Course Directors Bobby Barrera, Adam Kobs, Ashley Morgan, & Gary Trichter

Location Menger Hotel 204 Alamo Plaza, San Antonio, TX 78205

Course Directors Bobby Barrera, Adam Kobs, Ashley Morgan, & Gary Trichter

Course Directors Bobby Barrera, Adam Kobs, Ashley Morgan, & Gary Trichter

Location Menger Hotel 204 Alamo Plaza, San Antonio, TX 78205

Course Directors Bobby Barrera, Adam Kobs, Ashley Morgan, & Gary Trichter

Thursday, November 2, 2023

speakers topic

Stephanie Stevens Probation Conditions Misdemeanor and Felony

Dr. Kevin Schug Forensic Blog Articles

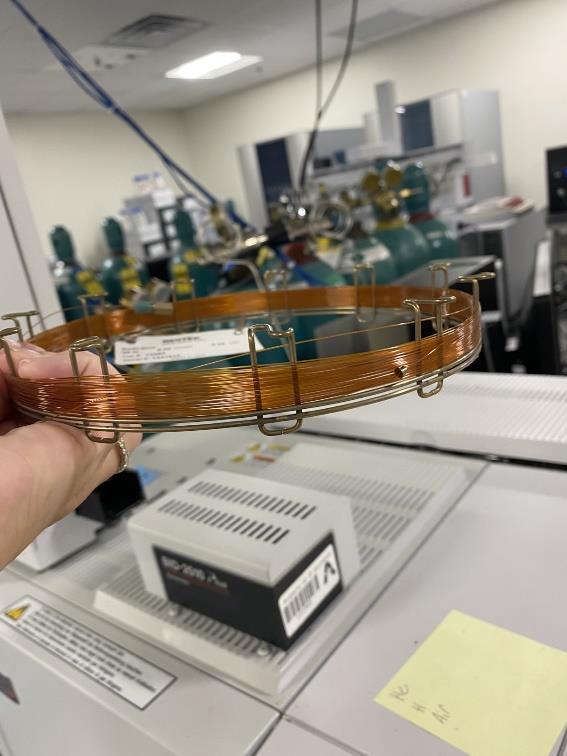

Ashley Morgan Gas Chromatography – The Lawyer’s Roadmap to Success

Jarrod Smith & Brad Vinson Breath Testing – 2023 Update

Michelle Behan Boats to Build: Sealing the Deal in Closing Arguments

Friday, November 3, 2023

speakers topic

Adam Kobs Using the ALR Hearing to Prepare to Cross the Arresting Officer

Lisa Martin Using the Defense Expert to Undo the SFSTs

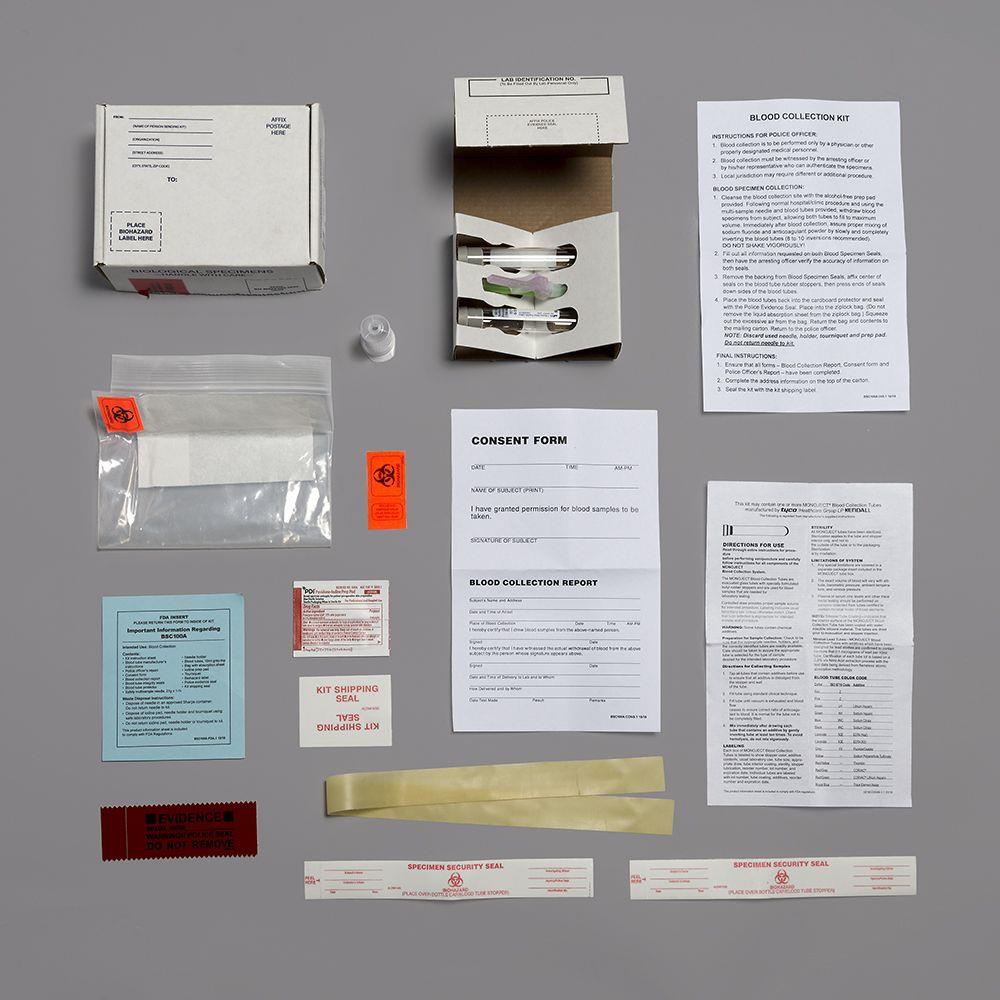

Gary Trichter Blood Search Warrant Affidavits and Oaths: Avoiding Ineffectiveness!

Betty Blackwell ETHICS – Dos and Don’ts with Clients

George Scharmen Collateral Consequences for Driving While Intoxicated

San Antonio, Texas

Speaker: Stephanie Stevens

2507 NW 36th St

San Antonio, TX 78228-3918

210.431.5710 phone

210.431.5750 fax

sstevens@stmarytx.edu email

Co-Author: Betty Blackwell

Law Office of Betty Blackwell

1306 Nueces St Austin, TX 78701

512.479.0149 Phone

512.320.8743 Fax

bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com Email

www.bettyblackwell.com website

19TH ANNUAL

STUART KINARD

ADVANCED DWI SEMINAR

NOVEMBER 2-3, 2023

DWI CONDITIONS OF PROBATION

BY

STEPHANIE L. STEVENS ATTORNEY AT LAW

BOARD CERTIFIED CRIMINAL LAW

2507 NW 36TH STREET SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS 78228 210-431-5710

sstevens@stmarytx.edu AND BETTY BLACKWELL ATTORNEY AT LAW

BOARD CERTIFIED CRIMINAL LAW

1306 NUECES STREET AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 512-479-0149

bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com

DWI 1st offense is a Class B misdemeanor which if probated does not result any driver’s license suspension, as long as the defendant completes the DWI education course within 6 months of being placed on probation. Article 42A.406 CCP. Starting 9/1/2019 the defendant arrested on or after that date is eligible for deferred adjudication with an interlock device as long as the defendant did not have a commercial driver’s license. The Transportation Code only refers to “convictions” and “final convictions” under Article 49 being subject to driver’s licenses suspension, so that a deferred adjudication should not result in any additional license suspension.

If the sentence is probation, on a 1st offense, the trial court is without authority to order a corresponding license suspension as long as the condition of probation includes the required alcohol education course. Love v. State, 702 S.W.2d 319 (Tex. App. Austin 1986). However, beware of Burg v. State, 592 S.W.3d 444 (Tex. Crim. App. 2020) which held this issue could not be raised for the 1st time on appeal as an illegal sentence. The Court held that the license suspension is not part of the sentence or probation terms, and thus did not affect the legality of the sentence. The objection to suspending the license of a 1st time probated DWI, with the education course required, must be raised at the trial court to appeal any adverse decision.

