By Francesca Pica & Ava Menkes

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF & MANAGING EDITOR

Rhetoric from Trump’s administration insists that our nation’s immigrants are the “other” — but immigrants are foundational to the past, present and future of the United States.

This action project explores how Wisconsin’s key industries, educational institutions and cultural centers rely on the state’s immigrants and their families, and what happens when they are targeted.

Wisconsin immigrants are parents, children, workers and students. They’re the artists that push creative boundaries and challenge

audiences. They’re the student athletes that don red and white to bring glory to the Wisconsin Badgers. They’re the backbone to Wisconsin’s agriculture. They’re the instructors that teach University of Wisconsin-Madison students languages they would not have access to otherwise.

Instead of celebrating this multiplicity, our federal government is eliminating research funding, cutting diversity-based scholarships and threatening to revoke student visas, throwing students’ lives and education into chaos.

Students fear now more than ever that their identity puts them at

risk for arrest and potential deportation. They fear important education and job opportunities will be lost to them and that the federal government may close their program with the stroke of a pen.

Meanwhile, many refugee programs struggle to operate due to federal funding cuts, scrambling to provide answers to immigrants and refugees fearing the worst.

Still, there is hope. Community members at the campus, local and state level have stepped up to provide support where our government has not. Wisconsin religious organizations act as sanctuaries offering vital services for families.

Local law firms are working tirelessly to make sure immigrants in their communities know their rights. And UW-Madison students are taking steps to ensure their campus is safe for students with immigrant backgrounds.

While there are uncertain horizons surrounding immigration policy, one thing remains clear: immigrants and their contributions cannot be erased. With resilience, solidarity and advocacy, we hope readers can appreciate how integral immigrants are to our state’s identity, education and workforce.time, if one really does, that’s still a negative. That’s bad for democracy.”

By Gavin Escott CAMPUS NEWS EDITOR

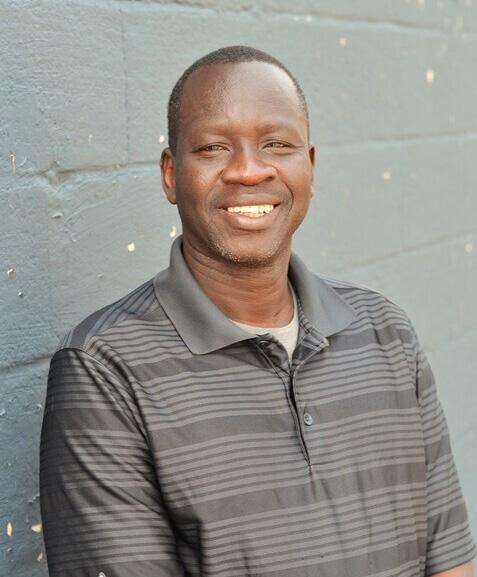

Hillary Jones Henry faced tough choices when he received his February stipend for teaching Swahili at the University of Wisconsin-Madison six days late, receiving one-fourth of the promised amount.

A native of Kenya, Jones Henry teaches under the federally funded Fulbright Foreign Student program, which places hundreds of foreign language instructors at universities across the United States for an academic year. The eight Fulbright Language Teaching Assistants (FLTA’s) at UW-Madison for 2024-25 are paid by the federal government, not the university and when the Trump administration froze State Department grant payments in early February, some couldn’t pay basic living expenses.

“I had to do weighing to find [what was] the most important,” Jones Henry told The Daily Cardinal. “I decided that my food was more important than the rent.”

Thankfully, Jones Henry’s landlord, a UW-Madison professor emeritus, was understanding of his situation. Still, some FLTA’s couldn’t make rent on time and were forced to leave their apartments, as Fulbright was slow in providing more details about upcoming payments.

“They did not explain the future [and] we were left in the darkness,” Jones Henry said. “You didn’t know whether they are going to pay the next [stipend] or they are not going to pay.”

FLTA’s key in bridging cultures but under threat, FLTA’s say

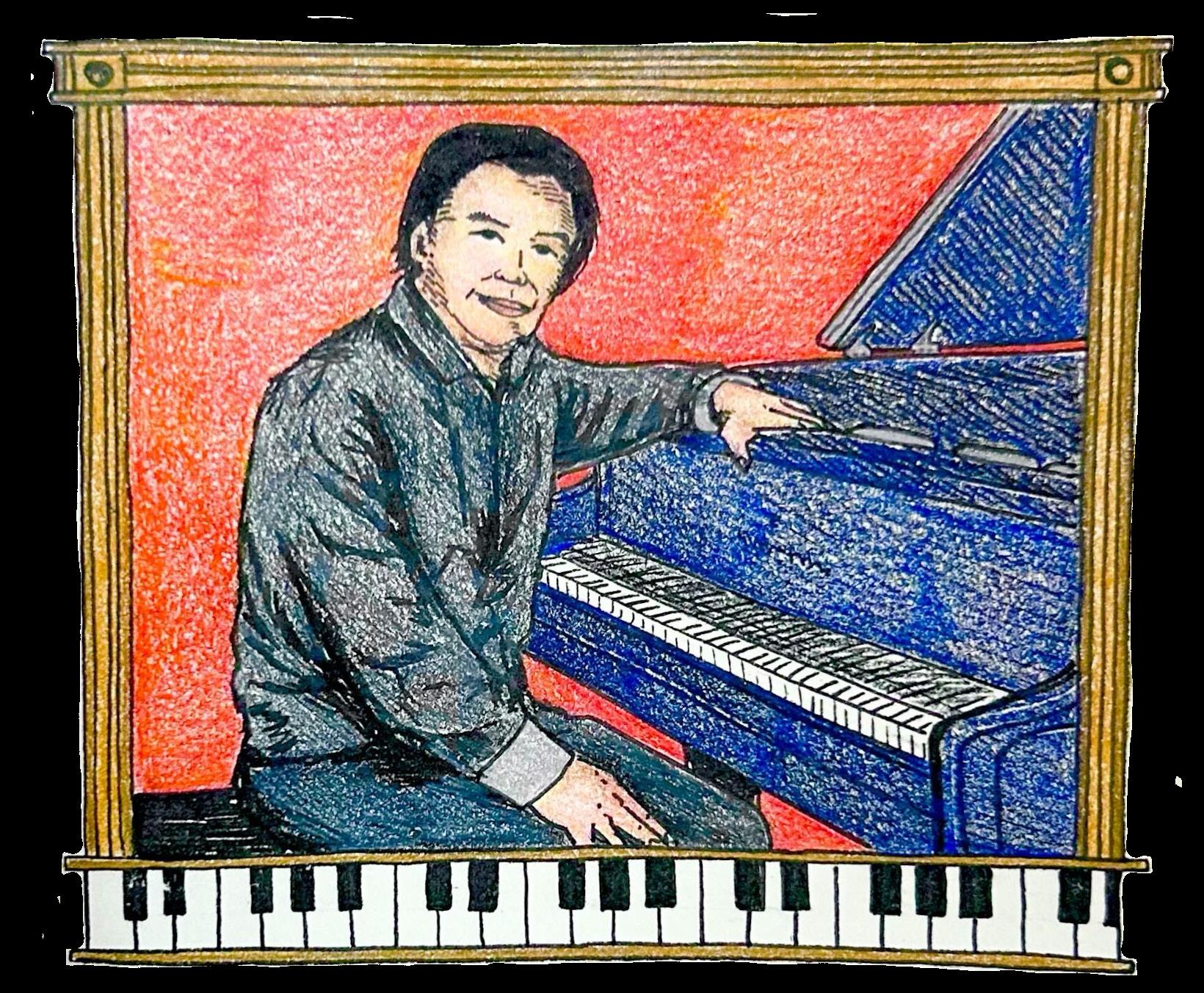

Established in 1967, the FLTA program was designed to facilitate the learning of other cultures and languages for Americans, and develop the English and U.S. knowledge for foreign instructors. Onsee Khamphouvong, a UW-Madison FLTA who teaches Lao, described FLTA’s as “cultural ambassadors.”

“[FLTA’s] are not only teaching a language, because teaching or learning language, it means that you are learning other cultures

as well,” Khamphouvong told the Cardinal, adding he teaches, audits classes and participates in cultural events in Madison.

At UW-Madison, FLTA’s teach a variety of less commonly taught languages, including Yoruba, Zulu and Thai. For some of the languages, particularly in the African Cultural Studies Departments, they are the sole instructor, especially at the more advanced levels.

But recent events have thrown the future of such programs, and the people and languages they support, into doubt.

On Feb. 13 the State Department initiated a 15-day suspension of federal grant funding for various international and educational programs, including the Fulbright program. The suspension, which aligns with the Trump administration’s broader pattern of slashing government funding to eliminate perceived wasteful spending, was later extended and has still not been fully restored.

FLTA’s receive paid flights to and from the U.S. and monthly stipends of $1,320. Jones Henry and Khamphouvong expected to receive their stipend on Feb. 22, but the date flew by with nothing.

Though a check arrived on Feb. 28, it was only $330, below the rent they pay, and came with no explanation.

During this time, UW-Madison was “very helpful,” providing vouchers worth 10 meals and $400 for groceries, multiple FLTA’s told the Cardinal. Jones Henry added that Madison food pantries were also a big support and said some people who sympathized with them gave money.

A week after, Fulbright informed participants delays were due to a “temporary pause,” stemming from a new administration. And though the remaining stipend amount was paid a few weeks ago, and March’s stipend was paid on time, they weren’t given guarantees that April or May’s stipends wouldn’t be disrupted, Jones Henry said. His biggest concern is whether Fulbright could pay for his return flight to Kenya in May, something made more difficult as the Fulbright administrator in charge of flights

was laid off.

