Untouched… Touched… Scarred

By Tamara Husam Rasoul

Fourth Year

History and Theory Studies Term 1

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Tutor: Teresa Stoppani

Change is something that is constant; as landscapes develop, modernise and redefne themselves, their inhabitants are encouraged to change as well. As the population learns how to adapt in order to survive it often causes traditional practices to be forced aside and replaced by new modern modes of living.1

This interconnected relationship between nature and culture, can be clearly seen through the Bedouin and the desert. The rapid development of the desert around the Persian Gulf, has resulted in a conceptualisation of both the Bedouin culture and identity. In the interests of nation building, governments have sought to settle the Bedouin. 2 3

The deconstruction of the Bedouin lifestyle and identity through sendentarisation and nationalism have led to their 4 representation as ‘an endangered species’ where the smooth and ecological interaction of the Bedouin to the desert has been 5 encapsulated, ruptured and disconnected and replaced by a westernised and interiorised way of life.

Therefore, as hyper-developing countries are constantly changing, redefning and modernising the landscape; where did the Bedouin go? And how have they adapted?

To be able to answer these questions, and understand what has happened to the Bedouin today, identifcation and a historical understanding of who the Bedouin are, where they have been, and how they have inhabited the landscape is vital in understanding their role within today’s society.6

“I said, ‘Your highness, there are still four soldiers in the desert.’ He said, ‘Bedouins!’ As if to say, ‘Don’t be stupid. They are Bedouins. They’ll find their way back.’”

A conversation between Sheikh Zayed and John Elliot, Town planner of Abu Dhabi Conversation 7

“On land and in the sea, our fore-fathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so because they recognised the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations.” - Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan 8

Indigenous people; as a result of their earthbound philosophy, all lightly inhabit the earth. Their respect for the landscape they inhabit, allows them to see the world as a sacred object. The earth not only gifted them with food, life, language and intelligence. But when man died, the earth took him back. Therefore, through wounding the earth, we wound ourselves.9

“Bedouin”, a term derived from the Arabic word “Bedu”, literally translates to “desert dweller”. This term refers to the original people of the desert. Like all other indigenous people, Bedouins are “one” with their landscape and its elements and are loyally tied to their tribal roots and traditions. This respect towards the landscape, defned the light way in which they inhabited the 10 arid desert. Leaving it untouched.

Unlike the way in which cities are inhabited today; rather than living in the desert, Bedouins lived with the desert. They had a deep understanding of their surrounding environment, and did not try to control, redefne and manipulate the landscape. Utilising local resources such as pools of water, palm fronds and fur of the livestock they raised and lived with, Bedouins were able to adapt to the harsh climate of the desert and live alongside it. Contradicting the way in which cities today within such arid landscapes, ignore and control the heat through mechanical means such as air-conditioning.11

(AlRustamani 2014) 8

(Chatwin 1998) 9

(Browning 2013) 10

(Moore 2018) 11

This light manner in which the desert was inhabited by the Bedouins, can also be seen through the temporal and nomadic means of settling. As seasons changed, the areas within the landscape that were inhabited by the tribes changed. Their lives 12 were centred around the need to fnd pasture. Working with the seasonal landscape, they moved with their focks between grazing and watering locations and living in easy dismantled tents woven using wool from their livestock. In the United Arab 13 Emirates, Bedouins were constantly migrating towards the coast in the hotter summer seasons, and moving inland during the winter.14

