Framework for Living Systems

Instructor : Emmett ZeifmanGSAPP, Columbia University

June 2019 - August 2019

This studio revisits “new brutalism,” working from the principles for architecture articulated by Alison and Peter Smithson and Reyner Banham in the early 1950s: a legible synthesis of spatial, structural and material organization; individual buildings conceived as urban theses; the ambition to directly express new technologies and social relations through architectural form.

Students are asked to critically evaluate the efficacy of these principles today, which is marked by the aftermath of global crisis, rapid transformation in technology, media and consumption, shifting horizons of political possibility, and the need to rethink the nature of urban inhabitation. The studio project is a prototypical urban infill building. Rather than adhering to conventional programmatic categorizations, each project should challenge commonplace distinctions between residential and commercial, as well as “public” and “private,” spaces and programs.

Housing developed by the real estate market is designed on the basis of the homogenization and standardization of individuals within our society, targeting the nuclear family and their supposed way of life as the basic social unit of cities. The project uses a lot adjacent to the high-line – current setting for mediocre high-end housing - as a prototypical proposal to question this inadequate system. It also explores an architecture that frames the constant changes of social structure in regards to gender, constitution of family, individual and collective needs and the infinitely diverse relations between living and working within our society generated by our modern means of production. The project address and facilitates these systems and changes through aspects such as modularity in the habitable spaces, a shared economy based on a kit of parts, an extended infrastructure unit, and curated flexible spaces. The architecture proposes, through the possibility of horizontal and vertical mergers, the accommodation of individuality and the creation of social dynamics within the building in itself.

MASSING

Pin wheel formation to ensure every unit gets views of the city

GROUND ACCESS

Ground units have storefront access. Three other separate access to the core and one entry to the warehouse

Concept Diagrams

Framework for Living Systems |

VERTICAL CIRCULATION

Three Cores provide vertical circulation from the ground while one is directly accessible from the High-line.

INTERNAL CIRCULATION

The internal circulation is primarily on metal floor plates sandwiched between the modules and the automated storage system

STORAGE SYSTEM

The storage system comprises the warehouse and the delivery mechanism of the storage boxes to the modules.

