3 CHAPTER MARKET MECHANISM

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

After reading this chapter, students will be able to:

1. Explain basic and broader definitions of a market.

2. Understand the law of supply and demand and the factors influencing supply and demand.

3. Determine market equilibrium and analyse shifts in market equilibrium and their implications on the society.

4. Assess market efficiency through consumer and producer surplus.

Story # 4: Silk sarees!

Rita visited the local market one day to buy sarees for her cousin’s wedding. She had a specific design and budget in mind. After looking around, she found a few beautiful silk saree that caught her attention but were over budget. Sensing her interest, the shopkeeper, Dayal, explained the unique features of silk sarees in his shop, mentioning they were handwoven and directly sourced from weavers in Varanasi.

Rita expressed her budget concerns; understanding her situation, Dayal offered a small discount, saying, “For you, I’ll make an exception.” They agreed on a price that was a win-win for both. Rita was happy to get the three sarees she wanted within her budget, and Dayal was pleased to have made a profitable sale while considering the customer’s budget. This experience made Rita happy to get beautiful sarees within her price range and generated some earnings for Dayal.

In the previous chapter, we learned that exchange creates surplus. In this chapter, we will learn about the market where this exchange occurs and how people exchange goods and services and settle on a price and quantity.

3.1 MARKET IN GENERAL

A market is a place or platform where goods and services are exchanged

through economic transactions between buyers and sellers. The self-interest of the economic agents makes them buy and sell goods & services to benefit from these exchanges. The market can be a physical location, such as a shop in a mall for mobile phones, or it can also be a virtual space, an online platform like Amazon, to buy mobile phones. Microeconomics study of markets, focuses on the behaviour of individual markets and how buying and selling actions can impact the allocation and distribution of scarce resources within the same market and potentially in other related markets.

3.2 MARKET IN LEGAL CONTEXT

For legal studies, understanding the market is not limited to conventional economic transactions. A law student must study a multidimensional view of the market. Market, from a broader perspective, is the interaction among the people of society, among family members, between two neighbours for the car parking lot, between two motor vehicle drivers going in opposite directions, and between individuals and the environment. In a narrow understanding of the market price regulates behaviours and decision-making in economic transactions. In a broader understanding of the market, we see the costs and benefits of any activities performed by the state or individuals (social, anti-social, legal, illegal, criminal, etc). Therefore, understanding how market forces work from economic approach is very important for law students, especially when it’s about how people interact and why someone might choose to break the law or not.

This broad view helps lawyers and state understand the economic background of the cases better. It also helps them predict what might happen next, plan their moves, and formulate government policies promoting economic efficiency and equity.

3.3

DEMAND

Story # 5: A Day of Refreshments

Khushi is at a theme park on a hot day. She feels very thirsty; she needs water to stay hydrated, which is essential for survival. Suddenly, she sees a cold drink shop, and now, instead of water, she wants lemon soda to quench her thirst. Her friend Molly reminded her of the side-effects of cold drinks and gave her a water bottle to drink and quench her thirst. After some time, they both desired a mango smoothie, so they saw a smoothie shop and Molly decided to buy one. Khushi didn’t want to spend money on a smoothie cup, so she saved money to buy something else.

The simple story above defines demand and explains how it differs from need, want, and desire.

(

i) Water is the Need: Khushi needs water to stay hydrated, especially on a hot day. It’s essential for survival. The need is a basic requirement for life.

(ii) A cold drink is a Want - While she needs to stay hydrated, she might want a cold drink instead of water. It’s not essential for survival, but she prefers it over water for refreshment. A want is not a basic need but something more than that. A cold drink is a want for khushi.

(

iii) Desire - It’s a special craving; maybe it is their favourite or has ingredients they love. Desire is an even more specific and stronger feeling of wanting something. Mango smoothie is a desire for Khushi.

(

iv) Molly has the money and willingness to buy the mango smoothie, which creates demand. Demand combines desire, ability, and willingness to buy. Note that Khushi has desire and ability, but doesn’t create demand for mango smoothies as she is not ready to part with her money. Therefore, there is no willingness to buy for mango smoothie for Khushi.

Demand for a particular product is the ability and willingness to buy the good at different prices in a given time period, ceteris paribus. Technically, it is the ‘buying behaviour’ of the consumers for the goods in question at different prices. Ceteris paribus is commonly used in economics to denote a condition under which only one variable is changed at a time, allowing for clearer cause-and-effect analysis. The word ceteris paribus originates from Latin, meaning “all other things being equal” or “holding other things constant.” It helps to identify the precise relationship between two variables with respect to each other while holding other relevant factors constant.

