freedoms available to us today, we have the opportunity to educate our youth whether within our homes or in community

spaces Engaging in selfless acts, such as pooling our resources to create businesses, cultivate food, and raise livestock, presents ideal courses of action We don’t need to merely dream about what we can achieve; we can start living it right now.

The legacy of Dr King is frequently overshadowed by misleading narratives and twisted perspectives on liberation Nevertheless as his descendants we can honor his contributions by promoting racial

collaboration in this new age Let's educate our youth and uplift our communities understanding that when we unite beyond our differences, we can genuinely create, or at least strive to create, everything we need and start addressing issues without resorting to oppression or pleading to the oppressors hands

The Negro will have to build his own industry, art, sciences, literature, and culture before the world will stop to consider him- Marcus Mosiah Garvey

Wishing you the best

Chuck King

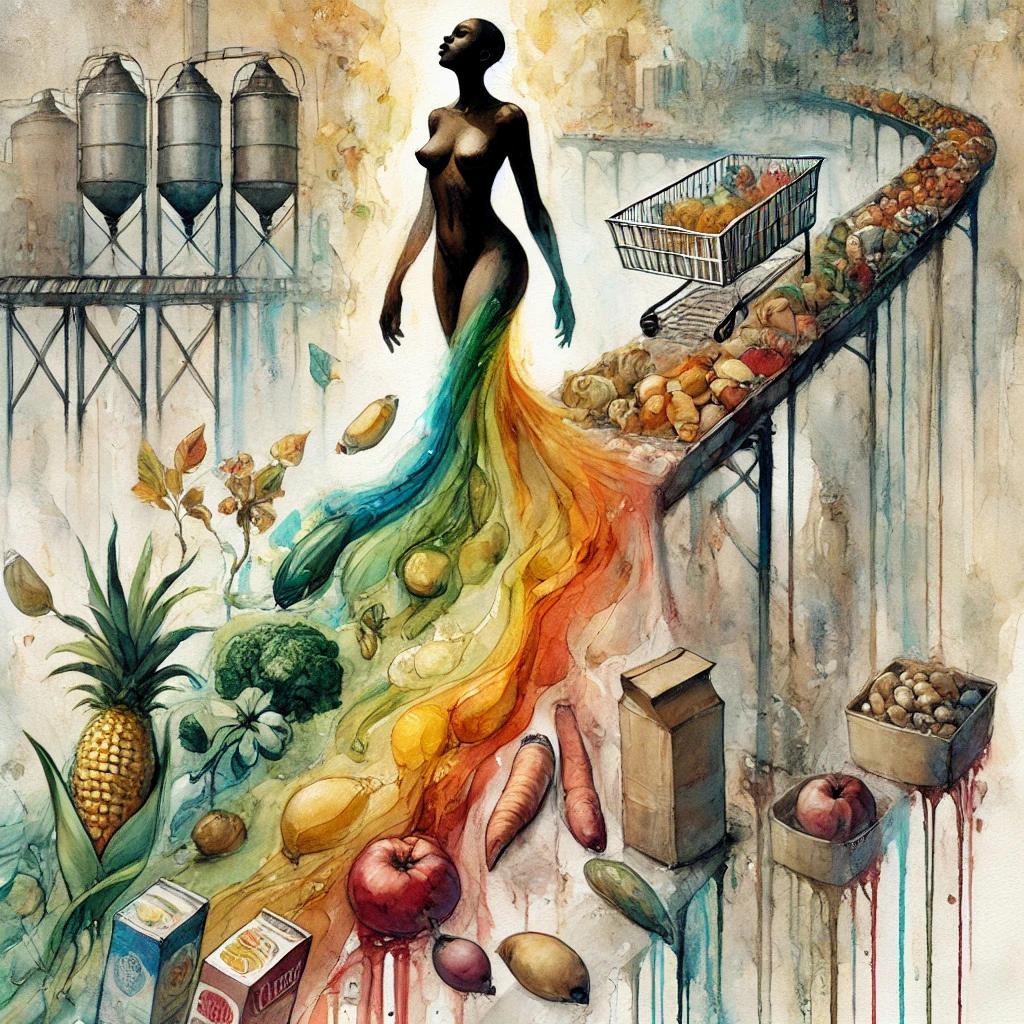

Budget Friendly Meals for Full FamiliesMaking Something

Out of Nothing- Fresh Foods

This current political climate has many of us paying more attention to how and where we spend our money At the top of the list is food one of the basic necessities of life Contrary to the popular belief, eating better does not have to break the budget Sankofa is the Twi word for “ go back and fetch it” which also translates to “it is not taboo to go back and fetch what you forgot" That being said let’s go learn from the past and create hearty, robust meals using in season produce as the base

Soups and stews are a great way to incorporate in seasonal produce They work well as a side but can also be a stand-alone meal Soups and stews are have been on the stove and tables of Africans and people of African descent for centuries A favorite of West Africans is Groundnut Stew or what many in the United States refer to as African Peanut Stew There are several variations of the stew depending on location The recipe we share below can be adapted to fit dietary needs

