ARCHITECTURE PORTFOLIO

SELECTED WORKS

2019-2024

Tanuja Vartak

Tanuja Vartak

2019-2024

Tanuja Vartak

Tanuja Vartak

Email Address: tanuja.vartak12@gmail.com

Contact No: 7030963133

Address: Manik Nagar,Gangapur road, Nashik, India

Education

2006-2017: Ashoka Universal School Grade 1-10 (Nashik)

2017-2019: HPT Arts and RYK Science College 11th-12th (Nashik)

2019-2024: School of Environment and Architecture (SEA),Borivali West, Mumbai

Winner of Urban scripts Essay Writing competition 2023 (ArchitectureLive!)

Winner of Avani Essay Prize 2023-24 (Avani Institute of Design, Calicut) To be Published in JIIA June 2024 edition

SEA Newsletter 2019 (SEA Press)

Rhythms, Forces and Energies (SEA Press)

Languages

English Hindi Marathi

French (Basic)

Member of the Content Committee (2019-2024)

Contributed to the SEA annual exhibition 2021

Covid Glossary 2021

Fabulations- a 10 year retrospective exhibition of SEA

2019:

Material Workshop- working with Ferrocement (part of Semester 2 Technology Module)

2020:

Visual Storytelling / Sunil Thakkar

Idiosyncrasies of Home spaces/ Komal Gopwani

Drawing Nature, Science & Illustration/Online course offered by EdX

2021:

Creative Writing / Snehal Vadher

Housing in India’s second cities /Shreyank Khemalapure

Marketecture / Devashish Guruji

2022:

Identity and Storytelling through Illustrations / Sadhna Prasad

The Bricoleur : Bricolage as method /Rupali Gupte

What the Folly! / Lorenzo Fernandes

2023:

Living in a metaphor / Anuj Daga

Archiving /Arpita Singh

Work experience

Internship I PYHT (Put Your Hands Together) Bio-architects Nov 2022-April 2023

Teaching Assistant Orientation Course I School of environment and architecture 2023

On-going Research Grant with The Heritage Projectsupported by RPG Foundation 2024

Skills

Fieldwork

Writing

Autocad

Photoshop

InDesign

Sketchup

Rhino

Illustrator

Interests

Writing

Painting

Watching Sunsets

Reading Fiction

C O N T E N T S

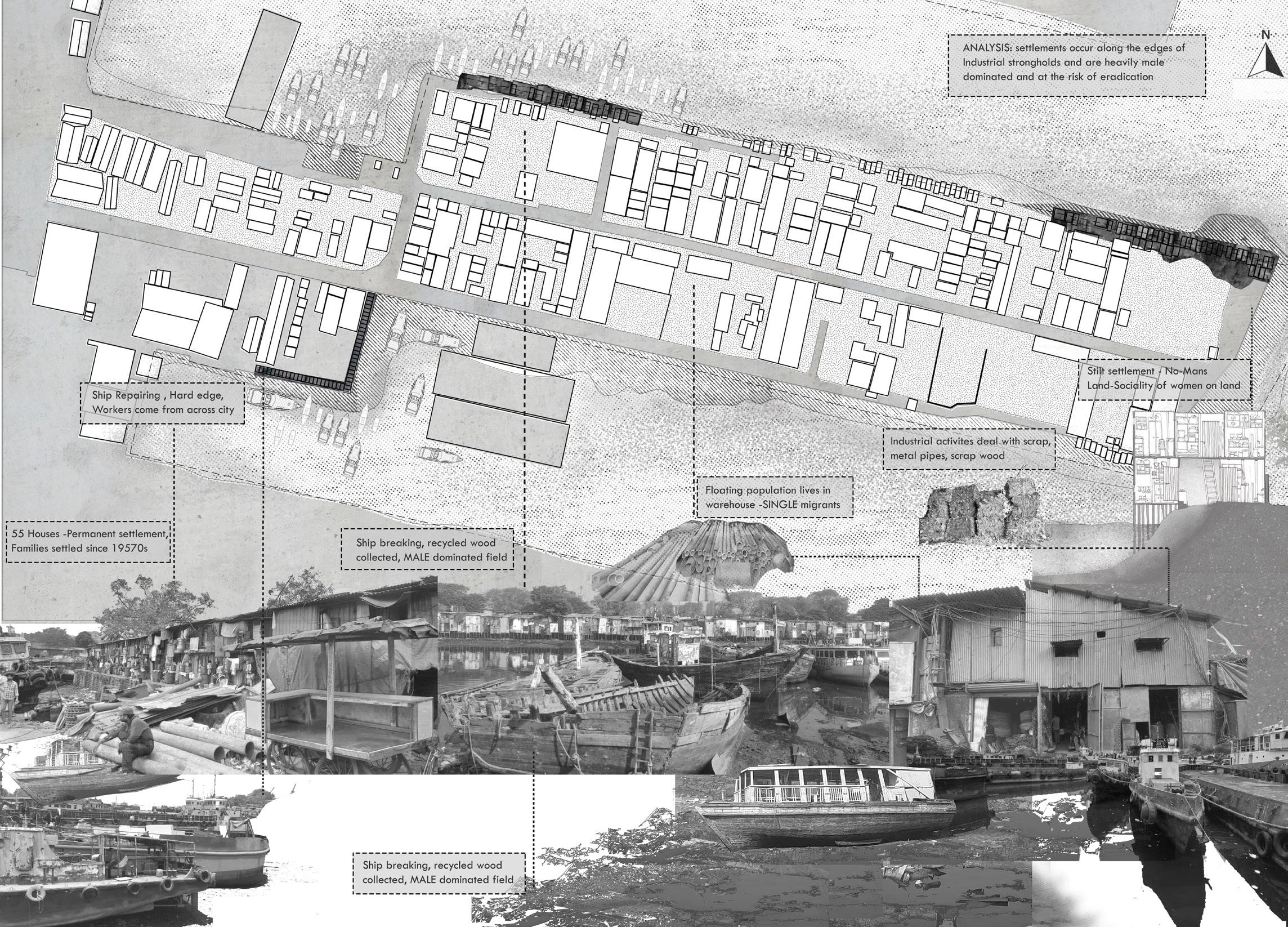

How did the shift of a large commercial port affect the lives of the dwellers? What are the spatial practices of inhabitation and relationships formed in the context of an uncertain edge? And thus what is the nature of urban life produced in a former portland?

I began my thesis by asking these questions in order to document the stories of people who have migrated to the docklands in expectations of a better livelihood and narrate the stories of their practices of inhabitation. The research is situated in the context of Kolsa Bunder in Darukhana , Mumbai which is a part of the Eastern Waterfront. The Eastern Waterfront of Mumbai under the Bombay Port Trust occupies 1/8th of the land area of Mumbai and from its establishment was a primary factor in the emergence of Mumbai as the commercial capital of the country. The shifting of the port from the island city to a region across the harbour owing to infrastructure and contextual issues left behind a space that remains like a remnant of the port.

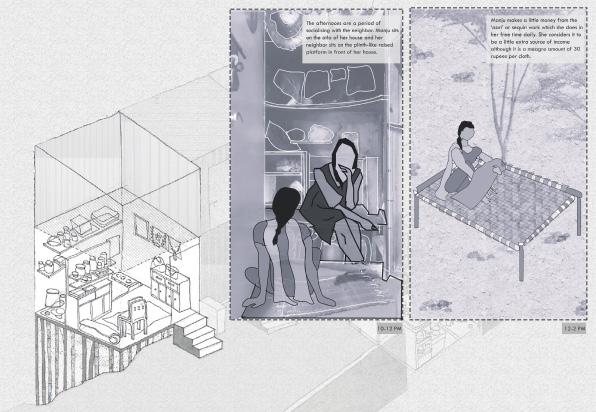

Ethnography enables you to temporarily become a member of the community and engage with their everyday and thus allows you to read a space. The findings from ethnographic stories suggest that inhabitation on the bunder happens through interdependencies of people on space and this creates complex spatial experiences that are specific to the context of the port. Analysing all the stories, I arrive at a finding that temporality exists in various forms as a spatial response to the uncertain context. The nature of space and its inhabitation change with time - in some cases the shifts occur through decades (influenced by law and order) while in others they are diurnal (influenced by migratory practices) and in some more- short term changes that are based on routines (influenced by the context).

Thesis Dissertation, Semester 9 and 10

Thus I arrive at the argument that spatial planning requires a lens of understanding of the people and the spaces they occupy and I suggest ethnography as a method to look at space apart from simply a cartographic or statistical study.

Kolsa Bunder is a reclaimed landmass of the Eastern Waterfront that projects out into the water which was once an active jetty. It is the central one of the three bunders namely Kaula Bunder (now New Tank Bunder), Kolsa Bunder and Lakdi Bunder each named after the primary goods that were once shipped from these jetties. Once an active segment with ship breaking, repairing and docking activities ; it now lies almost like a remnant of an era gone by, albeit with activities that still secondarily contribute to the economy. The land curves inwards at a point and forms an edge that is neither land- nor water.

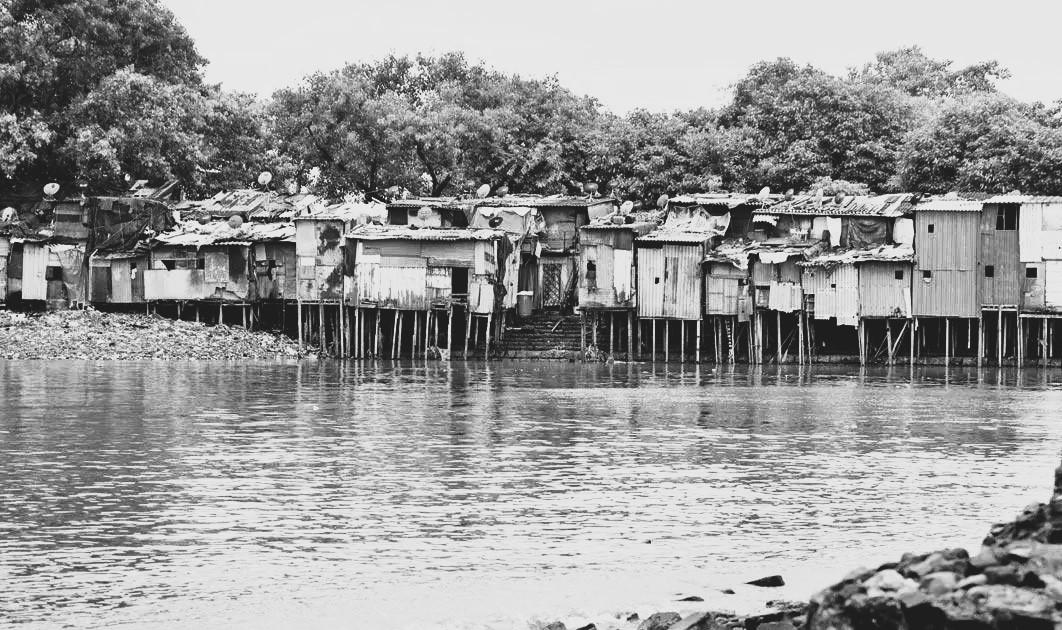

The settlement here navigates the edge of the land and water and narrates a temporality of inhabitation and form where its permanence is most uncertain , owing to the unpredictability of the edge. Where the boundary wall of the Port trust land ends and the siltation and water starts, I refer to this part as the no mans land.

