CONTENTS

Articles An Introduction to Metaphysics Isabella Logothetis

Simulated Reality Hypothesis Maria Kaddaj

Do we still exist when we are asleep? Estelle Qin

Idealism and the four tenet systems of Buddhism Isabella Logothetis

Sartrean Existentialism: free will vs determinism Stella Lucano

Absurdism: the futile hunt for meaning Isabella Logothetis

Debunking Nihilism - Maria Kaddaj

Reviews The Truman Show Estelle Qin

Plato’s Republic - Maria Kaddaj

Siddartha - Emilie White

An Introduction to Metaphysics

When asking people what they know about metaphysics, I have been met with an array of interesting albeit amusing responses. These have ranged from claims that it is some specialised field of quantum physics to confused questions about how it relates to Mark Zuckerburg and his Metaverse. Needless to say, while laudable attempts, neither of these are correct.

Metaphysics is instead the fundamental inquiry into the nature and operations of reality. Now what is brilliant about this field, or horrifying to some who don’t wish to plunge into a perpetual vortex of potentially unanswerable questions, is that it is the medium by which we define the constitution of our very existence. Covering everything from the nature of being, to causality, to the spatiotemporal framework, to the relationship between mind and matter, it involves a fairly comprehensive review of everything you could possibly desire to know about the processes, underlying forces and conventions that govern the internal and external domains.

Within this broad sphere, metaphysics can be dissected into two dichotomised strands based on how metaphysical objects are held in relation to the mind. The philosophically savvy of you will recognise this as the epistemological angle The first is metaphysical realism, which sets out that these objects are independent of the observer, and this seems to be the more conventional view of the subject object dynamic The second takes the antithetical position in its scepticism of the physical world; this is metaphysical anti realism. The latter is certainly thought provoking, and necessitates a revision of the validity of a true externality beyond the human condition.

Now that we have established that absolutely everything is subject to questioning, I will outline some of the main sectors of metaphysical analysis.

I’ll start with ontology, the study of being, which categorises entities by virtue of the qualities relevant to the nature of their existence. This is aided by the recognition of distinctions between metaphysical items, the most general of which being that between concrete and abstract objects. The former includes physical entities, while the latter refers to notions like numbers and propositions that lack causal power. Also prominent is ontological dependence which addresses the complex relationships between entities to determine what exists on the most fundamental level.

Identity is another concern that has plagued metaphysicians who are tasked with dissecting what defines an object in terms of the set of qualities that distinguish it from other objects. While at first this might seem relatively uncomplicated, this is diminished in the consideration of transience, and how the retention of identity works with the added challenge of causality. Time is responsible for a concerning number of philosophical problems.

Speaking of which, space and time is the final field that I will mention. It may be the most likely to make you question everything you have ever known. This sector deals with the validity of the spatiotemporal framework as objective as opposed to it being signed to the subjective human condition as functions of the intellect So the whole world is up for contention.

Welcome to the joys of metaphysics!

Simulated Reality Hypothesis

Think of the Matrix, Hilary Putnam’s ‘Brain in the Vat’ experiment, Descartes ‘Evil Demon’ what do all of those things have in common? The answer to that is that they all adhere to a simulated reality hypothesis. For those who have not yet managed to give themselves an existential crisis by looking into it, according to the dearly trusted Wikipedia, “simulated reality is the hypothesis that reality could be simulated for example by quantum computer simulation to a degree indistinguishable from ‘true’ reality”. Now, if, like me, the person reading this has watched the Matrix, and Neo’s plight to figure out what “world” he was really living in was was both thrilling and utterly terrifying, then the question of “how do I know that I’m not living in the Matrix and my dog isn’t a sequence of zeros and ones” would have cropped up at least once. It would be so very comforting were I here to tell you with utter confidence that there is no way we could possibly be living in such a world, however, the reality of it is I, a seventeen year old A Level Student, along with a long list of philosophers such as Putnam, Moravec, Bostrom to name a few, have (almost) absolutely no idea. How’s that for clarification?

Take Hilary Putnam for example. His Brain in the Vat scenario is a thought experiment that proposes we (people and every other sentient being) are all essentially disembodied brains living in a vat, surrounded by liquid containing all the nutrients and goods that are needed to keep us “alive”, and all the nerve endings in the brains are connected to one giant super computer that sends out “electrical impulses'' to keep the brains functioning, much like a “real” brain does. Creepy right? If at any point, and I mean down to a millisecond, you entertained the notion that maybe this Vat existence is a possibility, then, according to Putnam, you cannot say that there isn't’ a possibility that everything we perceive about the world around us isn’t real

Here’s where it gets a tad more complicated.

