FACTS AND PERSPECTIVES ON THE PLAY, PLAYWRIGHT, AND PRODUCTION DIGITAL PROGRAM AND 360 ° VIEWFINDER SERIES

WWW.TFANA.ORG

THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE

Polonsky Shakespeare Center

Jeffrey Horowitz FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Robert E. Buckholz BOARD CHAIR

in association with

ROSE THEATRE

Present

Dorothy Ryan MANAGING DIRECTOR

THE ROYAL LYCEUM EDINBURGH PRODUCTION

MACBETH (AN UNDOING)

written and directed by ZINNIE HARRIS, after William Shakespeare

On the Samuel H. Scripps Mainstage

Featuring

ADAM BEST, EMMANUELLA COLE, NICOLE COOPER, LIZ KETTLE, THIERRY MABONGA, MARC MACKINNON, TAQI NAZEER, STAR PENDERS, JAMES ROBINSON, LAURIE SCOTT

Scenic Designer

TOM PIPER

Movement Director

EJ BOYLE

Costume Designer

ALEX BERRY

Lighting Designer

LIZZIE POWELL

Resident Voice Director ANDREW WADE

Production Manager

NIALL BLACK

Press Representative

Sound Designer PIPPA MURPHY

Production Dramaturg FRANCES POET

Casting

Composer

OĞUZ KAPLANGI

Fight/Intimacy Director

KAITLIN HOWARD

SIMONE PEREIRA HIND CDG AND ANNA DAWSON

BLAKE ZIDELL & ASSOCIATES

Producer

HANNAH ROBERTS

First preview April 5, 2024

Opening night April 11, 2024

General Manager

JEREMY BLUNT

Support for Macbeth (an undoing) is provided by Shakespeare in American Communities, a program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest.

2023-2024 Season Sponsors.

Principal support for Theatre for a New Audience’s season and programs is provided by the Bay and Paul Foundations, the Howard Gilman Foundation, the Jerome L. Greene Foundation Fund in the New York Community Trust, The SHS Foundation, The Shubert Foundation, and The Thompson Family Foundation.

Major season support is provided by The Arnow Family Fund, The Cornelia T. Bailey Foundation, Sally Brody, Robert E. Buckholz and Lizanne Fontaine, Constance Christensen, The Hearst Corporation, Stephanie and Tim Ingrassia, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP, Latham & Watkins LLP, The George Link Jr. Foundation, Audrey Heffernan Meyer and Danny Meyer, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation, Stockel Family Foundation, Anne and William Tatlock, Kimbrough Towles and George Loening, Kathleen Walsh and Gene Bernstein, and The White Cedar Fund.

Theatre for a New Audience’s season and programs are also made possible, in part, with public funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities; the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature; and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

Open captioning is provided, in part, by a grant from NYSCA/TDF TAP Plus.

2 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

CAST

(in alphabetical order)

Adam Best....................................................................................................................................................................Macbeth

Emmanuella Cole........................................................................................................................................ Lady Macduff/Mae

Nicole Cooper.....................................................................................................................................................Lady Macbeth

Liz Kettle.........................................................................................................................................................................Carlin

Thierry Mabonga............................................................................................................................................. Macduff/Doctor

Marc Mackinnon....................................................................................................................................... Duncan/Murderer 2

Taqi Nazeer........................................................................................................................................... Bloody Soldier/Lennox

Star Penders...................................................................................................................................................... Missy/Malcolm

James Robinson............................................................................................................................................................ Banquo

Laurie Scott.................................................................................................................................................... Ross/Murderer 1

Company Stage Manager............................................................................................................................... Claire Williamson

Stage Manager............................................................................................................................................... Shane Schnetzler*

Deputy Stage Manager........................................................................................................................................... Jessica Ward

Assistant Stage Manager........................................................................................................................................... Katy Steele

*Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States.

THERE WILL BE ONE 15-MINUTE INTERMISSION

Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh gratefully acknowledges

Reid Hoffman

Kathy and Ned Hoyt

Michael and Tammy Thorson

Nancy Hale Hoyt

Inventure Capital LLC

Stephen W Dunn Theatre Fund

Sir Ian Rankin, OBE DL FRSE FRSL FRIAS

David and Judith Halkerston

Margaret Duffy and Peter Williamson

For their generous support of this production’s tour.

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 3

1930s.

TIME

SETTING Scotland.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

5

Support for Macbeth (an undoing) is provided by Shakespeare in American Communities, a program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest.

Notes

Front Cover: Design by Paul Davis Studio / Mo Hinojosa

This Viewfinder will be periodically updated with additional information. Last updated April 18, 2024.

Credits

Macbeth (an undoing) 360° | Edited by Nadiya L. Atkinson

Resident Dramaturg: Jonathan Kalb | Council of Scholars Chair: Tanya Pollard | Designed by: Milton Glaser, Inc.

Publisher: Theatre for a New Audience, Jeffrey Horowitz, Founding Artistic Director

Macbeth (an undoing) 360° Copyright 2024 by Theatre for a New Audience. All rights reserve d.

With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Viewfinder may be reproduced in any

4 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

form

mechanical, including photocopying or recording,

information

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Some materials herein are written especially for our guide. Others are reprinted with permission of their authors or publishers.

or by any means, electr onic or

or by any

or

Antagonists

Ayanna

Harris

Dialogues: Renaissance Women: A new book celebrates—and sells short—Shakespeare’s sisters by Catherine Nicholson 26 Bios: Cast and Creative Team About Theatre For a New Audience 17 Leadership 18 Mission and Programs 19 Major Supporters

Dialogues: Female Fury in Macbeth (an undoing) by Tanya Pollard 8 Interview: Adaptation and Translation: The Reinvention of Female

moderated by

Thompson with Zinne

16

DIALOGUES FEMALE FURY IN MACBETH (AN UNDOING)

BY TANYA POLLARD

Shakespeare’s Macbeth, like his Hamlet, Othello, and Lear, centers on the portrait of a complicated and dangerous man. Yet although the play introduces him as “brave Macbeth,” a powerful warrior famed for his ability to kill, its first two acts depict him as oddly passive, a hesitant puppet steered by forceful female figures. Just as his first words echo those of the witches who precede him onstage, his defining action – the murder of King Duncan – responds to the urging of his wife, whose fiery incitement invokes the supernatural figures who open the play. “Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts,” she exhorts, “unsex me here, / And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full / Of direst cruelty!” Conspiring with the Weird Sisters, Lady Macbeth initiates the play’s violence through an uncanny transmutation. Like the similarly superhuman Cleopatra, who insists in her final moments, “I have nothing / Of woman in me,” she leaves her sex behind as she enters a new world of unsettling possibility.

As Zinnie Harris has observed, what follows is a surprising reversal. While Macbeth’s uncertainty hardens into a steely core of violence, Lady Macbeth’s fire flickers into a dim shadow of its initial fury. Her speech

diminishes from terrifying eloquence to broken fragments as she succumbs to madness, nightmares, and increasing passivity. What might the play look like, Harris invites us to wonder, if its initial glimpse of female fury were allowed to linger, and even to grow?

Shakespeare rarely allowed female roles to take over the heart of his tragedies. With female characters relegated to apprentice boy actors, his most starry tragic leads went to the male protagonists who showcased his best-known company members. Cleopatra, the most prolix of his tragic women, speaks far less than her male counterpart, 693 lines to Mark Antony’s 839; the eloquent Juliet also lags behind her Romeo, speaking 572 lines to his 615. For all her verbal incandescence, Lady Macbeth fares even worse. Alongside Macbeth’s 725 lines, she speaks only 263, most of them in the play’s first two acts.

But twenty-first century stages, unencumbered by the limitations of early modern London’s gendered casting practices, have the freedom to reimagine this division of theatrical labor. In Macbeth: An Undoing, Lady Macbeth’s lightning-like flare not only continues but escalates. As her

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 5

Emmanuella Cole (Lady Macduff), Nicole Cooper (Lady Macbeth) in MACBETH (AN UNDOING) at Theatre for a New Audience. Photo by Hollis King.

FEMALE FURY IN MACBETH (AN UNDOING)

husband becomes increasingly paralyzed, the two of them gradually exchange roles. He dissolves into the sleepwalking nightmares that his wife experiences in Shakespeare’s version, while she steps into his shoes, becoming Scotland’s real monarch.

Not only does Lady Macbeth maintain her fury in this play, but she gains an ambivalent quasi-sisterhood. Lady Macduff, to whom Shakespeare allocates only one scene and 45 lines, enters this play early on and becomes one of its most major characfters, adding new dimensions to Lady Macbeth’s crisis. Consistently addressed as “sister” by Lady Macbeth–though the two are eventually revealed to be cousins, like As You Like It’s similarly intimate Rosalind and Celia – she serves as confidante, foil, and competitor.