Life on the edge, or No-Mans -land

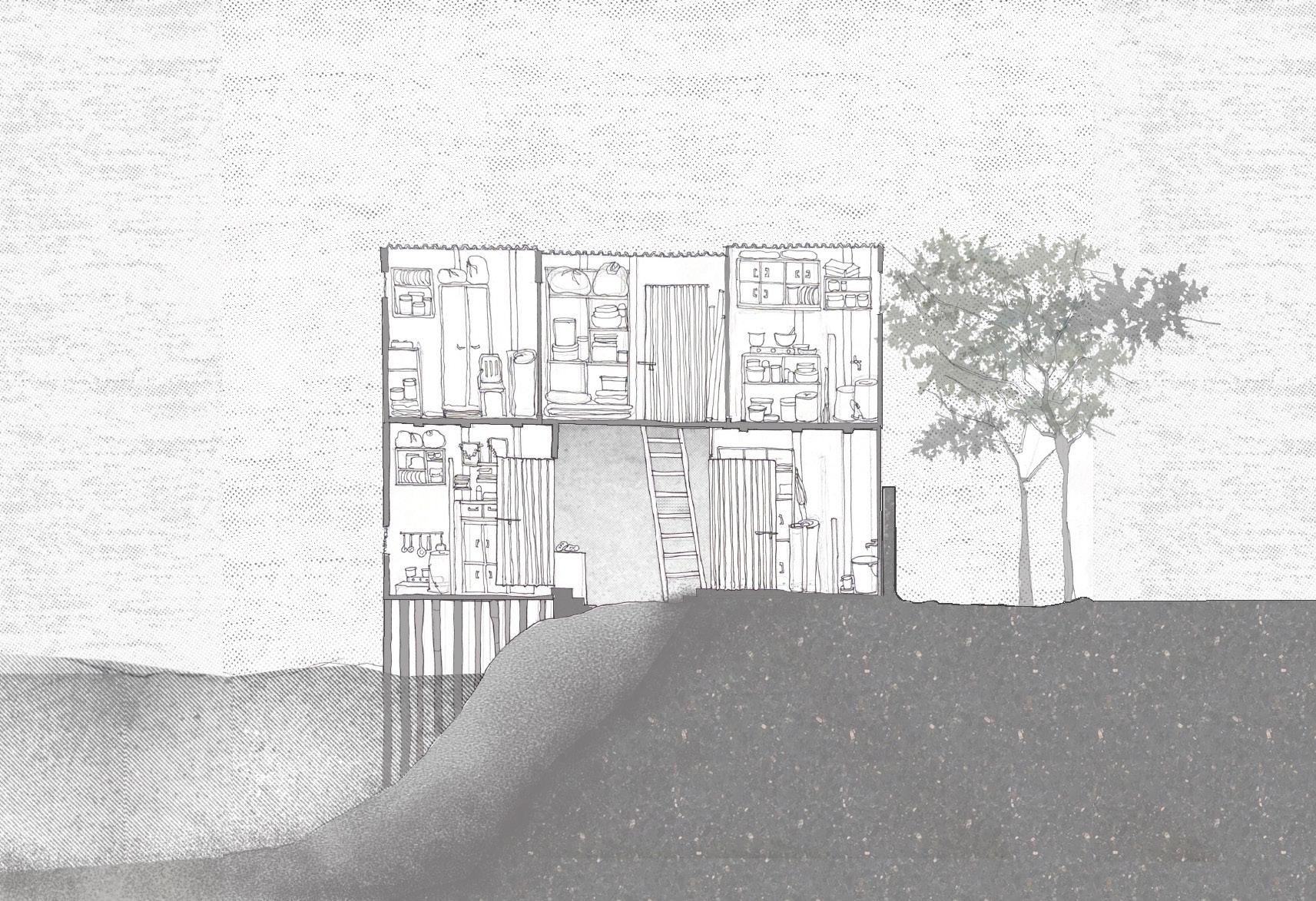

Manju didi sits on a khaat, she is bent over a pink cloth doing aari work- sticking the sequins one by one on the skirt. One of the women in the community gets the order for such multiple cloths to be detailed and a few girls and women are seen seated on the multiple khaats in the open ground, bent over various coloured cloths working. Didi takes up this work during the day once all the household chores are done.She earns thirty rupees per cloth and one cloth can take up a full day to complete. She says that this is one work that can keep her engaged during the day as her children are also grown up so she has no one to take care of and her husband does not let her work. Manju Kumar got married when she was 12 and moved to Kolsa Bunder twenty-five years ago. She has three children- two sons and a daughter all under the age of eighteen. Her husband works in the scrap dealing business in one of the warehouses in Kolsa Bunder itself. She starts her day at 6am by preparing food and pooja path and this process of cooking and cleaning takes up a good 3 hours of her morning. Two walls are lined with shelves that hold utensils and a large storage unit- lines the partition wall of the room and the mohri which contains most of the belongings of the family. The kitchen here is not a high platform but almost at floor level and merges with the mohri or washing area.One small low window in the corner of the mohri shows the water beyond. This is a house built entirely on stilts with only the entry to the house being on land. A metal ladder from the outside of the house leads me to a level above to a house that is mostly empty except for a few blankets and some storage.The home extends beyond the four walls and spills out into the dinghy corridor. Empty oil cans lie beneath a seating created out of plywood. Women are seen inhabiting these seats during the day and gossiping once their daily chores are over. She has kept a small shelf on this ‘otla’ and a few pictures of deities are stuck on this exterior wall in front of the house as well.

:

The site is a rough landscape of stark heavy metal and dust. It consists of large masses of warehouse sheds situated close to each other forming awkward gaps and allies and the informal housing exists on the very edge with a direct drop into the silt below. The jetty was analysed on the basis of activities such as ship breaking and ship repairing and the site being a mixed type consists of warehouses, workshops, informal housing and sociality.

