The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Justine Olsen

Introduction

In 1965, a twenty-four-year-old Bachelor of Arts student named Walter Cook bought an Art Nouveau tea set at the Willis Street, Wellington, secondhand shop Odds & Ends. In the context of mid1960s design, with its flat patterns and use of stainless steel, the Liberty & Co pewter tea set would have seemed totally old-fashioned to most, but Cook saw it for its style.

This purchase marked the beginning of twenty-five years of collecting decorative art made in Britain, Europe and Scandinavia, as well as a small number of objects made in New Zealand, through which Cook intended to chart the century-long design pathway towards modernism.

The collection was strategically acquired and directed by solid research, its collector driven, determined and often selfsacrificing. An autodidact, from the early 1960s Cook’s reading of architectural and design histories and design journals shaped a growing knowledge of design reform and gave his collection a cultural context. The vases, tea sets, bowls, plates, wallpapers and tiles he gathered were not just well-designed and well-made objects, they were also exemplars of one hundred years of design reform. As Cook told RNZ’s Paul Diamond in a lengthy interview in 2012, they were evidence of the ‘strong urge in the nineteenth century to find a style of the times and to link it to the belief that the health of the individual and of society was bound up in a well-designed environment fitted out with well-designed things, and that fed into international modernism’.1

Cook sought out objects by key design leaders and exponents: Morris & Co, William De Morgan, Christopher Dresser, Liberty & Co, Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik (WMF), Mintons, Truda Carter for Poole, Susie Cooper, Keith Murray, Torben Ørskov, Royal Copenhagen and Rörstrand all featured. He found objects by smaller and lesser-known manufacturers including the art potteries Ashby Guild, Ruskin Pottery and Aller Vale. And he picked up modernist Scandinavian design objects, including by the Swedish company Nittsjö Keramik. From the Arts and Crafts Movement through to modernism, many pieces were by women designers and makers, including Hannah Barlow, who was at Doulton in the 1870s, and Berte Jessen, who was at Royal Copenhagen in the 1960s. Cook’s collection also revealed the adaptability of many British manufacturers, the outstanding example being Doulton, which kept abreast of stylistic changes from the time of its collaboration with the Lambeth Art Studio in the late nineteenth century to its everyday

Art Deco range made during the Great Depression of the 1930s. He touched also on New Zealand exponents in order to illustrate the postwar period during which the country’s ceramics industry had expanded as the result of import substitution legislation. Remarkably, he funded the collection from a range of modestly paid jobs, and later with the assistance of his then wife, Adriann Smith.

By 1985 Walter Cook’s collection of nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts, Aestheticism, Art Nouveau, Art Deco and twentiethcentury modernism, which included ceramics, decorative tiles, metalwork, wallpaper, glass, wrapping papers and carpets, ran to around 385 objects.2 He displayed and stored them in the Thorndon home he shared with Smith and their children, Ruth and Madeline. The collection not only reflected the presence of international decorative art in New Zealand, but also revealed the cultural links to Britain, Europe and Scandinavia that had been present in the New Zealand retail market for over a century. As Cook explained around 1995, his intention was for the collection to be ‘an anthology of changes in taste and style in the applied arts – a record of the constantly shifting idea of the “modern” and a way of entering into the meanings of what this implied at different times’.3

Walter Cook at his desk in his flat in Wellington, around 1965. Walter Cook private collection.

A sense of design

alter Cameron Cook was born on 7 September 1941 in Wellington. His father, George Pilkington Cook (1893–1973), was the curate of the Anglican parish church and pro-cathedral of St Paul’s in Thorndon. Walter was born at 11am as the bells rang to announce his father’s morning communion service.1

Cook was the eldest of three children from George’s second marriage, to Hinehauone Coralie Cameron (1904–1993). George and Coralie were a cultured couple. George’s interests lay in British theological history, including the ideas of the reformist clerics John Henry Newman and Charles Gore. Coralie was a talented artist and printmaker.

