CULTURAL VIBES OF INDIA

Crafts of Clay

Baked Earth and its various Indian proponents.

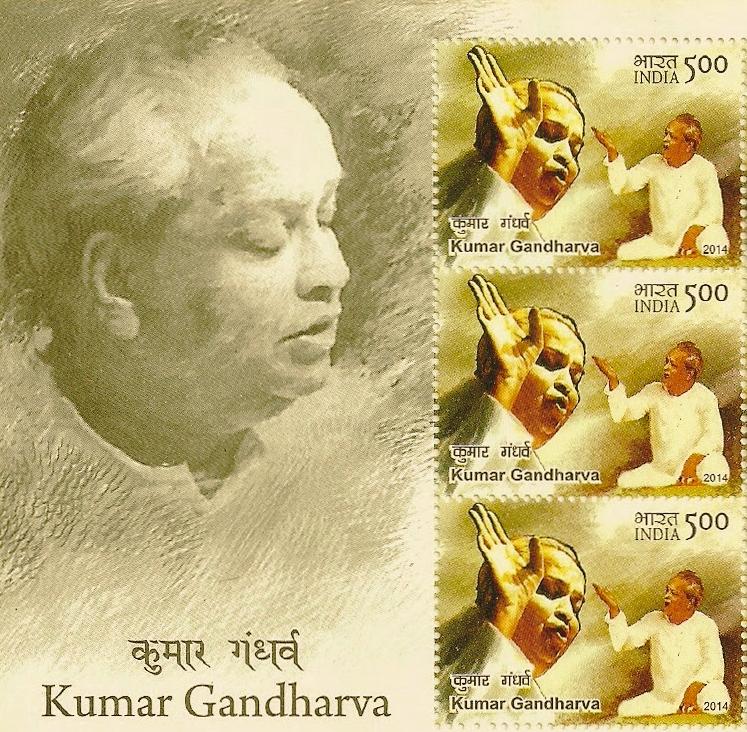

Pandit Kumara Gandharva

Celebrating the centenary of a genius musician.

Jim Corbett National Park

Jim Corbett National Park

Baked Earth and its various Indian proponents.

Celebrating the centenary of a genius musician.

Jim Corbett National Park

Jim Corbett National Park

F r o m T h e E

The world is a changing! And changing every instant. The future is now and some of it already in the past; the days and nights seem to be shifting faster than we know. Worlds and cultures are colliding and merging. In such a dynamic setting, what do we perceive our culture to be.

How do we build our opinions and align ourselves to them? If exploration and finding something new is an innate urge in us, how do we stay anchored to a static definition of culture? If we only glorify the past, how do we make space for the new age? What then of the broader community where opinions and views stretch the spectrum to extremities?

Perhaps we can only endeavour for an answer through an inquiring and open mind. A mind that is willing to go into the accumulated knowledge. A mind that can hold the opposing perspectives; the views and counter views and realise the blurred, hazy and transient nature of it all Along the way, we could be lucky enough to find some time-tested constants as well where the seeming dichotomies converge into a harmonious oneness.

From us, Edition 11 is a gentle nudge towards developing an inquiring mind. Read about how Yoga can be your guide on this journey of discovery. Experience the mesmerising powers of our music in the voice of Pandit Kumar Gandharva as we celebrate the centenary year of this Padma Vibhushan awardee. We include a read on a Nagaland tribe and its headhunting culture We present a music aficionado’s take on how one can find companionship and meaning in the several classical ragas. For the art connoisseurs we present a Srilankan artist who is giving Buddhist temple art a fillip in India. We trace back the use of clay in our crafts and cooking. We sprinkle these with some easily digestible reads - a ride on the humble 3-wheeler that makes India tick and a look at our national animal in all its striped glory.

As always we have endeavoured to present a small collection of the finest our culture has to offer with this edition We are sure it will go well with whatever you are having - Dosa or Pizza.

LET

Understanding Yoga as a path to our complete and holistic well-being

12 CRAFTS OF CLAYRETURNING TO OUR ROOTS

Traversing the relevance of clay in our tradition and culture.

20

A travelogue highlighting the traditions and culture of the Nagas

26

A melodic journey through emotions and beyond.

29

A ride through the 75-year history of Auto Rickshaws in India.