3.3.1

Individual Demand and Market Demand

Individual demand is the willingness and ability of an individual or household to purchase a specific good. It reflects the individual’s willingness to buy, keeping other things given and constant. For example, as per Table 3.1 of the demand schedule, Rasika is willing to buy two ice cream cones for forty rupees, four cones for twenty rupees, ten cones for zero rupees, and so on; this is her demand for ice cream cones at different prices. Market demand on the other hand represents the sum of all individual demands for a good. The market demand for vanilla ice cream cones at forty rupees is fourteen, which includes the quantity demanded by all the individuals in the market; at twenty rupees, it is nineteen; and so on.

3.3.2

Demand Schedule and Demand Curve

Individual demand and market demand can be depicted with the help of a demand schedule and demand curve. Table 3.1 illustrates the demand schedule for Vanilla ice cream cones by Rasika, Kritika, Sanjay, and Sandeep. Assume that there are only four consumers in the market for ice cream ones.

At ` 80, the quantity demanded for Rasika and Sandeep is zero; Kritika demanded one, and Sanjay demanded two cones. The total market demand for ice cream cones at ` 80 is three ice cream cones. Summing up all the individual demands for ice cream cones, we get the market demand at each price. As the price drops to ` 60, Rasika’s demand increases to one cone, Kritika’s demand goes up to two cones, Sanjay’s to four cones, and Sandeep’s to one cone, totalling a market demand of eight cones.

Lastly, when the price drops to ` 0, meaning the ice-cream cones are free, the demand hits its peak: Rasika demands ten cones, Kritika six, Sanjay nine, and Sandeep seven, making it a total market demand of 32 cones. Remember that no one can eat unlimited ice cream, even if it is free; therefore some finite units are consumed at zero price.

A picture speaks a thousand words, and so do the graphs. The following are the graphical representation of the individual and market demand curve.