Lady Macduff’s most conspicuous contribution to this play is her pregnancy and its aftermath, new elements that underscore the original play’s preoccupation with fertility and succession. “I have given suck,” Lady Macbeth famously proclaims in one of Shakespeare’s most disturbing passages,

and know

TANYA POLLARD

How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me: I would, while it was smiling in my face, Have pluck’d my nipple from his boneless gums, And dash’d the brains out, had I so sworn as you Have done to this.

As an aristocrat, Lady Macbeth would not have served as a wet-nurse; having given suck means having given birth. Yet the Macbeths have no living offspring. On hearing of his family’s terrible demise at Macbeth’s orders, Macduff observes, “He has no children.”

Scholars and theater-practitioners alike have long reflected on the implications of Lady Macbeth’s passing reference to maternal experience. In a 1933 lecture titled, “How many children had Lady Macbeth?,” the critic L. C. Knights mocked what he saw as a trivial fixation on this hypothetical question. Yet Shakespeare makes clear that the problem of offspring looms large for the Macbeths, both personally and politically.

6 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

Adam Best (Macbeth), Nicole Cooper (Lady Macbeth). Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

FEMALE FURY IN MACBETH (AN UNDOING )

TANYA POLLARD

Lady Macbeth’s unsettling image of infanticide might be the most startling sign that the couple has descendants on their minds, but it’s far from the only one. “Bring forth men-children only,” Macbeth exhorts his wife when praising her forceful directives on murdering Duncan, adding, “For thy undaunted mettle should compose / Nothing but males.” Later, reflecting on the threat posed by Banquo, he recalls with concern the witches’ early prediction to Banquo: “Thou shalt get kings, though thou be none.” This prophesy, which prompted little discussion at the time, comes back to Macbeth in full force after he has achieved his own promised status. “They hail’d him father to a line of kings,” he recalls:

Upon my head they placed a fruitless crown, And put a barren sceptre in my gripe, Thence to be wrench’d with an unlineal hand, No son of mine succeeding.

Macbeth realizes, too late, that winning the kingship means nothing without heirs to extend his reign into the future; in their absence, his line will be extinguished with his death. “If ’t be so,” he realizes, “For Banquo’s issue have I filed my mind; / For them the gracious Duncan have I murder’d/... Only for them.” His terrible act proves literally fruitless; it will lead nowhere.

Shakespeare’s portrait of Lady Macbeth omits direct access to any feelings she might have about her childless state, but Macbeth (an undoing) moves this lack to the fore of the play, entangling Lady Macbeth with not only Lady Macduff but also the Weird Sisters in a web of grief, longing, and desperation. As a looking-glass version of Macbeth, this female-focused story shifts its lens inwards from forests and battlefields to the more private spaces of marriage, friendship, and female bodies, and in doing so offers a new story about Shakespeare’s supernaturally charged violence..

TANYA POLLARD (Chair, Council of Scholars) is Professor of English at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Her books include Greek Tragic Women on Shakespearean Stages (2017), Drugs and Theater in Early Modern England (2005), Shakespeare’s Theater: A Sourcebook (2003), and four co-edited collections of essays on early modern drama, emotions, bodies, and responses to Greek plays. She appeared in Shakespeare Uncovered: Macbeth (PBS, 2013) with Ethan Hawke and in Shakespeare Uncovered: King Lear (PBS, 2015) with Christopher Plummer. Beyond her involvement with TFANA, she has worked with artists and audiences at theaters including the Red Bull, the Public, the Classic Stage Company, and the Roundabout. A former Rhodes Scholar, she has received fellowships from the Guggenheim, NEH, Whiting, and Mellon foundations.

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 7

Liz Kettle (Carlin). Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

INTERVIEW “ADAPTATION AND TRANSLATION: THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS”

MODERATED BY AYANNA THOMPSON IN CONVERSATION WITH ZINNIE HARRIS

The following is an edited version of a conversation between Zinnie Harris (Writer and Director) and Ayanna Thompson (TFANA Council of Scholars) that took place on March 28, 2024.

AYANNA THOMPSON So, Zinnie, I'm wondering if you can tell us how you first encountered Shakespeare, and then how your relationship has developed.

ZiNNIE HARRIS So, I think, like a lot of young people I first encountered Shakespeare at school. I did Macbeth for my GCSE. I'm trying to think if I'd seen Shakespeare before then.

My mum was really good at taking me to the theatre, and I remember going to see King Lear at 12, 13, maybe, and being blown away by it. I remember coming out in the interval, kind of thinking, what on earth can happen next? So, I think I was lucky about the number of Shakespeare I encountered first in performance rather than on the page.

I don't know if you know my background. But I didn't go on with English literature. I went on to science and did biology at university. I never really formally studied

Shakespeare, so my experience of it is really as a kind of either theatergoer or theatermaker and dramatist.

AYANNA THOMPSON It's interesting that you say that you think your first experience was probably in the theater because that was the same for me. And I have often joked that if I were Jeff Bezos, I wouldn't try to send myself into space. I'd be making sure that every eight-year-old got to see a live performance.

ZiNNIE HARRIS That's right. And I think sadly, in the UK, drama is being squeezed out as a classroom activity. And the only way that you're likely to encounter Shakespeare is through an English class, where it becomes about the words on the page and the rhythm. And what you don't experience is this is actually about two people in a relationship with each other and the space between them and what they want. Shakespeare is, like any drama, a three-dimensional living, breathing art form that you have to see on its feet.

AYANNA THOMPSON Yeah. And also, as you described with King Lear, you can enter into the interval and not know where it's going.

8 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

Nicole Cooper (Lady Macbeth), Emmanuella Cole (Mae), Star Penders (Missy), Liz Kettle (Carlin). Photo by Hollis King.

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS” AYANNA THOMPSON

ZiNNIE HARRIS Yeah, it's a story that happens to you.

AYANNA THOMPSON What made you transition into wanting to rewrite it in some way or to revisit it? And was this something that you had thought of over a long span of time? What was your inspiration?

ZiNNIE HARRIS Well, I didn't just hop straight to Macbeth. I, as a dramatist, have been for a long time interested in taking canonical dramatic texts and working particularly with the female roles. You know, taking one of the main female characters and doing a revision to ask questions of treating this character as a modern character, approaching them with a more sympathetic understanding, and seeing the story from their perspective. What would that journey look like?

So, I first worked on a play in this way–although now I look at the adaptation and I think it was very faithful–with Miss Julie in 2009. My approach is to have two things in play when doing an adaptation. One, you should really love the original and feel an affinity for it, so there's enthusiasm for the story. But the second thing is you have to feel that there's something that you can bring and that it's going to engage your skills as a dramatist. And you're triangulating between the original text, you, and the world. Right now, you know that there's a reason it should be done and you approach it that way.

And with Miss Julie, it's this story of privilege and there's a character that we are encouraged to loathe throughout the piece. We see her as an overprivileged sort of brat and when we witness her destruction at the end, in the productions I'd seen, I'd always gone off thinking, “Thank God, I never really liked you anyways.” I just kind of thought, hang on. This is a young woman here. Yes, she's privileged, but if you really look into the text, she's pretty controlled by her father. She hasn't got many options, and she hasn't been given a language or a way of being in the world that would mean that she can operate in any other way.

So I went into that with a “what if?” What if she's not actually the bad guy here? And I found that quite interesting. And it started a kind of confidence to approach those texts. I think the next one was I did a version of A Doll's House. In a way, I was talking about marriages in public life. I made them a political couple who just moved

into a sort of Downing Street, and the sense that scrutiny they were under, and what that did to the pressure between them and the ability to be kind to each other. And the big one that I really am very proud of is This Restless House of The Oresteia. I felt that Clytemnestra, a bit like Lady Macbeth, is this kind of received evil woman. He's the hero, and what does she do? She kills him in the bath.

But let's think about this differently. He has gone off. He's been away for ten years for a war that she never thought was a good idea, with the implication that he was doing it for vanity. Before he goes, he sacrifices their much-loved daughter. He abandons her for ten years to fight a war. She's left to run the country. Who knows how that's gone for her? And he expects to walk straight back into not just shared power with her, but her bed, and has an enslaved girl in tow that he's had on the side. And you go, with a more sympathetic view, there could be a totally different way of looking at this.

And maybe she isn't someone who is born knowing that she is capable of murder, but someone who is compelled to murder out of love for her child, and that sense of justice. And The Oresteia is all about justice and vengeance. So then the first play became about her internal resistance and the fact that the ghost of her child haunts her. We see her turn into someone who is against all odds, capable of killing him, and gives him many opportunities to show himself, to be remorseful, and he doesn't take them.

And then, of course, when you've done the first play, it's a trilogy, and I wanted to keep working with the female line. The whole trilogy is called The Oresteia after Orestes. But Orestes isn't even present in the first play, whereas Electra clearly lives in the castle or house. And so I chose to work with Electra rather than Orestes.

