BC Teachers’ Federation Nov/Dec 2025

Teacher

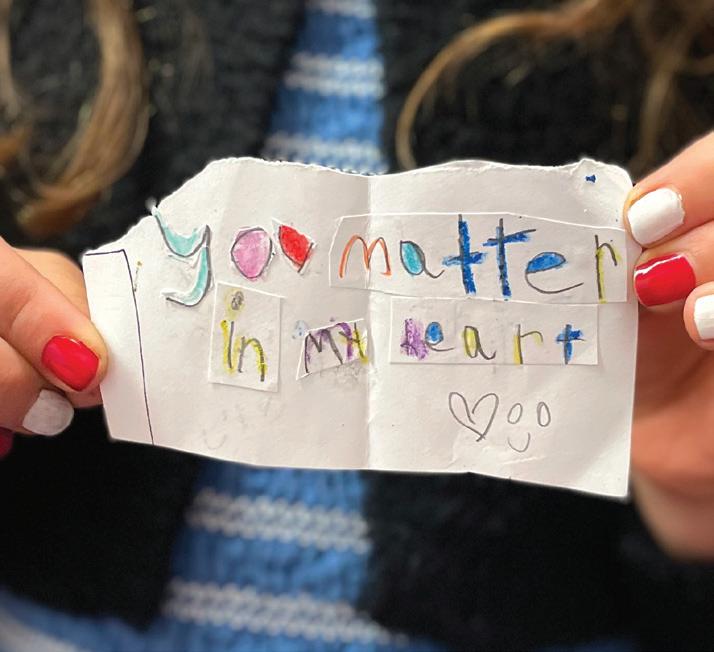

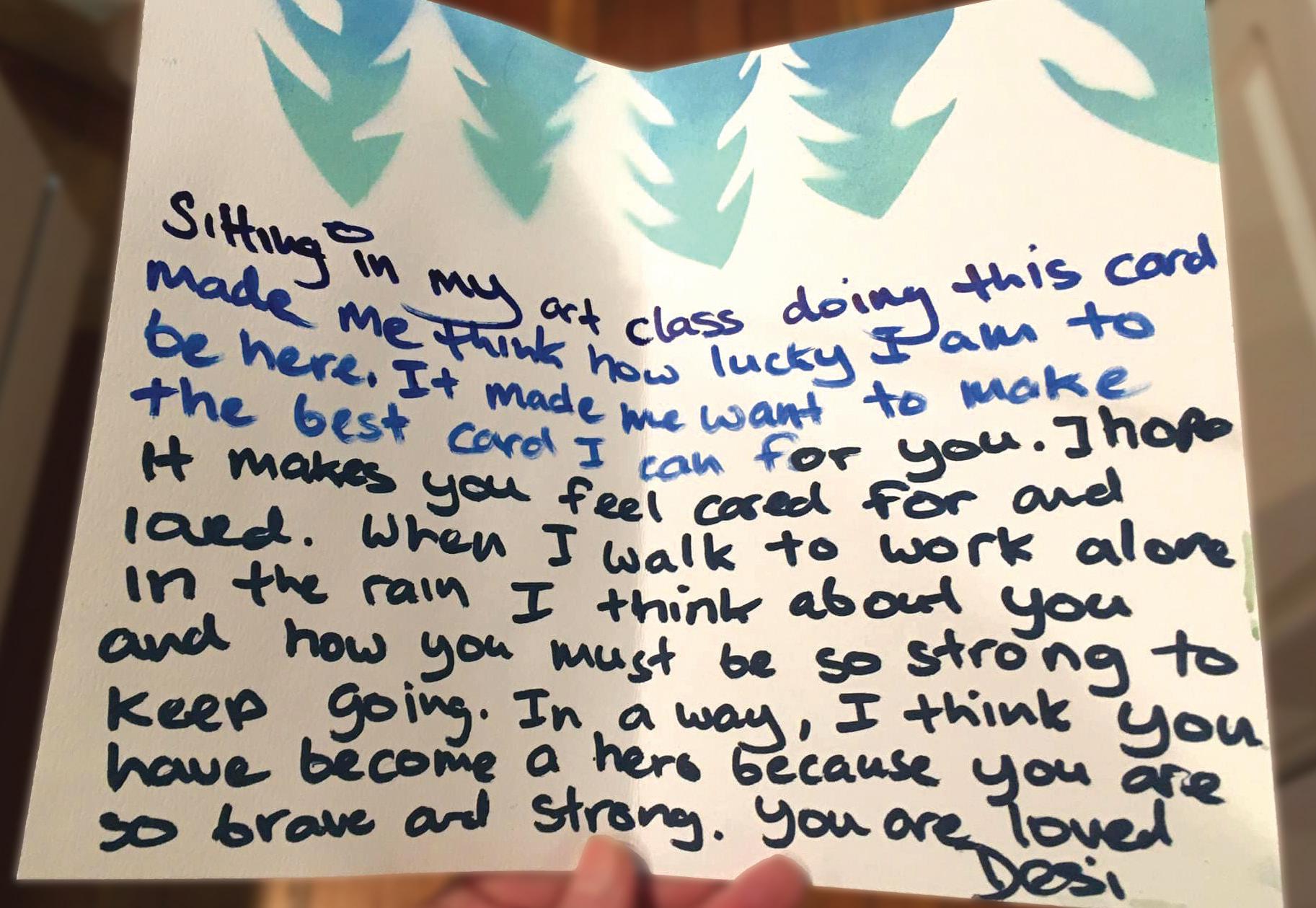

Everybody Deserves a Smile

Pictured is a message from a student in the EDAS club. Read about the program and how it provides care packages to thousands of unhoused people during the holiday season on pages 10–13.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Peace River region local profile pages 20–23

Empowering school-based teams pages 26–27

IN THIS ISSUE

Articles reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily express official policy of the BCTF. The BCTF does not endorse or promote any products or services advertised in the magazine.

Advertisements reviewed and approved by the BCTF must reflect BCTF policy and be politically, environmentally, and professionally appropriate.

THIS IS YOUR MAGAZINE

Contact us

BC Teachers’ Federation

Toll free 1-800-663-9163

Email teachermag@bctf.ca

Web teachermag.ca

Editor Sunjum Jhaj, sjhaj@bctf.ca

Assistant Editor/Designer

Sarah Young, syoung@bctf.ca

Advertising teachermag@bctf.ca ISSN 0841-9574

Do you enjoy writing? Have a story to tell? Know of a project at your school or in your local you want to share with colleagues? Then consider writing for Teacher, the flagship publication of the BCTF! Submission guidelines are available at teachermag.ca

We also welcome letters to the editor. Send your letter to teachermag@bctf.ca

Teacher reserves the right to edit or condense any contribution considered for publication. We are unable to publish all submissions we receive.

Deadlines

Jan/Feb issue November 2025 March issue January 2026

May/June issue March 2026

BCTF Executive Committee

Jelana Bighorn

Shannon Bowsfield

Brenda Celesta

Adrienne Demers

Carole Gordon

Mary Lawrence

Frano Marsic

Hallan Mtatiro

Chris Perrier-Evely

David Peterson

Trevana Spilchen

Robin Tosczak

Winona Waldron

Teacher Magazine Advisory Board

Nandini Aggarwal

Alexa Bennett Fox

Robyn Ladner

Tamiko Nicholson

Kristin Singbeil

Carole Gordon, BCTF President Rich Overgaard photo

“Our solidarity with other unions is vital; it reminds us that our fight for strong public schools is part of a larger struggle for equity and justice for all workers and families.”

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

DEAR COLLEAGUES,

As we move through November, many of us have settled into the rhythm of the school year. Our classrooms are thriving, our relationships with students are deepening, and the meaningful, often unseen work of teaching continues each day. This is a season of reflection and connection, a time to celebrate the incredible dedication, creativity, and resilience that educators bring to their practice across the province.

This issue of our magazine highlights that spirit through stories from our members. You’ll find personal reflections, professional insights, lesson ideas, and strategies for growth. You’ll also find a local profile of the Peace River North and Peace River South teachers’ associations, and a story about a transformative school project called Everybody Deserves a Smile.

The ideas shared in this edition reflect our greatest strengths as a profession: our willingness to collaborate, our commitment to learning from each other, and our focus on supporting students through creative and innovative teaching practices. They connect well to the incredible work of provincial specialist associations and locals to deliver meaningful and memberdriven professional development on October 24.

As we continue through the year, we also keep in view the broader landscape that affects our classrooms. The challenges facing public education—funding pressures, staffing shortages, and increasing demands on educators—are not ours alone. Across the labour movement, workers are standing together to demand fairness, respect, and better conditions. Our solidarity with other unions is vital; it reminds us that our fight for strong public schools is part of a larger struggle for equity and justice for all workers and families. When we stand together for fair working conditions, equitable funding, and respect for all workers, we amplify our collective voice and help create a more just society for everyone.

I encourage you to listen to and share the messages shared by our colleagues from across the labour movement. Together, we will continue to build the kind of schools and communities we all deserve.

In solidarity,

Carole Gordon BCTF President

MESSAGE DE LA PR É SIDENCE

CHER·ÈRES COLLÈGUES,

Alors que le mois de novembre approche, plusieurs d’entre nous ont pris le rythme de l’année scolaire. Nos classes sont dynamiques, nos relations avec les élèves s’approfondissent et le travail d’enseignement, si important et souvent invisible, se poursuit chaque jour. C’est une période de réflexion et de rapprochement, l’occasion de célébrer le dévouement, la créativité et la résilience incroyables dont font preuve les éducateurs à travers la province.

Ce numéro de notre magazine met en lumière cet esprit à travers les témoignages de nos membres. Vous y trouverez des réflexions personnelles, des perspectives professionnelles, des idées de cours et des stratégies de développement. Vous trouverez également un portrait des syndicaux locaux d’enseignant·es de Peace River Nord et de Peace River Sud, ainsi qu’un article sur un projet scolaire transformateur intitulé « Tout le monde mérite un sourire » (Everybody Deserves a Smile).

Les idées présentées dans ce numéro reflètent nos plus grandes forces en tant que profession : notre volonté de collaborer, notre engagement à apprendre les uns des autres et notre volonté d’accompagner les élèves grâce à des pratiques pédagogiques créatives et innovantes. Elles s’inscrivent parfaitement dans le travail remarquable des associations provinciales de spécialistes et des syndicats locaux pour offrir le 24 octobre prochain une opportunité de progression professionnelle pertinente et axée sur les membres.

Tout au long de l’année, nous gardons également à l’esprit le contexte plus large dans lequel s’inscrit nos salles de classe. Les défis auxquels l’éducation publique est confrontée—les pressions financières, les pénuries de personnel et les exigences croissantes envers le personnel enseignant—ne sont pas

« Notre solidarité avec les autres syndicats est essentielle ; elle nous rappelle que notre lutte pour des écoles publiques fortes s’inscrit dans une lutte plus large pour l’équité et la justice pour tous les travailleurs et leurs familles. »

seulement les nôtres. Dans l’ensemble du mouvement syndical, les travailleurs s’unissent pour exiger l’équité, le respect et de meilleures conditions de travail. Notre solidarité avec les autres syndicats est essentielle ; elle nous rappelle que notre lutte pour des écoles publiques fortes s’inscrit dans une lutte plus large pour l’équité et la justice pour tous les travailleurs et leurs familles. En nous unissant pour des conditions de travail et un financement équitable et pour le respect de tous les travailleurs, nous amplifions notre voix collective et contribuons à créer une société plus juste pour tous.

