BadFacts

•Don’thidefromthem.Bestrategicinaddressingthem.

•Explaintheminoneortwosentences.Givelogicalcontexttothem.

•ConsiderState’sperspectivewhenaddressingthebadfacts.

•Thiswillaidinyourcredibility.

SummarytoReinforceTheme

•Summarizethepointsyoumade.

•Notnecessarytoreplaybadfacts.

•Thisisashorterversionofthesummarybutkeepsyourtheme.

•Ex:AccidentDWIbutclientwasonhisphone.

7/18/2023 5

Conclusion

•Remindjuryofcase’stheme.

•Remindpanelofburdenofproof.

•Tellthejurywhatisexpectedwhenthecaseconcludes.

Behavior

•Makeeyecontact.

•Showthatyoubelieveinthecasewithoutbeingoverlydramatic.

•Speakdirectlyandpersuasively.

7/18/2023 6

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

21st

10 Silver Bullet Trial Tactics in a DWI Case

Speaker: Todd Overstreet

The Law Office of Todd Overstreet, P.C.

5300 Memorial Dr Ste 750 Houston, TX 77007

713.222.0600 phone

713.222.0647 fax

ctolawyer@sbcglobal.net email

https://www.toddoverstreetlaw.com/home website

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Annual Top Gun DWI August 11, 2023 The Whitehall Houston, Texas

10 Silver Bullet Trial Tactics in a DWI Case

The Art of Legal War

Todd Overstreet Lawyer

Top Gun Seminar: August 11th, 2023

1

Sun Tzu, in his well known military treatise The Art of War, cautioned against repeating battle strategies, even if they worked in the past. He warned and advised, “Do not repeat the tactics which have gained you one victory, but let your methods be regulated by the infinite variety of circumstances.” Written roughly around the 5th century BC, it appears to be an early and valuable proclamation of what we know all too well as lawyers…EVERY CASE AND/OR CLIENT IS

DIFFERENT!

That said, there are some ‘tried-and-true’ trial tactics that myself and other trial lawyers have developed, borrowed or out right stolen, and then used against the State and their witnesses to get ‘Not Guilty’ verdicts. So let’s get started…

BULLET ONE: MOTIONS IN LIMINE

I will not and cannot say the name of the elected District Attorney or the County, but when I first left the United States Attorney’s Ofice and teamed up with Gary Trichter and Doug Murphy, I filed a slew of motions from Gary’s CRAMAZING ‘motions bank’ for an upcoming trial. I admittedly went a little overboard, but filing motions was a foreign concept for me as a former State and Federal Prosecutor. This was back during the time you had to print your Motions out, sign and get notarized (i.e., client afidavits for Motions to Suppress), and then head up to the courthouse and wait in line to file them with the Clerk. For this particular case, my motions looked more like I had photocopied two entire volumes of South Western Reporters and turned them into the Court, as I’m pretty sure I was charged by the pound. About a week before the trial, I called the DA’s Ofice to talk to the assigned prosecutor and was told the case was dismissed. Given some of the bad facts with the case - airline pilot client involved in car crash who was an absolute jerk to the DPS Trooper - I was more than shocked and asked, “Why?” The prosecutor, with very little hesitancy or regret said, “I got your Motions and it was too much to read.” And so it began…

2

It goes without saying, every effective lawyer will (or should) file motions to suppress physical evidence or statements harmful to their clients. But in DWI cases specifically, I always file Motions in Limine against the State and/or their witnesses to be heard either before jury selection or the State’s case-in-chief. Even if I don’t prevail in restricting them from asking certain questions or keep out potentially harmful testimony, it ALWAYS flushes them out! I learn more about what’s to come and how to adapt than at any other ‘Pre-Trial’ phase of the case. Always follow the current law and PLEASE be creative, but here are a few of my favorites:

*Motion in Limine to Prevent the State during Voir Dire from Inaccurately Stating the Applicability of Chapter(s) 524 & 724 of the Texas Transportation Code;

*Motion in Limine to Prevent the State from the Improper use of Commitment Questions during Voir Dire (regarding Per se Intoxication / lack of breath or blood test evidence / etc.);

*Motion in Limine to Prevent the State’s Witness(es) from Improper Correlation of Field Testing with BAC.

BULLET TWO: Standefer COMMITMENT QUESTIONS

We’ve all heard and were taught that ‘knowledge is power,’ but I like the concept authored by Warlord - Samurai Takeda Shingen a lot better, “Knowledge is not power, it is only potential. Applying that knowledge is power. Understanding why and when to apply that knowledge is wisdom!” From watching and participating in countless criminal ‘voir dire(s)’, I think this is particularly true with

3

the use of PROPER commitment questions, as well as understanding when they are improper.

Perhaps the most referenced and cited case on the propriety of commitment questions is Standefer v. State, 59 S.W.3d 177 (2001). Read it, re-read it and keep a copy handy for trial, along with it’s subsequent analysis history. The main thing to remember about commitment questions, though, are that a proper use of them gets the jury talking and can make the difference on getting the right jury for your client’s case. For example, in Tijerina v. State, 202 S.W.3d 299 (206), the Defendant was a convicted felon and likely wanted to testify. Defense Counsel, in order to ascertain upfront whether his client would get proper and ‘unbiased’ consideration by the jury during the trial, asked the panel the following question:

"Is there anybody here who feels that you would automatically disbelieve somebody simply because they are a convicted felon, be they a witness, a police oficer, a defendant, anybody?”

The Court of Appeals concluded that the question was a commitment question, properly asked and used to determine if any of the jurors had an ‘automatic predisposition’ to disbelieve a witness (his client) who was a convicted felon. Point is, knowing this area of the law better than the State or Court, and then applying it to the potential problems with your case during jury selection, will get the jurors talking and will allow you to obtain the wisdom needed to pick a good jury.

BULLET THREE: ATTITUDE

Yes, ‘Attitude’ is a Silver Bullet! Obviously you need to be prepared for your trial and research and analyze all possible strengths and witnesses, but like it or not you are being judged and measured by the jury the first moment they walk into the

4

room…similar to your client(s). So what are you doing behind the scenes to mentally prepare yourself to exude an ‘attitude’ of confidence, control of the courtroom and trustworthiness? I’m not the best at asking for advice or assistance, but I do love to read. So here are a few books that I recommend that have helped me address personal and professional self-confidence concerns, benefiting my ‘attitude’ during trial and connection with jurors:

*Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges, by Amy Cuddy;

*You are a Badass: How to Stop Doubting Your Greatness and Start

Living an Awesome Life, by Jen Sincero; and

*The Confidence Gap: A Guide to Overcoming Fear and Self-Doubt, by Russ Harris.

Speaking of books, ‘attitude’ and connecting with juries… I always bring a book I’m reading (purportedly) and put it near my stuff on the table for the jury to see. The effects of this subtlety were accidental, but profound. While trying a case in Rusk, Texas, I was actually reading a book about Ronald Reagan. The judge was incredibly confrontational towards me and equally ineficient, so we took lots of breaks. During one of the longer breaks I started reading my book, and when the judge brought the jury out to ask if they wanted to continue or pick back up the following day, the book was on the table right in front of jury. You may laugh, but up to that point I was a pariah. When they saw that book near my trial file their entire ‘attitude’ towards me changed. After the trial, the first words the foreman said to me were, “I’m reading that same book…and we love Ronald Reagan (around here).” I’ve had a ‘place and topic’ appropriate book near me at trial ever since.

5

BULLET FOUR: 38. 23 VOIR DIRE

“I never assume…it only makes an ASS out of U and ME.” So, in the abundance of caution that the reader is unfamiliar with Article 38.23 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, here’s what it states: “No evidence obtained by an oficer or other person in violation of any provisions of the Constitution or laws of the State of Texas, or of the Constitution or laws of the United States of America, shall be admitted in evidence against the accused on the trial of any criminal case. In any case where the legal evidence raises an issue hereunder, the jury shall be instructed that if it believes, or has a reasonable doubt, that the evidence was obtained in violation of the provisions of this Article, then and in such event, the jury shall disregard any such evidence so obtained.”

