Art as a platform for Science

Innovation: an ethnography e xperimental approach of an amateur-explorer’s journey at the interface of Art and Science

Abstract

Fingerprints, maps networks, memories, shapes, structure, function, layers, patterns –

Language: The Arts and Science share historical bonds, however, on the twentieth century, academia moved away from a vivid dialogue between these two perspectives of the world. Herein, is presented an experimental ethnography describing and discussing the accumulated informal knowledge based on observations and reflections within the context of experimental art-science interactions arising from the ethnographer’s creations and experiences with three different communities. An illustration of the ethnographer’s inner landscape is used as a medium to explore how art-science interactions relate to Innovation and Creativity. Turning points, Tension points, Dead Ends and New Pathways are discussed with relevant literature findings. Future avenues of research and open questions are left to the reader - seeing it as if it was an entrepreneurial ecosystem of Art and Science, what would be the impacts on different dimensions – the economical, technological and societal?

Key words

Art Science Science Communication Creation Creativity Innovation

Experimental Ethnography STEAM Transdisciplinary Environment Climate

Change Social Inclusion Diversity Interface Poetry Movement Sound Maps

Cartography Visual learning Activism Multiculturalism

Index of content

Introduction

Conceptual framework and Methodologies

Case studies

Discussion

Conclusion

2

Introduction

The perspective of a common Language in a shared future

The language of Art and the language of Science – Interactions and blind spots for Innovation

According to E. O. Wilson “the ongoing fragmentation of knowledge and the resulting chaos in philosophy are not reflections of the real world but artifacts of scholarship” [1] Scientists are able to translate subtle signals at different and impressive scales, from galaxies to nuclear interactions and, sometimes, using the same “tricks” as artists do

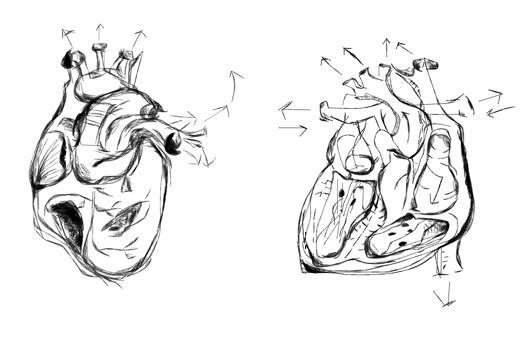

light, sound, and movement - chemists often draw and interpret or express information visually, for example, while making sense of the data generated by molecular characterization techniques, where they obtain spectrums of non-aleatory patterns asking for meaning and correlations to the real world laws. Chemistry created tools of closeness and connection, while challenging the observant to learn how to distinguish information from noise – fingerprints, maps networks, memories, shapes, structure, function, layers, language. Artists, painters, designers, visual poets often draw and interpret or express information visually and also create tools of closeness and connection, while challenging the observant to learn how to distinguish information from noise.

The Arts and Science share historical bonds [2] Their languages meet in the point where they feed and inspire themselves through observations of the world. However, the questions and methods addressed by these two languages might diverge and present, of course, specific characteristics that make their perspectives of the world distinct. [3, 4] In thetwentieth century, academiamovedawayfrom an openpartnershipbetweenthese two languages. In recent years, there has been a renewed interest and awakening of the collaborativeapproach Thiscanbesupportedbytheemergenceofjournalssuchas SciArt Magazine and Leonardo and artist-in-residence programs at scientific research centers such as the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) [2]

Questions could be raised on the nature of these interactions – how, when and where does the Language of Art drives forward Scientific Research and Methods and vice-versa; how and why are these interactions beneficial for the innovation in both fields; what do these collaborations mean when addressing global challenges and how can they be a medium

3

–

fortransferringknowledgeacrossareas of research. Moreover, could aquestionofartistic nature catalyze scientific investigation? How to create space for this to happen and what means innovation within this collaboration context? Is it possible to bring innovation in the scientific method, to create novel materials and instruments of measurement, to encounter new ways of seeing and express the same generated data? Can Art cause disruption in Science and Science in Art?