INGREDIENTS

1 Tbsp olive oil

4 cloves garlic

1 Tbsp grated fresh ginger

1 sweet potato (about 1 lb)

1 medium onion

1 tsp cumin

1/4 tsp crushed red pepper

1 6oz can tomato paste

1/2 cup natural style peanut butter

6 cups vegetable broth

1/2 bunch collard greens (4-6 cups chopped)

1 can of blackeye peas (optional)

Smoked paprika to taste (optional)

4 cups of cooked brown or wild rice

Instructions

1) Peel and grate and ginger and garlic using a small holed cheese grater Saute the onion, garlic and ginger in a large pot with the olive oil over a medium heat for 2-3 minutes, or until the onion becomes soft and translucent

2) While the onion ginger and garlic are sautéing peel and dice the sweet potato into 1/2-inch cubes Add the sweet potato cubes cumin and red pepper to the pot and continue to sauté for about 5 minutes

3) Add the tomato paste, peanut butter, and vegetable broth to the pot Stir until the peanut butter and tomato paste have mostly dissolved into the broth Place a lid on the pot and turn the heat up to high Allow the stew to come up to a boil Once it reaches a boil, turn the heat down to medium-low and allow it to simmer for 15-20 minutes, or until the sweet potatoes are very soft

4) Once the stew has simmered for 15-20 minutes and the sweet potatoes are very soft stir in the collard greens Let the stew simmer for about 5 minutes more, then begin to smash the sweet potatoes against the side of the pot to help thicken the stew Drain the peas and add, continue to simmer

5) Finally, taste the stew and add salt or red pepper, if desired Serve the stew with a scoop of cooked rice (about 3/4 cup), a few chopped peanuts, fresh cilantro, and a drizzle of sriracha, if desired

By: The Self

Salted Memories & Heavy Plates

A journey through the grief we swallowed and the recipes we almost forgot.

