Mule Deer

DECEMBER 2022

A

Panhandle Paradox

2114 US-84 Goldthwaite, TX 76844 855.648.3341 hpolaris.com hcanam.com OUTDOOR SUPERSTORE We Ca r ry t he Utility Vehicles You N e e d and the brands you trust

Something about this time of year always brings a bit of nostalgia. The crisp, early morning air takes me back to my very first hunts with my dad. These trips were much more about spending time together than the actual hunting. In fact, it was a couple of years and a pair of eyeglasses later before my first harvest.

But these weekends were as special as some of my most successful hunts. We’d get up in the wee hours of the morning to make it to the blind from Eagle Pass before the sun came up. That was the goal, anyway. The smell of crude oil in the air always woke me up a little when we’d stop in the convenience store for a honey bun and coffee.

What I realize about those hunts now that I never appreciated at the time was the lengths my dad went to ensure I was comfortable and enjoyed the experience, just testing the edge of my comfort zone without going too far. Now that we have our own son, I’m excited and a little nervous to find this balance myself.

Raising a new generation of landowners, hunters and outdoorsmen is an incredible opportunity and a huge responsibility all in one. I can only begin to imagine some of the challenges they will face in their lifetime.

I, like many of you, am lucky enough to have been raised to love this way of life and pray my kids will say the same. But the majority of people will never have the chance to experience it without the programs put on by Texas Wildlife Association and other similar organizations.

As the year comes to a close, I hope you will consider TWA in your end-ofyear giving. Without your generosity, we cannot continue to make an impact on thousands of youth and adults through our Conservation Legacy and Hunting Heritage programs.

I hope you and your family have a very merry Christmas. Thanks for being a member of TWA!

Texas Wildlife Association

Mission Statement

Serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

TEXAS WILDLIFE is published monthly by the Texas Wildlife Association, 6644 FM 1102, New Braunfels, TX 78132. E-mail address: twa@texas-wildlife.org. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Texas Wildlife Association, 6644 FM 1102, New Braunfels, TX 78132. The Texas Wildlife Association (TWA) was organized in 1985 for the purpose of serving as an advocate for the benefit of wildlife and for the rights of wildlife managers, landowners and hunters in educational, scientific, political, regulatory and legislative arenas. TEXAS WILDLIFE is the official TWA publication and has widespread circulation throughout Texas and the United States. All rights reserved. No parts of these magazines may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without express written permission from the publisher. Copyrighted 2022 Texas Wildlife Association. Views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the Texas Wildlife Association. Similarities between the name Texas Wildlife Association and those of advertisers or state agencies are coincidental, and do not indicate mutual affiliation, unless clearly noted. TWA reserves the right to refuse advertising.

Texas Wildlife Association

6644 FM 1102 New Braunfels, TX 78132 www.texas-wildlife.org (210) 826-2904 FAX (210) 826-4933 (800) 839-9453 (TEX-WILD)

DECEMBER 2022 4 TEXAS WILDLIFE

TEXAS WILDLIFE PRESIDENT'S REMARKS

SARAH BIEDENHARN

Texas Wildlife

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 5

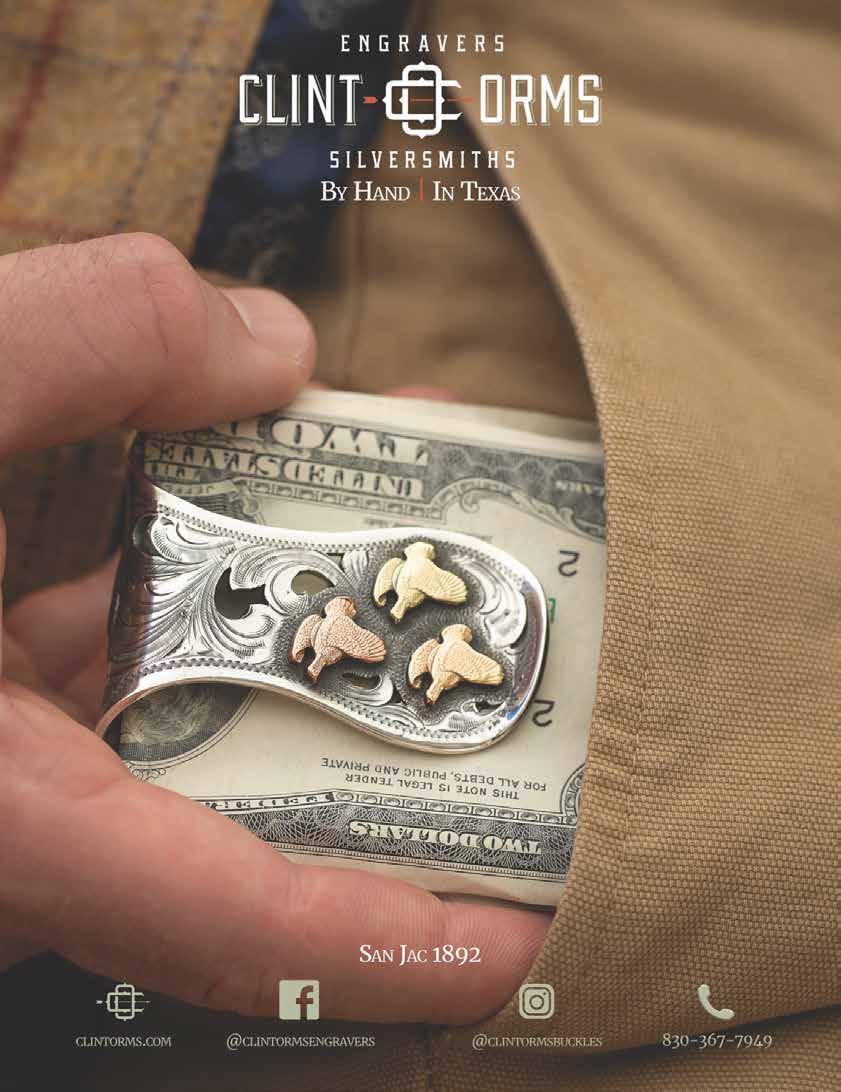

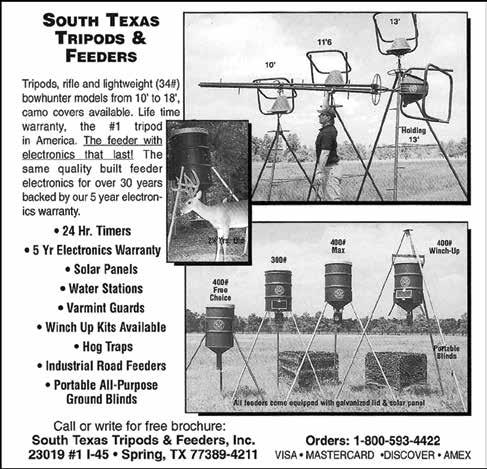

MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION 8 A Panhandle Paradox A groundbreaking study is changing the way we think about mule deer by

MATT WYATT

VOLUME 38 H NUMBER 8 H 2022 DECEMBER 22 Members In Action A Labor of Dove by KRISTIN PARMA 54 Outdoor Traditions Peace on Earth by SALLIE

46 Caesar Kleberg News Texas Deer Management Permit by JOSEPH HEDIGER, COLE ANDERSON, RANDY DEYOUNG and MICHAEL CHERRY Plant Profile Eastern Baccharis by BRAD KUBECKA, Ph.D. 24 16 Issues & Advocacy TWA Gears Up for 2023 Legislative Session by JOEY PARK 20 Conservation Legacy Year in Review Mule Deer A Panhandle Paradox Mention deer hunting and images of big Texas whitetails come to mind. But Texas is home to some massive mule deer bucks as well. That wasn’t always the case, but mule deer populations in the Panhandle and West Texas are flourishing. However, their biology and management is unique, as Matt Wyatt explains in his article beginning on page 8.

Russell A. Graves On the Cover MAGAZINE CORPS Justin Dreibelbis, Executive Editor David Brimager, Managing Editor Burt Rutherford, Consulting Publications Coordinator/Editor Lorie A. Woodward, Special Projects Editor Publication Printers Corp., Printing, Denver, CO Magazine Staff 30 A Mule Deer Question by LARRY WEISHUHN 26 TAMU News Leopold Live by SHELBY MCCAY 18 TWAF James Green Wildlife & Conservation Education Initiative by TJ GOODPASTURE 42 TRS Ranch Retreats A New Age of Ranching by LORIE A. WOODWARD 36 Stalking Palo Duro Bowhunting mule deer in the Texas Panhandle by BRANDON RAY 48 The Last Quail in Texas by DALE ROLLINS, Ph.D.

Photo by Russell A. Graves

LEWIS

Photo by

MEETINGS AND EVENTS

DECEMBER

DECEMBER 12

Houston Clay Shoot, Greater Houston Gun Club. For more information, visit www.Texas-wildlife.org or contact Kristin Parma at (800) 839-9453 or kparma@texas-wildlife.org.

