Issue 17 | 2023 USD 10,00 | KES 1,000 | CAD 12 | ZAR 120

M oses M utabaruka Winnie M ills P aul k idero s ha MM er a gila g athoni k ang ’ ethe s te P hanie M atu n atasha n tagara M voi k igondu Editor in Chief Country Coordinator Photographer / Creative Consultant Video Production / Editor Contributor & Production Assistant Production Manager Contributing Writer Magazine Design & Layout

Cover art by Paul Kisuche @kisuche_

Cover art by Paul Kisuche @kisuche_

DEAR TAP FAM,

Warm greetings! I hope that the new year started out well for you and all your loved ones!

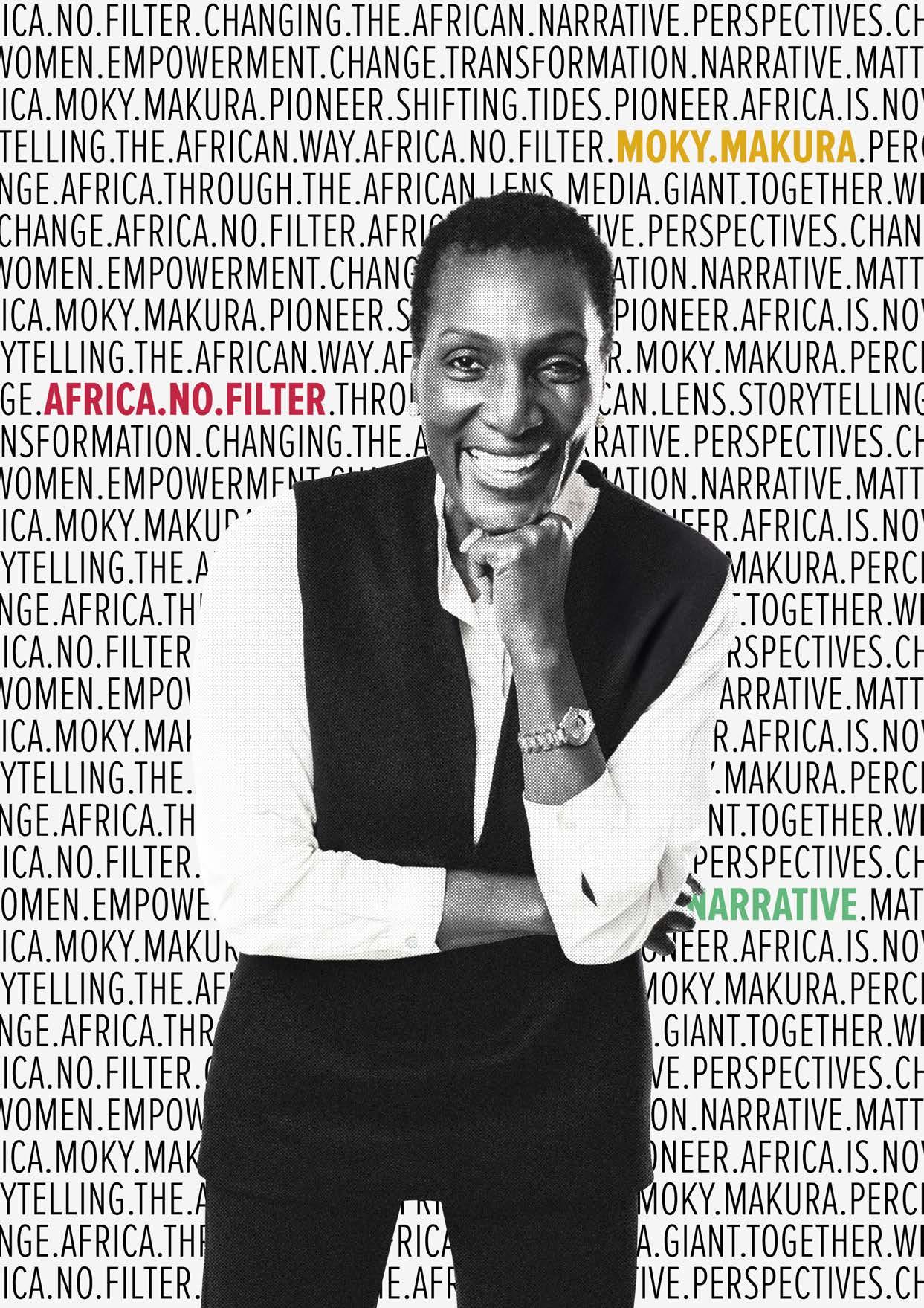

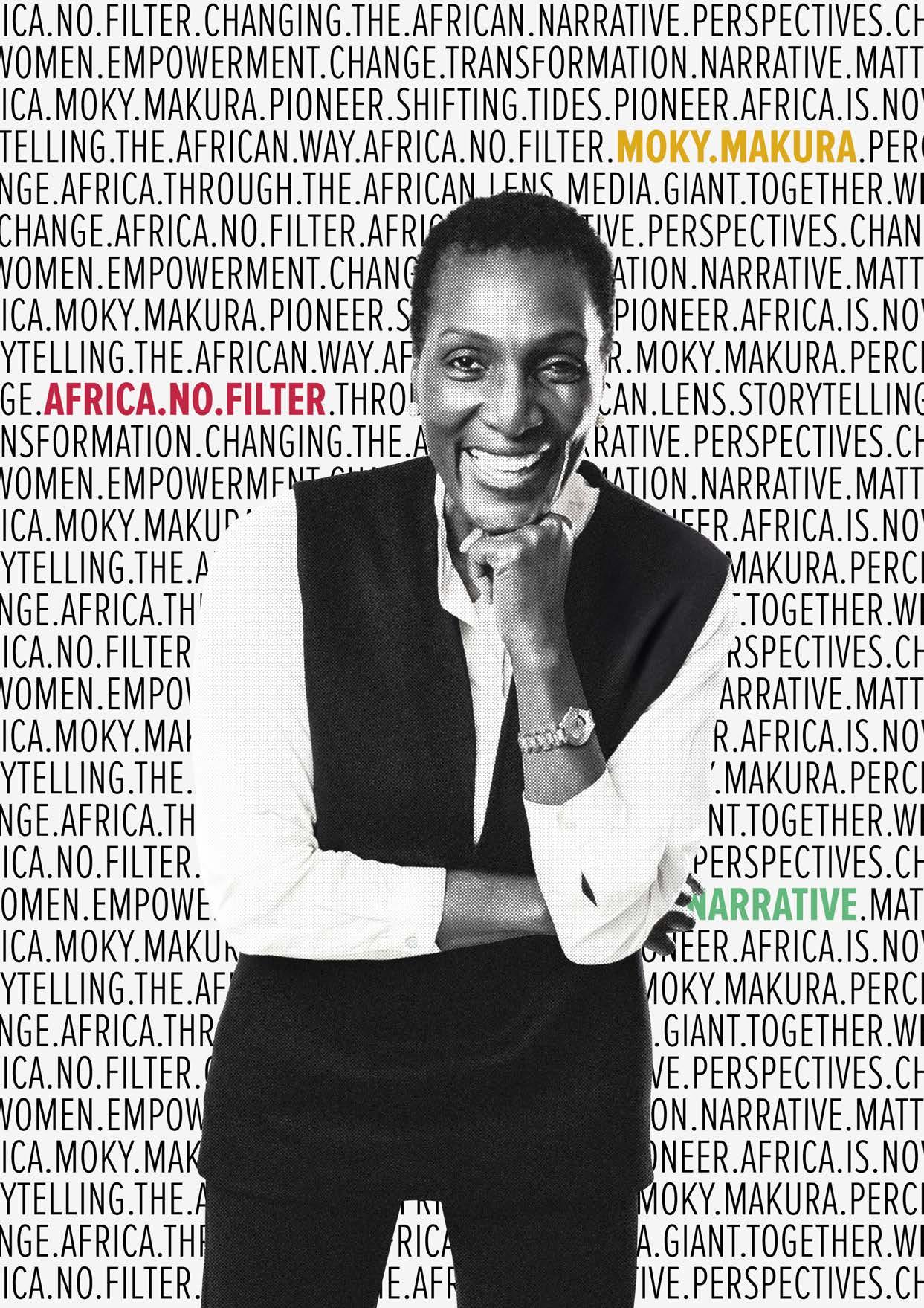

We are thrilled to be publishing the 17th issue of TAP Magazine in what we hope will be a milestone year for this magazine. As a publication founded out of a need to change how the world views and thinks about Africa, we’re honoured to have Moky Makura, the founding Executive Director of Africa No Filter on the cover of this special issue.

When Moky first saw the famous “Live Aid” concert, she was so annoyed with how Africa and Africans were portrayed that she knew she needed to do something about it. She was determined that poverty, pity and misery was not going to be the dominant narrative about Africa. Today, among other things, the organization she leads offers grants of over a million dollars a year to African storytellers who are just as passionate about shifting African narratives. You can find Moky’s feature interview on page 35.

On page seven, we meet Kim Makin, a brilliant Motswana multi-disciplinary artist who we had the pleasure of meeting on our recent trip to Gaborone, Botswana. In her latest work, “The

Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened” an audio and visual exhibition, Kim traces aspects of her family history and her own identity from the lenses of transnational identity while also examining the historical entanglements across Botswana and South Africa. Head over to page 07 and I guarantee you’ll learn a thing or two.

While still in Gaborone, what do you get when you bring together the sound of Oliver Mtukudzi with the rhythms and energy of Fela Kuti and you mix them with Botswana traditional sound, and you add a bit of hip-hop and modern R&B sound? Well, you get Jordan Moozy. The next singing superstar out of Africa that we’re putting our money on to eventually take the world by storm. Get to know Mr. Jordan Moozy on page 45.

On page 19, we’re sharing an inspiring story of Chernor Bah, a tenacious young leader and activist who left his safe and comfortable UN job in New York to co-found Purposeful. Purposeful is a feminist organization with an ambition to remake the world with and for girls that’s proudly headquartered in Sierra Leone, but with footprints in over 100 countries around the world. If you’re one of those people who don’t believe in the work of NGO’s, the story of Purposeful and the impacts it has will absolutely challenge you.