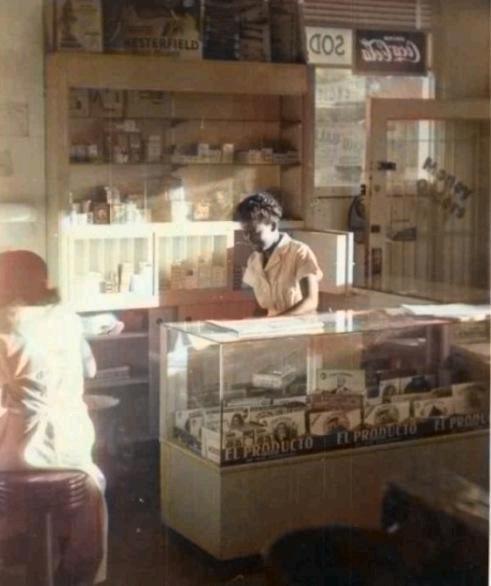

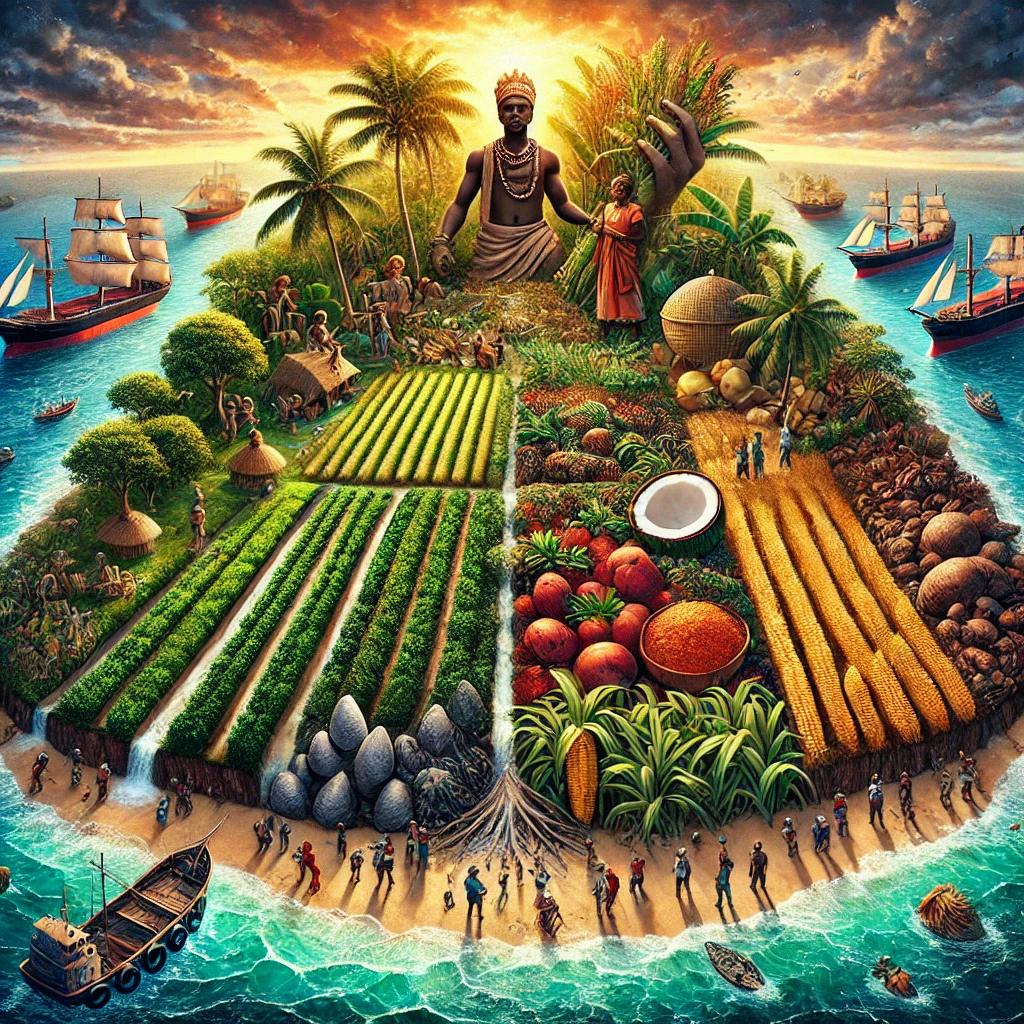

Colonialism and the Disruption of Food Sovereignty

Colonialism didn’t just take land it restructured the way people grew, accessed, and valued food. Across Africa, North America, and the Caribbean, colonial powers imposed agricultural systems that privileged export crops over community nourishment. Fertile land was seized to grow coffee, sugar, cotton, and cocoa for European markets, while Indigenous and African communities were forced to abandon their diverse, nutrient-rich local staples like millet, plantain, cassava, and wild greens.