Soon after he was born the family moved to Pongaroa, a rural town deep in the Tararua District north-east of Masterton, where George was to be vicar of the Church of England parish of St John the Baptist. Placements in parishes were typically transitory and at the behest of the bishop of Wellington, and a year later the Cook family moved again, to Pātea, then Bulls and finally to Greytown, where they lived from 1951 to 1960.

as Vorticism.10 Both styles had an influence on her future work.11 On her return to the family farm in 1930 she continued to make wood engravings, linocuts and etchings that reflected her rural experiences. Between 1932 and 1938 Coralie Cameron exhibited her prints at the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, the Auckland Society of Arts, the Otago Art Society and the New Zealand Society of Artists.12 Her visits to Sāmoa in 1934 and Tahiti in 1936 as the companion of a friend who was the wife of a circuit judge were the inspiration for a series of prints that depicted local people.13

In 1940, after a period in which she picked fruit in Motueka, Coralie Cameron moved to Ōtaki, north of Wellington, where she established a cut-flower business and met George Cook, who by then was a widower and the father of six children. They married later that year. Two of the sons of his first marriage, Nigel and Rodney, were still at home, and George and Coralie had three more children of their own: Walter, Jane and Susan.

Busy with the responsibilities of both parenting and being a vicar’s wife, Coralie abandoned her artistic ambitions until the children were older. In the 1960s she took lessons from artists including Toss Woollaston and John Drawbridge.14 Encouraged by former gallery owner Helen Hitchings, she also made prints from her 1930s woodblocks. Her modernist rural scenes lined the walls of every vicarage in which the family lived.15

In 1946, when Walter Cook was four years old, his mother took him to the Wanganui Museum. Cook remembers ‘a cabinet of curiosities’ and ‘a Chinese junk elaborately carved in ivory, a machine that told your weight and fortune, stuffed animals and birds, cabinets of coloured butterflies and beetles all labelled, and Māori artefacts’.16 It was, he said later, a life-changing experience: ‘I returned home and started my own museum, and from then on, museums became places of pilgrimage – sites of an ultimate reality to which I could only aspire.’17

His little museum contained shells, fossils, rocks, insects, his grandmother’s Chinese embroidery, Māori artefacts, Samoan tapa cloth – many items were gifted by his family or found locally. Reflecting on this collection in 1994, he observed that the impulse to collect and display was in ‘imitation of the way museums isolate, make significant and transform objects, which is one of their magical properties’.18 His collection grew and he enjoyed showing it to others, but when he turned sixteen he decided to give it away to friends, family and ‘deserving recipients’.19

Hinehauone Coralie Cameron’s wood engraving Apple grading, 1938. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (1992-0037-5).

Blending bold shapes and rich experimental glazes, ceramics by Ashby Potters’ Guild were often inspired by Oriental examples. This group, bought from the Wellington secondhand shops of Beverly Reid and Neale Auld; David Owens and Linley Halliday; Willbank Court Antiques; and Alma Foster, showcases Ashby’s distinctive experimental glazes. Founded by Pascoe Tunnicliffe in 1909, in Woodville, Derbyshire, Ashby featured in international exhibitions in the 1910s and early 1920s including the International Exhibition Brussels in 1910. Like many potteries, its production was suspended during the First World War, and by 1922 it had merged with Ault Faience Pottery to form Ault and Tunnicliffe.

Vases. Manufacturer: Ashby Potter’s Guild, England. From left: Vase, 1909–21. Blue glaze on white fired clay 240 x 180 x 180mm, CG001854; vase, c.1912. Aventurine glaze over grey fired clay, 90 x 195 x 195mm, CG001853; vase, 1909–12. Glazes over red-brown fired clay, 70 x 100 x100mm, CG001857; vase, c.1915. Purple glazes over grey fired clay, 225 x 185 x 185mm, CG001855; bowl, 1909–21. Green streaky glazes over brown fired clay, 85 x 115 x 115mm, CG001852.

Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Aestheti̇cism

reed of the moral and religious constraints of the Victorians, Aestheticism, or the cult of beauty, was a brief cultural moment at the end of the nineteenth century. A small but high-profile British elite of writers and artists pushed up against the stuffy social codes of Victorian England, shocking the prudish and hidebound with their bohemian attitudes to dress, morals, sexuality and class.