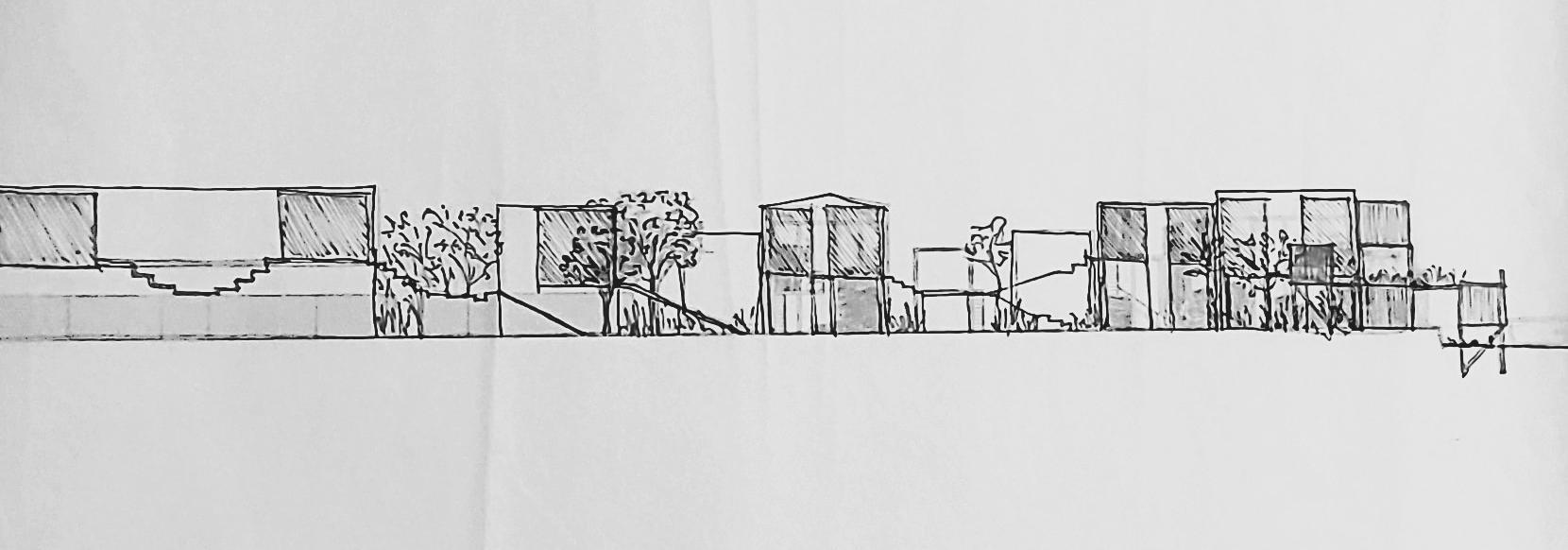

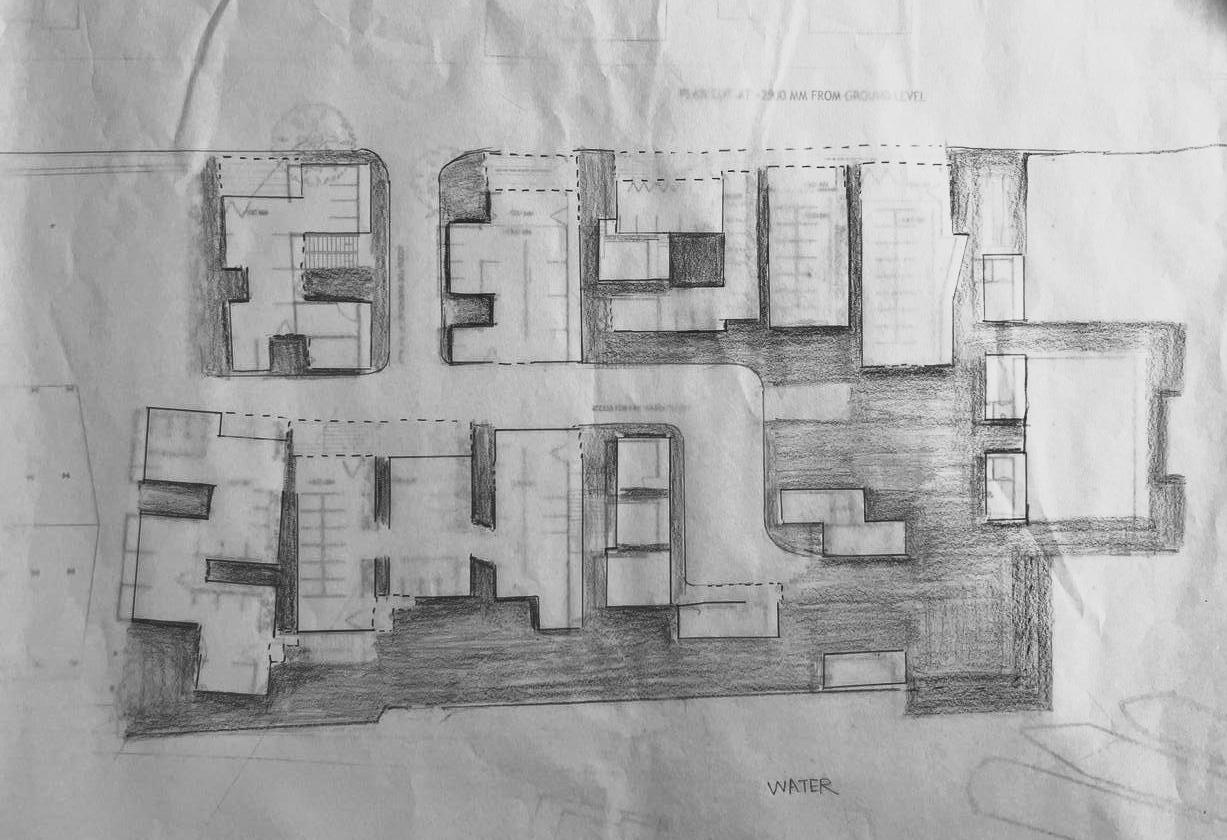

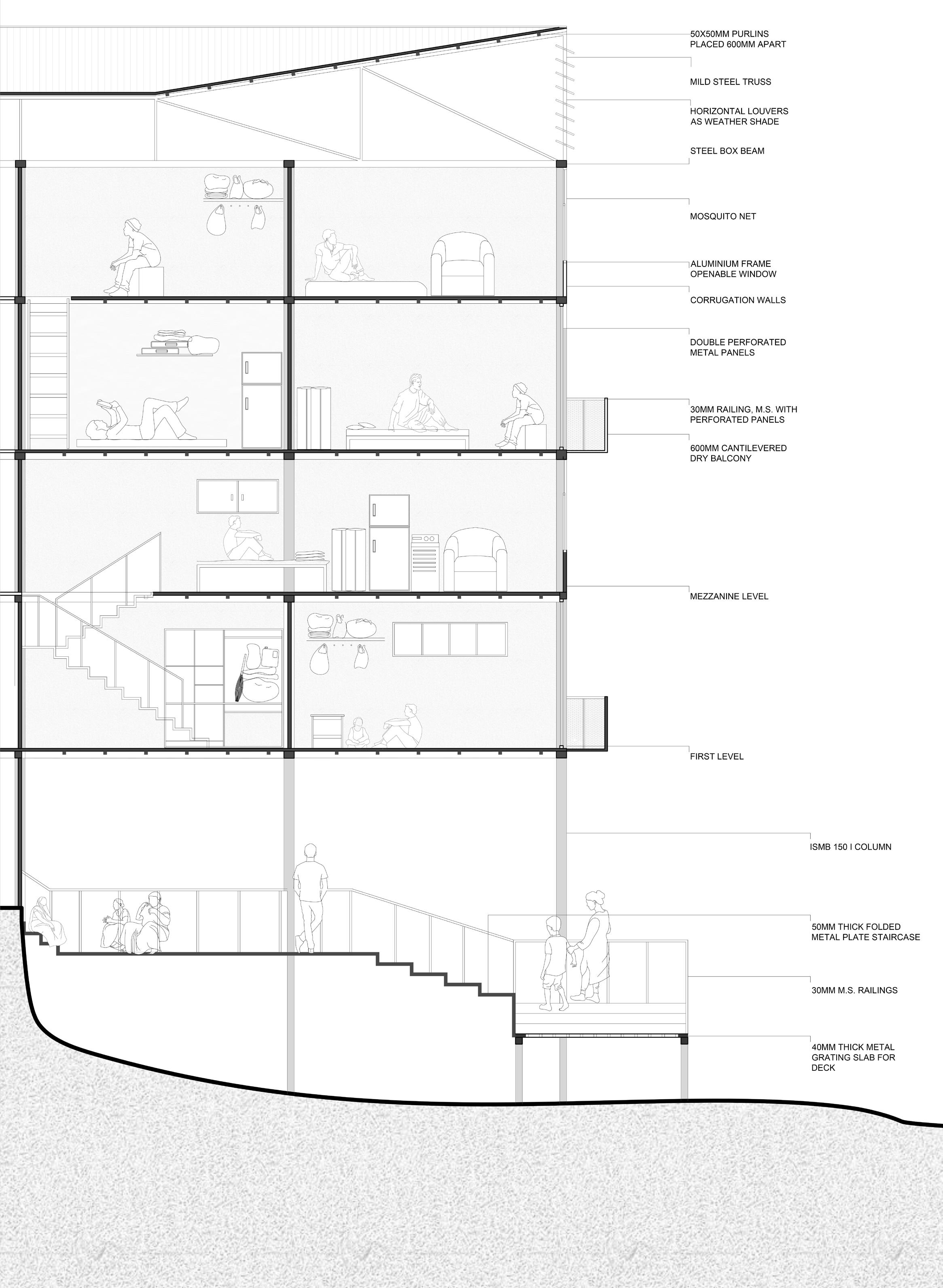

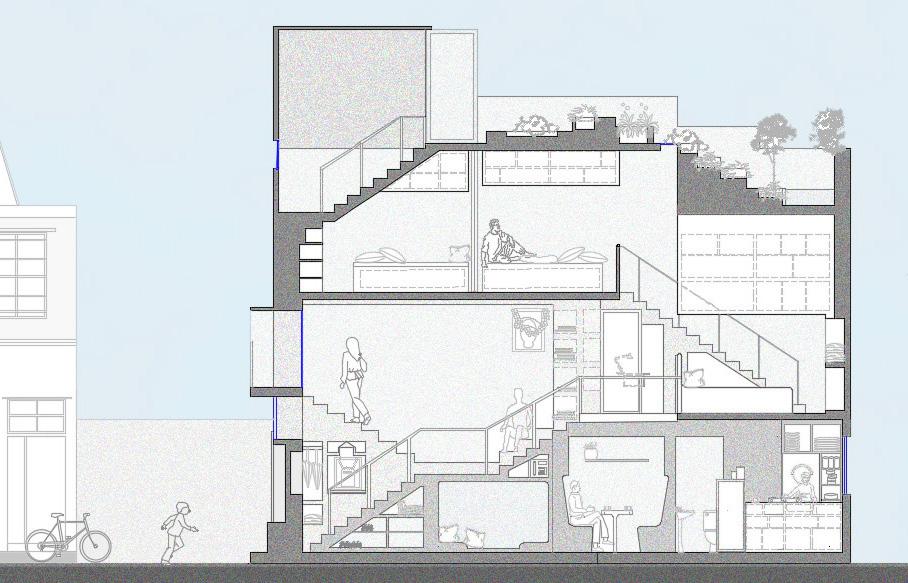

Experimenting through the section- to achieve vertical play of volumes within an existing form, planning the open spaces- what can they afford?

Cutting through volumes of warehouses and introducing pockets of commons (shaded areas). To facilitate a porosity between each warehouse- for better light, ventilation etc.

By raising the settlement on stilts, freeing up ground space for a porous sociality and opening every three units into a courtyard which serves as the space of expansion

By raising the settlement on stilts, freeing up ground space for a porous sociality and opening every three units into a courtyard which serves as the space of expansion

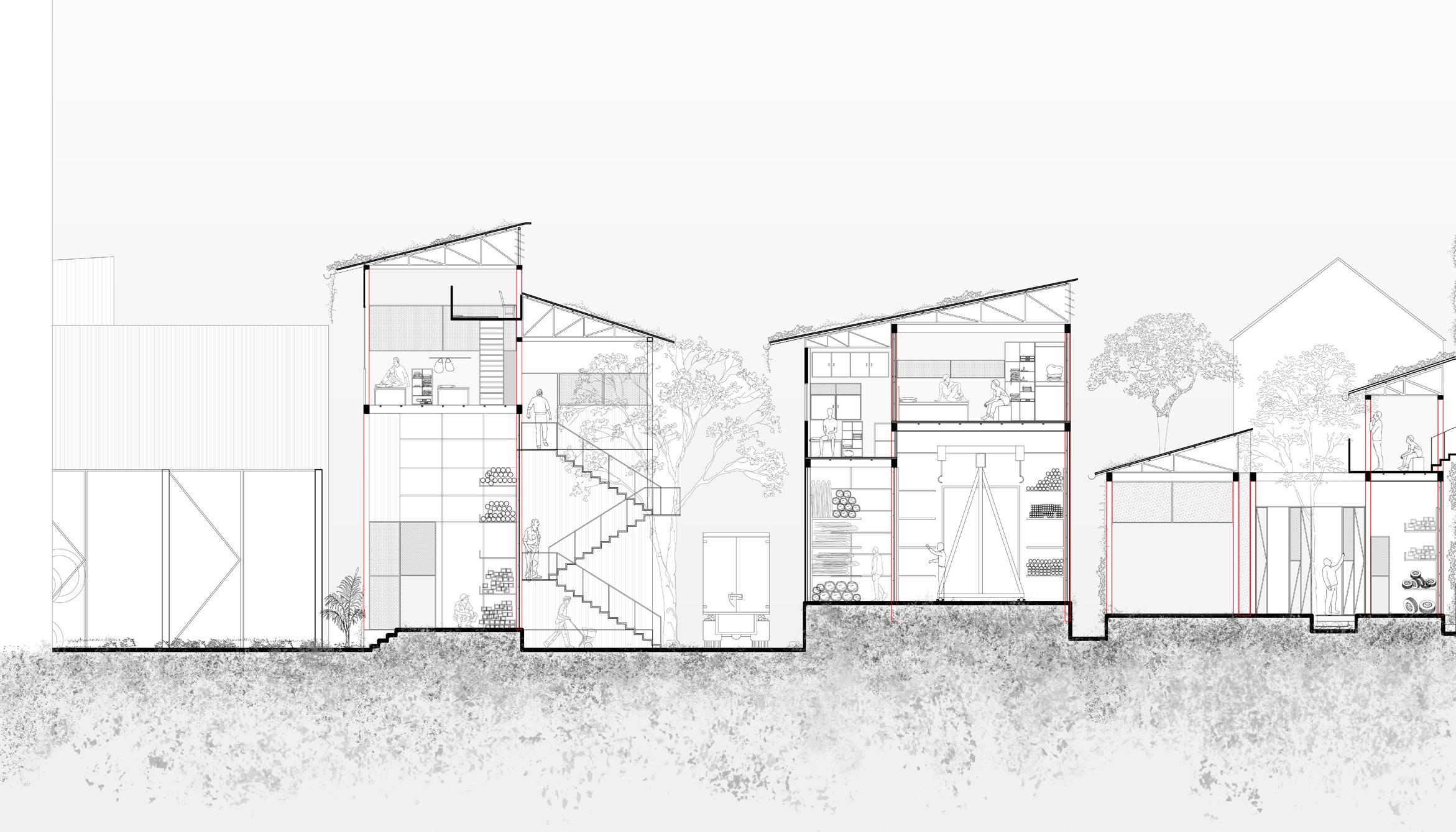

(L>R) Section through warehouses showing the housing insert on upper levels, while the lower part accomodates the usual industrial functions of the jetty

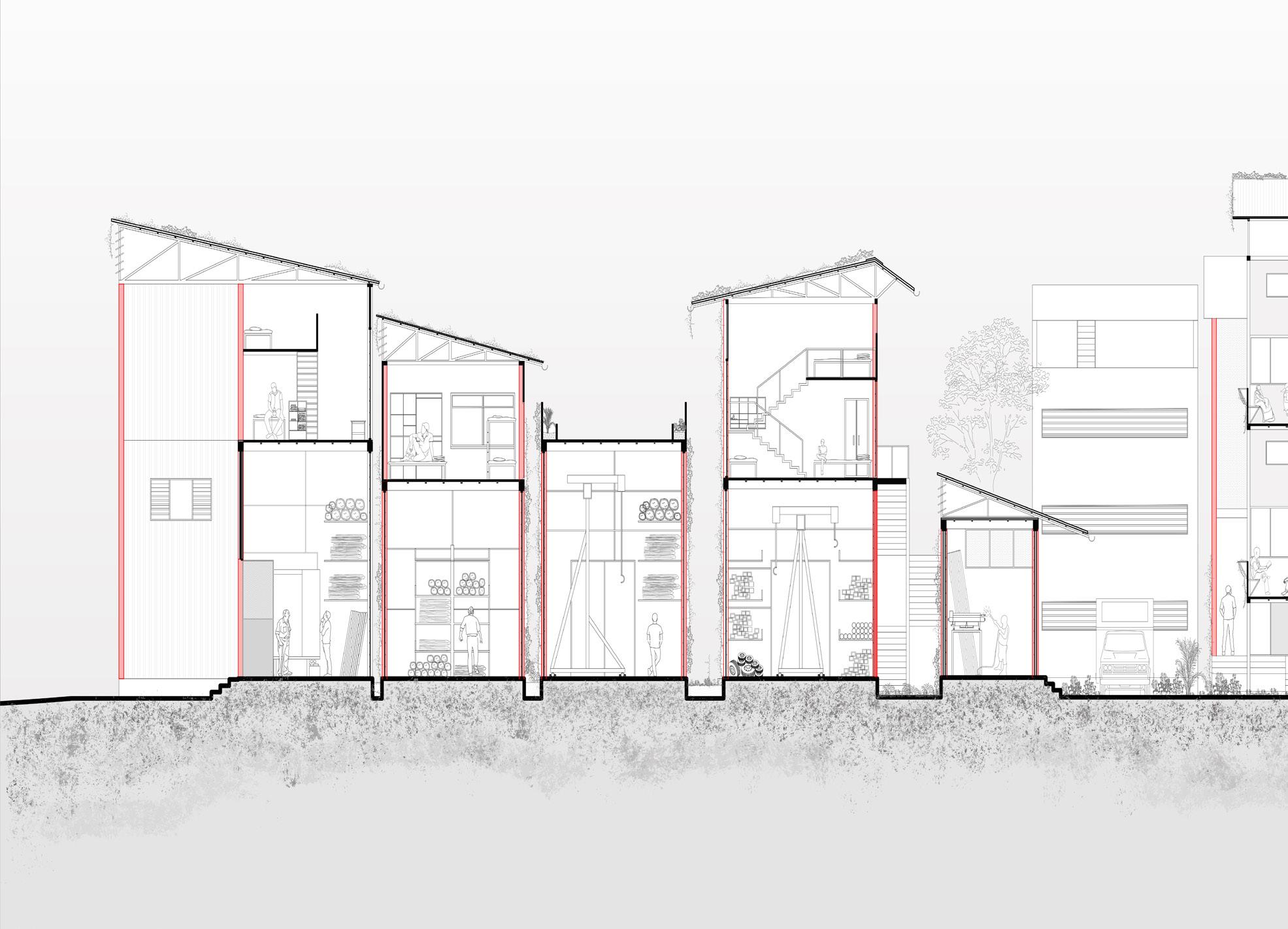

(L>R) Section through warehouses cuts through the rear, and mainly through the re-imagined housing for dwellers on the edge of the bunder