DECEMBER

DECEMBER 17

Members-only Wild Game Cooking Class, TWA Headquarters, New Braunfels. For more information, visit www.Texas-wildlife.org or contact Kristin Parma at (800) 839-9453 or kparma@texas-wildlife.org.

YOUTH DISTANCE LEARNING

PROGRAMS:

• Youth Videoconferences are live interactive presentations featuring Texas wildlife species. Offered throughout the semester, classes connect via videoconference equipment or Zoom.

• On-demand Webinars are recorded interactive presentations about natural resources and wildlife conservation topics and are available anytime on the TWA website. Critter Connections are now available in a read-along format. Recordings of past issues are available online and are created for each new issue.

DECEMBER 2022 6 TEXAS WILDLIFE

FOR INFORMATION ON HUNTING SEASONS, call the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at (800) 792-1112, consult the 2022-2023 Texas Parks and Wildlife Outdoor Annual, or visit the TPWD website at tpwd.state.tx.us.

TEXAS WILDLIFE VISIT THE PROGRAM PAGES ONLINE AT https://www.texas-wildlife.org/youth-education/ for specifics and registration information.

CONSERVATION LEGACY YOUTH PROGRAMMING

TEXAS WILDLIFE

The American Badger CRITTER CONNECTIONS YOUTH MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER 2022

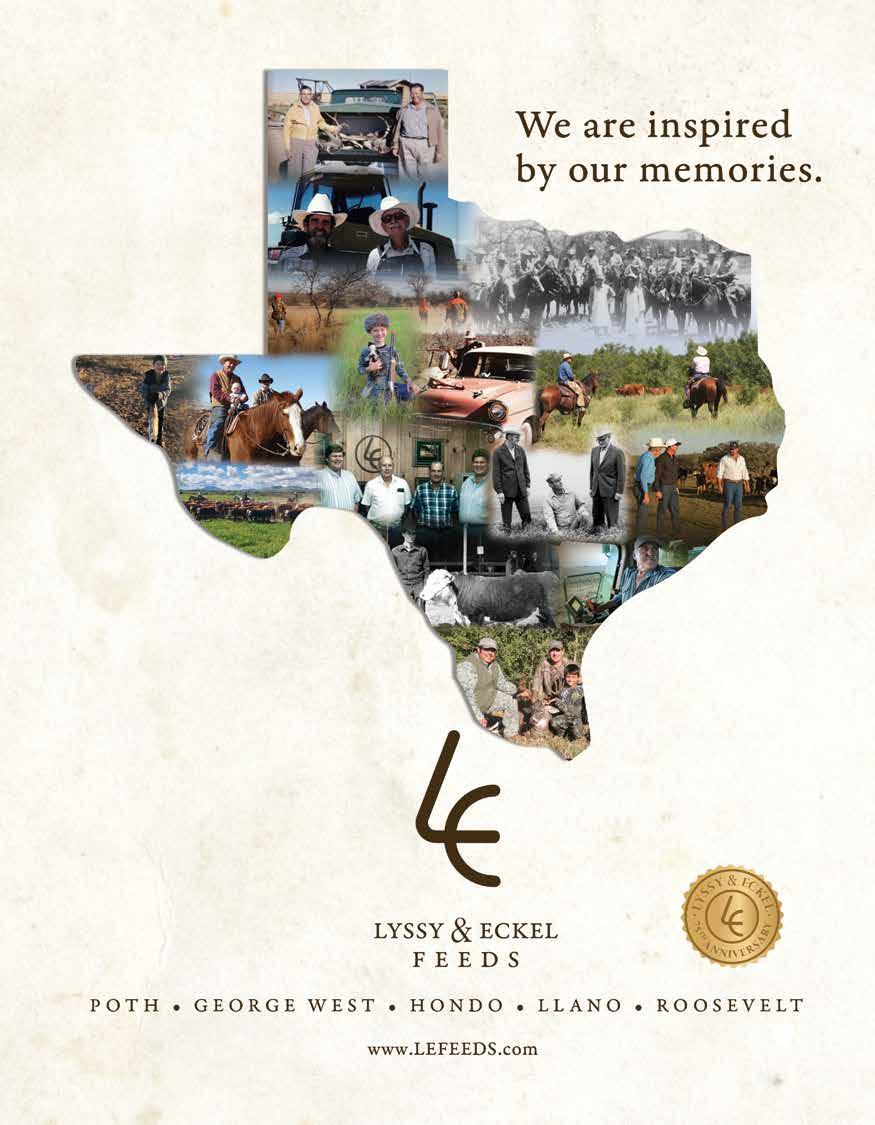

It’s generally thought that mule deer cover lots of country. Among the information discovered in Panhandle mule deer research is that deer in the Texas Panhandle travel 2 miles or less to get to cropland feed or water.

DECEMBER 2022 8 TEXAS WILDLIFE A PANHANDLE PARADOX

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

A

PANHANDLE PARADOX

A groundbreaking study is changing the way we think about mule deer in the Texas Panhandle

Article by MATT WYATT

Article by MATT WYATT

The Panhandle is a truly unique part of Texas. And it’s a truly unique place for mule deer. Across the species’ range from Mexico to Canada, few areas holding healthy mule deer populations resemble this piece of the Lone Star State.

“Mule deer are really a western, Rocky Mountain species. But at this eastern extent of their range into the Great Plains, there’s really only a handful of areas that they coincide with dense agriculture,” said Dr. Levi Heffelfinger, an assistant professor

of research for the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute (CKWRI) who led the study.

Heffelfinger said there is a great deal known about mule deer, generally speaking, thanks to studies in other parts of the country, including migration studies out of Wyoming and fawning studies in Utah.

“But we really don’t know much about the species, how they move, how their populations perform in areas that are densely agricultural,” he said.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 9

Then came a collaboration between three of Texas’ most prominent wildlife research institutions—CKWRI at Texas A&M-Kingsville, Borderlands Research Institute (BRI) at Sul Ross State Univer sity, and Texas Tech’s Department of Nat ural Resources Management—which co operated on a comprehensive Panhandle mule deer project, the first of its kind, to take a closer look at one of the least-stud ied species in the state.

This study sought to answer questions exclusive to this ag-dominated landscape, questions first brought to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologists by local farmers.

During certain times of year, some Panhandle farmers would see dozens, sometimes hundreds of mule deer congregated on their cropland.

DECEMBER 2022 10 TEXAS WILDLIFE A PANHANDLE PARADOX

Levi Heffelfinger, biologist with the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, released a mule deer buck that was captured and tagged in the Texas Panhandle. The research is a three-institution effort to gain more knowledge about mule deer in Texas.

Like much of the Lone Star State, the Texas Panhandle has its own set of environmental factors that wildlife must endure.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

Photo by Dana Wright

Landowners and biologists alike were curious about how far these deer were traveling to these fields. Where were they coming from? How much time were they spending on these fields? Does this relationship with agriculture affect hunting? Does it impact TPWD’s annual population survey?

These questions and others like them sparked the study. Some of the findings defy traditional mule deer wisdom.

THE FINDINGS

From 2015-19, Heffelfinger and his fellow researchers collared and tracked 146 mule deer across four sites with different, distinct landscapes in the Panhandle. Many of the deer provided GPS data for two years.

The first study site in the Western Rolling Plains had 51 deer collared. It covered portions of Hall and Motley counties and consisted of a mixed landscaped with a relatively even balance of agriculture and rangeland.

The second site was situated along the Canadian River Breaks near Stinnett and had much less agriculture than the other sites. The site had 45 collared deer.

The Southwest Panhandle had two sites, one in Lamb County and the other split between Yoakum and Cochran counties. The two sites had 25 collared deer each.

After sifting through the years of movement data from the sites, an intriguing paradox was discovered—although agriculture provides a significant benefit to mule deer, they barely use it.

“Out of those 146, only about half ever used agriculture at any time,” Heffelfinger said.

Meanwhile, the other half of mule deer that did use agriculture (usually early-stage winter wheat or alfalfa in the late winter

months) utilized it less than 20 percent of the time. Heffelfinger said they’re typically foraging for an hour or so then moving into rangeland.

And mule deer are not going far out of their way to access cropland when they do use it.

“If a deer happens to live somewhere where it’s more than 2 miles from agriculture, you can almost put your money on it that it will never use agriculture,” Heffelfinger said. “They’re not doing these long-distance movements… if it’s nearby in the area, they’ll use it and they’ll incorporate it into their foraging. But if it’s far away, they’re not going to exert that energy to go to that source.”

The discovery that mule deer won’t travel more than 2 miles to agriculture defies the stereotype of the species, often perceived as big movers. Think Rocky Mountains and massive migrations. In the Texas Panhandle, it’s just not the case.

The study also established a threshold for the density of agriculture a mule deer will seemingly tolerate. Researchers saw that once landscapes reached 20 percent agriculture, mule deer began using it less. Once landscapes became 40 percent agriculture or more, deer stop using it altogether.

“It becomes too much of a good thing,” Heffelfinger said. “It’s beneficial to them in some ways during certain times of the year, but if too much of their home range is just wide-open agriculture, it replaces other important aspects of their life, like hiding cover from predators or thermal cover from the hot summers or water sources.”