After that, I worked on a version of The Dutchess of Malfi: in a way, The Dutchess of Malfi is a proto-feminist play. I think his [John Webster’s] purpose in writing that piece is to say, at our peril, we destroy women. Look what happens when we do this: we see the destruction of the perpetrators, the male characters, and the family, by the end. But I felt that it was saying to the audience, “Look, not only has there always been violence against women, but this confusion of love and control has always been a

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 9

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS”

problem as well.” And here was Webster writing about it in the seventeenth century. That was part of my intent.

But I thought there was also something else. And, in a way, this relates to Macbeth about how we see female victims. One of the things that happens in Duchess is once the Duchess dies, she's gone. And then we are left with this male play of how it all unravels for them. I wanted to keep her agency even after death and suggest that she retains her power and is able to send a message out to the audience at the end to say things need to change.

Part of the mechanism with which I was able to do this, is that Ferdinand is her twin and the person who ultimately destroys her. And he starts to go mad. He believes he's a wolf, but he talks about being chased by this shadow. I was thinking, “What is Webster getting at here?” When you've killed your twin, then surely the shadow is their ghost. So, I suggested that the victims continue to have agency as ghosts after their deaths. Which, clearly, it's not much good to have agency if you're dead, but I say that's not the end of the story. Actually, things can happen beyond as a result of your story and change can happen.

And you know that is one of the things that I have tried to do particularly with Lady Macduff in Macbeth (an undoing). In the original, we meet Lady Macduff at the moment of her destruction. She's there just as a victim. And it's the same image that we've seen in TV dramas for years, of the dead woman that we don't know anything about. We only see her as a victim. And we get in Shakespeare this image of a maternal kind of femininity being destroyed. And I just think, for a contemporary audience, we want a bit more in the dialogue about the portrayal of women and violence against women. If life is going to be taken away, we want to be invested in it. We want to see the character as a whole person.

AYANNA THOMPSON And it's interesting that you mentioned that, because I've worked on a bunch of productions of Macbeth and the audience is always confused by Lady Macduff, because she just pops up. And then, you have to work really hard to make sense of that scene if you have an audience that hasn't read the play.

ZiNNIE HARRIS Yeah, and lots of directors do it in different ways. So, you often have her sort of appear in an earlier moment. But she's not there.

AYANNA THOMPSON

AYANNA THOMPSON She’s underwritten.

ZiNNIE HARRIS She's underwritten. She's massively underwritten, yeah.

AYANNA THOMPSON Clearly, Macbeth (an undoing) is part of this amazing feminist adaptation trajectory that you've been on—working through these foundational texts that, as we've just agreed on, have underwritten women. So what attracted you to Macbeth?

ZiNNIE HARRIS Well, having sort of worked on Clytemnestra, I thought, who's next? And then there's Lady Macbeth and she's not only fascinating because of the scenes that we have with her, but also because of the place that she takes in our collective consciousness. She must be one of, if not the most, well-known female characters in the Western canon of dramatic works. I know that she has a dictionary entry of her own. How many other fictional characters get that?

And yet there is this total contradiction in the middle of her story that doesn't make sense, so why is it that she has become iconic? We all know that there is this flaw. She's almost an assemblage of two different moments: we get two different versions of femininity that sit alongside each other but with no explanation of how we get from one to another. So, we get the dastardly, ambitious cold-hearted woman, who cajoles her husband into murder and then we get the broken, mad woman who can't cope with her own guilt. And could it be that the reason she's become so iconic is that we're fascinated by the first version, and we're comforted that if you are that sort of person, your downfall is part of your story?

So what the hell happened between the two? I teach playwriting to students at the University of St. Andrews, and we talk all the time about writing in the gaps when you're playwrighting. You set a scene, but maybe your play is over the scale of six months or two weeks. You can't get your audience to sit there for two weeks, right? So, a lot of the story telling is in gaps between your scenes.

One of the skills is to set a trajectory of a character within a scene, and then leave them not only in a position, but with a sort of forward arrow to where they're headed, and then you can pick them up a day later, or two weeks later, and the audience will fill in

10 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

what's happened to them. And Shakespeare knows this better than anybody. We see it all the time. Trajectories.

What's curious about Lady Macbeth is between the first half and the second half, the trajectory is all wrong. Lady Macbeth from the beginning is going, “Come on, we can do this.” He's faffing around, saying, “Is this dagger I see before me?” Can I get my head around it? And she's going, “Come on, be a man!” He then does it, but slightly mucks it up by bringing the daggers in, and she goes, “Good grief. That was the one thing you weren't supposed to do.” She's managing him, as she tells us right at the beginning, “I know his nature, he's too full of the milk of human kindness.”

So she sorts out the daggers. Then they've got a problem with Banquo. He arranges for Banquo to be murdered, and then he starts to be haunted by the ghost! And she's pulling him aside, saying, “For God's sake, get a grip. We're going to look guilty.” That's the trajectory. She's on the up in terms of her power, and he's starting to deteriorate. Not only that, but as soon as he kills Duncan, he becomes preoccupied by sleep. He says, “Methought I heard a voice cry, “Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep.’” And if you look in detail at the sleep quotes, Macbeth is always obsessed with sleep. So he's going down into madness. She's going up, and then when we we meet them in the second half of the play, they've crossed again. He’s up and she’s down with none of the dots joined up inbetween.

AYANNA THOMPSON The chiasmus, right.

ZiNNIE HARRIS Yeah. And you know, and one of the things I did when I first pitched this to David Greig, who runs the Lyceum, my initial thought was not to change the text, but just to have whoever played Lady Macbeth take Macbeth’s track after this kind of hinge point. But when I got into it, because of reasons to do with Lady Macduff and the witches, I felt that if I was doing a feminist revision and I wanted to do more than that.

When I was doing my early research, I spoke to some academics. There is a school of thought that there's missing material from Macbeth. It's a much shorter play than the other tragedies. There are also references in it to things that haven't happened as if the audience has seen it, like Lady Macbeth saying to Macbeth, “Had I so

sworn,” when we haven't seen the scene where he swore to kill Duncan. So that gave me a license to imagine that Shakespeare didn't plan to have this odd thing with trajectories, which he as a dramatist clearly wouldn't leave us with. What if there was missing material and what might that look like? That was quite a good invite to myself as a dramatist to go, “I'm going to get her to a point of madness at some point. But she doesn't have to go straight there.”

AYANNA THOMPSON I'm glad that you raised teaching playwriting at St. Andrews, because I wondered, what is your approach with your students and how many classical plays do you make them read? What's your approach there in terms of getting them to think about these trajectories?

ZiNNIE HARRIS First of all, I teach playwriting as a craft. I think you have to get quite into the technique in some ways. And what I say is we don't have to reinvent the wheel. There are really good playwrights out there that can show us how these skills are done. And I can give you a specific example from Macbeth. Every class will start with a text, sometimes a very contemporary play. Sometimes it might be a scene from Shakespeare. Let's look at how the writer uses visual storytelling. What's the dialogue doing? How are they describing the interrelational space?

Sometimes I'm asked by students, “how do you work with time across a play?” One of the things I think we have to do as playwrights is know how to compress time and give the illusion that a whole day has past, but only ten minutes might be in sort of stage time. And I think the Porter scene in Macbeth is a wonderful example of the concertina of time. So what does he do? Well, you look at it on the page, and there's this knock, knock, knock! He gives us a rhythm almost like a metronome knock, knock, knock! He sets up this meter. I love the Porter scene for so many things, particularly the idea of portals and hell, and coming in and out just at that moment when we know that the ultimate transgression has happened, and Duncan has been killed.

So you get a chunk of time with the Porter on his own, and then he brings in Macduff who is coming for the king. So let's say, that's a page, and then he brings the next character in. But it's not a full page. It's like two-

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 11

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS” AYANNA THOMPSON

thirds of the page. And then he brings the next character in, but it's only half a page, and then he only brings the next character in, and it's a quarter page. And so, he's speeding up the entrances and the amount of time. Then everybody's in, they discover the murder, and then they all leave in the same way–after a quarter page, a half page, and a page. So what he's literally done is concertina with this metronome at the beginning.

The scene starts in the middle of the night, and by the end it's morning. It's only four or five minutes of playing time. But he's given us a kind of experience of time, which is totally different. So I suppose that’s what I do with my students. I go, “Okay, here's a little example. Yes, it's a play that's 400 years old, but everything about it still stands because your audience is still experiencing stage time different from real-time, and you've got to change the metronome.”

AYANNA THOMPSON Oh, I love that. And you know, as often as I've worked with Macbeth, I've never noticed that. You know, you feel that galloping feeling, but I've never thought of it in terms of how they leave or enter.