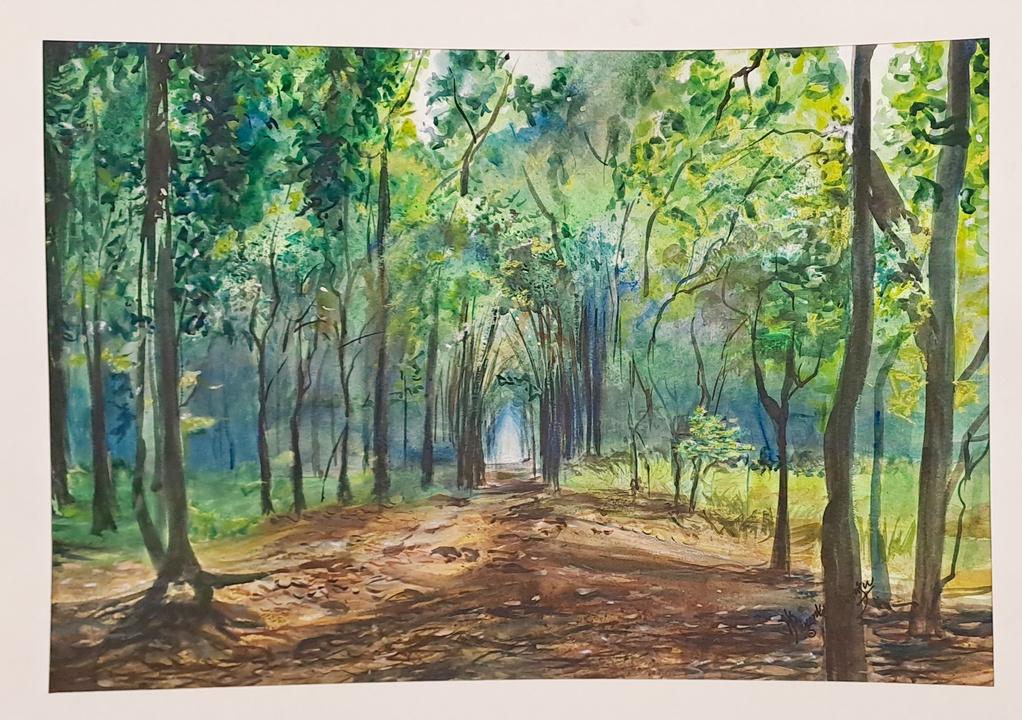

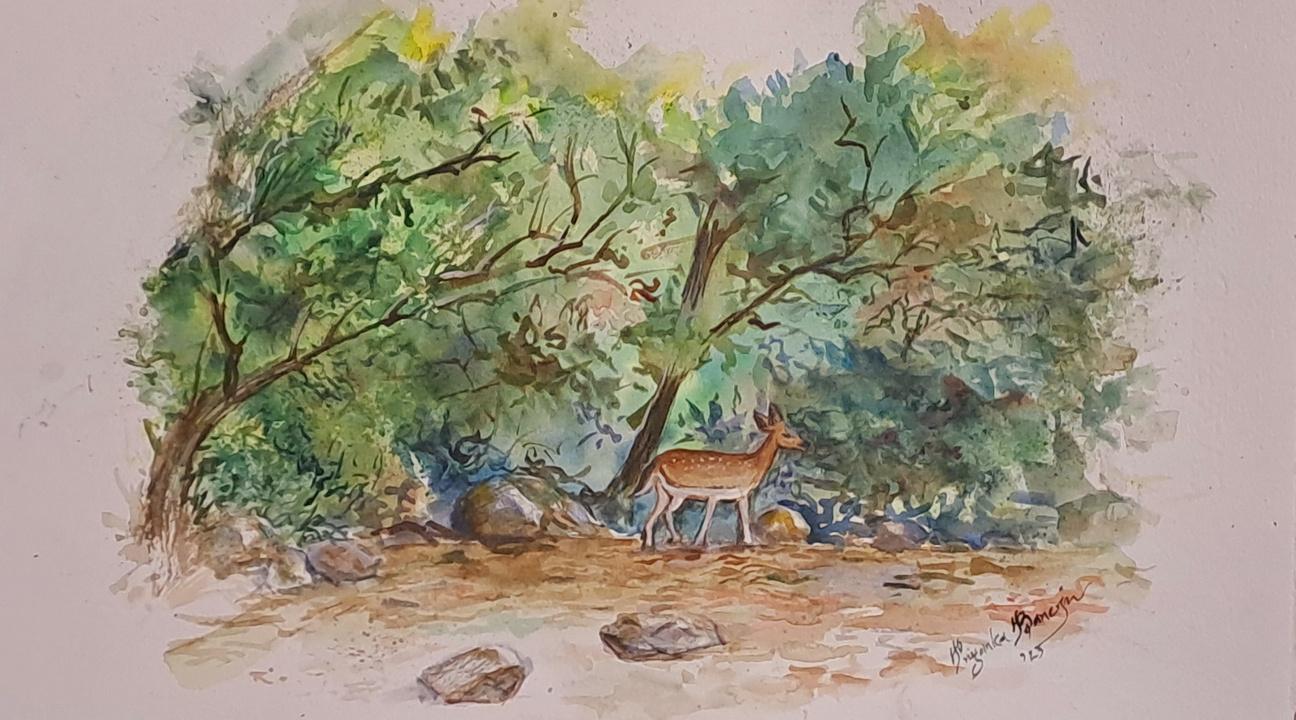

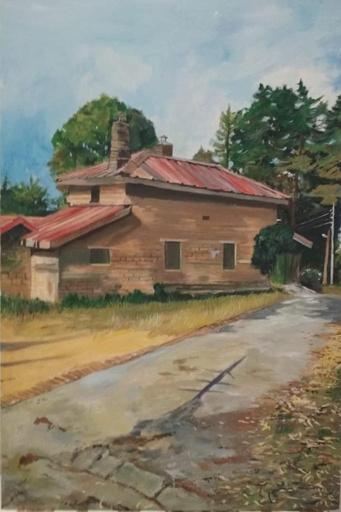

JIM CORBETT NATIONAL PARK

A painting essay on India's iconic national park 34

40

In his centenary year, we present a view on his music and its indelible impact on the author.

REMAKING BUDDHIST ART IN INDIA

47

A Srilankan artist's tryst with remaking Buddhist art in India.

Aparna Misra

A writer on culture and heritage. Educationist. Avid traveller and has written blogs and articles for newspapers and journals sharing her tales.

#OffTheGrid

Priyanka Banerjee

Passionate artist, writer, and social activist https://priyaban.com

Sachii Tripathii

A Ceramics & Glass Design Post Graduate from NID. I marry my passion, experience & knowledge to create and curate products that are contemporary yet rich in tradition.

Terracotta by Sachii

Sonali Dash

Hatha Yoga Teacher | Btech

Electrical Engineering | MBA | Ex Business Consultant. Hoping to spread the message of Yoga to as many people as possible.

www.sonali.yoga |

Instagram - @yogasonalidash | https://youtube.com/@dashsonali

Ishan Singhal

Ph.D Student in Cognitive Science. Football enthusiast. Amateur philosopher. ishansinghal@hotmail.com

Dr Pushkar Lele

Hindustani Classical Vocalist, Researcher, Guru, Traveller, Foodie, Home Gardener, World Cinema Lover, Aesthete.

http://www pushkarlele com

Shankar Gopalkrishnan

Devoted rasika of Indian classical music and allied topics. Indebted to music, inspired by Saint Tyagaraja's 'tava daasoham'.

shankar.ccpp@gmail.com

Sravanthi Edara

Nature lover. Slow-travel enthusiast. Freelance product designer. Finds joy in exploring new cultures. Learning farming alongside her work.

https://www.instagram.com/sravanth i edara/

Check page 19 to see how you can contribute to our next edition.

Why does life seem unfair at times? Why do some people have to go through much more pain than others? Why does opulence come to only a chosen few? Amidst all the vagaries of life, when one starts wondering and looking for answers, one is considered to embark on his spiritual journey.

In the language of Yoga, he is called a Sadhaka. While trading this path, it makes sense to understand what this life is all about. While everyone’s life purpose might seem different when we look at it from outside, the objective as per Yoga is the same for all, which is purification of mind.

Indian philosophies are not mere intellectual discussions. Instead they contain the knowledge that our sages have realised through their own experiences in deep states of meditation. These teachings being more existential in nature, are called Darshanas, which means something that has been seen.

There are six major Darshanas - Vedanta, Mimansa, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya & Yoga. For the purpose of this article, we will stick to Samkhya and Yoga.

Samkhya and Yoga are sister Darshanas, which means Samkhya gives us a theoretical understanding of mind matters while Yoga gives us practical ways to realise what is given in Samkhya. While Samkhya Darshana is a profound scripture, I would like to highlight what it has to say about the root cause of all pain.

It is the six enemies of mind - Kama (lust), Krodha (anger), Lobha (greed), Mada (pride), Moha (infatuation) & Matsarya (jealousy). Let us look into the possible root cause of each of these six enemies:

Kama (Lust) - Uncontrollable desire for sensual pleasures

Krodha (Anger) - Fueled by unfulfilled desires

Lobha (Greed) - Desire to get more of what we already got

Mada (Pride) - Excess attachment to existing materialistic possessions

Moha (Infatuation) - Excess attachment to material possessions

Matsarya (Jealousy) - Uncomfortable feeling because of desire to acquire what others have

So what is the root cause of all sorrow?

It is uncontrolled desires stemming from lack of control of senses. Srimad Bhagavad Gita articulates this in Chapter 3, Shloka 34 -

“Indriyasya indriyasyaarthe raga dwesha vyavasthitau, Tayoh na vasham agachhet tau hi asya paripanthinau”

Translation: Attachment and aversion happen when senses are excessively attached to the sense objects. When not disciplined, they become obstacles in the spiritual path.

So the senses need to be disciplined to be free of sorrow and the process of doing that is the path of Yoga. This process cannot be the same for all because every individual is different. As many individuals, that many paths of Yoga. So how does one find one’s path?

The Indian system of thought places a lot of importance on Dharma (duties). But as one trades this path, one often encounters the question - What is my Dharma? We must understand that our only Dharma is to realise our divine nature. It does not mean we should drop all our responsibilities and run away into the forest.

We should understand that the kind of situations that we are put in is to facilitate our spiritual journey. Running away from them will only cause more trouble.

Swami Chinmayananda articulates it beautifully - “By non-doing of duty and by omission of completing your duty, regret comes in mind continuously”.

Since every individual is different, situations around him are also different. Circumstances around us are the way they are because it is the necessary stimulus to propel each individual's spiritual progress toward a sorrow-free state. Though many things seem so out of place when seen from outside, the role that every situation is playing is aimed towards spiritual progress.

In cosmic play, the role of a beggar on the street is no less important than the role of the prime minister of a country. When this becomes our living reality, we understand what true equanimity is really.

When we face our challenges bravely, fulfil our duties with the best of our potential, true wisdom dawns upon us. The great saint Sri Anandamayi Maa put it beautifully - “Only when you fight your battle of Kurukshetra like Arjun, the wisdom of Gita arises in you.” Our daily life can be akin to Kurukshetra where we are pulled by several forces in all directions.

Truth be told, being Arjun is not an easy task. Even a highly trained warrior like him was trapped in an ethical dilemma in the middle of the battlefield. This is the true representation of the situation that most of us are in.

The first chapter of Gita, Arjuna Vishada Yoga, is all about this sorrow. When we keep doing our best, but are unable to find the happiness we are seeking, the true submission happens.

This has been beautifully put in the Shloka 7 of 2nd chapter of Gita -

Translation: My heart is overpowered by the taint of pity; my mind is confused as to duty. I ask Thee. Tell me decisively what is good for me. I am Thy disciple. Instruct me, who has taken refuge in Thee.

