Olivia Heggarty

Editor-in-Chief

Emma Buckley

Editor

Anna Gordon

Editor

Lucy Hatton

Editor

Ellis Hociej

Editor

Eve Henderson

Editor

Bryan Sim Typesetter

Olivia Heggarty

Editor-in-Chief

Emma Buckley

Editor

Anna Gordon

Editor

Lucy Hatton

Editor

Ellis Hociej

Editor

Eve Henderson

Editor

Bryan Sim Typesetter

As we close on our second and final issue as the current team at The Apiary, I’m filled with gratitude, pride and the sadness that is coming from handing this magazine over. Issue 5 is another triumph and this is entirely due to the wonderful team I find myself with, and the breadth of talent that spans across the Queen’s community. As with any success, I have a world of people to thank.

Thank you first and foremost to my editors: Emma Buckley, Anna Gordon, Lucy Hatton, Ellis Hociej and Eve Henderson. You have brought intelligence, warmth and love on the hardest of days; sat for hours as we discussed line breaks and tenses; shared in the exhaustion of putting together a magazine; listened, learned, taught, laughed, cried, Gibbied; gave up your free afternoons to give something invaluable to the writers and artists around you. I am inspired by your generosity, kindness and selflessness, and working with you has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. I’m going to miss our four-hour-long meetings in First Avenue where we stare at words for so long we become delirious and can no longer work. I am entirely indebted to my typesetter, Bryan Sim, who continuously gives up his free time to weave together every element of the physical magazine you are now holding. Thank you, Bryan, for giving everything you have to make it perfect and using your own creativity to make each issue different from the one before. Thank you for answering my one hundred texts and edits at two o’clock in the morning, and for sharing my passion to make The Apiary something truly special. Thank you to the staff at First Avenue on Stranmillis for hosting our meetings every week, for your interest and your friendliness. We love you!

This year, Issue 4 was fortunate enough to be shortlisted for Best Student-Led Activity by the Queen’s Students’ Union, so I’d like to thank the Clubs and Societies at the SU for this incredible privilege. It was great for the team to experience all our hard work paying off.

I’d like to thank Michael Magee for his incredible generosity to this issue; for taking the time during an insanely busy period in his life to sit down and talk to me about his work, share his writing advice and chat to me about all other kinds of nonsense.

This interview gives Issue 5 a wonderful sparkle, and its wisdom, I’m positive, will inspire every writer it reaches. Thank you, Mick.

Thank you to Anna Gordon for transcribing the interview, and to Dara McWade who helped me to prepare it for publication. Thank you also to Dara for agreeing to take over The Apiary next year. There is no more trustworthy person around to take over this important work and to give it everything.

Thank you to David Torrans for your continued support and patience as I learned to invoice, and also for stocking our magazine in No Alibis. You are just wonderful. Thank you to Floss Morris for letting us use her beautiful art for our cover. To all of our contributors, without whom our magazine would not exist. Your work has filled this issue with love, mystery, darkness, colour and life. We are eternally grateful for you and always have your work in our heads as we go about our own lives.

Finally, dear reader, to you. Thank you for picking us up, for supporting us, for loving words and stories and weird images as much as we do. Thank you, everyone, for having me as your editor-in-chief. I have immense excitement for the next issues, for the realisation that life just doesn’t stop moving, and to quote from a wondrous poem in this issue:

Wait to begin again, like the bare page, for something to turn green.

Go and find it. Let’s begin.

Olivia Heggarty, Editor-in-Chief

August 2023

I’m wondering where to find a lens to see what else I’ve missed with the curtains drawn after reading a headline saying

Woman faces prison for possession of a poster of the Virgin Mary with a rainbow halo

so I go out and into Belfast’s welcome-home kisses from the rain on a dander down North Street keeping on a path the length of Mondays with a forecast of tea with the bag still in and I pass two women stopping in the downpour. One removes her coat and pulls its striped pattern skyward, slipping her head into a shoulder, her friend squeezing her own into the other, laughing.

Suzanne Magee

“I don’t know how yous smoke ‘at stuff every day, would turn my head to mush,” I said when Marc and Kurt started rolling again. They had already smoked two joints before I arrived at the shed in Marc’s back garden. Marc had been talking about converting it to a bar for a while now, but all he had done was add an exhausted sofa and some old garden furniture and sit his old fridge in the corner.

“My head’s mush without it mate, fucksake,” Marc said. He was still in his work gear, covered in dust and mastic.

“Takes the edge off life for me,” Kurt added, smiling the way he did when he knew he was only half joking. “It’s my escape.” He lit the end of the joint and took two draws before passing it to Marc. I laughed.

“You’re mad, mate. What do you need to escape from, ya big waster?” Kurt was one of those guys who didn’t deep anything or take stuff to heart. And he wasn’t actually a waster.

“Listen,” Marc said. “Sometimes ya just wanna sit and smoke and relax. Nothing wrong with ‘at.” He wasn’t looking at me, instead he was scrolling on his phone, holding in his coughs. Marc was the kind of person who felt the need to justify everything, as if every observation made about him was a judgement or attack. I often wondered why he got quite defensive on occasions. He never used to feel the need to explain himself, but recently it was easy to start him on a rant.

“It’s not like I’m taking days off work or anything,” he’d start, before saying how there’s worse than him and how it doesn’t harm anyone.

“Fair,” I said. I wasn’t sure what else to say. They had started smoking a lot over the lockdowns, and now this was their nightly routine as Kurt only lived round the corner. Sometimes, if I hadn’t seen them in a while, I would drive down and sit with them. We sat in silence for a few moments, all of us looking at our phones. Kurt and Marc passed the joint between themselves. Occasionally I would make eye contact with one of them.

“So stoned, bro,” they’d mumble, before going back to their phones.

“How’s life anyway, Joe?” Kurt asked, leaning far back into the sofa. “Uni going sweet?”

“Aye, it’s not bad, just a lot of reading. Proper heavy stuff sometimes. How’s

the warehouse?”

I didn’t like talking about uni with them. It always felt condescending explaining what I did, and it just made me seem more different.

“Shite but what else is there to do? Not all smart cunts like you.”

I laughed, trying not to sound like I agreed with him.

“You’re just smart in different ways.”

“True, I can ship an ounce quick enough like,” he smirked. I never really saw Kurt as a drug dealer, he usually only sold enough to get his grass for free, but he was one, nonetheless.

“Exactly, mate.”

“You out on Saturday, Joe?” Marc asked, still not looking up from his phone.

“Dunno, mate. Where yous for?” I turned to Kurt. He was fiddling with his lighter, his eyes red and squinted.

“Probably go to the match then somewhere in town after. Welcome to join, like.”

“Aye, I’ll let yous know.”

“Been a while since you’ve been out with us,” Kurt said, nodding at me.

“I know bro, it’s just boring sometimes,” I said, making sure not to sound like I was blaming anyone specifically.

“True, but what else is there to do?”

“I dunno, but I don’t really fancy sitting there while yous are all wiped out, barely talking, sweating buckets an’ all.”

I had to stop myself from wincing as I finished. I didn’t want them to think I was judging them. I didn’t care what they did on nights out, but it did get boring.

“Just get on it with us sure,” Marc half yelled, slapping the side of his chair, pretending to get hyped up.

“Been a while since I done that stuff bro, you know ‘at.”

I had stopped doing drugs when going out a few years ago. I started having panic attacks out of nowhere and I convinced myself they were heart attacks every time. Since then I stopped taking stuff. I used to use the mental health excuse.

“My head’s cooked as it is,” I’d say. The truth was that I was scared to, in case there actually was anything wrong with my heart. The smell of the grass started to

make me feel dizzy.

“I know but why, mate? You’ve done it before, and it’d save you from sitting there left out like a dick.” Marc was sitting upright now.

“Just don’t fancy it anymore,” I shrugged. “Twenty-four years old like, don’t need to be doing it every time ya go out.” I was looking at Marc, trying to twist my face into something that conveyed I didn’t care that much.

“Exactly mate, like we’re still only twenty-four for fucksake, still young like,” Marc said as his words grew faster, waving his hands slightly.

“Nah bro, it’s not for me anymore,” I said to Marc before turning to Kurt, “but I’ll give yas a shout if I’m heading on Saturday. Might meet yas for a few.” I started to get off the sofa.

“No worries bro, you heading now?” Kurt said, reaching his fist out.

“Yes bro,” I bumped my fist against his.

“Speak later, mate,” Marc said, sticking his fist out after.

As I left I heard Marc say, “Rolling another one, Kurt?”

“Uhhh, aye fuck it, ‘mon.”

Andrew Mullan

Carrie, I’m sorry about the blood in your eyes and all the billboard signs reminding you that hell is real and that you’re going there. But we can wash the blood out of your hair, burn your prom dress, throw the tiara in the creek. That old town is ashes now. It was never even there.

Carrie, turn the camera away. Reframe your life in this new moment: my open-top cadillac, the breeze on your face like a kept promise. Let the open roads hold you like the throats of father frogs who swallow their tadpoles and puke them out whole at springtime.

Carrie, there doesn’t have to be more blood ahead. We can fill the backseat with gas station flowers, sleep by the roadside and dream of burning houses. Our new life has no gymnasiums, no prayer closets. But if you change your mind. If you miss wide eyes and telekinesis, if you haven’t drunk your fill,

I’ll stand back. I’ll keep an eye out for cops. I’ll keep the car fuelled up. I’ll watch you kill.

You are not trying to change me.

You don’t mind that when you get me alone I am apple crumble all over the floor.

That in the pub I am a cat navigating parked cars and you’re the kid psspssing for a little affection from me.

You don’t want to dunk me in a formaldehyde bath.

You want to see what happens. You want me primarily on dance floors. You want me stretched out across as many continents as we can find. You’re gonna buy bedsheets with a map of the world on them.

You want to watch me flirt with other people across the room. You don’t want to punish me for this. But maybe you’ll joke about it. Press me up against a bathroom stall and hold my neck perfectly, like a sanctuaried animal.

You are writing academic articles to get my attention. You whisper: ‘do you wanna peer review me?’ and pull your shirt up slightly. You have ink from the sociology reference book on your cheek. You’re not the type to bend to what is left of my will. My will and testament were written on a hospital bed because wanting to kiss you for so long destroyed my kidneys. You want to do the inheritance tax math.

You came with no name, so I could still share you with the other girls. You came and I wanted to collect you all. I want to see if all of you have fucked up septums. I want to know everything, everything, everything. My cells are screaming ‘touch me! touch me! touch me!’ I see you across the room. I think this is it. This is it. This is an atom bomb crush. The doomsday clock moves oh so slightly because dear Christ, those teeth glow in the dark.

“These are objects,” my father told me. “It doesn’t do to become attached to them.”

The tablecloth was gifted to my mother when the Lancaster widow moved to town.

“This is how it goes,” she said, when I asked what good did it do to leave the great house empty. “Father will take an extra shift. We’ll get by.”

By home time of the first school day each January, the table would be bare once more. Starched and crisply folded, the tablecloth would be packed away among the Christmas things, in its own separate box. Not to appear until next St Stephen’s Day.