It’s a mouthful, sure… But given the fact that nearly every DWI trial involves litigation over the stop, the admissibly of certain statements and test results, questions regarding the exclusionary aspects of Art. 38.23 can be a good tactic for eliminating “State’s Juror(s)” and/or developing a rapport with venire members you may want to keep. Here’s an example:

“Juror No. 7, based upon your response to the Prosecutor’s questions about breath and blood testing, it appears to me that’s the type of evidence that would carry a lot of weight with you…is that correct? What if the evidence at trial raised an issue that the blood samplewhich was later tested - was obtained by the Oficer illegally?…What effect, if any, would that have on the weight you would give it?”

“Juror No. 8, If you believed that the evidence (blood sample) was obtained illegally, could you follow the law and the Judge’s instructions to disregard it?

6

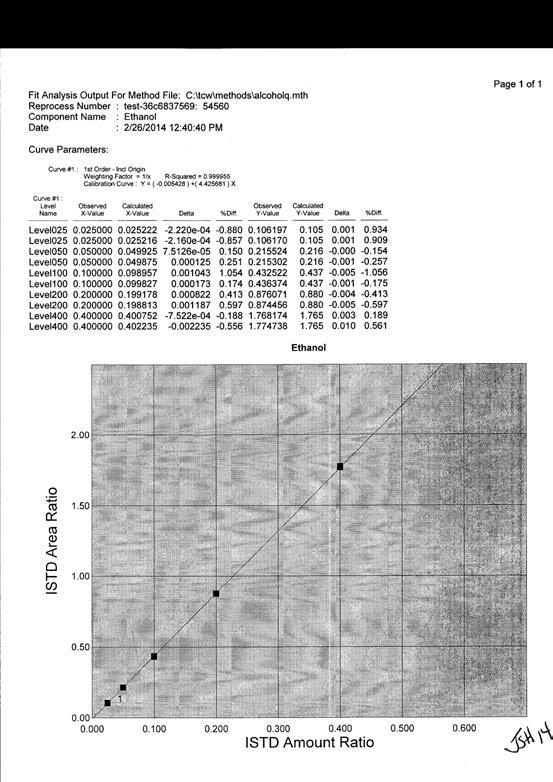

BULLET FIVE: DISCONNECT

I started using this tactic early on in my defense practice, as it just made sense. The theory of ‘Disconnect’ is based upon the principal that most people place more faith in what they see, versus what they hear and are told to believe. As applied to DWI cases, this would be situations wherein the jury sees a Defendant who looks and/or sounds normal (not intoxicated), but has a high BAC. The juror(s) suspicions are then compounded when the State’s Expert testifies that this same Defendant would have to have consumed some ‘crazy amount’ of alcohol - like 8 to 10 drinks - to achieve the sample result. If set up during Voir Dire, and then hammered home during cross-examination of the State’s witnesses, it can be an incredibly successfully DWI Defense tactic.

I ran track in college, so during Voir Dire I like to use examples wherein it would have been physically impossible for a particular individual to have run some absurdly fast time or distance, though we are being told otherwise. For instance:

“Juror No. 10, Are you aware that the fastest time in the 100m dash and Men’s World Record is 9.58 seconds?” I will then show them a photo of some celebrity like Hal Smith, who played Otis Campbell on The Andy Grifith Show, and gauge their reaction.

These are not ‘cause questions’ and are used solely to set the stage to later attack the State’s absurd position that their BAC results are infallible, so use your time during Voir Dire valuably. Also, you need to make sure you have your follow up cross-examination questions prepared to create the record that you can ultimately use in closing. Lastly, make sure you a well-read and versed on the various scientific studies and articles discussing the documented effects of alcohol on the human body, as this is a unique opportunity to use their own science against them (I.e., Garriott’s Medico-Legal Aspects of Alcohol (5th or 6th edition).

7

BULLET SIX: OPENING ARGUMENTS / STATEMENT

Why do I feel like whenever I hear a Defense lawyer stand up and tell the Judge, and thus the Jury, that they want to wait to give an opening statement during their case-in-chief that it really just means they aren’t prepared? That has to be the only logical conclusion, given that it is the only time during the trial that the Defense gets to take it’s first shot and have the last word. I’m not going to cover how to do one, but rather strongly suggest you incorporate a strong opening as a Defense tactic. That said, one of the constants in my openings are references to favorable discussions with the jury during Voir Dire. For example:

“One of the things we talked about, and you agreed with during Voir Dire, is the value of reliable and credible records kept by police oficers. The evidence will show that Oficer Smith filed a police report the day after Mr. Jones was arrested. Oficer Smith will admit that there in no documented evidence that Mr. Jones displayed slurred speech during their initial conversation, nor did he display any signs of physical loss prior to the road tests.”

This tactic not only begins the dialogue of exposing an ineffectual investigation and improper arrest, but hopefully solidifies that connection they have with you and your client.

BULLET SEVEN: WITNESS CONTROL

If the first shot in the battle is your opening, then being prepared to control the State’s witnesses has to be your next move and tactic. In order to do this, you need to know your opponent and increase your knowledge and effective use of the rules of evidence.

Let’s start with witnesses, which are mostly police oficers. For better or worse, gone are the days when roughly half of the oficers showed up at ALR Hearings,

8

giving you an opportunity to question them and learn how they testify. Now I dare say it’s 10% of the time. But you can still get a pretty good idea about how an oficer is going to be on the stand by reading their reports and watching their body-cams. If they are condescending to your client, then good chance they are going to act like that when testifying. If they are bumbling and fumbling with basic investigative tools, then it’s more likely than not that they will be just as ill-prepared and weak at trial. Additionally, if they are including in their reports the ‘word for word’ language from NHTSA regarding how they administered the field tests, then watch out, you’re certain to have a ‘know-it-all’ at trial that is going to attempt to run way past the question(s) asked. So, take these cues, study their methods and be prepared to use the Rules of Evidence to control them. I know most lawyers don’t want to be viewed as the jerk who is constantly standing up and objecting and disrupting the flow, but if you don’t get ahold of it early it will kill your client in the end. Now to the rules…

I will admit, I too don’t spend as much time as I should re-familiarizing myself with the Rules of Evidence. I mean, I’ve tried a lot of cases and I know them…right? Wrong! Trials are happening every day all over this city, county, State, and country. Witnesses are testifying and lawyers are making objections…or not. Even more importantly, Courts are rendering legal opinions regarding the Rules of Evidence and their applicability during trials, often to the great detriment of criminal defendants. So, let’s all make a more concerted effort to study these incredibly valuable trial tools. Here are a few:

*401-402 / Relevance

*403 / Exclusionary

*404 / Character

*608 / Character for Truthfulness

*609 / Impeachment

9

*611 / Mode of Examining Witnesses

*801-803 / Hearsay

*901 / Authentication of Evidence.

BULLET EIGHT: TIME MANAGEMENT

Yes, just like ‘Attitude’, how you “manage the clock” is a valuable trial tactic! If you don’t believe me, then wait until a Judge excoriates you in front of the Jury for wasting time. It can be a death blow. Remember, as a Criminal Lawyer, you too are often being judged and tried along with your client. From my experience, it’s typically during cross-examination where the anxiety to “wrap it up” increases.

The best way to fend this off and rise above the pressure is to know exactly what you MUST HAVE out of each witness. This applies to direct and crossexamination. Though sometimes you may not achieve the goal, the precision of your methods and questions will make sense to the Judge and Jury. I do this by asking myself during trial preparation the simple questions of “How can I win this case?”…and then if it appears we should win or are winning, “How can I lose?” For example, let’s say I have a case with a really bad video. I do not need to waste time on the oficer’s knowledge of the overall testing protocol and NHTSA, as any laymen / non-oficer can see that something is not normal with my client. Rather, I need to hone in and focus my questions on the areas and moments wherein my client performed well, or the problems with the testing area, or the effects of other factors like fatigue, physical limitations of the client and/or nervousness. If it don’t stick to these possible ‘win’ answers, then I’m just wasting time and, worse, potentially losing credibility with the Jury. Same is true for cases wherein the facts and evidence are in your favor. In those instances, do you really need to waste time pressing the oficer to say your client “passed” the test? The jury can clearly see this is the case. Plus, you run the risk of coming across as a pompous jerk and

10

losing trustworthiness. Lastly, and I know this may sound sacrilege given the current cost of law school, but there are times when you don’t need to ask a single question. I, too, know the story of the famous lawyer who crossed the Records Custodian for 3 days…but please resist the temptation if they cannot hurt you!!!.

