Editors |

Thabo Lenneiye (Editor-in-chief)

Leonardo Robleto Costante

Special Thanks |

Anoop Patel

Daniel Saenz

Jen Liao

Essay Authors |

Carlos Cubillos

David Gouverneur

Leonardo Robleto Costante

Muchadeyi Masunda

Yanyong Boon-Long

Project Authors |

Allison Dawson

Anneliza Carmalt

Anoop Patel

Autumn Visconti

Chenlu Fang

Cynthia Quinones

Daniel Saenz

Leonardo Robleto Costante

Meghan Talarowsky

Peter Barnard

Susanna Burrows

Taylor Burgess

On behalf of the citizens of the city of Harare and the city councilors, it is my pleasure to introduce this study towards the future of the city of Harare as part of the initial steps towards becoming a more inclusive World Class City.

The Harare 2040 project is the beginning of a dialogue about the future of Harare greater metropolitan area. This cross-cultural, cross-disciplinary approach to planning will help the city tackle old problems in new ways and look at new challenges as opportunities for growth and enhancement of our existing assets. Moreover, the great vision of Old Mutual in their funding of this type of avant-garde study is to be commended. It is an indication that the future of Africa and its cities can be greatly enhanced by a consolidation of Public-Private Partnerships.

Harare accounts for 40%, if not more, of the country’s GDP. Many Zimbabweans have left the country to pursue their dreams in foreign lands because it has not been possible to do so in Zimbabwe. Therefore, it follows that if we fix Harare, the toughest part of our challenge is done. Our city can learn many lessons from contexts and organizations across the globe, like Gensler and the University of Pennsylvania, that have encountered similar issues in their communities and their work around the world. As co-president of the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), I had the opportunity to take advantage of the many opportunities and resources coming out of the UCLG. Some of the resources include urban transportation system templates generated from more mature cities, implemented in places like Stuttgart by Mayor Wolfgang Schuster. Additionally, across the African continent there is a need to decentralize service delivery and stop looking to central governments for funds. People want to wake up in the morning, turn on the tap and find there is clean, potable water. Those who are fortunate enough to have cars should be able to drive over pothole-free roads. These are issues that necessitate separation of city development from Central Government politics. Moreover, mayors can and should leverage the assets, which the city owns so that these assets can be leveraged with a view to making them bankable and generate funding from financial institutions.

A world-class city implies all those imperatives that constitute a liveable city. Harare should be able to attract the right social and economic investors. Before we can reach our goal, we need to address the basic infrastructure issues such as water, sanitation, and electricity. We can only take on so many issues and be careful not to bite off more than we can chew. Once we have taken on the basic issues, then we can take the steps needed to make Harare grow into a sought-after destination for people who want to live in a progressive city. The research and proposals presented in this book represent the initial steps towards creating a vision for our city; and the future is bright for our sunshine city if we can use the ideas to collectively formulate and implement workable solutions.

HARARE ACCOUNTS FOR 40%, IF NOT MORE, OF THE COUNTRY’S GDP.

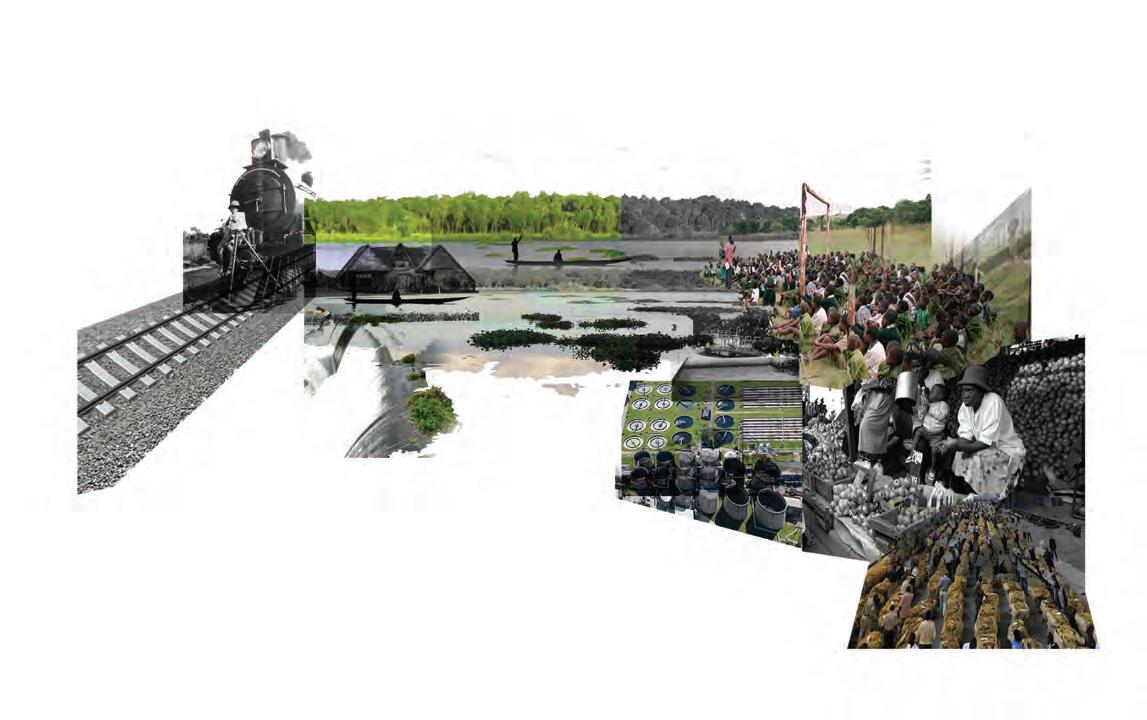

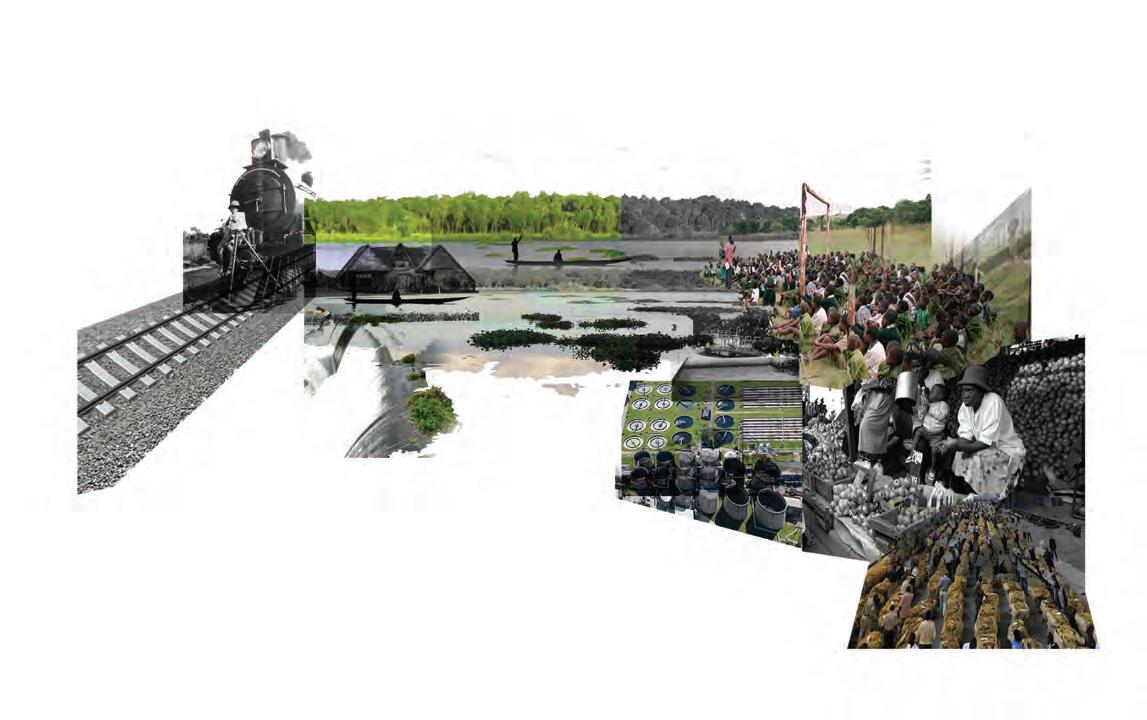

FOLLOWING CHINA’S FAST-TRACK GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT IN THE EARLY 2000S AFRICA IS POISED TO BE THE NEXT MAJOR FRONTIER FOR DEVELOPMENT. THE RAPIDLY URBANIZING CAPITALS ACROSS THE CONTINENT FACE MAJOR CHALLENGES IN THE COMING YEARS LARGELY DUE TO THE LACK OF BASIC INFRASTRUCTURE AND POLITICAL WILL. Forward looking and pragmatic design and planning agendas are key. Harare is a unique and complicated case-study for this and many other reasons. The city has a robust history of planning due to it’s colonial heritage, but the distinct challenges of the 21st century that the city faces suggest that the reevaluation of these practices is long overdue.

1 3 in

Case studies from cities like Bogota, where the changes implemented by Mayor Enrique Penalosa lowered the crime rates and catapulted the city into being one of the most widely admired

examples of the effects of highly specific targeted interventions, are indicators that the holistic approach of landscape urbanism has a high degree of merit for the developing world. This impetus for context specific solutions is the zeitgeist of the 21st century, exemplified by things like the emergence of the slow food movement and the rise in popularity of locally sourced and produced goods.

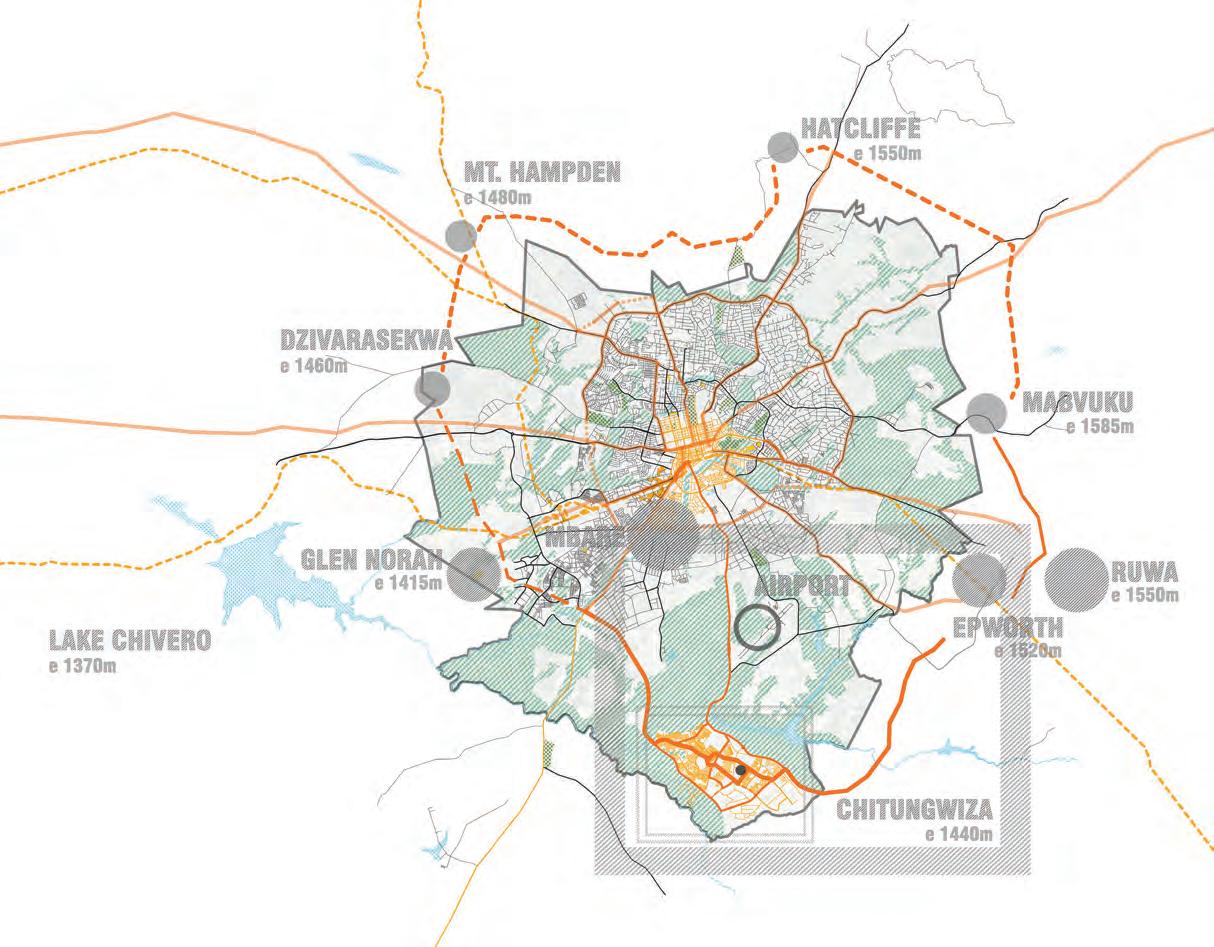

Present-day Harare was founded in 1890. First as a Fort on a hill, currently called the Kopje, next to a small African settlement where a diviner used to sing all night. The shona word harari means the one who does not sleep in Shona. Over the next hundred years, the City expanded in all four directions. As the economy expanded after the Second World War, a decision was made to build a dormitory town to the south, beyond the industries and with a green belt between the settlement and the CBD. It is from this town, Chitungwiza, that most workers today commute into the CBD. Similarly this pattern of commuting for work can be seen from other areas around the city such as Epworth, Ruwa and Norton.

The vision by the Harare City leadership for 2040 is for an integrated modern city, combining commercial, residential, recreational, and green spaces where employment opportunities are seamlessly integrated into the life of the City. Having bought into this vision, Old Mutual advanced a grant to the University of Pennyslvania and Gensler to support a group of students and professionals to carry out the first phase of sketching out what could drive the integration of the city. The larger goal of this initial phase is to identify key low-impact interventions that will create the space for lower income areas to move socially and commercially within Greater Harare.

When faced with rapid urbanization, a major challenge is to minimize burgeoning poverty in cities, improve access of the urban poor to basic facilities such as shelter, clean water and sanitation and to achieve environmentally friendly, sustainable urban growth and development. The National University of Science and Technology (NUST) in Bulawayo made available a group of students and Faculty to join the first phase. They concentrated on exploring potential future research areas in the CBD as the work of the vision evolves.

This publication captures a number of the project proposals from the first phase. The proposals represent the work produced by the graduate students from the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, while the work undertaken by the students from NUST will form the basis of a future study on the potentials of the CBD. The goal is to foster dialogue between residents, the business community and the leadership in Harare on how to take the necessary steps towards attainable and implementable projects. The combined efforts are driving towards a more cohesive and inclusive Vision of Harare for residents, investors, and leaders alike.

THE LARGER GOAL OF THIS INITIAL PHASE IS TO IDENTIFY KEY LOW-IMPACT INTERVENTIONS THAT WILL CREATE THE SPACE FOR LOWER INCOME AREAS TO MOVE SOCIALLY AND COMMERCIALLY WITHIN GREATER HARARE.

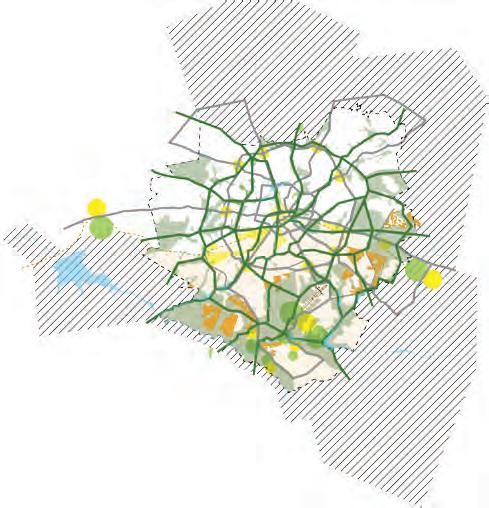

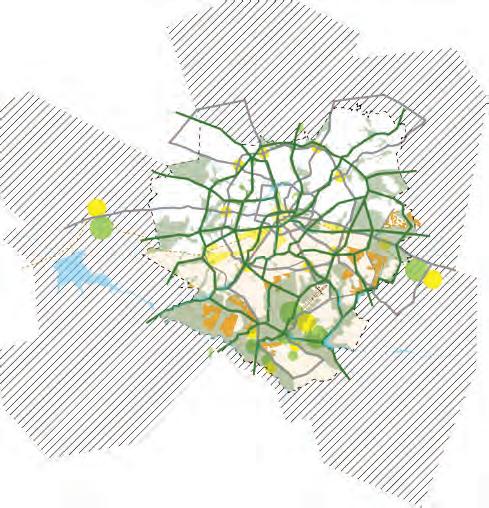

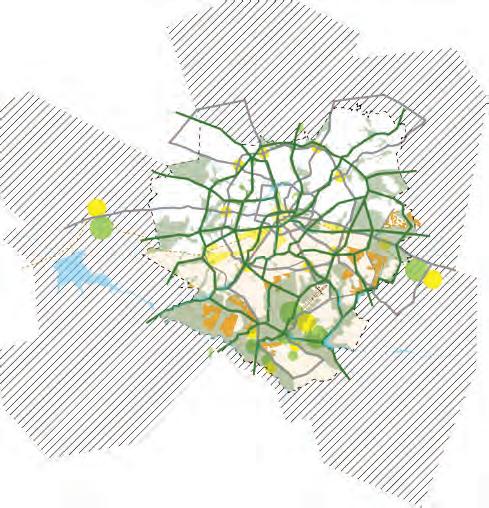

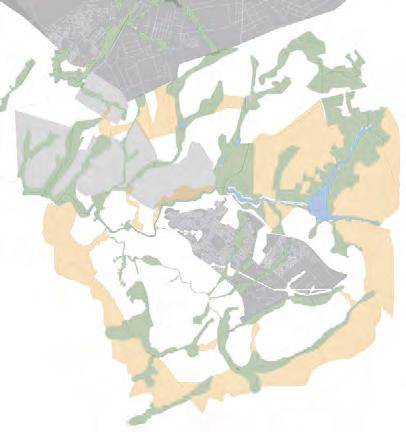

HARARE IS A DUAL OR HYBRID CITY. A SIMPLIFIED VIEW OF THE CITY SUGGESTS THAT THERE ARE THREE MAJOR COMPONENTS: THE OLDER COMMERCIAL, BUSINESS AND INSTITUTIONAL CENTER, THE WEALTHIER NORTHERN SUBURBS, AND THE LESS AFFLUENT AND MORE DISTANT RESIDENTIAL NEIGHBORHOODS TO THE SOUTH. A quick analysis of demographic projections suggests that if no planning, design, and political actions are taken, social disparities and spatial segregation will increase over the next decades. There is no precise information on the percentage of the population of Harare that lives in informal settlements. Official figures indicate that it is close to 35%, but professional expertise brings this figure closer to 50%. If the current spatial trends continue, the wealthier groups will continue to dwell in the north, with the emergence of new service and administrative centers, the traditional center will lose importance, and the less affluent population will occupy a more distant south. Increased social tension would be inevitable.