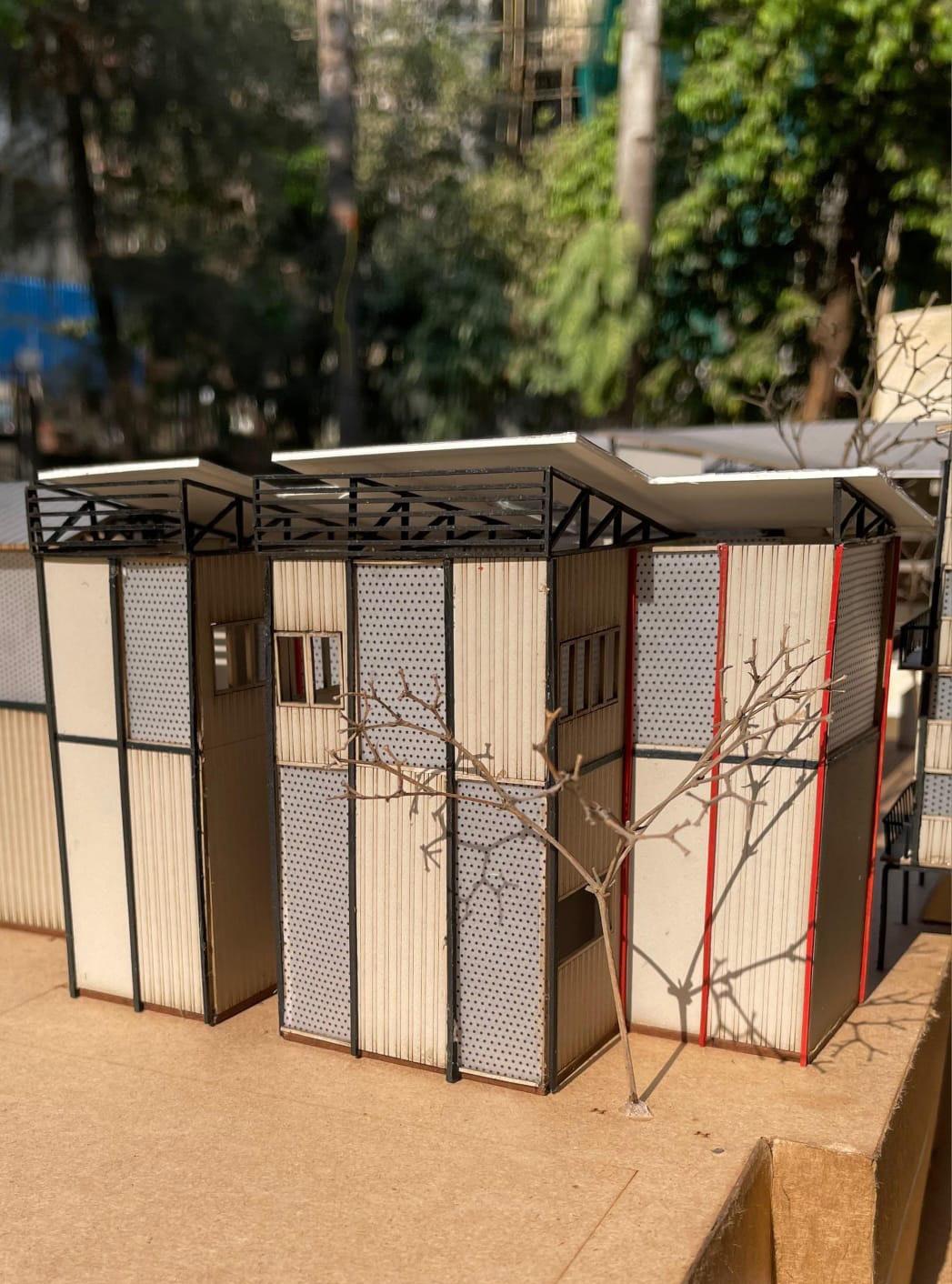

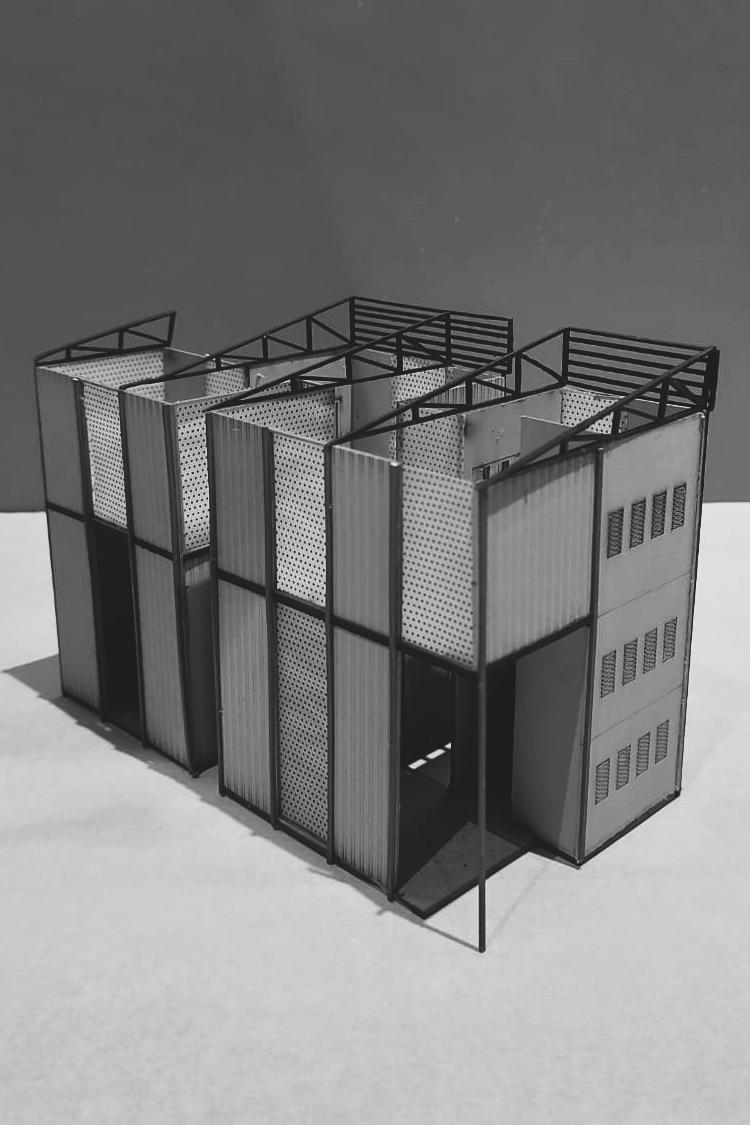

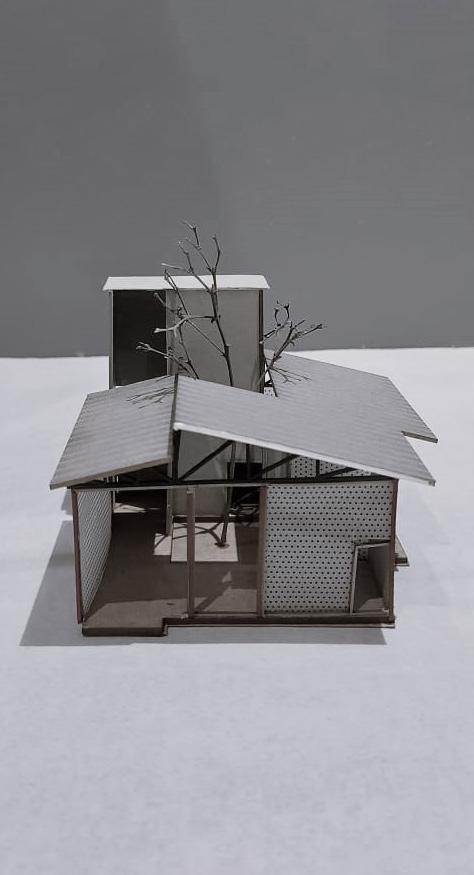

The materiality is imagined to be light and flexible since the housing for dwellers is on stilts extending into the water- existing I sections on site can be utilised and the walls are corrugation panels , while the wall that opens into the courtyard is magined to have wide foldable polycarbonate doors.

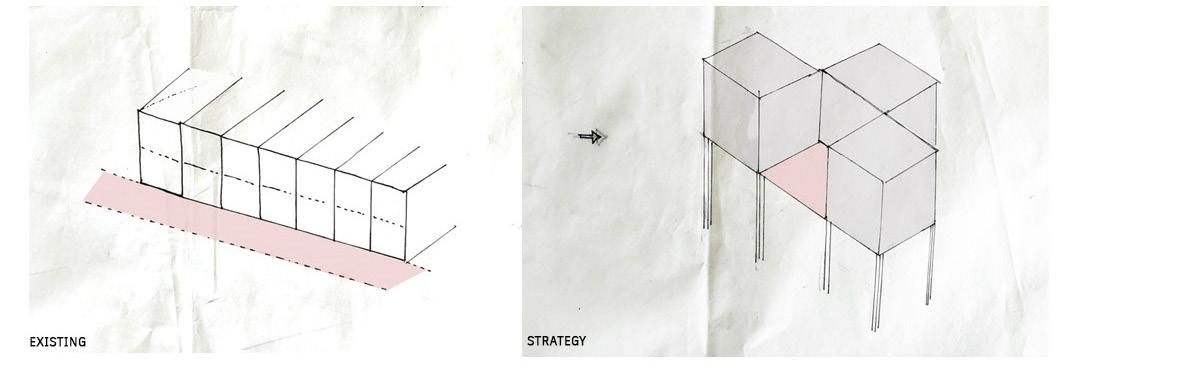

A home constructed on the water, with whatever raw material one can gather from the site, acts as a testament and an act of defiance against the urban policies and regulations of the state. This becomes a form of knowledge to learn and appropriate from, in order to propose a strategy, a form or eventually a way of life. This strategy is then deployed to change the ‘type’ of the warehouse as well.

Learning from existing methods of Home-Making as way of survival

The settlements that exist on the edge of the Bunder extend out into the water over stilts- makeshift timber or bamboo poles under tin walls and a tin roof, often going two storeys tall. Survival is the motivating factor for building over water where insecurity of demolition and resttlement is paramount.

Space for oneself is created by using the simplest technologies of putting together material and generating a bounded-ness to call it home. The design reflects these existing techniques of stacking, raising and creating a sociality around each dwelling.

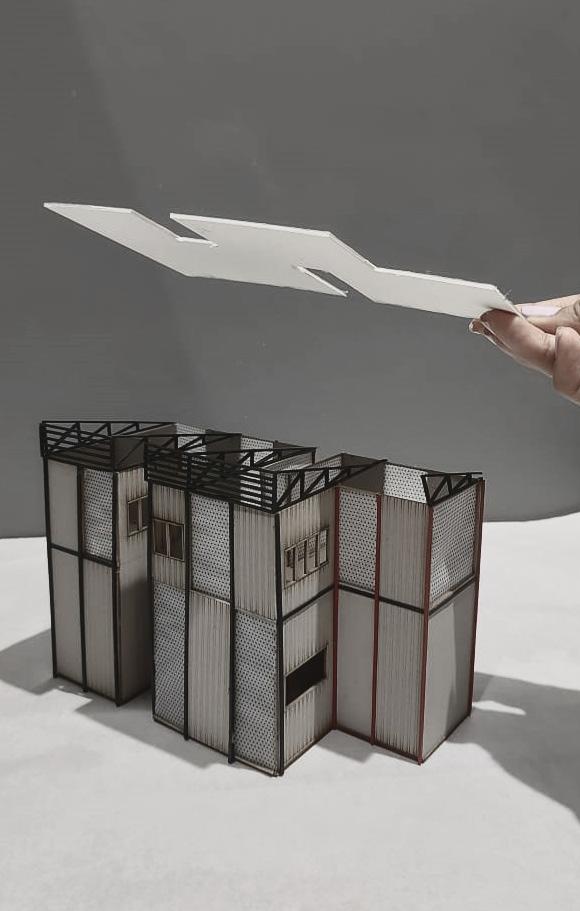

The role of an architect on a site like Kolsa Bunder is to intervene in ways that dignifies the current living conditions and the design proposes subtle architectural patterns to achieve an experience of a stable, moresecured living for dwellers. The type of the warehouse is re-configured (as shown in models below) through the strategy of RETROFITTING the vertical height with floor slabs.

The floating population (single migrants) is imagined to be accomodated in these retrofitted volumes within the warehouses where the type completely changes from starkly industrial to a mixed-typology of housing cum warehousing. Technology is thus a method to generate the desired experience of life and form in a space of contestation.

(Published by ArchitectureLive! as part of their UrbanScripts essay writing competition)

The Eastern waterfront of Mumbai under the Port Trust stretches from the salt pans of Wadala in the north to the Sassoon dock at Colaba in the south. From its establishment, the port has been the gateway to India, and was a primary factor in the emergence of Mumbai as the commercial capital of the country. The city’s expanding growth and population pressure constrained the growth of the port by the 1970s and this led to the establishment of the Nhava Sheva port across Mumbai Harbour in Navi Mumbai in the late eighties in order to handle the growing container traffic. The shifting of the port from the island city to a region across the harbour left behind a space that remains like a remnant of the port. The current landscape is dotted with large, derelict and unused infrastructure which gives an overall sense of desolation.

But this feeling is a fleeting one, and on delving deeper into the site I attempted to understand the urban life produced in an area that is generally deemed as unsafe and shady, the different types of claims on space, the settlements that emerged as a result of a once-active port and the changing nature of the industrial landscape.

Studying one particular stretch of Darukhana- the finger-like projection of Kolsa Bunder through the lenses of history, politics, livelihood and everyday inhabitation enabled me to attempt to interrogate the life that now exists on this contested piece of land through the stories of men and women that dwell and/or work on the former port.

The Eastern waterfront has been a highly contested land for decades with parts being partially owned by the government as well as private companies and some owned by the Port trust. In the past two decades, various organisations like the UDRI (Urban design research Institute), the Bombay Port trust and HCP (Bimal Patel) conducted research on the waterfront and have proposed complete revamping or ‘revitalization’ of the portlands. The Rani Jadhav committee report of 2014 (Bombay Port trust) proposed a complete top-down approach towards the development of the eastern waterfront by terming it as ‘economic revitalization’ of the unregulated slums and unplanned growth of the informal sector by calling it ‘wasteful’.

The report strongly suggests that much of the land is under sub-optimal use and underutilised by the port. The HCP office looks at the waterfront as an available piece of land which has the potential to fulfil the city’s need for more open public spaces. Their perspective comes off as a touristic , recreational site and proposes a complete razedown approach of the existing. These institutions fail to recognise the existing fabric of the place which holds within them people who work and live through the vagaries of everyday life on the (ex) port.