Je vous encourage à écouter et à partager les messages de nos collègues du mouvement syndical. Ensemble, on va continuer à bâtir le genre d’écoles et de communautés qu’on mérite tous·tes.

Solidairement,

Carole Gordon Présidente de la FECB

FROM COMPLIANCE TO CONNECTION Shifting how we support neurodivergent learners

By Mary Klovance (she/her), founder of The Neurodiversity Family Centre, counsellor, ADHD specialist, and teacher, Victoria

NEURODIVERGENT STUDENTS often feel different, excluded, and deeply misunderstood, especially in a school system that just doesn’t seem to be designed for their moving bodies and dopamine-driven focus. Likewise, when it comes to the success of neurodivergent students, teachers often wonder, “How do I get them to do the work?” But this is not the question we should be asking ourselves. Instead, we should be focusing on, “How can I remove barriers so that my students can be successful in my class?”

Neurodivergent students have a unique way of communicating and absorbing information. No two students are alike, and so providing opportunities to connect with and learn about your students is the best way to identify their preferred communication styles. Here are some ways to do this:

• Create an initial assignment that links the course content with learning some personal details about students. For example, highlighting a current “hot topic” and having students share how it affects them personally.

• Have a check-in question for attendance at the beginning of each lesson.

• While students are settling in at the bell, walk around and ask students what they did on the weekend and/or what activities they have planned for the week.

INCREASING OPPORTUNITY FOR PERSONAL AUTONOMY

One key trait of neurodivergence is the importance of personal autonomy, but here is where people get things wrong: we often think that autonomy is about allowing the student to choose what and how they are going to present their learning, but this can often be a roadblock for many overwhelmed students. Neurodivergent minds crave predictability in order to decrease anxiety, so it’s important to provide a framework of expectations. However, if there is too much rigidity within that structure, the neurodivergent brain can react defensively and shut down, which is often characterized by oppositional behaviour.

Project-based learning is something many schools have adapted into their curriculum. But when the scope of a project is too open, it can make it difficult for neurodivergent students—who already have difficulty with task initiation and decision fatigue—to choose a path. One of the gifts of neurodivergence is that it can help brainstorm so many fantastic ideas, which can make it hard to choose just one! All of this can increase overwhelm and trigger decision fatigue leading to mental shut down. Therefore, providing scaffolded options for students to choose from, such as option A, B, or C, and allowing each option to be adapted to better fit students’ needs and broken into smaller chunks, is an excellent way to provide much-needed structure and autonomy.

REDUCING PERCEIVED DEMANDS IN THE CLASSROOM

Although teaching asks us to focus on the content of what we are communicating, the most important thing is how we communicate that information so that it can be received and remembered. And the great thing about adapting your communication style to be more inclusive is that it can work for everyone! In order to reduce perceived demands, there are several ways to communicate efficiently that I like to call “staying curious.” Here are some examples:

Ask questions: Instead of asking a student if they need help (perceived incompetence) or to do something (demand), you can ask questions:

“What are you working on?”

“What do you plan to do next?”

Noticing: This option can help take the focus off the student and shift it to yourself, which lowers student defensiveness:

“I noticed your binder is still in your cubby.”

“I see you’ve got a few papers on the floor here.”

“I don’t see your textbook on your desk.”

Wondering: This option is a more indirect way to cue the student to identify problems to be solved:

“I wonder what supplies you’re going to need to do this project?”

“I wonder where your textbook is?”

“I wonder what else you might want to be doing right now?”

Neurodivergent students have unique needs that are often left unmet in the standard classroom, and that can increase distracting behaviours. Take a moment and think about how often a neurodivergent student may be corrected throughout the day versus a neurotypical student. Because of this, neurodivergent students can be unreceptive to help in order to “fit in” and not feel singled out. Here are ways to offer support subtly, without drawing attention to the student:

Ask permission: Instead of jumping in to support, ask for permission first:

“Can I grab you an extra copy of the textbook?”

“Do you mind if I go over the assignment outline with you again?”

“Do you mind if I help you get started?”

The “in” and “out” method: Don’t stick around for too long when a student shows that they are not interested in your support. Instead, use questions, noticing, or wondering to help them get started then allow them space to work on their own while also setting the expectation that you will be back to provide additional help. This prepares them for your return and allows them some independence and perhaps additional motivation since they know you will be back to check:

“Awesome, you’ve got all your supplies ready, I’ll be back in a few minutes to see how things are going.” Then walk away.

Provide options: If a student isn’t able to do the expected task in the moment, co-create a list of options for them:

“It seems like math is just not accessible right now; what other things could we work on until you’re feeling up for it?”

“Instead of working on this essay right now, maybe you’d like to go for a short walk/water break or finish up that worksheet from yesterday? What do you think?”

Chunking: When lecturing, break the information into smaller chunks. Pause often to ask questions or let students ask theirs, instead of saving all the questions for the end. This increases engagement and students are less likely to interrupt in fear of forgetting their question or comments. This also allows students time to integrate the information and engage with it, instead of asking them to memorize large amounts of information all at once.

Priming: When lecturing, prime information you wish to share so that students who are easily distracted and/or daydream can be “called back” to focus on important information. Use statements like “Make sure to write this down!” or “This is definitely going to be on the test!” or “Here is something really important to remember.”

Additionally, when sharing stories that are not particularly relevant, prime them with “I have a funny story to tell” or “This isn’t about the assignment, but I want to share a story,” which helps students decipher the difference between the teacher’s storytelling and important academic information to memorize. For students with limited focus, distinguishing between important and merely interesting information can be hard. Teachers should emphasize what’s essential so their attention goes where it matters most.

You can also combine these strategies:

“I wonder where your textbook is; can I grab you one from my desk?”

“I noticed your book is in your cubby; may I go get it for you?”

Supporting neurodivergent students isn’t about trying to force compliance or productivity—it’s about shifting our perspective and adapting our practices in a way that works for all different types of brains. If we can focus on building authentic relationships that honour individual communication styles, offer structured choices while allowing flexibility, and reduce perceived demands, we can increase student engagement and overall success. These approaches not only benefit neurodivergent learners but help create a more inclusive, compassionate, and supportive learning space for all. Please note, that it does not require “more work” to support neurodivergent students. Instead, it asks us to incorporate new strategies that can work well for all students. When we lead with curiosity, connection, and respect for autonomy, we move closer to a school system where no student feels like “the other” and every student feels seen, supported, and capable. •

SELF-DIRECTED PD

By the BCTF Professional Issues Advisory Committee (PIAC)

THE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LENS

At the centre of the lens are teachers and their learning, both as a collective and as individuals. The term “teachers’ professional development” is used to highlight its use both in thinking about individual PD and PD as a collective endeavor.

The Inner Ring: Key criteria

The inner ring consists of three factors that are necessary for an activity to be considered professional development. If any of the three are not present, then the activity should not be seen as professional development.

Diverse

Teacher-directed professional development opportunities should span a wide range of topics and learning methods.

Career-long Diverse

Appropriate opportunities for teacher-directed professional development span the full range of a teacher’s career.

Career-long

The Outer Ring: Necessary factors

The factors in the outer ring are critical to the success of teacher-directed professional development as a collective endeavor. In turn, this collective work provides the necessary conditions for all teachers to be able to create their own rich tapestries of appropriate professional learning.

Collaborative

Teacher-directed professional development is best when teachers work together to plan, to deliver and to share their professional learning.

Relevant

Autonomous R es ponsible roleas a teacher? Does this activityhelptheteachers Doesthis activity help me improvetheworkIdoinmy involvedimprove the work theydoasacollective?

profession?

TEACHERS’ PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

autonomyofmycolleagues?Hasthisactivitybeenvoluntari

Doesthisactivityjeopardize

Collaborative FundedandSupported

Teacherdirected professional development must be supported with time, information, respect, and encouragement.

Adequate funds for both individual and collective teacher-directed professional development opportunities must be available.

Funded and Supported

SELF-DIRECTED PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

(PD)

can be an excellent opportunity to develop specific aspects of your teaching practice in ways that best suit your needs and learning preferences.

In order for something to be PD it must meet the following three criteria as illustrated by the BCTF PD Lens (left):

Relevant: Does this activity help me improve the work I do in my role as a teacher? Does this activity help the teachers involved improve the work they do as a collective?

Autonomous: Has this activity been voluntarily chosen? Does this activity jeopardize the autonomy of my colleagues?

Responsible: Does this activity meet obligations to colleagues, collective agreements, and our profession?

The options for PD that fit within this framework are varied and open-ended. The following are things to consider as you think about and plan self-directed PD.

Your (contract) mileage may vary.

When considering self-directed PD, your local and your local collective agreement (CA) language around professional development will lay the groundwork for what is possible.

In most collective agreements, the main section to look at is Section F, which sets the following:

• negotiated rules and guidelines for PD

• professional autonomy

• how much funding teachers must get for PD and the process for approving PD.

Depending on the specific language in your CA, and how that language has been interpreted over time between your local’s leadership in their discussions with district management, you will experience different funding levels, rules, and cultures around PD.

When planning self-directed PD, it’s important to check your local language, local policies, and to make sure you have a current understanding of what the options are in your local. In addition to checking with your school staff rep and/or PD rep, attending local general meetings and social events is a great way to ask questions that get you up to speed on the constraints and opportunities you have for self-directed PD and other professional development options.

PLANNING SELF-DIRECTED PD

The following questions may help narrow down your specific needs and the suitability of certain self-directed professional development opportunities.

RESOURCES: Find links to the BCTF Pro-D Lens (left) and the listed resources (right) by scanning the QR code or visiting linktr.ee/PIACpro_d

Assessment of needs

• What are my strengths and areas that need developing?

• What are the needs of my students this year?

• What do I need to learn more about for my pedagogy/ teaching practice?

• Am I building on previous learning or is this new learning?

• What are my expectations from participating in this learning?

• Is it PD?

• How will it improve my teaching practice?

• How can I collaborate?

• Is this activity voluntarily chosen following the language of my local collective agreement?

• How does this activity support my colleagues in the profession?

• What supports do I need?

• Do I have the funds to engage in this PD?

• Do I need additional release time?

• Do I have autonomy to do this PD?

• Are there any other barriers?

• Who can help me (e.g., school PD rep, local PD chair)?

EXAMPLES OF SELF-DIRECTED PD FROM YOUR PIAC COLLEAGUES

Watch a webinar or video with colleagues. The National Film Board has a variety of documentaries, films, and lesson ideas for teachers to build off of. Materials on the website cover topics ranging from climate change, art, and health to reconciliation and inclusion.

Peer mentorship/consultation is an opportunity for teachers to work with colleagues on addressing particular aspects of their classroom practice or behaviour management that are challenging or areas of focus for PD throughout the year.

The Virtual Historical Thinking Institute program is intended to support teachers in designing history programs, courses, units, lessons, and projects by developing your understanding of historical thinking.

Facing History & Ourselves offers non-credit courses and webinars on different teaching topics as well as professional learning on using the resources they provide. Examples of webinar topics are building community, teaching current events, fighting against hate, media literacy, and democracy.

Farm to School BC is helpful to learn about sustainable agriculture and how to incorporate it into your classroom. The webinars cover topics such as grants, school food programs, school farms and gardens, indoor growing, and eco clubs.

UBC’s Indigenous Math Education Network has webinars to support educators in bringing Indigenous story work, social justice, and place/land into mathematics teaching practices.