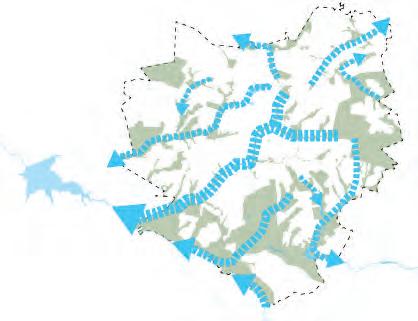

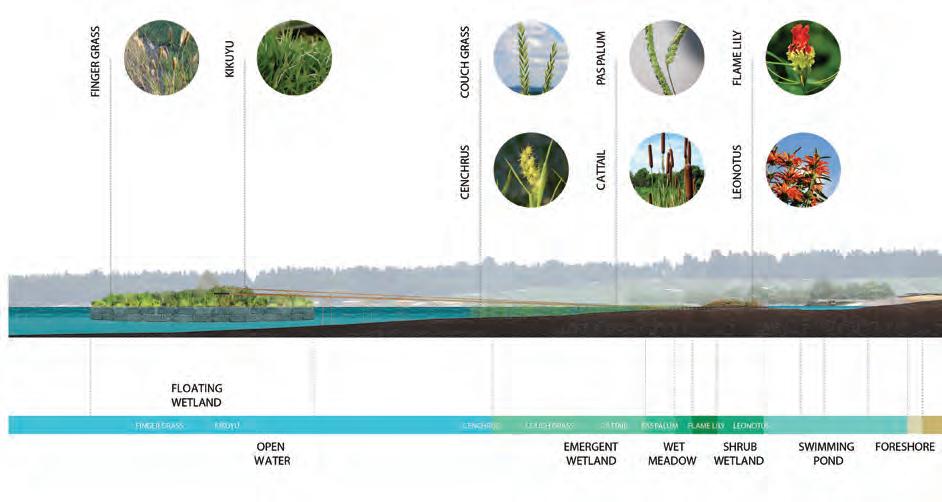

Harare is at a stage of urban development where it is relatively easy to introduce new planning and design paradigms. It presents good overall environmental quality, the urban densities are moderate, and there is land available for urban infill that can be built on, therefore avoiding urban sprawl. The city and country in general do not present the levels of violence that characterize other developing nations. One aspect that will deserve special attention is the conservation and intelligent use of the ample system of vleis or dambos (linear and shallow wetlands) that crisscross the city, and that play an important role in the city’s ecology and the conservation of hydrological resources. Today the vleis are relatively free from urban occupation. However, they are being gradually polluted by waste water

coming from urban areas and by fertilizers from smallscale urban crops. To secure them from unwanted occupation is absolutely necessary and can be done by making them more accessible as public spaces, with institutional or community stewards that will care for them, capture and treat the polluted waters and secure their environmental and landscape role.

It is important to mention that in Harare there are two particular conditions that are not common in most developing cities. Before independence the local population lived far from the urban center and the wealthier residential areas. They were separated by ample protected green zones; the negative outcome was enhanced spatial segregation while the positive resulted in the preservation of the cities natural assets. Additionally, current zoning by-laws impede mixed-use developments throughout the city. These regulations result in residents of poor neighborhoods having to commute long distances to access the commercial areas and metropolitan services in the center of Harare. The zoning restrictions eliminate the possibility of incorporating income-generating activities within the neighborhoods. For local authorities it is increasingly difficult to enforce these codes, particularly in the lower income communities.

To make Harare a sustainable city and a competitive one in the African context, the city needs to be proactive and creative in addressing social disparities and spatial fragmentation. This will require a very different set of design paradigms with the clear intent of integrating the formal and the informal areas of the city. The city would benefit from the creation of areas of new centrality; offering jobs, services, and amenities closer to the residential areas, avoiding time and energy-consuming trips to the city center as the sole provider of such amenities.

Most of these aspects were tackled by the group of students from the University Of Pennsylvania School Of Design, who took the special city of Harare as the studio site for an entire semester. The proposals contained in this publication offer creative insight on how urban growth can be managed to achieve a sustainable and just metropolitan area.

The majority of the proposals were directed to retrofit the peripheral and less affluent areas of the city, and to reconnect them to the wealthier zones. Similar studies focused on the growth of the northern part of the city should absolutely be conducted in the future. The inherent message is that if the city envisions a strategy that will strengthen the most challenged areas, the entire city will benefit.

Finally I would like to point out the importance of applied research of this nature. New paradigms in all fields of knowledge, including urban studies, usually emerge within Academia. However, with cities being the most complex of human inventions, responding to natural and social forces, urban research necessarily has to be tested by working directly in cities and not in distant labs. The perceptions and opinions of community leaders, city planners, developers, and bus drivers alike, in relation to how their city behaves and how it can be improved is equally important as that of an urban specialist.

The work of the students of the University of Pennsylvania was possible thanks to the vision, generosity and passion of public officials, professionals, students, and ordinary citizens of Zimbabwe that shared with us their knowledge, concerns, and aspirations in relation to the urban future of Harare. We would like to express our deepest appreciation for their involvement and contributions.

TO MAKE HARARE A SUSTAINABLE CITY AND A COMPETITIVE ONE IN THE AFRICAN CONTEXT, THE CITY NEEDS TO BE PROACTIVE AND CREATIVE IN ADDRESSING SOCIAL DISPARITIES AND SPATIAL FRAGMENTATION.

Written by Yanyong Boon-Long

Written by Yanyong Boon-Long

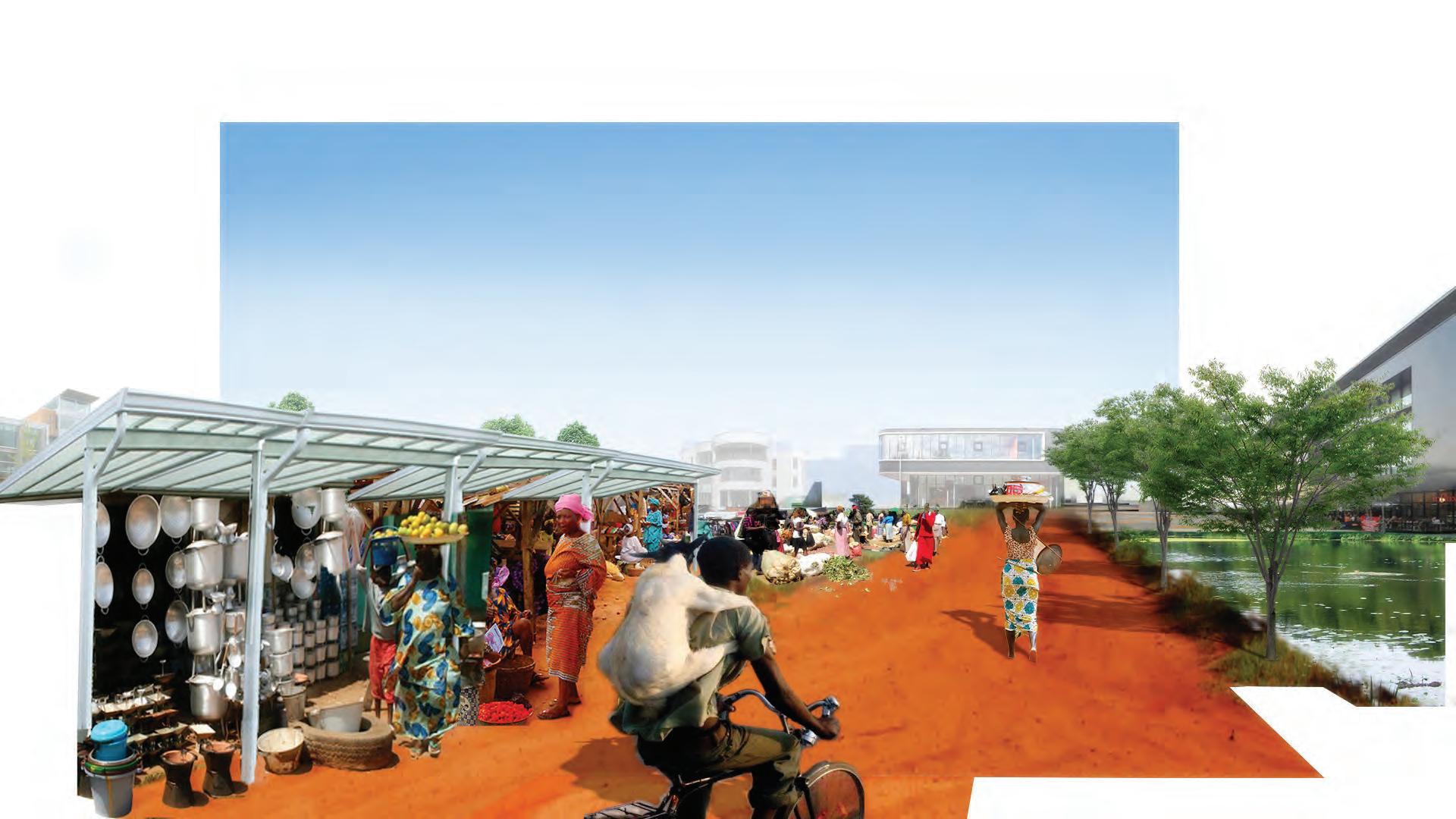

According to the City of Harare Planning Department, each day over 1 million migrant merchants pour into the city to sell goods. In a discussion about the potentials of the city, Mr. Psychology Chiwanga, head of City Planning stated “Harare supports the non-tax-paying population that commutes into the city on a daily basis. The city’s infrastructure cannot sustain itself this way.” This phenomenon is not unique to Harare. The majority of major metropolitan areas around the globe experience a large influx of migrant labor or commuters on a daily basis. They inhabit the city during the day and return to their residences in the evening, which are sometimes as far as 2 or 3 hours away. This puts immense pressure on the center, which should ideally be solved through different measures including densification of housing within close proximity. The interlocking shophouse is one such solution. It provides an opportunity to densify an area while increasing economic activity.

In late 19th century America, immigrant communities were known to make use of different variations of this concept. They combined residential and commercial activity as a way to increase their household income. This could be considered an early prototype of the shophouse. Although this was limited to immigrant communities and did not infiltrate mainstream society, the benefits were felt throughout society. The same occurence can be seen in Thailand, where the house is often viewed as an instrument

The informal sector is now the dominant force of the Zimbabwean economy. How can we tap value from the informal sector? They are not contributing value to the fiscus. There are no linkages between the formal and informal sector.

- Patrick Chinamasa, Finance Minister

for making a living. “Baan Ni Yu Laew Ruey,” which means, “this house will make you rich,” is a typical saying in Bangkok when migrant workers move into their new houses in the city. Their houses provide shelter, but are also expected to act as income generators. Frequently, these migrants start off as street sellers in the city. Upon accumulating enough customers, they open a shophouse so they can, in turn, store more products and gain more customers. The cycle continues, eventually leading to the development of entire communities.

During our tours of Harare and interviews of the residents, we discovered that a successful street seller can earn up to $2,000 per month while a potato seller in Mbare can earn $20 a day on a good day. City officials explained that the salaries of most formal

sector employees average about $150 per month. So it seems that despite the drop in large-scale agricultural production, small-scale independent farmers can be fairly successful.

The immediate problem facing these independent traders is the lack of housing and affordable commercial spaces. The city faces the challenge of finding a way to formalize these businesses. A shophouse is a building typology that could provide a stable foothold for micro-entrepreneurs in the urban core, while allowing the city to benefit from the income they generate. The combination of commercial and living space would require mix-used zoning for live-work. The benefits, including the creation of sustainable communities and generating income for the city would far outweigh any perceived costs.

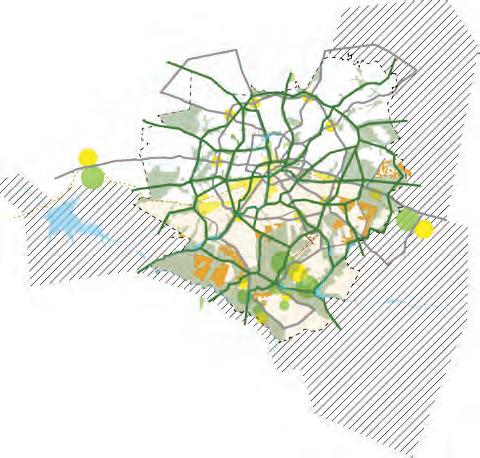

GREATER HARARE DENSITY

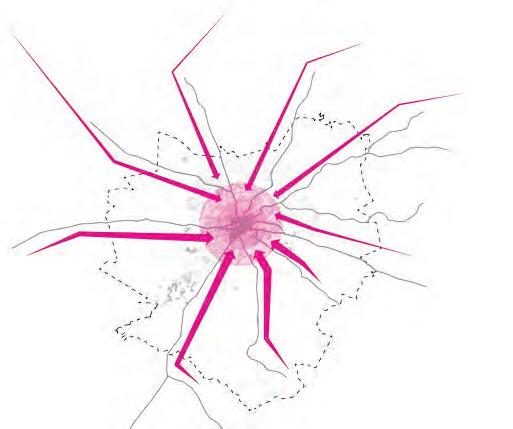

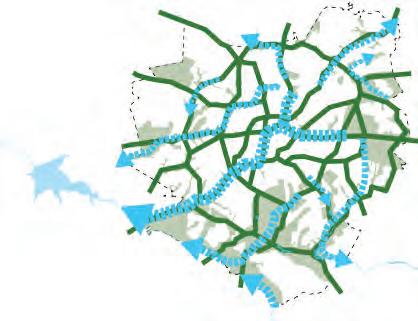

TRAFFIC CONGESTION

DISTRIBUTION

WETLANDS

DRAINAGE

MASHONALAND WEST

ZIMBABWE

MASHONALAND CENTRAL

MIDLANDS

MATEBELELAND NORTH

HARARE

MASHONALAND EAST

MANICALAND

NTWETWE PAN

BOTSWANA

SUA PAN MAKGADIKGADI PAN

BULAWAYO

MASVINGO

MOZAMBIQUE

KEY:

MATABELELAND SOUTH

SOUTH AFRICA

RAILWAY LINE WATER BODIES

NAMIBIA VICTORIA FALLS LAGO DE CAHORA BASSA*Distance

Hopley Farm = 14 km

Hatcliffe = 17 km

Epworth = 12 km

Chitungwiza = 23 km

Traffic congestion

WATER DEMAND 750 000 M /D

MAXIMUM SUPPLY 486 000 M /D

WATER

MAIN

CROWBOROUGH

CURRENT INFLOWS 300 000 M /D

WASTE WATER CAPACITY 486 000 M /D

44% OVERLOAD

MARBOROUGH STW

HATCLIFFE STW

CHITUNGWIZA

GREENDALE

EPWORTH

LEGEND

WATER CONTAMINATION AREA

SEWAGE TREATMENT WORK (STW)

WATER NETWORK

WATER BODY

MAIN WATER SOURCE

key plan

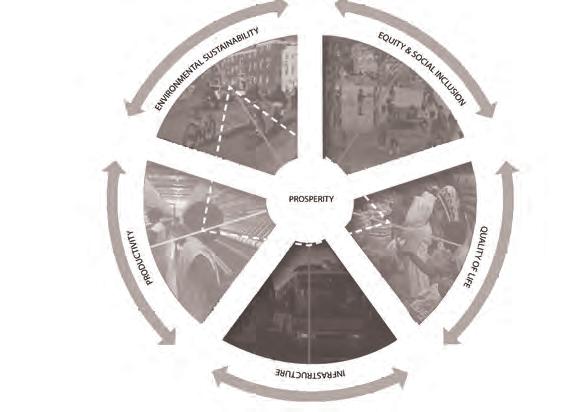

In 2012, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, also known as UN HABITAT released its annual report, State of the World’s Cities. For the first time it redefined urban prosperity as something other than economic. In addition to the traditional metrics productivity and infrastructure, the UN’s new definition now included environmental sustainability, quality of life and equity and social inclusion.

Urban success was measured by arranging these metrics in a five pronged prosperity wheel. Fig. 1 shows the wheel adapted specifically to the context of Harare. A successful city is one that maintains balance in all areas. By our own measurment, Harare has achieved some success in productivity and environmental sustainability. However, in order to become a world class city, Harare needs improvements in a number of key areas - namely, equity and social inclusion, quality of life and infrastructure.

www.unhabitat.org, 2012

Fig.1 United Nations Human Settlements Programme, State of The World’s Cities 2012/ 2013, Prosperity of Cities.

Fig.1 United Nations Human Settlements Programme, State of The World’s Cities 2012/ 2013, Prosperity of Cities.

0

BINDURA

CHINHOYI

CHAMVA

MUREHWA

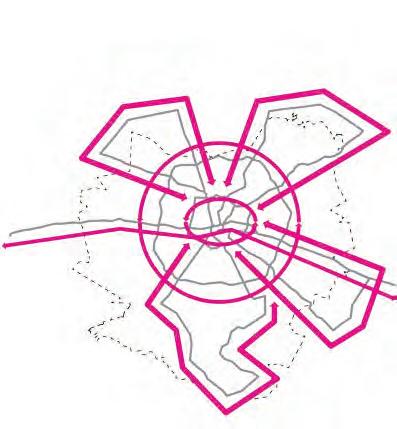

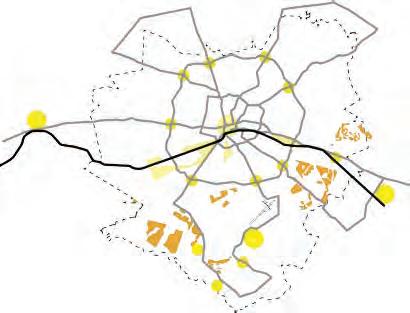

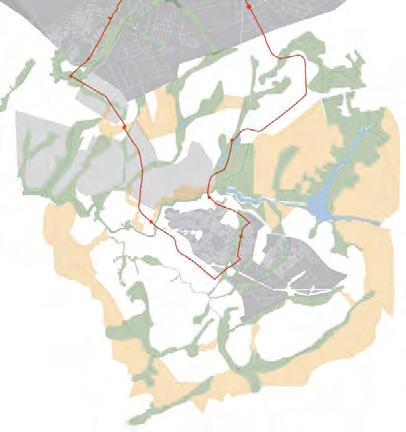

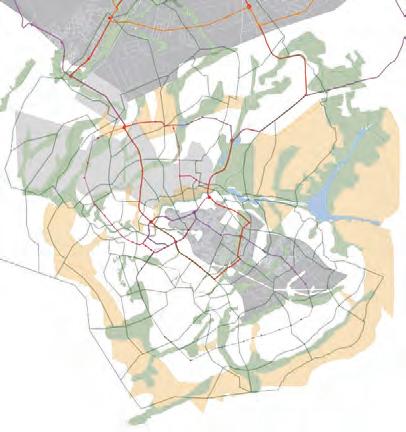

EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE

• The city has no public transportation system

• The commuter omni buses (private van system) do not have a consistent fare structure

EPWORTH

CHITUNGWIZA

GOROMONZI

• The arterial roads leading to the CDB are heavly congested

CROSS TOWN LINE

HARARE NORTH LINE

HARARE EAST LINE

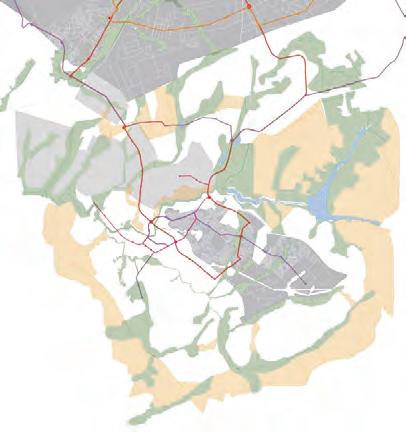

PROPOSED INFRASTRUCTURE

• Develop public Bus Rapid Transit system (BRT)

• Regularize the commuter omni bus routes and implement a consistent fare structure

CBD

OUTER LOOP INNER LOOP

EPWORTH LINE

• Traffic will be alleviated on arterial roads leading to the CBD with the above implementations

CHITUNGWIZA LINE

INDUSTRY

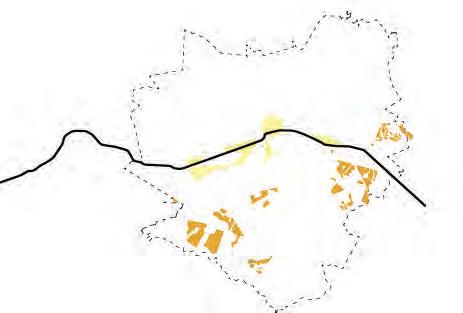

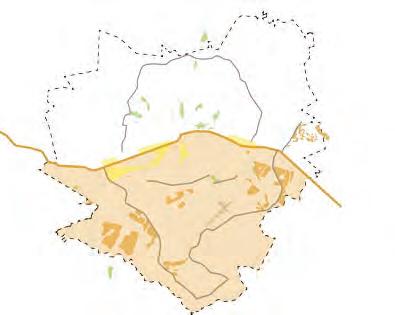

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

CBD

• The Industrial corridor was developed along the railway line in the south

• Informal settlements developed further from employment opportunities and the CBD

PROPOSED MEASURES

COMMERCIAL

• Establish an industrial core closer to the high density and informal settlements

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

COMMERCIAL COMMERCIAL

CBD

INDUSTRY INDUSTRY INDUSTRY

• Link commercial centers with public transit networks; disperse these throughout the city

INDUSTRY

RAIL

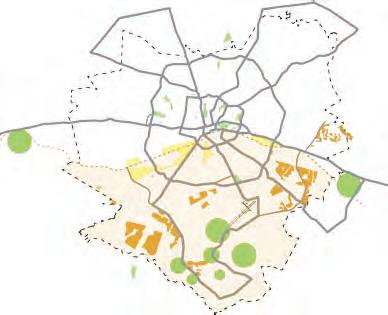

EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS

• There are fairly good protections in place for existing wetlands

• Development and populations are increasing, therefore encroachment on wetlands is becoming a issue

PROPOSED ENVIRONMENTAL MEASURES

• Protect the wetlands; they are important to the health of the watershed

• Protect areas of significant habitat

• Add supplementary pedestrian and bike networks

EXISTING CONDITIONS

• The railway line and industrial areas are a socio-economic divide

• Open space and services are clustered in the northern suburbs, while low-income and informal settlements are clustered in the south

PROPOSED MEASURES

• Provide public transit to all socioeconomic groups

• Create large scale public open space and social attractors in the south and along major public transit routes

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTIONS

PRODUCTIVE AREAS

• Provide public transit to all socioeconomic groups and create large scale public open space and social attractors in the south and along major public transit routes

• Establish industrial cores closer to high density and informal settlements. Link commercial centers with public transit networks throughout the city

• Protect wetlands and add supplementary pedestrian and bike networks

• Develop public Bus Rapid Transit System (BRT) and maintain commuter omni buses with consistent fare structure

LACK OF COMMERCIAL AREAS

HIGH ELEVATION

CBD

POTENTIAL AREAS FOR FUTURE GROWTH

• Future growth should avoid higher elevation areas to alleviate pumping requirements

• Future growth should avoid possible contamination of watersheds that lead to primary city water supply

• Future growth should avoid possible contamination of watersheds taht lead to primary city water supply

• Future growth should avoid areas defined by USAID analysis as having important agricultural soils CLASS

ZIMBABWEANS DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO A CLEAN SUPPLY OF DRINKING WATER.

