This catalogue presents student projects from the 7th May Expo, exploring themes of community empowerment, collaborative urban strategies, and building more inclusive, connected neighbourhoods.

Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

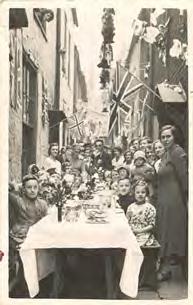

The Bartlett School of Planning (BSP) continues to celebrate student-led inquiry and collaboration through its annual Expo, which took place on the 7th of May, 2025 in the Student Centre. This year’s theme -- Co-creation of the Built Environment -- responds to the growing need for interdisciplinary collaboration and inclusive, community-driven planning. Rooted in the belief that planning must reflect the voices of those it serves, this exhibition showcases how co-creation can shape better, more connected urban futures.

The 2025 BSP Expo brought together students, staff, and alumni to explore the many dimensions of co-creation in planning. Hosted in UCL’s Student Centre, this year’s event was shaped by students who saw an opportunity to spark deeper conversations on collaboration, participation, and shared authorship in the built environment.

The atmosphere on the day was electric. Crowds gathered to support their peers, and the space buzzed with dialogue about the work on display and the broader responsibilities planners hold in shaping inclusive places.

Key highlight included the presentation of the Just Space Manifesto, results from the 2024 UCL/Just Space Knowledge Exchange, and the showcase of the works from the 2025 Building Bloomsbury Hackathon in collaboration with the UCL Vision and Strategy team, further cementing the Expo as a platform for real-world, co-productive planning conversations. While the day itself was bustling and at times even a bit hectic, the energy and turnout were a testament to the strength of our planning community.

To round off the day, we also held an end-of-year celebration, a chance to relax, connect, and properly honour everyone’s achievements over the past academic year.

This catalogue serves as a lasting record of the projects, ideas, and critical reflections that made this year’s Expo so special. Whether you joined us on the day or are encountering these works for the first time, we hope you find them as inspiring and thought-provoking as we did.

The BSP Expo Organising Team, Bartlett Urban Planning Society and Lucy Natarajan

Exploring how participatory planning empowers communities to shape their own environments.

Alicia Tsang, Roba Abdelhak, Yiheng Ye, Yuen Shing, Cheung Chester, Dyah Puspagarini, Jenna Chien, Khansa

Anastya, Muhammad Hero Umar Renaldi

Building Bloomsbury Masterplanning Hackathon Winners

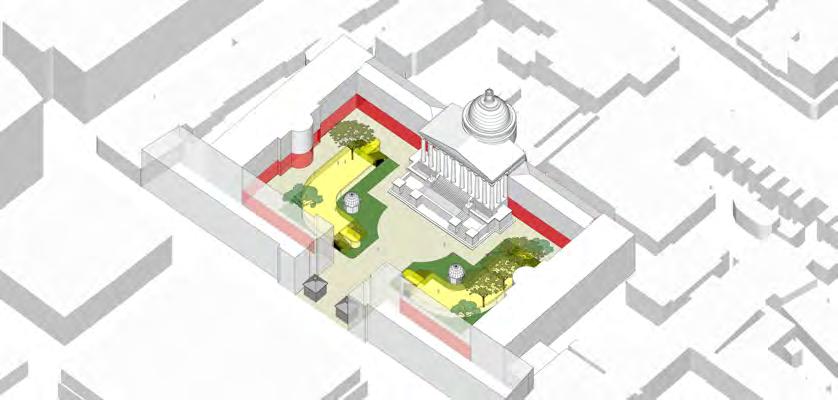

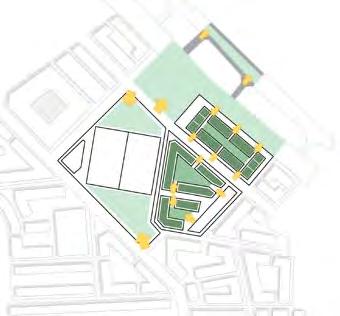

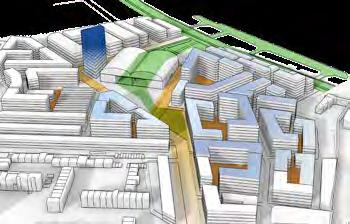

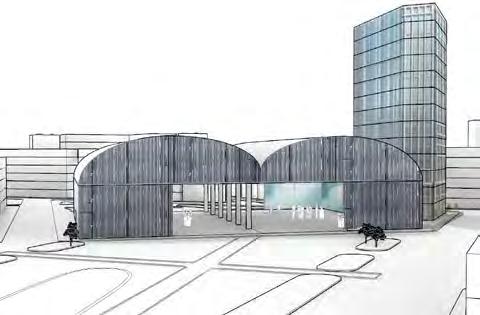

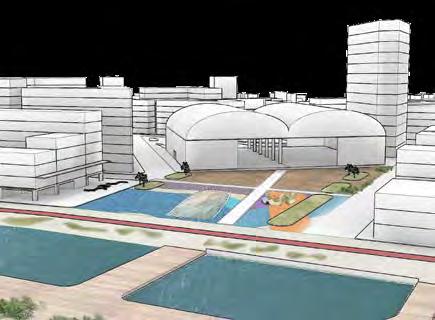

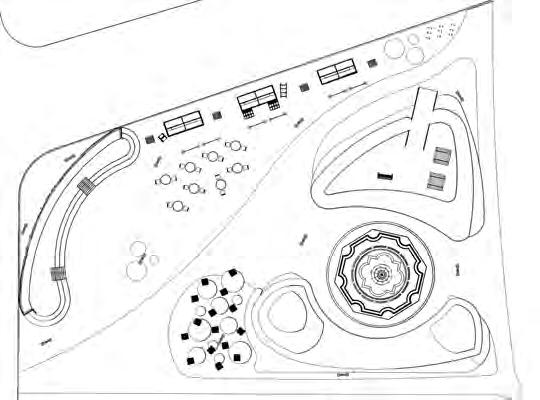

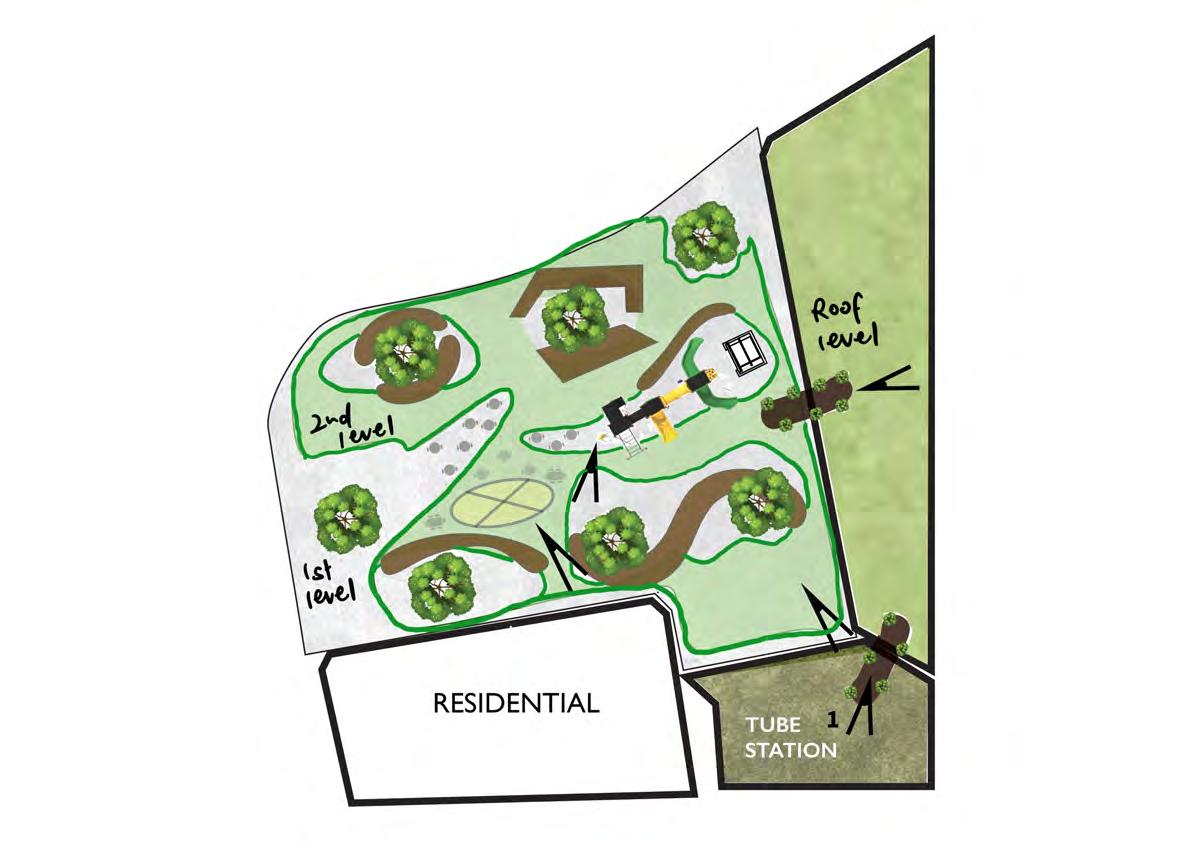

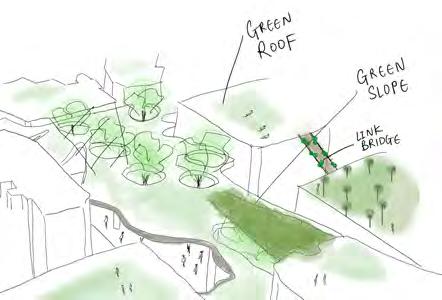

Over four days, UCL students from across disciplines and departments came together to reimagine the future of UCL's Bloomsbury campus. Delivered through a UCL ChangeMakers project with support from our BSP Staff

Partner Valentina Giordano and KPF Architects, the Building Bloomsbury Hackathon was driven by a shared ambition to contribute to UCL Vision 2050.

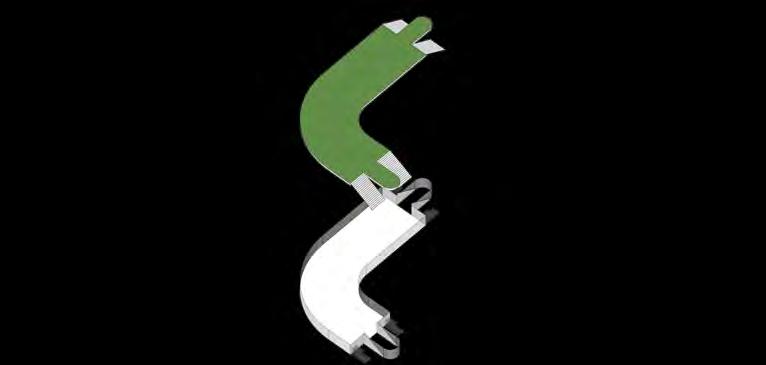

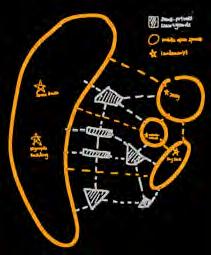

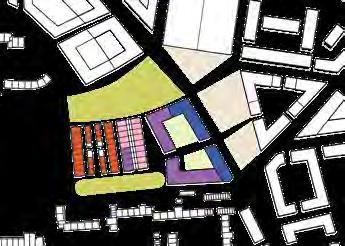

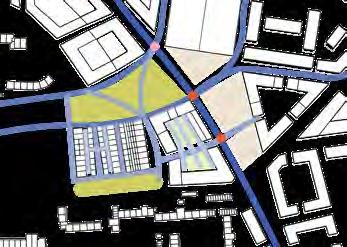

The proposed development plan from team 3 emerges from an extensive design process initiated at the Building Bloomsbury Design Hackathon. The project presents a cohesive, overarching vision aimed at enhancing user experience across the UCL campus while addressing existing spatial and social challenges. Its design and policy proposals align with UCL Estates initiatives and the London Plan’s strategic objectives reimagining campus through community collaboration. At its core, the proposal emphasizes Co-Creation and Co-Design reinforcing the university’s integration into the city’s fabric and strengthening connections between the academic community and the broader public. This integrative approach promotes community engagement, prioritizes social equity and embeds sustainability as core design anchors that redirect the implementation of design solutions, setting a precedent for inclusive and resilient urban transformation.

Tsang, Roba Abdelhak, Yiheng Ye, Yuen Shing Cheung Chester, Dyah Puspagarini, Jenna Chien, Khansa Anastya, Muhammad Hero Umar Renaldi

Central Location – The campus is situated in a prime area of London, near Euston and Euston Square stations, providing excellent transport links.

Access to Resources and Infrastructure –leverage the rich cultural offering of the cities, proximity to museums, libraries, theatre.

Access to transport – As a city university, transport is very accessible to all students and visitors

An academic network deeply roted in the cityscape, leveraging the universal and diversity that enriches the university model.

Integrating the ubiversity within the urban fabric of the city.

UCL envisions a seamlessly integrated open urban campus that strengthens its identity as a city university while aligning with London Local Plan. By embracing permeability, sustainability, and innovation, the campus will function as a dynamic, inclusive public realm, blurring the boundaries between academia and city life.