While the UDRI studied the waterfront through a statistical angle by researching demographics through the lens of religion,origin of migration and land use patterns, it did not acknowledge the stories of the dwellers and workers who can no longer be termed migrants since they have become native to the port, having lived through the transformation the area has undergone.

James Holston in his essay titled ‘Spaces of Insurgent Citizenship’ states that the CIAM model of urban development relies on a “ subjective transformation of existing conditions” and uses techniques of shock to force a change. “These techniques emphasise de-contextualization, defamiliarization, and dehistoricization. Their central premise of transformation is that the new architecture/urban design would create set pieces within existing cities that would subvert and then regenerate the surrounding fabric of denatured social life.” Basically indicating that the introduction of a new building type within the existing framework of the city would affect it as a whole by transforming it. This would stand true in the case of the HCP proposal which aims to create (and thus apparently reclaim) large public areas and gentrify the Eastern waterfront.

My argument lies in the proposition that these livelihoods of the port have always existed under a state of precarity and continue to do so considering the proposals that have been projected. As an urbanist or an architect, I argue that it is necessary to study a place ethnographically in order to design for it. Ethnographic research gives an insight into the culture and practices followed by the people, in the context of the real environment and thus helps to plan and design with a certain degree of relevance to the space. History is political. It has always been written through the lens of a political agenda and thus it is simply not reliable enough to know in depth about a given place. The present emerges from the stories of people who live and breathe the air of the neighbourhood.

Below is an attempt at a thick description of a hydraulic pipe factory in Kolsa Bunder through a conversation with Ashim Chacha who has been working here for the past 17 years.

‘The mechanical whirring noise of the wheel is a constant background to anyone entering the workshop or the usual passerby.The hydraulic metal pipes are sliced by the wheel evenly such that the given marked length comes under the wheel. Ashim chacha works and lives in this hydraulic slicer factory on Kolsa Bunder.The workshop is a landscape of metal pipes, long and slender, occupying almost the entire length of the workshop.The ground is barely visible and one has to walk over this spread out floor of pipes. The shipment of pipes arrives from various sites in Mumbai and the pipes are sliced as per required length and shipped to Delhi, Gujarat etc. Ashim chacha works at the machine as well as collects shipments of pipes and helps unload them from the trucks. The workshop houses at least seventeen to eighteen workers at night. Most of them work in other factories nearby and get work as per need, but they dwell in the hydraulic workshop. The sheth (owner) of the workshop had suggested such an arrangement of sleeping at the workshop as the workers that migrated could not afford to pay rent or had arrived without family, thus making it difficult to find accommodation.All the workers living here have migrated from towns in Uttar Pradesh.The walls are lined with several ‘khaats’. A cabin constructed on a height within the factory becomes the kitchen for the workers. The night time meal is regularly cooked here while lunch is often served at a khanaval or near the factory where they respectively work.This cabin also becomes a collective space to keep everyone’s personal belongings. In this case, leisure is resorted to spending time ‘outside’ the dwelling as well as the place of work. The outside here simply refers to the road outside the workshop or the factories where they work. A parked motorbike or two, the corner paan-wala or the edges of roads become the primary spaces of rest, breaks or leisure.

Ashim chacha and his fellow dwellers wake up around 7 to 8am in the morning and go to the nearest public toilet to freshen themselves. The entire day is spent manning the machine and looking after other requirements in the shed. Here the idea of home is simply a space to rest once the work day is over. But simultaneously, it is also a space of work.’ I understand two important things from my conversation (and observation) here, one that the idea of dwelling is unbounded in a setting where economic restraint is the key factor, and two, that despite the absence of any planned spaces or intervals in a worker’s life, he will find ways to practise leisure. In the future, if given an opportunity to design, I will thus make use of these close observations of the environment in order to bring about a change that is relevant. The crucial question for us to consider is how do we include this ethnographic research in planning and think of the possibilities for change encountered in existing social conditions.

Holston states “ What planners need to look for are the emergent sources of citizenshipand their repression-that indicate this invention. They are not hard to find in the wake of this century’s important processes of change: massive migration to the world’s major cities, industrialization and deindustrialization, the sexual revolution, democratisation, and so forth.

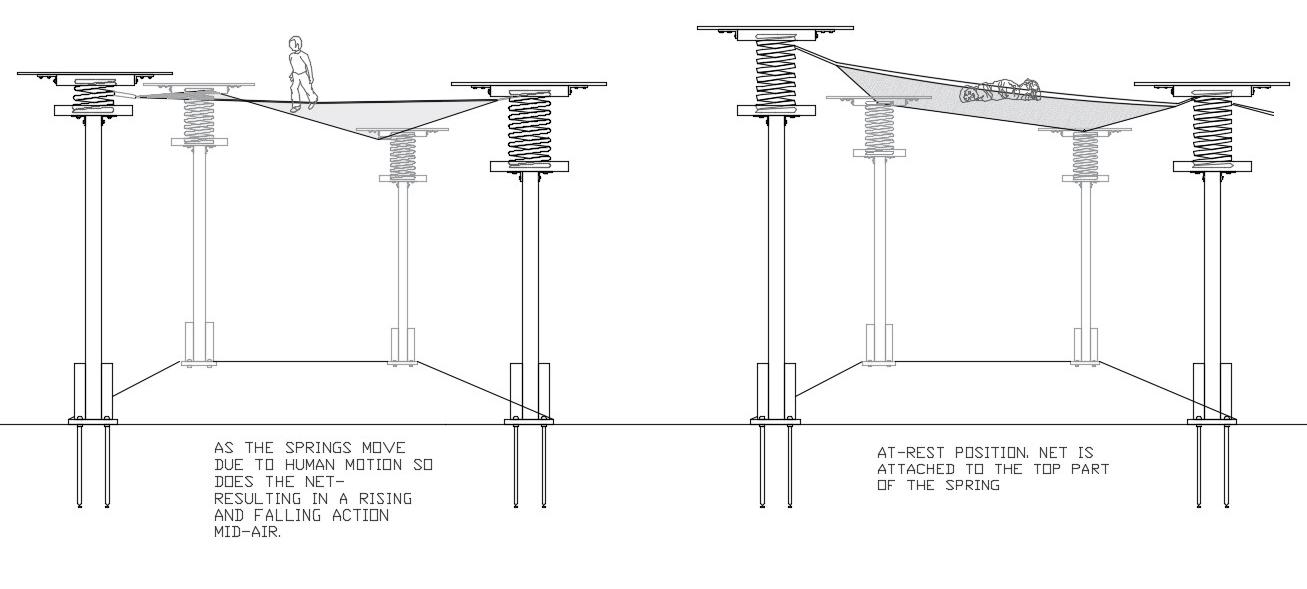

Initial working Principle

Collaborative Project By-

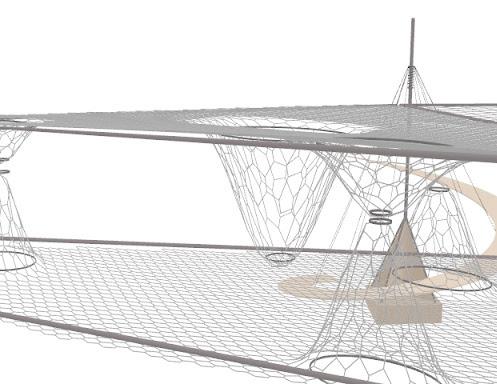

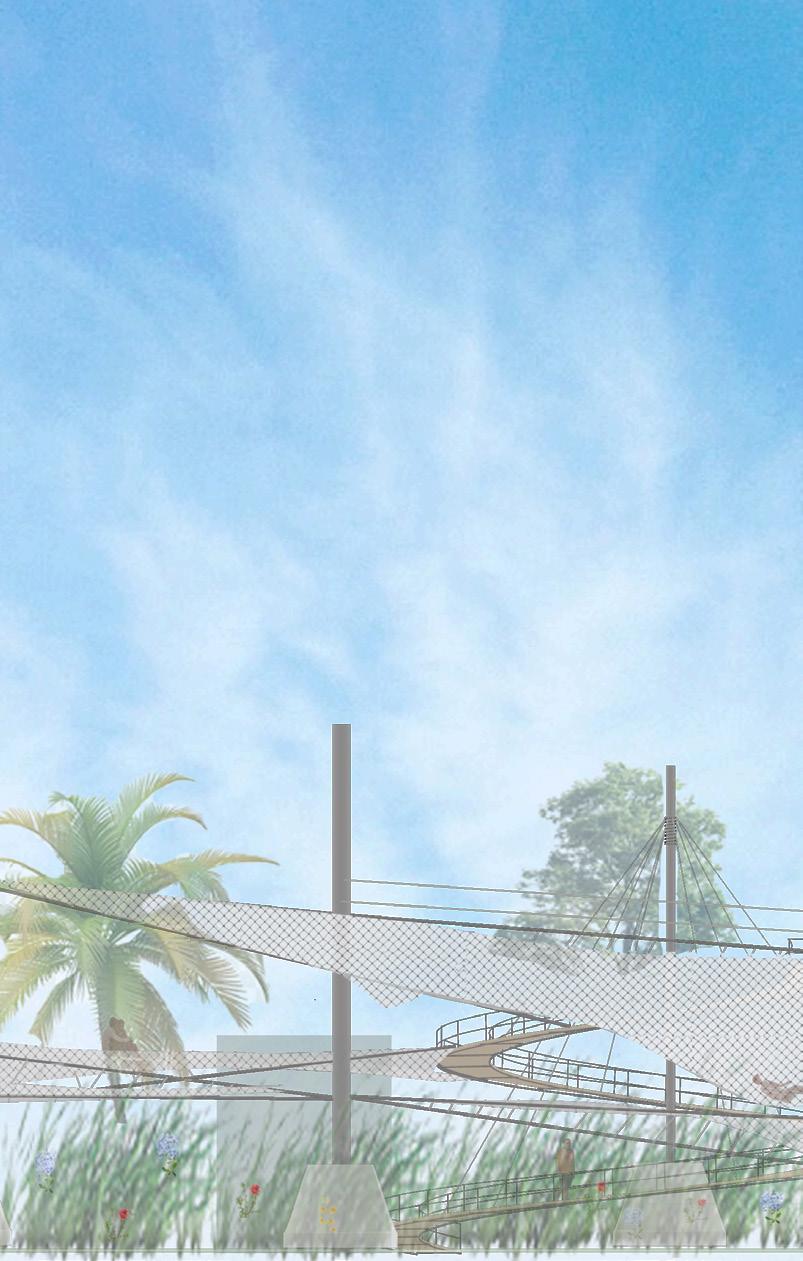

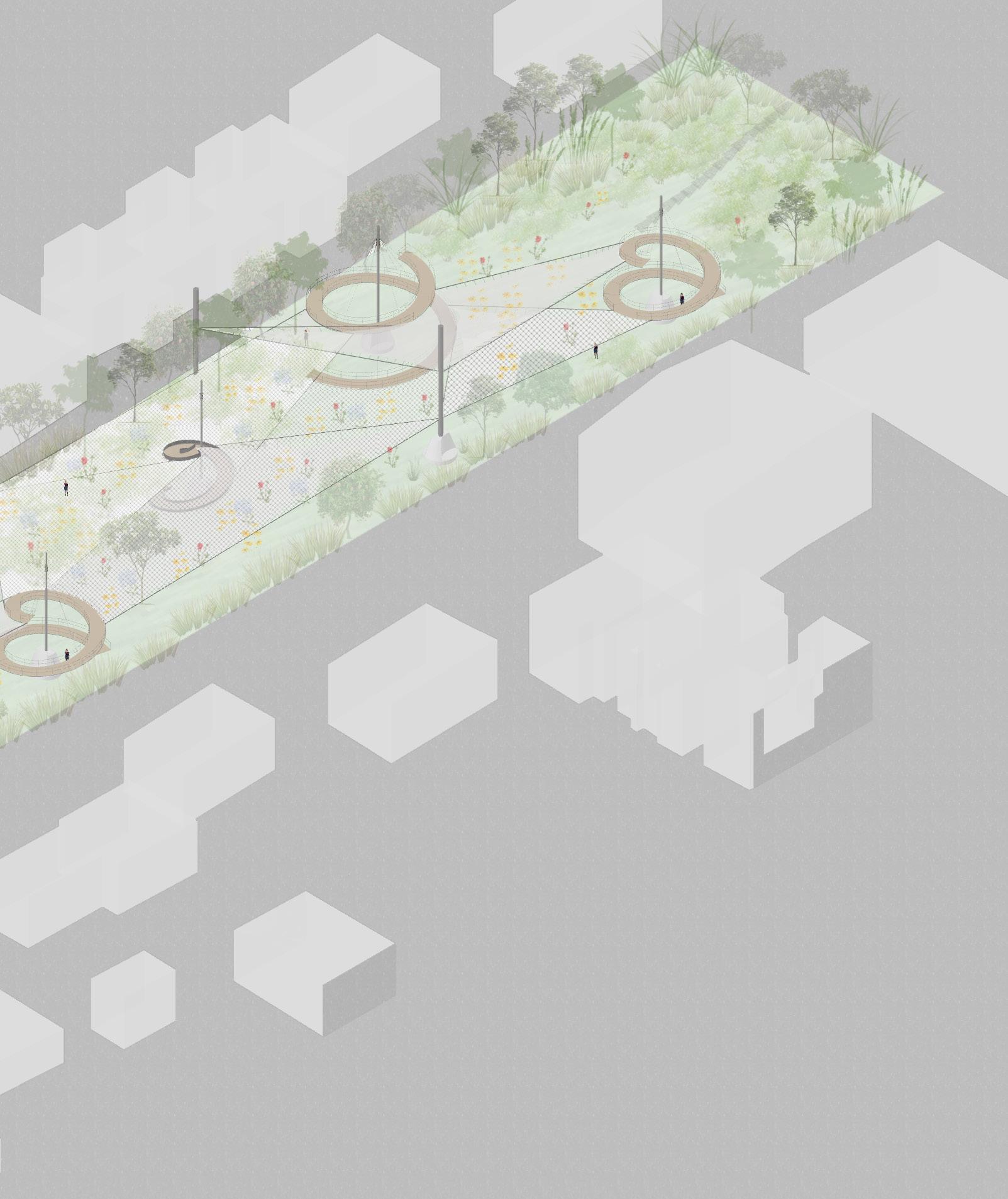

Tanuja Vartak and Krisha KothariThe studio aimed at exploring the possibilities of designing built-forms that are able to alter the environment, through altering of a specific phenomenon in the environment. The environment includes natural and non-natural phenomena which shape the rhythms of our lives and second, buildings are able to alter these environments and their experiences.