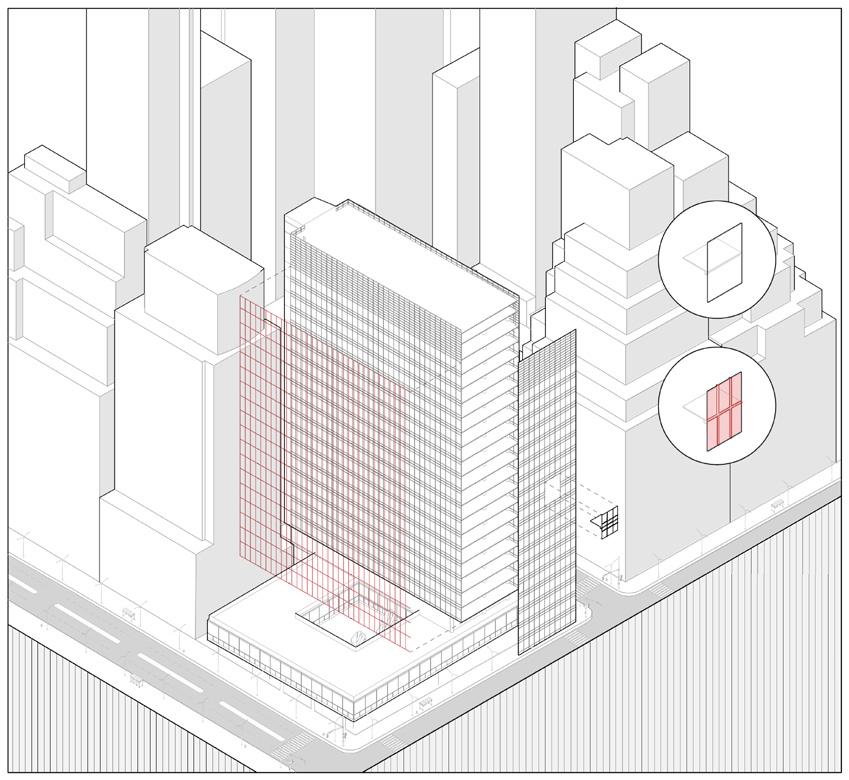

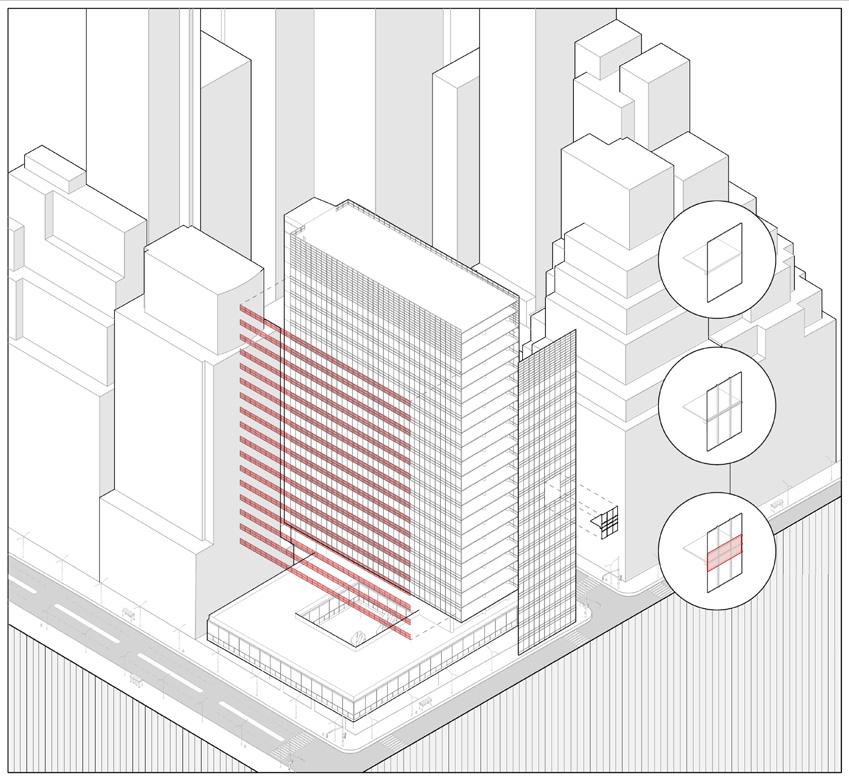

THE MODULE

The module is essentially split into two parts - the preset infrastructure and empty structural grid.

Framework for Living Systems

GLASS

Glass is used on the external facade to match the typical New York City scape. Frosted Glass is used in the interior partitions of the empty structural grid

WOOD

Wood is used in the building as the primary material for the construction of the inbuilt infrastructure of all the unit modules. The wood sits on the steel framework and provides better insulation

The core is made of blackened steel exterior to avoid corrosion . This extends to the interior of the storage system which in turn holds aluminum storage boxes to reduce the weight on the structure as a whole.

STEEL

Steel is the structural element for the entire project. The steel framing enables easier flexibility to the module like design of the building. It also enables more efficient laying of the floor and wood panels.

Each unit is divided into two, a minimum living space with preset infrastructures (plumbing, heating, ac, etc.) and another as the agent to democratize space within the building. Social interactions within the building would be therefore not others. Beyond being able to buy two units to merge and expand their own space, users would be able to use or rent the empty would allow for a infinitely wider possibilities of use and would itself create unique social dynamics. Complimenting This helps facilitate the customizations mentioned before. The system would be made up of boxes in which a variety construction materials to household utensils. Through access to this system, the building’s user would be able to easily range from furniture and equipment for a party to be held one night and returned the next morning, to the installation of a

another half constituting an empty structural grid, located on the perimeter of the building. The empty grid would act not only confined to quick elevator interactions but would also expand to talks where the action of one would involve empty grid space as they pleased making it possible to merge units and air space to create unique spatial combinations that the unit, the building houses an automated storage which holds a shared economy system within the building itself. of items would be held that could be accessed by the unit’s user at any time. This would range from prefabricated easily customize his own unit in order to accommodate any short, medium or long term need he might have. This could a pool during the summer months. In NYC, where space is a luxury, this capacity to change space would amount to luxury.

The Little Big Loo

Competition / Thesis Project

Volume Zero

June 2020 - July 2020

Rapid population growth in urban areas usually gets coupled with poor planning of physical and social infrastructure. Poor sanitation is also one of the prime factors in the onslaught and spread of epidemics and pandemics that cripple the world’s economy and social fabric.

Rethinking Public Toilets invites ideas that can be used to disrupt the perception of public toilets with the most innovative and efficient solution for this serious issue plaguing our future. This necessary public utility is to be designed in a way that changes the overall outlook towards public wash- rooms.

