PULSE The

Note:

Thank you for picking up this year's copy of The Pulse. We are excited to take this op- portunity to highlight our community’s tal- ents: art, essays, and poems.

The focus of this year’s edition is on time- points: we will highlight pieces that explore our beginnings first. In this chapter, we look towards our peers’ paths into medicine, and the moments that fostered our growth.

We then focus on endurance: the times throughout our careers that have challenged us or strengthened us. Regardless of where we are in our careers, medicine can both be wonderfully rewarding and incredibly diffi- cult. We understand that many of these piec- es were born from difficult circumstances, some completely outside medicine. We hope that the act of writing, reflecting, and sharing allowed authors to process the good and the bad.

Finally, the last chapter will be reflections from fourth year medical students. We in- vited members of 2023 to re-read their anatomy reflections from first year. Many of us remarked on our first patient, our donor who we learned from. Now as fourth years and soon to be residents, we prepare for new firsts to come.

We thank you for reading and want to con- tinue to encourage anyone to keep creating in whatever way brings you joy!

Ariana Mirzada & Hannah Roach

Here is an old copy of The House on Mango Street.

The yellow $7.45 price sticker is still on the cover (of which the bottom right corner has been torn), and the spine is wilted.

Etched inside are annotations in red, green, black ink.

Some pencil.

The spiky handwriting of my mother, ten years older than I am today, learning English at the community college. She scribbles “imagery” and “metaphor” into the margins.

S’s linger next to the similes like stamps. Stars twinkle over the vignette titles.

On page 91, she writes, “No matter somebody is poor, he must have goals in his life.”

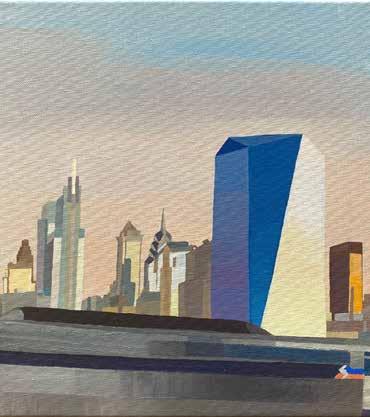

Now, here is my apartment in the city (the friendly concierge smiles and waves behind her tall desk).

I never got around to buying a bookshelf, so poetry books and critical-care guides, medicine reviews and novels pile up on the A/C unit, on my nightstands.

I live only twenty minutes away from the medical school, and just two blocks down from the community college. Ten years younger than she was then, I pass by those yellowed bricks as I walk to the art museum, go to see a friend, run to the Schuylkill.

I pass by the stairs where she sat, thinking about rent, waiting for my dad, wishing for a car, dreaming of green cards. Dreaming for the four of us.

Here are those stairs. And here is my mother, sitting. In the bag next to her: The House on Mango Street, some yellow legal pads, assorted pens, a pack of chewing gum. The seeds of our future in America smell like Wrigley’s Doublemint.

Rolled up in her hand, the cash my dad left for her this morning on the kitchen counter in the apartment on Woodhaven. The seeds shift as she rises and shoulders her bag. She waves goodbye to a classmate before bounding toward Spring Garden and Broad, disappearing down the subway stairs.

The trauma ED physician slumped back in his chair, clearly exhausted and burned out, his disheveled gray hair in need of a serious trim. Looking beyond us, he spoke suddenly, “If there is anything you are interested in outside of medicine, anything, do that instead.” It was unclear if his address was meant for us or if it was perhaps a plea to his younger self. I sometimes think back to that winter externship in the ED as a pre-med and wonder if I should have heeded his advice, however jaded. Where else would I be and what would I be doing if not for my pursuit of being a clinician? I was close to double majoring in studio art, but instead, I chose pre-med with a dollop of neuroscience and a sprinkle of psychology. Sometimes I dream about what life would be like if I had

pursued that art major. Would I be living by the ocean painting the morning waves and sand pipers who scuttled by, dipping their feet in the creamy puffs of sea foam? What would it be like to instead spend my weeks dissecting the colors of sunsets and investigating the curious shapes of shadows and light on my canvas? Would my clothes have stains of oil paint and linseed oil, my hair tangled from the humidity—you know that “crazy” artist look? While I’ll never know what could have been, I ultimately decided that I could simultaneously be a physician and an artist, and that the blending of the two could create something beautiful in its own right.

