Volume 1 | Number 2 | 2025

Legacy Founder

Dr. JamesA. Johnson

Chief Editor

Dr. Brian L. Matthews

Higher Education and Research Commission Chair

Texas A&M University-Texarkana, U.S.A

Editorial Peer Reviewers

Dr. Brian L. Matthews

Higher Education and Research Commission Chair

Texas A&M University-Texarkana, U.S.A.

Dr. Michelle Fennick

Lamar University, U.S.A.

Dr. Jeffrey Miller

Dallas College, U.S.A.

Dr. Queinnise Miller

University of Houston-Clear Lake, U.S.A.

Calls for papers are announced annually and guidelines are featured in the Dr. JamesA. Johnson Research Institute Proposal.

© 2025 TABSE Research Journal. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent of its editors. Requests for permission should be sent to its editors.

ResearchArticles

Audit culture: High school teachers' perspectives on following required practices and protocols in professional learning communities

Black girls deserve to be girls:Acomparison of school-based social and emotional practices on the impact of discipline rates ofAfricanAmerican middle school girls

Reclaiming the humanity of students:Aholistic path forward during a mental health crisis

Exploring middle school core content teachers’perspectives of implementing social

Dismantling barriers: Exploring perceptions, challenges, and strategies for recruiting and retainingAfricanAmerican male leaders in K-12 schools

Magis……………………………………………………………………………………

Editorial Statement

Annually, TABSE Research Journal (TRJ) seeks to publish completed research papers submitted to the Dr. James A. Johnson Research Institute during the annual TABSE State Conference that address diverse challenges facing and present findings that benefit students of African descent and educators who serve them at the K-12 and post-secondary levels in the State of Texas and afar. We consider “value-added” papers with diverse topics, framings, methods, and resolutions that reflect this range and are open to papers with a developed problem statement, perspective(s) or theoretical framework, methods and procedures, results and conclusions, and the educational or scientific importance of the study We also consider TRJ an effective tool in reaching a broader audience in hopes of effectuating positive change throughout the state and nation.

More specifically, TRJ encourages papers, empirical or conceptual in nature, that test new theories, re-imagine existing studies, explore interesting phenomena, and innovate a mixture of methodologies that scaffold specific hypotheses and research propositions in the education

field. TRJ supports papers that bolster educational achievement, educability, adequacy, dignity, worth, equity, and quality education.

As a peer-reviewed journal, we periodically screen for scholarly reviewers. TABSE Research Journal (TRJ) is dedicated to advancing research and practice across K–12 and higher education. We publish empirical studies, theoretical analyses, and applied research that explore critical issues in teaching, learning, leadership, equity, policy, and innovation across educational contexts. Peer reviewers should be experts in specific areas of education such as curriculum development, inclusive pedagogy, or educational leadership such to maintain the academic rigor and relevance of our publication. We ask that reviewers have obtained a master’s or doctoral degree in education or a related field, possess expertise or research experience in K–12 or higher education, have published in peer-reviewed academic or professional journals, have experience in the use of current APA style guidelines, and are able to provide reviews within 2–3 weeks of assignment. If you are interested in being a reviewer, please contact TRJ Chief Editor, Dr. Brian Matthews, at bmatthews@tamut.edu for consideration.

Erin Bradley

TABSE Research Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2024

Introduction

Received January 14 2024

RevisedApril 1 2024

Accepted May 27 2024

Research has considered the classroom teacher one of the most impactful influences on student learning. Hattie's meta-analyses of global research studies found that teacher influences of credibility and clarity have an effect size of 0.90 and 0.75, respectively (Hattie, 2009).

Nevertheless, No Child Left Behind (2001) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) have transformed the paradigm of teaching and learning by emphasizing standardized testing and compelling school leaders to enforce policy-driven initiatives and strategies to improve instruction. According to Gonzalez, Peters, Orange, and Grigsby (2016), these guidelines rely upon standardized testing to determine student proficiency in state standards and serve as the framework for mandated policies at the state and local levels intended to improve teaching and learning. Researchers have suggested that policies intended to improve instruction through mandates alter teachers' dispositions, reduce autonomy and professionalism, and create audit cultures (Lee & Lee, 2018; Philpott & Oates, 2016). Audit culture is defined as customary practices in which policies are implemented based on performance (Smith & Benavot, 2019).

Professional Learning Communities (PLC) in schools leverage teacher partnerships. The

© Written by Erin Bradley. Published in TABSE Research Journal. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and author(s).

PLC model, framed by Richard DuFour in the 1990s, was developed involving staff members in the collective inquiry process while supporting continuous growth through collaborative practices (Dufour, 1999). The PLC model has influenced educational policy such as Chapter 149 of The Texas Administrative Code (2014) which maintains that teachers are responsible for actively collaborating with peers and other key stakeholders with the aim of improving practice through professional learning opportunities and reflection. In the current climate where teachers must contend with emerging policies affecting instruction, teachers play an integral role in policy implementation since dispositions control actions and outcomes (Lee & Lee, 2018; Skourdoumbis, 2018). Studies have indicated that required PLC practices and protocols diminish a clear vision and shared decision-making which both are essential for transformational change in organizations (Smith & Benavot, 2019). Additionally, practices devoid of consistent protocols can produce unintended consequences as in Philpott and Oates' (2017) study findings where teachers lacked clarity regarding the planned PLC outcomes. If a common leadership goal is to improve instruction, how do teachers perceive the audit culture phenomena in PLCs?

RQ1: What are the experiences of high school teachers in how required PLC practices and protocols influence planning and instruction?

Agrowing body of research has emphasized PLC effectiveness based on collaborative practices and a gap in the literature revealed the need for further exploration of teachers' perceptions of following required practices and protocols that contribute to audit culture. Driven by initiatives from top-down leadership, Philpott and Oates (2016) asserted that a barrier to transformational change of teachers' practices in PLCs was due to "audit activity". Thereby

making the industry a place where "largely absent in discussions of quality or accountability are the voices and views of those who work, learn, and teach in schools" (Smith & Benavot, 2019, p. 195). Moreover, audit culture in education has increasingly restricted risk-taking and autonomy for teachers in planning and delivering instruction. Teacher insights were needed to inform policymakers and educational leaders of what teachers viewed as limitations to transformative change in an environment of increasing accountability.

Theoretical Framework or Perspective(s)

This study drew upon Neoliberalism. Bureaucrats originally introduced this theory to reduce state involvement in citizens' lives (Rasco, 2020); however, Neoliberalism evolved to impact every political, economic, and social sphere, including education. According to Philpott and Oates (2016), outside examination of teachers' PLC practices undermined the synergy and professionalism needed to produce impactful outcomes for student achievement effectively. Smith and Benavot (2019) purported that authoritarian approaches to mandated policies, devoid of diverse stakeholder input, eroded trust in the system. Consequently, Neoliberalism in education creates challenges for sustainable accountability due to the lack of active involvement and input in the process of all stakeholders. This lack of stakeholder involvement and input creates audit cultures in which Rasco (2020) claimed that standardization as a device in education empowered neoliberal governments to exert complete control over institutions, technologies, curricula, and practices.

Using Luhmann's general social systems theory founded upon key foundations related to subsystems, such as economic and educational, in society (Luhmann, 1995), Thoutenhoofd’s (2017) case study suggested that teaching and learning have transformed into a governmentdriven system of rote practices that rely on standards-based data collection to measure

effectiveness. Moreover, the neoliberal ideal undergirds the educational process in which knowledge is a commodity that can be marketed and privatized, instilling the belief that "one is compulsively and competitively bound to [learning] for life" (Thoutenhoofd, 2017, p. 440). In other words, the owner of knowledge can manipulate those who are powerless, thus becoming subjects perpetually bound to those in control of knowledge.