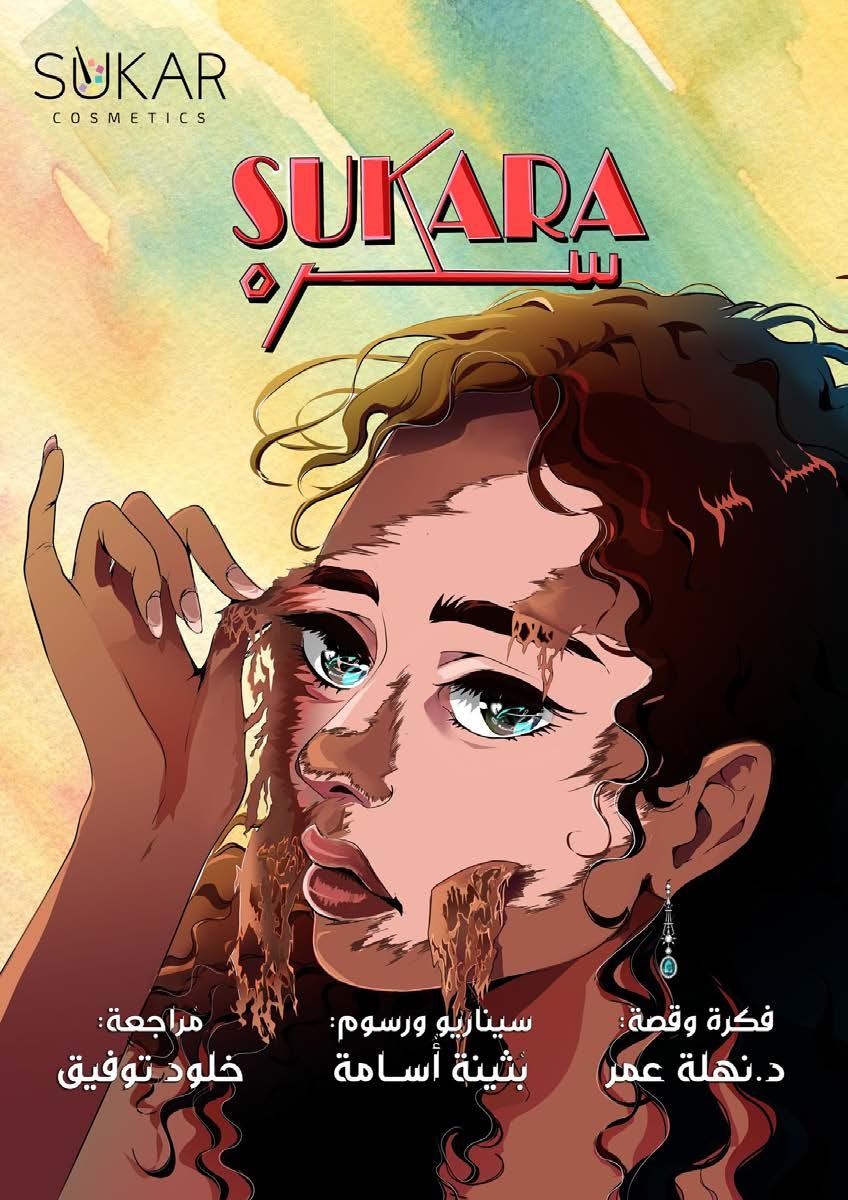

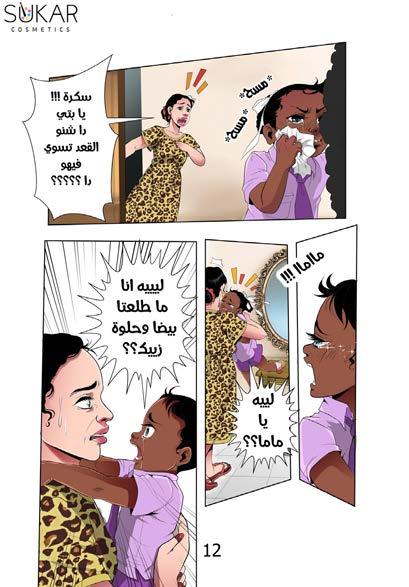

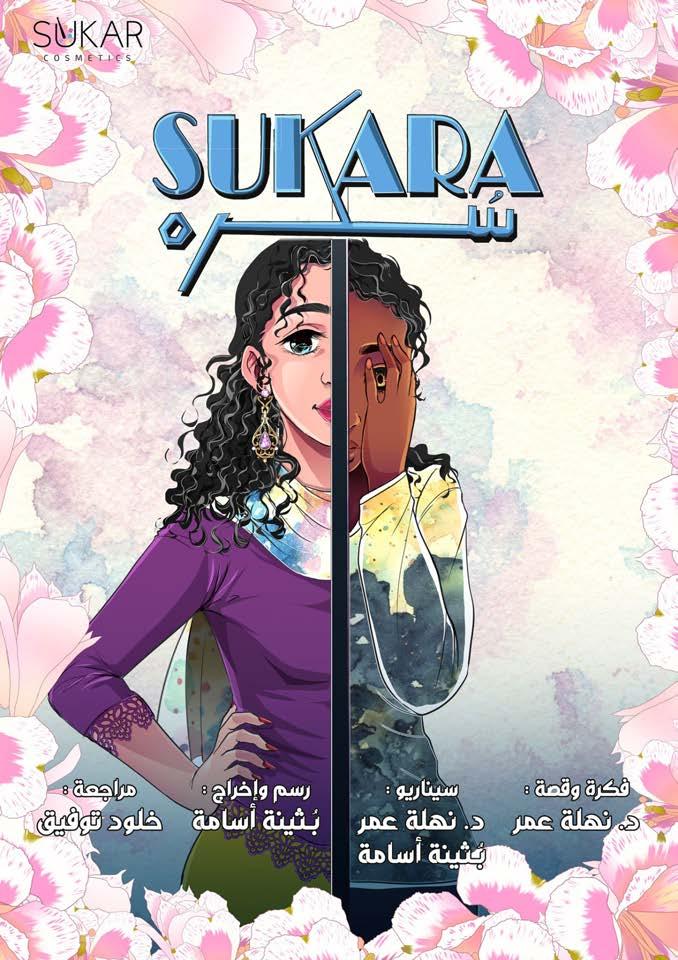

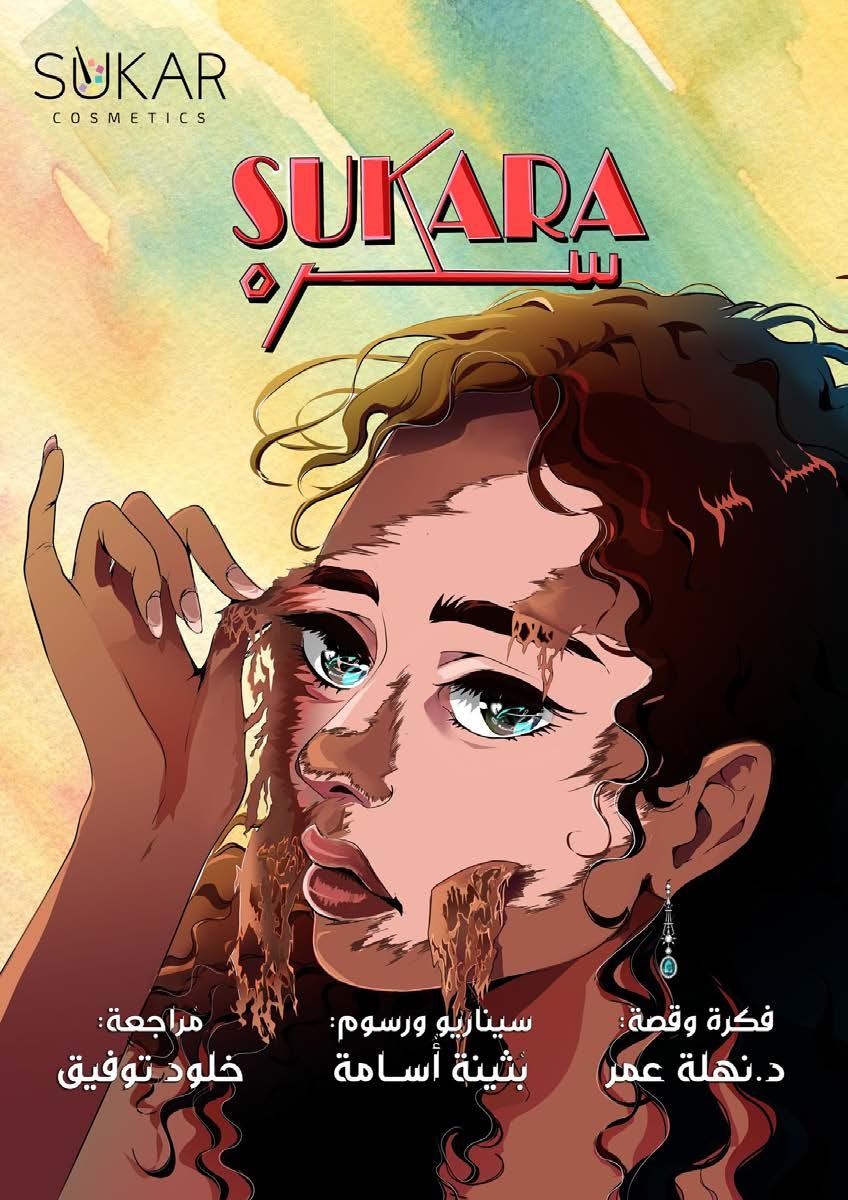

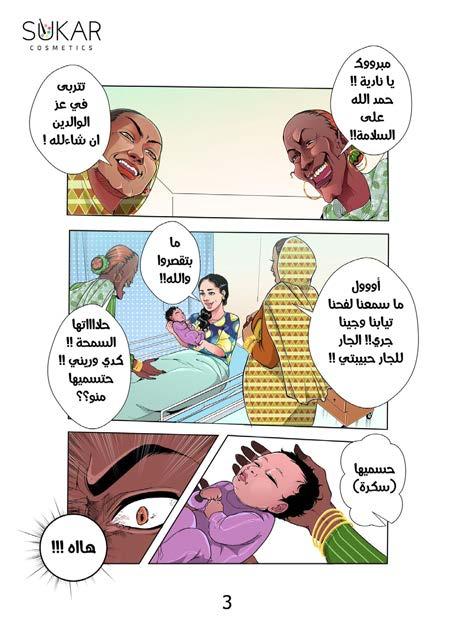

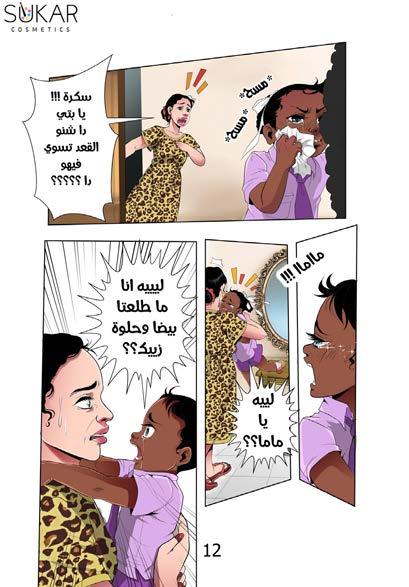

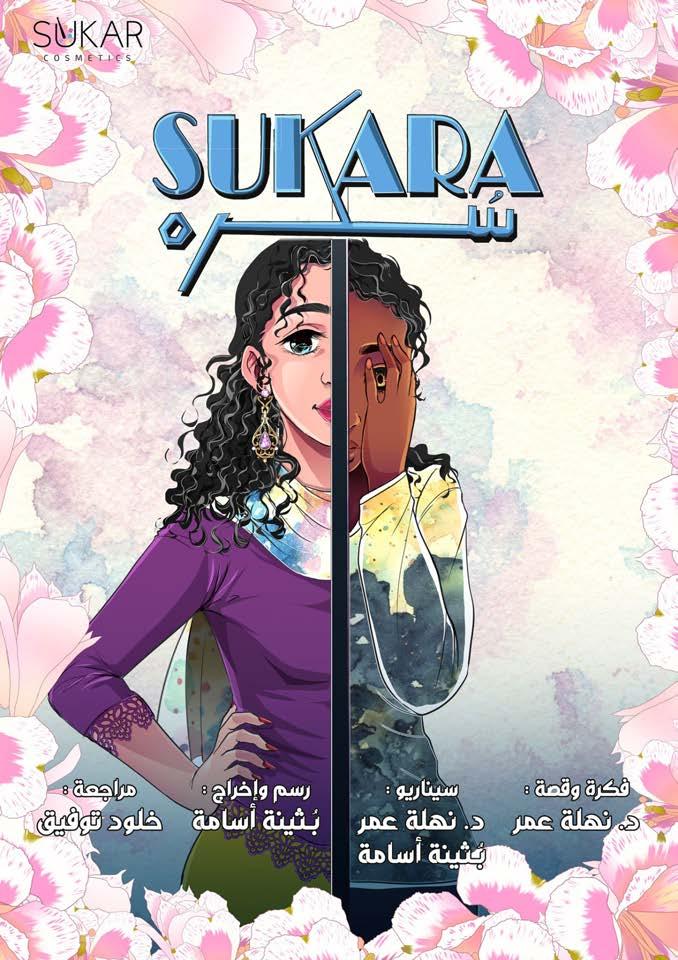

We also meet Akiba, a young artist who is slowly growing a cult following of his own in Nairobi through his platform Akiba Studios. We wrap up the content of this issue with SUKARA. A Sudanese comic book that is challenging and bringing to the forefront the country’s skin bleaching culture.

Special thanks to the entire TAP team, to all our contributors and to everyone else who helped in making this issue possible.

As always, grateful for your support.

MOSES MUTABARUKA Editor-in-Chief, TAP Magazine

03 ISSUE 17 | 2023

SHIFTING THE AFRICAN NARRATIVE (COVER STORY)

WHEN IT COMES TO MUSIC, MOOZY GOT NEXT

35 45 51

05 ISSUE 17 | 2023

SUKARA

KIM MAKIN

THE DOORS OF CULTURE SHALL BE OPENED

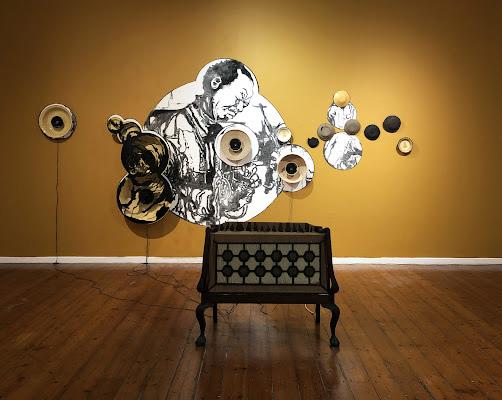

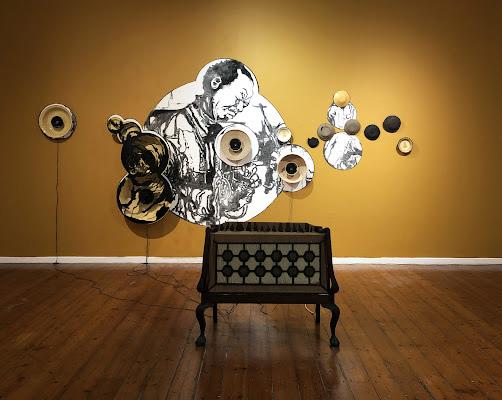

Kim finds photos boring, she likes her art to come to life, to experience it, to touch it and feel its texture, she also loves artwork that is three dimensional. Thus, while completing her Master of Fine Art, she thought, why not marry my background in radio and my love for art. Not long after, she started to explore Sound Sculpture.

Moreover, Kim’s work is deeper than that, she wants her work to have an impact, to start conversations and to challenge and shift perspectives.In her latest work, “The Doors of

Culture Shall Be Opened” an audio and visual exhibition that we were honored to see in person, Kim traces aspects of her family history and her own identity from the lenses of transnational identity and while also examining the historical entanglements across Botswana and South Africa. Below is a summary of our conversation with Kim. We guarantee you’ll learn a thing or two.