EMERGING CENTRALITY: CHITUNGWIZA SUSTAINABLE GROWTH BALANCED PROSPERITY

IS A KEY FEATURE OF HARARE’S ECOLOGY.

THE

IN HARARE IS DEPENDANT ON THE FUTURE OF THE CITY’S WETLANDS.

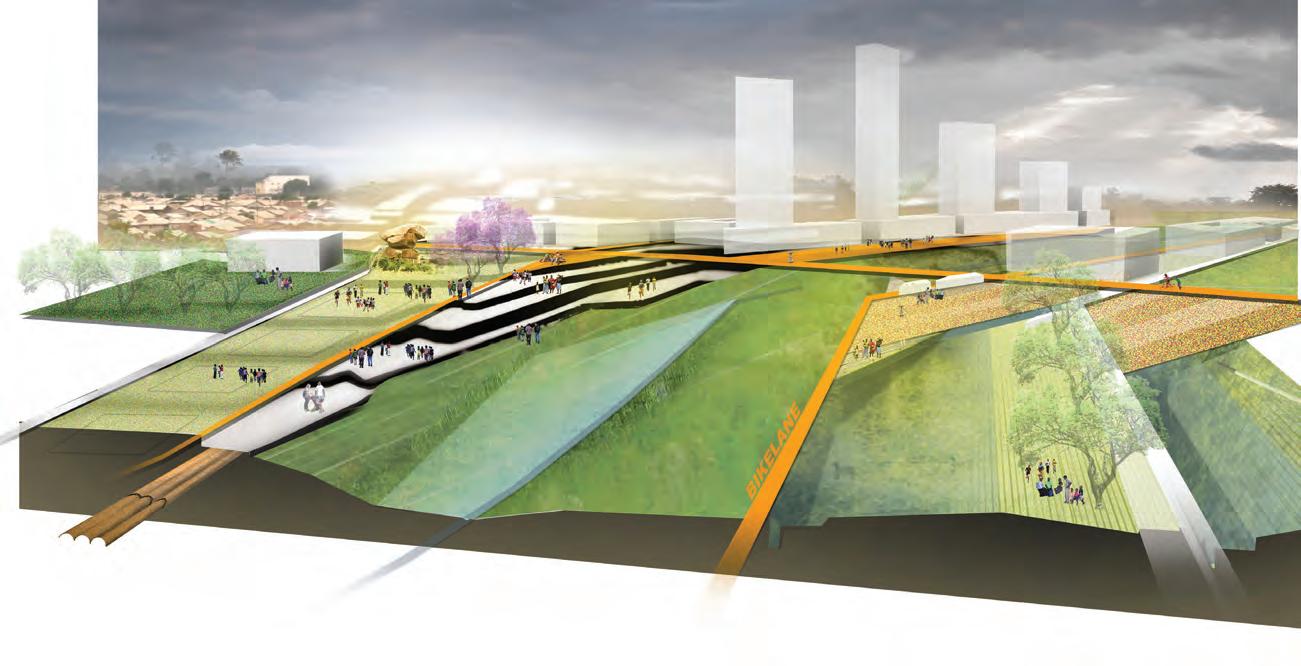

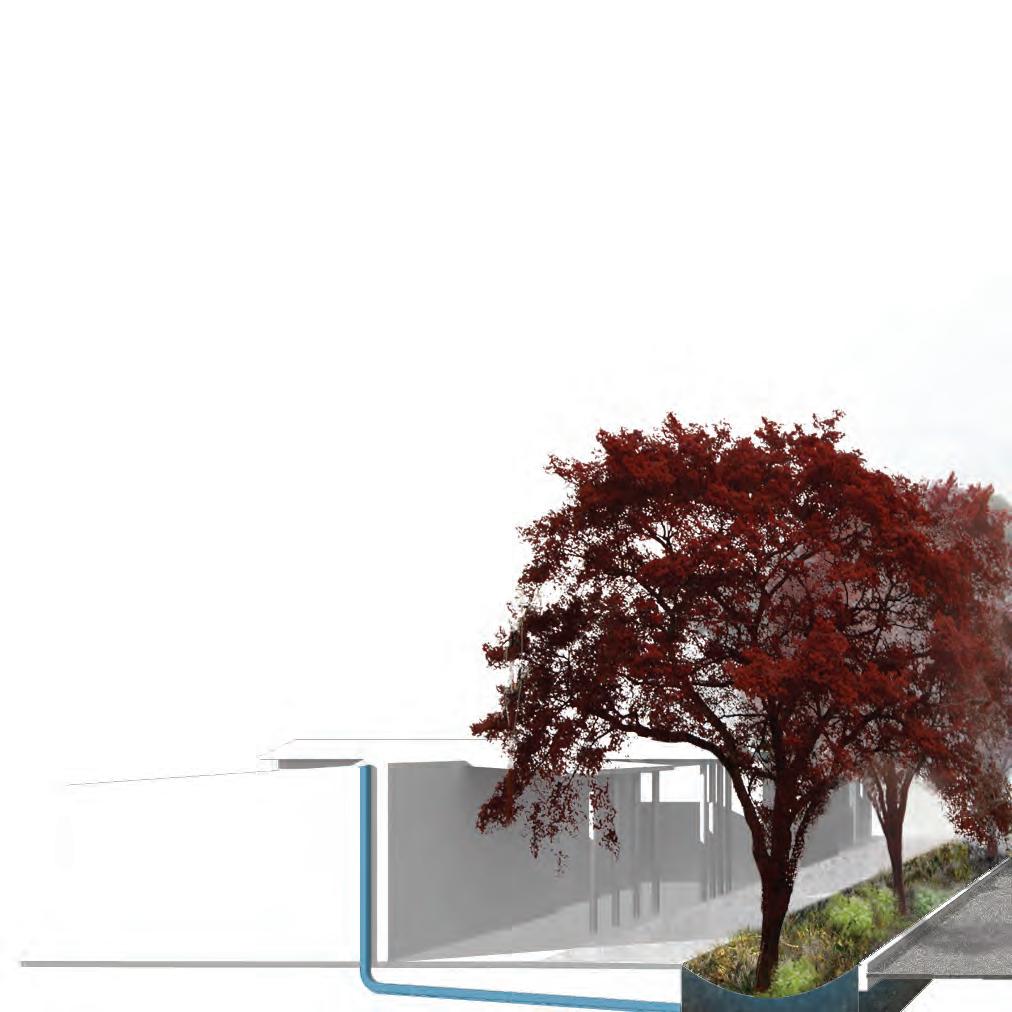

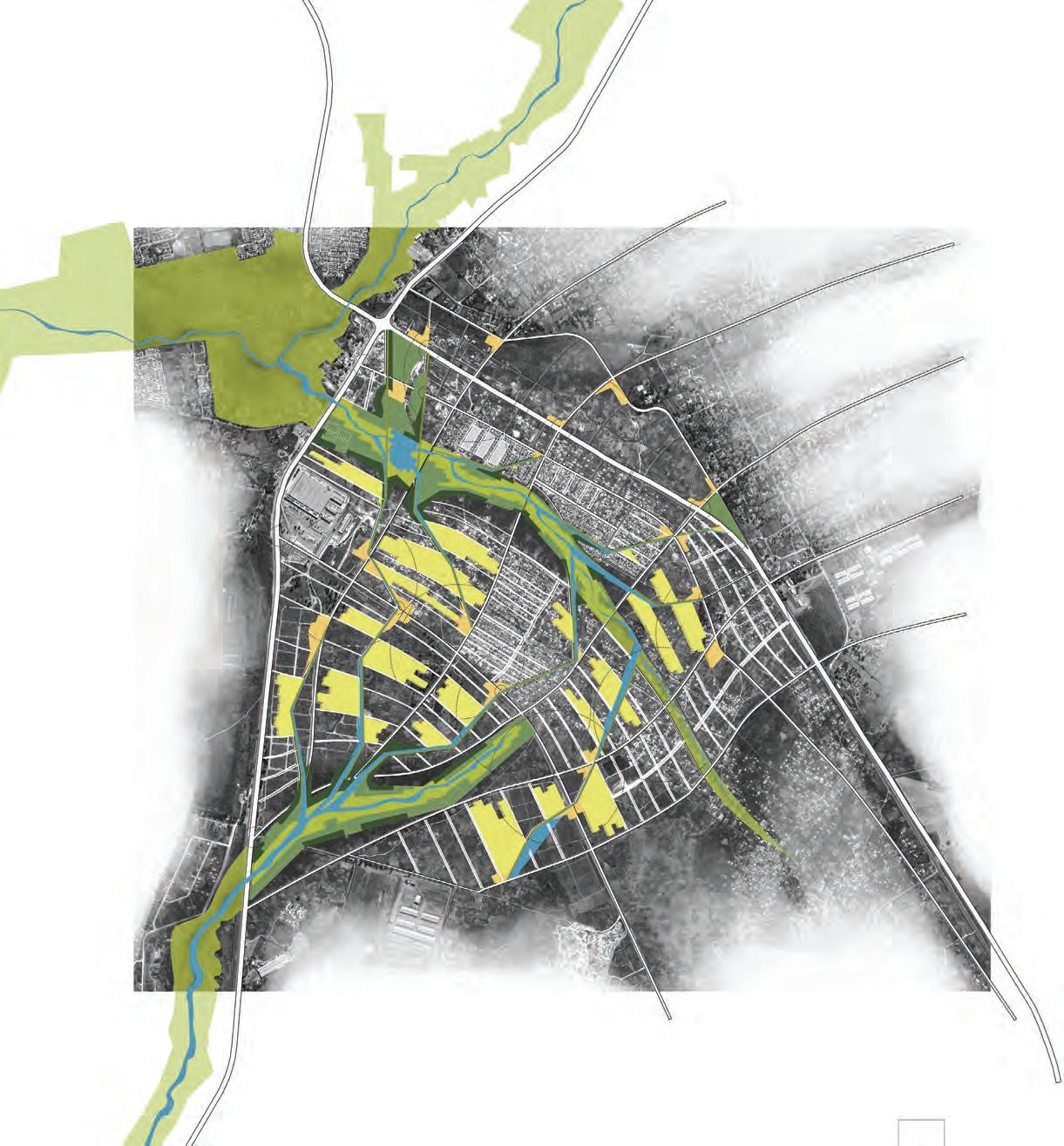

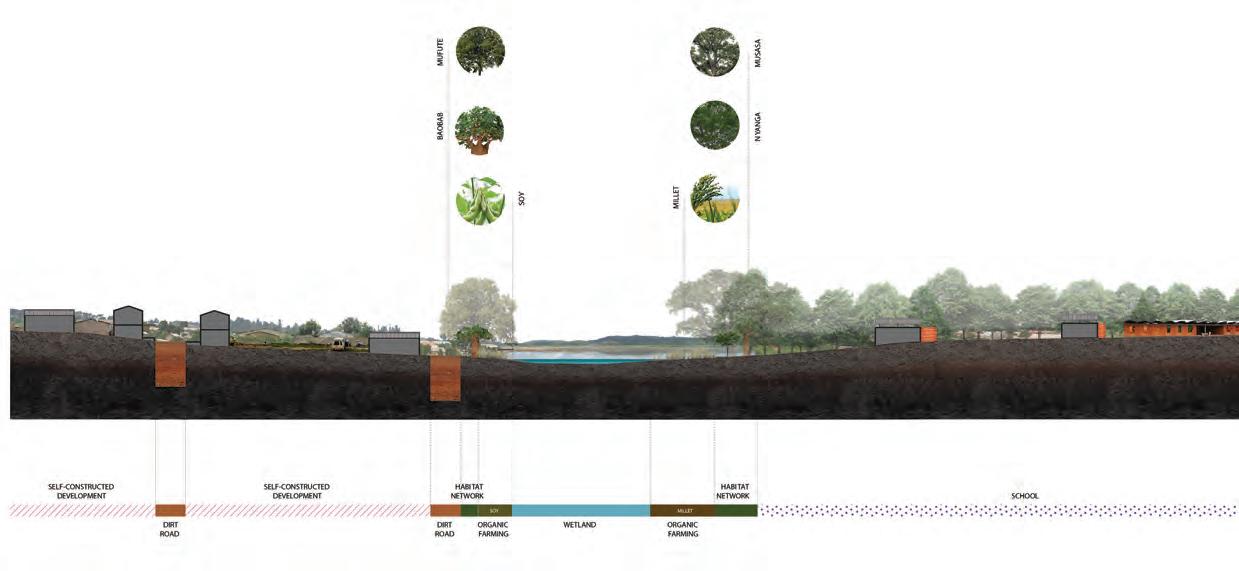

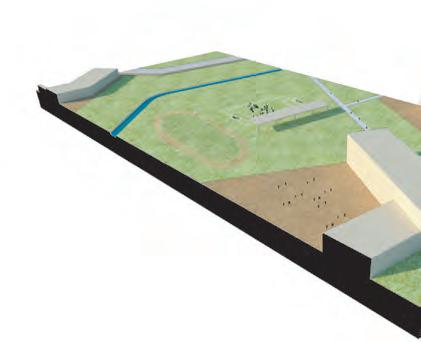

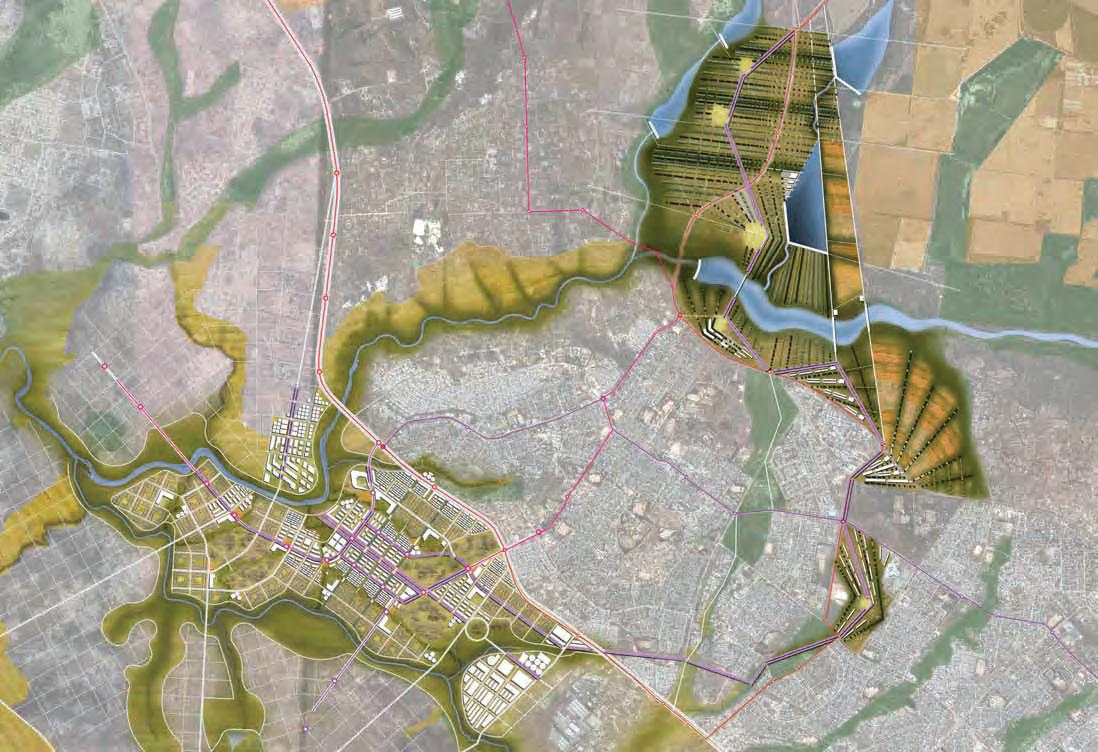

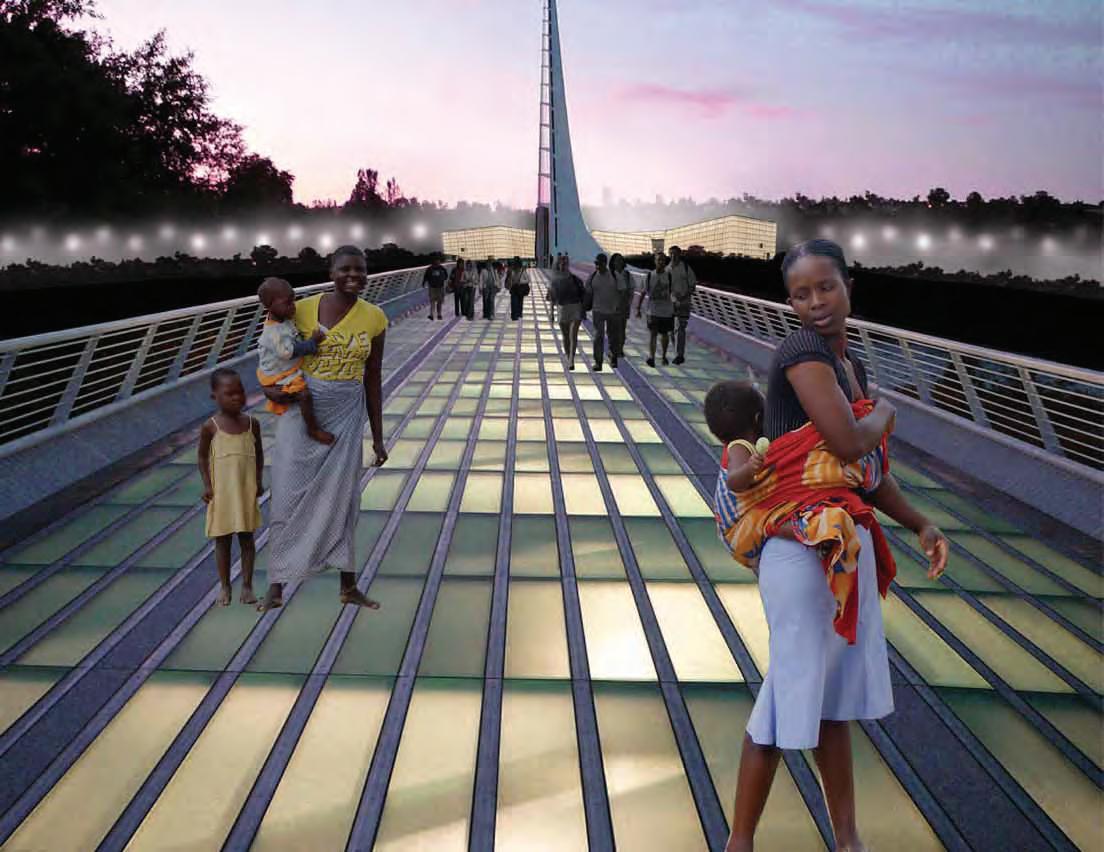

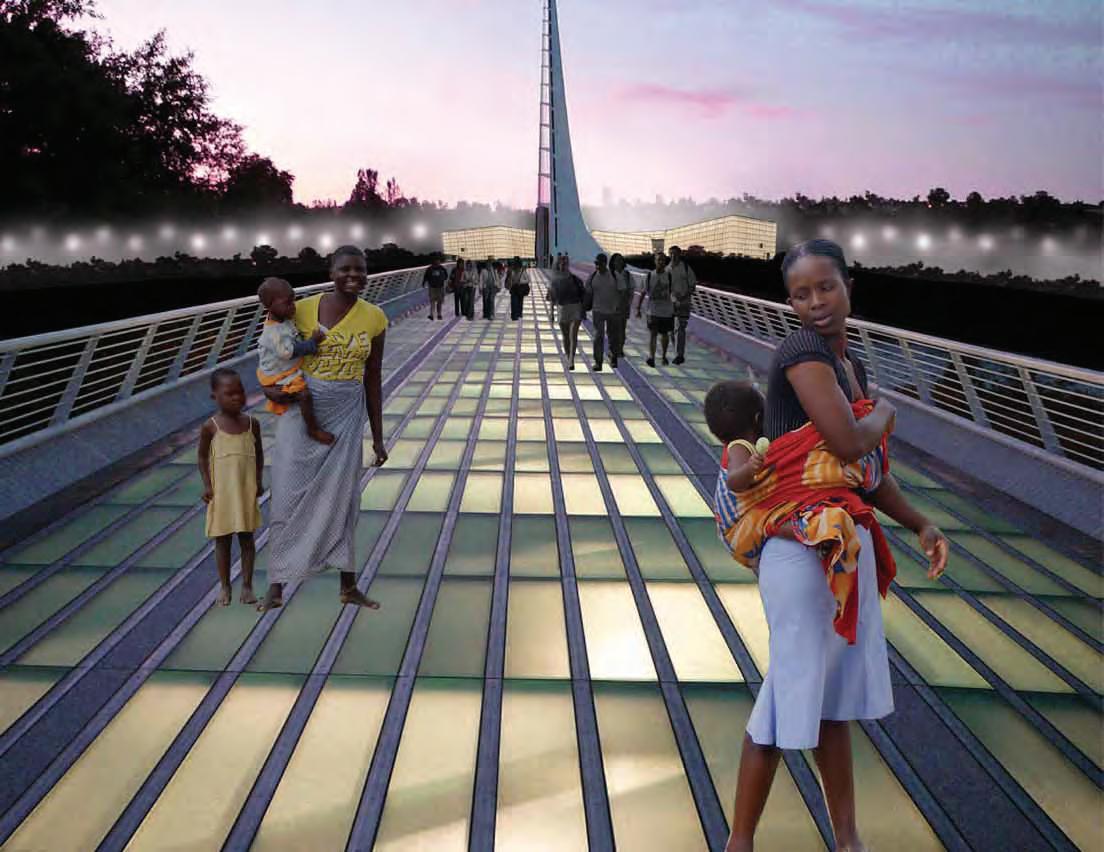

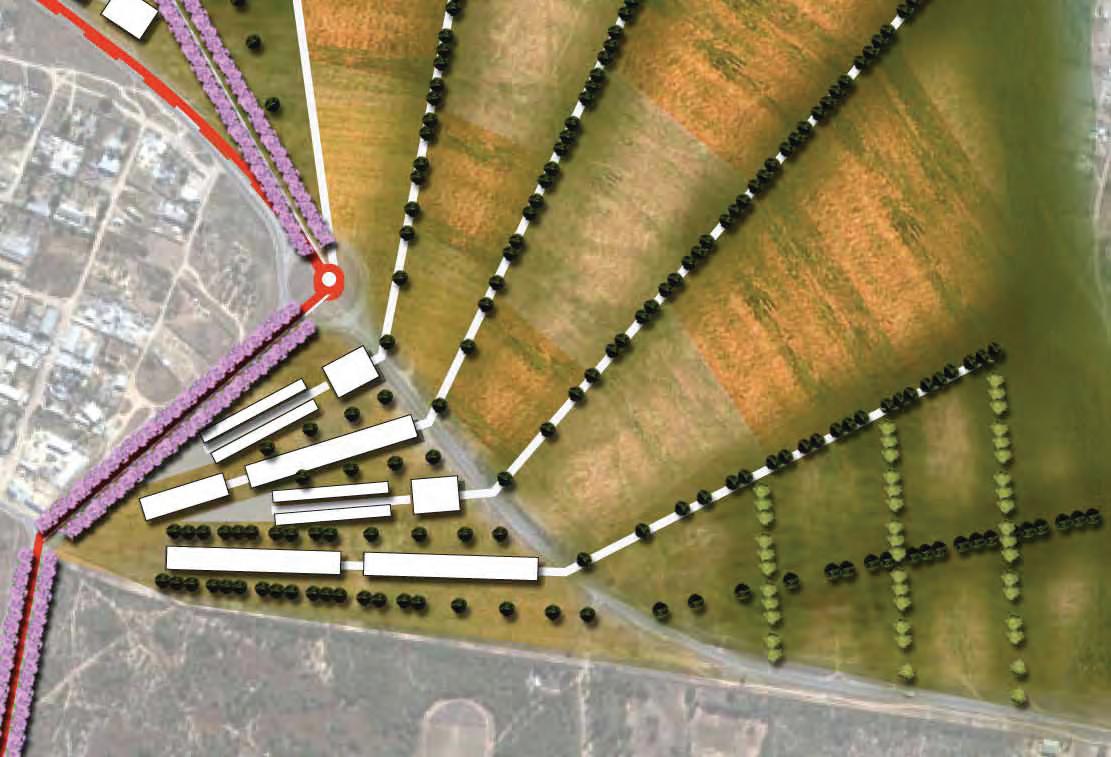

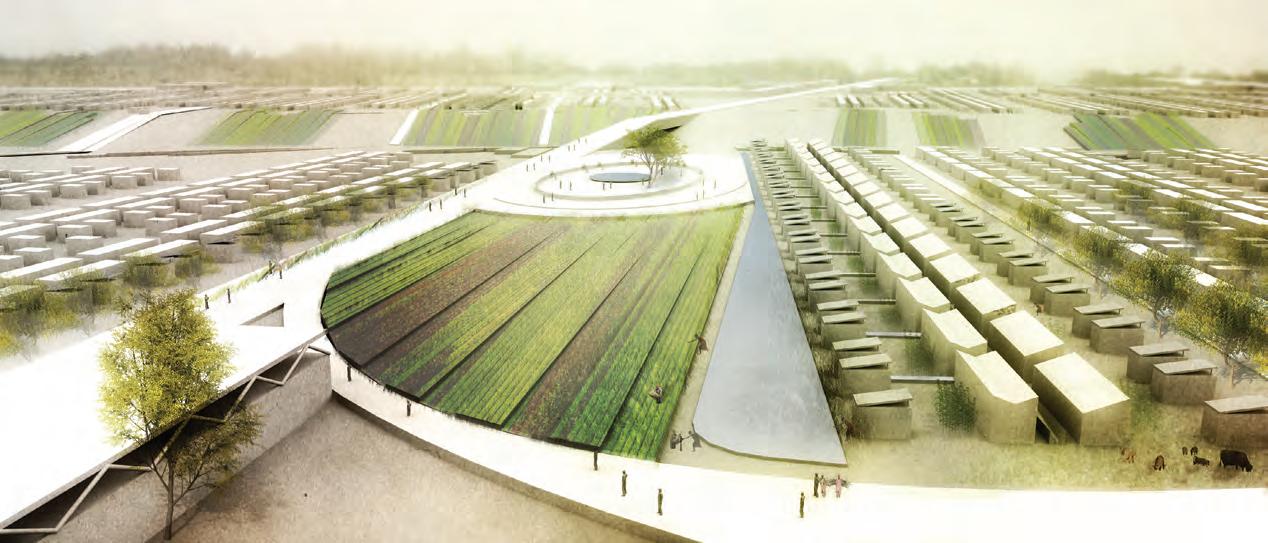

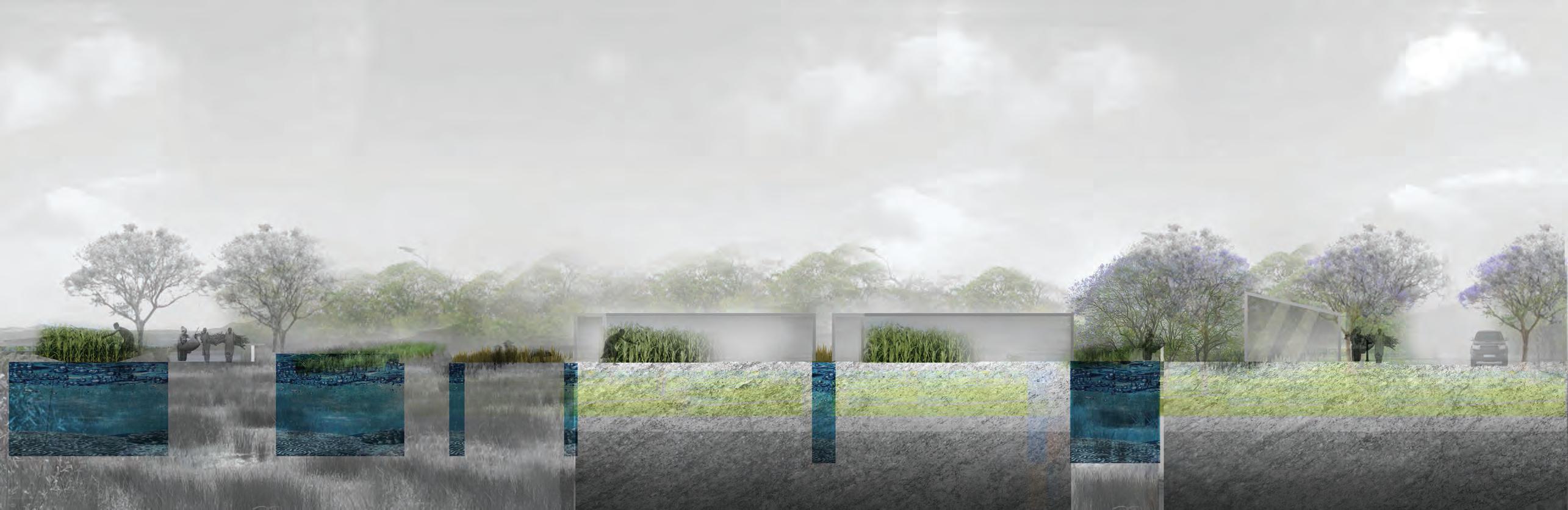

Utilizing the Dambos as an organizing element, this project establishes a new urban centrality west of Harare Airport.

A self-sustaining district with increased activities, densities and programs seeks to diminish the pressure and congestion in Mbare and the CBD. A new seasonally-respondive landscape provides the framework for new industrial, residential and commercial areas.