“Once all the mess is cleared.”

Over the rattle of the bus, I asked Father about bringing it to the hospital. Maybe the smell of the fabric could stir something, the sweetness of it, or the delicate feel in her hands.

“They’d not allow it, son,” was all he said. “Show me your multiplication lesson.”

Father did not answer questions about who the collector was, or what it meant for something to go into a collection. Go where?

“Better that it was appreciated some place,” he said. “She’d not want us tripping over her things.”

The photographer offered his sincere condolences. His eyes never lifted from the open box in Father’s hands. With his eyes, he regarded the same swirling flowers I’d copied into my sketchbook a thousand times or more.

He saw something else entirely.

Shane Thornton

John Moriarty

By the sea, I fall in love from across the room with a former soldier who I’ve never met and I tell my friends I have to have him so I do and become as charming as possible until he is kissing me on my friend’s couch at 5am and touching my thighs while everyone listens to Oasis’s entire catalog. And we will never do this again. We will never speak again. But for a few hours I imagine cooking him dinner every night until we die.

Alanna Offield

I would like to feed you, which may never happen. I would like to soften butter and fold in flour, to split the flesh of a loaf and pass half to you.

I would like to lower my guard and eat with you as though I do not believe I am prey, as though you will never betray me.

I would like to feed you until your belly is swollen, until you cannot stomach any more of me.

We packed him in the back of my da’s van like Hannibal ready for his court hearing.

Stationed by his side like a prison guard, I held his wheelchair with a tight-white grip for fear he’d roll away, careering onto the streets of Belfast.

Grandpa couldn’t believe it had come to this; crammed into a van like cattle for slaughter. But we just wanted him home for Christmas.

I could have sworn I saw you yesterday, in a past much too future to host: my girl. Leaned over a barstool, balancing a conversation between two floating feet, the skin of your hips a cool stone skimming the ocean amongst such washed out denim. Swinging back, on my want, then forth, on your need.

I couldn’t help but stare at the stranger who had stolen something she never took, something she never once knew to possess. Her hair a little more like mine now, but short and separated from your sisters. Cut with some sword, you’d wanted a turning point; some Presbyterian end.

Her parents didn’t hold her just the same didn’t press the softness out of her, unpreserved unlike your immortalised petals bronzed between pages. They peppered their lawn in her wildflower seeds. Her girlhood could blossom from the soil under fingernails. The garden sweat of June beaded onto each bud of her rosary.

In Summer, you cut the grass with every other neighbourhood son. Their mothers asked when they would see you kneel. In Winter, they taught her how to build a fire, her marmalade-glow face sunned enough to hold February. Shut up inside, kept from some lifetimes of sand, your body refused to replenish its deficiencies.

I remember how I couldn’t look at you then. That atrium pooling with blood, filling and emptying. That sound of sweet rainfall. That Autumn smell.

Confined, all I could do was take every yearbook, every hair: enshrine you to mine once again. Pray to God, for once, those rumours braided themselves to my truth.

Your guilt had fermented into synthetic peaches. The sweetness didn’t suit you, my girl of mineral. Under bleaches the culprit had killed my motive. He had never been thirteen the way that we had; pillowed in each other. His urge, never anonymous. He had never used sleep just to lift your veil of shimmer.

At the funeral they unveiled half a portrait. It weighed more than I could ever think.

Your face splintered in the drawings we did as girls, I saw you: in crayon, an angel, and me, beside you, the same wax coating blue wings, still suspended and flailing while you melted into leave.

After you fell, I kissed him too, wondering if some trace of you would lie in the saliva left over. If I could infect myself with your secret sadness again. Carry that shrouded ritual covered in dust: our love hidden on the highest shelf, the fibres hanging still from collapsed beams.

Only my arms and I remain: the empty frame of something that was never mine. Only the border. I tried to be your quadrilateral, holding my angle for some painting you could never supply. Your beauty blunt, grace buried, but desire seemed only stronger until its newborn flame hurtled to ash. The air that chose to die.

My frame hosts the tableau of a life I mistook, undeveloped, to be mine: you, or, the girl from the bar, meets another, who in blur looks a little like me.

But, uncovered and left for her living shows more wilderness in each iris and a mouthful of crowded, but better, teeth.

In Spring they are born unto each other. Over ornaments and snowfall, your alternate brings mine home, in festivity to some icing sugar parents with edible walls. They do not bond over repentance. Pain is fenced out by white chocolate pretzel. Their original sin is beautiful, the way it is supposed to be.

There is no question of intent. They intend to go together, while you refuse to resurrect.

My hands much too weak to dig for your bones, the dirt separates our bodies. The realm of decomposition yours, I live again with the worms; but at night we collapse under just the same tree.

When the inky black Braid River depths swirl and circulate like liquid treble clefs, let our placid boy sink his teeth into your crusty matchstick finger, you boot him and I weep silent and sullen.

I dream I’m in a thrift shop, sifting my way through rails of pre-loved clothes. I am searching for a dress to match a necklace I once owned.

There are five large rooms, walls all painted black and trimmed with reams of rainbow-coloured bunting.

I stumble over railway lines, a Lego-green train chuffs to a halt beside me. It’s for display purposes only, a woman says.

I stop and watch it leave, and then return, leave, and then return, leave, and then return.

Stacey Denvir

In this mind, it began when I set my own hair on fire. Or ended. Beginning or ending it was the something. If it was the everything that had led to this or the nothing that followed they will tell me I don’t know. But the rounded edges of the withered photographs had caught it. Looking past the subjects my blank absorption of their edges had usurped any cognitive workings. With burnt tea splodges as if dyed for a school project, the curled brown fringes and their cream borders were beyond vision. They held me hostage. These dirty, yellowing edges were not the work of any schoolchild. It was just that they were old. They told me that I was old. They let me into this secret with greater authority than the pension letters beside the kettle or even the child face - white, unwashed, and unweathered - that featured in each one.

She had taken me to a living room, with carpet I knew and faces I didn’t. They were divvying up. I was handed an envelope and an album off the bookcase. I was tilting closer now, gently trying not to disturb the memories within. Asking them not to go. How funny it is that a life or whatever remnants are left inevitably end up on bookcases. Dusty, leatherbound albums, fingered glass frames, or motheaten diaries, holding only what we will possibly allow others to know. We should choose our bookcases as carefully as we choose our coffins. Mahogany or cherry? In a moment of self- awareness - I realised that there was no bookcase for me. And I hadn’t the strength to choose one now. Where would I end up? Under the spare bed perhaps or in the bottom of a wardrobe.

My mother had lots of bookcases, with lots of frames, and lots of albums, but no diaries. It made sense, she was a person with no words. She once told me that she thought in pictures. My mother said that when shopping for messages she would picture the cupboards, visualise what was missing and buy from the memory of her mind’s own picture-book list. I was smallish and took this to mean that she could not read. A mother who could not read was big news. I told as many at school as I could, thinking that this revelation would mean that I was a genius. A reading

daughter of a mother who could not. This was all ruined when thon hallion in the class above stood behind my mother in the butcher’s while she disputed her receipt:

“But you can’t read!”

She gave me no words only the promised image of a feverish red bruise on my thigh. We shared volumes of these picture-book bruises. With each, I was a genius no longer.

I was moving closer to the borders again. Each photograph was laid out on the glass tabletop like evidence for the crime I was about to commit. I think I knew faraway somewhere, in the same faraway as her name, that the candle was there. A leftover Christmas gift from the one with the nose. Mandarin and cinnamon like hot port peppered with cloves. That could be why I eased so close unaware. You know I would laugh at that now if I could pull my mouth into any shape of joy. My hair did not smell like hot port though. It smelled like cheap burnt wool. Like a boy kicking a football into the fire and knocking the burning coals onto the crimson rug; red, red skittles scattered across a red, red alley. Now tell me that I am doting.

But I was in the edges and did not see my hair crisp up and the flames twirl about my head. Fire Bird ballerinas leaping about a sagging stage. Faraway someone was on fire. Only when my ears started to singe, and my glasses’ chain began to weld itself between the flabby wrinkles of my neck did I begin to nearly realise. Stirring now, I felt the on-fire-ness of my hair and cardigan. The cardigan came off onto the table and the last straws of my hair went into the nothingness of burned things. Half a can of hairspray a day will do that. The edges of the photographs began to curl further now with the fire that consumed them. Furling up into themselves rows of bodies tensing in pain. Fire spreading from border to border, like plague between villages, the life my mother chose to curate was eaten. She’d call me a witch.

I was absorbed more in the licking of the flames now. Detached from the scene I watched it like a half-interesting documentary. Plants or insects no doubt. No drama, no plot, no dialogue - just the chosen facts of a life. Baby steps, First Holy Communion, last day of school. The fire snuffed out. Strong enough to eat away my life but not half decent enough to take the rest with it. I caught my reflection then, in the glass of the microwave, and choked at the sight of a withered, balding baby pigeon, ugly and singed. The smithereens of my egg now in smoked ashes on the frosted glass. And I cried then. Not for the burnt feathers of my hair, not for the curled edges nor the bleeding sepia borders, but because now there was no need for a bookcase. I wept for the life that would not gather dust on a shelf or be stuffed in a drawer under the spare bed, or even dumped in the bottom of the wardrobe.

Molly McKillop

She is sowing the garden with fresh linens long before He moves to hang the sun. Her scarlet fingers throbbing in exaltation of the good work, she unfolds a hymn to worship the morning; a Hallelujah for the budding clouds, All the time to the feathered choir. This is the day the Lord has made, so she takes what joy she can, before stepping back inside and shutting the door to keep the air from leaking out. Her knees blooming like overripe plums, she folds herself down, pressing a hand over her swaying breasts and begins to sweep last night’s chewed up fingernails from the floor.

Her days are just preordained verses. She does not wonder how she got here, and no one ever asks. She prayed to be a good girl and she was and now, she wrenches her stiffened mouth open to re-polish the tarnished smile.

She does not cry. She does not tear the curtains or flip the dining table. She does not claw through the sky to ask God why He let her slip like fruit from the hands of a careless child. Instead, she turns off the lights to her bruised life, chokes and gags on the pulp as she ascends the stairs.

Once in her room, she will strip down bare to her aging sins, tie back the loose strands of hair and lay her head on the pillow. With her hips pressed under His weight, she will close her eyes and recite a requiem into the dark;

amen amen amen amen amenamenamenamenamenamen with faith that this time, she might finally fall asleep.

Anesu Mtowa

1.

Back home the meadow, not the house it’s blue-skied September and there are five cows. They don’t remember you. You’ve been twenty for twenty years. It’s bruised pink by the time your mother realises you are not coming home.

2.

The flesh tastes of what you assume pig tastes like. Burnt by the fire, burning your stomach lining. Your organs are falling in rivulets down your leg by now, freebleeding into the pasteurised grass. You like the smell.

3.