Its key – and sometimes controversial – advocates and exponents, who included writer Oscar Wilde, illustrator and publisher Aubrey Beardsley, artists James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, architect and art furniture designer Edward Godwin and designer Christopher Dresser, explored Aesthetics as an end in itself. Wilde explained their beliefs in 1890: ‘Beauty has as many meanings as man has moods. Beauty is the symbol of symbols. Beauty reveals everything, because it expresses nothing. When it shows itself, it shows us the whole fiery-coloured world.’1

Aestheticism overlapped with the Arts and Crafts Movement and drew from the latter’s ideas about handcraft, truth to materials and the importance of the domestic interior. Its often sensuous and eclectic approach had many inspirations: the Gothic Revival style, the designs of ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt, the blue and white ceramics of China and Japan and the woodblock prints and designs of Japan.

This Bretby vase with its twisted handles was bought from Neale Auld in 1981.

Vase, 1883–90. Manufacturer: Bretby Art Pottery, England. Earthenware, glazes, 265 x 115 x 115mm, CG001820.

102 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

This tall, three-handled Bretby vase was bought from Neale Auld in 1981.

Vase, c.1895. Manufacturer: Bretby Art Pottery, England. Earthenware, glazes, 445 x 210 x 210mm, CG001821.

Art Nouveau

s cultural and industrial changes swept through Europe from 1890, a search for a new design approach began.

New Art, or Art Nouveau, offered a radical style of design, art and architecture. In its rejection of historical European art, the style looked to the future and demonstrated regional variations from within Europe as well as the influence of Japan. Wild or tamed, Art Nouveau’s representations of nature through linear and rhythmical designs appeared in architecture, graphic design, decorative arts and fashion.

Art Nouveau was born in the urban centres of Paris, Brussels and Vienna. The idea of the unified interior informed the ‘house of Art Nouveau’, exhibited by art dealer and Art Nouveau enthusiast Siegfried Bing at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. A review in The Studio later that year described its dressing room, designed by painter, theatrical and industrial designer Georges de Feure, as ‘an atmosphere of enchantment. Everything is delicately feminine – the curtains of Japanese silk, the woodwork of ash, intermingled with a figured silk of grey-blue, grey-mauve and greygreen, revealing the subtlest of tones, and showing like a field of flowers under the moonlight’.1

In their search for modernity, architects, designers and manufacturers began to experiment with new materials and techniques. Makers such as Gallé, Daum, Loetz and Wilhelm Kralik Sohn worked with glass, lauded for its organic forms and iridescent colours, and the German metalwork company WMF embossed patterns in relief on cylindrical and convex forms using a huge hydraulic press.2 In Paris, the Eiffel Tower was constructed in iron, and Hector Guimard’s sinuous designs for the now famous entrance signs to the new Métro system, commissioned for the 1900 exposition in Paris, towered over passengers.