This is a significant stage in the journey of the seeker. With this submission comes the true knowledge. Even in Bhagavad Gita, Krishna starts revealing the spiritual wisdom only after Arjun’s surrender. Till then he was tight lipped about these matters.

There is also mention about qualifications of a seeker in the Upanishads - “The seeker is one who has seen the worlds won by good deeds and also the utter futility and emptiness of the achievements of this world. He has seen how happiness is such a short-lived experience. How nobody is completely happy, how, in any happiness, there is always some unhappiness hidden, which, at any moment, can show up. The Upanishad will not penetrate, however much we talk, unless and until one understands the impermanence of this world.”

When a person reaches this stage in his life experience, submission naturally happens. Till submission happens, the mind is unsteady and unfit for steadfast attention. But the good part is that things are not as hopeless as they seem; many things can be done to make the mind fit for absorbing spiritual knowledge.

The role of self discipline is extremely important in the path of Yoga. As one of the great modern day guides, Sri M, puts it - “Nishkama karma (actions without expectations), coupled with practice of introspection and meditation, are recommended practices to achieve a silent mind.”

One has to have some discipline based on one's potential. In my experience of teaching yoga for the last five years, I have seen great results in my students who have followed these habits:

Set aside some time every day and watch your thoughts and emotions very closely, trying to disengage from them at the same time. In the process one will most likely realise that what we call mind is just a bunch of impressions that we have gathered from our past experiences. Quality of our thoughts depend on the quality of these impressions. With consistent practice it is possible to disempower these impressions.

Keep one hour every day for yourself without fail.

Dedicate one hour every day to do things that make you feel centred. It could be practice of yoga asanas, any exercise of your choice, meditation, practice of any art form, etc. You can also break down this hour into multiple slots during the day.

Try to live with an attitude that there is no failure, there are only learning experiences.

Whenever possible, do something good for others without any expectation. As much as possible don’t hurt others. Choose your words and actions carefully.

Practice gratitude even for the smallest things. Even when things go wrong, be grateful for the learning that came out of the episode.

Breathing practices help immensely to keep emotions in balance.

Consistent practice of the above habits conserves energy. This energy helps one to become meditative. It is important that we don’t get discouraged if we fail initially. If we don’t let the negativity of failures affect our one-pointed attention and only focus on the learning, success is bound to come.

In Patanjali Yoga Sutra (PYS), one of the most profound texts of Yoga, we find the definition of Yoga and how to achieve tranquillity of mind.

“Yogaschitta vrtitti nirodhah”

- PYS, Chapter 1, Sutra 2

Translation: Yoga is transcending the disturbances of mind.

“Abhyasa vairagyabham tannirodhah”

- PYS, Chapter 1, Sutra 12

Translation: Transcending the disturbances of mind is possible with consistent practice and detachment.

With practice of self discipline comes Vairagya (detachment). As self mastery deepens, so does Vairagya. In Indian society, Vairagya is often misunderstood as giving up actions and retiring to forest. Vairagya actually means dropping of attachment to the results of action, not abandoning the action.

Vairagya is beautifully explained in the text Srimad Bhagavatam. Mind cannot stay without attachment. As long as it is attached to materialistic desires, we will be trapped in the neverending cycle of sorrow. But if it is attached to the Divine, materialistic desires automatically drop. Self discipline strengthens our connection with the Divine. This is the real essence of Vairagya.

Deeper the Vairagya, the more meditative one is. It is possible that when Vairagya becomes more and more firm, one experiences a blissful tranquillity regardless of external turbulence. One’s inner peace is unaffected by what is going on outside and at the same time one is able to work for the welfare of others, no matter what the situation is. This is key to one’s well being. Food habits, sleeping patterns, lifestyle choices automatically change as one is established in Vairagya. A yogi who has perfected Vairagya will always be respectful to the people & resources around him and will never consume anything more than what is needed. His senses are always in control and he always works for the welfare of others.

While there are numerous paths of Yoga, for example Mantra Yoga, Jnana Yoga, Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga and so on, in the modern times, most people understand Yoga as bendy physical postures. Let us understand the importance of practice of physical postures in Yoga.

There is a path of Yoga called Hatha Yoga, which uses deep knowledge of how energy flows in our body. In our body, there are energy channels called Nadis and energy clusters called Chakras, which when blocked result in imbalance of physical and mental health. Without a healthy body and mind, spiritual practices become very difficult. Asanas play a very important role in maintaining good health by helping in the optimum functioning of Nadis and Chakras. Muscular, skeletal, endocrine & nervous systems work much better with regular practice of asanas. Asanas also help to keep the spine strong & supple, which later helps in meditation.

Asanas work much better when one practices them with the aim of progressing faster in the spiritual path. Practice of breathing techniques (Pranayama), awareness and good behaviour along with Hatha Yoga postures produce results even faster.

As a Hatha Yoga teacher, I have been very fortunate to work with many meditators. And all of them have reported that their mediation got better after starting Hatha Yoga practice. Swami Kuvalyananda used to say that Yoga is Kalpataru (the wish-filling tree). It provides a holistic approach to well-being from all fronts - physical, emotional, intellectual & spiritual. It gives us a true purpose to life. It is my heartfelt wish that Yoga becomes a way of life for everyone.

By Sachii Tripathii

By Sachii Tripathii

Terracotta – the most basic of all materials – literally means baked earth. Ever since the discovery of the wheel, human beings have been shaping lumps of clay on the wheel, hardening the products in fire, and using them for cooking and storing food. Clay pottery has thus been in practice since the Mesolithic age! While it was not unusual to cook and eat out of clayware a few centuries ago, growing industrialization has taken us farther and farther away from our roots!

India has a rich history of crafts, and different regions across the nation have their own distinct and very unique indigenous styles of terracotta pottery crafts – like the Molela Craft of Rajasthan, Black stone Pottery from Manipur, Painted Pottery from Kutch, and many more!

However, there has been a decline in the number of artisans practicing these heritage crafts over the years – and while the COVID pandemic has only worsened the situation leaving many of these people without work, the good news is, it has also shaken and woken us up to go back to our roots, and post the pandemic, people are in fact looking for eco-friendly, natural and sustainable products in organic materials like terracotta! This gives an opportunity to the natural, humble, sustainable, and biodegradable clay to make a comeback into everyday lives just like those of our ancestors, in the form of contemporary, functional as well as decorative lifestyle accessories that include cookware, serve-ware, home and wall décor and even architectural accessories like tiles, furniture, building material!

The ancient art originated from the two Longpi villages in Manipur, Longpi Khullen, and Longpi Kajui near Ukhrul district. It is mainly practiced by Tangkhul community residing in the hill district of Manipur. Longpi pottery is made from a mixed paste of ground black serpentinite stone and special brown clay found only in Longpi village. The pots are manually shaped, polished, sun-dried, and heated in a bonfire! The black color of Longpi ham is a result of the reduction firing of the ware while polishing the heated earthen pots with a local tree leaf gives it a beautiful shine. Unlike most other kinds of pottery, Longpi Hampai is not shaped on the potter's wheel but by using hands and basic hand tools. The entire process s quite labor-intensive, and while it's mostly

the men making the pottery, women folk also participate! It's heartening to see the younger generation also taking an interest in the craft and willing to take the legacy forward!

This terracotta clay pottery is practiced in Nizamabad Azamgarh UP. This craft originated centuries ago when the Nizam called for a few potters from Kutch (presentday Gujarat) and asked them to start practicing here! It was given the Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2015 by the Government of India! This pottery is made with local clay collected from river banks and ponds. After the ware is made on the wheel or made by hand and dried, they coat it with a liquid made by them with leaves and other locally found organic material. The ware is dried again, carved, burnished with mustard oil, and then fired in a saggar such that the smoke is captured within the furnace, and the ware turns out completely black and shiny. Post firing, the carvings in the ware are filled with lead+mercury powder.

This age-old craft dates back to the Indus Valley Civilization, with only a handful of families practicing today as most others have moved to other day jobs. It originates from the Kutch region, which is a district in the westernmost part of Gujarat and is influenced by various cultures. The entire process has been the same practiced ages ago - and all the materials used are entirely organic and locally found! They collect mud from a nearby lake and make their own clay. The clay is carefully prepared, shaped by hand or using a potter's wheel, and the ware is left to dry.