It’s all over the car. Your face is smeared like red lipstick and the countryside altitude is exploding heads with bits of brain all over the dashboard. The whole drive home, not your home, he’s saying, “It’ll wash right out.”

Anna Gordon

I make a spectacle of my man in the light, by the water, watch him rest his hands just above the surface — restless reflection yellow on his palms and the blue below. The lake

presses itself to the shore in layers of silt: green-brown, soil that is only ever wet. Only ever patient with footfalls, with the two of us, silent. And the water stalking our edges and the forest of spruce monoculture circling in the wind. I make a spectacle

watching my man in the light by the water, his back turned to me and sloping down to the surface — restless reflections menacing his dripping face.

Sophia,

Do you remember the cross steeple you could see in the distance across the houses from my back garden? It always looked so far away, but it was only a five-minute walk from my house. I always found it weird that it was never part of the actual church building. It didn’t sit on the roof, instead it was built behind it, separate from it, towering over it. Did you ever notice that?

It feels strange writing a physical letter in this day and age, but I couldn’t find you on any social media. I hope you don’t find it weird, me writing you. Mam is dead. I thought you should know.

I’m not entirely sure what was wrong with her, other than the obvious. When I asked her, she would get angry, like she used to. “LORN! Stap fuckin goin on to me would ya! Fak aff,” she would shout. Remember how we always used to laugh at how she said my name? “Laugh at me again, go ahead,” she’d nod at us. I always felt like with you around she was never serious about that, but I wonder if you weren’t there what would’ve happened. Probably what usually happened. But how could the woman who named me say it so wrong? You’re lucky she didn’t name you, although she may as well have. You weren’t even her child, yet you probably did more work out in that garden than anyone.

I used to hate that garden. When I would visit Mam while she was sick, I used to look out the kitchen window and see it, dead. The rose beds she used to make us fertilise were empty, even the weeds, with nothing to feed off, had died. The evergreen conifers at the back of the patio, the ones that used to separate the garden from the house behind, were overgrown too. One even died. The house behind’s washing machine leaked, and the chemicals spilled down their garden into ours. So, for a while in the corner, sat a dead conifer next to the overgrown ones.

It would make me giddy, seeing it like that when I visited, but you know what

Mam was like. She could get sympathy from the devil. “Lo’d the state of that back garden,” she’d say, from her bedroom, which as I’m sure you’ll remember, was at the front of the house upstairs. “Awk sure remember it used to look class?” she would ask.

It did look class to be fair, during the summers, when we had finished it. I can see it so clearly, the raised rose beds on each side of the steps towards the top patio assembled with pink and yellow buds, the pale sandstone slabs of the top patio, the verbenas and begonias around it. The low red pillared wall that enclosed the patio. I can picture the wall the most, the deep shade of red, almost as deep as the shade of the mark Mam left on my stomach after I dropped one of her clay pots.

You never really saw that side to her, did you? She was defensive over you. Even when her friend Patsy would come round. I remember Patsy would wind you up. “Sure, where did you even come from? Nobody knows. Agatha just showed up with you one day fer fuck sake,” she’d croak, as if her grown womanhood was in competition for Mam’s attention with you. “Goan and leave that poor child alone will ya Patsy!” Mam would yell.

Patsy’s still alive. She came to Mam’s funeral. She doesn’t seem too well herself, which might explain her coming up to me and saying, “Your ma always thought you and Sophia were good girls, so she did.” I almost told her to fuck off.

The garden’s looking better now though. I ripped the dead conifer out. There’s an awkward gap there now, which I’ll have to fill in, but I’m not sure with what. Anything else would look stupid next to a row of them, but I don’t think I’ll plant a new sapling. I jet washed the sandstone slabs, even though they’ll inevitably get dirty again during these winter months. But for now, they’re clean, and on brisk sunny mornings I stand on the patio and look over the houses to that cross steeple,

which is separate from the church, and I no longer wonder why they designed it that way. I still haven’t repainted the wall, I’m not sure what colour to do. I might just knock it down.

I hope you get back to me, let me know if you plan on visiting the grave. Last time I was down, the soil looked pale and grey. Do you think you can plant flowers in winter? I think you can. Do you? Yes, you might get cold, but I’m sure if you move around a little you can warm yourself up. Besides, I don’t think we were meant to stand still anyways.

Your sister,

Andrew Mullan

I sit with this grief, it lines my lungs like lead, grips my hand like a friend on the first day of school. Terrifiedbecause you sense without knowing, you’ll be defined by what goes on inside those walls; by those who grip your hands through it all.

I sit with this grief, it warps my waist like bone, fixates me like an unknown when in reach of content. Sabotagefinding problems in the future because you will never save enough for idyll’s rent; borrowed time means you already owe debt.

I sit with this grief, it snaps my shins like cane, sits in my mouth with your name and smells of onion. Funnythough I bit the thing raw it’s those I breathe on I somehow reduce to tears; life is unfair but that has always been clear.

I sit with this grief and it tells time like a sun dial, petrifies me like a reptile that slowly circumscribes me as I sleep. I wake up each morning screaming as I greet my Grief, the panic never claims less hold. I sit with my Grief and only one of us will wither, as we rest side by side and grow old.

after Mary Oliver

Cherry blossoms in all their sugaring of rain, their lives sudden against the world— like truth: ‘at once’ being at once unfurled. Is this what the dead would trade for? brokering cold bone for a fresh eye, for this new eye of traffic light, his cardinal pop-stardom, his one word like a cry postpartum. Winter past I only wanted to die as these things, to stand like a mannequin without mourning, without need to declare that my one, stupid life ended. I stare to the light, for season, for sense to convene in the body, and wait to begin again, like the bare page, for something to turn green.

Staring at stone skies since September, I’ve lost sight of the blinding light of a winter sun, forcing itself through clouds of a paler hue, less dusty and more like snow. I miss the norsk winter, pining for pine trees dusted with white, craving the crunch of frozen leaves on a frozen ground, I miss the cold icing my fingers, my veins until pain hits joints, chilblains on feet under Christmas socks from Mormor, need more to keep you warm.

Nothing hits that spot, no amount of cocoa or fire or blankets or jumpers or the cat crawling in beside me.

Jeg savner deg. (I miss you).

I still get that feeling of something running deep, but not cold, through veins. It’s the damp of the rain, wet on wet toes as I land in a puddle again, the umbrella that mama bought me last syttende mai shaking water in my face in a breeze, trees rocking, more rain falling. The damp stays with me, constant rotting from the inside, like a disused wall in a disused house. I can almost smell it. Jeg håper du forsatt har plass til meg. (I hope you still have room for me).

Caoimhe Bassett

In the sun I watch the estuary of veins on your forearm. I trace them to your palms, a delta for the river of you.

And me, I make myself a mouth — receptive. You put your fingertips on my tongue once — filled me with freshwater, with running. I accepted your restlessness, made it my own.

These days I can’t hold a thought long enough to know it and since I got my fillings my jaw no longer feels like mine alone. I sometimes feel like a stranger in this body, watch my sweat mineralise at the surface of me.

Here you turn your eyes to the light, pinch the one side of your face against the glare and shudder like the grasses, wild, that grow on the canal’s edge.

You get up to leave, as always, onwards, unsettle sediment, dream of the new. I, floodplain, memorise your shifting. I, bank, recede to know you.

It was the widening of your eyes and the turning of your head when you saw me recording you drunkenly scarf down that pizza.

The embarrassment in your smile and the thick tomato paste that dripped on your knock-off Fontaines D.C. t-shirt were captured in pixels I wish I could leave on an old computer monitor for years on end, burning it into the screen, giving it the immortality

I wish this poem could.

Brian Kerr

for Ryan — sort of

You ask me for a praise poem but I’ve no words to know you so I turn to the palms of my hands and remember your cheeks there, remember you asleep beside me and I beside you once, younger, trusting the world. I’d message you for midnight walks down the hill to the shop where I’d buy my fill of sugar to make it through the night.

We drove your mother’s car into the desert once and on the last stretch before camp we had to slow to a crawl to save the rims from that martian road. Time slowed. You found parts of yourself that weekend in strange couples’ tents. I found a maze made of black fabric with speakers at the middle beaming the audio from the Apollo missions. I lay down without you — watched the sky, clearer then than I’ve ever seen it.

Cullan Maclear

“It wasn’t about being published, writing isn’t about that. It’s actually just about the work. And it’s about actually doing the work.”

Early this year, our Editor-in-Chief, Olivia Heggarty, sat down with Michael Magee to discuss the fiction writing process, submission advice and his debut novel: Close to Home.

OH: When did you start writing properly and what got you into it?

MM: I’ve been doing it since I was a kid, you know. One of my earliest memories of doing it was, my ma’s best mate, my Auntie Mary. She lived across the street from us and she had a typewriter in her living room and she showed me how to type my name on it. I remember seeing the letters appearing on the page and being obsessed with it. So, I used to call over to her house, I was what, three, four years old, and I’d be like: “Can I write stories on your typewriter?” and she’d bring me in and sit me down with a cup of tea. And I’d sit and type gibberish, you know. For ages. I started reading maybe when I was like thirteen, fourteen. I was reading all the stuff that you read when you’re that age, like swords and shields, all that magic. Elves and orcs. So, I wanted to write that. I thought that was what I wanted to do when I was that age. And then when I got to

like sixteen, seventeen, you mature and start reading other stuff. It’s always been connected with reading. You read stuff and you think you want to some way imitate it or something.

OH: I think that’s really common because when I was in primary school, I was obsessed with the Harry Potter books, and when I started writing I wrote about a wizard school.

MM: Yeah, yeah!

OH: Plagiarism just isn’t a thing when you’re younger.

MM: My thing was Lord of the Rings! Just plagiarising it, you know? But I think you’re just trying to find your way in, you know, and the only way you can do that is through stories you already know. I remember turning sixteen, seventeen and reading Hemingway as part of my GCSE: A Farewell to Arms, and I remember reading that and I couldn’t believe that this was something that you could do. And then that really opened my eyes in all sorts of ways. And then I got to Liverpool and went to university, and when I went to university, I didn’t really know what I was doing, ‘cause no one in my family had been to university and no one around me had ever been. So, when I was applying, I applied for English ‘cause that’s what I wanted to do and then when I got there, I realised there was a module on creative writing you could do. And I was like, fucking

yes, get me in there. And that was it, you know?

I ended up dropping English in second year and just did a straight Creative Writing degree. And it was perfect for me. ‘Cause I loved literature, like, and I loved, you know, criticism and stuff, but I just wanted to write. Was a bit of a gamble, ‘cause, you haven’t really got anything to show by the end of it except that you can write wee stories. It’s not good for applying for jobs or anything. But the choice was either to keep English, or I had to do poetry or short stories, and I wanted to do both. So, the only way to do that was to drop it. And then it just went from there, you know, just sort of, the freedom to read was just important for that as well. I think the one thing English is good for is, it gives you the critical capacity that is useful for writing in a way. But also, like, you only really learn how to write through writing, I think.

OH: So you wrote a lot of short stories at uni?