If the sentence is a jail sentence, the license is automatically suspended under Transportation Code §521.341 from 90 days up to one year per Transportation Code §521.344. The code states that the court shall grant the defendant credit against the suspension for the Administrative License Revocation suspension for failure of a breath or blood test or refusal to provide a specimen [referred to as ALR credit] against this mandatory suspension and the suspension may begin no later than the 30th day after the conviction as set by the court. See §521.344(c) Transportation Code for credit for refusal ALR suspension and §524.023(b)Transportation Code for credit for failure ALR suspension. Credit can only be applied to a 1st offense

DWI. Even if the DWI 2nd is reduced to a DWI-1st conviction, DPS will not honor a request for credit for the ALR suspension as the Transportation Code states the credit cannot be extended to a person who has been previously convicted for an offense under §49.04. DPS has in the past interpreted “has been convicted” to exclude cases in which the person received deferred adjudication. Thus, it remains to be seen if a person has completed deferred adjudication for a DWI case and is subsequently convicted in a subsequent DWI case, whether the court can award credit for the ALR suspension that DPS will honor.

DWI with .15 or higher is a Class A misdemeanor with no mandatory jail time, but if probation is granted, an ignition interlock device is required for half the term of probation. §521.344 (d)(2) of the Transportation Code provides that DPS may not suspend the driver’s license for someone placed on community supervision who is required to not operate a motor vehicle unless the vehicle is equipped with an interlock device. There is no driver’s license suspension as long as the person receives community supervision and is required to complete an education course, within 6 months of being placed on probation.

DWI-1st offense under 21 years of age is either a Class B misdemeanor or a Class A misdemeanor if the alcohol concentration is .15 or higher. If the person is younger than 21 years of age at the time of the offense, the judge who places the defendant on community supervision must suspend the driver’s license for 90 days beginning on the date of the community supervision. Article 42A.407 (f)C.C.P. The judge must order as a condition of community supervision, that the defendant not operate any motor vehicle unless it is equipped with an ignition interlock device. Article 42A.408(e)C.C.P. If the sentence is a jail sentence and not community supervision, then the license suspension is for one year. See §521. 343 Transportation Code. There is no ALR credit available to someone under 21 years of age at the time of the DWI offense. §521. 344 (c)(2) Transportation Code.

DWI-2nd offense’s range of punishment is from 30 days up to one year in jail and/or up to a $4000.00 fine. The jail time can be probated, but 42A requires at least 72 hours of continuous confinement. Article 42A.401(a)(1) C.C.P. The jail time on a 2nd offense probation is up to a maximum of 30 days as a condition of probation. The license suspension is from 180 days up to two years. However if the prior DWI offense date is within 5 years of the conviction date, then the minimum license suspension

is one year and the minimum jail time as a condition of probation is 5 days. See Article 49.09(h) Penal Code. The trial court does not have to give the defendant credit for time already served against the mandatory 72 hours of confinement. Martinez v. State, 427 S.W.3d 496 (Tex. App. San Antonio 2014)

An open plea could not be set aside based on a claim of involuntariness, even though the defendant believed that she would not receive jail time. She had pled unnegotiated to a DWI-2nd offense, which the appellate court noted required jail time as a condition of probation. Cortez v. State, 971 S.W2d 100 (Tex. App. Ft Worth 1998) This analysis would be the same, if the defendant pled guilty believing the driver’s license would not be suspended, but was notified by DPS that it was in fact suspended due to the conviction.

The driver’s license suspension for a 2nd offense is mandatory and no ALR credit can be given toward this suspension. Article 42A.407(b) C.C.P. starts out with the words “Notwithstanding Section 521.344(d-i), Transportation Code” which means that the Transportation Code provisions about not suspending the license if an educational course are required as a condition of probation, do not apply to convictions for 2nd and 3rd DWI offenses. The Texas Department of Public Safety will impose a one year suspension if they receive notice the defendant is required to attend a subsequent educational program, even if the charge is reduced to a DWI-1st offense, if the driving record reflects that the defendant has previously been required to attend an educational program, or it has been waived. See Article 42A.407 C.C.P.

Felony DWI: The driver’s license suspension is from 180 days up to two years, with no credit for any ALR suspension. If the prior conviction is within 5 years, under Section 49.09(h), the driver’s license suspension must be for a minimum of one year, up to two years. Probation including an interlock device, and required educational course will not prevent DPS from suspending the license, if the trial court fails to impose a suspension. See Article 42A.407(c)C.C.P.

Driving While Intoxicated with child passenger younger than 15 year of age, is a state jail felony. Section 521.344 of the Transportation Code, states that anyone convicted under §49.045 is subject to a driver’s license suspension of not less than 90 days or more than one year. However, §521.344 (d) provides that DPS may not suspend the license if the person is required to complete an educational program during a period of probation.

Article 42A.407 C.C.P. and §521.344 (d)(1) provide that the defendant may request that the jury make a recommendation about whether the driver’s license should be suspended, if the jury recommends community supervision. If the jury recommends against a suspension, none shall be entered by DPS.

Intoxication assault that does not involve injury to a specified person listed in §49.09(b-1) Penal Code, [firefighter, EMS, police officer or judge], it is a 3rd degree felony requiring a minimum of 30 days in jail, if the sentence is probated. If the person caused another to suffer a traumatic brain injury that results in a persistent vegetative state, it is a 2nd degree felony under §49.09(b4) Penal Code. If a jury recommends community supervision, it may also recommend that the driver’s license not be suspended. Otherwise, Section 521.344 Transportation Code provides that driver’s license can be suspended from 90 days up to one year.

Intoxication Manslaughter that does not involve the death of a specified person in §49.09(b-1) is a 2nd degree felony requiring a minimum of 120 days of confinement, if the sentence is probated. It is a 1st degree felony if the victim is a firefighter, EMS, peace officer or judge. If a jury recommends community supervision, they may also recommend that the driver’s license not be suspended. Section 521.344 Transportation Code provides that the license may be suspended by the Court for not less than 180 days or more than two years.

Effective September 1, 2019 Article 42A.102(b) allows deferred adjudication for 1st DWI & BWI occuring on or after 9/1/2019 unless the defendant held a commerical driver’s license, or had an alcohol concentration of 0.15 or more. The court shall require as a condition of the community supervision that the defendant have an ignition interlock device installed and that the defendant not drive a motor vehicle without that device. The judge may waive the interlock requirement, if based on a controlled substance and alcohol evaluation of the defendant, the judge determines and enters in the record that the interlock is not necessary for the safety of the community.

Article 49.09(g) Penal Code is amended to provide that for the purposes of this section, deferred adjudication can be used for enhancement for a subsequent DWI charge.

The issue is whether DPS will interpret a deferred adjudication as a conviction for driver’s license issues. Under the Transportation Code and Code of Criminal Procedure, driver’s licenses are only suspended for those under 21 upon conviction of a DWI. If deferred adjudication is not a conviction for those sections of the law, then DPS could honor a court order not to suspend the license of a person under 21. A phone call to DPS Enforcement and Compliance division resulted in a manager stating that the DIC-17 is not sent to DPS on any deferred adjudication, and this was confirmed with our local county clerk’s office so that no license suspension should result.

Deferred adjudication and the use of prior probations in DWI cases

Beginning in 1979, the Legislature amended Article 42.12 CCP, now Section 42A.102, to delineate that DWI offenses were not eligible for deferred adjudication. The Legislature, effective September 1, 1997, created a new class C offense of Driving with a Detectable Amount of Alcohol by one who was under 21 years of age. DUI minor cases are eligible for deferred disposition which has caused confusion by many with deferred adjudication.

Starting January 1, 1984, a sentence on a DWI was considered a final conviction for enhancement purposes regardless of whether it was probated or not. See §49.09(d) Penal Code. Though this section refers to a date of September 1, 1994, case law makes it clear that the prior law which allows probation to be used for enhancement, is still in effect for all offenses committed after January 1, 1984. Ex parte Serrato, 3 S.W.3d 41 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). The legislature eliminated the remoteness rule, effective September 1, 2005. Previously, DWI convictions from more than 10 years prior to the new arrest date could not be used for enhancement purposes. The date of the probation is important because probated sentences prior to January 1, 1984, including prior deferred adjudications, can not be used for enhancement purposes. State v. Wilson, 324 S.W.3d 595 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) The finality of probation did not originally apply to intoxication assault and manslaughter cases. Probation in those cases became final convictions on or after September 1, 1994. Ex parte Roemer, 215 S.W.3d 887 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007). Use of a completed deferred adjudication on an offense committed before 1979, for enhancement would violate the Ex Post Facto provisions of the Texas Constitution. See Scott v. State, 55 S.W.3d 593 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001)

The 2005 DWI enhancement provision removing all time limitations on the use of prior DWI convictions was held to not violate the prohibition against ex post facto laws. Englebrecht v. State, 294 S.W.3d 864 (Tex. App. Beaumont 2009) However, both the conviction date and the offense date must occur after January 1, 1984, in order for the conviction to be used for enhancement. Nixon v. State, 153 S.W.3d 550 (Tex. App. Amarillo 2004).

