Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre(s)

Art Vault, Santa Fe

The Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation

June 2025September 2025

Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre(s)

June 2025 – September 2025

Art Vault, Santa Fe

The Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation

June 2025September 2025

June 2025 – September 2025

Art Vault, Santa Fe

At the core of Richard Mosse’s solo show at Art Vault is a gripping presentation of the Thoma Foundation’s recent acquisition from Mosse, Broken Spectre: a captivating, 66-minute film documenting the intensive deforestation of the world’s largest rainforest in the Brazilian Amazon. The work highlights, on intersecting scales from the microscopic to the monumental, the agents and victims of the unfolding ecological catastrophe in the Amazon basin. In just the last fifty years, mass deforestation has wiped out about 20 percent of the original Amazon rainforest, the largest tropical rainforest in the world. In 1975, only one percent of the original forest had been lost to human resource extraction. Today, ongoing deforestation is leading to species extinction, unpredictable and extreme weather patterns worldwide, and global warming.

Broken Spectre resists categorization—Mosse employs a visual language that enlists and reinvents the strategies of photojournalism, scientific documentation, resource mapping, and cinema verité. To uncover the systemic environmental attack on the Amazon, Mosse films aerial scenes with a specially designed multispectral video camera, mirroring the technology of remote sensing satellites used by environmental scientists and mineralogists. Narratives on a human scale are exposed in ethereal glowing monochrome of 35mm anamorphic black-and-white infrared film. The non-human is unveiled using ultraviolet microscopy, showing the vast biodiversity found in just a few square inches on the forest floor. Created in collaboration with virtuoso art cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and set to a powerful score by renowned experimental composer Ben Frost, the film is both incredibly stunning and profoundly unsettling.

A comprehensive selection of large-scale photographs by Mosse complement the film, along with a special presentation of Grid (Palimi-ú), a work from 2023 comprising two interacting elements: footage shot on 35mm infrared film that documents protest speeches by Yanomami leaders who had fled for safety to aldeia Palimi-ú, a village in Northern Brazil, and multispectral photogrammetry captured by drone over extractivist fault lines and sites of environmental crimes. This film offers a heartbreaking glimpse into ground-level community-led resistance and solidarity, rallying against the industrial gaze of multinational and corporate profit. Ben Frost’s intense score is comprised of ultrasonic recordings of rainforest beetles, bats, and other lifeforms.

In this current historical moment, it is essential, and especially poignant, to see nature through the lens of artistic expression. Broken Spectre(s) invites us to embrace this experience and welcome its inspiration as we are reminded of our relationship to the natural world—not only as spectators but also as stewards.

Broken Spectre was co-commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, VIA Art Fund, the Westridge Foundation, and by the Serpentine Galleries. Additional support provided by Collection SVPL and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Exhibition Credits

Director / Producer

Richard Mosse

Cinematographer / Editor

Trevor Tweeten

Composer / Sound Design

Ben Frost

Digital Colorist / Post-Production

Jerome Thelia

Production Manager

Matthew Warren

Film Processing Advisor

Cary Kung

Film Processing Assistant

Kimin Kim

Film Scanning

Metropolis Film Lab

Fixers / Translators

Gabriel Bogossian, Alejandro del Solar

Bravo, Alessandro Falco, Marco Lima, Gabriel Uchida

Production Assistant

Diana Morales Ocegueda

and intersecting scales from the microscopic to the monumental, the invisible constituents that are victims of the ecological catastrophe affecting the Amazon basin. Over the last fifty years, mass deforestation, willfully carried out by millions of people, has wiped out more than one-fifth of the original forest. This chimerical audiovisual installation leaps dramatically in scale and media to create a visceral and emotional connection with the world’s largest rainforest, the world’s last great reservoir of biodiversity, being devastated on multiple fronts for corporate profit.

Mosse employs a visual language that appropriates, conflates, and reinvents the strategies of photojournalism, scientific documentation, resource

the systemic environmental attack on the Amazon, Mosse films aerial scenes with a specially designed multispectral video camera, mirroring the technology of remote sensing satellites used by environmental scientists and mineralogists. Narratives on a human scale are exposed in ethereal glowing monochrome of 35mm anamorphic black-and-white infrared film. The non-human is unveiled using ultraviolet microscopy, showing the vast biodiversity found in just a few square inches on the forest floor. Created in collaboration with virtuoso art cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and set to a powerful score by renowned experimental composer Ben Frost, the film is both incredibly stunning and profoundly unsettling.