The designed area can be recreational, educational, social; a space that creates value for the community surrounding it. The space should be visualized as a prime component in the making of a community that develops holistically in social, economic and educational terms.

T.nagar in Chennai is one of the busiest pedestrian shopping districts in India with an average of 50,000 shoppers everyday. This number can go up to a maximum of 2 million during festival season. The neighborhood thrives on the closely packed shops, outdoor vendors, kiosks, large crowds and, the business it generates from this social mesh. However, the urban planning for the neighborhood as a whole is poor and there is also a lack of resting spaces and public toilets that is needed to cater to such a large pedestrian crowd.

The proposal is to design a public toilet module that also works as a resting place. These modules then would be strategically placed across the neighborhood based on walking distance and survey studies. Each module accommodates a 400 sq.m plot. Each module is designed according to standards needed to accommodate a footfall of 2000 people. Additionally, in the wake of Covid-19, the design is looking to change the unhealthy perception of public toilets in India by having enclosed resting spaces while maintaining public health protocols.

T.Nagar is a mixed residential neighborhood in the city of Chennai in South India. It is foremost a commercial hub for shopping in Chennai. It also accommodates some offices,schools and temples. The average shoppers amount to around 50,000 every day with the number rising to over 2 million during festivals. It makes a profit of almost 10 million rupees a year and the visitors are both local and international. Chennai city’s average population density is 26500 people per square kilometer and is one of the most dense cities in India. However, the density in T.nagar exceeds the average by almost twofold in number. The most populous streets are Pondy Bazaar and Ranganathan Street which have little to no vehicle movement. The central Panagal park is the only relief point with a public toilet for this entire neighborhood but is surrounded by roads that have heavy traffic making its access less convenient.

Contentious New York

Instructor : Andrés Jaque / Bart-Jan PolmanGSAPP, Columbia University

June 2019 - August 2019

The workshop focuses on reconstructing the design history of the contentiousness that has shaped 32 selected architectural entities in New York. Each of the cases will be characterized as the site of one or more conflicts. The goal of the workshops is to identify these conflicts and to trace and translate into documents the ways in which architecture becomes part of them and of their evolution.

Students are asked to engage with the reconstruction of the conflict both through writing and through drawing. They are them asked to map out the evolution of the architectural device studied (materially, compositionally, performatively) as a result of/ as part of/by the trajectory of the dispute. In this workshop, (architectural) form is understood as being the result of tensions. The identified conflict and its subsequent evolution will be characterized as transscalar, as operating on many different scales simultaneously.

The project assigned to us was the Lever House, one of the earliest curtain wall skyscrapers in New York City. It is now an official landmark building that arguably defined and influenced the modernist architecture of New York City we see today. The breakdown of the architecture begins with the following propositions as its starting point :

• Looking back at the disputes and controversies that shaped the design.

• Understanding how the evolution of a conflict is reflected or interpreted as design alternatives.

• Realizing that the content of the conflict is a discussion that takes place on and off the architectural field and dissecting it accordingly.

• Articulating the conflict as an element that frames the architecture and lends itself to the design process.

• Finally concluding with a wholesome narrative of how conflict, discussion and architecture work in tandem to produce design that stands out while influencing its surroundings.