ZiNNIE HARRIS Yeah. I'm a director as well, but I primarily approach the text as a dramatist and all the time I'm going with my dramatist's head, “What's he doing here? What's he trying to do?” Obviously, we haven't talked about Lady Macbeth yet, and we will. But one of the things that I feel is that she's misunderstood a little bit.

AYANNA THOMPSON Totally.

ZiNNIE HARRIS Even in the beginning she's misunderstood, but the speech that is given as an example of her most evil is that “I have given suck” speech. This woman is grasping for an example of, “If I said I'd do something, I blooming well would do it.” But the example that she grasps for is, “If I said I would dash my baby's head out, I would blooming well do it.” Okay, pretty bad example. But in the context of that scene, they're talking about being a host. What she's saying is, “I've been the ultimate host. I've been so much a host that I've taken a baby to my breast, and I've fed it just like you're feeding Duncan. But we are providing for Duncan, and even in that host guest circumstance, I would go on to kill if I had said so.” The ways that we've misunderstood her are actually about not understanding the context of what she's saying and doing.

AYANNA THOMPSON I think the amazing thing about Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, in particular, is that there is a cultural narrative about them as symbols that actually bears very little relationship to the play. The idea that she's the engine of murder is so weird, because the first moment when Macbeth encounters the witches, he's like, “Oh, I'm already thinking about killing.”

ZiNNIE HARRIS That's right, with “my seated heart knock at my ribs.” Absolutely, absolutely. And I've got a line in my play when she says, “Did it not occur to you first?” And what she's sort of saying when she talks to us about her husband is, “I know he'll want to do it, but I know he won't. He won't have the guts. He has too much kindness within him, and I know what I need to do to get him there.” But he's well ahead, and he's talking about the fact that he's got a step over Malcolm to get there.

AYANNA THOMPSON He's already planning the murder before we've encountered Lady Macbeth. And that's what makes them a perfect couple, as you know, the oldest joke. The perfect match is that you hear the opportunity, and you both jump to the same way through.

So tell us about your Lady Macbeth, and how you worked to get her a new story. And you know, as you say, you have to end up in madness because you're keeping with the structure. But what did you feel like you could change?

ZiNNIE HARRIS I kept much of the structure at least initially. One of the things I'm trying to talk about is the narratives that we have about women. So Lady Macbeth, in my version, is pretty faithful to Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth in the first half. I have put in contemporary material because I wanted to give her a relationship with Lady Macduff. But she's there in essence. The bones are the same. Then he [Macbeth] starts to fragment, and she, as a lot of women have to when they are with men that can't stand up to what they've done, goes, “Okay. I'm going to solve this. I'm going to look after you and the mess that we're in.”

But one of the constructs that I put in Macbeth (an undoing) is the sense that Shakespeare's Macbeth is this superstructure that sits over what she might be feeling or doing. So, it becomes a dialogue between Lady

12 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS” AYANNA THOMPSON

Macbeth and my Lady Macbeth, and the necessity to bring her to the sleepwalking scene. That there is a kind of preordained heaviness, and she's fighting it all the time. One of the witches starts the play inviting the audience in. So there's a sense of playmaking, and ultimately Lady Macbeth and the play are in dialogue where she's saying, “I know I don't kill myself. I know this isn't right for me, and yet somehow, I'm ending up here in this scene with a knife. How can this be?” But still, she's managing to sort of subvert it. I think this is an experience a lot of women have.

AYANNA THOMPSON I was just about to say. I feel I know exactly what this is like as a Black woman, when you're going into something and you're like, “I know, I'm going to have to fight for this, and I already know that they're going to say that I'm an angry Black woman.” So you're constantly having that dialogue with the perception of what you are as a woman.

ZiNNIE HARRIS That's right, that there is a preordained shape you've got to take and narrative that you've got to fill, and she's going, “But this isn't right.” And that's what the kind of contemporary offer is like, the kind of discussion with other stories, and who gets to define your story. That is also true of the witches, and they say at the end, “You know you always got us wrong.” These kinds of women are marginalized, economically marginalized, don't have a kind of agency of their own, and therefore are feared and pushed out.

AYANNA THOMPSON Yes.

ZiNNIE HARRIS You know, we know throughout all the witch trials, which were contemporary with Shakespeare, these awful, awful stories of these women who probably knew a little bit of midwifery, and therefore, if the baby happened to die, that was their fault.

AYANNA THOMPSON But yeah, also they were Scottish. And this was written by an English author

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 13

Nicole Cooper (Lady Macbeth), Adam Best (Macbeth). Photo by Hollis King.

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS” AYANNA THOMPSON

who clearly had some sort of weird bias. So talk about working with and against Shakespeare's language.

ZiNNIE HARRIS And I think that was probably the trickiest part. So, in a way, the task of this project was partly narrative. As we've talked about, constructing something that offers an alternative to the sort of orthodox version. I always knew I would be writing contemporary material, so I had to find a way that I could work with Shakespeare's language that wouldn’t feel jarring for the audience. And that was, I think, the thing that took quite a lot of time and I'd been working up to it. Working with Webster's language was useful because Webster's language is a little like Shakespeare's. One of the things is the imagery. You could work with imagery. Drop the language slightly. I slightly raised my own into a more poetic kind of tone and there I found a kind of universe where they could meet.

What I found with Shakespeare is I went in it blithely, thinking, “Oh, that's fine! I've done it with Webster. I'll do it with Shakespeare.” Of course, you can't do that because the language is exquisite, so structured, and so well-known that you can't just go, “I'm going to slightly lower it and raise my own,” because you get this awful, cod Shakespeare that nobody's going to want to listen to. And what's the point? But not only that, but with Macbeth, you know that the audience knows enough to know the top 10 speeches. So, I realized pretty quickly that if it was Shakespeare, it had to be Shakespeare. Therefore, I had to find a way to have contemporary language that sits alongside it, that the audience is going to be able to move in and out of so seamlessly that they're not going to be sitting going, “Somebody's just changed gears.”

One of the mechanisms was to create a way of taking them around the first corner that wasn't going to feel jarring. So, we start with a piece of kind of contemporary language. Carlin, who is a kind of amalgam of the Porter and a witch, starts with, “Knock Knock. Who's there?” And that brings us in.

I suppose that says straight away there are going to be bits of contemporary. But also in the first Lady Macbeth scene, the majority is pretty much Shakespeare's short scene. And then, just as they're going off to get ready for the dinner that night, Lady Macbeth tends to Macbeth and says,

“Hang on! What's that on your sleeve?” And it's a ladybird. There's something about that the sort of symbolism, that it's too early in the year for ladybirds. It’s almost like the witches have brought in the supernatural and it allows a glitch in the world for us to move between the two.

And once you've established that with the audience, they go with you. It isn't just the poetry. It's the way that language is used in imagery that, you can pick up the baton. We don't do that so much in contemporary plays. But why not? So Lady Macbeth, in a scene that is entirely written by me, sits alongside that within their relationship. It's talking about people and describing them in a way that uses imagery, that allows an audience to bridge. So it's not that the contemporary is domestic and plain, and the Shakespeare is poetic and full of imagery, but actually that you can blend the two.

When I'm talking about the difficulty of the language or the challenge of the language, I'm blessed in having, across the whole company, particularly in Lady Macbeth and Macbeth, actors that are classically trained and have that fluency with Shakespeare. It doesn't feel like a foreign language so they can seamlessly go into the contemporary.

AYANNA THOMPSON

That’s so interesting because the historical linguist, Jonathan Hope wrote an article about how the language in Macbeth is very unusual, and he says, it all comes down to the word “the.” This is a play that uses “the” more than any other play. So, for example, there's the owl, right? “It was the owl that hooted” which suggests that this is an owl that you already know. So he says that at the linguistic level, you can hear that this is a play that's interested in saying there are things that the audience will never know, because they happened before, and the characters have some familiarity with it which is weird, right?

ZiNNIE HARRIS

One of the lines I love is, “How is the night at odds with morning,” and this sense that everything always has an opposite. But, however you encounter it, we're kind of talking in black and white terms all the way through, and you can pick that up as a writer. You can pick up the button of that and go, “I can take that ingredient into my writing.”

AYANNA THOMPSON

Yes, but it does take an extraordinary writer like you, who has such a finely

14 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

“THE REINVENTION OF FEMALE ANTAGONISTS” AYANNA THOMPSON

tuned ear to be able to do that. A lesser playwright wouldn't be able to do that. And I just think it's an extraordinary piece. Is there something that you'd like the audience to know either going in or what you want them to think about coming out of the production?

ZiNNIE HARRIS I'd like them to think about stories and the sort of orthodoxies we've been given, and what the alternative view might be. And how you can change a story so much by changing the point of view or lens.