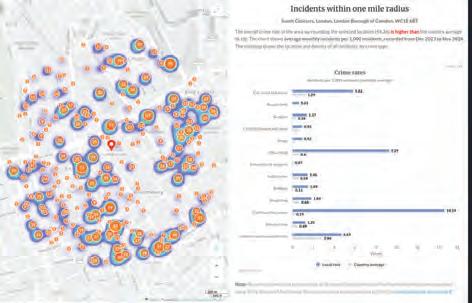

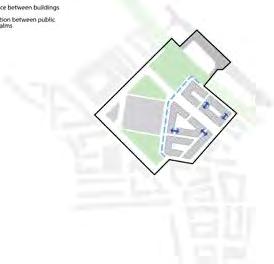

UCL’s campus sits within a high-density urban area, experiencing high crime rates and congested pedestrian routes. The blending of public and private spaces creates unclear boundaries, leading to wayfnding diffculties and safety concerns.

Green Spaces – Close to Gordon Square, Woburn Square, Tavistock Square, offering relaxation and outdoor study areas.

Strong Academic and Reseach Environment Diverse Campus Facilities

Compact and Crowded – The layout is dense, with many key buildings concentrated in a small space, leading to congestion and navigation challenges.

Limited Facilities Under provision of study spaces, sport facilities, other student union activities, and a diffculty in creating new developments on campus.

Accessibility Issues – Some older buildings might have limited accessibility, despite designated accessible routes. Access from West to East Underutilization of spaces overlooked despite their potential for student faculty.

Safety High crime rates around the area, under-lit areas

Expansion & Modernization – Potential improvements in accessibility and building renovations to modernize the campus.

Green Spaces Potential spaces for urban green pockets between the buildings, more greenery by pedestrianising Gordon Street

Urban Integration - transform unused spaces into multi-functional public areas to be used by the local community

Digital Initiatives & Smart Campus Technology

Retroftting retroftting existing buildings to improve environmental performance

High Cost of Urban Expansion – Building and land costs around the area makes urban expansion off campus nearby extremely costly and diffcult to justify. Climate change – Diffcult to foresee whether retroftted thermal performance solutions will be too warm for the future. Regulatory Constraints – Many UCL

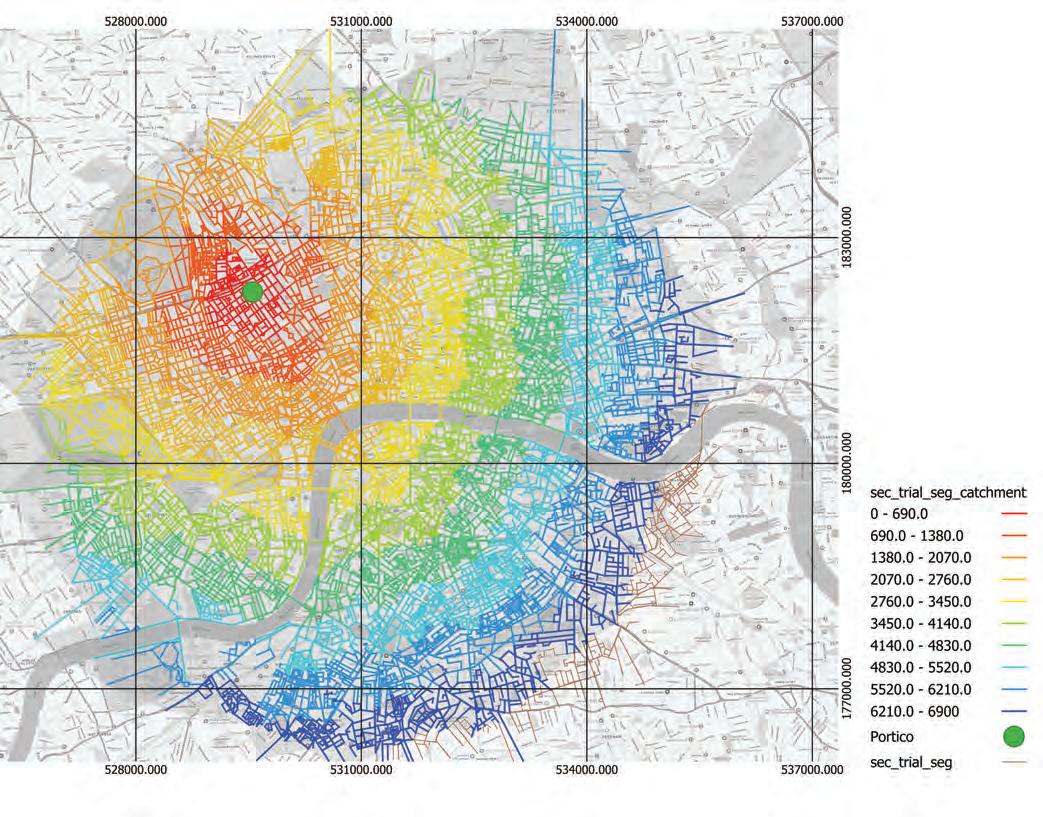

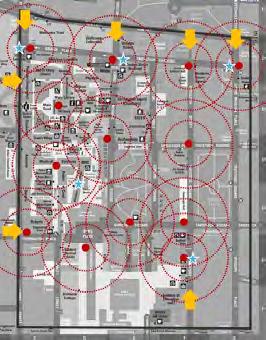

Segments with high integration at local radii are likely natural attractors for foot traffc, commercial activity, and public transport. These places are identifes and used to place active frontages, markets, mobility hubs, or public plazas. Integreation analysis also informs the regentrifcation of underperforming spaces, neglected networks with lower integration are programmed to improve permeability and liveliness. Integration analysis is also used to compare design before and after design interventions to testify effciency and improvement of urban movement. This is demonstrated in pedestranizing streets around campus to enhance walkability and embed an

fceine t movement network.

Google Maps reviews of the Petrie Museum reveal recurring issues with fragmented wayfnding on UCL’s Bloomsbury campus. Visitors describe the entrance as ‘awkward to fnd,’ noting that it is set back within university grounds without clear public markers. The journey requires navigating stairs, with limited alternative accessibility information. These insights confrm the lack of visible wayfnding strategies and confrming the blurred boundary between UCL’s lic and private zones, directly impacting visitor experience and campus identity.

Photos of UCL

Jacobs’ principle of natural surveillance emphasizes that well-designed public spaces encourage activity, deterring crime and enhancing safety.

A well-integrated campus should offer a gradient of privacy, balancing open public engagement with areas for focused academic activity.Clearly marked transitions between public and academic areas using landscape, architecture, and digital tools to guide users intuitively.

Connectivity ensures that UCL is woven into the city’s mobility and transport framework, promoting accessibility while reducing barriers

Provide easier routes while serving as branding tool for UCL students and local residents. It integrates event information, linked with QR codes for quick access to real-time updates and navigation, and emergency lights. Strengths:

• Provides alternative routes including fastest route, air pollution levels, green-belt infrastructure, street lighting availability

• Integrated with a mobile app Strategically placed in high-trafc student areas

• Direct integration with campus security for immediate response Weaknesses:

• High maintenance cost

• Overlap routes, causing pedestrian congestion

• Requires physical space from pedestrian walkways Opportunities:

• As an icon and branding tool for UCL, reinforcing its identity as a city university

• Potential collaborations for advertising services

• Solar panel as energy source Threat:

• Vandalism, may lead to damage and higher maintenance costs Weather and climate change

• Storing or tracking movement data could raise GDPR cause user privacy concerns

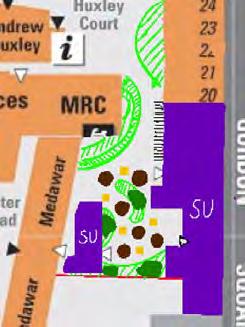

Converting the Medawar garden into a new student social hub, cleaning up the area, and utilizing Dr William’s Library, the townhouses, and the Henry Morley Building around the garden as new student union buildings.

Strength

• Provides spaces for individual and collaborative study, leisure and social activity, and society events.

Weakness

• Requires movement of department ofces and lecture building, considerations for building-specifc facilities

• Embodied carbon cost from extensive removal of preexisting structures. Opportunities

• Large, extremely underutilized space. Consistently referred to as “hidden gem of south quad”

• Reduces foot trafc and congestion at both Student Center entrances.

• Street level access can be regulated by ID. Only other access point tucked away in the south quad, ensuring privacy.

• Remodelling could address accessibility issues for movement impaired students and faculty. Threat

• Construction work might affect access to the building servicing for Medawar. Care needs to be taken to work around the listed status of

Strength

• Icon of UCL

• One of the main entrances to the campus area Closest to primary road (Euston Road)

Weakness

• Under-lit and barren at night

• Lack of student activities

• Lack of seating No tactile tiles for people with vision impairment, signages with brailles Opportunity

• Enhancing main quad as the entrance of a university, full of student activities

• Main information centre for current, potential students, alumnis and staff Gently push the public away, ensuring safety and privacy.

• Adding more lighting, increasing perceived safety at night

• Provide study and leisure spaces for students and public Threats

• Rigorous and long process of planning is required to preserve Grade I listed heritage building

Localised City: La Sagrera

Cheryl Ip, James Critchley, Sheshaagilandam Vallinayagam, Taylor Grafstrom, King Hin Wong

Yongxiang Liu

MSc International City Planning

Development of La Sagrera in Barcelona was based on a vision that manifests by the year 2050. The vision is to develop a localised economy, which could be achieved by increasing the value of the domestic economy. The role of Public Common Partnership (PCP) and governance model plays a crucial role in setting up a working model that fosters Co – creation, by involving local communities to partner with expert group and local authority to perform decision making for the future of La Sagrera that has consequences on Barcelona and whole of Spain in the next 25 years.

Development of La Sagrera in Barcelona was based of a vision that manifests by the year 2050. The vision is to develop a localised economy, which could be achieved by increasing value of domestic economy. The role of Public Common Partnership (PCP) and governance model plays a crucial role in setting up a working model that fosters Co – creation, by involving local communities to partner with expert group and local authority to perform decision making for the future of La Sagrera that has consequences on Barcelona and whole of Spain in the next 25 years.

“To create an integrated and advancing economy within La Sagrera that allows for growth of Barcelona’s R&D division through Public Common Partnerships with large businesses that will deliver the means for achieving these goals. The area will use the investment to upskill in areas of education, both in 1revitalization, serving as an example of advancement for the rest of the city.”

Building Place through Trust and Participation

Xeniya Stepanova, Ayan Gasimova, Evey Grika, Rei Lindemann, Aishwarya Pillai, Natacha Soto

MSc Urban Design and City Planning

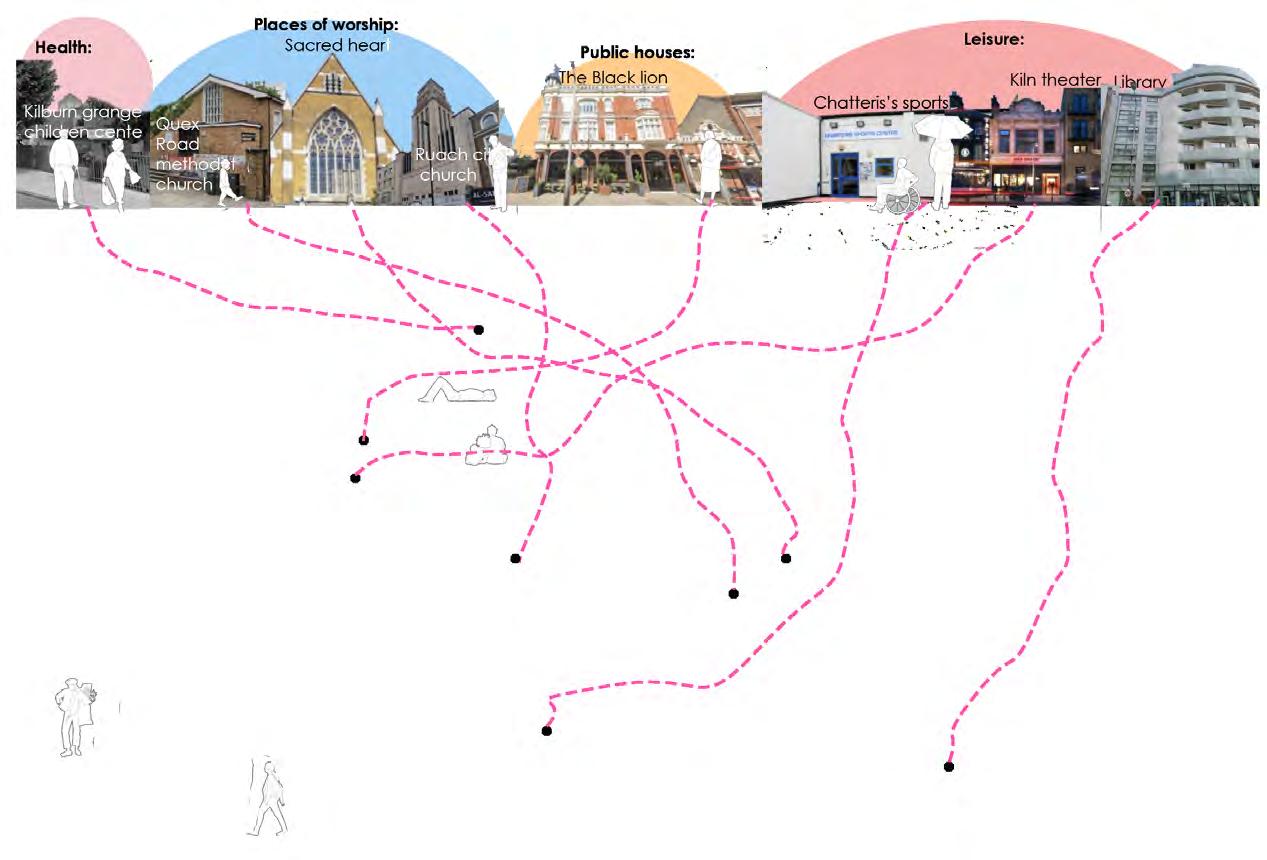

This poster is a graphical representation of a deep mapping exercise, capturing a mixed-methods approach to participatory planning. Through conversations, local knowledge sharing, and creative collaboration, it visualises the many people, places, and initiatives that shape Kilburn’s community life. Each diagram reflects a real connectionsocial, cultural, or spatial—within a dynamic network of mutual support and grassroots action. Created with and by the community, this map illustrates how shared experience, everyday practices, and collective care contribute to Kilburn’s identity. It is both a research tool and a celebration of the diverse, resilient, and collaborative spirit of the neighbourhood.