Putnam isn’t, and won't be, the last person to propose a version of the “skeptical nightmare” that is simulated reality, however, what makes his version so concerning is that it doesn't actually fall under the usual criticism of these types of arguments in his version, there is a point of view from the envatted brains, and a third party perspective. For argument's sake, let’s stipulate that the envatted brains are speaking in “Vat English”. When said brains say “oh look, there is a tree!” the statement is objectively true because they are speaking a language where tree means simulation tree, but when the third party describes the same scenario, they would say “there is no tree” and also be telling the truth, because it is not speaking in “Vat English”, it is speaking in “Third Party English”. To make it simpler, he is essentially saying that if we were in such a situation, we wouldn't be able to acknowledge the fact that we are “brains in a vat”, because “brains in a vat” doesn’t actually mean “brains in a vat” and so we wouldn’t be correct. Headache anyone?

Having heard a nutshell version of Putnam’s argument, I’ll pose this question to you, reader can we really believe that what we know about the world is “real”, or are we just living in one giant simulation? *cue the Matrix soundtrack*

Do we still exist when we sleep?

Have you ever had a dream that was so real that you can’t remember if it actually happened or not? When this happens, how do you separate dreams from reality? How do we know if we are not in a dream right now?

Empiricists, such as the likes of George Berkeley or John Locke, claim that knowledge comes from our sensory experiences. However, Descartes proposed the dream argument, undermining the power of the senses as they can easily deceive us. For example, the alarm that is going off in reality may sound like a voice or music in your dream. Then, how would you know if our senses are not deceiving ourselves right now? How would you know if the world we are in is not another dream world? Christopher Nolan’s film Inception (2010) explores this idea in a fictional way Spoiler alert: one way to tell if the world they are in is real is if the spinning top stops spinning At the end of the film, the audience is left with the question if they are still in a dream as the top does not seem to stop spinning

The radical sceptic Descartes went further. He hypothesised: what if an omnipotent evil demon took control and manipulated his thoughts so that if he thinks something is blue, it is actually red, or if he did basic maths, the demon would make him believe the wrong answer Descartes realised that he could doubt everything, even the most obvious facts. Using methodic doubt, he could no longer be sure of the existence of the furniture around him or the world he is in. He could not be sure of himself. Descartes reached the bleak view that nothing could be real. However, he realised that there is one thing he could be sure of his thoughts because in the act of doubting, he is thinking. Thus, Descartes came up with his famous phrase cogito ergo sum (‘I think therefore I am’).

With this, the fact that a thinking mind must exist, as the base, Descartes can build all human knowledge and prove the existence of other things, including the existence of God Having inadvertently created two realms, the mental and the physical, since we can be certain of the former, many have attempted to connect the physical to the mental in order to gain certainty of it too.

Thus, if we are dependent on our own thinking minds to be sure of our existences, this gives rise to the questions: what happens when our minds are no longer conscious and thinking? What happens when we are asleep? When we are sleeping, how do we guarantee our own existence by no longer being able to doubt or think? How do we know if the rest of the world still exists? Must there be someone watching you sleep to ensure your existence?

Do we still exist when we are asleep?

Idealism and the Four Tenet Systems of Buddhism

The human mind is an extremely powerful entity. It is responsible for the great marvels of our existence; the discovery of quantum physics, the genesis of artificial intelligence, antibiotics and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. However, some disciplines might argue that the mind has a much more fundamental role, dictating the manner in which we experience an objective reality which remains completely remote to us This is the question taken up by the four tenet systems of Buddhism, each of which attempts to explain the relationship of the individual to a world beyond the senses through the degree of the mind’s interference Does our internal experience accurately represent phenomena external to us? Or perhaps more pressingly, is there even a reality beyond the mind?

The first tenet system is called Vaibhashika, and it seems to represent the most conventional view of direct realism. Their epistemology settles around the idea that there is a subject and object when it comes to perception, meaning that there is an objective world beyond the individual's experience

The reliance on direct experience here stipulates the validity of sensory influx, which has ontological value, and that would make the mind a passive receptor of external information

The second tenet system is far more complex This one is called Sautantrika and it does not quite obliterate the objective world, rather arguing that the sense data is subjectively imputed. So while the mental and external world are equally real, ideas are copies of objects, rather than the objects themselves. As opposed to direct realism, this school postulates that we infer objects from the mental images we receive of them through consciousness of the forms in our minds, making our perception a projection of the internal world.

