IN ACTION FAITHFUL AND IN HONOR CLEAR

Midge McPhee Bowman '51

IN ACTION FAITHFULAND IN HONOR CLEAR

A Reminiscence

Midge McPhee Bowman '51

Helen Taylor Bush

Introduction

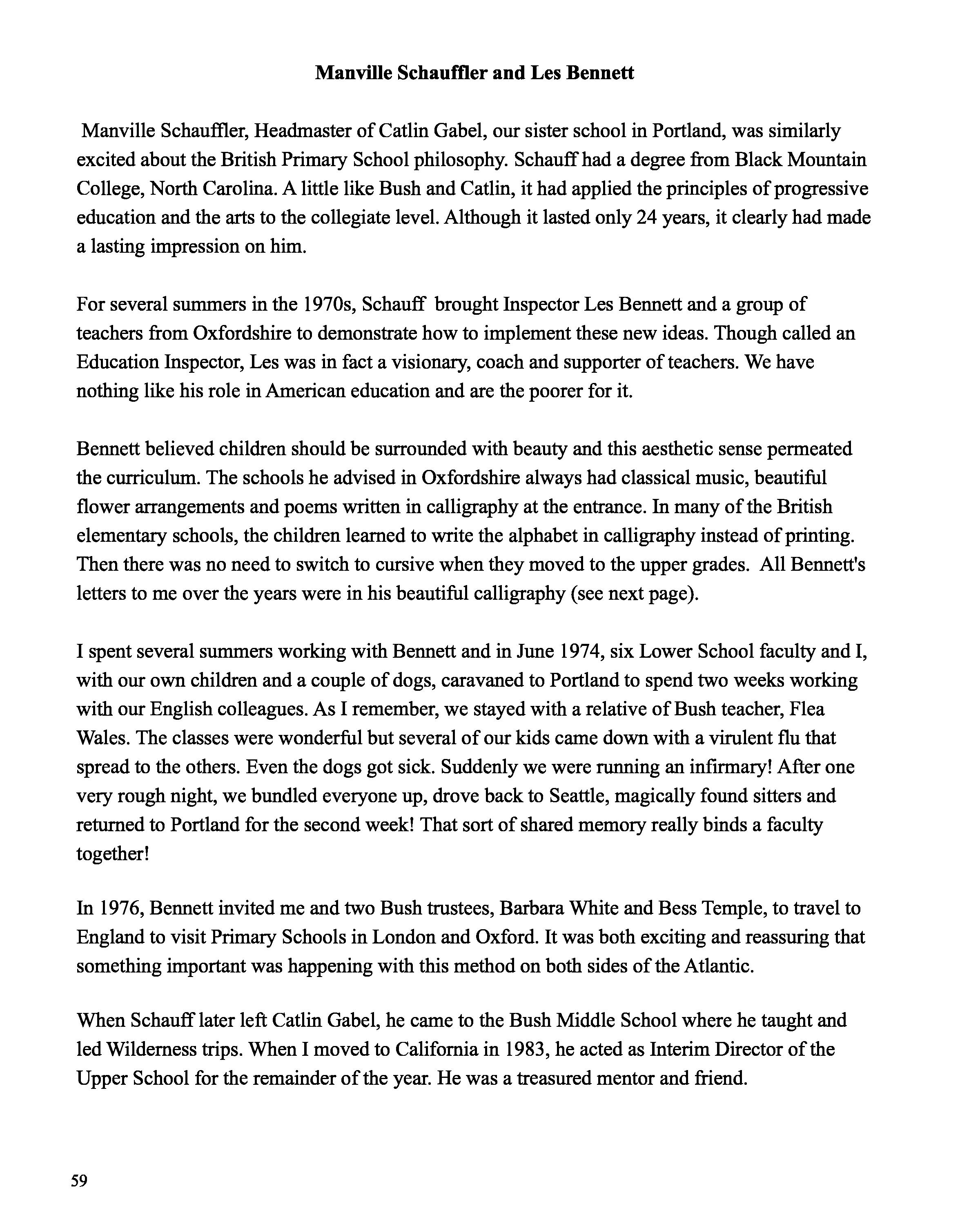

I did not intend to write this book! I was already well along in my own memoir when Tiffany Kirk, Bush Manager of Alumni and Donor Relations, invited me to join a group interviewing former faculty and alumni as part of the upcoming 2024 Centenary. I enjoyed being part of this effort and am grateful to all those who interviewed with me: Les and Nancy Larsen, Marilyn Warber Gibbs, Joan Marsh, Dee Dickinson '45, Peter Eising, Peggy Skinner and Michelle Purnell-Hepburn '75. The conversations were so valuable that I decided to include them with the "Bush years" material from my memoir in order to create a new volume which this Introduction begins. I want especially to thank Cali Vance, Bush Archivist and Centennial Coordinator, for her special support throughout the writing of this book and Carolyn Kato Bowman '79 for her expertise with all the photography. I am also grateful to Susan T. Egnor, Fifty Years-The Bush School, and Anne M. Will '68, The Bush School: The First 75 Years, for their excellent work.

My Bush story, which began at age twelve and continued as an alumna, faculty member, division head, parent of two Bush alums and ultimately Interim Head of School, is suddenly no longer solely about me and my experience. It has become a story of our growth as a community. In those early days of coeducation with John Grant and Les Larsen, our small school-while building on Helen Bush's legacy-was actually creating an enlarged and expanded vision: a new name and a new identity in the midst of challenging social issues and ground-breaking ideas in education, psychology and the arts. From my current perspective at ninety, I value even more the breadth of that curriculum and our impact on the broader community where we were brave enough to envision our small school in a larger context.

For that reason I have included documents-lectures, syllabi, meeting minutes, curriculum outlines and even some parts of the 1992-93 PNAIS evaluation-because I believe they represent groundbreaking ideas that should be preserved for historians of a future time. Although these materials may occasionally inhibit the flow of the narrative, I want to ensure that they are not lost.

The years from age five to eighteen (six of which I spent at Bush) are among the richest, most formative of our whole lives. The men and women who commit themselves to educating this age group deserve our highest gratitude and respect. Having been- at different times, at different schools-directly involved with this age range, I know that a quality education in these years positively affects the whole range of one's cognitive and emotional development.

This was certainly true in my own student experience. I remember as a sophomore sitting in Miss Haight's "Western Civ" class when she introduced Plato and Aristotle. She began with Plato's Allegory of the Cave that depicts a group of prisoners chained in a cave, unable to tum their heads away from shadow pictures thrown on the wall by the light from a large fire at the rear. What they couldn't know was that, all the time, the sun was shining outside in the real world, where it was possible to learn about truth and our responsibilities as citizens. Miss Haight did give Aristotle equal time, but Plato's vision never left me.

Today, in our current situation as a society, students are exposed to a new kind of cave wall-a screen where TV, movies, phones, and computers offer pictures, stories and information but where agreement on what constitutes consensus reality and truth is increasingly challenged. For me that means what a Bush education offers has never been more important.

A strong school never stays the same although it remains faithful to the vision of its Founder. I feel this is especially true as we celebrate our first Centenary. Percy Abram has lead Bush into its second hundred years with courage and vision that Helen Taylor Bush would applaud as do I.

In 1981, as Associate Head, I made a report on Experiential Education to the Board of Trustees since there was some question of the direction the curriculum was evolving. The closing paragraph I shared then seems equally relevant, if not more so, today:

"In the future, the educational institutions that will survive are those who have put down roots very deeply; who remain dedicated to handing down the wisdom of the past while anticipating the challenges of the future; who are not afraid to attempt the difficult task of educating the whole person; who see education as a moral responsibility in which the best of ourselves is nurtured for the sake of others. I feel strongly that Bush is such an institution and I am grateful to be a part of it."

Midge Bowman

Seattle, Washington, May 2024

Student Years 1945 - 1951

In 1945, my grandmother offered to send me to the Helen Bush School. I arrived at the front door in late August, a skinny little 12-year-old with thick glasses and a love of reading. The wooden buildings looked a little like barracks (it had been Lakeside School initially) and there was a sign with the School's name stuck rather haphazardly in the grass by the sidewalk. I remember being ushered into a small classroom (very small compared to my public school) and taking some kind of test.They told us the same day that I would be admitted and to order my school uniform: a rough dark blue tweed A-line skirt and blazer jacket with white Peter Pan blouse, from Frederick and Nelson's department store. Thus began my relationship with the Bush School. Little did I realize that it would continue throughout much of my life.

Bush was smaller and less imposing than my big brick public school with its smell of wax, construction paper and glue. It was built on a strange triangular piece of land where two streets, Harrison and Republican, almost intersected near the eastern end of the property. The School was built around a courtyard in the same triangular shape. The front entrance with the main office, classrooms and library, was dominated by a gymnasium directly behind-a reminder that this had been a boys' school. There was a "chem shack" at the western end of the courtyard and graduation was held in the center.

Parkside, the small coed elementary division, existed even then, but the main focus was "The Helen Bush School, a boarding-day school for girls in grades 7-12." Both Bush and Lakeside had boarding departments in those days.

There were three residential halls: Gracemont, initially for 7th-through! 0th-grade boarders, Taylor Hall for the older girls, and Dorothy Allen Hall with short-term lodging for elementary age children. Think of the luxury for parents to be able to board their children while they were away on trips! We had boarders from exotic places like Alaska and Montana, plus some local girls. Each day we joined with boarders in a family-style lunch at round tables in Dorothy Allen Hall. I remember our cook, Elsa Johnson, who provided a veritable feast at Thanksgiving and a festive spread of Scandinavian sweets at Christmas. We had assigned seating and sang "Noontime is here, the board is spread. Thanks be to God who gives us bread."

