HE TIROHANGA AROTAKE 2024

Four-year Audit Report

PURSUANT TO SECTION 106 OF THE MĀORI FISHERIES ACT 2004

Four-year Audit Report

PURSUANT TO SECTION 106 OF THE MĀORI FISHERIES ACT 2004

Appendix A Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana | Te Ohu Kai Moana

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix

Appendix F

Appendix

Appendix H

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana

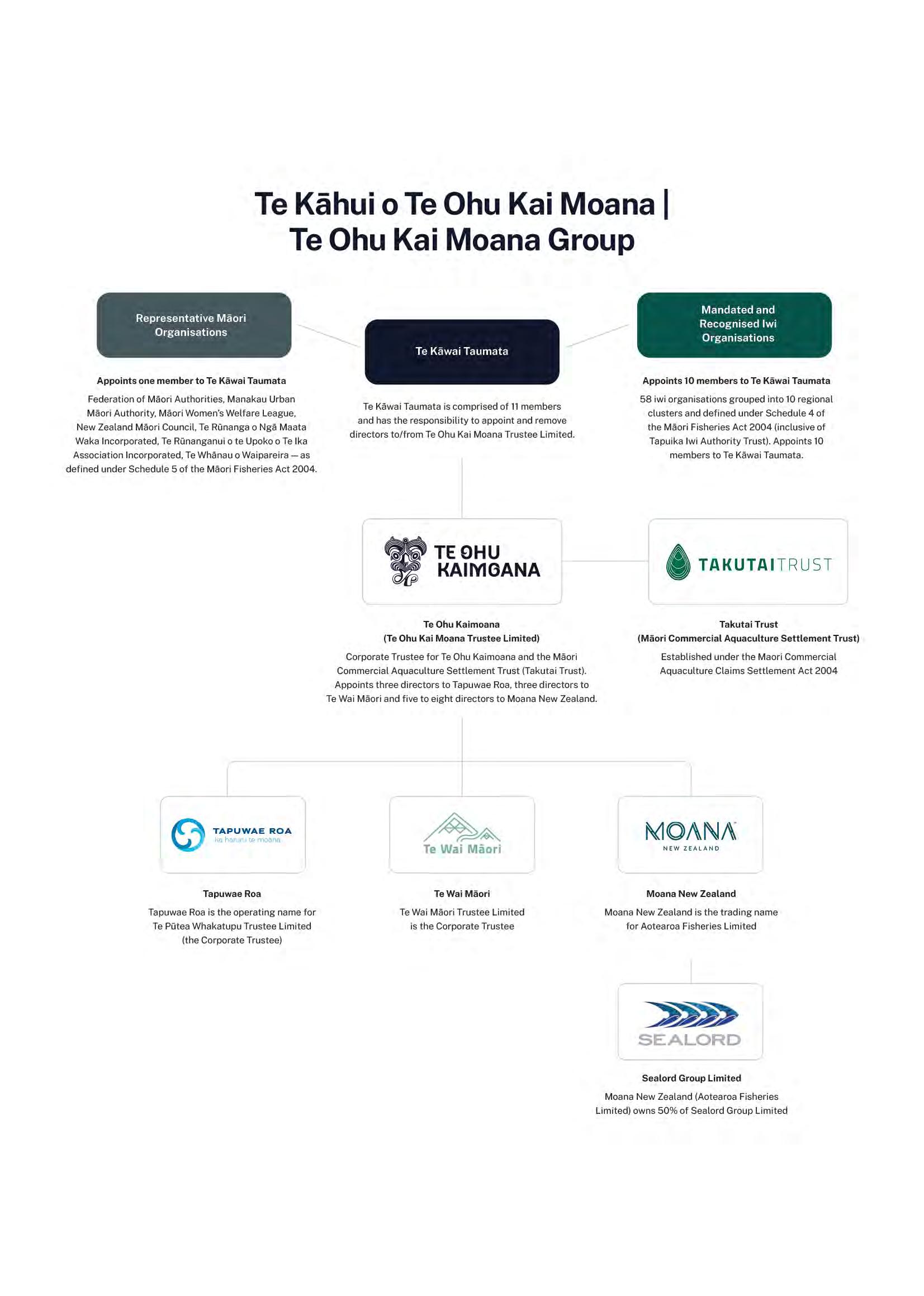

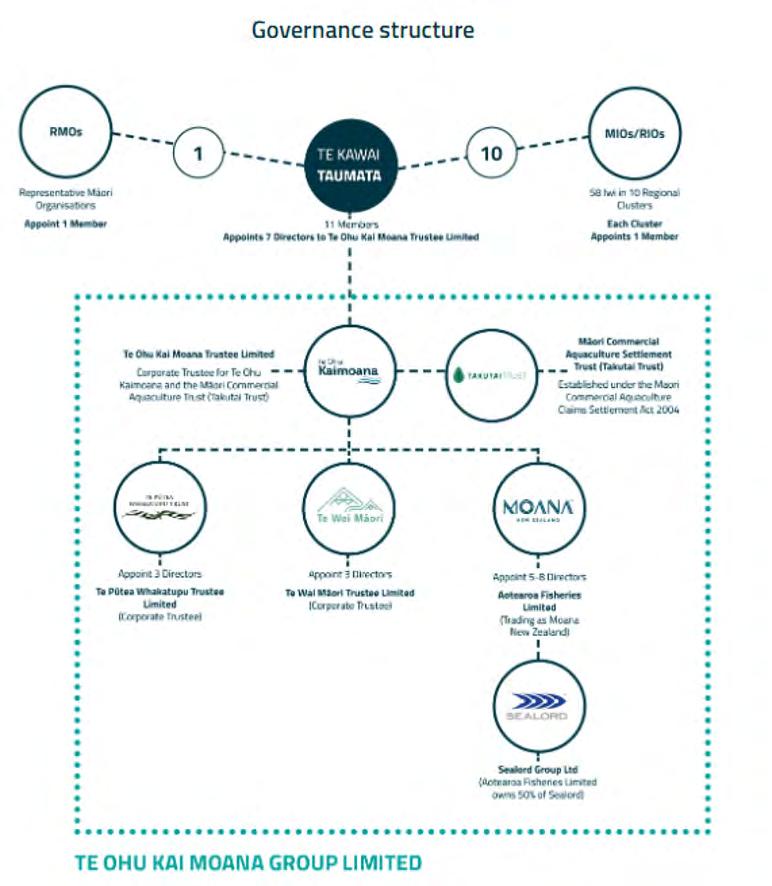

1. Under the Māori Fisheries Act 2004,1 a four-year audit from October 2020 until September 2024 (inclusive) is required to consider and report on the performance and effectiveness of each of the four entities of Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana. Those four entities are:

1.1. Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited (referred to in this report as ‘Te Ohu Kai Moana’);

1.2. Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited (or Te Wai Māori for ease of reference in this report) 2;

1.3. Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited (now trading as Tapuwae Roa); and

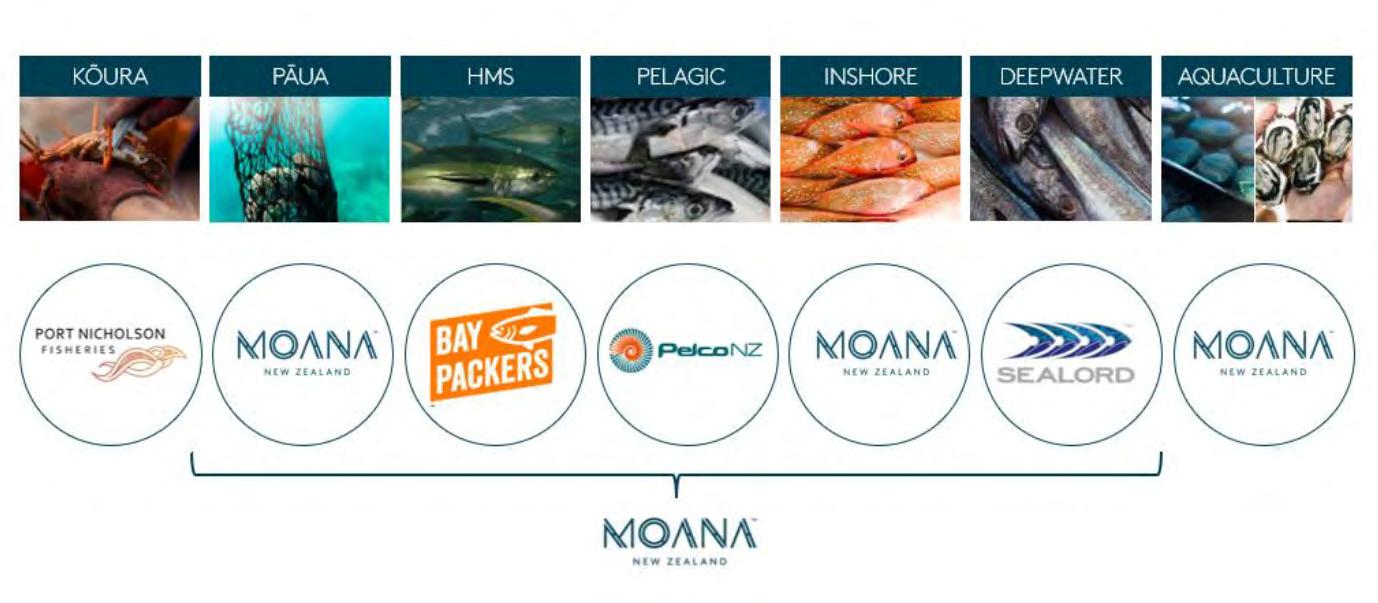

1.4. Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (trading as Moana Fisheries Limited).