Deer that did use agriculture gained significant benefits. Does that used agriculture were more likely to successfully produce offspring. Deer that used agriculture had better body condition and more rump fat.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 11 A PANHANDLE PARADOX

Mule deer in the Texas Panhandle are crop-oriented feeders, especially winter wheat. Or are they? Although agriculture provides a significant benefit to mule deer, they barely use it, research found.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

Some exceedingly so.

The heaviest buck recorded on the project was 317 pounds. Researchers used an ultrasound to determine he had 2.5 inches of rump fat.

“We even had to get an extra leather strap to bolt onto the collar just to fit it around his neck. He was absolutely giant,” Heffelfinger said, adding the massive buck tried to charge the helicopter during his capture.

The 317-pounder is on the extreme end of the spectrum when it comes to mule deer size in the Panhandle. Heffelfinger’s explanation? Possibly laziness.

“There’s some of them that really seem to—and I can’t prove this—but I think they just get a little lazy. They just camp out in alfalfa fields instead of foraging for native food sources,” Heffelfinger said.

“There’s some of those bucks that can really get to some astounding size, and

you really just don’t see that in the wild populations like up in the Northwest, where they have to go through harsh winters and dry summers, whereas some of these deer in the Panhandle have that consistent food source that they can get lazy and camp out in.”

The access to agriculture is an advantage for Panhandle mule deer, but the deer not using ag aren’t suffering. It’s a mosaic of habitat needed for mule deer to thrive: shrublands, grasslands, agriculture, etc.

“If deer didn’t use agriculture, they really didn’t have poor body condition or poor body size or poor antler size or poor fawn recruitment. It wasn’t like the avoidance of agriculture was detrimental to the individual or the population… It’s not like croplands are limiting the population like they need it in order to expand. I think it’s providing this buffer,

this little extra boost for those that do,” Heffelfinger said.

“I think part of that nutritional buffer is helping to slowly grow the overall Texas Panhandle mule deer population. It’s not exploding, but it’s a very slow growth.”

The most recent estimate has 71,000 mule deer living in the Panhandle.

MANAGEMENT GAME-CHANGER

This research is a game-changer for the wildlife managers and landowners serving as stewards of this Texas resource.

“We perceived that deer were really, really using ag. Like lots of ag, all the time. And that wasn’t the case,” TPWD Mule Deer and Pronghorn Program Leader Shawn Gray said.

“Don’t get me wrong, there still can be 100 mule deer on a wheat field. That happens. But it’s not like every mule deer on the landscape is on that field at the same time.”

The study results give TPWD person nel added confidence in their popula tion survey methods and in providing hunting opportunity.

“We were extra conservative in issuing doe permits because we were thinking more of the extreme end of mule deer ranges, like they’re probably going 50 miles to ag if they have to, and that was not the case,” Gray said.

Deer movement was the study’s main focus, but because of the project’s breadth and level of expertise involved, many byproducts emerged from the massive volume of data.

For the first time, average home ranges were established for Panhandle mule deer. The average home range for does is about 2,600 acres and the average for bucks is about 9,000 acres. The study site with the largest average home range was the Yoakum-Cochran site, approximately 3,500 acres for does and 11,300 for bucks.

The growth of antler size in bucks peaked between 5.5 and 6.5 years old. The greatest leap in growth was between 1.5 and 2.5 years old. Data collected in the captures was used by TPWD to construct experimental antler restrictions to improve buck age structure and the quality of hunting in the Panhandle.

DECEMBER 2022 12 TEXAS WILDLIFE

A PANHANDLE PARADOX

Mule deer in the Texas Panhandle use agricultural crops such as winter wheat to their advantage. But deer that exist on native vegetation didn’t suffer, according to research on mule deer in the top of Texas.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

The restrictions prevent mule deer harvest with an outside spread of less than 20 inches, protecting younger deer and shifting hunters’ attention to more mature bucks. Those restrictions have recently expanded to a total of 28 counties in the Panhandle and Terrell County in the Trans-Pecos.

“One of the best things that came out of the project was that we took pictures of the bucks each year that we captured them and so we would have three years of photos of those bucks. It was a great tool to show how they progressed in their antler development,” said Dana Wright, a TPWD natural resource specialist who assisted with the project.

“Most of our mule deer bucks start out as spikes. So, to see some of these turn into nice 10-point bucks, it was very eyeopening to hunters and landowners alike on some of the changes that the bucks went through. I still get pictures from some of the landowners of some of the tagged bucks. So, I’m still keeping up with them, they’re still out there.”

Heffelfinger was also able to ascertain peak rut dates by examining significant dips in deer movement in the summer. He used these dips as the peak fawning period as deer stop moving the day after giving birth. By subtracting the mule deer gestation period (203 days), Heffelfinger was able to determine peak rut dates.

In the Western Rolling Plains, the peak fawning date is July 22 and peak rut is December 30. In the Canadian River Breaks, peak fawning is June 25 and peak rut is December 3, nearly a full month before the Western Rolling Plains. In the Southwest Panhandle, peak fawning is July 13 and peak rut is December 21.

CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE

The findings from this study can help wildlife officials with disease management.

Chronic wasting disease is a threat facing North America’s cervid populations. Although many of the cases in Texas are from whitetails connected to deer breeding facilities, the disease has been detected in wild deer. More than 60 of the state’s approximately 400 cases are from free-ranging mule deer.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 13

A PANHANDLE PARADOX

Fawn survival is crucial to maintaining a robust deer population. One of the spin-offs from the Panhandle mule deer study is to track young deer to determine how they move and whether or not they expand their range.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

While mule deer bucks are what whet a hunter’s appetite, it’s the does that keep a deer population healthy. Questions from Panhandle farmers were the genesis of a first-of-its-kind study with three universities cooperating—Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M-Kingsville, Texas Tech University, and the Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

CWD is a fatal neurological disease that is spread through infectious mis folded proteins called prions. It is like scrapie in sheep, “mad cow disease” in bo vine and other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. According to the Cen ters for Disease Control and Prevention, symptoms include weight loss, stumbling, lack of coordination, listlessness, drool ing, lack of fear of people. There is cur rently no cure.

CWD has been found in free-ranging deer herds in at least 29 states and is thought to be impossible to eradicate once it becomes established on a landscape.

The disease can spread through bodily fluids like blood, urine or saliva when healthy deer come into contact with CWD-infected deer, and can also spread through contamination of soil, plants and water. Many of the ways it is transmitted are associated with deer movement.

Because of this, a better understanding of how and why deer move is a valuable tool for wildlife managers working to ar rest the disease’s spread.

The Panhandle study has already been used in the state’s efforts to manage CWD. An 8.5-year-old mule deer buck that was showing symptoms of CWD was found to be positive in the Lubbock area last year.

In response, TPWD set up containment and surveillance zones in the area where the infected deer was found. Hunters in the state’s CWD zones are required to take their harvest to check stations for testing within 48 hours.

“We actually used some of this information when we delineated our most recent CWD zone in the Lubbock area. That’s why those zones are pretty small in comparison to the Dalhart zone, because it’s extensively ag production around that area,” Gray said.

The study’s finding that mule deer don’t use landscapes with more than 40 percent agriculture resulted in TPWD construct ing a more consolidated, biologically based CWD zone in Lubbock County.

This disease management application is another unintended byproduct to emerge from the depth of the Panhandle study.

“We didn’t go into this thinking about chronic wasting disease. But as we were getting movement data and started to see where animals were congregating, it’s like ‘oh wow, this is going to be really important for figuring out size of surveillance zones, planning sampling schemes and trying to project where CWD could be going next,’” CKWRI Executive Director Dr. David Hewitt said.

WHAT’S NEXT

CWD risk in relation to deer movement will be further examined as part of another five-year study on elk, mule deer and whitetails in the Panhandle. The new study will feature the same universities that produced the mule deer project, plus Texas A&M-College Station.

The Panhandle study led by Heffelfin ger is a launchpad for future projects like the upcoming CWD study, baseline re search that provides a benchmark for the many questions that surround this spe cies in Texas.

“Since we started this project, we just got more questions that we want answered,” Wright said.

Among them is fawn dispersal, a topic that Heffelfinger is delving deeper into in the wake of some of his findings about mule deer movement. A pilot study was spawned from Heffelfinger’s curiosity of one buck fawn that was GPS collared at the Yoakum-Cochran site near the end of the Panhandle project.

This young buck wandered 43 miles northwest into New Mexico.

“One day he took off,” Heffelfinger said. Then he went “missing” when his collar failed. Until a farmer sent a photo of the collared buck in one of his fields to New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, which relayed it to Heffelfinger.

A year and a half later, Heffelfinger received another photo. This time of a buck a young hunter harvested as his first

DECEMBER 2022 14 TEXAS WILDLIFE

A PANHANDLE PARADOX

The Texas Panhandle is among the most intensely agricultural regions in the country. How does that affect mule deer populations and hunting? The results of a three-institution study discovered some counter-intuitive data.

Photo by Dave Hewitt

deer. It was the same buck, this time 2.5 years old and 30 miles east back in Texas.