Mr. and Mrs. Bush ran the School, he as business manager and she as the academic head. Mrs. Bush had a low, throaty voice, quite beautiful really. She seemed uninterested in what she wore. All I remember were perennial dark blue dresses much like the one she wears in the picture by Walter Isaacs on the previous page. Mr. Bush's office at the end of the front hall, smelled of cigar smoke, spicing the otherwise female atmosphere of the place.

World War II officially ended with the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945, the same month I entered Bush. I remember our class had a field trip that autumn to view a Red Cross train fitted out as an emergency facility at the King Street Station so there were still reminders of war.

My first year courses in grade seven were English, Latin, math, history, cooking, art, music and PE. I don't remember having any science until high school. I loved the academic work, did poorly in gym, couldn't figure out why we made white sauce in cooking and took private piano lessons with Dorothea Hopper Jackson during the school day.

At my young age, I didn't realize Helen Taylor Bush was an educational pioneer, a student of John Dewey and experiential education. She believed in global travel, math and science for women, and the importance of the arts. She also believed that students should be apprentices and work with actual artists, writers, dancers, scientists, linguists, poets, actors, athletes. This was before the advent of Science Education or Art Education where education majors in college supposedly learned how to "teach" subjects about which they had little real life experience. At Bush we worked with practicing professionals and absorbed, at least in small ways, their passion for their discipline. During my high school years, I studied with painters, Emily Morse and Windsor Utley, musician and composer, Karla Kantner, dancer, Eleanor King ( a student of Martha Graham, later winning a Fulbright to study dance in Japan), and drama with alumna, Dee Dickinson '45.

A sensitivity to beauty permeated the School. Mrs. Curtis, the head gardener (and mother of my classmate, Sarah) rented part of her home to the famous sculptor, Archipenko, and kept the School building full of beautiful flower arrangements. She once brought a small blossoming pear tree and set it up in the gym to grace our spring Fine Arts program. (It had been cut down as part of a landscaping project.)

School traditions had, for me, the quality of communal rituals. We opened each school year with Convocation at Epiphany Church in Denny Blaine and ended there with Baccalaureate. It was a

beautiful, tiny English Tudor-style church and my first contact with this religion. I loved Elmer Christy, the rector, and it is somehow congruent that I ended up being baptized as an adult at Epiphany and becoming closely involved with the Episcopal Church.

The school's three Ideals: Truth, Beauty, and Purpose, were always kept before us. During my six years as a student, I won office several times. Every time we were inducted, we had to give a short speech on one of the three Ideals. Bartlett's Familiar Quotations indeed became "familiar" to me. I believe the sculpture created by Liz Gall'38 to symbolize the Ideals still stands in the courtyard.

My first Bush Christmas program made an indelible impression. The gym had been transformed into a glorious medieval manor with cellophane "stained glass" windows and the smell of evergreen boughs and garlands everywhere. The whole School participated. As a seventh grader, my part was in a dance choreographed by Miss King. The beauty of the pageantry was impressive to my small person, but even more important was the awe of seeing all of us: faculty, students and parents sharing this experience. It gave me a new sense of family and of how intertwined our lives had become. I did not know then that, ultimately, I would be connected with all the first four Heads ofBush.

In 1948, my ninth grade year, Commencement was held in the gym and we realized the seriousness of Mrs. Bush's health as she was carried onto the stage. Ana Kinkaid, a Bush parent volunteer at the time, wrote the following reminiscence, later reprinted in the 2007 Bush Experience magazine:

THE LAST SPEECH: HELEN BUSH

It was a cold and rainy that day in June of 1948. Helen Bush for the first time was not going to be supervising the graduation ceremonies. A diagnosis of advanced cancer had forced her retirement the year before from the school that she had founded in 1924. Yet with great effort, she returned to give one last address to the students, parents, and faculty.

Many of her friends and colleagues thought she might be too ill to attend the ceremony, much less have the strength to give the keynote speech. Yet there she was. Too weak to walk in the graduation procession, she had to be carried into the gym and rested on a chaise lounge that was placed on the side of the stage. There she lay and waited for the students and staff to enter.

But if any in the audience were concerned about her strength, they need not have worried, for this was a remarkable woman. In 1902, when few women even attended college, she graduated from the University of Illinois, Urbana with Phi Beta Kappa honors. She studied mathematics, history, science, rhetoric, French and literature, and played on the University's basketball team. Upon graduation, she taught mathematics, traveled in Europe, married and started a family.

Like progressive educator John Dewey, Helen Bush maintained a deep and unending belief in the ability of children to learn and grow. When her husband John Bush lost his hearing, she decided to put her beliefs to the test and opened a school- a school dedicated to the joy of learning.

Twenty-four years later, the school had more students and teachers and was benefiting from new buildings and better books than when it opened. Many wondered what this woman would say at the graduation ceremony. Because, after so many years of success, wasn't this, well, the end?

Mrs. Bush waited as others spoke, then gathered her strength and went slowly to the podium. At first her voice was shaky. But as she continued, her strength returned. She spoke without notes of what had motivated her through the years-an unfailing belief in the great ability of children.

Mary "Sis" Pease remembered, "She believed we could do anything. She opened a world of possibilities, a world without limits to us. Sometimes we failed, but we were always empowered to try. That meant everything to us."

As Mrs. Bush continued to speak, many people there realized they were not listening to a farewell speech but an impassioned plea to believe in education as a beginning, a starting point from which to discover the wonder of life. Students who were present that day recall, "It just poured out of her. I remember being inspired. I can still hear her voice."

Today The Bush School continues to fulfill that legacy and stands up, as Mrs. Bush did, for what teaching and learning can truly be. Bush offers each of us an opportunity to continue voicing our support for teachers, staff and students to find excitement in learning and meaning in life. Mrs. Bush would have been the first to say, "Well done!"

BUSH PUPILS MODEL AT STYLE SHOW

Left to right-SALLY LANSER, l\lIDGE l\IcPIIEE, BETTY RUBLE AND DIANA YATES To D>car spring clothes at review

When the pupils of the seventhlPerry B. Johanson. The show willjq.1eline Lillard, Ann Rolfe Ann and eighth grades of the Helen be sponso_red by Fr~derick & Nel- Joh_nston, Elizabeth Haynes, Nancy Bush School present a style show son. Pupil models \';·ill be Iann Mc-:Wnght of Yakima, Roberta Frink, Wednesday afternoon at Grace- Gowan, Lucia Parker, Leshe Louise !June S~ef~lman and Molly McCush jPO\\ell Gary Reed, Sally Jo and of Bellmgham. There will be two mont, 408 Blame Blvd., the models Sandra De Long, Elizabeth JVlullan, performances one at 2 o'clock and \Vill include Mrs. John K. Bush, Bo_b. and Bilf England, Alita Davis. the other at 2:45 o'clock for pupils. principal of the school, and Mes- VV)lliam Meister, John 1IacKenzie, Tea will be served after each perdames F. C. Rippe Carl Bricken Betty Lou Sargent, Barbara Joseph, formance by Mrs. Simeon T. Can, • Dorothy Watson, Susan West, tnl, Mrs. D. S. McPhee, Mrs. J. L. Walter Isaacson, F. A, Tucker and Nancy Mott, Carole Badgley, Jae• Johnson and Mrs. John Lecocq.

I have only two newspaper clippings from my earliest years at Bush while Mrs. Bush was still alive and these were occasional "society page" photos in both the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post Intelligencer. I suppose these notices were good free publicity. The annual fashion show and tea, sponsored by the Mother's Club, opened with adult models, including Mrs Bush! I remember going down to Frederick & Nelson's department store to be fitted but don't remember what I wore. With 30 Bush student models and six adults, it was a big event! It took place in the Gracemont basement ''ballroom." (1947)

Collaborating on their music lessons at Helen Bush School are -!-he Misses Phillis Ballard (left) and Midge McPhee, two of the many students looking forward to the special concert for Seattle school children by Claudio Arrau, Chilean ianist, at IO o'clock, March 25,

Here we are at the piano in the living room of Dorothy Allen Hall where I took piano lessons from Dorothy Hopper Jackson during the school day. Several music teachers gave private music lessons in this way. It was a great help for families who lived a distance from the school.

Marjorie Chandler Livengood at Gracemont

"Mrs. L" as she was called, became Headmistress in 1949, the School's 25th anniversary. No one could have been more different from Mrs. Bush than Mrs. Livengood though she was always viewed as the heir apparent and the change in leadership was accepted without comment What was not obvious at first was that, long before Women's Lib, Marjorie Chandler Livengood had a new vision for women and that was perhaps her greatest gift to the School.

Although she had been teaching at Bush for several years, Marjorie experienced a larger, different world while serving in the Red Cross during the WWII. I remember she returned wearing her uniform which impressed us all. Her first actions were to strengthen science offerings and to provide a stronger college counseling program. She was a very able administrator, though rather distant emotionally, more respected by the faculty than liked. She also modeled a new type of professional woman: mil thin and erect, a1most military in bearing, beautiful clothes (while we were stuck in our scratchy uniforms) and a kind of humor that made us feel "in on the joke." At one assembly, she used her wartime experience of how "a thin dime held in the right place" would ensure the best posture!

The 1949 April Rambler included an article by Marjorie about Mrs. Bush's death and one Mrs. Bush had written for the Rambler the previous year. In reading the two articles on the following pages, it becomes easier to appreciate the essence and style of both women.