The issue that has arisen involves a probation that has been completed, and whether a completed felony probation on a DWI can be used to raise the next felony DWI from a 3 rd degree felony to a 2nd degree felony. Article 49.09(d) treats probation as a final conviction only “for purposes of this section”. Chapter 12 Penal Code, sets out the enhancements provision of a 3rd degree felony based on the defendant having been finally convicted of a felony other than a state jail felony. Section 49.09(g) states that a conviction can be used for enhancement under Chapter 49 of the Penal Code or Chapter 12 of the Penal Code, but not both. Rivera v. State, 957 S.W.2d 636 (Tex. App.Corpus Christi 1997).

The prior completed felony probation will prohibit the person from receiving community supervision on a subsequent felony DWI conviction as the prior is a conviction which makes the defendant ineligible for a subsequent probation from a jury.

The Court of Criminal Appeals has held that even in cases where the trial court has granted judicial clemency, the defendant is still ineligible for probation from a jury. Yazdchi v. State, 428 S.W.3d 831 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014)

In 2019, Chapter 708, Transportation Code was repealed. As of September 1, 2019, DWI surcharges are no longer allowed. Additionally, DPS shall reinstate any driver’s license that it suspended under Section 708.152, if the only reason the driver’s license is suspended is failure to pay a surcharge under chapter 708.

However, a new Chapter 709 was created to add a new “fine” to convictions for DWI. On a final conviction the person shall pay a fine of:

(1) $3000.00 for the first conviction within a 36 month period;

(2) $4500 for a second or subsequent conviction within a 36 month period; and

(3) $6000.00 for a first or subsequent conviction if it is shown on the trial of the offense that an analysis of a specimen of the person’s blood, breath, or urine showed an alcohol concentration level of 0.15 or more at the time the analysis was performed.

If the court makes a finding that the person is indigent, the court shall waive all fines and costs imposed under this section. This money is paid to the county and they may retain four percent of the money collected. Failure to pay does not result in the suspension of the driver’s license.

Texas District and Count Attorney’s Association has published in their 2019 Legislative Update their opinion that this new “fine” only applies to DWI jail sentences because the legislation does not define final conviction to include probated sentences as did the previous Section 708 of the Transportation Code. It would not apply to any of the new deferred adjudication sentences. They also stated that to avoid ex post facto and retroactive law prohibitions of the U.S. and Texas constitutions, the new “fine” will only apply to offenses after September 1st, 2019.

Credit for an ALR suspension can only be applied to suspension for convictions of 1st offense DWI cases, over 21 year of age at the time of the offense. It is possible to be sentenced to 3 days in jail with a 90 day license suspension with credit for the 90 day license suspension imposed at the Administration License Revocation and court costs. The prosecutor must agree that the suspension be set at 90 days, as it is up to a maximum of one year suspension, but the Transportation Code mandates credit for the ALR suspension. The new “fine” will still be assessed unless the person is indigent and the court makes that finding.

Many defendants consider the possibility of taking a final conviction (jail sentence) on misdemeanor DWI cases to avoid all the conditions of probation and the interlock device. However, if the license is suspended for potentially up to two years, the defendant will still be required to obtain the interlock device if they apply for an occupational license under §521.246 of the Transportation Code.

§521.242 Transportation Code provides that an application for an occupational license must be filed in the court in which the person was convicted if that conviction automatically suspended their driver’s license.

Over the years the legislature would add restrictions to this section, including that the person could not have been issued more than one occupational license in the 10 years preceding the petition, after a conviction. The state was entitled to receive notice of the application if the license was suspended for an offense under Sections 49.04-49.08 or Section 19.05 of the Penal Code or Section 521.342 Transportation Code. §521.245 of the Transportation Code was added to require alcohol counseling for an ALR suspension.

This section requires a showing of essential need and §521.248 Transportation Code restricts the driving to 4 hours in a 24 hour period or 12 hours if a necessity is shown and it requires the court to set the days of the week and the areas or routes of travel permitted and the reasons for the driving.

In 2001 the Legislature added §521.251to the Transportation Code to provide for blackout periods where a person was ineligible to apply for an occupational license based on their history of suspensions, the longest of which was a one year prohibition based on a subsequent conviction suspension within 5 years.

Finally, the Legislature realized that the better practice was to allow individuals to apply for and receive an occupational license, but to require the installation of an interlock device. Starting in 2015, the Legislature added §521.246 to the Transportation Code to require the installation of an ignition interlock device for an occupational license based on a conviction for an offense under section 49-04-49.0, Penal Code. §521.246(e) allows the person to drive a work vehicle without an interlock device but with some strict requirements, including notifying the employer.

Most importantly, the Legislature removed any requirement of showing an essential need to drive (§521.244(e) Transportation Code), and they removed any restriction for time of travel, reasons for travel, or location of travel, if the occupational license restricts their driving to a motor vehicle equipped with an ignition interlock device (§521.248 (d) Transportation Code).§521.251 of the Transportation Code was amended to add section (d1) which removed the blackout periods for occupational licenses based on the previous suspension for an “alcohol related contact”, if the person submits proof that they have an ignition interlock device installed on each motor vehicle owned or operated by the person. The person must still obtain SR-22 insurance.

Another improvement to the occupational license law, was permitting the justice of the peace to issue occupational licenses for non-DWI conviction suspensions. This means that all ALR suspensions can apply in JP court where the court costs are a fraction of the costs in county and district court.

All second and subsequent DWI offenses are required to obtain an ignition interlock device as a condition of community supervision for at least half the term of probation. A condition of probation shall require that the defendant not operate any motor vehicle that is not equipped with the device. A DWI with a finding of .15 or higher at trial of the offense, is also required to obtain the ignition interlock device. Article 42A.408 (c)(1)Code of Criminal Procedure. Ignition interlock devices can be avoided, if the prior conviction was more than 10 years before the instant offense and the person has not been convicted of a DWI within the 10 year period. However, Article 42A.408(b) of the Code of Criminal Procedure states that a judge “may” order the device on any DWI probated sentence.

The ignition interlock requirement is not required, if the employer has been notified of the driving restriction and proof of the notification is with the vehicle. The employment exemption does not apply to vehicles owned by a the defendant’s personal business.

Article 49.09(h) Penal Code mandates the court to enter an order requiring the ignition interlock device on all cases of conviction of second or subsequent offense within five years of the date on which the most recent offense was committed regardless of whether the person is granted community supervision. This section further requires the restriction to continue until the first anniversary of the ending date of the license suspension under Section 521.344, Transportation Code. The Court retains jurisdiction over the defendant until the device is no longer required, failure to comply is punishable by contempt, and Article 49.09(h) Penal Code controls over Article 42A, Code of Criminal Procedure.

Scram:

Mathis v. State, 424 S.W.3d 89 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014) held that the trial court had the authority to order that the defendant be fitted with a secure continuous remote alcohol monitor (SCRAM) device. This is an ankle monitor that detects consumption of alcohol. The case was remanded to determine whether the defendant would be able to pay, without undue hardship, for the device. The trial court must consider the defendant’s financial ability in deciding whether to order the defendant to pay for the device. But the case makes it clear that the trial court had the authority to order the use of the monitor, particularly if the county paid for it.

Monitors as a condition of bond:

Article 17.441(a) C.C.P. states that a defendant charged with a subsequent offense under Section 49.04-49.08, Penal Code shall be required to install and ignition interlock device and not operate a vehicle unless it is equipped with the device. The magistrate may not require the installation, if they find that to require the device would not be in the best interest of justice. Many counties require the defendant to obtain a portable alcohol monitor or a Scram ankle monitor, if they are not driving. It is, therefore, a condition of bond to not consume alcohol at all during the pendency of the case.