Fascinated by these long expeditions, Heffelfinger has collared 30 fawns in the Canadian River Breaks to further explore these movements.

The study is still in a preliminary phase, but Heffelfinger and his colleagues have found that a significant portion of mule deer less than a year old are making these long journeys. It isn’t just the males roaming to establish a new home range, which is common in many other juvenile mammals. Heffelfinger collared two does that made 80-mile roundtrips.

“Lo and behold, about 20 percent of our sampled population are doing these extraordinary excursions,” Heffelfinger said.

Heffelfinger wants to take a closer look at this phenomenon in the coming years. The implications for mule deer management and understanding abound.

And it is just a small piece of what has sprouted from this groundbreaking study on mule deer in the Texas Panhandle.

THE COLLABORATION

Knowledge will continue to be built from the Panhandle study for years to come, thanks to the pooled resources of CKWRI, BRI, Texas Tech, TPWD, Boone & Crockett Club and the Mule Deer Foundation.

The academic cooperation of three universities on a project of this magnitude is particularly intriguing. Not to mention rare. It could also be the trend going forward.

“I think you’ll see that across the natural resource and wildlife conservation fields, is that you really can’t do things in a silo anymore. You can’t do things solo. I think everybody is learning that collaboration is really key to any good conservation work, especially when you’re talking about landscape-level projects,” said Dr. Louis Harveson, founder and director of BRI.

The expertise and resources that can be leveraged in these big projects is unparalleled when multiple universities and organizations assemble for the benefit of the resource.

“As we get away from one-off, master’s student-type research and start trying to tackle these problems in a bigger, more comprehensive way, these research coalitions and big collaborative projects are going to have real value,” Hewitt said.

The real-world application of these types of studies benefit not only wildlife managers, landowners, and hunters, but all Texans who care about wildlife, regardless of which species is studied next.

“This new collaborative model really is the future of landscape-scale research in the state of Texas and probably the country. I think it serves as a great model for the rest of the country,” Harveson said.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 15 A PANHANDLE PARADOX

High fences, for the most part, are not a prominent feature on Texas Panhandle ranches.

Photo by Levi Heffelfinger

by Matthew Grassedonio

TWA Gears Up for 2023 Legislative Session

Article by JOEY PARK

In just a few short weeks the 88th Texas Legislature will convene in Austin for the legislative session. TWA will be there representing our members, landowners, and wildlife enthusiasts across the state, as we have been for more than 30 years. Each legislative session brings its own unique challenges, and the upcoming 88th is no exception.

We will have about 30 new members of the Texas House and five new Texas Senators who will be taking their seats in Austin for the first time. Nearly 50% of the members of the 88th Legislature will have had less than four years of experience on the job. This brings an enormous challenge to help educate these policy makers about what is important for landowners and land managers who

struggle to maintain quality habitat for our state’s wildlife resources.

The state’s budget will have an unprecedented $28 billion surplus in revenue. Agencies and programs across the board will be asking for their share of that surplus. Our state’s leaders also have ideas about how to spend that money on items such as property tax relief, teacher pay raises, and a host of other topics.

DECEMBER 2022 16 TEXAS WILDLIFE

Photo

Although many parts of the state have received much needed rain in recent months, there are still areas of the state that are affected by the recent drought. The legislature will be focusing much of their efforts on water policy and state water management. Both the TCEQ and TWDB are undergoing the Sunset process which will bring changes to how each of those agencies conduct their policies on water management.

Wildlife issues will be front and center on our agenda as always. Ensuring that TPWD has the tools they need to do their important job is one of our biggest tasks each session. White-tailed deer and chronic wasting disease will no doubt be a topic of numerous bills filed next session.

An ongoing debate about managing our public oyster reefs along the coast will also be part of the session, along with mountain lions, feral cats, elk and any host of other exotic wildlife that will likely emerge in the form of proposed

legislation. As always, we will continue to keep a close eye on any legislation affecting private property rights related to eminent domain, ad valorem taxes and other issues that can impact landowners.

TWA will also be focused on the budget process for TPWD. TPWD will be asking for additional spending authority for the many millions of dollars that remain unappropriated from previous sessions. This is money from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses that we all buy each year, as well as public hunting permits, boat registrations or MLD permits. That money should be put back to work for the purposes in which it was collected— paying for biologists, game wardens, and other TPWD staff who work so hard managing our state’s wildlife resources.

TWA will track and provide input on these bills to ensure our members are not harmed by new policies or laws.

TWA members have a very unique place in the legislative process. We are the people who own and manage the private

lands in this great state. Your voices should be heard on issues that directly affect your private property.

TWA encourages all of our members get to know their state representatives and senators. Reach out to your elected offi cials and let them know what’s important to you. I can assure you that these elected officials care about what their constitu ents need and want, or don’t want in many cases.

It can be as simple as picking up your phone and making a call to their office. Let them know who you are, and let them know you would like to be a resource for their office when it comes to private property rights issues. Let them know that you care. You will find that it is a welcoming process.

TWA stands ready to help you with your advocacy needs. Our website has links to find out who your elected officials are and how to get in touch with them. Your advocacy team here at TWA is ready to help as well.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 17 TWA GEARS UP FOR 2023 LEGISLATIVE SESSION

TAKE A KID HUNTING TODAY!

Celebrating Success

James Green Wildlife & Conservation Education Initiative

Article by TJ GOODPASTURE Photos courtesy of TWAF

Article by TJ GOODPASTURE Photos courtesy of TWAF

More than 250 guests gathered at Texas Wildlife Association Foundation Trustee Bryan King’s home in Fort Worth to celebrate the successful impacts of The James Green Wildlife & Conservation Educa tion Initiative in North Texas.

In 2012, thanks to the support of the Fort Worth community and generous donors, the North Texas efforts of Con servation Legacy became known as the James Green Wildlife & Conservation Initiative. Funds raised through this ini tiative benefit Texas Wildlife Association Foundation and are designated to support the conservation and natural resource education efforts across North Texas. Since being established, the initiative has reached more than 800,000 young Texans in North Texas alone.

The James Green Wildlife & Conserva tion Initiative instills an understanding and appreciation of the outdoors and nat ural resources while sharing the message of private land stewardship. This vital message is being delivered to North Texas students at no cost to North Texas schools by trained educators who are dedicated to the region.

Many thanks to the North Texas com munity for supporting this event.

DECEMBER 2022 18 TEXAS WILDLIFE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION FOUNDATION

Thank you for your continued support and participation in Conservation Legacy programs.

Together, we are educating generations of Texas land stewards.

DECEMBER 2022 20 TEXAS WILDLIFE

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 21

TWA MEMBERS IN ACTION

A Labor of Dove

Women of the Land

Article by KRISTIN PARMA Photos courtesy of TWA

As anyone who has pulled down on a zigzagging Mourning Dove knows, bringing one down isn’t easy.

“Well, it’s done.” TWA member Emilie Bro chon leaned down and picked up her first dove harvest, a Mourn ing Dove. The birds had been slow the first morning of the hunt but Emilie, a former Marine, was ever watchful and hit her tar get without hesitation.

As she looked at the bird her voice reflected a bit of a heavy heart. Then she looked at me with a big grin and said. “But, I am going to eat him!”

This past September, 20 female TWA members gathered in Albany, Texas, for the revival of the Texas Wildlife Asso ciation’s Women of the Land program (WOTL). Having completed its 16th year, the program combines information on land management with skill-based out door recreation in a venue that encour

There’s no better way for people to bond than over a great meal, unless it’s in a hunting blind. TWA’s Women of the Land program allowed a group of ladies, some who were experienced hunters and others who were novices, to share a wonderful weekend in the dove fields.

DECEMBER 2022 22 TEXAS WILDLIFE

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

The smiles say it all. These ladies share not only their success but their enjoyment during TWA’s Women of the Land dove hunt.

ages Texas women to become active land managers, develop and hone their management skills, and network with other TWA members. This workshop focused on one of Aldo Leopold’s tools of wildlife management—the gun—and was an experiential dive into dove hunting, habitat, and ecology.

The first day began with introductions and moved straight into shotgun safety and best practices with TWA members Ricky Linex, Ryan Walser, and Tamara Trail at the helm. The steady wind where West Texas meets the Panhandle never ceased to blow and the sun was hot at the 5-stand range, but the ladies immediately bonded over the sport of busting clay pigeons. The day culminated in a wild game dinner featuring venison and wild boar sausages, panko-crusted pheasant, cast iron-seared duck, and unique wonton appetizers featuring dove cooked to medium rare perfection.

The next two days, hunts ended with several first-time har vests, giving the room to discuss processing techniques. Aman

Many of the ladies were novice bird hunters, but they were in the company of experienced outdoors enthusiasts including members Misty Sumner and Rachel Bartoskewitz, who shared their love and passion for hunting heritage and TWA’s mission. Biologist Annaliese Scoggin shared her experience banding and monitoring dove for Texas Parks & Wildlife Department and led a discussion on dove ecology.

A big thank you goes out to the event sponsors: C1 Insurance, Triumph, Big Country Concierge Services, McKenna Quinn, and the welcoming community of Albany. It was a memorable weekend of outdoor connection that only a program like Women of the Land can provide.