The BC Association of Mathematics Teachers also offers prerecorded webinars covering strategies for teaching and assessing mathematics concepts. •

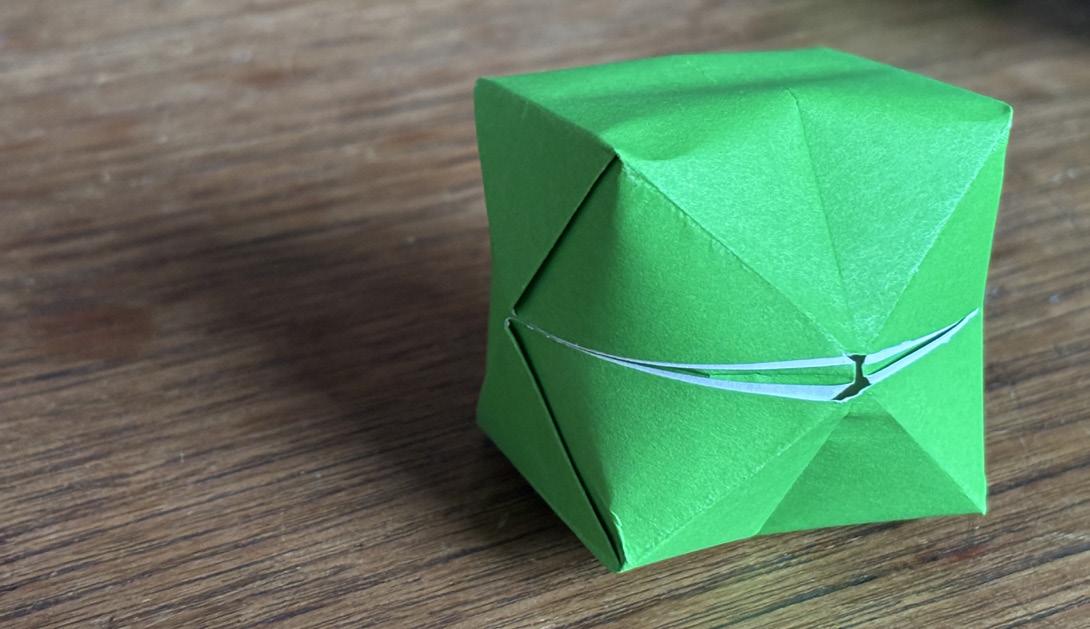

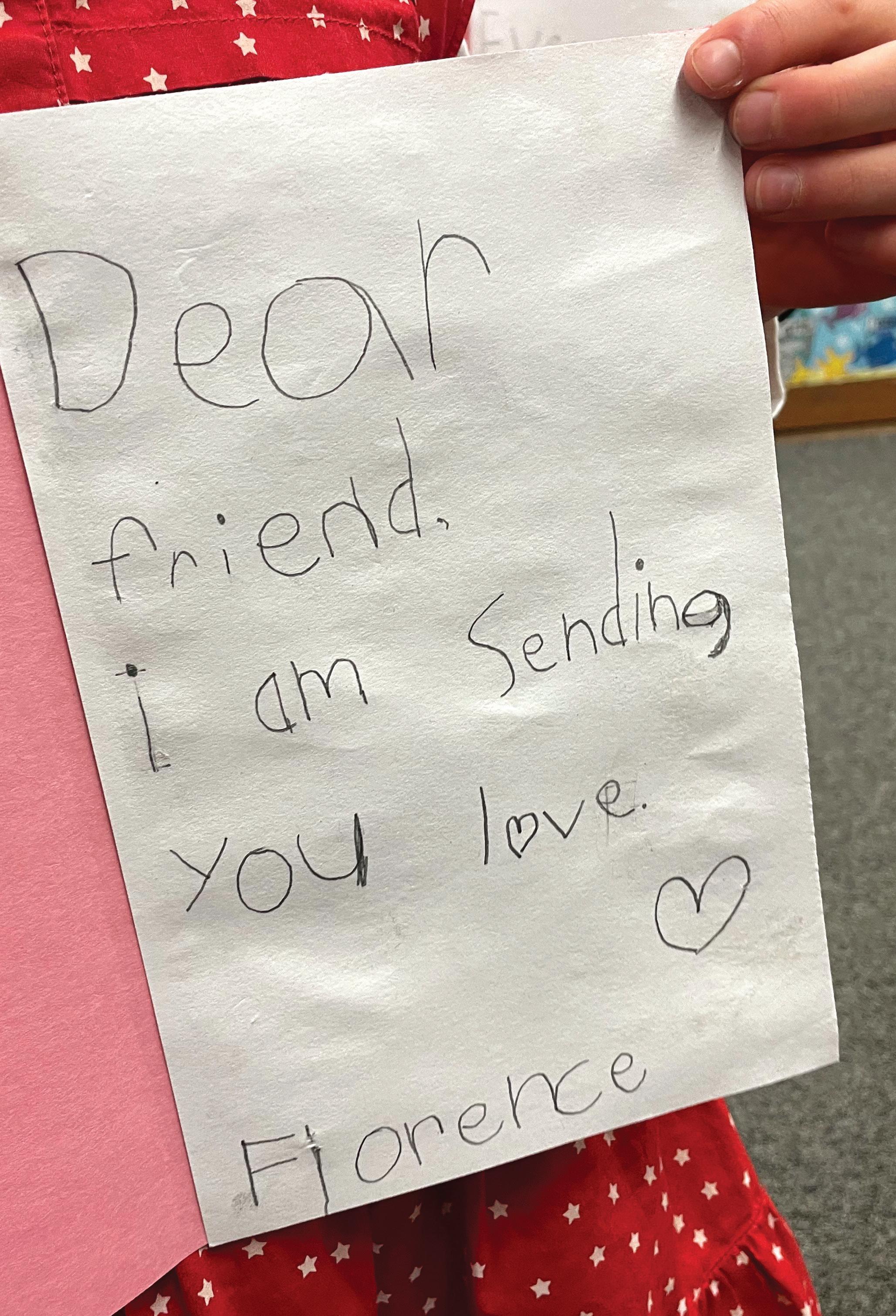

Students in the Everybody Deserves a Smile club spend months exploring compassion education, collecting community donations, and preparing and decorating care packages with personalized cards for people experiencing homelessness in their communities.

EVERYBODY DESERVES A SMILE Teaching empathy and living compassionately

ÉCOLE PUNTLEDGE PARK

ELEMENTARY has a history of celebrating the festive season with a focus on compassion and empathy. Students in the Everybody Deserves a Smile (EDAS) club, in collaboration with over 23 partnering school communities in Comox Valley, spend months exploring compassion education, collecting community donations, and preparing and decorating care packages with personalized cards for people experiencing homelessness in their communities.

The project started in 2004 when Madame Chantal Stefan and her three friends left 88 handmade care packages around downtown Edmonton. The packages were filled with sugar cookies, baked following her mom’s recipe, a pair of Costco socks, and a handwritten note expressing love and connection for anyone alone on the streets of Edmonton that Christmas. Those 88 care packages were hung from garbage bins, and overnight they all disappeared.

Madame Chantal introduced this project to her principal, Kevin Reimer, during her last teaching practicum at École Puntledge Park Elementary. With the collaboration and hard work of the Puntledge school community, this little moment of kindness has now grown into a district-wide initiative that includes thousands of care packages delivered across multiple cities in BC and Alberta, and even Montréal, Quebec and London, England.

Clockwise from far left: A care package decorated with a smile; a student’s message; decorated sugar cookies; packages ready to donate; students’ crafted cards on a line; a handmade card featuring Santa in the snow. All photos provided by EDAS.

The EDAS club gives Grade 7 students an opportunity to step up as leaders within the school. The students in the club meet with community guest speakers throughout the year, including families affected by addiction and the Community Coalition to End Homelessness, to learn about stigma, poverty, and privilege. Club members build their skills in leadership, project management, and public speaking while developing empathy and compassion.

These students and partnering school communities co-ordinate with local businesses and community members to organize donations for the care packages. Donations include woolen socks, toques, scarves, gloves, toothbrushes and toothpaste, soap, and—to keep the tradition alive—cookies baked following Madame Chantal’s mom’s cookie recipe (see page 14 for the recipe).

Thousands of sugar cookies are baked every year by Rotary Clubs, home economics classes, and families from the school community. Last year’s cookie callout saw nearly 9,000 cookies baked, decorated, and donated in Comox Valley alone.

Once the donation campaign is over and all the items for the care packages have been collected, the EDAS club and their teacher-leads organize a packaging day in their school gymnasiums. Up to 200 classes have collaborated to make this packaging day possible. Each student carefully packages donations into the gift bag that they have decorated with their classroom teacher. Included in each package is a heartfelt holiday card designed, decorated, and filled with a message written by a student to share hope and joy with the recipient. Each card is signed with the student’s first name to add a personal touch.

The packaging day is made more festive with local musicians creating an atmosphere of joy in the school gym. Families from the school community and EDAS alumni are also invited to participate in packaging and making deliveries.

“Students put so much care into making and selecting items for the care packages,” said Madame Chantal. “It’s heartwarming to watch.”

The EDAS care package project exists in tandem with larger classroom learning around empathy and compassion, rehumanization of unhoused people, addiction, stigma and stereotypes, poverty and privilege, leadership, service, hope, and impact. The project has accompanying resources for teachers to guide students through learning. The classroom kits and curriculum resources have all been co-created by the EDAS Teacher Team and teachers across participating districts. They include lesson plans, a study guide, book suggestions, videos, inquiry questions, vocabulary, and reflection prompts.

The goal of this learning is to help students develop an understanding of homelessness and addiction while also fostering empathy, compassion, and student leadership for action. The online resources are connected to the BC curriculum core competencies and big ideas for primary, intermediate, and secondary grades (scan QR codes below for resources).

The classroom learning happens throughout the fall, leading up to the packaging day when students thoughtfully package the gift bags with a more thorough understanding of the impact their work will have.

“I’ve learned a lot about poverty that people face in the Comox Valley. Working with others at EDAS gave me a chance to learn ways to make the world a happier place,” said Zoë MatherWhyte, EDAS club member.

EDAS ROADMAPS WITH LESSONS EDAS RESOURCES

The EDAS club students and partnering school communities then participate in delivering the care packages to homeless shelters, soup kitchens, library programs, low-income housing, support agencies, and directly to people experiencing homelessness on the streets. The opportunity to connect with community members who impart their experiences with homelessness and addiction has a powerful impact on students and staff.

“I walked into the shelter not knowing what to expect. As I started to meet the guests, I got to see a side of them that not many people do. Every smile I saw reminded me that love isn’t just in what we give but in how we give it,” said Magnolia Wise, EDAS alumni.

The Comox Valley EDAS club is part of a larger EDAS network across Vancouver Island and beyond. So far, over 32,000 care packages have been provided to community members by students in Campbell River, Comox Valley, Nanaimo, Port Alberni, Duncan, qathet, Victoria, Vancouver, and Red Deer, Alberta. Special EDAS projects also exist in Montréal, Quebec and London, England.

For students, the opportunity to learn about homelessness while also being compassionate and making a difference is invaluable.

As one Grade 5 student reflected, “The experience made me think that there is many reasons that people are unhoused and they don’t choose to be there. EDAS kind of changed how I feel about unhoused people.” •

Clockwise from top left: A banner encouraging students and community volunteers; care packages decorated with polar bears; a message from a secondary student; a message from an elementary student.

WINTER ACTIVITIES

EVERYBODY DESERVES A SMILE sugar cookies

The Everybody Deserves a Smile (EDAS) program provides thousands of care packages to unhoused people during the holiday season. It’s become an EDAS tradition to include these sugar cookies in the packages. Chantal Stefan, founder of EDAS, has shared her mother’s recipe below. Read more about EDAS on pages 10–13.

RECIPE

Makes approximately 70 cookies.