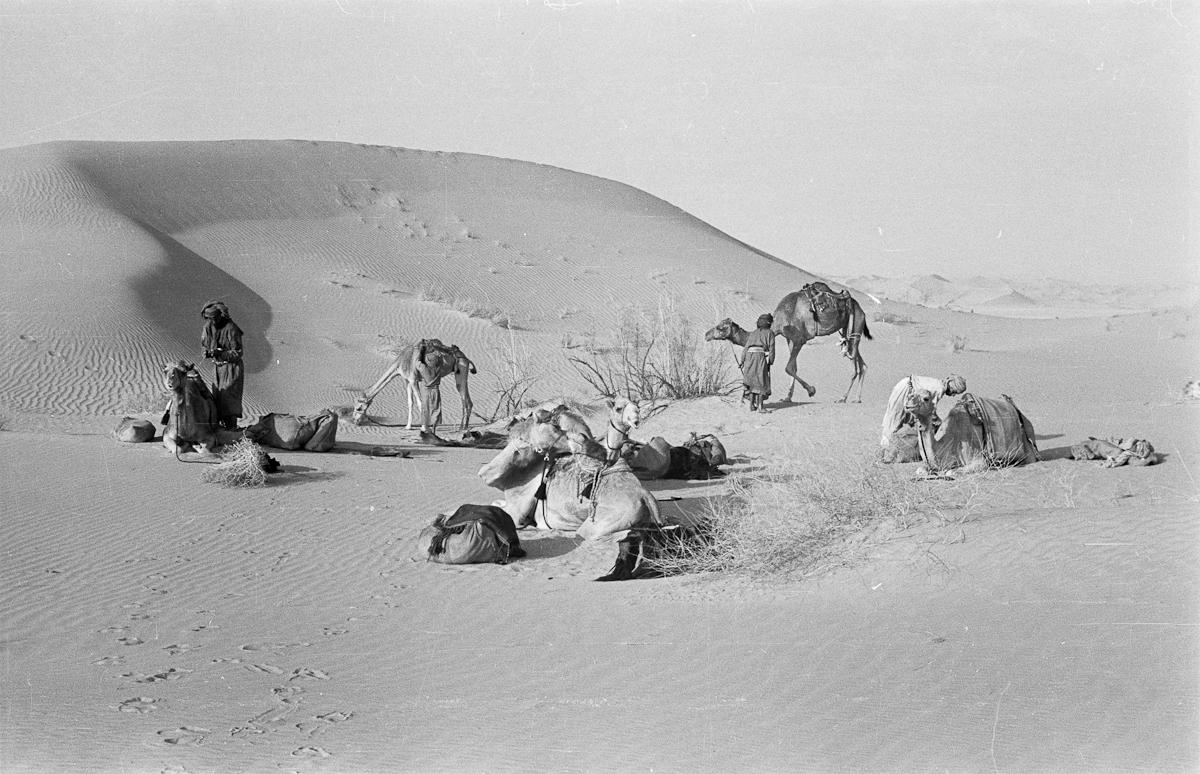

This fuid and untouched way that the Bedouins inhabited the desert can be seen in the picture above. Taken by Wilfred Patrick Thesiger, a British military ofcer, explorer, and writer in February 1950. The image records a moment within the 15 slow travel of the photographers travelling party westwards, where they decided to rest beside a dune in the Ramlatat ar Rabbad sands somewhere in the Al Gharbia Region of Abu Dhabi.16

Even though they inhabited within this landscape, and took from it what they needed to live, the Bedouins respected the desert and valued its preservation. Therefore, the desert remained untouched.