So, what does it mean to be a Woman of the Land? I posed this question to the group and hope that they reflected on it as they progressed through the weekend.

For me, becoming a Woman of the Land isn’t something you attain by studying hard or passing an exam. It is not a tangible certificate I can put on my wall, but a commitment to continue to learn about, honor and connect with the land. It is uniting with women from all backgrounds and beliefs, not just those who are likeminded, and finding common ground to support one another. Programs like Women of the Land inspire me to continue to hone my crafts, mentor others where I can and connect with the wild around me.

TWA is planning to host more ladies-only events for our new and long-time dedicated members. Whether in the field or the classroom, or in combination, we look forward to ushering in more Women of the Land for years to come.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 23 TWA MEMBERS IN ACTION

da Gobeli, TWA’s Conservation Education specialist and propri etor of the WOTL program, landed her first bird.

A trip to the 5-Stand range gave participants in TWA’s Women of the Land dove hunt a chance to hone their shooting skills before heading out to the dove fields.

While enjoying the harvest at mealtime is an important part of the hunt, enjoying the awesome beauty of the outdoors makes the excursion complete.

“Such a unique group of people coming together to enjoy being outside and the fellowship it provides…getting my first dove was the cherry on top!”

— SaraBeth Boggan, new TWA member

Eastern Baccharis

Baccharis halimifolia

Article and photos

by BRAD KUBECKA, Ph.D.

When early

and Blackland Prairies of Texas during the 1830s, they collectively catalogued and characterized more than a thousand plant species. Today’s landscape, however, is strikingly different from what Drummond and Lindheimer observed.

scoured the

A noteworthy absence in the writings of Drummond and Lindheimer was Eastern baccharis (Baccharis halimifolia; pronounced bak-ah-ris), a native shrub that offers little value to game animals of Texas but is now quite abundant in the eastern third of the state.

Eastern baccharis is a member of the Asteraceae (sunflower) family reaching 10-12 feet tall and flowers October – November. The fuzzy, white pappus of female flowers that begin to appear in October is visually unattractive compared with other plants in the Asteraceae family. The pappus aids in wind dispersal of seeds up to 150 yards which allows it to be quite effective at colonizing nearby disturbed soils.

Eastern baccharis is a prolific seed producer with seeding rates ranging from 10,000 to more than 1 million seeds per fe

DECEMBER 2022 24 TEXAS WILDLIFE TEXAS WILDLIFE PLANT PROFILE

botanists Thomas Drummond and Fer dinand Lindheimer

Gulf Coast

Female flowers of Eastern baccharis. The fuzzy, white pappus of female flowers that begin to appear in October aids in wind dispersal of seeds up to 150 yards, which allows it to be effective at colonizing nearby disturbed soils.

Eastern baccharis invading an upland area. The plant is beneficial for preventing soil erosion along riparian zones but can become weedy in upland areas.

Male flowers of Eastern baccharis.

male plant (male and female reproductive parts are found on different plants). Seeds are small (0.10 mg) and offer virtually no food value for seed-consuming wildlife; the browse palatability for wild ungulates is poor and potentially toxic to livestock.

However, 14 percent of Red-winged Blackbird nests in a Florida study were found in Eastern baccharis. Swamp sparrows have also been associated with habitats that have a notable presence of Eastern baccharis.

Eastern baccharis grows well in moist soils with high sunlight and is beneficial for preventing soil erosion along riparian zones but can become weedy in upland areas. It is salt tolerant and common along the Texas Gulf Coast where thick stands have been found to reduce forb diversity.

Fortunately, seeds of Eastern baccharis are only viable for about the first 18 months post-seeding and plants typically begin seeding around three years of age. Thus, early and persistent management can help keep Eastern baccharis in check.

The increasing abundance of Eastern baccharis has not only become a heightened management concern in eastern Texas, but has come to invade land along ports in France, Spain, and Australia where aggressive abatement programs have been adopted over the past two decades. Attempts to manage Eastern baccharis have varied widely with equivocal results.

One of the most comprehensive studies on the effects of prescribed fire on Eastern baccharis occurred across the complex of National Wildlife Refuges on the Texas Gulf Coast. The study found that fire had widely varying effects on Eastern baccharis.

In some burn plots, researchers obtained nearly 100 percent kill whereas other plots had very little kill and >90% survived.

Digging slightly deeper, the authors determined that fire conducted during the growing season tended to result in higher mortality rates compared with cooler fires. These results may explain some of the discrepancies by other authors who found fire to be ineffective at controlling Eastern baccharis.

Mowing has also been promoted as a management method but kill rates tend to be low and require repeated application. One study in Arkansas found about 60 percent of Eastern baccharis plants survived dormant-season mowing applied in two consecutive years.

If growing season fire isn’t an option for a land manager, perhaps due to unfavorable burning conditions or efforts to avoid disturbing ground nesting birds, a common practice adopted in the southeastern U.S. is post-burn mowing following late dormant season (e.g., March) fire. The collective application of dormant season fire followed by mowing after plants have begun to reinvest root reserves in the plant may increase effectiveness of either application in isolation.

Most basic shredders, however, are not built for shrubs and heavy cutting. Brown tree cutters, a heavy-duty variant of a shredder, is the tool of choice. Foliar application of triclopyr (e.g., Garlon® XRT) applied from June to September is a chemical alternative.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 25 PLANT PROFILE

RENEW TODAY to receive your NEW Membership Decal! Texas Wildlife Association 6644 FM 1102 New Braunfels, TX 78132 www.texas-wildlife.org (210) 826-2904 • FAX (210) 826-4933 (800) 839-9453 (TEX-WILD)

Leaves of Eastern baccharis. While the plant has some value in preventing soil erosion, the browse palatability for wild ungulates is poor and potentially toxic to livestock.

TAMU

Leopold

Article by SHELBY MCCAY Photos courtesy of the TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE

Lights, camera, action! In the newest episode of Leopold Live! with our partners at the Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve, the NRI crew chatted with ranch manager, Steven Fulton, and retired TPWD biologist, Mike Krueger, about deer harvest recordkeeping methods.

‘Tis the season to get to know how you can use these techniques for the benefit of your deer herd and how you can use your data to qualify for the wildlife tax valuation program

Fulton and Krueger opened the episode by discussing some of the reasons to collect harvest data. When managing a deer herd, you want to collect different kinds of data, such as census and habitat condition, to get a snapshot of the herd and habitat health.

DECEMBER 2022 26 TEXAS WILDLIFE Natural Resources

texas a&m university

Institute

NEWS

Live Deer Harvest Recordkeeping

here in Texas. (You can view the session at www.youtube.com/ watch?v=I7GOgCbX6HU&list=PL-fHLDjeQUqbzkC6GF4YKqdy jGopxhFnb&index=19&t=2s)

Age is one of the most important pieces of data you can collect from deer. Age can be estimated pre-harvest based on body characteristics and photos or post-harvest based on tooth replacement and wear.

Harvest record data lets you know if your management practices are making an impact on the quality of your deer and how to adjust your management plan accordingly to reach your goals. These data are essential to any deer management program and will let you know if you are under-, over- or properly stocked on your property.

After harvesting a deer, which piece of information should you record first? Krueger recommended collecting the field dressed weight of the deer before it is skinned and processed. Field dressed weights are better than live weights for comparison purposes as this eliminates variable weight (full vs. empty stomachs) in the deer which can skew your results.

An individual deer’s weight can vary throughout the year depending on diet quality, age, and life cycle stage—prerut, in rut and post-rut for bucks. Fulton stressed that all weights should be taken with a digital scale to ensure your measurements are accurate.

They agreed that age is one of the most important pieces of data you can collect from deer. Age can be estimated preharvest based on body characteristics and photos or post-harvest based on tooth re placement and wear. Aging deer “on the hoof” takes some practice but is an impor tant skill for deer hunters and managers.

On the Bamberger Ranch, they use game cameras from August 1 to February 1 each year to age, identify, and track the growth of each buck. This photo history can be used in conjunction with tooth wear aging, allowing them to adjust estimates accordingly.

Next, we delved into aging deer based on tooth replacement and wear. This method is an inexact science, but for a field technique there is nothing better for aging deer quickly and easily. Fulton and Krueger walked through aging different age classes based on tooth wear patterns using example lower jaws collected from each. They also provided a few tips to ensure you age them as accurately as possible:

• Look at both sides of the lower jaw because they do not always match. This can be due to broken teeth or missing teeth, abscesses, etc.

• Take your local soils into account. For example, Krueger mentioned you will see quicker tooth wear in areas with more sandy soils because deer ingest more grit where they eat closer to the ground

• Take their diet into account. For example, supplemental feed is softer than a typical diet and so their teeth wear down more slowly.

