The Space of Arabic Hospitality

By Tamara Husam Rasoul

Fourth Year

Housing and Urbanism Term 2

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Tutor:

Abu Hurairah (May Allah be pleased with him) reported: Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said: “He who believes in Allah and the Last Day let him not harm his neighbour; and he who believes in Allah and the Last Day let him show hospitality to his guest; and he who believes in Allah and the Last Day let him speak good or remain silent”.1

Hospitality is a central practice and value in Islam. It is a quality that is constantly repeated and emphasized in the records of the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad which are revered or received as a source of religious law, second only to the Qur’an. Defned by the Oxford English Dictionary 2 as “the act or practice of being hospitable; the reception and entertainment of guests, visitors, or strangers, with liberality and goodwill,” hospitality 3 has become a defning feature of many Muslim cultures such as those of the United Arab Emirates. In the UAE, hospitality is seen as an important value not only because of its centrality within Islam but because of its necessity within the harsh arid environment of the desert.4

Therefore, as (in the words of Derrida) “Hospitality is culture itself” and 5 culture is defned by Hassan Fathy as “the result of the interaction between man and his environment when man attempts to satisfy his physical and spiritual needs” and as the city and its built environment is a refection of 6 its inhabitants’ identities and cultures; How has the socio-cultural value of 7 hospitality defined the urban context and the establishment of communities through the development of cities such as Dubai?

Before the development of Dubai into the skyscraper-flled metropolis it is recognized as today, it was frst recorded as a small settlement for the Bedouin tribe of Beni Yas in 1822. The tribe of around 1,200 people; like 8 the Emirati’s who live within the same landscape today, followed a lifestyle defned and built upon Islamic values and principles. As a result, the 9 architecture became a direct refection of these diferent values where the function defned the form.

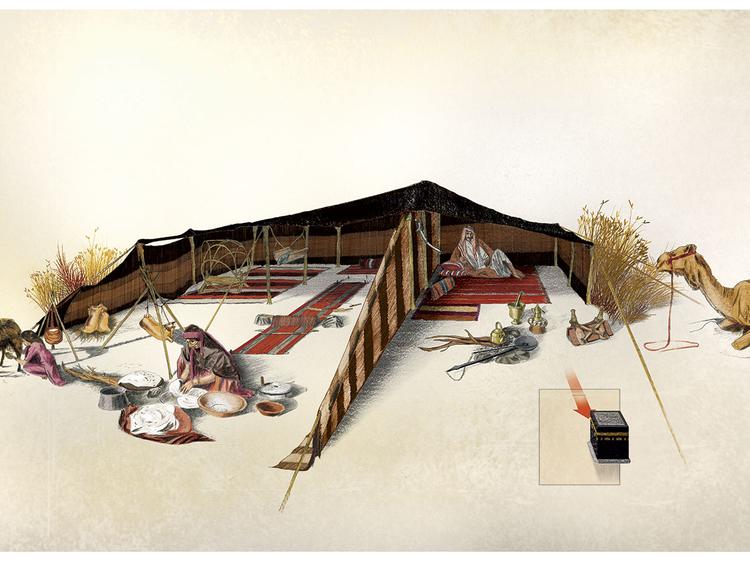

The bedouins; the frst inhabitants of the desert lived in a light and temporal manner. Their nomadic lifestyle meant that their settlements had to be easily built, dismantled and transported. As a result, their urban form was only defned by their tents which were made from the wool of their livestock. Therefore, the home became the only space where the Islamic 10 value of hospitality was translated onto the urban form. As the family represents a micro level society, the way the home is organized and arranged becomes a representation of the culture and civilization of the whole region. In the case of the Bedouin’s tents, the tents were designed based 11 on allowing public interaction; generosity and hospitality while