INGREDIENTS

For the cookies

5 cups flour

2 cups white sugar

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

2 cups butter, soft

4 eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla

For the icing

2 cups icing sugar

2 tablespoons milk (or liquid of choice)

Food colouring (optional)

Sprinkles (optional)

METHOD

Preheat oven to 375º

Combine flour, sugar, baking soda, and salt in a large mixing bowl. Add soft butter to dry mix and work into a crumbly dough.

Beat eggs and vanilla in a separate bowl and then add to mixture and combine.

Roll out dough and cut with favourite holiday shapes.

Place on cookie sheet and bake in middle of oven for 7–8 minutes, until just lightly browned. Allow cookies to cool.

For icing, whisk together icing sugar, milk, and food colouring, and decorate cookies with icing and sprinkles of your choice!

Across cultures, the winter months are a time for celebrating togetherness, often through food; adorning our homes, to remind us of the light and life that’s on its way; and restoring ourselves, to recover from the year behind us and prepare for the year ahead. Here are a few activities to help you celebrate, adorn, and restore in the coming winter.

WINTER BOOKS

PICTURE BOOKS

The Tea Party in the Woods by Akiko Miyakoshi

A Day So Gray by Marie Lamba

Red Sled by Lita Judge

Cold by Tim McCanna

The Shortest Day by Susan Cooper

Moon Song by Michaela Goade

When Winter Comes by Aimée M. Bissonette

Winter Lullaby by Dianne White

NON-FICTION

Wait, Rest, Pause: Dormancy in Nature by Marcie Flinchum Atkins

Over and Under the Snow by Kate Messner

Wonderful Winter by Bruce Goldstone

The Story of Snow: The Science of Winter’s Wonder by Jon Nelson and Mark Cassino

CHAPTER BOOKS

The Sea in Winter by Christine Day

The Polar Bear Explorers’ Club by Alex Bell

The Dogs of Winter by Bobbie Pyron

Voyage of the Frostheart by Jamie Littler

Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow by Jessica Day George

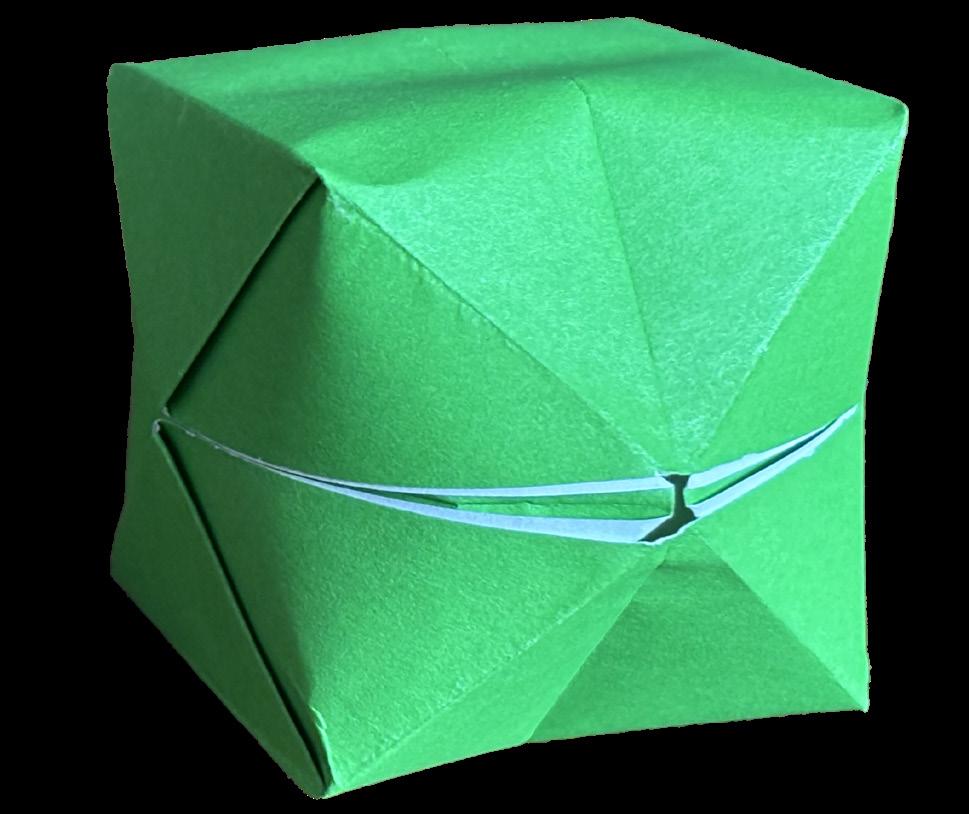

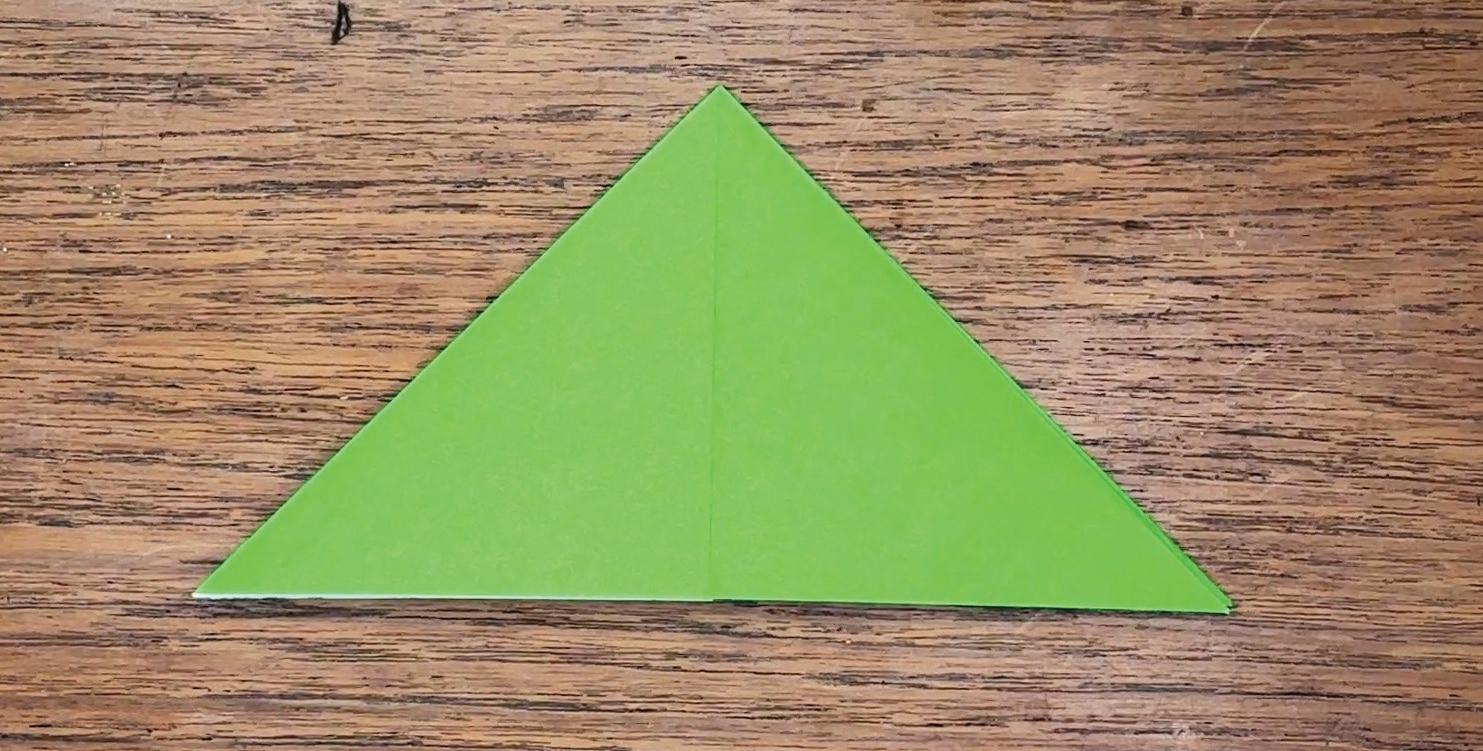

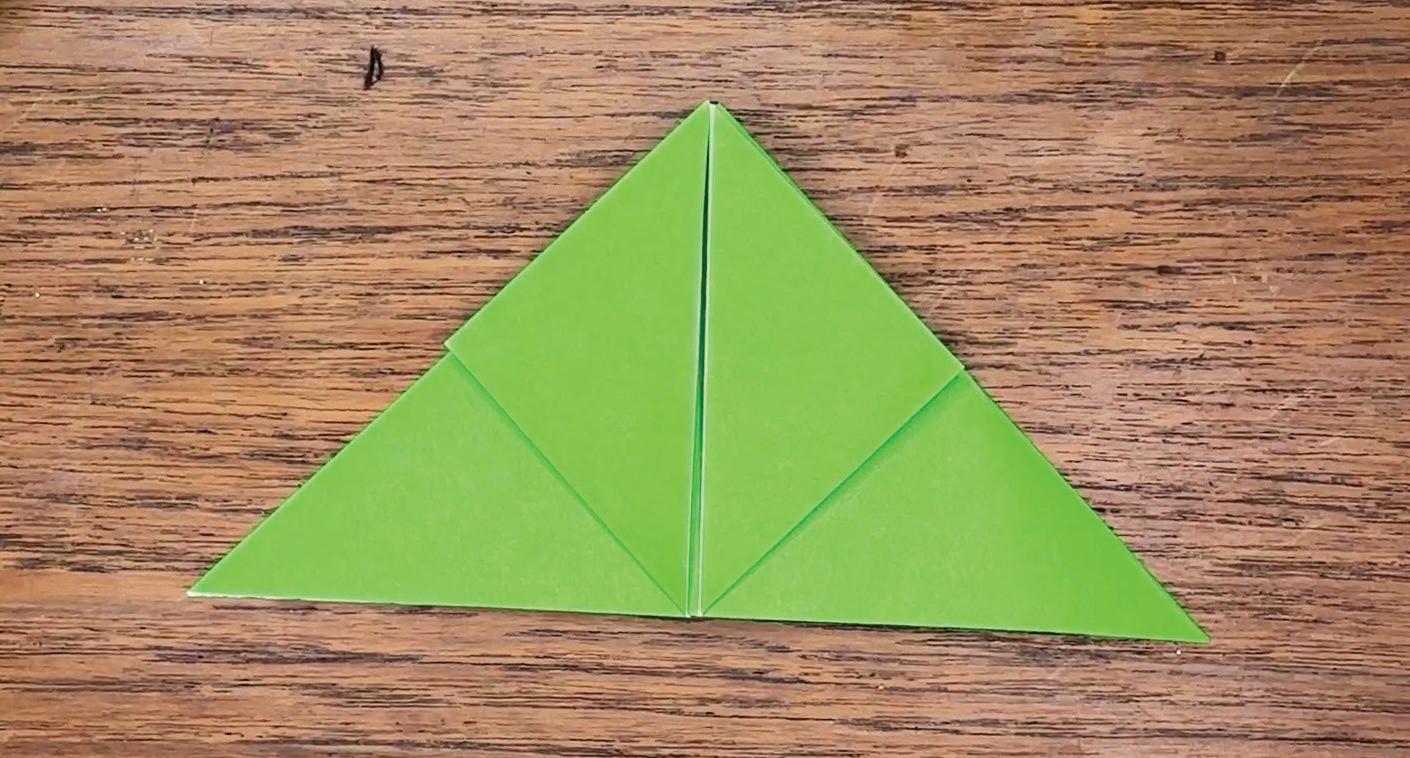

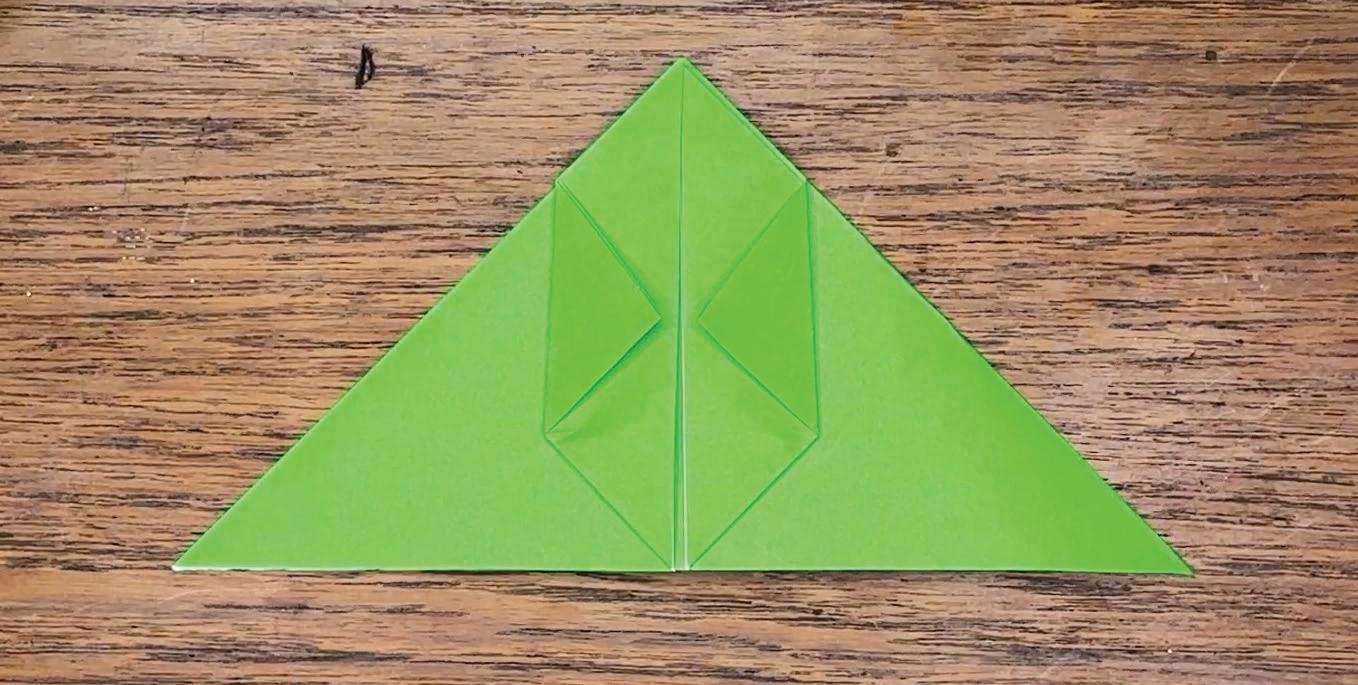

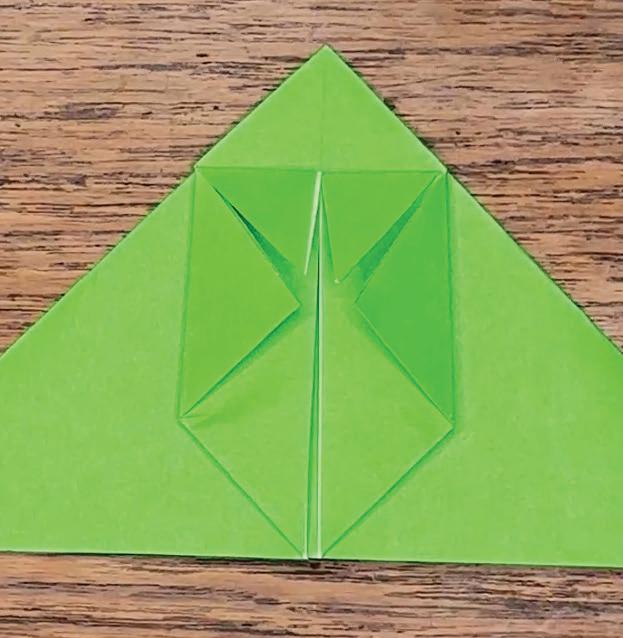

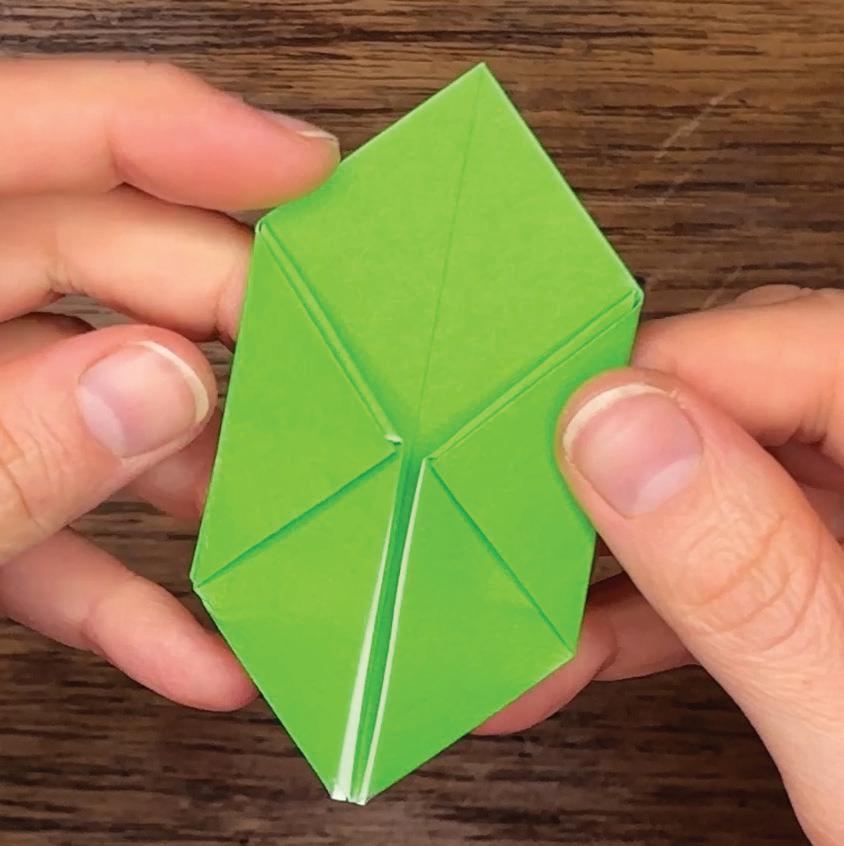

ORIGAMI WATER BOMB

See pages 16–17 for instructions on how to make a traditional origami model, the water bomb. They can be hung as ornaments or strung together for a garland. A demonstration video is available at teachermag.ca.

ORIGAMI WATER BOMB

STEP 1

With a square piece of paper right side up, fold in half like a book in both directions. Open folds and turn over.

STEP 2

With wrong side up, fold in half diagonally in both directions. Open folds and turn over.

STEP 3

With right side up, collapse one of the book folds made in Step 1 inward to create a triangle.

STEP 4

Fold the outer corners of the triangle up to meet the top corner. Fold upper layer of flaps only.

This traditional origami model can be hung as an ornament or made in multiples and strung into a garland. Visit the online version of this article at teachermag.ca for a demo video.

STEP 5

Fold the corners to the centre.

STEP 6

Fold the top points down to the centre to create two small flaps.

STEP 7

Fold the two small flaps into the pockets created in Step 5. Fold the flaps over first, to create the creases, then tuck them all the way into the pockets. This will create a cleaner finish.

STEP 8

Turn over and repeat Steps 4–7 on the other side.

STEP 9

One end of the piece will have an opening. Blow into the opening and gently shape the water bomb.

SOLIDARITY ACROSS SECTORS

Alex Kelsch and Jack Kelsch

AS UNIONS ACROSS THE PROVINCE take up collective bargaining and set picket lines to demand fair working conditions and wages, solidarity across sectors is more important than ever. We talked to three teachers and their family members, who are also unionized workers, to learn more about how being in a union affects them.

CAROLE AND IAN: CONNECTION AND CAMARADERIE