I think it's also something about… we can be playful with these old texts. Macbeth in the original is going to survive me, right? We can be quite robust with them, and interrogate them. And you know, I think that's part of the gift of all these Shakespeare plays: all of them at their core are an exploration of what it means to be human, what humanity is really. And that's as relevant now as it was then. Some people, I think, feel like we have to revere it. And I think, no, it's a story that speaks to now as much as anything else.

AYANNA THOMPSON No, totally, and I think you're right. Although I'm always suspicious of people saying that Shakespeare would love it, because who cares, but I think in some ways Shakespeare would love what you're doing. Because, of course, he created very few plots on his own, and Macbeth was not one of them. He was interested in showing different points of view and telling tales from a different perspective. So, I think there's something about what you're doing that is very Shakespearean in and of itself.

ZiNNIE HARRIS That's nice to hear. I say to my students that every piece of creation is, in a way, an adaptation. We're always drawing from sources, whether we know the sources or not. And even if you're life-writing, you are adapting in some ways. So I agree with you. I think that Shakespeare was very much saying, “Here's the bare bones of a story. And this is what I want to use it to talk about.”

AYANNA THOMPSON One last question, what are you working on now?

ZiNNIE HARRIS It’s sort of hard to say since things haven't been announced, but I am working on a new play.

AYANNA THOMPSON Is it an adaptation, or is it a new play?

ZiNNIE HARRIS Well, there are two things. One is, I'm working on a new musical, that has sort of stretched me in so many kinds of good ways, because in working on the book, you're not the only author. Half of the job, maybe even two-thirds, is being done by somebody else. So, you have to be there with your skills and drive the process because you're being asked to make the superstructure, but conceding a lot of the moments to someone else. Thank God, I'm working with an absolutely brilliant writer and librettist. That’s happening next year, and then an original play, which I'm sort of just starting to doodle with at the moment.

AYANNA THOMPSON It's wonderful. Thank you so much for your time..

AYANNA THOMPSON (Chair, Council of Scholars) is a Regents Professor of English at Arizona State University, and the Director of the Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies (ACMRS). She is the author of Blackface (Bloomsbury, 2021), Shakespeare in the Theatre: Peter Sellars (Arden Bloomsbury, 2018), Teaching Shakespeare with Purpose: A Student-Centred Approach , co-authored with Laura Turchi (Arden Bloomsbury, 2016), Passing Strange: Shakespeare, Race, and Contemporary America (Oxford University Press, 2011), and Performing Race and Torture on the Early Modern Stage (Routledge, 2008). She wrote the new introduction for the revised Arden3 Othello (Arden, 2016), and is the editor of The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Race (Cambridge University Press, 2021), Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance (Palgrave, 2010), and Colorblind Shakespeare: New Perspectives on Race and Performance (Routledge, 2006). She is currently collaborating with Curtis Perry on the Arden4 edition of Titus Andronicus. In 2020 Thompson became a Shakespeare Scholar in Residence at The Public Theater in New York. In 2021, she joined the boards of the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Folger Shakespeare Library, the National Parks Arts Foundation, and Play On Shakespeare. Previously, she served as the President of the Shakespeare Association of America, one of Phi Beta Kappa’s Visiting Scholars, a member of the Board of Directors for the Association of Marshall Scholars, and a member of the Woolly Mammoth Theatre board.

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 15

DIALOGUES RENAISSANCE WOMEN: A NEW BOOK CELEBRATES—AND SELLS SHORT—SHAKESPEARE'S SISTERS

BY CATHERINE NICHOLSON

This essay originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of The Yale Review.

THE GREAT PROBLEM” of women and literature, as Virginia Woolf defined it in A Room of One’s Own (1929), is a problem in two senses of the word. There is the practical question of how women with the ability and the desire to write might succeed in doing so, and then there is the historical question of why so very few women have. Woolf’s answer to the first question takes the form of an aphorism: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Her answer to the second is a story: “Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith, let us say.”

The brief and tragic life of Judith Shakespeare unfolds over a single vividly plotted paragraph. Born in Stratford-uponAvon, she possesses every ounce of her older brother’s talent and ambition but has none of the privileges or protections of his sex: “She was not sent to school. She had no chance of learning grammar and logic, let alone of reading Horace and Virgil.” To avoid an unwanted marriage, she runs off to London, tries and fails to find work, gets pregnant out of wedlock, and dies by suicide before her twentieth

birthday. It must have been thus: a woman in Shakespeare’s day with Shakespeare’s genius could only have squandered it, but, Woolf adds, “it is unthinkable that any woman in Shakespeare’s day should have had Shakespeare’s genius.”

Unthinkable because, although genius is ineffable, the conditions for its realization, what it needs to get “itself onto paper,” are concrete: time and quiet, access to books and freedom from interruption, a full belly and a reasonably comfortable chair. As Woolf puts it, “Intellectual freedom depends upon material things . . . Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor.” Therefore, the woman “who was born with a gift of poetry in the sixteenth century” was necessarily and irredeemably stymied: “All the conditions of her life, all her own instincts, were hostile to the state of mind which is needed to set free whatever is in the brain.”

Conjuring that state of mind leads Woolf to Shakespeare, placid, discreet, and chameleonic, rich in invention and devoid of self-interest:

His grudges and spites and antipathies are hidden from us. We are not held up by some “revelation” which

16 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

Liz Kettle (Carlin). Photo by Ellie Kurttz.

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

reminds us of the writer. All desire to protest, to preach, to proclaim an injury, to pay off a score, to make the world the witness of some hardship or grievance was fired out of him and consumed. Therefore his poetry flows from him free and unimpeded.

As the portrait of a poet who wrote with the primary aim of making a living and—if titles like As You Like It and What You Will are anything to go by—some fleeting irritation at having to do so, Woolf’s tribute to Shakespeare is idealized at best. More troublingly, as a template of poetic sensibility, it is at stark odds with the circumstances of early modern women’s lives as Woolf herself imagined them. Indeed, Woolf’s paean to Shakespeare’s “free and unimpeded” art seems designed not simply to explain but to guarantee the exclusion of women writers from the literary canon. Stunted by hardship and maddened by constraint, by her lights, they could only have written badly or not at all.

“Woolf had good reasons for her pessimism,” says Ramie Targoff in her new book, Shakespeare’s Sisters: How Women Wrote the Renaissance, rehearsing the list of forces that conspired to “drastically reduce” the scope and possibilities of early modern women’s lives. They were almost universally denied formal education, legally and economically subordinated to first their fathers and then their husbands, and barred from any form of political participation and most professions—including, famously, the stage. Given their programmatic exclusion from nearly every sphere of learning, law, wealth, politics, art, entertainment, exploration, experimentation, and civic engagement in which the culture of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century England was forged, it makes sense to wonder, as Joan Kelly does in the title of a classic essay from 1977, “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” Drawing on the intervening decades of rich research by historians and literary scholars, Targoff answers confidently that they did.

Running through the whole, behind and beyond the pyrotechnics of form, is a voice of complaint, the psalmist’s ceaseless song of pleading and rebuke.

Shakespeare’s Sisters tells the occasionally interlocking life stories of four women writers born in the latter half of the sixteenth century: Mary Sidney, Aemilia Lanyer, Elizabeth Cary, and Anne Clifford. Each married and bore

children. None went to school, though three were raised in homes with private tutors. Indeed, Sidney, Cary, and Clifford were not simply well-off but wealthy, daughters of the English aristocracy or heiresses who married into it. In this respect, Woolf’s instincts about the material requirements for artistic creation were perfectly sound. Only Lanyer, the daughter of a musician, offers any resistance to her dictum about the need for money and a room—better yet, a country house—of one’s own. But the stories of all four women testify, often in startling ways, to the limits of Woolf’s assumptions about early modern women’s eagerness and capacity to create literature. Among them they produced translations of scripture and Seneca, masques and tragedies, history and autobiography, sonnets, verse epistles, psalms, and a book-length poem on the Crucifixion as seen through the eyes of women. Targoff’s protagonists did not simply write poetry and prose; they identified themselves as writers. “Their writing largely defined who they were and how they wanted to be remembered,” she declares. “Writing was their life force.”

In every case, however, writing was tangled up with frustration and loss: with death, disinheritance, marital disputes, legal troubles, religious anxieties, financial disappointments, loneliness, and humiliation. Their circumstances inarguably constrained them. Targoff’s subjects are superbly gifted, but their gifts flourished in what Woolf would have seen as lesser forms like translation and diary-keeping, devotional verse and closet dramas. Worse yet, just as Woolf suspected and feared, their subordination as women left legible imprints on their work, marks of haste, distraction, insecurity, anxiety, and rage. The recuperative impulse and celebratory ethos of Shakespeare’s Sisters does not allow for much lingering on these imprints—for noticing, pondering, interpreting, and even cherishing them—but doing so is one of the chief rewards of reading early modern women writers. Spend enough time in their company, and you realize that the great problem of women and literature has a third dimension, one that implicates us: how to reckon with genius that is impeded and unfree.