A proppsal by Chen Lu Fang

MARBOROUGH STW

HATCLIFFE

DONNYBROOK STW

CROWBOROUGH STW

LAKE CHIVERO

FIRLE STW

LEGEND

RUWA STW

NEW RESOVIORS

NEW STW & REMEDIATION

NEW WATER SUPPLY

PRESERVED WETLANDS

WATER CONTAMINATION AREA

SEWAGE TREATMENT WORK (STW)

WATER NETWORK

WATER BODY

MAIN WATER SOURCE

CLEVELAND DAM SEKE & HARAVA DAM PRINCE E.WTW 90,000M3/D MORTON JAFFRAY.WTW 614,000M3/D ZENGEZA STW STW

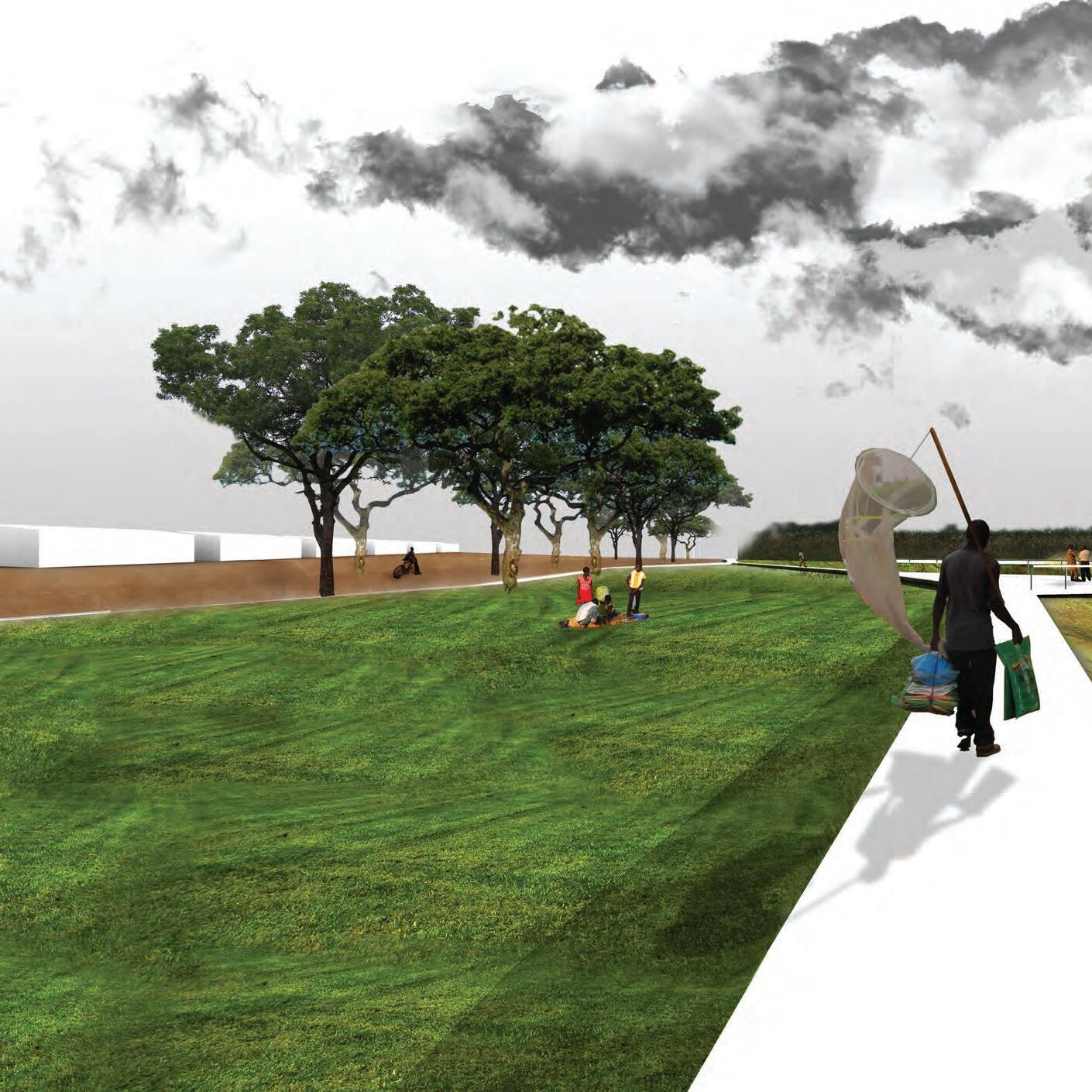

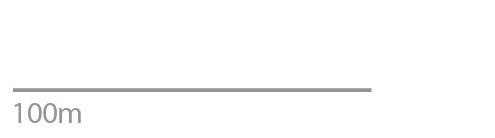

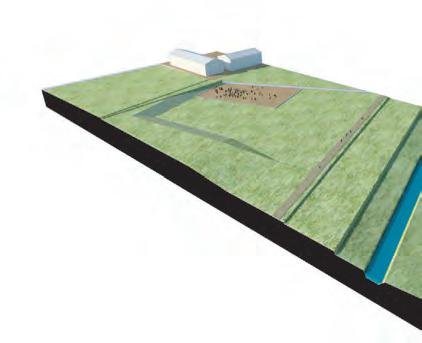

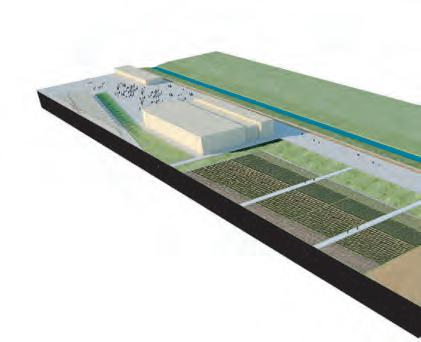

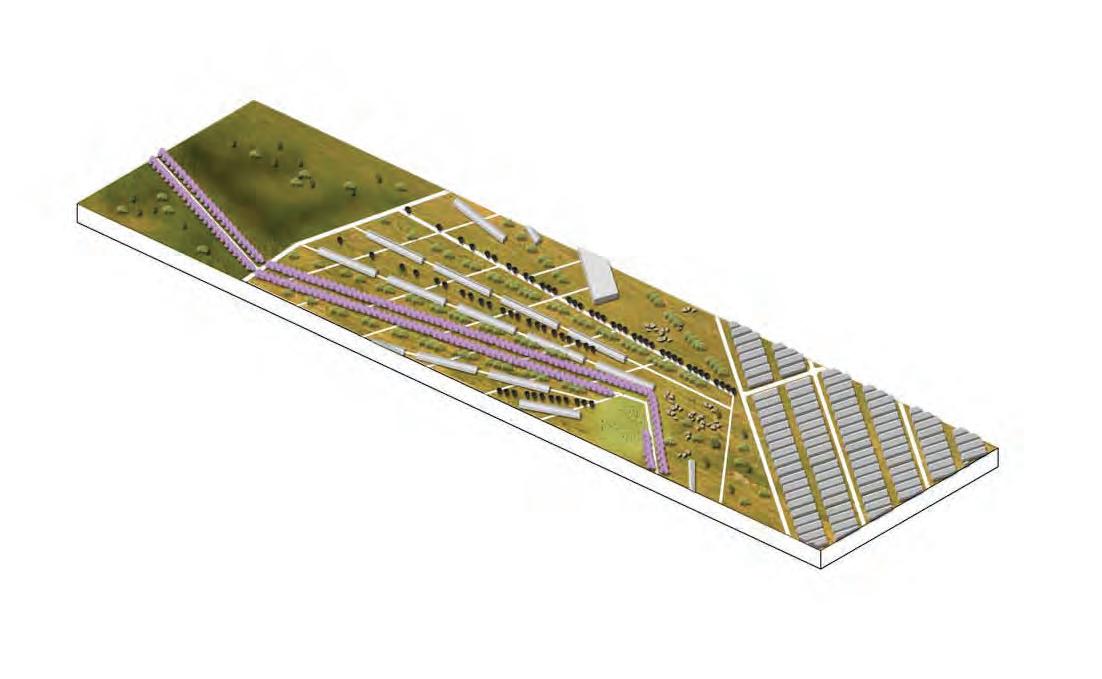

Transportation and mobility are essential to the functioning of all urban areas. When used as an organizing element transportation can foster economic growth.