The Chittmantra, or mind only school, is where things become a bit more extreme. As suggested by the name, this system denies any true externality, dismissing it as a dream. Nothing exists outside of the mind, everything around you, all sense perception is all a product of the mind’s creation. While Sautantrika says some things can be imputed, Chittamantra says everything is imputed. Now it is undeniable that many would consider this view a bit severe, but many of you may recognise it woven in philosophy throughout the ages, for example, with Descartes’ systematic radical doubt. What Chittamantra’s ideology means is that samsaric misery from the continuing cycle of rebirth are mere appearances of the mind, and this changes fundamentally the way in which we must approach the selflessness of phenomena.

The fourth and final school is Madhyamika, but I will focus on one of its two subsections, referred to as Prasangika Madhyamika In this school all degrees of objectivity are removed, even in regards to the mind, which does not exist truly. Rather confusingly, objects are held to be like illusions, to both avoid the extremity of giving items total existence, as well as the problem of complete non existence. There is also mention of a kind of repository consciousness, aliya vijnana, one which unlike sense consciousness remains after death for three days until the next life becomes active and a new sense consciousness is created.

Through these four systems, the diverse range of responses to the concept of true externality, and the role of the mind becomes coherent, and complicates the question of the nature of perception. Perhaps we should push ourselves to look past what seems immediately obvious to consider different approaches to reality. The question remains, to what extent should we trust that we are undeceived by our experience?

Sartrean Existentialism: free will vs determinism

Many philosophers have debated on the notion of free will: some have posited an existentialist perspective, suggesting that humans are condemned to an unchangeable, radical freedom of choice. Others, however, have put forward that free will is an illusion; in reality all events that occur in our lives are completely determined by previously existing causes, even if those causes transcend the life of the individual. In this essay, I will be exploring Sartrean Existentialism and its implications, whilst concluding its implausibility because of the more coherent, overriding argument put forth by Locke and D’Holbach’s determinism

Existentialism is an ontological philosophy which is defined by the idea that we have complete autonomous authority over our own actions and destiny: so much so that it causes existential angst. Freedom is considered an essential aspect which constructs and permeates every aspect of human existence. Sartre, a 20th Century existentialist philosopher, coined this concept and took it a step further by saying to be human is to inevitably have the responsibility of freedom or in his words: “Man is condemned to be free”. The fundamental truth to human existence is defined by this ‘freedom’. Sartre considered our consciousness to be that which makes us radically free because it has an ability to separate itself from the objects surrounding them and grasp that object whilst being able to recognise yourself as not being that object In this sense, consciousness is fundamentally free because, chiefly, consciousness cannot be infiltrated by objects which induce one to act in a certain way; rather, objects reside externally as matters of choice. Sartre focuses very closely on the concept of choice, and more specifically, the responsibility that comes with it. There is no escape from freedom, thus, it can be said that choices are respectively inexorable consequences of being human: as Sartre puts it, “What is not possible is not to choose. I can always choose, and I ought to recognize that if I do not choose, I am still choosing”. This theory can thus be said to validate the idea of freedom because our human consciousness’ ineluctable obligation to choose comprises what constructs our freedom us simply existing suggests we are radically free.

For Sartre, to be truly free is to be able to make any choice uninfluenced by external forces, whether they be mundane or transcendental, and anything that interferes with that is what Sartre labels as living in “Bad Faith” (“mauvaise foi”) Bad faith is a psychological phenomenon within existentialism whereby one convinces themselves that they are not free to make a certain choice: it's a form of self deception causing people to live inauthentically. As Nigel Warburton explains “Bad faith is a lie to oneself” and “chosen as a flight from freedom”, suggesting that, by reducing our vision to a delusively single option due to external constraints that lead us to believe we are not free agents, we are, perhaps inadvertently, limiting our own freedom More comprehensively, Sartre views freedom as being an integrated balance between transcendence and facticity, composing our consciousness. So, when this equilibrium is disrupted, bad faith intrudes. Facticity represents all the unchangeable realities of an individual or, the totality of one ' s concrete occurrences things that one cannot change. Transcendence on the other hand, is a conscious individual’s ability to surpass or overcome the immediate situation represented by facticity. Bad Faith can be achieved by affirming one’s facticity and denying one’s transcendence.