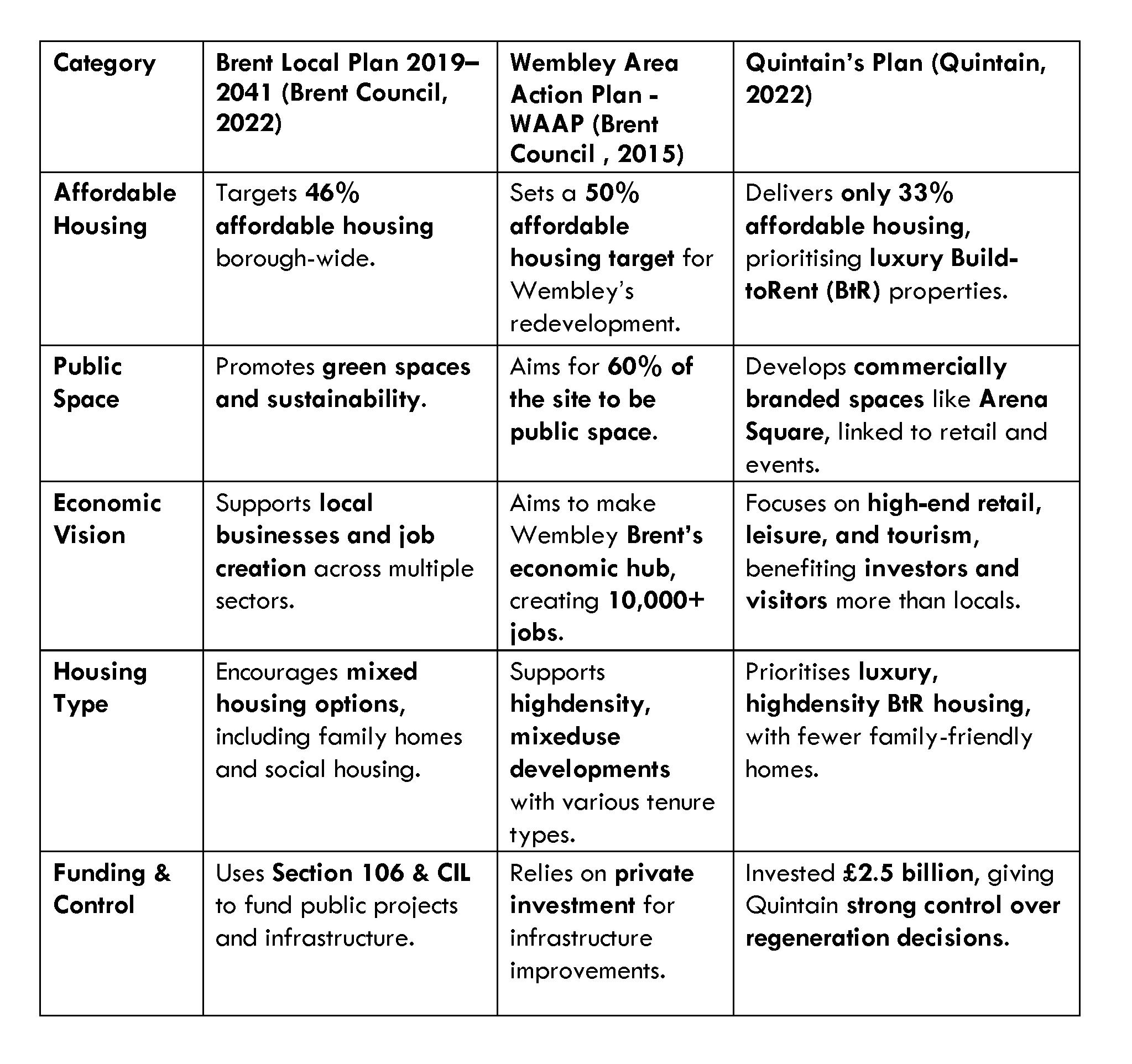

Alvin Tam, Ingrid Chan, Pragya Krishnan, Ziyi Liu

This project explores the Opportunity Areas (OAs) framework, driven by the GLA, and critiques its economic-centric model in regeneration as opposed to a co-creation outlook. Through investigating the opportunity areas of Wembley, Tottenham, Croydon and Canada Water, our project comes to a consensus that OAs have failed in effectively engaging with communities to co-produce space. As part of the BSP-Just Space Knowledge Exchange programme, we have been working on analysing the OA frameworks to better integrate community participation in intersection with development, to make for more inclusive city planning.

As part of the BSP-Just Space Knowledge Exchange Programme, we highlight the surface-level nature of community participation or co-production in our chosen Opportunity Area sites. The regeneration and economic-driven nature of an OA designation results in planning that places true community participation on the back burner. By subjugating community voices in favour of developer-led regeneration, OAs fail to listen and deliver on what our communities truly need — social housing and lifetime neighbourhood infrastructure. We outline a few points for future improvement: bringing back the ‘community’ into planning and being mindful of developer objectives.

Alvin Tam

Ingrid Chan

Pragya Krishnan

Ziyi Liu

Canada Water Masterplan Site (Allies and Morrison, n.d.)

British Land (BL) have been engaged in a process of consulting residents and local stakeholders, with six sets of public exhibitions that were accompanied by workshops, topic focus sessions and regular newsletters between stages of the masterplan evolution. From February 2014 to January 2018, over 10,000 attendees with more than 69 community consultation events, youth engagement programmes and outreach events. Baseline research of local social and economic conditions were also conducted.

A social regeneration charter was created by BL, with the Council and the local community.There was generally positive reaction to the Masterplan (London Borough of Southwark, n.d.).

Local community consultations included the Bermondsey and Rotherhithe Community Council, Canada Water Consultative Forum and Rotherhithe Area Housing Forum.

There is a development partnership between British Land (BL) and Southwark Council (Canada Water Master Development Agreement). The agreed-upon Masterplan covers 53 acres providing jobs, homes, offices, public spaces and facilities, with a maximum total of 737,186 sq. m GEA floor space. Permission was granted by Southwark Council in May 2020.

BL works with Southwark as both a regeneration partner and as a local planning authority on the planning application. (MDA) Southwark Council has a 20% interest in the Masterplan site and an option to invest in individual development plots or to sell out its interest (London Borough of Southwark, 2018).

There have been questions on the aspect of community participation. Consultations on the Tottenham Area Action Plan (AAP) were conducted with local communities including Northumberland Park and Tottenham Hale (Haringey Council, 2017). However, community groups such as the Our Tottenham network have reflected concerns on the during the AAP consultations, from typos and misleading site information to rushed six week consultation timeline. Members of the network were not given enough time to scrutinise council documents, and area forums in hotspots for regeneration such as Tottenham Hale were cancelled (Our Tottenham Planning Policy Working Group, 2015). Several studies explored the historic lack of community participation in the Tottenham area (see Panton and Walters (2019), Dillon and Fanning (2013; 2019), and Viitala (2018)).

A push for regeneration (at the cost of community consultation and participation) led to the creation of the Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV), a joint 50/50 private-public venture between Haringey Council and Lendlease. The venture was scrapped after extensive campaigning from the Stop HDV coalition and other community groups (including Our Tottenham), with the new leadership of Haringey stating that they disagreed with the 'large-scale transfer of public assets out of public ownership', choosing instead to focus on a council-owned development model (Barratt, 2018).

Due to its excellent transport connectivity and after the 2011 riots that swept up London and other UK cities, Croydon is currently concentrating on affordable housing provision by developing 7300 homes to accommodate 17,000 new residents, prioritising social infrastructure and regenerating public spaces with an especial focus on high streets, new offices and commercial spaces (GLA, 2025).

However, there are gentrification concerns, a criticism of inadequate community involvement in planning decisions (such as the exclusion of small business owners and local families), financial difficulties within the borough, not enough attention on affordable housing, and proposals on housing mixes and tenures not actaully being suitable for the demographics residing in the area (South West Londoner, 2016).

Wembley is one of 43 designated Opportunity Areas across London, identified as key locations to accommodate significant growth in housing and employment. According to the Wembley Area Action Plan (Brent Council, 2015), the area has an employment capacity of 11,000 new jobs and the potential to deliver a minimum of 11,500 new homes. As part of the wider regeneration agenda, developers Quintain purchased the land surrounding Wembley Stadium in 2002 and have since led a masterplanned, comprehensive redevelopment of the Wembley Park area (Brent Council, n.d.).

What particularly intrigued us was the divergence between the planning goals and the outcomes observed in actual development. The comparative analysis reveals variations between the objectives set out in local planning policies and

• Tensions exist between public goals (affordable housing, public space) and developer priorities (profit, high-end housing, and retail focus)

• Regeneration without community co-creation and input can often result in gentrification and worsening spatial inequalities

• Real community engagement is often neglected in favour of council-driven agendas, and change can only come from increased community campaigning and awareness amongst affected communities

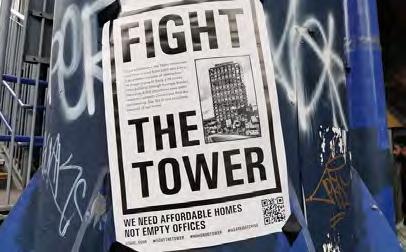

Co-creating a Brixton Neighbourhood Plan

Clara Chen, Joseph Cole, Emma Thümmel, Hannah Matthiesen, Nikitha Venu Gopal, Anise Chan, and Jeffrey Ng

Just Space Knowledge Exchange

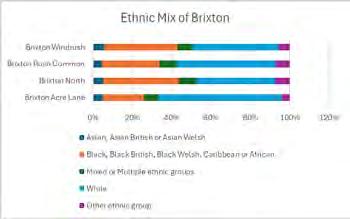

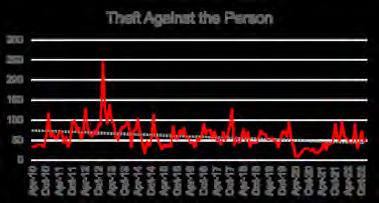

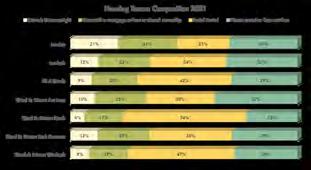

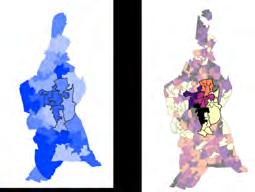

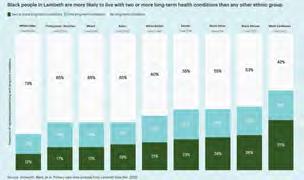

A group of 7 students at the Bartlett engaged in the UCL / Just Space knowledge exchange programme over the last academic year which aims to support the Brixton Neighbourhood Forum in creating a local plan. We provided statistical analyses and data visualisations to stimulate initial scoping conversations around the plan’s policy priorities with a view to support wider community engagement in the future. The experience has highlighted the complexity of communityled planning within a market-led planning system, as well as the need to marry professionalised planning knowledge with local expertise to create place-sensitive and democratic policies.