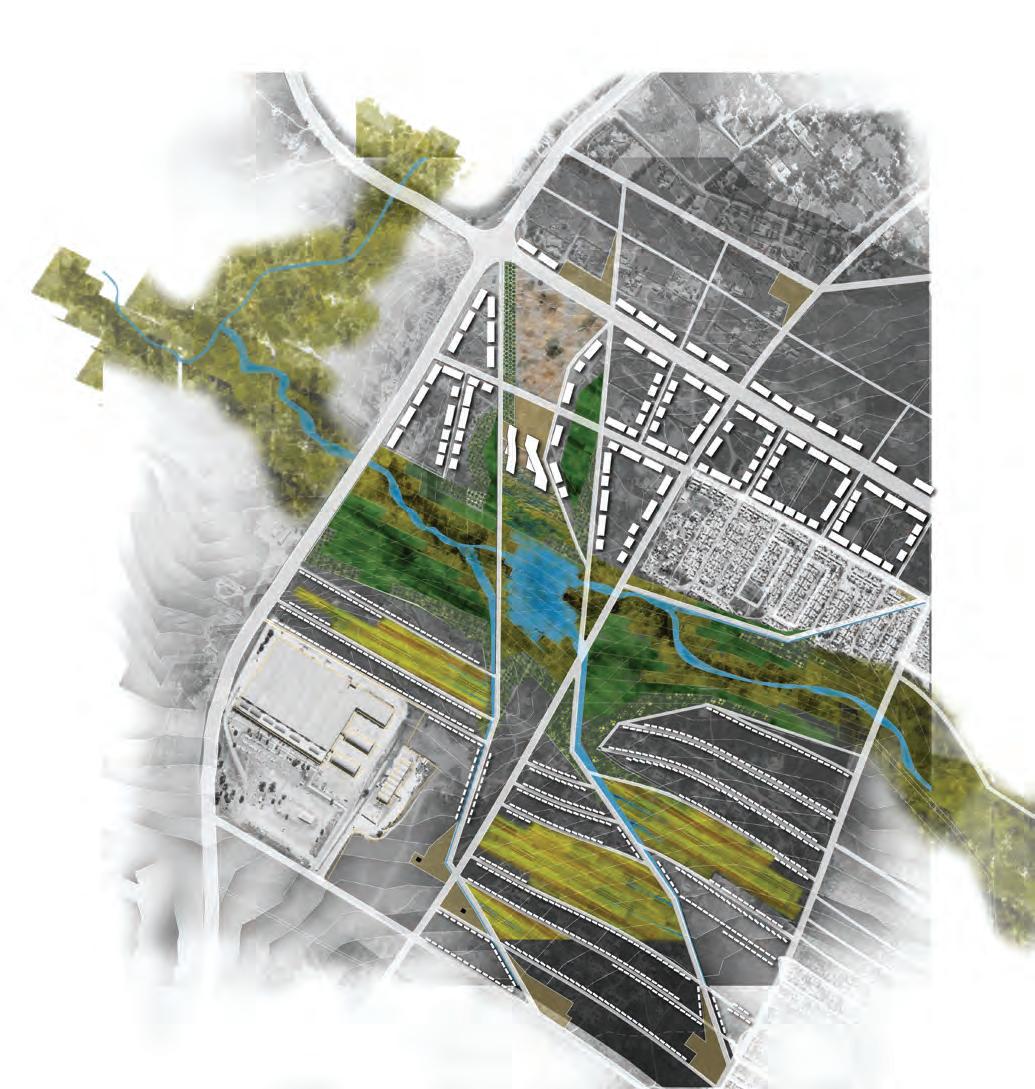

In this project, the proposed network creates an organizing system for ecotourism programs that include job training campuses, reforestation areas and receptor patches for future growth.

A proppsal by Anneliza Carmalt

A proppsal by Anneliza Carmalt

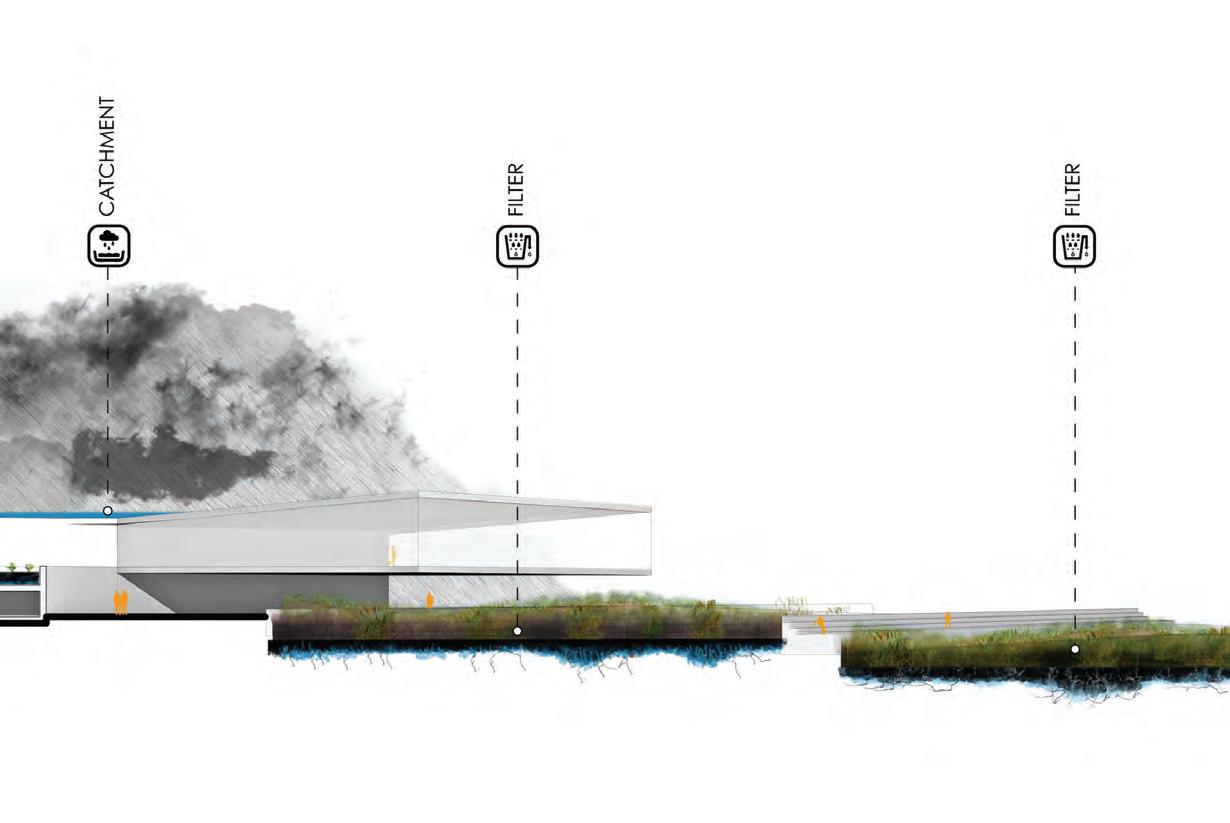

RAINWATER FROM ROOFS COLLECTS IN GARDENS ALONG THE STREETS

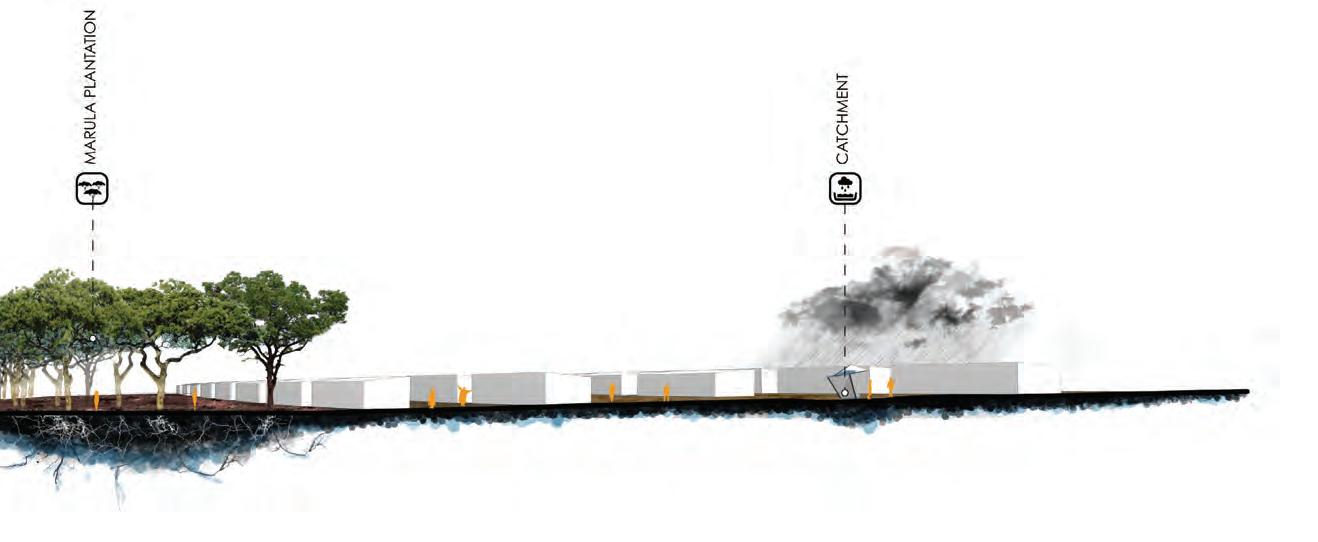

JOB TRAINING CAMPUS ASSOCIATED WITH TOURIST INDUSTRY AND CULTIVATED MARULA PRODUCTION.

MARULA PLANTATION CREATES PRODUCTIVE ECONOMY. DEMONSTRATIVE PLANTING FOR TOURISTS.

MARULA ACTS AS INTERCEPTOR FROM INFORMAL AGRICULTURAL RUN-OFF AND BENEFITS FROM FERTILIZER NUTRIENTS WHILE FILTERING WATER FLOWING INTO DAMBO.

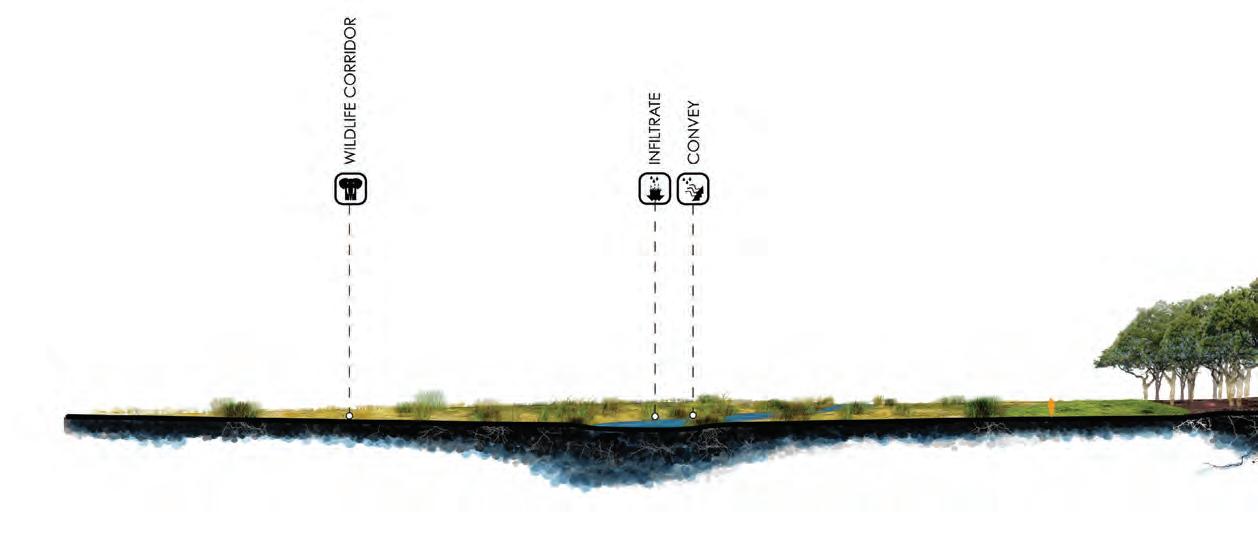

NATIVE VEGETATION IS MAINTAINED AS A RIPARIAN BUFFER FOR A MINIMUM OF 30 METERS TO EITHER SIDE OF THE DAMBO.

OPEN SPACE IS MAINTAINED FOR PUBLIC RECREATION AND/OR MINI-SAFARI TRAILS FOR TOURISTS. MARULAS ATTRACT WILDLIFE SUCH AS BIRDS, ZEBRAS, AND ELEPHANTS.

RECEPTOR PATCHES FOR INFORMAL RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT.

In this project a new system of organization in Hopley Farm allows this residential area to manage and filter rainwater. It is stored and purified for agriculture and human consumption. Thus creating a community independant of the grid.

Self-sufficiency acts as a basis for the secondary layer of development based on ecotourism, therefore creating economic opportunities for the residents.

A proppsal by Taylor Burgess

A proppsal by Taylor Burgess

KEY TAKE-AWAYS:

1. PROTECTION OF DAMBOS

2. GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

3. LANDSCAPE-DRIVEN PROGRAM

4. LANDSCAPE-RELATED INDUSTRIES

SMART GROWTH STRATEGIES CAN CREATE TRANSPORTATION

THAT BETTER SERVE MORE PEOPLE WHILE FOSTERING ECONOMIC VITALITY FOR BOTH BUSINESSES AND COMMUNITIES

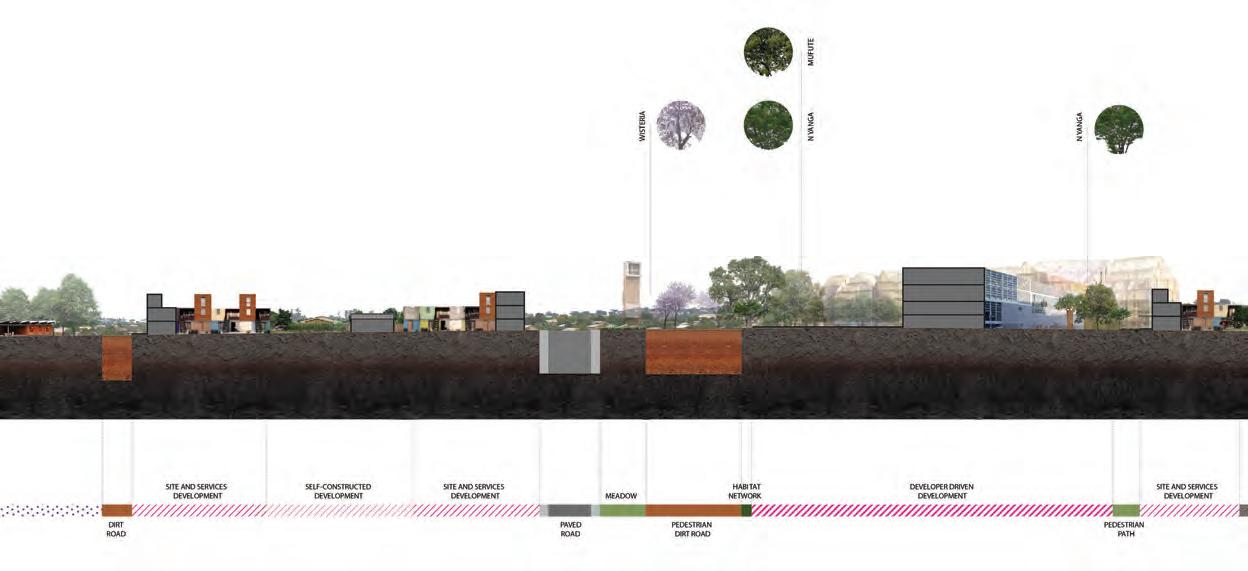

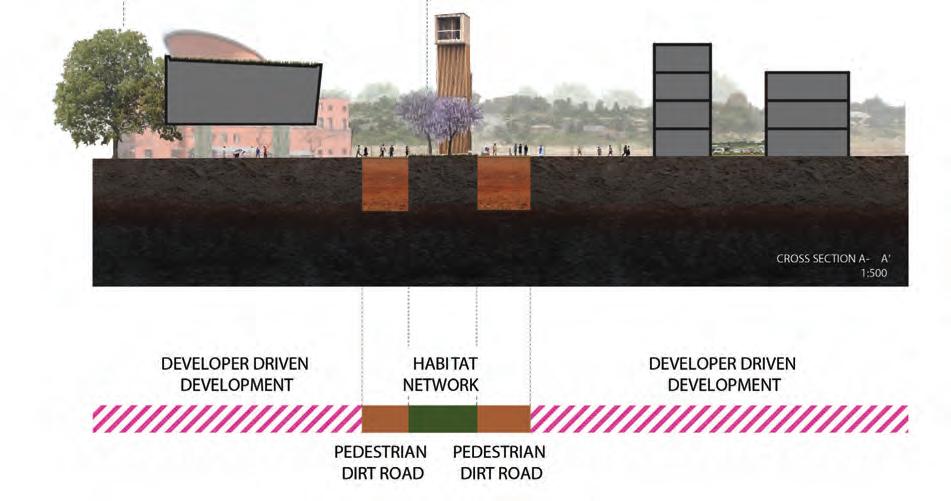

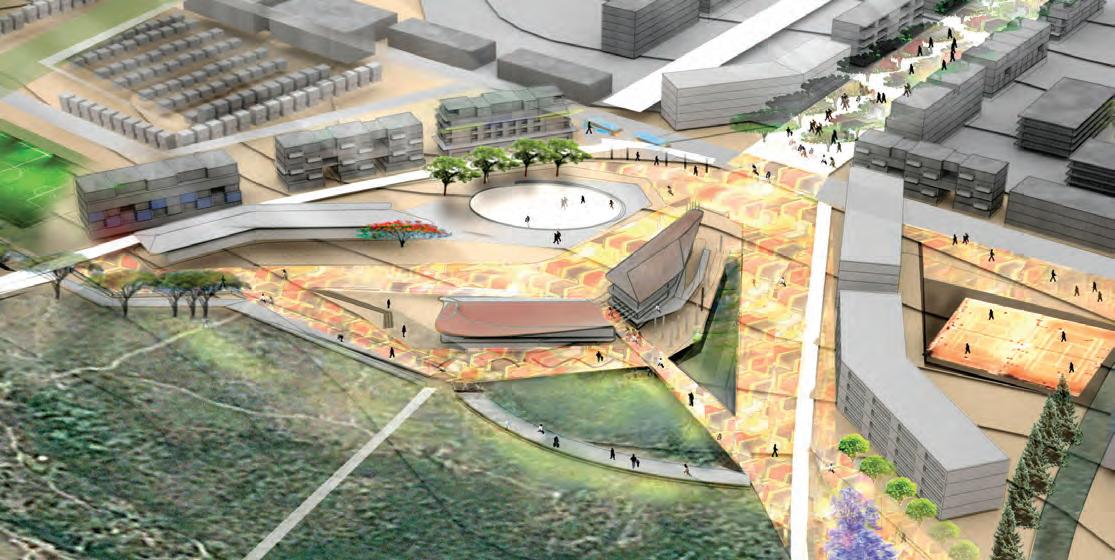

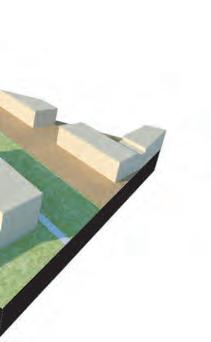

Commercial Development is one of the drivers of growth of any city. In this project private development acts as a catalyst for new urban growth. Throughout the project amenities such as open space, recreational facilities and markets are deployed to foster sustainable urban living.