Costs of the police responding to an accident which resulted in a DWI conviction can be included in the court costs. On all DWI cases there is an insurance surcharge for 3 years. See Texas Insurance Code 5.03-1 Section 1. Salinas v. State, 523 S.W.3d 103 (Tex. Crim. App. 2017) held the statute allowing court costs in a criminal case for rehabilitation and abused children counseling, violated the separation of powers prohibition of the Texas Constitution, and held that the application of this would be prospective only. Thus began an attack on numerous other court costs attached to convictions. Penright v. State, 537 S.W.3d 916 (Tex. Crim. App. 2017) applied Salinas, as the case was on appeal when Salinas was decided. In Casas v. State, 524 S.W.3d 921 (Tex. App. Ft. Worth 2017), the court that in DWI cases, the $100.00 court cost assessed for the emergency services was facially unconstitutional as it was a tax since it did not direct that the funds be used for a legitimate criminal justice purpose. The court may collect fees if the statute provides that the fees are to be expended for a legitimate criminal justice purpose.

2021 Legislation:

Article 42A.655 of the Code of Criminal Procedure was amended by the 87th Legislature, effective September 1, 2021, to change the way the court considers a defendant’s ability to pay before ordering payments as a condition of probation. Restitution is excluded for any consideration of ability to pay. Monthly probation fees cannot be reduced or waived for indigent clients unless all additional payments owed are waived first and the court determines the defendant still cannot pay. The Defendant can periodically ask the court to reduce or waive or impose alternative means of satisfying payments and the court on its own motion or at the prosecutor’s request may reconsider a reduction or waiver of a payment after providing written notice to the defendant and an opportunity to be heard.

Community service is generally required as a condition of community supervision. There are possible waivers for this requirement if:

1) The defendant is physically or mentally incapable of participating in the project;

2) Participating in the project will cause a hardship to the defendant or the defendant’s dependents;

3) The defendant is to be confined in a substance abuse felony punishment facility as a condition of community supervision; or

4) There is other good cause shown.

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. 42A.304

Community service cannot exceed the following:

1000 hours for a 1st degree felony

800 hours for a 2nd degree felony

600 hours for a 3rd degree felony

400 hours for a state jail felony

200 hours for a class A misdemeanor

100 hours for a class B misdemeanor.

Alternatively, a judge can order a defendant to make a specified donation to a nonprofit food bank or other charitable organization, including ones designed to help veterans.

CCP Art. 42A.402 requires a drug or alcohol dependence evaluation for anyone granted community supervision under Chapter 49 of the Penal Code. The purpose of the evaluation is to prescribe and carry out necessary drug or alcohol rehabilitation. The defendant can be ordered to pay for any rehabilitation ordered, but the judge can credit this cost against the fine imposed. To determine whether the defendant can afford rehabilitation, the court can consider whether the defendant has insurance coverage for such rehabilitation. Furthermore, a judge can, based on the evaluation, require a defendant to see a doctor to determine whether the defendant would benefit from medication-assisted treatment.

Within the first 180 days of probation, the defendant is required to attend an educational program designed to rehabilitate persons who have driven intoxicated. This course allows a defendant to keep his/her driver’s license. If a jury recommends that the license be suspended, then the defendant does not have to take this course. For good cause, the judge may consider an extension of time to complete the course.

Pursuant to CCP Art. 42A.701, a defendant on community supervision for DWI cannot terminate the probation early. However, the defendant may be allowed to transition to “non-reporting” status.

Other conditions for DWI probation may include donations to M.A.D.D.; Victim Impact Panel, no alcohol usage; monthly reporting; permit home and work inspections by the probation officer; permission required to leave the county or state; and submit to rand drug tests. CCP Art. 42A.301.

San Antonio, Texas

Speaker:

Kevin A. Schug, Ph. D.

Professor, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, The University of Texas Arlington Partner, Medusa Analytical, LLC 817.272.3541 phone kschug@uta.edu email

Schug, K.A.; Hildenbrand, Z.L. The LCGC Blog: Forensics Laboratories Underassess Uncertainty in Blood Alcohol Determinations. The LCGC Blog. May 2, 2023.

https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/the-lcgc-blog-forensics-laboratoriesunderassess-uncertainty-in-blood-alcohol-determinations

Over the last two years, our consulting firm has had the opportunity to review and assess more than 150 litigation discovery packets from a multitude of forensic testing laboratories. We have written previously lamenting the overall lack of sufficient method validation and quality control in the cases that we have reviewed, the majority of which have been for blood alcohol determinations. 1, 2, 3

We have argued these deficiencies and others in the courtroom in several instances. It is disheartening to see forensics analysts from crime labs cling to outdated standard operating procedures, which do not conform to consensus standards propagated by nationally-recognized organizations, such as the American Academy of Forensic Science. 4 , 5 As analytical chemists who are regularly involved in the development of new methods, be it for environmental, pharmaceutical, or forensic science, we rely on consensus standards to define the steps and procedures needed to prove that a method and the measurements made are reliable. When these steps are not followed, the method and measurements may be subject to uncertainties and inaccuracies that have not been properly assessed.

In the scientific publication process, studies lacking appropriate validation and quality control are regularly rejected during peer review. Similarly, in forensics, measurements that have not been supported by widely accepted criteria for validation and quality control should not be relied upon in litigation, especially considering that someone’s civil liberties may be at stake. The uncertainty (or error) associated with a reported value is an important criterion to assess the reliability of a measurement. Accuracy can quickly be called into judgement when

1 Schug, K.A.; Hildenbrand, Z.L. Accredited Forensics Laboratories Are Not Properly Validating and Controlling Their Blood Alcohol Determination Methods. LCGC North America 2022 (August), 40, 370-371. https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/accredited-forensics-laboratories-are-not -properly-validating-andcontrolling-their-blood-alcohol-determination-methods

2 Schug, K.A. Fundamentals: Full Method Validation is Still a Glaring Deficiency in Many Forensics Laboratories. LCGC North America 2021, 39, 200.

3 Schug, K.A. Forensics, Lawyers, and Method Validation Surprising Knowledge Gaps. The LCGC Blog. June 8, 2015. http://www.chromatographyonline.com/lcgc-blog-forensics-lawyers-and-method-validation-surprisingknowledge-gaps

4 ANSI/ASB Standard 036, First Edition 2019. Standard Practices for Method Validation in Forensics Toxicology. https://www.aafs.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/036_Std_e1.pdf

5 ANSI/ASB Standard 054, First Edition 2021. Standard for a Quality Control Program in Forensic Toxicology Laboratories.

https://www.aafs.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/054_Std_e1.pd f

uncertainty becomes elevated. Uncertainty should also be assessed regularly, during the course of routine measurement of samples, because instrument performance does not remain constant over time. Instruments have to be regularly maintained and repaired, because their performance will eventually deteriorate with use.

Uncertainty should also be comprehensively assessed on the instrument in question. Performance results obtained from one instrument should not be used to indicate the performance of a different instrument. This statement is obvious to the readership of LCGC, but such assessments – using results from one instrument to validate performance of another – has been commonly encountered in our review of forensic lab documentation.

When a blood alcohol concentration is reported, it is usually accompanied by a value for uncertainty at the 99.7% confidence interval. In a large collection of cases we have reviewed, this level of uncertainty has been declared to be 4.3% (e.g. 0.188 ± 0.008 g/dL). This assertion claims that the “true” result for this example blood alcohol determination has a 99.7% chance of being between 0.180 and 0.196 g/dL, and only a 0.3% chance of being outside that range.

When you look in these cases to see from where the 4.3% uncertainty value is derived, you find that it has been assessed solely based on a) the repeated analysis of calibration and control standards in neat aqueous solution with internal standardization, and b) the manufacturer’s indicated uncertainty in the certified reference ethanol standards that they are provided. In the end, they ascribe more than 70% of the assessed total variability in a reported blood alcohol determination to be due to that coming from the repeat analysis of pure standards, with the remainder being attributable to the variability in the concentration of the certified reference materials, as assessed by the manufacturer.