Sartre would argue that our freedom is constant, even in bad faith: we are not changing our very construction, we are simply deceiving our consciousness to mask the possibility of freedom. However, what I believe Sartre underestimated was the degree to which one ' s facticity can truly influence them: his individualistic thinking presupposes a degree of freedom that is innate in humanity without considering the possibility that the limitations imposed on us through social constructs and standards, our own upbringing and environment, as well as our own individual experiences, pressure us to a far more constraining degree than Sartre imagined. He neglects to mention the context by which one makes a decision and the conditions of their environment that may lead to a choice being made, or not made. Sartre would simply rebuttal this sort of deterministic criticism as false he proclaims that adopting this kind of thinking is only done in fear of facing the extreme freedom we are burdened with However, the extreme feeling of freedom that we may feel we have could, by rejecting Sartre’s logic, be illusory free will is simply a figment of our imagination because it is in our nature to want a sense of control over our own fate and action. Consequently, existentialism may not hold up as strongly in endorsing human freedom as Sartre might have presented.

Philosopher John Locke was a figurehead that expanded on this idea: that freedom is non existent and only a human impression. He points out that our lives are fully governed under this deterministic phenomenon, however, we are under the utopian semblance that humans have free will and are in complete jurisdiction over their own actions Locke used an allegory to illustrate this: a man wakes up to find himself in a room He does not attempt to open the door and leave, thinking that he remains by his free will. Unbeknownst to him, the door is locked from the outside. In this scenario, the man has the sensation that he is free to choose whether he remains or leaves, but in reality this is not the case: he remains ignorant to the fact that he is trapped. Determinists like Locke, would argue that he never had free will in the first place, much like the boy in the stimulus, because all events are caused by previous events such that nothing other than what happened could occur

D’Holbach, another determinist, expanded on this and said that, “Everything is the inevitable result of what came before. Including everything that we do” suggesting that actions are the result of an unbroken chain of events that we cannot escape from. This would mean that all human acts are just part of the physical world, bound by its physical laws.

D'Holbach's reasoning was to identify the link between mental and physical states: he argued that mental states are just biological states, and if these are physical states, then there can be no difference between mental states and physical states. Thus, seeing as the physical world is deterministic even from an existentialist perspective then our mental states and decisions must too make up part of that deterministic world. D’Holbach does acknowledge that feeling of freedom however: it's hard to dispute that we want to feel free, we want to be autonomous when we are making our day to day decisions. Even though we might be constrained, we desire to be able to obtain self determination even in simple things like what we chose to eat for lunch, or what we chose to wear for the day However, D’Holbach argues that, though you might think that what occurs in your mind when you make a choice is nothing like a basic cause and effect link, like a bat hitting a ball causing the ball to move, it is, though more complex, very similar. The difference between the causes of human actions and the causes of physical events, is that our actions have many intangible causes that work together in a very specific way, causing action. These causes that work in tandem he labelled: “belief”’, “desire” and “temperament” so, what we call decisions are therefore just the inevitable results of mental activity combining in just the right way. Due to the specificity of this combination, hard determinists argue that just because we can't pinpoint the exact factors that led us to an action, doesn’t mean those factors weren't there to cause it

Let us suppose that a man is at a voting station, ready to vote for the next US presidential elections. Now suppose that man has a strongly republican family, and if he too didn't vote republican, it could mean being ostracised by his family: thus he votes republican against his own desire to vote democratic. Existentialists, like Sartre, would simply say that the decision he made was limiting his freedom, however, determinists would expostulate this notion. Determinists, like D’Holbach and Locke, would actually contend that the man was always destined to make that decision based on the culmination of all his beliefs, desires and temperaments: internal causes that external persons would not be able to comprehend. By this convincing logic, it is hard to argue that existentialism can permeate and endorse human freedom.

Though it may seem intuitively correct to adopt an existentialist ideology to begin with, due to our own feelings of free will as well as the well reasoned arguments as to why it endorses that aspect of humanity, the counter arguments presented by determinism and more logically coherent and thus implies that existentialism cannot endorse human freedom free will is simply an illusion.

Debunking Nihilism

Are you a closeted nihilist?

You know those moments where you feel like everything you’ve ever done is entirely meaningless because one day our bodies will all be worm food buried a good six feet underground on a giant rock hurtling through space? Well then, my friend, welcome to the big, bad, greatly misunderstood world of nihilism.