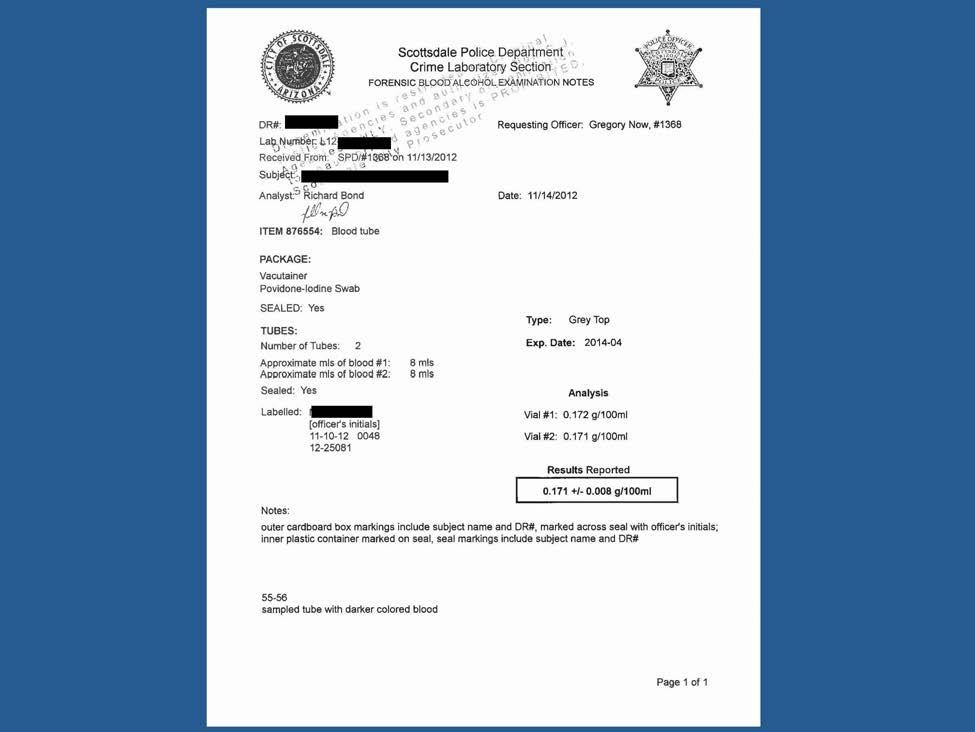

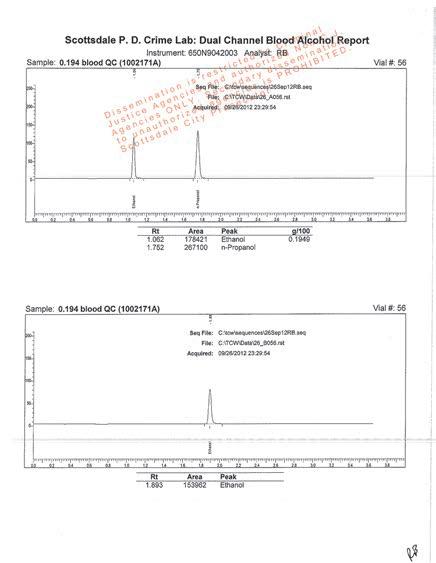

BULLET NINE: 15 MINUTE OBSERVATION PERIOD

Since more and more cases involve the admission of breath and blood test results, I would be remiss in not adding the ’15 Minute Observation Period’ on the list of DWI Defense tactics. Here’s the basics…

DPS Testing Regulations (Operators Manual), as well as the Texas Administrative Code, require that the operator remain in the “continuous presence of the subject at least 15 minutes” before the test is conducted. This is to ensure nothing is placed in the subject’s mouth and/or that nothing happens that could compromise the accuracy of the results (i.e., residual mouth alcohol). Though ‘direct observation’ is not required, proof of compliance with this protocol is still a precondition to admissibility pursuant to testing regulations and Texas case law, and thus subject to attack upon a showing of non-compliance (See above, Art. 38.23). The failure to comply could also give rise to an attack under Kelly - 3rd Prong - as a violation of the requirement that the technique applying the (scientific) theory must have been properly applied on the occasion in question.

Obviously, then, your cross-examination questions need to be narrowly tailored to lock down the time of your client’s actual observation period, versus the time testified by the oficer. This is done by using the police and/or accident report(s), video(s), dispatch records, mobile data terminal (MDT) records, and the breath testing records. If a ‘gap’ or inaccuracy is established, then the results can be suppressed or provide the basis for a ’38.23’ charge. Note, there are quite a few cases on this topic, so read them before the trial if you are going to rely on this

11

tactic. They will provide incredible assistance in fashioning your questions to get the answers you need, as well as help you preserve the record for a future appeal [See, Alvarez v. State, 571 S.W.3d 435 (2019)].

BULLET TEN: “GIVE ME BACK MY SON!”

Mel Gibson may have said this best in his 1996 film, Ransom. “Give me back my son!” Isn’t that what we are really asking? Think of how long it takes to get to trial these days. Add that time to the cost of an Attorney, courthouse parking, and the absurd costs incurred by our clients with bond conditions. In fact, the most common phrase I hear from clients - whether their cases are triable or not - is that they, “just want this over with.” The emotional and financial toll on DWI Defendants these days is REAL. So, use this to your advantage during closing! The State will stand up there with a straight face and talk about the need for crime prevention and sending a message to the community, but is that really even applicable to a Defendant who has waited almost 2 years or more for his/her trial and has paid an interlock company over $60 a month for service and fees? Hell no!

Craft your own way(s) of doing this, but do not shy away from the tactic of highlighting the effect the case has had on your client. Remember, they haven’t been running from anything, as the State always seems to intimate. They have been accountable and ‘not guilty’ since the moment they were pulled over, arrested, and made bond. Frankly, one could and should argue that they have been waiting for this moment the ENTIRE time! If done correctly and with emotion, I believe this plea empowers the jury to do the very things they wore sworn to accomplish: Uphold the constitutional requirement of Presumption of Innocence, stand against the State to ensure Proof beyond all Reasonable Doubt, and render a True verdict!

12

God Speed and Courage!

Todd Overstreet

13

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Speaker:

Ethical Advertising

Brent Mayr

Mayr Law, P.C.

5300 Memorial Dr Ste 750 Houston, TX 77007-8228

713.808.9613 Phone

713.808.9991 Fax

bmayr@mayr-law.com E mail

www.mayr-law.com Website

2023

Whitehall

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

21st Annual Top Gun DWI August 11,

The

Houston, Texas

Changes to the Advertising Rules and What Criminal Defense Lawyers Need to Know

By Brent Mayr

“Dallas DWI Defense, P.L.L.C.” No problem.

Want to give a gift card to your accountant for referring you a client and not worry about the State Bar coming after you? No sweat.

Thinking about posting a video to your social media page reminding viewers they can “politely” invoke their right to remain silent but wondering if you have to submit it to the State Bar for approval? Worry no longer.

These are just a few of the changes that were made to the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct that, although made over a year ago, many criminal defense lawyers are still unaware of. Even more concerning is that some criminal defense lawyers, especially those new to the practice of law, are entirely unaware of the ethical limitations on what they can do and say to promote themselves and let others know about the services they offer.

Now is the time to sit down, earn yourself a quarter hour of self-study ethics credit (one of your three required ethics hours can be self-study), and read up on the new and entirely revised rules on Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation of Business found in Part VII of the Rules. The new and improved rules are meant to simplify, modernize, and clarify the rules, moving us from the old days of Yellow Book advertising to the present and future use of websites, social media, and other new technology used to communicate with one another More importantly, they set out important rules that all criminal defense lawyers need to be aware of in how they promote themselves and bring clients into their offices virtual or otherwise.