Various perspectives from a review of the literature covering existing English language research in accountability reform and professional learning communities provided a contextual framework for the study, including the impact of audit culture, teachers' cultural dispositions, and the phenomena affecting PLCs (Lee & Lee, 2018; Smith & Benavot, 2019; Wilcox & Lawson, 2017)

This qualitative study examined high school teachers in Texas who were required to engage in weekly professional learning community activities such as collaboration, lesson planning, reflecting, and focusing on teaching practice and student learning. According to Prenger, Poortman, & Handelzalts (2018), the fast-paced nature of the education industry and the need for teachers to professionally sustain the demands of change required an examination of the internal viewpoints of high school teachers based on required PLC practices. The research findings were critical in determining teachers' PLC experiences in an evolving environment.

Methods and Procedures

To adequately determine high school teachers' experiences of how planning and instruction were impacted by required professional learning community practices driven by audit culture, the researcher implemented a qualitative study. This study used a prequestionnaire, semistructured interviews, and focus group. Although the researcher needed at least eight participants (n = 8) due to saturation in qualitative studies in which sample sizes of six to 12 participants for

interviews of homogenous groups were sufficient (Boddy, 2016), based on the population and sampling methods, the researcher wanted to recruit a minimum of 20 eligible participants. Recruiting more eligible participants than needed for the study intended to aid in ensuring the sample size of eight participants was reached should teachers voluntarily withdraw from the study. The population of (n = 9951) educators from an educational organization’s messaging application and social media site was considered. Due to the large population size, the researcher determined specific eligibility requirements to indicate the target population. This target population included high school teachers in Texas who were required to engage in professional learning community actions with two or more teachers at least one or more times per week. The teachers in this study engaged in professional learning community practices, including collaboration, lesson planning, reflecting on teaching practice, and focusing on student learning. The sampling strategy involved convenience, snowballing, and purposeful sampling. The anticipated sample size due to the shared phenomena of participants captures "the conditions" for generalizability (Osbeck &Antczak, 2021) as the participants in the study included teachers who engaged in PLC actions of at least two or more high school teachers at least one or more times per week.

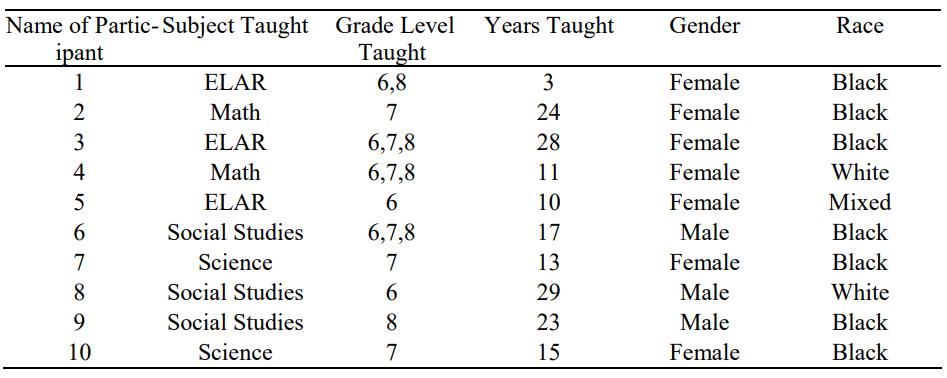

Atotal of nine teachers (n = 9) were recruited for the study, in which all nine participants engaged in a prequestionnaire (Appendix A) This tool also included a few demographic and preliminary questions related to the study and benefited data collection and the communication of results. Five of the respondents were female and four were male. Four respondents taught 10th grade, one respondent taught 9th grade, and the other four taught multiple grade levels. The subject areas taught included four English II teachers, three World History teachers, two of those teachers also teaching Personal Finance and Economics, and two Biology teachers one teaching

Environmental Systems. One respondent taught from 0-4 years, six of the respondents taught from 9-12 years, and two taught from 17-20 years. The number of school settings in which respondents taught was 1-3 for eight teachers and 4-6 for one teacher.Also, the prequestionnaire featured two questions, for qualified participants, to answer from the interview protocol aligning with the research question. These questions enabled the respondents to share their views relating to planning and instruction, were included in the data analysis and triangulated with the other data sources.

Once eligibility was verified, the first four teachers to respond, followed by a commitment of the signed consent form, participated in semi-structured interviews (Appendix B) and the next four teachers participated in a focus group (Appendix C).

Given that qualitative studies include nonnumerical data (Leedy & Ormrod, 2022), measurement considerations in this study focused on participants' experiences and perspectives in which the researcher engaged in a "naturalistic inquiry [approach] because the research involve[d] real-world issues and settings" (Roberts & Hyatt, 2019, p. 143). Qualitative data collected from the prequestionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and focus group were analyzed for research question one. This analysis determined emerging themes that captured and explained high school teachers' perspectives on how required PLC practices and protocols influenced planning and instruction.

Five categories or patterns emerged from the data sources including a culture of audit, planning and instruction, PLC strengths, PLC challenges, and student foci (Table 5.6).

Table 5.6

Category Prequestionnaire

Culture of audit

Planning and instruction

PLC strengths

• resources

Semi-structured Interviews

• expectations

• protocol

• accountability

• standardization

Focus Group

• audit culture (i.e., required, check the box, follow the book, what they ask us to do, robotic, compliance, insufficient solution)

• standardization

• process

• strategy

• no influence

• self-efficacy

• different teaching style

• routine

• PLC effectiveness (i.e., productivity, collaboration, dedicated PLC time)

• support

• collective efficacy

• cohesion

PLC challenges

Student foci

• lack of collaboration

• student buy-in

• student ownership challenges

• student ownership

• lack of cohesion

• PLC theory vs. PLC reality

• lack of time

• student learning levels

• student work

• student ownership

Based on participants' experiences and the literature reviewed, the researcher concluded that teachers’perceptions of PLC experiences related to the patterns of all five categories stated above varied. For example, although participants from both the focus group and semi-structured interview group referenced patterns related to culture of audit, their perceptions of the phenomena were different. These differences were based on perspectives of systems of standardization including compliant-driven PLC requirements and systems of standardization associated with PLC expectations, protocol, and accountability, respectively. For instance, participant 8 (January 2023) answered, “If it's just, you know, checking boxes. I, I ain't really interested in that. I won't even show up…. I've got better things to do with my time. [laughing]....”

Participant 5 (January 2023) stated:

So, I don't know the PLC, I feel like sometimes it's just like this is the new thing. Somebody wrote a book about it and the principals had to read the book in their training, so they're gonna make us do it too…. I can't do that whole robotic, this is what everybody cookie cutter kind of thing, because the kids are not cookie cutter.