2. When discussing the Kāhui in the context of this four-year audit, we are specifically meaning those entities subject to this audit process under the Māori Fisheries Act. In saying that, we are conscious that it is used beyond the confines of this statutorily orientated audit as extending to Sealord in addition to the four entities listed above.

3. In essence, we have found that each of the four entities of Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana is meeting those requirements that the four-year audit has been asked to consider and report on under s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act. That is:

3.1. Each board has established objectives as required under s 108(a) of the Māori Fisheries Act.

3.2. Those objectives appear consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions of the entity under the Māori Fisheries Act or any other enactment (s 108(b) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

3.3. We are broadly satisfied that each board is making progress towards achieving the objectives (s 108(c) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

3.4. The boards of each entity have established policies and strategies aiming to achieve the objectives and perform the duties and functions of the board and its directors (s 108(d) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

4. Given our compressed timeframe, this four-year audit has been undertaken largely as a desktop exercise, relying on the self-assessment materials from each entity and their documentation and supplemented with a range of key stakeholder interviews. The objectives are invariably presented attractively in polished strategy papers, as are the policies and strategies. Iwi perspectives have proven vital to us, as have free and frank discussions with representatives of the governance and executive levels in each entity.

5. We have endeavored to assess performance based on the alignment between the objectives and priorities set, and the achievements and impact on iwi and Māori outcomes related to the Māori Fisheries Settlement, with the respective purposes, duties and functions of each entity borne in mind throughout. In essence, how well do the priorities and objectives align with the duties and functions of an entity, and to what extent have the priorities and objectives been achieved. We are required to assess ‘effectiveness’ and ‘progress’ and to do so independently.

1. Note that we repeat the date of the Māori Fisheries Act in each new section for one of the four entities.

2. Please note that this four-year audit report uses the macron even though the Māori Fisheries Act 2004 itself did not do so. In this sense, we are following the orthography used by the entities themselves but have kept as far as possible to the names used in the legislation rather than using trading or brand names.

5.1. To the best of our knowledge, the policies and strategies referred to immediately above (that is, under s 108(d) of the Māori Fisheries Act) are effective (s 108(e) of the Māori Fisheries Act). We have assessed this aspect on the basis of feedback received, engagement with representatives of each entity at management and governance level, and the various business planning, reporting, operational and self-assessment documents provided to us by the four entities.

5.2. Caution has to be expressed, however, given that iwi feedback was not always clear on what each entity actually did or where effectiveness in terms of each entity’s outcomes was occurring. We consider there is opportunity for the four entities to define and measure more clearly how their strategic priorities, objectives and actions are changing iwi and Māori outcomes for the better. This could include outcomes in relation to education, training and participation in the industry; healthier waterways and native fish stocks; greater economic returns and value of assets; or a stronger position as the Treaty partner in the Māori fisheries settlement.

5.3. One board member of Moana New Zealand (Aotearoa Fisheries Limited) we spoke to acknowledged that the coordination and alignment of approaches could be improved on, as well as communication regarding what the entities in Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana did. 3

5.4. We are satisfied with the quality and timeliness of the reporting documents prepared to meet the reporting obligations under the Māori Fisheries Act or another enactment (refer to s 108(f) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

6. In looking at the particular requirements that we must then consider and report on for each entity respectively, we are also able to report that we are satisfied with overall compliance and performance. These specific requirements are to be found in the following provisions of the Māori Fisheries Act:

6.1. Te Ohu Kai Moana: With Te Ohu Kai Moana the audit has to consider and report on (1) the progress that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards allocating and transferring settlement assets; and (2) the contribution that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards assisting iwi meet the requirements for recognition as mandated iwi organisations (s 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act). In its self-assessment, Te Ohu Kai Moana reported that during the past four years substantive progress continues to be made. Accordingly, in 2024, ‘there are a total of 58 Iwi organisations after Tapuika withdrew from the Te Arawa Joint Mandated Iwi Organisation’. The self-assessment then says that ‘Of those, 56 are Mandated Iwi Organisations’, and ‘Te Ohu Kaimoana has continued to support the two remaining Recognised Iwi Organisations to achieve Mandated status’.

6.2. Te Wai Māori: ‘In the case of Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited, an audit must consider and report on the contribution that Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited has made in advancing the interests of Māori in freshwater fisheries’ (s 111(2) of the Māori Fisheries Act). The ‘contribution’ that Te Wai Māori has made in ‘advancing the interests of Māori in freshwater fisheries’ is an active obligation. The Trust has established a strategic focus on supporting Māori interests in freshwater fisheries and protecting the habitat to ensure the quality of freshwater and abundant species. With diminished stocks of freshwater species and iwi shelving quota in recognition of this, we consider this to be a sound focus. Te Wai Māori’s efforts in supporting local revitalisation and data collection projects and building national networks of iwi and Māori freshwater fisheries stakeholders to share their knowledge and expertise does constitute advancement in our view.

6.3. Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited: The auditors must consider and report on ‘the contribution that Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited has made towards promoting education, training, and research in relation to Māori involvement in fisheries, fishing, and fisheries-related activities’ (s 111(1) of the Māori Fisheries Act). We saw satisfactory evidence of this during our assessment. In the last one to two years, the Trust has adopted a new theory of change, resulting in a clearer focus on activities to support young Māori gain higher-level skills and experience directly applicable and more universally relevant to the

3. Interview with some of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited’s senior management and board and on 27 September 2024.

fisheries and other industries. We consider that this is a positive strategic shift and sound platform for performance improvement going forward.

6.4. Aotearoa Fisheries Limited: Under s 110 of the Māori Fisheries Act, the auditors must consider and report on:

6.4.1. The performance of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited in meeting its constitutional requirement to work co-operatively with iwi on commercial matters; and

6.4.2. The commercial performance of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited in comparison with other participants in the fishing industry, including its net profit after tax as determined in accordance with generally accepted accounting practice, and changes in the value of the company.

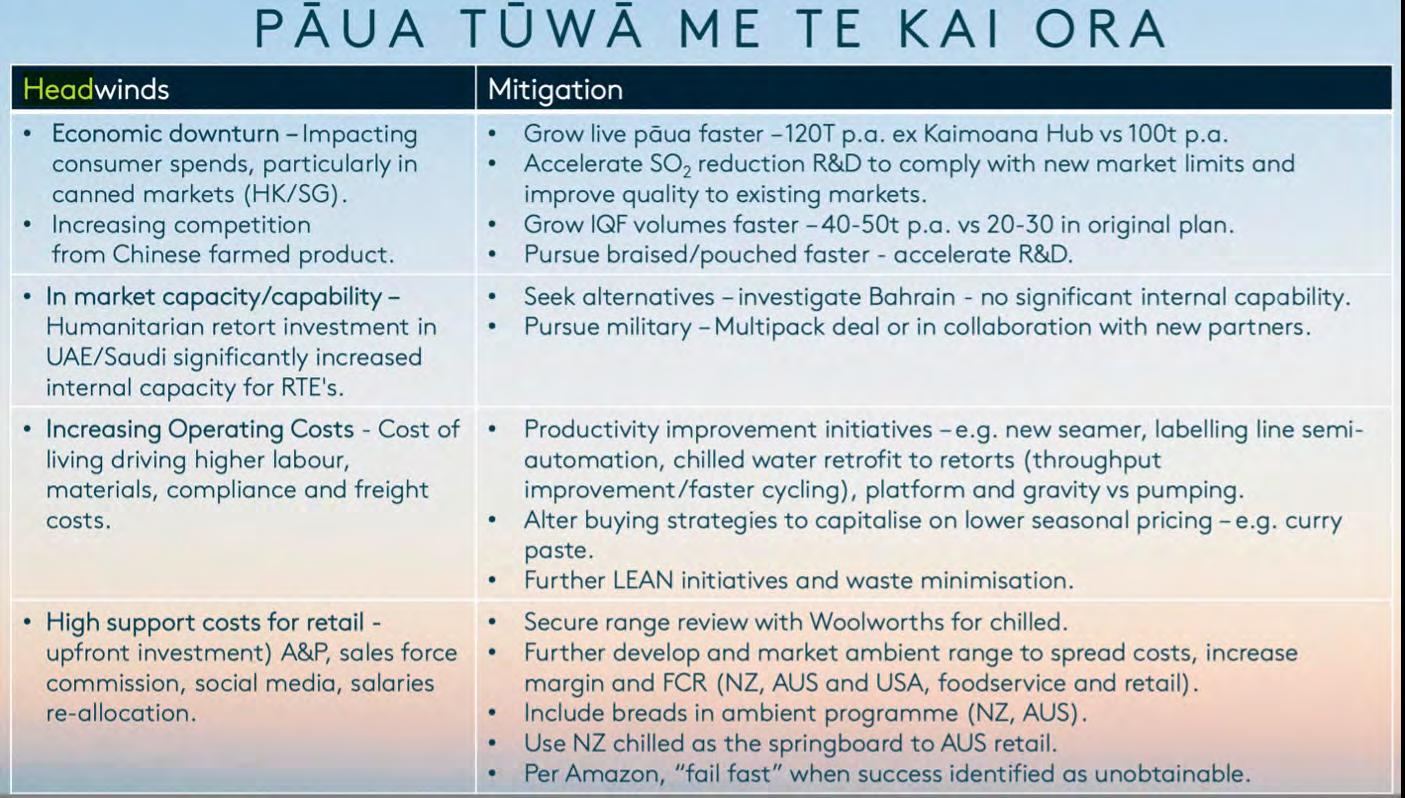

7. Through the systematic development of an organisational culture that reflects the values of its iwi shareholders, and the substantive partnerships cultivated further over our audit period, Aotearoa Fisheries Limited has demonstrated its commitment to work co-operatively with iwi on commercial matters. Aotearoa Fisheries Limited’s commercial performance has been assessed against the statutory measures by KPMG. Our impression is that the company has performed as well and as could be expected given the economic, geopolitical and market challenges or ‘headwinds’, including COVID lockdowns, in the years between 2020 and 2024.