A proppsal by Daniel Saenz

A proppsal by Daniel Saenz

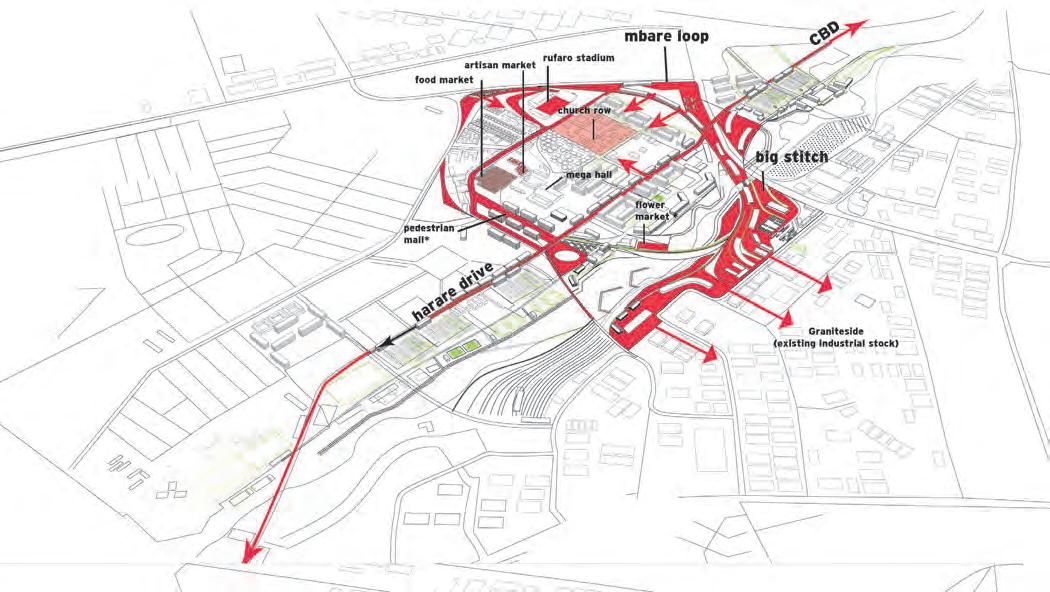

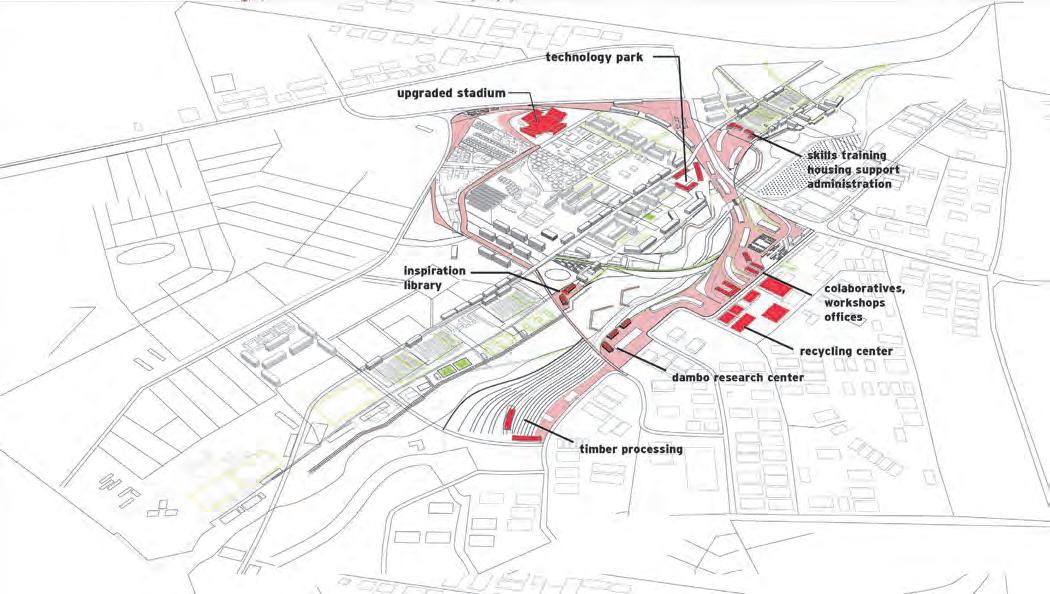

The Mbare Area of Harare can be considered the cultural and economic motor of the city. In this project Mbare is revitalized as a central commercial, recreational and residential node. A loop connecting housing to commercial development and landscape remediation seeks to make Mbare a commercial hub for the 21st century.

A proppsal by Anoop Patel

A proppsal by Anoop Patel

housing cells : framed + retrofit, shared water management

20 commerce home bases

70 row home bases

2 dense blocks

assisted construction: base provided residential rowhomes

existing population est. 400 - 800 000

commercial rowhomes

overcrowding:

supported : ~15,000 over capacity: 10 000 low cost housing waitlist: 500,000

agri - strip / back yards

on site water management 70 row

20 commercial housing bases

frame

mixed use

harare drive : planned density

harare drive + mbare loop

new residents = 20 - 25 000

HARARE RD

HARARE RD

This proposal focuses on Mbares, transportation, open spaces and water infrastructure. These are bundled to retrofit this area of the city. A system of train and bus stations are complemented by markets, high density housing and open spaces like promenades to provide residents with civic, productive and commercial spaces.

Mu u M lt t l ii - mo m o da a l T Tr r an n a sp s or r ta a ti t i on o Ce C nt n er e r

SIMON MAZORODZERD CRIPPSRD

Ha H a ra r a re r e T ra a r in n i S ta t a ti t i on n o

A A

B

Ur U r ba b a n Fa F a rm m

94

Tr T r ad a d in i n g Sc S ho h ol o l / B us s u in i n es s e s In n I cu c u ba b a to t o r Ca C a mp m u us s B

C Ci v vi c Co C o re r e Ho o H sp s p it t al a

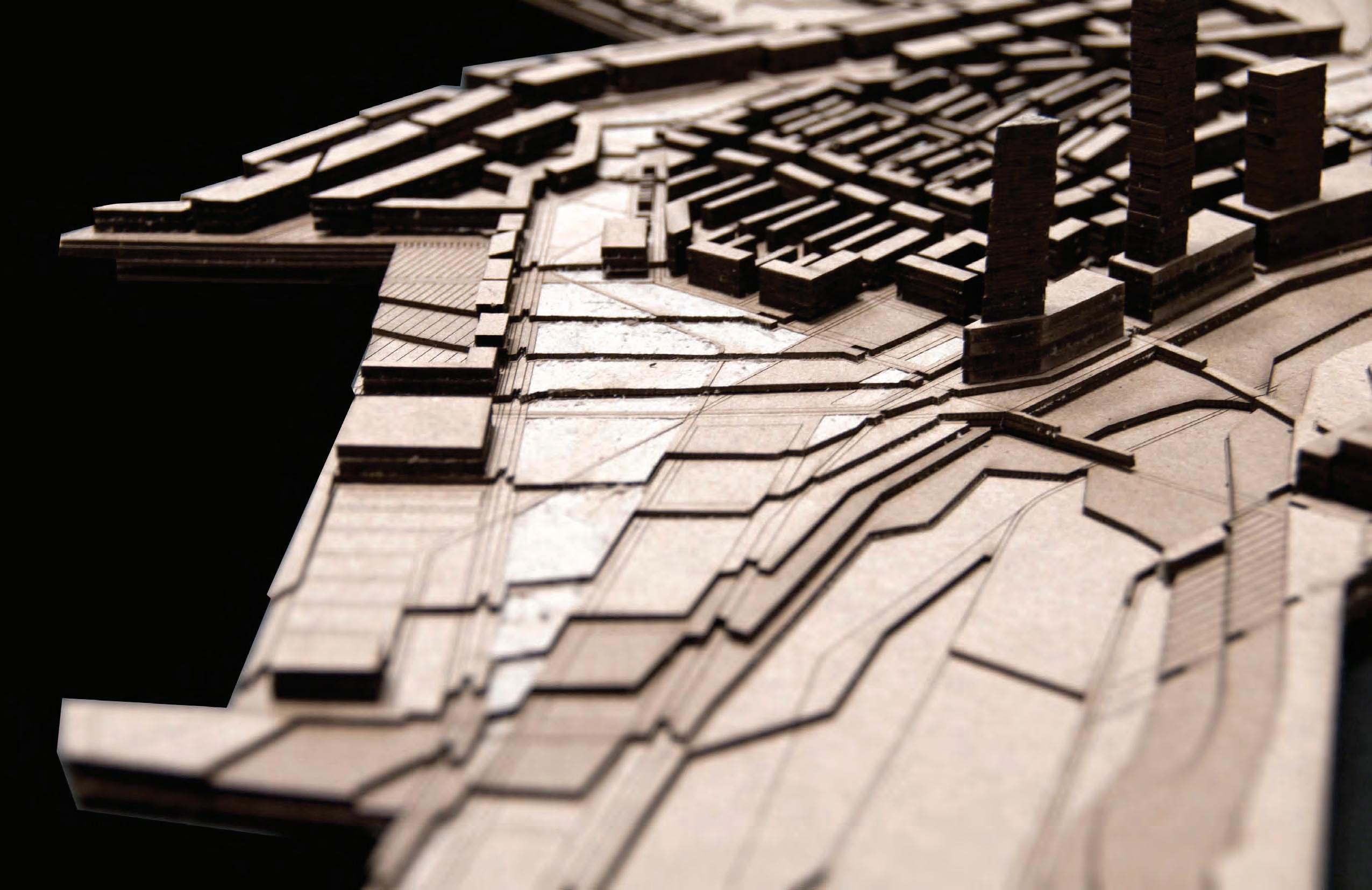

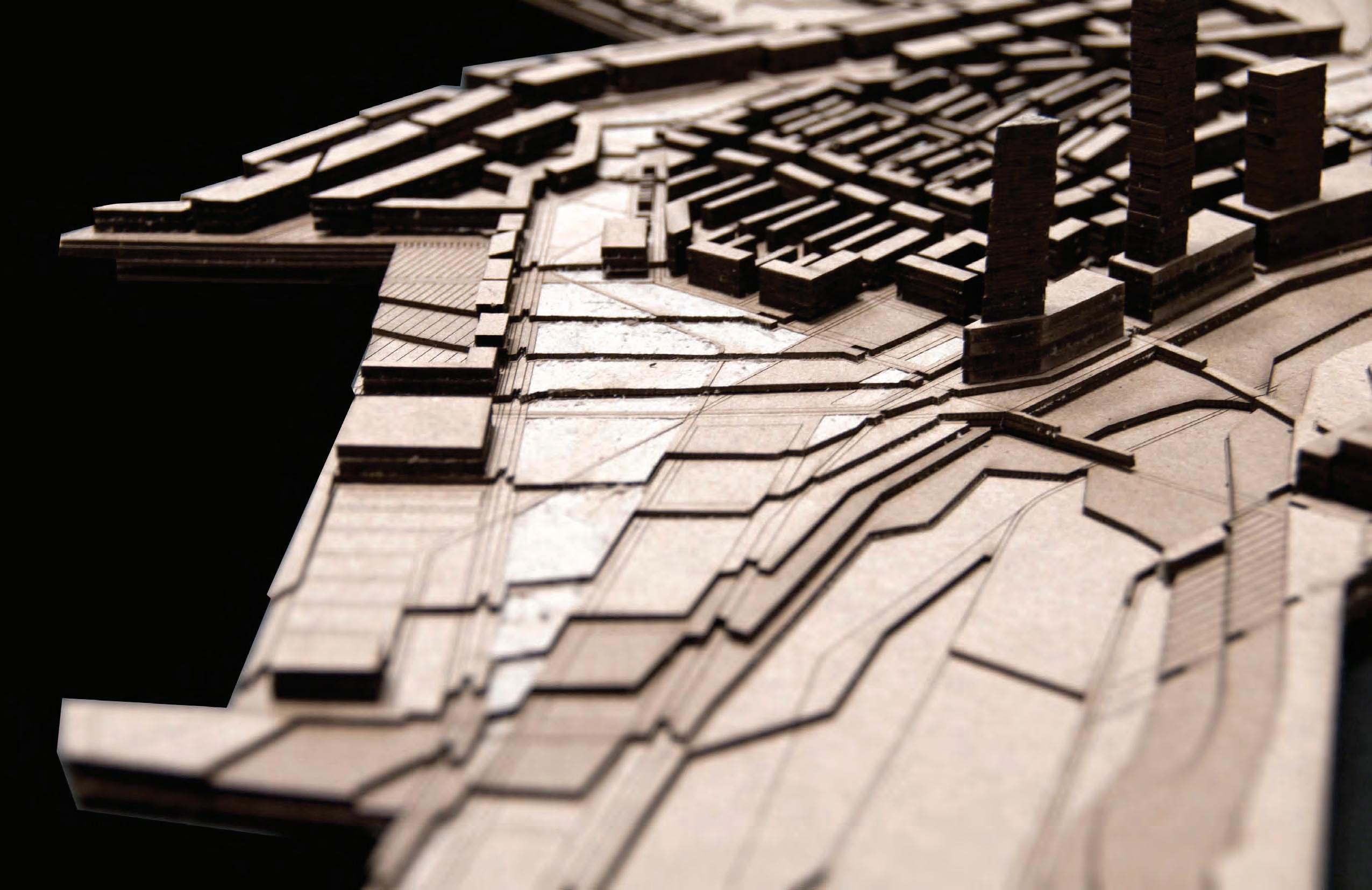

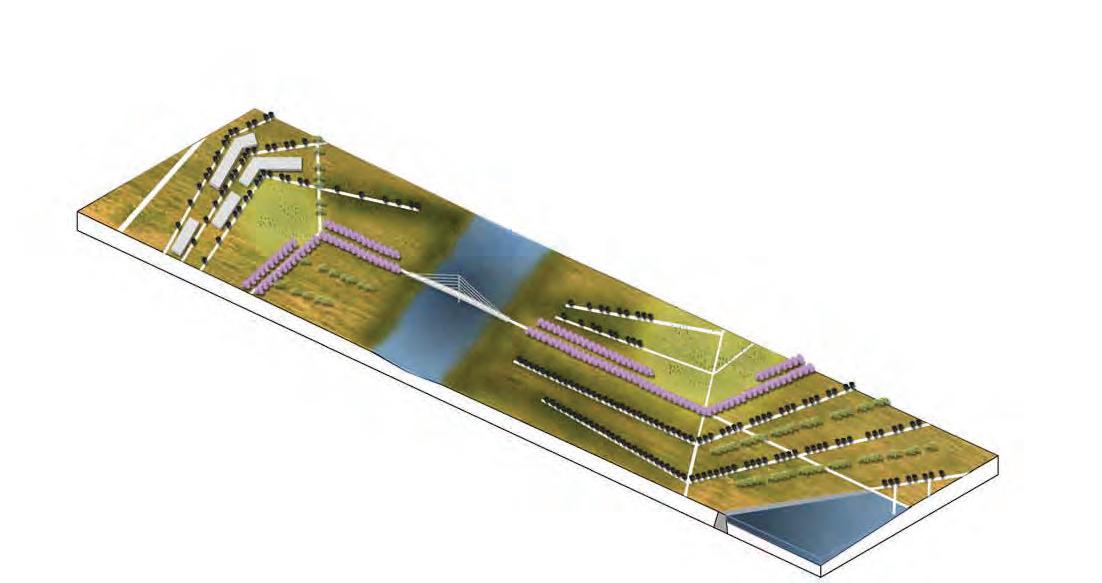

Chitungwiza maximizes urban opportunities and offers the best location for supporting future population growth. The 2 following proposals look at ways to unlock the rich potentials of this vibrant dormitory town.

A proppsal by Peter Barnard & Meghan Talarowsky• Identify, map and preserve existing wetlands

• Establish an agricultural boundary to define the growth boundary of the municipality

• Connect Chitungwiza to Harare CBD via dedicated Bus Rapid Transit Line (BRT)

KEY

Existing development

Wetlands/ Veli/ Dambos Agriculture BRT line to Harare CBD

Local BRT lines

Pedestrian/ Bicycle lanes

RESEARCH UNIVERSITY

FESTIVAL FIELDS + PUBLIC SPACE

MUSEUM COMPLEX CRAFT MANUFACTURING COMPLEX AGRICULTURAL PROCESSING MARKET

BUSINESS CORE BALANCING ROCK PARK 101

REGIONAL MARKETPLACE

• Define Chitungwizas new commercial core with BRT loop through the existing commercial center

• Connect the new commercial core to the existing shopping mall and expansion areas

• Complete the local BRT loops; these will structure future growth and support the new commercial core

• Interconnect BRT, wetlands and agriculture with a bicycle/ pedestrican network

Existing development KEY

Wetlands/ Veli/ Dambos Agriculture BRT line to Harare CBD

Local BRT lines

Pedestrian/ Bicycle lanes

FESTIVAL FIELD

MUSEUM COMPLEX

FESTIVAL FIELD

MUSEUM COMPLEX

A proppsal by Meghan Talarowsky

A proppsal by Meghan Talarowsky

FESTIVALPEDESTRIANAXIS

EXISTINGWETLAND

BRTARTERIAL

EXISTINGMALL

FESTIVALFIELD

FESTIVALFIELD

PEDESTRIANAXIS

EXISTINGCITY

AGRICULTURE FOR LOCAL PROCESSING AND CONSUMPTION

A proppsal by Peter Barnard

A proppsal by Peter Barnard

RAMBLA

SCHOOL

RAMBLA

SCHOOL

BASIC LOT LAYOUTS

COMMUNAL CENTER

EXISTING UNIVERSITY CONNECTED BACK YARDS

CONSOLIDATED HOUSING

AGRICULTURE

BASIC HOUSING UNIT DIRT ROADRAMBLA

RECYCLING CENTER

TRASH PICKERS SOURT OUT RECYLABLES

TEMPORARY ARGICULTRUALFIELD

ANAROBIC BIODIGESTER

DIGESTATE

KEY TAKE-AWAYS:

1. DECENTRALIZATION

2. NEW RESILIENT DISTRICTS

3. MIXED-USED NEIGHBORHOODS

4. TRANSIT-ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT

5. IDEA AND INNOVATION AREAS

As the population increases within and adjacent to metropolitan boundaries, the number of self-constructed communities multiplies. African cities are increasingly at the forefront of this urban phenomenon where the numbers of informal growth are nothing short of gigantic. In the 21st century informality will become the new normal, and as such, design disciplines and academic institutions are beginning to pay attention to this new form of rapid urbanization.

The University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Landscape Architecture has a long held tradition of being at the forefront of inquiry into multiscalar and multidisciplinary research as it pertains to landscape design. Central to this is the investigation of landscape systems within urban areas and how they can interact so as to create more robust and resilient ways of urbanization. Landscape is no longer an afterthought but a driving tool in urban generation. With this idea in mind the Harare Studio was launched as a testing bed of ideas for a city like Harare that is experiencing informal growth in a unique environmental stage.

The phenomena of informal growth was tackled by the studio as a central theme in reorganizing the future of the city. Informality was not seen as a problem, but as an opportunity to explore new ways in which services could be provided for poor communities through landscape armature strategies that coupled economic, social and environmental benefits. The traditional way of engaging with the

OUT OF NECESSITY, CITIES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES ARE BECOMING INCREASINGLY INFORMAL. CONTINUOUS MIGRATION FROM THE COUNTRYSIDE PLACES MORE PRESSURE ON THE CITY TO PROVIDE BASIC NEEDS, SERVICES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THOSE WHO FLOCK TO THESE CITIES IN SEARCH OF BETTER LIVES.

informal city through retroactive approaches, (fixing what exists without catering for what is to come) was abandoned. Instead, the Harare Studio took a different approach by looking at the informal city preemptively, that is,designing for the future growth of these areas by bundling sites and services in a way that addresses the arising needs of these communities.