From the outset, one of the biggest changes to recognize comes from the decision to make a distinction between ordinary communications, “advertisements,” and “solicitation communications.” The latter two are, by definition, “substantially motivated by pecuniary gain” and thus subject to multiple rules and requirements In the past, there was concern and confusion about something as simple as a new office announcement being subject to those requirements. There were also concerns about lawyers who promoted various forms of non-profit legal services, such as legal aid for the poor. By making the new distinction, lawyers who, for instance, post a comment to social media or promote services not seeking “pecuniary gain,” no longer must worry about complying with disclosure and filing requirements that are applicable to advertisements and solicitation communications.

What remains the same and is still the most important of the rules is that any communication about a lawyer’s services cannot be false or misleading or contain any statement that is false or misleading

This rule, which is rooted in Supreme Court precedent protecting First Amendment rights, is what ultimately gave way to another big change involving law firm names. While in the past, lawyers could only use their name or the names of lawyers who practiced in a firm together as part of their advertised name, with the recent amendments, Texas became the last state in the country to prohibit the use of trade names. Hence, if a lawyer in Dallas whose practice focus is

on DWI cases wanted to rename their firm, “Dallas DWI Defense, P.L.L.C.,” such a name is now permissible. Like with everything else, the name cannot be false or misleading.

As for advertisements themselves, they get their own, new rule: Rule 7.02. While most of the requirements of the rule come from the previous rule dealing with advertisements (old Rule 7.04), it is still worth taking a look at the new rule. What most criminal defense lawyers will immediately recognize is that the rule appears to be geared primarily toward the area of the law where advertising plays a prominent role personal injury law. The rule nevertheless applies to all areas of the law and any criminal defense lawyer producing an advertisement or solicitation communication needs to make sure it complies with this new rule.

One part of the rule that criminal defense lawyers need to pay particular attention to are the limitations of promoting oneself as a criminal defense lawyer in advertisements or solicitation communication. Like before, the new rule allows lawyers to communicate that they practice in a particular area, however, it continues to mandate that a lawyer may “not include a statement that the lawyer has been certified or designated by an organization as possessing special competence or a statement that the lawyer is a member of an organization the name of which implies that its members possess special competence.” The only exceptions for this under the rule are for lawyers that are board certified by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization or members of an organization that has been accredited by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. Presently, the only organization that meets that criteria relevant to criminal defense lawyers is the National College of DUI Defense, Inc.

So what about the host of other lists and organizations that constantly solicit lawyers to be added to their ranks like Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers in America, and countless others? While Texas has not taken on this issue, other states that have considered this issue have issued various, partly inconsistent opinions.1 The American Bar Association attempted to weigh in on the topic but decided that doing so was not necessary and could raise other practical and ethical issues.2 While there is no clear answer on the topic, criminal defense lawyers should be mindful of a few things. First, the most important of the rules still apply: the statement or inclusion on a list or as part of an organization or receipt of an award should not be false and misleading. For instance, one can state they were selected to “Super Lawyers” but cannot promote themselves as a “Super Lawyer.” Second, one should consider the overall validity of the ranking or rating entity. For instance, if the organization appears to make some inquiry into an lawyer’s qualifications or fitness and includes a plain language description of the standard or methodology for the ranking or rating, that might pass muster as opposed to another organization that simply solicits a fee to be included on their “list.” In short, criminal defense lawyers should exercise caution about referencing these entities and the award they offer. After the rule amendments went into effect, the Federal Trade Commission weighed in to warn consumers about lawyers’ inclusion on lists

1 See Roy Simon, “ABA Studies ‘Super,’ ‘Best,’ and Other Lawyer Rankings (Part II),” NEW YORK PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT, October 2011 (available at http://www.newyorklegalethics.com/aba-studies-super-bestand-other-lawyer-rankings-part-ii/) (discussing survey of ethics opinions from around the country).

2 See American Bar Assoc. Commission on Ethics 20/20, Informational Report to the House of Delegates at 14–15 (available at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/ethics_2020/rankings_2011_hod_annual_ meeting_informational_report.pdf).

or as having received certain awards or recognitions that promote themselves as among the best in their field 3

Moving to solicitation and other prohibited communications, the new rule, Rule 7.03, still prohibits in-person solicitation of new clients but also now prohibits “telephone, social media, or electronic communication initiated by a lawyer that involves communication in a live or electronically interactive manner.”

The rule, however, allows communications with “(1) another lawyer; (2) a person who has a family, close personal, or prior business or professional relationship with the lawyer; or (3) a person who is known by the lawyer to be an experienced user of the type of legal services involved for business matters” to solicit business. And, while the rule continues to prohibit paying or giving anything of value to another person for soliciting or referring prospective clients, an exception was added for “nominal gifts given as an expression of appreciation that are neither intended nor reasonably expected to be a form of compensation for recommending a lawyer’s services.”

The final major rule change involves the filing requirements for advertisements and solicitation communications. While most advertisements and solicitation communications still must be submitted to the State Bar for approval, the new rule creates a number of exemptions. The most noteworthy change for criminal defense lawyers applies to websites. Under the new rule, “information and links posted on a law firm website, except the contents of the website homepage,” are exempt from the filing requirements of Rule 7.04, as well as “an announcement card stating new or changed associations, new offices, or similar changes relating to a lawyer or law firm, or a business card.” As for posting on social media and other sources, also exempt from filing is a communication “which does not expressly offer legal services, and that: (1) is primarily informational, educational, political, or artistic in nature, or made for entertainment purposes; or (2) consists primarily of the type of information commonly found on the professional resumes of lawyers.”

Whether your practice is as simple as putting your name on an office door and having a simple website, or as complex as spending thousands of dollars of month to drive in web traffic and phone calls, all criminal defense lawyers should familiarize themselves with these rules and make sure that they and anyone producing any sort of communication promoting their legal services are familiar with them.

Brent Mayr is the managing shareholder of Mayr Law, P.C. based in Houston. He is Board Certified in Criminal Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization, a former briefing attorney to Judge Barbara Hervey on the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and a former Assistant District Attorney for the Harris County District Attorney’s Office. He is presently co-chair of the TCDLA Ethics Committee and a member of the Board of Directors of the Harris County Criminal Lawyers Association. And, yes, he has been named to the Texas Super Lawyers list in Criminal Defense every year since 2014.

3 Emily Wu, “Look beyond the award when you hire a lawyer,” Federal Trade Commission, Consumer Alert, Dec. 16, 2021 (available at https://consumer.ftc.gov/consumer-alerts/2021/12/look-beyond-award-when-you-hirelawyer).

Rule 7.01. Communications Concerning a Lawyer’s Services

(a) A lawyer shall not make or sponsor a false or misleading communication about the qualifications or services of a lawyer or law firm. Information about legal services must be truthful and nondeceptive. A communication is false or misleading if it contains a material misrepresentation of fact or law, or omits a fact necessary to make the statement considered as a whole not materially misleading. A statement is misleading if there is a substantial likelihood that it will lead a reasonable person to formulate a specific conclusion about the lawyer or the lawyer’s services for which there is no reasonable factual foundation, or if the statement is substantially likely to create unjustified expectations about the results the lawyer can achieve.

(b) This Rule governs all communications about a lawyer’s services, including advertisements and solicitation communications. For purposes of Rules 7.01 to 7.06:

(1) An “advertisement” is a communication substantially motivated by pecuniary gain that is made by or on behalf of a lawyer to members of the public in general, which offers or promotes legal services under circumstances where the lawyer neither knows nor reasonably should know that the recipients need legal services in particular matters.

(2) A “solicitation communication” is a communication substantially motivated by pecuniary gain that is made by or on behalf of a lawyer to a specific person who has not sought the lawyer’s advice or services, which reasonably can be understood as offering to provide legal services that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know the person needs in a particular matter.

(c) Lawyers may practice law under a trade name that is not false or misleading. A law firm name may include the names of current members of the firm and of deceased or retired members of the firm, or of a predecessor firm, if there has been a succession in the firm identity. The name of a lawyer holding a public office shall not be used in the name of a law firm, or in communications on its behalf, during any substantial period in which the lawyer is not actively and regularly practicing with the firm. A law firm with an office in more than one jurisdiction may use the same name or other professional designation in each jurisdiction, but identification of the lawyers in an office of the firm shall indicate the jurisdictional limitations on those not licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the office is located.