MM: As well as being an absolute hallion. We ran a magazine over there like you did; it was a university magazine that was sort of handed down, called In The Red, and being involved in that world was just class, it was just amazing. I just loved being around people who were making stuff. I just never stopped really, you know. It was weird cause I had a very clear idea of what I wanted to do for a very long

time, and there was never any backup plan. Just went for it.

OH: What’s your favourite part of writing a short story?

MM: I think the two parts – it’s probably the whole process of it actually, even though they’re both terrible in all sorts of ways starting it, and getting the first draft. When you have a first draft of a story that’s a beautiful moment. And then there’s the editorial process of actually finding what the story is and going over it, like, it took me a long time to embrace the editorial process. I sort of always assumed that you bang out a story and then that’s it. But actually, work is the drafts.

OH: I think editing is much more fun in many ways. You can look at and analyse your own work and it’s fascinating.

MM: That’s it! You’re trying to find the story or the poem or whatever it is you’re doing, I think, and I think that’s the excitement of it, finding it as you’re going along. The thing with short stories is they’re so fucking hard. It can be maddening, you know! Like, there are stories that I have that I’ve been working on for years that haven’t seen the light of day. You just wanna tear your hair out.

OH: And reading them, some of them seem so easy. It seems like it should be simple to just create a wee scenario and write it down.

MM: I think that’s what makes a good story. Whenever it looks easy. It’s neat. And you’re just like, fuck sake. I think there’s pleasure to be gained in all sorts of ways when it comes to writing. But so much of it is uncomfortable and frustrating. So, you get a big injection of endorphins whenever it’s going well, and that’s kinda what you’re looking for all the time, isn’t it? When you realise that something works and you’re like… fuck! My mood is so connected with my writing, do you know what I mean? And I never realised that until I lived with someone and they were like, you’re a dickhead whenever you’re not writing well. You’re like, “Okayyy! Have to knock that in the head!”

OH: Do you write poems as well?

MM: No. I used to! So, when I was an undergrad, I was much more poetry inclined, I was fucking all up in it. Loved it. I was reading exclusively poetry for most of undergrad and I think that really helped me in a way to understand how you make images, and also brevity.

OH: Knowing what to include and what to exclude.

MM: Aye, that’s really important for writing stories particularly, like. And then I went to Queen’s and had been enrolled in the Poetry MA and it was Medbh McGuckian who was teaching

it, and our good friend Stephen Sexton was there in the class, this was like ten years ago, and by the time that class was over I suddenly realised that I wasn’t cut out for the poetry business!

OH: What was it about it that you didn’t like?

MM: It was hard to put a finger on it. I think being surrounded by people who were really good at it, and also, I think it might’ve been two workshops and I remember just, it was almost like a bodily thing, you know, like a discomfort, this isn’t what I’m meant to be doing, and I remember being really, really impressed by the writers Emma Must was in that class as well and Nathaniel McCauley and Matt Shelton, all really good writers. It might’ve come from a place of inadequacy as much as anything, you know? It was like “Oh! These ones are really good!” I don’t know why I fucking went for poetry for that long, I think it was almost a formative kind of experience, of just learning something else.

OH: And then did you go into the Creative Writing MA?

MM: And then I changed and went and did fiction, aye. I think, like, when you’re writing, you go through different phases. You move back and forth, I think. I’ve never went back to poetry, though. I fucking never will now, but!

OH: They ruined it for you.

MM: Yeah, yeah, Stephen Sexton ruined my poetry career, actually(!)

OH: Have you learned any really good writing tips? Something you know now that you use all the time, but you wish you knew earlier?

MM: When I was young, and it was actually really helpful, I used to read a lot of Paris Review interviews with writers. I thought they were a goldmine. Understanding their creative process and trying to learn from what they said about writing. Whenever I was doing my Masters, my lecturer at the time was Ian Sansom, and he said to me it took him ten years to get his deal or the first kind of break for himself. All through my twenties I was really preoccupied with the idea of getting published at the cost of everything else. I was so hungry and so urgent and impatient, everything I wrote, I just threw it out. Writing and throwing it out, to publishers, to magazines. I was being disappointed all the time and I couldn’t really figure out why. And I did write a lot, like I was writing a lot of stuff. And then it dawned on me, pretty late actually, when I was in my mid to late twenties that it wasn’t about being published, writing isn’t about that. It’s actually just about the work. And it’s about actually doing the work. And whenever I reconfigured my brain that way — and that was after a lot

of rejection, a lot of big knock-backs — I realised that I needed to change how I was going about this. ‘Cause publication will come. You just have to think, “Put it the fuck out of your head”, in a way. And write like fuck. Really learn it. Understand what it is that you’re trying to do.

OH: It’s hard to rewire your brain in that way.

MM: It really is, I think the only way I was able to do it was because I’d had rejections and big knocks. I don’t think I would’ve done it otherwise. I think that’s a thing you sorta see sometimes: a writer really talented, has a knack will get published before they’re ready to be published, and the work that’s published isn’t the best thing that they’ve written or could write. It happens all the time. Publishing’s wired that way. It’s wired to look for the next young hot thing.

OH: When you start getting published, even in small magazines, you start to equate your good work with the work that’s getting published.

MM: That’s it! Yeah!

OH: And everything else is terrible.

MM: And if your self-esteem’s pent up with publication, you’re fucked. You really are. And time is so important. I’ve seen so many friends of mine where it’s just happened a bit too soon

for them. Other people are grand, you know, it happens early and it’s great. Our friend Sally Rooney. Geniuses. And that happens. That was the biggest lesson I learned. Just trying to get over that hunger and think about the work.

OH: How do you incorporate feedback into your work?

MM: I was teaching on the MA for a semester, and my mantra was that we’re gonna be editors now. And we’re gonna edit each other’s work and our own work. If you learn how to edit your work properly, you’re in. Particularly for fiction but it’s probably the same for poems actually. With poetry there’s a really important communal aspect to it, what’s brilliant about poems is that they’re disposable. You can write loads of the fuckers and show them to people, talk about it, and they change, almost like sponges. All my mates are poets. I was drawn them because the way they go about their work is so different from the way a fiction writer does. You can see how they all influence each other. How they’re drawing from each other’s work. How they’re working off their workshop leader. The thing people don’t talk about enough I don’t think, is how the person running the workshop is inspired or influenced by the people they’re teaching.

OH: So how do you know when to stop editing your stories?

MM: I think you sorta just get to the point where there’s nothing left you can do with it. When it gets to that point, and that’s after a lot of work. All avenues need to be exhausted. You have to try and use as many options as you can. Alice Munro talks about how whenever she’s writing a story, she’ll write it from every person’s perspective. She’ll change perspective, change the tense, trying it from every angle until you find the actual story in the story. You have to exhaust all avenues. And then you’ll know.

OH: Not easy work.

MM: Not easy work, no! But that’s the work! And I think that can be a wee bit of a reality check for people, when you actually have to do a lot to get it to the point of being published. And then you just let it go. And by that stage, either the story stands, or it doesn’t.

OH: Do you have a favourite short story and a favourite novel?

MM: The novel that I sort of – I’m such a dickhead the novel I try and make everybody read is Anna Karenina.

OH: No. It’s like Ulysses to me, I just can’t bring myself to it.

MM: No! It’s not that. It’s really readable. You horse through it. 800 pages but in terms of whatever a novel is and what it can do, Tolstoy does it so well. He’s the example of

contemporary realism. He doesn’t get credited for that at all but he shows how much capacity a novel has, what it can do in that space. That’s one I always recommend. Or buy people. No one ever fucking reads it though! But when they do, you get a good response, like! When I worked in Waterstones, every time I used to see someone buy it, I used to get really excited. I’d be like, “You’ve no idea what you’re about to get into.” It sorta consumed me. I think I took about a month, three weeks to read it, and was just completely fucking consumed by it. I’ve only ever read it once! But it’s always at the front of my mind whenever I’m writing.

For short stories, it’s weird ‘cause if anyone ever asks me about books that are really important I always go back to short story collections. Particularly Alice Munro. The first book of Alice Munro’s I read, it probably isn’t her best collection, but because it was the first one it was really good for me – it was called Runaway (2004). It’s a series of interlinked stories that sort of follow the same narrator, another collection by Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son (1992) is also the same kind of thing actually.

OH: The title’s very interesting.

MM: Fucking cracker, like. It’s a brilliant short story collection. If there’s an individual story that’s really important to me, there’s one by Hemingway called Soldier’s Home (1925).

OH: I knew you were going to come

back to Hemingway.

MM: Yeah. It’s ‘cause he was the first fucking literary figure. I’ll still read bits of him. He’s only ever done, maybe one or two good novels really, but his stories are really good. They’re really good technically. I think for anybody writing fiction or short stories in particular, Hemingway’s really worth looking at. Hills like White Elephants (1927) and all them, they’re the sort of stories you get made to read on MA courses. Soldier’s Home is really important because that was the first short story I ever read. It’s about a man returning home to America after having been in the First World War, and being really affected by it, but no one around him kind of understanding what it was that he’d just been through, so he’s carrying all this trauma. It’s like nine pages. I didn’t know you could do this. I didn’t know what a short story was. It was eyeopening to me, to see what you could do in the space of nine pages.

OH: How long was Close to Home actually in the works for?

MM: A long time, yeah.

OH: I can’t even imagine how long writing a novel would be. How do you work and write a novel and do everything else?

MM: Well, I was lucky because I did my MA back in 2011. And did my PhD in 2016. I’m showing my age now. So,

there was a bit of a gap. It was the PhD that sort of afforded me time to be able to do it. So, I got a funded PhD, when you get one of those you’re set. I mean, you’re not making millions but there’s money you can live off, and you can pay your own rent and you don’t have to work. So, I started Close To Home in November, December 2016. At the time I was kind of in a rut and had come to a dead end in the things I was writing about and I think there was a general reluctance on my part to go too far into the things I wanted to explore. I knew that I wanted to write something that was set in the place where I’m from that detailed the lives of the people I knew but I just didn’t know how to do it. I was struggling with it a lot. Everything I wrote was a bit shite, and fake, and kind of just not hitting the mark.

A friend of mine, Tom Morris, the editor of The Stinging Fly who published my stories, suggested I write a letter. He came up to Belfast one night and we sat up late drinking and telling each other about our lives, when he told me to envisage someone in my mind who’d I’d want to tell my life story to. He said to start at any point in your life and just go from there, writing a letter to this person. And so, I sat down and wrote “Dear Tom…” and then just kept writing. By that time I think I’d written three novels, and spent most of my twenties trying to get them published and just failing. Doing that sort of made me reconfigure my brain and forget that I was writing a novel. The thing being

that no one would ever read this piece of writing. I was kinda tricking myself. Put myself into a headspace where I wasn’t thinking about being published, I wasn’t thinking about writing a novel, I was just writing something that was personal to me. I think in the space of three months I had the draft of a novel.

OH: Wow!