Jones Henry voiced his view that the situation “wasn’t of [Fulbrights] making,” but instead one created by the federal government. When he came to the U.S. in August he received a warm welcome but feels more alienated in recent months, he said.

“When the new administration came in, that was the first time I started feeling the sense that I am a foreigner in this land, and perhaps my services are not all that valued,” Jones Henry said, adding he wouldn’t have come to the U.S. if he knew what the situation would’ve been.

Future of programs, languages in doubt

Demand is not equal among the roughly 50 languages UW-Madison offers, and some of the classes FLTA’s teach have one or two students. Without the Fulbright program, there is a possibility there would be no instructor for those higher levels, an administrator who asked to remain anonymous said, adding it could be difficult to justify hiring a faculty member for a class so small.

“If they cut [Fulbright] completely, or they do away with it, then I don’t think the [African Languages Department] will have enough teaching assistants to carry out that job,” Jones Henry said.

African Languages Program Director Adeola Agoke told the

Cardinal she didn’t currently have information to share if certain programs would be discontinued.

Even though enrollment may be small, the skills taught in these classes are important, Jones Henry said, noting if these lesser-spoken languages were not taught it could lead to less engagement with the rest of the world.

“There is no better way you can appreciate other people’s culture than to learn their language,” he said.

Khamphouvong echoed this and said that though social media could connect people across the world, it “wasn’t enough” on its own.

“It’s [more effective] to allow other FLTA’s or people from other countries to come so they can interact with people in person,” Khamphouvong said, referencing a presentation on Laos he did on campus earlier this year. The majority of the attendees knew nothing about Lao at the start, but by the end they were dancing to the music and really enjoying it, he said.

“I would like them to keep this kind of program, but even if we don’t get any support from the federal government, maybe the university should have some kind of budget so that we can keep our program,” he said.

When asked if he would recommend people eager to become a FLTA to still apply, Jones Henry said the program was very beneficial but advised caution.

By Sreejita Patra SENIOR STAFF WRITER

In wake of the Trump administration’s suspension on new refugees entering the country and stop-work orders for federal funding, Madison’s Open Doors for Refugees (ODFR) programs are having to pivot their traditional service structures and, in some cases, drastically cut staff and day-to-day operations.

Founded in 2016, ODFR is a volunteer organization that helps refugees with housing, transportation, English language learning, community integration and more. The program partners with Madison social services agencies such as Catholic Multicultural Center (CMC) and Jewish Social Services (JSS), both of which have worked with refugees since the 1970s.

“I am hopeful that court cases will challenge or reverse the current ban so there will be some refugee resettlement,” ODFR Executive Director Jason Mack said. “But I am not planning on it ever getting back to the levels that it was.”

No new refugees, no new funding

Individual donors and grants completely fund ODFR and mostly fund CMC. But for JSS, ODFR’s closest partner in helping refugees through their first 90 days in Madison, federal

funding was the bulk of their support.

“We’re having to tell refugees who came after Jan. 24 [that] even though you heard from community members who came before that we can provide, say, funding for your rent, we don’t have the same resources anymore,’”

JSS Executive Director Kai Mishlove told The Daily Cardinal.

JSS, which works under the national refugee resettlement agency Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, signed its federal funding contracts for staffing and programming months in advance. Having resettled 52 refugees between the beginning of their fiscal year in October and Trump’s stopwork orders, the organization is now not being reimbursed for the thousands of dollars they already spent as per their contracts.

“It’s a very, very fluid and crisisfilled situation that causes a lot of anxiety,” Mishlove said. “It’s a breach of contract that really puts our agency at risk.”

In response to the funding freeze, JSS has had to lay off the majority of their staff, leaving a longer waiting period for their services as the remaining staff members work with higher caseloads. The organization has also reported receiving multiple threats to their safety and reported having their location published online by white supremacist groups who accuse

them of “aiding in the blackening and browning of America.”

Afghan refugees speak out

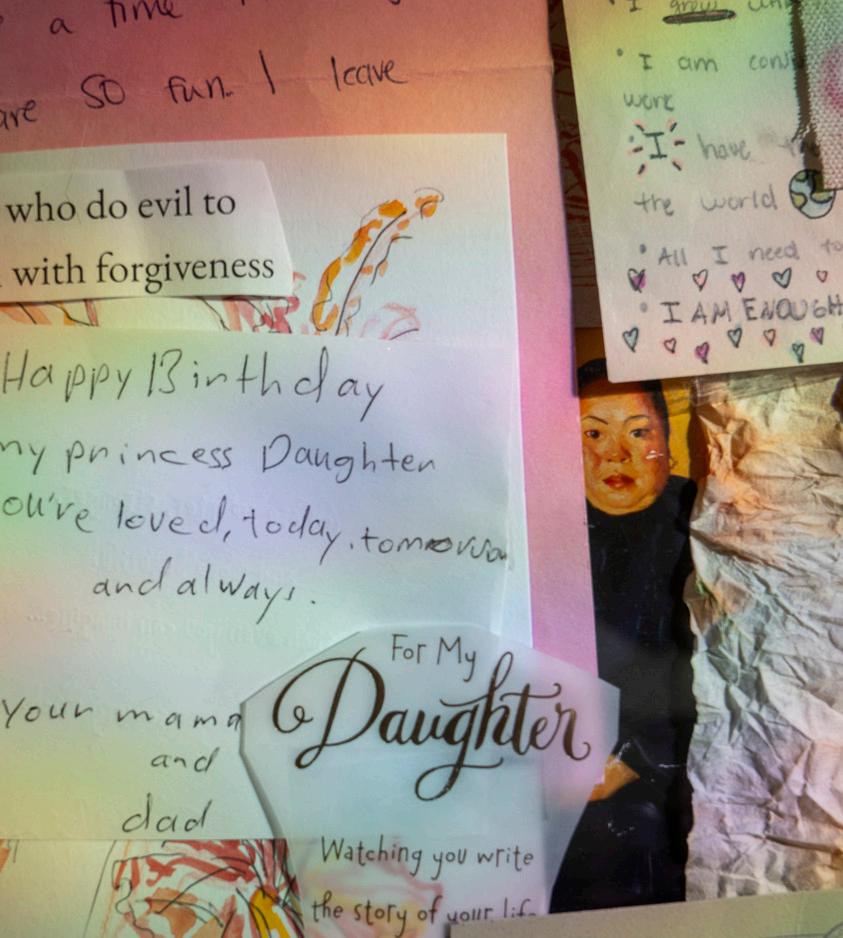

Since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, Afghans have comprised a large percentage of the total refugee population in Madison. But when ODFR board member Abdullah Ameen and his family fled to Madison in 2014, he was one of few Afghans in the city.

“It was not easy to find people, people to talk to and share your concerns with who would understand your language and your culture,” Ameen said.

Ameen came to the United States on a special immigration visa after he was threatened for working with USAID. Lutheran Social Services paid his family’s rent while he searched for full-time work, landing an NGO job a few months in and taking up UW-Madison cartography classes at night.

“Newcomers start their lives from zero and are not part of the society for a long time,” Ameen said. “Now as a volunteer leader for the community, I try to help with everything I can, from driver’s tests to job interviews.”

Ameen said Afghan community members are widely suffering due to the current travel ban, separated from families waiting for their cases

to proceed as Afghanistan’s political situation remains volatile. One such example is JSS Refugee Resettlement Director Zabihullah Sahibzada, who said his brothers are being tortured for information about his whereabouts while his daughters are banned from education above sixth grade.

“I have to speak to my family every night and every morning, video call and tell them things will get better,” Sahibzada said. “I don’t see any hope. My girls don’t see any hope. My oldest daughter is 16, and it’s been three years that she’s not going to school.”

Despites his fears, Sahibzada said the support he received from JSS and the Madison community when he arrived was “unforgettable” and is continuing to help JSS provide resettlement services to around 450 people. He said now is a time for people to come together and stand with refugees who are already here.

“It is the responsibility of communities here to provide refugees cultural orientation, tell them the ‘do’s and don’ts’ and show them ways to make their lives better,” Sahibzada said. “It is a humanitarian act, supporting these people who are in danger around the world.”

Organizations work to address settled refugees’ needs

Despite uncertainty about

the future, ODFR and its affiliate organizations remain committed to helping refugees like Ameen any time between 90 days to five years after they first arrive. All organizations rely heavily on individual and community support for their services in the form of volunteers and donations of all kinds.

“We have a lot of people coming in and saying they want to help us,” Mack said. “So we’re continuing to look at opportunities to serve the refugees already here and put the volunteers into the field, such as with our new child care program.”

And CMC Associate Director Becca Shwartz told the Cardinal the center has launched a new mental health program for the immigrant and refugee community, seeking to provide language-accessible mental health support specifically designed for refugees and encourage their pursuit of mental health-related careers.

The initiative is also partnering with UW-Madison’s Wisconsin Center for Education Research to identify existing barriers to immigrant mental health services and their solutions.

“Where I don’t think the federal orders are affecting us is in the work that we’re doing to serve those in need,” Shwartz said. “We look forward to continuing our role with Open Doors and other partners to help immigrants in our community.”

By Elijah Pines SENIOR STAFF WRITER

University of Wisconsin-Madison student John always dreamed of teaching. He came to the United States for his doctorate because he believed its multiculturalism would expand his perspective.

But recent events have left John, a teaching assistant working toward his doctorate, worried about how much time he has left in the country. Though proposed National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding cuts haven’t directly affected his department, UW-Madison has instructed departments to develop budget reduction plans in preparation of more funding cuts and John expressed his concern that anything his department says “against [the Trump] administration” might put a target on his back.

John isn’t alone in feeling this way. Between the Department of Education’s orders to eliminate racebased programs including diversity scholarships, cuts to research funding and crackdowns on students participating in protests, international students are weighing whether to stay or find another country.