Landscape, in emerging cities, is usually an afterthought, a plane that gets conquered by human intervention. The need for shelter is more important than establishing a dialogue between what gets built and where to build. Yet landscape can become the incubator for disaster when it is ignored. As such Harare has a unique relationship to its dambos and to its agriculture, both conditions that should be addressed as starting points an endeavor to forecast growth in the informal city. These two factors can become generators of new relationships between building and site, a way to bring the informal city up to par with the formal city that surrounds it. It is a leveling of the playing field.

In designing for the informal city, existing conditions are as important as what any new proposals intend to implement. Strong social capital and economic

models are deeply embedded in the way that informal dwellers conduct their daily routines. Therefore it is essential to incorporate as much of the existing logic into what the future vision for an informal settlement proposes. Simple occupation patterns like paths, nodes and the placement of houses can reveal a rich palette of tools from which the designer can operate. These patterns emerge out of a deep informal order, carefully assembled by the dwellers. By understanding where things occur, and why they occur there we can begin to understand informality in a new way. Not as a problem, but as a different type of neighborhood, albeit one that requires extra programmatic additions to complement the richness of the informal site.

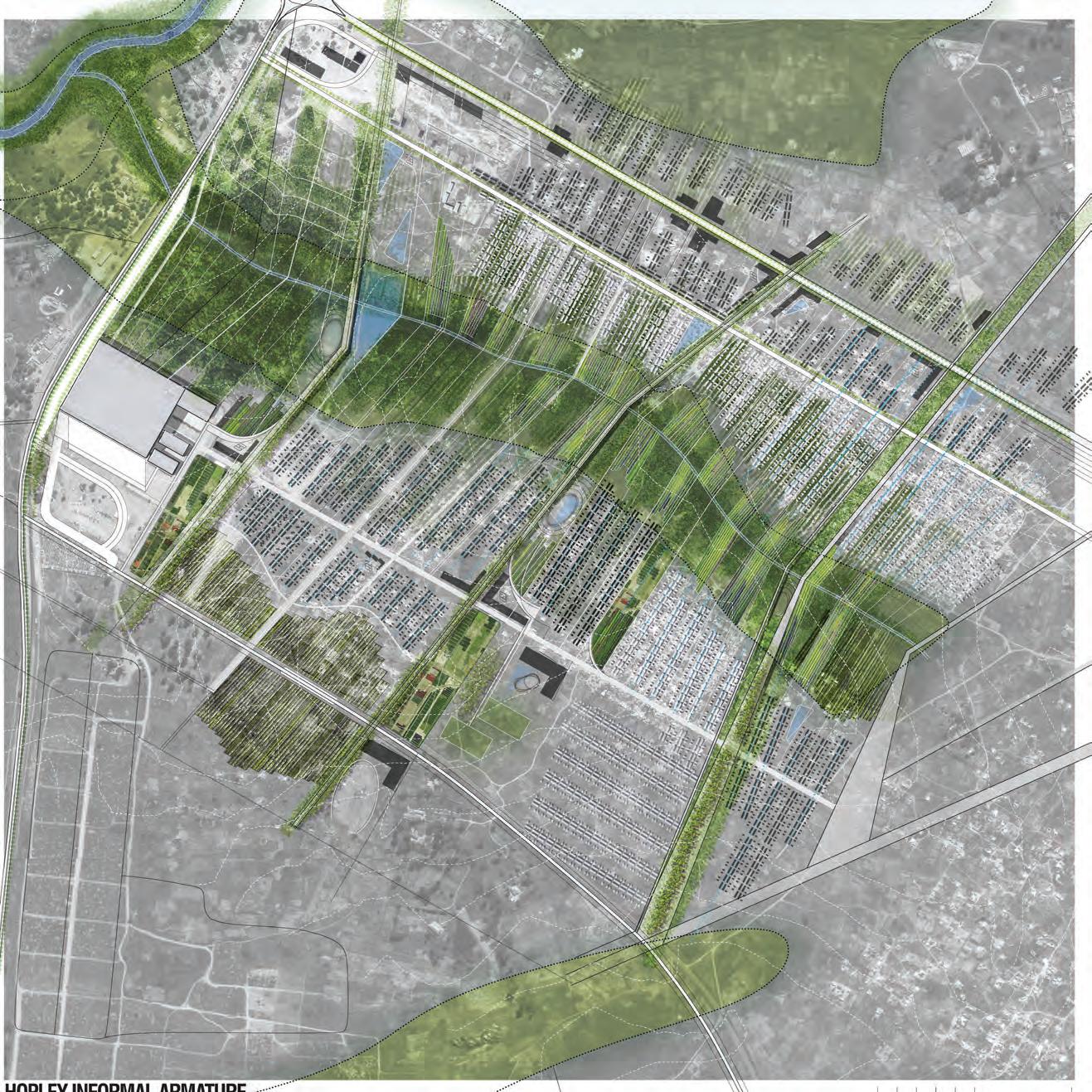

With this in mind, the following projects establish a framework that develop ideas from the existing logic of the Hopley Farm settlement. The dambo and the nodal path system become centerpieces for the establishment of a new landscape framework and programmatic hybrids that preemptively address future growth. In these scenarios landscape systems are as important as the future self-built homes since they provide ecological, economical and social benefit. These benefits elevate an informal area like Hopley Farm into a more coherent, humane and sustainable urbanism.

LANDSCAPE, IN EMERGING CITIES, IS USUALLY AN AFTERTHOUGHT, A PLANE THAT GETS CONQUERED BY HUMAN INTERVENTION.

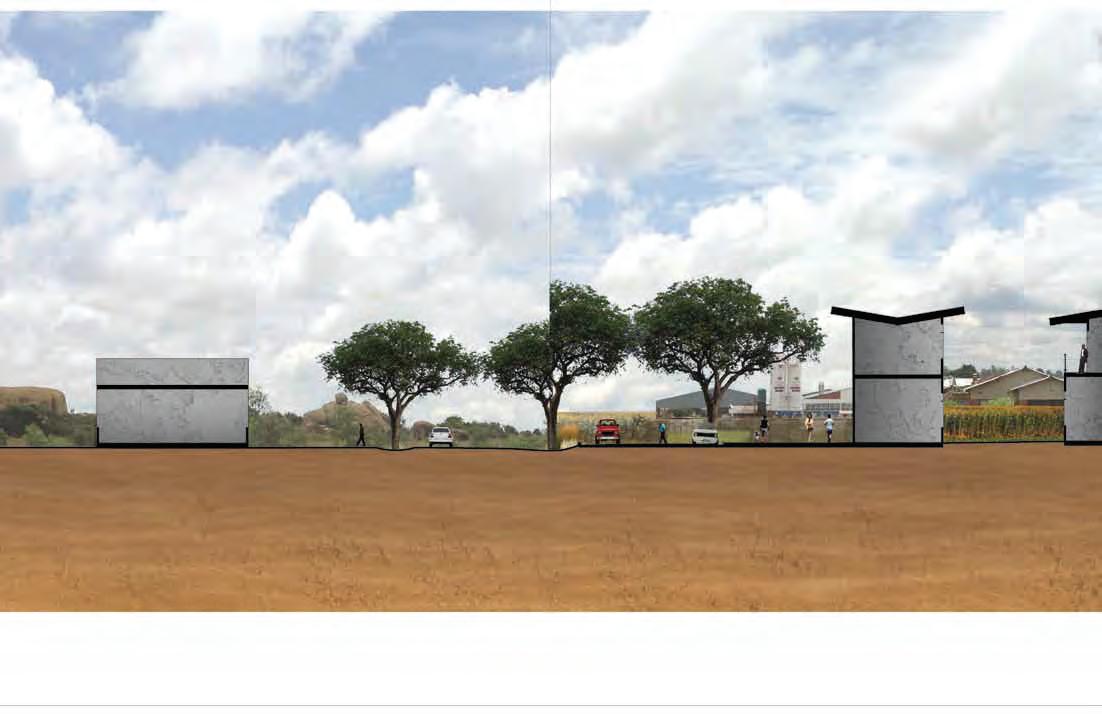

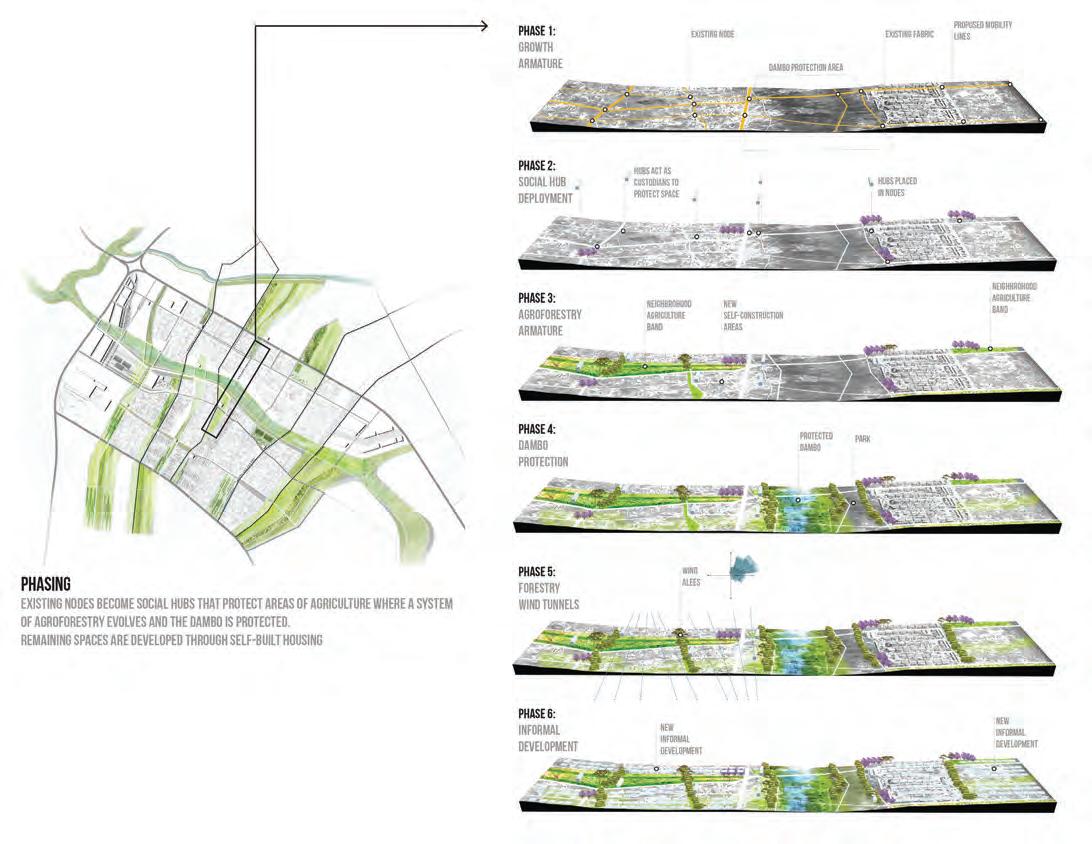

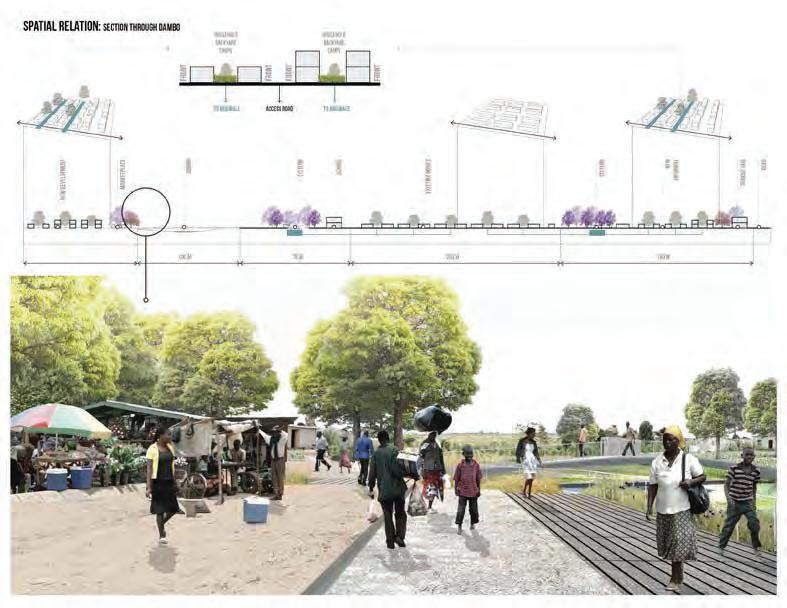

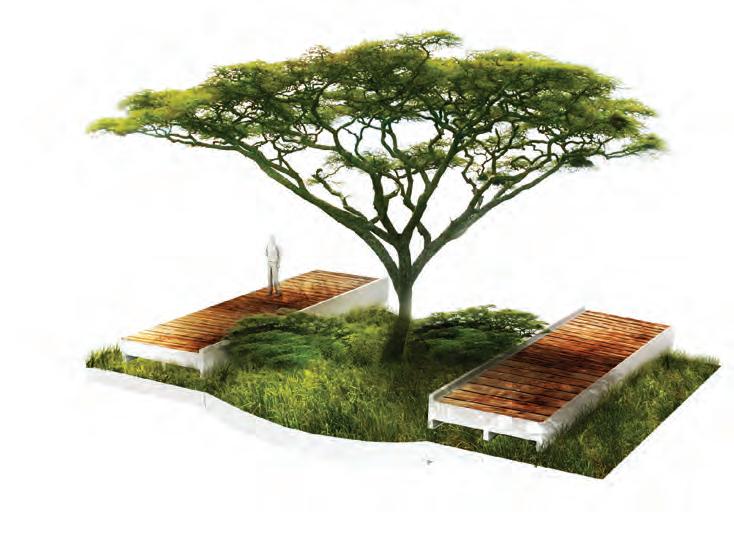

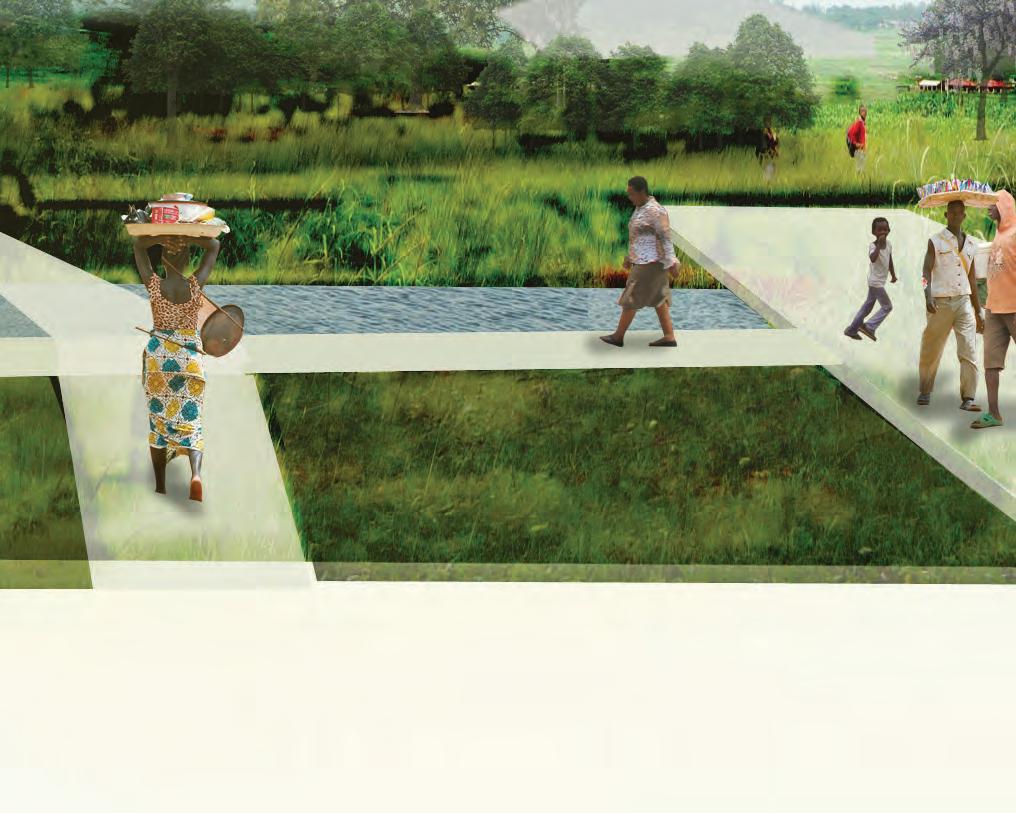

Through territorial and simple place-making moves, this project establishes a landscape framework for the growth of Hopley Farm, an informal settlement in Harare.

The provision of social hubs that residents usually do not build on their own, become the central infrastructure that complements the future self-built city and enhances the quality of the community.

A territorial growth pattern, rainwater management and an agroforestry system are linked to create a healthy community by tackling issues that plague Harare and its future growth.

A proppsal by Leonardo Robleto Constante

issue 1:

strategy: education cholera & dengue prevention wind

strategy: agroforestry mosquitoindigenousvegetationrepellentvegetation ( trees )

waterrainwaterstrategy:harvesting dambotableinfiltration protectionrain-fedagriculture

issue 2: issue 3:

sustainable hopley ( water )