I put on my first pair of faded blue hospital scrubs in my senior year of high school. I was just 17. A friend’s dad was an orthopedic surgeon, and I watched from a distance as the surgeons repaired a rotator cuff tear, then an ACL, and finally released a Dupuytren’s contracture. There I was—a small

Asian girl with tan skin (courtesy of year-round outdoor soccer in California and my Japanese and Filipina melanin)—in a sterile sea of mostly white men. I felt partially out of a place, but I was still fascinated by all of it, and my friend’s dad was nice enough to talk me through some of the anatomical structures he pointed out on the laparoscopic camera. I didn’t fall in love with surgery that day, but the experience piqued my interest in medicine in general. The next summer after finishing my freshman year of college in Pennsylvania, I shadowed my pediatrician and my sports medicine doctor, both kickass female physicians I had always looked up to. I loved being in their clinics and getting to meet new patients as we zipped from room to room together.

Back on campus, I started volunteering with hospice at a

local nursing home and had my first experience with death. It was a depressing environment, especially in the cold of winter, but I also found tremendous beauty and meaning. My patient was an elderly woman with wispy white hair and vast blue eyes that made you feel like you were staring up into a cloudless sky. She was non-verbal and had dementia, but I slowly learned how to communicate with her. I sang her Christmas carols, played music from my phone, and sometimes we would just sit there, and I would hold her hand in mine. Aromatherapy bottles wafted lavender and rosemary as I told her stories and shared what was happening in my life. Though she couldn’t respond in words, I could read her subtle changes in facial expression, and that was plenty. A couple months after first meeting her, she passed away. It was expected, but still it felt sudden to me, and I felt alone with the weight of her loss.

Later that year, I worked with a

“Sometimes I dream about what life would be like ...what would it be like to instead spend my weeks dissecting the colors of sunsets...”

palliative care team and learned what it means to truly listen to patients. Dr. Gary Winzelberg, my hosting palliative care physician, introduced me to the principle of “Ask-Tell-Ask.” This model follows the framework of first asking the patient what they understand, then telling them specific information about, for example, their diagnosis or test results, and finally circling back to ask the patient what they understood from the new information and what their questions are. He also told me that it takes providers on average 11 seconds before they interrupt a patient. When we went to a family meeting in our patient’s hospital room, I witnessed difficult conversations but also breakdown in communication. Representatives from internal medicine, oncology, surgery, and palliative care were present. I listened in as one of the oncologists began to address

the team’s concerns to the family. When we finally left the room, Dr. Winzelberg turned to me in the hallway. He asked me to estimate how long the oncologist had spoken before the patient or family had an opportunity to speak. I guessed about 2 minutes. It was 7 minutes and 23 seconds—Dr. Winzelberg had been keeping track. Dr. Winzelberg recommended that I

Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. I was deeply moved by these books and further reflected on my recent perspectives from hospice and palliative care, contemplating the culture of how we die and what we value in our healthcare system.

Books became pivotal in my continued discovery of how to be a good doctor. I took a medical anthropology class that opened my eyes to the his-

read Being Mortal by Atul Gawande and When Breath

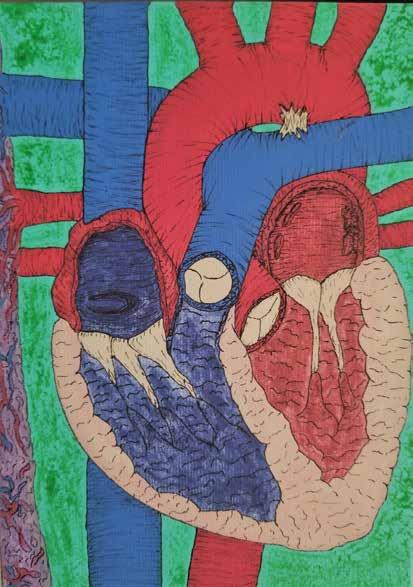

“Medicine could be dark and uncaring, ig- norant, driven by money and greed, racist, and un- just. However, medicine also had the capacity for so much good.”Art by Rebecca Mayeda

tories of non-Western medicine and read essays about traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine, herbal medicine practices, medical ethics, and the clashing of “modern” medicine with other cultures like in the book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down. Medicine could be dark and uncaring, ignorant, driven by money and greed, racist, and

unjust. However, medicine also had the capacity for so much good. Kitchen Table Wisdom was a beautiful collection of patient stories by complementary and alternative medicine specialist and pediatrician Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen. I loved peering into the window of her relationships with patients and learning about the intimate and

raw moments of humanity that emerged. She showed me how medicine could make people feel safe and trusted, and that once those bonds were established, healing could begin.