8. A final overall observation is that the general and specific statutory requirements on the entities should not be considered to be passive. They are active. We think there is a stretch opportunity for the entities as the collective of Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana to be more alert, and exercise a higher level of capability and sophistication, given the highly dynamic operating environment domestically and internationally. As noted above and required in particular under s 108(e) of the Māori Fisheries Act, the ‘effectiveness’ in terms of improving iwi and Māori outcomes, of the policies and strategies aiming to achieve the objectives and of the performance of the duties and functions of each board and its directors was the most challenging to assess. If anything, it is the most important dimension of any audit of this sort.

9. In closing this executive summary, we considered it appropriate to highlight some final reflections that we have garnered in undertaking this process.

10. The success of any major movement, organisation or business depends on the quality of available leadership. It is the leadership that formulates the strategy for success. Leaders must be cognisant and responsive to the challenges, but also the opportunities.

11. Among other spheres of influence, the challenges and opportunities for Māori Fisheries include economic, environmental, political, legal and regulatory, technological, cultural, commercial and geopolitical.

12. It is clear to us that the leadership around the development and implementation of Māori Fisheries settlement has emerged, grown, consolidated and changed. That leadership has been at all levels from those well-known iwi leaders involved with shaping and bedding the settlement in, such as Graham Latimer, Bob Mahuta, Matiu Rata, Tipene O’Regan, Archie Taiaroa, and Apirana Mahuika, to those who sat on the boards of the Māori commercial fishing companies and set the initial course for the management of the assets.

13. The strategies for success at all levels have changed markedly over the past three decades as the entities have matured across the intervening period.

14. Our observation is that the leadership of the entities of Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana across the years, including our four-year audit period, has relied on a relatively small pool of capable people who are very busy applying their skills and experience across a wide range of issues and endeavours focussed on protecting, realising and optimising the rights and interests of iwi and Māori. To us, the identification, promotion or selection and socialisation of new leaders across the Kāhui has tended to be more organic rather than a deliberate developmental process.

15. We consider that there is an opportunity for the Kāhui entities as a collective to take a more deliberate approach through developing a leadership and succession strategy. It would be

a living, adaptive strategy. It would not necessarily identify individuals per se but formulate personae for the types of leaders that would be ideal or sought-after for each part and level of the Kāhui businesses.

16. Given the purpose and functions and stated objectives of Te Putea Whakatupu/Tapuwae Roa, that entity could be well placed to lead the development and coordination of such an initial leadership and succession strategy. Over time, potential leaders might be identified and supported for roles in Māori fisheries or related areas.

17. The Kāhui entities have a shared purpose to advance the interests of iwi and Māori in the development of fisheries, fishing and fisheries-related activities. The strategies and objectives of each entity should identify a range of results and outcomes relevant to the purpose, function and duties of each entity and measures for success against those outcomes. With a shared purpose, it is inevitable that there are shared outcomes, but the specific entities might contribute in differing and distinctive ways as befits their respective statutory and other legal obligations.

18. In this context, it makes sense for the four entities to work more closely to coordinate common functions, objectives and services (such as advocacy) to their iwi and Māori stakeholders, as is our recommendation. We would also recommend, however, that the entities crystalise and maintain a healthy level of independence and ‘creative tension’. By creative tension we are meaning, somewhat aspirationally, that diverse ways of seeing and thinking are brought to bear and that there is an openness to strategic horizons within the legal-regulatory operating environment.

19. We make this recommendation on the basis that for each entity there is a gap between the results and outcomes they seek to achieve, and the current status of outcomes for iwi and Māori.

20. Creative tension straddles the line between uncertainty and direction, and some level of creative tension between organisations creates an impetus to resolve that uncertainty. In turn, this will generate energy and create opportunities to bounce around new ideas and drive innovation between and across the entities.

21. Our recommendations are set out below:

21.1. First, with the enactment of the Māori Fisheries Amendment Act 2024 and in view of the iwi feedback regarding the four-year period from 2020, Te Ohu Kai Moana should be seeking to be a professionalised and highly proficient policy-operational hub regarding the fisheries settlement and relevant regulatory landscape(s). The rationale would be to support a strategic approach to protecting and enhancing the interests of iwi and Māori generally in fisheries, fishing and fisheries-related activities. Such a development should assist strategic approaches to protecting and enhancing the value of the assets onshore and offshore and could shape approaches to advocacy (including intervention logic). This capability set is emergent or incipient at Te Ohu Kai Moana, but it is something that could be progressed, fostered and consolidated, especially with a Kāhui perspective woven through it.

21.2. Second, and related to the foregoing point, we suggest that Te Ohu Kai Moana could seek to stress-test the legal-policy interpretative understandings of the fisheries settlement in 1992 that have emerged in the past two decades. These questions remain relevant to protecting and enhancing iwi-Māori rights in or to fisheries and to thinking actively about the regulatory systems that impact these rights onshore and offshore.

21.3. Third, we would recommend that the ‘Kāhui sensibility’ be developed and consolidated further. We note that there are areas, such as educational and research activity, where efforts might have been sharpened in their focus had an aligned or coordinated stance been kept in view. In circumstances of scarce resourcing, whether in terms of finance or personnel (or both), there is a risk of incomplete delivery of these initiatives or unhelpful and potentially

confusing duplication if entities within the Kāhui are pursuing comparable activities in the absence of coordinated discussions around complementarity and alignment.4

21.4. Fourth, the last four-year period reveals a measure of uncertainty on the part of iwi as to what the group of entities within the purview of Te Ohu Kai Moana does. Here, we note the feedback received from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu on the question of iwi interaction with Te Ohu Kai Moana. While the iwi engagement survey material is relatively spartan and is not a substitute for on-the-ground engagement with iwi, it would be useful to ensure that these iwi surveys are continued on a regular basis.

Te Wai Māori

21.5. For each of Te Wai Māori’s strategic outcomes and work programme objectives, we recommend that Te Wai Māori develop clear measures for performance and success (‘effectiveness’ and ‘progress’ as per s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act).

21.6. We also recommend the development of some specific objectives and actions to clarify the status of introduced freshwater species in relation to customary fishing and taonga species to provide better protection for taonga species and increased potential for commercial opportunities for iwi Māori in freshwater fisheries

21.7. We suggest that Te Wai Māori could consider positioning itself as a steward of the best knowledge and information on taonga species and their habitat. Te Wai Māori could do this by calling on existing partnerships and/or establishing new partnerships to commission the development of a data platform that becomes a central repository for this data and evidence to support the Trust’s strategic and business priorities.

21.8. We suggest Te Wai Māori check in with Te Ohu Kai Moana regularly to discuss how the two entities could work more closely together to engage iwi on submissions prepared and made by Te Wai Māori, as part of the regular engagement of Te Ohu Kai Moana with iwi on other matters.

21.9. We suggest Te Wai Māori consider commissioning some independent professional programme fund management analysis and advice on the optimal strategy for Te Wai Māori to structure, distribute and manage its funds against the stated purposes to the preferred target group.

21.10. We suggest Te Wai Māori periodically commission a stakeholder engagement survey, perhaps in collaboration with Te Ohu Kai Moana and the other Kāhui entities.

21.11. We suggest that Te Wai Māori develop contingency options to consider if it is required to identify and engage an alternative provider to manage the Ministry for the Environment Essential Freshwater (Tangata Whenua) Fund (or to source a comparable fund).

21.12. We concur with Te Pūtea Whakatupu’s self-assessment and recommend that it should:

21.12.1. Increase targeted investment to develop skills relevant to the fishing industry, particularly for education and training courses, as well as continuing to fund fisheriesrelated research.

21.12.2. Endeavour to increase its capability to gather robust data for analysis to measure outcomes, gain a more precise understanding of the impact of its initiatives on outcomes, and allow the Trust to better tailor its programmes to the needs of the Māori community.

21.13. We suggest Te Pūtea Whakatupu periodically commission a stakeholder engagement survey, perhaps in collaboration with Te Ohu Kai Moana and the other Kāhui entities.

21.14. We suggest Aotearoa Fisheries Limited periodically commission a stakeholder engagement survey, perhaps in collaboration with Te Ohu Kai Moana and the other Kāhui entities.

4. In saying this, we are conscious that, for the purposes of this four-year audit, the Kāhui comprises the four entities subject to that audit process, that is, Te Ohu Kai Moana, Aotearoa Fisheries Limited, Te Wai Māori and Te Pūtea Whakatupu (Tapuwae Roa). Nevertheless, beyond the statutory confines of the audit, the kāhui concept and context also extend to Sealord.