(Riyad As-Salihin 2021) 1 (Cragg 2020) 2 (Thomas 2013) 3

(Sobh, Belk 2011) 4 (Thomas 2013) 5 (Ibrahim 2012) 6 (Omer 2009) 7

(Gilbert 2013) 8

(AL-Mohannadi, Furlan 2020) 9

(Gilbert 2013) 10

(Lockerbie 2021) 11

(Almahmoud 2015) 12

(Sobh, Belk 2011) 13

(Shyrock 2012) 14

(Sobh, Belk 2011) 15

(Sobh, Belk 2011) 16

(Al Jandaly 2003) 17

maintaining and preserving the privacy of the household. As a result, the 12 tent was unequally divided by a curtain into two distinct spaces. The larger space of the two respected the value of privacy. Known as the woman’s quarters, it held the main living and working area of the family. On the other side of the curtain, the smaller space known as the men’s quarters held the space of the house where the values of hospitality and generosity could be exercised. These spaces were designed in order to ensure the maximum comfort of the guests. Covered with carpets and curtains, they were spaces that were open from morning till evening where cofee and food was always served. These carpets, curtains and warm fabrics which 13 seem to contradict the need for cool spaces within the desert created a cosy and comfortable environment for the guest. In the words of Hajj Salih Slayman al-Uwaydi; “Wherever you found people, their tents were open. Wherever you came to people, there was a mattress, and cofee, and a spike fddle, and poetry… they would say, ‘Peace be with you’. Or they would say, ‘Stay for dinner’, and they would all gather around you, and make a great fuss, and sweat from their efort to please you, and fght for the honour of hosting you…”14

These important spaces, which were a result of the need to create layers of privacy and separate the private spaces within the home from the public spaces led to the design of this typically male-dominated space. These spaces which were the symbol of Arabian hospitality become known as a Majlis. The word Majlis (plural Majalis) is a derivative of the Arabic word “Jalasa” meaning “to sit”. The word Majlis refers to “a place of sitting”.15

For the bedouin, the majlis did not only refer to the part of the home where men could entertain and socialize with other men, exercising the signifcant part of the Arabic identity and culture; hospitality and generosity. But it 16 also referred to a communal space that was not allocated to a particular family allowing all the tribe members to equally exercise the practice of hospitality. Therefore, these communal Majlis spaces, like the tents of the Bedouins were designed with mobility in mind. Made from long thin twigs called subt, which were tightly woven together and held by stouter sticks called amoud, covered with a coarse cloth called al khakis or al untie, these structures could be set up and built in ten minutes whenever it was required.17