Bridges and interfaces – concepts as living things

Transferring, Transforming, Co-creating

Carey Jewitt and co-authors [5] explored the methodological innovation in the social sciences related to digital environments and the arts. The authors argued that merging the arts in their research practices had the potential to open up spaces for innovative social science questions and methods in several ways from re-situating methodologies, transferring methods and concepts and generating new ones.

The authors observed how their participants in different work groups explored sensory and spatial concepts related with the body using an eclectic spectra of art-based research methods leading to the identification of more instances where methodological innovation was reported among the arts work group cases than the social science work group cases.

Jane Calvert and Pablo Schyfter [6] reflected on what could Science and Technology Studies (STS) learn from art and design through the analysis of a project where synthetic biologists were paired to collaborate with artists and designers. An interesting quote from the authors was, according to them, the “slightly uncomfortable question of whether artists anddesignersare moresuccessful in theirengagements with syntheticbiologythan we are” (we

The STS researchers of the project). Not only similarities between the objective of STS researchers and artists were mentioned but also important differences were pointed out between approaches, for example, the observation that art, in general, creates tangible objects with an immediacy character-property that has the consequence of allowing different types of discussion. The authors argued that the experimental and unexpected nature of these inter-field collaborations were a figure of merit for enriching the critic dimension of social scientific work.

4

–

Inter-field collaborations flow into a spectrum of frameworks and can fit into the category of Transdisciplinary, which is concerned with the fusion of intellectual frameworks beyond individual disciplinary, transcending traditional boundaries to generate knowledge. There is also the concept of Interdisciplinarity that differs from Transdisciplinary since it comprises links between fields of knowledge in a coherent and coordinated way. Multidisciplinarity is described as an additive approach where disciplines stay within their boundaries. [2, 7-10]

Conceptual framework and Methodologies

The observant eyes

Description of a Beginner’s eyes and its tools

“Meaning is socially produced and collectively held and by being part of the community the ethnographer begins, however imperfectly, to participate in these meanings too.” [11]

Finding a research method to describe the accumulated knowledge based on observations and reflections within the context of experimental art-science collaborations culminated itself in an experimental ethnography, herein presented. Ethnography is a methodology of observation, used in some research areas such as anthropology and sociology, in which an array of techniques from informal interviews, direct observations, group discussions and self-analysis of personal documents produced in collective context, notes, diaries and transcripts are utilized. [12] Here the word “Experimental” is used to encompass the previous unfamiliarity of the ethnographer with this methodology, due to its background in exact sciences, and for marking the beginner’s feeling of experimenting something new, shared by scientists and artists and by research at interfaces and grey areas of knowledge. Here the word “Experimental” also comprises borrowed associations from the artistic field and intends to cause a double meaning sensation in the reader. Finally, “Experimental” is also used as a short for sketch/draft as this is a work in progress and more data should be generated in order to have a more robust and coherent “ethnography landscape” . Several questions such as – what to measure, how to measure, how to collect and organize data, how to generate data, how to choose the sample were itself an experience, and to this date it is still on progress. Despite ethnography being a method that can highlight detailed information on how informants see their world it is pointed out

5

the limitation that it is based upon the judgements, assumptions and prior knowledge and experience of the observer’s eyes. [11, 12] This qualitative technique has not been the most accepted when compared to quantitative research techniques, although it became the central method in anthropology. One of the main critiques from the sociology point of view to this methodology was the potential bias and the subjective nature. [11]