07 ISSUE 17 | 2023

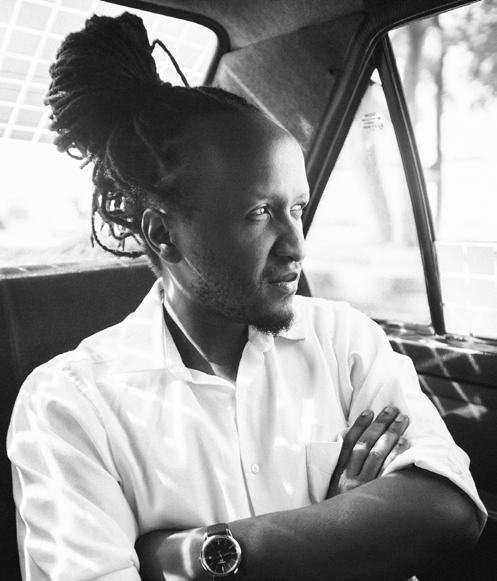

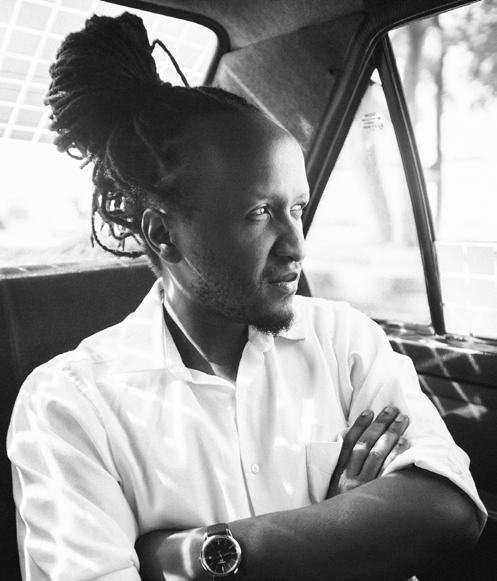

My name is Kim Karabo Makin, I am a multidisciplinary artist based in Gaborone, Botswana.

My art practice mainly stems from my background in sculpture. My interest is in looking at materials and sculptural forms. I like to execute my ideas in 3D. I also have a background as a radio deejay. Most recently, I’ve been working with sound and sound installations, thinking through how I can experience sound as sculptural and taking a particular interest in sound, oral archives, and oral traditions as a form of storytelling.

Wow, I feel like you’re about to take us to the metaverse!

{Laughs} Yeah, that’s the idea, exploring different ways to experience art.

For someone who is completely new to this, how do these two things come together? How did you start exploring sound as sculptures?

My experiment into sculpture and sound came from when I started my Master of Fine Art, and I wanted to marry my background in radio with

my background in art. I wanted to set up sound installations and have their experience be three dimensional - like we experience sound. I guess because I majored in sculpture, I often struggle to think about things in 2D, that’s why I don’t really like paintings or photography. I feel like they’re flat and I like art that’s dynamic, that gives you some sort of experience. With respect to sound installations, and experiencing sound as three dimensional, there’s a sound piece titled “On Gaborone in 1985”, that I made as part of my master’s show called The Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened that you will have seen at the exhibition

I like that you find photography boring…. I’m sure your photographer friends will find this interesting too {Laughs} No, no, no. I respect photographers and the work they do, It’s just not for me. I trust photographers to do their thing, but I don’t think it’s my thing to do. I like for my ideas to come to life, to be able to touch them, to feel their texture etc.

What was the creative process around making the piece “On Gaborone in 1985”?

With this piece, I had it specifically mixed and mastered for surround sound speakers, but then the speakers also became an artwork. So, I suppose you could think of the speakers as the sculptural element because they had their own artistic elements. I’ve been calling them speaker vessels, they were sort of baskets, enamel bowls and these different objects that I have particularly picked as having a social resonance, or a cultural value. And so now with the sound, by placing the speaker inside these speaker vessels, the idea is to activate the sculpture using sound. And then beyond that, because the sound has been mastered for surround sound, there’s different sounds that play from different speakers, so the sound comes out of five speakers. And because of the placement of the speakers, depending on how you interact with the work, you’ll hear different parts of the sound, you know, a little bit louder, or specifically at one speaker as opposed to another. I’m really interested in how that guides the viewer or the listener through the space. I think about sound as sort of activating the space and prompting the viewer or listener to interact with the work in a particular way.

So, how did you find yourself in the arts? Would you say you found art or did art find you?

Art found me…. In primary school, I used to joke around that I’m going to be an artist. But it was a joke. By the time I got to secondary school, I thought I was going to become a human rights lawyer. In fact, my high school friends still tease me about those days because I was very set on doing something along those lines. I was also quite good at math and physics. Thus, I was also being encouraged to do something along the lines of architecture. But, upon

graduation, and by the time I got to University of Cape Town (UCT), I’d enrolled into a General Bachelor of Arts program and was majoring in film and media, art history and linguistics. From here on, it was through the art history course that I really got inspired to get into arts fully.

Was there anything specific that inspired you?

I think growing up in Botswana, I wasn’t aware of the opportunity and potential to make a career out of the arts as we’re still developing creatively. But, through my experience interacting with some of my lecturers at UCT and hearing about their experiences in the arts, I was really inspired. For example, I remember in my earlier classes, there was a moment when one of my lecturers had just got back from the Dakar Biennale. She’s originally from Swaziland, but she grew up in South Africa. She spoke of where she started to now exhibit at Dakar Biennale, which from what I understood was and is the hub of art in Africa. I was just so inspired by hearing her speak. I sent her this super long email and it was really that specific lecture that encouraged me to reapply to fine art. I applied for fine art and architecture and got into both. Then, I was very confused. But eventually I decided to go for art, and I have never looked back ever since.

You chose Art ahead of Architecture, how did your parents receive that?

My parents are very supportive. They sort of left the decision to me, although I think my dad was sort of encouraging me to go with architecture. It has a more stable career path and income. It didn’t help that I also got the acceptance letter from the architecture

09 ISSUE 17 | 2023

department first. So, he was a little bit excited. But to be fair, once I decided, they were all supportive of me and I’m glad that they did. And honestly, I had a few friends that were in the architecture department, so I went to go look at one of their class sessions and that scared me a little bit. Architecture just looked scary, it was a lot of numbers and you had to draw a building from the north face, south face, all these different scales. I just got a little bit overwhelmed, but I am still quite interested in architecture even though I think I’m more interested in looking at architecture from an artistic angle. Not necessarily buildings or houses, but more like public sculptures. Even though I still harbor an interest in architecture, I’m happy that I went the more creative route.

The Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened, what’s the backstory of this exhibition and work?

The Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened is an audio, visual exhibition by myself. It is a personalized tracing of aspects of my familiar history and specifically looking at transnational identity and the historical entanglements across Botswana and South Africa. Most of my research theoretically, was looking into the Medu Art Ensemble, which was this ensemble or cultural organization based in Gaborone Botswana in the late seventies and eighties.

It was composed mainly of exiles from South Africa. And the whole idea of the organization was to think about ways that they can use culture as a weapon or a tool for change, specifically against the apartheid regime. The title The Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened, which I saw in a book, is a reference to a poster that was made by the Medu Art Ensemble. When I saw the poster, I was so intrigued that I then went and looked through a lot of their materials. They would have a newsletter that they

printed regularly, which had a lot of radical theories.

They would also have posters inside this newsletter which were smuggled into South Africa because at the time, they were considered a propaganda organization. An interesting element of this is that, although this Medu Art Ensemble occurred in my hometown, I never learned about them until I moved to Cape Town for school. I found this quite ironic. So, through my research, I was trying to get my hands on one of their newsletters to see what they were about, and I found two of them in UCT special collections library. To my surprise, only one of the newsletters I found had a poster inside. And obviously, coming from the art perspective, I was most interested in this sort of visual element of their practice. I was so amazed to find this one poster and that’s what kind of inspired the whole exhibition. My research was just guided by kind of reimagining this poster

The Doors of Culture Shall Be Opened, is actually a line from the South African Freedom Charter. It’s referencing the fact that under apartheid, there was a lot of censorship of ideas, as was the case with Medu. In fact, the full sentence is that The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall Be Opened.

I think it’s relevant today, for one thing, having spent quite a lot of time in South Africa, there are still remnants of the apartheid regime that you experience daily in South Africa. But I think beyond that, within the context of Botswana, it’s also important for me to prompt for us to open the doors of culture, because there’s still a lot of growth and creative development that I would like to see here at home. It’s just an encouragement for us as artists to build communities for ourselves and to uplift one another until we can get the full support of the rest of the country.

What would you say are the historical entanglements of southern Africa? Both culturally and creatively?

Well, it’s very layered. Where do I even begin? In the first place, it was quite interesting for me, specifically with the example of Medu Art Ensemble, that although it happened in my hometown, that I only learned about it when I moved away from home. It was interesting to think about this moment in history that in some ways is celebrated as a South African history or as a South African moment in Art history, although in terms of physical location, it didn’t happen within the national borders of South Africa.

Thus, I’m interested in exploring Medu Art Ensemble as a moment or a case in point, for example of a historical entanglement. And I suppose my whole project is interested in relocating it within the context of Botswana, because I don’t think it was by accident that it happened here. I’m interested in this sort of shared history. And, if we take it a step further, culturally, there are a lot of things that make us similar across the borders of Botswana and South Africa specifically, before I even get to the rest of the region and then the rest of the continent.

For another thing, it was quite interesting for me to kind of navigate my own identity in South Africa culturally and traditionally, but also in terms of my national identity. I am a Motswana, I’m from Botswana, but Tswana is also one of the official languages of South Africa. It’s quite ironic because technically speaking, there are more Tswana speaking people in South Africa than there are in the whole of Botswana.

This likely has more to do with the fact that Botswana’s population is so small. But it’s quite ironic that our national language is Tswana, but

that there are more Tswana speaking people in South Africa than the whole of Botswana. Thus, in a way, I was quite interested in this idea of to what extent does being a Motswana include some aspects of South Africanness, if I can say that. It almost feels like we are connected in some ways. There’s an aspect of ourselves that we have to understand through a South African perspective.

This just became an interesting thing for me to reflect on. And if I take it a little bit further and look at our history, Botswana is recorded as I believe the only country that ever had a capital city that was outside of its national borders. Our capital used to be Mafikeng, which is in South Africa, and then only after independence did our capital become Gaborone.

So again, it’s this idea that there’s an aspect of Botswana or of being a Motswana that is kind of encompassed in South Africa. And if you look at the history, Botswana was supposed to be absorbed into the Union of South Africa at some stage. Even after gaining our own independence, there was a time we had protection from the Queen to deter this. These are some of the entanglements. We were implicated in South Africa’s history. We were implicated by apartheid South Africa, even though we weren’t necessarily directly involved.

That is quite informative, culturally, I imagine there’s a bit of entanglement as well.

Yes, if we think about specific cultural symbols like baskets, we see how this specific symbol of cultural value and cultural identity gets translated across borders. So, whereas we are well known for our distinct basketry, it’s interesting to see the different sort of forms of baskets that you find just across the border in South Africa.

There are things that connect us historically or culturally that are far beyond anything we can define by national borders. These elements go beyond these very arbitrary borders. And I guess that’s why I’m also interested in this idea of transnational identity, because I’m interested in this concept of identity and how it travels across borders. I don’t think “identity” can necessarily be fixed by national borders, so our sense of selves exists in different forms depending on context.

What other cool historical gems did you uncover while writing your thesis?

I found that apparently, our local radio networks here in Botswana used to be governed by the South African Broadcasting Corporation, which was interesting during Apartheid, because it meant that in some ways, we got the specific public apartheid broadcasts. But when Botswana became an independent republic, the setting up of a national broadcasting radio station like Radio Botswana, was a way to cement our national identity. So, it was interesting to think about how sound can also be a symbol of identity in a way.

Identity is another strong theme in your work, how do you define identity?

Well, I’ve been trying to define it for years, and a short answer is that I think that identity is fluid. I think that it also has the potential to be multiple or plural. Identity is not necessarily fixed or static, it can change. In some ways, I think that identity is relative to context.

In my experience, I find that my identity is sort of defined by where I am at the time, who I’m speaking to, and perhaps even their own historical understanding of themselves, their identity, and their upbringing in that

11 ISSUE 17 | 2023

respect. Identity in my experience has sort of been like a negotiation. In some ways I’ve had to consider the way that I identify myself and how that might be different to how someone might identify me.

It was interesting for me to think about my identity within the context of Botswana and then how that looked quite different, or how people experience me quite differently within the context of South Africa. I found that perhaps, while I might identify myself, let’s say, as a coloured person within the context of Botswana, being coloured in Cape Town means something very different, because there’s a whole culture attached to it that I don’t necessarily relate to. It was being challenged in that way. A lot of the time I would get asked the question, what are you? When I was in South Africa, and that’s when I started to think that for example, in a post-Apartheid South Africa, unfortunately there is still this sort of segregation of races. A lot of the time, within the context of South Africa, it is quite important even today for people to identify themselves by their race.

Growing up in Botswana, I didn’t necessarily have to do that in the same way. So, it was interesting for me to sort of grapple with my identity and what it means to have a racial identity, to have a national identity, to have a cultural identity and to what extent are all these things different and the same.