Traditional practices such as communal farming, crop rotation, seed saving, and food-based spiritual rituals were either criminalized or dismissed as “primitive.” Colonial governments redefined agriculture to serve their empire(s), displacing generations of ecological knowledge in favor of monoculture and total market dependency.

In places like Jamaica, British rule converted smallholder farming communities into plantations, decimating local food autonomy. In Francophone West Africa, the French imposed quotas for export crops and punished those who resisted. Belgian rule in the Congo restricted traditional food growing and turned palm oil and rubber into for-profit, extractive industries.

The long-term effects are visible today: former colonies and historically Black farming communities alike rely heavily on imported, industrialized food. Many traditional grains, vegetables, and cooking methods have been replaced or stigmatized. What was once cultural and nutritional wisdom has become hard to access, underfunded, or altogether forgotten.

Colonization didn’t just steal land. In every region it touched, it severed people from the taste of home, and from the power of feeding themselves and their communities on their own terms.

Propaganda was part of this erasure. Colonial powers not only criminalized traditional growing practices they also framed local American, African and Indigenous diets as backward or inferior. In British-run Caribbean territories, posters and health campaigns encouraged “modern eating” that meant canned meats and white bread, discouraging cassava, collard greens, callaloo, or yam. The message was clear: colonial control didn’t stop at the borders; it entered kitchens, shaping taste and trust in one ’ s own food.

They took the land, and with it, the taste of home.

Slavery and the Invention of Survival Foods

The transatlantic slave trade uprooted people not only from their families and homelands, but from their food systems. Enslaved African descendants and those who were later taken there, possessed deep knowledge of cultivation, preservation, and cooking but they were denied access to the foods they once grew.

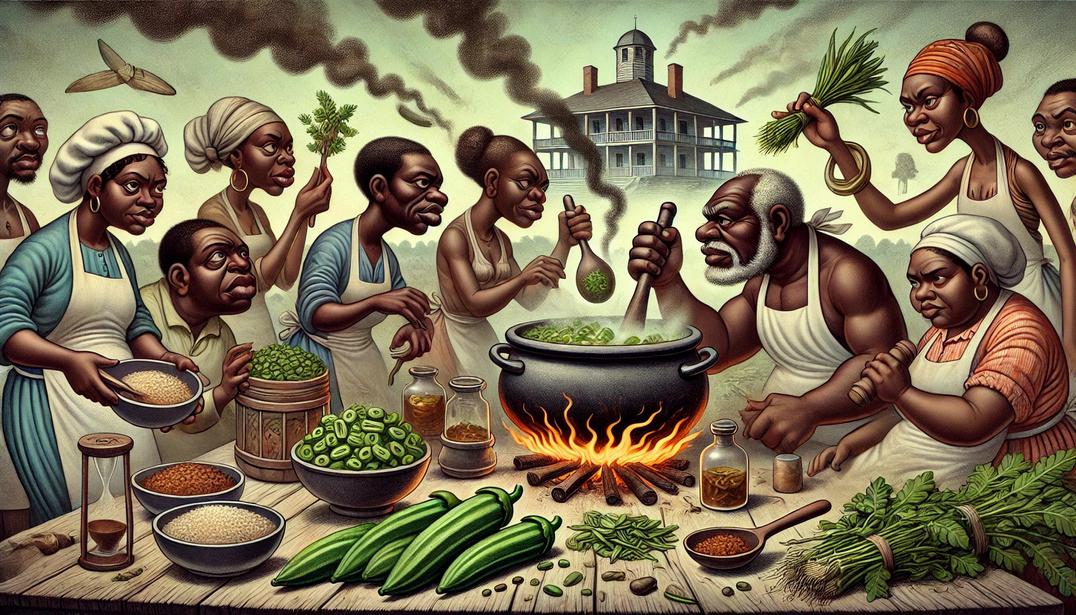

Instead, they were given rations designed to sustain labor, not health: cornmeal, pork fat, flour, and molasses. These ingredients were never meant to nourish they were meant to suppress hunger enough to continue exploitation. But within this cruelty, Black people created cuisine.