International students chilled into silence, students say

In March, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) revoked Columbia University student Ranjani Srinivasan’s student visa after police arrested her for walking past Columbia’s student encampment last spring.

John was stunned when he saw Srinivasan’s story. If that could happen to Srinivasan, a student who didn’t

participate in the protest and whose charges were later dropped, John wondered how the U.S. government would treat him considering he actually participated in last spring’s pro-Palestine protests.

“We feel that we are outsiders already,” John said. “And [Trump’s] highlighting that and giving it legal backing.”

UW-Madison student Jane, who also participated in the demonstrations, echoed these concerns. The Daily Cardinal is identifying John and Jane by pseudonyms due to privacy concerns.

Jane came to the U.S. because she considers it the “land of opportunity,” and over the past few years, she has built a strong web of friends and family. But recently, her mind has been occupied by fears of being plucked off the street and never seeing the people she cares about again.

Compared to last spring, Jane feels far more paranoid about being able to express her opinion, especially online, and Jane expressed worry her social media could make her a target.

“I had to take down a GoFundMe that was on my page for my friend that lives in Palestine because I was worried that that would also be classified as antisemitic, and then they [would] take me back home,” Jane said.

Where Jane saw academia as an opportunity to leave her country, John always planned on returning home. But for his colleagues, he said deportation means reconsidering their whole life plans.

“There are other people, too, from other places in the world where it’s very hard to go back, and they came here as part of a long-term plan,” John

said. “That ability to speak and to be themselves in this country, if all of that is going away, then what do those people do in that circumstance?”

Budget cuts put job prospects further out of reach

For international students, academia is a pathway to securing a job, and if students don’t achieve a job in the U.S. after graduating, they pursue a higher degree to bolster their prospects, John said.

As an undergraduate, Jane is already thinking about graduate school as a way to make her more competitive. But as universities admit fewer graduate students and stop diversity, equity and inclusion programs, Jane is looking to other countries for opportunities.

“How things are unfolding in the United States, it seems like it’s not a place that would welcome someone

like me,” Jane said.

International students can’t legally stay in the country without either being enrolled in school or being employed. When summer break comes, many international students return to their home countries, which Jane said she would do, though she worried about returning in the fall.

UW-Madison recommended lowering the future amount of graduate students they take on in future semesters, and while John is secure in his department for now, he knows others that just barely missed the boat.

John has been looking at universities to protect their international students from targeting by the federal government.

“I hope that the universities will not be afraid to fight this,” John said. “They have to embrace themselves and connect to each other and fight collectively, because individually, they don’t work.”

By Joseph Panzer SENIOR STAFF WRITER

On Jan. 21, the Department of Homeland Security issued a statement canceling a President Joe Biden-era policy that prevented U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents from conducting raids in “protected areas” like churches and schools.

Religious organizations nationwide have filed a lawsuit arguing that this directive impacts their religious freedom. The Wisconsin Council of Churches (WCOC), a statewide network of churches and other faith-based organizations representing 23 Christian traditions, is a party to the suit.

Rev. Breanna Illéné, director of Ecumenical Innovation and Justice Initiatives at WCOC, said the directive goes against the mission of churches.

“We need our churches to be able to continue to provide the care their communities need and if they aren’t safe spaces because people fear being picked up by ICE, they are unable to fulfill their mission and people’s right to worship freely is being violated,” Illéné told The Daily Cardinal in an email.

Undocumented immigrants often rely on faith-based organizations for access to food banks, social networks and mental health services due to the perception that these are trustworthy institutions, according to the Stanford Social Innovation Review. The same article found that this perception was especially true for Latino immigrants under President Donald Trump’s first administration.

Some organizations will cautiously comply with the order in lieu of a

direct legal challenge. The Catholic Multicultural Center (CMC), a Madison-based organization that provides charitable resources to the community from a doctrine of Catholic social teaching, has said that they will only comply with the parts that allow ICE to enter public spaces.

“[ICE] would be allowed into the public areas of the CMC (parking lot, lobby and reception area) and asked if they required assistance,” Steve Maurice, director of the Catholic Multicultural Center, told the Cardinal. “All other areas of the building (classrooms, offices, chapel, program spaces) are designated as private areas and ICE agents would need to show a judicial warrant with specific information to be allowed into those areas.”

Churches remain undeterred in offering social services

Despite the looming pressure of this order, faith-based organizations still plan on offering services to undocumented immigrants in their communities.

In an interview with WPR, Lutheran bishop Anne EdisonAlbright has said that her church, a member of WCOC, will work to keep providing ministry for vulnerable members of society in light of the immigration order.

In Madison, the CMC has worked with other local organizations to make immigrants in their communities aware of their legal rights in the U.S., Maurice said. The CMC is also continuing to offer ESL classes, employment assistance and immigration legal services for low or no income recipients.

Immigrants who receive legal counsel at little or no cost will often have greater understanding of their rights and better chances of winning the right to remain in the U.S., according to the New School’s Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy.

“The CMC will continue to serve our immigrant neighbors through our basic needs, education, legal and employment related programs, and we will do our best to meet needs as they arise,” Maurice said.

Wisconsin churches have historical significance to immigrants

Wisconsin churches have a long history of offering services to undocumented migrants due to their pivotal role in the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s.

In 1982, three Catholic churches in Milwaukee opened their doors to Central American refugees escaping violence in El Salvador and Guatemala, becoming the first Catholic churches in the Sanctuary Movement and inspiring similar amnesty programs throughout the Midwest. The following year, St. Francis House Episcopal Church in Madison became the first Episcopal church in the country to offer sanctuary for Central Americans.

In 1985, Democratic Gov. Tony Earl declared Wisconsin a “state of sanctuary” for Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees in an act that did not bar immigration officials from entering churches but still carried symbolic weight.

Giving shelter to immigrants who have been displaced by violence is viewed by some faith-based organizations as an essential ser-

vice they provide.

“Many [immigrants] have homelands that are economically unstable, torn by violence or ravaged by war,” Maurice said. “In a country composed of immigrants, the demonization and scapegoating of newcomers has been repeated throughout our history, but justice and the common good is best served when we recognize the difference between a threat and an opportunity.”

Groups challenging the immigration order also cited the history of Christianity and Christian moral teaching.

“Christians across time have been migrants and have also been the people welcoming migrants,” Illéné said.

“Our faith calls us to welcome the stranger and love our neighbors, this includes those who are crossing borders and are new in our communities.”

Latin organization supports churches, condemns Trump administration’s decision

Voces de la Frontera, a nonprofit organization advocating for increased civil and worker’s rights in Wisconsin’s Latino

community, has called the recent move to allow ICE into churches as an attack on immigrants.

“Voces de la Frontera condemns any policy that allows ICE and law enforcement agents to enter schools, medical centers, and houses of worship to arrest immigrants,” communications director Alexandra Guevara told the Cardinal. “Such orders not only sow confusion and fear, but they also undermine the vital role that places of worship have long played as sanctuaries for immigrants in need of safety and community.”

Marquette University history professor Sergio González has stressed in an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio that during the Sanctuary Movement, churches in Wisconsin acted to shelter immigrants without federal government approval in moves that transcended religious, racial and even national boundaries. These actions tie into a greater ethic of human rights that Voces de la Frontera wishes for churches to uphold, Guevara said.

“[The churches’ legal actions] not only defend their right to provide sanctuary but also uphold the principles of religious freedom, human rights and decency,” Guevara said

By Ella Hanley ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR

At its core, the University of WisconsinMadison’s Advocates for Immigrant Rights (AIR) wants to create an environment where students feel comfortable discussing immigration issues — often a sensitive and deeply personal topic.

In 2020, law students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison founded AIR after identifying a gap in student organizations focused on immigration law. Initially composed mainly of law students interested in pursuing careers related to immigration law, the organization has since expanded significantly among undergraduate students.

As undergraduate students, they cannot

provide legal advice, but they prioritize education and awareness, supplying members with resources such as volunteer events and other organizations to help them get involved with immigration-related issues in the Madison area.

“I don’t want this fear, anger or passion to die out with a change in administration,” an

AIR board member told The Daily Cardinal.

“The state of immigration is dire regardless of who’s in office. I want to see undergraduates, graduates, faculty, community members — everyone involved.”

AIR board members asked to remain anonymous, citing safety concerns.

Beyond advocacy work, AIR places a strong emphasis on building a sense of hope among its members through monthly discussions on

current events relating to immigration justice. AIR board members said these meetings allow students to share their thoughts in an open and nonjudgmental setting.

“We really just try to foster an environment in which students feel safe and comfortable asking sensitive questions,” an AIR board member told the Cardinal.

Group members mentioned that in recent meetings, they’ve struggled to comprehensively address every important immigration issue that arises. With only one meeting per month, the capacity to cover everything — especially amid the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants — is limited.

Additionally, AIR hosts two large-scale events each semester, including Immigration Justice Week — a collaborative effort with other advocacy groups, such as UW-Madison’s Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) — focused on educating and empowering students and community members to get involved. These events provide opportunities to hear from guest speakers, attend workshops and participate in networking activities designed to build stronger relationships between advocates.

Through events like Immigration Justice Week’s “Know Your Rights” workshops and panels with immigration experts, board members want to ensure that students are wellinformed of their rights.

While immigration policy has long been a contentious issue in the United States, recent political events, such as the Trump administra-

tion’s crackdown on immigration, have mobilized law students to take action. One AIR member noted that, while it is unfortunate that advocacy is often sparked by crises, it is still encouraging to see students stepping up.

This growing engagement has translated into increased membership, more collaboration with other student organizations and a stronger presence on campus.

Recently, the group collaborated with SJP for a walkout in support of Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University graduate and pro-Palestine protest leader who immigration officials recently arrested in New York.

Beyond individual events, AIR members believe student activism plays a critical role in shaping social movements.