21.15. We recommend that Aotearoa Fisheries Limited endeavour to continue to improve its financial reporting so that it is clearer for iwi to see how each company is performing individually as well as part of the whole family of relevantly related Moana New Zealand companies.

22. The general scope of any four-year audit is set out in s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act 2004. Subsequent provisions then outline particular areas of focus for each of the four entities falling within the audit requirements of s 105 (audits) and s 106 (subsequent audits) of the Māori Fisheries Act: Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited, Aotearoa Fisheries Limited, Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited and Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited.

23. An auditor (Mark Hickford) was appointed under s 107 of that legislation with effect from Thursday, 27 June 2024. Due to the compressed timetable, and with permission from the relevant entity boards, Mark Hickford obtained the assistance of Anaru Mill, so this report does refer to ‘auditors’, in the plural, for ease of reference (even though, technically, one auditor was formally appointed at the outset.)

24. Terms of reference were issued to the appointed auditor on 27 June 2024. All four entities approved these terms of reference according to advice received from Te Ohu Kai Moana, and they are attached to this report as Appendix B in line with practice in the previous four-year audits. Sections 105–113 of the Māori Fisheries Act set out the audit requirements. This audit addresses the performance of the relevant entity rather than representing a financial audit.

This is the Third Four-year Audit since the Māori Fisheries Act was Enacted in 2004

25. This will represent the third four-year audit since the enactment of the Māori Fisheries Act two decades ago.

26. The most recent four-year audit conducted under s 106 of the Māori Fisheries Act was that of 2012.5 Twelve years have passed since then. During that time, an independent statutory review was also conducted, as required under s 114(2) of the Māori Fisheries Act. Only one other four-year audit has been completed in addition to the 2012 audit, and that was in 2008.

27. Given the recent enactment of the Māori Fisheries Amendment Act 2024, which heralds particular changes to the Māori fisheries legislative framework, it is fitting that this four-year audit for the period from 2020 until 2024 (inclusive) takes stock of the current situation vis-àvis Te Ohu Kai Moana and the other three entities subject to audit: Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (trading as Moana New Zealand), Te Wai Māori and Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trust (trading as Tapuwae Roa).

28. The Māori Fisheries Amendment Act 2024 received the Royal Assent on 26 July 2024.6 The policy aim underlying the Māori Fisheries Amendment Act 2024 was pithily expressed in the relevant Cabinet paper as follows: ‘to give Mandated Iwi Organisations (MIOs), Recognised Iwi Organisations (RIOs) and Representative Māori Organisations (RMOs) more autonomy over their fisheries settlement assets’.7 Such is one element of the official Crown viewpoint. Importantly, Te Ohu Kai Moana’s narrative, presented to iwi, is that the changes are intended to reduce cost, improve efficacy, move iwi towards greater rangatiratanga over their settlement assets and improve the entities’ ability to provide settlement asset benefits to all Māori.

29. As the auditors observed in the 2012 Four Year Audit Reports: Pursuant to Section 106 of the Māori Fisheries Act 2004, ‘We were concerned to know the objectives established by the four entities and to find out whether policies and strategies had achieved success, if any, over a [four-year] period.’

5. Don Hunn and Ken Mason, 2012 Four Year Audit Reports: Pursuant to Section 106 of the Māori Fisheries Act 2004.

6. Refer to s 2 of the Māori Fisheries Amendment Act 2024 for particularised commencement dates.

7. Cabinet paper entitled, ‘Progressing the Māori Fisheries Amendment Bill’, Cabinet Legislation Committee, at paragraph 3: Progressing the Māori Fisheries Amendment Bill – Cabinet paper (mpi.govt.nz) (last accessed 25 September 2024). Also refer to Cabinet Legislation Committee, Progressing the Māori Fisheries Amendment Bill’, Minute of Decision (LEG-24-MIN-0042 refers).

30. The essence of that comment remains apt. We do not depart from it.

31. Nonetheless, we do consider that in assessing the criteria listed under s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act it is vital to consider how the objectives are effectively tied into performance of the duties and functions of the relevant entity, as contemplated under s 108(b), (d) and (e) of the statute. At this point, we set out s 108 in full:

‘An audit conducted under section 105 or section 106 must consider and report, in relation to the entity being audited, on—

(a) the objectives established by the board of directors of the entity; and

(b) the extent to which those objectives are consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions of the entity under this Act or any other enactment; and

(c) the progress made by the board of directors towards achieving the objectives; and

(d) the policies and strategies established by the board of directors to achieve the objectives and perform the duties and functions of the board and its directors ; and

(e) the effectiveness of the policies and strategies referred to in paragraph (d) ; and (f) the quality and timeliness of the reporting documents prepared to meet the reporting obligations under this Act or another enactment.’8

32. While this sort of appraisal was clearly undertaken for the 2008 and 2012 four-year audits, it behoves us to give consideration to the strategic horizon for Te Ohu Kai Moana as informed by the relevant statutory functions and duties. In its turn, such a process entails reference to the possibilities of strategic positioning (rather than corporate inputs and outputs) not merely in the past four years but with an outlook to the future. To that end, our concluding recommendations will certainly raise themes that relate to these inter-temporal (across time) features with a strategic orientation in view of the legislative background, which sets out the purpose, duties and functions for Te Ohu Kai Moana.

33. The audit commenced in the first week of July 2024 and the audit report writing process was due to be completed by Friday, 11 October 2024. The timetable has proven to be rather tight overall.

34. Iwi engagement was invited through the offices of Te Ohu Kai Moana by way of a communiqué sent out on 9 July 2024.9 A further invitation to iwi to submit written feedback was issued on 30 September 2024.10

35. A submission dated 14 August 2024 was received from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. In the period of July and August 2024, hui were held with mandated iwi organisation, or MIO, representatives from Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Toa and Ngāti Porou. These discussions and contributions proved to be invaluable to the audit process. They permitted us to understand areas of concern regarding the iwi perspectives on if and how the objectives and strategies of Te Ohu Kai Moana were being delivered on.

36. As with the two preceding audits of 2008 and 2012, Te Ohu Kai Moana produced a helpful self-assessment, received in final form on Tuesday, 17 September 2024, which is annexed to this document as an appendix (Appendix E).

37. For convenience, we note that Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (trading as Moana New Zealand) supplied its board-approved self-assessment report on Thursday, 29 August 2024. A draft self-assessment report was received from Te Wai Māori Trust Limited on 16 August 2024. Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trust (trading as Tapuwae Roa) forwarded its self-assessment on 4 September 2024.

8. Emphasis added.

9. It is accessible in the public domain: refer to Invitation for iwi to comment on the four year audit for Te Ohu Kai Moana Group – Te Ohu Kaimoana (last accessed 26 September 2024).

10. Extension – iwi feedback on four-year audit for Te Ohu Kai Moana Group – Te Ohu Kaimoana

11. None were undertaken in 2022 or 2023.

38. For the audit process relating to Te Ohu Kai Moana, we met with the chief executive, and key members of the senior executive team on several occasions. A workshop was convened on 23 August 2024 where a draft self-assessment report prepared by Te Ohu Kai Moana was discussed and a range of questions were posed from the auditors’ perspectives. This process enabled Te Ohu Kai Moana to respond to various queries concerning the achievements and steps pursued across the four-year period from 2020. Specific papers were composed at points to respond to the external auditor requests.

39. The auditors met with the Chair and Deputy Chair of the Board of Te Ohu Kai Moana in late August 2024. Their feedback was garnered and has been factored into this report.

40. We have also reviewed an array of documentation that Te Ohu Kai Moana has provided to assist the audit process. Illustrations include annual plans, strategic documents (such as Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26), iwi engagement survey materials from 2020 and 202111 and other governance-related documentation (including board agendas).

41. Strictly beyond the scope of this four-year audit is the significant work programme that Te Ohu Kai Moana bears under the Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004. Clearly, we do not address that aspect of the responsibilities of Te Ohu Kai Moana, but feel compelled to note it as the self-assessment report of 17 September 2024 stated:

Te Ohu Kaimoana also has a range of statutory functions under the Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004, which while strictly speaking is outside of the scope of this audit, does make up a material proportion of the work that Te Ohu Kaimoana undertakes with and on behalf of Iwi, and contributes to our work advancing the interests of Iwi in this area.12

42. As ought to be well appreciated though, this legislative regime is not unrelated to the fisheries settlement. In 2004 it was seen as dealing with the ‘unsettled’ aspect of the allocation of space for aquaculture purposes (the spatial element) on the understanding that the fisheries dimension (including fishing activities and rights) had already been settled in 1992. The fisheries deed of settlement dated 23 September 1992, was given statutory expression in part through the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 and the Māori Fisheries Act 2004, which received the Royal Assent on 25 September 2004. This last piece of legislation was enacted three months before the Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004 (assented on 21 December 2004).

Summary of the Key Themes of the Assessment of Te Ohu Kai Moana

43. In summary and on balance, we conclude that Te Ohu Kai Moana has met the requirements of s 108 and made positive but incremental impacts on its stated objectives, consistent with the audit areas set out in both s 108 and s 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act. Our assessment has addressed the four-year period of 2020 until 2024 (inclusive) compared with previous periods.