Interestingly, here, customarily, in terms of forming a part of a tribe, you’re supposed to be from where your father is from. There’s this idea that your tribal allegiance is passed on through your father. And that’s quite often a trend in patriarchal societies. So, when I think about my identity as being layered, there’s also a gendered aspect included. Then, there’s also a traditional aspect included. And in my case, that was quite complex because my dad isn’t

originally from Botswana, although he later naturalized to become a Motswana. So, someone might ask me, oh, where are you from? And I would say Botswana. But if you can’t say which tribe your father is a part of, then to the average Motswana, they’ll be like, you’re not actually a Motswana.

And so it’s quite ironic because although I’ve only known Botswana to be my home, and I learn a lot about Tswana culture through my mom, and as much as I would like to proclaim that I am a Motswana and claim my mom’s village, Serowe, as my village, if I were to really take it to the extent of being very technical about it, because my dad is not actually from here, in believing myself to be a Motswana, I also simultaneously have to accept that I’m not. Or that other people might believe that I am not. Generally, identity is this weird conversation, an internal debate and something that you can decide for yourself and even though someone might identify you differently, that’s OK! It’s the same as home: I’m interested in thinking about home. Is home a specific place or do we carry aspects of home every day and everywhere?

What do you hope to achieve with your art?

I’m interested in art that has a social impact. I am committed personally to some sort of social change. And in some ways, I’m interested in continuing the ethos and ideas of the Medu Art Ensemble in that way. Although I didn’t become a human rights lawyer like I thought I would in high school, in some ways, I’m interested in making art that can impact people and impact social change in one way or the other.

I’m attracted to offering conversations that can resound outside of the gallery space. Artwork that people can go home and discuss with their

friends and loved ones. That, for me, is what defines a work as successful, if we’re able to have conversations about it. I’m interested in making art that can be engaging and intriguing and that can spark a long-lasting interest. Eventually, I’m hoping that I’ll be able to ignite this interest in the average Motswana, to commit myself to creative development locally.

Outside of art, what else inspires you?

I am really inspired by my community and my peers. Even at school, I was quite often inspired by my classmates more so than my lectures. I think we learn so much from one another, and that’s what inspires my practice.

I’m part of an arts collective that calls its The Botswana Pavilion. The idea behind The Botswana Pavilion is to create a space or a platform to build an art community in Botswana in the absence of national support. We want to have conversations around what it means to be a Motswana creative and what our creative identity looks like and to have that as an ongoing conversation among ourselves until we can set up institutions and truly establish the art industry locally.

What’s next for Kim?

I’m currently working on an online residency called Ja Ja Ja Nee Nee Nee with a radio platform based in Amsterdam that is dedicated to the arts. In the next month or so, I will be broadcasting the final output of that residency. I’ll then continue doing some more research related to my exploration into Medu Art Ensemble, and I’m hoping to have more conversations that unpack my thinking through radio sound as having a specific cultural value. In the meanwhile, I’m also working on new artworks, which I’ll hopefully exhibit early this year.

13 ISSUE 17 | 2023

KIM MAKIN

15 ISSUE 17 | 2023

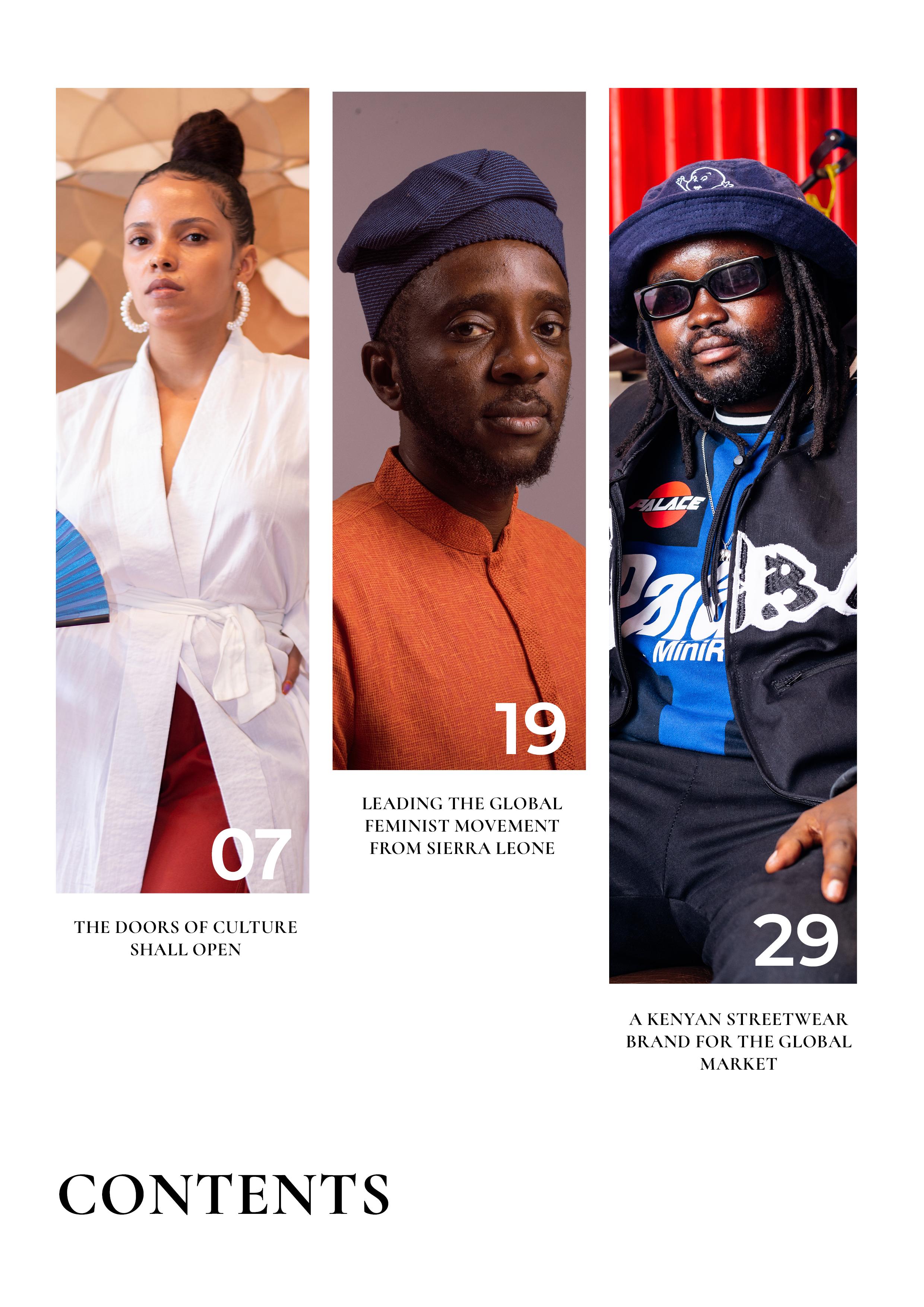

LEADING THE GLOBAL FEMINIST MOVEMENT FROM SIERRA LEONE

Ever since anyone can remember, Chernor Bah has been campaigning and fighting for one cause or another. So much so that he was once nicknamed the “Minister with no Portfolio.”

When Sierra Leone’s civil war ended, barely into his teenage years, Chernor was disappointed that the rebuilding process did not include children like him who had been deeply affected by war. So, he campaigned to have a “Children’s parliament”. He didn’t fully get his wish, but the government approved of a “Children forum”. He would go around the country mobilizing and collecting stories of kids affected by war and sharing them with leaders and policy makers. Years later, as an adult, he would go on to take a similar role at the United Nations in New York where he would travel the world to conflict areas to collect stories of child soldiers and children of war and come back and share them with the UN security council.

When the Ebola crisis hit and brought his country to its knees, Chernor left his comfortable job in New York, to join his countrymen and women in tackling the crisis. While on the ground, he realized that even though women, as primary caregivers, were the most affected, no one was looking out for them. No one was communicating in the

language that they could understand on how they could protect themselves or their families from the deadly virus.

After the crisis ended, he knew he couldn’t just go back to his nice apartment in New York and live comfortably with his beautiful wife and kids. He had found yet another calling, and he hasn’t looked back since.

Today, to give you a glimpse of the work that he does alongside his team at Purposeful, in 2018, Chernor led and helped create a movement called “The Black Tuesday” that helped push Sierra Leone to declare Rape a national emergency and thus change rape laws and create specialized rape courts. And when the government banned pregnant girls from going to school, Chernor and team protested, sued the government, then wrote the bill and policy that the government eventually adopted; providing for a radical inclusivity in education policy and guaranteeing that pregnant girls, disabled and children from poor communities all have access to education. We’re pleased to share below a recent conversation we had with Chernor, at Purposeful Headquarters, during our visit to Freetown, Sierra Leone.

19 ISSUE 17 | 2023

My name is Chernor Bah. I’m the co-founder and co-CEO of Purposeful.

Purposeful is a feminist organization with an ambition to remake the world with and for girls. We’re proudly headquartered here in Sierra Leone, but we have footprints in over 100 countries around the world.

What is your definition of a feminist and how does a man get to lead one of the biggest feminist movements on the continent?

I get asked all the time, how does a Muslim African Fulani man identify as a feminist and co-lead a feminist organization that is dedicated entirely to girls, and it’s a complex set of answers. For me, my definition of feminist is very simple. It’s the radical belief that women and girls are human beings and the commitment to do everything in your power to ensure that they enjoy and live as full human beings in every way, shape, and form.

I have been socialized like most people who are born and grew up in patriarchal societies, to not believe in that, to not see the world from that perspective, to continue to see women as second-class human beings, that girls are less. That’s the socialization that I have. But I also have had the privilege of education, the privilege of being raised by a single mom, the privilege of my personal favorite human being my grandmother, who was married at age 12, had 12 children, eight of them died and 4 lived past 100 years. That’s the icon in my life. But what has informed my feminist identity and my feminist journey is both that personal history and my own learnings and commitments and questioning and constant learning and relearning. This is why I say with confidence that I’m a feminist. And I know that just saying that

triggers debates, questions, and curiosity, sometimes even backlash, because a lot of people don’t think that a man should be a feminist. I strongly disagree. I believe that being a feminist is all about having a set of values and a commitment that one tries to live by every day.

You’ve previously mentioned that you’re a feminist and not an “equalitarian”, please expand.

I’m not an equalitarian, as some people call themselves. I’m a feminist because I understand and accept that the root cause of injustice and inequality in this world are intentional sets of policies, Laws, practices, and beliefs that discriminate against females, that treat girls as less than full human beings. That’s my starting point. That’s the premise of my belief. It’s not just, oh, everybody should get the same. No, it’s that girls and women have been historically discriminated against and that we need to do everything we can, including affirmative action, when it’s appropriate to balance that equation, to make sure that everybody can have access to the same opportunities.

That’s the work we do at Purposeful, that’s why we’re very bold and unapologetic about funding girls, about our hiring. Over 90% of our staff are female. We make sure that the opportunities we have at Purposeful, we give girls priority because that’s the world we imagine. We want to create a world where women and girls can live in their full power, where they can have access to opportunities. We understand that the world as currently constructed does not give them much of an opportunity. The basic premise of Purposeful is to recreate, and to remake this world so that girls are living in safety, in dignity, and in their full power. To do that, you need to create a movement that is led with

and is for girls. That is powered by girls themselves and especially girls who are often the most marginalized, the ones who are most removed from power.

You don’t create sustainable change by investing in the people with power and trying to change their mind. There’s no evidence of power giving up power voluntarily. The evidence is you build the power of those without it, and then they challenge the status quo.

What are some of the key things that you do at Purposeful?

At Purposeful, we’re really doing four major things. One, redistributing power. That’s the basic premise of Purposeful. We believe that money is power. Thus, girls need to have access to money. And we do that by removing these colonial barriers that are placed around the distribution of money such as having to write formalized proposals, we cut that all off. You don’t need to be writing reports to us every time! You don’t have to be registered. We cut all these barriers off. We have different schemes here that are led by the amazing women at Purposeful that take money in boxes into poor communities across this country and give this money to girls and say, we trust you to go on and do amazing things and we’ve got countless stories of remarkable things that’ve been done with that money.

Giving girls money is a fundamental point of our work, and it’s what leads to the most controversy, the most pushback. People think it’s risky to give girls power, they will fail. Girls are worth the risk, and in fact when you give girls money, we see that in fact what happens, is that they can do amazing things in their communities. And even if they fail with the money in terms of the project, you know, failures are often reserved for the

privileged. Let them fail! We want them to have the right to fail because that’s part of the journey of growth.

The second thing we do is to intentionally build girls’ power. At Purposeful, our work is political. That’s why we start by identifying ourselves as feminists. To be a feminist is political, It’s not passive. So yes, we do help girls to raise their own consciousness. We support them to form groups and collectives led by mentors. We give them radical political education, we let them see that the source of their oppression is patriarchy and that patriarchy manifests in different forms in and around them. We then give them the tools to be able to confront that and deal with it.

One of our programs around building girls’ power has over 17,000 girls in all the districts across Sierra Leone. So that’s a big part of what we’re doing. But we’re also a hub, we’re a movement- building hub. That also involves organizing power and bringing different groups together. We just hosted the largest conference in the history of Sierra Leone of any kind. We had 950 delegates from 41

countries around the world. That’s the vision of Purposeful; to bring a feminist convening together, to say, Let’s discuss, let’s push together, let’s call for changes.