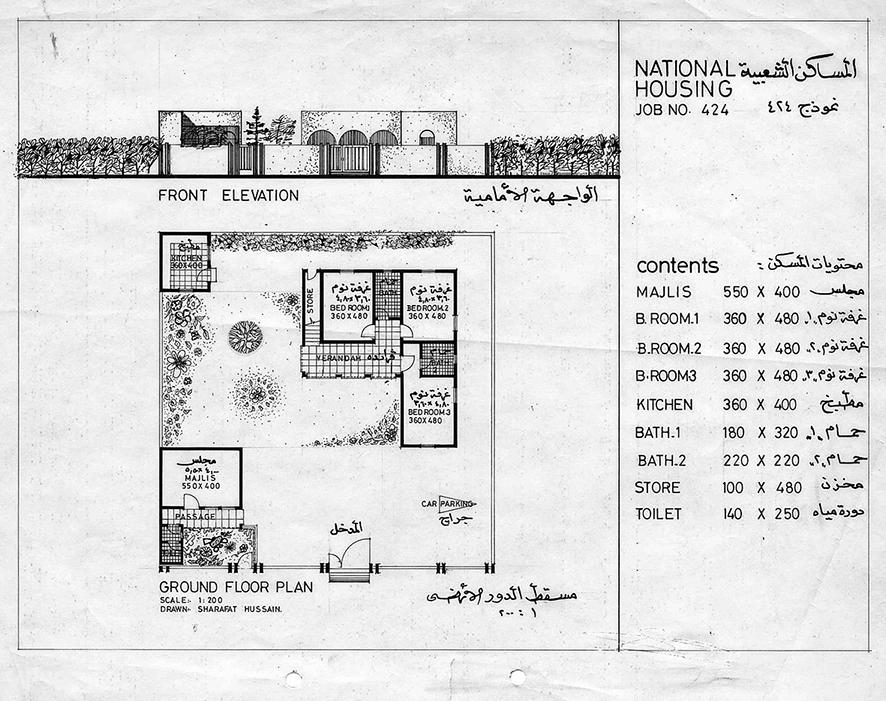

However, after the discovery of oil in 1961 and the formation of the United Arab Emirates in 1971; the importance of these spaces of hospitality became clearer when trying to urbanize and stabilize the Bedouins. This attempt of upgrading the living conditions within the city resulted in the construction of homes known as Emirati Sha’abi homes. Each home adopted an introverted layout where all the rooms faced an open courtyard surrounded by a wall. The homes each had two bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, bathroom and a shower room.

Even though these homes considered the living habits of the Bedouins such as; the decision of these homes to adopt a compound layout; mimicking the layout of tribal tents, their respect to the values of privacy and agricultural needs through the surrounding of the gardens by a fence which blocked external views, the interiorized layout of the homes and the land provisions which ensure that each resident had a plot for agricultural purposes, the values of hospitality were not considered. This led to complaints from the inhabitants as they felt that the homes did not accommodate their local traditions. Most of these complaints were related to the inhabitants’ inability to practice the value of hospitality. In the words of a resident who complained about the Sha’abi homes; the homes were “designed in a poor way that was not suitable for the inherited Arabic tradition.” He continued that the house had only “one bathroom that a man, woman and stranger can use.” The issue with this, he further explained being that this was “not consistent in any way with our values and traditions. We are an Arab Islamic nation and a woman hides behind the veil in front of a strange man in keeping with the Islamic faith.”

Therefore in order to rectify these concerns through aligning the design of the Sha’abi homes with the Emirati values and traditions some modifcations were made. These changes involved the clear demarcation, diferentiation and identifcation of the public and private domains of the household. The main spatial typology which was added to the Sha’abi homes was the Majlis. The additions of these sitting/reception room signifcantly modifed the house from its original form. The room, which was disconnected from the house allowed the practice of welcoming guests and the value of hospitality to be exercised again while maintaining the intimacy and privacy of the family life. Within the homes two types of majlis spaces existed; that for the men and the other for the woman. The male majlis was connected to the outdoor space. While the female majlis, which was smaller in size was connected with the internal spaces of the house.