Using memory and skill, enslaved cooks transformed scraps into stews, made medicine from “weeds”, and infused flavor into what was meant to be flavorless. Okra, blackeyed peas, greens, rice these ingredients became anchors of continuity, even in a lands built to erase identity.

And yet, the very foods that kept people alive were later vilified. Soul food, born from resistance and creativity, became shorthand for disease and dysfunction in the mouths of public health officials who refused to understand its origins.

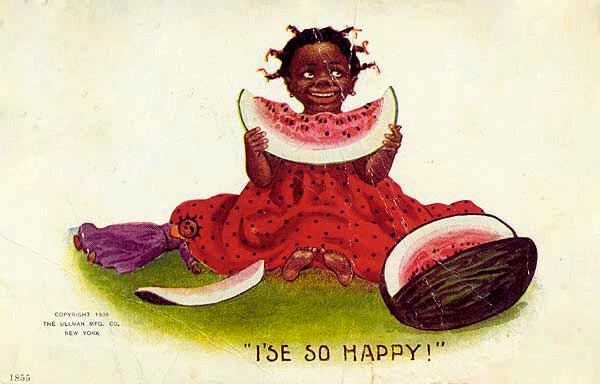

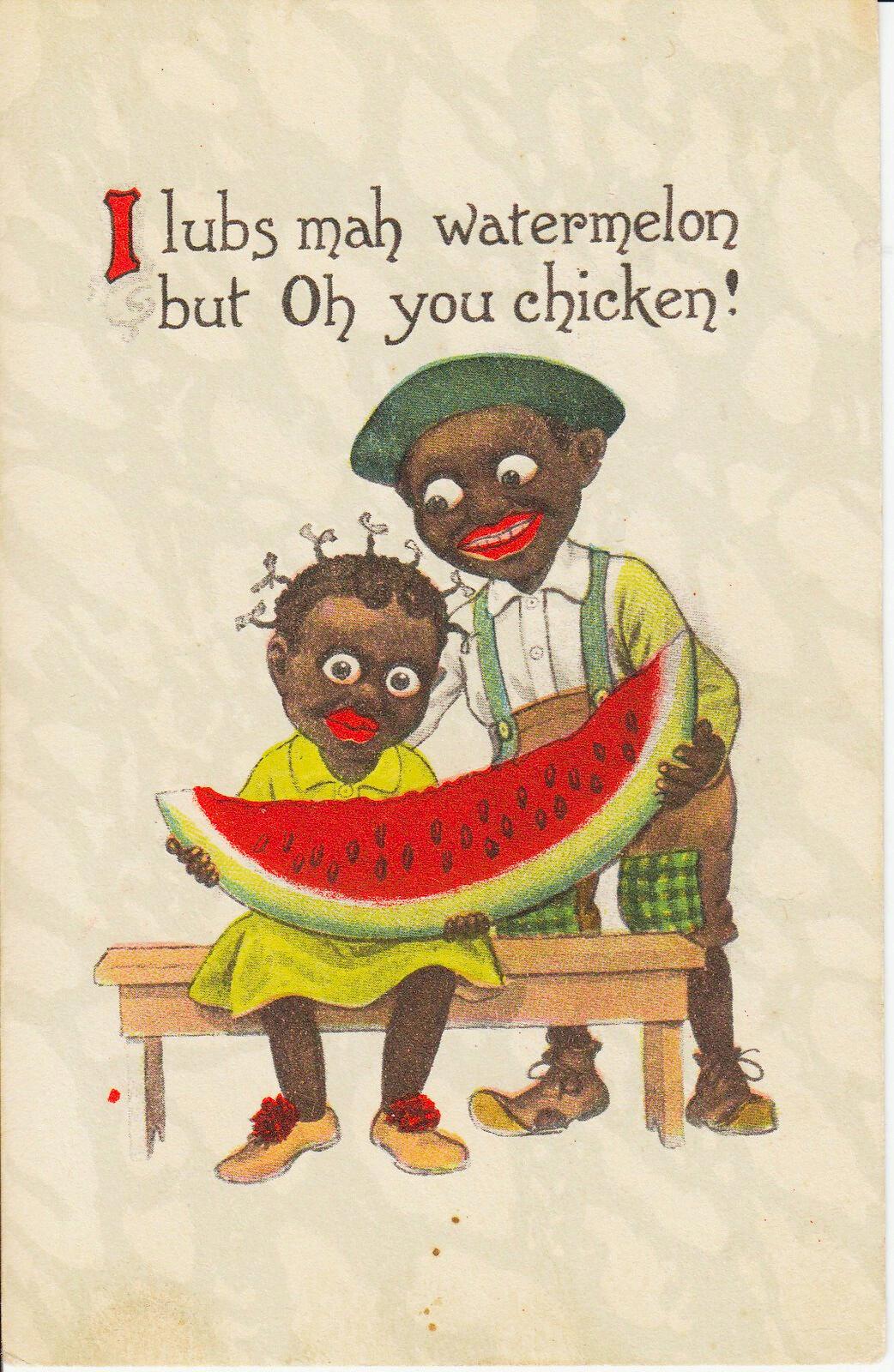

As Black Americans rose from slavery, the foods of survival became symbols of lack in the public eye. In minstrel shows, caricatures of Black people eating watermelon, chicken, or chitterlings turned nourishment into mockery. These images stuck over time.

In the 20th century, nutrition guidelines and school health campaigns targeted “Southern” or “ethnic” diets as risk factors for disease without context. Soul food became the scapegoat, rather than examining systemic food deprivation and ongoing racial stress that led to them becoming cultural norms and traditions.

We seasoned what was meant to starve us and they still blamed the seasoning

Capitalism and the Commodification of Nutrition

As plantation economies evolved into modern capitalism, food became another profit center. For Black communities, that meant increasing isolation from fresh, affordable food and growing dependence on highly processed, chemically preserved alternatives.

Grocery stores disappeared from inner-city neighborhoods while fast food chains rapidly multiplied. But this wasn’t random it was strategic. Economic divestment in Black areas meant fewer options and higher prices for healthier foods. Meanwhile, processed products, subsidized by agricultural policy, became ubiquitous.