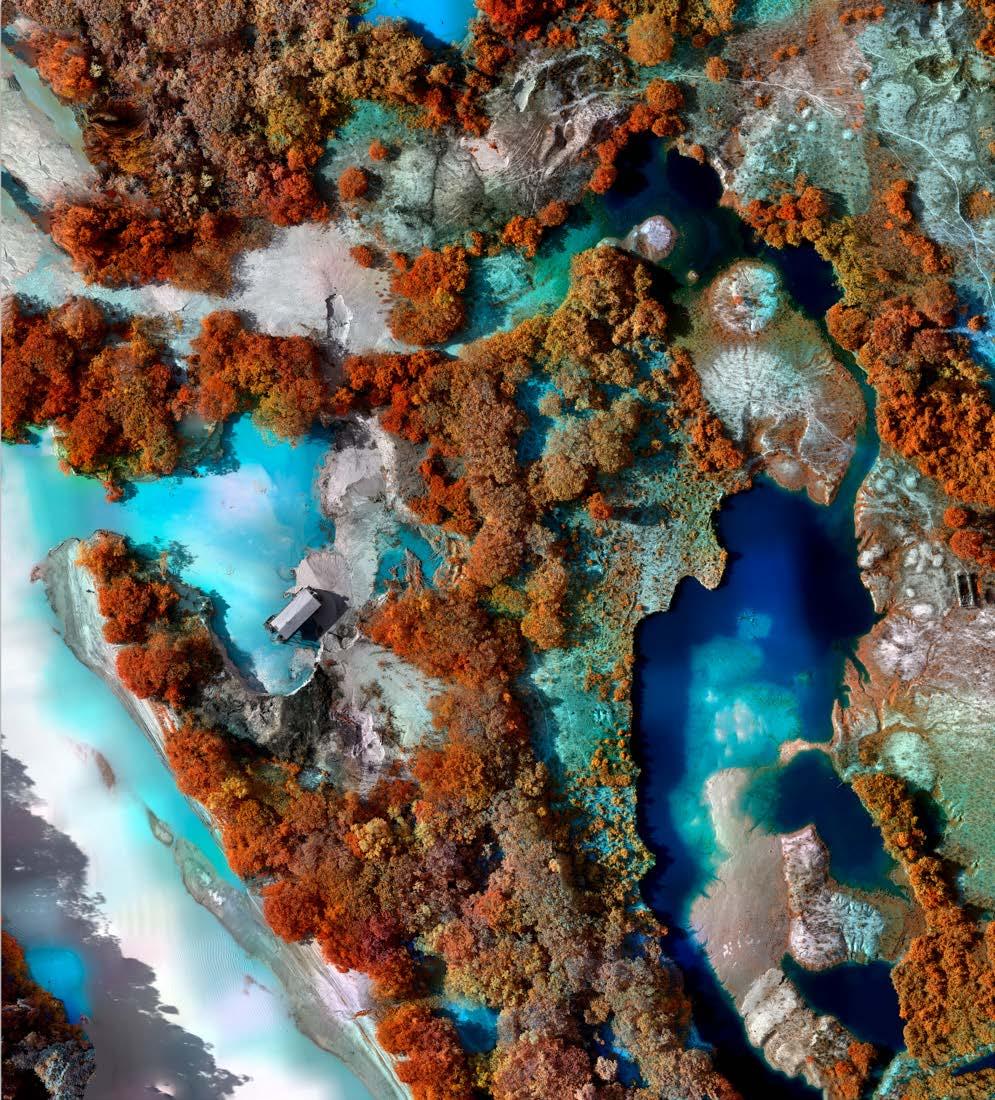

Grid (Palimi-ú) brings together two contrasting elements: footage shot on analogue infrared 35mm film that documents protest speeches by Yanomami leaders who had fled for safety to aldeia Palimi-ú, a village in Northern Brazil, and multispectral photogrammetry captured by drone over extractivist fault lines and sites of environmental catastrophe. The grid displays multispectral images captured by a drone flying above sites of environmental crimes in the rainforest in plantations, cattle ranches, and mining sites. Mosse calls this the ‘God’s eye view’ that simultaneously carries the inherent extractive violence

of aerial survey mapping and the scientific potential of remote sensing, which helps us understand the extent of the crisis in the Amazon Basin. These images contextualize the film footage of the protest speeches.

Since the 1990s, illegal gold miners have been invading Yanomami ancestral land with lethal consequences to both human and non-human life. Caught in the multidisciplinary tension between apparently objective topographic imaging and emotionally charged, eye-level confrontation, the viewer is left to piece together a narrative from the fragments provided.

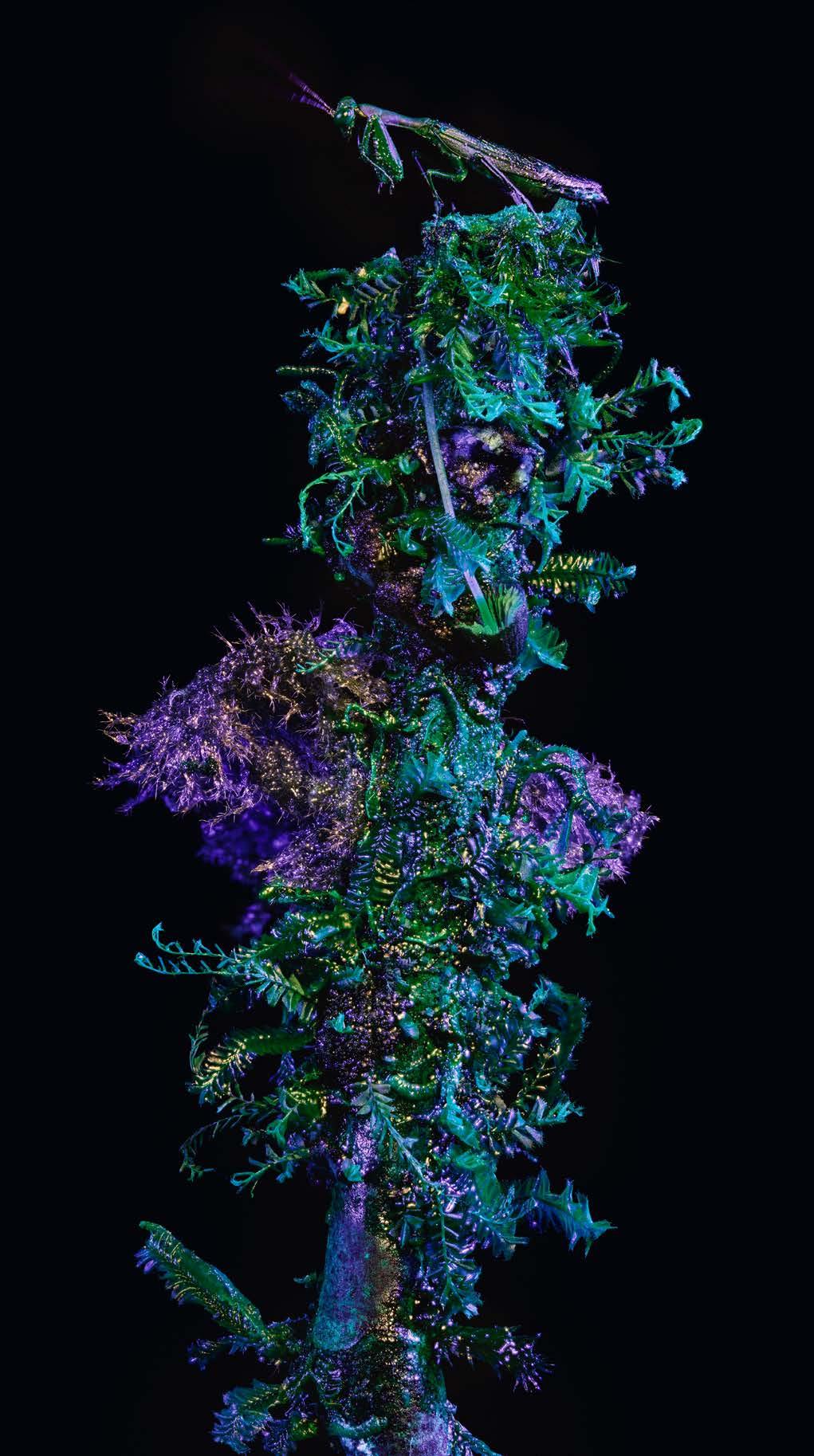

Fronds, Dead Lichen, and Tiny Mantis, Llanganates-Sangay Ecological Corridor, Ecuador, 2019. Digital c-print mounted to Dibond

Ultraviolet microscopy showcases the bristling biodiversity found in just a few square inches on the forest floor.