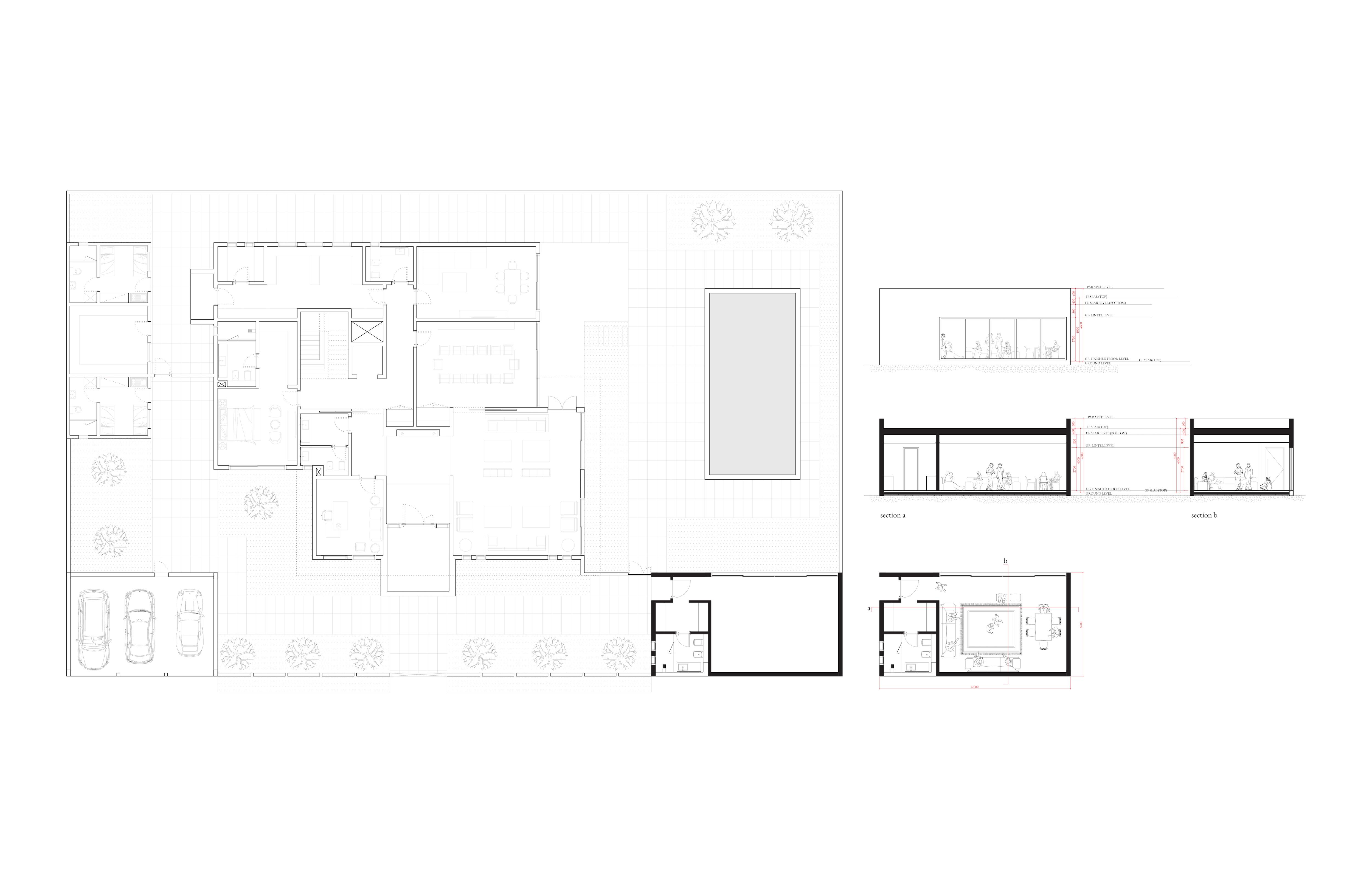

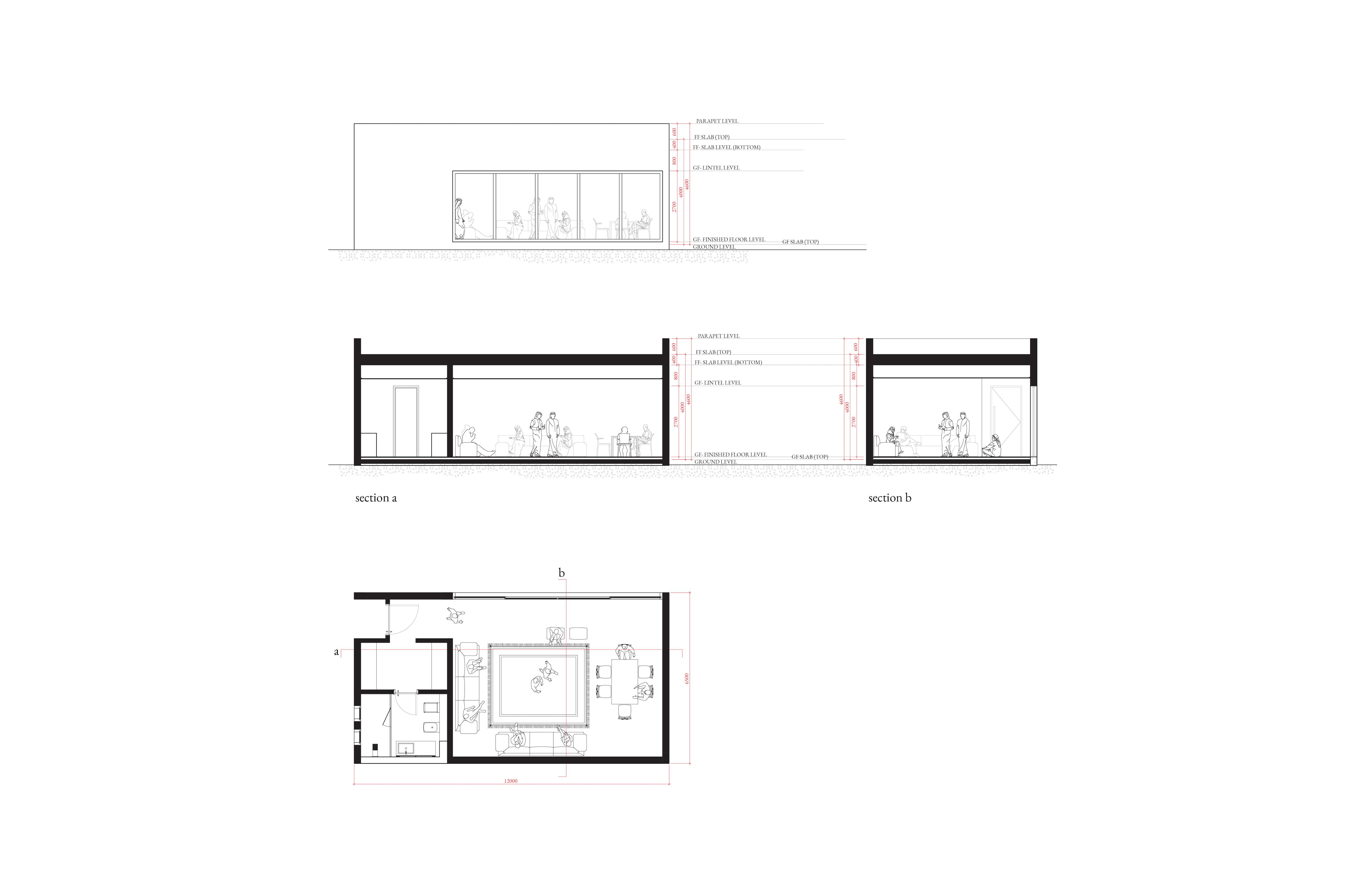

Today, the Emirati home has not changed much. The space of the majlis has retained its importance within the Emirati culture. It can be argued that these spaces represent what Amos Rapoport called the ‘cultural core’. This refers to the elements of a culture that are constant and do not change over time. Thus they constitute an essential part of peoples identity. They are spaces where hospitality can happen and where rituals and traditions such as the burning of incense, the serving or drinking of Arabic cofee and the reciting of traditional poetry can be preserved. Therefore, all villas 18 inhabited by Emiratis will always have a Majlis.

Nowadays, the Majlis exists as an extra room independent to the home where fabrics and textiles still spatiality convey the feeling of comfort attributed to hospitality. However, rather than carpets and pillows, the space is defned through plush upholstered sofas and couches.19

Its strategic relationship to both the villas and the boundary wall defnes both its use and its level of privacy. The most private form of Majlis spaces are those that exist as an extension of the home. This type of Majlis typically has a separate entrance to that of the house but is still accessible directly from the inside of the home. Due to its proximity/attachment to the private spaces of the home, this type of majlis would typically be used as a formalized living room for the members of the family or would be used as a woman’s majlis.

The Majlis can also exist as a dislocated room from the home. It could exist within the boundary walls of the plot. These spaces are typically accessed from within the boundary walls. Their physical dislocation from the boundary makes the way they are placed within the plot very important. This is because their placement should allow visitors to enter with ease without being having clear sightlines to the home. However, the most common type of Majlis space is the one that exists as part of the boundary wall. These spaces become the only part of the property that can be directly accessed both physically and visually from the street. These spaces typically have all of the windows placed towards the exterior in order to ensure the privacy of the domestic part of the home.