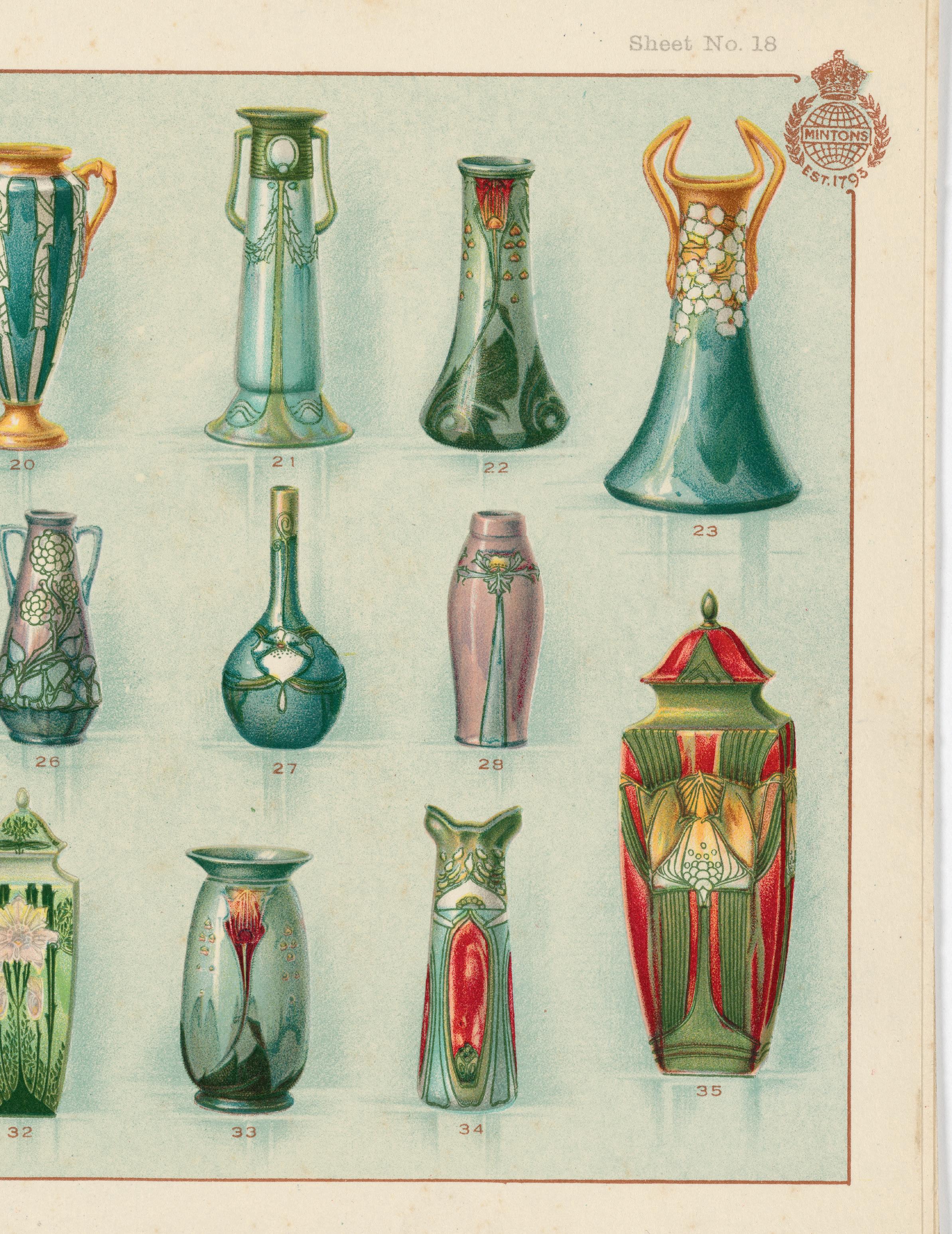

In Great Britain, Art Nouveau grew out of both the Arts and Crafts and the Aesthetic movements. Art Nouveau was expressed through a part craft and part manufactured approach, epitomised in the products of the London store Liberty & Co, which worked with artists and designers including Archibald Knox. Liberty’s fame was such that in Italy the style was known as ‘stile Liberty’. British ceramics manufacturers Mintons and Royal Doulton reinforced Art Nouveau with their climbing plant designs, and Pilkington, Bernard Moore and George Howson & Sons explored glaze technologies.

Regional variations were especially evident in Art Nouveau. In Scotland the ‘Glasgow Four’ – architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, his wife, artist and designer Margaret Mackintosh, her sister Frances Macdonald and Frances’ husband Herbert MacNair – devised

Above: The lavish Art Nouveau boudoir of art dealer Siegfried Bing, designed by Georges de Feure for the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. The room featured gilded wood furniture, silk embroidered seat covers and walls hung with silk brocades. Bing was one of the greatest exponents of Art Nouveau and his knowledge of Japanese art and design, and his publishing, exhibition-making and commissioning influenced private and public collectors and manufacturers such as Louis Tiffany. The Studio Ltd, London.

Opposite above: Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, photographed by James Craig Annan around 1901. Wikimedia Commons.