• Do not take antler size or body condition into account when

aging their teeth as this can skew your judgement

• If you are having trouble deciding between two ages, Fulton recommended erring on the conservative side and rounding down to the younger age class. We then demonstrated how to take antler measurements on bucks using a flexible nylon tape. Fulton takes some basic measurements for each buck (inside spread, beam length, basal circumference,

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 27 TAMU NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE NEWS

Why collect information on your deer? Because, as the old saying reminds, you can’t manage what you don’t measure.

and number of points), but for trophy deer he will take a Boone and Crockett score. For official scoring purposes, use either a stiff ruler or a metal measuring tape to get the most accurate results.

The last pieces of data Fulton and Krueger recommended collecting are lactation presence in does and body condition of all animals. Lactation presence at harvest means the doe has raised a fawn that year. You can compare this to your fawn crop data collected during census to see any potential correlation. You can assess body condition by looking at how much fat they have present on their organs and under the skin and is generally recorded as good, fair, or poor.

For those in the Managed Lands Deer Program, this basic data are required to be submitted to TPWD annually. Records should also include hunter name, date of kill, tag number, and sample number. Data collection needs to be consistent across years so you can see potential trends be

tween your management practices and the health of your herd. Krueger recommend ed limiting the number of people collect ing data on your property to ensure con sistency across animals and years.

So, you have collected all this data, what do you do with it? Fulton and Krueger recommended putting it in an Excel file so you can analyze it and look for potential correlations. Comparisons should be made only within an age class, not between age classes. They also advised not making management decisions or changes based on any one year of data. Decisions should be made based on trends observed over time on your ranch.

We rounded the episode out with a short Q&A session:

What are some telltale signs you are overharvesting or underharvesting your deer herd?

For overharvesting, Fulton said you will see a low number of deer on your census counts and a large percentage of your

harvest can be composed of 1 ½-year-old bucks. For underharvesting, you can see a browse line on your property, harvest more older individuals, and the majority are in poor body condition and have low weights.

Do I need to submit all my harvest records to the county tax appraiser for the wildlife valuation program?

While it is not required to submit all harvest record data, Fulton said in his opinion more is better when submitting data to the county tax appraiser.

Are there any additional data I should collect for my own records?

Photographs are nice and a detailed photo history of a buck can be very useful when it comes to aging them, Krueger said. This includes post-harvest photos.

The NRI crew can’t wait to share the next episode of Leopold Live! Be sure to keep an eye on Facebook for all upcoming episodes.

DECEMBER 2022 28 TEXAS WILDLIFE TAMU NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE NEWS

Specializing in: Farms, Ranches and Hunting Properties Throughout TEXAS! THE LAND creates a LIFESTYLE which leaves a LEGACY. j Call Me Today i Johnny Baker Realtor Associate www.txland.com johntxland@gmail.com 713-829-9951

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 29 LIVING WATERS RANCH 705 + Ac. Uvalde County SALARITA RANCH 9,382 + Ac. Maverick County OZONA-SONORA RANCH 947 + Ac. Crockett County DullnigRanches.com DullnigRanches@gmail.com 210.213.9700 CONSIDER LEAVING A BEQUEST TO TWAF IN YOUR WILL Contact TJ Goodpasture for information | (800) 839-9453 HELP PROTECT AND PRESERVE FUTURE OUTDOOR EDUCATION.

The Trans-Pecos is a tough place to live, no matter how many legs you have. With management, however, the area can produce trophy mule deer bucks.

DECEMBER 2022 30 TEXAS WILDLIFE A MULE DEER QUESTION

A MULE DEER QUESTION

WEISHUHN

WEISHUHN

“T

hey’re here, but I’m not sure where,” commented the lower Panhandle rancher. “Our cowboys see them on occasion when we’re gathering cattle, but never many. I well remember a time when there were no deer in this area.”

He continued, “They may have been here in abundance when Quanah Parker and his warriors roamed through here, but by the time I came along in the 1950s it was extremely rare to even

hear of someone seeing a mule deer. If they did, it was popular coffee shop and campfire fodder for months!”

It was 1975. I was a young wildlife biologist anxious to learn what I could about the mule deer population in the sand and shin oak habitat along the Texas and New Mexico border. At the time, I was mapping what remained of Lesser Prairie Chicken habitat. I also took the opportunity to visit with area ranchers and farmers about mule deer.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 31

Article and photos by LARRY

My interest in mule deer found along the sandy border be tween Texas and New Mexico was piqued two days earlier when I was flying over Andrews County to get an aerial perspective of the remaining Lesser Prairie Chicken habitat. The pilot and I spotted a bachelor herd of five mule deer bucks.

These bucks were not “just bucks.” Their antlers were big or bigger than any mule deer I had seen taken in Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado. Each buck had massive, long-tined, and extremely wide racks. Thus, I knew there were at least five mule deer in Andrews County.

Fast forward into the early 21st Century. The mule deer populations in the lower western Panhandle had increased to sustainable, huntable numbers. Hunters had started taking some extremely large antlered bucks in areas where there had been very few deer previously.

In the Trans-Pecos, more and more land managers and hunters were beginning to seriously take care of mule deer. Mule deer populations across their Texas range had thankfully

started increasing. Why? Habitat changes toward a mixture of row crops, as opposed to purely sand and shin oak, played a role in the Panhandle. But also ranchers, farmers and hunters started becoming genuinely interested in mule deer.

Landowners/managers began to view mule deer as an economic crop. They became aware of mule deer’s habitat requirements including having access to reliable water sources every day instead of relying solely on small and scattered natural waterholes which held water only for a short period of time after rain or snow fall.

Leasing land for whitetail deer hunting had become popular farther south and east, which set the stage for the same thing with mule deer. Deer now had an economic value thanks to deer hunters willing to pay for quality hunting. It is truly amazing how attitudes and land practices change when wildlife becomes more valuable to visiting hunters, as opposed to family and ranch personnel simply shooting to get rid of them because they might (heavy on the “might”) compete with livestock.

DECEMBER 2022 32 TEXAS WILDLIFE A MULE DEER QUESTION

This mule deer buck and his two ladies are proof positive that the Trans-Pecos can produce trophy animals.

The same was happening in the TransPecos, far better known for desert mule deer than the Panhandle. Hunting for mule deer west of the Pecos River, often referred to as “blacktail deer” back then, had long been somewhat popular among locals and a few visiting hunters.

Interest dramatically increased in Trans-Pecos mule deer when outdoor writers of the era like Byron Dalrymple, Russell Tinsley, and others started writ ing about the extremely fine and funfilled mule deer hunting to be found in far western Texas. As a youngster I could scarcely wait to read about Dalrymple’s annual mule deer hunt on the Catto-Gage Ranch’s famed “Hell’s Half Acre” pasture.

Lease prices started increasing. Because of the economics of leasing their land to deer hunters, landowners made certain there was water even in pastures where cattle had been vacated and grazing prac tices were changed. Ranchers and manag ers soon started asking for technical as sistance from TPWD wildlife biologists with a goal of increasing both herd num bers and the quality of animals within those herds.

This began taking place when the government’s Wool and Mohair Incentive Program started closing down in the 1990s. Up to that point, ranchers received government incentive dollars to produce mutton, wool and mohair. To protect their sheep and goats, landowners carried on stringent predator control practices.

For many years, sheep and goats were “king” in western Texas and landowners essentially removed predation from the wildlife management equation. As the Trans-Pecos changed from raising sheep and goats and moved toward cattle, pred ators were allowed to increase. I remem ber during the sheep and goat days doing spotlight game surveys and seeing many mule deer and no predators on our vari ous nighttime census lines.

As predator control waned, mule deer populations started changing. Soon it was common to see only a few deer and numerous predators during the surveys. Without predator control it did not take long until we were seeing more predators than deer on the night-time surveys.

Predators included coyotes, bobcats, and cougar. The negative side of sheep and goat ranching was range degradation. The positive side was no or very few pred ators to take fawns and grown deer.

Starting in about the 1960s we began learning much about managing whitetailed deer and their habitat for quality, meaning healthier individuals that developed bigger bodies and bucks that grew bigger racks. This was accomplished by increasing the quality and quantity of deer forage and browse that was available.

Healthier adults on a higher nutritional plane also resulted in higher reproduction and fawn survival rates. Producing more deer meant harvesting a considerable number of does each year to keep the pop ulation in check and in balance with what the habitat could support in drought years.

With whitetails, it is not uncommon for 80 percent or more of doe fawns to experience their first estrus and conceive at six months of age. Whitetail deer tend to mature early, especially doe fawns.

At the time it was accepted that mule deer were essentially the same deer as whitetails. So, for a short time it was believed one of the keys to producing a quality mule deer herd should require

removing a considerable number of does each fall.

In theory, this sounded good. As with whitetails, shooting mule deer does should increase fawn survival rates because the remaining does would have superior nu trition, thus recruiting more bucks into the herd.

We soon learned that mule deer does are not exactly like whitetail does. Mule deer does tend to sexually mature considerably slower that whitetails. A fair number of mule deer does do not breed until they are 2 ½ years old. A very small percentage of 1 ½-year old mule does may get bred.

And while I am not going to say, “no mule deer does breed at 6 months of age,” I have never known it to happen. In a relatively short period of time we, as wildlife biologists and deer managers, learned a very valuable lesson; if you shoot mule deer does at rates as we do whitetails does you can soon be out of mule deer.