Corporate messaging played a massive role in shaping those habits. From the 1970s onward, food companies targeted Black neighborhoods with high-sodium canned goods, sugary cereals, and fast food chains. These brands launched commercials during Black TV programming, plastered their ads on buses in Black cities, and used slogans like “I’m lovin’ it” to build loyalty through familiarity.

Black women in particular were targeted in political campaigns that framed poverty as moral failure. The “Welfare Queen” myth accused Black mothers of irresponsibility and indulgence, turning state-sponsored aid into a site of shame. Feeding your children with food stamps became a public spectacle, a performance under scrutiny.

The outcome? A generation of children raised on foods that were affordable but nutritionally empty. And when chronic disease followed, the blame landed not on policymakers, but on the mothers who were trying to feed their children with what was available; blamed for the calories, but no one asks about the absence of options.

Anti-Blackness in Health and Wellness Systems

Health care in the West has long positioned Black bodies as pathological too large, too loud, too resistant to discipline. Weight becomes

The Bloodline Tribune the explanation for everything, even when deeper issues are at play. Pain is ignored. Symptoms are downplayed. And food is reduced to numbers on a chart. Meanwhile, wellness marketing in the U.S. has defined “healthy” with visuals of thin, white, affluent bodies drinking smoothies and eating quinoa. Cultural foods flavored, fried, or made with care are either omitted or vilified.

Nutrition advice rarely considers culture. Instead, it imposes Eurocentric ideals of “clean” eating that leave little room for plantains, callaloo, or catfish. Wellness becomes an aesthetic: green juice, yoga, quinoa foods and practices that

come at the cost of erasing Black culinary identity.