Now, trying to precisely pinpoint the very definition of nihilism is like trying to pin the tail on that donkey at that one friend’s 8th birthday party a practically impossible task. So as not to bore you with the centuries long debate regarding the exact definition of nihilism, I’ll give you the general gist of it. As presented to us by the lovely google, nihilism is “the rejection of all religious and moral principles, in the belief that life is meaningless''.

However, (and this is a big one) because nihilistic thinking is something that this generation is particularly fond of, everyone seems to think they know exactly what it is. Tell me, reader, do you really know, or do you just vaguely think you do? To save you from falling into the trap of quasi knowledge that I myself fell victim to before writing this article, I’ll give you a little rundown in a short segment I like to call: Nihilism? Close, but no.

Nihilism vs. Cynicism: Cynicism is “an inclination to believe that people are motivated purely by self interest”, in other words, modern cynicism is rooted in the disdain of society and those who make it up Unlike nihilism, the cynic does not think that life lacks meaning and a point, they believe that “what people claim about life is pointless”. See the difference?

Nihilism vs. Pessimism:

Pessimism is the “tendency to see the worst aspect of things or believe that the worst will happen”. Where this differs from nihilism is the fact that you don’t need to be a pessimist to be a nihilist, as Daniel Miessler put it “Nihilism itself is neutral [ ] All the Nihilist is saying is that the empty bucket isn’t full of invisible morality and truth and meaning by default It’s up to them what they put in there themselves.”

Having now established what nihilism isn’t, let's delve into what it actually is You might be thinking “you’ve literally just given me the google definition of nihilism, what more can there possibly be?”. In all fairness, you have a point, but nihilism isn’t quite as simple as that.

One of the biggest misconceptions the “I think I know nihilism but I actually don’t” people have is that they believe that once all nihilists accept the fact that their very existence has no real meaning, they descend into an all consuming depression Whilst quite troubling, this type of thinking can actually be attributed to a particular subgroup of nihilism called “passive nihilism” However, most nihilists will tell you that this subgroup is one you should avoid like the plague because all you will have achieved by subscribing to this type of thinking is a hefty pile of mental and physical ailments

The reason I call that presumption a “misconception” is because I believe that most modern nihilists will fall into a category dubbed “active nihilism”. These people take this realisation, this epiphany, that everything is meaningless and “rejoice” in it. They believe that once we have broken free from the shackles of a predetermined “meaning” in life, we are free to choose and decide our own ‘raison d’etre’, leading some people to some extremely altruistic purposes, like that of committing oneself to combat climate change and the ever growing list of environmental issues, trying to improve the access to sanitation and clean water in third world countries, fighting for female equality in the Middle East, and so on and so forth.

Now, tell me reader, in all honesty, does that sound all that horrific to you?

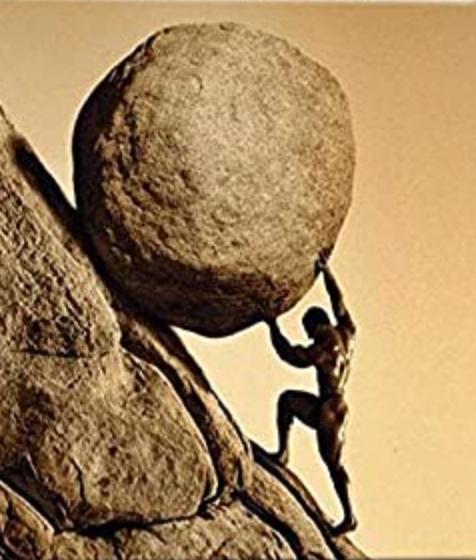

Absurdism: the futile hunt for meaning

The question of whether human life has inherent meaning, that can in some way be accessed, discovered and utilised by humankind, is one of the great questions that has plagued philosophy, resulting in an innumerable and diverse range of responses which extend from the Catholic monk Aquinas’ emphasis on the fulfilment of God’s eternal plan as the ultimate and universal purpose of human life to materialism’s acquisitive assertion that material success is the highest value in life. However, perhaps one of the most interesting, although slightly peculiar, responses to this question has come from the Algerian born French philosopher, novelist and journalist, Albert Camus

Camus’ philosophy is called Absurdism, which is fitting, because it sets out the radical claim that life is plagued by the an inevitable conflict between the inherent human inclination to pursue the intrinsic values of life, and the ultimate futility of this goal in the inability to find any of these with certainty. His recognition of the absurd human condition, and the intellectual prison it creates through this paradox, entraps mankind in a perturbing yet unsolvable conflict It seems appropriate therefore, that Camus’ expounds these views in a philosophical essay named The Myth of Sisyphus, which the Greek mythology buffs among you will recognise as the perfect allegory for the inescapable struggle he described. Sisyphus, the King of Corinth, twice cheated death and was given the eternal punishment of pushing a boulder up a hill in the depths of Hades, only to have it roll back down as he neared the top. This torturous image captures well the unavoidable cycle of pursuing value, and having every conclusion eventually proving invalid.