MM: Like sixty, seventy thousand words. Which is kinda the best way to do it. Or at least the best way I think is for me. You fucking bang out that first draft, do not think about what you’re doing, do not go back. Because you’ll spend four years on one chapter. So, you get it down quickly. Smash it out. And then the work starts. So, by the end of my first year of the PhD I had the draft of the novel and was sort of moving between - the letter was obviously very confessional and very personal. It was detailed in aspects of my life that were better left unsaid. But there was a time when I was entertaining the idea of writing a memoir, so it was gonna be straight non-fiction. So, part of the process of writing was trying to figure out if it was fiction or non-fiction. Then whenever I realised it was fiction, it allowed me to do whatever I wanted. And that was the moment where I was like, “Okay.” But it took, like, about five, six years, all in.

OH: Good on you, for keeping going. It’s not for the weak.

MM: It’s the way it is. Genuinely that’s it, though. I think there are people who could bang out novels every two years but it’s not me. There were a lot of drafts, a lot of re-writing, what I was saying earlier about trying every avenue. I had to make sure I tried every variation of every paragraph just to get it to work, you know? Takes a long time.

OH: Do you find Northern Ireland influences your work a lot?

MM: Aye, it’s set in west Belfast where I’m from but it moves about. Goes into town a few times. He’ll come over to South Belfast and rub shoulders with the bougie people, but place is really important. I think about place as something very small. Your area, your street, the road you grow up in. And that’s what you’re writing about. Place structures who people are as much as class or gender or race does. The place that you’re from is your neighbourhood, the place where you’re socialised, where your value system is created. People from different places have very different value systems. If you’re setting a novel in west Belfast, it’s imbued with history, particularly the history of the Troubles, the history of violence, the history of trauma. All these things come into play when you’re thinking about who you’re writing about and what world they’re in. So, all that’s overhanging the story. Class is really important for that. You felt a degree of responsibility towards articulating that

experience as accurately as you can but you’re also doing that within the space of a novel so there’s other things you have to think about. Drama. ‘Cause that’s what a novel is! It’s drama! And its effect! You’re thinking about it in aesthetic terms as well.

OH: Did you find your influence for your male characters in the men you grew up around?

It’s a very historically rich environment that we live in, this city there’s a lot of things that haven’t been articulated, a lot of experiences. I think there’s space for them.

OH: How does it feel to have it actually finished? Are you excited, or are you terrified, or just relieved?

MM: It’s weird because, see what happens - and this is something they really don’t tell you - is that you never feel like you’re finished when you’re working on a novel, you know? Even after I got the book deal, so, your book sells, but there’s still work to do sometimes, you know, so the editor will do a bit of work on it. There wasn’t major work to do on it, but I kept finding things to do. It takes up so much of your life, it’s the thing you get up for in the morning, you get up every morning to work on this or every day you sit down and you work for 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10 hours, you know? So, when it comes to letting it go it’s almost like, I don’t wanna let it go. You’re constantly trying to improve it. And you’re constantly trying to find things that need changed or made better. It got to a point where my editor had to take it off me ‘cause I didn’t think it was finished. And then it took me a long time to get over that. It’s not even

MM: Aye, like, there’s a lot of that. But also, my own experience being a man and growing up in the place that I did and what it means to have these sorts of values or ideas of self. And a relationship to violence that I didn’t realise was different from everybody else who weren’t from where I’m from. From a very young age, I was exposed to violence in all sorts of ways, in the domestic space and in the communal space, in the street and in the neighbourhood. The book is about a young man who assaults this guy at a house party, and it opens with that, the punch. And then the rest of the book is him sort of trying to work out why he did what he did and he’s confronted with this in himself, this existential question. But it also does something for the reader whenever you open the book and the first act is this violent act, and the reader might make presumptions about who this person is and then I guess the rest of the story is moving toward subverting those expectations or those presumptions. It’s also then about the group around him. His friends and his family and how they’re all affected by these circumstances that they find themselves in. And that thirty-year conflict, how it hangs over their lives.

that it’s done, it’s just, it’s out of my hands, now. It’s gone. You’re waiting on it being published and it’s exciting and scary and, it’s not even the people reading it that makes you nervous. It’s everything that goes around it. Doing Q&As and all that shite.

OH: Oh my goodness, yeah. I’m sure you’re sick to death of talking about it sometimes, are you?

MM: I was actually anxious because I hadn’t read the book since October last year, maybe. So, I was like, what’s in it? You’ve got all these different incarnations and different drafts of the book in your head ‘cause you’ve been working on it for so long, that you’re almost second guessing yourself over what the fuck it is.

OH: You’ll be talking about the first draft and everyone will be like: “What are you talking about? That’s not in the book!”

MM: It’s a completely different book! It’s exciting, aye, and scary. I guess you just have to try and embrace it. I’m lucky because it’s got a degree of attention, and people are excited about it. That’s an incredibly privileged position to be in and not a lot of books get that. So, I’m gonna be talking to a lot of people about it, but what greater privilege is there than that, like? To be able to talk to people about your book all the time and get paid for it? It’s grand.

OH: What have you learned from writing the novel?

MM: I know that this is what I wanna do, and I’m serious about it. Understanding that it takes a lot of time and a lot of work. You can’t take any shortcuts. You have to put the work into it. But that shouldn’t be a chore. That’s just what it is, do you know what I mean? If it’s a chore, you’re fucked. If you can’t dedicate the time that’s needed then you’re bate, I think.

OH: You’re also the fiction editor of The Tangerine.

MM: Just about, aye, yeah!

OH: Tell us what makes someone’s submission actually stand out to you, how do you know when something’s actually ready to be out there?

MM: You know really quickly, like. You know within the first page if something’s good. It’s like watching a film, you know within the first minute or two. There’s never anything specific. The thing I really love about short stories is that it gives people space to do whatever they want, it’s an experimental genre, by its nature. It allows a writer to cut their teeth. Particularly Irish writers, that’s the way you learn. I think it’s never really about what the story’s about. It’s how it’s told. It’s the voice and the form that it exists in. Stories

are always the same story, and there are stories that are very unique but for the most part we know what a story is. It could be a day in the life, a marriage breakdown or an affair, or someone out on a big bender but you’ve read that story before. There’s never one particular thing that attracts me to a story, if anything it’s about reading something that’s telling the story in a way that surprises you. And you’re like, fuck, this is class, and it pulls you straight in. You’ll get a lot of competent writers, good writers, but they can be a bit dull or they’re taking it a bit too seriously. You always know when the person who’s written it has had fun and enjoyed themselves. You can feel that on the page sometimes I think, and then the reader buys into it, and the reader’s enjoying it. It’s pleasure, it always goes back to pleasure. Pleasure in reading and pleasure in storytelling. Pleasure in telling the story.

But if you read the fucking Tangerine I’ve published all sorts of madness, like. I think it’s really important to think about the people who you’re publishing as well. I wanna publish people who haven’t been published before. So, it’s not gonna be a masterpiece sometimes — sometimes it is, sometimes it’s incredible — but there’s something in them that just fucking gets you, you know what I mean. That’s the best, I think.

OH: In receiving submissions or reading other people’s work, or from your own experience, have

you noticed any really common mistakes fiction writers make?

MM: So many, mate. So many. I sound like a dickhead. But there’s a lot of, and I don’t mean to stereotype here at all, but I kind of am. Lads write stories set in bars all the time, like rural Irish bars. They love it. It’s just, like, old men sitting in a pub watching fucking hurling, talking about stuff. Or you’ll get a lot of “middle-aged man having an existential crisis and having a onenight stand with someone he works with”. Usually, a young and attractive woman. Happens all the time. I can’t even read them stories anymore. As soon as a story’s set in an office I’m like, “not doing it”. You’ll get a lot of stories about a young woman who’s caring for an older, sick relative. Always dementia? And just, tropes. People writing - and this goes back to what we were talking about at the start, writing our Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings fan-fiction. That’s grand, that’s part of the process of learning how to write. I genuinely think that everybody carries stories to tell. You know that whole thing of “everybody has a book”, they actually do, like. I think everybody you know is a storyteller.

OH: People forget they can write in their own voice, and their own voice is what makes it different. They’re trying to write in some big voice but they need their own.

MM: That’s it. It comes into what you think literature is, and people don’t get the vantage point that they’re at. Your voice is the thing, that’s the channel. A lot of tropes, a lot of weird stereotypes. But also just, like, fucking badly formatted stuff, too. I hate that. But you sort of look past that ‘cause there are a lot of good stories that are badly formatted. Some people have it naturally, it’s unbelievable. I remember when I was teaching on the MA at Queen’s and fuck me, like. Already there. They already have it, it’s just a case of doing the technical stuff.

OH: Going off that, what’s the best piece of advice you would give fiction writers, specifically students submitting to The Apiary? Anything in the process, and in submitting work as well.

MM: Taking as much time as you can over the piece of work is really important. Re-writing is really important. Editing the fucking thing is really important. Maybe show it to people before you send it out, ‘cause it’s good to get a gauge. And also keep yourself open to criticism. You want criticism. You want people to tell you what’s wrong with it.

OH: You do. It means they care.

MM: That’s it, like. There’s nobody at any point in their literary life whether they’ve been writing for six months or

fifty years who ought not to be open to editorial feedback. Even when you’re publishing books, you’re gonna get edited. So, I think the best way of preparing yourself for it is being open to it. Show your work to somebody else but not your fucking ma or your sister or relative, someone who’s actually gonna be honest with you, if you can. And for the longer picture, take time, don’t worry about being in a rush and don’t worry about publication. You’re gonna get rejected.

OH: Brilliant advice. What do you like to do when you’re not writing?

MM: What do I do? I go out with my mates and sit in bars and talk shite. I do a bit of running, go to the gym sometimes, not often. I don’t even really run that often, but I run sometimes. And I read a lot. I try and read a book a week. If I read a book a week, I feel good about it, if I don’t I get annoyed. And I watch films, good lot of films, lot of shite TV. All that shite. I wish I had interesting hobbies but I really don’t.

OH: Nothing weird?

MM: I’ve never been a hobby guy. I am attracted to the idea of picking up some hobbies. Would love to pick up fishing.

OH: Writing is obviously a very tough process, sometimes it can feel awful and scary, but what

about it brings you joy?

MM: When it’s working! It is a hard trade to get into. I see it as a trade. You start off as an apprentice, and I still see myself as an apprentice. This is my first book. Hopefully, I have a long career ahead of me, I don’t fucking know. Thinking about it in terms of being hard probably isn’t the way to think about it, it just is what it is. It is like doing it every day if you can, as much as you can. It is like reading books in a way that isn’t reading just for pleasure, you’re reading to learn, you’re trying to understand the effects people use and how it works on the page, how stories work. Sitting down with a pen and annotating and underlining and fucking trying to get it. You’ll only feel the biggest moments of joy when you’ve had a good day. You’re chasing that all the time. Say you sit down at the desk five days a week, four of them days might be shite. Sometimes two weeks might be shite, three weeks might be shite. You’re getting really annoyed at yourself because everything you write’s kinda crap. But the good day always comes. When you hit something that takes you somewhere and you go somewhere you didn’t expect, it’s there, this piece of fucking work that you’d never even imagined writing. That’s the juice. That’s the most exciting thing, I think. I think that’s the same with everything. I think it’s the same with poems. You could write twenty poems, hate them all, and then you write one and you feel good about it.