The dried ware is handpainted with clay-based colors (made by grinding locally found black stone and white clay) using bamboo brushes and tools which are made by the artisans themselves. Once dried, the ware is fired in pitfiring kilns. Artisans hand-paint traditional motifs like peacocks, elephants, geometric patterns, and floral designs in their pottery, creating visually stunning and culturally significant pieces.

Known as Lippan Kaam or Lippan Mud & Mirror Work, it is the traditional Mural Folk Art Form from Gujrat, India. Several desert communities in Rann of Kutch do this mud relief work in their own distinct ways. Practiced mainly by the Rabari, Kumbhar, Harijan, and Mutwa communities of Kutch, the origin of this craft is traced back to the Kumbhar community. As part of ritual cleansing, fresh gobar-mitti (dung+clay) paste is applied to the interiors and exteriors of the traditional mudhouses of Kutch by the women folk after certain intervals of time (often coinciding with festivals). On this blank canvas, they build up relief patterns with rolled coils of the dung+clay mix and embellish it further with small pieces of inlaid mirror resembling the embroidery work of the area - patterns and symbols which are believed to prevent the entrance of evil, thereby ensuring health and well being for its inhabitants. It was originally used to decorate walls of indigenous houses in Kutch using local clay and decorating with mirror pieces. The decoration covers not only the walls, doorways, and lintels of the bhunga houses but also the shelving, partitions, storage containers and cupboards, which are built from mud over an infrastructure of bamboo sticks. The craft today has been adapted into a contemporary avatar to bring modern, designer products!

At Terracotta by Sachii, we have created contemporary products inspired by these beautiful art forms by transferring these crafts to portable surfaces and using contemporary materials for longevity so you can enjoy their beauty in your own spaces! The last 15 years of my life were spent with clay, and I vow to dedicate the rest of my life to the same, returning to it thereafter! In the end, I would like to quote my Guruji Shri Gir Raj Prasad:

Paanch Tatva ka Satva Hai Ye Hai Maati ka Khel, Ant Samay bhi Mera Hoga Isi Maati se mel...

The five elements form the essence of this play of clay (just like life!), I have (like all other life) come from the Earth. And in the end, Back to the Earth (clay) I’ll go

What inspires you about our culture, history, arts and music?

By Sravanthi Edara

By Sravanthi Edara

Nagaland has intrigued me with its culturally diverse tribes that have retained their rich heritage and traditions. Recently, I had the opportunity to visit this fascinating place, and my experience revealed a depth I hadn't anticipated. During my journey, I explored different districts and interacted with four prominent tribes of Nagaland: Angami, Chakesang, Konyaks, and Ao Nagas. What struck me was how the level of development and exposure to modernity varied among these tribes, often influenced by the arrival of missionaries.

As I delved into the local culture, I encountered stories about the formation of Nagaland as part of India. During my travels, I also came across local books that provided detailed accounts of historical events. Interestingly, despite being in India, I noticed that many Nagas identified themselves primarily as Nagas rather than as Indians, which highlights their strong cultural identity.

Moving beyond the political and historical aspects, I immersed myself in the vibrant local culture. I discovered that most Naga tribes had a history of practicing headhunting and were known for their hunting prowess. They held deep connections to the land, with disputes over resources and territory common among neighboring villages. These conflicts often involved villagers attacking one another to claim the enemy's head, which was believed to hold their spirit and bring good luck. The skulls of defeated enemies were proudly displayed in front of homes. Hunting and foraging for food were essential to their way of life, and meat, particularly pork and chicken, formed a significant part of their diet. They also cultivated rice and harvested various herbs, spices, and vegetables from the jungles, incorporating them into their flavorful dishes. Additionally, I came across the concept of "Morungs," which were residential schools for bachelor boys until they were 18. In these institutions, they learned vital life skills such as hunting, gathering, and cultivating while fostering strong familial and community relationships.

My journey through Nagaland deepened my understanding of the importance of preserving cultural heritage and the challenges different communities face. It has reinforced the idea that the longing for autonomy and the right to self-determination is a universal sentiment. Though I may not be in a position to take sides or form a definitive opinion on what is right, Nagaland has taught me the significance of embracing diversity and appreciating the struggles of others.

The most lovely part of my Nagaland trip was visiting the land of Konyaks. Just like other Naga tribes, even Konyaks are into headhunting culture, and they are the last tribes among Nagas to stop headhunting officially around the 1970s. Interestingly, they didn't have as many interactions with British rule and Indian Army as the other tribes. They lived freely and practiced their traditions till strict laws came against headhunting. So Christianity also came in here pretty late. So it's only around half a century from when it stopped, so they all still live a basic life and practice their traditions. This is why I wanted to travel to this region for a long time. Konyaks live in the northern part of Nagaland. It's a back-breaking 16 hours journey to travel from south Nagaland to north Nagaland. And the bus takes the road via Assam, as internal roads are worse. It's a surprise to see that it's still normal to have such roads connecting main towns. I learned that a festival called 'Aaoling' was celebrated in the first week of April to honor the arrival of spring. I wanted to go to a village where I could see the actual culture, and luckily I came across this homestay in a village called Sheanghah Chingyu. Google Maps showed no route to this place, but after speaking to the host, I figured that one shared taxi goes there in the morning, and locals commute from the main town to this village. It was a crazy 3-4 hours ride, mostly offroad. I was overwhelmed by the first glimpses of this village; it was so rustic as if modernization hardly seemed to touch this place. There was no modern house in the entire village.

Konyaks still have royal families heading the village, and they have an Angh ruling the entire village, and there are chief Anghs among whom different morungs are distributed. One chief Angh, Tonyei, hosted us at his rustic homestay. It has a thatched roof with bamboo, wooden beams, and Mithun skulls in front of the house. There were some guns, old spears, some used to fight and some used for peace treaty, skulls of birds (hornbills), and some old baskets woven from bananas and different plant fibers. (Every village has a blacksmith-carpenter who makes guns. They use gunpowder and metal pieces for firing.) Tonyei has a big family; he told us that Anghs and chief Anghs can have multiple marriages, unlike commoners. He could marry anyone from commoners and royal families from other villages. So Tonyei has 5 moms, and he became chief Angh because his mom is a princess from the village "Longwa". Longwa and Sheanghah Chingyu always had friction, just like all neighboring villages. Still, when there is a royal wedding, they come together as friends, but the friction soon begins. I wondered about the situation of the queens here; whose side they can really take, and whose wellbeing can they pray for.

On the first three days of the festival, Konyaks prepare new clothes, go hunting, and hold various competitions. I saw a competition where a small bamboo piece was hung with a thread at a distance. Whoever shoots this thread gets 10kgs of pork. I saw someone shooting it in the first go, and the rest were so disappointed that they started shooting in the air. At first, it was all scary and my instincts came up to be in between no many gun shots and be normal.At first, it was scary and my intuitions went haywire. However, with time, I trusted the people around me, and it felt as simple as crackers. During Aaoling, relatives and friends visit each other for meals, and Tonyei took us to one. It was a warm and memorable experience to dine with Konyaks in their own way. In their culture, during childhood, two children from the community are made best friends, and they will be there for each other for the rest of their years. During Aaoling, if there is a newborn in the family, they will pick someone of similar age as his or her best friend. I witnessed 2 kids around 11 months old being introduced as friends, and their families invited each other for a meal. It is such a thoughtfully introduced concept of having someone by your side whenever you need to share something.

On the third day, all men from the village dress in their traditional attires - hand-woven jackets, fancy old hats decorated with hornbill feathers, different bird feathers, board teeth, and colorful jewelry. They gather to sing and invite their spirit 'Wang Wan' to come and bless them for a good crop and health for the upcoming season. They go around the village and pause at multiple places to sing the Aaoling song. The prayer was so intense, chanted with deep voices. It was like a meditation to just indulge in their tones. Post that, they gather in a morung to beat the log drum. A huge tree trunk is hollowed, and each person holds small wooden pieces to bang against this log drum. The drum is used on multiple occasions - when someone from the royal family dies, someone attacks the village, or during festivals. Villagers understand the situation from the rhythm played. It's a 15-20mins long session with a variety of different beats played in perfect synchrony. It is one of the best musical sessions I experienced to date.