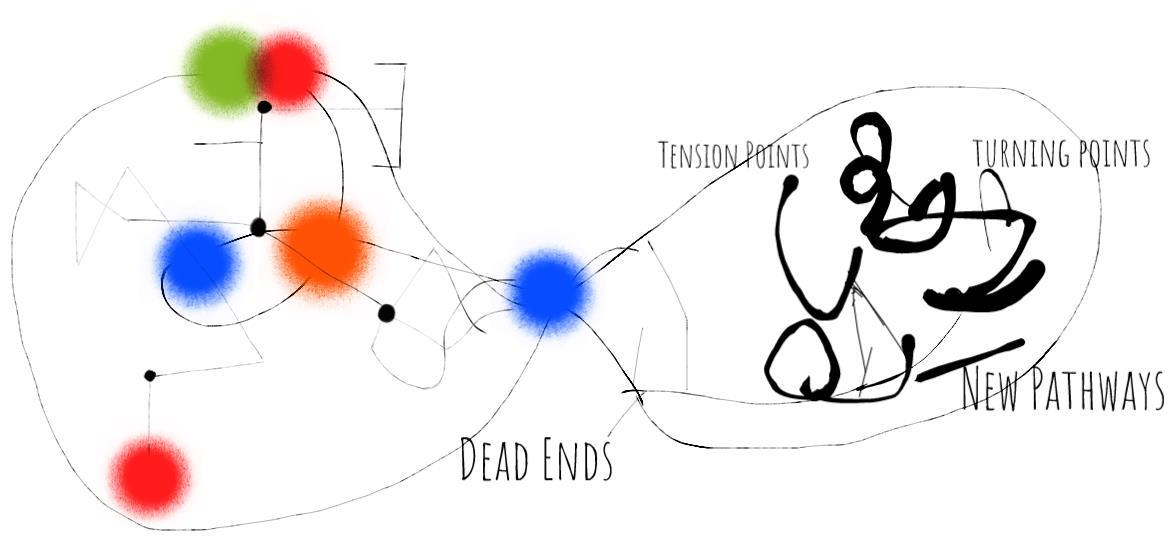

As described by other authors [11, 13], here is outlined a self-study from the approach of an autoethnography comprised of self-insight data generated explorations in the form of self-reflections discussed with relevant literature findings organized by the identification of 1) turning points; 2) tension points; 3) dead ends and 4) new pathways caused by the experience of creating art-science works and showing and discussing them with different communities and individuals or groups where the ethnographer was inserted.

Searching one’s own language

Mapping, Maps, Cartographers

How to brush a landscape of art-science ethnographic interactions?

You are here.