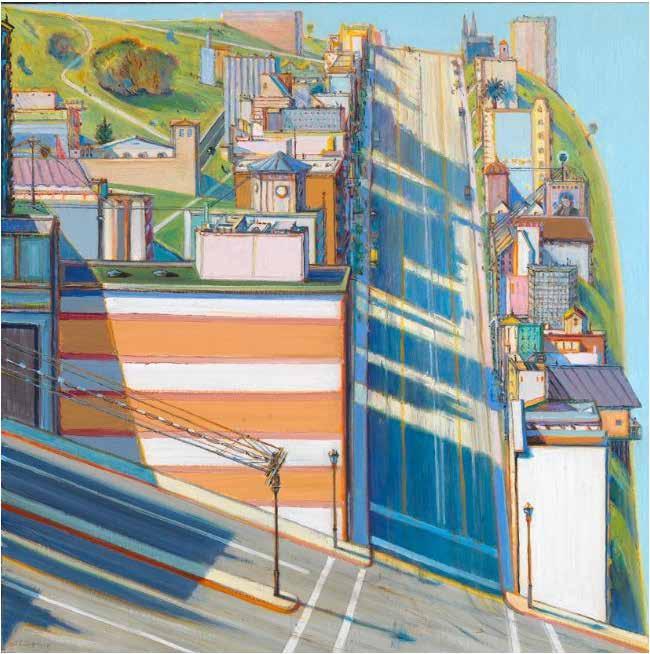

At each stage of my journey, I’ve realized how much more I have left in training—more time, more sacrifice, more sleepless nights. All my twenties flashing by like brushstrokes on a canvas. It’s like a

Wayne Thiebaud painting of the steep hills of San Francisco where I grew up. You reach the summit only to discover that you are in the ravine of the next upward climb. The path to medicine is exhausting, and I’ve sometimes felt lost along the way, but it’s breathtaking to look back as you finally rise above the fog and see clearly how far you’ve come.

I am the light of my life.

I am the light of my life, and I can be and do amazing things.

I do not have to live though anyone’s eyes Because that would make me very unhappy.

I appreciate my mom and dad but sometimes I wish they would ask me What I want to be in life

Because it has been so many failures for that reason

I want to not be a statistic but an achiever In my own right.

There are so many things I can chose from And me at 60 years of age-I chose to be a writer

And I’m glad it’s not too late.

And that’s why I want you To focus on your future for you.

I am the light of my life.

I am the light of my life

Helena Green

I met Helena Green about two years ago. We met on a Temple Street Outeach walk, and became fast friends. She has such generosity in her appoach to the people around her. Quick to hugs, vulnerability, and story-telling, all of her conversations were meaningful to me. We found many similarities, but one important one was writing. We both like putting words down on paper. When visiting her, one thing she asked for was notebooks and pens. She would fill them with stories, poems, drawings.

She tells us she has a dream of sharing her words. The adjoining poem in particular, she wanted to be shared with Temple medical students.

Her words, ‘There are so many things I can chose from...I chose to be a writer,’ are a poignant reminder of the agency we all possess, even as trainees, to choose the path we want.

I am pleased to include her words, not only so they can be shared, but that her words are amongst those of Temple trainees. We hope it represents the ongoing partnerships we aim to have with our patients. -HR

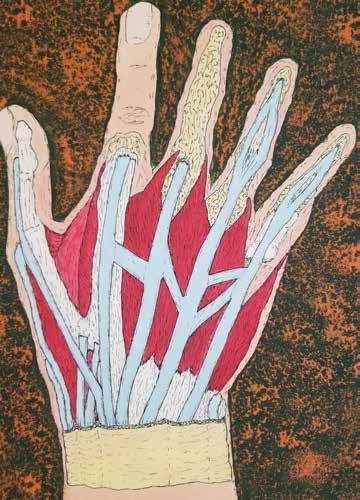

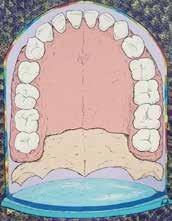

Paintings by Amy Stringer

Opposite Page

Top: ‘Hand’

Bottom Left: ‘Kidney’

Bottom Right: ‘Teeth’

Volteada

Carolina Patricia Ramos

Quería comenzar esto hace tiempo

Las letras ya no me vienen tan fácil

O, mejor dicho La creatividad se me escapa

Me siento de cabeza

Carolina Patricia Ramos

Volteada

Trato todos los días de seguir adelante

Leo y aprieto las teclas de mi computadora No hablo

¿Soy ser humano?