Carole and Ian first met on the job in 1993 when Ian, a computer tech and CUPE member was assigned to the computer lab at the school where Carole taught. Now, more than 30 years later, the union movement is a big part of their lives and marriage. Both Carole and Ian have served as labour council presidents and executive council members for the BC Federation of Labour, each taking a turn in leadership so they can support each other.

“Our relationship is what a union is: being there for each other,” said Carole.

When Carole and Ian started in the workforce, unions were more central to the lives of workers. “It was a social outing to go to union events,” recalled Ian.

Although unions aren’t always the first thing to come to mind for socializing in today’s world, they are still an opportunity to find connection and community.

Carole shared that she’s never felt alone in her work because she always has the union to lean on and colleagues from across unions who show support and solidarity. This solidarity is built on a recognition that we all want the same things: fair wages, a positive working environment where we can thrive, and security in our work and for our futures.

Ian’s act of solidarity last time teachers were on strike in 2014 was impactful and inspiring for Carole. CUPE workers were paid during that strike, but out of solidarity, they refused to cross picket lines to enter schools. Instead, Ian spent most of his working hours during that strike walking back and forth in front of their neighbourhood school and his own worksite to show his support.

“Solidarity has to be visible,” said Carole. “It’s important to show our colleagues from other unions that our solidarity is there, and it’s important to show the public that unions have support from across sectors.”

Carole and Ian make a point to show up for unions on strike even now. They can often be spotted out for a date night at picket lines, labour council meetings, or Canadian Labour Congress events.

ALEX AND JACK: DISMANTLING MISINFORMATION ABOUT UNIONS

Alex and Jack are twin brothers who have chosen very different career paths with one thing in common: unions. Jack is a unionized plumber who left a previous career as a chef, where he did not have a union to back him up. Being a part of a union has had a huge impact on his work-life balance and ability to advocate for himself with his employer.

“Without a union, it was a race to the bottom,” said Jack. “If you say you want to be paid appropriately, they’ll just find someone to replace you.” The inadequate wage combined with long hours and frequent uncompensated work led him to seek out a new career path.

Although he came to his current unionized job with some antiunion sentiment, he couldn’t deny the benefits of unionization once he had access to extended health benefits, a pension plan, and higher pay.

Alex, a teacher in North Vancouver, noted that being in a union is something he often takes for granted because it’s always been a part of his working life. Hearing about Jack’s experiences of working with and without a union reminds Alex of how the union supports his work.

“The fact that we have processes in place to bring concerns forward is empowering,” said Alex.

He recalls the union’s role in reinstating class-size limits when he first started out as a teacher, and the ongoing work of the union to protect quality public education.

Both brothers agree that one of the issues unions face right now is misinformation among their membership and the public. Anti-union sentiments or apathy toward unions are all too common. For workers, unions are the sole voice standing up for their rights and their quality of life. In many cases, the fight for workers’ rights is very similar across sectors.

“Unions sticking up for each other helps fight misinformation,” said Alex.

When people see unity among all workers and learn that we all have the same battles—underfunded, overworked—they see a collective voice and that can send a powerful message.

All workers can contribute to strengthening that collective voice in big and small ways.

“Stepping up to the mic and reminding your colleagues when another union is on strike is a way to show solidarity,” said Jack, who also presents to high school students on what it’s like to work in the trades, particularly as a unionized worker.