Participant 7 (January 2023) conveyed, “I think the, the PLCs in my experience, it, it's more about compliance, the 504 requirements. It's not, it, it, it's, it's more of a CYAthan care about the student.” When relaying his final thoughts about his PLC experiences he mentioned that teachers are expected to understand how to create rigorous lesson plans, analyze data, manage a multitude of classroom personalities without adequate training

Also, study participants’perspectives of planning and instruction experiences differed in that focus group participants believed that the PLC had no influence on their planning or instruction and instead credited self-efficacy and different teaching styles. In contrast, the semi-

structured interview participants attributed their PLC experiences of planning and instruction based on the PLC process and the strategy. Prequestionnaire respondents credited their PLC experiences to the sharing of resources. The semi-structured interview participants were the only group to mention dominant patterns associated with PLC strengths. The researcher concluded that their perspectives of what makes a solid PLC involved routine, elements of PLC effectiveness, (Table 5.6), support, collective efficacy, and cohesion. In contrast, participants’ experiences of PLC challenges for the focus group consisted of perspectives of lack of cohesion, PLC theory versus PLC reality, and lack of time.

The perspectives of the semi-structured interview participants in the same category were the lack of collaboration.Although the focus group and semi-structured interview group shared PLC experiences of student ownership in the student foci category, the participants’perspectives differed by student learning levels and student work followed by student buy-in and student ownership challenges, respectively.

In an era of increasing accountability in education, if educators are expected to meet the rising demands of accountability through student achievement, administrators and policy makers need to provide sustainable support regarding the existing systems that are available to promote transformational change. The teachers in this study offered their authentic experiences of how required PLC practices and protocols influenced planning and instruction. These experiences were intended to close a gap in the literature that revealed the need for further exploration of teachers' perceptions of following required practices and protocols that contribute to audit culture. Guided by the research question and the literature review, the researcher concluded that participants’PLC experiences varied based on patterns that were or were not evident in the PLC.

For instance, any patterns in the study that identified conditions in the PLC such as lack of cohesion, lack of time, no influence, and standardization, led to the participants’perceptions of audit culture. Conversely, participants’PLC experiences with patterns such as expectations, protocol, process, strategy, support, collective efficacy, and cohesion were similar to studies from the literature review which highlighted contextual factors in the PLC, thus, contributing to transformational change. Based on the findings, the researcher's goal was to inform and provide guidance to educational leaders and policymakers what teachers view as limitations to transformative change in an environment of increasing accountability and what teachers perceived as essential factors based on their experiences with required PLC practices.

The following recommendations are associated with both administrators and policy makers appointed to support teachers in the implementation of the work for required PLCs.

1. Administrators and teachers need sustainable training to understand how to properly engage in collaborative PLC practices. Once sustainable training is obtained, administrators need to support teachers in the PLC process around a shared problem of practice that incorporates clear PLC expectations, protocols, and accountability for successful engagement in the PLC process for transformational change.

2. Administrators need to be intentional when developing a school’s master schedule, about allocating at least two periods per week of common planning time for teachers for collaborative PLC engagement.

3. Administrators need to empower teachers to maintain a level of autonomy through teacher voice and decision-making when engaging in PLC planning and instructional experiences so they can benefit from gaining trust in the process and improve teacher practice through problem-solving, risk-taking, and reflection.

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative market research: An International Journal, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/qmr-06-2016-0053

Bradley, E. (2023). Audit culture: High school teachers’ perspectives on following required practices and protocols in professional learning communities [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Leo University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Commissioner’s Rules Concerning Educator Standards, 19 Texas EducationAgency §149.1001 (2014).

https://texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.TacPage?sl=R&app=9&p_dir=&p_rloc= &p_tloc=&p_ploc=&pg=1&p_tac=&ti=19&pt=2&ch=149&rl=1001

Dogan, S., Pringle, R., & Mesa, J. (2016). The impacts of professional learning communities on science teachers' knowledge, practice and student learning:Areview. Professional Development in Education, 42, 569–588.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19415257.2015.1065899?journalCode=rjie 20

DuFour, R. P. (1999). Help wanted: Principals who can lead professional learning communities. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 83(604), 12-17.

https://saintleo.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarlyjournals/help-wanted-principals-who-can-lead-professional/docview/216047344/se-2

Every Student Succeeds Act, 20 U.S.C. § 6301 (2015). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114thcongress/senate-bill/1177

Gonzalez, A., Peters, M. L., Orange, A., & Grigsby, B. (2016). The influence of high-stakes testing on teacher self-efficacy and job-related stress. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(4), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2016.1214237

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Lee, D. H., & Lee, W. O. (2018). Transformational change in instruction with professional learning communities? The influence of teacher cultural disposition in high power distance contexts. Journal of Educational Change, 19(4), 463–488.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9328-1

Leedy, P. D. & Ormrod, J. E. (2019). Practical research: Planning and design. Pearson. Luhmann, N. (1995). Social Systems. Stanford University Press. No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, P.L. 107-110, 20 U.S.C. § 6319 (2002).

https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-bill/1

Osbeck, L. M., &Antczak, S. L. (2021). Generalizability and qualitative research: Anew look at an ongoing controversy. Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 62–68.

https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000194

Philpott, C., & Oates, C. (2016). Professional learning communities as drivers of educational change: The case of learning rounds. Journal of Educational Change, 18(2), 209–234.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9278-4

Prenger, R., Poortman, C. L., & Handelzalts, A. (2018). The effects of networked professional learning communities. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(5), 441–452.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117753574

Rasco, A. (2020). Standardization in education, a device of Neoliberalism. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS), 18(2), 227–255.

Roberts, C., & Hyatt, L. (2019). The dissertation journey: A practical and comprehensive guide to planning, writing, and defending your dissertation. Corwin, a SAGE Company. Skourdoumbis, A. (2018). Theorising teacher performance dispositions in an age of audit. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3492

Smith, W. C., & Benavot, A. (2019). Improving accountability in education: The importance of structured democratic voice. Asia Pacific Education Review, 20(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09599-9

Thoutenhoofd, E. D. (2017). The datafication of learning: Data Technologies as reflection issue in the system of Education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 37(5), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-017-9584-1

Wilcox, K. C., & Lawson, H.A. (2017). Teachers' agency, efficacy, engagement, and emotional resilience during policy innovation implementation. Journal of Educational Change, 19(2), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9313-0

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A: Prequestionnaire

1. Are you a high school teacher in Texas? Yes or No

2. Do you engage in professional learning community meetings of at least 2 or more teachers weekly? Yes or No

3. Do you engage in professional learning community meeting protocols (i.e., norms, lesson planning, common assessments, etc.) Yes or No

If you answered no to any of the questions above, you are not eligible for participation in this study. Thank you for your interest.

If you answered yes to all three questions, you are eligible for participation in this study. Please continue with answering the few remaining questions in the prequestionnaire and return the attached consent form in your email to erin.bradley@email.saintelo.edu for participation in the study.

What grade level(s) do you teach? ___ What course(s) do you teach? _________

Gender ______

Number of school settings? ____

Years of teaching experience? _______

What is your highest attainment of education?______

1. How is your experience collaborating/working together with peers in the PLC?

2. How has PLC planning influenced how you teach your lessons in the classroom?

Thank you for your time and willingness to complete this prequestionnaire and to participate in this study.

APPENDIX B: Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

Opening Question:

1. Tell me about yourself.

• What grade level and course(s) do you teach?

• How long have you taught? Which grade levels and/or subjects?

• Overall, how would you characterize your experiences with teaching in education?

Research question one.

What are the experiences of high school teachers in how required PLC practices and protocols influence planning and instruction?

Planning

2. What are your experiences with the PLC planning process?

• How do you plan for units and/or lessons in the PLC?

• How do you design formative and summative assessments in the PLC?

• How do you analyze student work in the PLC?

• How is your experience collaborating/working together with peers in the PLC?