OH: Makes it worth it.

MM: I think that’s the joy, and we’re constantly chasing that hit. It would be amazing if you could sit down every day and have brilliant days of it. Some writers probably do, the bastards, but I certainly don’t. And that’s the thing as well, there is a lot of joy in it, just sitting down at a desk and writing. You sort of go somewhere else.

OH: Final question. In your own words, why do you think it’s worth it to write, and why should we write?

MM: That’s a hard question, that!

OH: What made it worth it for you? What made writing your novel worth it, or your short stories worth it? It wasn’t publication for you, was it? Or was it?

MM: I mean, everyone says “It’s nothing to do with publication”, but like, being published is fucking class. It’s unbelievable. You dream about it for, I mean, when I was 20 I was envisioning it. And then it got knocked out of me over the years, and then you have a much more ambivalent relationship to being published. It’s mad, I still pinch myself, mate, I can’t really get my head around it sometimes.

OH: I think everyone in Belfast is excited! It’s all over social media.

MM: It’s lovely, it’s really lovely. People are great, like. I think Belfast is part of the reason I’m still here, we’ve a good thing going here in terms of writing. I sort of forget how rich the literary environment is here because I’m not in it as much as I used to be. All through my twenties, I was so involved, doing events, open mics, magazines, everything. I went to every event. Why is it worth it to write? I could go really deep on this in a weird way but, whenever I wrote the early drafts of Close To Home, that letter, the early drafts were very cathartic for me. I was writing from this really personal place. I was divulging all this stuff about myself, stuff that I had never really spoken to anybody about before. From childhood, family, friendships, things I’d been involved in even as a teenager, mistakes I’d made in life, and writing the novel allowed me to think about those things head-on. I mean this sounds a bit fucking self-helpy, but it was really important in terms of allowing me to talk very directly about those things. And to confront them. And so there were things about my life that I felt very ashamed of. Ashamed of where I was from or ashamed of class, all that kind of stuff, you find yourself suppressing. I was trying to act like somebody I wasn’t in a lot of ways as well, and writing the book was almost an engine. A mode of thinking through it and articulating that experience that then allowed me to think about it differently. And even just to talk about it publicly with people, just having conversations about it.

That was a massive thing for me, like, regardless of the fact the book’s getting published, which is incredible. In terms of my own, I don’t wanna use the word mental health, but my own kind of sense of who I am and where I’m from, it just opened me up in all sorts of ways and made me a lot more comfortable, and allowed me to speak about things I otherwise wouldn’t, and that was the big thing for that book. I think writing can do that, that’s one of its great functions. Particularly when you’re writing from your own experience. It is heavily fictionalised at this point, but going through that experience of thinking about this stuff for five years will change your relationship to it, you know?

OH: Perfect answer.

MM: Thank you so much! So why should we write? Mental health! It goes back to what I was saying before of feeling a responsibility towards the place that I was writing about, and the people and the community that I’m from. There was this sort of niggle in my head that - and it maybe it comes from a place of self-importance in a way - if you don’t write the story, who will? That’s really important. It’s important for every writer to think like that, particularly when they have something to do.

OH: No one’s gonna tell it if you don’t, ‘cause no one can tell the same story you will, no one has your voice.

MM: That’s it! And it’s yours. Whenever it comes down to the history, often the best way to get a glimpse at a particular historical moment or society is through the novel. I mean, that’s what we do in literature, that’s what literature is. So, you’re contributing to that in some way, or at least, you’re trying to.

Suzanne Magee is a writer and visual artist from Belfast whose work has appeared in The Galway Review, Abridged, The Honest Ulsterman, Oxford University’s Tower Poetry series, SHIFTLit Derry, FourXFour, and others.

Andrew Mullan is a 2nd year English student. People are sometimes shocked to hear that he writes as he comes across “smicked out.”

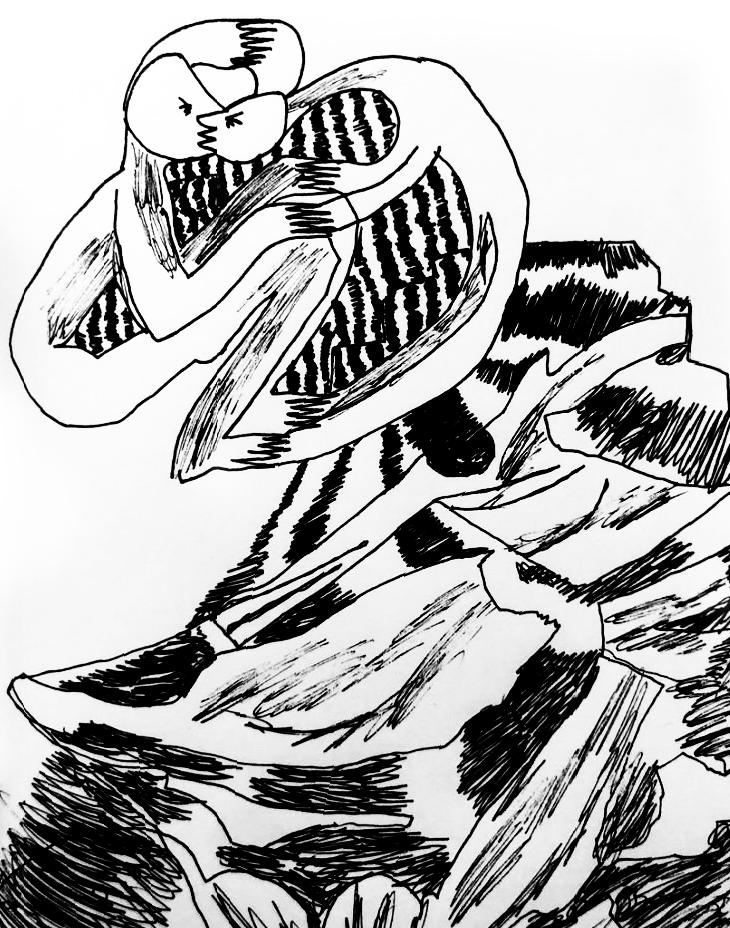

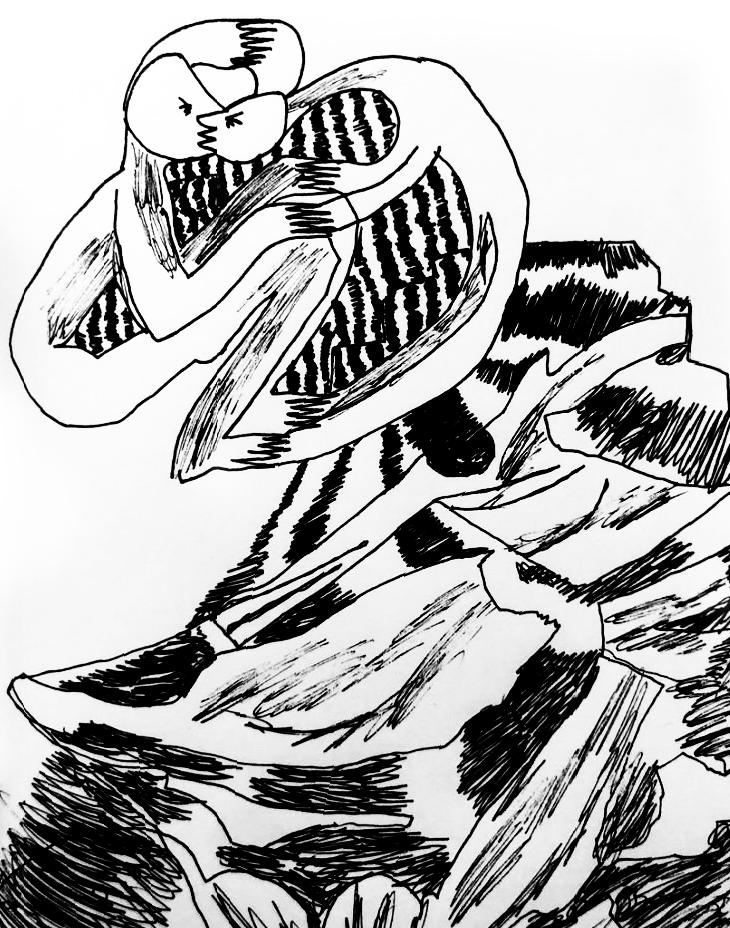

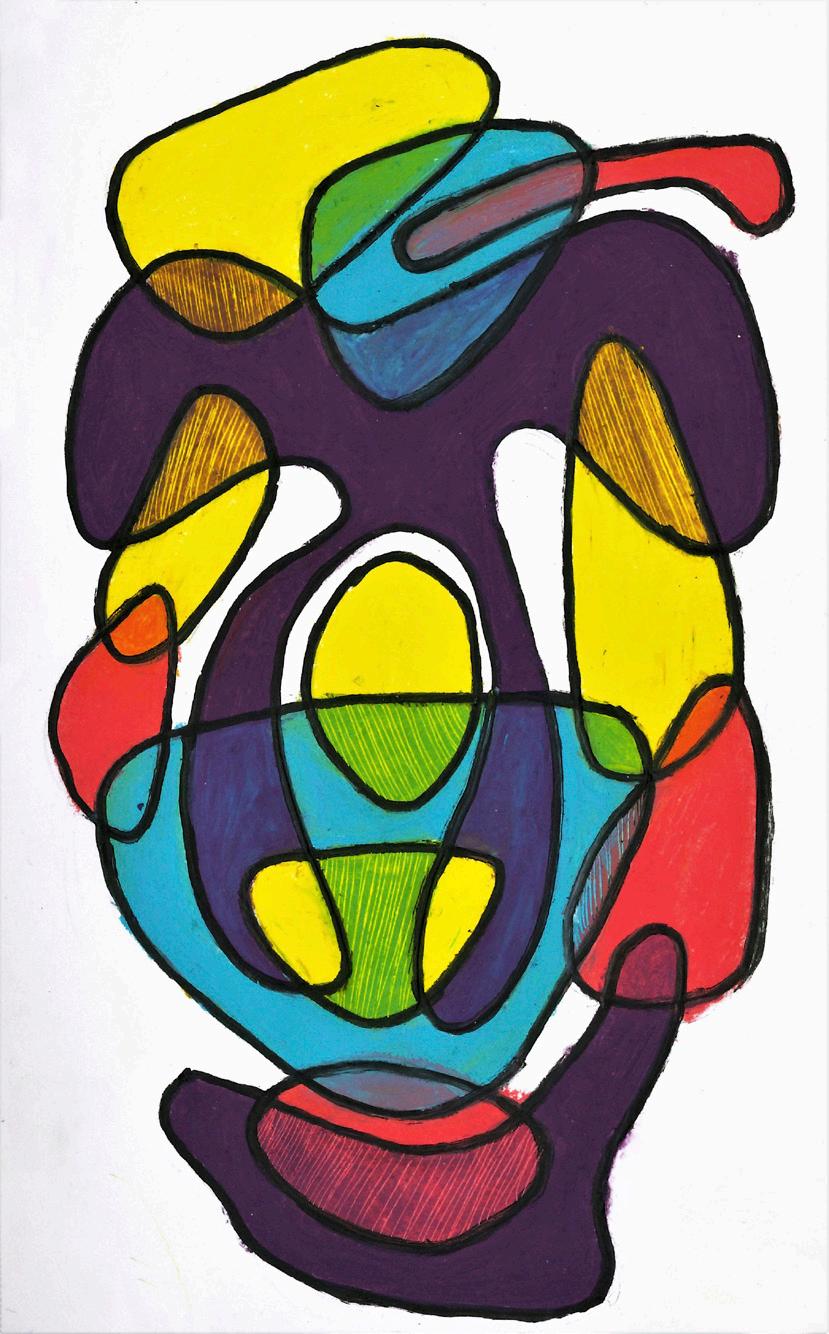

Floss Morris is an artist based in Belfast, studying Anthropology at Queen’s University. Though she feels pretty unqualified to use the A(rtist) word, she is quite lost without paper and pen. She is currently lost in Bulgaria, and may never return.