Getting information out about what unions are fighting for and how they can affect the lives of workers contributes to dismantling misinformation about unions. More support for unions means more support for workers overall.

REID AND MICHELLE: BARGAINING FOR A BETTER FUTURE

When asked about the commonalities between Reid’s job as a teacher (and now as the Chilliwack Teachers’ Association Local President), and his partner Michelle’s job as a street nurse, Reid responded, “Our professions are built on care: one for the body and one for the mind.”

Both jobs are shaped by the decisions of those in power, and both jobs have parallel struggles when it comes to staffing and safety.

The role of the union has always been to advocate for workers, but in today’s climate of cuts to public services, unions are also tasked with raising awareness about the issues that stem from underfunding.

“We need public support to fight for more resources, more staffing, better working conditions, and improved safety,” said Michelle. Unions are the collective voice that can help garner this public support.

For teachers, the public support is also important when it comes to representation for students, especially as it relates to the SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity) curriculum. The union has been the collective voice pushing back against narratives that spread hate or paint SOGI as dangerous.

“We need to make it clear that health and education are not partisan issues,” said Reid. “They’re public priorities.”

Collective bargaining is the best tool unions have to implement changes, and Reid noted that it’s not just about wages: it’s also about what we want our future to look like—what kind of health care system we want and what kind of education system we want.

Unions give workers the ability to have a voice when it comes to the systems we work and live within. “What is a union? It’s strength in numbers; it’s giving power back to the people so we can shape our collective future,” said Michelle.

In a bargaining year, solidarity for our collective future is more important than ever. Bargaining tables across sectors are connected; the tone and outcome of bargaining for one union is inevitably influenced by the results of bargaining for other unions. Showing support for colleagues across sectors helps send a stronger message to employers and builds pride among workers.

Both Reid and Michelle feel proud of their affiliation with unions. In Reid’s case, he comes from generations of unionized workers, including three generations of teachers. “It was embedded in me from a very young age that unions are supporting workers,” said Reid. “My family prides itself on helping build up workers.” •

P E ACE RIVER REGION

LOCAL PROFILE

Opportunity and innovation rooted in community

THE PEACE RIVER REGION of BC is home to a small percentage of the province’s teachers, but geographically the region is sizable. Its schools are spread out over hundreds of kilometres in BC’s northeast, near the Alberta border. The region is so large geographically, it actually consists of two locals: the Peace River North Teachers’ Association (PRNTA), which covers Fort St. John and the surrounding communities to the north and west, some of them more than 100 km away from the local office in Fort St. John; and the Peace River South Teachers’ Association (PRSTA), which includes Dawson Creek, Tumbler Ridge, and Chetwynd.

The region is undeniably beautiful. Wooded parks with networks of trails are easily accessible from every community, and the river and surrounding lakes provide a stunning backdrop for outdoor activities like fishing, hunting, and snowshoeing. But winters can be long and harsh. And with only one airport offering commercial flights in the region, some of the communities are isolated and remote.

“It takes some resilience and grit to live up here,” said Crystal Dutchak, a teacher who has lived in Fort St. John for most of her life. “But it’s a great place to be.”

When asked what keeps them in the region, every teacher interviewed said it’s the community.

Building a strong sense of community isn’t easy, and it certainly takes time, but the PRNTA and the PRSTA seem to have the formula down. As Elaine Fitzpatrick, PRSTA Local President, put it, you just need to “make sure every new member is welcomed, create plenty of opportunity to socialize in person, and always provide food.”

Elaine has taken on a personal responsibility to make sure members new to her local feel supported and welcomed. She reaches out quickly when she finds out a new teacher is moving to her local to help them get set up in the community. Sometimes that means helping them find housing or driving them to purchase a vehicle after they arrive.

Shindy Pletzer is a teacher who moved to Chetwynd two years ago, because the region provided employment opportunities for her family members in the resource industries as well affordable homes. She noted that “right off the bat, Elaine knew me by name and came and checked in on me,” an experience that contributed to her feeling supported.

Early in the school year, the PRSTA sets up new teacher orientation where they can meet colleagues from the district and take home a welcome package that includes teaching resources, books, and, as needed, extension cords to plug in block heaters for their vehicles.

But of course, community is not built in a day. The outreach, support, and friendliness only grow from the initial orientation through social events and mentorship opportunities.

“Right off the bat, Elaine knew me by name and came and checked in on me.”

– PRSTA member Shindy Pletzer (right), says of PRSTA Local President Elaine Fitzpatrick (left), who reaches out to every new member of the local.

“It takes some resilience and grit to live up here, but it’s a great place to be.”

– Crystal Dutchak, PRNTA member

“It shows new teachers that someone is watching out for you; you’re not left alone to flounder in those first few years that can be the most challenging.”

– Tyler Morrison, PRNTA Vice-President and mentor

The PRNTA is proud of the mentorship program they have built up over the years. New teachers (or new-to-the-role teachers) are paired with experienced teachers and supported in collaborating and learning from each other. “It shows new teachers that someone is watching out for you; you’re not left alone to flounder in those first few years that can be the most challenging,” said Tyler Morrison, PRNTA Vice-President and a mentor in the local program.

The mentorship program is just one part of the professional development (PD) on offer in the Peace River region. The districts and locals collaborate to put on numerous workshops, conferences, and learning opportunities for teachers.

One locally specific opportunity is the Indigenous Learning Day that takes place in Peace River North every year. Elders and community members from the local First Nations put on workshops covering topics including reconciliation, storytelling, art techniques, and land-based learning. The locally specific workshops are combined with keynote presentations from nationally acclaimed speakers, including Niigaan Sinclair.

Members in both locals are also supported to exercise their professional autonomy in pursuing professional development outside of local offerings.

“We see local specialist associations forming and applying for funding to host their own PD, we also see members using their PD funds to attend larger conferences in the south or take on learning that will support the needs of their students,” said Donna Bulmer, PRNTA Local President, who is proud of all that her local has achieved for PD in the collective agreement over the past several decades.

For Crystal, the flexibility to pursue PD that is relevant to your teaching allowed her to take training on Smart Learning, a framework to help deepen student thinking using metacognitive skills. She is now a Smart Learning facilitator who shares her learning with her colleagues to support them in implementing scaffolded learning using the framework.

In both locals, through positive working relationships with the districts, teachers’ professional autonomy is supported and upheld.

For Fort St. John teacher Ryan Windhorst, professional autonomy has given him the freedom to pursue unique learning activities for his students, such as making leather goods in his outdoor education class. This very popular class activity gives students the opportunity to work with leather to craft mittens, saddle bags, or knife sheaths using techniques pioneered by Indigenous Peoples.

Since there is no provincial outdoor education curriculum, the outdoor educators from different grade levels collaborate to ensure their curriculums complement each other without repetition.

“If you have an idea and a plan in place, people will support you,” said Ryan.

The opportunities for growth in the Peace River region are unique. The supportive atmosphere enables teachers to take on leadership roles. The collaborative culture allows teachers to work with colleagues across grade levels and subject matter. And teachers can easily try out different teaching positions.

Susie Hall, a Dawson Creek teacher who moved from Ontario six years ago, has had an opportunity to take on teaching roles that allowed her to grow as a professional. Her current role is literacy co-ordinator in the district.

Both Peace River districts have a strong focus on literacy education, combining new literacy education programs with tried and trusted literacy strategies.

Susie’s warm welcome from the staff rep at her first school inspired her to take on a staff rep position at her next school. Now she is a local representative and stays involved in her local union to advocate for her colleagues.

One of the biggest challenges these local unions face is the teacher shortage. While recruitment and retention challenges exist in nearly every district across

the province, they’re felt more acutely in the Peace River region.

The local presidents work hard to help new teachers build community, and the districts are investing into mentorship and PD with hopes that these things will help teachers feel successful and connected and, in turn, stay in the community.

However, the shortage is so severe that there are dozens of uncertified teachers working on letters of permission in both school districts. The locals do their best to support uncertified teachers through training and workshops, but these are no replacement for teacher education programs.

The district is testing out hiring bonuses as a way to incentivize certified teachers to move north. This solution, however, is inequitable.

“We need to support and motivate people to enter into teacher training programs,” said Elaine, who sees forgivable student loans as a more equitable and sustainable solution that would help address the problem.

The TTOC list is also chronically understaffed in the region. Teachers often feel guilty taking a sick day because they know an unfilled absence negatively affects the entire school—both staff and students. This contributes to teacher burnout and ultimately works against all the efforts undertaken by the local and district to retain teachers. The lack of

“I know all my neighbours and colleagues, and these are good people. It’s the village that’s helping raise my kids.”

– Ryan Windhorst, PRNTA member

TTOCs also means that teachers aren’t able to take remedy time.

These issues leave mid-career teachers feeling the most devalued. They were not offered hiring bonuses when they started out, but they are now facing an increased workload on top of taking on informal and unrecognized mentorship to support their uncertified colleagues.

But despite the challenges, many of the teachers interviewed said there’s nowhere else they’d rather be.

“Life is simplified,” said Shindy. “And the community is welcoming.”

The affordability in the region combined with the easy access to nature and convenience of short commutes are inviting. The community values and care that residents show for one another help them feel connected and build belonging.

“I know all my neighbours and colleagues, and these are good people,” said Ryan. “It’s the village that’s helping raise my kids.” •

BEYOND CHECKERS

How a Filipino game revolutionized

learning through math, science, and inclusion

By Nelli Kim Sia Acejo (she/her), Sharmaine Jacob Esplana (she/her), Brenda Mae Montera Galarpe (she/her), Ramoneth Alvarez Reyes (she/her), and Jennifer Englatera Taburnal (she/her), public school teachers, San Jose, California

“…

this game is proof that innovation in education doesn’t always come from high-tech tools— it can also come from creativity, culture, and a well-loved checkerboard.”

A CHECKERS-INSPIRED BOARD GAME used in our school years became one of the most memorable and effective tools for learning we encountered as students. More than just a game, it challenged us to think critically, solve problems, and engage with math and science in a way that was both enjoyable and meaningful.

Now as a group of five educators, we recognize the lasting impact this game had on our learning journeys—and we’ve continued to use and adapt it in our classrooms. Over time, we’ve enhanced it to include science-based elements and make it more accessible to students with diverse learning needs.

We are excited to share this game with fellow educators, especially those focused on STEM and inclusive education, to explore how a familiar board format can become a powerful catalyst for student engagement, understanding, and motivation.

WHAT IS DAMATH AND HOW IS IT PLAYED?

At first glance, damath looks like a game of checkers. But instead of plain chips, players use numbered ones. Instead of simply capturing an opponent’s piece, players must perform mathematical operations on the numbers involved in each move.

Materials needed

• damath board (an 8×8 checkerboard marked with math operation symbols: +, −, ×, ÷)

• two sets of 12 numbered chips (one per player)

• scoring sheet or calculator

• timer (optional for competitions).

Rules of the game

• Each player places 12 numbered chips on the dark squares of their side of the board.

• Players take turns moving diagonally, like in checkers.

• When a player captures a piece, they must compute a math operation: the operation is determined by the board square where the capture occurs.

• The result is added to their score.

• If a player gives an incorrect answer, they score zero for that move.

• The player with the highest score at the end of the game wins.

This format turns a recreational game into a fastpaced, interactive math exercise.

FROM GAME TO ACADEMIC COMPETITION

Over the years, damath evolved into a competitive academic sport in schools across the Philippines. Competitions are held during Math Month, science fairs, and other academic events. Tournaments are hosted within classrooms, between schools, and even across districts.