(d) A statement or disclaimer required by these Rules shall be sufficiently clear that it can reasonably be understood by an ordinary person and made in each language used in the communication. A statement that a language is spoken or understood does not require a statement or disclaimer in that language.

(e) A lawyer shall not state or imply that the lawyer can achieve results in the representation by unlawful use of violence or means that violate these Rules or other law.

(f) A lawyer may state or imply that the lawyer practices in a partnership or other business entity only when that is accurate.

(g) If a lawyer who advertises the amount of a verdict secured on behalf of a client knows that the verdict was later reduced or reversed, or that the case was settled for a lesser amount, the lawyer must state in each advertisement of the verdict, with equal or greater prominence, the amount of money that was ultimately received by the client.

VII. INFORMATION ABOUT LEGAL SERVICES

1. This Rule governs all communications about a lawyer’s services, including firm names, letterhead, and professional designations. Whatever means are used to make known a lawyer’s services, statements about them must be truthful and not misleading. As subsequent provisions make clear, some rules apply only to “advertisements” or “solicitation communications.” A statement about a lawyer’s services falls within those categories only if it was “substantially motivated by pecuniary gain,” which means that pecuniary gain was a substantial factor in the making of the statement.

Misleading Truthful Statements

2. Misleading truthful statements are prohibited by this Rule. For example, a truthful statement is misleading if presented in a way that creates a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person would believe the lawyer’s communication requires that person to take further action when, in fact, no action is required.

Use of Actors

3. The use of an actor to portray a lawyer in a commercial is misleading if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person will conclude that the actor is the lawyer who is offering to provide legal services. Whether a disclaimer such as a statement that the depiction is a “dramatization” or shows an “actor portraying a lawyer” is sufficient to make the use of an actor not misleading depends on a careful assessment of the relevant facts and circumstances, including whether the disclaimer is conspicuous and clear. Similar issues arise with respect to actors portraying clients in commercials. Such a communication is misleading if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person will reach erroneous conclusions based on the dramatization.

Intent to Refer Prospective Clients to Another Firm

4. A communication offering legal services is misleading if, at the time a lawyer makes the communication, the lawyer knows or reasonably should know, but fails to disclose, that a prospective client responding to the communication is likely to be referred to a lawyer in another firm.

Unjustified Expectations

5. A communication is misleading if there is a substantial likelihood that it will create unjustified expectations on the part of prospective clients about the results that can be achieved. A communication that truthfully reports results obtained by a lawyer on behalf of clients or former clients may be misleading if presented so as to lead a reasonable person to form an unjustified expectation that the same results could be obtained for other clients in similar matters without reference to the specific factual and legal circumstances of each client’s case. Depending on the facts and circumstances, the inclusion of an appropriate disclaimer or qualifying language may preclude a finding that a statement is likely to mislead the public.

Required Statements and Disclaimers

6. A statement or disclaimer required by these Rules must be presented clearly and conspicuously such that it is likely to be noticed and reasonably understood by an ordinary person. In radio, television, and Internet advertisements, verbal statements must be spoken in a manner that their content is easily intelligible, and written statements must appear in a size and font, and for a sufficient length of time, that a viewer can easily see and read the statements.

Comment:

7. An unsubstantiated claim about a lawyer’s or law firm’s services or fees, or an unsubstantiated comparison of the lawyer’s or law firm’s services or fees with those of other lawyers or law firms, may be misleading if presented with such specificity as to lead a reasonable person to conclude that the comparison or claim can be substantiated.

Public Education Activities

8. As used in these Rules, the terms “advertisement” and “solicitation communication” do not include statements made by a lawyer that are not substantially motivated by pecuniary gain. Thus, communications which merely inform members of the public about their legal rights and about legal services that are available from public or charitable legal-service organizations, or similar non-profit entities, are permissible, provided they are not misleading. These types of statements may be made in a variety of ways, including community legal education sessions, know-your-rights brochures, public service announcements on television and radio, billboards, information posted on organizational social media sites, and outreach to low-income groups in the community, such as in migrant labor housing camps, domestic violence shelters, disaster resource centers, and dilapidated apartment complexes.

Web Presence

9. A lawyer or law firm may be designated by a distinctive website address, e-mail address, social media username or comparable professional designation that is not misleading and does not otherwise violate these Rules.

Past Success and Results

10. A communication about legal services may be misleading because it omits an important fact or tells only part of the truth. A lawyer who knows that an advertised verdict was later reduced or reversed, or never collected, or that the case was settled for a lesser amount, must disclose the amount actually received by the client with equal or greater prominence to avoid creating unjustified expectations on the part of potential clients. A lawyer may claim credit for a prior judgement or settlement only if the lawyer played a substantial role in obtaining that result. This standard is satisfied if the lawyer served as lead counsel or was primarily responsible for the settlement. In other cases, whether the standard is met depends on the facts. A lawyer who did not play a substantial role in obtaining an advertised judgment or settlement is subject to discipline for misrepresenting the lawyer’s experience and, in some cases, for creating unjustified expectations about the results the lawyer can achieve.

Related Rules

11. It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation. See Rule 8.04(a)(3); see also Rule 8.04(a)(5) (prohibiting communications stating or implying an ability to improperly influence a government agency or official).

Unsubstantiated Claims and Comparisons

(a) An advertisement of legal services shall publish the name of a lawyer who is responsible for the content of the advertisement and identify the lawyer’s primary practice location.

(b) A lawyer who advertises may communicate that the lawyer does or does not practice in particular fields of law, but shall not include a statement that the lawyer has been certified or designated by an organization as possessing special competence or a statement that the lawyer is a member of an organization the name of which implies that its members possess special competence, except that:

(1) a lawyer who has been awarded a Certificate of Special Competence by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization in the area so advertised, may state with respect to each such area, “Board Certified, area of specialization Texas Board of Legal Specialization”; and

(2) a lawyer who is a member of an organization the name of which implies that its members possess special competence, or who has been certified or designated by an organization as possessing special competence in a field of practice, may include a factually accurate, non-misleading statement of such membership or certification, but only if that organization has been accredited by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization as a bona fide organization that admits to membership or grants certification only on the basis of published criteria which the Texas Board of Legal Specialization has established as required for such certification.

(c) If an advertisement by a lawyer discloses a willingness to render services on a contingent fee basis, the advertisement must state whether the client will be obligated to pay for other expenses, such as the costs of litigation.

(d) A lawyer who advertises a specific fee or range of fees for an identified service shall conform to the advertised fee or range of fees for the period during which the advertisement is reasonably expected to be in circulation or otherwise expected to be effective in attracting clients, unless the advertisement specifies a shorter period. However, a lawyer is not bound to conform to the advertised fee or range of fees for a period of more than one year after the date of publication, unless the lawyer has expressly promised to do so.

Comment:

1. These Rules permit the dissemination of information that is not false or misleading about a lawyer’s or law firm’s name, address, e-mail address, website, and telephone number; the kinds of services the lawyer will undertake; the basis on which the lawyer’s fees are determined, including prices for specific services and payment and credit arrangements; a lawyer’s foreign language abilities; names of references and, with their consent, names of clients regularly represented; and other similar information that might invite the attention of those seeking legal assistance.

Rule 7.02. Advertisements

Communications about Fields of Practice

2. Lawyers often benefit from associating with other lawyers for the development of practice areas. Thus, practitioners have established associations, organizations, institutes, councils, and practice groups to promote, discuss, and develop areas of the law, and to advance continuing

education and skills development. While such activities are generally encouraged, participating lawyers must refrain from creating or using designations, titles, or certifications which are false or misleading. A lawyer shall not advertise that the lawyer is a member of an organization whose name implies that members possess special competence, unless the organization meets the standards of Rule 7.02(b). Merely stating a designated class of membership, such as Associate, Master, Barrister, Diplomate, or Advocate, does not, in itself, imply special competence violative of these Rules.

3. Paragraph (b) of this Rule permits a lawyer to communicate that the lawyer practices, focuses, or concentrates in particular areas of law. Such communications are subject to the “false and misleading” standard applied by Rule 7.01 to communications concerning a lawyer’s services and must be objectively based on the lawyer’s experience, specialized training, or education in the area of practice.