The BMI, a tool created by a white European mathematician in the 1800s, remains the standard by which health is judged despite its complete disregard for ethnic, gendered, or body diversity. Our bodies are policed when we eat, and pathologized when we don’t.

Diasporic Distance and Cultural Food Shame

Across the diaspora, migration brought new possibilities and new pressures. In pursuit of safety or stability, Black families from all over the Americas, the Caribbean, and Africa found themselves in environments where their foods

www.thebloodline743.com

were not only unfamiliar but unwanted.

This shame wasn’t created in a vacuum it was fed by media, advertising, and institutional tone. Children’s cartoons often made fun of “weird food,” reinforcing the idea that white, processed lunches were the norm. School cafeterias rarely served diasporic dishes, and food pyramids rarely reflected the needs or tastes of non-European communities.

Children who brought jollof rice, roti, or collard greens to school were

laughed at. The smells, colors, and textures of cultural meals became markers of otherness rather than the norm they otherwise would have been. Parents, wanting to shield their children, began packing sandwiches and applesauce neutral foods that didn’t raise eyebrows.

This pressure to assimilate led many to leave tradition behind. Young people grew up without knowing how to make the dishes their grandparents once cooked. Cultural identity was folded away in favor of survival. The plate became a performance what we were allowed to enjoy had to be made palatable to someone else.

Gender, Care, and the Labor of Feeding

In many Black communities, women have carried the burden of nourishment. They wake early to prepare breakfast, plan dinner while working full-time jobs, and feed entire families while often neglecting their own needs.

Propaganda around gender and food has long painted Black women as either caregivers or abusers. The mammy archetype smiling, cooking, nurturing white families evolved into modern stereotypes of overfeeding, smothering “Big Mamas” blamed for health disparities in Black households. Media often reduced matriarchs to food pushers, framing their care as harmful, rather than naming the structural barriers they worked within.

Feeding others is one of the most sacred acts of care but it’s also unpaid labor, emotional labor, and generational labor. For many, food is love. But it’s also stress. It’s control. It’s expectation.

“She fed everyone else and forgot how to feed herself."

Mothers and grandmothers pass down recipes but also anxieties. They urge us to eat more, clean our plates, take another helping. Their intentions are to show us love and care, but the outcomes are complex. We inherit both the healing and the heaviness.

Counter-propaganda: Resistance, Reclamation, and Return

When a Black farmer revives okra seeds passed down for generations, they reclaim truth from a system built to erase it. When a Black chef centers Afrodiasporic cuisine in a fine dining space, they push against the lie that our food is

unrefined. When a mother serves stew instead of frozen pizza, not out of scarcity but out of pride, she is restoring what was distorted.

The future of Black food doesn’t lie in rejection or replication but in reconnection. To land. To legacy. To each other.

Despite everything displacement, trauma, policy, propaganda Black communities continue to reclaim their food systems. Across the diaspora, there is a return happening: to land, to seeds, to ceremony.

Black farmers are reviving ancestral growing methods. Healers are preserving spice blends and bone broths. Chefs are rewriting the narrative of what wellness looks like on our plates.

The most recent numbers from the USDA show more than 45,000 Black farmers working the soil again. That number is small compared to what we once held but it’s growing. Slowly, steadily, intentionally. And the movement is looking different now.

We’re seeing young folks, queer folks, women, urban growers, rural elders people who didn’t grow up on farms but still feel the pull. People who never stopped believing land could be a place of healing, not just labor.

11 Black Farmers And Black-Owned Farmlands To Inspire Your Green Thumb; Blavity, April 03, 2023.

THEBLOODLINE

Across the diaspora, we ’ re witnessing a return. To ancestral seeds. To soil that remembers our names. To food that doesn’t need permission to be powerful. And it's not just about farming. It’s about reclaiming what was interrupted and feeding our people with care, on our own terms.

We may never get back every acre, but we are reclaiming something just as deep: our right to nourish, to know, to stay rooted.

Because the land is calling us back.