Gracias por recordármelo

Porque a veces me olvido

De quien soy

Yo me prometí

Antes de comenzar esta nueva etapa

Que iba seguir bailando Escribiendo Levantándome con una sonrisa cada día.

¿Y ahora qué?

¿Qué le digo a esa chica del pasado?

¿Le mentí?

¿Tú que dices?

translated by the author

Flipped

Carolina Patricia Ramos

I wanted to begin this a while ago

Carolina Patricia Ramos

Flipped

Words don’t come to me that easily anymore Or, better said Creativity escapes me

I feel like I’m upside down

I try every day to keep moving forward I read and press the keys on my computer I don’t speak

Am I human?

Thank you for reminding me Because sometimes I forget Of who I am

I promised myself

Before I began this new period That I would continue dancing

Writing

Waking up with a smile everyday

And now what?

What do I tell that girl from the past?

Did I lie to her?

What do you say?

how do you like anatomy?

it’s a lot of material, but I feel like I’m getting the hang of it how do you like anatomy?

I hate how difficult it is to sort out how I feel about it do you want a turn with the scalpel?

I’ll get some adipose tissue off of pec major do you want a turn with the scalpel?

it feels invasive to touch someone without their permission do you understand that this is a choice they made? the donor had full autonomy when choosing to sign up for this do you understand that this is a choice they made?

how could they be comfortable?

knowing that this was an experience they would never be aware of leaving themselves completely bare undefended

how could they be comfortable?

can you say that again?

is that the teres minor muscle?

can you say that again?

why don’t you listen to me?

are you tired and do you want to lie down? no, this chair is fine is this chair fine?

no, I’m so exhausted that my soul is weeping

I’m overstimulated to the point of fatigue, of lightheadedness even with all of my preparations, the storm seems to get harder to weather

I don’t want to do this

I don’t want to do this again the truth lies like nothing else, so nobody hears me

“are you tired and do you want to lie down?” yes, that’s typically the case but why bother?

it’s something I joke about often because the truth lies like nothing else, and I love the truth so I tell the truth, knowing that people will think it’s a joke

I’m always tired

I never feel rested sleep doesn’t really do much for me

I think about why I do this, and I wonder if it’s because the actual truth, stripped of humor, gives me no return on investment to give you what I am as I am, what can you give back to me?

“wow, that must be so hard”

“have you tried melatonin?”

“maybe working out before bed will help”

god complex aside, I often feel like a greek god, cursed with an ailment to keep me from staying balanced on my pedestal a facet I can never fully polish a scarf of pain that chills my bones bones that ache as turn over and over I am tired, but there’s no relief in lying down

pieces inspired by Mark Strand’s ‘2 Answers’

Hannah Roach

Where can I taste your songs

When can I dance your words and smooth your bones

Underneath your skin where they click and clack and whisper?

I’d like to walk along your pulse and make my own feet the electric spark--

The valve that opens and closes and pours your joy through Slippery veins.

Could you read the raindrops that hit you

Before they blink away into warmth?

How many drops and drips erode you away-Do I let them shave you down?

I’d ignite the seconds we have and watch them burn that brilliant golden lifetime

Could you paint my brain across the sky and what color would it be?

Smoke out the hours. You’d be green.

Why don’t you water the muscles around your fingers and sprout your stories

Bury your roots in sheet music

Sing the synapses down your spine and let me keep your rhythm. I’d snap along your nerves.

I could dream up a world and untie you from it

I would embroider you into the thin lining between veils

And watch the sun rise through you.

Originally printed in William Carlos Williams Poetry Contest Honorable Mention, 2022

Who in ICU and who in trauma bay

Who with compressions and who with shock

Who by apnea and who by asystole

Who is full-code and who is DNR/DNI

Who by bullet to the great vessels and who by internal iliac

Who by ectopic and who by hemorrhage

Who by no access to clean water and who by work conditions

Who by policy and who by apathy

Who by unsafe supply and who by detox

Who by medical mismanagement and who by cost

Who in pain and who in withdrawal

Who by ignorance and who by cruelty

But we must lessen the decree.