1924-49 Our Twenty-Fifth Anniversary

VOL. VI

For the strength of her character, the wisdom of her mind and the l ove of her spirit, hundreds of Bush graduates consi der Mrs. Bush the most inspirational of women. In the success of their lives lies her greatest tribute· by their achievements she is fulfilled. (Tykoe, 1948) '

MESSAGE FROM MRS. LIVENGOOD

We lost some of the joy of this momentous year with the sudden death last fall of our director and dear friend, Helen Taylor Bush. It places upon us old-timers, grads, and faculty who knew her, the responsibility and privilege of interpreting her vision, The Helen BushParkside School, to the public. I say her vision, instead of tnstltutlon or enterprise, because that Is what It was. I become more oonvtnced of this as I see schools all over the country emulating the educational practices and philosophies so basic in her thinking.

Since the words of the Master, "By their fruits ye shall know them," have become society's most reliable evaluative criteria, so I say that because of you, our graduates, do we deserve and keep our place on the educational hori2.on. While we talk and correspond with you too rarely, stW we are delighted by re· ports of your progeny and/or your contributions to your community. The few of you who have returned as faculty members have been invaluable. Occasionally someone has asked, "How do you cope

with these novices, so inexperienced in teach_ing methods?" The answer is, "Easily, as they are so well trained In the Bush tradition, its integrity and ap· preclatlon of the value of each Individual."

Since we feel that you are so much a part of us, why don't you come and visit us rmre often? We would wel come your reactions and suggestions. While our building program continues, thereby changing the physical environment the original plan of a quality schooi for three-year-olds to graduating seniors remains, with the enrollment reaching its capacity of three hundred students. our graduates oontinue to be desired members of college communities, and so we see no need for any basic changes here at Bush. Bus, just as our country Is in an important period of clearer definition of, as well as greater dedication to the prin• ciples of democracy, so do we ::Onstantly examlne and evaluate In order to keep our day-by-day achievements In perfect acoord with fundamental objectives. This was the wish of Mrs. Bush; not a bigger but a c-.ontinually better school. To this end must we all consecrate ourselves

FROM THE RAMBLER, JUNE 8, 1948 1Rtminiaring

llu lira. Jius~

Looking back over the twenty-four years of the Helen Bush School brings mostly smiles to my mind. The first class, which I was asked by my neighbors to talce on, was adorable. All the group were great readers. They loved their trlpg, about which they wrote stortes and drew pictures; they sang and danced on the lawn; they constructed much of their own equipment

Nature was all about us and we re· veled In It, but my own family did not share our love of nature in all its phases

When Mr. Bush came in the kitchen @r one dark night and crunched under foot many small crabs, escaped from the sink, he lttered sounds that .!!!!Y not have been bad but they were loud. At my request those first years Mr. Dudley Bur· chard kept us stocked In snakes All was well untU one on the loose one evening draped itself artistically over the back of Eleanor Bush's chair as she was entertaining one of the neiglmrhood boys Finally his fascinated gaze made her look around, whereupon her shrieks could be heard farther than her father's.

We were very casual in those days (Continued ori Page 2)

Memorial Scholarship

Dear Alumnae:

I am writing to you about a mem· orlal for Mrs Bush Last fall when she passed away, it came as such a terrible surprise to me. Way back here in Connecticut, I hadn't even known she'd been ill. Most of you were undoubtedl y struck in the same way and wanted very much to somehow r~pay your debt of affection and wisdom and sweetness I had never realized bow much I owed Mrs. Bush until there was no longer a way to show her I remembered.

Some people have plaques erected In _ho nor of their goodness and generosity. I don't think this would do at all (Continued on Page 7)

PUii.is.HiD IY TIH STUDIMTS Of THI H(UM IUSH S,C1HOOt., su.nu l, WAS~

Reminiscing by Mrs. Bush from The Rambler June 8, 1948

Looking back over the twenty-four years of the Helen Bush School brings mostly smiles to my mind. The first class, which I was asked by my neighbors to take on, was adorable. All the group were great readers. They loved their trips, about which they wrote stories and drew pictures; they sang and danced on the lawn; they constructed much of their own equipment. Nature was all about us and we reveled in it, but my own family did not share our love of nature in all its phases. When Mr. Bush came in the kitchen door one dark night and crunched under foot many small crabs, escaped from the sink, he uttered sounds that may not have been bad but they were loud. At my request those first years Mr. Dudley Burchard kept us stocked in snakes. All was well until one on the loose one evening draped itself artistically over the back of Eleanor Bush's chair as she was entertaining one of the neighborhood boys. Finally his fascinated gaze made her look around, whereupon her shrieks could be heard farther than her father's.

We were very casual in those days-we never asked anyone to come to school, we just received those who appeared. During the summer we went up to the University Biology Station, or some other interesting spot. We usually arrived home the day before school was to start, then opened the doors the next morning to see who would enter.

We began school in the big playroom of our home. The second year we put a floor over the cement in the garage and arranged for the kindergarten there. We expanded onto the enclosed front porch and finally took over several rooms upstairs. We were very grateful when Lakeside moved out into the country and let us have its plant in town.

It was wonderful when Mrs. Ostrander offered us her home for a residence, Rosemary Hall we called it. It was a thrill when we bought the Wurdemannn house for the same purpose. We named it Taylor Hall. And, of course, it was a delight to acquire Gracemont.

The Building Committee is now concentrating on the main school building. The new primary classrooms and Reed Memorial Gymnasium, just completed are about perfect, and make us feel very happy. We shall feel quite complete when we have our new upper school class rooms and library, our new dining hall and reception rooms, and our new auditorium.

However much we appreciate our new buildings, it is not these material things to which we look back with greatest pleasure. It is the personal contacts.

How can we ever forget the girls and boys we watched develop, those who achieved highly because they put not only brains but also steady perseverance into their work. It was a thrill to watch latent artistic talents become a beautiful reality. And what a pleasure to see the contented faces of those who learned to work with and lead their group! We have taken a little time off to reminisce but it must be short as there is much to be done to carry out our future plans.

Message from Mrs. Livengood from The Rambler June 8, 1948

We lost some of the joy of this momentous year with the sudden death last fall of our director and dear friend, Helen Taylor Bush. It places upon us old-timers, grads and faculty who knew her, the responsibility and privilege of interpreting her vision, The Helen Bush-Parkside School, to the public. I say her vision, instead of institution or enterprise, because that is what it was. I become more convinced of this as I see schools all over the country emulating the educational practices and philosophies so basic to her thinking.

Since the words of the Master, "By their fruits ye shall know them," have become society's most reliable evaluative criteria, so I say that because of you, our graduates, do we deserve and keep our place on the educational horizon. While we talk and correspond with you too rarely, still we are delighted by reports of your progeny and/or your contributions to your community. The few of you who have returned as faculty members have been invaluable. "How do you cope with these novices, so inexperienced in teaching methods?" The answer is, "easily as they are so well trained in the Bush tradition, its integrity and appreciation of the value of each individual."

Since we feel you are so much a part ofus, why don't you come and visit us more often? We would welcome your reactions and suggestions. While our building program continues, thereby changing the physical environment, the original plan of a quality school for three-year-olds to graduating seniors remains, with the enrollment reaching its capacity of three hundred students.

Our graduates continue to be desired members of college communities and so we see no need for any basic changes here at Bush. But, just as our country is in an important period of clearer definition of, as well as greater dedication to, the principles of democracy, so do we constantly examine and evaluate in order to keep our day-to-day achievements in perfect accord with fundamental objectives. This was the wish of Mrs. Bush; not a bigger but a continually better school. To this end we must all consecrate ourselves.

Upper School, Grades Nine through 12

We were a small class, only eleven by our sophomore year, but I made good friends: Nancy Fuhrer, Sarah Curtis, Patsy Gilbert, Ann McKay, Sahlie Merrill. That year, we had English with Miss Johnson (Meta O'Crotty) who knitted her own form-fitting woolen sheaths in dark green, royal blue, cranberry red and invited real poets into class to read from their work. In her class, I wrote a novel about my great-grandfather, Charles Henry Demaray, who defied his family to elope with his young wife only to have her die of the plague three months later. Miss Haight (Mary "Sis" Pease '51) taught us World History in 9th grade and U.S. History our Senior year. Both my children were fortunate to have Meta and Sis for teachers as well.

So many of the faculty remain etched in my memory: Effie Hinman, who mothered us all through 7th grade English; Odette Golden with her glorious curly red hair and her impeccable knowledge of French verbs; Mme. Chessex, who taught French II so vividly that I wrote poetry and dreamed in the language. I loved Latin with Mrs. Lister. Alas we could only go through Latin II. Bunny Worthington coached basketball and scared us all with the need for responsible use of the chemicals in her lab while Mimi Campbell somehow got me through Algebra II. Emily Morse, my art teacher in seventh grade, studied collage with well-known Seattle artist, Paul Horiuchi. Many years later, I purchased two of her collages. All these women were extraordinary teachers as was the atmosphere in class: open, encouraging, stimulating, demanding, and fun. I felt blessed to be a part of it.

In those days, the yearly Fine Arts Festival was an important event involving both Lower and Upper School performers. In musician Karla Kantner's class, three of us-Sarah Curtis, Nancy Fuhrer and I- actually composed the music and libretto for a chamber opera, The Little Prince, based on the Saint-Exupery novella. The following year, Mary Lockwood joined Sarah and me to create The Marble Boy, from a Mary Poppins episode. That score included a flute part for art teacher, Windsor Utley. See following pages.