4. The Patent and Trademark Office has a long-established policy of designating lawyers practicing before the Office. The designation of Admiralty practice also has a long historical tradition associated with maritime commerce and the federal courts. A lawyer’s communications about these practice areas are not prohibited by this Rule.

Certified Specialist

5. This Rule permits a lawyer to state that the lawyer is certified as a specialist in a field of law if such certification is granted by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization or by an organization that applies standards of experience, knowledge and proficiency to ensure that a lawyer’s recognition as a specialist is meaningful and reliable, if the organization is accredited by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. To ensure that consumers can obtain access to useful information about an organization granting certification, the name of the certifying organization must be included in any communication regarding the certification.

Rule 7.03. Solicitation and Other Prohibited Communications

(a) The following definitions apply to this Rule:

(1) “Regulated telephone, social media, or other electronic contact” means telephone, social media, or electronic communication initiated by a lawyer, or by a person acting on behalf of a lawyer, that involves communication in a live or electronically interactive manner.

(2) A lawyer “solicits” employment by making a “solicitation communication,” as that term is defined in Rule 7.01(b)(2).

(b) A lawyer shall not solicit through in-person contact, or through regulated telephone, social media, or other electronic contact, professional employment from a non-client, unless the target of the solicitation is:

(1) another lawyer;

(2) a person who has a family, close personal, or prior business or professional relationship with the lawyer; or

(3) a person who is known by the lawyer to be an experienced user of the type of legal services involved for business matters.

(c) A lawyer shall not send, deliver, or transmit, or knowingly permit or cause another person to send, deliver, or transmit, a communication that involves coercion, duress, overreaching, intimidation, or undue influence.

(d) A lawyer shall not send, deliver, or transmit, or knowingly permit or cause another person to send, deliver, or transmit, a solicitation communication to a prospective client, if:

(1) the communication is misleadingly designed to resemble a legal pleading or other legal document; or

(2) the communication is not plainly marked or clearly designated an “ADVERTISEMENT” unless the target of the communication is:

(i) another lawyer;

(ii) a person who has a family, close personal, or prior business or professional relationship with the lawyer; or

(iii) a person who is known by the lawyer to be an experienced user of the type of legal services involved for business matters.

(e) A lawyer shall not pay, give, or offer to pay or give anything of value to a person not licensed to practice law for soliciting or referring prospective clients for professional employment, except nominal gifts given as an expression of appreciation that are neither intended nor reasonably expected to be a form of compensation for recommending a lawyer’s services.

(1) This Rule does not prohibit a lawyer from paying reasonable fees for advertising and public relations services or the usual charges of a lawyer referral service that meets the requirements of Texas law.

(2) A lawyer may refer clients to another lawyer or a nonlawyer professional pursuant to an agreement not otherwise prohibited under these Rules that provides for the other person to refer clients or customers to the lawyer, if:

(i) the reciprocal referral agreement is not exclusive;

(ii) clients are informed of the existence and nature of the agreement; and

(iii) the lawyer exercises independent professional judgment in making referrals.

(f) A lawyer shall not, for the purpose of securing employment, pay, give, advance, or offer to pay, give, or advance anything of value to a prospective client, other than actual litigation expenses and other financial assistance permitted by Rule 1.08(d), or ordinary social hospitality of nominal value.

(g) This Rule does not prohibit communications authorized by law, such as notice to members of a class in class action litigation.

Comment:

Solicitation by Public and Charitable Legal Services Organizations

1. Rule 7.01 provides that a “‘solicitation communication’ is a communication substantially motivated by pecuniary gain.” Therefore, the ban on solicitation imposed by paragraph (b) of this Rule does not apply to the activities of lawyers working for public or charitable legal services organizations.

Communications Directed to the Public or Requested

2. A lawyer’s communication is not a solicitation if it is directed to the general public, such as through a billboard, an Internet banner advertisement, a website or a television commercial, or if it is made in response to a request for information, including an electronic search for information. The terms “advertisement” and “solicitation communication” are defined in Rule 7.01(b).

The Risk of Overreaching

3. A potential for overreaching exists when a lawyer, seeking pecuniary gain, solicits a person known to be in need of legal services via in-person or regulated telephone, social media, or other electronic contact. These forms of contact subject a person to the private importuning of the trained advocate in a direct interpersonal encounter. The person, who may already feel overwhelmed by the circumstances giving rise to the need for legal services, may find it difficult to fully evaluate all available alternatives with reasoned judgment and appropriate self‑interest in the face of the lawyer’s presence and insistence upon an immediate response. The situation is fraught with the possibility of undue influence, intimidation, and overreaching.

4. The potential for overreaching that is inherent in in-person or regulated telephone, social media, or other electronic contact justifies their prohibition, since lawyers have alternative means of conveying necessary information. In particular, communications can be sent by regular mail or e-mail, or by other means that do not involve communication in a live or electronically interactive manner. These forms of communications make it possible for the public to be informed about the need for legal services, and about the qualifications of available lawyers and law firms, with minimal risk of overwhelming a person’s judgment.

5. The contents of live person-to-person contact can be disputed and may not be subject to third‑party scrutiny. Consequently, they are much more likely to approach (and occasionally cross) the dividing line between accurate representations and those that are false and misleading.

Targeted Mail Solicitation

6. Regular mail or e-mail targeted to a person that offers to provide legal services that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know the person needs in a particular matter is a solicitation communication within the meaning of Rule 7.01(b)(2), but is not prohibited by subsection (b) of this Rule. Unlike in-person and electronically interactive communication by “regulated telephone, social media, or other electronic contact,” regular mail and e-mail can easily be ignored, set aside, or reconsidered. There is a diminished likelihood of overreaching because no lawyer is physically present and there is evidence in tangible or electronic form of what was communicated. See Shapero v. Kentucky B. Ass’n, 486 U.S. 466 (1988).

Personal, Family, Business, and Professional Relationships

7. There is a substantially reduced likelihood that a lawyer would engage in overreaching against a former client, a person with whom the lawyer has a close personal, family, business or professional relationship, or in situations in which the lawyer is motivated by considerations other than pecuniary gain. Nor is there a serious potential for overreaching when the person contacted is a lawyer or is known to routinely use the type of legal services involved for business purposes. Examples include persons who routinely hire outside counsel to represent an entity; entrepreneurs who regularly engage business, employment law, or intellectual property lawyers; small business proprietors who routinely hire lawyers for lease or contract issues; and other people who routinely retain lawyers for business transactions or formations.

Constitutionally Protected Activities

8. Paragraph (b) is not intended to prohibit a lawyer from participating in constitutionally protected activities of public or charitable legal-service organizations or bona fide political, social, civic, fraternal, employee, or trade organizations whose purposes include providing or recommending legal services to their members or beneficiaries. See In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978).

Group and Prepaid Legal Services Plans

9. This Rule does not prohibit a lawyer from contacting representatives of organizations or entities that may be interested in establishing a group or prepaid legal plan for their members, insureds, beneficiaries, or other third parties. Such communications may provide information about the availability and terms of a plan which the lawyer or lawyer’s firm is willing to offer. This form of communication is not directed to persons who are seeking legal services for themselves. Rather, it is usually addressed to a fiduciary seeking a supplier of legal services for others, who may, if they choose, become prospective clients of the lawyer. Under these circumstances, the information transmitted is functionally similar to the types of advertisements permitted by these Rules.

Designation as an Advertisement

10. For purposes of paragraph (d)(2) of this Rule, a communication is rebuttably presumed to be “plainly marked or clearly designated an ‘ADVERTISEMENT’” if: (a) in the case of a letter transmitted in an envelope, both the outside of the envelope and the first page of the letter state the word “ADVERTISEMENT” in bold face all-capital letters that are 3/8” high on a uncluttered background; (b) in the case of an e-mail message, the first word in the subject line is “ADVERTISEMENT” in all capital letters; and (c) in the case of a text message or message on social media, the first word in the message is “ADVERTISEMENT” in all capital letters.

Paying Others to Recommend a Lawyer

11. This Rule allows a lawyer to pay for advertising and communications, including the usual costs of printed or online directory listings or advertisements, television and radio airtime, domain-name registrations, sponsorship fees, and group advertising. A lawyer may compensate employees, agents, and vendors who are engaged to provide marketing or client development services, such as publicists, public-relations personnel, business-development staff, television and radio station employees or spokespersons, and website designers.