44. Te Ohu Kai Moana carefully identifies those areas under its duties, functions and objectives where progress has been haphazard or episodically incremental, as with its advocacy in advancing the interests of iwi in the development of fisheries fishing, and fisheries-related activities (extracted as a ‘consolidated objective’ in its self-assessment report from the introductory words of s 32 of the Māori Fisheries Act (‘Purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana’)). In saying this, it notes that measuring achievements in such a space of activity is challenging within a twelve-month period, let alone across four years or in any longer-term assessment beyond 2024.

45. If we examine the specific performance of Te Ohu Kai Moana under s 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act, we are satisfied that the two aspects of that provision are being met. Section 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act provides:

In the case of an audit of Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited, the audit must consider and report on—

(a) the progress that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards allocating and transferring settlement assets; and

(b) the contribution that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards assisting iwi to meet the requirements for recognition as mandated iwi organisations.’

46. The self-assessment received from Te Ohu Kai Moana says that during the past four years substantive progress continues to be made. Thus, in 2024, ‘there are a total of 58 Iwi organisations after Tapuika withdrew from the Te Arawa Joint Mandated Iwi Organisation’. The self-assessment then states that, ‘Of those, 56 are Mandated Iwi Organisations’, and ‘Te Ohu Kaimoana has continued to support the two remaining Recognised Iwi Organisations to achieve Mandated status’.

47. In our initial findings we identified various themes that we have discerned as we have considered the four entities, but these are also pointedly relevant to Te Ohu Kai Moana, and we list them below:

47.1. The historical context and shifts in the strategic goals and priorities for the Māori Fisheries Settlement and iwi-Māori interests over time.

47.2. Balancing commercial and non-commercial fisheries/Economic development and Taiao/holistic perspectives.

47.3. Ensuring a systems lens relevant to the Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana group as a whole so that complementarities in policy and operations can be enhanced where appropriate and in compliance with legal requirements. In this context, the alignment and/or coordination of strategy, planning, reporting, investment and business activities of the entities (single overarching plans and reports, corporate services such as communications, legal, engaging with iwi in a non-duplicative way) and some services and outputs, such as research and scholarships, could be helpfully considered.

47.4. Advocacy in policy and legal issues of relevance to Te Ohu Kai Moana and the other three entities subject to the four-year audit process. The drivers and approach of each entity and the extent to which they might coordinate any advocacy on behalf of iwi-Māori interests requires further consideration. For instance, Te Ohu Kai Moana and Te Wai Māori could (we suggest) collaborate and/or align much more effectively on major public policy questions such as, by way of example: fisheries and environmental matters, fisheries and oceans training and education, responses to sustainability rounds administered by the Ministry for Primary Industries, participation in international processes regarding New Zealand’s interest in high-seas fisheries, and engagement with Ministry for the Environment reform of the Resource Management Act 1991.

An Intentional and Deliberative Kāhui Sensibility is in Evidence

48. There is a kāhui or group context to Te Ohu Kai Moana, which must be borne in mind. Under s 5 of the Māori Fisheries Act, Te Ohu Kai Moana Group is a defined term as follows: Te Ohu Kai Moana Group means Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited and every subsidiary, trust, or other entity over which it has effective control, including Aotearoa Fisheries Limited and its subcompanies, because in relation to that subsidiary, trust, or other entity, Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited—

(a) controls, directly or indirectly, 50% or more of the votes; or (b) appoints 50% or more of the directors, trustees, or office holders, as the case may be … .

49. Thus, this audit report concerning each of the four entities specified in the Māori Fisheries Act is mindful of the degree to which they operate as a collective (kāhui) while being mindful of their distinct legal obligations as discrete or individual entities. The Kāhui, spoken of and written as a collective noun for this audit, comprises four principal entities, namely Te Ohu Kai Moana, Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (trading as Moana New Zealand), Te Wai Māori and Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trust (trading as Tapuwae Roa). As noted previously, however, the concept of kāhui extends further to Sealord. Furthermore, one senior source in Te Ohu Kai Moana though that it could even be regarded at its broadest extent as including iwi-Māori (all those who are beneficiaries of the settlement).

50. In discussing our initial findings with board and management of the four entities it was acknowledged that a joined-up Kāhui story and perspective could be better presented to iwi-Māori, as an emerging theme during the audit process was that various iwi participants

were unclear about what each entity did and how they might coordinate or align their activities. One board member of Moana New Zealand noted in a nutshell that Te Ohu Kai Moana essentially focuses on advocacy and protecting the fisheries settlement; Moana New Zealand is the commercial face; Te Wai Māori could be seen as essentially addressing the freshwater dimension of fisheries; and Tapuwae Roa focuses on innovation to help support the flourishing of the fisheries industry. That was one perspective given to us. Nevertheless, the work to set out a clearer picture of collective alignment or joined-up strategic aims and behaviours was recognised.

51. When this report contemplates the operation of the four entities referred to and their possible alignment or collaboration, it is referring to that bespoke usage of Kāhui, which is deployed in Te Ohu Kai Moana documentation. It is understood that this terminology has been increasingly operationalised through meetings of senior governance and executive management representatives whereby matters of shared interest might be traversed. The self-assessment document of Te Ohu Kai Moana dated September 2024 observed: In 2020 Te Ohu Kaimoana convened the first meeting of the kāhui (group of entities) boards and senior executives since the passage of the Act in 2004. This included all of the directors from Te Ohu Kaimoana, Te Pūtea Whakatupu/Tapuwae Roa, Te Wai Māori, Sealord and Moana/ AFL [Aotearoa Fisheries Limited].

52. Yet that picture, while comprehensible and important, would be incomplete insofar as there are other subsidiaries for which Te Ohu Kai Moana has oversight responsibilities through its appointment of directors and staff. Hence, Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited is also a 100 percent shareholder in Portfolio Management Services Limited and Te Ohu Kaimoana Custodian Limited. The full list can be characterised as follows:

52.1. Te Ohu Kaimoana Custodian Limited is a wholly owned company responsible for holding fisheries settlement investment portfolio.

52.2. Te Ohu Kaimoana Portfolio Management Services Limited is a wholly owned company responsible for managing investments and returns on the investment portfolio for Te Ohu Kaimoana, Tapuwae Roa and Te Wai Māori.

52.3. Charisma Developments Limited is a wholly owned company responsible for holding certain fisheries settlement assets, including Redeemable Preference Shares in Aotearoa Fisheries Limited.

52.4. Te Ohu Kaimoana Development Fisheries Limited is a wholly owned company with a previous focus on development of fisheries although we are advised that this has not operated for some years now.

53. Nevertheless, one of the features apparent to the auditor(s) has been the consolidation of an intentional and deliberative Kāhui sensibility across the 2020–2024 period.

54. Opportunities for considering and aligning strategic priorities and deliverables has proven to be a pronounced consequence of these group-level engagements.

55. In the audit reports for each of the four entities, together with that addressing Te Ohu Kai Moana specifically, this theme is one that we return to in assessing the achievements, opportunities and risks for the entities constituting the Kāhui, as well as the phenomenon as a collective.

56. Likewise, our recommendations are presented in this broader context.

57. The stretch for the Kāhui is how this can be done in a more coordinated fashion practically. In doing so, we acknowledge that the individual legal obligations each entity has to observe must be respected. If the entities are operating as a Kāhui, then, duplicative behaviours ought to be avoided and where there is overlap some view ought to be taken as to how scarce resources of personnel and finance can be used most effectively.

58. Te Ohu Kai Moana has statutorily specified duties relative to certain entities within the Kāhui. For instance, under s 34(p) of the Māori Fisheries Act it must ‘consider and, if satisfied, approve the annual plans of Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited and Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited’.13 In addition, it appoints the directors of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited (s 34(m) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

59. Under s 111 of the Māori Fisheries Act, any four-year audit must specifically consider and report on the following dimensions of the contribution that Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited and Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited are to make:

(1) In the case of Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited, an audit must consider and report on the contribution that Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trustee Limited has made towards promoting education, training, and research in relation to Maori involvement in fisheries, fishing, and fisheries-related activities.

(2) In the case of Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited, an audit must consider and report on the contribution that Te Wai Māori Trustee Limited has made in advancing the interests of Maori in freshwater fisheries.14

60. Section 110 of the Māori Fisheries Act sets out particular areas that a four-year audit must consider and report on:

(1) In the case of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited, an audit must consider and report on— (a) the performance of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited in meeting its constitutional requirement to work co-operatively with iwi on commercial matters; and

(b) the commercial performance of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited in comparison with other participants in the fishing industry, including its net profit after tax as determined in accordance with generally accepted accounting practice, and changes in the value of the company.

(2) In this section a reference to Aotearoa Fisheries Limited includes its subcompanies.

61. As part of its self-assessment framework, Te Ohu Kai Moana set out a consolidated portrait of its duties and functions under the Māori Fisheries Act, which we repeat in the subparagraphs below:

61.1. Plan and report on achievements of duties and functions.

61.2. Advance the interests of iwi in the development of fisheries, fishing and fisheries-related activities. This consolidated objective aligns with the statutory purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana under s 32 of the Māori Fisheries Act and one of the possible functions of Te Ohu Kai Moana set out in s 35(1)(b) of that legislation, for example.

61.3. Assist the Crown in discharging its obligations under the deed of settlement of 23 September 1992.

61.4. Progress towards allocating and transferring settlement assets (and rights).

61.5. Legislative duties related to the appointment of directors to group entities, and role as corporate trustee.

62. These will be returned to when we provide our recommendations, but we consider it important to ensure that the language with which Te Ohu Kai Moana has characterised its own legislatively informed strategic and operating environment is outlined upfront.