And at that conference, the President of Sierra Leone announced that the cabinet, with his approval, will now put forward a safe mother bill that will decriminalize abortion in Sierra Leone, and that will guarantee choices for women. That’s a part of our work. We believe you need to organize the movements, organize people who think like us, and people who don’t. This is a big part of our work. To organize the movements. We do that here; we do that as well around the world with the global feminist movement that’s thriving and the people that we give our money to.

And finally, we have active policy work that seeks to change policy. Purposeful helped to create a movement here called the Black Tuesday Movement that helped push this country to declare rape a national emergency and change rape laws and create specialized rape courts and do a lot of other reforms, we were in the middle of that. Not just pushing forward, but also writing

those reforms. We write policy, we work with governments to change policy. Prime example, here in Sierra Leone, the government had banned pregnant girls from going to school. We led the opposition to this while working with other partners, we sued the government, we pushed back, we led petitions against the government, but then we were also drafting policy around the issue – something that is unique of Purposeful: we don’t just shout outside - we’re also in the room. We wrote the national signature policy for the education ministry in Sierra Leone, a radical inclusion in education policy that guarantees that pregnant girls, disabled and children from poor communities can all have access to education. We wrote that policy here at Purposeful.

It’s an example of how our work is crystallized. We do all these things: the money, the movement building, but we’re also in the room to write and to shift policy. We’ve written policies for governments; we have worked on changing different laws and policies. I was personally hired to write the National Youth Policy in this country, I was a national lead consultant for that.

21 ISSUE 17 | 2023

And finally, I’ll add, embodying our values. So that’s how we work with women and change our own internal practices at Purposeful to show that the world we imagine, the decolonized world where women and girls are living in full power, is the world that we also embody. How do we pay, how do we promote, how do we treat people?

How do you define power?

Power is complex, but essentially, it’s the ability to control. Ability to influence and shape and dominate. It’s visible and invisible. It’s most potent when it’s invisible and when taken for granted.

How can this revolution and movement attract and bring allies onboard?

We understand that ultimately this revolution is going to need everybody. And the point of a revolution is to create openings for people to join at different phases. And I personally don’t believe in exclusion. I don’t believe that we should just shut the door, or we should judge people based on where they are. We’re all socialized differently, and people are at different stations in their life.

For example, we had a chief who was a polygamist, he married five wives. But this chief decided that in this community, he was going to personally give scholarships to girls and support girls in these very, uh, conservative districts where no girls had graduated from high school. And he was going to support girls by giving them scholarships to go study and come back and develop his community.

He had found his awakening. Now, if we judge the chief just because the chief is a polygamist, then we have no chance to engage and change that society. But just by that act, just by the example of his belief in education,

that chief was showing us that there was hope and it was an opportunity.

So, a chief like that, we recruit them, we work with him, we train him, and we support him to interact with other chiefs, to share why he believes in girls’ education. And that’s how you build a revolution. We must engage people, I do that a lot with my friends, if you don’t, you create a feeling of exceptionalism, people then think that - Yes, Chernor is a feminist because he’s been to the West! Because he has lived in New York.

Would you agree that for the past few years, there’s been a strong backlash on feminist movement and agenda?

There’s always been a strong feminism backlash. There are conversations about how the future we want will leave boys out and boys behind. In fact, I remember talking to a group of boys in a village outside of Freetown, and they told me that because all your programs are for girls, that this was the exact reason why they go out there and impregnate them, as a response. We want to show you that you should come talk to us because we have the power, we have the control, and some men who are married to these girls will beat them, will take their money, so that’s the reality of an extreme form of that backlash. And it’s kind of like the male Lives Matter backlash. But I think that it misses the point, the point of a feminist revolution is that when girls are free, we are all free. I think Nelson Mandela said that “I’m not fighting for black domination or white domination; I’m fighting for equality”. The reality today is there is domination of girls. That’s the reality. And it’s not just about laws, it’s also about practices. It’s about the fact that now you ask any average family, including in this city, what’s your preference for a child?

Is it a boy or a girl? Overwhelmingly,

it’s a boy. Families prefer boys and that’s the foundation of all discrimination. Because that leads to how resources are allocated, even how your birth is celebrated, what schools you chose to go to. And then the things you have to contend with in life, sexual violence, just your body being sexualized and used as essentially a credit card for anything you want to navigate in this world. Those are the reality. And those are not natural. They are socialized systems that we have created that lead to this aggression on the female body throughout their existence, from birth onwards. Now, we can accept that as a reality and say we want to change that, and the way we change that is by investing in girls so that we create a different world, a different system.

An argument often leveled against what you just said is that if we’re only investing in girls, boys will be left behind.

I say check out Africa. Who are our presidents? There are no women presidents. I can only think of one or two here and there. Who are the CEOs? Who are the leaders of companies in whatever industries you choose? This is the reality of the evidence in front of our eyes. And the way to change that is intentional investment over time. It does not mean that men and boys should be cut out.

I’m a father of just boys. I don’t think nor believe that. But the reality is when resources are meant for everybody, they tend to then go more to boys. We are for the state and everybody providing resources to the general public, but we also know that historically when it has been meant for everybody, it has not gotten to girls and that’s what we’re trying to change.

I think the primary principle of feminism is a commitment to

justice. So, equality, but rooted in an understanding of history and context and the history and the context is that girls and women have been disadvantaged and that inequality is not an accident. It’s because we have a system in place that discriminates against women and girls.

Being a feminist is about a commitment to justice, a commitment to equality, commitment to fairness. And I know sometimes people misunderstand fairness as 50/50. That’s not if you have had 90% of the pie all over the time. 50/50 is not going to be fair. Fairness is going to be equitable. So, you give what you need so that we get to a point of true equilibrium which I think is the goal.

So, I think that those are the fundamental principles. But I also believe that feminism does not exist in isolation of core human rights, a commitment to justice and equality for all. So we talk a lot about intersectional feminism that you have to see not just this commitment to these values, but you’ve got to see the world and the institutions and the structures that create and perpetuate injustice and inequality.

What’s the one principle that has kept Purposeful going and standing?

What has kept purposeful going is that we have been very clear about our politics. We’ve been very clear

about ideology. We’re the first known major organization in this country that named itself feminist. This is a 70% Muslim majority country, extremely conservative. We put on our name the word feminist when we are launching, we said we are feminist. We invite the critic, we say, this is who we are. That’s our politics. And that’s important for how we raise funds, who we engage, how we partner with folks and the issues we take on. And we were never shy to tackle difficult issues.

What would you say is the most significant achievement of Purposeful?

I know this will sound cliche, but the most significant achievement of Purposeful is the culture we have created. It’s the team. It was the hardest thing to do, to recruit the right sort of people, to build a culture because everything else comes from the culture that we have. We truly have a feminist culture, young dynamic people who are now owning the space. You no longer need to hear from me, they are leading. One of the first colleagues we hired, who is now a 29-year-old feminist champion,

is currently studying in Sussex on a full Purposeful scholarship. Now, you don’t hear that from a local organization here. That we pay for our team members to go study in the West when they get accepted into universities, and we give them full scholarships.

As of this week, we’re now officially a four day a week organization. At Purposeful, you only work from Monday to

23 ISSUE 17 | 2023

Thursday and Friday, you can go back and do whatever the hell you want to do with your life. And that’s something we’re proud of. We give the most generous parental leave you know, paid parental leave. You can take up to a year off if you want to. Most people take a minimum of six months, all guaranteed pay during that time. We hire people who are eight months pregnant and still give them full parental leave. That’s what we’re most proud of. It’s that we’re able to build an institution that embodies the world that we imagine.

We’re also very proud of the ways we’ve been able to mobilize resources at Purposeful. We’re very lucky to be in partnership with progressive donors who share in our feminist ideals and beliefs and who give us the flexibility to move money in the ways that the formal and informal groups of women we serve want. We’ve been very lucky here at Purposeful to raise significant resources. Our annual budget is now around $6 million, but we know that this is not our money, we’re just custodians of the money that belongs to girls. That belongs to feminist groups and activists. And we are eager to move that money to them in the ways that they want. It’s our goal in this world; to move as much money as we can to girls and feminist groups in the ways that they want it.

As much as you’re a stout feminist, you’re also a firm Pan-Africanist, tell us more.

I absolutely believe that you must be a Pan-Africanist and a feminist at the same time. That’s why I talk about: Intersectional feminism. You cannot be a feminist if you do not understand that patriarchy is tied to capitalism and capitalism is tied to colonialism.

You must be against all these things because they are very much interconnected. Patriarchal forces are propped up by capitalistic forces,

and capitalistic forces take their roots in colonialism. They are the same things. They are connected. It’s the system that treats the other as not human enough, that treats black, brown bodies as less, that treats us as commodities and if you are a feminist who’s interested in uprooting and smashing the patriarchy, you will be interested in smashing colonial powers.

And that’s what Pan-Africanism is about. It’s about finding our own voice, it’s about the African being a full human. Just as feminism is about females being full human beings with the ability to chart their own path, their own future.

What are the most critical issues facing girls and women today in Sierra Leone?

The most critical issues confronting girls and women in this country are: One, cultural violence. There is cultural violence that permeates our society, whether it’s transactional sex, teenage pregnancy, female genital mutilation, it’s just a violent place for girls to exist.

The second one, I would say, is voice. It’s having their voice and agency, it’s the permission to speak up for themselves, it’s believing that their voices matter in society. And it’s hard because our institutions of politics are still dominated by men. The community institutions are dominated by men, the traditional institutions are dominated by men. It’s seeing themselves in those spaces and being able to claim and be part of those spaces.

The third one, I would say, is power. Having real access to power, being and living in their full power, where girls and women are leading. People who control power are still men and they’ve treated power as if it’s exclusive to them. They’ve shut down the doors of power to girls.

All these three things are manifested

and embedded in our systems. In our laws, in our practices, in our traditions. Violence is just everyday existence. We still have child marriage laws and the anti-abortion laws are still in our books. So, those three things, violence, voice, and full power are the trinity of the challenges that we need to confront, to create the future that we imagine.

What is your vision for Sierra Leone?

My vision for Sierra Leone as a country is a society where every citizen is treated and respected for the awesome human being that they are, and they can live in their full power. My vision for my country is a feminist future, a future where girls are not surviving but thriving, where you don’t have to worry about the existence of violence, of female genital mutilation and courting, of child marriage, of teenage pregnancy, of being criminalized for the choices that they make over their bodies. It’s a future where girls can go to school and be anything that they want to be, not just in theory, but in practice. Where it’s not news that a girl can grow up and become president. Where it becomes mundane that girls and women are CEO’s running this country alongside men. That’s the future we walk towards. That’s the future we’re trying to build at Purposeful. And I believe that this future is possible and that it’s happening.

25 ISSUE 17 | 2023

I absolutely believe that you must be a Pan-Africanist and a feminist at the same time. You cannot be a feminist if you do not understand that patriarchy is tied to capitalism and capitalism is tied to colonialism