Neither of these were "great works of art" but seeing them performed so enthusiastically by the students helped me appreciate and enjoy the process of bringing ideas into form. It seems remarkably like some of today's Senior Projects.

e THE UPPER SCHOOL students and faculty of the Helen Bush School are sponsoring a festival of arts Thursday night at 7:30 o'clock in the Reed Memorial Gymnasi um of the school. Miss Midge McPhee {left) will be the pianist and' Miss Kathryn Jensen (center) is one of the art exhibitors. Miss· Pat Peters (right) is choreographer for the dance program. . -(l'os;;-1ntelllgcncer Pl1oto by Clarence Rote,)

Kathryn Jensen and Pat Peters were seniors. Photo was taken sometime in March, 1950, the year we wrote and students performed The Little Prince.

FINE ARTS FESTIVAL Program

I. Overture to SpringGray Skies - Junior Class Quartet Blue Skies - Freshman Dance Group

II. Trial by Jury - - Gilbert and Sullivan 4th, 5th, and 6th Grades

III. The Little PrinceEighth Grade Class

Midge McPhee, Sarah Curtis and Nancy Fuhrer, of the Junior Class, created this play and the musical setting, in conjunction v1ith their class in music theory~ They received their inspiration from reading " The Little Prince" by Antoine StaExupery.

IV. Pavanne - - Ravel ·

v. Patricia Peters Liebeslieder Walzer- Brahms Glee Club

Upper and lower school art work is on display throughout the building

Refreshments vdll be served in the Library following the program

Hay 25 t h

11 COME DON N TO KEJ.f 11

The He l en Bush - Par ks ide School

FINE ARTS FEST I VAL Pr ogram

8 o 1 cl ock

" SUMER I S I 1CIB.1Ei~ BJII - Carl Deis

Twelfth Century Engl i s h Round

Seventh and Eight h Grade Chorus

MAY DAY ON THE VILLAGE SQUARE

Dani s h Danc e

Sea Chanties

Fifth Gra de Boys and Girls - Sixth Gr a d e Boys

M a yp ole Dance - Fourth Grade Boys a nd Girls

11 JESU , JOY OF l,IA.N1 S DES IRING"

11 THE NI GHTINGALE"

Hel en Bus h Sc hool Gl ee Club

11 TRIO I N C MA JOR11 - Allegr o Movement

M a ry } Sa lly , a nd Nancy Lockvmod

J. S Bach Thoma s Heelkes - Haydn

" THE MARBLE BOY 11

A cr eati ve pr cject by Ma ry Lo c kwood, Sarah Cu r t is, a nd Midge McPhee

Seventh Grade Hi gh School Singer s

Mr . W i ndso r Utl ey , Flauti s t

Pupils Write Musical Play For Festival

Music composed by pupils of 1by Windsor Utley and piano Kantner. the Helen Bush-Parks.ide School• . • . l will be included in the school's accompaniment by Mrs. Jamcs 1 Mrs. Beale will ~onduct choral _t annual Fine Arts Festival pro- M. Beale. faculty members. numbers by the high-school glee 3gram at 8 o'clock tomorrow night Parkside pupils will prt>-~ent club and junior-high singers. in the school gymnasium. Danish and Eng·Jish folk <lances Sixth-grade boys will sing sea 1 Sarah Curtis and Midge Mc- with choreography by Miss The• chanteys. conducted by Mrs. Mor' Phee, seniors in music theory, odosia Young, instructor. ton C. Wilhelm. ,wrote lhe score for a musical l Three sisters, Sally, Nancy and Painting and sculptures by play, "The Marble Boy." Mary'Mary Lockwood, will play Haydn pupils of Utley and Mrs. John M. i Lockwood, also a senior, wrotejtrios, directed by Miss Karla Morse will be exhibited. 1,the script. The play will be per-·liormed by seventh-grade girls. a T~ music will include flute solos~- ---- - -

Just as we were about to return from spring vacation my sophomore year, 1949, the Upper School portion of the building burned down. Parkside was saved because of a huge metal fire door that had been instBlled when the newer wing was built. I remember seeing the charred rums of 1he beautiful giand piano sittins in what was left of the gymnasium. Marjorie Livengood was at her finest, carrying on with classes only a few days ai\er the event. We i:etumed in September to a beautiful new Upper School building built in part, I believe, with the help of insurance money! Again kudos to Mrs. L.

Senior year photo with "Court Pin" on my collar denoting vice-president of the student body. My later work in other girls' schools in the '80s and '90s, reinforced my belief in the continuing importance of female voices in leadership and governance.

Spring uniform available in pink, green or blue if I remember correctly (circa 1949).

With classmate, Nancy Fuhrer Christmas, 1947

Junior Prom 1950

Pa t Gilbert. new P resident of the Student Body

As yo u can sec from the picture, 1 am stil l in a state of shock. It makes you fee l awful l y good to kn o w that people like you and have enough confi dence in you to give you such an honor. J just hope that I can live up to the standards set by the previous student body presidents.

SJ1,1h Ctirtis. next 1·car's Editor of llw l~amblff

I .1m most h,1pp\' I<> h.wc bcl'l1 dedcd l'l\' the 1ourn,1hsm d.1,, to tlw rd110,sh1p of llw l?amhler for t h,· ,om,ng yc,ir.

A school p.1prr. 1(k,1l ly. is tht· rdkc uon of the school itself. I will strive LQward a trn\' reprcsen1ation of Bush, and prom1w Lo follow the requests .ind dm1ands of the readers even though th,·se requests might Jl tunes range from. "\Ve gotta haw more gossip'." to "C:.111cha cut down on the gossip?"

l t is my hope that. with the cooper at10n of the staff. the Rambler will re main an 1ntercst1n g ,ind vital pJrl of Bush life.

llAA\llEtl

June I. 1950

The Fine Arts Festival

Spring again '. And with it CJme our annua l Fine Arts Festival. on Friday evening. May 26. The fcstivJ'I w,1s sponsored by the Mother's Club as its money raising project for this year. Proceeds will go toward some necessary improvements and additions to school equipment.

The an d isplay. which was in the new gymnasium. was under the supervis ion of Mr Utley. It w,1s a comprehensi ve showing of ,111 forms of work, such as painting. sculpture and ceramics, done by students in all departments.

An interesting hour's program was given in the Reed Mcmori,11 Gym under the direction of Mrs. Wilhelm 1t i ncluded a rifteen minute excerpt from Gilbert and Su l livan·s "Trial by Jury,'' presented by the founh. fifth and sixth grades. The eighth grade class in theory" prepared a musical fantasy called "The Little Prince.· ·and the Glee Club. under the d i rection of Miss Townsend. completed the program. These features were interspersed with acts drawn from the upper school talent assembly. including a Junior class quartet, and ,1 dance number by a group of frcshmrn Par Peters also chose one of the dances of her recent concert for her parti(ipa tion in the entertainment.

After the program. refreshmrnts wac served in the upper school libr.iry.

CARt CARAVAN

hv J dy Ktr11• C'om,· st,1g ,r d.,t,·. to on,· of the BIG f--VI NJ S of le (.lr 1 Im will be the \ssoci.ued B, ·s ( lubs cLince- 'CARE CARAVAN. to be held June 3rd, ,n the ( l\'IC Auditorium. The musIC is by Bumps Bl.ickwdl s sen ior band . "CARF CARAVAN' ,s the title of 1111s dann·. because the proceeds go to tlw CARE UNESCO book fund, to buy text books for college students 111 Lu rope.

On the committee. for this d,1ncc. :ire st udcnt reprcscntat ivcs from every high school in 1hc city. The c h,1pcroncs in clL1de Gov. l.anglic and Mayor Devin. 11 is easy to sec what a big project this (Continued on page >)

Midge McPh,·,·. n, w Vice Pres id ~nt of the Studrn t 13ody

From the wonckrfu l S\'nd off you·vc given m,•. I know that ll<'X l yc.lr is going to be stupendous: it will h.1w 10 be. to live· up 10 your cxpect.llions. I hop,· to bccom,· bett,·r ,1cqu.11n1nl with you .111. bu1 not ncc,·ss.nily in court~

N,lllcy l'uhra, next yc.ir's Lditnr of the T yko" I il..e .1 Prom program. thl' I yk,w r<' c,1l ls the 1nC1dl'ntS of schoo l 1,f<, wl11d1 Wl' w~1nt to n..·n1l·n1btr forl'Vt·r It l'i onr of the Inv pl,lCL'S where the SJ)ll'I( "' th,· school and the trd,ng of 1he studl'nts can re.il l y be cxpn·ssed. l:vn ,inn· I c.1me to l~ush. I Ii.we hoped I cou ld be conm·ctcd with the ,111nu.1l 111 som,· w.iy. I .1111 vc.....ry honon:d to h.1vt· b1.·t.·n rhost'n w take ch.1rg,· ol 11 .ind I .1m look111i lonv<1rd to <.hung lh'Xl year's ~lnnu.1I ev,·n m ore· t lun I h,1v,· .11 w ,I y\ en joyed re,1d111g those· wh1d1 <.llnr be·fnr,· i t.

Chatting over tea cups at the graduation tea at Helen Bush School are Seniors (L to R) Gretchen Harms, Nancy Fuhrer, Sarah Curtis, Midge Bowman. Commencement Day is June 8. (Seattle PI, May 27, 1951) Note: Pictured on the Gracemont stairs.

