10 minute read

Seawolf 3.0: The reincarnation of an icon

Repurposing a legendary expedition yacht

SEAWOLF 3.0

THE REINCARNATION OF AN ICON

The refit of one of the fleet’s most classic and oldest yachts means it could still be operational for decades to come.

BY JACK HOGAN

The question of how the existing fleet will be able to meet owners’ changing demands and the regulatory imperatives surrounding emissions looms large over the industry. In recent years, there have been many examples of genuinely boundary-pushing concepts, as well as a handful of exciting projects across the major new-build yards.

These risk-taking ventures will hopefully lay down the marker for the next-generation fleet. What receives less attention, and what may prove more challenging, are the complexities of converting existing vessels to be more sustainable, capable of operating with lower emissions.

If the fleet is to evolve, forwardthinking shipyards will need to embrace complex builds and equally challenging owners’ briefs that may have seemed unprecedented a generation ago.

Pendennis has a storied history of taking on unique projects. When I visited the team in Falmouth earlier this year, one such project was underway. Strictly under wraps until now, the refit of the iconic 1957 tug conversion Seawolf is a fascinating exercise in energy repurposing.

The 59m Seawolf started life as the tug vessel Clyde. Delivered in 1957 by the Dutch shipyard J. & K. Smits Scheepswerven N.V., the 851gt vessel has a beam of 10.4m and a draft of 4.9m. Along with its sister ship, Elbe, they were designed to tow very high-tonnage vessels, with the latter famously towing two American aircraft carriers halfway around the world.

Clyde was transformed into an expedition superyacht at Astilleros de Mallorca between 1998 and 2004. A legendary vessel in the fleet, and infallibly capable by traditional marine standards, it now faces a sterner test: how to stay compatible in a changing world and start to meet the sustainability standards that do not accommodate its beautifully engineered – but outdated – modes of power generation.

Stephen Hills, commercial director at Pendennis Shipyard, says, “Seawolf is a great story because I think it epitomises what Pendennis is and wants to be in the future. This is an example of relifeing, repurposing and improving the environmental credentials of a yacht, and I think that’s a positive initiative. With Seawolf, we have clients who are deeply focused on sustainability, wanting to use the vessel to explore the remotest and least spoilt areas of the planet with as limited footprint as possible.

“From the outset the clients challenged the yard to introduce technology in order to leap ahead and start to address the issues surrounding the emissions that the vessel will produce in the future. The mandate provided by the client enabled the yard to invest time to explore everything from scrubbers to heat recovery to drive-shaft energy recovery.

“It is clear that the owners could have bought a new yacht; however, in addition to falling in love with Seawolf for the history, quirks and character, they saw a unique opportunity to repurpose an old boat rather than using all of the energy required for a new build. The direction received from these adventurous owners was that in order for Seawolf to reach its potential as an explorer vessel this can only be achieved if Seawolf becomes as environmentally friendly as possible.

“We at Pendennis have enjoyed the challenge laid down to us, we believe that the experience gained on this project will benefit the broader fleet in the coming years and we hope to become the preeminent yard for future conversions

of this nature. Plus, it’s a really cool [converted] tug! It has a heap of character. So the owner wanted to preserve the boat and re-life it.”

The term ‘re-life’ is an interesting one. The classic fleet, and specifically the utility of commercial conversions, is integral to the industry. However, encroaching emissions regulations are putting pressure on many vessels that were not designed with silent operation or low-emissions cruising in mind.

Not all such conversions will be as idiosyncratic as Seawolf. Far from being an off-the-shelf solution, it may be at the opposite end of the spectrum for low and zero-emission conversion projects. It’s not a total solution either. Hybrid systems don’t break the laws of physics, and the energy will still be created from conventional diesel for the time being.

What it represents is what is possible when seemingly insurmountable problems are approached step by step, integrating disparate technologies to give a vessel, even a very old one, the chance to thrive for another 65 years.

The owner’s brief for Seawolf was deceptively simple at face value: introduce an electric mode of operation and repurpose the surplus energy generated from the original engines.

“We looked at the vessel and said, ‘Well, we’ve got this boat, how can we make it fit for purpose going into the future?’,” says Hills. “One of the issues, obviously, that you need to do is address the fact that these aren’t the cleanest of engines by virtue of their age. What can you do to reduce consumption and reduce emissions?”

The ‘easy win’ part to this solution, as Hills puts it, is to change the three existing generators to clearer IMO Tier 3-compliant units with exhaust and particulate filters. The more complex aspect arises from the question of what to do with the energy created by the existing main engines.

The power-generation system on Seawolf is unique. Built to tow very large vessels, her twin Smit MAN RB-66 engines produce around 1,200kW each. Both engines feed one gearbox and a single-drive shaft and propeller. In its original towing function, it was designed to cruise on one engine and tow on two.

The excess power generation creates the opportunity for Pendennis to innovate. Hills explains, “Because the engines produce so much power, it was always ‘over-engined’ for life as a superyacht. What we have been able to do is refine the drive system and take that surplus energy and capacity in the main engines and redirect it to battery storage that will allow zero-emissions cruising.

“We are also fitting a new propeller that is specifically designed for more efficiency, where the original system was not. We are making the vessel as low emissions as possible without removing and replacing the whole prime mover.”