63. Furthermore, we received certain iwi feedback that presented a clear perspective and aspiration for the purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana and Aotearoa Fisheries Limited. It considered that the two entities needed to be the centres of excellence for Māori fisheries policy (in the context of the 23 September 1992 settlement) and commercial fishing respectively. This source suggested that both had work to pursue in order to become these centres of excellence.

Te Ohu Kai Moana’s purpose, in the context of the fishery settlement, is to provide policy and other sorts of central services that iwi want and that iwi are not the best at providing individually, or for which there are diseconomies of scale, if they all try to do it individually.

The same thing is true of Aotearoa Fisheries Limited. Aotearoa Fisheries Limited’s purpose in the fishery settlement is to provide commercial solutions that iwi can’t efficiently do individually themselves.

In both cases, Te Ohu Kai Moana and Aotearoa Fisheries Limited have to be excellent at those respective roles. Otherwise, there is no point to it. If iwi collectivise behind something which is inefficient and ineffective, that’s a disaster for everyone, rather [than] a benefit for everybody. What are the problems and solutions that need to be solved for iwi to really get the maximum benefits out of the settlement? And these two entities - policy and commercial - are supposed to be designed to provide the solutions. They’re not just beautiful things that have a right to exist because of legislation. They’re there for a purpose.

64. The feedback warned against any complacency on the part of these entities within the Kāhui.

65. ‘Te Ohu Kai Moana’ is defined in s 5(1) of the Māori Fisheries Act as the Trust established pursuant to a trust deed and referred to in s 31 of that statute. Te Ohu Kai Moana must have only one trustee in accordance with s 33(1) of the Māori Fisheries Act. That trustee is stipulated to be ‘a company formed under the Companies Act 1993 with the name Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited’, as per s 33(2) of the Māori Fisheries Act.

66. The general scope of the audit is set out in s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act, and the coverage is mandatory: the audit ‘must consider and report, in relation to the entity being audited, on’:

66.1. the objectives established by the board of directors of the entity (s 108(a) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

66.2. the extent to which those objectives are consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions of the entity under the Māori Fisheries Act or any other enactment (s 108(b) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

66.3. the progress made by the board of directors towards achieving the objectives (s 108(c) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

66.4. the policies and strategies established by the board of directors to achieve the objectives and perform the duties and functions of the board and its directors (s 108(d) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

66.5. the effectiveness of the policies and strategies referred to immediately above (that is, under s 108(d) of the Māori Fisheries Act) (s 108(e) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

66.6. the quality and timeliness of the reporting documents prepared to meet the reporting obligations under the Māori Fisheries Act or another enactment (refer to s 108(f) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

67. The foregoing elements appearing in s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act are conjunctive.

We have to look at all the elements of s 108 in our four-year audit …

68. We have to look at all of them and how Te Ohu Kai Moana is meeting the relevant general requirements for the four-year audit.

… and the specific elements that we are required to look at for Te Ohu Kai Moana under s 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act

69. Regarding Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited specifically, s 109 of the Māori Fisheries Act provides that the audit ‘must consider and report on’:

69.1. the progress that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards allocating and transferring settlement assets (s 109(a) of the Māori Fisheries Act);

69.2. the contribution that Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited has made towards assisting iwi to meet the requirements for recognition as mandated iwi organisations (s 109(b) of the Māori Fisheries Act).

We have to assess the ‘objectives’ of Te Ohu Kai Moana and the ‘extent to which those objectives are consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions’ of Te Ohu Kai Moana …

70. The objectives referred to in s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act that are to be audited require an assessment of the ‘extent to which those objectives are consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions’ of Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited.

71. Those duties and functions are set out in s 34 and s 35 of the Māori Fisheries Act respectively.

72. A key hinge for these duties and functions, however, is that the duties listed in s 34 are inclusive rather than exhaustive and the chapeau or introductory text to s 34 expressly states that, ‘Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited must administer the settlement assets in accordance with the purposes of this Act and the purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana […]’.15 The ‘purposes’ of the Māori Fisheries Act are contained in s 3 and cannot be lost sight of. Section 3(1) of the Māori Fisheries Act provides that:

‘The purposes of this Act are to—

(a) implement the agreements made in the Deed of Settlement dated 23 September 1992; and (b) provide for the development of the collective and individual interests of iwi in fisheries, fishing, and fisheries-related activities in a manner that is ultimately for the benefit of all Māori.’16

73. Section 3(2) of the Māori Fisheries Act then states that, ‘To achieve the purposes of this Act, provision is made to establish a framework for the allocation and management of settlement assets through’:

73.1. ‘the allocation and transfer of specified settlement assets to iwi as provided for by or under this Act’ (s 3(2)(a)); and

73.2. ‘the central management of the remainder of those settlement assets’ (s 3(2)(b)).

74. In addition, the ‘purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana’ itself (expressed in the singular) is displayed in s 32. That provision is expressed as follows and bears quoting in full:

‘The purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana is to advance the interests of iwi individually and collectively, primarily in the development of fisheries, fishing, and fisheries-related activities, in order to — (a) ultimately benefit the members of iwi and Māori generally; and (b) further the agreements made in the Deed of Settlement; and (c) assist the Crown to discharge its obligations under the Deed of Settlement and the Treaty of Waitangi; and (d) contribute to the achievement of an enduring settlement of the claims and grievances referred to in the Deed of Settlement.

75. Again, these dimensions of the ‘purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana’ are expressed conjunctively, requiring attention to each outcome. That is, all must be kept in view. There is no ‘either/ or’ choice here. Evidently, the deed of settlement executed on 23 September 1992 between the Crown and Māori17 remains the keystone in this enunciation of the ‘purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana’. The foregoing description of the ‘purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana’ resonates with elements of the language of that deed. Section 5 of the deed of settlement was entitled ‘settlement agreements’ containing clause 5.1 (‘Permanent settlement of commercial fishing rights and interests’) and clause 5.2 (‘Non-commercial fishing rights and interests’).

76. This deed of settlement’s undeniable significance as foundational is contextualised and nuanced somewhat, however, in s 32 relative to Te Ohu Kai Moana in two senses:

76.1. first, the Crown is to be assisted in discharging its obligations under both the deed of settlement and the Treaty of Waitangi (s 32(c)); and,

76.2. second, Te Ohu Kai Moana is to ‘contribute to the achievement of an enduring settlement of the claims and grievances referred to in the Deed of Settlement’ (s 32(d)).

77. This statutorily expressed ‘purpose’, then, is an active, dynamic one rather than one that is static or necessarily completed at any given point in time.

78. By that, we mean that the ‘purpose’ is implicitly adaptive circumstantially, as factors exogenous or external to Aotearoa New Zealand (such as geopolitical adjustments or changes

15. Emphasis added.

16. Macrons have been inserted in this quoted passage. They were not in the original text.

17. Specifically, between the Crown and Sir Graham Latimer, the Honourable Matiu Rata, Richard Dargaville, Tipene O’Regan, Cletus Maanu Paul and Whatarangi Winiata, together with other persons who had negotiated with the Crown on behalf of iwi, the New Zealand Māori Council, the National Māori Congress and other representatives of iwi.

in markets and behaviours offshore) and various endogenous elements within the local jurisdiction, including shifting interpretative approaches to the iwi-Māori-Crown relationships across time, occur.18 Echoing s 3 of the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992,19 agreements made in the deed of settlement are to be furthered (s 32(b): ‘further the agreements made in the Deed of Settlement’). The meanings of those agreements might, nonetheless, require ongoing interpretation from a strategic perspective given how the courts have construed the ambit of the text in the deed of settlement itself compared to the subsequent legislation, the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act. 20

79. As is well appreciated, customary fishing rights and interests were characterised as ‘commercial’ or ‘non-commercial’ in that settlement. Clause 5.2 of the deed of settlement noted that ‘non-commercial fishing rights and interests’ would not be extinguished via the settlement and would ‘continue to be subject to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi and where appropriate give rise to Treaty obligations on the Crown’. In addition, ‘Such matters may also be the subject of requests by Maori to the Government of initiatives by Government in consultation with Maori to develop policies to help recognise use and management practices of Maori in the exercise of their traditional rights’. 21 Essentially, the Crown and Māori Treaty partners should work continuously to optimise the value of the settlement and related rights and interests of iwi and Māori.

80. Under s 10 of the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act, ‘claims by Māori in respect of non-commercial fishing for species or classes of fish, aquatic life, or seaweed that [were] subject to the Fisheries Act 1983’:

(a) shall, in accordance with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, continue to give rise to Treaty obligations on the Crown; and in pursuance thereto

(b) the Minister, acting in accordance with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, shall— i consult with tangata whenua about; and ii develop policies to help recognise— use and management practices of Māori in the exercise of non-commercial fishing rights; and

(c) the Minister shall recommend to the Governor-General in Council the making of regulations pursuant to section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1983 to recognise and provide for customary food gathering by Māori and the special relationship between tangata whenua and those places which are of customary food gathering importance (including tauranga ika and mahinga mataitai), to the extent that such food gathering is neither commercial in any way nor for pecuniary gain or trade; but

(d) the rights or interests of Māori in non-commercial fishing giving rise to such claims, whether such claims are founded on rights arising by or in common law (including customary law and aboriginal title), the Treaty of Waitangi, statute, or otherwise, shall henceforth have no legal effect, and accordingly—

(i) are not enforceable in civil proceedings; and

(ii) shall not provide a defence to any criminal, regulatory, or other proceeding,— except to the extent that such rights or interests are provided for in regulations made under section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1983.’