Brixton is a vibrant and dynamic neighbourhood in the South London borough of Lambeth It has experienced a significant degree of gentrification pressure sinc e the Brixton city challenge in 1993 which has seen the area transformed from a predominantly black, working class neighbourhood into a commuter district for wealthy young professionals

Community resistance to the social cleansing of brixton continues to this day most recently through the successful campaign to prevent the construction of a luxury 20storey office block in this historically low-rise district

Following this community victory the future of Brixton is now uncertain The Brixton neighbourhood forum (BNF) is therefore seeking to write a neighbourhood plan to address this shortcoming through a genuinely communityled alternative to local state-sanctioned gentrification

(following design a tion of the forum)

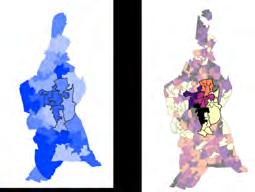

Our initial research sought to process and visualise the current “state of Brixton” within the policy priorities identified, as well as comparing ward level data to Lambeth, greater London and UK geographies We also aimed to analyse neighbourhood change over time and identify intersecting relationships between different policy areas

As we heard often in our initial scoping meeting statistical evidence is often at risk of being myopic and reductive, reflecting realities that often contradict or undermine the lived experiences of local residents We therefore intended for our evidence base to merely “set the scene” for detailed reflections on these lived realities, and for these discussions to shape where we would direct our attention This has created an environment of co-production and knowledge sharing between ourselves and the members of the BNF, and we are looking forwards to helping facilitate wider community discussions further down the line

Following the presentation of our findings related to each policy area we inserted a slide with a list of questions for the BNF members These included open-ended questions such as “Is there anything about this data that surprises you? and How should we refine our research?” In so doing we sought to create a democratic space of collaboration and knowledge exchange rather than the usual uni-directional presentation of “evidence” to the community

Our projec t has fa cilitated th e ver y earliest sta ges of th e mul ti-year process of creatin g a n eighbourh ood plan Our f irst m eetin gs with th e BNF have led to produc tive conversations about th e realities “on th e groun d” as well as th e disconn ec t between residents’ lived realities an d th e deta ch ed perspec tive of th e statistician

However, several key challen ges must be overcom e before m ovin g for wards Firstly, th ere are many different stakeh olders with conflic tin g visions about th e area An oth er local group is also seekin g to create a n eighbourh ood plan with overlappin g boun daries to th e BNF ’s It remains to be seen wh eth er collaboration between groups is possible Fur th er challen ges in clude a la ck of fun din g an d resources, ina ccessibility of data sources, an d lon g tim e scales requirin g sustain ed m om entum Th e realities of year-lon g postgra duate courses an d conflic tin g dea dlin es make suppor tin g th e lon g- term process of community plannin g challen gin g Never th eless, we have been proud to kick-star t this process, a ddin g an analy tical edge to th e BNF ’s policy priorities an d learnin g just h ow nuan ced a process m eanin gful “co - design” must be

Showcasing cross-sectoral approaches that bring together diverse urban systems, from health to industry, in co-creative planning.

Julien Davis

MSc Urban Design and City Planning

The project proposes a small-scale industrial symbiosis programme for an industrial area along the River Wandle, aiming to more efficiently redirect waste streams between businesses while fostering a more collaborative and ecologically conscious industrial culture.

• Wandle Valley, running along its River, was once a major industrial hub.

• Today various industries follow a wasteful linear “take, make, waste“ production model.

• This harms ecosystems and ignores the fnite nature of resources.

• Drawing from Industrial Ecology and Circular Economy Principles, Industrial symbiosis offers a circular, regenerative alternative where one industry’s waste becomes another’s resource. Goals

• Cut waste & boost resource effciency

• Foster communal spirit among local businesses

• Protect the River Wandle

PHASE 1 (12-MONTH ROLLOUT)

PHASE 2 (YEAR 5) PHASE 3 (YEAR 10)

Effective SME Industrial Symbiosis established within the area, waste streams matched, “Library of things” set up, a

is self

• Garratt Park’s Industrial Symbiosis draws from successful models like Kalundborg (Denmark) and CEBAS (Birmingham), where sustainability consultants at International Synergies led free waste-matching and training workshops funded by the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF).

• A similar 12-month rollout will be delivered in partnership with Wandsworth and Merton Councils, providing free fortnightly waste-matching workshops and expertise to local businesses. Within 5 years, a collaborative, circular ethos will take root, expanding across the Wandle Valley over a decade.

• Funding will be sought from the UKSPF, as well as the UKRI, Innovate UK, IETF, GLA, and local grants such as the Wandsworth Grant Fund.

BSc Year 3

Bringing together knowledge from different undergraduate modules like planning law, GIS and urban design, this personal final-year project of mine imagines a future in which communities, landscape and agricultural professionals come together to plant edible landscape across cities and towns. In doing so, food is recommoned, localised and becomes part of the landscaping. The plan not only imagines what communities can do at local level, but also what changes are needed at national level to institutionalise the Edible City concept and make it more widespread.

3.83 million people in Great Britain experienced chronic loneliness in 2022 (CtEL, n.d.)

7.2 million UK households were food insecure in 2022/2023 (FrancisDevine, 2024) Detatchment from nature deprives our food knowledge. Almost a third of UK primary pupils think cheese is made from plants, and nearly one in 10 secondary pupils thinks tomatoes grow under ground, according to the British Nutrition Foundation (Burns, 2013).

Communities, landscape and agricultural professionals come together to plant edible landscape across cities and towns, in parks, streets, gardens and any appropriate public spaces, and allow the grown food to be freely picked and taken by anyone.

The paradigm shift is altering the notion of food as a purely commercially traded product to also an interactive landscape element as well as a public good from public investment. Hence, having the edible plants being freely picked is not a worry of theft, instead it is to be encouraged.

physical and mental health

Food as free public good, take as one needs --> improve equity of access to food and mitigate food insecurity (similar to the spirit of free food distribution/food banks)

Food as an interesting and interactive landscape element, interactive in cultivation and in harvesting.

• Food as a visual educative element to improve people’s understanding about nature and awareness for conservation

Defnitely not infeasible. In fact, in 2008 a community group called Incredible Edible Todmorden started planting food in the public spaces around Todmorden in West Yorkshire and invited people to pick food freely. The group achieved some success by growing food on around 70 sites covering around 1 ha in Todmorden. Nonetheless, the practice is still not mainstream across cities after decades, and it remains questionable whether the intiative is only applicable to smaller towns or can it be applied widespread in large cities as well (Paull, 2003). Hence, this proposal reimagines how to facilitate and upscale the existing community-led efforts by institutionalising the Edible City concept at a higher level.

DEFRA would invest in the Edible City concept by giving grants to local authorities (LAs). With the funding, each LA would then have the statutory duty to prepare an Edible City Plan (example in 5.2) as part of the Local Plan. Funds would be used to hire landscape, horticulture and agricultural consultants to partner with local communities in the design of new edible landscapes. Besides, Edible City Managers would be employed to organise and lead local community volunteering for the long-term maintanence of the edible landscape. Nutritionists and the NHS can also be consulted for crop selection by examining local health data. With the environmental, public health and equity benefts mentioned in Section 3, the spending is not merely an expenditure but an investment, and a cost-beneft case can be prepared to properly examine this potential.

The 1908 Small Holdings and Allotments Act placed the duty on LAs (except inner London ones) to provide allotment gardens when demand arises (s.23). It also grants powers to LAs for acquiring land for allotments by lease, by compulsory hiring or (failing that) by compulsory purchase (s.25).

However, the individual farming nature of allotments does not provide the social benefts of co-farming. Moreover, equity issues exist. Waiting time can be as long as a decade in some councils, while a council-run plot can cost more than £100 a year. Since research have shown that allotments are most valued by users for mental and physical health benefts rather than economical value (Fletcher and Collins, 2020), it is proposed that the government terminates all existing allotment leases with one year’s notice and turn existing allotments into free common growing spaces maintained by volunteers, with produce that can be freely harvested by anyone. The Allotments Act is to be replaced by a new Edible City Act to bring forward the aforementioned initiatives, while LA’s strong power to acquire new land for edible landscaping will be retained in view of the acute climate emergency.

The bereaucracy of the planning system was mentioned by Incredible Edible Todmorden as an obstacle. Although change of use to agriculture does not consitute development and therefore does not require planning permissions per se (s.55(2)(e) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990), erection of ancillary structures, such as polytunnels and garden sheds, often constitute development. Currently, Part 12 of the General Permitted Development Order (GPDO) 1995 allows LAs to erect ancillary stuctures not exceeding 4 m in height or 200 m3 in capacity on councilowned land only. The GPDO should be amended to extend this concession to land designated for edible landscapes in the Edible City Plan, even if they are not owned by the council, albeit with a tighter size limit, to facilitate community transformation to an edible city.

LAs should take the lead to pilot the scheme on council-owned land to demonstrate the benefts to private landowners. For aristocratic landowners (who own lots of garden squares in London as an example), royal recognition can be considered for devoting their land to the

city. For private developers, S106 discounts can be given for delivering the 10% Biodiversity Net Gain in new development through the provision of edible landscapes that can be comaintained by residents.

To illustrate how to escalate the Edible City from a small-town phenomenon to mainstream in large cities, London is chosen as an example. Since LB Newham has high food insecurity risk and low existing allotment space per person (shown on the right), it is used as an example for developing an Edible City Plan. Also, the two maps on the right forms a good evidence base for funding distribution according to the different levels of need for new growing space.

Owing to more historical landscape and confned spaces, edible landscape in inner London should blend in with perennial landscape and have a stronger inclination towards the ornamental value of food planting, adhering to the character briefs of Conservation Areas if they fall into one. When Registered Parks and Gardens are affected, Historic England should always be consulted. Article 4 Directions can be used to remove permitted development rights when necessary.

While still emphasizing the aesthetical appeal of the “foodscape”, a slightly more farm-like approach can be tolerated in outer London with a greater focus on yield. For example, more raised beds and polytunnels can be used. Also, communities have more room and fexibility to design the space as they wish, with less prescription by landscape and convservation professionals compared to inner London.

A network of edible routes connect up the edible parks with the high streets. Edible high streets attract more footfall and add retail potential to the dwindling high streets, such as the Stratford High Street that saw its retail activity absorbed by the new Westfeld Mall nearby.

With the support for food growing from London Plan Policy G3 8.3.1, several Metropolitan Open Land and other designated open spaces were selected for edible planting.

This section gives some indication on how an edible city might look. Selection of plants should take into consideration factors like seasonality, lifespan, ease of maintenance, visual interest, ecosystem impact, nutrition, historical context, etc.

Basil is planted as hedges in front of Gandhi’s statue, not only because the herb is of spiritual importance in Indian culture, but also because its similarity to boxwood makes it a good ornamental edge.

Perennials with longer lifespan like blueberry shrubs are planted to complement basil to avoid the landscape becoming bare when basil is harvested.

Mixed with non-edible perennials like Mediterranean Spurge for better ornamental outcome.

Sweetcorn to be planted in sunlit areas, chosen for its ease of maintenance in inner London with more transient population.

Edible lavender chosen to line the street because of its calming effects.

Apple trees street orchard provide visual interest in terms of seasonal variety with fowering and fruiting, and act as pollinatorfriendly plants.

In raised planter boxes, lettuce is grown in warmer months and kale is grown over the winter, following planting seasons and adding temporal variety to landscape.

Underutilised spaces can be converted for food-growing. Polytunnels and raised beds are more acceptable in less landscape-sensitive areas. Local residents around are encouraged to bring their food waste to edible gardens for composting. No-dig gardening utlising organic mulch is preferred to conserve soil.

Information boards with QR codes are put up to help people identify what plant it is and when it is suitable to be picked.

St. Mary’s Hospital: Creating a Future-Ready Healthcare District

Adhrita Roy

MPlan City Planning, Year 1

This coursework from Urban Design: Space and Place is a project on redesigning a section of a site in Convoys Wharf. In my work, I aim to build a co-living community with environmentally friendly and social gathering features embodies the theme of Co-Creation by fostering shared ownership, collaboration, and inclusivity. Reflecting from existing case studies from around the world and taking residents’ interactions into consideration, 3d models and after images are created to resemble how the area functions and is used by its residents. The integration of green features, heritage assets and communal areas encourages dialogue and shared experiences, reinforcing community bonds. In essence, the project is a showcase of co-created values where social wellbeing are built together.

ADHRITA ROY

PROJECT CONTEXT

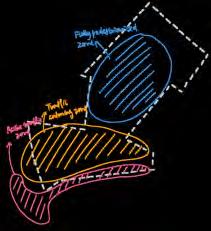

St. Mary’s Hospital, while being one of the biggest trauma centres in London, faces many problems which adversely affects its day to day activities. Among these issues, the three in particular that this project aims to address are - the lack of infrastructure required to accommodate modern healthcare needs, lack of legibility and way-finding in the area; and a severe shortage of public green open space causing Urban Heat Island (UHI) in the effect in the area. Also aligning with St. Mary’s requirement of having an operational hospital throughout the course of the redevelopment, the project proposes a phased development plan for the site - to build a future-ready healthcare and research district in the area.

Approach taken: Acknowledging, reviewing and augmenting existing policies and plans.

EXISTING SITE CONTEXT AND CONSIDERATIONS

Grade I listed building

Grade II listed building

Edgware Road

Westway

Area for growth

Parking Area

Revised site boundary

Poor pedestrian paths

Existing pedestrian paths

Imperial College Medical School

RECOMMENDED PHASED IMPLEMENTATION STAGES PROPOSED (1 to 4)

Buildings to be demolished Pop-up clinic

New medical centre Creating green nodes

Building to be demolished Development of pathways

VISION FOR THE REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT

Creating a future-ready healthcare district which co-locates ‘neighbourhoods’ of medical excellence, education, leisure and research excellenceredefining St. Mary’s Hospital as a world-class medical hub.