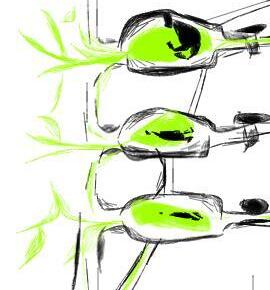

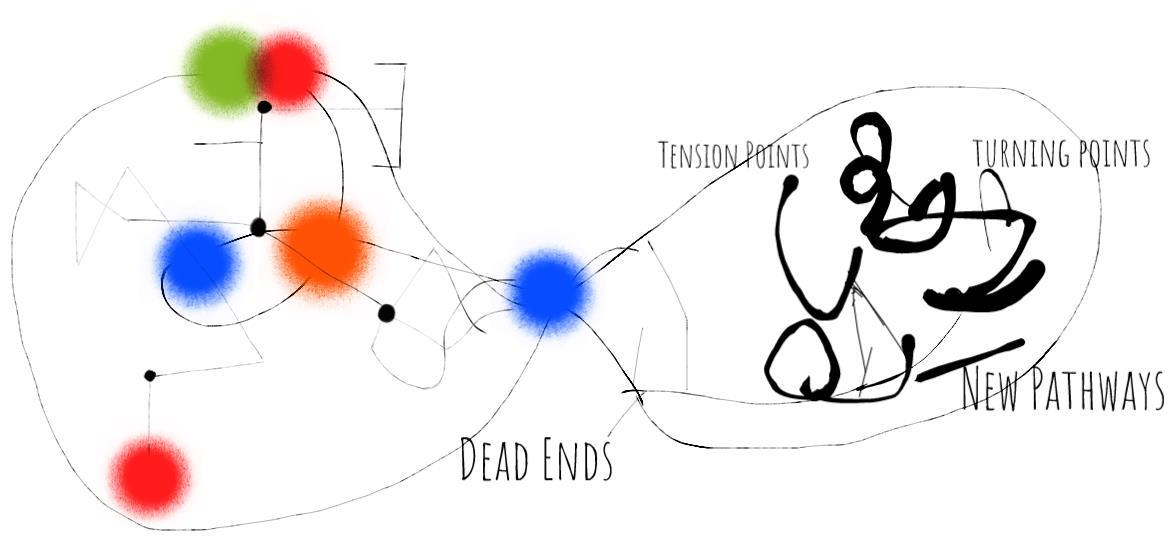

A special issue of the International Journal of Cartography [14] “Cartographers write about Cartography” invited Cartographers to write personal essays on a specific map to illustrate what inspired them as geospatial scientists, geographers and designers. According to the editorial of the special issue (maps) “They can work, artistically, scientifically, technically– or in all three of these areas.” Inspired bythe concept of maps, Figure 1 represents a mind map produced to illustrate and identify the communities with which the ethnographer interacted along is journey at the interface of art and science by means of specific experimental collaborations and informal projects.

6

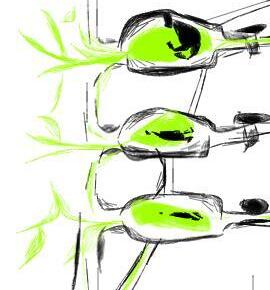

Figure 1 – The ethnographer’s inner landscape

Figure 1 – The ethnographer’s inner landscape

Case studies

Figure 1 illustrates an ethnographic landscape from the perspective of the ethnographer that walks along an axis that symbolizes different interfaces between 4 main areas of knowledge, represented in green. From the society fields, rivers in blue are born and irrigate the places where three different communities live – The scientific community, The artistic community and the Third sector community. This last community refers to individuals working on the sector of NGO’s related to solving problems of social inclusion, environmental consciousness awareness and active citizenship. The other two communities are composed by individuals that work in science areas as researchers, students or professors and the artistic community refers to individuals that work on the cultural sector as well as culture consumers. The ethnographer by means of its own projects interacted with these three different communities. The different types of projects represented on the map are identified and classified as peripheral, encompassing smaller art-science experiences from the ethnographer, or marked as experimental projects referring to artistic outputs which were created from earlier smaller experiences and, on the perspective of the ethnographer, represent a more mature an complete state of the ethnographer’s experimental works.

Selected case study from the ethnographic landscape

Orpheu 4.0 [15] – is a prototype of a scientific-artivist street magazine that explores the language of art as a platform for transferring scientific knowledge to society. Orpheu 4.0 aims to promote transdisciplinary environments and explore the intersection and barriers ofdifferentsystemsofthinkingtoinspirethedialogue betweendifferentfieldsofresearch as an invitation to co-creation A prototype in digital format of a special edition dedicated to SustainableChemistrywas presented as abrief summaryof small creations –exploring poetry, words, movement, color, sound, aesthetics - inspired on the presented 9 themes of the module Sustainable Processes and Technologies, which was part of the doctoral programonSustainableChemistrywheretheethnographerisenrolled.Theprototype [15] was created within that context and presented to a group of students which come from the fields of Chemistry, Biochemistry, Engineering, mainly, and was also shared with some researchers and members of the Lab group on Environmental Chemistry where the ethnographer is developing the doctoral thesis. The inputs from the scientific community were in the format of informal discussions based on their impression on the work

8

developed and presented. Poetry without borders are a set of initiatives that started with the writing of poems inspired on science language and then evolved to informal meetings of sharing poetryin a multicultural environment. The focus of the poetry sharing sessions is more to listen to poetry in other languages and to find connections and divergent pathways in the way that people from different languages think. This sessions were conducted outdoors with a variable group of participants, most of them with connections to the art fields and with some link to being a volunteer or worker at local NGO´s. Linguagem comum encompasses the personal art-science explorations created by the ethnographer that involve the exploration of word, sound, image to translate messages and concepts from different areas of knowledge. These experiences were mainly shared with individuals from the scientific community and the artistic community, in separate, always in the format of informal discussions with the ethnographer.