Opposite below: The mystical imagery of the Glasgow style is evident in this poster designed around 1895 by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Frances Macdonald and James Herbert McNair. Wikimedia Commons.

delicate linear interior schemes inspired by nature and Celtic Spiritualism. The climbing rose motif in particular characterised their designs. Their work was shown in Vienna in 1900, then in the Turin International Exhibition in 1902. In Turin, a series of rooms included the Rose Boudoir in ‘pearly lightness, pale rose, pink, green and blue’ and furnished with black and white furniture, panels of painted gesso, a silver repoussé panel and lit by silvered electric lamps.3

Art Nouveau contributed to what became known as the Vienna Secession and Secessionist style, which sought to create a broad transnational style that brought together art, architecture and the decorative arts in a unified and contemporary way. A populist version appeared in British ceramics by Royal Doulton and Mintons, among others.

The Art Nouveau period came to a close in 1914 at the beginning of the First World War, marking the end of a decorative style that had searched for progress and change.

Art Nouveau

This page: Like many Art Nouveau artists and manufacturers, WMF exploited the female form, and it’s designs often featured young women with fluid drapery, shifting the focus from the function of the work towards erotic and decorative appeal. This visiting card tray was bought from Odds & Ends on Willis Street, Wellington, in 1968 for $25.

Visiting card tray, 1906. Manufacturer: Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik, Germany. Pewter and silver, 209 x 303 x 238mm, GH004247.

Opposite: This pair of WMF vases featuring women playing musical instruments was bought from Treasure Box Antiques on Manners Street, Wellington, in 1969.

Vases, c.1905. Manufacturer: Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik, Germany. Britannia metal, plated metal, 185 x 100 x 90mm, GH004248/1, GH004248/2.

212 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Art Nouveau

Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Art Nouveau

Art Deco and the interwar years

ollowing the devastation of the First World War, the early 1920s were marked by a period of optimism about building a more egalitarian global community. Mass production, consumerism and new technology enhanced the everyday lives of the rising middle classes as the radio, the motorcar, commercial air flights and domestic electricity enabled a more connected society. In the design world, tradition was rejected in favour of progressive design and ideas. New forms of architecture included skyscrapers and airports, and the cinema became a primary form of entertainment and communication. This was also the Jazz Age, which brought together music and dance styles. Developed in the United States, it quickly became popular across the Atlantic and as far away as New Zealand.

But the liveliness and optimism of the Roaring Twenties concealed ongoing economic weaknesses. The British economy was fragile and taxes and housing costs were escalating. In Germany the 1920s was a period of impoverishment as the German state struggled with the reparation obligations that had followed its military defeat. In New Zealand the economy fluctuated: there were sharp recessions in 1921 and 1926, although export returns were also lifting living standards. New technologies were driving a stronger agricultural sector, and by the end of the decade most of the urban and rural population had electricity.1

The global Depression, sparked in 1929 by the Wall Street collapse, caused severe unemployment in several Western economies, although it also led to the exploration of more economic and competitive solutions for integrating art and industry, as seen in the ceramics industry in Britain.

This ‘Syren’, sometimes referred to as ‘Duveen’, pattern set by Royal Doulton was bought from Alma Foster in 1980.

Coffee service, ‘Syren’, c.1932. Manufacturer: Royal Doulton & Co Ltd, England. Ceramic. From Left: Cup, 60 x 75 x 75mm, CG001905; saucer, 15 x 115 x 115mm, CG001905; coffee pot, 205 x 75 x 145mm, CG001903; jug, 75 x 73 x 45mm, CG001904/1.

Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Epitomising the new stylish aesthetic of Art Deco, these glazed earthenware candlesticks designed by John Adams were produced shortly after the Paris 1925 exhibition for Poole Pottery, otherwise known as Carter, Stabler & Adams Ltd. With their symmetrical designs and stylised naturalistic decoration, Poole was embracing the new approach also seen in fashion and textiles of the era. Walter Cook bought these pieces in 1984 from a secondhand shop on Cuba Street, Wellington.