STRIKINGLY OFTEN in Targoff’s account, writing follows on disaster. For Mary Sidney, 1586 was an annus horribilis: the loss of her three-year-old daughter was followed by the death of her father, Sir Henry Sidney, and then—horribly, from a gangrenous wound—of her beloved

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 17

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

elder brother Philip, who had written his prose romance Arcadia specially for her. Grief seems to have catalyzed Mary’s creativity, turning her from a passionate reader to an increasingly bold and experimental writer who sought to salvage wisdom from the wreckage of faith. She began, in 1590, with a pair of translations from French, one a treatise on Christian stoicism and the other a tragedy about the death of Marc Anthony. In 1592, in an unprecedented choice for the wife of a nobleman (Mary had been wed at fifteen to Henry Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke), she published them with her name attached.

Next she turned—or perhaps returned—to a legacy of her lost brother, an unfinished translation of the Hebrew Psalms into English verse. Philip had drafted forty-three poems, which Mary revised, and to which she added the remaining 107. The resulting collection of 150 poems is not simply a full and astonishingly deft rendering of the biblical song cycle into the vernacular; it is also a virtuosic test of the formal capacities of English poetry. Targoff observes that, unlike the earlier, collaboratively authored version known as the Sternhold and Hopkins Psalter, “the Sidney Psalter bears no relation to liturgy: it’s a work of literature.” Like the pastoral eclogues Philip wrote to adorn the Arcadia, Mary’s translation of the Psalms is a dazzling compendium of prosodic possibilities.

There are ballad stanzas and sonnets; hexameters, tetrameters, and ottava rima; triple rhymes and internal rhymes; long lines and short lines; rhyme schemes that repeat and rhyme schemes that reverse palindromically. Psalms 111 and 119 are both alphabet poems; Psalm 117 is an acrostic spelling out PRAISE THE LORD. Running through the whole, behind and beyond the pyrotechnics of form, is a voice of complaint, the psalmist’s ceaseless song of pleading and rebuke, whose theme is abandonment and whose audience is God himself.

The finished Sidney Psalter circulated in manuscript, first among Mary’s family and friends and then more widely, eliciting admiration and acclaim. However, not everyone credited Mary with the achievement. Several surviving copies of the psalter attribute the poems solely to Philip Sidney, while Sir John Harington speculated that the bulk of the work had been done by Mary’s chaplain. “It was,” Harington avowed, “more than a woman’s skill to express the sense so right as she hath done.” Mary herself seems to have hesitated to claim the position of author. In a lavish folio manuscript prepared as a presentation copy, perhaps for Queen Elizabeth, a prefatory poem by Mary dedicates the psalter “To The Angel Spirit of the most excellent Sir Philip Sidney,” ascribing its “divine” aspects to his pen and apologizing for her “presumption” in adding to them. In

18 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

Portrait of Mary Sidney (1614-1616). Arist unknown.

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

the years that followed, she began to devote her literary energies to patronage, but though she was hardly left destitute when her husband died in 1601, she lost her sway as a potential benefactor. She also seems to have stopped writing. “Her accomplishments were by no means erased,” Targoff hedges, but her star had unmistakably faded.

And yet. A series of letters sent between 1614 and 1616 from Spa—where Mary enjoyed a surprisingly lively retirement, shooting pistols, smoking tobacco, taking a lover (or so it was rumored), and palling around the Belgian resort town with the wife of a European count—hints at a late-life resurgence of creative power. Writing to her friend Sir Tobie Matthew, she promises to send a copy of “my translation,” which Targoff speculates may have been of the poems of Petrarch. A later letter makes tantalizing reference to “this Nothing, which yet is all that I have been able to get,” and assures him that more work will follow soon (nothing of the “Nothing” survives). In a portrait of Mary by the Dutch engraver Simon van de Passe, dated 1618, the Dowager Countess of Pembroke appears richly and conventionally robed, ruffed, and bejeweled and unconventionally crowned with a laurel wreath. As in many portraits of well-bred women of the time, she holds in her hands a little book of prayers, an emblem of her pious devotion. But the words “David’s Psalms” appear along the edge of the volume, marking it as an emblem of poetic achievement. The book Mary reads is the book she herself had written.

Even so, the brass tablet on Mary Sidney’s casket hailed her as “Sidney’s sister, Pembroke’s mother,” which, as Targoff observes, is a “crushingly male definition of her identity.” Sidney comes first in Targoff’s pantheon of women writers not only because she was the eldest and best known but also because her case establishes the steep odds against them. If a woman with the Countess of Pembroke’s resources and connections had her achievements subordinated (or simply reassigned) to men, what hope was there for anyone else? The case of Elizabeth Cary underscores the point, but it also hints at the unexpected affordances of social exclusion. On the face of it, the fate of Cary’s History of the Life, Reign, and Death of Edward II offers an enraging instance of gender bias. First printed in 1680, forty years after her death, Cary’s bold retelling of the fourteenth-century monarch’s notorious career was misattributed by its publishers to her estranged husband

Henry, Lord Falkland, a “gentleman . . . above fifty years since.” Never mind that, unlike his prolific, prodigiously gifted wife, Henry was known not as a writer but as a soldier and a courtier. Never mind, too, that “The Author’s Preface to the Reader” was signed “Elizabeth Falkland.” “Very few,” the publishers assured readers, could have “express[ed] their conceptions in so masculine a style.”

The owner of that style was indeed exceptional. Born to a wealthy lawyer who delighted in and encouraged her ability, Cary translated Latin and French as a child, argued with her father about Calvinism, and had the poet Michael Drayton for a tutor. But her marriage at seventeen, in 1602, to the fashionable and footloose Sir Henry Cary forced her into an unhappy domesticity, thanks partly to a mother-in-law who disapproved of her learning, took away her books, and confined her to her bedchamber, and partly to Henry himself, who spent her fortune freely while she bore him eleven children over a span of twenty-three years. Pregnancy and childbirth were hard for Elizabeth. After giving birth, as her daughters later recalled, she suffered episodes of “deep melancholy” and fits of “plain distractedness.” “Transported with her own thoughts [she] would forget herself, where she was and how attended.” But despite such an abundance of circumstances “hostile,” as Woolf would no doubt have judged, to art, Elizabeth continued to write. Indeed, hostility was her specialty. While shut up at her mother-in-law’s, her output included poems, plays, and various “things for her recreation,” including a life in verse of the bloodthirsty Scythian warlord Tamburlaine, who seized his bride in battle and put helpless virgins to the sword. After Cary began bearing children, she undertook a closet drama about the suffering of the virtuous Hasmonean princess Mariam at the hands of her cruel husband, Herod the Great. Mariam is a moral exemplar, but she is no patient victim. When she hears a rumor of Herod’s death, she weeps for joy; when he murders her relatives, she announces that she will never sleep with him again: “Yet had I rather much a milkmaid be.” Remarkably, The Tragedy of Mariam was published in 1613 and attributed on its title page to “that learned, vertuous, and truly noble Ladie, E. C.”

Henry Cary seems not to have objected to this print debut, but he objected furiously to Elizabeth’s growing interest in Catholicism. When, in 1626, she “declared herself...

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 19

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

a Papist,” she was cut off financially, lost custody of her four youngest children, and was placed under house arrest by order of King James I. It was a catastrophe—and an opportunity. Over the next two years, living with a single serving woman in “a little old house” ten miles outside of London, Cary completed two massive literary undertakings: the translation of a nearly five-hundred-page defense of the Catholic faith by a French cardinal and The History of Edward II. Christopher Marlowe’s version of Edward’s tragedy for the late sixteenth-century stage had focused on the king himself, portraying his struggles with rebellious councilors, his passionate attachment to a male favorite, and his brutal murder. Cary’s account pays equally close attention to Edward’s neglected queen, Isabella, “in name a wife, in truth a handmaid.” Although Cary’s Isabella comes to regret the relatively small part she plays in Edward’s downfall, she regrets its smallness even more, “tast[ing] with a bitter time of repentance what it was but to be quoted in the margin of such a story.” Cary was determined that Isabella’s fate would not be her own. Following Henry’s death from a hunting accident in 1633, she regained custody of her youngest children, whom she smuggled to France to be reared as Catholics, and secured from her eldest son a modest annual allowance. In her final years, according to her daughters, “her whole employment” was “writing and reading.”