In our opinion, this is a gross underassessment of uncertainty, especially for a method that is intended to measure a chemical substance from a biological fluid. Additionally, this uncertainty evaluation is only performed semi-annually, and the assessed uncertainty determined (4.3% at the 99.7% confidence interval) is applied across all instruments in, and results from, laboratories in the forensic lab system for blood alcohol determinations. Such a level of uncertainty can hardly be expected to be consistent for every instrument and operator in a large system of forensics laboratories, nor does it contain an assessment of uncertainty arising from biological matrices.

In the documentation for uncertainty evaluation for this collection of cases, the laboratories claim that blood matrix effects are negligible and do not need to be assessed, because they were evaluated on a couple of instruments in one of the crime laboratories in 2016. To be clear, they contend that blood matrix interferences are absent in all the instruments across the forensic laboratory system because a set of tests were performed on one set of instruments at a single crime lab, seven years ago. Additionally, not all the headspace gas chromatography instruments across the system are from the same manufacturer. The instruments used to perform the blood matrix interference studies in 2016 were from Perkin-Elmer, whereas many of the other laboratories in the system use Shimadzu gas chromatographs. Some laboratories use pressure-loop headspace systems and some used rail-based syringe autosamplers. They assume that all of the instruments behave identically, which cannot be true.

Total error in an analysis method can be determined by assessing error propagation. Total error propagates as the square root of the sum of the squares of the errors from different error sources. Detector noise is a source of error, but this is usually very minor compared to other

sources of error. Gas chromatographs are high precision instruments, and with internal standardization, they can provide very precise data, especially for pure standards. When the samples become more complex, such as moving from analysis of ethanol in water to analysis of ethanol in whole blood, greater variability will be imparted and must be assessed. Most analytical chemists will agree that the primary source of error in an overall method is sample preparation. Though sample preparation for blood alcohol determination is straightforward and generally involves a series of pipetting steps, it is not unreasonable to point out that pipettes can perform differently when transferring water versus whole blood, just based on viscoscity alone. This variability can also depend heavily on the pipetting technique used by the analyst.

There are other sources of uncertainty that are often unaccounted. As mentioned, matrix effects can develop over time as instruments are used. If blank and ethanol-fortified whole blood controls are not regularly analyzed as part of quality control in a batch sequence, to verify absence of matrix effects and maintenance of accuracy, respectively, the forensic lab has no way to know whether their data is subject to additional uncertainties. The magnitude of the effects that these can exert on results is also difficult to conjecture. Besides neglecting matrix effects, enormous variability can be introduced through improper sample handling and storage. This particular issue is a topic that deserves its own subsequent blog post.

Overall, the level of uncertainty provided by most forensic labs for reported blood alcohol results has been woefully underassessed. The methodology that has been used to estimate uncertainty does not capture changing variability amongst different instruments and instrument types, as they are used over time. It does not capture variability associated with the preparation and measurement of complex biological samples, and it definitely does not capture variability in sample handling and storage. When these sources of error are not adequately assessed, then they can only be accounted by assuming reasonable levels of the variability possible for each. When those errors are propagated together with the limited assessment of variability from the forensic lab, then the window of “true” values represented by a reported measurement becomes much wider, such that the accuracy of the measurement, especially relative to some threshold (e.g. 0.08 g/dL) becomes very debatable. Without proper assessment of the uncertainty of a method, the accuracy of the result it provides cannot be reliably established. In many of the cases we reviewed, forensics labs need to revise their procedures for uncertainty assessment, to be more realistic.

Schug, K.A.; Hildenbrand, Z.L. Laboratory Accreditation is Not a Cloak of Infallibility. The LCGC Blog. January 6, 2022. https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/the-lcgc-blog-laboratoryaccreditation-is-not-a-cloak-of-infallibility

Those working in a technical field are always trying to innovate and increase operational efficiency to produce the most value out of any given project. This requires making data-driven decisions to identify patterns and to forecast the potential implications of specific strategic moves. As with anything, these decisions are only as good as the information that they are predicated upon, and the data are only as good as the people and processes that generate them.

If your decision making relies on analytical chemistry, then you want to be confident that the measurements are an accurate representation of the matrix that is being analyzed, and that they are of “publication” quality. This is a major feather in one’s cap, especially when litigation is involved, because the state and federal court systems regard peer-reviewed data as the gold standard.

But how can you know for sure if the analytical laboratory that you’ve selected is producing reliable data? Often, we are quick to assume that analytical data is sound and accurate based on an accreditation or certification held by the laboratory in question. These sorts of credentials are meant to indicate reliable data production, because a series of compliance training, proficiency testing, and validations is generally required to achieve such qualifications. Even so, they are not the broad-scale cloak of infallibility that many might think they are. In other words, just because a given laboratory carries a certain accreditation does not mean that the data that they generate can be trusted, without performing a deeper dive into their quality assurance and quality control protocols (QA/QC).

From our experience in the energy, environmental, agricultural, and forensic sectors, one must take accreditations at face value and ask a bounty of questions about control and surrogate retention measurements, calibrations, validations, and instrumental upkeep. Fortunately, the majority of this information is made available in a good laboratory’s QA/QC reports. Below are some suggestions regarding what to look for in QA/QC reports, so that you can secure confidence in the laboratory’s work and the data that it produces.

Control and surrogate measurements: The use of surrogate, “spiked,” or control measurements are a standard practice whereby laboratory operators use samples of known concentration to assess the accuracy and precision of the response of their instruments. For many inorganic constituents, such as arsenic, an accuracy threshold window of 85–115% of the known concentration is an acceptable range. For organic constituents, such as certain volatile organic

compounds (VOCs), this range can be a bit broader; however, one should evaluate this quite closely in a given laboratory’s QA/QC to insure consistency and conformity to standards.

As an example, we recently participated in an environmental assessment of an alleged case of surface-water contamination where the detection of several VOC contaminants was being evaluated within the context of federal drinking-water standards. In this particular case, the concentrations of benzene in several samples collected from the water body of interest were elevated above the Environmental Protection Agency’s 5 parts-per-billion Safe Drinking Water Act standard. However, the QA/QC report of the accredited laboratory that performed the analyses reported accuracy ranges between 50–200% as acceptable. This means that their instruments that performed the VOC analysis could yield data that is artificially low or high by a very significant amount, and that this is supposed to be acceptable for some seemingly arbitrary reason. From our perspective, this was absolutely incomprehensible when we considered the potential legal and financial implications of the reported data in this particularly litigious matter.

Calibrations: Accurate instrumental calibration may singlehandedly be the most important aspect of reliable data generation in analytical chemistry. Proper calibration allows the operator of a given instrument to interpolate the concentration of a particular constituent based on the instrumental response to samples of known concentrations. This requires that one’s calibration standards and certified reference materials (CRMs) are dependable and haven’t expired, and that their serial dilution, for the preparation of a multipoint calibration curve, is performed accurately. If performed correctly, a multipoint calibration curve of five to seven points should yield a linear correlation value (r-value) >0.99. The incorporation of an internal standard is nearly always a best practice.

It’s important to keep in mind that an instrumental measurement is only reliable if the sample response signal falls within the range of the calibration curve. Attempting to quantify the concentration of given analyte when extrapolating beyond the range of the calibration curve can lead to inaccurate measurements and unreliable data.

We’ve seen this phenomenon plague commercial laboratories in the cannabis/hemp sector, particularly with the analysis of concentrates and oil products. Depending on the state, laboratories operating in this space may not yet be guided by a specific set of analytical recommendations to guide their QA/QC practices. A problem arises when analysts may only run three calibration standards to create their calibration curve, which can then represent an artificially high (or low) calibration range. As a result, the analysis of a concentrated sample can then present a signal that is beyond the calibration range. The software then does its best to extrapolate the concentration of the constituent of interest, and you end up with an inaccurate measurement.

A particularly egregious example of this was presented on LinkedIn. A cannabis business owner was so proud to present their new concentrate product that had a delta-9tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration of 1,045 mg/g. That’s right, it was 104.5% pure – a

reality-defying innovation. We attempted to shine light on this inaccuracy by inquiring about the QA/QC with the laboratory in question, but we all know how “collegial” discourse goes on the internet. Long story short, it turned out to be a calibration issue that wasn’t caught during data processing and reporting.