The fourth day is the main day; multiple competitions were held on the community grounds. Eating competitions, thread rolling competitions, shooting, and cart riding were some of them. There was a 15mins drama about how they used to attack a village and take an enemy head. One person who is head of the pack first enters slowly, with his face and body covered with soot to camouflage. He observes the situation and shouts for the pack to come, and all of them slowly surround the village in a formation. They take the head of the enemy and gather around for prayer. It was intense as everyone was deeply involved in their roles, and one could hear gunshots around. At that moment, I was overwhelmed with so many things competing for my attention. Post that, there were songs sung by women gathered in a circle, glorifying wang wan and his powers. In the evening, men gather, like on the first day, and sing to bid goodbye to wang wan and ask him to destroy the crops of their enemies on his way back.

The next day, all the villagers put up fences for their farms to protect them from animals. As they return, long drums are played as the closure of the Aaoling Festival. None of the Naga tribes have written scriptures. Konyak is the language common across Konyaks. However, every village again has its own dialect. Most of their cultures and practices are depicted through tattoos. Different tattoos signify different things in their society. The headhunter who brings back the enemy's head gets a face tattoo. They say only a warrior can take the pain of a face tattoo. Queen of the village is taught tattooing before she is married. It is done using thorns from specific trees and ink prepared from plant-based dyes. Since it's only 50-60 years since the practice was stopped, we met this region's last generation of headhunters. We got to meet one from the previous generation. He welcomed us with a warm smile and was the most cheerful man I met there. He started narrating multiple stories in the local dialect, and though we didn't understand much, his body language spoke a lot. He spoke about how he bled when he got a face tattoo. Now that he is a Christian, he doesn't want to talk much about headhunting days and takes no pride in it.

The story of headhunting practices and customs of Konyak tribes is fascinating, and it was a priceless experience to witness it first-hand. But what struck me harder is how the previous generation has seen life from different ends of the spectrum. It's hard to imagine how the transition happened and how they dealt with and molded it. He was 30 years old when it all stopped, and he is 83. We mostly see old people participating in all these diligently and practicing them with so much dedication while the younger generation has more spectators just like us. The younger generation here is struck in the phase where there are not enough resources and support from anyone to seamlessly come into modernization. At the same time, all the laws, changing lifestyles, and exposure to society can’t keep them intact to their traditional lifestyle.It felt like it was a hard phase to live in. At the same time, so many people went out and came back and realized how important it is to preserve their cultures, and they all worked in their own ways to achieve it. However, things are moving rapidly towards development, and soon all these traditions will become once upon a time, just like anywhere else. I am glad that I'm able to experience this and live a life not touched by modernization, at least for a few days.

By Ishan Singhal

By Ishan Singhal

Image source: The Times of India

Auto Rickshaws have been around for nearly 75 years now in India! Did you know that the mayor of Bengaluru, N Keshava, introduced India to autorickshaws in 1951 with a scooter fitted to a carriage. He himself rode passengers around to show off the possibility of the vehicle. N Keshava had to convince unions of horse carts and rickshaw pullers to see the potential of autos, and slowly then, Bengaluru and the rest of India accepted the auto rickshaws.

The first autorickshaw in Bangalore was introduced in December, 1950s and was designed in Pune

Lambretta Auto: The Iconic Movie Star Ride of the 1990s! A character in several movies including Dileep's 'Ezhu Sundara Rathrikal'.

A picture of one of the earliest models of Bajaj's auto in the 1990s in Goa.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

A hybrid of a rickshaw and a van was introduced in the 1960s in India by Force Motors under the model name Hanseat. In hilly regions of India, and many tier 2 and 3 towns in northern India, these can still be spotted.

Lambrettas used to shine in the city traffic with glass windows, bright chrome paints, and fringes. A rare few vehicles that evoke memories of the past still ply, like this revived by an enthusiast in Kerala.

Lambretta’s 1968 auto rickshaw model

Image source: Manorama Online

Lambretta’s 1968 auto rickshaw model

Image source: Manorama Online

Companions come in various forms - as a spouse, a friend, or even a pet! Over the years, I have come to enjoy a unique companionship. It is a bond I share with the ragas of classical music! A raga is not just a musical scale with an abstract sound form. One can experience the raga as though it is a full-blown human, each with a distinct persona. They speak a language without words. They can coax and cajole and leave you with goosebumps!

A chance hearing of U Srinivas’s mandolin changed my life forever. I had stumbled upon a treasure-chest. Like Silas Marner, that incurable miser, who sifted through his gold coins day after day, I did the same with ragas. I was hooked to them, mesmerized by their guiles and charms.

“Hamsadhvani”, I found, was jovial and chatty. “Hindolam” was cheerful. “Bilahari” bubbled with energy.

The day you felt sullen, you knew “Abheri” would pull you by the shoulder and take you for a brisk stroll. And then, there were ragas with a face so austere, you couldn’t help but gaze at them unblinkingly. The raga “Kambhoji” was one suchwith a personality that exuded majesty.

Some ragas chose to stay aloof. You hardly noticed them. Over time, they grew on you, revealing a new facet each time, till you were irresistibly drawn to them. Todi raga seemed an acquired taste until you fell head over heels with it!

Image source: Sekhar Roy

Image source: Sekhar Roy

It is easy to find a friend when the going is good. It is when the chips are down, that you need them most. Life throws you into situations where self-doubt and sadness stare at you in the face. Psychologists talk about “managing the emotion” through a catharsis of sorts. Shiva-ranjani raga falls in this category. You are moved by the raga’s palpable pathos. As tears roll down the face, the purgatory experience is total. At the end of it, you shake off the negativity and rise, all charged and refreshed.

An opposite approach works equally well- you deal with sadness using a counterweight- by cozying up to a raga that makes you instantly happy. Mohana Kalyani is happiness personified- spreading joy like a cascading waterfall. It sweeps you off your feet with its overflowing effervescence!

Our companionship with ragas is often triggered through specific kritis set in those ragas. These kritis give a concrete shape and enhance a particular aspect of the raga. We are forever indebted to these master composers.

Among the composers, Tyagaraja’s masterpieces are many. In the kriti “chakkani raaja maarga”, set to the raga Kharaharapriya, through song, he has created an interesting imagery. Tyagaraja was a bhakta of Lord Rama. He wants to convey the superiority of Rama upasana to other forms of worship. In this kriti, he asks, “When we have a raaja-maarga, a royal path, like Rama upasana maarga, why do we need to use any other method?” To convey this point, Tyagaraja imbues the phrase chakkani-raaja-marga with the sound of a horse-chariot trotting on a paved highway. The “sangatis” of the raga Kharaharapriya create that illusion- as though the horse is trotting on the maarga now slowly and now galloping at top speed!

To listen to the kriti “Amba Kamakshi” by the composer Shyama Sastry is an experience. Set to the raga Bhairavi, it is composed like a “gopuram”, a temple tower. Each line of the kriti begins with the next ascending swara, as though you are climbing up the temple tower. And once you hit the line in the highest octave in Bhairavi, you are as though, at the top of the temple edifice. The song comes to a climactic finish. You can feel the presence of Mother Goddess in all her finery Such is the beauty in this composition and the grandeur of raga Bhairavi.

Muthuswamy Dikshitar’s “navaavarana” kritis have a unique construct. The “shri-chakra” is a diagram, a geometric representation of Devi, made up of triangles and circles. The “nava-aavarana kritis” -9 of them in 9 different ragas, take you progressively through the nine corridors till you reach the center of the geometric pattern called the “bindu”, where Devi is manifest The lyrics and the ragas are captivating. As you listen to them with rapt attention, you are transported to that Divine presence

These are but little examples to show how music can be used as “maanasa puja”- a form of meditation. You listen to the songs, travel with them, and experience both the feeling and the divine form that these composers wish to convey.