To be made a pariah was, for Cary, a strange sort of boon. It released her from a life dominated by the demands of family and society into a freedom that was at once marginal and entirely her own. Though she would have been loath to admit it, disinheritance accomplished a similar transformative magic for Lady Anne Clifford, the cosseted only child of George and Margaret, the Earl and Countess of Cumberland. Presumed to be the heiress to a fantastic fortune, Anne was raised in luxury. Items from an expense book kept by her governess include “[m]usicians for playing at [her] chamber-door,” embroidery silk and silkworms, a month of dancing lessons, a masque, her portrait painted on canvas, “11 bunches of glass feathers,” and “2 dozen of glass flowers.” Though she had the poet Samuel Daniel for a tutor, Anne’s father set strict limits on her education. Reading was one thing: Anne had access to a lavish library of English books. Writing was another: among various luxuries and frivolities, the expense book includes an entry for “two pap[er] books, 1 for account, the other to write her catechism in.” Account-keeping and spiritual exercises, the

care of one’s estates and the care of one’s soul, were the only acceptable uses for a young lady’s pen. But at some point in her late teens or early twenties, reeling from the discovery that her father had written her out of his will in favor of a pair of male relations, Anne Clifford began to use her paper books for something else: a record of her own experiences from one day, month, and year to the next. Today we might call it a memoir. Anne called it The Life of Me.

Over the course of the next sixty-some years, through two marriages, the births of two daughters, the death of her beloved mother, and an all-consuming, unrelenting legal battle to recover her lost paternal legacy, Anne filled countless paper books with the consequential and inconsequential details of her existence, including visits from friends and neighbors, quarrels with her husbands, bouts of depression and ill health, ups and downs in her ongoing lawsuits, the arrival of children and grandchildren, and the memory of an occasion on which “I ate so much cheese that it made me sick.”

In 1643, having outlived both of the male relatives to whom she lost her inheritance, Anne recovered the vast Clifford estates and with them access to a trove of family records. Over the next three decades, The Life of Me was incorporated into a still larger project of selfcommemoration, a compendium of legal documents and family histories that Anne dubbed her Great Books of Record. About five-sixths of the more than a thousand handwritten pages in the three oversize folio volumes chart the fortunes of the Clifford dynasty, from the twelfth century through the late sixteenth. The remaining pages are all Anne. The details of her last days, from January through most of March of 1676, are recorded in one final paper book. A deaf woman from the almshouse brought too much lace to the house and was scolded for it; a beloved dog had puppies, “but they were all dead”; the local schoolmaster paid a visit. She died on March 22, her account books—the catechism of her existence—complete.

THE LOSSES AND DISAPPOINTMENTS of Mary

Sidney, Elizabeth Cary, and Anne Clifford mark their writing with what Virginia Woolf would have seen as the stigmata of sorrow, although none of them was ever as imperiled as Woolf imagined Judith Shakespeare to be. The last of Targoff’s four protagonists came remarkably close to Judith’s

20 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

fate. In 1587, eighteen-year-old Aemilia Lanyer, daughter of an Italian, likely Jewish, immigrant court musician and his common-law English wife, found herself orphaned, friendless, and near-penniless in the city of London. Like Woolf’s imagined heroine, Lanyer sought protection in an affair with an older man, and, also like her, she eventually became pregnant. But here history diverges startlingly from myth. Where young Judith Shakespeare takes up with the playhouse impresario Nick Greene, Lanyer caught the eye of Henry Carey, Baron Hunsdon, Lord Chamberlain of England, cousin to Queen Elizabeth herself, and a married father of thirteen. When she realized she was expecting his child, rather than kill herself to avoid ignominy, Aemilia informed Hunsdon, who wed her to a member of his staff, Alfonso Lanyer. It does not seem to have been an especially successful union, but Aemilia would later look back on the affair that had prompted her marriage with equanimity and a hint of pride. The old Lord Chamberlain, she reflected, “kept her long . . . maintained her in great pomp,” and “loved her well.” Her years as his mistress were, in many ways, the happiest time of her life. If their relationship had not ended, she might never have written a word.

Freedom was never what Lanyer most craved for herself. Instead, poetry was a demand for recognition and attachment, not a consolation for exclusion but its intended remedy.