Lily, Llanganates-Sangay Ecological Corridor, Ecuador, 2019. Digital c-print mounted to Dibond

A lily fluorescing under UV light. This photograph was taken at night.

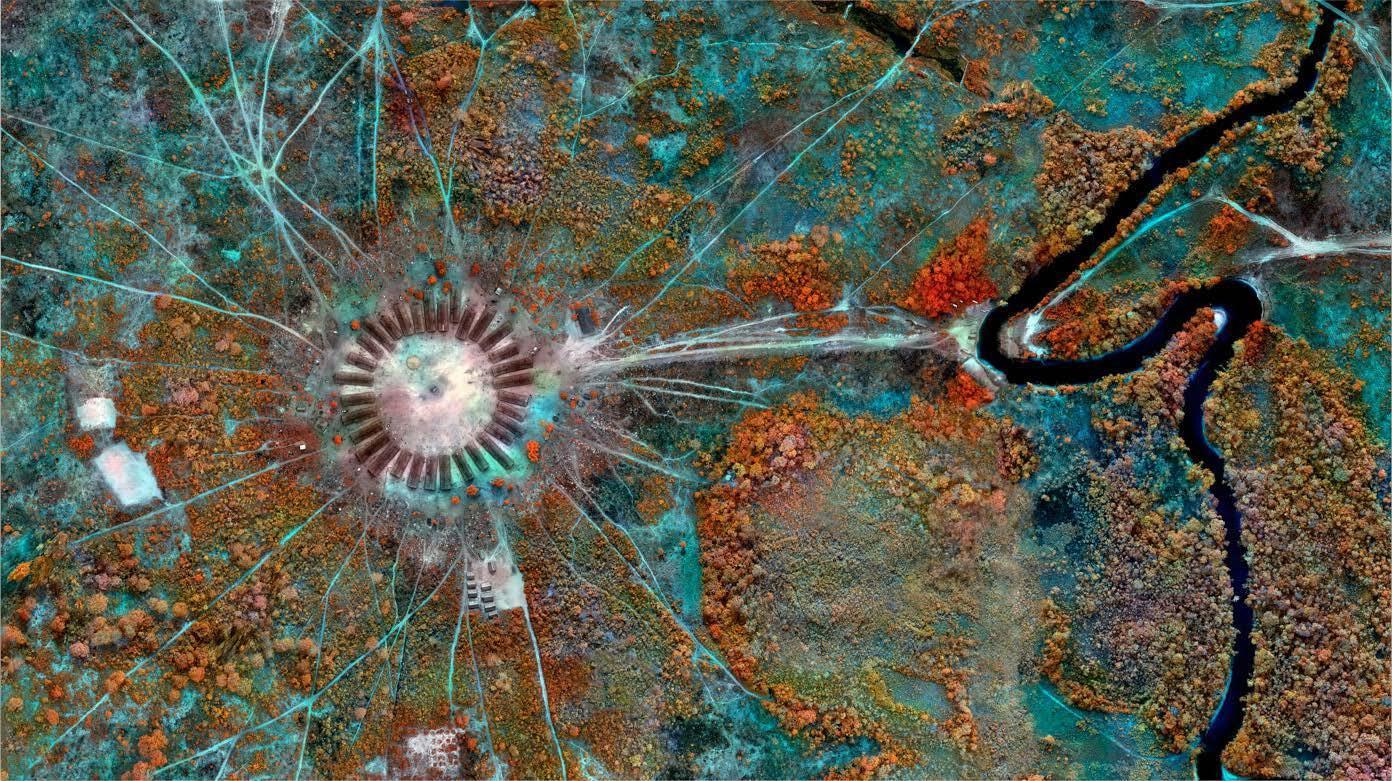

Halataikwa is the village (aldeia) of the Enawenê-nawê, a recently contacted community of Indigenous people. The Enawenê-nawê live in a cyclical, sustainable relationship with their environment. Every few decades, they will move their aldeia to a different location to allow the surrounding forest to rejuvenate. Abandoned former aldeias, long overgrown, can be seen from space as circular formations in the forest. In recent years, their fish supplies have greatly diminished due to hydroelectric damming of the river.

Not long ago, they had to import frozen fish from the nearby town of Vilhena for the first time in their history. The Enawenê-nawê are pescatarians and do not eat red meat. Fish are also central to their spiritual beliefs. Reaching Enawenê-nawê by land during the dry season is difficult, but it is often impossible during the rainy season, when access must be done by boat. Power lines arrived in their aldeia for the first time only very recently, which may impact their culture and society.

Burnt Pantanal III, Mato Grosso, 2020. Archival pigment print

Forest dieback caused by recent fires to clear pasture land near Rio São Lourenço in the Pantanal Wetlands.

A typical sawmill in the Amazon Basin where illegally felled wood is laundered with quantities of legally certified timber. In this image, more intense blues indicate freshly harvested wood, while the paler blue, yellow, or white sections denote older timber. According to research, 95–98% of timber harvesting in the Amazon is a precursor to forest clearance and conversion to ranch and pastureland. One of the most prized neotropical hardwoods is ipê, which commands extremely high prices on international export markets, particularly in the United States, driving illegal and unsustainable harvesting in remote forests, such as those in Rondônia.

A moving car, driving into the sawmill, is depicted as truncated, an artifact created by the drone’s movements and the orthographic stitching software. The car’s truncated hood can be seen in one area and its body in another. The coloring in this image illustrates the age of the felled wood. The more intense blues indicate recently harvested wood, while the paler blue and yellow/white sections denote wood cut down less recently. You can also see traces of blue and yellow sawdust from milling these respective logs. The hazy quality of this photo is due to the fact that it was taken at dusk. Because of the illicit nature of the sawmill, Mosse had to work covertly.