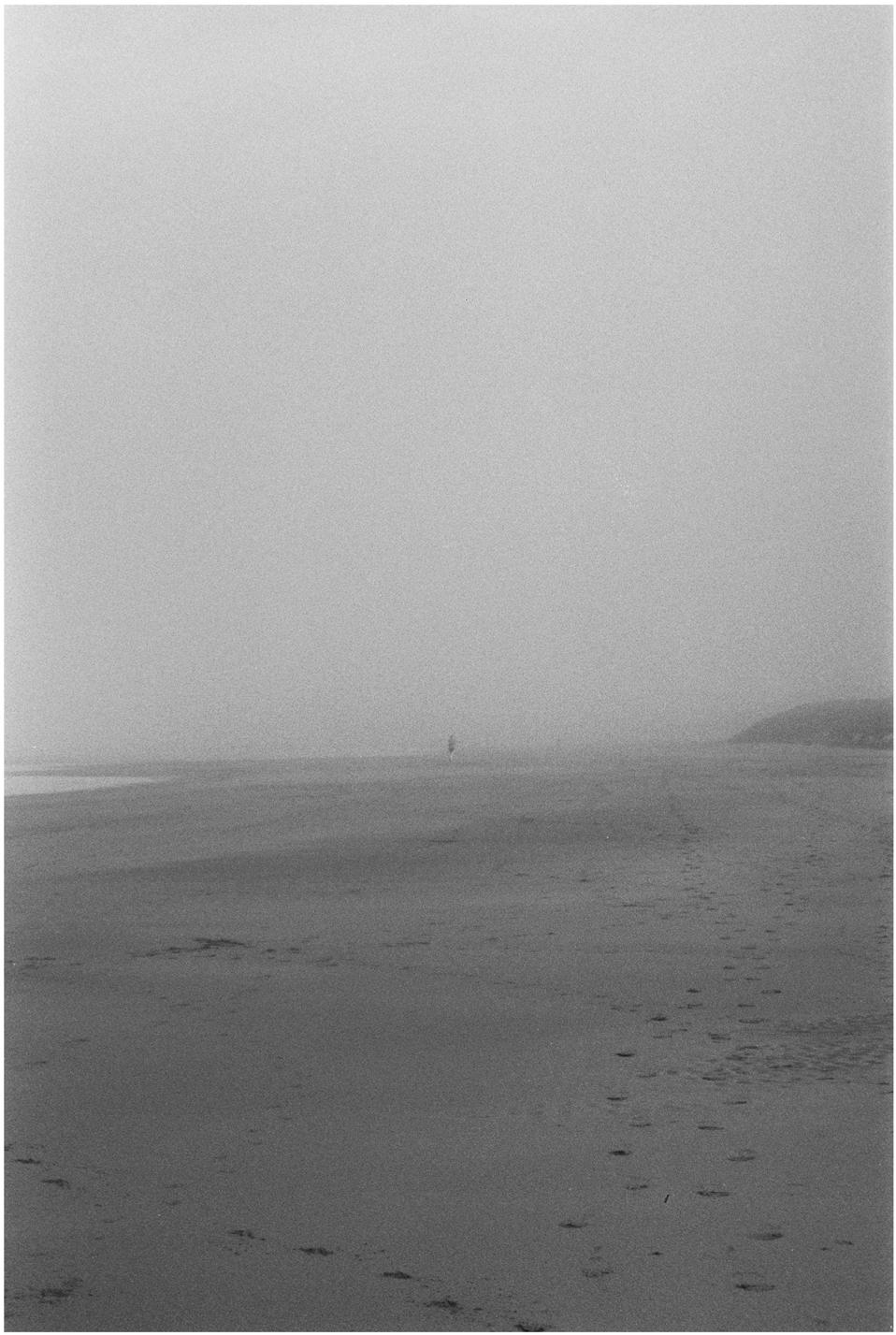

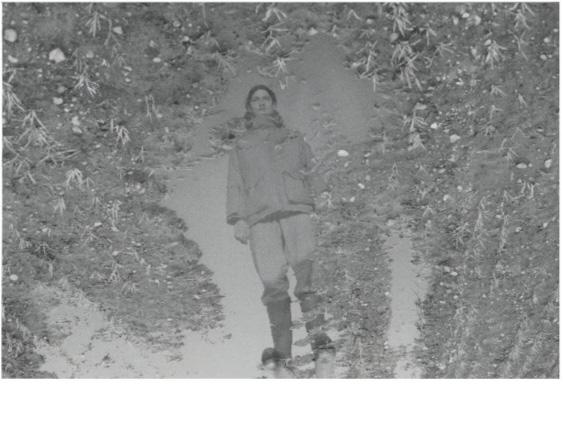

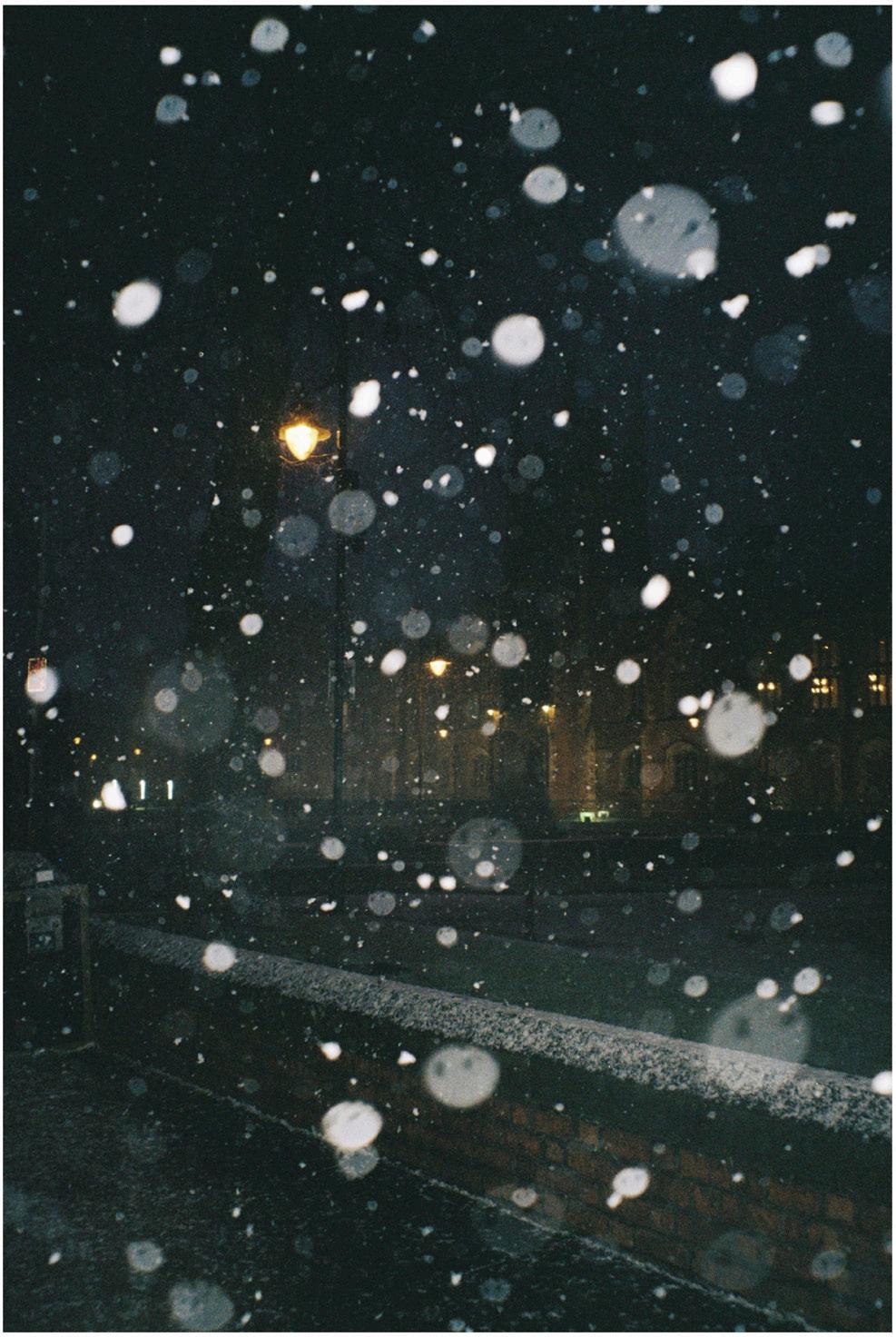

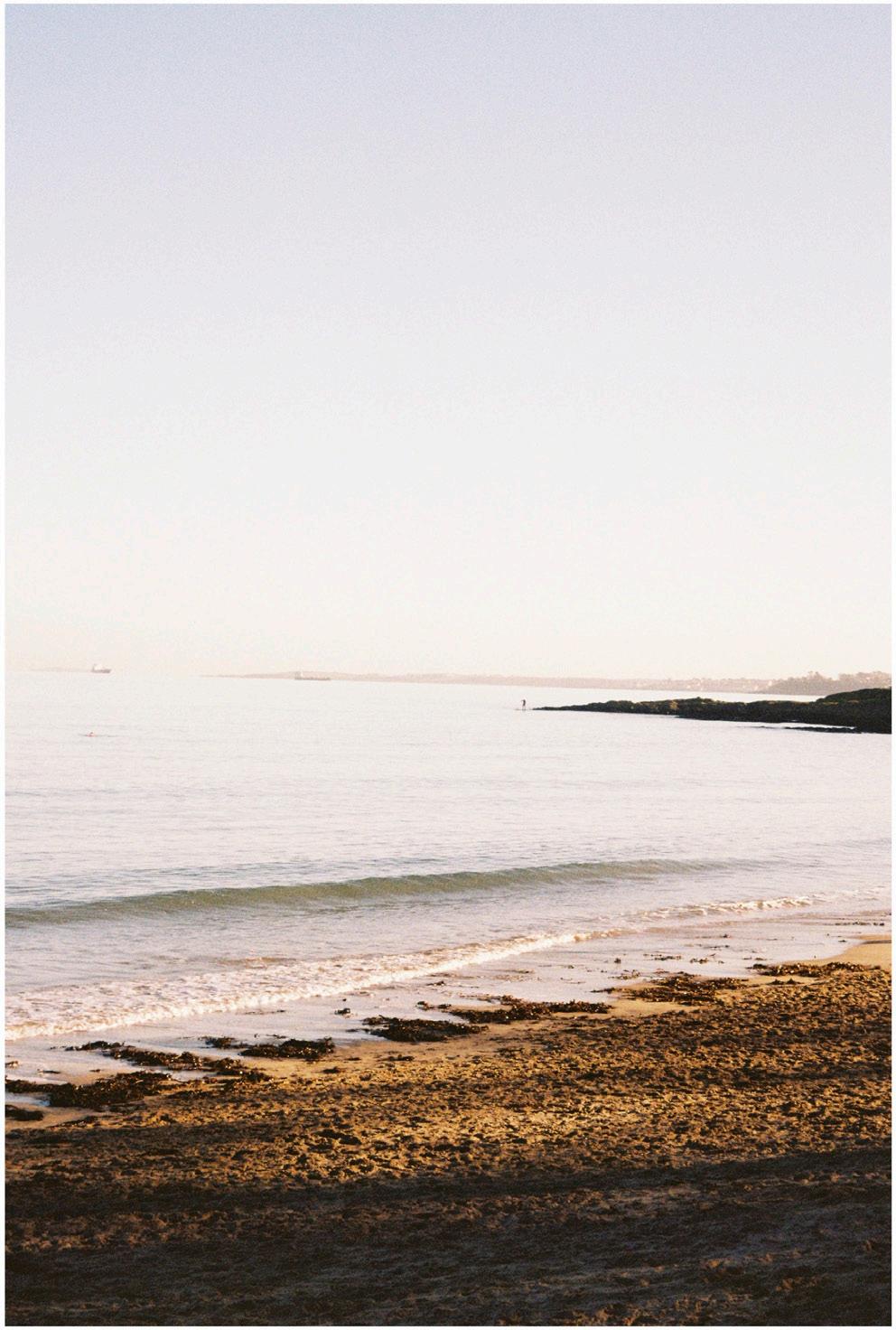

Ash Caulfield is a queer, disabled, Northern Irish amateur photographer. He enjoys candid photography and tends to shoot on film. He has previously had his photography published in The Apiary and displayed as part of an exhibition in The Void Gallery. He also occasionally writes, having previously authored articles for GCN.

Caitlin Young is a writer from Dublin living in Belfast. Her work can be found in Sonder Lit, The Honest Ulsterman, and The North among others. She graduated from QUB in 2022.

Shane Thornton is from South Armagh and is not a poet or a painter. Holylands resident.

John Moriarty lives in Belfast with his family. He has previously written for the Belfast Telegraph, Times Higher Education, BBC News NI and is a regular contributor to Slugger O’Toole. He is studying for a Master’s in Creative Writing at Queen’s University. His cat is currently blanking him.

Alanna Offield (she/her) is a disabled, queer, Chicana from New Mexico now living in the north of Ireland. Her poetry has appeared in Abridged, Rust+Moth, Porridge Mag, Cyphers, and other publications. She recently graduated from the Poetry MA at Queen’s University Belfast. She owns Seaside Books, an independent online and travelling bookshop.

Hannah Smyth is a writer based in Belfast. She studies English with Creative Writing at Queen’s University and has a deep love for the art of poetry, drawing inspiration from the work of favourite poets such as Federico García Lorca and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Stephen James Douglas is a Northern Irish poet and secondary school teacher. Stephen’s love for literature was born under the rueful gaze of his former English teacher at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, Frank Ormsby.

Hamish Harris is an aspiring photo-journalist from Cambridge. This collection of photos was taken whilst travelling around rural Ireland, spanning from July 2021 - February 2022, primarily during a pandemic summer in 2021. His aim was to translate the overwhelming beauty he felt whilst rediscovering nature, distorted with a sense of isolation after being locked inside for so long.

Hannah Johnston is a 2021 English graduate and writer from Belfast. Hannah writes poetry and prose that she performs frequently at various events throughout the city. In her spare time, Hannah attends and coordinates open mic events, runs a book club, and swims in the sea.

Molly McKillop is currently in her final year of her Master’s in Liberal Arts. She is focusing on Irish women’s writing, primarily on the work of Rita Ann Higgins. Her work has previously been published in The Apiary

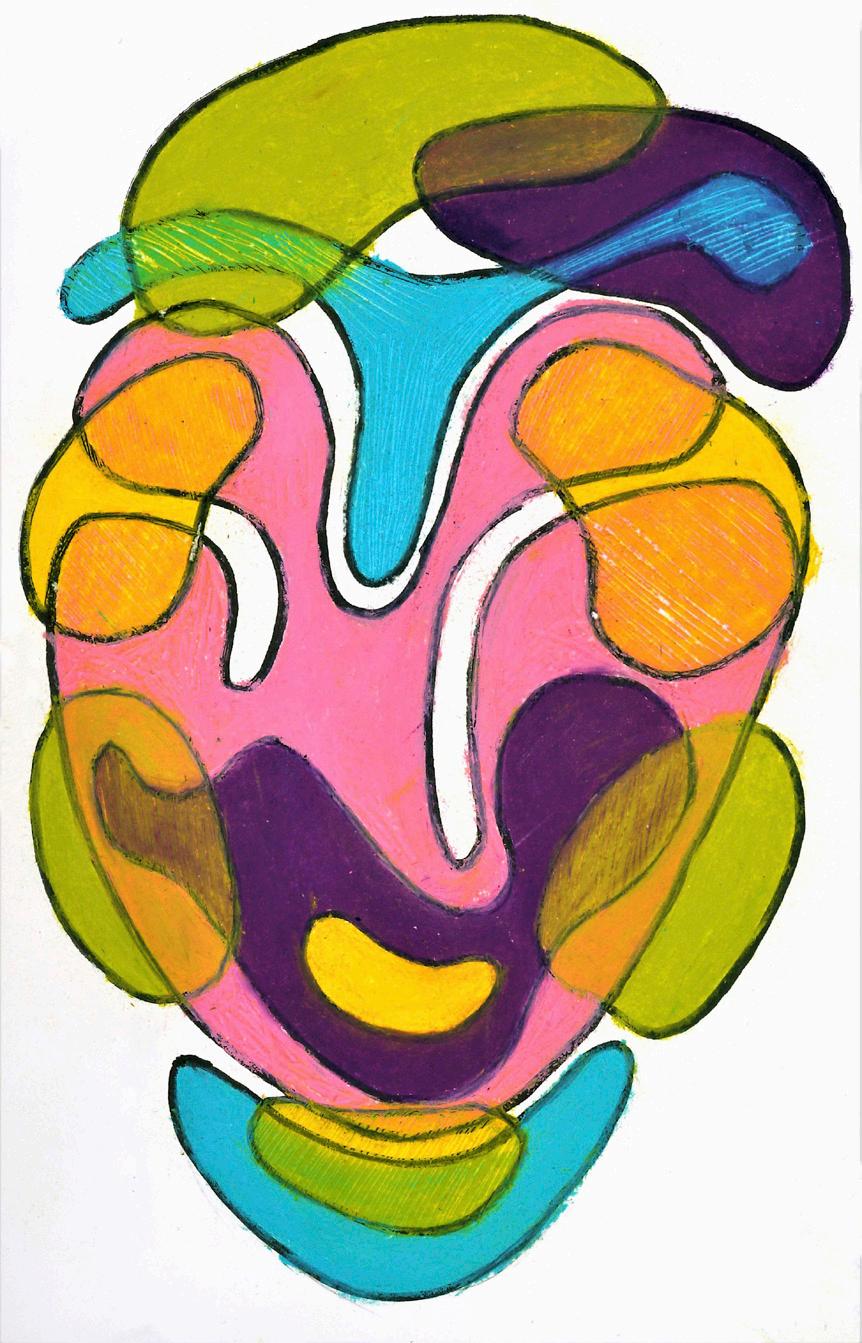