Furthermore, it is important to ask your laboratory of interest how frequently they calibrate their instruments. Instruments can fall out of calibration for a number of reasons, and it is important that these changes in performance are accounted for as they arise. Ideally, calibration should be performed on the same day that real samples are analyzed for their determination.

Validations: Laboratories performing quantitative and qualitative analyses need to follow certain protocols for method validation. These are generally industry-specific but are similar in the types of the measures they prescribe in order to demonstrate that a method is fit for use and can be expected to provide reliable results. In forensics chemical analysis, we often see this lacking it appears that much of the standard method validation guidance was provided some years after the establishment of many forensics measurements, and that the industry has been slow to conform. This lack of conformity creates a great deal of uncertainty in measurement results.

As just one example, the Texas Department of Public Safety currently asserts that all of their headspace gas chromatograph instruments operated across the state are free of matrix effects during blood alcohol measurements, because this was evaluated on a couple of instruments in Austin. Many of these instruments are also from different manufacturers than those in Austin and have different headspace sampling configurations. That is akin to assuming that your Honda Civic runs well because your friend’s Ford Fiesta is running well. This is not a reliable practice. Every instrument must be individually fully validated using the prescribed procedures in order to prove that they provide reliable results.

Instrumental upkeep: Analytical instruments need routine maintenance and often require major repairs after a significant amount of use. Laboratories should keep regular maintenance logs to document instrumental upkeep. Additionally, major alterations, such as the installation of new columns, require re-validation of the method according to guidelines. There should be documented re-validation of the instrument performance following major maintenance efforts.

Collectively, reviewing these QA/QC-related items can reveal a considerable amount about the veracity of the data being generated by a given laboratory. The technical fidelity of a laboratory’s QA/QC report is far more insightful than a simple recitation of standardized accreditations and certifications that may be held, which as we’ve mentioned, should be taken with a grain of salt. All of this feeds back into the simple truth that the only thing worse than no data is bad data. Given our evolving world where correlations, projections, and ultimately, datadriven decision making are the standard, it is paramount that the information that we are reliant upon, is generated from a trustworthy source that exercises proper QA/QC procedures.

Schug, K.A. Full Method Validation is Still a Glaring Deficiency in Many Forensics Laboratories. The LCGC Blog. August 30, 2021. https://www.chromatographyonline.com/view/the-lcgc-blogfull-method-validation-is-still-a-glaring-deficiency-in-many-forensics-laboratories

I am flummoxed at the number of times I have encountered documentation of measurements made by public and private forensics labs for blood alcohol or drugs of abuse that does not include proper method validation. Over the years, I have been doing some consulting, reviewing what are called discovery documents associated with myriad different cases along these lines. I have also written previously, now more than six years ago, about an apparent lack of understanding of the importance of method validation by lawyers and judges involved in litigation involving forensics measurements. i

With each case I have worked on, it becomes apparent, there are common deficiencies regularly encountered in forensics analysis. Rarely, have I been asked to review a case where I felt a comprehensive and completely reliable job had been performed. Of course, I am sure there are forensics labs out there that ‘do it right’, but somehow, records from those cases do not often cross my desk.

The deficiency in method validation for forensics labs regularly manifests itself in two steps. The first step is where the forensics lab does not even provide any indication of method validation when delivering documentation of the case. The second step comes when the documentation made available indicates a lack of rigor in method validation.

The most complete guidance for forensics method validation is the recently published ANSI/ASB Standard 036. ii Standard 036 replaces previous comprehensive guidance documentation from the Scientific Working Group for Forensic Toxicology (SWGTOX) and provides all of the necessary steps for full and partial method validations pursuant to ISO 17025 performance criteria. ISO 17025 is more of a catch all guidance of best practices and provides less specific detail about how to accomplish forensic method validation than Standard 036.

Overall, method validation is a series of documented steps that demonstrate that the chemical analysis method on a particular instrument is fit for purpose – that, with proper calibration and quality control, the method can provide a reliable result. Any chemical analysis method, be it widely used or not, must be fully validated on the instrument where it will be performed.

Analytical instruments are exceedingly high precision measuring devices; ultimately, each is manufactured separately (there are also many different manufacturers) and may perform differently to some degree.

Forensics labs should be able to provide details regarding instrument installation, that the system met manufacturer specifications for performance once installed. Following that, full method validation should have been performed and been well documented prior to the analysis of any case samples. Full or partial validation should also be performed following major instrument changes or maintenance. For example, replacing or changing an analytical

separation column can have a major impact on method performance; the method performance needs to be rechecked using method validation procedures and redocumented.

Those of you in the analytical science community are likely well familiar with the concept of method validation. If you have developed a new quantitative method, it is almost impossible to publish it without extensive validation information. Whether using guidance from Standard 036, or some other guidance from, for example, the Food and Drug Administration or the Environmental Protection Agency, method validation will regularly involve determining the accuracy, precision, limits of detection and quantification, specificity, potential for carry-over, and other figures of merit for the method. Processes to determine these are given using specific blank, fortified (in other words, spiked), and real samples, run multiples of times and data treated to provide each measure. The extensiveness of validation can be somewhat dictated by the complexities of the method. For example, sample preparation procedures, which contain multiple steps, should be evaluated for their efficiencies and recoveries, to help ensure an accurate result is rendered.

A problem I regularly encounter is the lack of adequate evaluation of matrix-matched samples during method validation. A variety of steps should involve the analysis of blank or fortified matrix-matched samples in order to evaluate the specificity of the method and its subjectivity to matrix effects, or changes in the analysis exerted by the presence of interferences in the sample. Chemicals other than those of primary interest for the determination in a sample (in other words, the sample matrix) can alter the final signal of the target analyte in many different ways.

Blood drug determination by liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry is famously prone to matrix effects associated with ionization efficiency. That is why deuterated internal standards are a must for those determinations. Yet, matrix components for many types of chemical instrumental measurements can exert effects throughout the process from sample preparation, through chemical separation, to final detection of signals. The method validation steps involving measurement of fortified matrix samples are key for establishing lack of interferences (in other words, specificity).

Here is another example. It is often desirable to routinely use neat solutions of target analytes to prepare calibration curves for quantitation of a chemical in a biological fluid sample. In such a case, it needs to be shown during method validation that equivalent calibration results can be obtained from neat solution vs. from biological fluid; the absence of matrix effects needs to be demonstrated. This is not an onerous task, but without this information, you would not know if results were subject to some bias.

Sometimes, matrix effects can be subtle. Five years ago, I wrote about a case where matrix effects yielded statistically significant differences in the response of an n-propanol internal standard, when measured from neat solutions compared to when it was analyzed from real blood samples, for blood alcohol measurements. iii This matrix effect appeared to, on average, cause all blood alcohol determinations on that instrument to be reported 20% higher than they likely were. The lab in question never used fortified matrix samples in their validation; thus, they had no knowledge of this bias. The sad thing is that I have encountered this instrument again a couple of years ago. I was able to show the same matrix effect and bias in the data I had seen years prior. That instrument has likely been reporting high biased blood alcohol results since its initial routine use in 2011.

Another common problem with the lack of evaluating blank or fortified matrix-matched samples during blood alcohol measurement validation and routine use, is that specificity can often not be demonstrated. Most forensics labs use flame ionization detection (FID) for their gas chromatograph. An FID responds to anything carbon-containing that elutes from the column. Often one observes extra so-called “ghost peak” signals present in around the chromatogram near the ethanol peak and the internal standard peak when real samples are analyzed. These may be present or absent in various neat samples, but if a blank fortified matrix sample was never analyzed to show there are no background signals present at the retention times of ethanol and the internal standard, then there is no way to guarantee the accuracy of the result. Small or large coelutions of interferences with ethanol or the internal standard can have a marked and very unpredictable effect on the final calculated result of the measurement. Standard 036 specifies that blank matrix samples from a minimum of ten different sources be evaluated during method validation to establish the specificity, or the lack of interferences, for the method. I think I have seen that documented in forensics discovery documents only once or twice.

I could continue this discussion with other such examples. However, the point I want to make is that the steps for proper method validation are well spelled out. Many forensics labs appear to obtain various accreditations without apparently being able to show they have performed and documented performance of these specific steps. I see poorly validated analyses from accredited forensics labs all the time.