40 mij, &rattlt tittttt.d

PR OC ESSIONAL

PROGRAM

INVO CAT IO N

GREET I NG

MUSIC

Rev . Oswald W. Jeffe rson

M ar jo rie Chandl er Livengood

Th e N i gh ti ngal e . Thomas W eelke s Weep, 0 Mine Eye s..........................................................J oh n W ilbye

Now Is the Month of Mayi ng............................................Thomas M orley

The Glee Club

MESSAGE

Directions

C ontrol-Creativi t y ............................................ ................ ..N ancy Fuh rer

The Step Beyond............... .............................. ................ Midge Mc Ph ee

The Big ''We''.. ................................................................. Patricia Gilbert

Education for an Open Mind..............................................Sa rah Curti s

MESSAGE TO THE CLASS OF 1951

Dr. Sherman E. Lee

PRESENTATION OF GIFT

Mary Lockwood

PRESENTATION OF DIPLOMAS

Mr. Harry Henke, Jr.

MUSIC . Pan i s Angelicus............................................ ........ .. ........... .Cesar Franck

The Chorus

BENEDICTI ON

RECESSIONAL

SENIO R RECEPTION

Rev. Oswald W. Jefferso n

Commencement was always outside in the courtyard, weather permitting. Arbors of white roses on each side of the area were in bloom at that time of year. We wore powder blue robes, carried salmon pink poppies and marched in to Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance. At rehearsals, Mrs. Livengood was in charge of the '78 recording that supplied the music. If she wasn't present to pick up the needle at just the right moment, the music continued into a noisy, very undignified part that destroyed the dignity of the moment and made us all laugh. At the end of Commencement, the beautiful Panis Angelicus was sung.

When I graduated and went off to Pomona College, I found I had been well-trained. Bush had given me the opportunity to think and write about big issues. What I hadn't realize at age 12, was that I had joined a community rather than an institution.

Mrs. Bush understood the deeper definition of education: educo, to draw out. My teachers trained my spirit and emotions, as well as my intellect. Always, regardless of the relative depth or rigor of my thinking, I was taken seriously and my ideas respected. Through their personal interest in me, I was able to make connections between what I was learning and who I would become as an adult. I don't know if the teachers did this consciously or whether it was the ethos of the school itself. Certainly I remember them continuing to learn and grow with us.

I can only imagine how different my life would have been if I my parents had not divorced and I had simply moved through a public high school. This is not about elitism. It is simply that Mrs. Bush understood how education could nurture the development of a whole person.

In the next six years, I would graduate from Pomona, marry, attend Yale Graduate School and achieve an MA in Music History, but my connection to Bush wasn't over. Time and again, I would return to share the gifts I had been so generously given by my teachers, paying them forward to the students of a new generation.

Note: It was only years later, after I had worked in both coed and single sex schools, that I realized the powerful gift Bush had given me in having women as mentors. At Pomona I remember no female professors, only "teachers" in the music or drama departments. Without that earlier example of strong females in every field, I question whether I would have had the assurance and perseverance to succeed in what was then "a man's world."

Graduation, June 1951. The Senior Plaque, titled In action faithful and in honor clear, was awarded each year to one Senior for service to the School. All the students voted. It meant a great deal to me to be selected. Journalist Meg Greenfield '48 also held that honor. I am not sure when the tradition ended but it was still in existence in the 1970s. It seems both the original plaque and the tradition have disappeared.

God of Truth, Give us sight into Thy wondrous laws ofmight. And out ofchaos, Let there be Thy perfect ordered harmony.

God ofBeauty, Help us to see

All that's fair in flower and tree

And let our ordered lives confess The Beauty of Thy holiness.

Oh God ofPurpose, Make us strong

To use our knowledge and our song. To make the world more true, more fair.

Oh God ofPurpose, Make us dare

To make the world more true, More true, more fair.

School Song Words: Helen Bush Music: Marjorie Livengood

Bush Again 1958 - 1960

My husband, David, and I left Yale for Seattle in February 1957. While he waited for the Bar Exam in July, I took a job in the library at the University of Washington Music School. It was a wonderful way to use all the knowledge from my Master's degree in Music History and to meet other musicians, composers and doctoral candidates, many of whom became my friends. When it was discovered that I played the piano, many of the students and some faculty asked me to accompany them. I also met composition student, David Lamb, who I later commissioned to write a piece for women's voices based on poetry by Gerard Manley Hopkins. (See page 36)

At the same time, I began to study dance with Martha Nishitani, a student of Eleanor King who had been my dance teacher at Bush in 1945. Martha was the choreographer for the UW Music School opera productions and I was invited to join her performing group. I danced in two operas: Weber's Orpheus and Eurydice and had two roles, the Manticore and the Virgin, in Menotti's madrigal opera, The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore, both at Meany Hall (photo next page). I would later choreograph part of this work for my dance class at Bush.

In September 1958, I was hired by Marjorie Livengood to teach chorus, music history, and dance. Many of the faculty from my student days-Mimi Campbell, Meta O'Crotty, Mary Rattray, and Dorothy Miller were still there. It was a little daunting to become a colleague of my former mentors, but returning to Bush as a faculty member solidified those relationships into lifelong friendships. In working for Marjorie, I found her to be a fine administrator, but there was no longer the joyful, relaxed, creative messiness of the Helen Bush years. Still, she was exactly what was needed at this transition time. Her long association with Helen Bush and the school was a testament to her love and commitment.

In leading the Upper School Glee Club I was able to use much of the choral music I had performed at Pomona and Yale, including Dvorak and Faure selections. One Senior told Mrs. Livengood that Glee Club had been her most important class that year! Several years later, for the Shaker tune, ' Tis the Gift to Be Simple, I designed and sewed simple dresses for the Glee Club to wear as they sang and danced the piece I had choreographed. Cathi Soriano '77 said much the same about that performance.

THE :\IYTHICAL :\lanticore, playe<l by Midge is one of three syrn,bolic beasts in Gian Carlo Bowman, l\ilenotti's be "The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the )lanticore," to presented at 8 p. m. Tuesday ancl Wednesday at l\ileany Han by the Unh·ersity of \Vashington Opera Theater. John Stipanela is the poet in the madrigal fable for chorus, dance-1·s and nine instrume nts. The Opera 'fheater also will present the thh-d act of "La Boheme" in commemoration of the centennial of Puccini's birth.

Seattle Times, 1958

FINE ARTS FESTIV AL

TiiE HELEN BUSH - PARKSIDE SCHOOL

Ma y 4 , 1959

" A Sr.tall Inhe ritance" , a one - a ct play by J anet Spa lding

George ••

Elizabeth ••

H G. • • • Two Souls •

Property Men , CAS T

, Katherine Bruenner

• Susa n Wright

Janet S palding

, Veronic a Johnston

Alison Skeel

, Myrna McElhany

Pa tricia Newton

"Philosophy"

"Let All Mortal Flesh Be Silent"

" lie Are Ma rching to Pr a etor ia"

Tra ditional

Holst arr Marais

The Helen Bush - Lakeside Glee Clubs

Conductor, Mr . Tom Wendel

Dances related to paintings • • , • •• Seventh Grade

Van Gogh : Portina ri : Miro :

Wade Ballinger, Lynn Bl umenthal , Ros a bel Landberg , Holly Nash

Barba r a Leede , Nora Skeel, Sarah Kip Robinson

Mina Brechemin , Kristin Djos, Diana Pad elford , Cynthia Phelps, Kitten Sheehan

Dances related to poems of Fdith Sitwell • • Eleventh and Twelfth Grades

" Aubade 11 : Alice Cox , Patricia Newton

"Th~ee Poor Witches" : Veronic a Johnston , Su san Rutherford , Janet Spalding

• 1Trio for Two Cats and a Trombone" : Alice Cox, Eliza beth Kaufman , Patricia Ne wton , Pame l a Purvi s, Li bb y Ru ch ,

" An Enterta inment"-music by John David Lamb writt en expres sly f or The Helen Bush Glee Club , August-September 1 958 , to poems by Gerard l1anley Hopkins . "Cuckoo" " S p rin g and Fall"

" A Nun Takes the Veil" "Inversnaid"

The Helen Bush Glee Club

Flutes : Viola : Cellos : Horn : Barbara Campb ell , Jayme Clise

Kristen Harks

Mrs . R. H, Allport, Jill Hering Walter F, Cole

Play directed by Mrs, R, Hugh Dickinson

Dances and Helen Bush Glee Club directed by Mrs , David Bowman

The 1959 Fine Arts Festival included our collaboration with the Lakeside Glee Club, directed by my friend, Tom Wendel; performances by students in two of my dance classes; and the commissioned Lamb work, An Entertainment, for voices and instruments. This program remains one of the high points of my teaching in the arts at Bush. We also performed the Lamb work at the UW and were mentioned by arts critic, Lou Guzzo, in his Seattle 1imes review May 1959 (next page).

Young Com·posers Rebel Against 'Vulgar' Music

By LOUIS R. GUZZO

FOUR young Seattle composers, who are disgusted with "the vulgar dadaistic breas t-beati ng that has characterized the bulk of art music the past 50 years," have joined to try to do something about it.

They are Ruth Lewis, Kenneth Benshoof, David Lamb and Richard Levin. The first three are graduates of the University of Washington ! School of Music a]ld Levin stead of for other composwas a 1954 Harvard Univer-1 ers ." sity graduate in chemistry.