Arthur Cespon is a portrait artist based in Belfast. His artwork captures the authentic emotions of his subjects, inviting viewers to deeply connect. With a strong drive to learn and grow, Arthur constantly explores new techniques in both digital and traditional media.

Stacey Denvir has recently graduated from Queen’s with an MA in Poetry.

Sylvia Bosky was born in Budapest, Hungary and now lives in Belfast. Originally trained as a fashion designer and receiving a BA degree in Music, she works in various mediums, such as oil, watercolour, and digital art. Her work is inspired by nature, spirituality, and dreams.

Anesu Khanya Mtowa is a Black Lesbian living in Belfast. They are studying Nursing at Queen’s University and write poetry whenever they find the time. Their work can be found published in the Awkward Middle Children and Her Other Language anthologies. Any upcoming work is also a mystery to them.

Cullan Maclear is a poet and visual artist whose work centres on manhood, mysticism and ecology. Born in Cape Town, he is now based in Belfast, where he is pursuing an MA in Poetry from Queen’s University.

Joseph McGinty is from Achill. He completed his BA degree in English and Music at University College Dublin, where his poetry was featured in their Caveat Lector publication. He is currently undertaking a Master’s degree in Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast.

Caoimhe Bassett (she/her) is an MA Creative Writing student at Queen’s, originally from the same town in Essex where they film TOWIE. She hopes never to return home from Belfast.

Brian Kerr is a writer from Belfast, attending Queen’s University. His work mostly consists of poetry. If he doesn’t listen to LCD Soundsystem every day, he’s just not himself.

Michael Magee is from West Belfast. He is the fiction editor of The Tangerine, and his work has appeared in Winter Papers, The Stinging Fly, The Lifeboat and in The 32: An Anthology of Working Class Writing. He recently gained his PhD in Creative Writing from Queen’s University, Belfast. His debut novel, Close to Home, was published by Hamish Hamilton in spring 2023.

Cover art by Floss Morris.

Olivia Heggarty is a writer based in Belfast, studying English at Queen’s University. She is the very proud editorin-chief of The Apiary and her work has been published in various journals and anthologies.

Emma Buckley is a writer and editor currently studying MA Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast. Her poems can be found in The Honest Ulsterman, Superfroot, The Lumiere Review and Catatonic Daughters

Anna Gordon is an undergraduate English with Creative Writing student and PR officer of the QUB Writers’ Society. She has a passion for film and her work consists of screenplay, short fiction, and the occasional poem and film analysis. You can find her in Púca Magazine and For Page and Screen.

Lucy Hatton is a Belfast-based writer, editor, and final year English and Linguistics student. She is VicePresident of QUB’s English Society, and loves discovering and uplifting Belfast’s new literary talent.