TABLE 3.1 Demand for Vanilla Ice-Cream Cones

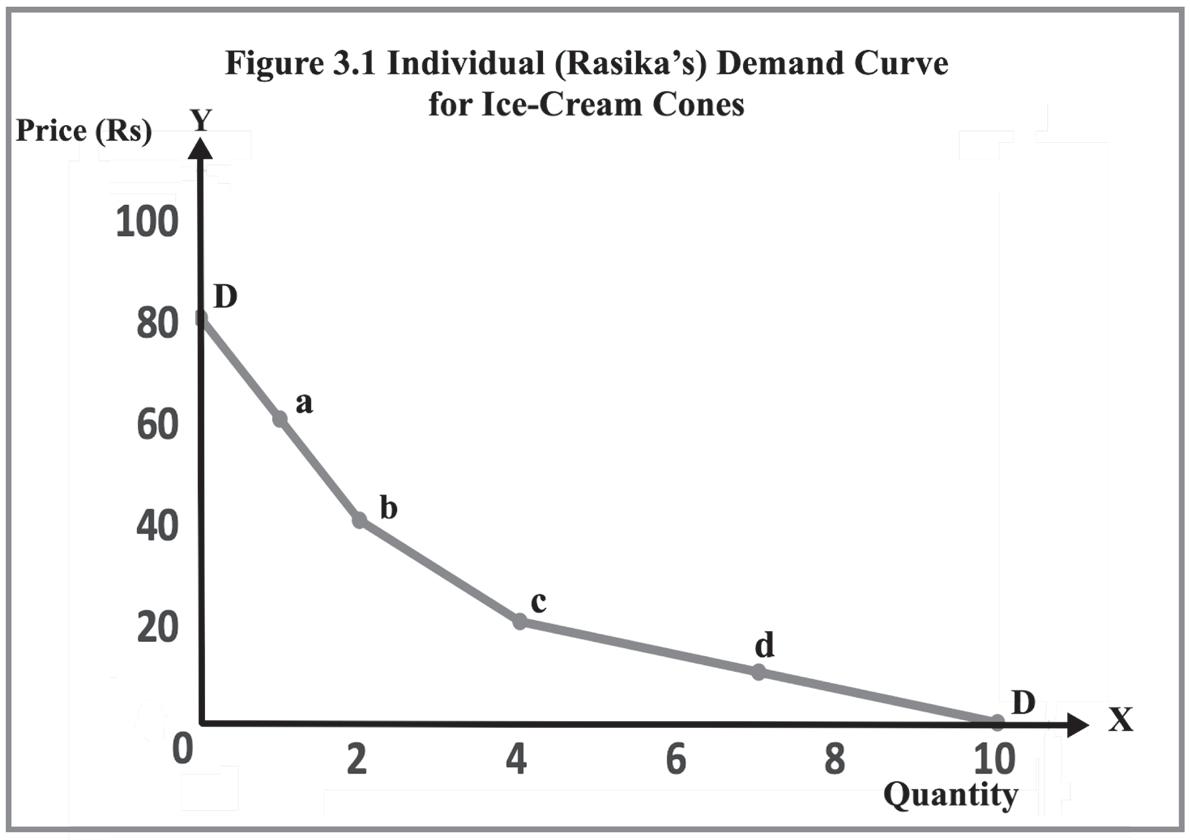

Figure 3.1 depicts Rasika’s demand for vanilla ice cream cones. On the vertical axis, the price is measured, and on the horizontal axis, the quantity of ice cream cones is measured. Rasika is not buying ice cream cones at a price of ` 80 or above. Similarly, she can have ten ice cream cones at a zero price. The demand curve DD slopes downward from left to right because Rasika wants to consume more ice cream cones only if the price falls and vice versa.