12. This Rule permits lawyers to give nominal gifts as an expression of appreciation to a person for recommending the lawyer’s services or referring a prospective client. The gift may not be more than a token item as might be given for holidays, or other ordinary social hospitality. A gift is prohibited if offered or given in consideration of any promise, agreement, or understanding that such a gift would be forthcoming or that referrals would be made or encouraged in the future.

13. A lawyer may pay others for generating client leads, such as Internet-based client leads, as long as the lead generator does not recommend the lawyer, any payment to the lead generator is consistent with Rule 5.04(a) (division of fees with nonlawyers) and Rule 5.04(c) (nonlawyer interference with the professional independence of the lawyer), and the lead generator’s communications are consistent with Rule 7.01 (communications concerning a lawyer’s services). To comply with Rule 7.01, a lawyer must not pay a lead generator that states, implies, or creates a reasonable impression that it is recommending the lawyer, is making the referral without payment from the lawyer, or has analyzed a person’s legal problems when determining which lawyer should receive the referral. See also Rule 5.03 (duties of lawyers and law firms with respect to the conduct of nonlawyers); Rule 8.04(a)(1) (duty to avoid violating the Rules through the acts of another).

Charges of and Referrals by a Legal Services Plan or Lawyer Referral Service

14. A lawyer may pay the usual charges of a legal services plan or a not-for-profit or qualified lawyer referral service. A legal service plan is a prepaid or group legal service plan or a similar delivery system that assists people who seek to secure legal representation. A lawyer referral service, on the other hand, is any organization that holds itself out to the public as a lawyer referral service. Qualified referral services are consumer-oriented organizations that provide unbiased referrals to lawyers with appropriate experience in the subject matter of the representation and afford other client protections, such as complaint procedures or malpractice insurance requirements.

15. A lawyer who accepts assignments or referrals from a legal service plan or referrals from a lawyer referral service must act reasonably to assure that the activities of the plan or service are compatible with the lawyer’s professional obligations. Legal service plans and lawyer referral services may communicate with the public, but such communication must be in conformity with these Rules. Thus, advertising must not be false or misleading, as would be the case if the communications of a group advertising program or a group legal services plan would mislead the public to think that it was a lawyer referral service sponsored by a state agency or bar association.

Reciprocal Referral Arrangements

16. A lawyer does not violate paragraph (e) of this Rule by agreeing to refer clients to another lawyer or nonlawyer professional, so long as the reciprocal referral agreement is not exclusive, the client is informed of the referral agreement, and the lawyer exercises independent professional judgment in making the referral. Reciprocal referral agreements should not be of indefinite duration and should be reviewed periodically to determine whether they comply with these Rules. A lawyer should not enter into a reciprocal referral agreement with another lawyer that includes a division of fees without determining that the agreement complies with Rule 1.04(f).

Meals or Entertainment for Prospective Clients

17. This Rule does not prohibit a lawyer from paying for a meal or entertainment for a prospective client that has a nominal value or amounts to ordinary social hospitality.

Rule 7.04. Filing Requirements for Advertisements and Solicitation Communications

(a) Except as exempt under Rule 7.05, a lawyer shall file with the Advertising Review Committee, State Bar of Texas, no later than ten (10) days after the date of dissemination of an advertisement of legal services, or ten (10) days after the date of a solicitation communication sent by any means:

(1) a copy of the advertisement or solicitation communication (including packaging if applicable) in the form in which it appeared or will appear upon dissemination;

(2) a completed lawyer advertising and solicitation communication application; and

(3) payment to the State Bar of Texas of a fee authorized by the Board of Directors.

(b) If requested by the Advertising Review Committee, a lawyer shall promptly submit information to substantiate statements or representations made or implied in an advertisement or solicitation communication.

(c) A lawyer who desires to secure pre-approval of an advertisement or solicitation communication may submit to the Advertising Review Committee, not fewer than thirty (30) days prior to the date of first dissemination, the material specified in paragraph (a), except that in the case of an advertisement or solicitation communication that has not yet been produced, the documentation will consist of a proposed text, production script, or other description, including details about the illustrations, actions, events, scenes, and background sounds that will be depicted. A finding of noncompliance by the Advertising Review Committee is not binding in a disciplinary proceeding or action, but a finding of compliance is binding in favor of the submitting lawyer as to all materials submitted for pre-approval if the lawyer fairly and accurately described the advertisement or solicitation communication that was later produced. A finding of compliance is admissible evidence if offered by a party.

Comment:

1. The Advertising Review Committee shall report to the appropriate disciplinary authority any lawyer whom, based on filings with the Committee, it reasonably believes disseminated a communication that violates Rules 7.01, 7.02, or 7.03, or otherwise engaged in conduct that raises a substantial question as to that lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness as a lawyer in other respects. See Rule 8.03(a).

2. Paragraph (a) does not require that a lawyer submit a copy of each written solicitation letter a lawyer sends. If the same form letter is sent to several persons, only a representative sample of each form letter, along with a representative sample of the envelopes used to mail the letters, need be filed.

Requests for Additional Information

3. Paragraph (b) does not empower the Advertising Review Committee to seek information from a lawyer to substantiate statements or representations made or implied in communications about legal services that were not substantially motivated by pecuniary gain.

Rule 7.05. Communications Exempt from Filing Requirements

The following communications are exempt from the filing requirements of Rule 7.04 unless they fail to comply with Rules 7.01, 7.02, and 7.03:

(a) any communication of a bona fide nonprofit legal aid organization that is used to educate members of the public about the law or to promote the availability of free or reduced-fee legal services;

(b) information and links posted on a law firm website, except the contents of the website homepage, unless that information is otherwise exempt from filing;

(c) a listing or entry in a regularly published law list;

(d) an announcement card stating new or changed associations, new offices, or similar changes relating to a lawyer or law firm, or a business card;

(e) a professional newsletter in any media that it is sent, delivered, or transmitted only to:

(1) existing or former clients;

(2) other lawyers or professionals;

(3) persons known by the lawyer to be experienced users of the type of legal services involved for business matters;

(4) members of a nonprofit organization which has requested that members receive the newsletter; or

(5) persons who have asked to receive the newsletter;

(f) a solicitation communication directed by a lawyer to:

(1) another lawyer;

(2) a person who has a family, close personal, or prior business or professional relationship with the lawyer; or

(3) a person who is known by the lawyer to be an experienced user of the type of legal services involved for business matters;

Multiple Solicitation Communications

(g) a communication in social media or other media, which does not expressly offer legal services, and that:

(1) is primarily informational, educational, political, or artistic in nature, or made for entertainment purposes; or

(2) consists primarily of the type of information commonly found on the professional resumes of lawyers;

(h) an advertisement that:

(1) identifies a lawyer or a firm as a contributor or sponsor of a charitable, community, or public interest program, activity, or event; and

(2) contains no information about the lawyers or firm other than names of the lawyers or firm or both, location of the law offices, contact information, and the fact of the contribution or sponsorship;

(i) communications that contain only the following types of information:

(1) the name of the law firm and any lawyer in the law firm, office addresses, electronic addresses, social media names and addresses, telephone numbers, office and telephone service hours, telecopier numbers, and a designation of the profession, such as “attorney,” “lawyer,” “law office,” or “firm;”

(2) the areas of law in which lawyers in the firm practice, concentrate, specialize, or intend to practice;

(3) the admission of a lawyer in the law firm to the State Bar of Texas or the bar of any court or jurisdiction;

(4) the educational background of the lawyer;

(5) technical and professional licenses granted by this state and other recognized licensing authorities;

(6) foreign language abilities;

(7) areas of law in which a lawyer is certified by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization or by an organization that is accredited by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization;

(8) identification of prepaid or group legal service plans in which the lawyer participates;

(9) the acceptance or nonacceptance of credit cards;

(10) fees charged for an initial consultation or routine legal services;

(11) identification of a lawyer or a law firm as a contributor or sponsor of a charitable, community, or public interest program, activity or event;

(12) any disclosure or statement required by these Rules; and

(13) any other information specified in orders promulgated by the Supreme Court of Texas.