•

The fourso~e has arr~~ged Program in Detail a program of its compot1t1ons for 8:30 next Tuesday night AT Tuesday's c o n c er t, in the recital hall of the uni- Lamb will be repreversity's Music Building. Its sented with five composi"concert of rebellion" has the tions, Miss Lewis with four, blessings of the School of Benshoof with two and Levin Music, under whose sponsor- with one. ship it will be presented. Students, graduate st u -

In a statement accompany- dents, faculty members and Ing a mimeographed program, the Helen Bush Glee Club the composers declared: are co - operating with the " ... The ideas we repre- four composers in arranging sent may be summarized by the concert. saying that we believe music The glee club and Walter s ho u Id contain memorable F. Cole, French horn, wi11 be tunes, c I e a r 1y d e f i n e d led by Elsa Bowman, conducrhythms, logical formal struc- tor, in a performance of ture and, if possible, a sense L a m b ' s "Entertainment," of humor. whose sections are titled

"This is to say we feel "Cuckoo," "Spring and Fall," music should be character- "A Nun Takes the Veil" and ized by the word 'delightful' "lnversnaid." and should be far removed Cole and Elizabeth Ward from the vulgar dadaistic will combine for two sets of breast-beating that has char- "Horn Duets" by Lamb, and acterized the bulk of art mu- John Budelman, flute, and sic the past 50 years.'' William Scott, cello, for his "'RArPfnnt

A CHRISTMAS TEA at the home of Dr. Trygve Buschmann ls scheduled by Ladies Musical Club Sunday, December 10. Mrs, David Bowman who is a member of the club and also teaches music at Helen Bush

School, rehearses carols with three of the school's glee club members who will be performing at the tea. Left to right, Sigrid Marks, Merrily Clark and Kathy Tytus. The glee club ls directed by Miss Helen Turner,

Endmgs & Beginnings, 1960-1967

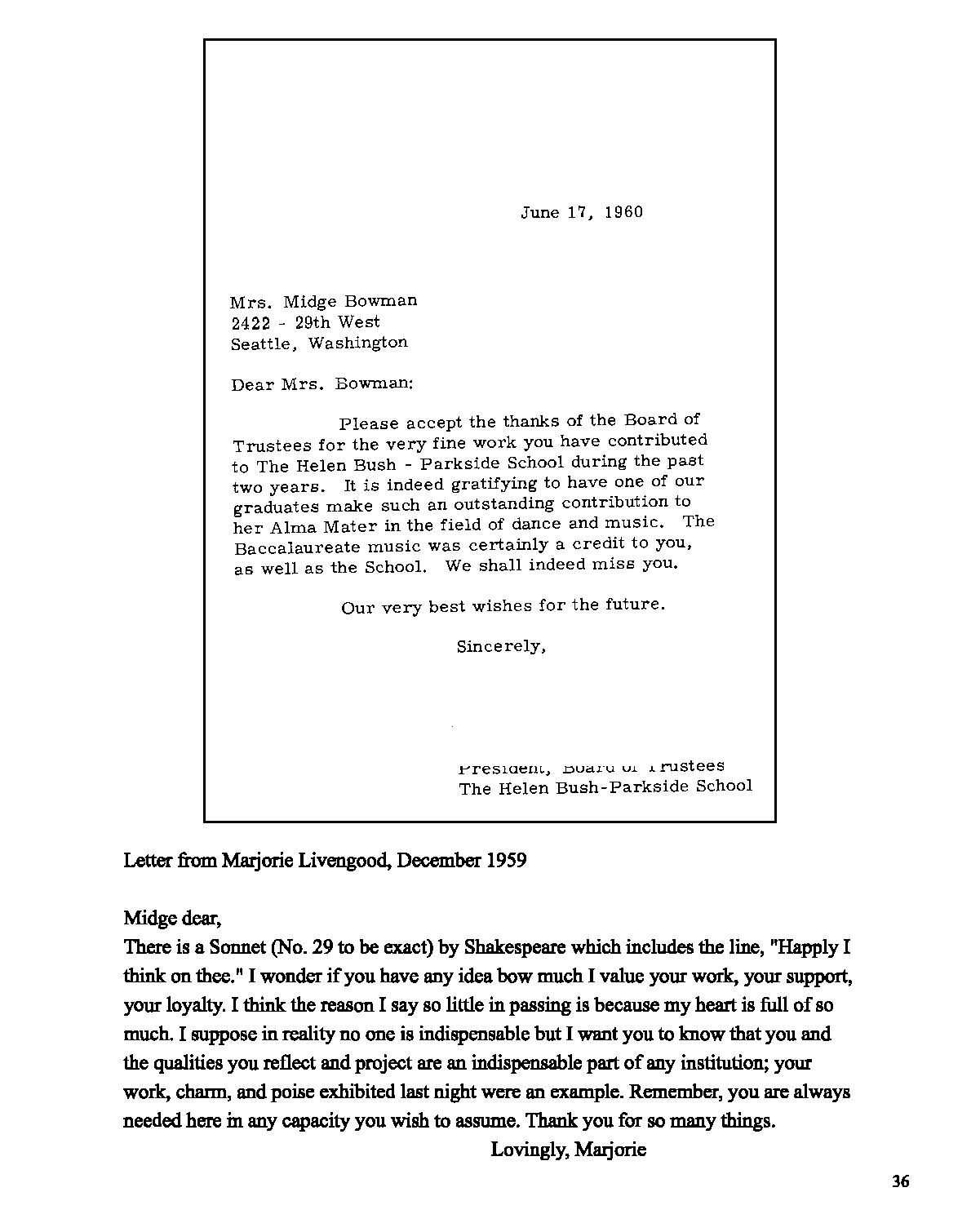

The above photo was in December 1959 and I was already in maternity clothes. I made it through Graduation in June, 1960, and our daughter, Megan, was bom July 29th. Three years later our~ Matthew, joined her. By 1967, I was back at Bush teaching dance and music part-time, the same year Marjorie Livengood retired. In an unexpected moment prior to her departure, she asked me to consider being her successor. I was touched that she saw me in that role but I had the good sense to decline. At that point, I could not know that in 1996, I would be appointed Interim Head of School. In one sense, Marjorie had been correct.

4

EAST 2-7978

June 17, 1960

Mrs Midge Bowman

2422 - 29th West

Seattl e, Washington

Dear Mrs. Bowman:

Please accept the thanks of the Board of Trustees for the very fine work you have contributed to The Helen Bush - Parkside Schoo l during the past two years . It is indeed gratifying to have one of our graduates make such an outstanding contribut~on to her Alma Mater in the field of dance and music. The Baccal aureate music was certainly a credit to you, as well as the School. We shall indeed miss you.

Our very best wishes for the future

Sincerely, d;;;f.:f

President, Board of Trustees

The Helen Bush-Parkside School

Letter from Marjorie Livengoo~ December 1959

Midge dear,

There is a Sonnet (No. 29 to be exact) by Shakespeare which includes the line, "Happly I think on thee." I wonder if you have any idea how much I value your work, your support, your loyalty. I think the reason I say so little in passing is because my heart is full of so much. I suppose in reality no one is indispensable but I want you to know that you and the qualities you reflect and project are an indispensable part of any institution; your work, charm, and poise exhibited last night were an example. Remember, you arc always needed here in any capacity you wish to assume. Thank you for so many things.

Lovingly, Marjorie

f

Headmistress Will Be 'Graduated' 1n June

ing school homes) that the milestones of her life ar the cl ass pictures that remind her she has been o hand lo line the girls up for every graduati on.

Oh, there are other milestones, of course. An accompl ished violini st, Mar.iorie Livengood played w ith the Seattle Symphony Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham. She had a year (getting back in t im e for graduation) as an American Red Cross field director in the Pacific.

1\Jrs. Livengood. daughter or lhe late \ilr. and \lrs. Archie Chandler, was born in California, moved to Philadelphia with her parents for a number of \'e,irs and returned here. Her schools are the Uni~·ersit:·, of Washington. Mills College and Columbia Cniversity. where she got her master's degree 1 school administration.

While on a year's sabbatical leave from Bush. she studied violin with .Josef Roismann of the Budapest st ring quartet.

Mrs. Helen Taylor Bush opened her school in 19:U in her home near the Church of the Epiphany, incorporated it in 1929 and moved to the present site in 1935. (Mrs. Bush died in 1948.) Mrs. Livengood lived in Mrs Bush's home and was a parttime teacher al first, later taught full time and then became headmistress.

The school was severely damaged by the earthquake of 1949 and later most of the original buildings were destroyed by a fire thought to be a result o~ the earthquake. During Mrs. Livengood's adminis1ration two libraries, a gymnasium, a dining hall and class rooms have been built. in addition lo the new class building being completed !his year.

MRS. MARJORIE CHANDLER LIVENGOOD

By DOROTHY BRANT BRAZIER

r ( Womrri"s f'<ews Eclilor, The Times

( Nexl .I L111e·s graduation class al the llelen Ru~h P:u:kside School will be the last one Jvl r~. ~Via rjorie t Chandler Livengood. headmistress. 11·ill .-1l1Pndofficially, that is.

But knowing hrr ren1rd of having l)een al every graduation since the first class. in 1934. no mal_lcr , where she m1ghl han' 10 come trom. we are "tll111g : to hel she will be showing up at fulLtre ones.

If not in person, certainly in thought.

Not many headmistresses can say they have _knnwn every pupil since the school began. bul Mrs. Livengood can.

After 40 years teaching, 10 in the Seattle Public Schools and 30 at Helen Bush, 20 of those as headmistress, Mrs. Livengood has announced she will resign in June. 1967. Resign. not retire, because she began teaching very early in life and because she will be doing other things.