Instruction

3. How have your experiences with the PLC planning process influenced instruction in your classroom?

• How has PLC planning influenced how you teach your lessons in the classroom?

• How has PLC planning influenced how you communicate with students about what they need to learn and how they master the learning standards?

• How has PLC planning influenced your implementation of student-centered learning experiences?

• How has PLC planning influenced your design of tiered instruction for students?

4. What other information would you like to provide about your experiences in the PLC process?

APPENDIX C: Focus Group Protocol

Opening Question:

1. Tell me about yourself.

• What grade level and course(s) do you teach?

• How long have you taught? Which grade levels and/or subjects?

• Overall, how would you characterize your experiences with teaching in education?

Research question one.

What are the experiences of high school teachers in how required PLC practices and protocols influence planning and instruction?

Planning

2. What are your experiences with the PLC planning process?

• How do you plan for units and/or lessons in the PLC?

o Tell me more…

o Can you give me an example?

o Is this similar or different in your experience? Please explain.

• How do you design formative and summative assessments in the PLC?

o Tell me more…

o Can you give me an example?

o Is this similar or different in your experience? Please explain.

• How do you analyze student work in the PLC?

o Tell me more…

o Can you give me an example?

o Is this similar or different in your experience? Please explain.

• How is your experience collaborating/working together with peers in the PLC?

o Tell me more…

o Can you give me an example?

o Is this similar or different in your experience? Please explain.

Instruction

3. How have your experiences with the PLC planning process influenced instruction in your classroom?

• How has PLC planning influenced how you teach your lessons in the classroom?

• How has PLC planning influenced how you communicate with students about what they need to learn and how they master the learning standards?

• How has PLC planning influenced your implementation of student-centered learning experiences?

• How has PLC planning influenced your design of tiered instruction for students?

• What other information would you like to provide about your experiences in the PLC process?

Black girls deserve to be girls

Black girls deserve to be girls: A comparison of school-based social and emotional practices on the impact of discipline rates of African American middle school girls

Kristi Morale

TABSE Research Journal

Volume 1, Number 1, 2024

Introduction

Received January 15 2024

Revised April 1 2024

Accepted May 27 2024

On May 22, 1962, Malcolm X gave a speech in Los Angeles to and about Black women where he stated, “The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman” (Alexander Street, 2014). Over 60 years later, this statement still rings true across the United States, including in U.S. schools where Black girls are disrespected, unprotected, and neglected day after day.

Black women have traditionally led the way in advancing educational equity in the Black community. However, Black girls still face substantial obstacles to achieving in the classroom today. While there is abundant research on the discipline disparities facing Black boys in the public school system, Black girls are missing from these conversations. The lack of academic literature on the plight of Black girls in schools leads to the assumption that the futures of Black girls are not at risk (Crenshaw et al., 2015). Each day, Black girls face a variety of factors that heighten their risk of underachievement and detachment from school (Crenshaw et al., 2015). These factors contribute to Black girls being criminalized by their schools, the very places that

© Written by Kristi Morale. Published in TABSE Research Journal. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and author(s).

should help them thrive (Morris, 2016). This study sought to identify the effect of social and emotional learning on the impact of discipline rates of African-American middle school girls. A sequential exploratory mixed methods design was used in which the researcher analyzed the effect of social and emotional learning practices on Black girls' discipline experiences. This study contributes to the research on the social and emotional well-being of Black girls by giving them a voice to share how they are doing in our schools and how they believe we can better support their needs. To assess the impact of social and emotional practices on the discipline rates of middle school girls, the following questions were sought:

RQ1: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on in-school suspension rates among Black girls?

RQ2: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on out-of-school suspension rates among Black girls?

RQ3: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on Disciplinary Alternative Education Programs (DAEP) rates among Black girls?

RQ4: In what ways do social and emotional learning practices affect the emotional wellbeing of middle school Black girls?

Review of the Literature

The Criminalization of Black girls in Schools

According to a report by the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, Black girls are 7xs more likely to receive one or more out-of-school suspensions, 4xs more likely to be arrested, and 4xs more likely to receive one or more in-school suspensions in comparison to White female

students (National Black Women’s Justice Institute & Inniss-Thompson, 2018). Even though there have been established racial inequities in school discipline since the 1970s, disparate punishment practices' effects on Black girls have only recently been studied (Smith-Evans et al., 2014). According to data from 2006–2007, Black girls in urban middle schools experienced the most significant rate of suspension growth of any demographic (Losen et al., 2010).

Compared to 12 percent of Black girls, only 2 percent of White Girls experienced exclusionary suspensions (Crenshaw et al., 2015). The relative risk of suspension is higher for Black girls compared to White Girls than for Black boys compared to White boys, indicating that race may play a more significant role for girls than boys (Crenshaw et al., 2015). While Black boys and Black girls both suffer a racialized risk of punishment at school, Black girls statistically have a higher risk of suspension and expulsion than other pupils of the same gender (Crenshaw et al., 2015). More data on the disciplinary experiences of Black girls is required to properly comprehend how unfair discipline practices affect the achievement and social adjustment results of Black children overall (Blake et al., 2011).

In the book, Sing a Rhythm, Dance a Blues, Morris (2019) shares a model school that supports the social and emotional well-being of Black girls after researching the criminalization of Black girls, Stephanie Patton, a middle school principal in Columbus, Ohio, decided that the campus would no longer punish students for bad attitudes. In place of exclusionary discipline practices, a plan was created that included social and emotional learning practices. Black girls would participate in mentoring, positive behavioral interventions and supports, and restorative conferencing. Girls would begin the day with an advisory program that promoted girls' self-worth, communication skills, and goal-setting. The campus began to use

suspensions only as a last resort. Along with the new discipline plan, the campus also created a visually stimulating Social Emotional Learning (SEL) environment with positive quotes around the building and calming spaces for girls to regroup or reflect before or after a conflict. With these initiatives in place, campus attendance increased, and suspensions decreased. Zero students were expelled, and student ownership of conflict improved.

Conceptual Framework

Social Emotional Learning

Social Emotional Learning (SEL) is defined as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions” (CASEL, 2022, para. 1). Research shows that SEL education has positively affected various outcomes, including academic performance, good relationships, mental wellness, and more (CASEL, 2022). Specifically, SEL instruction can lead to less emotional distress, fewer disciplinary incidents, increased school attendance, and improved test scores and grades (Clark, n.d.). Schools implementing SEL practices have a culture where students and teachers respect one another (Positive Action Staff, 2022).

Black Girlhood Theory

Ruth Nicole Brown (2009) defines Black Girlhood as “the representations, memories, and lived experiences of being and becoming in a body marked as youthful Black and female” (Brown, 2009, x). The study of Black Girlhood focuses on the social and cultural experiences of Black girls Black Girlhood Studies, emphasize how Black girls bring valuable insights into the deficit-based narratives (Wright, 2016). “Black Girlhood makes possible the affirmation of Black girls’ lives and, if necessary, their liberation” (Brown, 2013, p. 1). It is

essential to investigate how Black girls still enjoy and express childhood delight and creativity despite the oppressive institutions that they face (Epstein et al., 2017). Black girlhood can be a powerful weapon for Black girls to establish safe places for themselves and each other despite how society views them (Brown, 2009, p. 2).