“Advocacy on campus is such an important thing to get involved in,” a member said. “If you’re passionate about something and you have the ability to mobilize, you should make that happen. Students are the heart of change.”

Acknowledging the impact of constant negative news and uncertainty, AIR views hope as an active pursuit. Through informing students of their rights and encouraging meaningful discussions, AIR wants to ensure that advocacy remains a practical and tangible goal, not just an abstract concept.

“At the end of the day, there are still so many immigration wins nationwide, worldwide,” a member reflected. “Even though you don’t see them, they’re there, and it starts on an individual and community basis.”

World Relief Wisconsin has resettled 2,000 refugees across the state,

but new executive

action from the federal government threatens their future and the clients

By John Ernst SENIOR STAFF WRITER

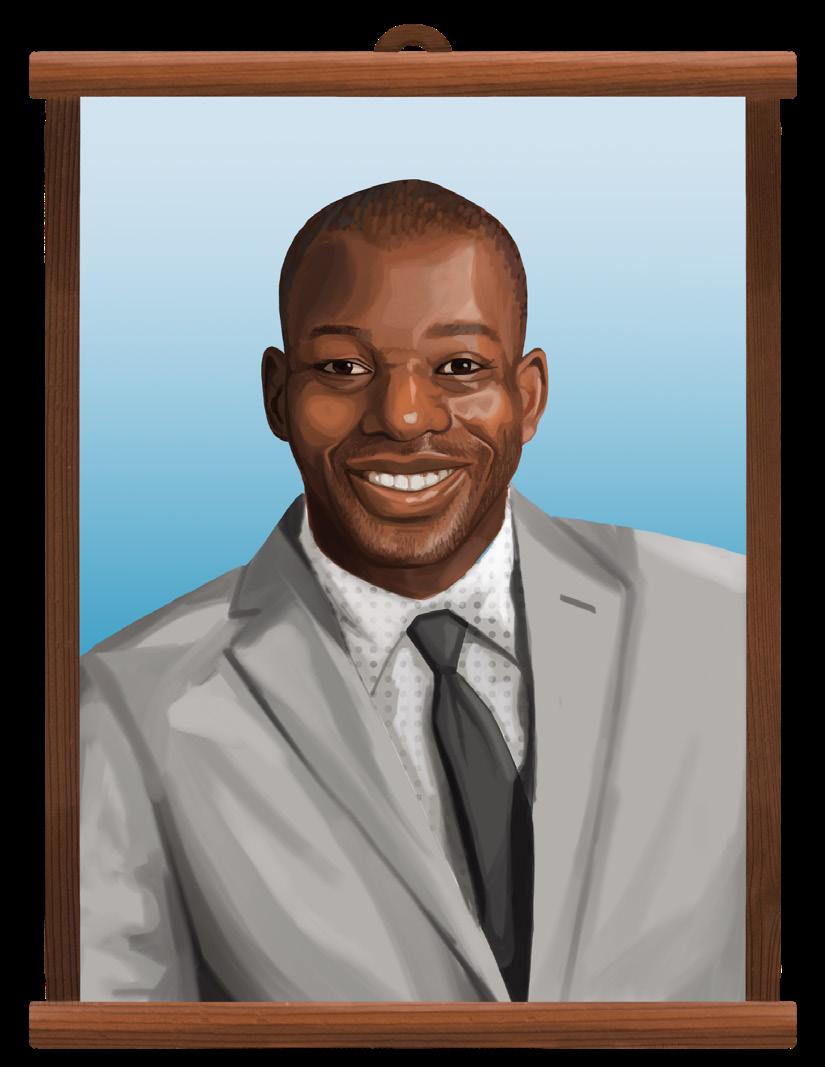

Fleeing civil war in Sudan, Deng Lual spent nine years in a refugee camp in northwest Kenya. He’s one of the thousands of Lost Boys of Sudan, young refugees who fled the war-torn African nation throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2001, Lual resettled in Houston, Texas, with the help of the Greater Houston YMCA. He became a United States citizen six years later and today is a caseworker with World Relief in Wisconsin helping refugees like himself resettle into their new homes.

But on April 15, Lual will be out of a job after an executive order from President Donald Trump earlier this year suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions program, cutting funding for Lual’s nonprofit.

World Relief is a global Christian humanitarian organization. It has operated out of Appleton, Wisconsin, since 2012, resettling more than 2,000 refugees across the state. Now, it is scrambling under Trump’s order.

“The biggest, most abrupt change is that with the reception and placement program being paused, we have no arrivals coming,” World Relief Wisconsin’s Regional Director Gail Cornelius told The Daily Cardinal. Federal funding has also been halted, forcing the organization to remodel their funding to more private sources and make difficult staffing decisions, according to Cornelius.

Those difficult staffing decisions include furloughing caseworkers like Lual.

On Jan. 31, just weeks after Trump’s inauguration, Lual and a few other WRW employees were furloughed but were brought back by the county government, according to WRW’s Access Benefits and Connections Manager Marlo Fischer. Fischer, who was laid off alongside Lual, said they were hired back on an eight-week contract to help families who had been resettled in the fall.

When the case workers were saying their goodbyes at the end of January, the clients were like, ‘What does that mean for me? How do I survive? You just brought me here to leave me.’

- Marlo Fischer WRW Access Benefits and Connection Manager

But those layoffs sparked uncertainty among refugees who were seemingly deserted by their caseworkers.

“When the case workers were saying their goodbyes at the end of January, the clients were like, ‘What does that mean for me? How do I survive? You just brought me here to leave me,’” Fischer said. “There were just

so many emotions with the clients, but it was amazing to be able to walk back in a couple of weeks later and be like, ‘okay, we’re here.’”

Fischer and Lual’s eightweek contract will expire on April 15, and they said more WRW employees will face

the same fate at the end of the month. In the meantime, Lual is preparing his clients for when his contract expires. As soon as he got back, he began meeting with families, focusing on familiarizing them with public transportation networks and connecting them to other community resources, like medical offices and FoodShare.

“A main priority is to give them [bus training] to show them where they can go,” Lual said. “I can’t be able to do everything for them when I’m gone, they’ll have to figure it out themselves.”

For caseworkers whose contracts will run out in April, emotions have elevated.

“[Lual] and I aren’t here much

longer and it’s been an amazing journey,” she said. “I just wish I could stay.”

‘A lot of fear and uncertainty’

WRW has three offices across the state, recently opening in Eau Claire to complement their Appleton and Oshkosh locations. They’ve served Congolese, Afghan and Burmese refugees, and recently, refugees from Ukraine, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

In addition to acclimating refugees to basic parts of Wisconsin life, Cornelius noted the importance of building a support system into the framework of their new lives — employment, job interviews and transportation are frequent areas refugees are confronted with challenges that differ from what they might experience at their former home.

“Many of the folks and the families that we work with come here with a very high level of education, with a very long job history, with kids that have been enrolled in schools. It’s not that they’re doing it for the first time, it’s that it’s entirely different [from] any context that they’ve ever seen or experienced before,” Cornelius said.

While WRW hasn’t received any new refugees since Trump took office in January, there has been an influx of families they’ve worked with in the past coming back with questions about their future.

“There’s just a lot of fear and uncertainty in the immigrant community right now, [and] people aren’t sure what their status

means,” Cornelius said. “We’ve had a lot more contact with the families that we haven’t worked with a lot over the past year or two. Now they’re coming back to us and saying, ‘Are we safe here? Are we okay? Do we need to make a plan for leaving?’”

One of the hardest parts of functioning in this new environment, she said, is the lack of assurance Cornelius and her coworkers are able to provide to families they’re working with.

“To feel like we’re in an environment now where we can’t really be experts anymore just because the ground is shifting under us so quickly, it’s requiring us to be resourceful and creative,” Cornelius said. “But it also changes the level of service or the level of knowledge that we’re able to provide for clients and families.”

One of the ways WRW is being creative is switching their funding to private sources. Funds have come from churches, foundations and other individuals, allowing the organization to continue to

they help.

function after federal funding was cut off. In a blog post the organization published in mid-February, they announced that they had received more than $300,000 in donations since mid-January.

While many Wisconsin communities have volunteered with WRW and partnered with the organization, WRW has also met resistance, notably in Eau Claire last year. Billboards sprung up sporting misinformation about how the refugees — who were vetted and invited by the federal government — arrived in the country.

However, Cornelius said what people see on the news might not actually represent the wider view of those in the community.

“We’ve had more volunteers in Eau Claire than we have in any of our other sites. We have found our communities to be very welcoming.” she said. “One of the great challenges that we have right now with immigration as a whole being so politicized is that people don’t understand the refugee resettlement program. They don’t necessarily understand who a refugee [is] and where [they are] coming from.”

Before Lual was resettled in the U.S., he experienced a rigorous process including background checks, fingerprinting and interviewing. Lual had to wait nine years in Kenya, and he said he still has schoolmates at Kakuma Refugee Camp awaiting resettlement.

“

Welcoming refugees is not only a humanitarian response . . . It is also a benefit to the community to welcome these families.

- Gail Cornelius, WRW Regional Director

“[Critics] don’t understand that [refugees] are safe. They’re not coming here to steal your jobs,” Fischer said. “They’re coming to literally save their families lives and hopefully start a new life here.”

As a Christian organization, Cornelius noted the importance of “loving your neighbor.” The best way for communities in Wisconsin to understand WRW’s work is to interact with the families and get to know them, she said.

Cornelius hopes that Wisconsin communities will continue to understand the importance of WRW and the work they do, in addition to the benefits refugees can bring to a community, whether it be economic impact, workplace development or cultural difference.

“Just understanding the value is something we’re emphasizing in this current climate and helping people to really see why this program has a positive impact and why welcoming refugees is not only a humanitarian response,” she said. “It is also a benefit to the community to welcome these families.”