The key innovation, and a sticking point for the project, was the addition of a motor generator to the drivetrain. As many of us may remember from highschool physics, a mechanical motor can charge a battery if run one way or spin the wheel if the current is reversed. This simple principle, if they could find a way to mount it on the gearbox, would allow the behemoth engines on Seawolf to charge a battery bank with the excess capacity, further taking time off the generators in the process.

This redirection may sound simple in principle but it required a ground-up solution which was identified once the project arrived at Pendennis. Solving the issue of redirecting the power for the engines was one of the most challenging aspects – and one that Pendennis had to take back to the drawing board.

This is where Seawolf’s age has its advantages. Although presenting its own very specific set of challenges, the 65-year-old vessel has a platform that is more adaptable than an equivalent 25-year-old 70m superyacht.

“What we were looking at were refinements of the engine and systems technology and existing platform,” says Hills. “Unless you are looking at something very radical, like the installation of wind assistance or wing masts, this is the kind of solution that most of the fleet, classic yachts included, will be looking at.”

The fundamental issue that previous engineers at shipyards had struggled with was that of space. Hills explains that the range of works undertaken at Pendennis, and the extensive on-site fabrication and testing facilities, give them an edge. “I think that it’s probably a product of having done work on so many sailboat engine rooms and never giving up on the idea that you can fit a lot more into a technical space than people would first think. We knew that we could find a way but we would have to take it back to the test bed.

“There is a lot of debate in the refit sector, pushing hard on the issue of space. I think our role as an integrator is to stay on top of all of the new developments and

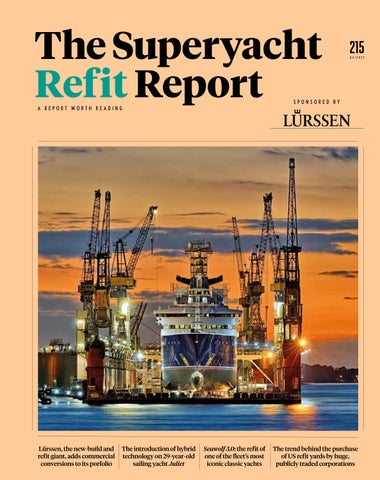

Top: Seawolf arrives at Falmouth. Above: Seawolf in the Pendennis shed.

Seawolf’s powergeneration system.

so we’re ready to say, ‘Well hang on, have you thought about this?’.

“For example, there are companies that are developing motor generators that will clump around the shaft, so it’s going to be inline and could even go on to existing shafts. Obviously, if there’s no space around it at all then it’s not going to fit, but people are looking all the time at new technology and we’ve got to stay on top of it.”

What is apparent when looking at this project is that, while unique and fully custom, all of the components are wellproven. Battery systems are increasingly common in marine applications and the regulatory code is relatively well established. The only truly novel thing in this project is the motor generator, and even this isn’t new technology.

Hills says that because the motor generator is a secondary part of the power-generation system that can be disconnected, and is not the main propulsive unit, which is a compliance consideration and provided some creative flexibility for the build.

The exciting part of this project is not the technology itself; hybrid electric propulsion has been employed in the marine sector for well over a century. Nor is it the use of a shaft generator, which is a standard piece of equipment in the fishing and sailing sectors. Having a reversible generator/motor that can both drive the vessel forward and draw excess energy from the main unit, installed in a restricted space, is what sets this project apart.

Another major special consideration is where to put the batteries. Here, Pendennis has repurposed one of the fuel tanks. The fuel capacity of 184 cubic metres is excessive for any 70m vessel, let alone one that has been redesigned for more efficient operations.

Not content with just improving the propulsive and electrical generation on Seawolf, Pendennis is also installing a comprehensive waste heat recovery system so that instead of dumping heat from equipment such as generators into the sea, the heat is returned and used to ensure all heating needs of the vessel are met. It is expected that this will make a major impact on the vessel especially when she arrives in colder climates.

As Seawolf is no longer likely to be called upon to tow aircraft carriers halfway around the world, losing one of the tanks to batteries was not terminal to its operations. Hills says that according to their calculations, Seawolf may in fact have slightly more range (8,000nm, give or take) due to these savings in efficiency, despite the reduction in fuel capacity.

This is where the design team were able to have some fun, in the engineeringfocused sense of the word. Redistributing the weight from the fuel through the placement of batteries keeps the vessel stability balanced and maintained through pumping between the existing tanks.

Walking through the technical spaces once the refit is completed, Hills assures me, anyone familiar with the highly recognisable engine room wouldn’t notice any significant changes (until Seawolf slid away silently from the dock under batteries that is.)

Seawolf now has multiple modes of operation, ranging from conventional diesel to fully electric. The potential addition of biofuels to further reduce carbon emissions is the hypothetical next step in the sustainability journey of this classic vessel.

The integration of proven technologies, on a proven platform, has given Seawolf a new mandate for continued operations.

A clear mandate from a forward-thinking client has provided an innovative shipyard the scope to rethink explorer yacht cruising for the next lifecycle of Seawolf. Whilst not the panacea to reach emission free cruising this futureminded refit will breathe new life into an old vessel and allow Seawolf to be operational for another 65 years … albeit a little quieter this time. JH