The Changing Legal Landscape Forms an Important Backdrop to the Operating Environment for Te Ohu Kai Moana and the Group

81. This background remains apposite as the legal architecture persists and the obligations continue although the Fisheries Act 1996 is now in operation. This legal landscape affords a range of possibilities for Te Ohu Kai Moana and the Kāhui as a whole to keep under active consideration, points to which we will come in our analysis and recommendations regarding

18. Appreciating, of course, that the boundaries between what might be construed as ‘exogenous’ or ‘endogenous’ are inexorably porous, with considerable intermeshing.

19. Section 3 of the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 states: ‘It is the intention of Parliament that the provisions of this Act shall be interpreted in a manner that best furthers the agreements expressed in the Deed of Settlement referred to in the Preamble.’

20. This observation is elaborated below in the discussion of the High Court decision in Te Arawa Māori Trust Board & Anor v Attorney-General, High Court, Auckland; 5 December 2000; CP448-CO99, Anderson and Paterson JJ.

the current state. The legal interpretative environment has adjusted since 2004 let alone 1992, and it is apt that Te Ohu Kai Moana, in complying with its statutory obligations and performing its functions, keeps a weather eye out for these shifts across time, whether those changes are subtle or less so.

82. In Appendix C, we set out further details on this legal interpretative environment focusing on two cases. These elements continue to influence interpretative understandings in official policy but can still be tested as part of the landscape that affects or shapes the coverage of the fisheries settlement. Revisiting or reconsidering this environment also offers possibilities for Te Kāhui o Te Ohu Kai Moana to think afresh about whether that legal landscape might offer further policy and strategic opportunities.

83. The observations raise architectural and system issues, that is, variable jurisdictions impacting ‘non-commercial Māori fishing rights and interests’ in the freshwater context, as well as spaces or areas elsewhere in the marine environment (such as the coastal marine area). This comment assists in demonstrating the complexities that Te Ohu Kai Moana must contend with as it navigates its board-approved objectives and policies.

84. Within this overall legal context, the functions of Te Ohu Kai Moana are expressed permissively rather than directively and prescriptively. As such, s 35 of the Māori Fisheries Act begins with the words, ‘As a means to further the purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana, Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited may […]’. 22 There is a measure of optionality, therefore, in how Te Ohu Kai Moana might prioritise its functional behaviours, with a view to achieving or furthering its purpose as outlined in s 32 of the Māori Fisheries Act. Section 35(1)(b), for example, says that Te Ohu Kai Moana ‘may’: in relation to fisheries, fishing, and fisheries-related activities, act to protect and enhance the interests of iwi and Māori in those activities.

85. This language within the legislation permits a measure of deliberate choice around what, how and where to prioritise activities in order to advance the statutory purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana located in s 32 of the Māori Fisheries Act.

86. Accordingly, this factor heightens the need for intervention logic and other methodologies to assist in guiding priority-setting and decision-making albeit with an appreciation that certain choices might be apposite at different times and in a range of changeable circumstances. The strategic goals and consolidated objectives of Te Ohu Kai Moana during the four-year audit period, October 2020–September 2024

87. Turning to the period from 2020 until 2024, the Board of Te Ohu Kai Moana initially set out objectives (identified as ‘strategic goals’) in the annual plan that applied from 1 October 2020 through to 30 September 2021 (inclusive). These were listed as:

87.1. ‘All Māori fisheries settlement entities work collectively to advance and improve Māori fisheries and achieve positive outcomes for Iwi and Aotearoa in a manner that is publicly understood.’

87.2. ‘Iwi have access to a strong pool of talented and skilled Māori fisheries commercial and noncommercial expertise.’

87.3. ‘Empowering Māori fisheries policy (commercial and non-commercial) is informed by tikanga Māori and practical ‘on the ground’ realities and experience of customary and commercial fishers. Our fisher’s commercial and non-commercial practices respect tikanga as well as the empowering policy and legal framework which underpin Māori fisheries rights.’

87.4. ‘The Māori world view guarantees of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the 1992 Fisheries Settlement are understood and respected by Government, the New Zealand public, and international audiences. A Māori worldview and Tiriti/Treaty rights are fully incorporated into New Zealand’s marine management policies.’

88. The self-assessment report of Te Ohu Kai Moana notes how the Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26 represents the latest strategic plan, which reflects, in part, what Te Ohu Kai Moana ‘heard from iwi on our haerenga around the motu in 2021’. 23 Approved in September 2021, the initial iteration of strategic pou numbered four and set out the board’s broad objectives: 24

22. Emphasis added.

23. Rangimarie Hunia, Chair, Te Ohu Kai Moana, ‘A New Strategy’, in Rima Tau Rautaki 2021-26: Five Year Strategy at 4.

24. Ibid at 6–7.

Pou Tuatahi By the end of 2026, we have made transformational changes to the legislative and policy system impacting Iwi fishing and our relationship with Tangaroa.

Pou Tuarua To ensure 100% of our programs assist in increasing the capability of Iwi to determine the management of their fisheries and marine interests.

Pou Tuatoru To invest in research and innovation that supports an Iwi perspective in fisheries management and their relationship with Tangaroa.

Pou Tuawhā To ensure 100% of our efforts in protecting the Deed of Settlement have resulted in positive and resilient outcomes for Iwi.

89. Changes subsequently occurred following discussions in May 2024 in the wake of five new board appointments on the part of Te Kāwai Taumata in November and December 2023. These adjustments saw the language introducing pou tuarua and pou tuawhā altering somewhat, such that the second pou now reads: ‘To ensure our programmes assist in increasing the capability of iwi to determine management of their fisheries and marine interests’. Similarly, the fourth pou is now cast in the following terms: ’To ensure our efforts in protecting the Deed of Settlement have resulted in positive and resilient outcomes for iwi’. In essence, then, the reference to 100 percent disappeared from the text, with the emphasis being placed on ensuring or working towards attaining a goal or objective.

90. Accompanying each of the strategic pou is a discrete comment or piece of elaborating text.

91. For Pou Tuatahi, the initial strategic pou, an aspiration for change ‘[b]y the end of 2026’ is explained, with an ambitious sense of direction and influence regarding policy: This Pou represents a commitment to change. That Te Ohu Kaimoana will further develop Te Hā o Tangaroa as the foundation for our policy advice and create a Māori narrative for our worldview in oceans. We will draw on mātauranga Māori and undertake policy mahi that serves this pou and our ability to share a Māori perspective that is uniquely our own – driven by our own agenda, rather than the Crown’s.

92. Turning to the second strategic pou, Pou Tuarua, which states, ‘To ensure our programmes assist in increasing the capability of iwi to determine management of their fisheries and marine interests’, the following comment is supplied in Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26: Pou Tuarua ensures that we are supporting iwi to build capability in delivering on their accountabilities and responsibilities for fisheries and wider marine interests while ensuring Tangaroa can provide for their people and future generations.

We will do that by both creating resources to share our policy knowledge with iwi and continue to advocate on behalf of iwi. Every programme we work on has a commitment to iwi and supporting their aspirations.

93. Pou Tuatoru, the third strategic goal or pou, relates to the aim ‘To invest in research and innovation that supports an iwi perspective in fisheries management and their relationship with Tangaroa’. The associated comment states: Research and innovation [is] an area we are required to invest [in] and create action but we have never done that outwardly nor worked on this with great purpose. This Pou will ensure that we are working on and in research. At the outset, this will be with partners until we are clear about what role Te Ohu Kaimoana could have in working for iwi in the research arena.

94. Set alongside Pou Tuawhā we see the following comment: The greatest part of our purpose is to protect the Deed of Settlement. This Pou helps us ensure our priorities are focused on outcomes that deliver positive results for iwi.

95. These four principal elements in Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26 resonate with a perspective that one Te Ohu Kai Moana board member provided to the audit in late August 2024, namely a view that situated Te Ohu Kai Moana within a broader historical frame. His points were as follows: Initially, the focus was on securing the fisheries assets through the Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Settlement negotiations processes leading up to the eventual execution of the deed of settlement on 23 September 1992.

From 1992 to 2003, the focus was on developing the methodology for allocating the fisheries assets to iwi.

From 2004 to around 2015, the focus shifted to the allocation process itself, with some iwi choosing not to participate.

The statutory review process in 2015 asked fundamental questions about the purpose and role of Te Ohu Kaimoana.

Under different CEOs and Chairs, the focus has evolved from growing the commercial asset to implementing the allocation model and, subsequently, to more recently emphasising rightsprotection and balancing commercial interests with environmental and cultural considerations.

The organisation has had to navigate changing societal attitudes towards commercial fishing and has increasingly repositioned itself as a policy think tank and advocate for Māori rights in the fisheries sector.

96. On balance, the final two paragraphs in the excerpt quoted above do appear to align with the general orientation of Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26. We consider the words cited present a useful narrative arc from the perspective of a board member of Te Ohu Kai Moana given the manner in which the different phases of focus are treated from the deed of settlement dated 23 September 1992 onwards.