By Bryna Goeking ARTS EDITOR

Despite their large ethnic presence in Wisconsin, German immigrants faced prejudice and discrimination in the upper Midwest in the mid19th and early 20th centuries. From removing Beethoven and Bach from concert programs, banning German textbooks and renaming Sauerkraut as “liberty cabbage,” anti-German hysteria grew from cultural intolerance to lynching.

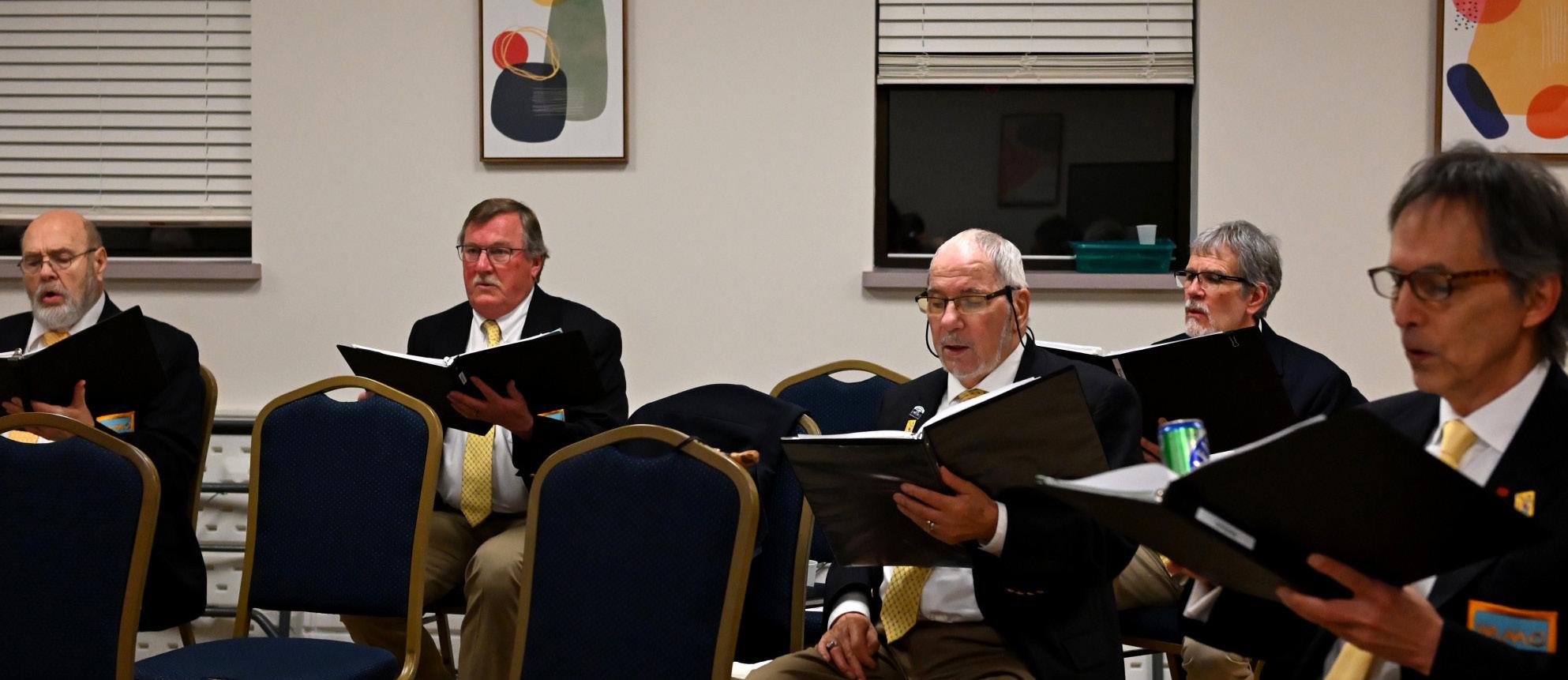

In 1852, 12 German immigrants founded Madison Maennerchor, a men’s chorus inspired by the tradition of German men stopping at local bars after work to sing four-part harmonies. The choir is currently the second-oldest German men’s chorus in the United States. Member Alan Shepard said each member has two of three criteria: an interest in German culture, liking to sing or being with people and having a good time.

“You need someone who’s got the drive and the enthusiasm, who likes the camaraderie — the camaraderie can offset the lack of musical knowledge,” Shepard said.

Nowadays, German culture is a widely accepted part of Wisconsin culture — Oktoberfest, beer and brats define the Badger State as much as they do the European country. Today, the Madison Maennerchor represents a beacon for not only the continuation of immigrant culture through arts-based organizations, but hope that prejudice toward immigrant communities may pass as immigrants become more accepted in the “melting pot” of the U.S.

Arts organizations can offer a specialized way to continue immigrant culture, engaging in community building, language diffusion and cultural preservation beyond first-generation immigrants. Without this group, it’s likely that some German songs would be largely forgotten in Wisconsin.

“It really speaks to how much the arts, not just music, play a role in culture. Coming to a new country and being able to hear and sing the same songs you grew up with — I imagine — must have made the process of getting a new home at least a little more comfortable,” said music director Garrett Debbink. “Then mix in the community-building power of making music with other people, and you have the makings of a great way for a community to stay connected in a new place.”

Current Madison Maennerchor

bass Fred Berger came to the U.S. from Germany at 13 years old in 1955 but didn’t join the choir until the 1990s after running into a few members at Essen Haus. At that point, about 16 members were German natives, a number that’s decreased to six today.

Klaus Bodenstein, a tenor who has been singing with the group since 1966, echoed this sentiment.

“When I started here, we had mostly Germans. Nobody’s coming over anymore, so we are glad to have the Americans join us,” Bodenstein said.

Bodenstein remains loyal to the group because of the friendships he’s formed. Across nearly six decades of involvement, he said the biggest change he’s seen with the group is the diversification of song origin and member ethnicity.

Without being able to rely on waves of German immigrants anymore, the Madison Maennerchor has focused its efforts on recruitment and has begun incorporating music from other cultures and continents, becoming a true American melting pot of music. The group is purposeful to not exclude any interested singer based on ethnicity — there is no requirement to be German or of German descent, although many of its members are.

Three years ago, the choir welcomed their first woman.

Tenor and social chair

Tim Hughes joined Madison Maennerchor after moving from Milwaukee in 1986. The chorus he sang with there later disbanded due to members aging out without enough new interest from the community, a common ending to groups like this. A few years into his involvement with the choir, Hughes found out his great-grandfather had been a member in the 1930s — a shining example of the choir’s long lasting legacy in the Madison area.

Hughes majored in German in college and continues singing to maintain his knowledge of the language and the culture. The largest change he’s noted across his tenure with the group is the growing share of ethnicities, as the group becomes more “Americanized,” he said.

Madison Maennerchor has also diversified its repertoire from Germanonly songs to songs in English, SerboCroatian, Italian, Spanish Latin and, recently, Japanese.

“We try to mix it up a little bit so we’re not always singing the same songs all the time,” said president

By Lillian Mihelich STAFF WRITER

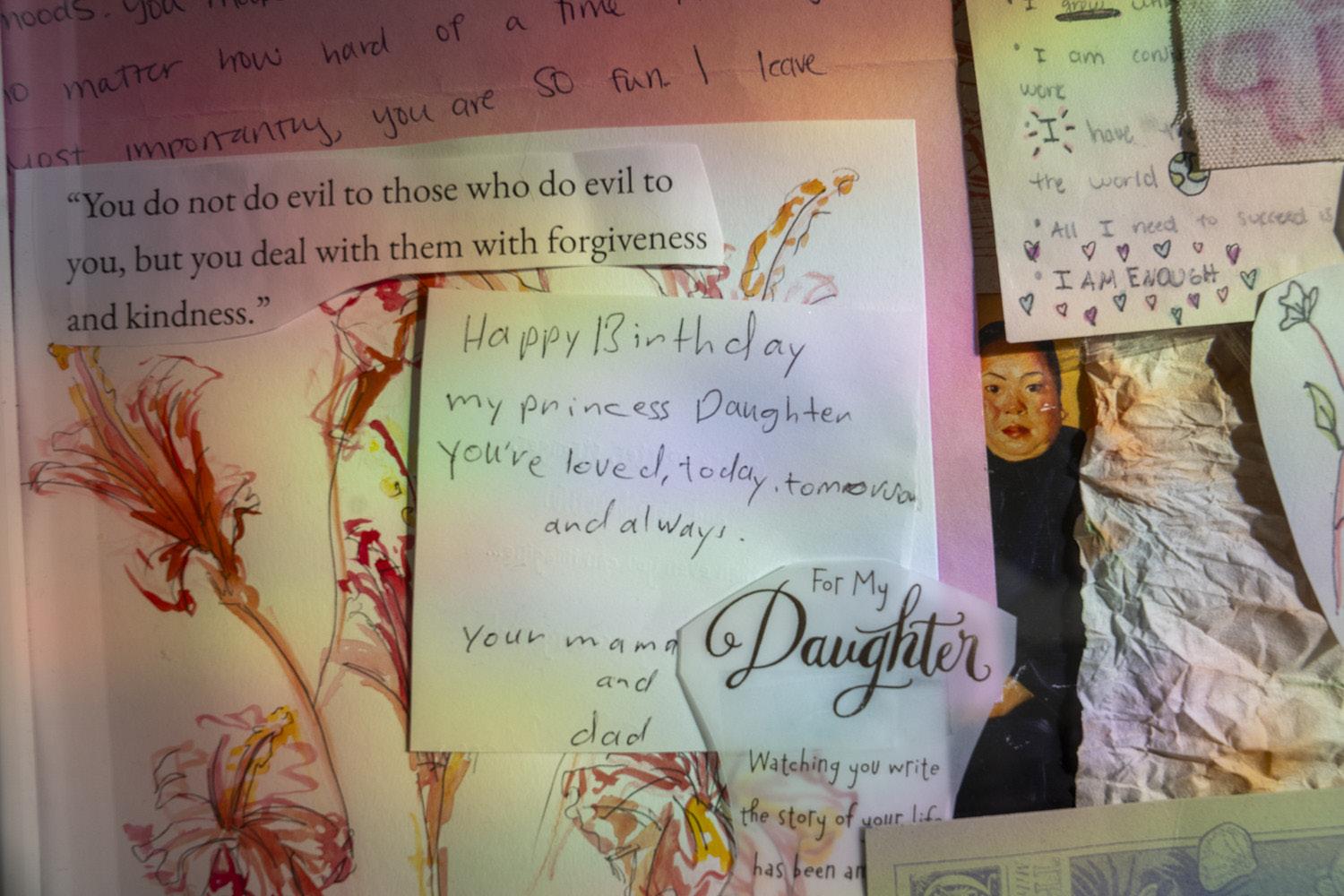

“Grabando Historias,” an exhibition by Christie Tirado, made its debut March 10 at Madison’s Tandem Press art gallery. Through portraiture and the intensive practice of printing, Tirado depicts what is present, what is erased and what is preserved in narratives surrounding immigrant, migrant, familial and agricultural stories in America.