Research Design

Quantitative Population

The first campus in the study is Sampson Middle School. Sampson Middle School is a public school in a large suburban setting. Sampson Middle School does not employ any specific social and emotional learning practices. The two campus counselors are available upon request from students and teachers to support the students' mental health. The second campus in the study is Malcolm Middle School. Malcolm Middle School is a magnet school located in a large city setting. The campus employs two full-time counselors and one full-time social worker. This campus also has the support of a district Teacher Behavior Specialist who supports the campus as the Social Emotional Learning Coordinator. Malcolm Middle School has a customized social and emotional learning program for scholars on campus. The campus counselors are available upon request from students and teachers to support the students' mental health.

Qualitative Population

The qualitative sample comprised nine self-identified Black girls who attended the two different middle schools. Four girls were interviewed from Malcolm Middle School, a campus that utilizes social and emotional learning practices, and five from Sampson Middle School, a campus that does not. The girls' grade range was sixth to eighth, with two girls in 6th grade, four in 7th grade, and three in 8th grade. Convenience sampling was used to recruit interview participants.

Quantitative Instrument

For the quantitative part of the research study, pre-existing discipline data was used from the two participating campuses. The data set included the in-school suspension rates, out-of-school suspension rates, and DAEP rates for the Black girls attending the campuses.

Qualitative Instrument

An interview was conducted to assess the participants' social and emotional well-being. The thirteen-question questionnaire, which included questions in each of the five CASEL (Collaborative For Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning) Competencies, included ten open-ended questions, one yes or no question, and two Likert scale questions, with answer choices being always, very frequently, occasionally, rarely, very rarely, and never.

Quantitative Data Collection

The two participating campuses provided the datasets used in the quantitative analysis. Each report included the student's discipline occurrence, grade level, race, and sex. Raw data included girls of all races but was split to allow for the interrogation of only Black girls' discipline occurrences from the 2021-2022 school year.

Qualitative Data Collection

Girls were interviewed individually in a private office, and the interviews lasted approximately 10 minutes. The responses were audio recorded. In addition, the researcher took notes during the data collection to assist in the analysis process. Only the researcher had access to recorded materials and digital notes.

Quantitative Data Analysis

A t-test was used to compare the data from each campus using the campus discipline report results. The t-test compared the mean of the two groups to determine whether the campus

that utilizes social and emotional learning practices has a higher, lower, or the same discipline rate as the campus that does not implement social and emotional learning practices.

The interviews were audio recorded for transcribing purposes. The audio recordings were transcribed using the Otter Transcription Tool and then transcribed again by the researcher. During the transcription process, all participant names were replaced with pseudonyms. Following transcription, the researcher analyzed the interviews and identified common themes. Once the common themes were identified, the researcher summarized the results to determine the effects of social and emotional learning practices on the emotional well-being of the girls.

Quantitative Findings

The quantitative analysis addressed all three research questions presented.

RQ1: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on in-school suspension rates among Black girls? An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean scores of the two groups of participants. The results were t = 3.771 p = .001. This data shows a more significant occurrence of in-school suspension assignments at Sampson Middle School, a campus that does not engage in social and emotional learning practices. Zero Black girls at Malcolm Middle School were assigned in-school suspension as a discipline sanction during this school year. This data suggests that the use of social and emotional learning practices has a positive effect on the in-school suspension rates of Black Middle School Girls

RQ2: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on out-of-school suspension rates among Black girls? An independent samples t-test was conducted

to compare the mean scores of the two groups of participants. The results were t = -2.238, p = .030. This data shows that while both campuses assigned out-of-school suspension to Black girls as a disciplinary practice, administrators at Sampson Middle School were almost three times more likely to give this punishment than administrators at Malcom Middle School. This data suggests that the use of social and emotional learning practices has a positive effect on the outof-school suspension rates of Black Middle School Girls.

RQ3: Are there any differences between middle schools that utilize social and emotional learning practices and middle schools that do not use social and emotional learning practices on DAEP rates among Black girls? An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean scores of the two groups of participants. The results were t = -.899, p = .373. The outcome was not statistically significant, indicating that social and emotional learning practices did not affect the DAEP rates of middle school Black girls.

The qualitative portion of this study aimed to analyze the voices of the Black girls attending Malcolm Middle School and Sampson Middle School. The data yielded significant findings on the emotional well-being of Black Middle School Girls. Ultimately, the girls shared their experiences with the social and emotional learning practices facilitated on their campus.

There was a noticeable difference in responses between the girls at the two campuses regarding relationship building. The participants from Malcolm Middle School all believed that their teachers had made a concerted effort to build a relationship with them, while all but one of the participants from Sampson Middle School shared a negative outlook on one or more of their teachers in this area.

In the area of responsible decision-making, the participants, almost across the board, understood that they should try not to engage in a conflict or to seek help from an adult should a conflict or problem arise. All participants understood the decision-making process and spoke to thinking through a decision before making a choice and understanding how their choices could affect themselves and others. In response to the question on needing a break, all of the girls from Malcolm Middle School understood that they could go to their counselor or social worker, with one describing a calming corner where she sometimes goes and works inside the counselor's office. While the participants from Sampson Middle School all shared that there is a space where they could take a break if needed, many of the girls' first response was the hallway or the bathroom.

Regarding having a trusted adult on campus, all of the girls from both campuses, except one, shared that they trust at least one adult on campus. For many participants, this person was either the counselor, social worker, or administrator on the campus. When discussing preparing for the future, many girls at both campuses noted that they have participated in classes or projects to help them plan for the future. However, some girls could only share the athletic activities they participated in as preparation for their futures.

In the area of emotional safety, most of the girls from both campuses stated that they only feel safe occasionally, with three participants sharing that they rarely feel emotionally safe. When engaging with individuals different from them, most girls expressed no different feelings, including sometimes, you cannot even notice other people’s differences. A few of the girls did convey a sense of awkwardness when first around individuals with differences. When presented with an opportunity to share anything else related to their social and emotional well-being and their school, some of the participants from Sampson Middle School

believed that their campus should make staffing changes due to the teachers not caring about their needs and or stereotyping them based upon their race or past behavior. One participant from Malcolm Middle School expressed that they need more counselors to support the campus as the social worker spends most of their time working on other tasks for the campus.

Interpretation

Ultimately, the girls feel that their social and emotional needs are being fostered on both campuses, while there are noticeable differences in structure from one campus to the other. At Malcolm Middle School, it was evident from speaking with the girls that the personnel on the campus are making a concerted effort to support their social and emotional needs. While many of the staff at Sampson are also making a valiant effort to support the girls, it was evident that these efforts are being made independently and not due to specific training or resources from the campus or the district. This shows up in the suspension data, where the girls on this campus are more likely to be subjected to in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and DAEP referrals than those at Malcolm Middle School. Although it is incredible that these educators are making an effort to build relationships with the girls they serve while also being a trusted adult they can turn to in a time of need; there should be an effort made to ensure that all staff have the training and resources to best support the social and emotional well-being of not just the Black girls on the campus but the entire diverse student body.

1. Social and emotional programming should be utilized to foster inclusive learning environments and teach scholars the tools needed to become well-rounded adults.

2. Leaders should investigate alternative forms of school discipline that can solve student discipline issues without excluding students from the campus culture.

3. Campus leaders should frequently analyze discipline data and policies by student population to understand the trends and create a plan of action.

4. To best support the whole child, teachers must receive training to best support the student demographic they serve.

5. Campuses should be staffed with trained and certified counselors to support students.

6. Policymakers should ensure an equal approach to funding that supports the needs of both men and boys and women and girls.