Like the Bedouins; the Majlis could also exist outside of the boundary wall, completely dislocated and independent to the home. These are the most public type of Majlis spaces which normally act as a communal living room where ownership may be shared between multiple members of an extended family or group of friends that live in close proximity to each other. (Elsheshtawy 2019)

Moreover, with the development of the city through the paving of streets, densifcation of the city and the technological advancements which have eased transportation within the arid desert environment, the role of hospitality within the Emirati culture has changed radically since the days of the Bedouin. Historically, the Majlis was a space where travelers who were tired after a long journey spread over several days could be immediately welcomed. They were given the best care and invited into the Bedouin tents with open arms. After being ofered “goats milk and dates” and given a place to rest, “they would leave refreshed after spending the traditional three days.” However, nowadays the Majlis has become a reception room where guests drive from their homes stays for a few minutes or a couple of hours then hops back into their car and returns home. As a result, the role of the Majlis as a welcoming space of peace and 20 a temporary home for others has transformed into a purely social space that is used by visitors for a much shorter time period.

Spatially the Majlis has not changed much since 1822. Other than its stabilization through the change of its construction methods and materiality from wooden sticks covered in the wool of animals to cement walls and glass windows, Majlis spaces are still very simplistic in their form. Usually consisting of an empty room with no ornamentation, which sometimes may also include a bathroom and a kitchenette in order to allow guests to be comfortable and maintain the privacy of home. The Majlis still exists as a space defned through the acts of hospitality that take place in it rather than the space itself.

Today Dubai is a city very diferent to the desert that was once inhabited by the tribe of Beni Yas. Through the advances in technology in construction, it has evolved into a cosmopolitan city flled with villas, mansions and buildings. People from all over the world, from many diferent cultures and religions live in the city. Therefore, how have these spaces of hospitality accommodated and adapted to these new guests and the new city?

In the present life of the city, the value of Bedouin hospitality has been used as a marketing tool in order to encourage people to visit, live and work in Dubai. As a result, it has become one of the cities key selling points and 21 values practiced and emphasized by every space within the city. From residential typologies such as tents, villas and apartment buildings to commercial typologies like shopping malls and hotels, hospitality is always given a space to be practiced.

Apartment buildings, for example, the home of many people of diferent social standings within the city, always consider the role of the guest in the

home. The guest is always meant to feel comfortable and at ease, therefore the apartment building always has a communal reception room or lobby as soon as one enters the building on the ground foor. These spaces become a comfortable moment where guests can sit and wait in well tempered airconditioned spaces on an upholstered couch or chair. As the word Majlis means; “place to sit” these moments within the apartment building can be seen as a way in which the space of the majlis has adapted to the apartment building.

Moreover, apartment buildings in Dubai have also been designed with contradicting Islamic values of privacy and hospitality. Therefore, in order to give the space of the fat the same versatility to become a layered space where the private and public realms are clearly defned and separated buildings will have an empty room which like the communal majlis of the Bedouins is shared by all the tenants of the building. This space becomes a space that can be booked out in order to become a space where guests can be entertained and event such as birthday parties or meeting can occur while maintaining the sacredness of the home.

However, within the context of Dubai spaces of hospitality have begun to exist outside of the home. When driving through residential neighborhoods within the city, moments of penetration where infrastructures and acts of hospitality and generosity come out of the house exist. These moments allow the home and the Majlis to open up to the neighborhood through the placement of objects which would typically exist within the boundary walls of the house. As a result, objects such as

fridges, water-coolers, couches and seating areas are a common occurrence outside of homes where people can grab a bottle of water, some food or have a seat in order to cope with the hot and arid environment.

These objects which are either owned privately by inhabitants within the area or are placed by the government, become an extension of Bedouin hospitality. Following the records of a saying by the Prophet Muhammad; “Hospitality is for three days, and whatever he spends on him after three days is charity” Bedouins welcomed guests with open arms. For three days 22 they did not question their guests and simply provided them with a comfortable and nourishing space to rest. These objects which exits along the pavements of residential neighborhoods become a modern translation of this charitable and blind act of hospitality and generosity. Similar to the Bedouins, these moments within the city allow Muslims to practice generosity and become closer to god.

From a touristic point of view, in order to sell the city of Dubai and make it an attractive place to visit, the value of hospitality has been commoditized. Hotels are scattered with couches and seating areas where guests can sit and wait and sometimes are even ofered a date or a cup of Arabic cofee. This can even be seen in shopping malls such as Mall of the Emirates and Dubai Mall where when waiting for your car to be given back to you from the valet you are taken to a reception area to wait. Within such spaces, you are always ofered a date and something to drink like water or cofee.