And the day you wanted to simply unwind with something “light”, you listened to “magudi” set to the raga Punnaaga-varaali. The raga is soaked with the mesmeric tune that the snake charmer uses to stoke the snake. You can feel the swerve and wave of the snake, in each phrase of “magudi”!

Ragas are like Ganga’s tributariesThe Alakananda, The Mandakini and several tiny Himalayan streams. They traverse their own terrain with their distinct identity. Eventually, they join The Bhaagirathi to become inseparable companions in River Ganga’s onward march to the ocean.

So too, we are glad these ragas found us, walked with us, and became intimate companions in our journey through life!

I hope you enjoy an account of the Park

As a spirited traveler and wildlife enthusiast, I love leaving for forests to unwind and seek refuge from the daily stressors of city life. One of my favourite summer adventures is to go to the verdant forests of Jim Corbett. I always find an instant connection with the National Park for some unknown reason. Nestled in the foothills of the Himalayas, it’s beyond words when I am surrounded by the greenery near the meandering Kosi River.

through my Canvas.

Established in 1936, the park was originally named Hailey National Park after William Malcolm Hailey, a governor of the United Provinces. It was in 1956 that it was renamed after the famous hunter-turned-conservationist Jim Corbett. This honour was bestowed on him for his heroic feat in killing man-eating tigers and then working with his team to set up a conservation area for the big cats who were slowly getting pushed to the brink of extinction.

The forests in the reserve are lush thanks to the deciduous trees of Sal along with Khair, Sain, Haldu, and Peepal. The waters of the Ramganga River form the lifeline of the park and play a key role in attracting and sustaining wildlife.

While the majestic landscape of Corbett is well-known for its more than 200 Royal Bengal Tigers, visitors are often left spellbound by the sights of the Asian elephant, Gharial, King cobra, and countless Avian species. More than 500 species of birds dwell in the reserve, and the forest comes alive in the evenings with their unending chirpings.

There are many pressures of maintaining the rich bio-diversity in the park, including managing the needs of the villagers living on the outskirts of the jungle and pollution caused by the tourism industry, which sees more than 250,000 tourists yearly.

I don’t pretend to have the answer to the incredibly tough questions on the way forward in sustaining the well-being of all stakeholders, but I hope that my earnest attempt to capture the park’s beauty is not lost on anyone.

I have (almost) never heard Pt. Kumar Gandharva in a live concert. I have not been able to visit his abode in Dewas. I have not had the good fortune to have ever met him in person, seek his blessings or just be in the same space where he breathed, lived, smiled, regaled, enraptured and captivated the minds and hearts of millions of classical music lovers. But I sure have listened to his music intently and extensively, seen and heard him speak on music in several of his recorded interviews and read every bit of literature available about him. (Kumar ji is possibly one of the most documented and recorded artists in the modern era).I also have had the good fortune to learn from two of his senior disciples (Pt. Vijay Sardeshmukh and Pt. Satyasheel Deshpande), met several of his other disciples, interacted and interviewed dozens of his friends, associates, ardent lovers, contemporaries, foes and haters!

Over the years, thanks to all the information, anecdotes, deep learnings, personal engagements, discussions and debates with musician friends, ruminations and wisdom shared by many Kumar lovers/devotees, have I been able to stitch an image of the man, who remained, for most part of his life, an enigma. Labelled as a rebel, a disruptionist, an unorthodox and iconoclastic radical, Kumar ji was a puzzle, an ‘elephantine’ mystery that many ‘blind’ men and women have tried unravelling. (The story of the six blind men and the elephant). I feel I am just one of them. It is 30 years now that this supremely gifted musician has left us, and yet the magnetism of his music and his thoughts continue to pull us into his gravitational orbit, almost provoking us to challenge him or accept defeat!

Pandit Kumar Gandharva has several ragas to his credit

I do have a vague recollection of seeing him just once. Dressed in a spotless white kurta and loose lenga, he walked leisurely from the green room of Laxmi Krida Mandir in Pune to the stage. I remember him singing Raag Shankara and me requesting my mother that we leave the concert in the midnight interval (the only such exception in my memory) since I just was not able to understand a thing about his music! Also, I had to be in school by 7am the next morning after all! But as years passed by, fate brought me back to his alluring music. I think it was bound to be!

Nirbhay Nirgun gun re gaunga…After this initial bumpy start, my second introduction to Kumar ji was through ‘Mala Umajalele Balgandharva’, as it was for most Maharashtrian families then. It was this cassette tape and Kumar ji’s rendition of ‘Nayane lajavita’ that was responsible for destroying my tape-recorder’s head, since I must have rewound-played-forwarded it a zillion times! During my training with Pt. Vijay Koparkar, I started listening to Kumar ji more carefully and was completely enamoured by it.

I sang some of his bandish and found a freshness in them, that I had not experienced before. A few years rolled by and circumstances led me to learn from Pt. Vijay Sardeshmukh, possibly the most authentic and absorbent disciple of Kumar ji. It was in the calming presence of Vijay dada that I could find the Shadja in my voice as well as the Shadja of Kumar Gandharva gayaki. Freewheeling discussions with Vijay dada on the framework of ‘Kumar thought’ led to the decoding of ’Mukkaam Vashi’ and the revelation of a brand-new musical territory. Pt. Satyasheel Deshpande pointed out and articulated the openness and eclecticism of Kumar ji’s musical philosophy and forced me to think about Kumar ji in a more scholar-like, if not scholarly manner. Whatever understanding that I have been able to achieve about Kumar ji, is from this long and continued search through these varied, diverse and rich engagements as well as my own contemplation. As a third generation Kumar follower, I possibly have a different perspective than his disciples, family and motley breed of Kumar ‘bhakts’.

Pt. Kumar Gandharva was undoubtedly a leading intellectual and vocalist par excellence among Hindustani classical musicians of the 20th Century, whose original style and refusal to stay within the confines of the gharana traditions made him a controversial figure. Much has been written about his life and works ranging from the biographical to the critical. Pt. Kumar Gandharva’s contribution to Hindustani music is celebrated not just for its qualitative aspect but also for its wide expanse. His experimentative musicianship was not confined to any one genre and included a wide array of khayals in common raags, rare and complex raags, raags created by him, thumris, taranas, tappas, bhajans, folk songs, Marathi bhavgeets and natya geets. Some critics believe that his greatest contribution was to the maturation of the ‘bhajan’, which he is said to have elevated and gave the character and status of a distinct genre on the classical music platform. Kumarji’s interpretative experimentation was not based on the denying of legitimacy or suggestion of irrelevance/obsolescence of the current or past traditions. It was based on the spirit of a genuine search of the original inspirations of prevalent music and revive the original thrusts/spirit of genres, in order to establish a more personal, constructive and contemporary connection with it.

Kumar ji’s experimentalist contribution can be broadly classified into two categories namely selfcompositions, comprising his creations in terms of new bandishs, raags and raag-roops and secondly his self-productions comprising the series of ‘thematic concerts’ that he conceptualized and presented. A cursory look at the log maintained by Kumar ji documenting his bandish creations (available only for second volume of Anoopraagvilaas) reveals that Kumar ji’s first bandish was composed on 08-11-1943 (‘Bairana barakha ritu’ in Raag Madhuwanti, the lyrics of which were possibly not his own) in Bombay and his last on 06-10-1987 (‘Mai ka chaina na parego’ in Raag Chaya Kalyan) in Dewas.

One finds several instances in which the sthayi of a particular bandish was composed on one date and the antara got composed several weeks/months or even years later! At times, the details of travels are mentioned too when he got inspired and composed a particular bandish or a part of it.

E.g., The sthayi of ‘Pawa mai durase’ in Raag Shree was composed on 30-11-1967 ‘enroute a train journey from Mumbai to Nagpur’ while the antara got composed on 05-01-1975 in Dewas. This points to the perfectionist attitude of Kumar ji as also his ‘non-interference’ in the organic and artistic process of bandishs ’getting composed’ than ‘composing by force’. It also reflects on his patience, insistence on exactitude and meticulous nature. These bandish creations of Kumar ji were the natural outcome of his musical, mental and emotional states at the time of their creation. They were artistic expressions of his innate urge to convey something that goes beyond language and the grammar of raag-taal. They were not made with the purpose of furthering any social or cultural agenda or as crystallized expressions of formulated gharana aesthetics.