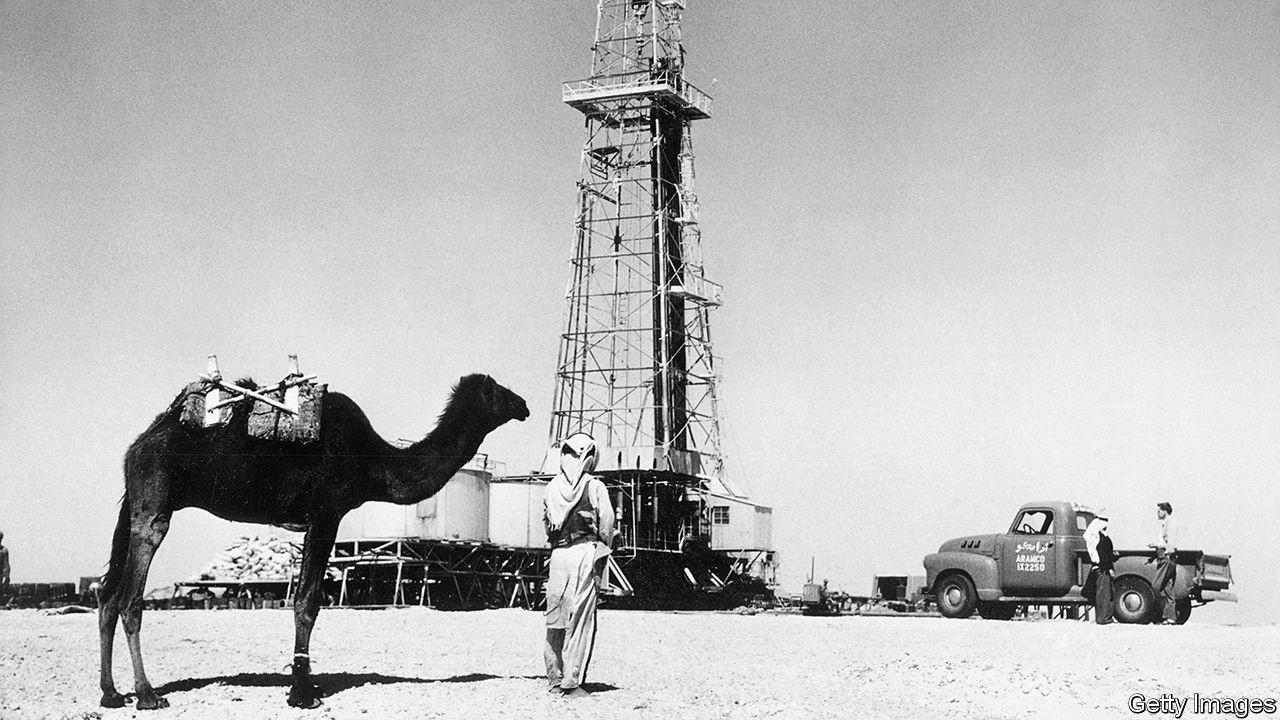

In the late 1960’s, the discovery of oil, led to the hyper-development of many cities and regions within the Persian Gulf.

This hyper-development was evident in cities such as Dubai, where due to the scarcity of oil, they had to plan for its depletion. Through the diversifcation of the economy, the city developed and redefned the landscape from a mud hut town 17 and settlement for the tribe of Beni Yas into a modern city. 18

The modernising of the landscape and development of the city, had concrete efects on the Bedouin way of life. Due to the speed at which the city desired to grow, international input and ‘know-how’ was required in order to develop the large-scale proposed residential developments. Thus, in the haste to provide homes, redefne and develop the country, the consideration for heritage, community and character were lost.19

Both Bedouins, and their Medinas were forced to adapt, transform and westernise themselves at the same pace as the desert was being urbanised. The labyrinthine streets of the Medina, and the temporal modes of living, which once defned the desert, 20 were replaced with static, permanent skyscrapers, neighbourhoods and roads.

These static and permanent structures involved the utilisation of westernised building techniques and materials which began to replace the light weight, small scale, traditional building techniques which utilised local materials such as brick, palm fronds and various animal skins.21

Therefore, with the permanence of structures within the city, the Bedouin was faced with the possibility of settling permanently. Tents slowly started to become replaced by permanent structures, controlled through air-conditioning and walls made from one-way windows. These permanent structures, through the Bedouin tribal layout began to transform into high walled compounds “inhabited by patrilineal extended families, nuclear families or a combination of the two”. Through the

(Koolhaas 2007)

(Prakāsh 2011)

(Koolhaas and Reisz 2007)

(Faroudi 2020)

("Dubai's Evolution: From Desert Oasis To Global Metropolis" 2017)

enclosed layout of the compound, Bedouins were able to preserve the cultural importance of privacy through their high surrounding walls and interiorised layout of the home with a centred patio.22

The permanence of the city, and the reliance of imported design models, conditioned the Western separation of ‘nature’ and 23 ‘culture’ into the urban fabric. This shift from temporal structures to permanent compounds with an internal layout, 24 immediately began to disconnect the Bedouin from the desert.25

The modernisation of the city through the importing of Western housing typologies, disregarded the benefts of traditional design. This has led to the movement of the Bedouin into a more urban setting and has shifted the compact community centric ideals into isolated suburban visions, where the commoditisation of the landscape led to peoples dislocation from it.26

As, culture is something ephemeral and fuid; constantly adapting and changing. The culture of the Bedouin and their relationship to the landscape transformed, evolved and westernised with the development and growth of the modern city and the import of western housing typologies.27

This growth, which was fuelled by the extractivist industry, led to the sustainable, light, untouched way in which the Bedouin inhabited the desert to change. The new evolved landscape of the modern city led to the modernisation and permanent inhabitation of these untouched areas.

Therefore; How did the area of the desert sustain the Bedouin? Where have they gone? Have they ceased to exist?

(Larsen 2017)

(Koolhaas and Reisz 2007)

(Gilbert 2013)

(Browning 2013)

(Koolhaas and Reisz 2007) 26

(Browning 2013)

Today, Bedouin identity remains ambiguous. The restricted and romanticised image of a pastoral desert nomad, dwelling in goat-hair tents, herding sheep, goats or camels is a misrepresentation of the modern bedouin.