Matches are scored not only on game outcomes but also on accuracy in calculation and strategic thinking. It’s a fun way to challenge students and build enthusiasm for math.

We’ve seen students who were once shy in math class become team leaders, motivated to practise mental math and develop problem-solving strategies—all because of this game.

INTRODUCING SCIE-DAMATH: INTEGRATING S CIENCE

To expand the game’s learning potential, we introduced scie-damath—a version that integrates science concepts into gameplay. This version adds science prompts to key squares or includes science question cards drawn during the match.

Science integration options

• Landing on special squares may trigger a science question.

• Topics can include biology, chemistry, physics, earth science, or health.

• Correct answers grant extra points or bonuses.

• Incorrect answers might cost a turn or reduce points.

For example, a student might land on a square and be asked, “What is the process by which plants make food using sunlight?” Answering “photosynthesis” correctly could earn five bonus points. We can also change the numbers on the chips into chemical numbers of the table of elements.

This transforms the board into a cross-curricular battlefield, reinforcing both math and science learning through gamified repetition and real-time application.

MAKING IT INCLUSIVE

One of the most meaningful applications of damath and sciedamath is its ability to support students with special education needs. The game can be modified to fit various learning abilities and provide all students with a chance to engage, participate, and succeed.

Inclusive adaptations

• Colour-coded or tactile chips for students with visual or sensory sensitivities.

• Simplified numbers and operations for learners working at all levels.

• Paired play or team mode for students who need social or academic support.

• Visual aids and speech-to-text tools for students with communication needs.

Teachers can adapt the rules depending on student levels, and gameplay can be used to promote not only academic learning but also social-emotional skills like turn-taking, focus, and confidence.

CONCLUSION

Damath and scie-damath show us that even a simple game board can become a platform for powerful learning. From a Filipino classroom to potentially around the world, this game is proof that innovation in education doesn’t always come from high-tech tools—it can also come from creativity, culture, and a well-loved checkerboard.

We are proud to share damath and scie-damath and we hope it inspires both teachers and students to see STEM education and inclusive education not as a challenge, but as a game worth playing. •

CURIOSITY, CARE, AND COLLABORATION

Empowering school-based teams in an inclusive classroom

By Marcus Lau (he/him), teacher, Vancouver

AS I KICK OFF my second year as an inclusive education teacher, I find myself reflecting on the many moments—some joyful, some overwhelming, and all deeply meaningful—that shaped my previous year.

I vividly remember the excitement of stepping into my classroom for the first time in September 2024. After years of preparation, I finally had a classroom of my own. I was eager to meet my students, work alongside a team of support staff, and build a learning environment rooted in inclusion.

But alongside that excitement came a steep learning curve. I was stepping into a space filled with diversity, not only in the students I was supporting, but also in the adults I was collaborating with. I quickly realized that inclusive education is never a one-person job. It requires building relationships, navigating team dynamics, and creating a structure that supports everyone, including both students and staff.

THE ROLE OF THE SCHOOL-BASED TEAM IN INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

In our classroom, we supported 15 students. Each student brought a unique set of strengths, needs, and learning profiles. Alongside me, a team of seven support staff, some with over 10 years of experience and others just beginning their careers, helped make inclusion a reality every single day. We were also supported by a team of inclusive education professionals, including speech language pathologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nurses, administrators, and district resource staff, whose contributions were essential to our work.

Working in this kind of environment taught me that inclusive education is deeply relational. It is not just about programming or planning—it is about how we work together as adults. That was one of the most powerful lessons I learned this year: if we want to support students well, we must also support the team around them.

There were moments of challenge, including miscommunication, differing perspectives, and plans that did not always work out. But there were also moments of gratitude, connection, and shared growth. When we focused on team culture and relationships, things improved for everyone. Out of these experiences came three guiding values that helped sustain us through the year: curiosity, care, and collaboration.

THE THREE C s THAT GOT US THROUGH AS A TEAM

Curiosity

Curiosity helped us ask questions and respond with openness when situations felt uncertain, rather than jumping to conclusions. In a diverse, inclusive classroom, it is natural for team members to have different ideas about how to support students, structure the day, or respond to challenges. Instead of seeing those differences as barriers, we started viewing them as opportunities to understand each other better.

WHAT WE ASKED

• What might this colleague be noticing that the rest of us are not?

• What experiences or perspectives are shaping this concern or suggestion?

WHAT WE TRIED

• Holding daily 10–15 minute morning check-ins where all team members, including teachers, support staff, and specialists, could share updates, ask questions, or raise concerns.

• Shifting away from quick solutions and toward thoughtful follow-up questions like “What’s working for us?” and “What’s not?” or “How can we support each other?”

• Debriefing after challenging days using shared reflection questions such as “What went well?” and “What was hard?” and “What can we adjust as a team?”

• Using a shared classroom calendar to keep everyone informed about individualized education plan (IEP) meetings, specialist visits, family conferences, and schoolwide events.

These practices helped us create a more inclusive team culture, one where each person felt heard, respected, and part of the collective effort. When we led with curiosity, we deepened our understanding of one another and strengthened our capacity to support students together.

Care

In a classroom built on relationships, care must extend beyond students to include the adults who support them. As a schoolbased team, we often speak about the importance of creating safe and supportive spaces for learners. But we realized that those same principles must also apply to us.

We learned that when we care for each other, when we take time to check in, offer encouragement, and respond with empathy, we create a stronger, more sustainable foundation for inclusive education.

WHAT WE TRIED

• Using daily check-ins to make space for personal updates and acknowledging when someone was having a difficult morning, returning from illness, or simply needing extra support.

• Debriefing after big events or busy days, not only to review logistics but also to recognize emotional impact and offer space for processing together.

• Creating space for joy, encouragement, and small acts of appreciation to remind us we’re in this work together.

• Organizing occasional events, such as open house days to welcome other staff into our classroom or casual staff lunches to create informal opportunities for connection, celebration, and kindness.

Over time, we became more comfortable leaning on one another, not only for task-related help but also for genuine support. As our team culture of care grew, so did our capacity to be present and responsive with students. When adults feel safe, valued, and supported, they are better able to provide that same care to the learners we serve.

Collaboration

Inclusive education thrives on shared responsibility. We came to understand that collaboration is not just a helpful practice—it is essential. No one person can meet the full range of student needs alone. As a school-based team, we saw how working together with purpose and trust allowed us to create more consistent, responsive, and inclusive learning environments. Collaboration meant listening to each other, building routines as a team, and making space for all voices, especially those who work most closely with students throughout the day.

WHAT WE TRIED

• Co-developing “one-pagers” for each student that draw from IEPs, team input, and observations to highlight key strengths, strategies, and areas of need.

• Involving support staff in IEP meetings, when possible, or gathering their reflections in advance to ensure their perspectives were included and valued.

• Introducing a flexible two-week rotation system so team members could work with different students, expand their skills, and reduce role fatigue.

• Inviting specialists such as speech language pathologists, occupational therapists, and district resource teachers to lead short, practical learning sessions during team time.

We treated collaboration as a dynamic, evolving process shaped by feedback, flexibility, and shared reflection. As we made decisions together and adapted to challenges as a team, our sense of shared ownership grew stronger. The more we collaborated, the more connected and capable we felt and the more consistent our support for students became.

Conclusion

As I reflect on this first year, I do not look back on perfection. I look back on progress, connection, and growth.

There were days when things felt messy, when plans changed, and when I was not sure if we were getting it right. But what grounded me, what carried us through, were the people in the room: the students who showed up with so much heart; the support staff who brought their care, wisdom, and patience; the school team who reminded me I was not doing this alone.

I have come to realize that inclusive education is not only about meeting diverse student needs. It is also about how we care for, listen to, and learn from our colleagues. We are all part of this community. And when we support each other with curiosity, care, and collaboration, we model the kind of classroom and world we want students to grow up in.

This year also reminded me that inclusion works best as a shared responsibility. As outlined in Inclusive Education Services: A Manual of Policies, Procedures and Guidelines,1 school-based teams are collaborative problem-solving units that co -ordinate support and resources for students with diverse needs. Effective planning, instruction, and service delivery all rely on ongoing collaboration. This reminds us that we are not working alone but as part of a connected team with a shared purpose.

I still have a lot to learn. But if there is one thing the last year has taught me, it is that we are better together. And that shared purpose, supporting each other and growing together, is what makes this work so meaningful. •

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marcus Lau is a secondary inclusive education teacher with the Vancouver School Board, where he teaches a life skills program and supports diverse learners. He is also a sessional lecturer at the University of British Columbia, where he works with teacher candidates to develop inclusive and student-centred teaching practices. Marcus holds a Master of Education in Inclusive Education and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at UBC, with a research focus on inclusive education and universal design for learning in both K–12 and higher education settings.

PHOTO (L TO R): Kinjeel Patil (SSA), Agnes Lin (SSA), Keaton Smithers (SSA), Marcus Lau, (inclusive education teacher), Felipe Omena Raposo Da Camara (SSA), and Sanket Kale (SSA).

Photo provided by author.

1

WHAT CAN TEACHERS DO TO FEEL HOPEFUL?

By Dana Fraser, teacher, Sooke

HOPEFULNESS is not my natural orientation. It’s something that I’ve really struggled to find. For a long time, I didn’t know what to do to help myself feel more hopeful. Hopelessness always got the best of me. But hopelessness doesn’t feel good, and it doesn’t help us be better teachers and better people. Even after spending a few years researching hope as a doctoral student, I couldn’t figure out how to actually apply what I learned to create hope for myself. But I’m starting to figure it out—finally! In this narrative article, I share my experience of infusing more hope into my life.

FIND YOUR DEEPEST EXPERIENCE OF HOPE

Where do you feel the most hopeful? What are you doing? Who are you with? For me, I feel the most hopeful at Hurricane Ridge, when I’m on my annual wildlife photography trip to the Olympic Mountains in Washington State. These jagged basalt peaks, cloaked in ancient glaciers, soar straight out of the Pacific Ocean to a height of nearly 8,000 feet. The highest mountain in the range is Mt. Olympus. This isn’t, of course, Mt. Olympus, house of the gods, but to me these mountains have a magic of their own. Looking at them never gets old. Feeling the icy wind blowing off the glaciers, breathing in the mountain air, listening for marmot whistles, and following marmots, blacktailed deer, and blue grouse with my camera in hand as they scurry through the meadow plants, I do feel hope. It’s the most hopeful I ever feel in my life.

It feels like an incandescent kind of hope. Think of the old-fashioned incandescent lightbulb: warm, sustained, present, relaxed but energized. There’s no sharpness or harshness to the experience. I feel brave enough to start doing the things that scare me. The etymology of incandescence means to begin to glow from within. And in the mountains, hope truly does feel like that to me.

It is more of an embodied, somatic experience than anything else. I am more aware of my feelings than my thoughts. All I really think about is how I should stop talking myself out of doing things just because they’re scary. When I’m there, I think I could achieve anything (but in a humble way). This incandescent hope, ephemeral and transcendent, fills my whole being. It is a reprieve from the everyday phenomena like stress and worry that we all experience.

“If you can recognize moments when you feel the most well and happy, try to think about what individual components make up that experience. This will help you figure out your alignment.”

FIND Y OUR ALIGNMENT

It might sound funny, but my two biggest goals in life were to get a doctorate and learn how to ride a horse. I love the cowboy aesthetic. I love the prairie. And I know that having hobbies and having things to look forward to helps people stay hopeful. While my deepest experience of hope is photographing wildlife at Hurricane Ridge, I can’t be there all the time. So, what can I do on a regular basis in my day-to-day life to stay hopeful? I decided to take horse-riding lessons three times a week.