Anushka Shah

[START with how I love the way the word codon nudges my mouth into a kiss co and ends with a light tap of my tongue behind my front teeth don, as if to hint to the even more precious thing it is read for. in the same way, my lovesick study of the single freckle on the nape of your neck translates to waves of chemical sachets pulsing through my brain and I am circuited to hunger for more. in the same way, we fold your clean laundry unaware of the millions of proteins folding and unfolding in our bodies that are aware of our every move and STOP]

To Treasure

Rebecca Mayeda

Sea foam

Glistening, sizzling

Like crepe batter

Extending fingertips

Reaching out to Kiss the pebbles

Quartz

Gleaming white

Cool starlight

Like mochi

Or lychee

Nestled moons

Driftwood

Burnt sienna, Shadows of umber

Like rounded stone

Smoothed, splintered

Tumbling time

Sea glass jewels

Jolly Rancher jade

Glow neon light

Like amber drops,

For a moment, Bubbles retreating Cast an impression

A shiny cobalt glass Sinking, settling

To be renewed

57 days to match day

Efua deGraft-Johnson

sometimes I feel like a ghost haunting the halls of my own home unable to rest

I have no unfinished business in the traditional sense but I can’t slow down

I am pulled from bed and made to loiter, to loom, to linger.

what haunts me? unreceived “rank to match” calls the idea of going unmatched the idea of going matched unhappily yet bindingly the anesthesiology google sheet the feeling of being inadequate and underprepared yes, I have worked hard but is it enough? will it ever be enough?

my recurring nightmare is of being in high school with a looming exam for an english class I have never taken on books I have never read.

I guess all that to say is that I fear confidence or rather, I fear the consequences of confidence.

late at night when I appear merely an apparition floating by silently so as to not wake the living, time is finally rendered immaterial and the countdown insignificant.

match day marks the beginning of my career but it also marks a day when I can finally ascertain my final resting place and be freed from my ghastly wanderings

Four years ago, the class of 2023 wrote about the past seven weeks of anatomy lab. We asked members of the class to return to their words and reflect on the past four years.

The quiet was incredibly peaceful. If I went in the late evening, I could make it just in time to see the late summer sun setting behind the train tracks in the distance out the large panel window. “Alright, Mabel,” I’d say, using my nickname for her, “where’s that ulnar nerve, I know I had it the other day.'' So, there I would be; running my fingers across muscle fibers, digging out nerves again, trying to make connections to learn in

my own mind-the sun setting in the background: a sign from my donor that she was proud of all I was learning and the progress I was making. I often said a little prayer before I went into the lab. Not out of fear or regret of what I was doing to Mabel’s body (or the bodies of the other donors), but out of thanks. What an incredible gift to have given us: a group of anxious, firebrand first year medical students eager to learn everything under the sun.

Emily Hancin, 2019I think it’s funny that Mabel knew I was going to be a surgeon before I did. I wonder how she must have felt as I worked on her, knowing that my love of dissection would soon turn into a love of operating. I can imagine her eyeing me, a fledgling first year medical student, afraid to cut deeper than a tenth of a millimeter with the scalpel in my shaking hand. I picture her teasing me with a coy smile on her face as if to say, “I know something you don’t know…yet.”

I would always visit Mabel with the intent to leave in an hour, but I frequently lost track

of time. Similarly, I knew I loved surgery because of how rapidly the days seemed to pass for me as I assisted during operations. Working with Mabel instilled in me a deep fascination with human anatomy, maybe even a little too much. Surgeons have corrected me many times for accidentally moving the retractor as I tried to get a closer look at the structures inside a patient’s open abdomen. Surgery is a team sport, and I know my role for now is to assist the primary surgeon, but I do miss how selfish I could be when it was just Mabel and me.

One of my favorite parts of

coming in at the crack of dawn to round on surgical patients is watching the sunrise peek through the windows. Sometimes, I’m in the hospital late enough to see the sunset, too, just like I did when I visited Mabel. Seeing the sun reminds me there’s still a world outside, no matter how much of mine I spend in the hospital. I often leave with the same kind of gnawing hunger pains and tired eyes I experienced when I spent too much time with Mabel. Despite this, I walk away deeply satisfied with the small impact I know I have made on the souls entrusted to my care.

I still pray. I have made cathedrals out of scrub sinks, stairwells, patient rooms, empty hallways, elevators, and bathrooms. My prayers there are different than the ones I used to say with Mabel. They are still words of thanks, but they are also sincere pleas of supplication. The patient on the operating room table is alive, and part of my job is to keep it that way. They have a family waiting anxiously somewhere for a phone call that, “everything went perfectly.” Nothing is ever guaranteed in surgery; that’s part

of what I love about it.