Through the development of the landscape, a result of the discovery of oil in the United Arab Emirates, it has redefned the way in which not only Dubai was seen by the world, but also how Dubai saw itself. The city which was frst recorded in 1833 and 28 began as a Bedouin settlement for the tribe Beni Yas of around 800 people, transformed into a multinational modern city 29 with a population of 2.9 million inhabitants. 30

Therefore, the idea of the Bedouin way of life, “represents a general stereotype for Arab culture, but it takes on additional resonance in the Arab Gulf where previously rural and politically marginal tribes have been rapidly transformed into rich and infuential modern nation-states" in which the indigenous population constitutes no more than 20% of the total population and substantially less of the labor force. This was “…alarming to many nationals as they now represent only a small minority in their own homeland….In this changing socio-cultural and economic context the nationals are manifesting in diferent discourses that their local national culture is threatened; they perceive it to be under siege.” Through the rapid 31 transformation, the desert has gone from under their feet.

Nowadays, the Bedouin have become part of the modern city. They have become citizens of states, who carry national identity cards, who vote and are happy leaving their nomadic lifestyles to become part of the productive life of the city. From adopting a pastoral way of living, Bedouins now exist within the city in many diferent forms. They work as taxi drivers, traders or even (Koolhaas 2007) 28 (Saxena 2020) 29 ("Dubai Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)" 2020)

30 (Hawker 2004)

31

government employees. Thus with the modernisation of the landscape, the true nomadic Bedouin who adopts a completely 32 light and ephemeral way of living in the arid climate of the desert has completely died away.33

The defnition of the term “Bedouin” has evolved and dramatically changed during the past century and with the constant development of their context will continue to change. The term “Bedouin” which previously denoted a way of life revolved around a pastoral and nomadic lifestyle, defnes an identity today.34

This identity might appear to be invisible or even as a memory lost though their amalgamation into the collective identity of the nation state. However, elements of their way of living and the characteristics of their pastoral nomadic culture still remain, and are scarred and embedded within their culture. Homes still embrace spatial qualities of the tents, such as the separate entrances for men and women and the social spaces of the home, are still very important in the Emirati home today. Spaces such as the majlis, a social space disconnected from the main home where men sit on the foor and discuss business and family life, resembles the layout and the inhabitation of the Bedouin tents and exist in every Emirati home till this day. 35

Moreover, the Bedouins tie to history can still be read within the urban fabric of the modern city and one can still trace the patrilineal family line of the families of these tribes back several generations. The same family who were Sheikhs of the original tribe, still rule the diferent Emirates within the UAE today. Their ability to remain in the city through their last name, allows their surname to become more than a name but a way in which the identity of the Bedouin can still exist today. 36

Preservation of their identity, goes further than their last name. Through passing on traditions from one generation to another, the bedouins are able to keep their cultural history and preserve their link between the past, the future and the landscape. Therefore, many Emiratis still live with their chickens, goats and sheep and are still involved in farming and planting herbs, fruit and vegetables within their gardens. However, as they are no longer nomadic, a physical dislocation between the landscape and the Bedouins exist and the livestock are kept on farms in the surrounding desert. These animals and crops are no longer intended for sale, but are meant to meet the family’s own needs.37

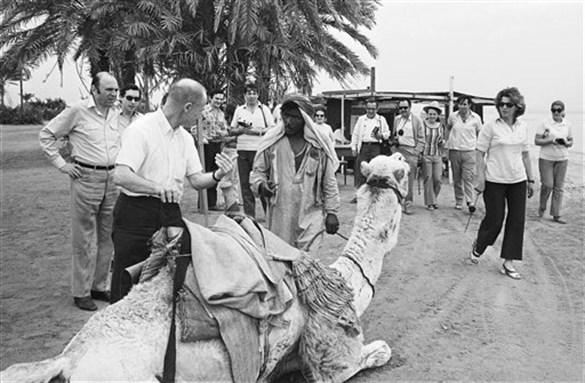

The adaptation and development of the pastoral nomadic role of the Bedouin, is most evident through the transformative role of the camel within the context of the desert. The camel, which some may regard as the most culturally appropriated desert animal, was the most common transport animal used by the Bedouin. However, due to both advancements in technology and within the extractivist industry, their use as transport animals ceased. This led to the commoditisation of camels through racing and tourism. 38