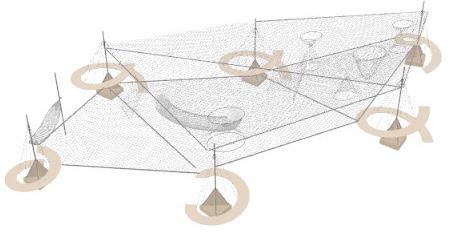

The two phenomenons identified through Tarkovsky’s movie Mirror were- one- that of the feeling of floating mid air and another- motion influenced by an external force. The process began with attempts towards the amalgamation of the two phenomena through several initial experiments spanning Magnetism, Buoyancy and then eventually the principle of compression and recoil by a spring or any surface that is under tension.

The principle on which our pavilion works- is spring action as a result of compression due to human weight and the consequential recoiling.

Initial idea for the pavilion

Plan showing pavilion spread out on site

The nets are composed such that they provide gradation of intimate spaces by facilitating tunnels as alternative of circulations, warps with holes to move from one space to another and also a central slide to add the tinge of playfulness. The overall idea was Elevating normalised experience by simply shifting the perspective as in this case the garden is experienced from a higher level also considering its sensorium interacting with the sky and the ground.

Axonometric of Pavilion on Site

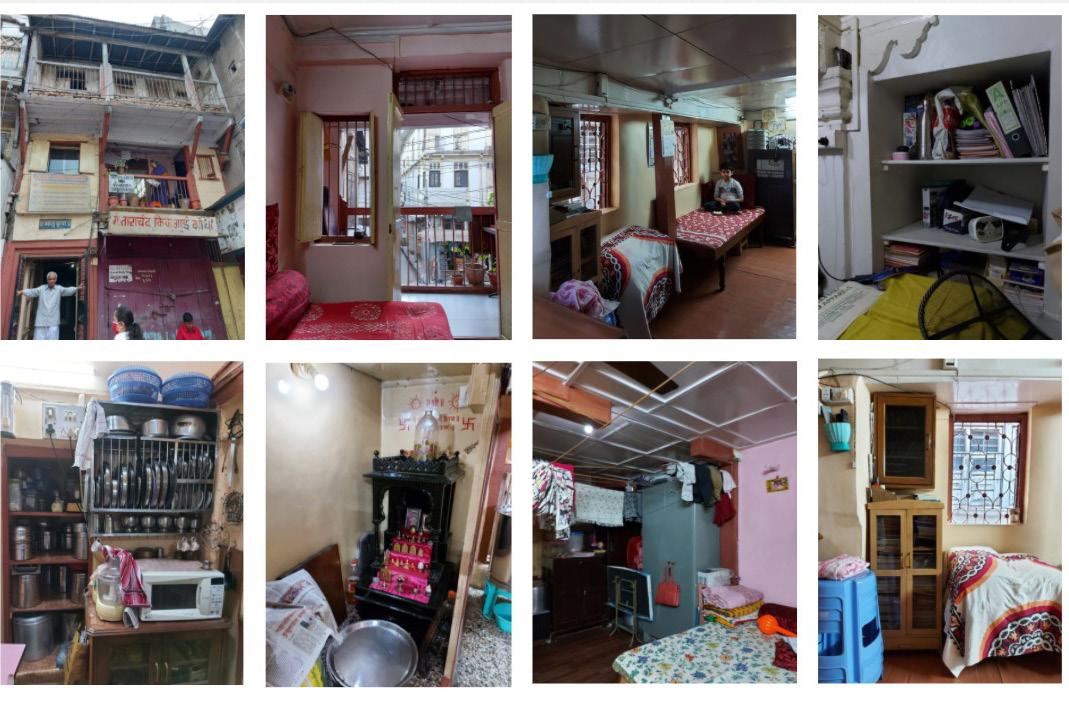

The studio aimed to identify patterns of living and related built-form in a neighbourhood precinct through identification of an architectural type and elements that come together to constitute a type to identify different forces (climatic, economic, social, behavioural) that shape type.

The garud wada is a century old wada in a lane of Saraf Bazaar in the inner city of Nashik where five generations of the Garud family have been living. It is a G+2 structure where the first floor is inhabited by a family of 8. The linear arrangement of spaces facilitates a constant interaction between family members as one room leads only to the next. The observation of the home lead to an imagination of it being a palimpsest where a modern family lived in an older structure which does not conform to the concepts of BHK.

The spatial imagination for the home in charkop would be such that the empty shell be overwritten by the principles that were observed in the wada. The design process was initiated by applying some of the observed patterns on the courtyard facing house, constricted by houses on both sides.

The wada house had a lot of inbuilt storage and majority of their belongings were kept in deeply recessed niches in the walls. This was the main observed pattern where the wall could potentially inhabit the entire home. The process involved experimenting to see if the wall could also afford resting spaces or seating spaces.

Narrative drawing of the existing

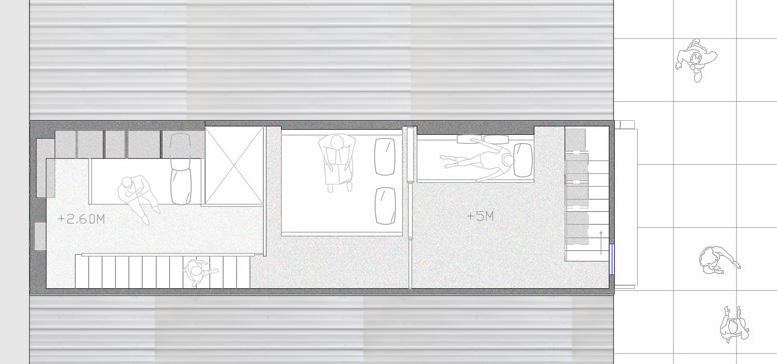

The street elevation opens up to show the shorter house section-which depicts the thicknesses of the concrete wall in varying capacities. The longer section shows the functions each thickness holds- one becomes a sleeping space while the other serves as the dining seating.

The home has four levels to it which merge into one another. The ground level is the most public space and as one goes higher the degree of publicness reduces. The external facade has recessed seating and as one enters there are multiple niches forming raincoat racks , a mandir and shoe storage. A dining space is carved within the wall. A visual connection is established between the person sitting on the staircase and people passing in the courtyard. The second level becomes a private space and consists of two sleeping spaces divided by a semi transparent screen.

Details are thought through articulation of surface and junctions of materiality to acquire the desired essence of space and experience. They display immediate expressions of the structure, language, system and function of the built form. Each detail thus narrates the story of its making, placing, proportioning and positioning at various stages.