her one-month artist-in-residency program in Veracruz, Mexico. As her grandfather plowed the Earth and she followed behind, dropping corn beads, she took a photo of him, which became the basis of a lithograph. In carving her artwork, she found a connection between her artwork and her passion for sharing untold stories.

Joe Johnson.

But traditional German songs still drive the essence of the choir, especially to its older members. Debbink jokes that some members of the group have been singing the traditional songs longer than he’s been alive.

“These are the songs that people would have been singing around the house and would have been taught at school,” Debbink said. “There really isn’t a perfect comparison today as culture and technology have changed the conditions so much, but at the time, everyone knew these songs. Many of our older singers still sing these songs by heart.”

Members of the Madison Maennerchor remain optimistic about the group’s future. The group works to continue its goal of perpetuation of choral music, both German and American, German culture and Gemütlichkeit — loosely translating to geniality, enjoying beer and German food, music, and dance with friends, exhibiting humor and emotions and being merry and easygoing while still maintaining order and good-naturedness.

Gemütlichkeit is maintained after rehearsal each week during social hour, allowing the singers to bond beyond music alone. It’s this connection that keeps members together and the German culture alive in the heart of Wisconsin beyond firstgeneration immigrants.

“German culture survives somewhat. It’s diminishing, but we’re surviving, as long as we can,” Berger said.

Debbink is cautious to respect the balance of honoring the choir’s traditions while evolving a niche organization to stay afloat and continue its legacy. Thankfully, he has the group’s Gemütlichkeit to rely on.

“At the end of the day, getting together with other people and engaging in food, drinks and musicmaking, in my opinion, will always have an appeal when done correctly,” he said.

Across its 170-year history, Madison Maennerchor has developed its own culture and traditions. From annual cemetery visits to past members, singing “Wiedersehen” — translating to “until we see you again” — at the end of each rehearsal and weekly social hour, the group has become a melting pot to celebrate cultural diversity, supporting the sentiment that almost everyone in the U.S. is an immigrant.

This exhibition celebrates stories untold and invites us to think: as Americans, how does our collective understanding of migration omit the realities of family life, and how do we rely on migrant support in our dayto-day life? These questions come to life through Tirado’s portraits, lithographs intaglio and relief linoleum reduction prints.

“Art has the power to tell the stories that history books often omit. It provides personal, visual and emotional connection to heritage whether through symbolism or portraiture or process,” Tirado told The Daily Cardinal.

Tirado is a bicultural Mexican American interdisciplinary artist and K-12 educator. After working as a teacher for eight years, Tirado is currently a second-year University of Wisconsin-Madison Master of Fine Arts Candidate and graduate research scholar.

Tirado’s work centers on labor-related migration, Mexican migration and interconnected cultural and societal narratives. As she carves, layers and removes the structural components of her printed artwork, she contemplates how this mirrors the realities of stories that go unnoticed in America.

Immigrants and migrant workers are fundamental in maintaining America’s agricultural industries, and foreign workers ensure our food supply is sustained by disproportionate numbers. Still, immigrant and migrant labor goes overlooked due to stigma, falsehoods and dehumanization.

“Historically, the United States has relied on a lot of immigrant labor work, whether it’s for railroad construction, agriculture or other industries. The foundation of this nation was built on the backs of immigrants. Yet their contributions to this nation are always overlooked,” said Tirado.

In this exhibition, we see these stories peeled back. They reveal family lineage, labor and love.

With “grabando,” meaning engrave or record, and “historias,” referring to both stories and histories, Tirado literally carves the tales of her family and workers into her abundant prints while figuratively making note of how these narratives are often erased.

Tirado shared insight into a moment shared with her grandfather before embarking on

“Just as my grandfather labored over the land, I labored over the stone, and at the end of the residency, I had to erase that image, so I had to regrain the stone again with the levigator, the grit and the water, until the image slowly disappeared,” Tirado said. “This longing to capture and hold onto these moments led me to create this work that oftentimes goes recorded or unnoticed.”

Viewers will find symbols, motifs and metaphors as well as portraits of Tirado’s family within “Grabando Historias.” Symbols include Mexican cactuses and agaves. The butterfly in her self-portrait represents migration, she said. These symbols tie to her national roots, bringing light to the importance of national identity.

The Story, “Las Manos de mi Padre,” is an extension of the familial connections between Tirado, her father and her artwork. This piece, on her website and supplementing her artwork, was written by Tirado to capture a specific moment in time. Tirado shared that through her father’s hands, who have held jobs and roles as a father and worker and peeled back a pomegranate, she illuminated his experience as an immigrant living out American life.

Tirado previously worked in the Yakima Valley as an educator in Washington, where 49.1% of the agricultural workforce is composed of immigrants, 19.8% of its labor force is foreign-born and 32.8% of STEM workers are immigrants in the state, according to the American Immigration Council.

In the Union Gap School District of Yakima, she worked in an agriculture community of roughly 50% Latine and Hispanic residents, according to Tirado, who became increasingly aware of the gaps in visibility that the labor contributions of migrant and immigrant communities faced.

“This invisibility was something that I had witnessed growing up as well being the daughter of Mexican immigrants, and as a response, I began creating prints that rendered these communities visible, honoring and celebrating their backgrounds,” said Tirado, whose family’s own persistence and resilience is made present in her work.

“As artists and as journalists we can amplify these stories by documenting and archiving them and incorporating them into educational spaces,” said Tirado.

“Grabando Historias” remains on display at the Tandem Press gallery on 1743 Commercial Avenue until April 4.

Jessica Mederson left Texas for Madison in part due to climate change. More may join her as weather across the U.S. becomes more extreme, experts said.

By Sonia Bendre STAFF WRITER

Madison resident Jessica Mederson said she remembered nights in Dallas, Texas, when temperatures didn’t drop below 90 degrees.

Many parts of Dallas are classified as urban heat islands, places where a combination of natural warm weather and concrete sprawl can send temperatures skyrocketing. Urban heat islands in Dallas can reach 10 degrees higher than other areas. Due to climate change, the mean temperature in Dallas is expected to increase by five degrees by 2050.

Mederson, who moved to Madison in 2012, is in a self-classified group of “climate migrants” — people for whom climate shapes their decision to leave their home. In a world where populous coastal states like Florida and California face drastically increased rates of climate disasters accompanied by spiking insurance costs, the Midwest begins to look less like flyover country and more like a destination location in its own right, experts have said. Wisconsin is no exception.

“Dallas is like one big paved parking lot at the bottom of the Great Plains,” Mederson told The Daily Cardinal. “Not only was it hot, but the heat would radiate up from all these black parking lots. The year we left, because it was so hot and dry, there were wildfires that were spreading through central Texas and encroaching on the outskirts of Austin as we left.”

Mederson, a practicing attorney, spent three years in Dallas

before moving to Austin, which she described as slightly more temperate but still “far too hot.” Finally, she moved to Madison, calling herself a “partial climate migrant” to the area, as she also made the move to be closer to family.

Though about a third of U.S. adults said that if they were to move in the next year, it would be due to climate change, most people who relocate due to climate also move because of other factors, according to Sumudu Atapattu, director of the Global Legal Studies Center and professor at University of Wisconsin Law School.

“

There were wildfires that were spreading through central Texas and encroaching on the outskirts of Austin as we left.

- Jessica Menderson, climate migrant

Steph Tai, UW Law School professor and Associate Dean for faculty in Environmental Affairs at the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, told the Cardinal the Midwest may see more flooding due to greater precipitation caused by climate change, but its effects will be less severe than in warmer regions where rising sea levels threaten coastlines.

“We’re in a cooler climate overall, so warming from our cooler climate won’t be as horrible as, for example, warming from the climate of Arizona,” Tai said.

Even when climate disasters don’t drive people out of their communities directly, climate change can exact an emotional toll for people facing frequent close calls as well. Evacuations due to wildfire warnings in California or hurricanes in Southern coastal states could become regular events for residing families, and if power systems fail in some Southern cities, heatstroke fatalities will occur.

When Mederson’s home HVAC system broke down in Dallas, for example, she described feeling intensely worried that her young children would overheat. Southern infrastructure is also not equipped to handle sudden cold snaps, another result of climate change.

“The houses are not insulated like they are up here, and you don’t have the jackets and the cold weather gear,” Mederson said. “I felt much more vulnerable down there in the winter because when it did get cold, Texas was not prepared for that at all.”

What is being done?