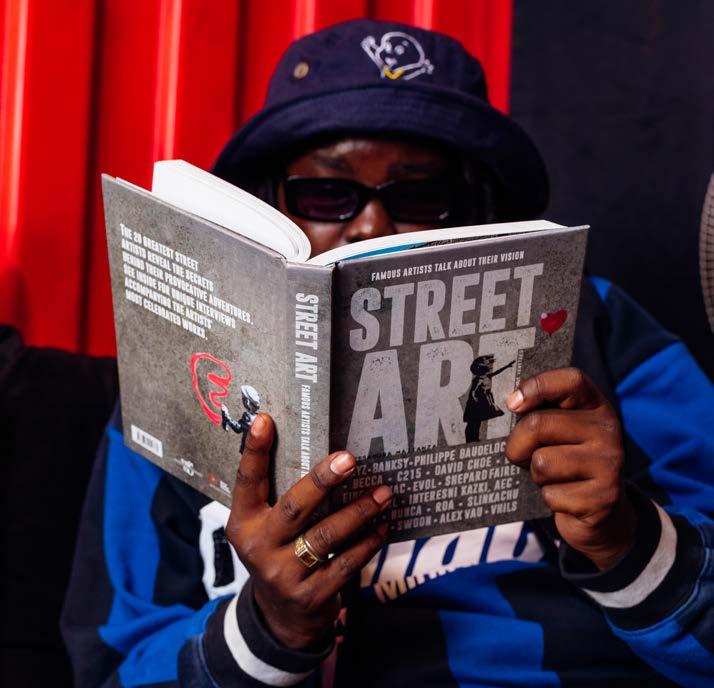

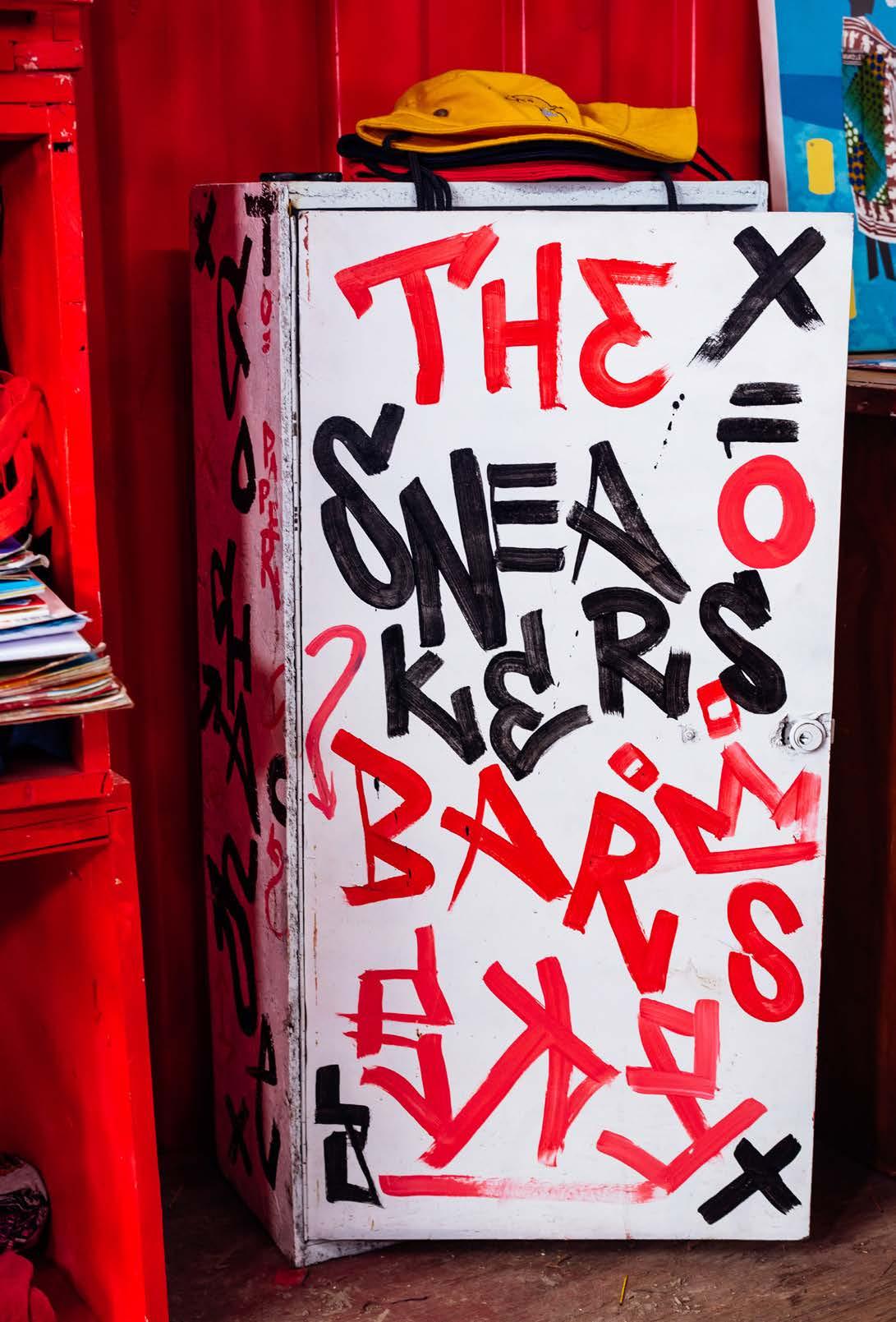

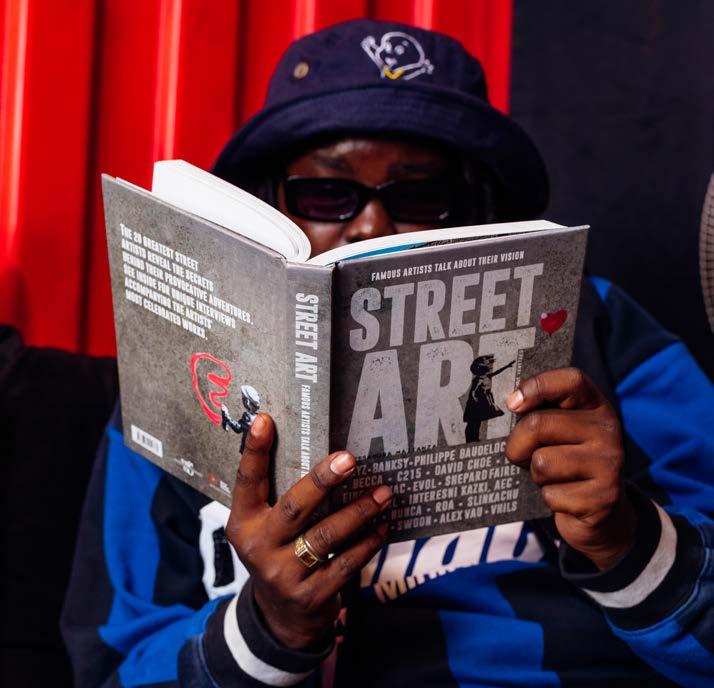

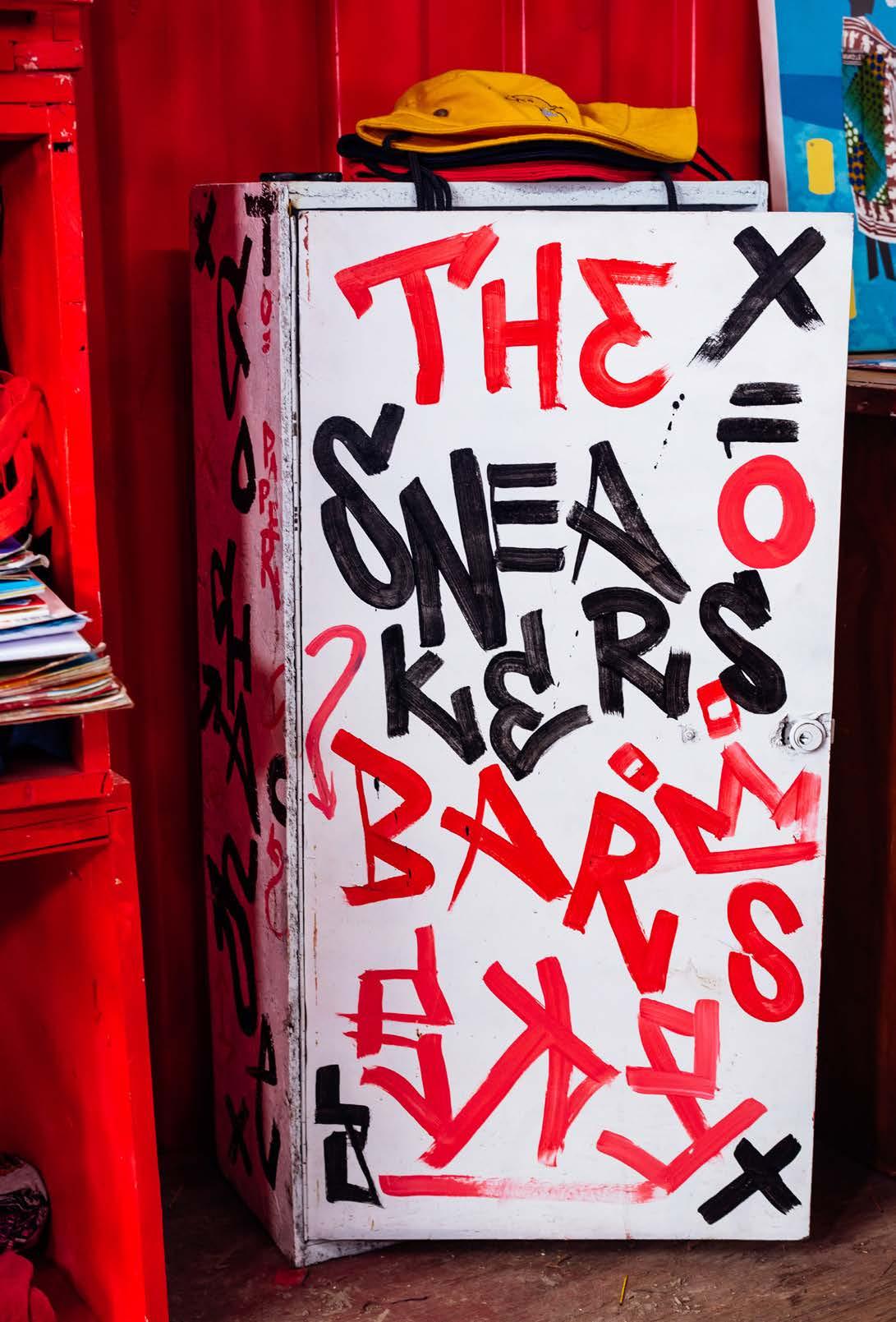

Streetwear is a key pillar of Nairobi’s cultural identity. Just like Matatus are. It is a celebration of diversity and self-expression, a lifestyle that goes beyond fashion and the designers and creatives. As part of her residency with TAP, Gathoni Matu, who is a Nairobi based visual storyteller directed and produced a short documentary series called “Nairobi Streetwear Fashion” that follows four trailblazers’ in fashion entrepreneurship, capturing their individual processes and the electrifying streetwear scene emerging from this vibrant city that is Nairobi. We feature David Kipkoech of “Akiba”, one of the brands featured in the series and one of the hottest streetwear lines in the streets of Nairobi.

29 ISSUE 17 | 2023

My name is David Kipkoech, but I’m popularly known as Akiba. I am a multidisciplinary visual artist and art director based in Nairobi. I use various mediums to tell new African narratives. Mediums such as oil, paintings, illustrations, collages, film photography and fashion. My art is based on traditional cultural life with a taste of Afrofuturism combined with street culture and is infused with science fiction.

I’ve always been a connoisseur of fashion and art, but I’d say once I started drifting garments for myself, that’s when I began to enjoy the process and my love of fashion grew.

I’m very grateful for having the power to experiment on a lot of my projects and the gift of selfexpression. My art has opened so many doors for me globally.

Being very multidisciplinary, I experiment a lot on my projects, and I try to make products that really speak for Kenyan streetwear.

I’m very happy that people consume the products that I make and are inspired by what I create as a product. So, I’m very happy that Nairobi is in this position where guys are

very experimental and want to show and express themselves a lot. Guys are thinking out of the box and it’s creating this atmosphere for creativity.

The Nairobi Streetwear scene is in a really good position. Guys are creating unique styles, trends, music, art, and I like how it’s growing every day. It feels like a vibrant creative melting pot. Guys are really expressing themselves and breaking boundaries. I also like how a lot of new artists right now are collaborating with each other and creating their own spaces and creative pockets.

I’m here to inspire and help other artists find a voice. We need to create more spaces for artists to feel free and to express themselves and to learn from each other.

The next step for Akiba Studios is global domination…..