7. Policymakers should mandate intervention practices before girls can be removed from school for subjective offenses.

The premise of this study was to understand the scope of social and emotional learning practices on the discipline rates of Black Middle School Girls. Black girls in this study were considered more than a subject but as the voice. This research is a step in finding ways that stakeholders can work together to solve issues Black girls are plagued with daily in schools. In summary, more is required from educators, administrators, parents, and lawmakers to guarantee that Black girls can access equitable schooling. Black girls deserve the necessary support to heal and learn because of the conditions in their schools, not despite them.

1. How have your teachers and other school personnel attempted to build a relationship with you?

2. What strategies have you been taught for building relationships with others?

3. What conflict resolution techniques have you been taught this year?

4. What problem-solving strategies have you been encouraged to use this year?

5. Where can you go on campus if you need to take a break?

6. If you need someone to talk to, is there someone on campus that you trust? Yes/No

7. What activities have you done this year to plan for the future?

8. How often do you feel emotionally safe at school? Always, Very Frequently, Occasionally, Rarely, Very Rarely, Never

9. How often are you able to identify your emotions? Always, Very Frequently, Occasionally, Rarely, Very Rarely, Never

10. What steps do you take when you have to make a decision?

11. How do you feel when you are around people who are different from you?

12. When conflict arises between you and another person, what steps do you take to diffuse the situation?

13. Is there anything else you would like to share with me about your social-emotional needs or your school?

Relationship Skills

Relationship Skills

Responsible-Decision Making

Responsible-Decision Making

Self-Awareness

Self-Management

Self-Management

Social-Awareness

Self-Awareness

Responsible Decision Making

Social Awareness

Responsible-Decision Making

All Competencies

References

Alexander Street. (2014). Malcolm X: “Who taught you to hate?” speech excerpt. Alexander Street.

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/preview/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7 C2785586

Blake, J. J., Butler, B. R., Lewis, C. W., & Darensbourg, A. (2011). Unmasking the inequitable discipline experiences of urban Black girls: Implications for urban educational stakeholders. The Urban Review, 43(1), 90–106.

Brown, R. N. (2009). Black girlhood celebration: Toward a hip-hop feminist pedagogy. Peter Lang.

Brown, R. N. (2013). Hear our truths: The creative potential of Black girlhood. University of Illinois Press.

Clark, A. (n.d.). Social emotional learning: What to know. Understood.org.

https://www.understood.org/en/articles/social-emotional-learning-what-you-need-toknow

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2022). What does the research say? https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-does-the-research-say/

Crenshaw, K. W., Ocen, P., & Nanda, J. (2015). Black girls matter: Pushed out, overpoliced and underprotected. African American Policy Forum.

https://www.aapf.org/_files/ugd/62e126_4011b574b92145e383234513a24ad15a.pdf

Epstein, R., Blake, J., & González, T. (2017, June 27). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls' childhood. The Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality.

https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

Losen, D. J., Skiba, R. J., & Gagnon, J. (2010, September 13). Suspended education suspended education. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k12-education/school-discipline/suspended-education-urban-middle-schools-incrisis/Suspended-Education_FINAL-2.pdf

Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools. New Press. Morris, M. W. (2019). Sing a rhythm, dance a blues: Education for the liberation of Black and brown girls. New Press.

National Black Women's Justice Institute & Inniss-Thompson, M. N. (2018). Summary of discipline data for girls in U.S. public schools: An analysis from the 2015 - 2016 U.S. Department of Education office for civil rights data collection. National Black Women's Justice Institute. https://www.nbwji.org/_files/ugd/0c71ee_9506b355e3734ba791248c0f681f6d03.pdf

Positive Action Staff. (2022, January 19). Social emotional learning history: An intriguing guide. Positive Action. https://www.positiveaction.net/blog/sel-history

Ricks, S. A. (2014). Falling through the cracks: Black girls and education. Interdisciplinary Journal of Teaching and Learning, 4(1), 10–21.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1063223.pdf

Skiba, R. J., Peterson, R. L., & Williams, T. (1997, August). Office Referrals and Suspension: Disciplinary Intervention in Middle Schools. Education And Treatment of Children, 20(3).

Smith-Evans, L., George, J., Goss Graves, F., Kaufmann, L. S., & Frohlich, L. (2014). Unlocking opportunity for African American Girls: A call to action for educational equity. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. https://www.naacpldf.org/wpcontent/uploads/Unlocking-Opportunity-for-African-American_Girls_0_Education.pdf

Wright, N. S. (2016). Black girlhood in the nineteenth century. University of Illinois Press.

Michael Allen

TABSE Research Journal

Volume 1, Number 1, 2024

Introduction

Received January 15 2024

Revised March 31 2024

Accepted May 27 2024

Many people believe that schools are designed to serve as high quality institutions of academic and social development for students. As education in the United States becomes more complex for current students, it has become very difficult to identify how to support parents, educators and students. Over the last 5 years in particular, there have been a number of concerning data points and trends including inconsistent academic performance on standardized tests, a rapid decline in student attendance and a notable increase in depression, suicide and physical violence in schools in America that seems connected to the mental health crisis.

As educators all over the country struggle with the cumulative weight and impact of the learning loss for students, perhaps no measure has been more pronounced since the pandemic than standardized test scores. In fact, NPR published an article indicating that according to data released by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, reading and math scores in the United States dropped to the lowest levels in decades over the last few years. Specifically with respect to the 2022-23 academic year, the average scores in math declined by 9 points and the scores in reading declined by 4 points respectively when compared to the 2019-2020 academic year. The math results were even more staggering when you factor in race and gender. For example, scores on average decreased by 11 points for female students and 7 points for male

© Written by Michael Allen. Published in TABSE Research Journal. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and author(s).

students over this same period of time. Similarly, for black students, math scores dropped by 13 points compared to a 6-point drop for white students. With all things considered, the academic performance gap between black and white students widened from 35 points to 42 points during this period (Carillo, 2023).

The same dismal trend has held true for student attendance as schools all over the United States have seen a rise in chronic absenteeism. In fact, “72 percent of U.S. public schools reported an increase in chronic absenteeism among their students” when compared to a typical year before the pandemic (James, 2022).

Along the same path, the Center for Education Statistics published a study indicating that “80 percent of public schools reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted student socio-emotional development during the 2021–22 school year” (James, 2022). The same study went on to assert that public schools all across the country reported needing “more support for student and/or staff mental health (79 percent), training on supporting students’ socioemotional development (70 percent), hiring of more staff (59 percent), and training on classroom management strategies (50 percent)” (James, 2022).

The final point underscores the current impact that all of the factors highlighted above have had on students as well as the concerning ways that youth have responded. In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a national Youth Risk Survey. The survey revealed that 42 percent of youth reported feelings of persistent sadness or hopelessness. 22 percent of youth from the same survey reported that they considered suicide, 18 percent made a suicide plan, and 10 percent reported that they attempted suicide.

As a result, educational researchers and practitioners have been charged with the tremendous task of identifying some solutions to improve this reality for students in schools.

As alluded to above, more than identifying what accounted for the problem, the research sought out some important concepts and ideas to support leaders with respect to how to respond to this reality.

The research unpacked the need for people's "humanity" to be considered more through tangible, practical and explicit means. Humanity was defined as the ability to connect with all forms of human life.