Comment:

1.This Rule exempts certain types of communications from the filing requirements of Rule 7.04. Communications that were not substantially motivated by pecuniary gain do not need to be filed.

Website-Related Filings

2. While the entire website of a lawyer or law firm must be compliant with Rules 7.01 and 7.02, the only material on the website that may need to be filed pursuant to this Rule is the contents of the homepage. However, even a homepage does not need to be filed if the contents of the homepage are exempt from filing under the provisions of this Rule. Under Rule 7.04(c), a lawyer may voluntarily seek pre-approval of any material that is part of the lawyer’s website.

Rule 7.06. Prohibited Employment

(a) A lawyer shall not accept or continue employment in a matter when that employment was procured by conduct prohibited by Rules 7.01 through 7.03, 8.04(a)(2), or 8.04(a)(9), engaged in by that lawyer personally or by another person whom the lawyer ordered, encouraged, or knowingly permitted to engage in such conduct.

(b) A lawyer shall not accept or continue employment in a matter when the lawyer knows or reasonably should know that employment was procured by conduct prohibited by Rules 7.01 through 7.03, 8.04(a)(2), or 8.04(a)(9), engaged in by another person or entity that is a shareholder, partner, or member of, an associate in, or of counsel to that lawyer’s firm; or by any other person whom the foregoing persons or entities ordered, encouraged, or knowingly permitted to engage in such conduct.

(c) A lawyer who has not violated paragraph (a) or (b) in accepting employment in a matter shall not continue employment in that matter once the lawyer knows or reasonably should know that the person procuring the lawyer’s employment in the matter engaged in, or ordered, encouraged, or knowingly permitted another to engage in, conduct prohibited by Rules 7.01 through 7.03, 8.04(a)(2), or 8.04(a)(9) in connection with the matter unless nothing of value is given thereafter in return for that employment.

Comment:

1. This Rule deals with three different situations: personal disqualification, imputed disqualification, and referral-related payments.

Personal Disqualification

2. Paragraph (a) addresses situations where the lawyer in question has violated the specified advertising rules or other provisions dealing with serious crimes and barratry. The Rule makes clear that the offending lawyer cannot accept or continue to provide representation. This prohibition also applies if the lawyer ordered, encouraged, or knowingly permitted another to violate the Rules in question.

Imputed Disqualification

3. Second, paragraph (b) addresses whether other lawyers in a firm can provide representation if a person or entity in the firm has violated the specified advertising rules or other provisions dealing with serious crimes and barratry, or has ordered, encouraged, or knowingly permitted another to engage in such conduct. The Rule clearly indicates that the other lawyers cannot provide representation if they knew or reasonably should have known that the employment was procured by conduct prohibited by the stated Rules. This effectively means that, in such cases, the disqualification that arises from a violation of the advertising rules and other specified provisions is imputed to other members of the firm.

Restriction on Referral-Related Payments

4. Paragraph (c) deals with situations where a lawyer knows or reasonably should know that a case referred to the lawyer or the lawyer’s law firm was procured by violation of the advertising rules or other specified provisions. The Rule makes clear that, even if the lawyer’s conduct did not violate paragraph (a) or (b), the lawyer can continue to provide representation only if the lawyer does not pay anything of value, such as a referral fee, to the person making the referral.

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

21st Annual Top Gun DWI

August 11, 2023

The Whitehall

Houston, Texas

Ethical Fees & Agreements

Speaker: Troy McKinney

Schneider & McKinney, P.C.

5300 Memorial Drive Houston, TX 77007

713.951.9994 phone

wtmhousto2@aol.com email

https://texascriminaldefenselawyers.com/ website

Author: The Professional Ethics Committee for the State Bar of Texas

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

THE PROFESSIONAL ETHICS COMMITTEE FOR THE STATE BAR OF TEXAS

Opinion No. 611

September 2011

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is it permissible under the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct for a lawyer to include in an employment contract an agreement that the amount initially paid by a client with respect to a matter is a “non-refundable retainer” that includes payment for all the lawyer’s services on the matter up to the time of trial?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A lawyer proposes to enter into an employment agreement with a client providing that the client will pay at the outset an amount denominated a “non-refundable retainer” that will cover all services of the lawyer on the matter up to the time of any trial in the matter. The proposed agreement also states that, if a trial is necessary in the matter, the client will be required to pay additional legal fees for services at and after trial. The lawyer proposes to deposit the client’s initial payment in the lawyer’s operating account.

DISCUSSION

Rule 1.04(a) of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct provides that a lawyer shall not enter an arrangement for an illegal or unconscionable fee and that a fee is unconscionable “if a competent lawyer could not form a reasonable belief that the fee is reasonable.” Rule 1.04(b) sets forth certain factors that may be considered, along with any other relevant factors not specifically listed, in determining the reasonableness of a fee for legal services. In the case of a non-refundable retainer, the factor specified in Rule 1.04(b)(2) is of particular relevance: “the likelihood, if apparent to the client, that the acceptance of the particular employment will preclude other employment by the lawyer . . . .”

Rule 1.14 deals in part with a lawyer’s handling of funds belonging in whole or in part to the client and requires that such funds when held by a lawyer be kept in a “trust” or “escrow” account separate from the lawyer’s operating account.

Two prior opinions of this Committee have addressed the relationship between the rules now embodied in Rules 1.04 and 1.14.

In Professional Ethics Committee Opinion 391 (February 1978), this Committee concluded that an advance fee denominated a “non-refundable retainer” belongs entirely

-

-

1

to the lawyer at the time it is received because the fee is earned at the time the fee is received and therefore the non-refundable retainer may be placed in the lawyer’s operating account. Opinion 391 also concluded that an advance fee that represents payment for services not yet rendered and that is therefore refundable belongs at least in part to the client at the time the funds come into the possession of the lawyer and, therefore, the amount paid must be deposited into a separate trust account to comply with the requirements of what is now Rule 1.14(a). Opinion 391 concluded further that, when a client provides to a lawyer one check that represents both a non-refundable retainer and a refundable advance payment, the entire check should be deposited into a trust account and the funds that represent the non-refundable retainer may then be transferred immediately into the lawyer’s operating account

This Committee addressed non-refundable retainers again in Opinion 431 (June 1986). Opinion 431 concluded that Opinion 391 remained viable and that non-refundable retainers are not inherently unethical “but must be utilized with caution.” Opinion 431 additionally concluded that Opinion 391 was overruled “to the extent that it states that every retainer designated as non-refundable is earned at the time it is received.” Opinion 431 described a non-refundable retainer (sometimes referred to in Opinion 431 as a “true retainer”) in the following terms:

“A true [non-refundable] retainer, however, is not a payment for services. It is an advance fee to secure a lawyer's services, and remunerate him for loss of the opportunity to accept other employment. . . . . If the lawyer can substantiate that other employment will probably be lost by obligating himself to represent the client, then the retainer fee should be deemed earned at the moment it is received. If, however, the client discharges the attorney for cause before any opportunities have been lost, or if the attorney withdraws voluntarily, then the attorney should refund an equitable portion of the retainer.”

Thus a non-refundable retainer (as that term is used in this opinion) is not a payment for services but is rather a payment to secure a lawyer’s services and to compensate him for the loss of opportunities for other employment. See also Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App.-Austin 2007, no pet.).

It is important to note that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct do not prohibit a lawyer from entering into an agreement with a client that requires the payment of a fixed fee at the beginning of the representation. The Committee also notes that the term “non-refundable retainer,” as commonly used to refer, as in this opinion, to an initial payment solely to secure a lawyer's availability for future services, may be misleading in some circumstances. Opinion 431 recognized in the excerpt quoted above that a retainer solely to secure a lawyer’s future availability, which is fully earned at the time received, would nonetheless have to be refunded at least in part if the lawyer were discharged for cause after receiving the retainer but before he had lost opportunities for other employment or if the lawyer withdrew voluntarily. However, the fact that an amount received by a lawyer as a true non-refundable retainer may later in certain

- 2 -

unusual circumstances have to be at least partially refunded does not negate the fact that such amount has been earned and under the Texas Disciplinary Rules may be deposited in the lawyer’s operating account rather than being subject to a requirement that the amount must be held in a trust or escrow account.