Objectives :

- Promote phased development to protect and promote existing heritage, while creating new, flexible floor space for newer functions.

- Promote vertical densification through co-location of services - to protect existing, and create additional public, green open space.

- Increase way-finding within the area through clustering of related functions and use of intuitive signage mechanisms.

PLANNING FRAMEWORK CHANGES

Westminster City Plan Paddington Place Plan

New planning policies

Creating a “Healthcare & Research Special Policy Area (SPA)” in the Paddington Opportunity Area

Establishing tax benefits in SPA; to alleviate St. Mary’s financial burdens and promote joint ventures between NHS, universities, and biotech companies, ensuring financial sustainability for medical innovation.

Apart from the medical departments, all buildings within the SPA must dedicate 50% ground floor space to shareduse innovation hubs for students and researchers; and leisure or co-working spaces for other users of the place to allow optimal co-location of functions.

Amending existing policies

Recommended additions to existing City Plan 2019-2040 objectives for a Fairer Westminster:

1. Outpatients building demolished. Patients directed to Charing Cross, Hammersmith, and University College London Hospitals. Pop-up clinic in front of Paterson building to attend to additional patients.

2. Building new hospital in place of the Outpatients building. Relocating other scattered medical services, including ones at Salton House to the new building.

3. Developing the open nodes and waterside areas with walking and cycling routes. Demolition of Salton House and creation of new building for Paddington Life Sciences.

4. With new buildings dedicated to medical care and research; development of green park and nodes to spatially segregate the areas; and routes with colour-coded signage to increase way-finding - it would reinforce the idea of ‘neighbourhoods’ within the ‘healthcare district’.

Restricted private vehicle access

Site boundary

Edgware Road

Westway

Green nodes

Area for medical care

Area for education

Area for research

Public green space

Improved paths for pedestrians and cyclists

4a Broaden cultural offer at Paddington Opportunity Area by establishing museum in collaboration with Imperial College and St. Mary’s to highlight the rich history of the area and engage public interest.

5a Promoting low-traffic zones along Praed Street by zoning private vehicle access and prioritising emergency vehicles, walking, cycling and public transportaddition to Paddington Bayswater High Streets programme

10 Encourage innovations in building technology and improve sense of place.

- Protecting and enhancing uses of international and/or national importance, the buildings that accommodate them.

- Prioritising sustainable travel

- All developments within SPA will adopt designated colour schemes, landscaping and interactive signage at service entrances for intuitive way-finding.

CONCLUSION

Conclusion: The redevelopment of St. Mary’s Hospital creates a well-integrated healthcare district which while improving the functionality of the hospital; helps create a sense of ‘destination’ in the area. Done by facilitating vertical densification and creating well-demarcated ‘neighbourhoods’ for medical care, education, leisure and research - it protects and creates new public green space for all users of the area. This is further augmented by the recommended phased redevelopment plan - which allows the hospital to remain functional throughout the process.

Ziru Huang

This individual masterplan design focuses on a selected section of the broader redevelopment strategy for Convoys Wharf, which was collaboratively developed among our group members through site visits, community interviews, and spatial analysis. The proposal aims to future-proof the site through a human-centric approach that promotes social equity and long-term sustainability, incorporating strategies such as sustainable residential blocks, low-traffic neighbourhoods, and inclusive public open spaces. These design decisions respond directly to insights gathered through community engagement, reflecting principles of co-production by integrating local voices into planning and spatial design. The project will be presented at a community planning forum organised by Voice4Deptford, fostering open dialogue with local stakeholders and supporting an ongoing co- creation process in shaping the area’s future.

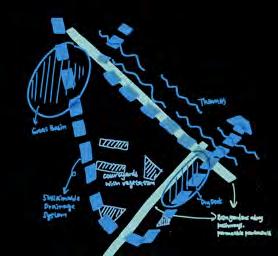

Stepan Adamenko

BSc Year 2, Winner of the 2024 LDA Design Bursary Competition

This proposal explores how co-design can nurture place-specific responses to complex, nationwide challenges such as deepening social inequality and the evolving climate crisis. It envisions revitalising Great Yarmouth by embracing nature, restoring vital habitats, and living harmoniously with the sea. At its heart is the Communal Upskilling School, empowering local residents with industry-specific skills for the emerging offshore wind industry. By fostering education, resilience, and collective prosperity, it seeks to rebuild a stronger, fairer, and more sustainable coastal community.

This project aims to “rise together” economically and socially as a whole community, along with the rising tide, which means living together with nature and the ocean. This idea is informed by the history of the city where in the early 20th century, the herring industry brought together fshermen, Herring-Lassies (seasonal female workers), and supporting industries, creating a bustling and circular economic ecosystem, as well as fsherman adapting to the herring’s natural migration patterns.

This is a priority for the government as it fosters a collective mindset shift towards just, sustainable growth— working with nature, not against it. Great Yarmouth ideal for his frst step, attracting over £39bn to be invested in the next 20 years in its new industry of offshore-wind energy but leaving the people and nature behind, being in the 10% most deprived areas in England (2019), as well as suffering from food risk. If successful, the initiative may be expanded to other struggling coastal cities.

This foodable public space transforms into a temporary, elusive pond during high water events. It emphasises living harmoniously with the sea, transforming a threat into a special, feeting moment. Creating community assets, not just food defences.

Half of Great Yarmouth faces a threat of

The Rows since 12th century were Great Yarmouth’s unique narrow alleyways, lost in the 20th century. Reviving this urban form is in line with government’s recent embrace of new-urbanist agenda. City government owns lots of foodable land and by incorporating stilts could develop much needed social housing, while preserving wildlife. People from diverse backgrounds may live closer, fostering community in an era of increasing individualism. The approach might be extended UK-wide

“a jolly neighbourly race, who like, out of pure good fellowship, to be always in talking and handshaking distance of each other.”

Great Yarmouth’s offshore wind industry sees most benefts fow elsewhere. To ensure local wealth creation, the industry must expand beyond energy production into decommissioning, recycling, and energy storage. A wind turbine materials recovery hub would create long-term, skilled jobs in

maintenance, component repurposing, and second-life battery storage. This strengthens the local economy, supports grid stability, and ensures a fully circular wind industry. As this “rising together” project expands to other coastal towns, deeper waters and stronger tides could support foating offshore wind farms and tidal energy infrastructure, ensuring a just transition into a decarbonised future.

Four-tiered sand dunes will reconnect the city with the sea through restored habitats. Elevated pathways on stilts ensure food resilience while preserving delicate ecosystems.

This will empower local residents to enter the offshore wind industry by gaining relevant skills and qualifcations. Companies investing in the city will contribute by providing their industry professionals as educators. The school will offer apprenticeships, hands-on training, and feld trips across the city, creating a direct pathway from learning to local employment.

Highlighting projects that apply co-production to address local needs through strategic regeneration.