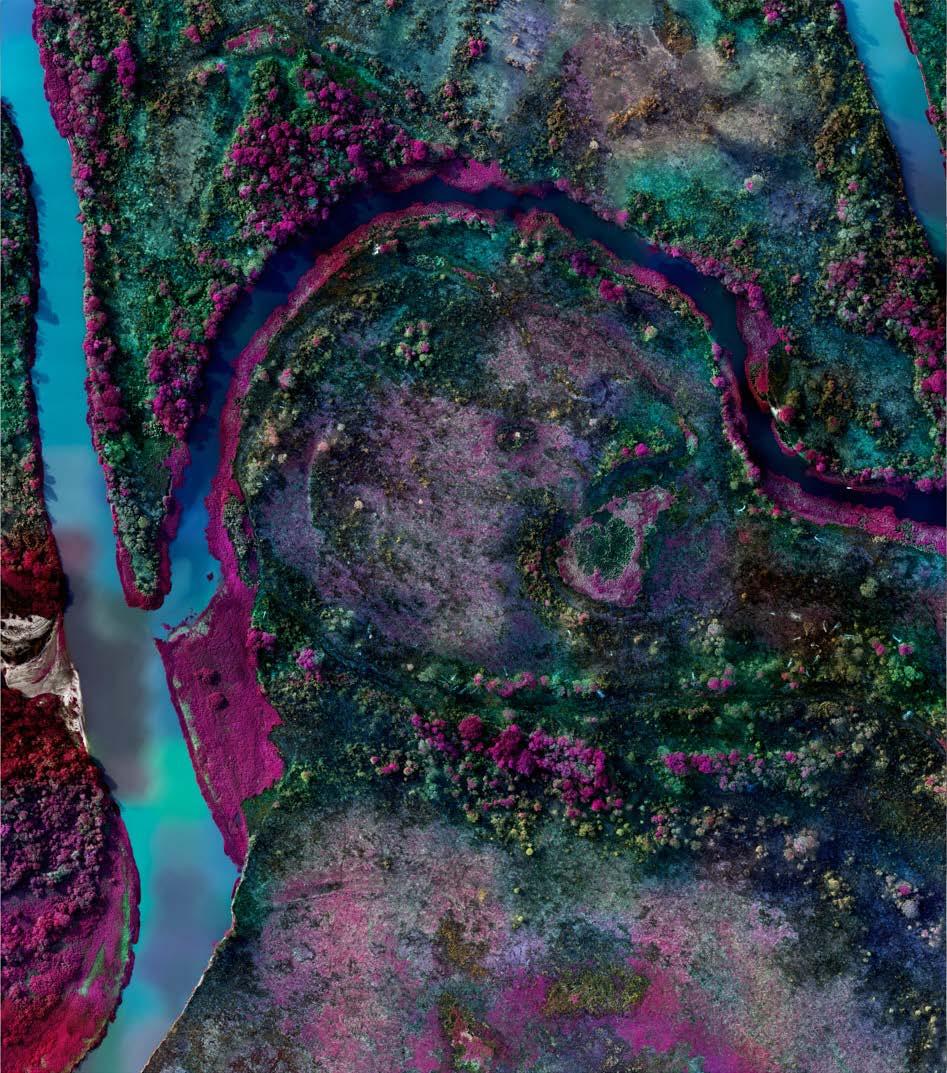

This multispectral map shows the extent of recent fires in the river system of the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetlands. The Pantanal is a vast and extremely biodiverse ecosystem, the size of several European nations combined. Parts of it are designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, but 95% of the Pantanal is owned privately by cattle ranchers, who often burn the forest during the dry season. Because the dry season has become so long and extreme in recent years, the fires have become virtually unstoppable, wiping out vast areas of the Pantanal

and massive amounts of wildlife. The map employs Geographic Information Systems (GIS) techniques to reveal environmental damage. The blood reds and vibrant purples indicate healthy foliage, while the paler purples and pinks indicate degradation and forest dieback. However, the burn was so recent that most of the colors (green, brown, white, and black) represent dead foliage. In certain areas, the ashen traces of mature trees, thoroughly burned, are evident as white outlines on the black charred earth, like ghosts.

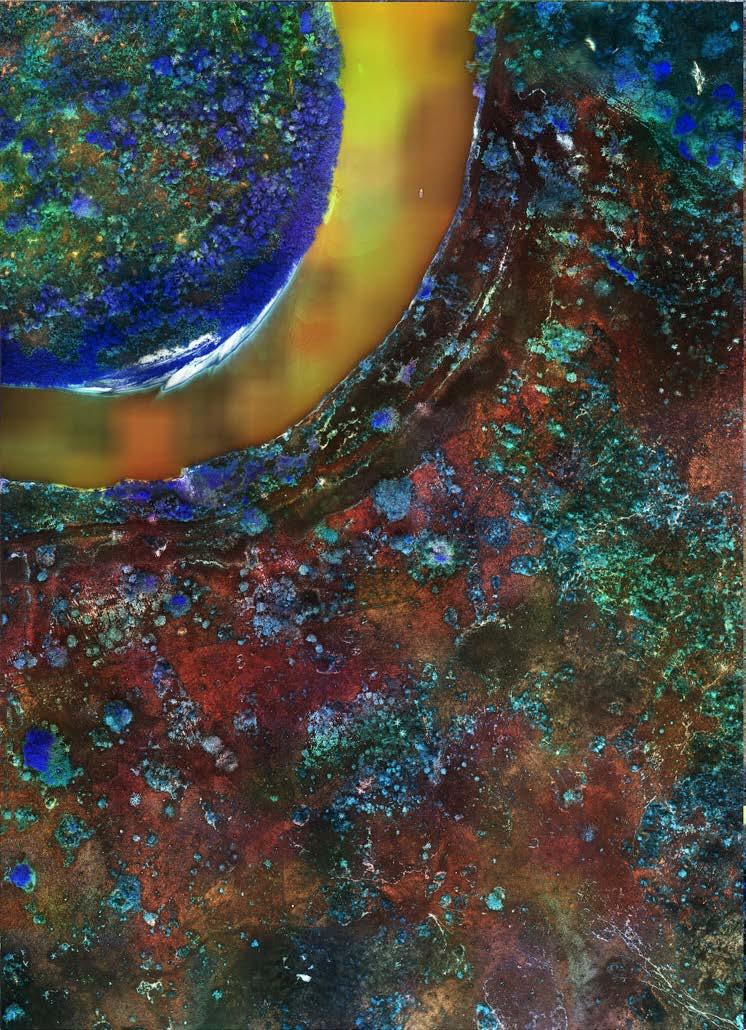

This GIS (geographic information systems) map shows extractive violence created by a mineral ship dredging silt drawn from the bed and banks of the Crepori River. Mercury is used to separate gold dust from the silt in sluice traps aboard the boat.

Some of this dust enters the river system, poisoning aquatic life and all who live off it, including Indigenous communities. One side of this river is a protected national preserve and home to the Munduruku people.

Illegal goldmines (garimpos) cluster along the banks of the Crepori River. Mineral ships dredge and filter the riverbed to extract gold. Mercury separates gold from silt, some of which flows into the river system, poisoning all life forms that depend on the river, including Indigenous communities, such as the Munduruku, who live along

this river. This is a GIS (geographic information systems) map of these activities made using a multispectral camera attached to a drone flying at an altitude of 90 meters. The camera captures wavelengths used in mining and agribusiness to exploit the rainforest.