If we want good mule deer herds we need fawn recruitment, and beyond providing quality forage and browse on a daily basis, we need to make certain mule deer have access to water, something that bears mentioning several times. We need

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 33 A MULE DEER QUESTION

Hargrove Ranch’s David Archer and Larry Weishuhn glass a distant mule deer. In wide-open country like the Trans-Pecos, binoculars and spotting scopes are essential equipment.

to also limit buck harvests so bucks can mature to at least 5 years old before putting hunting pressure on them.

And as previously stated, we cannot manage mule deer the same way we do whitetails when it comes to harvesting does. Frankly, on the “research ranches” where we shot a lot of does, we nearly destroyed the mule deer population before we realized shooting great numbers of mule deer does truly has a devastating effect because of their slowed reproduction and recruitment rates.

Thankfully, we only tried to manage mule deer in terms of whitetail doe harvests on a couple of ranches. By backing off on harvesting does we were able to bring back those local mule deer herds.

Today, thanks to the lessons learned years ago, progressive landowners and managers and an all-time high interest in mule deer, the mule-eared deer in Texas are on the upswing. Deer quality, in terms of antlers taken in Texas, is as good or better than some of our more traditional mule deer states.

To further encourage managing for quality, TPWD recently instituted antler restriction regulations in seven counties in the Panhandle, requiring an outside main beam spread of at least 20 inches to be legal. This undoubtedly will allow an increased number of younger-aged bucks to live longer, thus resulting in increased body weight and antler size.

Many ranches in Texas’ mule deer country these days have ex cellent livestock grazing programs, plant supplement food plots, even provide pelleted rations or cottonseed to provide improved nutrition on a daily basis.

I am extremely fortunate to hunt mule deer on the Hargrove Ranch in the lower Texas Panhandle. The ranch is under a wellregulated livestock grazing program, ensuring there is vegeta tion and native browse for deer even during the throes of a se vere drought. Craig and David Archer, the ranch’s managers, make certain there is always water available to mule deer even when cattle have been rotated out of a pasture.

They also do brush control, more properly described as brush manipulation, removing dense stands of juniper in strategic ar eas which can and will be replaced by better deer browse species. In truly hard times they also do some supplemental feeding.

The Hargrove Ranch, like numerous others interested in mule deer, have an on-going predator control program. They, too, limit the harvest of bucks based on annual censuses required as part of Managed Land Deer Permit program for mule deer. Their results have been excellent. Money derived from the ranch’s hunting program is designated for their wildlife management program, which includes increasing the local mule deer population.

DECEMBER 2022 34 TEXAS WILDLIFE A MULE DEER QUESTION

The author with the results of several years of carrying on an excellent management program on the Hargrove Ranch in the lower Texas Panhandle.

As a serious mule deer hunter, one of the things I dearly love is calling them using a Burnham Brothers S2 Close Range Preda tor Call. I have also used with great suc cess a Burnham Brothers C3 Long Range Call Predator Call. Does and bucks of all ages generally respond by charging in at a full run.

Although sometimes, older bucks cautiously slip in, as one would expect an old whitetail buck to do when responding to rattling horns. During my last three hunts on the Hargrove, I have called in more than 200 mule deer.

Over the years I have called in mule deer throughout much of their range from the Rocky Mountains to the broad and brushy plains of Sonora, Mexico. I dearly love hunting mule deer, which I consider the finest game animal in North America, regardless of the location, habitat, and terrain, but especially in Texas.

Greg Simons, former TWA president and mule deer hunter/manager fanatic, has produced and taken some extremely large antlered bucks on ranches he’s managed for quality in Trans-Pecos through Wildlife Systems as well as on his personal lease. His personal best includes the largest antlered, (classified as a non-typical), desert mule deer in history according to the Boone and Crockett Club. The buck he calls “Hank” had a gross score around 300 B&C points. After going to a panel scoring, “Hank” netted 287 7/8.

In visiting with Greg about his man agement programs, he stresses the impor tance of water. Greg strives to make cer tain mule deer never have to travel far to have access to water. He, like several other ranchers and wildlife managers, also pro vide supplemental feed to ensure the local deer have no reason to go hungry a single day throughout their life. The results have been astounding.

To me the most impressive game animal in all North America is a large antlered mule deer buck with tall and split back tines, equally long front tines, and a spread that approaches 30 or more inches. When such antlered bucks stand on a ridge and turn their head, it is the world beneath him that moves, not the buck.

Antlers are a reflection of a deer’s health and the health of the habitat in which it lives. If mule deer bucks, no different than whitetail bucks or bull elk, have big antlers relative to their age it is a sure sign the habitat is in ex cellent shape. Big antlers on healthy deer, too, is a sign all other wildlife species which live in that habitat are doing well, and maybe more importantly the habitat is doing well.

I mentioned earlier there are similari ties between mule deer and their whitetail cousins when it comes to food, water, cov er, and habitat requirements. Interesting ly, for years we thought mule deer were generally less tolerant of humans and human habitation. To some extent that may be true with the northern version of the mule-eared deer, the Rocky Moun tain subspecies, as opposed to the desert subspecies we have in Texas, Odocoileus heminous crooki

The Rocky Mountain variety tends to be migratory because of the terrain they live in. Snow and ice force mule deer out

of the high country during winter. They have to move to where there is available food. Then they return to the higher country when spring arrives.

Our Texas mule deer may move up and down a slope, but with our weather there is no reason for them to migrate any distance as their northern kin do.

Our Texas mule deer do face some future obstacles. The biggest current potential problem for our mule deer is the threat of chronic wasting disease (CWD). What CWD will or will not do to mule deer in the future only time will tell. However, we as landowners, managers, wildlife biologists and hunters need to do whatever we can within reason to stop and limit the spread of this disease.

Beyond CWD, Texas mule deer have a relatively bright future as more and more landowners and managers adapt good sound management practices built around and for mule deer. Long may they stot across our Trans-Pecos and Panhandle!

SALES | AUCTIONS | FINANCE | APPRAISALS | MANAGEMENT

CODORNIZ RANCH

$11,190,000 | Aspermont, TX

This premier conservation sporting ranch in central Stonewall County is in the heart of the rare Nobscot “quail sands” soil series. The 4,069± acres are teeming with whitetail deer, turkey, and feral hogs, and an immaculate move-in ready lodge.

R & R RANCH

$3,950,000 | Brownwood, TX

Adjacent to Lake Brownwood, 391.29± acres with a custom home, barndominium for guests, and a 26-acre privately owned lake. A private escape with first-class opportunities for fishing, waterfowl, and hunting with close proximity to Brownwood.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 35 A MULE DEER QUESTION

WWW.HALLANDHALL.COM

VIEW MORE LISTINGS ONLINE AT

DECEMBER 2022 36 TEXAS WILDLIFE STALKING PALO DURO

The author snapped this photo of his December 2021 Texas mule deer just before getting his shot. The big 10-point trailed a hot doe past him for a 15-yard archery shot.

STALKING PALO DURO

by BRANDON RAY

South of Amarillo, where the drea ry plains abruptly drop into a gi ant hole, the change in scenery is as subtle as a car crash. Welcome to the Palo Duro Canyon. Colorful orange and red cliffs are dotted with twisted cedars and spiny yuccas. It’s my favorite place on planet Earth.

Sitting on the canyon rim, far from pavement and city lights, I feel wild and free. From the canyon rim, armed with a spotting scope on a tripod and 10X binoculars, I can search for aoudad sheep, white-tailed deer, Rio Grande Turkeys, wild hogs, and mule deer. Mule deer are my focus on this October day in 2021. I’ve just spotted two.

The two bucks are bedded in broken terrain near the rim. Dotted with short cedars and open ground, the two bucks’ antenna-like racks are easy to spot in the yellow grass. Easy to spot, but they would be difficult to stalk. Each is facing a slightly different direction. They are bedded where an approach from behind would blow the stalker’s scent to the bucks. Smart deer.

Both are respectable, middle-aged bucks, but I’m being picky. One is wide with pencil-thin beams and short forks. The other is narrow and tall with better mass, extra points on his back forks, but no front forks. Put the two together and it would make the buck I’m looking for. Good prospects for next year, I mutter to the wind. Nothing is easy about finding an old, big-racked mule deer. Tagging one with a bow is even harder.

BUCKS BY THE BOOK

How rare is a record-class archery mule deer buck on Texas soil? According to data from archery’s prestigious record book, The Pope & Young Club, Texas has 38 typicals, one velvet typical and six non-typical mule deer entered from the Lone Star State. That’s 45 bucks total. Minimum score for a typical is 145 inch es. The minimum score for a non-typical is 170 inches.

To put those numbers in perspective, consider how many Texas whitetails are entered in Pope & Young. According to the Club’s Trophy Search, there are 2,033 typicals, five velvet typicals, 129 non-typicals and one non-typical in vel vet. That’s a total of 2,168 entries. Mini mum score for a typical whitetail is 125 inches and the non-typical minimum is 155 inches.