Riding horses has been great for fostering hopefulness because it gives me a break from everything negative. There is so much to think about when you’re riding. You have to pay attention to the horse, to your riding position, to your surroundings, and to your instructor. There’s no room in my brain to dwell on my problems or anything negative. I’m fully absorbed in the moment. It really is therapeutic. And it gives me meaningful goals to work toward.

One of the things I learned from riding is the importance of having good alignment. When we ride, we’re supposed to have our body aligned so that our ear, shoulder, hip, and heel are on top of each other in a straight line. If we’re out of alignment, and if we are carrying too much tension, we will bounce in the saddle, which is not comfortable for the horse or the rider. Bouncing indicates that things are going wrong.

The concept of alignment in horseback riding made me think about how to align other areas of my life to nurture hopefulness. My favourite things are being outdoors, interacting with animals, exercising, and having creative projects to work on. And if I had to add a fifth thing, I’d say it’s learning things. Things that make me feel the most hopeful follow this alignment. It’s things like hiking in the forest near my house, kayaking with the turtles and herons, or working on writing a children’s book. These are things I can do on a daily basis throughout the year to help myself stay hopeful. They’re all part of keeping my life in good alignment.

WHAT PRACTICAL STEPS CAN TEACHERS TAKE TO FEEL M ORE HOPEFUL?

Hope won’t help us if we think of it too philosophically—it has to be put into practice. I do understand the pragmatic reality of teachers’ lives. I’m a busy teacher too, but I know I can’t be my best, happiest, and healthiest self unless I make conscious choices that nurture my hope. My mental health needs are just as important as my work needs, and they need to be integrated.

As a teacher who spent a long time studying hope in an academic setting, and even longer trying to embed hope into my own life, this is my advice to teachers on how to be hopeful: if you can, invest time in self-reflection and self-discovery. Try to pay attention to where you are and what you’re doing when you feel your best. Hopefulness is intertwined with our wellbeing and happiness. If you can recognize moments when you feel the most well and happy, try to think about what individual components make up that experience. This will help you figure out your alignment.

Once you identify what your personal hope building blocks are, build them into your daily schedule—and treat them with the same importance as your work and family responsibilities. So, if you need to take the kids to a ballet lesson after school, instead of using that 50 minutes to rush to the grocery store, use the time to walk around the block, talk to someone you love on the phone, or knit, if that does the therapeutic job for you. Use your knowledge of your alignment to set meaningful goals that you can think about and work toward every day. See if you can find a hobby that is so fun and absorbing you can’t think about your problems at the same time. This way you are building mental breaks into your life. And keep a hope journal. That’s a new practice I started this year on the first day of school. Every day I write down what I did to nurture my hopefulness. That might be going to lunch with a friend, spending time outdoors, or working on a creative project. And at the end of the year, you can review your journal and see what worked to create hopefulness and what didn’t. Think about hope every day, and talk about hope in your schools.

There will always be temptations to feel hopeless. The world is imperfect and life can be really hard. Being hopeful might feel like swimming upstream, but we need hope to keep our heads above water. The purpose of this narrative article is to share an account of how a teacher who isn’t naturally hopeful can find hope. It’s hard to put such a personally meaningful experience into words (and we don’t have a word for everything) but I hope other teachers can think about where they are and what they are doing when they feel hopeful, and try to spend more time doing the things that make them feel that way. •

CARING FOR THE LAND WITH INVASIVE SPECIES EDUCATION

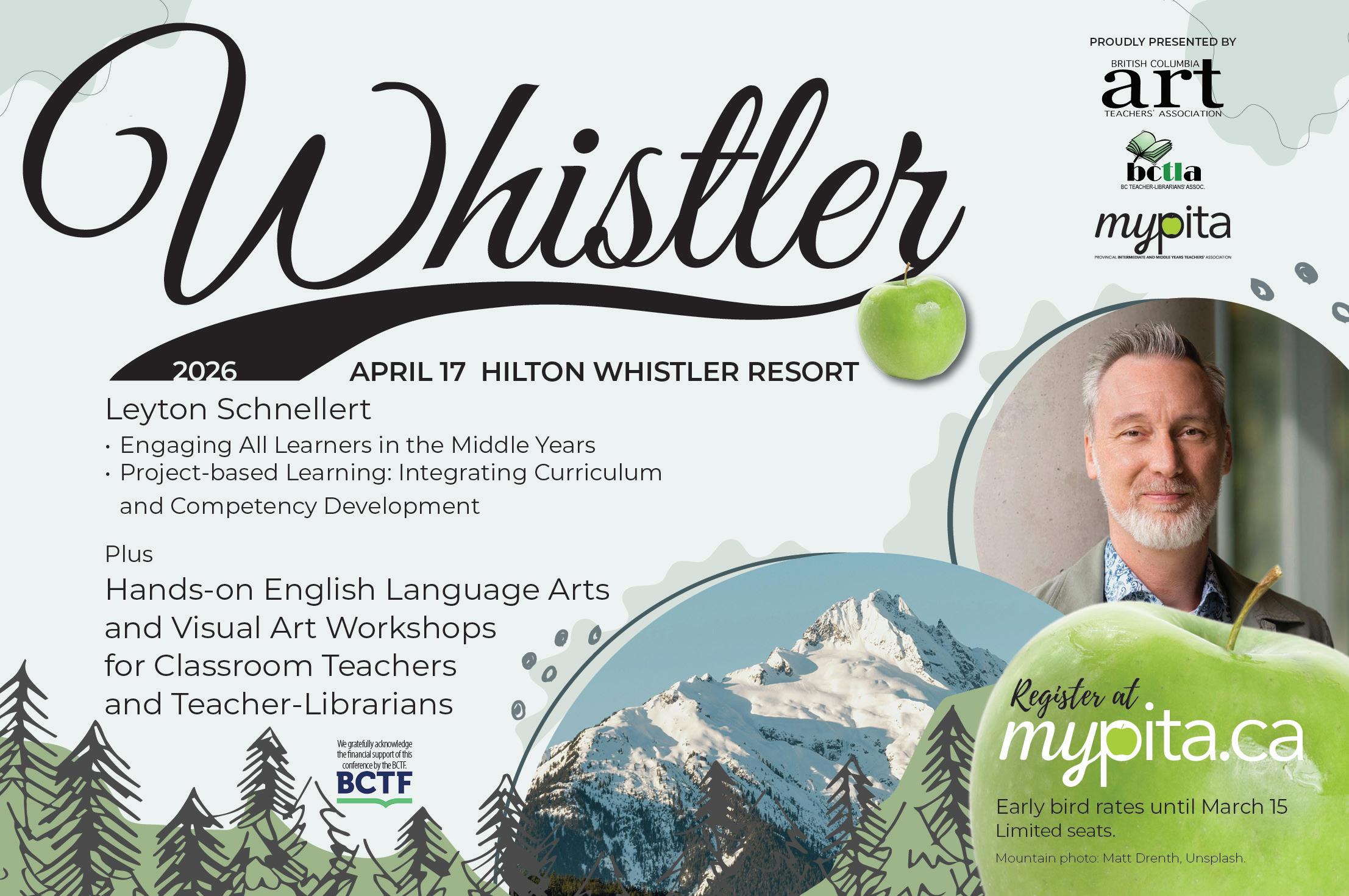

A collaboration between ISCBC and myPITA

The Invasive Species Council of British Columbia (ISCBC) is a dynamic, action-oriented organization, helping concerned stakeholders work together to stop the spread of invasive species in BC. The Provincial Intermediate and Middle Years Teachers’ Association (myPITA) provided the ISCBC with a grant to create cross-curricular, science-focused lessons with connections to First Peoples perspectives. The grant was used to develop two resource packages: We Care for the Land and Prevent the Spread of Invasive Species for Grades 4–6 and Student Land Stewards in Action for Grades 7–9. The lessons support learning about biodiversity in BC, the issue of invasive species, and ways that students can protect and enhance native species and habitats in our communities. The learning activities may be delivered individually, in any order, or sequentially. Detailed lesson plans for the activities outlined here can be found by scanning the myPITA QR code (below) or at mypita.ca/caring-for-the-land. Find more curriculum-based teaching resources by scanning the ISCBC QR code (below) or at bcinvasives.ca/for-youth/foreducators

WE

CARE FOR THE LAND AND PREVENT THE SPREAD OF INVASIVE SPECIES GRADES 4–6

Building Connections to the Land—Activities 1–3

Activities that connect students to nature through sensory awareness and outdoor learning routines.

Activity 1: Notice Nature with All Your Senses

Activity 2: Sit Spots

Activity 3: Nature Journaling (see right for detailed lesson plan)

We’re All Connected—Activities 4–5

Students gain a greater awareness of local biodiversity, how people are part of the web of life, and how our actions can have positive or negative effects on the environment.

Activity 4: Ecosystems Web

Activity 5: Biodiversity Scavenger Hunts

The Problem with Invasive Species—Activities 6–7

Activities to introduce the issue of invasive species in BC, their impacts, and how we can make a difference.

Activity 6: Why We Care about Invasive Species

Activity 7: Become Land Stewards! Plan a Weed Pull

Give Back to the Land—Activities 8–10

Students make a positive difference to the environment by sharing their learning about invasive species, developing plant identification skills, and taking part in a weed pull.

Activity 8: Spread Awareness, Not Invasives

Activity 9: Plant ID and Schoolyard Stewardship

Activity 10: Weed Pull

LAND STEWARDS IN ACTION GRADES 7–9

Activity 1: Ecosystem Postcards

Students learn about the biodiversity of BC, including characteristics of five main ecosystems, common native species found there, and some invasive species that threaten them. Students share their learning by creating a postcard that depicts an ecosystem in BC with artwork and text.

Activity 2: Invasive Species Trivia Challenge Relay

Students learn about invasive species, their impacts, and how to prevent their spread via an “Invasive Species 101” slideshow and video. Then their knowledge is tested in a team challenge relay game.

Activity 3: Superspreader Point-of-View (POV)

Students research an invasive species and present their findings in creative social media posts from that species’ POV.

Activity 4: Indigenous Knowledge and Invasive Species Impacts

Students will explore examples of traditional ecological knowledge and how invasive species threaten species important to Indigenous traditions and livelihoods. After researching a traditional plant, they may also create a connections card, which can enhance outdoor walks.

Activity 5: Native Plant Garden Planning

Students envision and create a plan to transform an area of the schoolyard or nearby green space into a vibrant native plant garden that supports biodiversity and is free from invasive plants. Actually planting the garden is not required.

Activity 6: Observe and Report! Contribute to Community Science

Students contribute to community science and the protection of biodiversity by observing nature and reporting invasive species using free apps or computer-based programs.

Activity 7: Become Land Stewards! Plan a Weed Pull

This lesson includes tips on organizing an event with students to remove invasive species and prepare them for the experience.

LESSON PLAN

CONNECTING PLACE WITH NATURE JOURNALING

This is Activity 3 from the unit We Care for the Land and Prevent the Spread of Invasive Species (see left for complete list of unit activities). Access the entire unit by scanning the myPITA QR code on page 30 Connecting to place starts by slowing down and noticing the natural world. Nature journaling fosters curiosity, promotes self-regulation, deepens attention, sparks inquiry, and builds a connection to nature and community. In this activity, students hone their observation and communication skills by using sketches, words, and numbers to record information about a natural object. Then they challenge a partner to find the “nature mystery” based on their journal entry. No artistic skills are required!

This activity is inspired by the work of John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren from their book How to Teach Nature Journaling

Curriculum connections