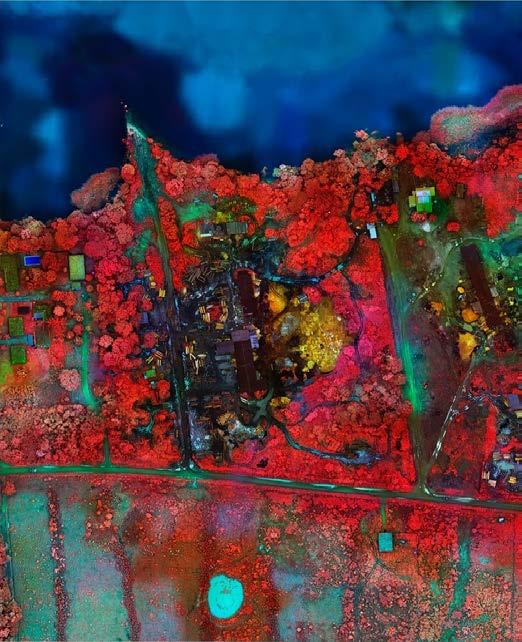

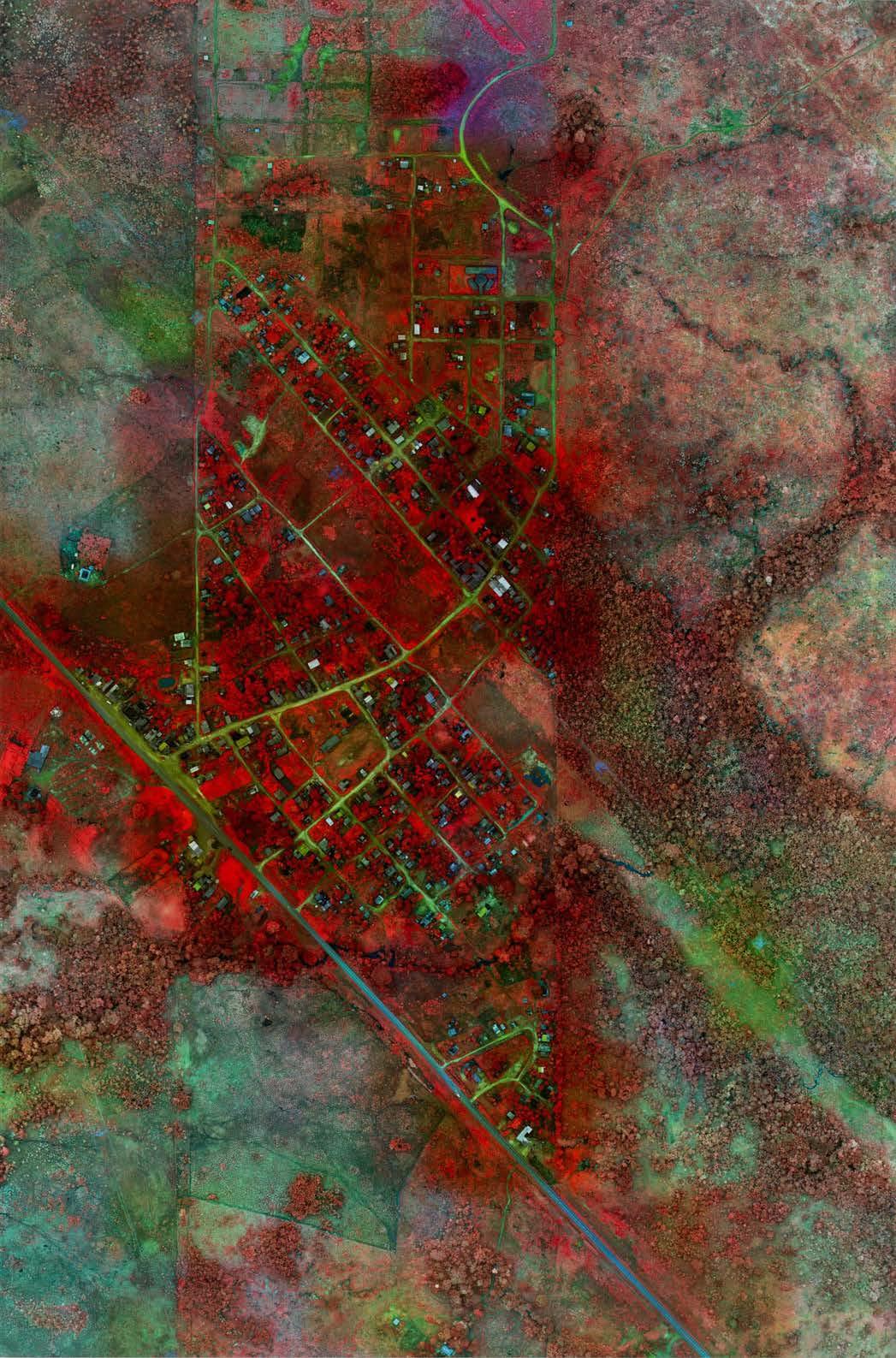

The town of Senador José Porfirio, known locally as Souzel, lies on the Xingu River. This extremely biodiverse river is a major tributary of the Amazon River and home to numerous Indigenous tribes and communities. Souzel is comprised of many sawmills that process vast quantities of tropical hardwoods culled from the rainforest, almost all of it illegally. With military support, IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental protection agency, raided the town of Senador José Porfirio only a few days before this map was made. Fiscal

penalties were made, but they are never properly enforced and rarely paid. A luxury residence with a pool and private jetty can be seen situated between two sawmills at the center left of the map, an example of the profits enjoyed by some involved in the illegal logging industry. José Porfirio de Souza (1912–1973), after whom the town was named, was a leader of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), a militant Communist movement. He disappeared during the years of the Brazilian military regime.

Vila Isla in Anapu on the Trans-Amazonian Highway, Pará State, is regarded as one of the tensest parts of the Brazilian Amazon. Violent land grabbing is widespread and there are frequent confrontations between Indigenous people, small colonist land holders, organized land grabbers. The notorious narco cartel PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital) is also present in Anapu.

An American activist nun, Dorothy Stang, was assassinated in 2005 for organizing people against land grabbers in this area.

She is widely regarded as a martyr. Each year, there is a three-day memorial walk in this area, attended by thousands of activists and environmentalists who walk in her memory.