Candlesticks, c.1926. Manufacturer: Carter, Stabler & Adams Ltd (Poole Pottery), England. Designer: John Adams. Moulded earthenware, cream glazes. Larger candlestick, 215 x 205 x 131mm, CG001866/1; two smaller candlesticks, 172 x 106 x 106mm, CG001866/2, CG001866/3.

288 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Streamlined and ergonomic, these storage vessels with their striking glazes saved space in the small modern kitchens of the interwar period. They were designed for the Staffordshire company AE Gray, Susie Cooper’s first employer. The company did not make its own designs but rather decorated bought-in shapes. Cooper left the company in 1929 to set up her own business. The decorator of these particular pieces is not known.

Storage vessels, 1930–34. Manufacturer: AE Gray & Co Ltd, for Gray’s Pottery, England. Ceramic, glazes. From left: 190 x 158 x 158mm, CG001944/1; 152 x 118 x 118mm, CG001944/2; 104 x 86 x 86mm, CG001944/3.

316 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

These pages: These Art Deco wrapping papers, designed designed between 1933 and 1935, were acquired by Walter Cook from Wellington dealer David Owens at the closingdown sale of well-known Lambton Quay store Ferguson and Osborn in 1979.

Wrapping papers, 1933–1935. Unknown manufacturer, England. Paper. From left: GH004497, GH004498, GH004499, GH005764, GH004496.

Following pages: These thickly glazed Art Deco tiles are from a group of eighteen salvaged from the Government Life Insurance Building, on Customhouse Quay, Wellington, during its renovation in the mid-1980s. The Stripped Classical-style building was designed by the Government Architect John Mair and built during the later years of the Depression. Its entrance hall and stairway walls were decorated with dado panels of these tiles interspersed with brown mottled tiles, all made by the British firm Richards Tile Company, one of the largest tile manufacturers in the United Kingdom. Walter Cook displayed them in an Art Deco exhibition he curated for City Gallery Wellington in 1985.

Tiles, c.1937. Manufacturer: Richards Tiles Ltd, England. Ceramic, 10 x 153 x 77mm, CG001980/15, CG001980/16, CG001980/17, CG001980/18

322 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

Art Deco

Postwar Modernism

n 1945, as Britain and Europe began the long task of recovering from the brutal impact of the Second World War, there was a renewal of the vision of a fairer and healthier world. In the cities where bombing raids had destroyed huge swathes of neighbourhoods, affordable urban housing projects for the working and middle classes became urgent priorities. Architects and town planners got to work with designs that largely swept away the past.

Now, people would live in well-constructed and affordably built homes, layouts would be open plan, and there would be portable furniture and inbuilt storage. Mass production, standardisation and streamlined design, already emerging during the early years of the interwar period, were the three determinants that shaped modernism and made well-designed objects affordable.1

Manufacturers made new use of materials previously seldom encountered in domestic interiors: stainless steel was already fashionable in the 1920s and 1930s, and technical advances during the war made plastics and plywood more available. Traditional materials such as glass and pottery were reimagined as simple unadorned forms with abstract decoration, and the crafted object was praised for its beauty along with its intended practical purpose. Manufacturers and consumers kept up with design developments through the pages of professional and popular journals including The Architecture Review, The Studio Year-book of Decorative Arts, Design, Arts & Architecture (published in the United States), Ideal Home (published in Britain) and, in New Zealand, Home & Building, the journal of the New Zealand Institute of Architects since 1937.

This page: This popular Beswick figurine, inspired by CroMagnon cave paintings of bison, was bought from The Curiosity Shop, Newtown, Wellington, in 1985 for $80.

Ornament, c.1958. Manufacturer: John Beswick Ltd, England. Designer: Colin Melbourne. Ceramic, 125 x 85 x 85mm, CG001882.

Opposite: These two vases, a departure from English manufacturer Beswick’s usual novelty wares, drew inspiration from contemporary designs including Swedish ceramics. They were bought from Beverley Reid’s shop at 302 Tinakori Road, Wellington, in 1983 and Linley Halliday and David Owens’ Newtown shop in 1984.