Pandit Kumar Gandharva is famous for performing many of Kabir's poems and bringing out their essence.

An early recording of Pandit Kumar Gandharva ji concert that is unique and quite a treat for the listeners.

Pandit Kumar Gandharva is famous for performing many of Kabir's poems and bringing out their essence.

An early recording of Pandit Kumar Gandharva ji concert that is unique and quite a treat for the listeners.

Kumar ji’s bandishs do not seem to be set in a particular kind of mould but display a diversity of approaches, themes and architectural strategies.The resultant impact of his bandishs is, hence, equally varied. But of all the unique characteristics in his bandishs, the usage of malwi dialect stands out and is the first to be noticed. One can observe this malwi inclination, in addition to the conventional braj dialect, in most of Kumar ji’s bandishs. Hence the semantics of his bandishs, at times, is not as easily seen. In some bandishs however it is seen in its full glory, but again, with a ‘Kumar twist’! Such usage appears to be Kumar ji’s effortless and organic linguistic response to the environment around him and possibly an expression of the self-sufficient well-being of Malwa region and its inhabitants. Interestingly, not all bandishs appear to have been made for presentations on the concert stage.

Some seem to be directed inwards, almost akin to private self-conversations while some have a recitative nature. It is evident that Kumar ji’s study of the vast repertoire of traditional bandishs is the bedrock of his own bandish creation. Hence one finds some of his bandishs are like showcases of his study of different gharanas and seem to bear the unmistakable seal of a particular gharana. Musicians belonging to different gharanas are likely to find particular bandishs as if they were tailor-made for them and belong to the traditional mould of their respective gharanas.

Thanks to Kumar ji’s discipleship with scholar-musician Guru B. R. Deodhar, Kumar ji had acquired a very wide, eclectic and progressive outlook which enabled him to appreciate the different aesthetic approaches taken by stalwart musicians. Since childhood, he had observed, listened and learnt from diverse sources, critically analysed their music and assimilated what suited his idea of ‘artistic music’. This individualistic blend was unlike any other musician’ before him and did not seem to fit in the standardized and accepted existing framework of any of the gharanas. Considered novel, pioneering, rebellious and utterly original, ‘Kumar-gayaki’ created a storm in the

A Bal Gandharva showing glimpses of the Pandit ji he would go on to become.

A Bal Gandharva showing glimpses of the Pandit ji he would go on to become.

To a large extent, a classical singer’s gayaki is determined by his voice. Understanding and accepting one’s voice, with all of its inevitable limitations and building upon its inherent strengths and dynamism, is an ongoing life-long exercise that a musician indulges in. Kumar ji's voice can be described as thin, pointed, high pitched, sharp, resonant, tuneful and fast moving in energetic but short bursts. Much of Kumar ji’s overall uniqueness in the popular perception can be attributed to his distinct voice quality and enunciation. His voice was highly flexible and was able to closely execute subtle rhythmic and melodic nuances. While his vocal range was limited, he had an extremely wide dynamic range, from a barely audible whispering volume to an open throated loud throw. He was also able to achieve this shift from extreme softness to extreme loudness within no time, lending his music a dramatic flourish. Kumar ji’s deep contemplation on the nature of swar (either during his learning from Anjalibai Malpekar or during his bed-ridden state in Dewas during 1947-52 or both) reflects in his extreme tunefulness and the ability to employ unconventional pitch values of notes. This feat was achieved by him precisely and unfailingly each time he wanted to introduce an emotive quality to the music or subject material being presented. The impact of folk music also should be mentioned here in this regard.

Kumar ji pointedly employed certain specific swar-sthans or shrutis of swars (although he almost never referred to them as shrutis) in certain raags. These swar points were not necessarily used ‘in transition’ from one note to the other, but many a times in a direct and sustained manner. He was particular about the pinpointedness of swar which was achieved with abundant usage of vowels sounds. Such pointed tonal projections made his vocalism rather sharp and angular. Kumar ji did not follow the step-by-step Paluskar/Vidyalayeenbadhat method for his overall elaboration but instead chose the old-school upaj based Gwalior aesthetic. He did not believe in the rigid sequential presentation of phases like alap, bol-alap, bol-taan, taan etc, which is the usual framework of ashtanggayaki in khayal. Instead, Kumar ji gave primacy to the ‘bandish’ and chose only those elaborative tools from the ashtang basket that were suitable for the improvisation of that bandish. The poetic sense and meaning of the words of the bandish was not sacrificed completely for the raag-taal aspect and an overall sculptural balance was sought. This thought is not an original construct of Kumar ji but an old tenet of the Gwalior stream as that went, “ब�दश दख क गाओ”. Kumar ji explored the ‘song’ in the raag as perceived within the bandish. In Kumar ji’s vilambit, one finds a marked use of ‘silence’ as much as ‘sound’. His phrases appeared spaced away and short. This style of singing in short phrases has been erroneously attributed entirely to his one (dis)functional lung. Such an explanation appears rather simplistic and devoid of merit. Kumar ji believed that ‘beauty lies in miniaturization’ and did not consider lung capacity as an essential or aesthetic musical element or quality. Also, his innate sense of design suggested that an aesthetic and meaningful design is possible only with short segments/fragments and not long lines. In an interview, he mentions that the sound of his perfectly tuned tanpuras, fills those silence gaps and continue to sing the raag for him!

Another aspect of Kumar ji’s gayaki is his usage of mukhda as a unit for improvisation. Instead of treating the mukhda as the final touch point at the end of each avartan, Kumar ji used it as a source for improvisatory suggestions. The melodic and rhythmic directions suggested by the mukhda were explored organically in avartan after avartan, which by itself became the improvisation of that bandish. Such playful handling of the mukhda is seen in his singing of madhya and drut laya bandish-s. The elements of ‘aghaat’ and ‘sauvaad’, in all their manifestations and meanings, were central to Kumar ji’s musical formulation.

Kumar ji processed the rare ability to present the same bandish with renewed vitality each time he sang it. In an interview he mentions, “I forget what I sing as soon as the performance ends’. In a lecture in Pune in the year 1972, he had said, ‘I prepare a lot before a concert. But I forget everything soon after. I don’t repeat my singing. I never listen to my own recordings. My records are for others, not for me. I am afraid of listening to them. It is the fear of repeating myself! If Kumar Gandharva has to ever stoop to repeating himself, he will give up singing.

In hindsight, one can say that it would be rather unfair and unjust to keep branding Kumar ji as a rebel. He was, in all probability, only being himself, steadfastly questioning the existing contemporary formulations by almost weaponizing tradition itself and bringing forth excavated material that lay hidden under the sedimented layers of tradition. As we celebrate his 100th birth anniversary year, I wonder whether it would be appropriate to look at Kumar Gandharva in a more dispassionate way and revisit, relook, rethink and recontextualize his musical thoughts for today. Afterall, questioning status quo is what Kumar ji stood for all his life and could arguably be considered as the very essence of his nature.

A true celebration of Pt. Kumar Gandharva would mean celebrating the ideals he stood for, the inquisitorial attitude that he lived with and the unwavering quest for new meanings.

Chamini Weerasooriya

Chamini Weerasooriya

Just as Ramayana connects India to the Emerald isle to its south, it is Buddhism that makes the bond between the two nation tenacious. The ties go back to a hoary past, to times when Asoka was the Chakarvartin and even further when Buddha is said to have visited the jewel of a nation. Since times undated ideas have travelled back and forth between Sri Lanka and India.

Chamini, came across as a trail blazer, a pioneer in her own right. She is the first woman temple artist from Sri Lanka. She is married to an Indian Buddhist and has made Nagpur her second home. In her initial travels she was dismayed by the state of Buddhist Viharas in India and took upon herself to revive the age-old traditions by painting the interiors of the viharas herself! She has been spreading the message of Buddha through her paintings and talks at various conferences in India. She was an important speaker at a Buddhist Conclave held in 2022, where she spoke in Hindi, on the position of women in Buddhism.