The event has become a stand of Leftist solidarity against Bolsonarista environmental criminals and is increasingly popular with younger generations who wish to save the Amazon. Some travel great distances to attend, in an attempt to raise awareness of ongoing deforestation in the state of Pará and beyond.

This multispectral GIS map shows the abandoned infrastructure of an oil plant built by Occidental Petroleum on Kichwa Indigenous Territory in the mid1970s, allegedly without their consent. This infrastructure was abandoned fifty years later in 2015. Yet, the corroding pipes were never maintained or dismantled, and numerous oil spills and toxic swamps have begun to appear, contaminating the forest and rivers with heavy metals. Details from this map show abandoned oil storage tanks that

have leaked crude oil. Kichwa workers have been employed by the national oil company, PetroPeru, to clean up contaminated earth into plastic bags, which can be seen in piles. GIS mapping techniques are being used in recent studies by a university in Ecuador to geolocate toxic oil spills along this forgotten, degraded oil pipeline, which runs thousands of kilometers through the forest to the Pacific coast. A clean-up operation is necessary, costing hundreds of millions of dollars.

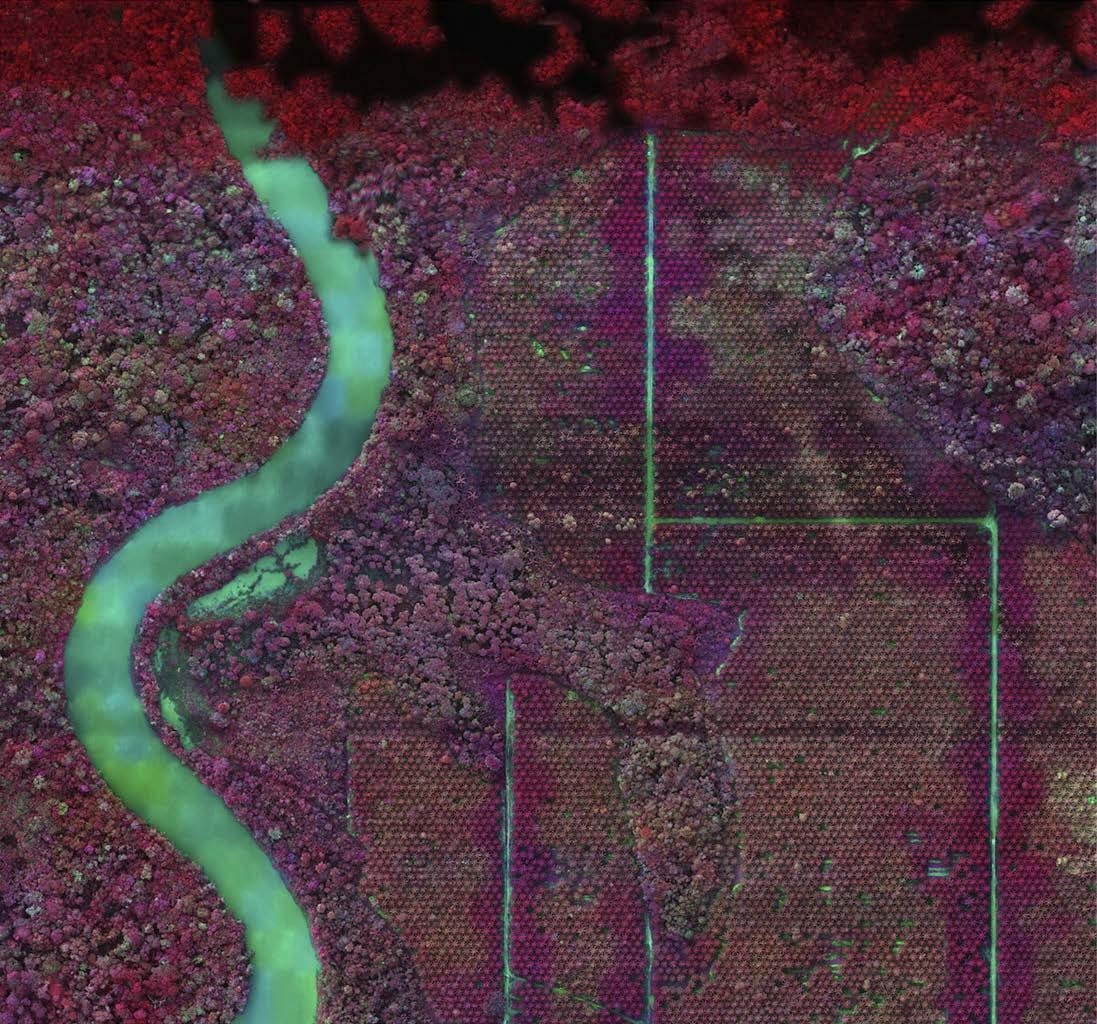

Palm plantations are the single biggest driver of rainforest destruction globally, replacing the rainforest’s extraordinary biodiversity with the monoculture of intensively farmed palm trees for palm oil used in soap, food additives, and other products. This palm plantation is near Tomé Açu in Pará State. In this region, land is stolen from Indigenous territory and extractivist communities

for large-scale agribusiness. The rectilinear lines of the planned palm forest encroach on the natural rainforest. The black and red pattern at the top of the image indicates nightfall, when the multispectral camera and the orthographic stitching software struggled and failed to image the terrain below.

These stills were taken from sequences in the film Broken Spectre that were captured using a custom-made multispectral video camera that the artist designed and built for this project. The camera emulates Vegetation Index imaging techniques used by agribusiness and industry to exploit the environment more profitably and by scientists to predict tipping points and understand invisible signs of ecological degradation. The artist captured three narrow bands of light at wavelengths of 645 nanometers (remapped as blue), 700 nanometers (remapped as green), and 750 nanometers (remapped as red) to create a false color image from the near infrared that indexically reveals a great deal about the forest’s health. XIII shows a vast industrial mine. XIV shows intensively farmed soybean fields alongside recently burned primary forest, with the frontier of the original forest in the foreground. XV shows the River Uraricoera inside

Yanomami Territory in Roraima State on Brazil’s northern border with Venezuela.

Historically, Yanomami Territory experienced a gold rush in the late 1980s, with more than twenty thousand garimpeiros illegally raiding and extracting from Yanomami Territory in those years. This led to the Haximu Massacre of 1993, in which a large group of armed garimpeiros murdered sixteen Yanomami people. Following the Massacre, the Brazilian Army carried out operations to remove garimpeiros from Yanomami Territory. The Supreme Federal Court eventually ruled the Massacre an instance of genocide. Because of the soaring price of gold on global markets, garimpeiros have now returned in the same numbers to plague Yanomami Territory, bringing with them malaria, STDs, and other diseases, while pressing vulnerable recently contacted Yanomami to work in their mines for low pay.