Now perhaps this is a crisis which many of us have felt before, grasping for meaning in what can seem like a fundamentally meaningless world, but luckily Camus did not leave us in want of a solution. Infact, he proposed three resolutions to the dilemma, only one of which, however, he deemed correct

The first of these is what he called “escaping existence”, or in less poetic terms, death. Unsurprisingly, Camus did not endorse this particular solution, stipulating that it does not dissolve the problem, but rather makes your existence more absurd. The second resolution is religious belief in a transcendent entity or destination, which goes beyond the Absurd and, unlike our world, has inherent meaning. This would require a “leap of faith”, to an idea not experientially provable and an individual reliance on the intangible, and it was not one that Camus found convincing. After all, this was in the devastated country of France in the aftermath of World War II, the tragedy of which lent itself to absurdist views and complicated theological convictions. It was the third resolution that this philosopher gave his support to, arguing that the only way to counteract the absurdity of existence was to accept it, and live in spite of it. It is only in this state of difficult awareness that we can consciously comprehend our fate, and it is this that gives us the greatest chance at freedom and control over our lives.

Counterintuitively, Camus admires Sisyphus, who continues to struggle with effort against the imposing reality of his tragic destiny. In this way he is triumphant

At first glance this view might seem unnecessarily pessimistic, with the existentialist Soren Kierkegaard even regarding it as “demoniac madness”, but perhaps there is something valuable to be extracted from these absurdist principles. What Camus teaches us is having the strength to recognise human limitations and vulnerabilities, but continuing to live with vitality and rigour regardless. He emphasises the importance of creating personal meaning, as well as acceptance of what cannot be changed, and it is potentially with these principles that we can begin to live the most effective, self determining life Depending on how you see it, Camus either ruthlessly condemns us to an existence of futility, or liberates us from the battle we fight against it.