SEERTEROM

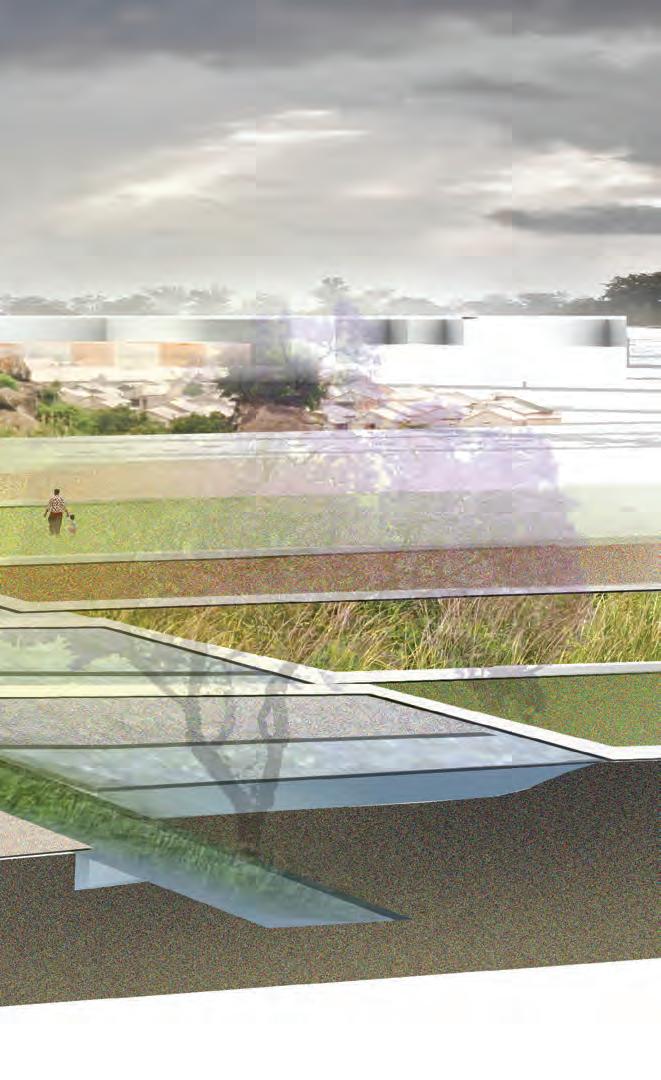

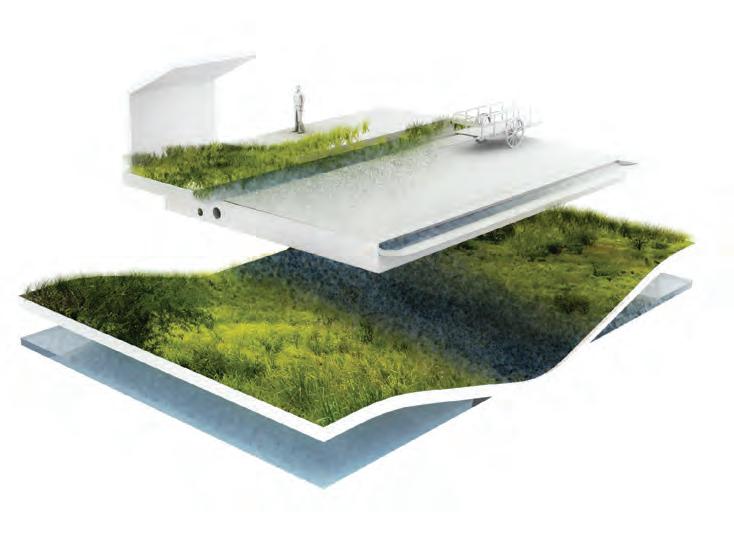

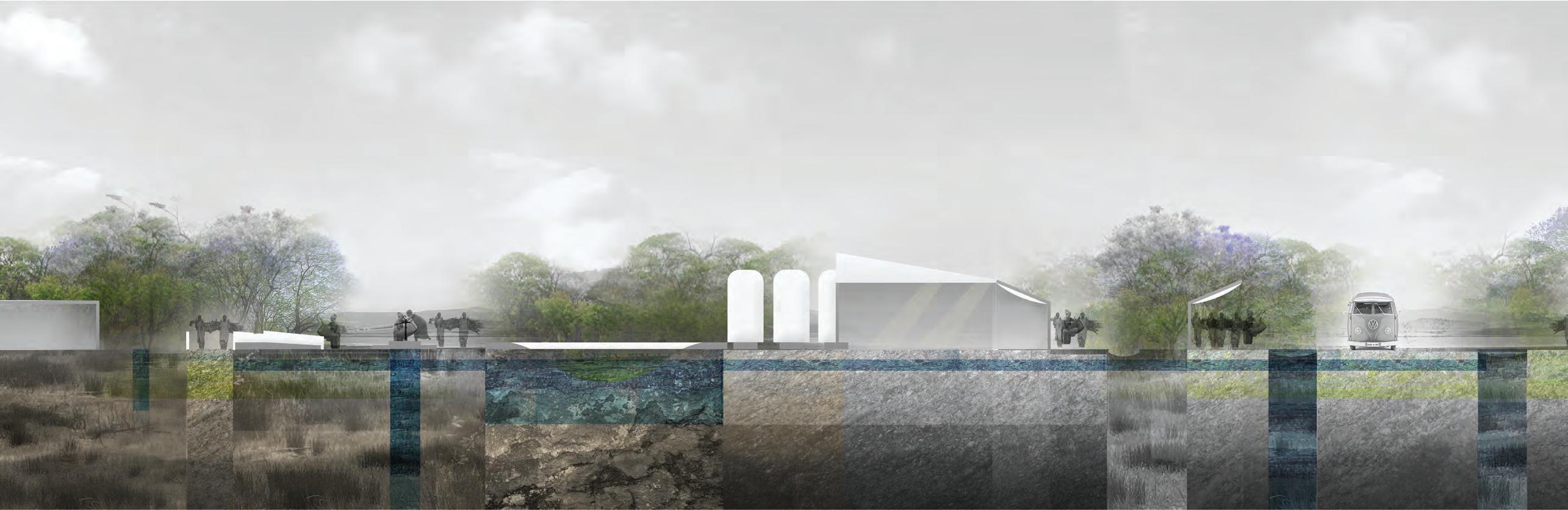

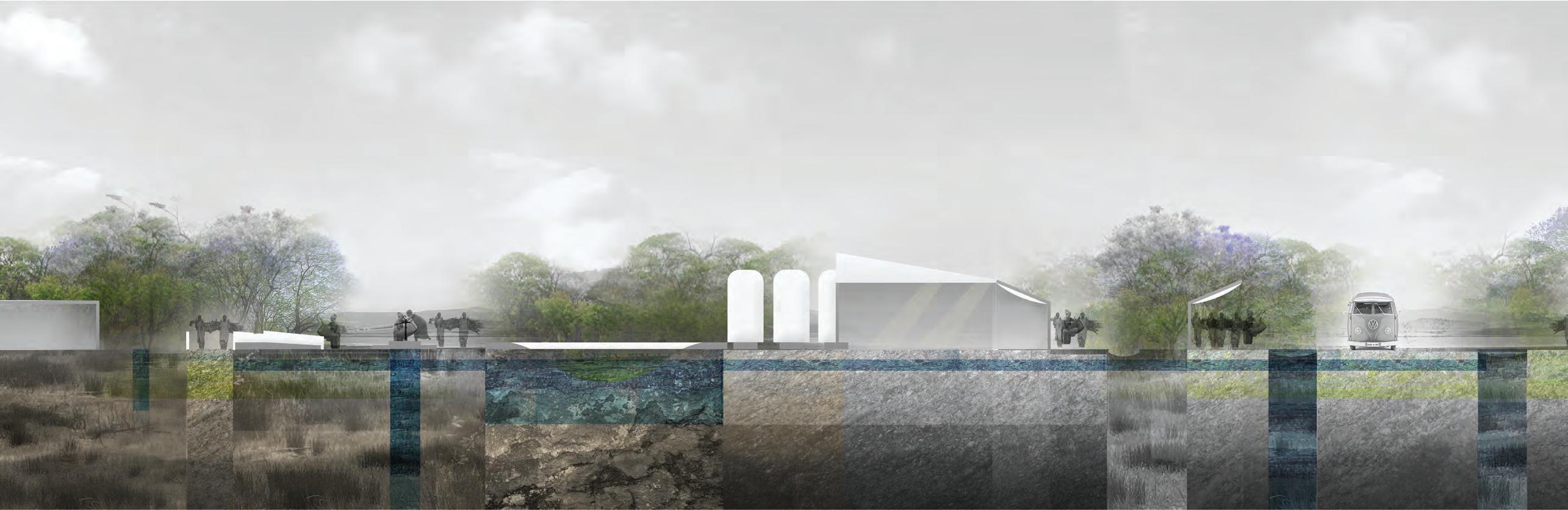

This project challenges the issues of designing for areas of informal settlements and their adjacency to wetland systems in Harare. In response to alternating constructs of wetland areas, the use and management of freshwater, wastewater and agriculture creates a series of public and communal spaces which respond to wet and dry seasons. Here, the acquisition and distillation of water resources alongside with wetland delineation become social and cultural gathering spaces.

These spaces are flexible because they enable adaptation to climate pressure while protecting critical resources as population increases. The design acts within the framework as an informal armature by guiding population growth while protecting water resources. By extending into adjacent areas as a method of water resource protection, the armature can adapt and create stronger connections by strengthening the ecological framework of the settlement.

A proppsal by Autumn Visconti

A proppsal by Autumn Visconti

Deschampsia cespitosa Tufted Hairgrass

Eleocharis palustris Creeping Spikerush

Juncus articulatus Jointed Rush

Mimulus guttatus Common Monkeyflower

PEDESTRIAN CROSSING

WATER INFILTRATION AQUEDUCT

CART/VEHICULAR CROSSING RAINWATER COLLECTION

CREEK DAMBO 2% SLOPE CONNECTS PRIMARY SCHOOL TO SETTLEMENTS

CLEAN WATER CHANNEL

MEDICINAL PLANTS

Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew nut

Allamanda cathartica L. Yellow allamanda

Zantedeschia aethiopica White arum

Sambucus canadensis Elderberry

Agave americana

Securidaca longipedunculata Fres.

ELEVATED PATHWAYS

PEDESTRIAN CROSSING

MEDICINAL PLANT VARIETY

VARIED SHADE CANOPY SENSORY UNDERSTORY

CREEK DAMBO 1% SLOPE CONNECTS CLINICS AND SETTLEMENTS

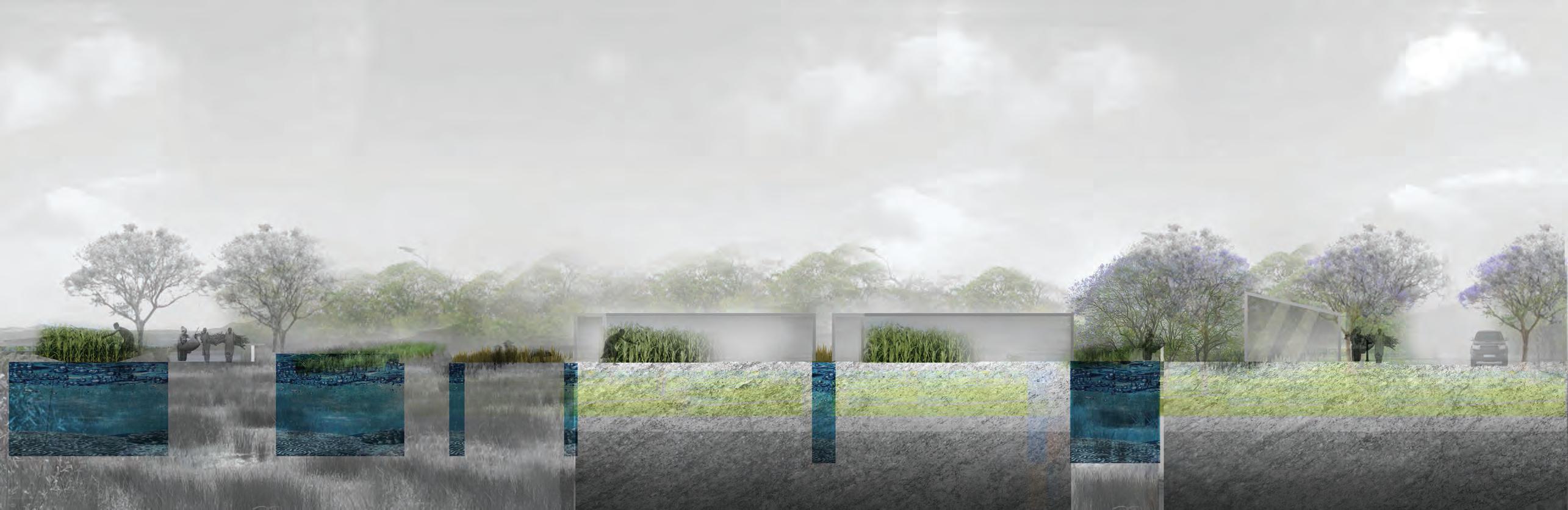

This project focuses on the community of Hatcliffe. It is the only informal settlement that is adjacent to one of the wealthiest communities in the city.

The objective is to create beneficial exchange of economic and cultural resources at this intersection of high and low income settlements. The strategy includes the reintegration of damaged, underutilized wetlands into a productive hydrological armature which addresses social interaction, water provision, and job creation.

A proppsal by Allison Dawson

A proppsal by Allison Dawson

HATCLIFFE

NURSERY (FLOWERS)

HARARE DRIVE

BORROWDALE

(

health

social interaction:

market space

social service “clusters”

water provision: green spaces

rainwater management

wetland protection

KEY TAKE-AWAYS:

1. PRE-EMPTIVE GROWTH STRATEGIES

2. FOCUS ON HEALTHY ENVIRONMENTS

3. PROVISION OF ABSENT PROGRAMS

4. CREATE LINKAGES TO THE FORMAL CITY

5. PROTECTION OF NATURAL SYSTEMS

6. ALTERNATIVE WATER HARVESTING SOURCES

7. EFFICIENT AND MULTI-SCALE AGRICULTURE

The work of our Planning and Urban Design group within Gensler as a global architecture, design and planning firm, takes us to many varied locations in the globe. We are constantly addressing challenges and opportunities posed by projects located in different climatic, geographic and cultural conditions. We work in the freezing tundra (Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation), in the humid and hot tropics (Malaysia, Singapore, Latin America), in arid desert locations (Middle East and North Africa), etc. As we learn from each unique location and project, we have come to believe that in this urban age, where the population living in urban areas far exceeds that of rural ones, cities are the scenarios where answers to humanity’s future ought to be found. As Jaime Lerner, former mayor of Curitiba in Brazil, rightly points out, cities should not be seen a problem but as the solution to contemporary life.

Ever since the presence of paths and rivers led to people meeting each other and exchanging goods and ideas, the physical conglomeration resulting from those exchanges created places where human beings tried to find satisfaction of basic needs and access to goods and services. Cities became the places where ambitions, aspirations and other material and immaterial aspects of life could be realized. Nevertheless, the prospects of prosperity and individual and collective well-being are constantly compromised by multiple causes and the prosperity generated by cities has not been equitably shared, leaving a sizeable proportion of the urban population without access to the benefits that cities can produce.

In our work we have found the need to think of cities as platforms that can generate and equitably distribute the benefits and opportunities associated with prosperity, ensuring economic well being, social cohesion, environmental and life quality, and we have become firm believers in the need to think of the future of our cities using a holistic, multi-disciplinary approach. The future of our cities is not the sole

WITH OVER 80 PERCENT OF ITS POPULATION LIVING IN CITIES, OUR URBAN AREAS ARE FACING THE CHALLENGES OF RAPID URBANIZATION, POLLUTION AND CLIMATE CHANGE. WHAT CAN WE DO IN OUR CITIES TO ADAPT TO CLIMATE CHANGE, IMPROVE LIVABILITY AND BECOME MORE SOCIALLY INTEGRATED?

domain of the politician, or the engineer, or the architect, or the landscape architect, or the planner, or the sociologist, or the economist, or the investor; all should be active part in the planning and construction of this future. We, as well as many other actors dealing with cities in this urban age, refer to this framework as “Sustainable Urbanism”, where we plan for people-centered places, capable of integrating the tangible and intangible aspects of prosperity, and shedding the inefficient, unsustainable forms and functionalities of the city of the previous century.

The lessons extracted from the work we do around the globe, lead us to believe that sustainable urbanism is a topic of global interest that should be based on an understanding of local circumstances, otherwise it runs the risk of being irrelevant. Sustainable developments must respond to and improve cultural, social, geographic, climatic, and environmental aspects, without overlooking economic sustainability and governance. Underlining the need to understand the specificities of every location, we have found common principles that contribute to the creation of a sustainable urbanism:

1. Promoting compact and denser developments, reducing our cities’ urban footprint and inducing walking and bicycling.

2. Inducing behavior change, educating the population and increasing general awareness about our cities and environments of which they are part of.

3. Mixing compatible uses, where housing, work, education and recreational functions may be located within reachable distances.

4. Increasing connectivity by considering intermodal public transit, linked to density and land uses.

5. Proposing uses and operations that are socially and economically viable.

6. Controlling air, water, noise and visual contamination.

7. Reducing, reusing and recycling solid waste, which may require a reorganization of public services, and educating the population in regards to its benefits.

8. Fostering sustainable life cycles, where opportunities for increased autonomy in the production of food, energy and water are considered.

9. Stimulating knowledge, innovation, job creation and social interaction.

10. Preventing natural disasters, including the capacity to mitigate risks. This involves showing respect for the territory and reconnecting to the history and culture of the place where the city seat is.

11. Considering sustainable infrastructure and architectural strategies.

12. Looking towards a better future, while learning from the mistakes and successes from the past and present.

13. Developing programs of immediate and short-term application tied to a mid- and long-term vision. They should respond to pressing needs that cannot wait for a later response.

Visiting Harare for the first time meant setting foot in a place that reminded me of my native Colombia. This, and the chance to connect with the new generation that is being educated at my alma mater of past years, sparked a lot of “dot connecting” moments. The Gensler / Penn Harare studio has been a window to reframe the knowledge and experience acquired in the planning work we do at Gensler, and to filter it through the realities of developing nations, toned with opportunities, challenges and permanent contradictions, while building visions of a brighter future for current and future generations. I strongly relate to this.

The intellectual and creative capital of Penn students and professors, stimulated by the thoughts of invited critics, Zimbabwean colleagues, officials and citizens that have been active part of the Gensler / Penn Harare studio, is compiled in this publication. It sets compelling, fresh and ingenious planning seeds that seek to achieve a more inclusive and prosperous future for the capital of Zimbabwe. Some may reflect ideas that could be implemented in the short term while some may require longer planning horizons. All should be enriched and fine-tuned with the added input and participation of

local authorities, stakeholders and communities.

Planning by definition deals with the future, and to put ideas into reality considerable time is sometimes needed, running contrary to the pressing needs of the population and the short term political life span of local administrations, desperate to find innovative and relevant ideas that could see the light of day in as short a timeline as possible. As an interesting precedent already shared in that memorable first week in Harare at the start of 2013, I would like to mention the potential relevance of some of the events that I witnessed and was a part of when I was living in Bogota, Colombia, before joining Gensler. It was providential that an unprecedented trio of well prepared and innovative mayors occupied office consecutively, each building upon the strengths and legacy of his predecessor. Jaime Castro put city finances back in health; Antanas Mockus engaged in educational and cultural campaigns, fostering pacific behaviors and increasing civic awareness and tolerance; Enrique Peñalosa focused on transportation, open space and education as a backbone to increase equality and inclusion. Peñalosa understood the need to have a city wide vision for years to come,

“I BELIEVE THAT IF PEOPLE KNOW THE RULES AND ARE SENSITIZED BY ART, HUMOR, AND CREATIVITY, THEY ARE MORE LIKELY TO ACCEPT CHANGE. THE CRUCIAL POINT OF A CITIZENS’ CULTURE IS LEARNING TO CORRECT OTHERS WITHOUT MISTREATING THEM OR GENERATING AGGRESSION. WE NEED TO CREATE A SOCIETY IN WHICH CIVILITY RULES OVER CYNICISM AND APATHY”

- Antanas Mockus

but also engaged in a set of key strategic actions to be implemented during his three years in office, promoting a city model giving priority to children and public spaces and restricting private car use, building hundreds of kilometers of sidewalks (where cars were not allowed to park), bicycle paths, pedestrian streets, greenways, and parks. He led efforts to improve Bogotá’s marginal neighborhoods through citizen involvement; understanding the added value of good design he engaged local architects to design parks, libraries -in buildings and on wheels-, and schools to be run by the private sector; planted more than 100,000 trees; created Transmilenio, a highly successful bus rapid transit system; and turned a deteriorated downtown avenue into a dynamic pedestrian public space. He helped transform the city’s attitude from one of negative hopelessness to one of pride and hope, believing in the need for high quality and welldesigned physical environments to develop a model for urban improvement based on the equal rights of all people to transportation, education, and public spaces.

The Penn students’ proposals for Harare think of the city as a place for individual expression but also for collective action, while focusing only in one part of the

city, due to practical and time constraints. Hopefully, subsequent studios will focus on other parts of the urban area and the region in general, and start to consolidate an overall framework tying planning and design ideas together. The outcome of the Gensler / Penn studio shows some of the inventiveness and simplicity of ideas set forth in Bogota and in other cities in emerging economies, which like Harare, are in a constant quest for a more balanced, sustainable and inclusive future for its citizens, including innovative yet simple ideas. These Penn proposals address perceived opportunities to enhance the public realm, create physical environments that provide citizens much needed access to high quality amenities and services, and consolidate rights to the ‘commons’ for all as a way to expand prosperity and inclusion under an umbrella of sustainable urbanism. They represent an opportunity for Harare to openly ask questions about what it wants to be, make decisions, and implement actions that could become urban seeds to spark prosperity. These projects are an opportunity to build a shared and enduring vision for Harare that could serve as a guide for the current and future administrations and the population they serve.

“BEYOND SURVIVAL NEEDS, WE HAVE “HAPPINESS NEEDS,” OR “WELL-BEING NEEDS,” THAT A GOOD CITY WOULD HELP FULFILL: WE NEED TO WALK; TO SEE AND BE WITH PEOPLE; TO FEEL INCLUDED AND NOT INFERIOR; TO HAVE CONTACT WITH NATURE (SUCH AS TREES OR WATER), BEAUTY, ART, AND QUALITY ARCHITECTURE”.

- Enrique Peñalosa

Special thanks to the project sponsor Old Mutual and to the Citizens of Harare.