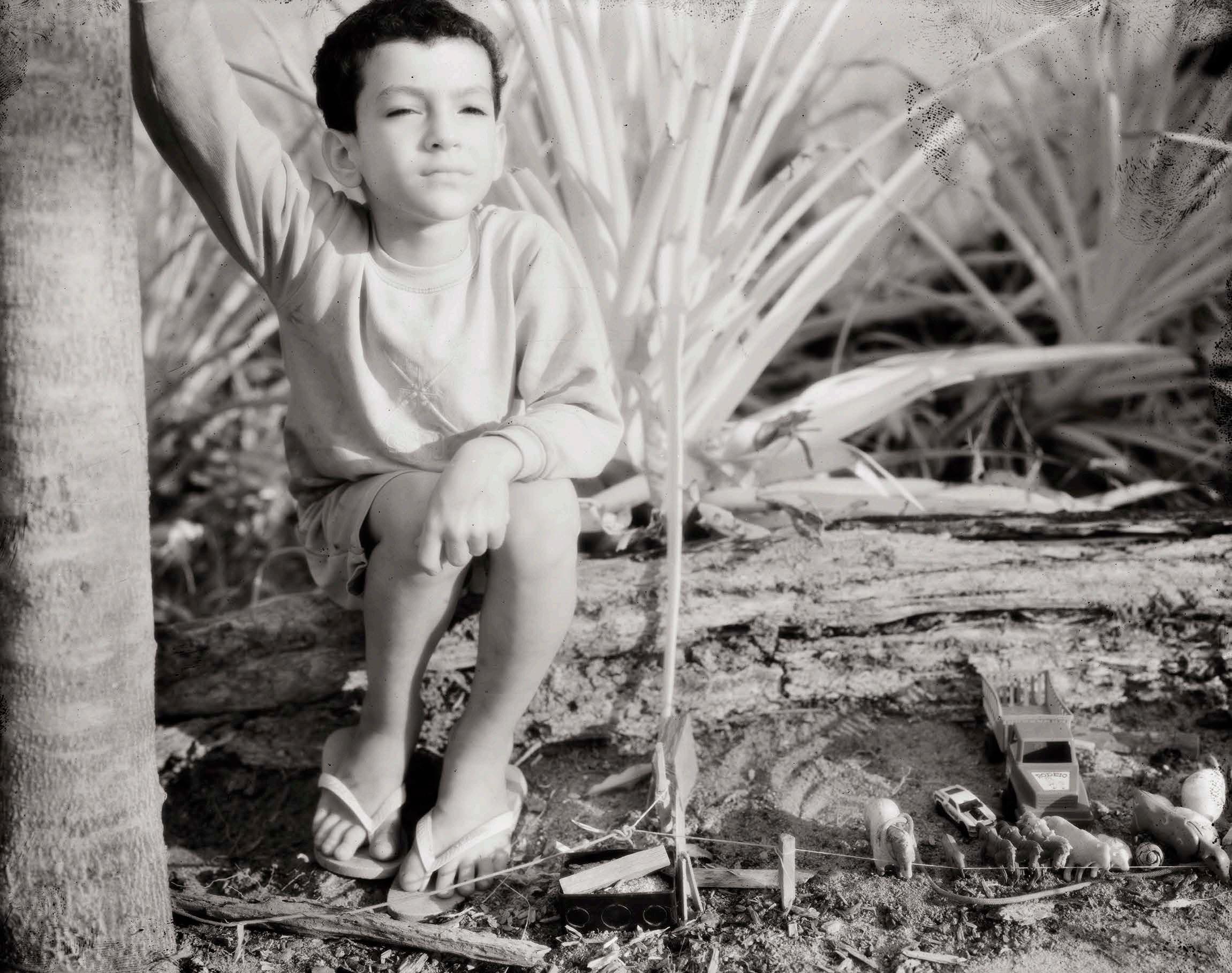

A child with farming toys sits on land recently cleared from primary forest to build a fazenda (Brazilian plantation). Such fazendas are reached by roads that encroach into primary forest in a ‘fishbone pattern’ development. These fishbone roads are so extensive that they can be seen from space.

José Bernardo and his family feature in Broken Spectre. The artist visited them

over three successive years at their smallhold colonist farm near Apuí in Amazonas. This land was, until recently, pristine rainforest, but it is rapidly becoming cattle country, so it is on the frontline of deforestation. Deforestation was brought to this region by the Transamazónica, a highway that the Brazilian military dictatorship began building in the early 1970s.