Therefore, when going back to the question; How has the socio-cultural value of hospitality defined the urban context and the establishment of communities through the development of cities such as Dubai?

One can argue that through the value of hospitality, the city has gone a long way to accommodate its guests despite the many cultural, traditional and religious values that diferentiate them. Today, whenever someone walks 23 into a building, they are still ofered a place to sit, something to drink and even a bite to eat. Therefore, the value of hospitality remains fundamental to life within the Middle East which has had signifcant repercussions onto the urban form. The placement of upholstered furniture and provision of comfort, food and drink has defned the atmosphere and the particular feeling attributed to hospitality which in turn has not only afected peoples

ways of life but has also defned how people meet and interact with one another. This has created a comfortable and laid back society and has slowed down the pace of life within the city.

Consequently, in Dubai a space that does not consider the value of hospitality becomes a space that cannot be lived in. Historically seen through the introduction of the Sha’abi Houses that were deemed uninhabitable without a designated Majlis space. These spaces of hospitality, which began with the Bedouins has transformed, adapted and evolved to exist within every urban form in the city. Whether through the placement of a couch or fridge on the sidewalk, a designated room within the plot of the home or a lobby flled with upholstered furniture in a building, a space within the city is useless without hospitality.

Bibliography

Books:

Buskens, Léon, and Annemarie Van Sandwijk. Islamic studies in the twenty-frst century: transformations and continuities. Amsterdam University Press, 2016.

Claviez, Thomas, ed. The conditions of hospitality: Ethics, politics, and aesthetics on the threshold of the possible. Fordham Univ Press, 2013.

Omer, Spahic. Islamic Architecture: Its Philosophy, Spiritual Signifcance & Some Early Developments. AS Noordeen, 2009.

Wilson, Peter J. The domestication of the human species. Yale University Press, 1991.

Dissertations:

Almahmoud, Shaikha. "The Majlis Metamorphosis: Virtues of Local Traditional Environmental Design in a Contemporary Context." (2015).

Ibrahim, Hanna, "The Contemporary Islamic House" (2012). Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses. 10. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/10

Websites:

Cragg, A. Kenneth. "Hadith." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 5, 2020. https:// www.britannica.com/topic/Hadith.

Lockerbie, John. 2021. "Arabic / Islamic Design". Catnaps.Org. Accessed April 18. http://www.catnaps.org/islamic/design2.html.

"Riyad As-Salihin 308 - The Book Of Miscellany - تامدقلا باتك - Sunnah.ComSayings And Teachings Of Prophet Muhammad (ملس و هيلع لا ىلص)". 2021 Sunnah.Com. Accessed April 18. https://sunnah.com/riyadussalihin:308.

"Sunan Ibn Majah 3675 - Etiquette - بدلا باتك - Sunnah.Com - Sayings And Teachings Of Prophet Muhammad (ملس و هيلع لا ىلص)". 2021 Sunnah.Com Accessed April 20. https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:3675.

Journal Articles:

AL-Mohannadi, Asmaa Saleh, and Rafaello Furlan. "THE SYNTAX OF THE QATARI TRADITIONAL HOUSE: PRIVACY, GENDER SEGREGATION AND HOSPITALITY CONSTRUCTING QATAR ARCHITECTURAL IDENTITY." Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering (2020).

Boussaa, Djamel. "A Future to the Past: The Case of Fareej Al-Bastakia in Dubai, UAE." Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 36 (2006): 125-38. Accessed April 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41223887.

Dluhosch, Eric. "The role of the architect in housing design: Old and new." A| Z ITU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 3, no. 1 (2006): 5-23.

El Amrousi, Mohamed, Mohamed Elhakeem, and Paolo Caratelli. "Reinterpreting Tradition; Hybridization and Vernacular Expression in Emirati Housing." In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 603, no. 5, p. 052045. IOP Publishing, 2019.

Elsheshtawy, Yasser. "The Emirati Sha ‘bī House: On Transformations, Adaptation and Modernist Imaginaries." Arabian Humanities. Revue internationale d’archéologie et de sciences sociales sur la péninsule Arabique/ International Journal of Archaeology and Social Sciences in the Arabian Peninsula 11 (2019).