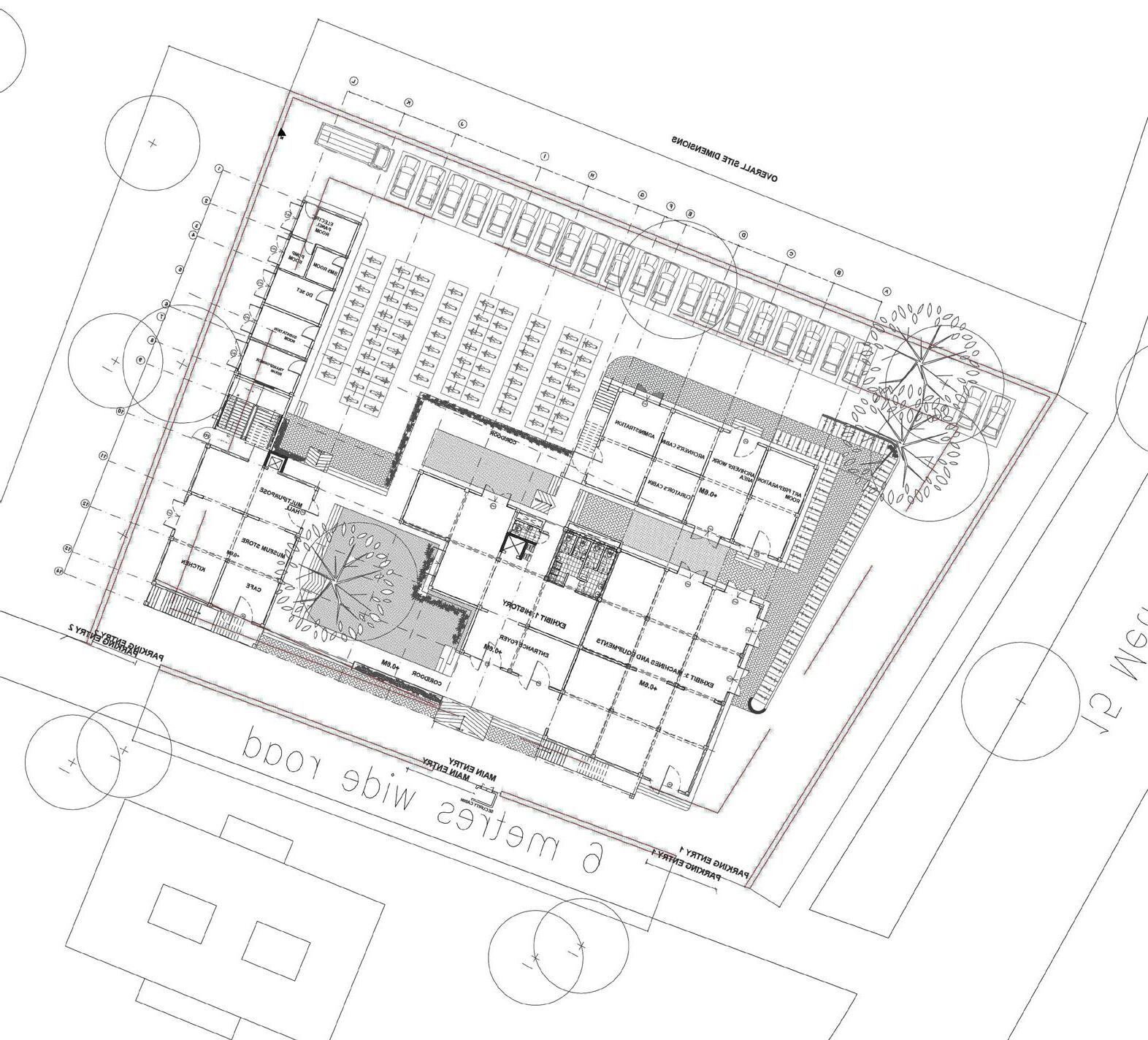

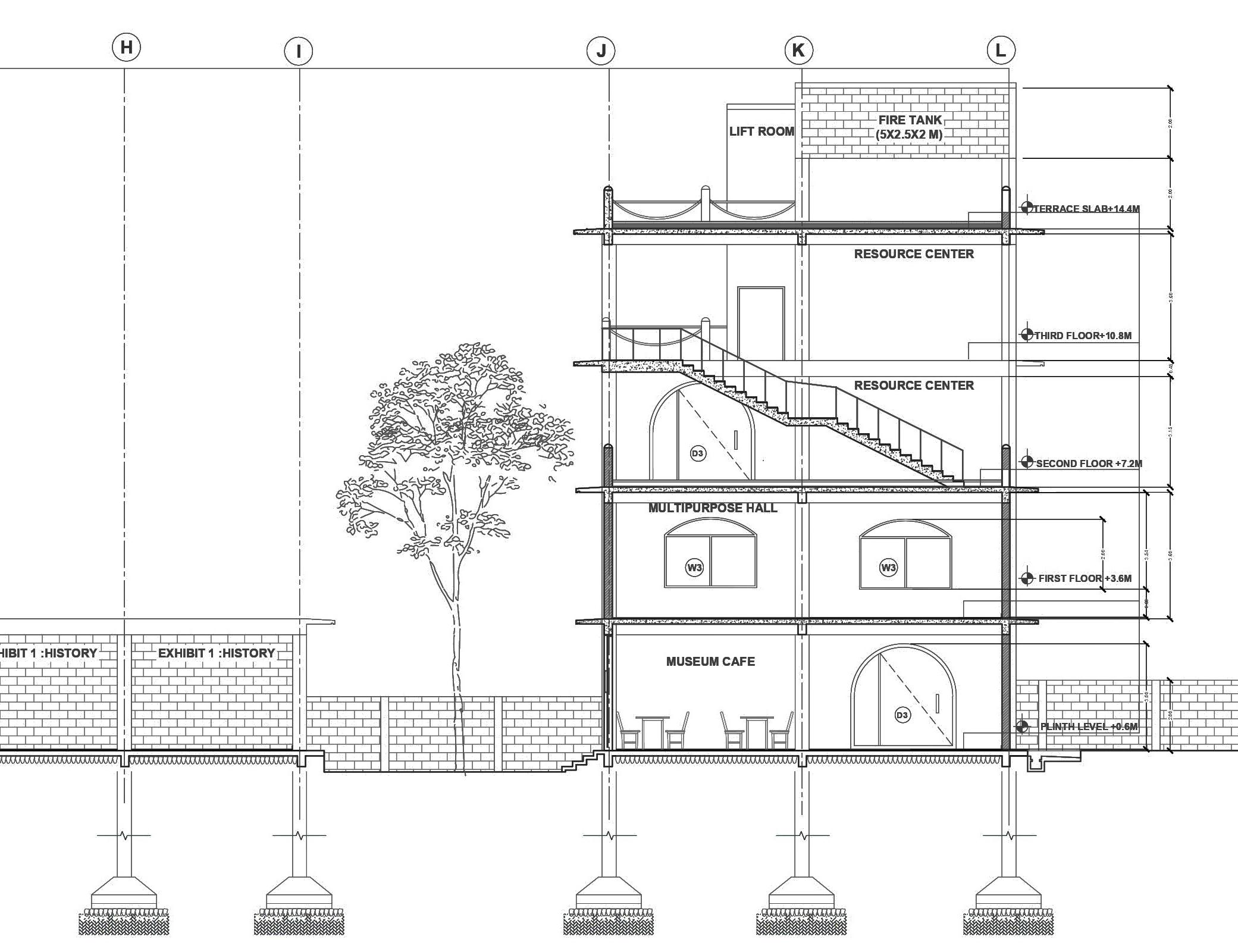

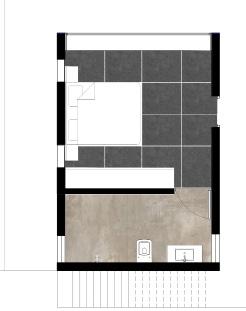

The Working Drawing exercise focused on designing for a Textile Museum at Paithan, Aurangabad.

Frame structure with brick walls was chosen as the system and materiallity and the design features arched entrances and openings. The form of the Museum was inspired by the Mesopotamian ziggurats that taper as the floors go higher.

One of the main design features is external single flight staircases on each floor that hilight the facade instead of simply being hidden, service spaces.