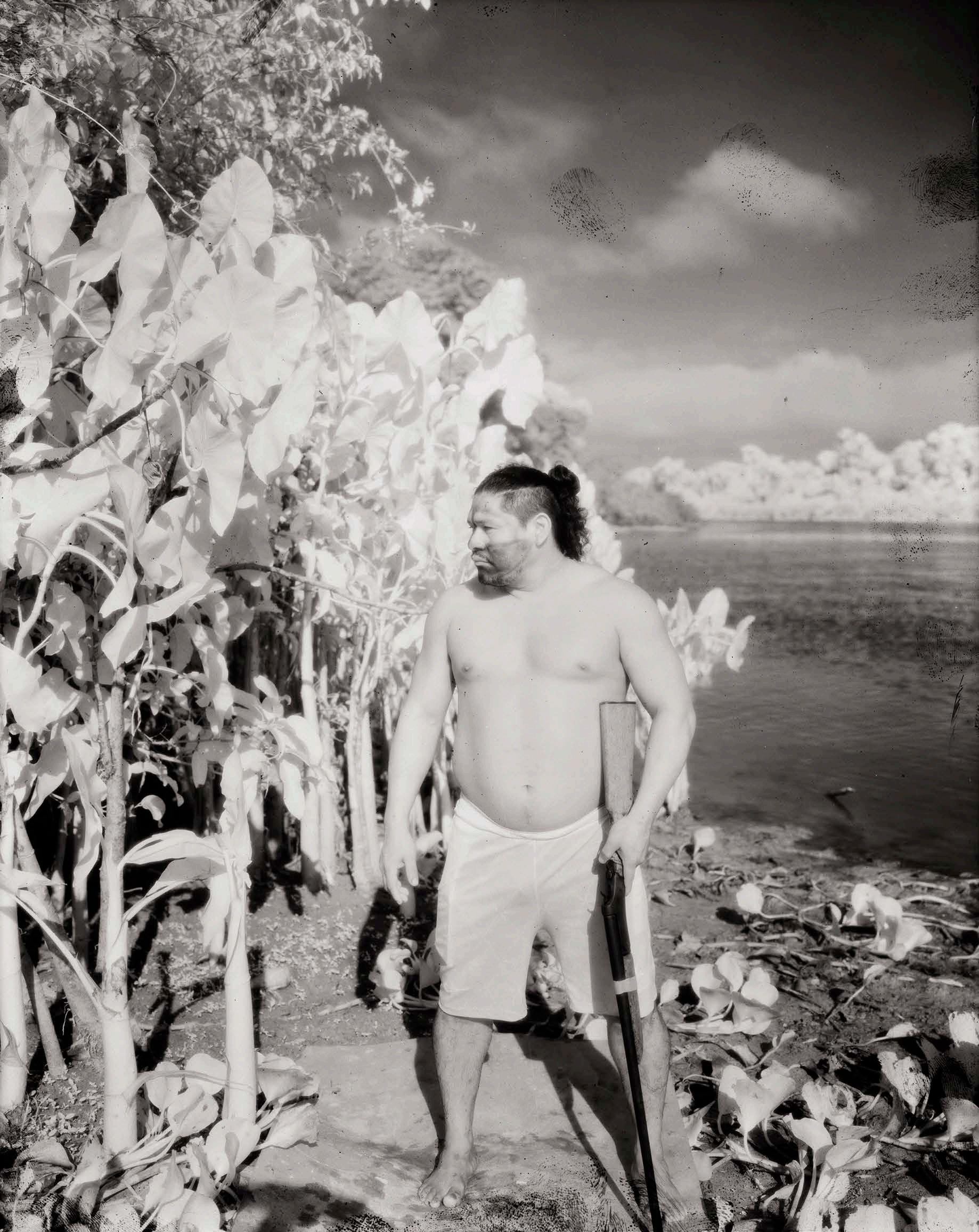

Anderson Painhum Munduruku, Pará, 2021. Silver gelatin analogue print on fiber paper with gold toning

A member of the Munduruku community stands with a shotgun on the banks of the River Tapajos in the Floresta Nacional de Itaituba II. Feeling abandoned by the Brazilian government, the Munduruku have had to defend their ancestral territory against illegal encroachment from hydropower, industrial farming, and gold mining.

A young garimpeiro (gold miner) poses for the camera with a gold pan near the garimpo settlement of Creporizão. At the end of the week, each garimpeiro is usually given a small amount of the residue gathered in the mine’s traps as part payment for his

labor. José is extracting gold from this allowance. Sometimes it is worth just 50 Brazilian reais, but other times much more. For many garimpeiros, this element of luck adds a gambling psychology to the enterprise.

Man has cultivated the Amazon rainforest since prehistoric times, domesticating certain plants such as palm trees without razing other

lifeforms, a biodiverse method of gardening that stands in stark contrast to the monoculture of modern agribusiness.

Recently burned forest in Amazonas. The emulsion of Kodak HIE high-speed infrared film, used to take this photograph, is especially sensitive to heat and humidity. Environmental effects can be seen in the materiality of the film itself.

1

Broken Spectre, 2018–2022. Single-channel digital video installation (color, sound). 66 minutes, 54 seconds. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. 2

Grid (Palimi-ú), 2023. Two-channel digital video installation (black and white, sound). 32 minutes. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation.

3

4

Fronds, Dead Lichen and Tiny Mantis, Llanganates-Sangay Ecological Corridor, Ecuador, 2019. Digital c-print mounted to dibond. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Lily, Llanganates-Sangay Ecological Corridor, Ecuador, 2019. Digital c-print mounted to dibond. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

5

Burnt Pantanal I, Mato Grosso, 2020. Digital c-print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. 6

Burnt Pantanal III, Mato Grosso, 2020. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

7

Aldeia Enawenê-nawê, Mato Grosso, 2020. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. 8

Sawmill, Rondônia, 2020. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Crepori River, Pará, 2020. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Mineral Ship, Crepori River, Pará, 2020. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

12

13

14

15-16

17

18

19

20

21

For Dorothy Stang, Anapu, Pará State, 2021. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York .

José Porfirio, Rio Xingu, Pará, 2021. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Palm Plantation, Pará, 2021. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Abandoned Oil Plant Infrastructure, San Jacinto, Block 192, Loreto, Peru, 2022. C-print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Stills from Broken Spectre XIII, XIV, XV, Rondônia, 2022. Digital c-prints. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

José Bernardo Santana Ribeiro, Amazonas, 2021. Silver gelatin analogue print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Anderson Painhum Munduruku, Pará, 2021. Silver gelatin analogue print on fiber paper with gold toning. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

José with Pan, Pará, 2020. Silver gelatin analogue print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Domesticated Palms, Amazonas, 2019. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Burnt Forest I, Amazonas, 2019. Archival pigment print. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Based in Dallas, Texas, the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation collection includes over 2,000 works and spans four broad fields: Art of the Spanish Americas, Digital & Media Art, Japanese Bamboo, and Post-War Painting & Sculpture. In addition to exhibiting our collection at our two free gallery spaces, Art Vault in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and our Cedar Springs Headquarters in Dallas, the Foundation has loaned over 2,200 artworks to more than 250 exhibitions worldwide. We make a concerted effort to share our collection with the public, conserve the works in it, and provide documentation and research that puts each piece into a more widely understood context. We award individual grants and fellowships to support original scholarship across our collection areas, supporting research, symposia, and equity in the arts. Our grants for nonprofit organizations help fund innovative exhibitions, academic programs, and collection-related publications.

In 2024, the Foundation launched the Thoma Scholars Program to help broaden access to higher education for promising rural students in the rural American Southwest. Working with our university partners, the Thoma Scholars Program is a comprehensive scholarship that helps talented students graduate with as close to zero debt as possible. Beyond financial support, the Thoma Scholars Program gives high-achieving students a path to promising futures through mentorship, educational support, and leadership training.

This catalogue was produced in association with the exhibition Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre(s). at Art Vault, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Our Team

Director and Curator, Media Arts

Kathleen Forde

Associate Curator, Art of the Spanish Americas

Verónica Muñoz-Nájar

Collections Manager

Meagan Robson

Santa Fe Art Spaces Director & Exhibitions Manager

Kathleen Richards

Collections Assistant

Rachel Lewis

Graphic Designer

Sophie Ross

Communications Coordinator

Madison Spencer

Edited by Rachel Lewis and Madison Spencer