From left: Vase, c.1958. Manufacturer: John Beswick Ltd, England. Ceramic, 282.5 x 150 x 150mm, CG001881; vase, c.1958. Manufacturer: John Beswick Ltd, England. Designer: Albert Hallam. Maker: James Hayward. Ceramic, 205 x 120 x 120mm, CG001880.

338 Towards Modernism: The Walter Cook Collection at Te Papa

The ‘Tenera’ breakthrough

enmark’s venerable Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Manufacture, established in 1775 under the protection of the Dowager Queen Juliane Marie, made a remarkable decision in 1959. To refresh its artistic reputation and reaffirm its modernist credentials, it hired six young female artists who had recently graduated from art and craft schools in Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

Within four years, Beth Breyen, Grete Helland-Hansen, Marianne Johnson, Mette Schou, Inge-Lise Koefoed and Berte Jessen had developed a new series named ‘Tenera’, Danish for ‘the young, the budding, the spirited’. Underpinned by a rich, dark-blue glaze as the dominant colour, striking stylised patterns and simple functional forms, and inspired by regional folk art traditions, the series appealed immediately to a younger generation of consumers. Tenera ware, which echoed the wider artistic scene of abstract art and revivals of styles such as Art Nouveau, was exhibited in Dallas and New York in 1963 to great acclaim. It played a major role in positioning Scandinavia as a progressive design force.

Although it was thoroughly contemporary, Tenera ware in fact reached back to an earlier glaze technique – faience, a tin glaze on earthenware. Working in a studio in Royal Copenhagen’s faience factory, the six women experimented on old, unglazed domestic ware and found that faience could produce a bright colour palette quite unlike the prevailing monochromatic ceramics of the time.

By the mid-1960s the six original Tenera artists had begun to leave the factory, although some returned occasionally for further work during

Above: Royal Copenhagen designer Berte Jessen some time in the 1960s. CLAY Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark.

Below: Royal Copenhagen designer Nils Thorsson. Wikimedia Commons.

the 1970s and 1980s. Several went on to have long careers. Berte Jessen stayed on until 1964, expanding ‘Junia’ ware into coffee and tea sets and also developing the series ‘Pastorale’ before moving to Germany with her husband Klaus Koehle. Jessen ran her own art studio between 1972 and 2002 and exhibited widely.

Tenera was the beginning of a new era for Royal Copenhagen. Nils Thorsson’s ‘Baca’ series followed soon after; like Tenera, it was modernist while also drawing on tradition.

1 Penny Sparke, The Modern Interior, Reaktion Books, London, 2008, p. 147.

2 New Zealand Institute of Architects, Home & Building, January 1956, pp. 30–53.

3 Charlotte Ashby, Modernism in Scandinavia: Art, architecture and design, Bloomsbury visual Arts, London, 2017, p. 186.

4 Rationing and austerity measures included the Utility furniture scheme that operated between 1943 and 1952, approving economical and well-designed furniture for newlyweds and those whose homes had been bombed during the war.

5 New towns, such as Harlow in West Essex, made it possible to relocate overcrowded and bombed-out populations to new urban centres. Many were home to Britain’s first modernist residential tower blocks.

Alexandra Goddard, ‘The furnished rooms: Rooms made to fit’, in Diane Bilbey (ed.) Britain Can Make It: The 1946 Exhibition of

Modern Design, Paul Holberton Publishing in association with V&A publishing and the University of Brighton Design Archives, 2019, pp. 145–51.

6 Victoria and Albert Museum, Liberty’s 1875–1975: An exhibition to mark the firm’s centenary July–October 1975, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1975, p. 110.

7 Ibid., p. 113.

8 Charlotte Ashby, Modernism in Scandinavia: Art, architecture and design, Bloomsbury, Visual Arts, London, 2017, p. 171.

9 The Auckland store Jon Jansen imported Swedish furniture, including Ostrom in 1952 (Home & Building, October 1952); and Wellington department stores James Smith’s and Kirkcaldie & Stains imported Scandinavian ceramics and domestic ware.