The camel was not the only part of the “image of the Bedouin” which was commoditised by tourism. Today, culture and 39 heritage have become the keys to the tourism industry, where the great hallmarks of Bedouin life, such as camel racing, have still remain a hobby pursued today. This creates an inherent tension to exist between the symbols that are popularly associated with Bedouin life - the tent, the falcon, the camel - with the social and economic reality of the past in the United Arab Emirates. Within the domesticated landscape of the city, which is crisscrossed by highways, dotted with large developments and air conditioned towns, the only tents that remain are domesticated and commoditised. Tents exist underneath the decorative palm trees in the high walled gardens of cast-concrete neoclassical mansions during Ramadan, have been modernised in the form on interiorised majlis’ or are raised temporarily on the edge of the street to host wedding feasts and have become commoditised as a part of heritage districts and desert safaris for tourists.40

Urbanisation, westernisation and tourism has not only redefned the way in which the bedouin live, and how their identity is perceived and commoditised. But has resulted in the redefnition of the landscape where the arid desert has become an

32

(Cole 2003)

33 (Cole 2003)

(Browning 2013)

34 (Browning 2013)

35 (Browning 2013)

36 (Larsen 2017)

37 (Larsen 2017)

38 (Cole 2003)

39 (Hawker 2004)

40

unproductive and uninhabitable space. A space which used to be the most productive part of the city, where Bedouins lived, grew their crops and traded, has become a space simply associated with recreation and enjoyment when untouched. 41 Through technological advancements an modernisation, the desert also became a source of wealth in the form of the development of marketable real estate.42

What does it mean to inhabit the land? Where did the Bedouin go? And how have they adapted?

To inhabit the land, in the perspective of these indigenous cultures is to live with the landscape. In the context of the desert, the Bedouins, even with the seismic phenomenon occurring around them of these highly modernised cities, have continued to live in this untouched and light way.

Their earthbound philosophies have given them the ability to adapt to these new circumstances and changes within the desert. When scanning the extremely westernised landscape of Dubai, a landscape defned through skyscrapers, air conditioners and cars it seems as though the Bedouins and their nomadic means of living have disappeared and no longer exist. What remains of the Emirati culture and Bedouin traditions is exploited within the tourism industry or the privacy of Emirati homes.

However, the Bedouins have never left. They are not lost nor are they invisible. In the words of Sheikh Zayed, the former president of the United Arab Emirates, the Bedouins always “fnd their way back”. Through their fuid and light way in 43 which they inhabit the earth, they have simply evolved with the dynamic urban city. Changes within the city and the way in which people live within this touched, altered and redefned landscape, reveals the changes within their culture and traditions. Therefore, what was considered to be the identity of a Bedouin previously; a nomadic pastoral dweller in the desert, no longer applies to the modern Bedouin in the city today.

Even though when driving through the desert one may not see these dwellers walking through sand dunes with their camels, sleeping in tents and living of the land, the Bedouin identity still exists today. The Emirati culture has accepted the benefts of the modernised city but still preserves a link to their origins and cultural past. These ideologies and beliefs can be seen through the way they still live with animals, farms in patrilineal family layouts where privacy is very important.

The way in which they do so has changed and modernised with the city. Even though today they do not directly live with their animals and are not involved in the pastoral labour involved in farming. They still have farms and still see the importance in agriculture. These farms are no longer part of the home, existing far away in areas in the outskirts of the city. Although a link between the bedouins and the landscape still exists, the physical dislocation between the two has caused the link to become tenuous.

Ultimately, invisibility in the case of the Bedouins, is a relative issue. Before the evolution of the landscape into the modernised city, the bedouins were hidden amongst the sand dunes, not leaving a mark, and living in this very light way. Physically they were invisible. However, today they inhabit the city in a permanent way and they no longer move from oasis to coast. They have become invisible and hidden in other ways. The importance given to privacy in their tribal and religious muslim roots, has rendered them hidden for the untrained eye, where they live behind the high walls of their neighbourhoods. In order to work with this new landscape, the bedouins have adapted and redefned themselves to be able to live with the benefts of the modernised city.

Bibliography:

Books:

Cordes, Rainer, and Fred Scholz. 1980. Bedouins, Wealth, And Change. Tokyo: The United Nations University.