Current and future administrators must be prepared for the challenges associated with leading schools in a post pandemic society. Labby et al. (2012) conducted a study that focused on examining if there was a link between effective leadership skills, best practices and student achievement. The research specifically analyzed the role that principals assume with respect to improving student achievement. The study concluded that the total direct and indirect effect that leadership can have on improving student achievement is upwards of about one quarter of the total school effect (Allen, 2018). It is clear that the principal’s leadership is a strong contributor to student achievement and school success. This same body of research suggested that if we aren’t intentional with how we improve school leaders' capacity, the cumulative impact will result in good teachers eventually leaving the schools, especially in urban educational environments (Khalifa, Gooden & Davis, 2016). Principals are one of the few roles that can enable them to “shape growth-enhancing climates that support adult learning as they work to manage adaptive challenges” (Dragp-Severson, 2012, p. 1). The information clearly outlines the reality that school leaders' decisions and behaviors can have a profound impact on student learning environments with respect to teaching and learning. However, the research sought out to identify a leadership approach that meets the present complexities in schools. Further, there has been a growing amount of studies that suggest that the leader’s

emotional intelligence can significantly shape leadership choices. Daniel Goleman spent a large amount of time researching the various components of leadership and his research determined that the most skilled 21st century leaders demonstrate a high level of emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence is the ability to manage a person’s own emotions in an effort to be directly sensitive to the needs of others. The essential elements of emotional intelligence include: self-awareness, self-management, motivation, empathy, and social skills. Without emotional intelligence, a person could have elite technical training, superior analytical skills and a countless flow of sharp ideas but will likely struggle with having success in the current landscape of leadership (Allen, 2018). “Emotional intelligence is the path [where when] we start it we are to move towards personal, team, and whole school excellence” (Brearley, 2006, p. 30). Presently, in the field of education the principal’s ability to effectively display social awareness, empathic behavior, strong decision making skills, and exert a positive influence over others is essential. As profound as the studies are as described as above, all were conducted before the pandemic. As a result, the research attempted to zero in on a consistently preferred leadership approach that focused on the foundations of emotional intelligence while also showing the potential to support the unique challenges in schools related to mental health etc.

Since the onset of the pandemic, Rasmus Hougaard and Jacqueline Carter (2021) published an article that highlighted the findings of a study that they conducted with leaders from more than 5,000 companies in over 100 countries. Their research set the stage for what has been coined "humane" leadership. In short, it is a modern version of emotional intelligence infused into leadership that could enhance the current state of K-12 education. Humane leadership is a unique display of combining both wisdom and compassion in the decision making process of leaders. It asserts that success is connected to culture in the workplace and culture is correlated to the decisions that leaders make. In order to radically improve success leaders must consider and prioritize: 1) The golden rule, 2) listen intently, 3) introspection, and

4) stretch people to see their potential. While the study focuses on humane leadership practices in businesses and other corporate organizational structures different from schools, the essential elements of the leadership framework appear to be transferable to the K-12 school setting.

The goal for this informal qualitative study was to combine the findings of Hougaard and Carter's study with the benefits of emotional intelligence in an effort to support the reality that schools are currently experiencing with respect to the mental health crisis. The qualitative research was specifically trying to consider the value of applying humane or compassionate leadership decisions in real time in the field of education to neutralize the effects of the mental health crisis on schools. The research questions for the study were:

1. Are there specific types of responses that can be used by leaders in the public school system to prioritize the humanity of students?

2. Similarly, are there aspects of humane leadership that can support how students respond to the mental health crisis in schools?

The hypothesis was that there are consistently preferred responses and actions that leaders can take in schools to ensure that students feel that their humanity is prioritized and there are aspects of humane leadership in particular that can support students as they tackle the day-to-day challenges connected to the mental health crisis.

Through semi-structured interviews with 111 students, parents, staff, and school and district leaders in the United States, the researcher was able to unearth some implications for leaders that can be used to inform the field of education at the systems level. For each participant, the researcher used a 1-2 minute semi-structured interview to gather perceptions of their needs related to their “humanity” from people connected to schools.

The researcher referred to the process described by Zhang and Wildemuth (2009) to prepare and code the data gathered from the interviews. Each participant’s interview was

recorded and later transcribed. Next, the researcher determined the unit of analysis. It was determined that key words, phrases or ideas would be analyzed in order to allow for the maximum number of participant responses to be compared. Then the researcher developed categories, and a coding scheme, and tested the scheme to ensure that it authentically represented each participant’s responses. The text from the transcriptions was coded and assessed for consistency. Eventually, the researcher reviewed the themes and codes that emerged and made sense of them in order to draw conclusions.

It is important to note that the research revealed that there are some consistently preferred responses and actions that leaders can take in schools to ensure that students feel that their humanity is prioritized. Similarly, there are some aspects of humane leadership that can support students as they tackle the challenges connected to the mental health crisis.

Specifically with respect to the qualitative study that was conducted, there were five distinctive codes that emerged from the research split between two key categories. The first category was described as internal areas and the second was described as external areas. Two important themes emerged from the participants about what types of feelings or support that humans are seeking at our core in an “internal” way. They were categorized as emotional safety and emotional literacy.

1. Emotional safety: is an unconscious desire and need to be authentic to one’s self.

Permission came up often as if it were something that each person could claim internally based on the messages in our environment.

2. Emotional literacy: is our ability to name the various emotions that we experience in our bodies during a given point in time. Again, this area is internal for each person but one’s ability to understand and embrace what is felt could be influenced by the environment or surrounding factors.

Three other important themes emerged from the participants about what types of responses humans are seeking at our core in an “external” way. They were categorized as pure, proximate and humane

1. Pure responses: from a clear mental space. The examples from the research that participants identified included how they perceived that people were often unaware that they were bringing things from outside of the interaction into the space (i.e. strained relationships, financial problems, family sickness, difficult news from the doctor etc.). For example, one participant from the study stated, “I could tell the difference in how I was treated based on the personal things that were going on in my assistant principal’s life. It was the worst while she was going through the process of her divorce.” Moreover, that lack of awareness impacted the inconsistency of how others perceived school leaders' responses.

2. Proximate responses: from the "seat" of the other person impacted by our decisions. The examples from the research that participants identified included taking into account and accepting the lived truth of folks who have a different point of view than you. This could be related to gender identities, culture, sexual orientation etc. The point here is implementing the concept of prioritizing this skill or awareness when making a decision that impacts this particular person or group. For example, a second participant from the study stated, “I just feel like the things that are important to me about me are often in question with the staff. They never give me permission to be all parts of me. I wish they made the time to understand me better.”

3. Humane response: from the purest, warm and connected space of the heart. The

examples from the research that participants identified included holding yourself accountable for treating the person impacted by your decision as you would a beloved friend or family member (whose actions are in part a reflection of you). For example, another participant from the study stated, “I don’t think it’s too much to ask them to treat my baby like they would their own. I don’t expect for them to get everything right but my son, even when he is wrong, shouldn’t be made to feel like a criminal.”

The study provides a practical bridge to not only analyzing the problems attached to the current mental health crisis, but it begins to make connections to holistic best practices that can be used by educators to actively “reclaim” humanity. In a world where school leaders are being stretched thin, it is essential to provide explicit and detailed information on where their time can be best spent in order to offset the impact of the mental health crisis on students in schools.