97. The latest annual plan for Te Ohu Kai Moana set out the strategic priorities for 2023–2024. 25 In doing so, the annual plan is explicitly tied to the strategic pou or pillars identified above.

98. Advocacy on behalf of ‘iwi in their relationship with the moana’ is a key objective that is related to three strategic pou, for instance: Pou Tuatahi, Pou Tuatoru and Pou Tuawhā. Key performance indicators are then identified:

1 Te Ohu Kaimoana has led and supported opportunities for iwi in the moana, including related to fisheries and aquaculture.

2 Provide iwi with the information required to make their own decisions pertaining to legislative policy system changes impacting their relationship with the moana.

3 Litigation strategy and [rights-based] framework tested and developed.

4 Bi-monthly updates on legislative changes and showcase Te Ohu Kaimoana’s involvement in those processes.

5 Te Ohu Kaimoana assists iwi to meet their compliance obligations.

99. The self-assessment has expanded on these elements in certain ways. Key performance indicator number three, which is characterised as ‘Litigation strategy and [rights-based] framework tested and developed’, is one example of an intervention logic guiding strategic direction in specific ways. In discussions with Te Ohu Kai Moana representatives, we were able to hear views as to how this form of advocacy achieved outcomes relevant to the strategic priorities and objectives of Te Ohu Kai Moana.

100. All these goals or objectives seem prudent and make sense to us.

101. As part of the audit under s 108(b) of the Māori Fisheries Act, we must consider and report on (assess) ‘the extent to which those objectives are consistent with the effective implementation of the duties and functions of the entity under this Act or any other enactment’.

102. Section 108(e) places an emphasis on the ‘effectiveness of the policies and strategies’ referred to in the preceding paragraph of the statutory provision. We must consider and report on the ‘effectiveness of the policies and strategies’ that the boards of directors for each of the four entities has ‘established … to achieve the objectives and perform the duties and functions of the board and its directors’.

103. Those ‘duties and functions’ relate to the statutorily enumerated ones pertaining to the entity in question. In the case of Te Ohu Kai Moana that is s 34 and s 35 of the Māori Fisheries Act insofar as legal duties and functions are concerned.

Auditor(s) broadly satisfied with the performance of Te Ohu Kai Moana relative to s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act

104. At the outset, we wish to record that we are broadly satisfied with the performance of Te Ohu Kai Moana in accordance with the criteria set out in s 108 of the Māori Fisheries Act. … but there are strategic opportunities that might be grasped and considered …

105. Having said that, there are various insights that we have drawn from the 2020–2024 period that we have identified that ought to assist Te Ohu Kai Moana in positioning itself to consider strategic opportunities.

106. These findings and suggestions coincide with the tenor of certain feedback we have received from iwi engagement during the audit process, together with those comments given in sessions involving governance or senior management representatives from the other three entities.

107. Optionality or choice is intrinsic to the s 35 functions given the permissive nature of that provision relative to advancing the statutory purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana. Transactional behaviours that are not informed by strategic horizons will not assist. As such, strategic options remain relevant concerning the coverage of the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992, as we have raised in questions of each of the four entities throughout the audit process. These include, adjusting or calibrating approaches within a sufficiently flexible and capacious strategic outlook, adapting intervention logic in the context of a changing operating environment, managing scarce human and financial resources and operating in a legal landscape that affords interpretative and policy opportunities that might be of assistance to Te Ohu Kai Moana in progressing its purpose and duties under the Māori Fisheries Act.

108. We have heard from certain MIO representatives, predominantly via oral feedback. One written submission was conveyed to us via Te Ohu Kai Moana – that of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

109. In its formal letter of 14 August 2024, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu noted:

Te Rūnanga believes this to be good opportunity to reiterate our desire to work with Te Ohu and for there to be consistent, open, and transparent communication. Working collaboratively and with strong policy expertise on both sides would allow us to collectively hold the Government to account and ensure the fisheries and aquaculture settlements are upheld. It would also ensure that iwi interests are represented and upheld by Te Ohu, as per the terms of the settlements while providing iwi a point of influence in the government policy and decision making.

110. Relevantly for those priorities and themes addressing the advocacy role of Te Ohu Kai Moana in, say, Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26 (Pou Tuatahi and Pou Tuawhā, for example), Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu advises that:

Where matters have been specific to place with the Ngāi Tahu takiwā, Te Rūnanga has felt it more appropriate to advocate for change, participate in legal or other processes, and generally sought and achieved outcomes for Ngāi Tahu (which often benefit other iwi too) independently from Te Ohu.

This indicates that the role and value add of Te Ohu is not always clear for Te Rūnanga, aside from the four areas identified above. We recognise the role of Te Ohu and reliance of iwi on Te Ohu is likely to differ around the motu. This is fine. Te Rūnanga considers that Te Ohu needs to develop in maturity as an organisation to also recognise that.

111. Now, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu might not be adverting to a particular document, such as Rima Tau Rautaki 2021–26, but its comments are evidently mindful of the advocacy role that Te Ohu Kai Moana plays and questions of strategic opportunity.

Te Rūnanga considers that Te Ohu:

– Is in a position of potential influence and strength due to its ability to advocate for iwi on matters of shared concern or benefit and as the trustee has access to Government and Ministers that iwi might not have.

– Has the ability and role to create efficiencies for iwi by providing solid technical or legal advice on settlement matters which iwi could use as they see fit, or disregard if not of particular relevance.

– Should increase engagement with iwi to better understand the granularity of issues they face in areas that are significantly different from when the parameters or Te Ohu [were] originally agreed to by iwi.

– Must promote good process, including within its own processes and hui.

– Should be available on specific place based kaupapa that may impact on fisheries or aquaculture settlement to support iwi at place, if required and sought by iwi.

– Can sometimes be well placed to assist in facilitating discussion or hui on specific kaupapa when sought by iwi.

– Has the potential to be a central source of professional excellence in technical areas surrounding fisheries and aquaculture settlements.

– Must, at all times, be clear on whether it is delivering benefit and outcomes to iwi.

112. Leveraging off these preceding points, the ‘four areas’ in Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu submission where it was able to identify a persuasive rationale for the contributing role of Te Ohu Kai Moana during the four-year period were expressed in the following fashion:

Reflecting on the above, Te Rūnanga notes that in the past 4 years Te Ohu has demonstrated its ability to deliver on the above by:

– Carrying out its functional role in transferring settlement assets.

– Participating in aquaculture settlement negotiations as required including working on modelling.

– Providing introductory materials and held hui with kaimahi to assist in understanding of the Māori Fisheries Amendment Bill, including facilitating hui with all iwi.

– Carrying the weight of the 28N process for iwi. 26

113. These comments from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu are undeniably helpful. They are broadly consonant with what we have heard orally from other iwi participants in the audit process.

114. Insofar as its advocacy in policy and legal matters is concerned, the relevant intervention logic tends to focus on ensuring that no erosion of those rights addressed under the 23 September 1992 deed of settlement occurs. Protecting assets under the fisheries settlement is certainly one feature of the advocacy objective. In that sense, the stance could be construed as defensive. We see this approach in evidence with the recent proceedings in Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited v Attorney-General27 decided on 4 September 2024. In that case, Te Ohu Kai Moana has sought to protect settlement assets from the impact of unredeemed s 28N of the Fisheries Act 1983 shares if and when the Minister for Oceans and Fisheries decides to increase the total allowable commercial catch (TACC) in the Snapper 8 fishery (SNA8) under ss 13 and 20 of the Fisheries Act 1996.

115. From an opportunity-based viewpoint, we have explored some issues that are endogenous features of the regulatory landscape in New Zealand that might suggest ways for Te Ohu Kai Moana to consider the enhancement of iwi-Māori fishing rights and interests (commercial and non-commercial) through a strategically informed systems lens. Different logics or ways of seeing might be in play. Iwi might display a diverse range of views on incentivising the protection and relative enhancement of taonga species, with particular legal-policy avenues being explored, such as conferring legal personality on tuna. Other perspectives might wish to consider the place of introduced species and how iwi-Māori rights and interests in customary fisheries, whether commercial or non-commercial, might be afforded meaningful legal and policy impact. This could also encourage thought about governance regimes and revenue sharing arrangements. We do not wish to predetermine or to curate any options but simply raise these observations for further reflection.

116. We received instructive feedback from a board member of Te Wai Māori Trust Limited (24 September 2024) that the strategic orientation could look at ‘wealth creation in or at place’ with iwi engagement on the ground.

117. As noted in the introductory parts of this audit report, the final self-assessment report of Te Ohu Kai Moana outlined five consolidated core groups of legislative duties and functions: 117.1. Planning and reporting on achievements of duties and functions.

26. The ‘28N process’ refers to the ongoing proceedings in the High Court at Wellington, that have seen the issuing of one judgment in Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited v Attorney-General [2024] NZHC 2521. 27. [2024] NZHC 2521.

117.2. Advancing the interests of iwi in the development of fisheries, fishing and fisheries-related activities. This consolidated objective aligns with the statutory purpose of Te Ohu Kai Moana under s 32 of the Māori Fisheries Act and the one of the possible functions of Te Ohu Kai Moana set out in s 35(1)(b) of that legislation, for example.

117.3. Assisting the Crown in discharging its obligations under the deed of settlement of 23 September 1992.

117.4. Progressing towards allocating and transferring settlement assets (and rights).