Discussion

Art, Science, Environment and Society

Orpheu 4.0 – Turning points, Tension points, Dead Ends, New Pathways

Sustainability is one of the flags that is being constantly raised and discussed by different key players and communities such as scientists, legislators, activists and the civil society. But how deep is the knowledge of these different communities on how to achieve a more sustainable economic system? Do they share methodologies, approaches and solutions?

Sustainability is a global challenge and therefore, the scientific knowledge from areas suchasGreenEngineeringshouldalsobeatoolforeachindividualtorethinkitsbehavior, lifestyle and relation with our planet, its resources and living beings. Orpheu 4.0 special edition on Green Engineering aimed to show how that discussion could be mediated between different communities that express themselves in different languages. There were some turning points, identified by the ethnographer, in its own perspective of the thematic of Sustainability related to the comprehension of the concepts coming from Chemistry by having to transform them into visual poems. From the scientific community, some students shared with the ethnographer that seeing the same concepts that they are always familiar with presented in an artistic way gave them another perspective of their own work. From the perspective of the ethnographer, the beauty, the

9

visual expression connects more immediately the public than the conceptual part of the artistic piece and might be a way of connecting more abstract concepts coming from the fields of exact sciences to general audiences. Orpheu 4.0 stayed in the memory of some students as something that they had not seen before or had not consider before. From the ethnographer’s perspective this kind of reaction could be a start for the process of innovation on the scientific communities and on the way they see the same data and the same concepts each day, creating therefore new pathways. The tension points were more related with the discomfort from the ethnographer when presenting something in a very different language than the scientific community audience is used to. That can create some barriers in the openness of the presenter that tends to express itself more cautiously, fearing rejection or incomprehension. When translating concepts from science to art, some dead ends – perspectives, questions that don’t make sense or are really disruptive to science paradigms - might arise. Some artistic translations might generate confusion from the part of the audience if they are not well contextualized, due to the subjective and multiple perspective nature of artistic expression. But in the other hand, dead ends can turn into new pathways or turning points if the audience is well guided and receives the tools theyneed to interpret the artistic piece inspired in science that they are looking into.

Turning points, Tension points, Dead Ends, New Pathways in literature

Other authors [6] reported “pertinent and destabilizing” questions arisingfromthedialogue between artists and scientists and reflected on how the artistic expression could encompass the human perspective of science questioning its applications and focus of research direction. There hasbeenreported alsothe“openingup”andthesimilaritiesbetweenthegoalsofscientists and artists. Some spotted differences were in the more “playful, free, humorous” perspective from the art field contribution. [6] The authors also reported that participants

10

in transdisciplinary experiments found that context suitable for developing innovative solutions to their demanding and increasingly complex challenges.

Beyond Science Communication Environmental Activism and Social innovation

There is well described that Art–Science collaborations can communicate science and important topics of research impacting the society. However, it tends to stop at science communication, as a passive state from the receiver. [16] Art has the tools for going beyond being a medium of transmitting knowledge and cause social transformation, which is important in addressing global challenges such as climate change. [17, 18] Even in the field of science communication, there is more to develop than simply illustrating science concepts. Some authors pointed out that there is a need to develop new forms of more interactive and conscious communication and that the process of finding ways to communicate science is not only important for the society but also for the researcher and the scientific community. Visuals are important to generate new ideas and thoughts when the research is at a conceptual phase, for example. [16]

Diversity

Art might be a medium of inclusion for diversity of though and openness to what is different. Other authors reported that highly heterogeneous groups might have communication and coordination problems These studies referred especiallyto structural diversity variables (i.e., age, race, gender, and affiliation) and team performance. Structural diversity appears to be important, not just for collective intelligence, but also for scientific impact. Diversity, especially ethnic diversity, correlated positively with the impact of scientific articles The rising trend of knowledge production by teams could be based on the existence of collective intelligence, together with the increasing complexity of scientific problems. [8, 19]

Creativity in Science

From education to data art

How much importance is given to divergent, lateral, and associative thinking and creativity in the educational systems of students from the fields of the exact sciences? Despite this, creativity is seen as an evolvedcognitive mechanism thatallowsabstraction, being crucial for performing cutting-edge research.