I wonder about what that first day of surgery residency is going to be like, the relationships I will form, the patients whose lives I will touch, and what kind of person I will be when I walk out of the hospital on my last day. I thought about that when I started medical school, too. I remember wondering if I would still be just as mesmerized by the human body when someone called me Dr. Hancin for the first time. Lucky for me, I think I am. Someday soon, I will be the one performing the operation, and another medical student will be holding the retractor. When this day comes, I’ll remember Mabel and all she taught me. I’ll remember the childlike wonder and awe that comes with seeing the inside of another person for the first time. I’ll pause, and I’ll tell the medical student to hand me the retractor so that they can come around and take a closer look. I’ll wait to feel the warmth of Mabel’s coy smile from somewhere out there, and I’ll smile back.

Emily Hancin, 2023There is a desire to establish a connection to the humanity of the donor, whether it’s achieved through naming, attempted correlation of anatomical findings with their life, or fantasy of their personality. I'm guilty of these protective actions. And that's exactly what they are, actions to protect us from the desensitization we feel creeping in. To give us one last hope that maybe we're normal and maybe we can look away when we see blood spurting. At best these are helping us to connect to and appreciate our future patients' full lives; at worst they are plastering fiction over the true lived experience of our donors.

When I looked down at this donor, I stopped seeing an imagined life and saw instead a fullness that I had no purpose, and no hope, trying to recreate.

I saw a de-identified, not unidentified, person. They were not robbed of their humanity by this process. Instead, they completely gifted it to us, locked away in a chest to which we'll never have the key. There is no abandonment of humanity in the treatment of the body, but the exact opposite. We fully embrace the humanity of another when we recognize their body - in our case, the entirety of our donor - as just that. Our bodies, though sacred in many ways and deserving of care and respect, are only our bodies. Life is robust and complex and meaningful beyond its physicality. With the life gone out of our donors, there was nothing left but the fullness of their lived experience, entrusted to us to honor with our ignorance.

Eric Gramszlo, 2019I wrote that our anatomy donors’ humanity was locked up, out of reach. That was true in the instance – we knew them deeply but not humanly. In the ensuing years, I’ve come to realize that all patients come with just such a chest in which they secure their humanity. If we’re nice about it, though, sometimes they’ll lend us the key.

Eric Gramszlo, 2023Searching through every crevice of my mind, I try to remember where I’ve seen your hands before. As I delicately rotate your forearm, your hand falls into mine and it hits me— you have my Papa’s hands. Strong from a life dedicated to service, weathered by the years. Memories of his big hands enveloping my own, I wonder if you had a granddaughter who loved you as much as I loved him.

For the first time in medical school, I cry. Alone in the locker room, my soft whimpers echo, magnified to match my feelings. My tears are not a sign of weakness, but rather our shared humanity.

I stay late after lab that day. Scanning your frame, I stop at the thick lesions on your feet and hips—remnants of time

spent immobilized. I hope you didn’t suffer, that your quality of life wasn’t limited by your physical ability.

I remove the plastic bag concealing your face, determined to know my newly appointed teacher. Your creased eyelids are slightly open, revealing piercing blue eyes. I imagine those eyes staring out at your congregation each week, drawing them into your sermon. Even in your death, I can feel their warmth. Your chin is spotted with stubble, punctuated by a few missed spots where the hairs grow longer than the rest. I wonder if, like my Opa, you’d tell me how hard it is to shave once you turn 90.

I hope to never forget this feeling. Never forget the wisps of hair on the tops of your ears. Never forget the times I cried for you, my first patient.

Megan Patton, 2019Often, I found myself wandering back to patient rooms after the day’s “real” learning was complete. With me, tools far simpler than those I carried on rounds — apple juice and graham crackers, combs, razors, clean socks. Hidden in this silent curriculum of shared snacks, bed baths, and laughter, I found the same humanity that’d left me in tears during anatomy.

To say I haven’t cried for a patient since that day would be a lie, but I’ve gotten pretty good at holding them back (at least until I’ve left the room). I would not be the doctor I am without the patients who’ve allowed me to bear witness to their journeys. They are forever etched into my memory. Megan Patton, 2023

Ariana Mirzada

Hannah Roach

Mike Vitez

Naomi Rosenberg,MD

Efua deGraft-Johnson

Eric Gramszlo

Helena Green

Emily Hancin

Rebecca Mayeda

Amal Oladuja

Megan Patton

Carolina Patricia Ramos

Amy Stringer

Anushka Shah

CONTRIBUTORS COVER Rebecca Mayeda

ADDITIONAL ART

Hannah Roach