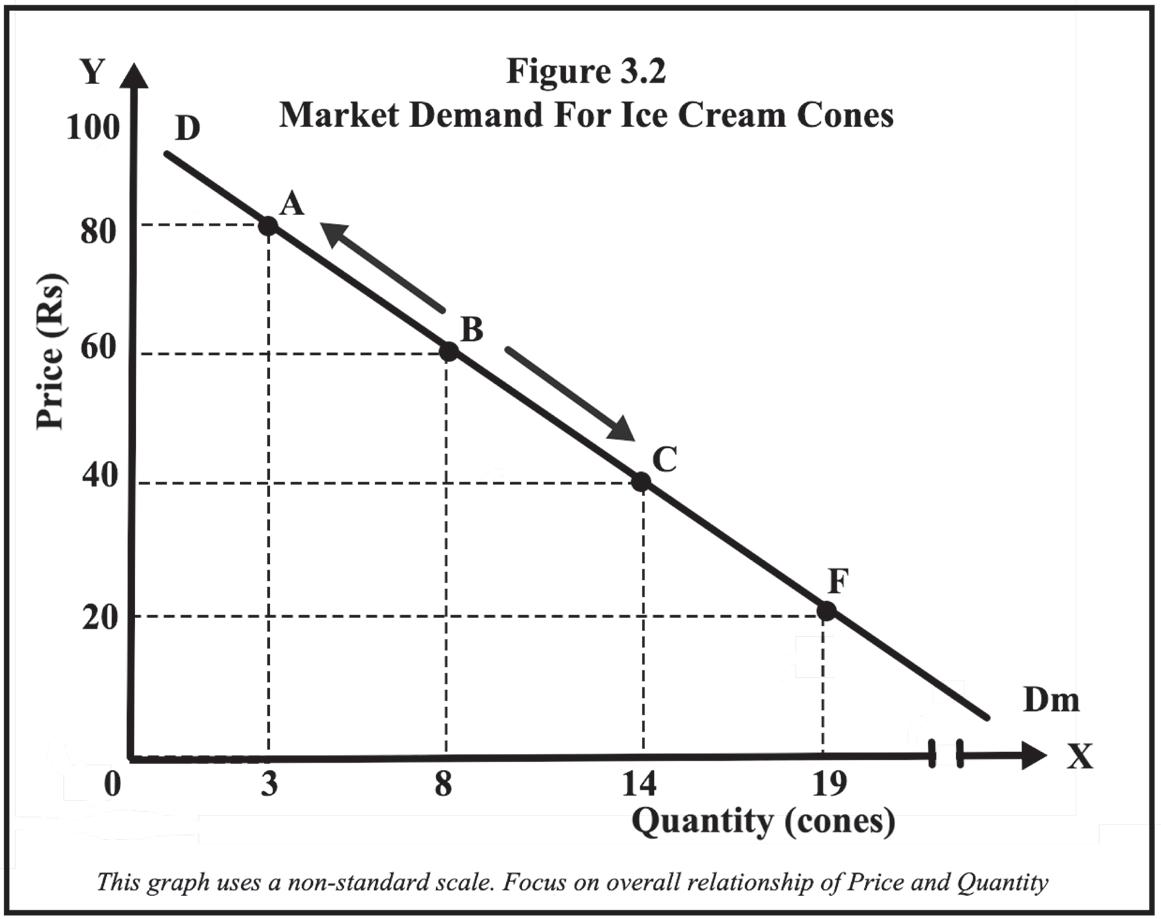

Figure 3.2 shows the market demand curve DDm for vanilla ice cream cones. Like Rasika and other consumers’ individual demand curves, the market demand curve also has a downward slope. The market demand curve is the horizontal summation of all individual demand curves.

The price of ice cream cones is mentioned on the vertical axis, and the quantity of ice cream cones is on the horizontal axis. We can observe that the negative slope of DDm says that at higher prices, less quantity is demanded; and at lower prices, more quantity is demanded. When the price was ` 80, only three cones were demanded; when the price fell to ` 20, the quantity demanded of ice cream cones increased to nineteen.

3.3.3

Law of Demand

The law of demand expresses the relationship between price and quantity demanded, ceteris paribus. If you go to a market, you will observe that consumers are interested in buying more quantity if the price of that good is lower and buying less if the price is higher. This happens to us also all the time, except in some rare cases (exceptions).

ECONOMICS FOR LAW

The law of demand states that “there is an inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of a good.” When the price of a good rises, the quantity demanded falls, and vice versa. The “law” mentioned here does not refer to any legal term but rather to the natural behaviour of humans that consumers tend to exhibit. Here, price is an independent variable, and quantity demanded for the good is dependent. Price acts as an incentive for economic agents in their decision-making. Higher prices disincentivise the buyers, and they buy less, whereas lower prices give more incentives to buy the good.

Figure 3.1 shows Rasika’s demand for ice cream cones; the demand curve has a negative slope because of the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded.

Why does the demand curve slope downwards? The inverse relationship between the price of a good and its quantity demanded is due to the substitution and income effect of the fall/rise in prices and the law of diminishing marginal utility.

The demand schedule in Table 3.1 and the demand curve in Figures 3.1 and 3.2 illustrate the law of demand. As the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded for that good increases, both individually and for the overall market of that good.

Substitution effect: When the price of a good decreases, it becomes less expensive compared to other substitute goods. This leads consumers to increase the quantity demanded for this good over alternatives, which are now relatively more costly. Suppose the price of jaggery powder per kilogram reduces while the price of sugar remains the same. Consumers who previously purchased sugar as a sweetener for their tea may now prefer to buy jaggery instead. This shift in preference could lead to an increase in the quantity of jaggery demanded. As a result, more people might start buying jaggery powder in larger quantities as a substitute for sugar. On the contrary, the opposite happens when the price of jaggery increases; sugar becomes comparatively cheaper, causing people to buy less jaggery and more sugar.

Real Income Effect: A fall in the price of a good increases the real purchasing power of consumers. This is due to an increase in the real income of the consumers, where the same amount of money can buy more units than before. Similarly, increasing prices make consumers poorer as the same amount of money can buy fewer units than before, reducing the quantity of goods they can afford.

Another reason is the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility because as consumers buy more units of a good, the satisfaction (utility) gained from consuming each additional unit decreases. Therefore, individuals are only willing to purchase additional units if the price decreases, as they assign a lower value to the additional units. One of the reasons

behind inverse relationship between Price and quantity demanded is diminishing marginal utility, which is explained in chapter five of this book.

Exceptions to the Law of Demand:

The law of demand states the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. But sometimes with an increase in the price of the goods, the quantity demanded increases.

There are some commodities identified as ‘Giffen Goods’ for which demand goes up when prices rise and drops when prices fall. This unusual behaviour was noted by the economist Robert Giffen, who lived from 1837 to 1910. He observed that when the price of bread went up, poor people, who depended on it as a main part of their diet, could not afford to buy more expensive foods. As a result, they had to buy even more bread. On the other hand, when the price of bread decreased, it was like they had more money to spend, so they could buy normal food instead of just bread. All the Giffen goods are inferior goods, but not all inferior goods are Giffen goods.