10 Ashby, Modernism in Scandinavia, pp. 182, 186.

The Royal Copenhagen factory in Frederiksberg, on the outskirts of Copenhagen, c.1930. Royal Copenhagen / Fiskars Group.

The Walter Cook library

This list of titles includes the design library amassed by Walter Cook between 1965 and 1996, either by purchasing books new or secondhand, including books and journals deaccessioned by public libraries or received them as gifts.

Abbate, Francesco (ed.), Art Nouveau: The style of the 1890s, Octopus Books, London, 1972.

Alexandre, Arsène, Newnes’ Art Library: Sir Edward Burne-Jones, George Newnes, London, c.1900–1914.

Amaya, Mario, Art Nouveau, Dutton Vista, London, 1966.

Anson, Peter F., Fashions in Church Furnishings 1840–1940, The Faith Press, London, 1960.

Art of the Book, 1914 (The Studio special number).

Atterbury, Paul (ed.), The History of Porcelain, Orbis Publishing, London, 1982.

Atterbury, Paul and Louise Irvine, The Doulton Story, Royal Doulton Tableware, Stoke-onTrent, 1979.

Baldry, Alfred Lys, Burne-Jones Masterpieces in Colour, TC & EC Jack, London; Frederick A Stokes, New York, c.1900–1914.

Barilli, Renato, Art Nouveau, Paul Hamlyn, London, 1969.

Battersby, Martin, Art Nouveau (The Colour Library of Art), Paul Hamlyn, London, 1969.

Beardsley, Aubrey, Under the Hill and Other Essays in Prose and Verse, The Bodley Head, London, 1904.

Betteridge, Margaret, Royal Doulton Exhibition 1979, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, 1979.

Bjerregaard, Kirsten, Design from Scandinavia No. 8, World Pictures, Copenhagen, 1978.

Boscaglia, Rossana, Art Nouveau: Revolution in interior design, Orbis, London, 1973.

Carrington, Noel, Colour and Pattern in the Home, BT Batsford, London, 1954.

Carrington, Noel, Design and Decoration in the Home, BT Batsford, London, 1952.

Cecil, David, Visionary & Dreamer: Two poetic painters, Samuel Palmer and Edward Burne-Jones, Constable, London, 1969.

Clark, Kenneth, Ruskin Today, Penguin Books, London, 1964.

Cooper, Jeremy, Victorian and Edwardian Furniture and Interiors: From Gothic Revival to Art Nouveau, Thames & Hudson, London, 1987.

Crane, Walter, The Bases of Design, George Bell and Sons, London, 1904.

Crow, Gerald H, William Morris Designer (special winter number of The Studio), 1934.

Daniel, Greta, Useful Objects Today, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1952.

Davey, Peter, Arts and Crafts Architecture, Phaidon, London, 1995.

Design Heute, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, 1988.

Designers in Britain, Volume 3 (a biennial review of graphic and industrial design compiled by the Society of Industrial Artists), Alan Wingate, London, 1951.

Designers in Britain, Volume 4 (a biennial review of industrial and commercial design in Britain compiled by the Society of Industrial Artists), Allan Wingate, London, 1954.

Durant, Stuart, Victorian Ornamental Design, Academy Editions, New York, 1972.

Eastlake, Charles E, Hints on Household Taste: In furniture, upholstery and other details, Dover Publications, New York, 1969. (First published by Longmans, Green & Co, London, in 1878.)

Fish, Arthur, John Everett Millais: Master Painters of the World, Cassell, London, 1923.

Garner, Philippe (ed.), Phaidon Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts 1890–1940, Phaidon, London, 1978.

The Walter Cook library

TOWARDS MODERNISM: THE WALTER COOK COLLECTION AT TE PAPA

RRP: $75

ISBN: 978-0-9951384-7-6

PUBLISHED: June 2025

PAGE EXTENT: 408 pages

FORMAT: Flexibind with jacket SIZE: 250 x 190 mm

FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO ORDER https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/about/te-papa-press/contact-te-papa-press