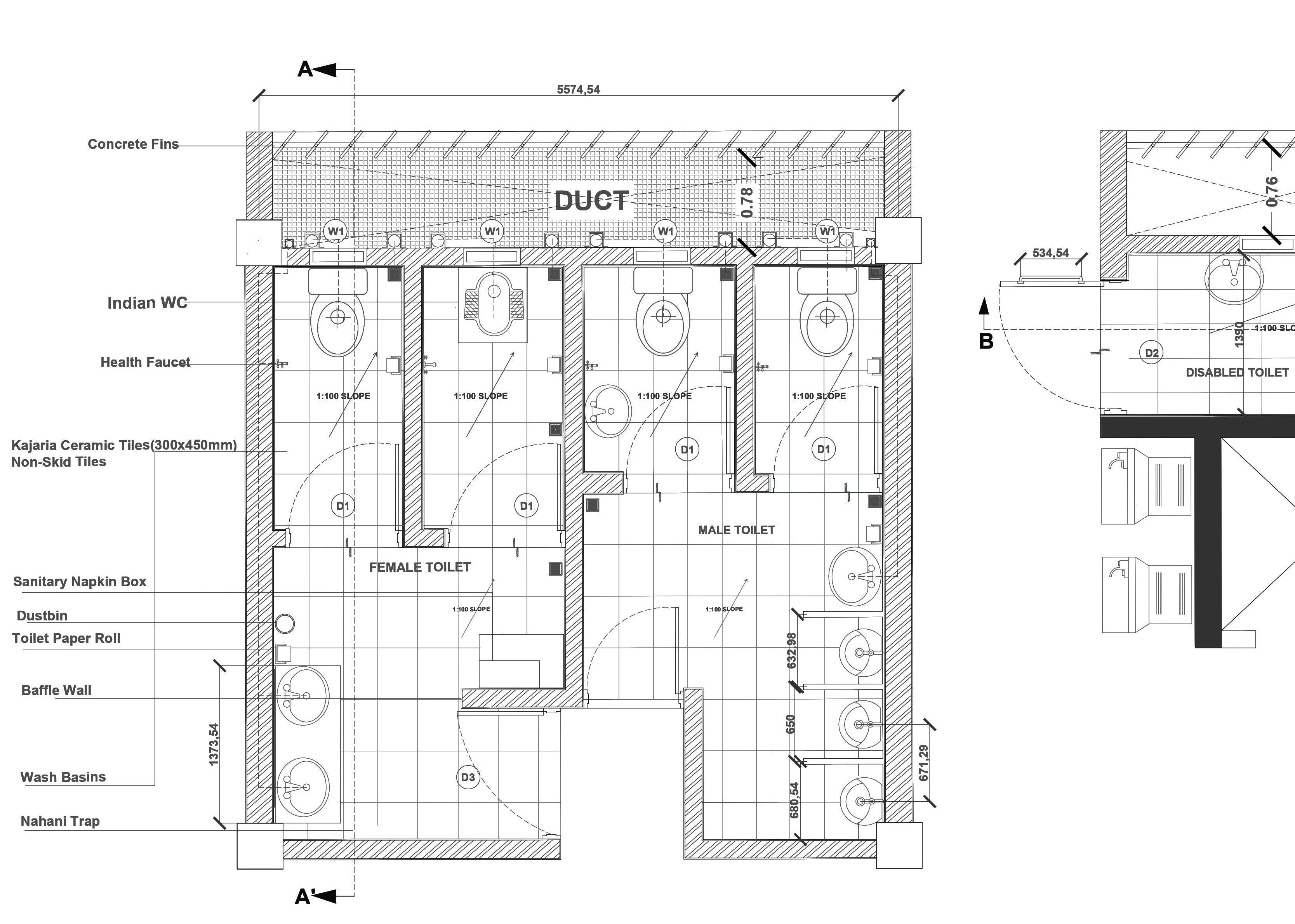

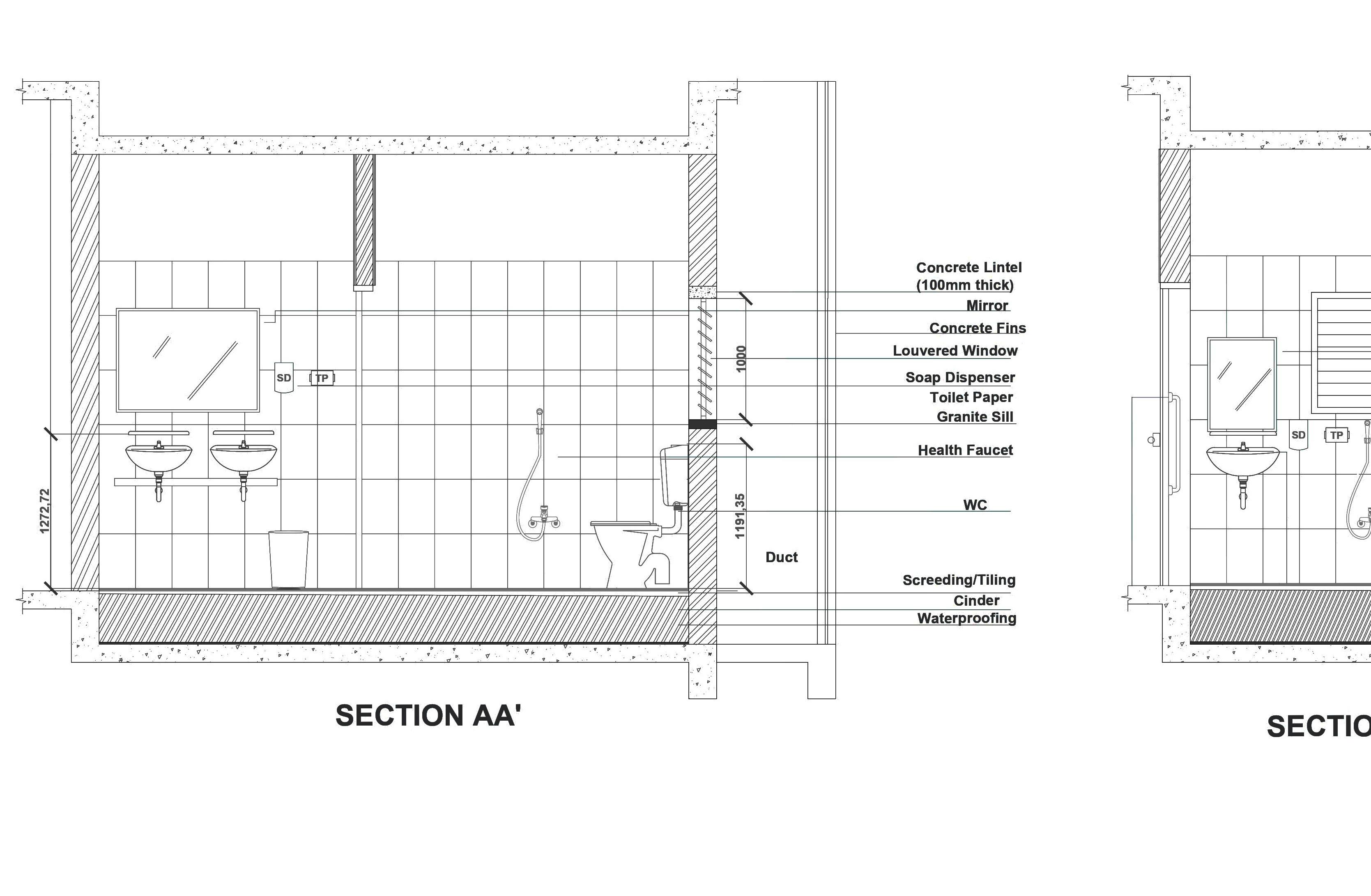

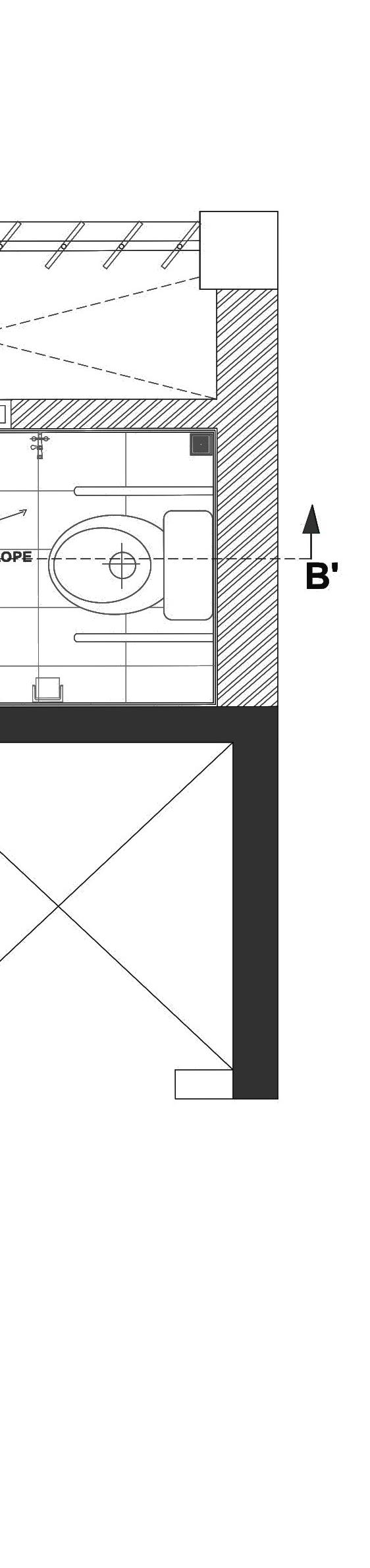

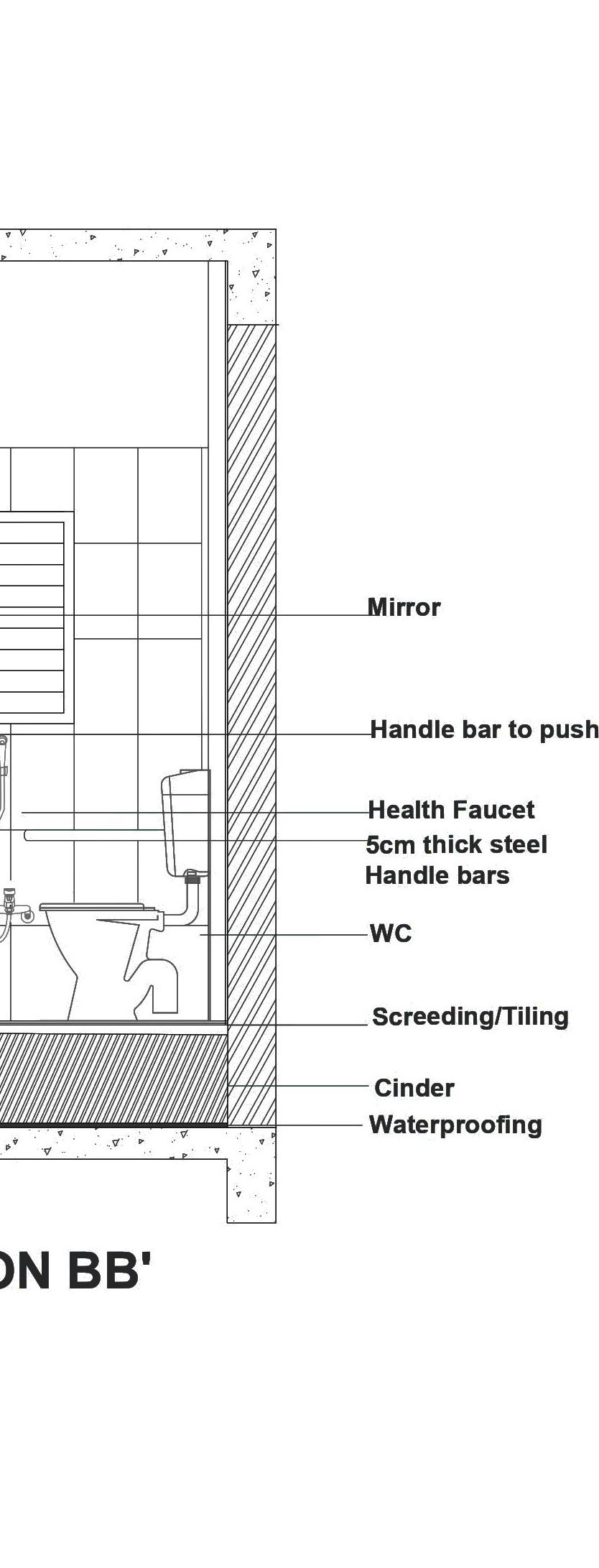

Toilet Plan

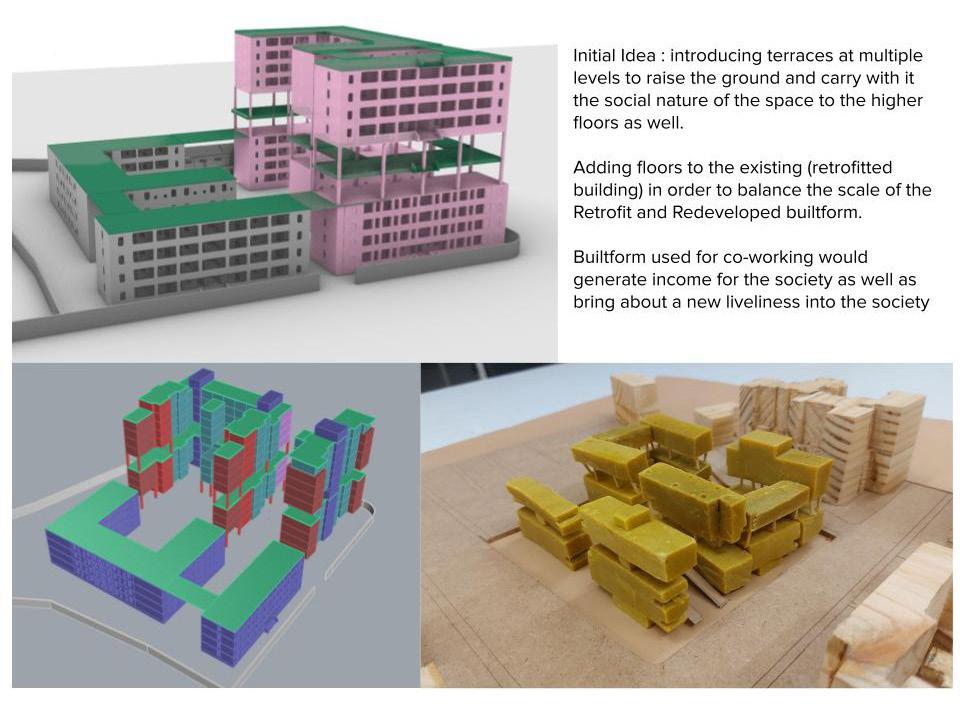

Partial Redevelopment and partial Retrofit model

The sudio questioned What new and relevant formal and spatial imaginations could be articulated for mass inhabitations in the emerging contexts of urbanization in India’s metro cities. The idea comes from keeping in mind the future of the society over the next 15-20 years where it is speculated to be largely populated by the elderly.

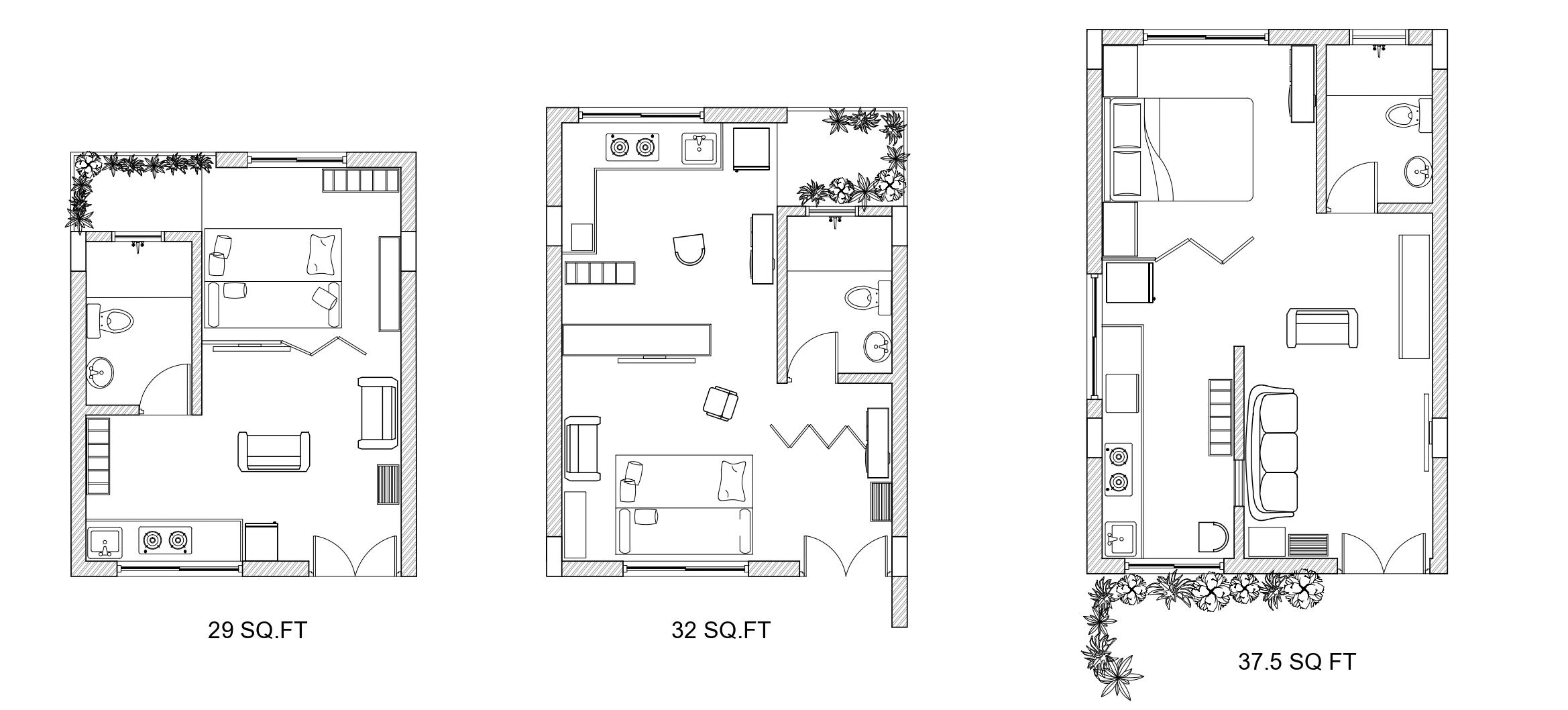

Bhaktiyog -the site for intervention is a G+3 storeyed, chawl like housing society built by Baburao Paranjape in the 1970s in Borivali west. The plot area is of 6513 sq m and the society consists of 208 apartments with houses of 3 configurations of area 240sqft, 270sqft and 310sqft.

I experimented with Partial Redevelopment and Partial Retrofit of the existing builtform where each house would get an additional 30% area in order to accomodate a WC each. Individual

The section shows the voids- terraces which are intended to be social spaces which directs my idea of amenities. From the 6th floor till the terrace, the builtform has been slightly shifted behind in order to create a visual connection between the mid-level terrace and the ground.

Cement is a binding agent for the Pigment to be applied on Marble. Various pigments were tested on the slabs in order to observe which plaster would look good on the wall.

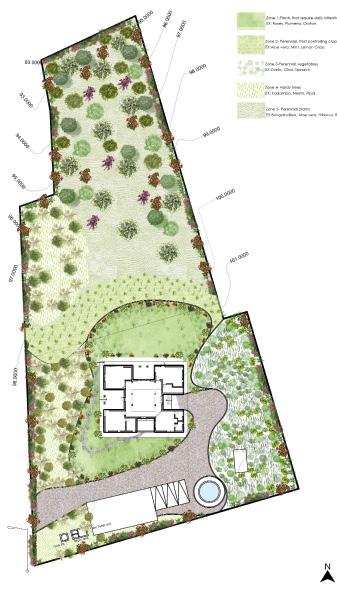

During my internship at a bio-architecture firm I was exposed to natural building methods and plasters while also working on digital models of weekend homes that were in the design and pre-construction phase.

Permaculture with five zones- each zone having a particular variety of trees has been planned throughout the site. The immediate area around the house has been planned keeping in mind the accessibility and privacy of the house. The site model to the left indicates

1. The soft-paved gravel pathway -so that rainwater percolates through and increases groundwater level.

2.Combination of Tall and medium trees to be planted along the Southern and Western edge of the site for filtering of harsh sunlight.

The process of Flooring for Chinchore Farm house in Karjat demanded to look at each space and it’s usage in order to explore the combination of tiles/ stone and IPS that can be proposed.

I’ve often turned to Watercolor as a medium of artistic expression and painting encourages me to look at the finer details of a setting. I am often inspired by my surroundings or reference from pictures from my travels.

While I have always enjoyed reading fiction, I recently also started reflecting and writing small anecdotes on the books i read. This helps me to understand how I have related to the story and move beyond the typical ‘nice’ and ‘good’ adjectives I would otherwise use to describe it. I recently read a short coming-of-age novel by Sally Rooney titled Normal People and wrote my thoughts on the same.

I chose not to pick up another book immediately after this one got over , waited for a whole week infact, to feel something deeply and to let it sink in. And it didn’t.

And so a week later I realised that it was the very anticlimactic ending to the story that was almost so…normal (for lack of a better word); that did not give me a sudden bout of either grief or joy for the characters but a rather slow process of realisation.

“You should go, she says. I’ll always be here. You know that.”

The book ends with this line and it almost internally destroys you slowly when you realize it because isn’t this what life is like? This is how reality is most of the time. Someone you love is eventually going to go away or you will and and there starts the long wait, if you will. But if you love them you let them go, on to better things they desire. What you once had will be left behind, they will come back a changed person if they do come back at all.

Reminds me of the movie La la Land too infact where Sebastian and Mia don’t simply drift apart but it specifically happens because they each want different things from life at the same time. The real test lies in the wait and in the hope of it all. The hope that they will come back and things will be the same but a moment passed is a moment lost.