A number of factors influence how counties and cities should best accommodate and integrate climate migrants, including but not limited to the migrants’ native languages, the climates they are immigrating from and the scale of the migration itself, which might necessitate school or infrastructure expansion, according to Atapattu.

The Wisconsin Legislature recently introduced a bill in the

assembly that, if passed, would allot a tax credit to those relocating to the state from the Los Angeles wildfires earlier this year or Hurricane Helene in 2024.

Though anecdotal evidence exists to show that U.S. residents, especially mobile young professionals, are likely to consider climate change when deciding where to settle, destination locations are still highly dependent on kin networks. Mederson, who runs a podcast centered around climate change, said she hopes people will be incentivized to move to places with the infrastructure to support them as climate change worsens.

After Mederson moved to Madison, she joined the Wisconsin Initiative for Climate Change Impacts (WICCI), described on its website as a “statewide collaboration of scientists and stakeholders… to evaluate climate change impacts on Wisconsin and foster solutions.” Mederson is a member of two WICCI committees discussing how to help local communities prepare for climate change and climate migration.

“While there’s not a ton of data yet, it’s obvious that there are going to be more people migrating up here as climate crises become worse in more vulnerable parts of the nation… I’m very happy I moved up here, but I think [we need] resources for people who can’t move with so much planning and intention,” Mederson said.

Although Mederson had the financial resources to move successfully from Texas to

Wisconsin in around six months, she recognized that others might not have the opportunity to do the same.

“Often the people who have more money, while they’re still suffering, are suffering less than people with fewer resources,” Mederson said. “What can we do to support both individuals and communities with less resources to find a way to move that they both can financially afford to do and that doesn’t destroy their entire sense of community, of home?”

New administration changes demonstrate a ‘disregard for the rule of law’

Recent action by the Trump administration froze current infrastructure standards in place, meaning that buildings will no longer have to meet as stringent of climate resiliency requirements in order to receive federal funding.

Tai, whose research specializes in the consideration of scientific evidence in developing standards, said that this action might cause new developments to be less resilient to climate change, negatively affecting the housing market, office infrastructure and roads’ resistance to climate change effects such as flooding.

- Jessica Menderson, climate migrant “

It’s obvious that there are going to be more people migrating up here as climate crises become worse in more vulnerable parts of the nation.

“To me, this new FEMA development is horrific, because it’s basically saying we’re not going to take into account the scientific information,” Tai said. “It puts the onus on the developer, if they want to have a resilient building, to develop their own. That’s a lot of resources they might not have. Rather than putting federal resources into it, [President Donald Trump’s administration] is basically making it a more free-forall kind of environment, and developers have incentives to cut costs on their buildings.”

Atapattu agreed that the new administration’s laws, both climate-related and refugee-related, pose humanitarian problems that will be difficult to repair.

“We are talking of an unprecedented situation where there seems to be a disregard for the rule of law, for the international obligations, frameworks and institutions in place,” Atapattu said. “So it’s going to be a very sad situation for refugees and people who are fleeing violence, fleeing disasters.”

Farley Center is one of many organizations home to Latin American and Hmong farmers who associate the variety of vegetables with their culture.

By John Ernst

Over 40 years ago, Shedd Farley’s parents, Linda and Gene Farley, moved to Verona, Wisconsin from Colorado and settled on a 108-acre plot of land that today is known as the Linda and Farley Center for Peace, Justice and Sustainability.

The plot is home to natural prairies, a green cemetery, nature preserves and a farm incubator system. The farms at the Farley Center,

“My dad wanted to focus on hardworking immigrants who come to this country not for any nefarious purposes, but they want to come and earn a living,” Farley told The Daily Cardinal. “That’s what we allow them to do.”

Farley Center is one of many organizations partnering with immigrant farmers in the Madison area. Rooted, Groundswell Conservancy and the University of WisconsinMadison Extension Program also work toward finding plots of land for immigrant farmers.

Hmong farmers often learn how to farm in tropical climates with nutrient poor soils, fast nutrient cycling and quick primary production, according to Ventura. Implementing a slash-andburn style of agriculture — where farmers grow intensively for a few seasons before letting the land rest and returning years later — might work perfectly in the tropics, but is less effective in Wisconsin.

however, don’t grow typical Wisconsin row crops such as corn or soy, instead opting for a wider variety of vegetables, many of which are associated with the culture of the farmer planting them. Farley Center is home to both Latin American and Hmong farmers as well as Russian and Indian immigrant farmers.

“[Immigrant farmers] absolutely meet our mission for equitable treatment of everybody,” said Shedd Farley, the regional director at Farley Center, who also serves as natural cemetery sanctuary coordinator. Farley noted that when his parents arrived in Verona, the first farmers they offered land to were Mexican and Hmong immigrants. After 40 years, Farley Center is still working toward this mission.

Martin Ventura, the Urban Agriculture and Community Gardens Specialist at UW-Madison Extension, manages and maintains farms in the Milwaukee area, some of which are farmed by immigrants, particularly in the Hmong community. UWExtension, Ventura said, had a former partnership with the Hmong American Friendship Association to establish a Hmong heritage garden plot, allowing local communities to farm.

Oftentimes, these informal arrangements are handled by local churches, who serve as liaisons between immigrant farmers and organizations like UW-Extension, allowing trusted entities from both sides to facilitate conversations about finding farming land. Where UW-Extension can aid Hmong farmers, Ventura said, is aiding in the cultivation process, when farmers find themselves in a vastly different climate.

“Within [UW]-Extension, there has been a huge amount of work done to support conversations in which we’re coming into better alignment with the needs of Hmong growers in particular,” Ventura said.

“Here in North America, our climate is really different and our soils are fairly different, so the stewardship practices that we need to keep our land productive are also really different,” Ventura said. “One of the harder things that [UW]-Extension has been trying to do is connect with Hmong growers to adapt those instincts which were really well suited to tropical southeast Asia and say ‘certain elements of this practice are not as applicable in an environment like Wisconsin’s.’”

This adaptation process might modify practices to ensure long-term soil health, managing pests and diseases, while simultaneously supporting the economic bottom line and long-term environmental sustainability, according to Ventura.

Hmong farmers, in particular, are important facets of Wisconsin’s network of farmers’ markets.

“In our local ecosystem, our farmers’ markets would be depauperate if not for the presence of growers from southeast Asia,” Ventura said. “One thing we are certain of is that we need these people working the land, contributing to our food security, building their businesses and sharing their expertise and food ways with the rest of North America. We just know they’re absolutely critical components within our food system.”

On a larger scale, immigrant farmers also work to uphold Wisconsin’s expansive dairy farms. An April 2023 survey by the School for Workers at UW-Madison estimated that over 10,000 undocumented immigrant workers perform 70% of the labor on Wisconsin dairy farms.

“Our dairy farms would be sunk without immigrant labor,” Ventura. “There are several states from Mexico which provide the overwhelming majority of our dairy workforce in the state. That’s common knowledge.”

With the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants, many farms and farmers have been called into uncertainty. Even at a much smaller scale, Farley hopes the farmers he works with will continue to feel safe on Farley Center land. So far, he hasn’t heard of any of his farmers halting their work.

Despite the uncertainty, Farley and Ventura persist with their work in supporting the immigrant farming community.

“It’s important that people grow culturally significant foods because people’s culture is what defines them, and people’s food ways are absolutely critical to identity,” Ventura said. “Giving people the ability to practice agriculture in a way that makes sense to them based on both their needs for culturally specific and appropriate foods and [culturally bound] ethics of earth care…I think is pretty important.”

Food is more than a meal — it’s a bridge to home, culture and community, offering a taste of connection sometimes continents away.

For two local businesses in Madison, it’s become a way for two immigrant families to share a small piece of their homeland with the world.

How food becomes ‘the great connector’

The first thing Tamaki did when I entered the store was offer me a drink and mochi — free of charge.

“You don’t even have to interview me,” Tamaki said. “Just take some time off, relax.”

This welcoming atmosphere is exactly how Tamaki has kept Oriental Shop running since 1979. Her inviting presence and willingness to chat draws in new customers and has kept the old ones returning for over 40 years.

Japanese native Tamaki first came to Madison in the 1970s looking for a business to run, but what she found instead was a husband. Kuang immigrated from Taiwan to the United States to attend college at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but after meeting Tamaki, he dropped out of his mathematics program to run a specialty Japanese food store with his now-wife.

“This store is like a galaxy, and everything on the shelves is a star in the night sky,” Kuang said.

At Oriental Shop, 1029 South Park St., customers can find everything from handmade plates to cuts of sushi-grade

by Tamaki and her husband.

“It’s not just for Japanese [people] but for everyone who’s gone to Japan, who likes Japanese food. It’s nice to have that community and food in Madison,” Tamaki said.

Oriental Shop is just one of the thousands of immigrant-owned businesses in Wisconsin. Yet in the wake of President Donald Trump’s crackdown on immigrants in the U.S., some within the Madison immigrant community feel it is being “torn apart.”

“It’s about survival,” Tamaki said. She worries “every day” about the Trump administration’s decisions but tries to keep her mind off of the news with work, using her store as a way to stay connected to the people of Madison and a distraction from politics.

Sophia Pezua, one of the four siblings who co-own the Peruvian restaurant Estacion Inka on University Avenue, said she worries about Trump’s vocal support of deportation and expanded use of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), but she and her siblings don’t let it get in the way of running their two businesses.

“If we focus too much on what’s going to happen, we take away the energy that we need for dealing with what’s happening right now,” Sophia said. “Being able to get to the end of the pay period and knowing that you have the funds to pay your employees, that’s the most rewarding feeling for us.”

First opening in 2019, Estacion Inka blends traditional Peruvian food inspired by their mother’s homecooked meals with the experiences the siblings gained after immigrating to the U.S. from Peru.