LEVER HOUSE

The case of the Lever House begins with a look at the prominent British 20th Century soap company, Lever Brothers Company. After great success in moving their operations abroad to the United States in 1895, the company had decided to build a new world headquarters in New York City. The new president of Lever Brothers at the time, Jervis J. Babb, had been profoundly enamored with the ideals and values of architectural modernism. He had worked in Frank Lloyd Wright’s glass-towered Johnson’s Wax building during his time as vice president there. His experience, along with the Lever brothers’ ideologies , influenced them to bring a modern image to their new headquarters. It is because of these intentions that the company went on to choose Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings, Merrill as the architect of the project. Responding to Lever Brothers’ desire for an image of sparkling cleanliness and their intention to convey cleanliness and innovation to their project, SOM proposed a modern building of steel and glass in the International Style. Completed in 1952, it was the second curtain wall skyscraper in New York City after the United Nations Secretariat Building. It paved the way for midtown Manhattan to change from a street of masonry apartment buildings to one of glass towers. Also, the Lever brothers’ statement, to make their world headquarters ‘a symbol of everlasting cleanliness,’ meant that the first window-cleaning scaffold in New York was built in 1952, to maintain the outside of Lever House. An electrically operated platform built by the Otis Elevator Company set the standard for how the city’s rising thicket of glass, steel, and sealed windows would be cleaned. The government or zoning laws of that period also played an essential role in the design of the lever house (specifically the 1916 Zoning Act) . The complex of skyscrapers being built in New York were making streets narrow and creating dark alleys. The idea of this act was that light and air would reach the sidewalk. Instead of setting an absolute cap on height, the law required that after a prescribed vertical height above the sidewalk (usually 90 feet for cross streets or 150 to 200 feet for avenues), a high-rise had to be stepped back within a diagonal plane projected from the center of the street. The proposed office tower of Lever House, a vertical slab, conflicted with apparent solutions to zoning ordinances that required setbacks for light and air. In response to the civic regulations, the footprint of the tower was minimized to be less than 1⁄4 of the site. This was done so that the design of the office volume would be a clean and pure vertical slab that went straight up. Lever House was the first New York real estate venture to take advantage of the zoning provision . As a result, Lever House broke the tradition of “shaped tower” skyscrapers which had prevailed since the 1910s. The vertical office volume surface was designed as an all-glass window wall system. The surface, based on a 4’8” module, was composed of 6’6” high sealed tinted green heatabsorbing transparent glass, 30” high blue wire spandrel glass, and stainless steel mullions. The tint of the transparent glass and spandrel glass was drawn from the color of many of the company’s iconic products. 2 1⁄2” wide, the mullions projected only 1” to reduce the amount of shadow cast on the glass. This allowed the window wall enclosure to appear as a smooth flush surface with minimal depth. In addition, according to the company’s intent, the specified glass was highly reflective to help facilitate the appearance of a thin clean, polished surface. The reflective glass was placed outside of the columns and wholly obscured any indication of the structural system from exterior views of the vertical office volume in the daylight. This askew relationship between enclosure and structure seems to favor the corporate intention of self-promotion over the modern design idiom of structural honesty. However, the desire for this image of the building did not meet the requirements of the government building regulations, the fire code to be exact. The New York City fire code required a distance between the top of one window and the bottom of the next window. To meet these construction criteria, a 4” thick fireproof masonry wall was placed behind the spandrel panels. This conflict of intentions between civic regulations, technological know-how, and design philosophy resulted in the construction of a multi-layered building enclosure. The enclosure was composed of a conventional masonry wall, constructed to meet the fire code, which was then concealed by a reflective glass spandrel panel to maintain the smooth, consistent surface of the floating volume intended by the design. The clean, seamless facade that the company and the architects were describing as their ideology and concept was just a veil that masked the flaws and mishaps of the actual building. It is almost as if they were promoting a mirage. In 1982, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated Lever House as an official landmark. By that time, however, much of Lever House’s original brilliance had been dimmed. The building’s blue-green glass facade deteriorated due to harsh weather conditions and the limitations of the original fabrication and materials. Water seeped behind the stainless steel mullions causing the carbon steel within (and around) the glazing pockets to rust and expand. This corrosion bowed the horizontal mullions and broke most of the spandrel glass panels. By the mid-1990s, only one percent of the original glass remained, leaving the once glimmering curtain wall a patchwork of mismatched greenish glass. In 1998 the leasehold position was acquired from Unilever by German-American real estate magnates Aby Rosen and Michael Fuchs. Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, the building’s architect, were the ones who performed the renovations as well. The deteriorated steel sub frame was replaced with concealed aluminum glazing channels, which is identical to the original in appearance. All rusted mullions and caps were replaced with new and identical stainless steel mullions and caps. All glass was removed for new panels that are nearly identical to the original, yet meet today’s energy codes.

The Question Asked : A small start-up technology company will be moving from their co-working space into proprietary office space in a ‘hot and happening’ location in an urban metropolis. Help them envision an ‘innovation lab’ type of space for them. The head of the company has expressed a desire to “..have a space unlike anything she has seen before!” They have a modest budget and the schedule is aggressive.

The goals of the space are to:

• Enhance their brand and reputation so that they may impress potential investors

• Foster creativity and innovative thinking within their employees

• Have a ‘wow’ factor for employees and guests

In what ways, including spatial design and other (such as policies, services, events), can we help the client facilitate and enable innovation?