The steps to proper method validation are not difficult measurements to make, but they are critical for establishing the reliability of the method. I do not understand why these deficiencies are so common, and I do not understand why they persist. As a result, I have started a business called Medusa Analytical, LLC (www.medusaanalytical.com) that will, for a nominal fee, evaluate the veracity of discovery documentation. We return a checklist to the lawyers after a preliminary review of the discovery documents to indicate what things are missing or deficient. We hope this will help provide a broader capability to help ensure that only quality forensic measurements are being considered in litigation.

Forensics chemical measurement methods are generally pretty straightforward and should be reliable. There are well prescribed and straightforward ways to show the method is reliable vis-à-vis Standard 036 guidance. It just seems wrong that measurement results shown deficient in some aspect of method validation should be allowed to stand; especially, if they are called into question based on some aspect of a particular case sample, like the presence of ghost peaks. If the appropriate steps were not taken to ensure specificity of the method, then specificity should be doubted and the reliability of the result should be doubted.

In the end, it always seems like a game about how much deficiency in the forensics chemical analysis process will a court or jury tolerate. Why should there be any tolerance for deficiency when a person’s livelihood is at stake? In my opinion, the chemical analysis should be one of the most reliable pieces of evidence in the case; it is a shame to see that it often is not, because a forensics lab apparently decided to cut some corners.

Schug, K.A. Forensic Drug Analysis: GC–MS versus LC–MS. The LCGC Blog. July 5, 2018. http://www.chromatographyonline.com/lcgc-blog-forensic-drug-analysis-gc-ms-versus-lc-ms

If given the need to determine drug A or its metabolite in blood, 99% of the time I would choose to start with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). When I asked a couple of former students who work in a forensics crime lab, they said they were split about 50/50 on the methods they use for drugs of abuse that feature LC–MS versus gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). It was actually a relief to hear that there was only a 50% skew toward GC–MS. For the past two years, my group has run a blood drug analysis course at UT-Arlington for defense lawyers through the National College for DUI Defense (NCDD). During the courses, I gave an introduction to LC–MS. Last year, not a single lawyer attending the course had previously come across LC–MS forensics analysis in the courtroom. In fact, the vast majority had not heard of liquid chromatography before. This year, two out of 24 lawyers in the course indicated they had heard about LC–MS, but they had still not faced such evidence in a case.

Anecdotally, it sounds like there is not a lot of variation in forensic drug analysis across the country. My students in their crime lab appear to be in the minority (and ahead of the curve). One lawyer in our course indicated that in the state they practice, their labs use GC–flame ionization detection (GC–FID) for blood drug analysis. If that does not make you worry, then it should. I am so flabbergasted by this, I don’t even want to mention the state – luckily, it is not a heavily populated one.

GC–FID is much less sensitive and specific compared to GC–MS. In combination with headspace sampling, GC–FID is still used to a great degree for blood alcohol content (BAC) determinations. BAC measurements do not require a great deal of sensitivity, and there are very few volatile interferences in blood. Even so, GC–MS would still be preferred. GC–FID can only identify a compound based on its retention time, whereas GC–MS also provides mass spectral information for each peak. When you get to the trace levels of drugs and metabolites in biological fluids, you need sensitivity and specificity; these are readily provided by an MS detector.

In our short course, I asserted to the lawyers that the use of LC–MS for drug analysis is on its way. Eventually, it will show up in the courtroom but why is it taking so long to get there? It is obvious that GC–MS is a more established technique in forensics labs. It also appears that forensics labs are generally resistant to change. Why should they change if the way they are currently generating data is acceptable to the courts? I could easily argue that the courts do not, in general, know any better, but maybe it is instructive to make a little comparison.

Table I provides some points for comparison of GC–MS, for an electron ionization (EI) source and a single-quadrupole mass analyzer, with LC–MS, using electrospray ionization (ESI) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) on a triple-quadrupole instrument.

Aspect GC–EI-MS

General application

Volatile, thermally stable molecules (low- to midpolarity); low-volatility compounds need to be derivatized

LC–ESI-MS/MS

Nonvolatile, polar and ionic molecules (mid- to highpolarity)

Cost ~$100k ~$200k

Available? Established? Yes, yes Yes, yes

Sample preparation for biological fluids

Limits of detection and quantification

Specificity?

Liquid–liquid extraction; solid-phase extraction; derivatization (to make polar compounds more volatile); finish in volatile solvent

Nanogram (10-9 g) to picogram (10-12 g)

Yes, via EI mass spectrum (library matching; abundant diagnostic fragment ions from EI); lack of molecular ion is a problem

Matrix effects? Minimal

Dilute-and-inject (urine); Protein precipitation; liquid–liquid extraction; solid-phase extraction; finish in polar solvent (water ideal)

Picogram to femtogram (1015 g)

Yes, via MS/MS; monitor specific fragments of desired molecular ion using triple quadrupole; no universal library matching

Yes, require stable isotopically labeled internal standards for each analyte

Without diving in too deeply, there are a few aspects that make LC–MS better amenable for determination of drugs in biological fluids. First and foremost, LC–MS is ideal for applications involving drugs, which generally are polar and nonvolatile molecules. Efficient separation and ion generation can be accomplished using LC–MS without derivatizing the analyte. For GC–MS, derivatization is necessary to chemically modify the drug and make it more GC-amenable (that is, more volatile). Underivatized drugs analyzed by GC–MS will generally exhibit poor peak shapes (reduced resolution) and reduced sensitivity. A derivatization step also can add significant uncertainty. In general, sample preparation steps are more prone to error than other parts of an analytical method. More sample preparation steps equate to increased error in determinations, and chemical derivatization is an intensive process that can be prone to uncertainties such as the quality and age of reagent, presence of interferences in the sample, variability in lab conditions, and so on. LC–MS generally requires less sample preparation. For a urine analysis, one can often just dilute with water and inject the sample. With LC–MS, using ESI, an intact molecular ion is generated and enters the mass spectrometer. Using GC–EI-MS, the signal for a molecular ion may not be readily apparent because of the extensive fragmentation generated by the 70-eV ionization energy. Even so, EI generates a nicely diagnostic mass spectrum that can be reproduced across different

instruments, and only requires a single quadrupole mass analyzer. GC–MS is generally cheaper because it uses a less sophisticated detector. For LC–MS, one gains specificity with the use of a triple-quadrupole mass analyzer. In the triple quadrupole, the initial ion of interest is isolated, then fragmented in a collision cell, and then unique ion fragments are interest are used to quantify the compound and confirm identity.

In this MS/MS operation, signal-to-noise levels are increased dramatically by reduction of noise. As a result, LC–MS determinations usually exhibit lower limits of quantification (LOQs) than GC–MS determinations (although this may be application specific). These lower LOQs are important for forensics drug analysis, because one does not want to be operating very close to the LOQ if it can be avoided. First, determinations made closer to the LOQ are usually subject to higher error. Second, when one operates close to the LOQ, it is possible to lose some of the specificity of the determination. Confirmation of the target can be made based on the presence of three or four ions (and a consistent intensity ratio between them); this statement is true for both GC–EI-MS and LC–MS/MS. Because LC–MS is more sensitive, there is a better chance for those ion ratios to be preserved when the compound is present at low levels, especially levels close to the LOQ for GC–MS, where some lower abundant ion fragments would not be observed.

To be fair, a place where LC–MS has problems relative to GC–MS is with matrix effects. The matrix is everything else in the sample besides the analyte. In biological fluids, there are ample species in the matrix that can interfere with an analyte measurement. Matrix effects can cause unwanted changes in analyte response; they will compromise the accuracy of the determination if they are not properly accounted. For this reason, it is necessary to use stable isotopically labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) for each analyte of interest. This means that for each analyte, a pure isotopically labeled internal standard (a deuterated, 13C-labeled, or 15Nlabeled version of the analyte) must be used to normalize matrix effects. This internal standard will be eluted with the analyte, buts its signal will be differentiable from the analyte because it has a different mass, and it will yield different fragment ions. These compounds are expensive, but without their use, LC–MS determinations of drugs from biological fluids will be subject to significant error and largely considered unreliable.