By a lovely coincidence, I got to interact with her during the month of Buddha Purnima and learnt more about her thoughts on the interplay between faith and art. I put aside my pre-conceptions of the hegemonic artistic tradition of Ajanta. Chamini admits Ajanta’s dominant influence. “Rightfully it can be said that the history of painting in Sri Lanka is also the story of the spread of Buddhism in the island. Sri Lanka has a rich tradition of Buddhist paintings. The purpose of paintings was to communicate the essence of Buddhism to devotees.”

The purpose gave an impetus to great many styles and modes of presentation. Sri Lankan artists adapted the medium according to their own interpretation. Today we witness many regional styles right from the ancient times of Anuradhapura, Pollanaru, to medieval Kandyan to the modern academic styles and the more recent styles made popular by George Keyt and the Colombo 43 group. Interestingly the evolution of art in India and Sri Lanka has followed a similar pattern which became evident after witnessing Chamini’s personal artistic journey.

She was born in Anuradhapura, the gateway to Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Devanampiya Tissa adopted Buddhism and built the earliest monastic complex- the Mahavihara in Third century BCE. The king invited Sanghamitta to settle in Anuradhapura who came bearing the cutting from the Bodhi tree which was planted at the Mahavihara. The cutting spread deep and wide, both metaphorically and literally, and it lives even today.

Many reasons are attributed for the vibrant Buddhist faith in Sri Lanka. A key role was played by local viharas and their Dhamma school. The ancients understood the power of visual medium in communicating the message of the compassionate one. The walls of the viharas and stupas came alive with scenes from the life of Buddha -Birth of Buddha, the world outside the palace, young Siddhartha leaving the sleeping Rahul, the enlightenment, the first sermon and the Mahaparinirvana Buddha looking down the walls going through the life’s turbulations with acceptance and a gentle smile subtly hypnotised the laity to surrender and embrace the path walked by Buddha.

The Dhamma school in Anuradhapura gave the first opportunity to the young Chamini all of 13 years to dabble in temple art. Her first drawings were of stupas at Lalaththewa Mahavidyalaya, a Buddhist vihara in Anuradhapura. The early memories of simple white stupas were a stark reminder of what was missing in Nagpur. The clear absence of a subtle initiation into the Buddhist way of life propelled her to embrace her life’s purpose - to communicate the forgotten glory of Buddhism though paintings in India. Her masters in Fine Art from the University of Kelaniya and her early exposure in the Dhamma schools equipped her to embrace her calling.

Her first job was at Kebithigollewa Central College as an art teacher. But the blackboards of her school could not reign in her desire to be a temple artist. The Anuradhapura Puraanagama Vihara gave her the first crucial break in 2017. Mindful of her legacy and paying homage to the art tradition of Anuradhapura she chose the style to paint her first murals of Buddha with his first five disciples in the classical style of Sri Lanka. This style is known for its strong line drawing and the use of colours like red, brown, dark red, yellow and white, shading within the lines create an impression of depth and the figures come alive in the soft glow of the lit lamps.

The lyrical quality and the realism of Anuradhapura style have a first claim to heart, yet she had not hesitated to follow other schools and artists in search of honing her own style . Chamini has a deep reverence for M. Sarlis. He was instrumental in restoring Buddhist art in face of challenges posed by European art. Buddhist art was losing out to Christian art as it was patronized by Christians and the colonial powers in Ceylon of Nineteenth century. The compassionate one was replaced by the cold distant face of British royalty in the Buddhist homes. It was master Sarlis who brought a new vigour to the Buddhist Art. He painted scenes from the life of Buddha which could be used as wall decorations. Although he was influenced by European techniques and colours his theme was Buddhist. His re invention of Buddhist art in Sri Lanka reminds one of the works done by Raja Ravi Varma in restoring traditional art in India.

Chamini got a chance to pay homage to master Sarlis when she restored the paintings at Sri Sidhartharamaya in Colombo in 2018 which were done by Sarlis. Chamini admires his work but she finds his technique very European and distant from the Sri Lankan traditional style.

She has worked in another important regional style -The Kandyan school. She was commissioned to work on Gampola Bodhirukkharamaya in 2019. Gampola Bodirukkharamaya is inspired by the Kandyan school, a school that laid great emphasis on line drawing with limited color palette.

Since the time she started painting she has been working hard to find her own style of interpreting the message of Buddha. She has worked on different aspects of Temple art, from painting the

Buddha with his disciples, to restoration work, to indulging in Sinhalese temple decorations which are an integral part of temple art in Sri Lanka. She got a chance to indulge in this form and painted lotuses, swans to adorn the ceilings of Anuradhapura Shailabhimbaramaya.

She admires the work of Solias Mendis, the revivalist who brought back traditional art to the forefront, akin to the Bengal School of Art in India which broke the monopoly of the Company school of painting in India.

While drawing the Sadagiri Vihara paintings she drew heavily from Mendis - the rhythmic line drawing, full bodied figures, fine detailing of dress and jewels, the expressive lift of eyebrows, the curl of the upper lip, the wrinkled forehead reveal the influence of Mendis on her work.

The watershed moment was when she moved to Nagpur with her husband. The state of Viharas in India and Nagpur in particular filled her with shock. She had expected to find Viharas glowing with murals and the countryside reverberating with the chants of Dhamma. Contrary to her expectations the scene was bleak and in India. She resolved to restore temple art one vihara at a time. She began her journey on her birthday – March 10th when she painted the scene of the birth of Buddha at Nagpur Bodhigaya Vihar in 2020. The style was inspired by the sights and smells of India. Despite being in the neighbourhood of Ajanta she chose to paint dream of Queen Maya in bright colours in a typical Bollywood fashion.

In retrospect she is critical of her Bollywood inspired art. Doing a course correction she went back to neutral or limited palette, delicate lines, soft expressions, fluid movement to convey a feeling of serenity and a sense of bliss.

Her passion for painting and her calling came together in India. Her art still had to find a voice of her own. She increasingly wrestled with the existential crisis about her uniqueness. At this stage she was increasingly pulled by Japanese and Chinese paintings. Hanthana Sadagiri Stupa done in 2021 glows in style which Chamini calls her own. It is a composite style that borrows freely from Japan, China, Thai Ballet dancers, Bollywood and the traditional art styles of Sri Lanka. The murals at Hanthana make a statement for Pan Asian art. They reveal the subtle linkages.

At her core, Chamini Weerasooriya is a traditional temple artist who likes to follow the ancient style of Anuradhapura. Murals of Anuradhapura involved preparing the surface with clay, extracting colours from plant or mineral sources, fastening the colours by mixing it with oil from Doranaplant. However, it is difficult to practice these processes in present times. Doronaplant has become extinct and its usage is prohibited. Chamini has started using acrylic colours, her heart beats with the classical style of Anuradhapura which she interprets with the aid of Pan Asian Styles.

Traveling with her through her painted walls one is wonder struck by the stylistic nuances of Sri Lankan art traditions. One realises the mistake in assuming that art in South Asia is an offshoot of Ajanta. Ajanta is a great source of inspiration but each region had its own style and the local artists interpreted the stories according to the socioeconomic cultural conditions of their time.

One can see a connection emerge between Bhikshuni Sanghamitta and the modern-day temple artist Chamini_- one crossed the ocean and made Anuradhapura her home while the other flew across the strait and made Nagpur her abode, a karmic cycle of debt and repayment in the most wonderful sense seems to be at play.

Share your email address here to receive the next edition in your inbox.

Venu Dorairaj

Satyameet Singh

Ramya Mudumba

Dr. TLN Swamy (Advisor)

Dr. DVK Vasudevan (Advisor)

Lakshmi Sanjanaa Bhavaraju

205 Rangaprasad Enclave

Vinayak Nagar, Gachibowli, Hyderabad

Telangana 500032

Founded in 2005 by Guru Violin Vasu and friends, the mission of Sanskriti Foundation is to promote Indian art, culture, and values by conducting training, workshops and an annual Tyagaraja Aradhana music festival. Foundation members benefit from meeting like-minded people, attending cultural seminars and bimonthly concerts.

If you would like to learn more and become a member, you can reach us here: http://www.sanskritifoundation.in.