31 ISSUE 17 | 2023

AKIBA STUDIOS

33 ISSUE 17 | 2023

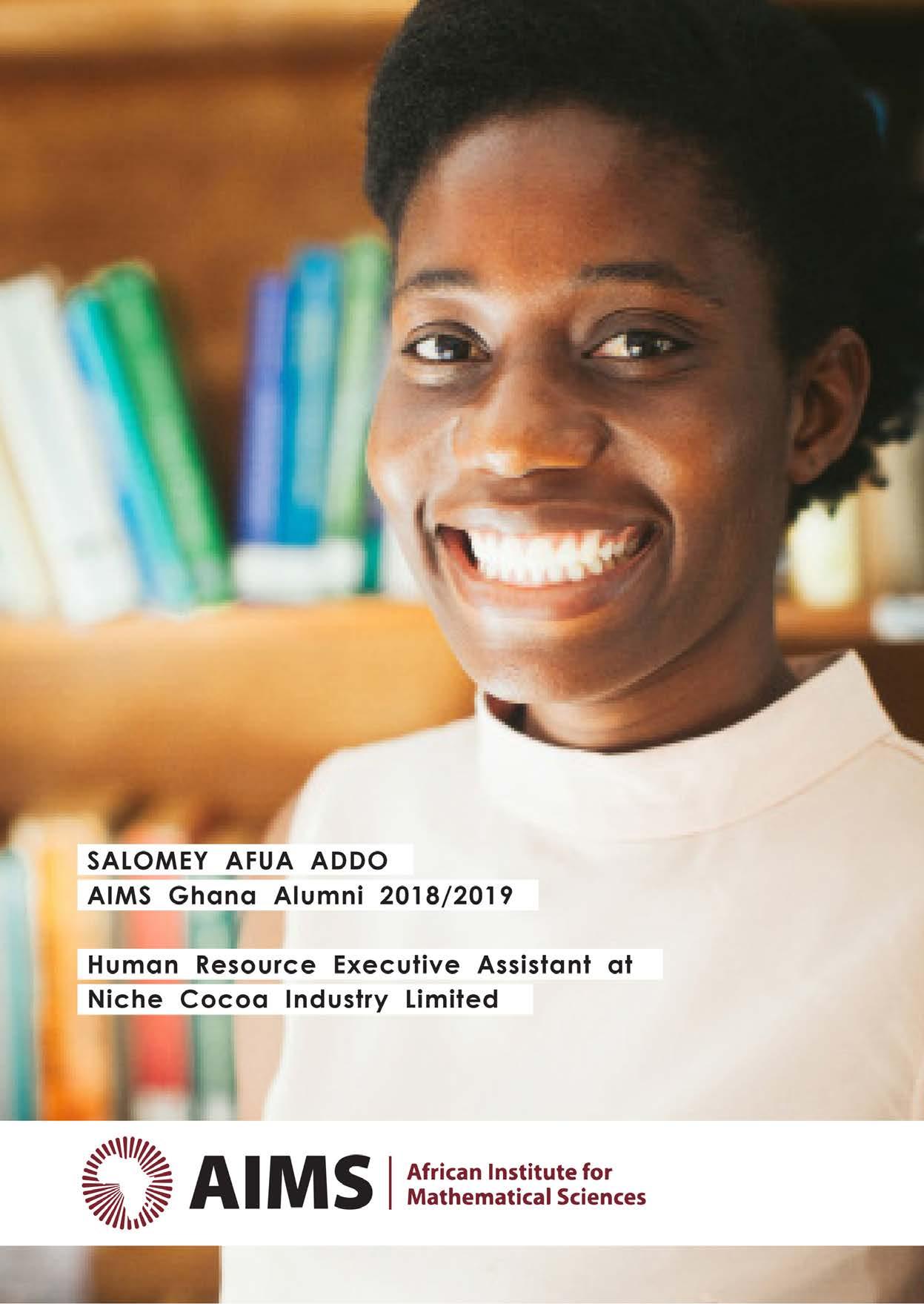

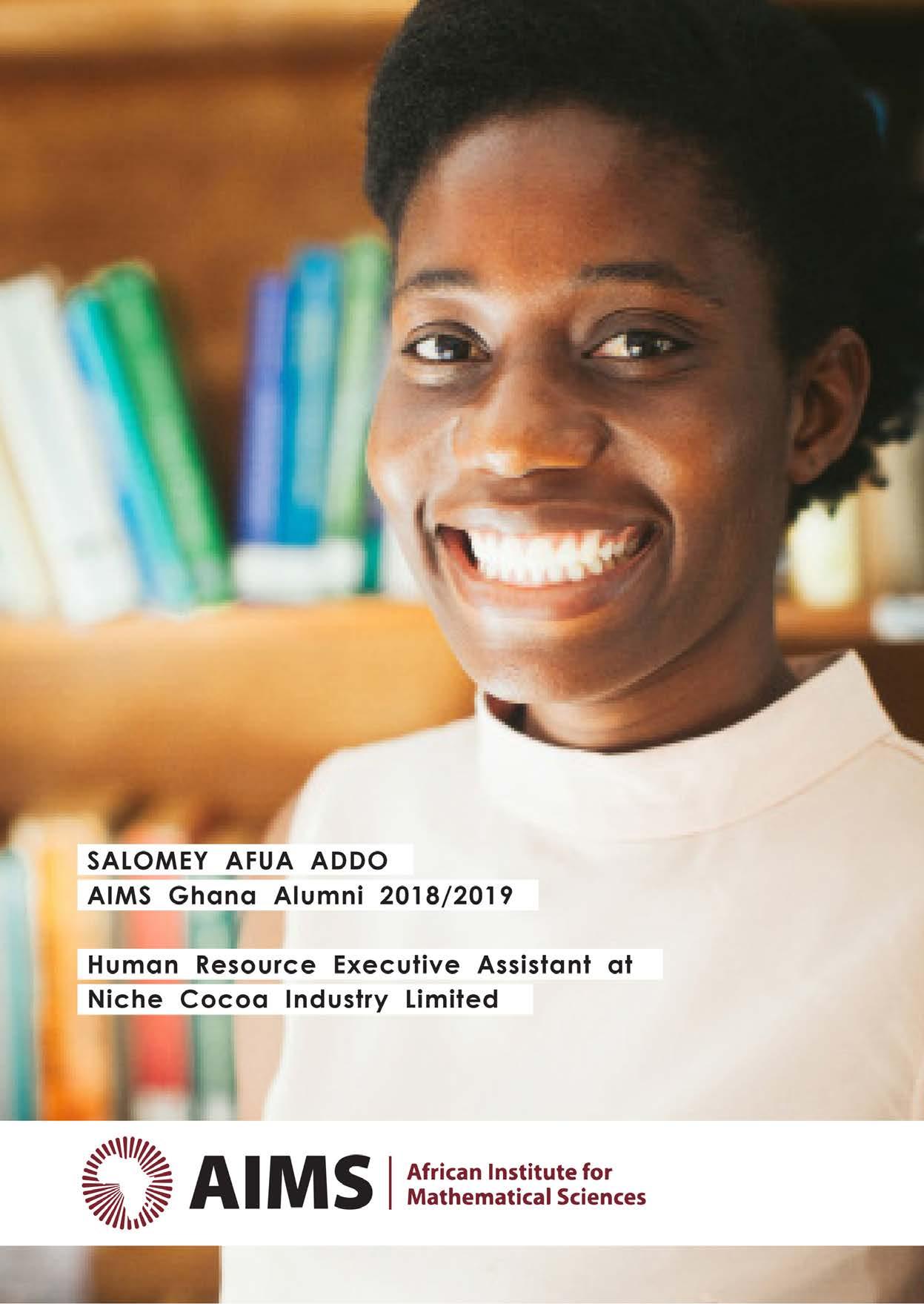

Moky Makura was born in Nigeria, educated in England and has lived in London, Johannesburg and Lagos. She has been a TV presenter, producer, author, publisher and a successful entrepreneur in her own right. She is currently the Executive Director of Africa No Filter, a donor collaborative focused on shifting the African narrative.

Moky started her media career as the African Anchor and field reporter for South Africa’s award-winning news and actuality show – Carte Blanche. She conceptualized, co-produced and presented a lifestyle TV series for the pan African pay TV channel MNet called “Living It”, which focused on the lifestyles of the African continent’s wealthy elite. She also played a lead role in the groundbreaking and popular MNet PanAfrican drama series Jacob’s Cross.

Her book Africa’s Greatest Entrepreneurs with a foreword written by Richard Branson, featured on the top 10 best-selling business books in South Africa when it launched. Moky has since compiled and published a number of non-fiction titles under her imprint MME Media. Titles include South Africa’s Greatest Entrepreneurs, Going Global which tells the stories of South Africa’s most successful global companies and a biography of one of its top entrepreneurs; Herman Mashaba, called Black Like You.

Moky started a fiction book series called Nollybooks aimed at getting young Africans to read, and then adapted the series for television co-producing over 21 television movies for the South African TV station etv.

COVER STORY 35 ISSUE 17 | 2023

Please introduce yourself to the TAP Fam

My real name is Olajumoke Makura, and I have the privilege of being the executive director of Africa No Filter.

For starters, can you please describe what Africa No Filter is to someone unfamiliar

So, the easiest way to understand what Africa No Filter does is that we are a narrative change organization. And that means we work with storytellers. We fund storytellers and we try to make the ecosystem for storytellers better and easier. Our definition of storytellers is somebody who has a way of telling their story, it doesn’t necessarily have to be written, it can be visual, it can be a film etc. that’s what we call a storyteller.

Thus, every project that comes, the question we ask ourselves as a team is how is this project changing the narrative? That means, if you like painting landscapes of the British countryside, we’re not going to fund you, we’re not the slightest bit interested in your work. So, we’re not for every storyteller, we’re not for every artist, we’re not for every media organization, we have a very specific type of organization and storyteller that we want to work with; those that want to change the African narrative.

Now back to you, how exactly did the name “Moky” come about?

Well, Moky is a completely madeup name! It is a nickname. The way it came about is, in Nigeria, most people called Olajumoke are

called Jumoke - but my brother and my family shortened it to Moke. Then, when I went to school in England, they couldn’t say Jumoke or Moke - I became JUMOKY! They called me Jumoky. I’d often hear “Jumoky this, Jumoky that” and I hated it so much so when I moved to London, I dropped the Ju and I became MOKY. And now, my family and everyone else calls me Moky. In fact, if I were to walk past you and you called out Jumoke, I wouldn’t even turn around because no one calls me Jumoke anymore.

What were some of your favorite memories growing up as a child in Nigeria

My favorite memory is growing up in Lagos with a gang of my friends riding my bicycle in our area, playing in a gutter trying to catch fish and frogs and climbing trees. It was so much fun just being kids playing outdoors in a way that kids aren’t doing today. We had open spaces in those days.

How did your career get started?

I went to school in the UK and when I left University, the first job I had was a sales job. I learned to sell, and I believe that is the most important skill I acquired because at some stage, you’ll need to sell something to somebody. A lot of young people say, “I don’t like selling, I’m not a salesperson”. No, you are, you are! So that’s the first great thing that I did. I then moved into public relations, PR communications. I already had a passion for writing, my father was a writer, so I was always a bit of a writer. And I was also an entrepreneur at heart. Because I’m unmanageable, it’s hard to manage me because I have ideas and things I want to do so I

started my own business.

After being in communications for a while I then went into publishing. I was publishing books and doing production. A full-on creative entrepreneur. In between that, I left the UK and moved to South Africa and that’s where things really took off.

At this point, did you already know what moved and inspired you?

It was once I moved to South Africa that I really figured this out; that the one thing that inspired and moved me was telling stories about us as Africans. From quite early on. I used to get annoyed by things such as “Live Aid”. The 1985 concert to save Africans. Most people might not remember that but just watching those images, as if every single African is poor, and that you know, just because you’re white, and you live in the Global North, you’re better than me, or that you could feel pity for me, it was an actual thing that moved me to do a lot of the things I’ve done.

I wrote a book called Africa’s Greatest Entrepreneurs because I was like, we have entrepreneurs too. I produced a series called “Living It”, which is about Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous in Africa. We have rich people, too. It was always like, no, we are not different, there’s no othering of us. So that’s been a strand through my career.

Would you say that the single most consistent strand of your career has been storytelling?

Yes, the single strand that pins all my work together is storytelling. And I’ve had the privilege of being on all sides of it. I’ve written

COVER STORY

books, I’ve published books, I’ve produced, I’ve acted in TV series, you know. Then I came to Africa No Filter and it’s like God gave me the job. If I’d put everything I do, and everything I hope to achieve into one job, it’s the role that I have now at Africa No Filter. I couldn’t have asked for it. I couldn’t have created it. It’s been an amazing journey to get here, but the thing about every journey is it’s only when you look back, that you realize that you’re always on the road towards it. I just thought I was doing this, doing that, but then I got here, and it all made sense.

I have always thought you were part of the founders of Africa No Filter.

No. Africa No Filter started off as a project of the Ford Foundation. They were looking for a project that all their offices in Africa could do, and the one thing that they all realized that they had in common was the fact that the stereotypes about Africa were a problem. So they came up with the concept; Africa No Filter. To support the development of nuanced stories that shift stereotypical and harmful narratives within and about Africa. But then they thought, why should we, as the Ford Foundation, be the only ones that fund this? Because other foundations, other philanthropies and really everybody is affected by

these stereotypes.

So, they went out and got funding and commitment from four other foundations to get in on the idea. Afterwards, they were like oh, we need to go and find somebody to run it. At the time I was doing work with the Gates Foundation when I saw the idea and I instantly loved it. I thought, you mean, somebody can pay me to do the work that I was already doing on my own. I applied for the job and got it.

we do. One, we do research. Two, we do grantmaking because we’re trying to build a community and four, we do a bit of advocacy; to be a bit of a watchdog around the African narrative. I will say, this is the best job ever.

In your head, what was the process of coming up with these pillars?

You start off with a vision that you need to actualize and bring to life. And not everybody in the world is good at taking an idea and making it into something. But that’s something that entrepreneurs naturally have because we always start off with a vision. In this case, it helped that I’d had this vision in my head for a long time, so it wasn’t brand new.

When you started, on your first day, what was the plan for Africa No Filter.

It was a case of here’s a piece of paper with what we think it could be, but you need to turn it into something. In the last two years, that’s what I’ve been doing, trying to figure out what is and how we can use it to change the narrative around our continent. We’ve come up with pillars around the things

On the day that I started, I was clear. First and foremost, I believe in evidence, so we were going to need and do research. I’m not a data person but if you tell me something, I want to know why, I want you to show me the evidence. So, I always knew I was going to do research. I also knew that we were lucky to have this money from European and American funders and that we needed to give it away. Thus, we were going to give out grants. The question became, who are we going to give grants out to?

Because we deal in narrative and we know that narrative evolves

37 ISSUE 17 | 2023

through stories told over time, I figured we need to work with storytellers. But then another question came up, who do we consider storytellers? We settled on people in the media and in the arts and culture space.

The other part about building a community, I knew that before African No Filter, I cared about narrative, and I knew I wasn’t the only one. So, I thought about how do we include people and organizations like TAP in this so that it’s more than one organization? It must be a bunch of organizations all pushing for the same thing. Then we had to find these organizations and people with a similar goal, then we had to support them in their work, that’s what we set out to do. In my mind, I was and I’m still very clear and very focused on what we must do.

What’s made it possible for you to have done so much in such a short time?

I have to say that the thing about Africa No filter is that we actually have money. We’re not a complete startup, we have funds to do the work we want to do. In the beginning, some of that money was given with the mindset of, let’s give this money to the Africans and let’s see what they do with it, you know! And the amazing thing is that this year, a lot of our funders’ terms came up because we only had an initial funding of two years, but they’ve all come back, and they’ve all come back with more money. And that really says to me that we’re doing more than they expected. Like we’ve given them a return on their investment. And I think that’s amazing. That’s the biggest affrmationtomethatmyfunders have come back with more money than they originally started with.