This topic could be discussed a great deal more. I expect to address it more in the future. The interface between the forensic and legal communities is one where getting the analysis right is more important than ever. People go to jail or pay massive fines for illegal actions involving drugs. It should be the responsibility of the crime labs to use the best technology for their analysis, to avoid error in their case assessments. If you are still wondering whether the evidence is strong enough favoring LC–MS over GC–MS for drug analysis from biological fluids, go to any clinical lab and count the relative number of GC–MS and LC–MS instruments they have. GC–MS will lose. GC–MS simply cannot provide adequate performance across the large and growing range of illegal substances desired to be detected. On the contrary, one would not need to look far for demonstrations of LC–MS methodologies that can handle virtually all drug compounds of interest, using a single method with minimal sample preparation (1). LC-MS instrumentation and processes may be more complicated than GC-MS, and there might be a couple of different controls to have in place, but LC–MS should be the future of forensic drug analysis.

1. S. Lupo, Restek Corporation. https://www.restek.com/pdfs/CFAR2309-UNV.pdf

Schug, K.A. An Indisputable Case of Matrix Effects in Blood Alcohol Determinations. The LCGC Blog. Sept. 7, 2016. http://www.chromatographyonline.com/lcgc-blog-indisputable-casematrix-effects-blood-alcohol-determinations

In a recent review of blood alcohol casework performed by a forensics laboratory associated with a major metropolitan police force, I was again (1) disheartened to find major deficiencies in method validation protocols. In this case, the analysts failed to check whether aqueous solutions for calibration and quality control were reliable surrogates for real blood samples. What I describe here is the definite possibility that matrix effects have caused this laboratory to overreport blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) determined on one of their headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) systems since 2011. The fact of the matter is that this forensics laboratory would never be able to dispute this claim, because they lack the protocols and data that would be necessary to check for such an effect. Importantly, best practices and trusted guidelines say they should have checked for this effect as part of a comprehensive ongoing method validation and revalidation plan, but they have failed to do so.

An internal standard HS-GC method was used to measure BAC. As is generally the case, n-propanol was used for the internal standard, since it is unlikely to be found naturally in human blood samples, it has similar properties to the target analyte, ethanol, and it produces a distinct signal for measurement (that is, a separate peak). n-Propanol is added in a consistent quantity to every calibration standard, quality control, and real case sample. It is then measured along with the ethanol during each analysis. This measurement is done to normalize ethanol responses and reduce systematic and random errors associated with sample preparation, injection, chromatographic separation, and detection. A key point is that the internal standard should behave essentially identically to the analyte throughout these steps, so that any losses or gains experienced by the analyte would be also experienced by the internal standard, and therefore corrected in the final unknown determination.

In the case (or cases) in question, data indicated it is plausible that a matrix effect altered the response of the internal standard. Matrix effects are known to systematically alter reported results, if they are not accounted for and corrected. They can be sample dependent, analyte dependent, and concentration dependent. A good analytical scientist will always seek to either use a matrix for calibration that is essentially equivalent to the samples tested (that is, prepare spiked standards into a blood matrix), or conduct validation measurements to check whether calibration in a surrogate matrix (that is, an aqueous solution) is valid for determinations in samples of a different matrix. Neither of these steps were performed by the forensics lab.

The laboratory’s analysis was performed using a graphical internal standard calibration. A series of calibration solutions was prepared in aqueous solution (a sodium chloride–fortified water solution) in which the solutions contained varying amounts of ethanol and a consistent amount of n-propanol. Each of the standards were analyzed by HS-GC, and the relative responses (response of ethanol/response of n-propanol) of the standard solutions were plotted

against the relative amounts (amount of ethanol/amount of n-propanol) to create a calibration curve. Over a relevant range of ethanol levels, a linear equation can be generated for use in determination of unknowns. The unknown solution (blood matrix) was prepared to contain an equivalent amount of internal standard as in the calibration standards. When the sample was analyzed, the relative responses of ethanol and n-propanol, along with the known amount of npropanol added, allowed the analyst to determine the unknown ethanol concentration using the previously established linear equation. A problem could arise when the components of interest (the ethanol and n-propanol from the aqueous matrix and the ethanol and n-propanol from the blood matrix) are not equivalently transferred from the sample into the chromatographic system.

In this case, it was evident that the transfer efficiency of the n-propanol internal standard into the headspace was disproportionately lowered during the analysis of the real samples, compared to the analysis of standard aqueous samples. Overall, peak areas for the internal standard response were consistently in excess of 20% lower when analyzed from blood samples, compared to when they were measured from standard aqueous samples. From the data I evaluated, this is a trend that appears to be consistent on this particular instrument since 2011. From the data alone, it is hard to surmise the exact mechanism of this matrix effect –whether it is chemical or instrumental in nature.

What is an absolute travesty is that no measurements were ever performed to check whether ethanol responses were similarly or differently affected by the matrix. Well, I suppose the analysts never recognized the systematically low response of the n-propanol, but the main point is that such checks should be built into a reliable method validation plan.

So, if we assume that the matrix only had a response lowering effect on the internal standard and not on the analyte which is an absolutely possible situation and is indisputable based on the lack of data to show otherwise then all of the reported ethanol values from blood samples would be high, perhaps more than 20% high. In other words, a lower internal standard response caused by matrix effect, with a consistent ethanol analyte response, would increase the calculated relative response used to determine the unknown concentration. The result would be an artificially high value reported for the unknown analyte based on calibrations performed in an aqueous matrix.

Based on a 20% bias, someone with an actual 0.07-g/dL BAC (below the legal limit) could register a 0.084-g/dL BAC (above the legal limit) according to the assay. And that is just a conservative average. One could imagine, on a per sample basis, much more extreme biases occurring. Again, the point is that the apparent bias was never noticed and evaluated. There are more nuances to this case, including the use of only a four-point calibration, failure to comprehensively check bias, precision, and carry-over, and lack of revalidation following instrument maintenance. I have been employed as a consultant to review this and other cases. In some cases (based on data from other forensics labs), I find nothing much of note to report. However, this is a case where well accepted and published best practices for method validation have not been followed. As a result, there could be some significant injustice. Rather than addressing these on a case-by-case basis for various defendants, it would seem more efficient to work together with forensics laboratories to ensure their method validation is up to par. However, anecdotally, I am told that the likelihood of such a thing happening is very small, because they are too set in their ways. That is a shame. Rulings of guilt

associated with blood alcohol cases and driving under the influence are truly life crippling. Where justified, these decisions should be rendered, but this seems a setting where the laboratory really has to have the analytical science correct. In the case I described above, I believe they do not.

Reference

1. K.A. Schug, The LCGC Blog, June 8, 2015. http://www.chromatographyonline.com/lcgc-blogforensics-lawyers-and-method-validation-surprising-knowledge-gaps

Schug, K.A. Forensics, Lawyers, and Method Validation Surprising Knowledge Gaps. The LCGC Blog. June 8, 2015. http://www.chromatographyonline.com/lcgc-blog-forensics-lawyers-andmethod-validation-surprising-knowledge-gaps

Recently I served as an expert witness in a case involving the detection of a cocaine metabolite, benzoylecgonine, in a defendant’s urine using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). This test was performed at a forensics laboratory following a reported positive test using a preceding immunoassay screen for drug metabolites. I will not relay any more details than this, because the problem in question dealt with an apparent lack of GC–MS method validation. For the analytical community, method validation in some form or another is a natural extension of best practice in the analytical laboratory. However, the notion of method validation, and many aspects of detailed forensics analysis, are not well understood by most lawyers and judges. I suppose that this might not be surprising to most, but it does present a serious knowledge gap that must be bridged in cases involving substance or alcohol abuse, if the associated case is to be properly litigated. In this particular case, I was called to testify on the basics of GC–MS, its complexities in analytical method development, and the necessity of method validation and verification. As part of my testimony, I was asked to write a very basic account on the importance of method validation. Below is the bulk of the text that I submitted for this purpose. I thought it might be interesting to relay in the LCGC Blog forum to raise awareness for others that such a knowledge gap does widely exist, and that it is vitally important for analytical scientists to be able to convey such concepts to the public community in fairly simple terms. At the end, I give a bit more about the problem associated with the case in question, which itself is fairly surprising.

Method validation, the comprehensive performance and documentation of measurements to verify a method is reliable and fit for purpose, is an essential component of any analytical chemical measurement. The failure to appropriately validate and document a method makes it is impossible to prove the validity of the scientific test performed by that method. Such a result would be scientifically unacceptable.