Battersea Power Station Reimagined: Consumption to Community

Lauryn Chan, Hannah Clarke, Lucas Van Den Oever

BSc Year 2

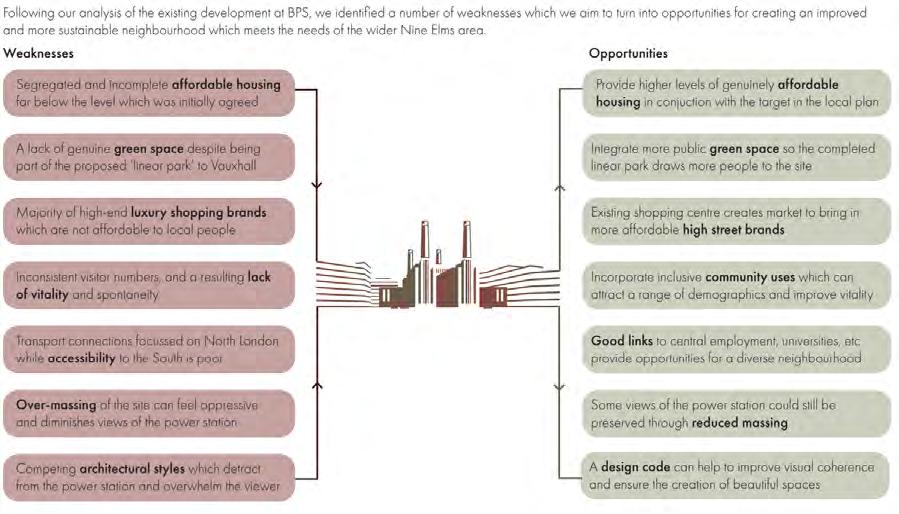

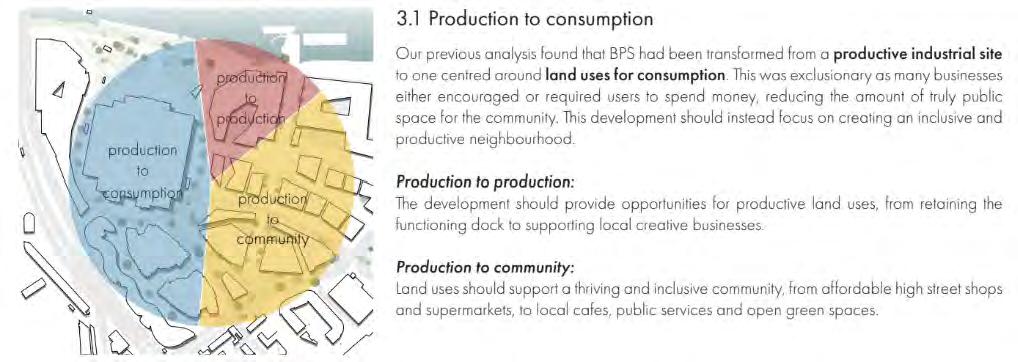

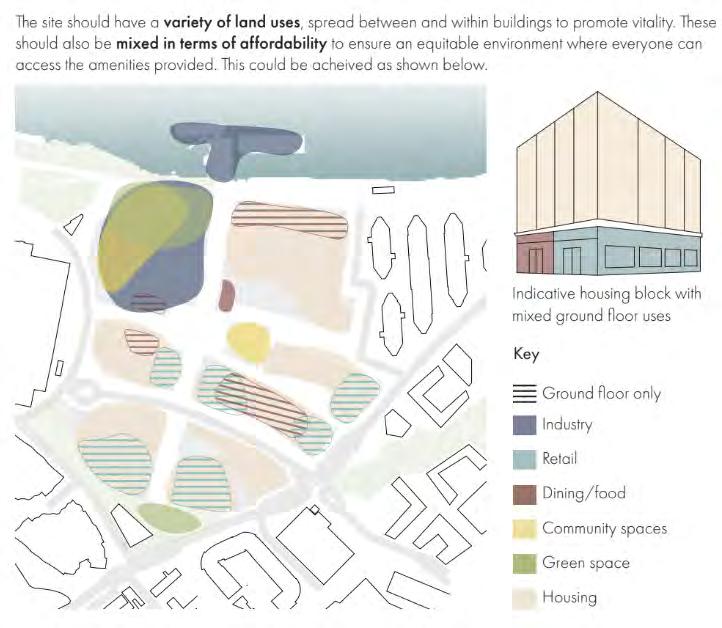

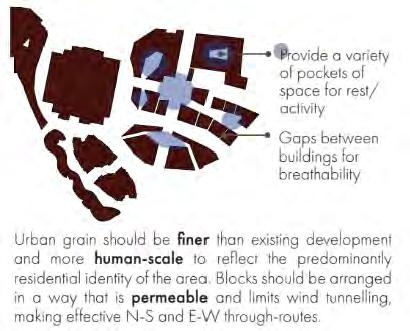

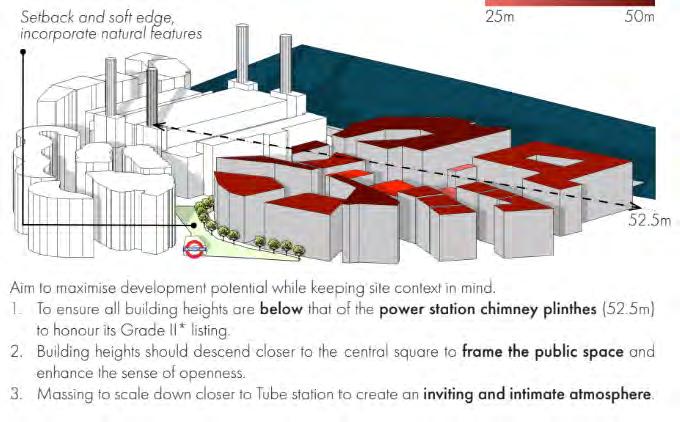

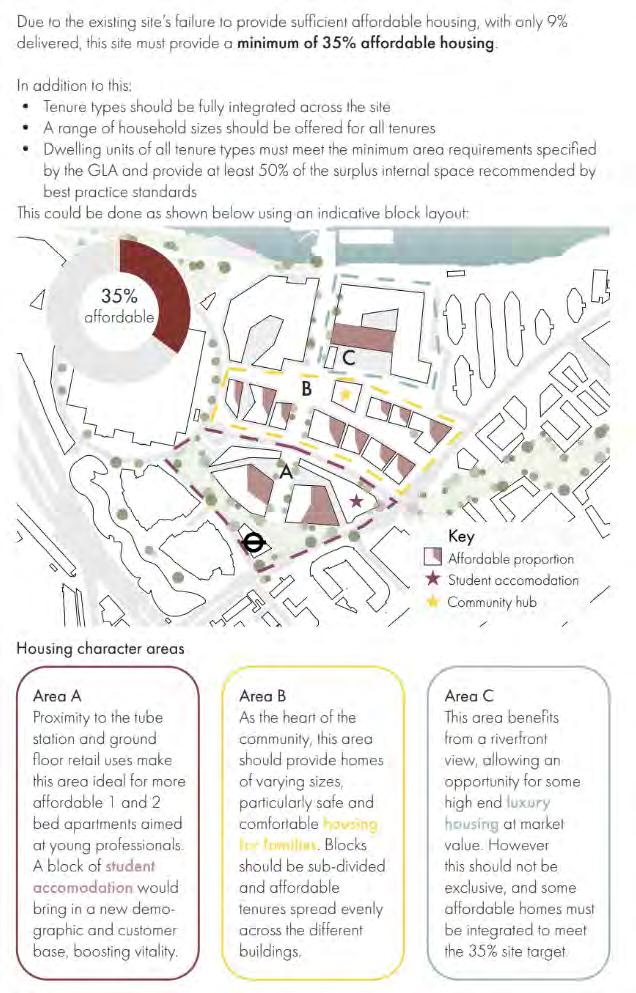

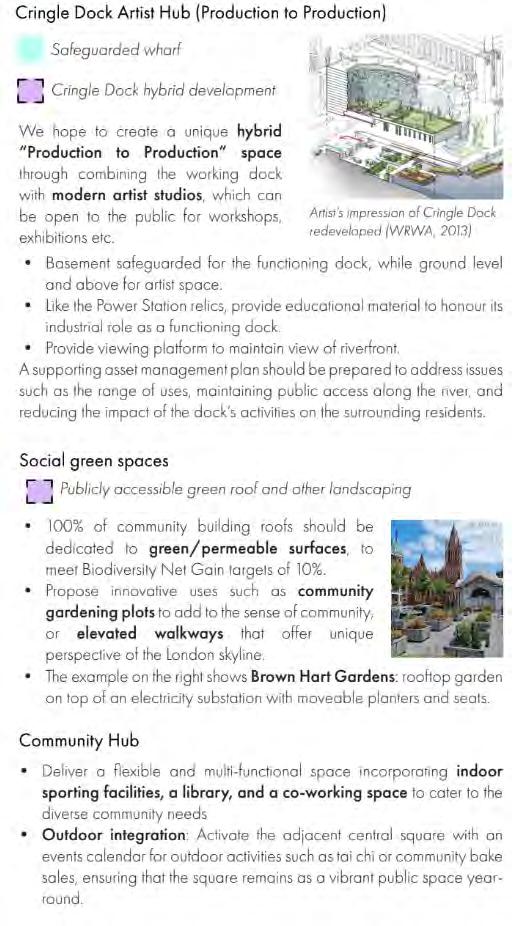

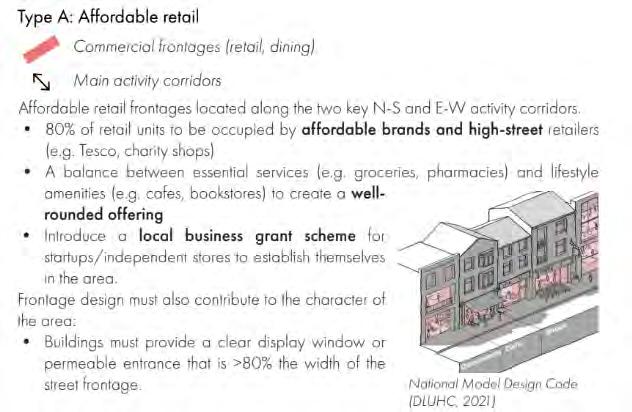

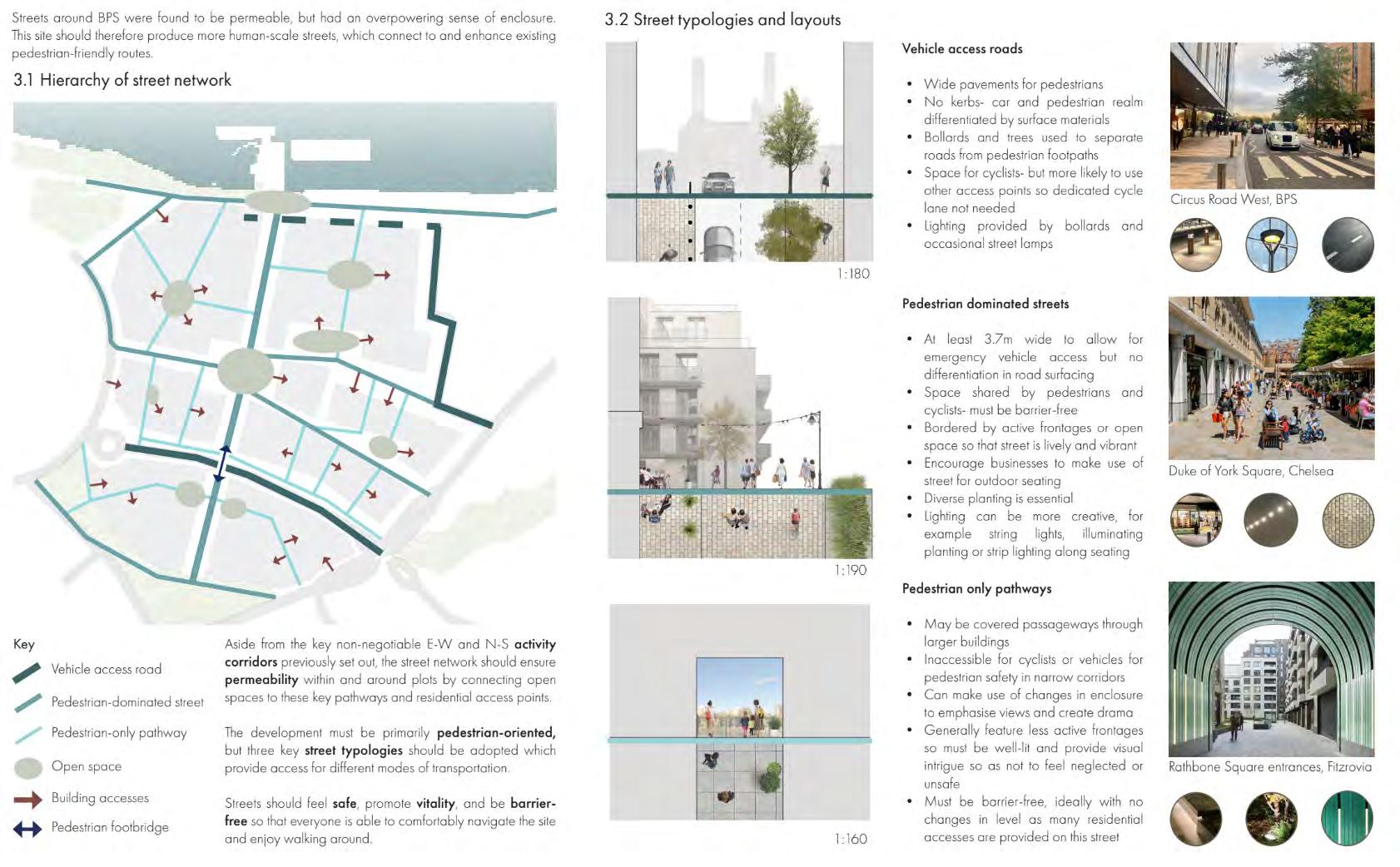

As part of our BPLN0078 Urban Design module, we analysed Battersea Power Station’s redevelopment. We identified key issues: overwhelming architecture, exclusive design that alienates locals, poorly defined public-private boundaries, discrimination against low-income residents, and financial challenges. Our proposal, a community-centric space, rectifies these imbalances through co- creation and bottom-up planning. We shift from prioritising an “urban visual spectacle” to inclusive placemaking. We aim to bridge the gap between the power station and its neighbourhood, cultivating a warm, organic community, built with and for its residents.

Once a cherished industrial landmark, the redeveloped Battersea Power Station has been transformed into a vibrant twenty-first century destination.

4.

5.

5.

The previous phases of the wider BPS development have thrown the site into imbalance What exists now is glitzy, glamorous and sleek — but ultimately cold Excessive focus on exclusivity and spectacle has resulted in a place that welcomes Londoners, but alienates those living on its doorstep. The power station is an ‘attraction’ rather than a ‘place’, somewhere people go once or twice before the novelty wears off, which is an unsustainable characteristic in the long term. Our vision of the site intends to bridge the gap between the power station and the surrounding neighbourhood, reintroducing a sense of warmth and organic community to the development. This new addition will be more accessible, approachable and enduring, welcoming people from all over London but primarily serving the local area We advocate for several non-negotiables in our bid to achieve this, the most important of

creative space for artists of all kinds, bringing a sense of personalisation and self-expression to the site and reintroducing an ethos of production and creation.

ethos of production and creation.

To create a new mixed-use neighbourhood that is simultaneously distinct from and integrates seamlessly with its surroundings, fostering a diverse and tight-knit community in a place which radiates comfort, vitality and most importantly, warmth.

To create a new mixed-use neighbourhood that is simultaneously distinct from and integrates seamlessly with its surroundings, fostering a diverse and tight-knit community in a place which radiates comfort, vitality and most importantly, warmth.

The £9 billion project, which launched the first two of its seven phases in 2022, is set to establish a dynamic, mixed-use development that will create an entirely new neighborhood and business hub for London. This ambitious vision includes a Zone 1 extension of the Northern Line on the London Underground and the meticulous restoration of the iconic Grade II* listed Power Station.

To create a new mixed-use neighbourhood that is simultaneously distinct from and integrates seamlessly with its surroundings, fostering a diverse and tight-knit community in a place which radiates comfort, vitality and most importantly, warmth.

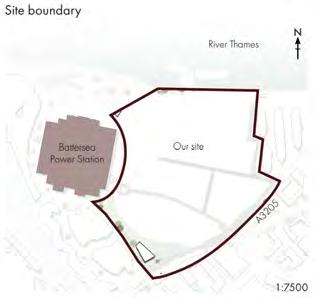

Our site is the remaining undeveloped phases of the wider Battersea Power Station (BPS) development. The development is located on the south bank of the River Thames in the borough of Wandsworth, and is part of the wider Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea opportunity area. Situated next to the restored power station, our site provides the basis to create an exciting new mixed-use central London neighbourhood that actually meets community needs.

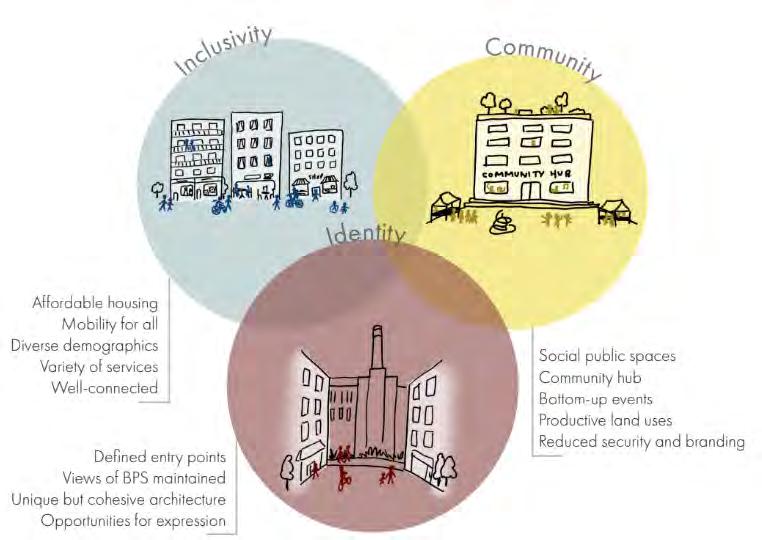

In our aim to achieve this sense of warmth, we propose three values which must guide development processes. The seven development parameters outlined in this brief are based on these values, breaking them down into smaller, actionable objectives.

Inclusivity

In our aim to achieve this sense of warmth, we propose three values which must guide development processes. The seven development parameters outlined in this brief are based on these values, breaking them down into smaller, actionable objectives.

In our aim to achieve this sense of warmth, we propose three values which must guide development processes. The seven development parameters outlined in this brief are based on these values, breaking them down into smaller, actionable objectives.

Inclusivity

• Homes should be accessible and affordable to as many people as possible, catering to people with a variety of backgrounds. Segregation of housing types into certain sections of the site is unacceptable.