Under Mrs. Li1·engood's administration, the school has tripled its enrollment, is completing a tenyear building program with the construction nf a new class building thal 1\ill expand science laboratones. and has survived "earthquake. fire and Sputnik ·'

Lived There , Too

Mrs. Uvengoo<l has spf'nl so much lime al lhe srhool (she has made her home in one of Jhe adjoin-

She Carried On

Tn "\lrs. Bush's day, such schools were "priva1f': loday they are "independent." Mrs Livengood failh fullv has followed the program laid down by Mrs. Bush-high scholarshir> and character ideals :1nd a curriculum where science and math are hand-in-:,and with the arts.

(lvlrs. Livengood is a member of the Sea[t[e Arf :Vluseum. always visits major museums while travel ing, and has had on the Bush faculty such artists as Guy Anderson. Windsor Utley and .Jack Fletcher).

Ad1hission Lo the school is on a basis of character and scholarsh i p. not race or creed. Each year, one open competitive scholarship to Helen Bush School is availabl e to all girls entering high school.

"We are not for everybody," she says. "We have our special character and, for those who want us, we are here. We have never intended to be a large school."

During summers, she went on field trips for the school, to meet parents of new pupils, and one year took some pupils to Europe. Two years ago, under her leadership. Parkside became the first elementary school on lhe West Coast to adopt the Initial Teaching Alphabet. a phonetic approach lo reading and writing

The difficult job of finding a new administrator is in the hands of Mr. Peter Garret[. president of the boa1·d of trustees. and Mr .John H. Hauberg heads the "search committee."

They are not looking for a "replacement," ior !hev feel Mrs. Livengood cannot be replaced. They are· looking for a succes~or.

Bush Will Lose Mrs. Livengood

BY LAURA El\IORY GILMORE P-1 Women'• News Editor

Mrs. Marjorie C. Livengood, headmistress of Helen Bush-Parkside School will retlre next ,June. AnnounrPment was made Friday at the annual faculty-trustees lunrheon at Gracemount Hall on th e school campus. She won't make her own plans for the futun until a new admlnJstrator is found.

"U I u a 11 y it takes month, - sometimes even years to find a su cce ssor," she confided.

"I have several educational projects in mind and I am very Interested Jn musla and art. I am a lso a great outdoors pers on.

"I love to go to the beach and hike and I know exactly how long it Mrs. Mariorie Liv•ngoo d takes to walk around Green Lake."

Mn. Livengood ha, taught In SMtth1 for 40 years and has been headmistress of the Independent iichool for nearly 20 yean, having succeeded its founder, Mrs. Helen Taylor Bnsh

IN ANNOUNCING the nE'~, Mr. E. P eter Garrett, president of the board of trustees, noted that Rush enrollment has trebled under Mrs Llvengood's administration.

He said, "Mrs. Livengood has spent a life time guiding children In the most respon~ive and most important periods of their lives. She has built a school which Is a complex organization of students, faculty, parents and alumnae. We feel a keen sense of regret and a great loss to the school . . . "

Helen Bush School hu an enrollment of 350, pres chool through high school. With the construction of a new conference and instruction unit this fall, the s chool Is completing a 10 year building program which has included two libraries, a gymnasium, a dining hall and classrooms.

Mr. John Haubt'rg heads the committee to find a new a dministrator.

Unfortunately, former Heads are often "old news" so it was wonderful to read in the 1969 Bush Bulletin that Marjorie had "landed on her feet" at Castilleja.

MRS. LIVENGOOD AT CASTILLEJA

Mrs. Marjorie Livengood, former headmistress, now works as academic dean at Castilleja School, Palo Alto, California. She learned of the employment opportunity from her friend, Miss Margarita Espinosa, principal of the School, who was looking for someone who wished to 11expcriment linguistically" with some students in grade seven. Prior to her new appointment, Mrs. Livengood had been enrolled in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania during winter term last year. In her words, she was "preparing for some dogood work in any needy community, here or abroad, by reviewing and updating word skills such as reading and spelling. My course included Linguistics; at last my concerns oflong standing had reasonable, perceptive answers." She writes she was in the process of formulating a "PROJECT."

I am sad that I was not in touch with Marjorie in those final years. I think leaving Bush was difficult and perhaps not completely her choice. I am also not sure that, in those early days, the Board had even considered an adequate retirement program.

Mrs. Livengood Dies

Marjorie Chandler Livengood, headmistress of Bush from 1948 to 1967, died last Sunday in Palo Alto, California.

Headmaster Lesl ie l. Larsen, Jr., announced Mrs. Livengood's death to the school last Monday and remarked, "We at Bush who have known her also feel a sense of great loss to the school. Those who did not know her know her heritage lives on in enthusiasm and dedication of young children as they go through their lessons and experiences at Bush.''

Mrs. Livengood became very much a part of Bush in her four decades at the school. She was hired by Mrs. Helen Bush in 1936 to teach music. During World War II she left Bush to work with the Red Cross and then she went to Columbia Teachers College before being named headmistress after Mrs. Bush's death in 1948.

During her 19 years as head of Bush she had to deal with rebuilding the school after the fire in 1949 and the addition of the Library in 1967', which was later dedicated as the Livengood Library.

One of her decisions that affects Bush students was her hirin_g of Meta

• Marjorie Liven~ood O'Crotty in 1949. She recalls that Mrs. Livengood hired her on the front steps of Bush.

O'Crotty adds, "I frequently told her she saved my life. I might not· have become a teacher."

Mrs. Livengood's warm personality enabled her to make long friendships with Bush alums. She taught Mary Haight Pease, '41, Bush History teacher, violin at Bush and later they worked together at Bush, remaining friends for 40 years.

Midge McPhee Bowman, Lower School director and class of '51, paid the following tribute to her former headmistress: "I will miss her vital-

ity, her strength, her wit and her love of music.

"She wasn't afraid of hard work and dedication. They were her middle names. I will miss her, but her spirit touched my life and that will remain with me."

In 1967 Mrs. Livengood announced her retirement as headmistress, a title she disliked. She preferred "principal."

Also in 1967, she was honored by the Matrix Table of "Women in Communications." The citation read as follows: " She has a reputation of having academic excellence while introducing scholarships, exchange programs which have brought Bush national attention."

She moved to California, where she was for l0years a member of the California Bach Society and head of the upper school at Castilleja School, in Palo Alto. She retired in 1973.

Survivors include Mrs. Livengood's sister, Mrs. James B. Matthews of Mercer Island, and two nieces, Marjorie Matthews Boothe, '50, and Susan Matthews Hall, '56.

The family suggests remembrances be made to the Marjorie C. Livengood Fund at Bush.

Another milestone was Marjorie Livengood's death in Palo Alto, January 1980. Now both women who had been Headmistress/role models to me as a student were gone. From her obituary in The Seattle Times:

A graduate of the University ofWashington and Columbia Teacher's College, she came to Bush school in 1936 after being head of the music department of Garfield High School. During WWII she was a violinist with the Seattle Symphony Orchestra. She later served as a captain with the Red Cross in the Pacific. She became headmistress in 1948 retiring in 1967. She later became headmistress at Castilleja School in Palo Alto retiring in 1973.

Correction from article: Marjorie was not headmistress of Castilleja although she was employed there.

It seems appropriate to include Dee's comments on Marjorie Livengood here since her memories of that early time are so vivid and give a wonderful picture of Mrs. L. and her consistent focus on the arts as a primary element in a Bush education. Beginning in first grade, music, art, dance and drama were part of the curriculum at every level through senior year rather than as electives. As Dee said, "It was the way we learned everything ... the way we learned to learn."

Marjorie Livengood was Principal when I was in high school. She taught the choir and once we performed Handel's Messiah with the Seattle Symphony. I loved Mrs. L. She was so good at everything. She wanted to make sure that we had all the abilities that we needed to succeed. For example, public speaking was very important. She would stand at one end of the gym and we'd stand at the other end, and we had to project our voices to her at the other end of the gym. That was a really important thing to do. She was very sway-backed. When she was walking down the hall, if she saw me, she'd push me against the wall to make sure I stood up straight!

After the war, I was teaching Fourth Grade at Bush. I was dying to go to Europe, but had no money. Then I saw an ad in the paper for Special Services. I put in my application and received a telegram telling me to the report to Fort Ord with my bags packed for two years. I told Marjorie Livengood, what had happened and she said, "That's wonderful." From '51 to '53, I was in Germany with Special Services and created the Seventh Army Repertory Theater. A lot of the actors had been drafted from New York and Hollywood and we got them special leave to do the plays-scenes from Shakespeare and other different kinds of real plays. I said "we're not going to do that for the officers clubs. We're going to do it for the guys and the line outfits and truck drivers." We went on tour with these plays and when we came back, the Colonel in charge ran down the platform with his arms full of papers with all the reports about how wonderful it was. I learned how to do all that at the Bush School. When I was in England waiting for a ship to go home, I got a call from Marjorie Livengood. "The Head of my English department is pregnant. I want you to take over the department." I said, "Marjorie, I can't do that. I majored in French literature." She said, "'If you know French literature, you can do English literature." I agreed on the condition that I teach in the morning and in the afternoon work on a degree in English literature at the University of Washington. That's how I became the Head of the English department!

Note: Dee later developed the Northwest Arts Project with the Junior League to bring contemporary art works to public schools and founded New Horizons for Learning, an international network for educators. Her book, Teaching and Learning Through Multiple Intelligences, has been widely used. She credits all this work to her Bush education.