We also have ‘Veblen Goods’ that don’t follow the law of supply and demand, because their quantity demanded goes up when the price increases. This is connected to the idea of conspicuous consumption, a term introduced by Thorstein Veblen in his book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). These goods are bought not because they fulfil any practical needs, but to fulfil a psychological desire for social approval and to impress others. Rich people often buy Veblen goods as status symbols, aiming to keep up with their neighbours or peers.

3.3.4

Determinants of Demand

The willingness of consumers to buy is expressed as their demand for a specific good, keeping other factors constant. This idea means we think everything else stays the same while looking precisely associated with the demand as the relationship between the price of a good and its quantity demanded in the market. Consumers’ willingness to buy goods and services can change because of different factors around them. When these factors change, consumers’ willingness to buy also changes. All factors that tend to change the consumer’s buying behaviour towards a particular good are called determinants of demand or factors affecting demand.

The following are major determinants of demand:

(i)

Income of the Consumers

The income of the consumers is one of the most prominent determinants of demand for a good. The amount of money people make is really important in deciding whether they want to buy something. Whether an increase in income leads to an increase in the demand for a good in the market depends

on whether the good is normal or inferior. A normal good is one for which demand increases as income increases. If the demand for a good decreases as consumer’s income increases, that good is considered inferior

A few Examples of normal goods are:

Organic Foods: As income increases, people often choose higherquality, healthier options, which are typically priced higher.

New Cars: With increased income, people prefer buying new or luxury cars instead of used ones.

Designer Clothing: With increased income, some may prefer buying branded items or high-end fashion.

Electronics: Higher disposable income tends to increase the demand for the latest gadgets and technology.

Travel and Vacation: People with the increase in their incomes are more likely to spend on leisure and luxurious vacations.

A few Examples of inferior goods may be

Candles or kerosene oil for lighting the house: Candles or kerosene oil as the lighting sources are considered inferior because, as people’s incomes rise, they tend to buy more modern lighting solutions, reducing their reliance on candles for illumination.

Used Cars: As consumers’ income rises, they might prefer to buy new cars instead of used ones. Therefore, from this perspective, used cars can be considered an inferior good for most of the people.

(ii) Prices of Related Goods

Other things being equal, the price of related goods can impact the demand for a specific good. Related goods are the goods that are somehow linked to the good in question. There are two types of related goods: substitute goods and complementary goods.

A substitute good is a product or service that a consumer sees as equivalent or replaceable with another. For example, tea & coffee, oranges & kinnow fruit, soft drink & lemonade, bus ride & train, etc. The interchangeability of goods or services depends on how easily one can be replaced by another. This replacement capability mainly depends on two factors. First, it’s about how similar or close substitutes the items in question are. If two products serve the same need or function in almost indistinguishable ways, they’re considered close substitutes, making them highly interchangeable. The second is how the market is defined. If the market is defined in a narrow sense with specific needs, the degree of substitutability might be lower because the products are tailored to meet those precise requirements, making it hard

to find a perfect substitute. For example, if we only consider the market for two-wheeler motor vehicles, we will have only two options: scooters and motorbikes. If the market, on the other hand, is broadly defined, serving a general purpose, products are more likely to be interchangeable. For example, if we study the market for vehicles to commute from one destination to another within the city, many vehicles will be considered substitutes for each other, from bicycles to buses as a mode of commute.

De ning and understanding the relevant market is a very important concept in the economic analysis of competition law, as it helps in deciding the substitutability of a good in the market and whether there is competition in the market for that good or not.

When the price of a substitute good increases, the demand for the good in question increases and vice versa. Essentially, if the price of one product rises, consumers are more likely to purchase its substitute, assuming the substitute’s price remains unchanged. There is a direct relationship between the price of substitutes and the demand for the good. For example, if the price of coffee increases, some people might switch to tea, considering it a suitable alternative. Thus, we see that with the increase in the price of coffee, the demand for tea increases and with decreases in the price of coffee, people would prefer more coffee over tea. Therefore, we see that the reduction in the price of coffee, which is a substitute for tea, decreases the demand for tea.

A complementary good is a product or service that a consumer uses with another product or service. A complementary good pair with the good in question and enhances its utility. For example, smartphones as a good, has apps as its complements. Other examples are Tea and milk, cars and petrol, TV and sound systems, etc.

When the price of complementary goods increases, the demand for the main good decreases, reflecting an inverse relationship between the price of complementary goods and the demand for the good. For example, if the price of petrol increases, owners of petrol cars may shift to public transport to reduce the quantity demanded for petrol and therefore reduce the use of cars. Similarly, the potential buyers of cars may not prefer to buy petrol cars due to increase in the price of petrol.