Chatwin, Bruce. 1998. The Songlines. 28th ed. London: Vintage.

Koolhaas, Rem. 2007. Al Manakh. Amsterdam: Stichting Archis.

Koolhaas, Rem, and Todd Reisz. 2007. Al Manakh 2. Amsterdam: Stichting Archis.

Dissertations:

Browning, Nancy Allison. 2013. "I Am Bedu: The Changing Bedouin In A Changing World". Bachelor of Art in Anthropology, 2011, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

AlRustamani, Zainab. 2014. "Impacts Of Climate Change On Urban Development In The UAE: The Case Of Dubai". Masters of Science in Architectural Engineering, United Arab Emirates University College of Engineering Department of Architectural Engineering. https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/all_theses/105

Hawker, R. 2004. "IMAGINING A BEDOUIN PAST : STEREOTYPES AND CULTURAL REPRESENTATION IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED ARAB EMIRATES."

Websites:

Saxena, Kanika. 2020. "The History Of Dubai: Flip And See Dubai Then And Now". Traveltriangle.Com. Accessed October 24. https://traveltriangle.com/blog/history-of-dubai/.

"Dubai Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". 2020. Worldpopulationreview.Com. https:// worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/dubai-population

"Dubai's Evolution: From Desert Oasis To Global Metropolis". 2017. CNN https://edition.cnn.com/2017/03/02/middleeast/ gallery/dubai-evolution/index.html

Faroudi, Layli. 2020. "The Architecture Of Heat: How We Built Before Air-Con". Ft.Com https://www.ft.com/content/ 839d4ccf-269f-44fe-914b-544644a4c819.

Prakāsh, Vikramāditya. 2011. "History Of Dubai". Dubaization. https://dubaization.wordpress.com/op-eds/history-of-dubai/.

"Wilfred Thesiger". 2020. En.Wikipedia.Org https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfred_Thesiger

"2004.130.25471.1 - Photograph Collections At The Pitt Rivers Museum". 2020. Photographs.Prm.Ox.Ac.Uk http:// photographs.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/2004_130_25471_1.html

Moore, Rowan. 2018. "An Inversion Of Nature: How Air Conditioning Created The Modern City". The Guardian. https:// www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/aug/14/how-air-conditioning-created-modern-city.

Journal Articles:

Cole, Donald P. 2003. "Where Have The Bedouin Gone?". Anthropological Quarterly 76 (2): 235-267. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/3318400

Gilbert, Hilary. 2013. "NATURE = LIFE: ENVIRONMENTAL IDENTITY AS RESISTANCE IN SOUTH SINAI". Nomadic Peoples 17 (2): 40-67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43123935.

Larsen, Anne Kathrine. 2017. "Moving Around: How Bedouin Villagers In Dubai Respond To The Challenges Of Urban Expansion". Český Lid 104 (2): 231-246. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26426257

Heard-Bey, Frauke. 2005. "The United Arab Emirates: Statehood And Nation-Building In A Traditional Society". Middle East Journal 59 (3): 357-375. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4330153.

Photographs:

fg.1: Barbara Wace - Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images. 1960. Bedouins With Their Donkeys At A Water Well In The Desert In The Trucial States, Between Sharjah And Manama. The Image Was Likely Taken In The 1950S Or 1960S.. Image. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/bedouins-with-their-donkeys-at-a-water-well-original-news-photo/ 1045495582.

fg.2: Wilfred Patrick Thesiger - Accepted as Art in Lieu of Inheritance Tax by H.M. Government and allocated to the Pitt Rivers Museum, March 2004. 1950. Thesiger's Party Unloading Camels Beside A Dune. Image. http:// photographs.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/2004_130_25471_1.html.

fg.3: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. 1940. Man And Camel Near Oil Well, Saudi Arabia, Circa 1940'S.. Image. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/man-and-camel-near-oil-well-saudi-arabiacirca-1940s-news-photo/629453911?adppopup=true.

fg.4: Associated Press (AP). 1971. An American Tourist Engages In The Highly Necessary Haggling Session With A Bedouin Camel Driver At Sharm El-Sheikh In Israeli-Held Sinai, Egypt On May 10, 1971.. Image. http://www.apimages.com/ metadata/Index/Watchf-AP-I-EGY-APHS381519-Egypt-Rural-Sharm-el-/a4ca913219e14902aa9d9ba6276bb185/1/0.