Transition: John B. Grant, Jr. 1967 - 1972

John Grant was hired as Headmaster in 1967. AB the first male Head of School, John brought new ideas and different ways of doing things. I'm not sure he fully understood the magnitude of the changes over which he was to preside and perhaps it was just as well that we plunged ahead.

Within a very short time frame, decisions had to be made about boarding, coeducation, location and diversity plus the need to raise money for faculty salaries, scholarships, and aging facilities-all while balancing the budget. Among my papers, I found a fragment of a letter Grant wrote in November, 1968. He begins with trying to frame Bush in the larger context of the educational changes that were taking place in the '60s. In the final paragraph, he outlines the challenges facing the school and here, I am struck by his repeated phrase, but not yet. It is as though he is trying to warn of the challenges facing Bush and the as yet inability of the school community to fully meet them:

...Not long ago, with the judgment day of Sputnik and the vast re-analysis of our national educational systems, Independent schools found themselves in the forefront of the renewed emphasis toward quality education. The solid academic curriculum, the Advanced Placement colll'Ses and the independent study programs of the Independent schools suddenly indicated a direction for others that has since become commonplace.

Now in this second wave I feel a similar model for more fruitful public schools can be found in the structure of Independent schools. Some elements of our schools represent

keys to the re-establishment of this "new humanism." Small classes which attempt to utilize the individual approach rather than processing quantities; faculties which are chosen for their individual contributions rather than arbitrary credentials and tenure; and parents groups which represent concerned and active participants and who do not shy from the high cost of quality education, are characteristics of the best independent schools.

Still, no one is going to seek the model of the independent school unless it truly deserves emulation and exudes the vitality necessary to command respect. Helen Bush/Parkside, for example, reaches out to its community with the stature of academic achievement, but not yet enough. We claim an emphasis on individual development, but not yet perfect. We try to bridge into our community with scholarships, but not yet adequately. We seek to use our independence to contribute to the development of educational advancement, but fall woefully short of this challenge. We seek personal and financial support from our parents and alumnae to strengthen our mandate for continued existence, but this is not certain. Parents and teachers together seek to find a meaningful and common relationship with our youth, which is still imperfect. Our entire school family seeks an active role in our community. How successful are we? Modestly so, I judge in all respects. I yearn for this school and this school family to meet all its obligations.

John B. Grant Jr.

Grant and the Board met these obligations to the best of their ability but his tenure was regrettably short. That is one reason I was grateful to interview faculty member, Peggy Skinner, and alumna, Michelle Purnell-Hepburn '75 since both came to Bush that last year we were girlsonly. Both shared some wonderful memories of John and those early days.

Peggy: As a student at the University of Washington, I tutored a Bush student. He was not a particularly strong science student, but a very engaging and interesting thinker. Anyway, after I graduated, I got a job in Shoreline School District, and that was the year, 1970/71, the levy failed. I lost my job through seniority. Then I saw a job opening at Bush School. I had a sense of Bush because of the student I had tutored and then met John Grant and liked him immensely. I remember being very engaged with the conversation that we had. And the School just seemed like such a good fit for me. I grew up in a very small town where everybody knew each other. And Bush was kind of like that: a sense of community, small faculty-maybe fifteen in the Upper School-and very interesting, engaging people.

At my job in a public school, I had a lot of people my age. And I just remember walking into this new environment with these experienced teachers that had been there for a long time. Dee Dickinson and Meta Johnson (later O'Crotty) were just wonderful mentors to a beginning teacher. Not in the sciences. I came in very confident in what I knew in the sciences, but just in terms of interacting with people and just being with experienced teachers. I remember faculty meetings in the library, well, I'm thinking not necessarily the first year, but a few years after that we had very talented people in the arts-people like Chip Luce and Dennis Evans and Norman Durkee-I think every single one of them was a practicing artist. When I think about my experience at Bush and the art teachers that were there, I remember these early faculty meetings in the library as not being tense. Sometimes we drank wine and laughed a lot.

In those early days, mid-morning, we had juice and graham crackers and apple juice or something out in the courtyard. Every day faculty and kids would stop and we would have this little snack. It was just a kind of a nice tradition. A lot of it, again, goes back to my small town upbringing. It was a small town kind of thing to just stop what you're doing and celebrate being with people.

I was the only one teaching Life Sciences when I began. There was another room for Chemistry. I taught sixth grade, a first year Biology class and an Advanced Biology course. And I loved it all. It was just really fun to have the opportunity to take the things I was interested in in college and then translate them so the students could use those same ideas. This was in the basement of what's now the Middle School. I remember in the winter, driving to school in the dark, teaching in a basement, driving home in the dark. But it was a wonderful kind of funky environment. After we built the new building, there were kids who came back just to go back and sit in those old rooms again.

Midge: Michelle, like Peggy, you arrived soon after John Grant was hired as the first male Head of School and just before Bush began to make several major changes.

Michelle: Let's see. I believe it was 1969 and I had come from Epiphany, so just up the hill, if you will. I knew that my time at Bush would be different than some of my neighborhood friends who would eventually attend Garfield or Franklin, near where I lived. Not only was Bush an allgirls school and a private school, yet in time, when boys were admitted, there were few boys of color. It added to the angst of being a teenager. That really shaped a lot of my experience at Bush and even when I entered college. At the same time, we saw more young women and young men of color come behind us.

I will say that starting seventh grade in 1969 and later as the class of 1975, we saw and experienced maximum change during our years there. Beginning with the uniform: Navy blue suits with the white Peter Pan collars and saddle shoes from Frederick and Nelson, then abolishing the uniform, becoming co-ed and admitting more students of color. Those were huge changes and on some level I don't think the School quite knew what to do with all ofus!

I was just talking with Sheri Stephens '75 recently and looking through our yearbooks. We were the 'bumper crop' class-that's what I've been calling ourselves as young women of color. Bush had never before had that many of us in one class. Starting with me in seventh grade were Marie Kurose, Helena Grant, Sheri Stephens, and Patricia Edmond. I believe Randi Dewitty and Risa Lavizzo-in 10th grade when we started-were the first women of color in the Upper School.

Midge: And then there was John Grant, the first male Head of School. What was he like?

Michelle: Coming from a school where headmasters were older Episcopal priests, John Grant was young, he smoked a pipe and had young children! He had a lovely sense of humor and he seemed to really, in an appropriate way, want to get to know and pay attention to the students. And I think he was quite outgoing. He would stop and talk to people in the hall. I thought John Grant was lovely. Then we came back in September to a new headmaster. It was like, what happened? Where did he go? There may have been some kind of issue around Mr. Grant leaving. I know I was too young to understand. I just thought he was lovely and missed him. So then we had to get acclimated to Les Larson. He was more introverted but he was fabulous also. Mrs. Larson was very gregarious and engaging too. If you saw her either in the school or walking down Harrison, she'd say, "Hi, how are you?" That kind of thing.

Midge: Was there still a Mothers' Club?

Michelle: The Mother's Club certainly was there when I started, and my mom was a Room Mother when I was in 10th grade. It must have been then because there were boys in our class by that time. My parents hosted a spaghetti feed and everyone loved my mom's cooking. It was fabulous! "Is your mom making spaghetti?" they would ask, and she was kind oflike the Room Mother from then on. As for as other activities, I was not on the school newspaper, but I was President of the Senior class.

Midge: Are there some teachers you especially remember?

Michelle: Sam Miller was my English teacher. I just loved her and cried when she left. One of the art teachers, Nelleke Langhout, drove a 923 Porsche.This was back in the 60's. I thought she was the coolest person in the world! And of course, Meta O'Crotty. She was so engaging. As I said, Bush wasn't totally ready for so many students of color in Upper School. However those teachers that made us feel welcome and made us feel that we belonged-we would do anything for them. I remember her reciting, "0 frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" from Lewis Carroll. I still say those words when we have one of those beautiful Seattle days. I also had George Taylor for English. He was delightful and funny. Wonderful sense of humor, but also, you just knew how intelligent he was. Peggy Skinner was another teacher whose tender age resonated with me. She was approachable and committed to her craft.

I am so grateful my parents sent me to Bush. Grateful that I learned how to study, and that has carried me through to this day. I am grateful for the small classes since I'm an introvert. I know I present as an extrovert, but that is because I must. The fact that if you mention someone's name, even today, especially in my class or the class in front of us, I can remember their faces. And a person who will remain forever in my heart was my, what did they call them then? When Seniors adopted a seventh grader? Kathy Jarvis was my, if you will, my Big Sister. She would have graduated in 1970, and she was so kind to me.

Lifelong friends, Michelle Purnell-Hepburn, Sheri Stephens, and Patricia Edmond-Quinn, Bush Class of 1975.

The H el en Bush / Park side School 405 36th Ave n ue East Seatt le Washington 98102 A C d 206 3 , , , rea o e , 22-7978 May 12, 19 69

Dear Parksid e P a r e nt:

As you no d o ubt hav e heard , there Pa rksid e adm i ni s tration, b eg inn ing ne x t that s h e must move to a n othe r p osit i on chil d ren n ow live. '

will be a change in t he September Mrs. Hunt feels perhaps closer to where her

Among h er many s i g ni f i cant contributions to Parkside has been her invalu a ble aid in the transition between Mrs. Livengood ' s tenure and min e. We w i l l mi ss her capable handling of Parkside; and h e r many f r i e nds amon g t he students, parents and graduates of Park side wis h h er we ll

We were most fort u nate to find on our own staff a person qualified to t a k e o n thi s demanding post !>'irs. David Bowman (t--lidge) will assu me duti e s as Parkside Director in September.