At first, being split between two countries made them feel like outsiders, belonging to neither America nor Peru. But over time, Sophia said Madison has “definitely embraced” them, transforming their sense of isolation into a deeper understanding of community — one that shapes how they run their restaurant today.

This understanding flows deeper than simply mixing cuisines on a menu. Sophia and her siblings use their experiences to create a truly welcoming atmosphere at the restaurant.

The open-air floor plan, delicious

blending through the speakers allows the Pezuas to “create a space where people can just come in and feel like they’re part of the extended family,” Sophia said. The Pezuas give Madison natives, solo travelers and immigrants alike a warm sense of familiarity, even if they might’ve never stepped foot inside before.

Nothing highlights the feeling of being a part of the Pezua family more than eating their famous Lomo Saltado, though.

Sophia said that growing up poor in their small mountain town meant meals like Lomo Saltado were few and far between, but on the rare occasions, the Pezuas’ mom made such a meal.

“The aroma of Lomo Saltado was very particular, so we knew that as soon as we opened the door, and the aroma wafted in, Mom had made us something delicious,” Sophia said.

Drawing inspiration from their mom’s version of the meal, Estacion Inka’s version of Lomo Saltado has become one of their most popular dishes, allowing the siblings to relive their precious memories every single day.

The Pezuas’ mom, who is now 84, loves visiting her children’s restaurant whenever she can and is “so proud” of what they’ve been able to accomplish.

“And we’re so proud of her too. We are where we are now because of her effort and her care while growing up,” Sophia said.

Tamaki also drew inspiration from her mom, using her love for and technical knowledge of cooking as the spark to start Oriental Shop. Eventually, Tamaki’s mom even helped open the store.

That feeling of pride, happiness and shared connection is something that the Pezuas and Tamaki both share in common, their love of food and home uniting both natives and travelers alike.

Just as Lomo Saltado gives customers a window into Sophia’s childhood home in Peru, the carefully curated shelves of Oriental Shop give Tamaki the ability to share her time in Japan with others. Both shops invite customers into their own curated galaxy — each dish, each item on a shelf, each memory of home, shining like stars in the night sky.

By Amina Haniieva STAFF WRITER

The scoreboard tells you who won, but it won’t tell you who left their home, their family and their entire world behind to represent the Wisconsin Badgers.

For freshmen Ferdinand Kloesters, from Germany, and Edouard Aubert, from Switzerland, success on the men’s tennis team isn’t just about rankings or records — it’s about adjusting to an entirely different way of playing the sport.

Kloesters and Aubert are among six players coming from outside the United States on the Wisconsin men’s tennis team. The program has become a living example of how athletes are adapting not only to college tennis, but to a new cultural and emotional framework for competing.

Tennis is a solitary pursuit in Europe. Junior athletes grow up training and traveling alone, competing not for a team, but for personal ranking and advancement. By contrast, the college system in the U.S. is built around shared goals, vocal sideline support and the idea that your win means nothing if it doesn’t serve the team, Kloesters said.

“In Europe, you play for yourself. If you’re not playing, you don’t really cheer for your teammates,” Kloesters said. “But here, even if you’re injured or on the bench, you’re expected to support the team loudly. It’s really meaningful for them.”

The shift from individual mindset to collective identity is one of the defining culture shocks many international athletes say they feel. This adjustment goes deeper than gameplay — it’s about reshaping their entire mindset. Suddenly, a sport that has always revolved around the individual becomes about shared identity, group accountability and showing up for something

bigger than yourself.

Kloesters, who arrived from Grunwald, Germany just months ago, said he remembered what set Wisconsin apart. He had already made a name for himself back home, ranking as high as No. 10 nationally in Germany and No. 2 in Bavaria. But he said the competitive environment in the U.S. is on another level.

“In Germany, you have very, very good players with very good techniques,” he told The Daily Cardinal. “But here it’s just much more competitive. I love my emotions on the court. I love more team spirit as well.”

And that team spirit drew him to Wisconsin.

“I talked to a lot of different coaches from different universities…But the talks I had with Danny [Head coach Westerman] were just the best, the most nurturing. I thought, if he would choose me, then he would probably choose players who are also good people,” Kloesters said.

That instinct paid off when he arrived on campus. While his on-court debut is still on the horizon, Kloesters said the transition off the court has already exceeded expectations. He credits this smooth start to how quickly the team embraced him during a trip to Florida after his arrival.

That early support gave him confidence that he had made the right choice, and found something deeper than just a roster spot, he said.

Kloesters isn’t alone in that feeling. Aubert had similar hesitations before joining the team.

“I didn’t know what to expect, but when you train every day with the same guys, do everything with them, you win and lose together, it brings us really close.

It’s basically the same as family,” he told the Cardinal.

This sense of closeness is built in the team’s daily routines:

Madison is one of 60 cities across theU.S.tohostahurlingand Gaelic football club.

By Molly Sheehan SPORTS EDITOR

As the festivities of the St. Patrick’s Day parade on Capitol Square came to a close in 2007, brothers Jason and John Kenney gathered on the lawn with their hurls in hand, skillfully hitting a sliotar back and forth off the wide end of the stick.

The wooden stick, known as a hurley, and the small ball, known as a sliotar, are used in the Irish sport of hurling — a sport not widely known to Americans but recognized as a national sport in Ireland.

The brothers’ back-andforth play caught the attention of Bill Jones, who recognized their equipment and expressed interest in joining them.

team dinners, bus rides and early-morning lifts, Kloesters said. But cultural integration doesn’t happen overnight. Aubert said the biggest shifts were in expectations around team dynamics.

And adaptation happens fast. Kloesters, who admits he’s now loud on the sideline, also laughed as he listed the very American habits he’s picked up.

“I started drinking more coffee. I put ice in my water now. And I learned a new word here — ‘yapping.’ I use it sometimes. Also, I’m louder now when I cheer on my teammates. That’s definitely new,” Kloesters said.

None of these things were part of his routine back home. But that’s the point. This experience is about more than just tennis — it’s about transformation.

Neither Kloesters nor Aubert had Wisconsin at the top of their list from the beginning. In fact, Aubert wasn’t even sure he wanted to come to the U.S. at all.

“It was a last-minute decision,” he admitted. “But I liked the coach. My parents wanted me to go. And I heard the campus was really nice.”

Now, despite Madison’s unforgiving wind, Aubert is glad he made the move — “except the weather is a bit cold, though.”

And while many athletes agonize over rankings, records and resumes, Kloesters said those numbers don’t even come close to the true value of this journey.

“At the end, you won’t remember the wins or the losses or what the team’s ranking is… or even what the school as an academic institution ranks,” he said. “It’s basically what people you meet and how you get along with them… people should probably put much more emphasis on that when they choose their school.”

“I understood that it was hurling, but I didn’t know any of the rules. I didn’t know anything about it. I just thought it was interesting,” Jones said.

Since that Saturday afternoon, and the first practice that they held just a week later, the Kenneys and Jones have worked tirelessly to build a group of individuals dedicated to the sport. Their club, the Hurling and Football Club of Madison, would continue to recruit players over the years.

Jones, who hadn’t picked up a hurl until he was almost 38 years old, immediately felt drawn to the sport.

“I had found the sport that I’ve been practicing my whole life for,” Jones said. “It’s a very personal experience to play the game.”

The sport may be likened to lacrosse, rugby, soccer or even football, where players battle across the field to hit the sliotar over their opponent’s crossbar and between the uprights for one point or under the crossbar, past a goalkeeper and into the goal for three points. To Jones, it’s a fast and physical game that’s “easy to pick up but difficult to master.”

“It’s a really thrilling game,” Jones said. “You put on helmets and you crash into each other, and it’s just got an opportunity to feed your competitive side.”

The game thrives in Madison among the tightknit community that expands beyond the start of a match and beyond when the players clatter in their cleats off the grass.

“Everything that happens on the field stays on the field, and that has been almost a catalyst to create meaningful relationships,” Kenney said.

By 2015, the club expanded beyond hurling to include men’s and women’s Gaelic football, a sport likened to rugby or football where two teams of 15 players compete with the

objective of kicking or punching the ball into their opponent’s goal or over the crossbar.

“It was kind of unheard of, certainly in the United States, to have a team that did both [hurling and football],” Kenney said. “I’d like to think that we were one of the first teams to really become wellversed on both sides and to welcome Gaelic football, and I think that was what really helped us grow.”

That year, the Hailstones went on to win their first Junior C championship. From there, participants flooded in. Once the team notched a win, Kenney said it became “easier to attract people.”

Since then, the club has won four more national championship titles across different grades of the United States County Board of the Gaelic Athletic Association.

Among the newcomers was recent graduate and former member of the UW-Madison women’s rugby club Abby Frisinger, who came across the Hurling and Football Club through word of mouth. Frisinger and her friend gave the club a shot and found themselves “hooked after the first practice,” she said.

Like many of the Hurling and Football Club’s members, Frisinger plays both camogie — the women’s version of hurling with similar rules — and Gaelic football. With camogie, the sport’s uniqueness attracted Frisinger.

“I’ve never really experienced it in sports I’ve played before,” Frisinger said. “You have to be really skilled to handle the hurl and the sliotar in a way that is easy to forget when you’re playing Gaelic football.”

Kenney, who even found his wife through hurling and football, said the club created a community for people to find a place to belong and connect with others interested in hurling.

The club has also greatly benefited from the experience of Irish players who grew up playing the sport and brought an understanding of the nuances to the club. From the outside, the sport appears fast and furious and frantic, but when you learn the intricacies of the passing and skill positions, it becomes apparent that it’s not simply a fast, physical and brute-force game.

The Hailstones continue to practice each week in the summer on Thursday evenings. But to many, hurling and Gaelic football are more than sports.

“It’s a great sport, but it’s also a really incredible community. And I’m really privileged to have been a part of that,” Kenney said.

By The Daily Cardinal Editorial Board