You spoke about doing research. What are some of the most interesting findings that you’ve uncovered?

We’ve learnt quite a lot of interesting things. For example, we did research on “How African media covers Africa” and it was eye opening; there’s this perception that we as Africans, we do all the right stuff. We don’t tell those horrible stories about ourselves, it’s always you know, the international media. What we found was the opposite. Research showed that in more than 80% of the stories Africans were reading about each other; In other words, I’m sitting in South Africa reading about Ghana, it was all negative! More than 80% of the time, it was stories about conflict, post electoral conflict and about humanitarian crises. There was no good news.

We also did a report on the narratives around doing business in Africa. Lots of interesting things. But one of the things that I found interesting was that the Africa continental Free Trade Agreement, probably the single biggest thing that can potentially happen to Africa, a one market for the whole continent to trade and do business with each other, was only covered in 1% of the business stories on Africa. If we as Africans are not writing about it, how will entrepreneurs know how to leverage this.

And the last one, I’ll tell you, a creativity report that we’ve recently published. We were polling creatives in Africa, we did it in nine countries, to understand how creatives feel about the creative industries? What struck me was that very few of them believed it was a viable sector for them to go into as a career.

COVER STORY

give out about a million dollars a year. And in Africa, it’s not a lot when you look at the scale of the challenge and the size of the continent. But you know, there are only a handful of organizations that can take huge grants, you know, some of the bigger people who fund us want to give away half a million dollars. But in doing that, you’re cutting out some of the emerging artists or just the younger people who are making stuff happen. So I like the space we’re in, I like this $500 to $25,000 although the most popular grant category is the $500 to

39 ISSUE 17 | 2023

$2,000 mark. In the market we’re in, people are putting a lot of stuff together for that amount of money. That’s the one that we get the most applications for.

What are the 3 most exciting ideas/projects that you’ve funded so far?

One of the most exciting projects we’re doing now is this virtual reality augmented reality project, we’re working on with Meta.

But as you know, we have over 150 grantees, and we’ve done as little things as helping somebody develop their own album, some advocacy, some film, and media projects. We’ve done a lot of things. So, it’s like asking your mother, who’s your favorite child? Um, you can’t really answer that in public.

But I’ll tell you, the kind of projects that I like, it’s the people behind them, because you really can fund an idea, but you really fund the person behind it. You know, I’ve just seen several different grantees that we have here in Kenya, and I’m just blown away by the work they’re doing.

What does the next few years hold for Africa No Filter?

You know, one of the things that you need to understand if you want to create change is that change doesn’t come overnight, it takes time. And narrative change particularly, doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time. But we know that you can change the narrative, one story at a time. Over the next three years, I want to see more of what we already do. I want to see more stories. I want to see more grantees coming in. I want to see more research. I want to see more kinds of watchdog initiatives and more things that say that hold on, you can’t speak to us like that, that is not okay for you to tell a story like that. We’ve only been here for two years, you know, strong brands are built over time. We’re standing on four very strong pillars, and we’ll continue those pillars. Research, grant making, community building and advocacy. We will push on with our pillars, how we do what we do may change but our pillars will

stay strong.

What are you most excited for? What is the future of African creativity?

You know, from where I sit right now, we are often approached by a lot of organizations saying they want to work with creatives, they want to work with African creatives. So, I think right now, there’s never been a better moment to be a creative on the continent, because it’s like the world is thinking, oh, we need to do something different. And what we’ve been trying to do is channel some of that funding into the creative sector in Africa.

So, for me if you’re an African creative today, put your hand up and work. Because there’s opportunity out there for you. There are people who want to fund you, Africa is the next big market. And it’s been for a while. But, right now, I’ve never seen as much attention on the African creative space, ever. And we have reports, there’s numbers, figures, of what it’s supposed to be worth and of how many people it can employ, so yeah, now is the time.

On a personal level, in these two years that you’ve been busy building this platform, what are the two things that you’ve learnt about yourself?

Something I’ve learned in the last two years about myself is that if you’re in the right situation, you will thrive. And you will be better than you ever thought you would. What I mean is, I was in a role that was great. And I always use the example that I was in a tight jumpsuit. I was a bit restricted, but I thought it was okay. I thought, well, you know, I’m only supposed to move my arms this wide. And I’m not

COVER STORY

supposed to take two big steps. Until I got to Africa No Filter, and I realized, oh my god, I’m a size 12, I’m a size 14. Here, I thought that I could move, and I could do things because I was in the right environment for me.

A lot of the time we tolerate the wrong situations because we’re scared that we’re going to lose our job or because it is what our parents want of us. Something I believe in that was reinforced in the last two years is that if you do things out of fear, you’ll end up miserable or having half the life. Whereas if you do things out of love; you’ll be alright. And the universe has a way of looking after you and I really believe that. Even if Africa No Filter stopped today for me, I know that I’m going on to something else. I’m going on to it and maybe I thought I was a size 12 here and I’m actually a size 18 When I go to my next job. I’m in an even bigger space. Just walk in confidence and walk with the knowledge that you’re doing the right thing and everything else will happen.

What are the three African narratives or stereotypes that you’d like to smash?

One, that Africa is broken, because everybody is trying to fix us. The second is that Africans are dependent because everybody is rushing to try and give us money to fix the problems, they think we have. And the third one is that Africans lack the urgency to make the change that they see themselves. I don’t believe any of this one bit. I think Africans do have urgency. You can see it everywhere. I feel that we are not dependent. We have the resources at hand to fix our issues. And the fact that Africa is broken. Are we now sitting in a broken place? No! There should be a multiplicity of

narratives so that these narratives aren’t the ones that immediately come to mind when you think about Africa. And I’ll give you a quick example, I was on a train in Germany and a random businessman from Norway was on this train with me. And he’s talking to me and is fascinated about what I do. And I said to him, when I say Africa to you, what do you think? His eyes started getting shifty. He didn’t want to tell me. I said, what are the first words that come to your mind? He was like hmm hmm. I said, “It’s okay, just say it. He said, well, I think a lot about poverty and starving people. That is his image of Africa. That is not what I think of when I think about Africa. There are many, many things going on in Africa but that was literally the only thing he could tell me.

This poverty narrative is so strong, and it’s so inaccurate. We’re not that single story. We are more! There is poverty, yes, but that’s not a full picture of who we are, that doesn’t define us. So yeah, those are the narratives I need to change.

What is the one thing about Moky that people do not know?

Hmm, here’s something that not a lot of people know about me. I’m not a big music fan. I don’t know anything about music at all. I used to listen to talk radio and then podcasts came along and I started listening to podcasts. So yeah, I’m not a great music person.

What are the top 3 podcasts that you’re currently listening to?

Ohm tough question, I love listening to stories so it’s tough to pick but I’d say; Snap Judgement,

it’s about random American stories and I really love them. I also listen to Adele Onyango’s podcast, Legally Clueless and I have to say, one of my favorites, which is also one of the oldest podcasts, is This American Life. My ambition is to have my own version of “This American Life”. This is a complete exclusive. I’ve never said it out loud before. I want to do This African Life, a storytelling podcast around just things that happen on the continent.

What keeps you going and motivated in this work?

Meeting the people that we’ve supported keeps me going and motivated. I met someone today who said over COVID If they didn’t receive our funding, they would have closed down. These types of conversations move me. The fact that we’re able to make a difference in a little way, really keeps me going. And the fact that I am really driven by our mission to shift narrative and just change the way the world sees us as Africans. I know our funders think that we do a lot, and we do, but I feel a sense of urgency that we need to do even more. This also keeps me going. I don’t want to look back and say but I didn’t do that. I don’t want to have regrets.

What would you like your legacy to be?

I would like my legacy to be that she was consistent in her passion for shifting how the world sees Africa.

41 ISSUE 17 | 2023

Interview by | Ras Mutabaruka Images by | Stephanie Matu Outfit by | Moky Makura Shoes | Enda Sportswear

Designed with Kenyan athletes, For runners everywhere. WE MOVe -

endasportswear.com 43 ISSUE 17 | 2023

WHEN IT COMES TO MUSIC, MOOZY GOT NEXT

On our recent trip to Gaborone, Botswana, we met a young musician who has captured the country’s attention and psych.

Jordan Moozy is a multi-talented singer songwriter, born in Botswana but of Zimbabwean origin.

While still new to the business, only having released his debut EP De’Grace end of last year, Jordan Moozy lacks no talent, commitment, or ambition. He has the TAP Magazine co-sign and we’re yet to be wrong on a musician we’ve endorsed. So go ahead and find him on your favorite streaming platform or on YouTube while you familiarize yourself with his backstory. It is only a matter of time before you hear him on your local radio, or his tour bus shows up to a city near you

45 ISSUE 17 | 2023

My name is Emmanuel Jordan Muzenda but I go by Jordan Moozy. I’m a singer and songwriter currently based here in Gaborone.

My mom gave me the name Jordan because she’s deep in her faith. A strong Christian woman. She was saying, God, be with us, we are crossing over, you know, the Jordan River. My parents and my family are from Zimbabwe, but I was born in Botswana. I dropped out of high school in form four to pursue music, and it was hectic. At the time, my parents had financial difficulties and it was either my sister continued with school, or I did, and I volunteered. I said let my sister finish school and I’ll figure my life out. At the time, I was already obsessed with being a rapper.

You started out as a rapper, were you any good?

Yes, I am a very good rapper… (Laughs)

What were those early days starting out like?

It was a very difficult time in my career because I barely knew anyone. You find yourself in a position where everything that every person says sounds like wow, and you’re just going for it. But it was also a good learning process, you start small, and it’s humbling.

Back then, I remember recording with a few people at the start, and that wasn’t so great. None of the music from those days ever came out. Something about me, I’ve always wanted the top quality of everything. I’m a person who values high standards when it comes to my art and I didn’t want to give people a reason to feel like, hey, he didn’t do this to his fullest capability.

When did you know you were ready to release material that you liked?

For a long period of time, I was going from here to there meeting people and doing small gigs here and there and people started to notice me and would invite me to come and collaborate, but I never did anything solid until a friend of mine who at the time was building a record label called the Douzy Brand and we started working together although he was more like a mentor in terms of my music. He refined my talent. Then there was an audition for a radio drama that wanted singers and actors to play. I went and did that, then I got a call back and they said, you know, your voice is what sold you. Once there, I met a man named Tefo Paya who also took me under his wing, and he just plugged me to a whole different world that I had no knowledge of musically.

Sounds like you’ve had solid people behind you.

Yes, I’ve been very lucky. For example, before I met Tefo Paya, I used to be shy and a very timid person. I couldn’t sing in front of people. He would always encourage me to believe in myself and to believe in my talent. Before I knew it, I was in spaces that kind of forced me out of that timid place that I was in. When you’re finally in front of people, you have

no choice but to sing. You can’t go in front of people and freeze. Yeah, that would be hectic! So, I did a lot of those and grew. Then there was also a friend of mine, Dato Seiko, she was better musically than me and she also supported and pushed me and put me in spaces where people could see me sing.

I used to play guitar for her at first and then we eventually started singing together. We still sing together. Even today we’ve got a band that we play in called WHAT! Yeah, it’s an awkward name! From there I started doing these small gigs and festivals and building a brand and a name and getting people to become familiar with me.

When did you break out on your own or when did you go out there and perform by yourself?

2018 is when I took a serious leap in terms of my career. It’s when I had my first one man show at Botswana Craft. I had 300 people come in with no music out of my own, from just doing open mics and gigs here and there. It was great even though I didn’t think that was my best performance. I was scared, because I suffer from

social anxiety; I still managed to get through it and people enjoyed the performance but I could have done better.

2018 is also the year when I started recording as well. I remember the first single I did was with an artist called Berry Bone and we did a song called “Need to Know”. I also did something with a deejay called Tumie BlackAce, uh, that was good. We touched number one on the local charts on Yarona Fm. Up until this point, I hadn’t put out anything of my own yet because I was at a point where I was still trying to figure out what my sound was. So, the following year I put up another single “Banyana Ke Maaka” with Veezo View. He’s a very talented rapper, one of the world’s best.

What inspired Jordan Moozy’s first song?

{Laughs} When I was writing the song, at the time, I was hurt by a girl and the way I like to write music, I write music from the perspective of when a person listens to it, I try and envision how it’s going to make them feel. And in this particular song, I was talking about the ego and how, you know, you try to protect yourself and carry yourself in a particular way in life and you never want anybody to ever catch you ‘sleeping’ but the one minute that you do actually let somebody in, they take you from your high place and show you that you’re only human at the end of the day. I wouldn’t say it was a toxic song, but like it was really just a song to say no matter what you do, I will still be the same guy.

That song got me my first nomination for an award. I was nominated for best newcomer and best R&B. It was good to see, in as much as you can feel that your music is great, it is good to

47 ISSUE 17 | 2023

see how other people react to it. That year, I’d also go on to work on a collaboration with FlyBoi Que and Luther October and we won an award for best collaboration for our song Ndeya which stayed on the charts for three months. I remember we received a plaque because we were on the chat for the longest time in Botswana. Hard work was finally starting to pay off.

Did you always want to be an artist?