Karee Upendo, Upendo Estate Farm

"Have Had Enough”: The Story of Charles Evans and Resistance in Norway, SC

Dominique Holiday

Chuck King

Throughout our history, moments when our people declared “enough is enough” are often overlooked and seldom shared The narratives and factual accounts of Black resistance rarely appear in textbooks; instead, they live on through oral traditions just as our ancestors intended These powerful testimonies inspire us to recognize the importance of unity and self-reliance within our community

This particular account centers on the small town of Norway SC a railroad community that was predominantly Black in the early 1900s. It emphasizes the spirit of resilience and the profound impact that collective resistance can have

The early 1900s were marked by deep-rooted oppression, many aspects of which still echo today Despite this our community stood firm determined to carve out its own path focusing on progress, dignity, and self-determination The Civil War had ended decades earlier, yet we were still seen as commodities The incident that follows began with bigoted sharecropping arrangements and attempts to force labor under unjust conditions

In protest, the people of Norway refused to work the fields or tend crops under such exploitation When siblings Addie and Judge Phillips members of a white family accused Lorenzo Williamson of “allegedly” cursing at them, they saw it fit to respond with violence Today we understand that respect is earned and reciprocal If Mr Williamson used strong language he had every right under the so-called freedom of speech And still, they thought it reasonable to whip him though they wouldn’t have whipped a dog

Their desire to control and punish Black bodies remained deeply rooted in the same ideology that fueled the bloodshed of the Civil War In their effort to subdue Lorenzo, they encountered Charles Evans and his brother, Jim Evans, who had followed him to the site in solidarity Despite this the Phillips siblings persisted with their abuse. That night, John T Phillips a Confederate veteran and father of the Phillips family was shot The community reacted with shock

Charles Evans was accused of the shooting, but one must wonder whether he received a fair trial if the jury even looked like him They called him “mulatto” because of his lighter skin I call him Black I call all of us Black And this, without question is Black history

They spent two days searching for the Evans brothers Charles Evans eventually surrendered to the mob that had organized to capture him When found, he was accompanied by Pink Harrell,

John Felder and Ulysses Johnson four Black men, all armed Outnumbered, they reluctantly laid down their weapons Evans’ comrades were beaten, and Evans himself was tragically lynched by the mob But resistance did not end with his death

In the days that followed 30 to 40 Black workers from the sawmill and planing mill went on strike, halting both operations Historical records show that nearly 200 armed Black individuals from across Orangeburg County assembled at Freedmen’s Hill just outside Norway Another 500 gathered nearby ready to defend their lives and dignity

Even white newspapers admitted how much local resentment had built toward the Evans family Charles and James Evans were children of Sarah Donaldson a formerly enslaved Black woman, and John Evans, a white man who claimed them publicly Their sister Lilian Williams, born in Norway in 1885, eventually fled the town for good after the lynching Norway for her became a place of mourning and defiance a symbol of how freedom had been denied in the very land where her family had once been enslaved As her daughter later put it, the Evanses were “voiced people” they didn’t let white folks run over them.

FROM THE EDITOR

Even in death, Charles Evans represented more than just tragedy he became a symbol of resistance His family was educated, bold, and

outspoken Their refusal to accept the everyday mistreatment of Black people challenged the racial order and for that white mobs saw them as a threat And yet when Charles was lynched, and his body riddled with bullets, his people did not run They gathered They prepared They stood firm in the face of oppression

And in that moment, Norway, SC became more than just a small town It became a battlefield for dignity a place where Black men and women declared their worth, their voice, and their right to live free

We cannot rely on schools to share these stories We must pass them down through family, dinner tables, front porches, and car rides wherever we gather Because this is not just history. It is a legacy of courage unity and self-respect

BLOODLINEMERCH

COMING SOON

FOLLOWUS

@THEBLOODLINETRIBUNE

@THEBLOODLINETRIBUNE

@THEBLOODLINETRIBUNE

@THEBLOODLINETRIBUNE

TELL OUR OWN STORIES

Black Empowerment Magazine Promoting Unity Across the Diaspora