Center for Innovation

Platform : Case Study

The Makers Collective

June 2022- July 2022

Innovation Labs. Incubators. R&D Hubs. Accelerators. Centers of Excellence - No matter what an organization chooses to call this particular function, it is an open, collaborative space where companies and organizations team up their employees from different departments with outside tech experts, designers, and academics, seeking to emulate the culture, speed, tech integration, and disruptiveness of a start-up, in order to develop new products and even business models that take advantage of new business strategies and advances in technology

Open Innovation Labs are a powerful way for companies to inspire new ways of working and drive rapid, consistent innovation.

These questions need to be explored through built work. Building off this aesthetic, the labs need to be made with diverse material assemblies that delineate space for contemplation, prototyping and critical thinking. Together, these spaces will showcase an industrial framework for rethinking innovation and invention.

SHOWCASING THE CULTURE OF INNOVATION

CORE ASPECTS:

DEFINING THE LABS GOAL

Defining the organization’s purpose and reason for existing beyond making money is the first step. A newly defined purpose or redefined motto can ignite the organization’s entrepreneurial spirit, create a new identity and interest for promoters.The role of the OPEN INNOVATION LAB as the company establishes itself in this new strategic geography will be to partner with businesses and the city to bring customer needs to the forefront of the design of its products and services.

BUILDING A CREATIVE TEAM

A lab needs a mix of strategists, designers, and makers who can work as a cross-functional, collaborative team that can make more rigorous, data-informed decisions. Factors to consider in the hiring/training process : Hire those who are curious, empathetic, optimistic, open to experimentation and collaborative - Look for capabilities like interactional design, industrial design, communication design (visual and verbal), business design, product design and organizational design.

THE DESIGN

THE DESIGN

FOSTERING PARTNERSHIPS

The OPEN INNOVATION LAB needs to be organized beyond company employees, actively engaging with outside experts. The lab needs to be able to demonstrate products and capabilities to current clients, potential clients, and business partners. This can be done by fostering partnerships with outside companies, startups, and leading academic organizations. It needs to be a stage for presentations and collaboration with customers to co-create and get feedback about new products.

DESIGN

THE LAB SPACE

Expressing the spirit and aspirations of the lab through physical design is about more than post-its and foam core boards. This can be reflected through open floor plans and plenty of daylight. Collaborative and headsdown working areas are also necessary for digging into hard problems. The Lab can include product kiosks, environmental graphics, technology, and hands-on equipment in a working lab setting to accommodate multiple objectives.nking. Together, these spaces will showcase an industrial framework for rethinking innovation and invention.

MEDIA PODS

CO-CREATIVE SPACES

A dedicated workspace for the team and the co-partners to operate specialized equipment and tests. A living showroom of the company’s innovations.

BREAKOUT SPACES

Spaces across the building for employees to have social gatherings, informal chats and thought showers.

STREET activities street. serve as an above workplace.

Private meeting pods for smaller team meetings and presentations.

COMMUNAL SPACES

spaces open to promotion among public crowd. Weekly workshops and product sessions can help boost company’s value.

OPEN WORKSPACES

reconfigure, rounded furniture in an open layout flexible floor partitions to encourage group discussions.

STREET activities street. serve as an above workplace.

Private meeting pods for smaller team meetings and presentations.

COMMUNAL SPACES

spaces open to promotion among public crowd. Weekly workshops and product sessions can help boost company’s value.

OPEN WORKSPACES

reconfigure, rounded furniture in an open layout flexible floor partitions to encourage group discussions.

Professional Work

Chennai, India

June 2017 - April 2018

My work experience is from June 2017 to April 2018. I interned with two different firms having two different work cultures.

The first stint was at Larsen & Toubro, Chennai. Being a corporate firm, my work involved learning about project management, working on detailed core drawings and digital modeling of project aspects. My major contribution came in the form of producing working drawings for the toilets and stairways for the core of Ford’s 2.7 million square feet global business center in Chennai, India.

The second stint was at dimensions, a private firm that mostly dealt with residential projects. I was involved with various works that included elevation drawings, schematic plans, detailed drawings, but my most prominent contribution was the concept render, detailed plan and elevation design for the entrance lobby of a condominium.

Dimensions (January 2018 - April 2018)

• Antareeksh Condominium (Chennai, India)

1. Concept Render

2. Lobby Schematic Diagram

3. Lobby Elevation/Section

4. Lobby Detailed Plan

• Residential Villa (Chennai, India)

1. Concept Diagrams

2. Elevation

3. Plans

Larsen & Toubro (June 2017 - October 2017)

• Ford Business Center (Chennai, India)

1. Core Toilet Detailed Plans

2. Core Toilet Detailed Section

3. Core Toilet Fixture Details