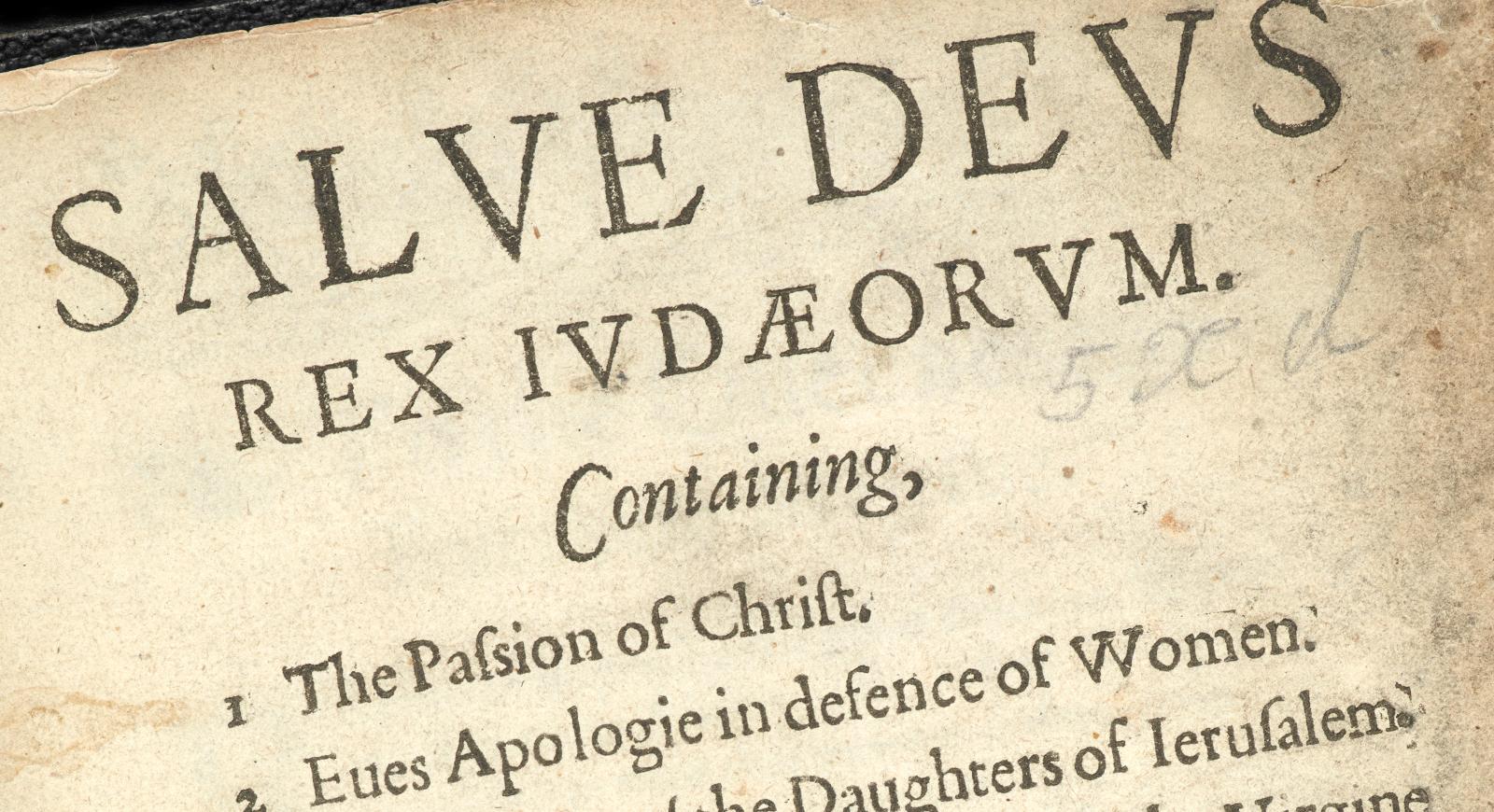

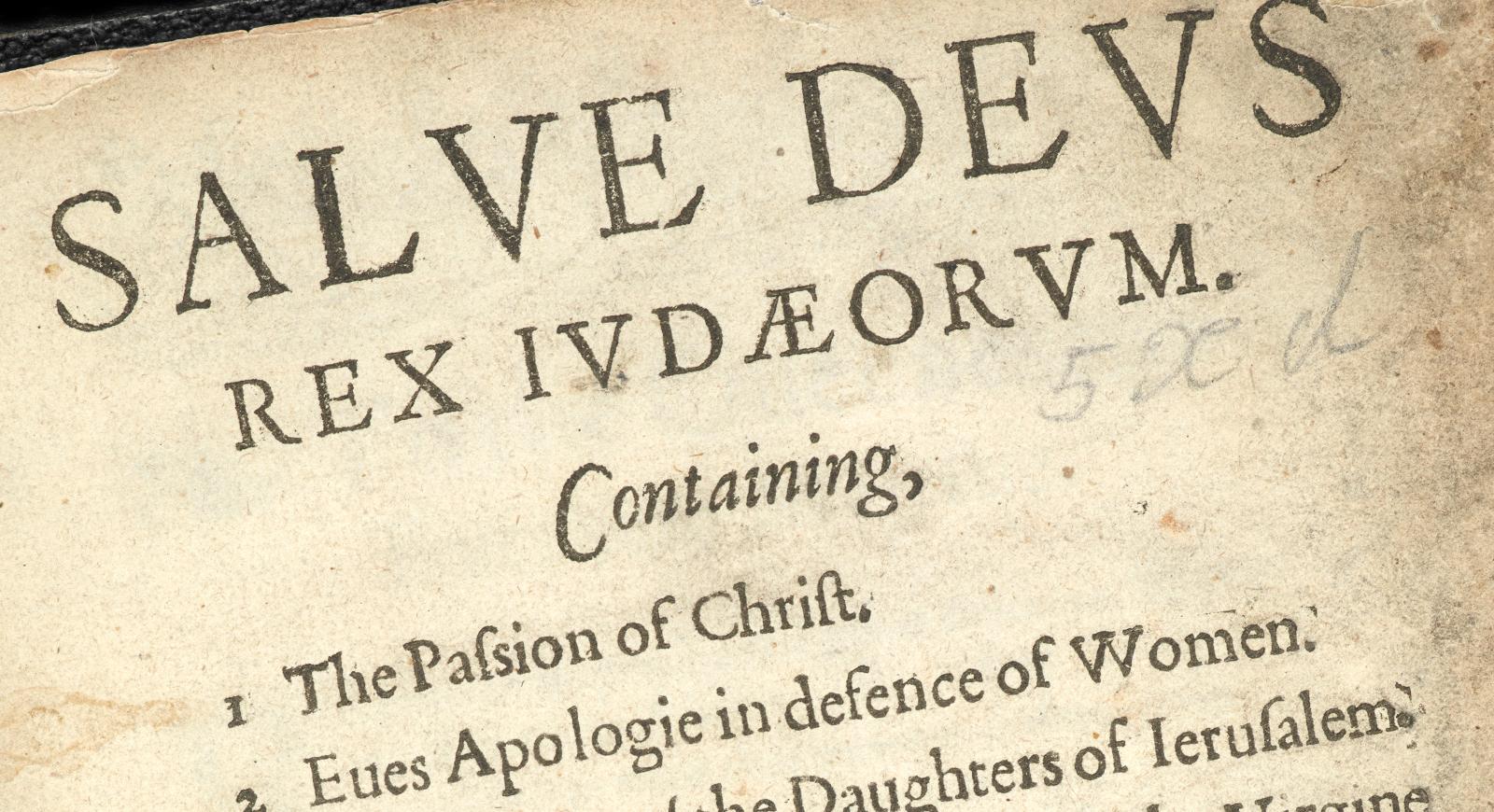

Much of what we know about Lanyer comes from the prurient case history of Simon Forman, a London astrologer and medical practitioner whom she consulted about her efforts to conceive a child with Alfonso. Forman’s records reveal how Aemilia struggled, in her marriage and on the fringes of court society, but also how she thrived, naming her baby Henry (after his well-known father) and lobbying keenly for her husband’s promotion. When those efforts proved unsuccessful, Lanyer parlayed her connections into a place in the household of Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland and mother to young Anne. The association did not last—she seems to have spent just a few months with Margaret and Anne in the summer of 1604—but it proved pivotal for Aemilia. Through some alchemy of affection and envy, Lanyer’s time with the Cliffords made her a poet. In October 1610, a volume titled Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum was entered in the records of the London Stationers’ Company, and in 1611 it appeared in print, “[w]ritten,” as the title page announces, “by Mistris Aemilia Lanyer.”

The contents were remarkable. The book opens with a collection of dedicatory epistles in verse and prose summoning the attention and support of an exclusively female readership, from Queen Anne herself to “all vertuous Ladies in generall.” This is followed by a long

MACBETH (AN UNDOING) 21

"Portrait of Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941), a British author and feminist, with her chignon." Photo by George Charles Beresford.

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

narrative poem in ottava rima, retelling the story of the passion of Christ from the perspective of the Gospels’ female characters. Lanyer’s adaptation of scripture is allusive, emotive, and strikingly free. She digresses to consider, among other subjects, the creation of the world, the paradox of redemption through suffering, the erotic career of Cleopatra, the martyrdom of St. Stephen, and the conjunction of Christ’s divinity and humanity. Throughout the poem, Lanyer repeatedly foregrounds the unjust plight of women, yoking their sufferings to the suffering of Jesus and holding the patriarchy responsible for it all. In one memorable detour, she endows Pilate’s wife—a figure who appears in a single verse in the Gospel of Matthew—with a lawyerly and full-throated defense of Eve, the original fallen woman. Her argument gleefully inverts the orthodox doctrine of atonement, whereby Christ’s death redeems the fall of Adam. The crime of authorizing and imposing the Crucifixion, Pilate’s wife reasons, is itself so great as to dwarf and swallow up all previous trespasses, including Eve’s own: “Your indiscretion sets us free, / And makes our former fault much less appear.”

But freedom was never what Lanyer most craved for herself. Instead, poetry was a demand for recognition and attachment, not a consolation for exclusion but its intended

remedy. Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum concludes with a poem dedicated to Anne and her mother, recalling their summer together. “The Description of Cooke-ham” is a record of shared but unequal privation. As the poem begins, all three women are being forced to leave the lovely estate where they had spent the summer of 1604. “Farewell (sweet Cookeham), where I first obtain’d / Grace from that Grace where perfit Grace remain’d,” read the opening lines. The triple play on “grace”—as patronage, as aristocratic position, and as the perfection of inner and outer beauty—at once identifies the three women as versions of one another and sharply defines the hierarchical distinctions between them, as dependent, mistress, and mistress-to-be. And as the poem continues, mourning their imminent departure, it becomes clear that Lanyer feels herself doubly abandoned. Wherever Margaret and Anne are headed next, she is not coming with them.

“The Description of Cooke-ham” is often called the first English country-house poem, a genre marked by its graceful conversion of praise for a place into praise for its possessors and heirs. But Lanyer imbues the gesture with melancholy and more than a hint of passive aggression, as she labors to articulate, for the Clifford ladies and for herself, the peculiar sadness of losing something that was never really yours to begin with. Before leaving Cookham,

22 THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE 360° SERIES

Aemilia Lanyer’s Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611) © The British Library

RENAISSANCE WOMEN CATHERINE NICHOLSON

young Anne bestows “a chaste, yet loving kisse” on a tree where she, her mother, and Aemilia used to read together. Aemilia, “ingratefull Creature,” repeats the gesture, but for the purpose of stealing Anne’s kiss from the tree and keeping it for herself. The nature of this ingratitude is hard to pin down: it is Aemilia’s for the tree, which she deprives of its intended reward, and, by extension, for Anne, whose liberal affections she would jealously hoard. But it is also, though this cannot be said, the Cliffords’ ingratitude for Aemilia herself, who is unkissed, unthanked, and evidently forgotten in the rush of departure. The final lines of the poem represent it as having been solicited by Margaret or Anne in tribute, but that bond of obligation is obviously the wishful product of Lanyer’s imagining. “The Description of Cooke-ham” is not only an expression of love and regret for a place where women communed with books, trees, and one another; it is also an attempt to recreate the attachments it—briefly—sustained by fencing them in rhyming couplets, as if assonance could compensate for defects of attention and care. “And ever shall, so long as life remaines, / Tying my heart to her by those rich chaines.”

ALTHOUGH SHE INVOKES A Room of One’s Own in her title, Targoff declares at the outset of Shakespeare’s Sisters that Virginia Woolf’s own “tastes and biases” are “a topic beyond our interest here.” Why should a highmodernist preference for aesthetic impersonality govern our appreciation of works written centuries before? It is certainly true, as Targoff insists, that “There’s so much more to learn through reading women’s writing than we can measure on strictly aesthetic or formal grounds.” Reading Mary Sidney illuminates the anguish of losing a child, and reading Elizabeth Cary shows how women interpreted and revised pieties about wifely obedience. Reading Anne Clifford and Aemilia Lanyer teaches us a great deal about the relationship between gender and property, about the difficulties women faced in staking claims of ownership and the satisfaction they took in doing so nonetheless. Shakespeare’s Sisters samples a rich archive of gendered experiences, opening windows onto aspects of early modern life that are rarely, fleetingly, and often only partially visible in the writings of men. And yet, Targoff ruefully observes, “One of the questions I’m frequently asked when I talk about these writers is, are they any good? Is there a reason, people want to know, why we should bother to read them?” The questions clearly

irk her. She answers them briskly, in the affirmative, in an epilogue, but they represent an opportunity it would be a shame to miss. For if we wish not only to recover early modern women’s writing for academic study—a project well underway since the 1970s—but to claim it for readerly enjoyment, we will have to confront the matter of taste.