EQ Domain

Self-Awareness

Self-Management

Social Awareness

Relationship Management

Table 1

Humane Leadership Tenant Humanity Qualitative Study Area (PPH)

Listen Intently Pure, Proximate

Remember the Golden Rule Pure, Proximate, Humane

Introspection / Compassion Pure, Proximate, Humane

Stretch People to See Potential Pure, Proximate

As outlined in Table 1, the research asserts that it is imperative that leaders focus on the key components of emotional intelligence, specifically the tenants outlined in humane leadership as well as the pure, proximate and humane responses as described in the qualitative study. Similarly, Table 1 aids in illustrating the overlap in emotional intelligence with humane leadership as well as the qualitative study. It is important to note that the study can support

school leaders and other people associated with schools in developing a deep understanding of how the current mental health crisis is impacting the education system in the United States and in their own schools; critique emotional literacy and how it is explicitly connected to teaching and learning; assess emotional safety and how it is explicitly connected to teaching and learning in their school; and evaluate best practices that humane or compassionate leaders leverage in order to create culturally inclusive learning spaces that center the humanity of all people as well as determine where these practices are/are not in their school. This research explicitly provides tools and knowledge necessary to address mental health challenges in a holistic manner. For example, one area that was consistently implied by most participants is a need to feel loved. In order to do so, it is imperative that leaders consider a universal definition for adults and students in schools. One example is outlined in Bell Hooks’ piece Love as a Practice for Freedom. She explains that Scott Peck defines love as "the will to extend one's self for the purpose of nurturing one's own or another's emotional or spiritual growth" (Hooks, 1994). Similarly, Forward Promise (2022) published an article that explicitly outlined six ways that schools and communities can aid in the process of reclaiming the humanity of students of color. However, the research of this study asserts that these concepts apply to any person or group of people that have been marginalized in any way. The six approaches include: 1. rejecting negative narratives, 2. finding joy, 3. connecting to culture, 4. embracing authenticity and belonging, 5. looking after mental health needs, and 6. encouraging rest and self-care.

The study had several limitations: (1) The sample size of the research was small (included 111 participants). (2) The participant responses in this qualitative study highlight needs and desires that have not been met and don't factor in feelings after leaders have responded to the needs or desires. (3) While the mental health crisis is a glaring contributor to

the problem that schools are currently facing, it isn’t the only factor or variable. However, this study doesn’t necessarily account for that. As a result, we cannot use the data from this study to generalize that if “key” leaders from schools adjusted their behaviors to fit the findings or recommendations of the study that their schools will immediately improve in universally documented ways. Nonetheless, we can assert that adopting the findings from the study will not undermine or harm inherited structures and functions of schools. (4) As described above, the study focused almost exclusively on the actions and behaviors that leaders can take to influence the conditions experienced by students in schools. However, while we can assert that there are implications to other roles, the study didn’t analyze the impact of other certified and noncertified staff members beyond formal school leaders.

References

Allen, M. (2018). Emotional intelligence (EQ), Generational Status and the ... eCommons.

https://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3768&context=luc_diss

Brearley, M. (2006). The Emotionally Intelligent School: Where leaders lead learning. Management in Education, 20(4), 30-31.

https://doi.org/10.1177/08920206060200040701

Carrillo, S. (2023, June 21). U.S. reading and math scores drop to lowest level in decades. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/21/1183445544/u-s-reading-and-math-scores-drop-tolowest-level-in-decades

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April). YRBSS results. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/results.htm

Drago-Severson, E. (2012). New Opportunities for Principal Leadership: Shaping School Climates for Enhanced Teacher Development. Teachers College Record, 114(3), 1-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211400305

Forward Promise. (2022, August 2). Six ways families and communities can reclaim the humanity of students of color this school year. Forward Promise.

https://forwardpromise.org/blog/six-ways-families-and-communities-can-reclaim-the-hu manity-of-students-of-color-this-school-year/

Hooks, B. (1994). “Love as the practice of freedom.”

https://uucsj.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bell-hooks-Love-as-the-Practice-of-

Freedom.pdf

Hougaard, R., & Carter, J. (2021, November 23). How to be both an effective leader and a good person. Harvard Business Review.

https://hbr.org/2021/11/becoming-a-more-humane-leader

James, E. (2022, July 6). More than 80 percent of U.S. public schools report pandemic has negatively impacted student behavior and socio-emotional development. Press ReleaseMore than 80 Percent of U.S. Public Schools Report Pandemic Has Negatively Impacted Student Behavior and Socio-Emotional Development - July 6, 2022.

https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/07_06_2022.asp

Khalifa, M. A., Gooden, M. A., & Davis, J. E. (2016). Culturally Responsive School Leadership: A Synthesis of Literature. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1272-1311. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316630383

Labby, S., Lunenburg, F., & Slate, J. (2012). Emotional intelligence and academic success: A conceptual analysis for educational leaders. NCPEA Publications, Version 1.2.

Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2009). Qualitative analysis of content. In B. Wildemuth (Ed.), Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science (pp. 308-319). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Exploring middle school

Frank Smith

Volume 1, Number 2, 2025

Received March 4 2025

Revised June 25 2025

Accepted July 27 2025

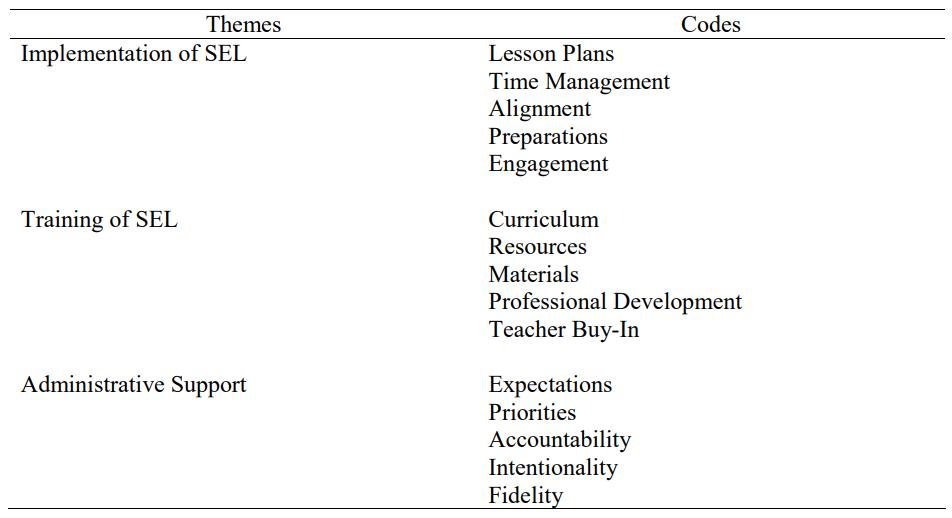

Middle school (grades 6-8) core content (English language arts/reading, mathematics, science, and social studies) teachers are often unprepared to apply social-emotional learning (SEL) strategies effectively and thus often overlook and underutilize these strategies (Mahoney et al., 2021; Shriver & Weissberg, 2020).As a result, teachers are ill-equipped to address students' social, emotional, and behavioral needs, and become overly reliant on punitive and exclusionary forms of discipline, such as suspensions and expulsions (Bailey et al., 2019; United States Department of Education, 2021).Additionally, the inadequate application of SEL methods might lead teachers to believe they are wasting essential teaching time.

The role of SEL strategies in improving student outcomes is well-documented. Previous research has shown that SEL methods may enhance students' behavioral outcomes and academic performance (Mahoney et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2018).Additional positive student outcomes linked to SEL characteristics are academic engagement, good behavior, and feeling connected to school (CASEL, 2020b; Cipriano et al., 2022). In short, students who benefit from