Inclusivity

• Homes should be accessible and affordable to as many people as possible, catering to people with a variety of backgrounds. Segregation of housing types into certain sections of the site is unacceptable.

• The site must allow for universal mobility both in terms of initial access and movement within.

• The site’s facilities should be open and welcome to all in both in appearance and in practice.

• Homes should be accessible and affordable to as many people as possible, catering to people with a variety of backgrounds. Segregation of housing types into certain sections of the site is unacceptable.

• The site must allow for universal mobility both in terms of initial access and movement within.

• The site must allow for universal mobility both in terms of initial access and movement within.

• The site’s facilities should be open and welcome to all in both in appearance and in practice.

• The site’s facilities should be open and welcome to all in both in appearance and in practice.

Community

• The site should be designed to facilitate social interaction.

Community

Community

• The site should be designed to facilitate social interaction.

• The site should be designed to facilitate social interaction.

• A variety of retail, services and public uses must be available to encourage the creation of a village-like atmosphere and a sense of locality.

• Public consultation must be strongly considered, with excellent justification if not implemented.

• A variety of retail, services and public uses must be available to encourage the creation of a village-like atmosphere and a sense of locality.

• A variety of retail, services and public uses must be available to encourage the creation of a village-like atmosphere and a sense of locality.

• Public consultation must be strongly considered, with excellent justification if not implemented.

• Public consultation must be strongly considered, with excellent justification if not implemented.

Identity

The VNEB Opportunity Area’s ambitious 2030 completion target promises to deliver a distinctive urban quarter, with plans carefully orchestrating tall building clusters and a linear park connecting Battersea to Vauxhall. However, the development faces mounting challenges around long-term profitability, driven by limited affordability, intense retail competition, and a potentially oversaturated luxury housing market. Political influence

Identity

Identity

• The site should have some level of visual uniformity and defined entrypoints, both of which give a clear sense of entering the area.

• There must be many opportunities for sponteity and self-expression, giving the site character and personality.

• The site should have some level of visual uniformity and defined entrypoints, both of which give a clear sense of entering the area.

• The site should have some level of visual uniformity and defined entrypoints, both of which give a clear sense of entering the area.

• There must be many opportunities for sponteity and self-expression, giving the site character and personality.

• The site should be unique, a characteristic achieved by responding to its context both functionally and aesthetically.

• There must be many opportunities for sponteity and self-expression, giving the site character and personality.

• The site should be unique, a characteristic achieved by responding to its context both functionally and aesthetically.

The future of BPS is complicated by recent political shifts, marked by the new Wandsworth Labour administration’s boycott of BPS’s launch over affordability concerns - a clear departure from the previous Conservative council’s pro-development approach.

The two renders below provide more detail as to the kind of atmosphere our vision aims to inspire.

• The site should be unique, a characteristic achieved by responding to its context both functionally and aesthetically.

The two renders below provide more detail as to the kind of atmosphere our vision aims to inspire.

The two renders below provide more detail as to the kind of atmosphere our vision aims to inspire.

The project’s success will hinge on managing commercial and social expectations in a changing political climate.

Participation-centred approach

While community consultation strategies at BPS were comprehensive, this ultimately seemed to be performative as key concerns such as housing affordability were ignored. This can be avoided by:

1. Encouraging a diverse range of interest groups and demographics to participate through varied consultation methods

2. Acting on negative feedback and concerns and demonstrating this to the community, ensuring consultation is genuine and not tokenistic

3. Providing a range of public outdoor and indoor spaces, and genuinely affordable housing

4. Offering opportunities for involvement, for example through co-design of the community spaces for expression through art installations or sculptures

5. Allowing for bottom-up and more spontaneous management of events programmes, particularly in the use of the proposed central square and Cringle Dock studio space

Enfield for Everyone: Creating Mixed Neighbourhoods

Lauryn Chan

BSc Year 2

As part of BPLN0082 Spatial Planning Projects, my submission aims to address Enfield’s ambitious growth targets of 31,000 new homes and 30,000 jobs by 2041. In response to challenges of inequality, weak social capital, and limited accessibility, the plan embraces participatory design processes to realise the Leipzig Charter’s vision of a Just City. By working collaboratively with local communities, the strategy promotes the development of mixed-use neighbourhoods that integrate diverse housing, equitable employment opportunities, and essential services. This approach places residents at the heart of shaping resilient, inclusive spaces, ensuring that Enfield’s growth is both sustainable and truly reflective of its people’s needs.

In pursuit of Enfeld’s ambitious targets of 31,000 additional households and 30,000 new jobs by 2041, this spatial plan responds to the pressing need for impactful solutions that will address existing community issues and accommodate future population growth. Recognising Enfeld’s challenges in achieving the Leipzig Charter’s Just City principles, the strategy aims to improve accessibility to essential services, foster mixed housing, and create equitable local employment opportunities. By prioritising mixed-use neighbourhood units, this plan seeks to build resilient, inclusive communities while ensuring sustainable and equitable growth.

Improve accessibility to high-quality & locally-grown retail, cultural and civic service provisions by introducing more, expanding, and intensifying town/district/local centres.

With the growing population, new retail centres are needed to cater to increasing needs for services & employment, especially for severely underserved areas.

Under-served areas (outside a 20min Active Travel Zone)

To introduce new local centres in severely underserved areas.

To introduce new communitygrown local centres in severely underserved areas.

To expand existing district/location centres towards slightly underserved areas.

Unemployed,

edu, commutes out

To safeguard and intensify existing town/ district/local centres.

East-West divide along the A10

To focus on introducing more vibrant public spaces such as plazas, markets and cultural space in areas with the largest disparities in IMD.

To improve public realm in residential areas with highest IMD.

New large-scale builds with an equitable mix of housing sizes and tenure.

To safeguard and intensify existing SILs

study 1: Canning Town, Newham Best practice for co-creation and regeneration of neighbourhoods as a whole.

Site context

Similar to East Enfeld, Canning Town is an area of high deprivation and A13 that separates the area into two.

Commissioned and led by the Borough of Newham, its regeneration aims to co-create a new mixed-use town centre with homes and leisure facilities by engaging with local residents.

Co-creation process

• Multiple outreach exercises: At all stages of design process (masterplan, public realm, sound barrier etc), : co-design workshops, steering groups, on streets, coffee QnA sessions

• Inclusive: Exercises for all demographics (e.g. school activities, special home visits for vulnerable housebound members of community)

• Resident ballot: Residents given the right to veto the Canning Town regeneration

TCs will frame the development of the other strategic objectives to push for (i) co-located homes, jobs and services, (ii) compact neighbourhoods and (iii) social mixing across residents and employees.

Some TCs can be expanded to meet needs of underserved areas, and also have the infrastructural/spatial/developmental potential to be expanded/intensifed. These TCs must evolve into multifunctional hubs that accommodate a diverse range of town centre & community land uses.

new community- grown local centres

New local centres can be introduced in extremely underserved clusters outside of a 20min Active Travel Zone (as identifed in Task 1) to facilitate regeneration and connectivity. These centres must be co-created with active community participation to establish a unique local identity for a new centre, lacking in existing heritage.

• Civic infrastructure: Every local centre

• Diverse land uses: Must enhance the existing range of uses, ensuring provision of leisure, cultural and community services besides commercial activity. Mixed-use with residential/ offce on top is encouraged.

• Strategic spatial expansion: Growth is restricted to designated underserved areas identifed in the policy map. Else, TC should be intensifed via airspace development/colocating day & night activities

• Public space improvements: CIL contributions should fund safety and placemaking improvements to open space.

•

To intensify existing town/district/local centres.

To expand existing district/location centres towards slightly underserved areas.

At least 4.2ha of TC space needed for:

31,000 new households

2,800 jobs in retail/ F&B

*TCs are defned as town/ district/local centres

Proposals to safeguard and introduce/expand TCs must:

1. Emphasise connectivity and convenience for all residents to essential services

2. Encourage social mixing across different demographics by expanding and enhancing public spaces especially across the A10, and in new mixed-housing neighbourhoods like Enfeld Chase.

• Viability: Each phase of the scheme was ensured to be independently viable, yet integrated seamlessly with other phases and surrounding areas iin Canning Town

• Balanced social and economic benefts: relating to jobs, both affordable and private housing, community space, and support services for local businesses

• De-risking: Extensive consultations help reduce regulatory uncertainty and planning objections/delays, derisking the site. The council therefore attracts developers willing to accept lower proft shares, ensuring more affordable housing, public benefts and longterm community gains.

• Distinct, unique mixed-use neighbourhoods that have the close-knit feel

• 1,500 new homes (50% genuinely affordable)

• Larger, intergenerational dwellings

• Improved public realm with communial gardens and playspaces

• New shops, supermarket, offce space

• Improved connections along the A13

Similarly for Enfeld, ensuring new & improved TCs develop successfully is critical to enhance its attractiveness and support the other broader strategic goals of fostering mixed neighbourhoods and equitable employment.

Leverage community-governance models for town centres

Encourage local stakeholders to take ownership of TC development by acquiring and repurposing assets for social and economic beneft:

1. Support Community Land Trusts and cooperative models for retail, workspace and civic uses

2. Facilitate partnerships between local businesses, residents and councils to shape the long-term stewardship and identity of TCs

Isis Ciurleo

BSc Year 3

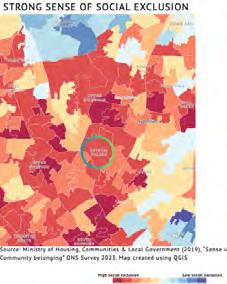

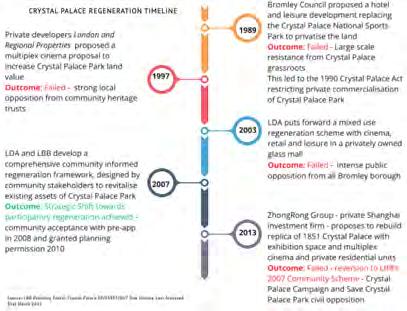

We explore the Crystal Palace Park regeneration as an evolving model of co- creation, where civil society actors are embedded within formal governance structures. It reflects a shift from market-led planning towards participatory, negotiated processes that foreground discursive engagement and community agency. By tracing how power, funding, and institutional roles are redistributed through mechanisms like the Crystal Palace Park Trust, we highlight co-creation potential—and limits—under fiscal constraint and political asymmetry. We reveal how co-creation is not simply a method, but a contested and contingent process within contemporary urban governance.

The Crystal Palace Regeneration Project is a major urban renewal initiative to restore one of London’s most historically significant public parks. Opened in 1854 by Queen Victoria, Crystal Palace Park is aGrade II listed landscape with 8 heritage structures, sports facilities and green space for South London’s diverse communities.

The Project departs from market-led approaches, positioning the regeneration as a rare model of participatory urban governance.

Years

Community

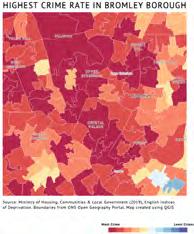

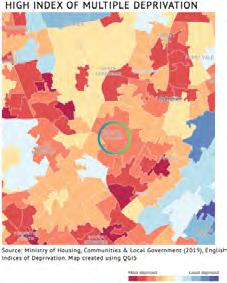

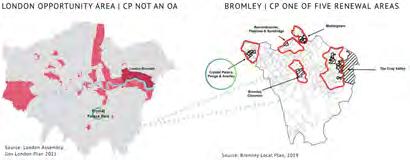

The CP regeneration re ects a state-led model shaped by multi-level governance tensions between the Conservative-led LBB and Labor led GLA. The GLA does not designate the park as an opportunity area but instead as a Metropolitan Open Land, limiting strategic investment potential. Bromley’s Local Plan however identifies the park as a strategic Outer London Development Centre feeding into Bromley’s five strategic renewal zones, supporting growth-oriented investment.

LBB’s initial plan for 210 homes with no a ordable housing faced GLA opposition due to MOL protections, leading to a revised scheme with 18% a ordable units as a cross-subsidy. Though it generated only £2.8 million in public funds, it met viability tests— highlighting the state’s dual role as regulator and facilitator, and its reliance on negotiated outcomes over planning principles

Transport policy reveals similar tensions: Bromley blocked the Croydon Tramlink extension over MOL concerns—despite easing these for housing—while expanding car parking based on claimed community preference. This selective interpretation and symbolic use of community rhetoric bolstered Bromley’s negotiating power and reinforced local autonomy.

1 Entrepreneurial planning under austerity - Bromley’s reliance on land value uplift re ects Weber’s (2021) and Penny’s (2022) view of the local state as an entrepreneurial actor, using planning to generate capital rather than redistribute it

A Test of State Power From Private Deals to Public Demands Between Civil Emancipation and Constraint 11| Conclusion

2 Selective governance and spatial asymmetry As Raco et al. (2018) and Hillier (2003) note, planning now manages risk and facilitates growth, leading to fragmented governance—as seen in Bromley’s carled priorities over regional transit.

3 Community rhetoric as legitimation - Drawing on Bunce (2016) and Harvey (1989), Bromley uses community discourse to justify growth interests, reinforcing local state power while obscuring deeper structural inequalities.