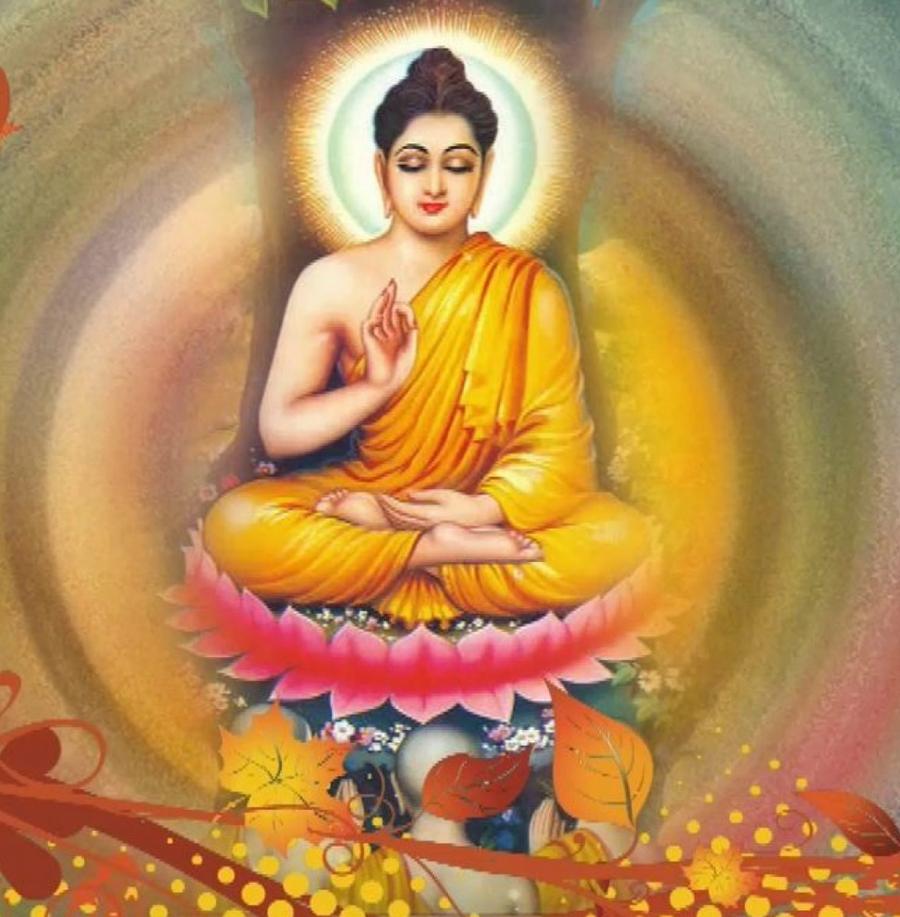

Siddartha - Hermann Hesse

Devoting himself to a spiritual quest in order to attain enlightenment, the novel Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse follows the life of fictional character Siddhartha as he embarks on a path to achieve Nirvana. ‘Siddartha’, derived from the Sanskrit language, can be interpreted as ' 'he who has found meaning of existence’, which is the ultimate goal within Buddhism. The author, Hermann Hesse, both German and Catholic, writes beautifully about the profound and subtle messages within Buddhism through the story of Siddhartha’s life Originally written in 1922 and translated from German, the inspiration behind Hesse’s novel was inspired by his travels to India where the teachings of Buddha influenced his work and in turn enlightened the minds of many through his writing. Although the novel does not follow the traditional story of the Buddha that many are aware of, it instead focuses more closely on the chronicled and spiritual evolution of a man living in India at the same time as the Gautama Buddha. For those pursuing a combination of religious experience as well as spiritual and philosophical ideology, Siddhartha provides a wonderful framework whereby Buddhist teachings can be explored more easily by a Western audience

The story begins in the Himalayan foothills of Nepal, where the Brahmin protagonist sets out to seek a fulfilling life and inner happiness under the premise of discovering the ultimate meaning of existence. Accompanied by Govinda, Siddartha’s journey leads him to discover truths about the falseness of society and our perception of it by immersing himself in the holy teachings. He then comes to the realisation that even in Buddhism, the acknowledgment of suffering cannot provide respite from uncertainty. Therefore, we must recognise our limitations and still maintain joy for life even in our suffering by embracing pain and anxiety. Other central themes of the novel unfold ideas of self discovery and peacefulness illustrated via the quote “within you, there is a stillness and a sanctuary to which you can retreat at any time and be yourself”

Overall, by reading Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, the fundamental teachings of meditation for inner peace, finding meaning in simple events and gaining self discovery are valuable life lessons.

Plato's Republic

If, by chance, you came here looking for an in depth, incredibly insightful and nuanced review, summary and interpretation of The Republic, this isn't the article for you. However, if you’re looking for a mildly amusing and straight forward review of the contents of arguably one of the most infamous philosophical books ever written, then sit down, grab a cup of whatever it is you like to drink, and let’s begin

So, the most pressing question first: what is The Republic?

To summarise the 10 books and 335 pages of political and philosophical Socratic dialogue, the book follows Plato’s musing through the mouthpiece of Socrates engaging in conversation with “a character converse” on justice, happiness and virtue, the crux of his argument being, as Michelle Jenkins put it, “we are better off just than unjust”.

One of the big questions I had when reading this was “what on Earth prompted Plato to write this book in the first place?” While there is no definitive answer out there, I’d take a wild guess and stipulate that it was probably going through the tyrannical rule of the Thirty after the Peloponnesian War and the collapse of the Greek “golden age” that prompted him to not only write but publish this book.

Now, to the moment we’ve all been waiting for the rating.

For fear of just blurting out the entire synopsis and spoiling the fun for you, reader, I will run through the books in bunches, giving a rough overview. In Book 1, the central question of justice is introduced, with Book 2 until Book 4 presenting the idea of the kallipolis and its ideal guardian. Book 4 begins to hint at the discussion of “virtue and vice in souls and cities”, this theme continuing in Book 5. Book 6 initiates the discourse on the philosopher king discussion, with Book 7 housing the notorious cave analogy Books 8 and 9 are centred around the 4 cities other than the kallipolis, with the intent being portraying the “soul of an unjust person” through the description of a tyrant Book 10 is the culmination of all the ideas presented in the earlier books regarding justice and happiness.