[19] Several educational actions on the STEAM approach have been reported, as with respect to including Arts (the A in STEAM) to fill in the gap of the current educational standard models. [7]

João Carlos Paiva and co-authors [20], reported how they connected poetry with chemistry within the context of chemistry students that were asked to write poetry and illustrate posters inspired on chemistry themes. The authors highlighted that poetry was seen by some students as a “cognitive or instrumental dimension” that made chemistry concepts “more understandable”. The authors had the intention of diversify the chemistry learning process with poetry and allowing “students to develop a personal significance of chemistry theories and methods.”

Applications of creativity in science might go further into data treatment. For example, Florbela Pereira and co-authors [21] transformed the information of a (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy) FTIR spectrum to (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) MIDI sound files. Their objective was to make accessible the information that is in Infra-Red spectrumstoblindandvisuallyimpairedstudents.Theycreatedasonifiedinfraredspectra where selected musical instrument frequencies are correlated with the intensity of the corresponding band absorptions to be possible to identify the typical functional groups or a set of frequencies related to a particular structural pattern in a molecule. Could the data provided by characterization techniques such as the one used by Florbela Pereira and coauthors be transformed by musicians? What would be the advantages and significance of transforming that type of data into artistic expression for both chemists, musicians and the community? What if in the process of transformation of a specific kind of data into another kind of expression, unusual insights about what to look for were created? How

12

these visual interpretations influence the way researchers perceive the micro and macro world they work with - how can the language in which they express and convert the data they produce influence the way they interpret their results and what kind of biases might be generated? In which different languages could the data generated from the scientific method be expressed other than the scientific language and context? What would be missed, when would the information loose its sense and what would be the turning points and new pathways?

Conclusion

The journey at the interface of such rich, complex and branched research fields is not an easy one and is often described by dead ends and tension points – where the different languages in which different communities express their views of the world gives space to resistance to dialogue and co-creation. As an amateur artist, the ethnographer receiving training and education on the scientific area often felt a sensation of misplace and misfit, but the scientific method shaped its art and way of thinking. As a scientist, the ethnographer, found countless times in Art cognitive tools to better understand and express scientific knowledge and fuel for solving problems using divergent approaches. From the ethnographer’s perspective, Art gave “depth” to Science, Art gave contour, limits, questions, barriers, avenues of understanding and new layers to the scientific language. Science gave structure to Art, priorities, meaning, sense, context, tools, strength and inspiration.

Often in Portugal, the ethnographer listens both to researchers from the science field and artists criticizing the working conditions and the public awareness they receive. The ethnographer found connection in the shared problems from both artists and scientists in

13

the economic and social contexts of Portugal. How could these collaborations between art-science help to mitigate some of the struggles reported by professionals on these fields? Seeing it as if it was an entrepreneurial ecosystem of Art and Science, what would be the impacts on the different dimensions – the economical, technological and societal?

References

[1] Carlie D. Trott Trevor L. Even, Susan M. Frame, 2020, Merging the arts and sciences for collaborative sustainability action: a methodological framework, Sustainability Science vol (15), pp 1067–1085 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00798-7.

[2] Sarah E. Clark, Eric Magrane, Thomas Baumgartner, Scott E. K. Bennett, Michael Bogan, Taylor Edwards, Mark A. Dimmitt, Heather Green, Charles Hedgcock, Benjamin M. Johnson, Maria R. Johnson, Kathleen Velo, and Benjamin T., 2020, A Transdisciplinary Approach to Art–Science Collaboration, BioScience, vol (70), pp 821-829, DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biaa076.

[3] Nicolas J. Bullot, William P. Seeley, Stephen Davies, 2017, Art and Science: A Philosophical Sketch of Their Historical Complexity and Codependence, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol (75), pp 454-462, available at: https://academic.oup.com/jaac/article/75/4/453/5981273

[4] Lian Zhu, Yogesh Goyal, 2018, Art and science Intersections of art and science through time and paths forward, EMBO reports, Science & Society, vol (20), DOI: 10.15252/embr.201847061

[5] Carey Jewitt, Anna Xambo & Sara Price, 2017, Exploring methodological innovation in the social sciences: the body in digital environments and the arts, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol (20), pp 105-120, DOI: 10.1080/13645579.2015.1129143.