3

Unlike traditional public-private partnerships, private sector actors contribute technical expertise and delivery capacity for the CPP through contract-based specialist input rather than capital investment.

This marks a shift from Bromley’s earlier market-led approach, typified by the failed £500m ZhongRong scheme—rejected for lacking transparency and community input. It exposed the risks of “shadow planning” (Rogers & Murphy, 2013) and elite-driven growth, which this regeneration now seeks to move beyond.

organisations mark a broader success in reversing community

1

1 Entrepreneurial governance & land commodification - As Harvey (1989) and Weber (2021) show, Bromley’s backing of the ZhongRong scheme re ects growth-led governance, using land as a financial asset to o set fiscal deficit through land commodification

2

Shift toward hybridity - The state now leads delivery through contract-based private roles, re ecting Colenutt et al. (2015) on viability-led planning and a shift toward civil-sector funding and public accountability.

Inclusive Co-Living: Building a Sustainable and Accessible Neighborhood at Convoys Wharf

Belle Yan

BSc Year 3

This coursework from Urban Design: Space and Place is a project on redesigning a section of a site in Convoys Wharf. In my work, I aim to build a co-living community with environmentally friendly and social gathering features embodies the theme of Co-Creation by fostering shared ownership, collaboration, and inclusivity. Reflecting from existing case studies from around the world and taking residents’ interactions into consideration, 3d models and after images are created to resemble how the area functions and is used by its residents. The integration of green features, heritage assets and communal areas encourages dialogue and shared experiences, reinforcing community bonds. In essence, the project is a showcase of co-created values where social wellbeing are built together.

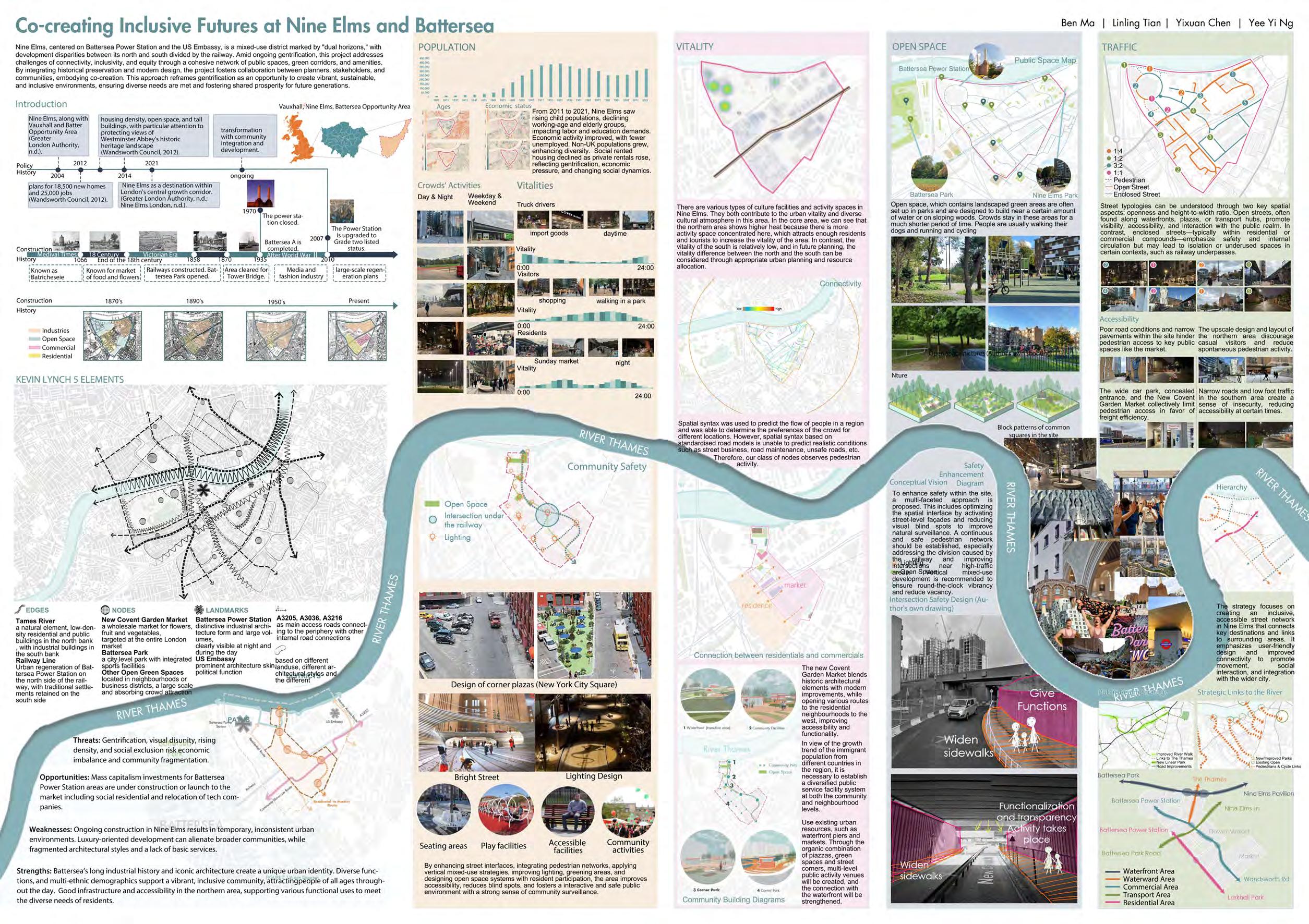

MPlan City Planning

Nine Elms, centered on Battersea Power Station and the US Embassy, is a mixed-use district marked by “dual horizons,” with development disparities between its north and south divided by the railway. Amid ongoing gentrification, this project addresses challenges of connectivity, inclusivity, and equity through a cohesive network of public spaces, green corridors, and amenities. By integrating historical preservation and modern design, the project fosters collaboration between planners, stakeholders, and communities, embodying co-creation. This approach reframes gentrification as an opportunity to create vibrant, sustainable, and inclusive environments, ensuring diverse needs are met and fostering shared prosperity for future generations.

Focusing on spatial strategies that foster inclusion, mobility, and stronger social ties in the built environment.

Co-Production of Space: Learning from Community Planning for Convoys Wharf

Louise Oswald

BSc Year 3

Reflecting on the principles and details outlined in VOICE4DEPTFORD’s Design Framework (2021), the masterplan for Section C5 was co-produced focusing on the social resilience of the local community (now and future residents) and healthy streets and spaces. The masterplan focuses on the inclusion of locals of varying ages throughout the site aimed at making it a multi-generational residential area, with programmed areas inviting users and through the integration of different housing types.

Learning from Deptford’s community planning organisation, VOICE4DEPTFORD, and understanding their wants for their local area to co-produce a section of a masterplan in aspiration of a multi-generational future.

This section of the masterplan focuses on the provision of housing and public spaces. Shown contextualised with the masterplan in Figure 1, Section C5 integrates Deptford High Street with the listed Olympia Building.

The proposal that follows is co-produced learning from VOICE4DEPTFORD’s 2021 Design Framework, a community devised proposal for the redevelopment of Convoys Wharf.

FROM VOICE4DEPTFORD

The Design Framework outlines 6 design principles, including:

(1) Supporting a socially responsible communtiy and, (2) Creating healthy streets and public spaces.

(1) Supporting a socially responsible community

This prinicple outlined the local need for afordable housing; street and housing design for communities; adaptable housing for the changing needs of through life; and community spaces.

The design I propose delivers various housing types, designated multi-generational spaces, and public open and indoor space,.

(2) Creating healthy streets and public spaces

This prioritises the integration of current provisions of open green space surrounding the site.

Section C5 integrates the neighbouring Sayers Court park into its open space, successfully connecting the nature and facilities Deptford currently utilises.

This principle also develops the concept of courtyards as outdoor living rooms, an idea I incorporate into the residential units.

Interviews with Deptford residents showed that those uninvolved with Voice4Deptford plans were unaware and dismissive of the development- saying “so long as the development doesn’t efect me”.

Communities living here are encouraged to take ownership, maintaining and enjoying their home. Examples of high space ownership by communities can be seen in developments like the Barbican, and in rural towns such as An Chill in Ireland.

(Harney, 2022)

Deptford is home to initiatives aimed at driving space ownership. Twinkle Park is a charity park that has been redesigned by the local community. Additionally, along the Thames is the Pepys Community centre, advertising its welcome to passers-by.

(Photographed 2024)

OLYMPIA SQUARE

The square connects Convoys Wharf to the High Street, and includes programs of activity for young children, teenagers, adults, parents, and grandparents.

PUBLIC PARK

The park in the north of Section C5 links Sayers Court Park to the public square, and onwards. The park has a balance trial, vegetation, and a park to encourage community stewardship and continued use.

Small, medium and larger (multi-generational units) are provided to permit residents to adjust their homes to their needs without being having to lose their community.

Deptford’s current population distribution illustrates the demand for homes adequate for young professionals. Provisions decreasing in concrentration from the open space, maintaining the quiet and secluded feel of the family units.

MULTI-GENERATIONAL HOMES

VOICE4DEPTFORD outlined the local needs for adaptable housing that would suit the local population throughout their changing lives. The homes in this unit are designed following precedence from Chobham Manor in London, servicing families with seperate but connected multi-generational homes.

OUTDOOR SPORTS HUB

Integrating the young and old population of Deptford, the sports hub was designed to incorporate outdoor exercise equipment for use by the older population with the running track.

Learning from VOICE4DEPTFORD’S Design Frameworks (1) and (2), the following strategies were defned for the achievement of a co-produced

Inclusivity will focus on the inclusion of ages. This is addressed with the design and provision of multigenerational housing.

INTEGRATION

Section C5 uncovers some of the Sayers Court ruins, integrating the site’s history. Integration with the surrounding environment is achieved with attention to building heights.

Combined with integration of active transport, sustainability will be strived towards by high quality green spaces, local facilities, and a variety of housing typesencouraging longevity of Convoy Wharfs’ residents.

Housing in this development relies on the sharing of spaces and

With recent redevelopments becoming centres of visitor interest, see Battersea, the priority for Convoys Wharf has to be the home-ly nature, and the distribution of space.

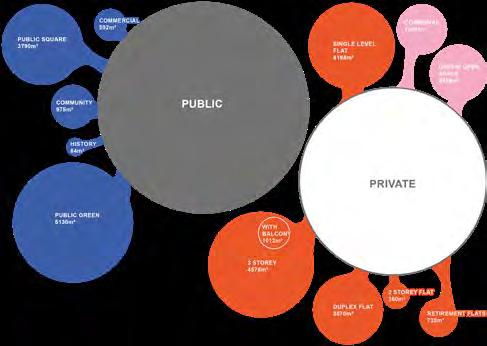

Left illustrates the distribution of space within Section C5 by m^2 using data retrieved from the CAD model. (Model used 33% increase on Lewisham Residential Standards SPD [Lewisham, 2006])

Hearing from locals has been a integral part of the actualisation of this masterplan. Firstly, visiting the site to understand the constraints and needs the location has, then in the review of community devised Design Frameworks to direct the interventions.

Through the process of reviewing and practising the VOICE4DEPTFORD’s Design Framework, I have learnt that although some urban issues are found in other locations, and therefore their interventions can be looked at as precedence, it is withstanding that locations have their nuances.

Deptford faces the systemic urban issues of housing shortages, of crime, and of inequality. However, for Deptford, they required adaptable housing, activity spaces for older residents (including designated spaces for teenagers, and afordable prices in the context of their income.

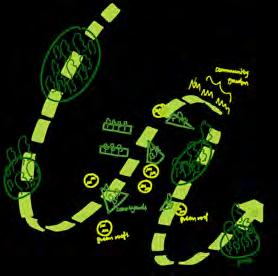

Deptford Discovery District: Communal Learning, Living and Leisure

Rebecca Koh

BSc Year 3

Deptford’s Discovery District aims to foster collaboration and interaction among residents, planners, and businesses to co-create an inclusive neighbourhood bringing residents together through opportunities for collective experiences and learning in daily activities. All aspects of this master plan are guided by the aim of creating educational opportunities in the overlooked mundane, bringing a sense of excitement in everyday lives while enhancing social capital. This project aims to present education as a solution to the paradox of balancing the site’s rich historical past, pressing community needs, and economic aspirations of the future, necessitating collaborative processes to sustainably bring a constant sense of discovery and creation to all of Deptford’s residents.

Reuniting Sloane Square: From Isolation to Connection

Daniel Hunt

BSc Year 1

‘Reuniting Sloane Square: From Isolation to Connection’ emerged from immersive, on-site analysis, which identified an underserved local community and a pseudo-public space characterised by seasonal lifelessness and car-dominated boundaries. My design responds through co-creation, informed by local movement patterns, everyday users, and precedent inspirations, and iterated through sketches and diagrams. The proposal reimagines the square with adaptive greening, sunlit gathering steps, and pedestrian-priority circulation, transforming over 13 million annual passers-by into engaged participants. This process illustrates how collaborative, human-centric design can reclaim disconnected infrastructure, turning it into a vibrant and inclusive public realm.

Sloane Square: A Green Corridor for Urban Collaboration

Dana Cheng

BSc Year 1