In my humble opinion, I give this book an 8/10. Despite being one of the most thumbed philosophy books, it's still not the easiest thing to get through, especially if you’ve never really read any philosophical texts before. However, having said this, if you are looking to start reading philosophy, whether it be for school or for fun (seeing as you ' re reading this in a philosophy magazine…), or you’re already an avid philosopher, I highly recommend giving this text a crack because it’ll be your launch pad into the deep end of philosophical thought on knowledge, justice, the good and virtue.

The Truman Show

Ever had one of those ‘main character’ moments? Maybe when you are listening to music on the bus with your head against the window… or when you walk into a room with your friends and they all look at you… What about a coincidence that just seems so unreal you cannot believe it? Or have you ever wondered if everyone has a secret they are keeping from you? Well, for Truman Burbank, he is the main character of his own show, “The Truman Show”.

Peter Weir’s “The Truman Show” (1998) is a movie featuring Jim Carrey who plays Truman. Unaware, Truman Burbank’s whole life from the moment he was born has been part of a popular, widely broadcasted TV show, which is all orchestrated by the executive producer Christof Shot by thousands of hidden cameras, Truman’s life is televised live, and the success of the show runs on the predictability of his life. Having observed him for years, the film crew and all the characters and actors in his life can plan their actions around him. Perhaps, the audience enjoy watching Truman so much because they find a sense of familiarity and kinship with Truman, who they watched grow up. Hence, after he noticed the odd repetitiveness and the unreal coincidences in his life, and began to break out of his daily pattern, doing the unexpected, the show quickly disintegrated, revealing more and more clues about the fakeness of his designed life.

One would think that a Hollywood movie starring the ‘goofy’ Jim Carrey would be lighthearted and even superficial at times, yet “The Truman Show'' surprised us all with philosophical and emotional depth. To begin with, this movie is a thought experiment re enacted, exemplifying French sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality, outlined in his philosophical treatise “Simulacra and Simulation” (1981). Truman’s world is a simulation of a world that is seemingly authentic, a hyperrealistic world, that fools Truman and blurs the line between reality and fiction. Baudrillard described four stages of simulacra (simulacrum: an image or representation of someone or something) with hyperreality being the fourth stage This stage, when the simulation no longer refers to any reality, embodies Truman’s life as he is surrounded by a constructed marriage and friendships. Even when he had found the only true, reciprocated love in Sylvia, she was removed from the show and his life. Truman becomes a mere puppet, ignorant and innocent, existing just to please the commercial movie industry and the invisible audience. In many ways, this film anticipated the popular genre, reality TV, which are just real life examples of hyperrealities. However, even reality TV only maintains the illusion of reality, often more deceptive than truthful.

As well as Baudrillard’s ideas, “The Truman Show” features Descartes’ idea of being unable to be sure of anything in the world, as Truman comes to doubt everything and everyone The movie is also replete with Biblical analogies, such as when Truman walked on water and ascended a literal “stairway to heaven”. Additionally, it draws inspiration from Thomas More’s 1516 work of political philosophy, “Utopia”, which depicts a fictional, isolated island society, similar to Truman’s devised world. Moreover, among many other influences, “The Truman Show” also draws on ideas of self identity from French psychoanalyst Lacan’s ‘Mirror Stage’, especially in the scene where Truman looks into the reflection of himself in the mirror, and what we see is what the mirror sees.

Lacan writes that this mirror provides a bridge between the ‘inner’ and ‘external world, and in this case, between Truman’s fake world and the real world. However, as the French film theorist Christian Metz writes in his ‘The Imaginary Signifier’, we must remember that while we watch the movie, although we may feel as if we are part of the cinematic world and that we have control, the truth is that this cinematic world is recorded and absent, only imagined to be present. Within this cinematic world controlled by the director, there is also another world: Truman’s televised world. The multiple layers of worlds causes not only the characters within the film, but also us as the audience, to fall into confusion as we work through what is reality and what is fiction.

Finally, the emotional depth of the movie is also what makes the movie successful (although it is not wholly realistic for commercial, ‘Hollywood’ effect) In particular, when Truman falls into a spiral as he begins to doubt everyone around him, including the emotional bond he thought he had with his ‘best friend’ and ‘family’, we are implored to imagine how lonely and betrayed Truman must have felt, the struggle he went through in order to figure out if anything was real, if Sylvia, his true love, was real. By the end of the movie, we perhaps have also become one of the spectators of ‘The Truman Show’. The extent of how entertaining we found the movie is perhaps unsettling as films become more commercialised, doing anything to satisfy our insatiable greed for entertainment