[6] Jane Calvert and Pablo Schyfter, 2017, What can science and technology studies learn from art and design? Reflections on ‘Synthetic Aesthetics’, Social Studies of Science, vol (47), pp 195 –215, DOI: 10.1177/0306312716678488.

[7] Pam Burnard, Laura Colucci-Gray, Pallawi Sinha, 2021, Transdisciplinarity: letting arts and science teach together, Curriculum Perspectives, vol (41), pp 113–118, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-02000128-y

[8] Cyrille Rigolot, 2020, Transdisciplinarity as a discipline and away of being: complementarities and creative tensions, Humanities and social sciences communications, 7:100, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00598-5.

[9] Committee for Scientific and Technological Policy (CSTP), 2020, for publication by the OECD Secretariat, OECD science, technology and industry policy papers, Addressing societal challenges using transdisciplinary research.

[10] David Alvargonzalez, 2011, Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity, Transdisciplinarity and the Sciences, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. (25), pp 387– 403, DOI: 10.1080/02698595.2011.623366.

[11] Sarah Robinson, Wesley Shumar, 2014, Ethnographic evaluation of entrepreneurship education in higher education, A methodological conceptualization, The International Journal of Management Education, vol (12), pp 422-432, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.06.001

[12] Stuart MacDonald, Nicola Headlam, CLES, 2019, Research Methods Handbook, pp 51-57.

[13] Rachael Hains-Wesson, Karen Young, 2017, A collaborative autoethnography study to inform the teachingofreflectivepracticeinSTEM, HighereducationResearch&Development,vol(36),pp297–310, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1196653

14

[14] William Cartwright, Anne Ruas, Kenneth Field, 2021, Cartographers write about Cartography, International Journal of Cartography Special Issue, vol (7), pp 119

120, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23729333.2021.1923828

[15] Orpheu 4.0 prototype available at: https://www.flipbookpdf.net/web/site/64f5c866b1165b67d8705078dac9305e49cb4b65202104.pdf.html#p age/1

[16] Anna Jonsson and Maria Grafström, 2021, Rethinking science communication: reflections on what happens when science meets comic art, Journal of Science Communication, 20 (02), DOI: https://doi.org/10.22323/2.20020401.

[17] Melanie Colavito, Barbara Satink Wolfson, Andrea E. Thode, Collin Haffey, Carolyn Kimball, 2020, Integrating art and science to communicate the social and ecological complexities of wildfire and climate change in Arizona, USA, Fire Ecology, 16:19, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-020-00078-w

[18] Simone Athayde, Jose Silva-Lugo, Marianne Schmink, Aturi Kaiabi, Michael Heckenberger, 2017, Reconnecting art and science for sustainability: learning from indigenous knowledge through participatory action-research in the Amazon, Ecology and Society 22 (2):36, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09323220236

[19] Isabel Reche, Francisco Perfectti, 2020, Promoting Individual and Collective Creativity in Science Students, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol (35) no. 9, pp 745-748.

[20] João Carlos Paiva, Carla Morais, Luciano Moreira, 2013, Specialization, Chemistry, and Poetry: Challenging Chemistry Boundaries, Journal of Chemical Education, vol (90), pp 1577−1579, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1021/ed4003089.

[21]FlorbelaPereira,João C.Ponte-e-Sousa, Rui P. S. Fartaria, Vasco D.B.Bonifácio, Paulina Mata, João Aires-de-Sousa, Ana M. Lobo, 2013, Sonified Infrared Spectra and Their Interpretation by Blind and Visually Impaired Students, Journal of Chemical Education, vol (90), pp 1028−1031, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1021/ed4000124.

15

–

Jéssica Jacinto

Figure 1 – The ethnographer’s inner landscape

Figure 1 – The ethnographer’s inner landscape