(iii)

Taste and Preferences

Consumer tastes and preferences significantly influence market demand. As individual tastes and preferences shift, there is a corresponding change in the demand for various goods and services. These shifts can result from cultural trends, technological innovations, marketing strategies, changes in consumer lifestyles, and government regulations. For instance, in the

fashion industry, the growing popularity of vintage clothing drives up demand for vintage cloths. A rise in consumer preference for eco-friendly and sustainable goods leads to higher demand for these products. Similarly, an increased preference for nutritious, organic foods and meat alternatives boosts demand for healthier food.

The pandemic of 2020 has escalated the need for online classes, increasing demand for smartphones and internet connections. Implementing mandatory helmet laws for pillion riders also raises the market demand for helmets. Research revealing the adverse health effects of certain edible oils results in decreased demand for these oils and increased demand for their better substitutes. Therefore, any factor changing the tastes and preferences of consumers can determine demand for a good or services under the category of taste and preferences.

(iv)

Future Price Expectations

Future price expectations can significantly influence consumer behaviour in the market. For instance, if individuals anticipate a decrease in tax rates in the upcoming financial year, they might postpone purchasing a vehicle in the present year, hoping that car prices will decrease after the union budget. This expectation can also be observed at gas stations, where consumers might rush to fill their tanks if they predict price hikes due to potential budgetary adjustments or geopolitical tensions affecting the petrol supply. Therefore, Expectations of a future decrease in the price of a good will decrease the current market demand, and expectations of a price increase will increase the current demand for a good.

(v) Changes in Population and Demography

Population change can bring a change in demand. An increase in population can increase the market demand for a good, and a decrease in population will decrease the demand. Change in demography also plays a vital role as a determinant of demand. The baby boomer generation provides an excellent example of how changes in population and demography can influence demand.

After World War II, from 1946 to 1964, there was a significant increase in birth rates in America, creating this generation known as the baby boomers.1 During their early years, there was a surge in demand for baby products, such as diapers and baby food. The education sector expanded as they entered school age, requiring more schools and educational materials. In their adult years, the housing market boomed, and there was increased demand

1. Slepian, R. C., Vincent, A. C., Patterson, H., & Furman, H. (2024). Social media, wearables, telemedicine and digital health: A Gen Y and Z perspective. In K. S. Ramos (Ed.), Comprehensive Precision Medicine (1st ed., pp. 524-544). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-89636-7. https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824010-6.00072-1.

for new homes, leading to suburban expansion. As the baby boomers enter retirement, there’s a growing demand for healthcare services, retirement homes, and age-specific recreational activities.

From A Legal Perspective

Understanding the concepts of ‘substitutes and complementary goods’ is crucial for competition law scholars. These concepts help analyse market competition by identifying which products or services directly compete with each other (substitutes) and which products or services are consumed together (complements). This distinction is vital for assessing the potential for anti-competitive behaviours. For instance, in merger evaluations, understanding whether merging entities produce substitutes can help evaluate the impact of the merger on market competition and consumer welfare. The merger of two companies that produce substitute goods can reduce market competition and make consumers worse off.

Another example is a firm that may bundle a complementary product with a main product to exclude competitors, increasing market power and raising concerns under competition law (Refer to United States v. Microsoft Corp case). The concepts of interchangeability and complementarity can help lawyers define relevant markets, a foundational step in competition law analyses, as it draws the boundaries within which competition cases are assessed. Understanding these relationships enables scholars and practitioners to identify and address anti-competitive practices better.

From a legal perspective, ‘future price expectations’ can significantly alter the behaviour of individuals, including those engaged in or considering criminal activities. In the context of a simple demand, anticipating higher or lower prices can lead consumers to adjust their purchasing behaviour. Similarly, in criminal behaviour, the perception of the ‘cost’ or ‘price’ associated with committing a crime can influence a criminal’s decision-making process. If the expectations of being caught and punished for a crime are low, i.e., the ‘price’ of committing a crime is law, they might be more inclined to commit crimes and vice versa. This is where deterrence policy, such as lifetime imprisonment and the death penalty for severe crimes, comes into play. The punishments are not only to punish the convicted criminal but also to prevent future crimes by other potential criminals.

The Real-Time Examples From Newspaper

Here are real-time examples from newspaper articles illustrating factors that affect demand.