Several factors contribute to the big difference in those numbers. First, whitetails are far more plentiful in Texas. Recent estimates put the statewide population at 4 million. In the best years, Texas has an estimated 250,000 mule deer. Second, whitetails are easier for most hunters to access because they can be found closer to big cities. Mule deer live primarily in the Panhandle and Trans-Pecos regions, farther from most urban areas.

Whitetails can be successfully hunted over feeders where shots are often under 20 yards. Mule deer are usually hunted by spot and stalk where shots of 40 yards-plus are common. Hunting mule deer is more

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 37

Article and photos

Bowhunting mule deer in the Texas Panhandle is not easy, but when a big buck finally wears your tag, the effort is worth it.

physically demanding with hiking and traversing rugged terrain to be expected.

Mule deer are more visible than whitetails in open country, especially around ag fields like wheat or milo, making them more susceptible to over harvest. This makes managing for prime antler years of 5-7 more difficult. Combine these factors and the rarity of taking a big mule deer with a bow becomes understandable.

TEXAS MULE DEER

The number of mule deer in Texas fluctuates year to year based on drought, blizzards, rainfall, predation, and disease.

The statewide population ranges from about 150,000 during dry conditions to about 250,000 during wetter periods. According to survey data by TPWD, the statewide population in 2019 was 227,392.

I asked Todd Montandon, TPWD wildlife biologist in Canyon, Texas, for his thoughts on mule deer in the counties around the scenic Palo Duro Canyon and what plant species are important there.

“Mule deer densities average around 120 acres per deer in the canyon within Armstrong, Randall and Briscoe counties with some areas higher and some lower depending on habitat quality. The population is stable overall, and we have

had average to above average fawn crops the last few years,” he said.

“Important plants include browse species like netleaf hackberry, little leaf sumac, aromatic sumac, sandplum, plains greasebush, and mountain mahogany and many different forbs.”

BOWHUNTING MULE DEER 101

Some basic rules apply to stalking mule deer. Stalking a single buck is always easier than stalking multiple animals. Too many eyeballs, ears and noses does not usually end with a filled out tag.

Look closely around your target buck to check for other animals that might blow

DECEMBER 2022 38 TEXAS WILDLIFE STALKING PALO DURO

Among the joys of hunting is being able to see some fantastic views like this along the rim of the Palo Duro Canyon.

The author captured this wide 10-point buck at sunset with a camera. The next year, during a blizzard, the buck was harvested.

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 39 STALKING PALO DURO

your stalk. Once you start your approach, pay close attention to wind direction. I carry a small puff bottle in my pocket. Puff it often to track wind currents or toss a tuft of grass. Stalk with the wind in your face or into a crosswind.

Next, wind speed is important. I won’t even attempt a stalk on a dead calm day. Those big, radar-like ears will pick up the slightest crunch of dead grass underfoot and be gone.

Windy days are better for stalking. However, “windy” is a tricky term. Too much wind and making a well-aimed bow shot at 40-plus yards will be difficult. Wind speeds of 15-20 mph are ideal in my experience.

Keep brush between you and the buck as you get closer. Remove your boots and stalk in quiet wool socks or don fuzzy stalking slippers or moccasins to silence your stalk for the final 200 yards. Belly crawl, pushing your bow ahead of you, to maintain a low profile.

A mistake many rookies make is trying to get too close. Instead of trying to stalk inside 25 yards, stop the stalk around

the 50-yard mark. Too much can go wrong inside 50 yards. Wait at the outer edge of your comfortable shooting range. Use a rangefinder to determine distances to landmarks and wait. I’ve waited all day for a buck to stand. Water and snacks in my fanny pack keep me comfortable while I wait.

Let the buck stand on his own. Throwing rocks or whistling to get him to stand is usually a mistake. Oftentimes, if a buck stands on his own, he will stretch, survey his surroundings, nibble some brush, then walk a short distance.

Don’t rush things. Wait until his eyes are behind brush or in the grass. He may even close the gap for a closer shot. If you toss a rock, you usually get a shot at a very alert animal or he just blows out of his bed, pogo-sticking to the horizon in a trail of dust.

It’s important to keep a low profile on a stalk. Practice shooting from your knees. Standing on level ground with feet shoulder width apart, good form on the practice line, is rarely possible in rocky, uneven terrain.

A young mule deer buck stops for a look back.

DECEMBER 2022 40 TEXAS WILDLIFE STALKING PALO DURO

Wait for a broadside or slight quartering away angle. After the shot, whether it’s a hit or a miss, reload a second arrow. Finally, make note of landmarks after the buck is hit. I usually tie an orange surveyor’s tape to a bush to mark the exact location where I took my shot before I start tracking. That way, I can go back to that exact location if needed.

Stalking is not the only way to bag a buck. Throughout most of Texas’ mule deer range, drought is a common occur rence. Therefore, guarding water at a re mote windmill or pond is very effective.

In my experience, most deer visit the windmills late in the afternoon or after dark. The last hour before dark is usually prime time. However, some bucks will water in the mornings or at midday. A trail camera set near the water’s edge can tell you when it’s worth it to sit in a blind.

A third tactic, and one I’ve used in recent years, is hunting bucks over bait stations. I utilize troughs filled with corn and alfalfa hay to feed bucks and does through the fall and winter. Mule deer seem to prefer the open troughs versus a timed feeder.

A pop-up blind set nearby makes a sneaky ambush. The big-eared deer pay little attention to the blind after it’s been there a while. I hunt such spots very little, maybe a couple of times per season, and only when the wind direction is right.

RECENT HUNTS

I shot my first mule deer in 1987 on the rim of the Palo Duro Canyon. On that hunt I used my dad’s old Sako .30-06 rifle.

My first archery mule deer came in October 1995. I shot that velvet-clad, basket-racked 10-point spot and stalk. Even though my taxidermist lost that set of fuzzy antlers, I’ve been hooked on bowhunting mule deer ever since.

I’ve hunted them in Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, New Mexico, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Alberta, Canada. But there’s no place I’d rather chase them than my grandfather’s ranch in Texas.

In late October 2020, a freak blizzard hit the Texas Panhandle. Temperatures dropped like a stone. A fine 10-point I’d monitored for a couple of years was mak

ing sporadic visits to a feed station. I hoped the frigid weather would draw him out to feed before dark. Dressed in ther mals top and bottom, two wool hats, two fleece neck gaiters and fleece gloves, I was still cold.

The 5 ½-year-old buck came from the south late in the afternoon following three does and a small buck. I was so cold my breath looked like smoke. The air temperature was 26 F, but the wind chill was 16.

The deer paid no attention to my blind. From a scant 10 yards away, my arrow found the buck’s ribs and I followed a blood trail across the crusty snow to that fine muley. He weighed 250 pounds live weight. His rack was 24 inches wide and gross-scored 155-inches.

Big bucks were hard to find in 2021. In fact, it was early December, the rut starting to gain momentum, before I found a big one. I saw the heavyhorned 10-point following a doe late on December 3. Daylight was gone, but I vowed to return the next day.

I found that same buck, likely follow ing the same doe, at noon on December 4. They appeared to be headed to a near by windmill with several other deer. It seemed imminent that their line of travel would end at the water’s edge.

I made a quick stalk, jogging more than sneaking to try to close the gap, dodging from cedar to cedar, checking the wind often. Finally, I kneeled behind a bushy cedar tree near a well-traveled trail, nocked an arrow and waited.

Ten minutes later, at 12:25 PM, the doe walked down the trail with the big 10-point behind her. At 15 yards, I dropped the string. The buck trotted 55 yards and tipped over.

That buck was missing half of his right ear, leaving little doubt about who he was. He grew from an average 8-point to a 160-class stud in just one year. With a scenic view of the canyon rim nearby, I used orange baling twine to tie my tag to his thick antler base. Another great memory from my favorite place on Earth.

Long Term Hunters Wanted!

WWW.TEXAS-WILDLIFE.ORG 41 STALKING PALO DURO

–

•

–

• Rancho Rio Grande - Del Rio, TX MLD 3, $15/ac, Hwy 277 Frontage, water & electric – 1,850 ac, white tail, some exotics & birds

6,000 ac, Axis, Duck & Quail Live Water: Rio Grande River, Tesquesquite Creek and a canal.

Harwood - Brackettville, TX MLD 3, North of Hwy 90, main camp area

9,170 ac , Whitetail, Some Exotics

There’s nothing like a sunset in ranch country to calm the soul. That, along with many other things, is what attracts people to TRS Ranch Retreats.

TRS RANCH RETREATS

A New Age of Ranching

Article by LORIE A. WOODWARD Photos courtesy of TRS RANCH RETREATS

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth in a series of articles exploring alternative income and educational opportunities for TWA members.

With the launch of TRS Ranch Retreats in 2020, the historic La Martineña Ranch, nestled in the Brush Country near Encinal, has entered a new age.

“The ranch offers an escape from the noise and pressures of modern life—and people respond to being out here,” said Tami Summers, who founded the retreat with her husband Robert, who represents the fifth generation of his family to own and operate the 150-year-old ranch. “The combination of nature and yoga unleashes a calming, centering, healing power where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”