Gilbert, Hilary. "NATURE = LIFE: ENVIRONMENTAL IDENTITY AS RESISTANCE IN SOUTH SINAI". Nomadic Peoples 17 (2): 40-67. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/43123935. (2013).

Hvidt, Martin. "Public–private ties and their contribution to development: The case of Dubai." Middle Eastern Studies 43, no. 4 (2007): 557-577.

Khoury, Nuha NN. "The Mihrab: from text to form." International Journal of Middle East Studies (1998): 1-27.

Shryock, Andrew. "Breaking hospitality apart: bad hosts, bad guests, and the problem of sovereignty." Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18 (2012): S20-S33.

Salama, Ashraf M. "Urban traditions in the contemporary lived space of cities on the Arabian Peninsula." Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 27, no. 1 (2015): 21-39.

Sobh, Rana, and Russell Belk. "Domains of privacy and hospitality in Arab Gulf homes." Journal of Islamic Marketing (2011).

Stephenson, Marcus L. "Deciphering ‘Islamic hospitality’: Developments, challenges and opportunities." Tourism Management 40 (2014): 155-164.

Online Articles:

Abdella, Amir M. "Globalizing Dubai: Transience, Dwelling and Hospitality Tensions.”

Al Jandaly, Bassma. 2003. "Symbol Of Arabian Hospitality". Gulfnews.Com https://gulfnews.com/uae/symbol-of-arabian-hospitality-1.355463.

Barnes, James. "Bedouin’hospitality in the neo-global city of Dubai’." EInternational Relations (2013).

Reisz, Todd. "As a Matter of Fact, the Legend of Dubai." Log 13/14 (2008): 127-137.

Shams, Ammar. (2017). "The Majlis: Emirati Culture Exists - Just Look Closer". The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/arts-culture/the-majlisemirati-culture-exists-just-look-closer-1.4506.

Photographs

fg.1: © Al Ittihad Newspaper. 1977. Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan Meeting With Sheikh Rashid Bin Saeed Al Maktoum On Sir Bani Yas Island. Image. https://www.agda.ae/en/catalogue/na/na/0042/00000353.

fg.2: Barros, Jose Luis. 2016. Layout Of A Typical Bedouin Tent. Image. https:// gulfnews.com/entertainment/arts-culture/know-the-uae-life-under-thetent-1.1915952.

fg.3:© Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority (TCA). 2003. Outdoor Majlis Spaces. Image. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/majlis-a-cultural-andsocial-space-01076.

fg.4: ADCO. 2021. Image From The Late 1960S In Abu Dhabi Showing The Final Stages Of Constructing A Sha‘Bī House.. Image. Accessed April 10. http://journals.openedition.org/cy/docannexe/image/4185/img-4.jpg.

fg.5: Ministry of Public Works. 2021. A 1974 Plan Illustrating One Of The Typologies Developed By The Ministry Of Public Works.. Image. Accessed April 12. http://journals.openedition.org/cy/docannexe/image/4185/img-11.jpg.

fg.6: Tamara Rasoul. 2021. Drawing of Modern Majlis Spaces in Dubai

fg.7: Johnson, Delores. 2013. Mubarak Al Qusaili And Family, Inside Their Tent. Tent Decorum Dictates That Anyone Is Welcome At Any Time, Without Advance Notice.. Image. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/tents-in-thecity-keep-uae-s-bedouin-heritage-alive-1.276014.

fg.8:A&A Engineering Contracting L.L.C. 2019. Lobby of Residential Building In International City, Dubai. Image. https://www.anaec.ae/pf/gp6-residentialbuilding-in-international-city-dubai/.

fg.9: Tamara Rasoul. 2021. Images of water-coolers and furniture outside homes in Dubai.

fg.10:Mall of The Emirates. 2019. Complimentary Arabic Coffee While You Wait For Your Car At Mall Of The Emirates.. Image. https:// www.facebook.com/MallOfTheEmirates/photos/ a.145442732176321/1928754547178455/.